Burden, Anxiety, and Depression Among Caregivers of Parkinson’s Disease Patients

Abstract

Background:

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a disabling neurodegenerative movement disorder. Most PD patients are looked after by caregivers who are close to them regardless of their relationship. Caregivers may experience a notable impact on their mental health as they dedicate a significant amount of time to the patient while observing the progression of the disease.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the level of burden, depression, anxiety, and stress among caregivers of PD patients.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis between July and September 2023 among caregivers of PD patients following in the Movement Disorders Clinic at King Khalid University Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and through the Saudi Parkinson’s Society. The data collection was done anonymously through an electronic self-administered questionnaire. Caregiver burden was assessed by using the validated Arabic version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) scale, and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) was used to assess the presence and level of anxiety and depression.

Results:

There were 118 caregivers (53.39% female, 33.9% aged between 35– 45 years, and 73.73% were sons/daughters) caring for 118 patients (57.63%, male, 38.98% aged between 66– 76). The ZBI score was highest among sibling caregivers. Moreover, burden scores were higher among those who provided care more frequently than others.

Conclusions:

Our study revealed that PD caregivers face a high risk of care burden, especially those who are siblings and spend longer periods in patient care. Additionally, female caregivers reported higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Plain Language Summary

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a serious condition that affects movement, and most PD patients are cared for by someone close to them, such as a family member. This caregiving can significantly impact the mental health of the caregiver, who often spends a lot of time caring for the patient and witnessing the disease’s progression. We studied caregivers of PD patients at the Movement Disorders Clinic at King Khalid University Hospital and through the Saudi Parkinson’s Society from July to September 2023. Caregivers completed an anonymous electronic questionnaire, and we measured caregiver burden using the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) and assessed anxiety and depression using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS). Our study included 118 caregivers (53.39% female, most aged 35– 45 years, and 73.73% were sons or daughters) caring for 118 PD patients (57.63% male, most aged 66– 76 years). Caregivers who were siblings or cared for the patient daily had higher burden scores, and female caregivers had higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to males. Our study revealed that PD caregivers face a high risk of care burden, especially those who are siblings and spend longer periods in patient care, and that female caregivers exhibited an elevated risk of experiencing depression, anxiety, or stress.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a disabling progressive neurodegenerative movement disorder with four cardinal motor features: resting tremor, slow movement or bradykinesia, muscle stiffness or rigidity, and postural instability.1 It is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, with an incidence of 5 in 100,000 to over 35 in 100,000 per year worldwide and an incidence of 4.5 per 100,000 in the Arab population.2,3 The estimated prevalence in industrialized countries is around 0.3% for the general population, and it increases with aging, reaching 3% for people older than 80 years.4 The prevalence of PD in Saudi Arabia has been estimated to be 27 per 100,000.5 Despite pharmacological and surgical strategies, PD is associated with a high risk of mortality and a reduction in life expectancy with severe disabilities, where the majority of PD patients in the advanced phase become dependent on others in their Activities of Daily Living (ADLs).6,7

Most PD patients are looked after by caregivers who are close to them regardless of their relationship; they could be partners, close relatives, or family members.8–10 Moreover, caregivers may experience a notable impact on their mental health as they dedicate a significant amount of time to the patient while observing the progression of the disease. It is well known that PD worldwide has an impact on caregivers by increasing their burden, especially in the late stages of the disease.11 Furthermore, it has been determined that palliative care, including caregiver support, is beneficial and linked to PD patients experiencing a higher Quality of life (QoL).12

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) is a scale used to measure caregivers’ burden and has been used in a previous study, which revealed that most Saudi caregivers experienced some degree of stress and burden due to taking care of their elderly relatives.13 The consequences of caregiving that have been most investigated are depression and stress. That said, caregivers should be included in managing and counselling PD patients due to their impact on the patient’s QoL and disability.14 Furthermore, most PD patients are diagnosed at retirement age, while at the same time, their caregivers start to have new responsibilities in their lives that consume their time and energy, which can put the caregivers at a high risk of physical exhaustion and burnout.15 These are exacerbated by poor stress management and physically inactive patients.16

The extent of burden within communities, such as the Saudi community, where caregiving is viewed as a religious and cultural obligation, remains uncertain. This study aims to explore the caregiver burden and the prevalence of associated psychiatric illnesses among those caring for individuals with PD.

METHODS

Participants

An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted between July and September 2023 among caregivers of PD patients who were following in the Movement Disorders Clinic at King Khalid University Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and through the Saudi Parkinson’s Society by distributing the questionnaire among the patients’ caregivers. All informal caregivers were included (the majority were family members); however, we excluded paid caregivers and non-Arabic speakers. The Institutional Review Board of King Saud University approved the study (E-23-7958).

Measurements

The data was collected anonymously through an electronic self-administered questionnaire developed to collect data on caregiver and patient demographics. Each participant completed the study questionnaire, which consisted of three sections. The first section included the demographics of both the caregiver and the patient, as well as information related to the patient’s illness. The second section consisted of the validated Arabic version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI).17 The third section contained the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS), used for assessing the presence and level of anxiety and depression among caregivers.

The validated Arabic version of the ZBI Scale used to assess caregiver burden includes 22 items divided into two factors: personal and role strain.17 The questions investigate multiple areas, including caregiver health, psychological well-being, finances, social life, and the relationship between patient and caregiver. Each question scores out of 5 points, ranging from never = 0 to nearly always = 4, and total score ranging from 0 to 88. The cut-off values for the ZBI are as follows: a score of 0– 20 indicates little or no burden, 21– 40 indicates mild to moderate burden, 41– 60 indicates moderate to severe burden, and 61– 88 indicates severe burden.18 Furthermore, caregivers’ depression, anxiety, and stress were evaluated using the Arabic version of the DASS-8 scale, a shorter version of the DASS-21 scale that was validated by A. Ali et al. to measure psychometric properties.19 It consists of 8 questions (three for depression, three for anxiety, and two for stress). Each question has a score from 0– 3, where 0 = never and 3 = most of the time. The cut-off values of both the depression and anxiety questions were 0– 3 for normal, 4– 6 for moderate, and 7– 9 for severe. While the cut-off values for stress were 0– 2 for normal, 3– 4 for moderate and 5– 6 for severe.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using R version 4.2.3 and Microsoft Excel. Continuous data was presented using mean±standard deviation (SD) and median (minimum, maximum) values. Categorical variables were represented by frequency and percentage. The normality of the ZBI, DASS-8 subscales, and total DASS score were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The variables were found to follow a nonnormal distribution. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare the ZBI and total DASS score over patient and caregiver characteristics with 2 groups. The Kruskal Wallis test was used to compare the ZBI and total DASS score over patient and caregiver characteristics with more than 2 groups. Dunn’s test is used as a post hoc analysis. Pearman’s rank correlation test was used to measure the strength and direction of associations. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all the tests. The correlation coefficient was considered significant moderate positive when the correlation coefficient was≥0.6 and was considered to be significant high positive when it was≥0.7.

RESULTS

Caregiver’s characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1

Distribution according to caregiver’s characteristics (n = 118)

| Variables | Subcategory | Number of subjects (%) |

| Carer Age | Less than 35 years | 37 (31.36%) |

| 35– 45 years | 40 (33.9%) | |

| 46– 55 years | 26 (22.03%) | |

| 56– 65 years | 12 (10.17%) | |

| 66– 76 years | 3 (2.54%) | |

| Carer gender | Female | 63 (53.39%) |

| Male | 55 (46.61%) | |

| Are you the only caregiver? | No | 85 (72.03%) |

| Yes | 33 (27.97%) | |

| Is the other caregiver a paid one? (n = 85) | Yes | 29 (34.12%) |

| No | 56 (65.88%) | |

| What is your relationship with the caregiver? | Spouse | 22 (18.64%) |

| Son/daughter | 87 (73.73%) | |

| Brother/sister | 4 (3.39%) | |

| Other | 5 (4.24%) | |

| How often do you care for the Parkinson’s patient? | Daily | 93 (78.81%) |

| 2– 3 times a week | 15 (12.71%) | |

| Once a week | 4 (3.39%) | |

| Less than once weekly | 6 (5.08%) |

In our study, 118 caregivers participated, with female caregivers representing 53.39% and male caregivers 46.61%. The largest age category was 35 to 45 years old (33.9%), followed by those under 35 years (31.36%). Most caregivers (72.03%) worked alongside others, while 27.97% were sole caregivers. Among those working with others, 65.88% had unpaid co-caregivers, and 34.12% had paid co-caregivers. Regarding the relationship with the care recipient, 73.73% were sons or daughters, 18.64% were spouses, 3.39% were siblings, and 4.24% had another relationship. The majority (78.81%) provided daily care, while 12.71% provided care 2– 3 times a week, 3.39% once a week, and 5.08% less than once a week.

Patient’s characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2

Distribution according to patient’s characteristics (n = 118)

| Variables | Subcategory | Number of subjects (%) |

| Patient’s age | Less than 45 years | 1 (0.85%) |

| 45– 55 years | 17 (14.41%) | |

| 56– 65 years | 28 (23.73%) | |

| 66– 76 years | 46 (38.98%) | |

| More than 80 years | 26 (22.03%) | |

| Patient’s gender | Female | 50 (42.37%) |

| Male | 68 (57.63%) | |

| Does the patient suffer from dementia or memory loss? | No | 79 (66.95%) |

| Yes | 39 (33.05%) | |

| How can the patient mobilize? | The patient can mobilize on their own without any help needed | 41 (34.75%) |

| The patient cannot mobilize except with help from a carer or using a tool | 59 (50%) | |

| The patient does not mobilize at all | 18 (15.25%) | |

| What type of activities can the patient do on his own without help from his carer? | The patient is independent in all activities | 29 (24.58%) |

| The patient is dependent on their carer in complex activities (e.g., bathing) | 25 (21.19%) | |

| The patient is dependent on their carer for minor activities (e.g., eating) | 18 (15.25%) | |

| The patient is completely dependent on their carer | 46 (38.98%) | |

| Did the patient undergo any procedures or surgeries related to PD? | No | 99 (83.9%) |

| Yes, the patient had DBS surgery | 14 (11.86%) | |

| Yes, the patient is on levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) | 5 (4.24%) | |

| Does the patient undergo physiotherapy? | No | 84 (71.19%) |

| Yes | 34 (28.81%) |

Our study found that the majority of PD patients were male (57.63%) compared to female patients (42.37%). Most patients were in the 66– 76 age group (38.98%), followed by those aged 56– 65 years (23.73%). Additionally, 22.03% of patients were over 80 years old, 14.41% were between 45– 55 years, and less than 1% were younger than 45 years. Among associated medical conditions, 33.05% of patients were diagnosed with dementia or memory loss. In terms of mobility, 34.75% of patients could move around independently, while 50% required assistance from caregivers or assistive devices, and 15.25% were unable to mobilize at all. Moreover, 28.81% of patients regularly underwent physiotherapy. Regarding activities of daily life, 24.58% of patients were self-sufficient, 21.19% depended on caregivers for complex tasks like bathing, 15.25% relied on caregivers for basic activities such as eating, and 38.98% were completely dependent on caregivers for all aspects of daily life. Finally, 83.9% of patients had not undergone any PD-related surgeries, while 11.86% had undergone DBS surgery, and 4.24% had a Levodopa-Carbidopa Intestinal Gel (LCIG) in place.

Zarit Burden Interview grading and DASS-8 subscales (Table 3)

Table 3

Distribution of Zarit grading and DASS-8 subscales (n = 118)

| Variables | Subcategory | Number of subjects (%) |

| Zarit grading | No to mild burden | 44 (37.29%) |

| Mild to moderate burden | 40 (33.9%) | |

| High burden | 34 (28.81%) | |

| DASS-8 Depression | Normal | 72 (61.02%) |

| Moderate | 29 (24.58%) | |

| Severe | 17 (14.41%) | |

| DASS-8 Anxiety | Normal | 79 (66.95%) |

| Moderate | 28 (23.73%) | |

| Severe | 11 (9.32%) | |

| DASS-8 stress | Normal | 70 (59.32%) |

| Moderate | 32 (27.12%) | |

| Severe | 16 (13.56%) |

Out of 118 caregivers, the ZBI grading indicated that 37.29% of caregivers experienced no to mild burden, 33.9% had mild to moderate burden, and 28.81% experienced high burden in their caregiving role. When assessing depression levels using the DASS-8 scale, we found that 61.02% of caregivers were normal, 24.58% had moderate depression, and 14.41% had severe depression. In terms of anxiety levels assessed with the DASS-8 scale, 66.95% of caregivers were normal, 23.73% had moderate anxiety, and 9.32% had severe anxiety. Regarding stress levels measured using the DASS-8 scale, 59.32% of caregivers were normal, 27.12% had moderate stress, and 13.56% had severe stress.

Zarit burden interview score and Total DASS score over caregiver’s characteristics (Table 4)

Table 4

Comparison of Zarit burden interview score and Total DASS score over Caregiver’s characteristics

| Variables | Subcategory | Zarit burden interview score | Total DASS score |

| mean±SD, | mean±SD, | ||

| Median (min, max) | Median (min, max) | ||

| Carer’s Age | Less than 35 years | 15.86±10.74 | 9.05±7.13 |

| 12 (0, 46) | 8 (0, 24) | ||

| 35– 45 years | 13.95±9.9 | 6.28±6.84 | |

| 12.5 (0, 33) | 3 (0, 24) | ||

| 46– 55 years | 16.81±11.57 | 8.35±7.02 | |

| 14 (3, 40) | 6.5 (0, 21) | ||

| 56– 65 years | 17±9.29 | 7.67±5.66 | |

| 15.5 (4, 35) | 9 (0, 17) | ||

| 66– 76 years | 17±7 | 8.67±8.5 | |

| 17 (10, 24) | 9 (0, 17) | ||

| p | 0.8436@ | 0.3239@ | |

| Carer’s gender | Female | 16.6±10.57 | 9.38±6.76 |

| 15 (0, 40) | 9 (0, 24) | ||

| Male | 14.38±10.08 | 6±6.63 | |

| 12 (0, 46) | 3 (0, 24) | ||

| p | 0.1806# | 0.0045# * | |

| Are you the only caregiver? | No | 14.65±9.91 | 7.66±6.95 |

| 13 (0, 46) | 6 (0, 24) | ||

| Yes | 17.94±11.24 | 8.18±6.79 | |

| 17 (0, 40) | 6 (0, 21) | ||

| p | 0.1808# | 0.6605# | |

| Is the other caregiver a paid one? | No other carer | 17.94±11.24 | 8.18±6.79 |

| 17 (0, 40) | 6 (0, 21) | ||

| No | 13.45±9.11 | 6.93±6.66 | |

| 12 (0, 38) | 4.5 (0, 24) | ||

| Yes | 16.97±11.1 | 9.07±7.4 | |

| 15 (0, 46) | 8 (0, 24) | ||

| p | 0.1578@ | 0.4223@ | |

| What is your relationship with the patient? | Spouse | 19.77±11.75 | 10.55±6.95 |

| 21.5 (0, 40) | 11 (0, 21) | ||

| Son/daughter | 14.74±9.94 | 7.37±6.86 | |

| 13 (0, 46) | 5 (0, 24) | ||

| Brother/sister | 20.25±9.29 | 5.75±3.59 | |

| 18.5 (11, 33) | 6.5 (1, 9) | ||

| Other | 7.8±3.63 | 5±7.31 | |

| 9 (4, 12) | 2 (1, 18) | ||

| p | 0.0461@ * | 0.232@ | |

| How often do you care for the Parkinson’s patient? | Daily | 16.8±10.38 | 8.39±7.02 |

| 16 (0, 46) | 8 (0, 24) | ||

| 2– 3 times a week | 13.27±10.43 | 6.67±6.54 | |

| 11 (2, 38) | 4 (1, 19) | ||

| Once a week | 9±4.69 | 5.75±7.23 | |

| 8.5 (4, 15) | 4 (0, 15) | ||

| Less than once weekly | 6.67±6.12 | 3±3.1 | |

| 7 (0, 16) | 2.5 (0, 8) | ||

| p | 0.0238@ * | 0.2312@ | |

n = 118, mean±SD, Median (min, max). @Kruskal Wallis test; #Mann Whitney U test; *indicates statistical significance.

We found that there is a significant difference in the ZBI score depending on the caregiver’s relationship with the patient (p = 0.0461). The ZBI score was high when the caregiver was a brother/sister, followed by a spouse, a son/daughter, and then other relations. From post hoc analysis, it is observed that the ZBI score was significantly higher among those with a brother/sister relationship compared to other relationships (p = 0.0407), as well as higher among those with a spouse relationship compared to other relationships (p = 0.0159). The ZBI score differed significantly based on the frequency of care provided to the PD patient (p = 0.0238). It was observed that the more often caregivers provided care, the higher the ZBI score. Post hoc analysis showed that the ZBI score was significantly higher among those who cared daily compared to those who cared less than once weekly (p = 0.0131). Additionally, a significant difference in the Total DASS score was noted based on the gender of the caregiver (p = 0.0045), where it was observed that females had a higher total DASS score compared to males.

Zarit burden interview score and Total DASS score over patient’s characteristics (Table 5)

Table 5

Comparison of Zarit burden interview score and Total DASS score over patient’s characteristics

| Variables | Subcategory | Zarit burden interview score | Total DASS score |

| mean±SD, | mean±SD, | ||

| Median (min, max) | Median (min, max) | ||

| Patient’s age | Less than 45 years | 27 | 14 |

| 45– 55 years | 14.65±12.61 | 6.59±6.59 | |

| 11 (0, 46) | 5 (0, 21) | ||

| 56– 65 years | 16±9.61 | 7.93±6.97 | |

| 14.5 (0, 39) | 7 (0, 24) | ||

| 66– 76 years | 17.15±10.5 | 8.67±7.33 | |

| 16.5 (0, 40) | 8.5 (0, 24) | ||

| More than 80 years | 12.46±9.01 | 6.69±6.3 | |

| 13 (0, 36) | 4.5 (0, 18) | ||

| p | 0.2622@ | 0.6939@ | |

| Patient’s gender | Female | 18.12±10.05 | 8.56±6.83 |

| 16.5 (0, 46) | 8 (0, 24) | ||

| Male | 13.69±10.25 | 7.25±6.92 | |

| 12 (0, 40) | 6 (0, 21) | ||

| p | 0.0114# * | 0.2108# | |

| Does the patient suffer from dementia or memory loss? | No | 14±9.69 | 6.7±6.26 |

| 13 (0, 46) | 5 (0, 24) | ||

| Yes | 18.74±11.05 | 10.05±7.6 | |

| 17 (0, 40) | 9 (0, 24) | ||

| p | 0.0313# * | 0.0279# * | |

| How does the patient mobilize? | The patient can mobilize on his own without any help needed | 10.27±7.6 | 5.54±6.23 |

| 10 (0, 31) | 3 (0, 21) | ||

| The patient cannot mobilize except with help from a carer or using a tool | 17.73±10.14 | 8.98±6.86 | |

| 17 (0, 40) | 8 (0, 24) | ||

| The patient does not mobilize at all | 20.56±11.89 | 9.11±7.44 | |

| 21 (3, 46) | 9.5 (0, 20) | ||

| p | <0.001@ * | 0.0216@ * | |

| What type of activities can the patient do on their own without help from their carer? | The patient is independent in all activities | 10.72±7.96 | 5.34±6.25 |

| 10 (0, 31) | 2 (0, 21) | ||

| The patient is dependent on their carer in minor activities like eating | 11.83±8.01 | 7.83±7.49 | |

| 10.5 (0, 27) | 5.5 (0, 21) | ||

| The patient is dependent on their carer in complex activities | 16.56±9.64 | 8.88±7.19 | |

| 15 (0, 38) | 8 (0, 24) | ||

| The patient is completely dependent on their carer | 19.54±11.32 | 8.76±6.69 | |

| 20 (0, 46) | 8.5 (0, 24) | ||

| p | <0.001@ * | 0.1292@ | |

| Did the patient undergo any procedures or surgeries related to PD? | No | 15.27±10.67 | 7.78±7.11 |

| 13 (0, 46) | 6 (0, 24) | ||

| Yes, the patient had DBS surgery | 17.07±8.75 | 8.36±6.07 | |

| 18.5 (0, 32) | 9 (0, 17) | ||

| Yes, the patient is on levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) | 17.2±9.28 | 6.8±5.12 | |

| 17 (5, 31) | 6 (1, 13) | ||

| p | 0.5244@ | 0.9602@ | |

| Does the patient undergo physiotherapy? | No | 15.19±10.19 | 7.3±6.55 |

| 13.5 (0, 39) | 6 (0, 24) | ||

| Yes | 16.5±10.86 | 9.06±7.6 | |

| 14 (0, 46) | 7.5 (0, 24) | ||

| p | 0.6028# | 0.239# | |

| In case the patient cannot mobilize on their own, how can they mobilize? | Can walk without any help | 11.14±9.25 | 5.36±5.21 |

| 10 (0, 39) | 3.5 (0, 17) | ||

| With the help of someone else beside him | 17.62±10.15 | 9.21±7.55 | |

| 17 (0, 46) | 7.5 (0, 24) | ||

| Using a cane | 12.86±11.09 | 7.19±7.2 | |

| 10 (0, 38) | 3 (0, 21) | ||

| Using a walker with wheels | 15±7.92 | 8.7±8 | |

| 15 (4, 28) | 7.5 (0, 21) | ||

| Using a wheelchair | 18.48±10.54 | 8.13±6.49 | |

| 15 (3, 40) | 8 (0, 24) | ||

| p | 0.0341@ * | 0.4531@ | |

n = 118, mean±SD, Median (min, max). @Kruskal Wallis test; #Mann Whitney U test; *indicates statistical significance.

We observed that the ZBI score was significantly higher when the PD patient was a female as opposed to a male (p = 0.0114). Additionally, the ZBI score was significantly higher when the patient suffered from dementia or memory loss (p = 0.0313). There was a significant difference in the ZBI score based on the extent to which the patient mobilizes (p < 0.001). From post hoc analysis, we found that the ZBI score was high when the patients couldn’t mobilize at all (p = 0.0018) or required assistance from a caregiver, or a mobility aid (p = 0.0007) compared to patients who could mobilize independently. There was a significant difference in the ZBI score based on the type of activities the patient can do independently without help from his carer (p < 0.001). From post hoc analysis, we found that the ZBI score is high when the patient was entirely dependent on their caregiver as opposed to being independent in all activities (p = 0.0030). There was a significant difference in the ZBI score based on the method of patient mobility (p = 0.0341). From post hoc analysis, we concluded that the ZBI score is high when the patient uses a wheelchair (p = 0.0078) or requires assistance from someone else (p = 0.0123) compared to patients who could walk without assistance. The total DASS score was significantly higher when the patient suffered from dementia or memory loss (p = 0.0279). There was a significant difference in the total DASS score based on the extent to which the patient mobilizes (p = 0.0216). Furthermore, post hoc analysis showed that the total DASS score was high when the patient couldn’t mobilize at all (p = 0.0498) or required assistance from a caregiver or a mobility aid (p = 0.02), as opposed to patients who could mobilize independently.

Zarit burden interview score with DASS-8 subscales and total score

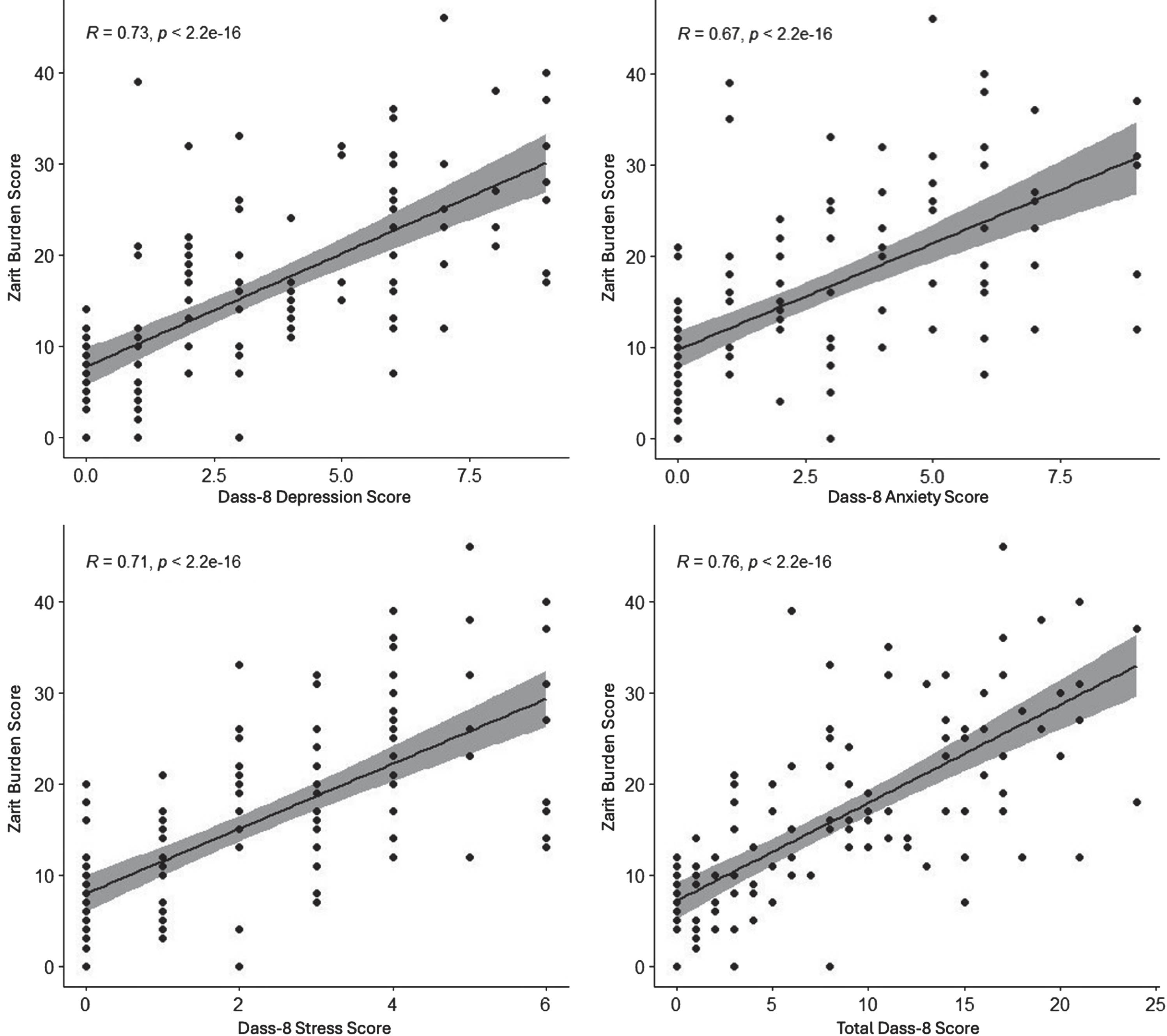

Figure 1A–D demonstrate the relationship between the ZBI score and the DASS-8 subscales along with the total DASS score using Spearman’s rank correlation test. The DASS-8 Anxiety score shows a significant moderate positive correlation with the ZBI scale (p < 0.001). Additionally, the DASS-8 Stress score, DASS-8 Depression score, and Total DASS score exhibit significant high positive correlation with the ZBI scale (all p-values <0.001).

Fig. 1

Scatter plot of DASS-8 separate scores (A, B, C) and the total score (D) versus Zarit burden interview score.

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to examine the care burden among caregivers of Saudi PD patients using the validated Arabic version of ZBI to assess the burden and the validated Arabic version of DASS-8 as a measure of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Our study found that the mean ZBI score in our population is lower than that reported in other countries. For instance, in a study across six European countries involving late-stage PD patients’ caregivers, the mean ZBI score among 506 caregivers was 31.3±16,20 while our mean ZBI score was 15.6±10.3. In the Saudi society, caregiving is viewed as a fundamental duty towards family members, influenced by cultural, religious, and societal norms. This may contribute to lower burden scores among caregivers in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, most PD caregivers in the same European study experienced stress, while half had depression and anxiety, contrasting with our findings, where most Saudi caregivers did not report depression, anxiety, or stress. In another study conducted in Italy among caregivers of PD patients who were on continuous dopaminergic delivering systems either LCIG or continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion (CSAI) versus those on the standard of care, mean ZBI score of 29.6±14.4, 35.8±20.2 and 31.4±16.0 respectively.21 Interestingly, about 42% of caregivers of PD patients who were on LCIG experienced a mild to moderate burden,21 which was higher than the 33.9% we found in our study. However, the number of PD patients utilizing LCIG in our sample was small, and our study was not directed specifically at caregivers of advanced PD, as was done in this study.

Baseline caregiver characteristics showed no association with the ZBI scale, except for the caregiver’s relationship with the patient and the frequency of care provided. We found that caregivers who were siblings had higher ZBI scores compared to other caregivers, including spouses and sons/daughters. This could be attributed to the cultural and religious perception of caregiving as a duty towards parents and spouses, which is more pronounced than the duty towards siblings. Further research could explore how these cultural and religious beliefs impact the experiences and burdens of caregivers from different familial roles. Our findings were different from previous reports of studies performed in other countries, where spouses as caregivers had a more significant burden and were highly correlated with depression and stress than offspring caregivers, which might be related to the age and longer care time.22–24 Although age was not associated with a high disease burden in our study, most caregivers were younger than 55 years. Furthermore, those who spent most of their day caring for PD patients had high ZBI scores, which is similar to a previous study, showing that longer care time is considered a significant influence on burden.23 The proposed theory behind this finding is that patients who require longer care time may be due to their dependency on others, contributing to an increased disease burden on caregivers. We found a correlation between the female gender of caregivers and elevated DASS-8 scores. Unfortunately, no previous study measured DASS-8 among PD caregivers or patients.

On the other hand, we found significant associations between multiple patients’ characteristics and an elevated ZBI score, including gender, coexisting dementia or memory impairment, mobility, and performing ADLs. Carers of female PD patients were more likely to have higher ZBI scores. Moreover, taking care of patients with dementia or memory impairment and patients with limited mobility who either cannot mobilize or need assistance with mobility had high ZBI scores and DASS-8. Finally, the more the patient required assistance in their ADLs, the higher the ZBI score. Findings regarding caregivers’ burden association with patients’ gender and memory impairment were consistent with previously reported studies. Taking care of patients with neurodegenerative disease is challenging, and several factors contribute to this. A study conducted among caregivers of Saudi patients with chronic diseases reported that more than half of caregivers were young females aged between 18 and 27 years old, and their ZBI scores ranged from mild to moderate (42.9%) with a mean of 31.3.13 Furthermore, a study was conducted among caregivers of patients with dementia used the Patient Health Questionnaire PHQ-9, an instrument used for depression screening, diagnosis, or monitoring.25 The study found a moderate increase in depression scores among caregivers compared to the general Saudi population. Moreover, those who were financially responsible for the demented patient and unemployed caregivers were more likely to develop depression.25 Another study conducted among Saudi caregivers who were sons or daughters of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients showed a high prevalence of depression, which was even higher among caregivers of AD patients with repeated falls.26 Furthermore, a study that measured DASS scores among dementia patients and their caregivers found that female caregivers who are caring for dependent patients had higher distress scores, when compared to male caregivers and caregivers of an independent patients.27 The caregiver burden was higher among caregivers of PD patients with mental health symptoms, similar to other patients with neurodegenerative diseases like AD.14 Furthermore, the same study showed an association between depression and high burden among caregivers affecting their QoL. Additionally, in a study that investigated the burden among Chilean caregivers of PD patients by using the ZBI and Beck Depression Inventory, they found a high rate of depression among caregivers of older PD patients and those who have balance or gait abnormalities and cognitive impairment.28 Lastly, more advanced disease was significantly associated with higher depression among caregivers.29

The role of coping strategies is crucial because effective coping strategies can enhance caregivers’ mental health, leading to a positive impact on their QoL and ultimately improving patient care. Among Saudi caregivers of patients with chronic diseases, various coping strategies have been suggested. A study conducted among stroke patients and their caregivers revealed that social support, particularly from friends, was linked to lower scores of depression and anxiety, contributing to a better QoL. Additionally, the existential type of spiritual coping strategy has been associated with good QoL and a reduced risk of depression.30 Unfortunately, there is a lack of data among PD caregivers.

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small. Second, the lack of further demographic information for caregivers, including marital status, level of education, economic status, and duration of care, might impact the burden score. Additionally, the participants in the study were not screened for any mental health issues that could serve as a confounding factor in the study’s findings. Third, patients’ disease history, duration of diseases, and the number of medications the patients were on could have significant associations with high burden, as seen in previous studies. Fourth, we utilized the DASS-8 scale to assess the levels of depression, anxiety, and stress among caregivers. Despite the availability of more comprehensive scales, we opted for this scale to ensure the questionnaire’s length was manageable for participants, allowing them to complete the questions more easily. Lastly, this study was a cross-sectional study where data collection was done anonymously through an electronic self-administered questionnaire. Unfortunately, we were not able to provide any intervention to address the psychological burden among PD caregivers or provide them with possible coping strategies. Despite these limitations, our study is the first in Saudi Arabia to assess the disease burden and psychological aspects among PD caregivers, who play a significant role in patient care and support.

Conclusion

Our study showed that caring for female PD patients, or PD patients with coexisting dementia or memory impairment, decreased mobility, or those who are dependent on their ADLs were significantly associated with higher risks of caregiver burden. Additionally, PD caregivers who are at high risk of caregiver burden are those who are brothers or sisters and provide daily caregiving. The risk of depression, anxiety, or stress is higher among female caregivers. Finally, conducting more extensive future studies focusing on the burden experienced by caregivers in relation to PD is crucial. These studies are essential for gaining a deeper understanding of the scope of the problem and for further research aimed at enhancing the QoL for both caregivers of PD patients and, ultimately, the patients themselves. Such research efforts can also guide the allocation of resources more effectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Prince Naif Bin AbdulAziz Health Research Center (PNHRC) at King Saud University (KSU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for providing statistical analysis support.

FUNDING

This project was funded by Dallah HealthCare, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Grant number (CMRC-DHG-4/002).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

1. | Balestrino R and Schapira AHV. Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol (2020) ; 27: : 27–42. |

2. | Simon DK , Tanner CM and Brundin P . Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clin Geriatr Med (2020) ; 36: : 1–12. |

3. | Ashok PP , Radhakrishnan K , Sridharan R and Mousa ME . Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease in Benghazi, North-East Libya. Clin Neurol Neurosurg (1986) ; 88: : 109–113. |

4. | Lee A and Gilbert RM. Epidemiology of Parkinson disease. Neurol Clin (2016) ; 34: : 955–965. |

5. | al Rajeh S , Bademosi O , Ismail H , et al. A community survey of neurological disorders in Saudi Arabia: the Thugbah study. Neuroepidemiology (1993) ; 12: : 164–178. |

6. | Ishihara LS , Cheesbrough A , Brayne C , et al. Estimated life expectancy of Parkinson’s patients compared with the UK population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2007) ; 78: : 1304–1309. |

7. | Xu J , Gong DD , Man CF , et al. Parkinson’s disease and risk of mortality: meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Neurol Scand (2014) ; 129: : 71–79. |

8. | McClement SE and Woodgate RL. Research with families in palliative care: conceptual and methodological challenges. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) (1998) ; 7: : 247–254. |

9. | Martinez-Martin P , Rodriguez-Blazquez C and Forjaz MJ. Quality of life and burden in caregivers for patients with Parkinson’s disease: concepts, assessment and related factors. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res (2012) ; 12: : 221–230. |

10. | Boersma I , Jones J , Coughlan C , et al. Palliative care and Parkinson’s disease: caregiver perspectives. J Palliat Med (2017) ; 20: : 930–938. |

11. | Martinez-Martin P , Skorvanek M , Henriksen T , et al. Impact of advanced Parkinson’s disease on caregivers: an international real-world study. J Neurol (2023) ; 270: : 2162–2173. |

12. | Kluger BM , Miyasaki J , Katz M , et al. Comparison of integrated outpatient palliative care with standard care in patients with Parkinson disease and related disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol (2020) ; 77: : 551–560. |

13. | Alshammari SA , Alzahrani AA , Alabduljabbar KA , et al. The burden perceived by informal caregivers of the elderly in Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med (2017) ; 24: : 145–150. |

14. | Schrag A , Hovris A , Morley D , et al. Caregiver-burden in parkinson’s disease is closely associated with psychiatric symptoms, falls, and disability. Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2006) ; 12: : 35–41. 20051103. |

15. | Nene D and Yadav R. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease: mitigating the lack of awareness!. Ann Indian Acad Neurol (2020) ; 23: : 575–576. |

16. | Smith ER , Perrin PB , Tyler CM , et al. Parkinson’s symptoms and caregiver burden and mental health: a cross-cultural mediational model. Behav Neurol (2019) ; 2019: : 1396572. |

17. | Bachner YG. Preliminary assessment of the psychometric properties of the abridged Arabic version of the Zarit Burden Interview among caregivers of cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs (2013) ; 17: : 657–660. |

18. | Hébert R , Bravo G and Préville M. Reliability, Validity and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can J Aging (2000) ; 19: : 494–507. |

19. | Ali AM , Hori H , Kim Y and Kunugi H. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8-Items expresses robust psychometric properties as an ideal shorter version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 among healthy respondents from three continents. Front Psychol (2022) ; 13: : 799769. |

20. | Kalampokini S , Hommel A , Lorenzl S , et al. Caregiver burden in late-stage parkinsonism and its associations. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol (2022) ; 35: : 110–120. |

21. | Tessitore A , Marano P , Modugno N , et al. Caregiver burden and its related factors in advanced Parkinson’s disease: data from the PREDICT study. J Neurol (2018) ; 265: : 1124–1137. |

22. | Shin H , Lee JY , Youn J , et al. Factors contributing to spousal and offspring caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease. Eur Neurol (2012) ; 67: : 292–296. |

23. | Lee GB , Woo H , Lee SY , et al. The burden of care and the understanding of disease in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One (2019) ; 14: : e0217581. |

24. | Rosqvist K , Schrag A , Odin P , et al. Caregiver burden and quality of life in late stage Parkinson’s disease. Brain Sci (2022) ; 12: : 20220114. |

25. | Alfakhri AS , Alshudukhi AW , Alqahtani AA , et al. Depression among caregivers of patients with dementia. Inquiry (2018) ; 55: : 46958017750432. |

26. | Alqahtani MS , Alshbriqe AA , Awwadh AA , et al. Prevalence and risk factors for depression among caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients in Saudi Arabia. Neurol Res Int (2018) ; 2018: : 2501835. |

27. | Ali AM , Alameri RA , Hendawy AO , et al. Psychometric evaluation of the depression anxiety stress scale 8-items (DASS-8)/DASS-12/DASS-21 among family caregivers of patients with dementia. Front Public Health (2022) ; 10: : 1012311. |

28. | Benavides O , Alburquerque D and Chaná-Cuevas P. Evaluación de la sobrecarga en los cuidadores de los pacientes con enfermedad de Parkinson ambulatorios y sus factores de riesgo. Rev Méd Chile (2013) ; 141: : 320–326. |

29. | Razali R , Ahmad F , Rahman FN , et al. Burden of care among caregivers of patients with Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg (2011) ; 113: : 639–643. |

30. | Alquwez N and Alshahrani AM. Influence of spiritual coping and social support on the mental health and quality of life of the Saudi informal caregivers of patients with stroke. J Relig Health (2021) ; 60: : 787–803. |