Natural Health Products for Symptomatic Relief of Parkinson’s Disease: Prevalence, Interest, and Awareness

Abstract

Background:

Natural health products have emerged as a potential symptomatic therapeutic approach for people with Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Objective:

To determine the prevalence of natural health product use, interest in natural health products, awareness of potential herb-drug interactions, and consultation of healthcare professionals regarding natural health products use among people with PD.

Methods:

Cross-sectional 4-item survey embedded in the PRIME-NL study, which is a population-based cohort of PD.

Results:

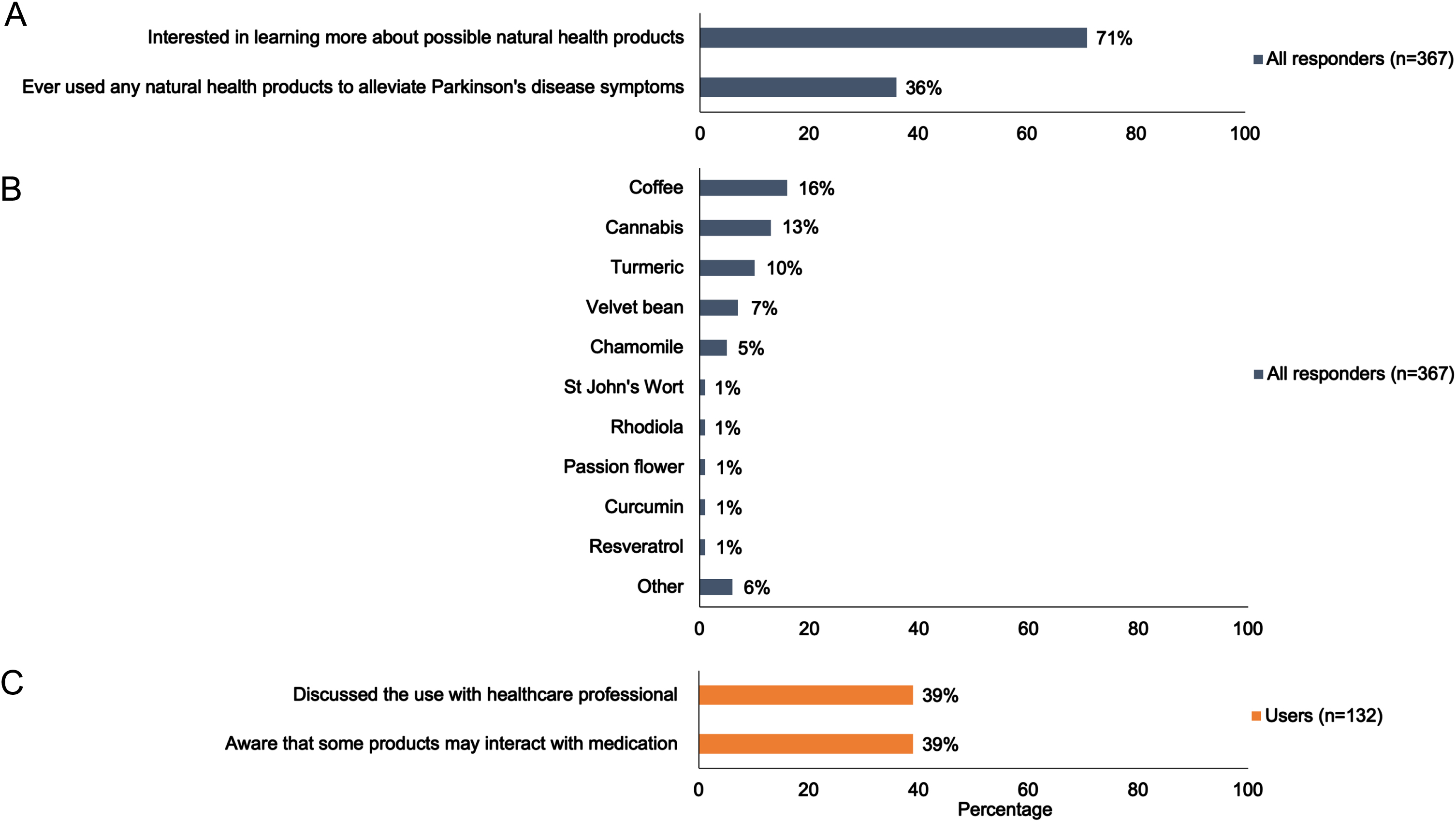

Of 367 people with PD, 36% reported having used natural health products to alleviate PD-related symptoms, with coffee, cannabis and turmeric being the most popular. Furthermore, 71% of people with PD were interested in learning more about natural health products. 39% of natural health products users were aware that these products could interact with PD medication and 39% had discussed their use with their healthcare professional.

Conclusions:

Natural health products are commonly used to alleviate symptoms by people with PD, but most users are unaware that these products can interact with PD medication and do not discuss their consumption with their healthcare professional.

Plain Language Summary

Parkinson’s disease is a complex neurodegenerative disorder for which current treatments are limited to symptomatic relief, and prescribed medication often causes side effects. In this context, there is an increasing interest in non-pharmacological interventions, and people living with Parkinson’s disease may want to explore natural health products to alleviate disease-associated symptoms. Examples of these products include cannabis, coffee, or velvet bean (as a natural source of Levodopa). However, it remains unclear how many people with Parkinson’s disease have ever used, or wish to use, natural health products to relieve disease-related symptoms. In addition, limited information is available to evaluate whether they are aware of possible interactions between these products and prescribed medication. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate these questions in a large representative group of people with Parkinson’s disease. A total of 367 people responded to the survey, and 36% reported that they had used natural health products to relieve Parkinson’s disease-related symptoms. Among the supplements listed in our survey, coffee (16%), cannabis (13%) and turmeric (10%) were the most popular. Additionally, 71% of participants were interested in learning more about natural health products, and we found that 39% of natural health product users were aware of possible interactions with prescribed Parkinson’s disease medication. However, it appeared that only 39% of users had discussed these supplements with their healthcare provider. These observations are important because a concern regarding the integration of natural health products into clinical practice is their potential interactions with prescribed medication. Therefore, these findings support the need for additional research efforts into the health benefits and safety of these products. We conclude that natural health products are used by people with Parkinson’s disease to provide symptomatic relief, and open discussions with their healthcare providers are encouraged to ensure efficacy and safety.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the world’s fastest growing neurodegenerative disorder, currently affecting more than 8.5 million people worldwide [1, 2]. Life-disrupting clinical symptoms include motor (e.g., loss of balance, gait impairment, tremor) as well as non-motor symptoms (e.g., anxiety, constipation, cognitive decline). Available therapeutic approaches are limited to symptomatic treatments, such as those compensating for dopamine deficits induced by the loss of dopaminergic neurons [3]. The limited therapeutic options available to relieve clinical symptoms, the known side effects of PD medication, and the increasing attention for non-pharmacological interventions may encourage people with PD (PwP) to explore the use of natural health products to mitigate their symptoms [4–8]. A number of these products are commercially available and their regulatory pathways are presented in Supplementary Material 1.

There is a lack of systematic studies in a population-representative sample of PwP that quantified the prevalence of ever use of natural health products to mitigate PD-related symptoms, explored the interest in using natural health products or the determinants of this interest, and evaluated the awareness of potential herb-drug interactions. The objective of this cross-sectional study in a representative sample of the spectrum of PwP was to address these gaps in knowledge. Specifically, we evaluated the proportion of PwP who had used or are interested in exploring natural health products to mitigate PD-related symptoms. We also quantified the awareness of potential herb-drug interactions among users, and the proportion of PwP who had discussed the use of these products with their neurologist or PD nurse specialist. A secondary objective was to identify determinants of natural health products use, including gender identity, age, education level, disease duration, and Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage.

METHODS

Participants

This cross-sectional survey was embedded in the Proactive and Integrated Management and Empowerment of Parkinson’s Disease – Netherlands (PRIME-NL) study (description in Supplementary Material 2) [9, 10].

The PRIME-NL study has been approved by the Ethical Board of the Radboud University Medical Center, reference number 2019–5618. Participants signed a digital or written informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Questionnaire

The questions were designed to (1) establish the prevalence of usage of natural health products among PwP, (2) gauge their interest in these products, (3) assess whether PwP communicate with their PD specialist regarding the intake of these products, and (4) evaluate their awareness of potential herb-drug interactions. A total of 11 herbal supplements were included in the study, based on their availability to PwP living in the Netherlands and their potential benefits to mitigate motors and non-motor symptoms. An option “other” was provided to record the use of additional natural health products. The study did not discriminate between food and supplements. Question items regarding the intake of natural health products were phrased to ensure that participants only reported those used to alleviate PD-related symptoms, and not recreational or non-medical uses. Ascertainment methods of covariates have previously been published in detail [9]. In short, gender identity of participants was assessed by offering the options “men”, “women”, and “other”, and none of the respondents selected the “other” option. H&Y stages were based on items in self-administered questionnaires. Education level was self-administered and recategorized into three categories (low-, medium-, and high education) according to the International Standard Classification of Education [11]. The full questionnaire is available in Supplementary Material 3.

Statistical analyses

We quantified the prevalence of ever use of natural health products, interest and determinants of natural health products use, awareness of potential herb-drug interactions, and the prevalence of discussing consumption with PD healthcare professionals among PwP using descriptive statistics. Determinants of natural health products use were determined using Logistic Regression model. We also performed sensitivity analyses, which are described in Supplementary Material 4. SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 27.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R Statistics were used.

RESULTS

Demographics

We invited 566 participants and 367 (65%) responded to the questionnaire. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1 (stratified by gender in Supplementary Material 5). Participants had an average age of 70.3±8.1 years and disease duration of 7.1±4 years (Table 1). The cohort of participants (n = 367) vs. non-participants (n = 199) was comparable in terms of age, education level and stratification by H&Y stages. We found that there was a stronger representation of women (p = 0.005) and an overall shorter disease duration (p < 0.001) in the group of participants vs. non-participants (Supplementary Material 6).

Table 1

Participant characteristics

| Demographics | Total (n = 367) |

| Age, y | 70.3 (8.1) |

| Gender identity, men, % (n) | 54.8 (201) |

| Educationa | |

| Low, % (n) | 23.0 (83) |

| Medium, % (n) | 25.0 (91) |

| Higher, % (n) | 51.5 (191) |

| Disease severity | |

| Disease duration, y, median (IQR) | 6.2 (4.6) |

| H&Yb (1-5 scale) | 2.5 (1.2) |

| H&Y = 1, % (n) | 22.6 (81) |

| H&Y = 2, % (n) | 34.1 (122) |

| H&Y = 3, % (n) | 31.8 (78) |

| H&Y = 4, % (n) | 18.4 (66) |

| H&Y = 5, % (n) | 3.1 (11) |

Mean and standard deviation are reported, unless noted otherwise. H&Y, Hoehn and Yahr; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; n, number. aMissing data for 2 participants.bMissing data for 9 participants.

Prevalence and determinants of natural health products consumption

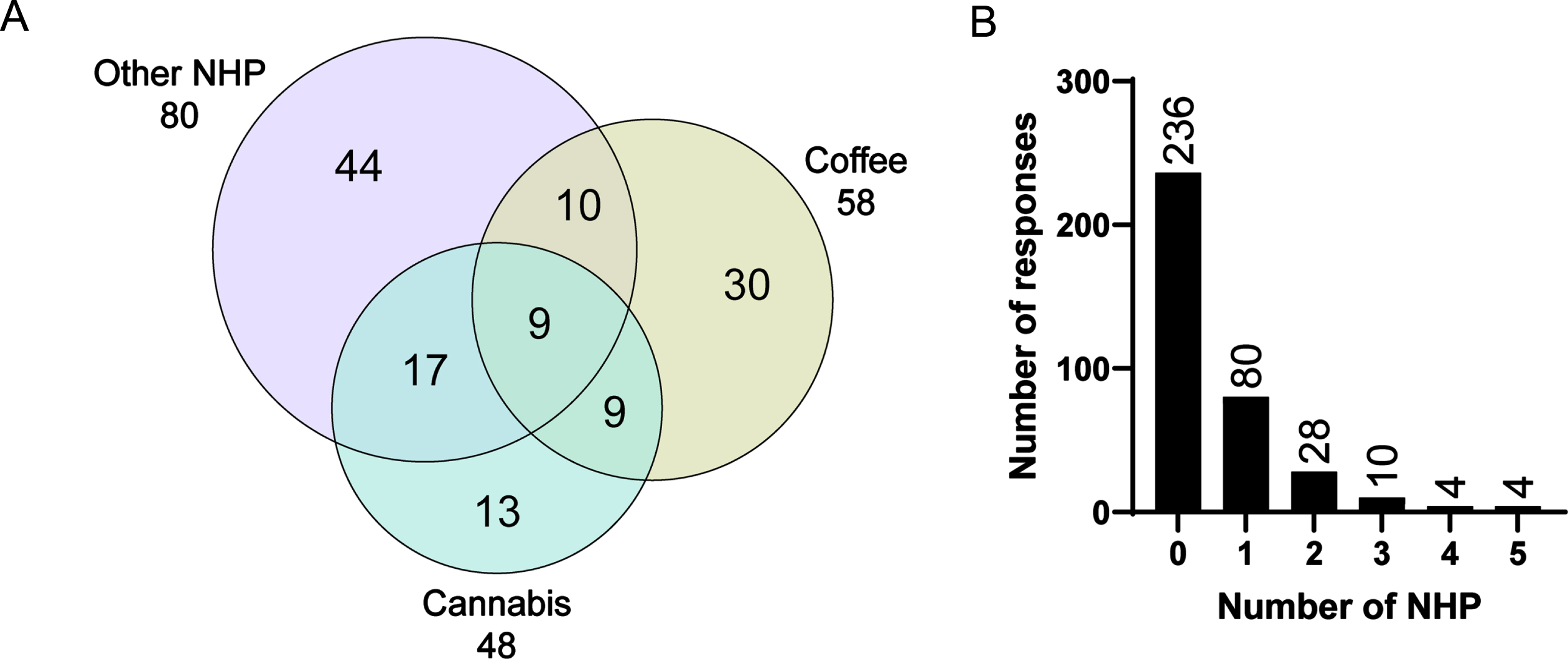

Overall, 36% of participants reported having ever consumed at least one of the 11 herbs listed in the survey or additional herbal products listed as “other” (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Sixteen percent of participants used coffee specifically to attenuate PD-related symptoms, 13% used cannabis, and 5% reported using both coffee and cannabis products (Fig. 2). Other herbal supplements used by PwP included turmeric (Curcuma longa; 10%), chamomile (Matricaria sp., Chamaemelum sp.; 5%), and velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens; 7%) (Fig. 1, Table 2, Supplementary Material 7). All other supplements were reported by less than 2% of participants. In sensitivity analyses, we tested the most conservative scenario by assuming that none of the non-responders (n = 199) had ever used or had any interest in exploring natural health products, 23% of PwP (132/566) used these supplements to mitigate PD-related symptoms. The consumption of herbal remedies was significantly associated with younger age (odds ratio 0.97, 95% CI 0.94-0.99), but not significantly associated with gender identity (odds ratio 1.25, 95% CI 0.75-1.96), education level (odds ratio 1.17, 95% CI 0.95–1.47), disease duration (odds ratio 0.99, 95% CI 0.93–1.05), or H&Y stage (odds ratio 1.16, 95% CI0.93–1.44).

Fig. 1

Use of natural health products to alleviate Parkinson’s disease-related symptoms. A) Bar chart illustrating the interest in- and use of natural health products to alleviate Parkinson’s disease-related symptoms. B) Bar chart illustrating the use of different natural health products to alleviate Parkinson’s disease-related symptoms. C) Bar chart illustrating the awareness of potential herb-drug interactions by people with Parkinson’s disease who used natural health products, and the percentage of people with Parkinson’s disease who discussed their use of herbal supplements with their neurologist or Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist. Data illustrated in Fig. 1 are extracted from Table 2.

Fig. 2

Overview of the usage of single vs. combination of natural health products by people with Parkinson’s disease. A) Venn diagram illustrating the number of participants who acknowledged using natural health products listed in Table 1. Each circle represents the use of coffee, cannabis, or all other natural health products combined. The numbers in these circles represent the number of participants using the corresponding natural health products combination, while the total number of participants who use each natural health products is provided outside the circles. B) Histogram representing the frequency of natural health products use. The “other” category is excluded in this histogram. NHP, natural health products.

Table 2

Use of natural health products to alleviate symptoms associated with PD

| Have you ever used any of the following natural health products with the purpose of alleviating symptoms related to Parkinson’s disease? (Yes % (n)) | |||||

| Proportion of participants who consumed at least one of the products listed below | 36 (132/367) | ||||

| Total (n = 367) | Men (n = 201) | Women (n = 166) | p | Sensitivitya (n = 44) | |

| Cannabis | 13.1 (48) | 10.4 (21) | 16.3 (27) | 0.10 | - |

| Coffee | 15.8 (58) | 13.9 (28) | 18.1 (30) | 0.289 | - |

| Both cannabis and coffee | 4.9 (18) | 3.0 (6) | 7.2 (12) | 0.06 | - |

| Chamomile | 4.6 (17) | 3.0 (6) | 6.6 (11) | 0.10 | (8) |

| Curcumin | 1.1 (4) | 0.5 (1) | 1.8 (3) | 0.23 | (1) |

| Guarana | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 |

| Passion flower | 1.1 (4) | 1.0 (2) | 1.2 (2) | 0.85 | (1) |

| Resveratrol | 0.8 (3) | 0.5 (1) | 1.2 (2) | 0.45 | (1) |

| Rhodiola | 1.1 (4) | 0.5 (1) | 1.8 (3) | 0.23 | (1) |

| St John’s Wort | 1.1 (4) | 1.5 (3) | 0.6 (1) | 0.41 | (1) |

| Turmeric | 9.5 (35) | 9.5 (19) | 9.6 (16) | 0.95 | (20) |

| Velvet bean | 6.8 (25) | 6.0 (12) | 7.8 (13) | 0.48 | (13) |

| Other | 5.7 (21) | 4.5 (9) | 7.2 (12) | 0.26 | (10) |

| Would you be interested in learning more about possible natural health products to alleviate certain symptoms related to Parkinson’s disease? (Yes % (n)) | |||||

| Total (n = 367) | Men (n = 201) | Women (n = 166) | p | ||

| Across the entire cohort | 70.6 (259) | 70.1 (141) | 71.1 (118) | 0.85 | |

| Have you ever discussed the possible use of natural health products with your neurologist or Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist? (Yes % (n)) | |||||

| Total (n = 367) | Men (n = 201) | Women (n = 166) | p | ||

| Among participants who reported not using products | 7.0 (16) | 5.9 (8) | 8.0 (8) | 0.53 | |

| Among participants who reported already using products | 38.9 (51) | 36.4 (24) | 40.9 (27) | 0.59 | |

| Among participants who reported using velvet bean | 76.0 (19) | 75.0 (9) | 76.9 (10) | 0.91 | |

| Are you aware that some natural health products and prescribed Parkinson’s disease medications may work together (or against each other)? (Yes % (n)) | |||||

| Total (n = 132) | Men (n = 66) | Women (n = 66) | p | ||

| Among participants who reported already using products | 38.6 (51) | 30.3 (20) | 47.0 (31) | 0.049 | |

The p-values were calculated to compare the responses by gender identity. n, number. aIn the sensitivity analysis, participants who consumed cannabis, coffee, or both, were excluded and data was not stratified by gender.

Expressed interest in natural health products

A total of 71% (n = 259) of participants reported an interest to learn more about the use of natural health products to treat PD-related symptoms (Fig. 1 and Table 2). In our sensitivity analysis, in which we assumed that the entire subgroup of non-responders was not interested in receiving additional information about natural health products, we found that 46% of PwP (259/566) in our cohort declared being interested in learning more about the use of these products.

Awareness of potential natural health products-drug interactions

When asked if participants were aware that some herbal remedies and prescribed PD medications could interact, 39% (n = 51) of participants who reported using natural health products acknowledged being aware of potential interferences, with a significantly greater proportion of women vs. men (p = 0.049) (Table 2). Our study revealed that 39% of participants who reported using natural health products had prior discussions with their neurologist or PD nurse specialist regarding this use. Furthermore, velvet bean naturally contains L-DOPA (from 3 to more than 100 mg/dose depending on the commercial source [12]) and could therefore interact with dopamine replacement therapies. Among participants who reported using velvet bean, 76% indicated that they had discussed the use of herbal remedies with their PD specialists.

DISCUSSION

This survey revealed that 36% of PwP had used natural health products to alleviate symptoms of PD and the majority of PwP was interested in exploring the use of these supplements. Most consumers had not discussed the use of natural health products with their PD healthcare professional (with the exception of those using velvet bean) and most were unaware that these products could interact with PD medication. In light of the broad use of natural health products by PwP, this study supports the need for rigorous evidence-based research on the clinical efficacy and safety of plant-derived therapeutics, and also identifies a need for designing communication strategies to better inform PwP. The potential clinical benefits of several popular natural health products included in this survey have been investigated (see Supplementary Material 8 for extended discussion). For example, the results of randomized and non-randomized clinical trials suggest potential benefits of medical cannabis to attenuate the severity of motor (e.g., tremor) and non-motor (e.g., sleep, pain) symptoms [13]. Furthermore, clinical use of velvet bean to replace L-DOPA therapy has been reported to induce beneficial effects on motor symptoms [14–16]. However, a significant concern regarding the integration of natural health products into clinical practice is the concomitant use, and potential interference, between traditional PD medication and herbal supplements, which could lead to an altered potency of the prescribed treatment, and even to detrimental herb-drug interactions. A classic example is the intake of St John’s Worth (1.1% of our cohort) and the associated herb-drug interaction with monoamine oxidase B inhibitors [17]. Another example is Mucuna pruriens, which contains levodopa and which may fortify the effects of the levodopa pharmacotherapy prescribed by the physician.

In this report, we documented that coffee, cannabis, and turmeric are popular natural health products. The 13% of participants who reported having ever used cannabis to alleviate PD-related symptoms is comparable to a study in Norway, where 11% of PwP reported cannabis consumption [18], but lower compared to a survey conducted in the USA where 25% of PwP reported cannabis use [19]. The rate of cannabis use is likely dependent on the legality of cannabis in these countries. For medical use, cannabis is legal in the Netherlands, Norway, and the USA. However, recreational use of cannabis is illegal in Norway [20], tolerated in the Netherlands [21], and legal in 24 states of the USA [22]. In terms of age, gender and disease duration, participants of this study are representative for the Dutch PD population [23], which is confirmed by our analysis of external validity (Supplementary Material 6). In addition, demographics and cultural norms also play a role. Therefore, replication of these findings in other countries remains necessary, for example by compiling this information on a larger scale using existing PD-relevant cohorts.

The interest in natural sources of bioactive molecules documented here corroborates other studies indicating that PwP seek to become active players in the design of their therapies [24]. This offers an opportunity to further develop personalized treatments and promote patient involvement in health care decision making. However, it is important to caution patients against the use of potentially ineffective therapies that may delay the prescription of evidence-based treatments. For example, a case report detailed the self-use of velvet bean that caused avoidable disabilities by postponing the intake of a more effective treatment consisting of velvet bean combined with a dopa-decarboxylase inhibitor [14]. Patients should also be informed about possible adverse effects, and about potential interactions with the medication prescribed by their physician. Finally, it is important to inform patients that they may be spending considerable financial investments on interventions which have hitherto not been proven to be effective. Such information could assist patients in making an informed decision tailored to their personal preferences and needs. Our findings also support the need for in-depth investigation of herb-drug interactions, and the symptomatic and disease-modifying properties of natural products. Natural supplements are available over the counter and do not require medical prescriptions, which gives an apparent impression of innocuity despite containing bioactive molecules. In this context, we found that only a subset of participants was informed about herb-drug interactions. These could, for example, affect the efficiency of PD medication via pharmacokinetic or pharmacogenomic interactions [25, 26]. Importantly, our study shows that many patients do not openly discuss the use of natural health products with their physician. In order to optimize both the efficacy and safety of the overall management approach, patients should therefore be encouraged to openly discuss the use of herbal products or any other supplements with their physician or pharmacist. Additional studies are also needed to identify which additional supplements are used by PwP (e.g., ginseng, gingko, green and black tea, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [27]).

Limitations

The results discussed here present a number of limitations. The optional nature of the survey resulted in a 65% response rate, and these participants may have been more interested in the use of natural health products compared to the general PwP population. Gender distribution differed in the group of participants vs. non-participants, and women seemed to be more inclined to complete this survey. Also, the short 4-item questionnaire does not allow for a thorough description of practices such as frequency of use, duration and dosage, natural health products formulation (i.e., pills, tea), which PD-related symptoms are targeted, or the impact of environmental contributions on natural health products consumption. Notably, the complex molecular composition of cannabis-based products, the ratio of cannabinoids vs. tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and the delivery method (ingested vs. inhaled) call for an extensive follow-up investigation. These important elements will be essential to draw a more definitive picture of how PwP supplement their pharmacological treatment, and to clarify if these are punctual or recurring intakes as part of a strategy to improve general wellbeing. Such a more detailed evaluation should be the topic of further research. Additional information on the proportion of PwP who use natural health products as a replacement vs. in addition to PD medication, and insights into the most common herb-drug combinations are also needed to portray a complete profile of these practices. These elements should be investigated further in follow-up studies.

Concluding, we report that many PwP in our sample seek herbal remedies to complement their prescribed PD medication, and most participants expressed an interest in learning about these products. However, there is a need for educational resources that educate PwP on the potential interactions between natural health products and PD medication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all participants who completed this survey, and the PRIME-NL team involved in the project.

FUNDING

This research is part of the Proactive and Integrated Management and Empowerment in Parkinson’s Disease (PRIME) project, which was funded by the Gatsby Foundation [GAT3676] as well as by the Ministry of Economic Affairs by means of the PPP Allowance made available by the Top Sector Life Sciences & Health to stimulate public-private partnerships. The Center of Expertise for Parkinson & Movement Disorders was supported by a center of excellence grant by the Parkinson Foundation.

Financial Disclosures for the previous 12 months: A.d.R.J. is supported by a Launch award from the Parkinson’s Foundation (PF-Launch-937655), the Michael J Fox Foundation, internal funds from the Institute of Nutrition and Functional Foods (INAF), the Quebec Parkinson’s Network, and funds from the Fondation CHU de Québec. B.R.B. currently serves as Editor in Chief for Journal of Parkinson’s disease; serves on the editorial board of Practical Neurology and Digital Biomarkers; has received honoraria from serving on the scientific advisory board for AbbVie, Biogen, and UCB; has received fees for speaking at conferences from AbbVie, Zambon, Roche, GE Healthcare, and Bial; and has received research support from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, The Michael J. Fox Foundation, UCB, AbbVie, the Stichting Parkinson Fonds, the Hersenstichting Nederland, the Parkinson’s Foundation, Verily Life Sciences, Horizon 2020, the Topsector Life Sciences and Health, the Gatsby Foundation, and the Parkinson Vereniging. N.M.d.V reports grants from The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) and The Michael J Fox Foundation. F.C. is a Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé research scholar and is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. S.K.L.D. has received funding from the Parkinson’s Foundation (PF-FBS-2026), ZonMW (09150162010183), ParkinsonNL (P2022-07 and P2021-14), Michael J Fox Foundation (MJFF-022767) and Edmond J Safra Foundation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

B.R.B. and N.M.d.V are Editorial Board Members of this journal but were not involved in the peer-review process of this article nor had access to any information regarding its peer-review. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JPD240102.

REFERENCES

[1] | Dorsey ER , Sherer T , Okun MS , Bloem BR ((2018) ) The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis 8: , S3–S8. |

[2] | GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators ((2018) ) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392: , 1789–1858. |

[3] | Fox SH , Katzenschlager R , Lim SY , Barton B , de Bie RMA , Seppi K , Coelho M , Sampaio C , Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Committee ((2018) ) International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society evidence-based medicine review: Update on treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 33: , 1248–1266. |

[4] | Shan CS , Zhang HF , Xu QQ , Shi YH , Wang Y , Li Y , Lin Y , Zheng GQ ((2018) ) Herbal medicine formulas for Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trials. Front Aging Neurosci 10: , 349. |

[5] | de Rus Jacquet A , TambeM.A. , Rochet J-C. ((2017) ) Dietary phytochemicals in neurodegenerative disease. In Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease, Coulston A, Boushey CJ, Ferruzzi MG, Dalahanty LM, eds. Elsevier, pp. 361–391. |

[6] | de Rus Jacquet A , Subedi R , Ghimire SK , Rochet JC ((2014) ) Nepalese traditional medicine and symptoms related to Parkinson’s disease and other disorders: Patterns of the usage of plant resources along the Himalayan altitudinal range. J Ethnopharmacol 153: , 178–189. |

[7] | de Rus Jacquet A , Tambe MA , Ma SY , McCabe GP , Vest JHC , Rochet JC ((2017) ) Pikuni-Blackfeet traditional medicine: Neuroprotective activities of medicinal plants used to treat Parkinson’s disease-related symptoms. J Ethnopharmacol 206: , 393–407. |

[8] | de Rus Jacquet A , Timmers M , Ma SY , Thieme A , McCabe GP , Vest JHC , Lila MA , Rochet JC ((2017) ) Lumbee traditional medicine: Neuroprotective activities of medicinal plants used to treat Parkinson’s disease-related symptoms. J Ethnopharmacol 206: , 408–425. |

[9] | Ypinga JHL , Van Halteren AD , Henderson EJ , Bloem BR , Smink AJ , Tenison E , Munneke M , Ben-Shlomo Y , Darweesh SKL ((2021) ) Rationale and design to evaluate the PRIME Parkinson care model: A prospective observational evaluation of proactive, integrated and patient-centred Parkinson care in The Netherlands (PRIME-NL). BMC Neurol 21: , 286. |

[10] | Gelissen LMY , Van den Bergh R , Talebi AH , Geerlings AD , Maas BR , Burgle MM , Kroeze Y , Smink A , Bloem BR , Munneke M , Ben-Shlomo Y , Darweesh SLK ((2024) ) Assessing the validity of a Parkinson’s care evaluation: The PRIME-NL study. Eur J Epidemiol, in press. |

[11] | UNESCO ((2012) ) International Standard Classification of Education. UNESCO Institutes for Statistics, Montreal, Canada. |

[12] | Soumyanath A , Denne T , Hiller A , Ramachandran S , Shinto L ((2018) ) Analysis of levodopa content in commercial Mucuna pruriens products using high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J Altern Complement Med 24: , 182–186. |

[13] | Urbi B , Corbett J , Hughes I , Owusu MA , Thorning S , Broadley SA , Sabet A , Heshmat S ((2022) ) Effects of cannabis in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Parkinsons Dis 12: , 495–508. |

[14] | Radder DLM , Tiel Groenestege AT , Boers I , Muilwijk EW , Bloem BR ((2019) ) Mucuna pruriens combined with carbidopa in Parkinson’s disease: A case report. J Parkinsons Dis 9: , 437–439. |

[15] | Katzenschlager R , Evans A , Manson A , Patsalos PN , Ratnaraj N , Watt H , Timmermann L , Van der Giessen R , Lees AJ ((2004) ) Mucuna pruriens in Parkinson’s disease: A double blind clinical and pharmacological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 75: , 1672–1677. |

[16] | Manyam BV , Sanchez-Ramos JR ((1999) ) Traditional and complementary therapies in Parkinson’s disease. Adv Neurol 80: , 565–574. |

[17] | Grissinger M ((2018) ) Delayed administration and contraindicated drugs place hospitalized Parkinson’s disease patients at risk. P T 43: , 10–39. |

[18] | Erga AH , Maple-Grodem J , Alves G ((2022) ) Cannabis use in Parkinson’s disease-A nationwide online survey study. Acta Neurol Scand 145: , 692–697. |

[19] | Feeney MP , Bega D , Kluger BM , Stoessl AJ , Evers CM , De Leon R , Beck JC ((2021) ) Weeding through the haze: A survey on cannabis use among people living with Parkinson’s disease in the US. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 7: , 21. |

[20] | Egnell S ((2019) ) Cannabis policy and legislation in the Nordic countries - A report on the control of cannabis use and possession in the Nordic legal systems. Nordic Welfare Centre. |

[21] | Haines G ((2017) ) Everything you need to know about marijuana smoking in the Netherlands. The Telegraph. |

[22] | State medical cannabis laws, National Conference of State Legislatures, https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx, Accessed 2 January, 2024. |

[23] | Maas BR , Bloem BR , Ben-Shlomo Y , Evers LJW , Helmich RC , Kalf JG , van der Marck MA , Meinders MJ , Nieuwboer A , Nijkrake MJ , Nonnekes J , Post B , Sturkenboom IHWM , Verbeek MM , de Vries NM , van de Warrenburg B , van de Zande T , Munneke M , Darweesh SKL ((2023) ) Time trends in demographic characteristics of participants and outcome measures in Parkinson’s disease research: A 19-year single-center experience. Clin Park Relat Disord 8: , 100185. |

[24] | Weernink MG , van Til JA , van Vugt JP , Movig KL , Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG , MJ IJ ((2016) ) Involving patients in weighting benefits and harms of treatment in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 11: , e0160771. |

[25] | Pizzolato K , Thacker D , Toro-Pagan ND , Hanna A , Turgeon J , Matos A , Amin N , Michaud V ((2021) ) Cannabis dopaminergic effects induce hallucinations in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. Medicina (Kaunas) 57: , 1107. |

[26] | Asher GN , Corbett AH , Hawke RL ((2017) ) Common herbal dietary supplement-drug interactions. Am Fam Physician 96: , 101–107. |

[27] | Coulombe K , Saint-Pierre M , Cisbani G , St-Amour I , Gibrat C , Giguere-Rancourt A , Calon F , Cicchetti F ((2016) ) Partial neurorescue effects of DHA following a 6-OHDA lesion of the mouse dopaminergic system. J Nutr Biochem 30: , 133–142. |