Patient Empowerment for Those Living with Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) poses a number of challenges for individuals, affecting them physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially. The complex nature of PD necessitates empowering patients to address their unique needs and challenges, fostering improved health outcomes and a better quality of life. Patient empowerment is a multifaceted concept crucial to enhancing healthcare outcomes, particularly in chronic conditions such as PD. However, defining patient empowerment presents challenges due to its varied interpretations across disciplines and individuals. Essential components include access to information, development of self-care skills, and fostering a supportive environment. Strategies for patient empowerment encompass health literacy, education, and shared decision-making within a trusted healthcare provider-patient relationship. In PD, patient empowerment is crucial due to the disease’s phenotypic variability and subjective impact on quality of life. Patients must navigate individualized treatment plans and advocate for their needs, given the absence of objective markers of disease progression. Empowerment facilitates shared decision-making and enables patients to communicate their unique experiences and management goals effectively. This paper provides a comprehensive overview of the dimensions and strategies associated with patient empowerment, its definition and the facilitators that are necessary, emphasizing its critical importance and relevance in Parkinson’s management. At the end of this review is a personal perspective as one of the authors is a person with lived experience.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a complex interplay of motor and non-motor symptoms, impacting more than 6 million people globally, a number set to double by 2040,1 posing significant challenges to both patients and healthcare systems worldwide.

Although classified as such, PD is far from solely a motor disorder; it encompasses a wide spectrum of non-motor symptoms such as cognitive impairment, mood disturbances, sleep disturbances, autonomic dysfunction, and sensory abnormalities, significantly impacting the overall quality of life of affected individuals—physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially.

Despite decades of research, PD remains incurable, with current treatments focusing primarily on alleviating symptoms and improving quality of life. Moreover, the heterogeneous nature of PD presents unique challenges in disease management, as individuals exhibit considerable variability in symptom presentation, disease progression, and treatment response. And the degree of that impact varies from person to person, depending on many factors— age, symptoms, level of disability, complications, prognosis, socioeconomic pressures and other psychosocial variables. This results in a significant challenge when it comes to optimizing health care outcomes and as such, quality of life for those living with this diagnosis.

In this context, the concept of patient empowerment emerges as a promising approach to optimize PD care, a powerful and necessary determinant of health behavior.2 Patient empowerment encompasses the acquisition of knowledge, skills, motivation, and self-awareness necessary for individuals to actively participate in decision-making processes regarding their health. By empowering patients to become active partners in their care, healthcare providers can enhance treatment adherence, improve symptom management, and ultimately, promote better health outcomes.

This paper aims to explore the dimensions and strategies associated with patient empowerment in the context of PD. By synthesizing insights from existing literature and clinical practice, we seek to elucidate the role of patient empowerment in enhancing PD management and improving the overall quality of life for individuals living with this challenging condition.

WHAT IS PATIENT EMPOWERMENT?

General “empowerment” movements have permeated throughout society over the past few decades, seeping their way through business, activist, sociopolitical, and educational contexts. In the field of medicine, the concept of patient empowerment is nebulous in its historical origins. In North America patient autonomy can be traced back to the 18th and 19th centuries, as social attitudes shifted towards individualism, prompting a desire for freedom and individual rights in all aspects of life, including health.3 This early iteration of the “patient empowerment” movement manifested as people putting more focus on their everyday decisions and actions, to pre-empt the need for medical attention. Since that time, the definition of patient empowerment has expanded and is now an important construct in the area of chronic illness management.

A catch-all, notoriously difficult to define term, “patient empowerment” may mean something different not only depending on the field in which it is fostered, or the individual being empowered, but also to the researcher attempting to define it4 leading to a broad range of definitions in the literature. Following a metanalysis of 276 studies looking at the spectrum of meanings given to the term patient empowerment,5 the authors of that review suggested a more comprehensive definition, describing this construct as “the acquisition of motivation (self-awareness and attitude through engagement) and ability (skills and knowledge through enablement) that patients might use to be involved or participate in decision-making, thus creating an opportunity for higher levels of power in their relationship with professionals”.

A multi-faceted concept, patient empowerment encompasses many dimensions that must be present in order to be successful. A patient’s state or their “possession of knowledge, skills, attitudes and self-awareness,” must be present to allow for the process of making health-related choices and self-care.5 There also needs to be a process that allows the patient to achieve that state, “a type of support that enables and motivates people to take necessary steps to manage and improve their health in a self-directed manner.”6 or more simply part of a “process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health”.7 And lastly empowerment for patients requires an opportunity to participate in shared decision-making regarding health and to assume responsibility for self-management5 or what the World Health Organization (WHO) refers to as patient participation.

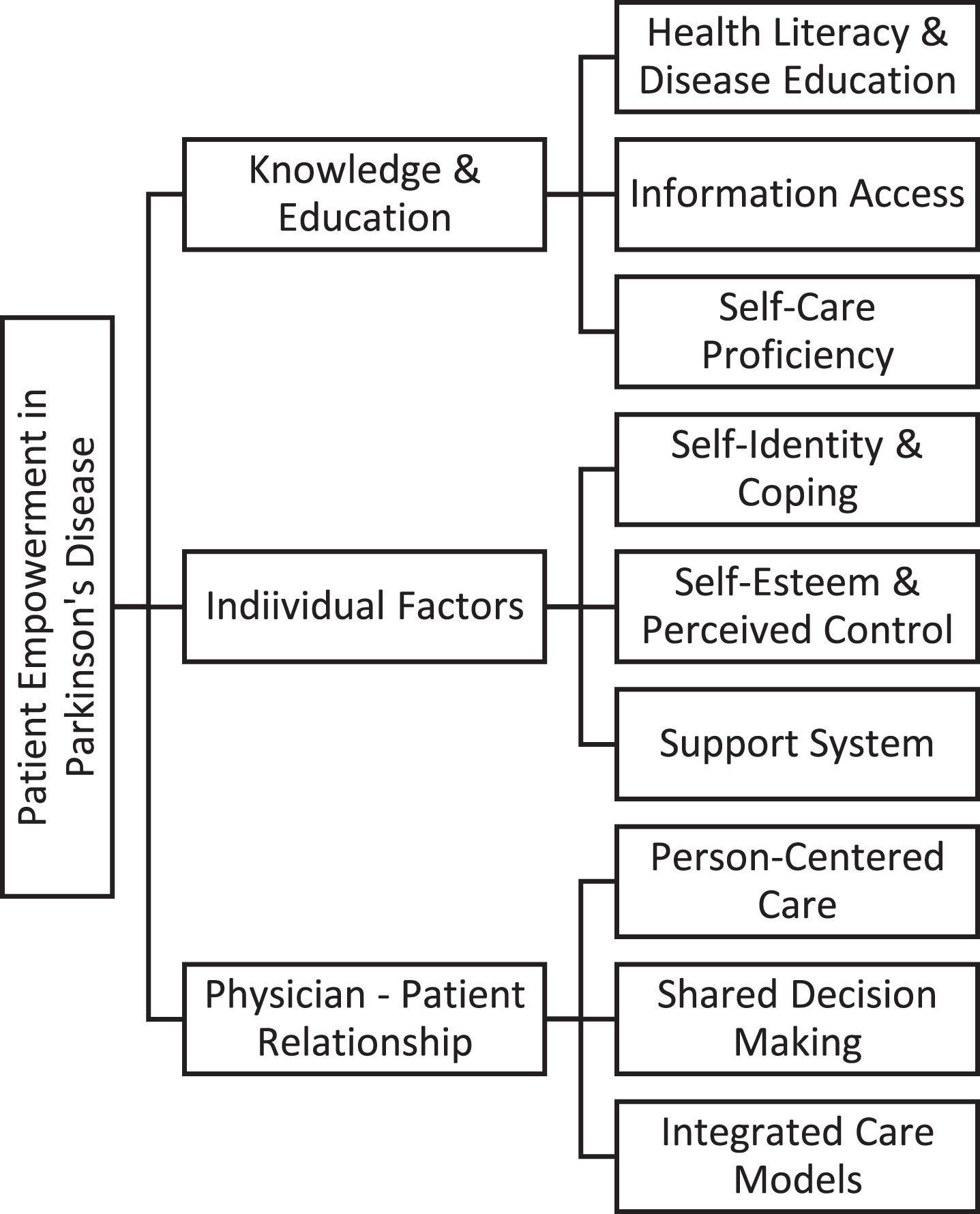

How can this best be achieved? When it comes to strategies that facilitate patient empowerment the WHO recognizes fundamental components that individuals and communities need to develop to foster patient empowerment and the involvement of patients in their own health care. These include access to resources and acquisition of relevant information, the development of skills required to act on that knowledge and the presence of a facilitating environment.7 Strategies to facilitate patient empowerment should therefore include health literacy and education, cognitive interventions to support patient’s skills and confidence and shared decision-making through a trusted health care provider-patient relationship (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Dimensions and Strategies of Patient Empowerment in Parkinson’s Disease Management. This diagram illustrates the multifaceted nature of patient empowerment in Parkinson’s disease management. The three main sections depict Knowledge and Education, Psychological Factors, and Physician-Patient Relationship, each comprising specific components essential for promoting patient-centered care and improving outcomes.

HEALTH LITERACY AND EDUCATION

“Scientia potential est” is a Latin aphorism meaning “knowledge itself is power”. Dating back to 1597, Sir Francis Bacon was referring to the practical value of learning and how sharing knowledge was the cornerstone of influence. Sharing knowledge in the setting of chronic disease should include information about the disease itself – symptoms, pathophysiology, prognosis, medical and surgical treatments (and their potential risks) and most importantly, principles of self-care. In fact, self-care proficiency can be a more significant factor than disease or treatment knowledge beyond the basic understanding, to enhance patient empowerment in PD.8 This self-care knowledge influences patients to become active participants in their own care, taking control of variables such as diet, exercise, sleep, stress management, symptom and treatment tracking, all in an effort to positively impact quality of life.9 This type of knowledge acquisition does not rest in the realm of the health care provider alone. Patients must become active participants in this educational process, seeking out resources, recognizing knowledge deficiencies and asking relevant questions and particularly learning about which variables are controllable and allow for an improvement in life experience.

A recent study conducted in the UK, explored the value of a therapeutic education for empowerment and engagement in patients with PD which included information on motor complications, nonmotor symptoms including gastrointestinal, neuropsychological symptoms, autonomic dysfunction and medication and rehabilitation management. Supported by an improvement in all quality of life measures they found that those that participated in the program, had a significant reduction in daily off time compared with those that did not. There was also an improvement in non-motor symptoms and functional independence.10 In general, patient education interventions seem to improve medical outcomes, adherence to treatment plans and improved disease self-management skills as needs evolve.

The purpose of empowerment-based education is to teach critical thinking to patients that allows them to participate in shared decision-making, when assessing disease status and treatment options, to make informed choices.11 For the provider this means creating an educational program that is tailored to each patient’s needs, their level of health literacy, and their life priorities. Information that uses non-medical terminology and encourages questions is also important and must take into consideration an individual’s psychosocial stressors and cultural influences. Using effective communication techniques that will adapt to the patient’s understanding is imperative and this may be in the form of verbal, written or online resources.12 With regards to online resources, health care providers must also be vigilant that their patients are using trusted and curated resources given the immense amount of information, some of which may be inaccurate, that is easily accessible to patients.

But knowledge is only part of the equation to enhance patient empowerment. It was traditionally thought that knowledge was the precedent to empowerment and that by increasing patient’s health literacy, empowerment would naturally follow. However, it seems that a high level of health literacy does not presuppose increased empowerment.13

The Health Empowerment Model14 is predicated on the concept that health empowerment does not assume health literacy or vice versa and that both are necessary to ensure the best health outcomes. Without knowledge, people living with the disease may not be positioned to make informed choices. When patients lack empowerment or health literacy in any combination, poorer health status will result compared to the status of effective self-managers who have both attributes.15 Missing both attributes may create high-needs patients that require complete physician guidance, and knowledge without empowerment may create similar dependence.

Although knowledge underpins empowerment, the most concerning circumstance is, when that knowledge is not always sufficient in those that feel empowered.16 It is relevant to note that in some instances, patient empowerment without adequate information can result in a lower standard of care if a patient’s desire runs opposite to a physician’s care plan and can make a patient more comfortable in challenging medical advice with limited background in the subject. Patient empowerment without the knowledge needed to make informed health decisions can in fact be inappropriate or even harmful.

Effective patient education interventions, tailored to individual needs and delivered in accessible formats, have shown promising results in improving quality of life and disease management. When achieved, true patient empowerment, which includes said relevant health literacy, results in better self-management and self-care along with increased quality of life.17 However, empowerment extends beyond knowledge attainment, necessitating the development of personal constructs such as self-esteem and perceived control.

PATIENT SKILLS AND INDIVIDUAL FACTORS IN EMPOWERMENT

And since empowerment can be a difficult concept to measure directly, researchers often use associated concepts such as self-efficiency, self-esteem, self-efficacy, factors that patients have or develop as an outcome measure for empowerment.18

Patients themselves have identified,15,19,20 a number of factors they consider important for their own empowerment. Some are external or interpersonal and necessary to help navigate the medical system and others are more internal or individual, applying to daily life decisions and actions. Empowered patients have an intrinsic sense of perceived control and perceived competence.21 Perceived control can be viewed as a patient’s belief that they are able to make the decisions that are necessary regarding their health. And perceived competence is the patient’s belief that they can do what is needed and necessary to implement those decision and take care of their own health, that their own actions or interventions will have a positive impact. Self-esteem is a part of that intrinsic state, self-worth and self-value being important factors that are positively correlated with patient empowerment as is a sense of inner strength.17,22 This results in patients believing they are able to change life for better by making the right decisions regarding their health, direct attention to self-care, better lifestyle choices and less risky behavior.8

But that sense of perceived control and competence is not always easy to attain. PD is a difficult diagnosis to face given its inevitable progression, unrelenting neurodegeneration with no cure in the near future. In chronic illness, the burden of the potential challenges that patients may face, can have devastating effects on an individual’s identity and sense of continuity, when compared to their sense of self and what they believed their life trajectory could be prior to diagnosis. Patients often experience an intrinsic feeling of insecurity in their personal identity and that psychological stress of threatened sense of self must be addressed to foster the development of an empowered state.23

An important step in restructuring one’s self-identity and seeing one’s continued value, involves differentiating oneself from the disease, compartmentalizing and recognizing that the disease does not define an individual but is an integral part of life.22 The ability to look beyond the disease and differentiating oneself from the diagnosis is an important step in restructuring one’s self-identity and seeing one’s continued value.23 Part of psychological coping, accepting, or framing this illness, is developing an outlook and the necessary skills in the context of personal, family, cultural and spiritual beliefs.

Along with differentiating themselves from the diagnosis there needs to be an acknowledgement and integration of the likely functional boundaries that the disease places, in order for patients to feel empowered. PD is one of neurodegeneration, and the challenges that it brings to the lives of those diagnosed, is relentlessly progressive. It may take some work on the part of the patient and sometimes with counseling from a health care professional, to re-identify and renew a sense of self in the new context of illness.23

A strong support system is also identified as an important factor in patient empowerment, from loved ones to peers. That feeling of not being alone, being able to depend on family and friends for daily physical and emotional support lends to the feeling of empowerment as does the support of others who either understand or who themselves have experienced similar life challenges. And participating in meaningful activities outside of illness management, can also be empowering. Feeling useful, being part of the community and having a sense of purpose can act to counter the stigmatized view of disability that many patients hold.

PHYSICIAN-PATIENT RELATIONSHIP

Although evolving, the relationship between doctor and patient has traditionally been rather paternalistic. This “medical model” of health care consists of evaluating symptoms and complaints, prescribing treatments, and assessing outcomes— typically with a doctor or some other highly trained professional making the decisions.24 Simply put, the role of the professional is to decide; the role of the patient is to comply with the decisions of the professional.

This traditional process of disease management is driven by the clinician, and the lack of options and consultation leaves patients feeling disempowered in their own care.25 Current care practices tend to be more reactive than proactive, often lack continuity of care and are not often personalized, based on specific needs and a collaborative relationship between people living with the disease and their healthcare team.2 It essentially delegitimizes the patient’s role in management of their health and legitimacy is of utmost importance with regards to patient interactions with healthcare providers. Patients do not want to be objectified in the context of their disease but seen as a whole person, experts in their own illness journey and want to be respectfully recognized, with their concerns and observations, validated through active listening, acknowledgement, authenticity, and encouragement.26

As stated by Anderson et al.11 when speaking to diabetes care “We believe that HCPs are responsible for helping patients achieve their goals, and overcome barriers through education, appropriate care recommendations, expert advice, self-reflection and social and self-management support.” It is the goal of the HCP (healthcare professional) to provide the patient with the knowledge that they need to make informed decisions about their health in the context of their own life experience. Empowerment is not something that can be given to a patient, but through appropriate education and thoughtful interaction, it is something that the HCP and team can facilitate or help develop and create.17 That is critical to patient empowerment and forms the natural basis of patient-centered care.

Person-centered care is more in line with patient empowerment, putting people in the center of care plan development, working collaboratively, taking into consideration their context, their history, their family, and individual strengths, and weaknesses.27 It also means a shift from viewing the patient as a passive target of a healthcare system to another model where the patient is an active part in his or her care and decision-making. Person-centered approaches emphasize the importance not just of diagnoses and physical and medical needs but also of social, mental, emotional, and spiritual needs; seeing the world from the perspective of the person with the condition being treated; applying knowledge of the individual (biological, behavioral, biographical, and social aspects) to tailor care through shared decision-making. Because although physicians may know what is best for a patient’s disease, they may in fact be unaware of what is important in the context of that individual’s life.11

There are also many factors that exist outside the healthcare sphere that can impact the level of empowerment a patient feels inside of it, such as cultural background, economic status, gender, past experience with the medical system and personal resources. To not address these and instead focus solely on the brief moments a patient may spend in a hospital or with a physician is to neglect the majority of background that inevitably contributes to how a patient approaches management recommendations. For patients to feel empowered to collaborate, there must be a trusting and respectful relationship between themselves and their medical professional.

If a basic idea of what empowerment is can be described as “a redistribution of power from the powerful to the powerless”, then patient empowerment in a medical context involves a shift in the balance of power between health care provider and patient, resulting in increased patient autonomy; a redistribution of power between physician and patients. This shift in control increases patient participation in health-related decisions in order to improve health outcomes.28 What exactly this entails is extremely individual to each patient, which explains why it is so difficult to implement on a structural level. For some patients it is enough to be more medically informed to feel empowered, for others, it involves decision-making on every level. For some, empowerment might mean a trusted family member taking over for care and decision-making. Generally, it is not about the actual decision being made as much as it is about the patient’s ability to decide the degree to which they would like to participate in the decision-making process.

Integrated models of care are being developed with these factors in mind, to enhance healthcare delivery using a person-centered perspective, prioritizing empowerment thereby improving quality of life for patients.29 For example, health care professionals from the UK and Netherlands worked together to propose PRIME (Proactive and Integrated Management and Empowerment) in PD, a model of care to manage problems proactively, to provide multidisciplinary care and most importantly to empower patients and those that care for them.30 ParkinsonNet in the Netherlands is another example of an integrated care model providing multidisciplinary collaboration, specially trained professionals, and again patient empowerment through educational programming, online support communities and including the patient voice in research.31 Moving forward, efforts to promote patient empowerment in PD should prioritize the development and implementation of integrated care models that facilitate proactive management, multidisciplinary collaboration, and person-centered approaches.

ONE PATIENT’S PERSPECTIVE: WHY IS PATIENT EMPOWERMENT IMPORTANT IN PARKINSON’S DISEASE?

Empowerment is not a disease specific construct but patient empowerment in general is a well-established predictor of several patient health outcomes. Improved disease management and patient satisfaction result from being involved in disease management decisions32 and effective use of health services and improved health status are also benefits15 in part due to medication adherence which is shown to be improved with patient-physician collaboration. But those of us living with the challenges of PD are also uniquely positioned to benefit from its tenets, given some of the particular challenges that we as patients and our healthcare team, face.

First and foremost, this is a disease of phenotypic variability. There is a saying in the PD community “If you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s, you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s”. People living with PD differ in terms of age and stage of life at diagnosis, symptoms, complications, response and side effects to medications, progression of illness and prognosis. This disparateness in disease manifestation makes it difficult to develop care plans that are universal, as each of us requires our own treatment based on our individual needs, challenges and other factors related to our care resources. As patients, we must be able to identify those unique needs and challenges as well as have understanding of the disease and treatment options in order to change self-care or make informed decisions regarding treatment. This process of self-care and change in action based on knowledge facilitated by a mutual and trusting physician – patient relationship17 is crucial to patient empowerment.

There is also no measurable, objective marker of progression or response to treatment. Our current way of assessing this disease instead is primarily a mix of clinical judgment, scaled rating scores, and retrospective patient reporting. It really is merely a static snapshot in an artificial clinic setting, of the patient’s condition as opposed to objective measurement of symptoms that are inherently variable. Until the development of an accurate classification system that includes objective biomarkers, which would lead to more accurate diagnosis, inform staging and disease trajectory, predict future complications and conclusively direct personalized therapies, we must be empowered as people living with this disease to advocate for our care. Because our narrative and accurate communication of our disease state will guide the management decisions that are made.

The impact of this disease on daily and life goals and the degree of disability is also best measured over time in the context of the patient’s own life. Gender, cultural, geographic, socioeconomic factors and how they influence the experience of this disease, are impactful. And their significance and the communication of that impact is best understood and communicated by the patient, not necessarily assumed to be understood by the health care provider. In other words, the burden of the disease on personal life experience is within the scope of the patient, not necessarily the clinician. Therefore, the ability as a patient to understand, recognize and communicate the repercussions this disease is having on their life experience, and knowledgeably discuss potential treatments in a trusted health care environment, is vital.

Much like the disease, those management goals to improve quality of life will vary from person to person. For some patients this may mean improved mobility to safely navigate their home environment. For others their management goals may include returning to vigorous exercise and sports. Both goals will lead to an improvement in quality of life for that particular individual. Therefore, management must be more in the hands of those affected as only we are aware of what unique and subjective targets, if addressed, will lead to an improvement in our quality of life. And until there is a disease modifying treatment, efforts must be directed towards quality of life.33

The unique presentation of PD, the individual quality of life goals, influencing psychosocial factors that we experience, and the lack of an objective marker to target, are all cumulative and make PD difficult to manage without a partnership based on patient empowerment. Partnering to ensure appropriate and realistic management decisions cannot be made without the recognition and communication of the impact of this disease as well as the knowledge that would be required for shared decision-making.

The significance of patient empowerment in PD lies in its capacity to address the challenges posed by the disease’s phenotypic variability, subjective impact on quality of life, and absence of objective markers for disease progression. Empowered patients are better equipped to navigate individualized treatment plans, advocate for their needs, and communicate their unique experiences and management goals effectively.

CONCLUSION

Patient empowerment emerges as a pivotal paradigm in enhancing healthcare outcomes, particularly in the context of chronic conditions like PD, a challenging, debilitating disease with a significant impact on quality of life for those living with this condition.

Patient empowerment is not a singular concept but a multifaceted construct encompassing motivation, knowledge acquisition, self-awareness, and active participation in collaborative health care practices, as in shared decision making. It represents a cornerstone of effective PD management, offering a pathway towards more personalized, collaborative, and holistic approaches to care delivery. The power of empowerment-based care lies in facilitating change and supporting patients through education and self-reflection in order to make decisions regarding their self-care and disease management through trusted, collaborative and respectful guidance; to create those resources and methods of practice that foster health literacy and knowledge. As research and clinical practices continue to evolve, fostering patient empowerment must remain a central focus to ensure comprehensive and patient-centered care for individuals living with PD. Thus, leading to enhanced health outcomes and ultimately optimizing quality of life for those living with this debilitating condition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no acknowledgments to report.

FUNDING

The authors have no funding to report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Soania Mathur is an Editorial Board member of this journal but was not involved in the peer review process of this article nor had access to any information regarding its peer review.

REFERENCES

1. | Dorsey R , Sherer T , Okun MS , et al. Ending Parkinson’s disease: a prescription for action. 1st ed. New York: Public Affairs, (2020) . |

2. | van der Eijk M , Faber MJ , Al Shamma S , et al. Moving towards patient-centered healthcare for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2011) ; 17: : 360–364. |

3. | Roberts KJ . Patient empowerment in the United States: a critical commentary. Health Expect (1999) ; 2: : 82–92. |

4. | Kang E , Friz D , Lipsey K and Foster ER . Empowerment in people with Parkinson’s disease: A scoping review and qualitative interview study. Patient Educ Couns (2022) ; 105: : 3123–3133. |

5. | Fumagalli LP , Radaelli G , Lettieri E , et al. Patient Empowerment and its neighbours: clarifying the boundaries and their mutual relationships. Health Policy (2015) ; 119: : 384–394. |

6. | Cerezo PG , Juvé-Udina ME and Delgado-Hito P . Concepts and measures of patient empowerment: a comprehensive review. Rev Esc Enferm USP (2016) ; 50: : 667–674. |

7. | WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care Is Safer Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; (2009) . 3, Components of the empowerment process. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144009/ |

8. | Viwattanakulvanid P and Kittisopee T . Influence of disease-related knowledge and personality traits on Parkinson’s patient empowerment. Thai J Pharm Sci (2017) ; 41: : 76–83. |

9. | Soh SE , McGinley JL , Watts JJ , et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: a path analysis. Qual Life Res (2013) ; 22: : 1543–1553. |

10. | De Pandis MF , Torti M , Rotondo R , et al. Therapeutic education for empowerment and engagement in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A non-pharmacological, interventional, multicentric, randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol (2023) ; 14: : 1167685. |

11. | Anderson RM and Funnell MM . Patient empowerment: myths and misconceptions. Patient Educ Couns (2010) ; 79: : 277–282. |

12. | Leep Hunderfund AN and Bartleson JD . Patient education in neurology. Neurol Clin (2010) ; 28: : 517–536. |

13. | Kang E , Friz D , Lipsey K , et al. Empowerment in people with Parkinson’s disease: A scoping review and qualitative interview study. Patient Educ Couns (2022) ; 105: : 3123–3133. |

14. | Camerini L , Schulz PJ and Nakamoto K . Differential effects of health knowledge and health empowerment over patients’ self-management and health outcomes: a cross-sectional evaluation. Patient Educ Couns (2012) ; 89: : 337–344. |

15. | Náfrádi L , Nakamoto K , Csabai M , et al. An empirical test of the Health Empowerment Model: Does patient empowerment moderate the effect of health literacy on health status? Patient Educ Couns (2018) ; 101: : 511–517. |

16. | Schulz PJ and Nakamoto K . Patient behavior and the benefits of artificial intelligence: the perils of “dangerous” literacy and illusory patient empowerment. Patient Educ Couns (2013) ; 92: : 223–228. |

17. | Weisbeck S , Lind C and Ginn C . Patient empowerment: an evolutionary concept analysis. Int J Caring Sci (2019) ; 12: : 1148–1155. |

18. | Galanakis M , Tsoli S and Darviri C . The effects of patient empowerment scale in chronic diseases. Psychology (2016) ; 7: : 1369–1390. |

19. | Chiauzzi E , DasMahapatra P , Cochin E , et al. Factors in patient empowerment: a survey of an online patient research network. Patient (2016) ; 9: : 511–523. |

20. | Agner J and Braun KL . Patient empowerment: A critique of individualism and systematic review of patient perspectives. Patient Educ Couns (2018) ; 101: : 2054–2064. |

21. | Zimmerman MA . Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In: Rappaport J and Siedman E (eds) Handbook of community psychology. Boston, MA: Springer US, (2000) , pp. 43–63. |

22. | Hagiwara E and Futawatari T . A concept analysis: Empowerment in cancer patients. Kitakanto Med J (2013) ; 63: : 165–174. |

23. | Aujoulat I , Marcolongo R , Bonadiman L , et al. Reconsidering patient empowerment in chronic illness: a critique of models of self-efficacy and bodily control. Soc Sci Med (2008) ; 66: : 1228–1239. |

24. | Zizzo N , Bell E , Lafontaine AL and Racine E . Examining chronic care patient preferences for involvement in health-care decision making: the case of Parkinson’s disease patients in a patient-centred clinic. Health Expect (2017) ; 20: : 655–664. |

25. | Bloem BR and Stocchi F . Move for Change Part III: a European survey evaluating the impact of the EPDA Charter for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Eur J Neurol (2015) ; 22: : 133–141. |

26. | Wåhlin I . Empowerment in critical care– a concept analysis. Scand J Caring Sci (2017) ; 31: : 164–174. |

27. | Huber M , van Vliet M , Giezenberg M , et al. Towards a ‘patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open (2016) ; 6: : e010091. |

28. | Cerezo PG , Juvé-Udina ME and Delgado-Hito P . Concepts and measures of patient empowerment: a comprehensive review. Rev Esc Enferm USP (2016) ; 50: : 667–674. |

29. | Bloem BR , Henderson EJ , Dorsey ER , et al. Integrated and patient-centred management of Parkinson’s disease: a network model for reshaping chronic neurological care. Lancet Neurol (2020) ; 19: : 623–634. |

30. | Tenison E , Smink A , Redwood S , et al. Proactive and integrated management and empowerment in Parkinson’s disease: designing a new model of care. Parkinsons Dis (2020) ; 2020: : 8673087. |

31. | Bloem BR , Rompen L , Vries NM , et al. ParkinsonNet: a low-cost health care innovation with a systems approach from the Netherlands. Health Aff (Millwood) (2017) ; 36: : 1987–1996. |

32. | Wroe AL , Salkovskis PM , Rees M , et al. Information giving and involvement in treatment decisions: is more really better? Psychological effects and relation with adherence. Psychol Health (2013) ; 28: : 954–971. |

33. | Andrejack J and Mathur S . What people with Parkinson’s disease want. J Parkinsons Dis (2020) ; 10: (s1): S5–S10. |