Cross-Cultural Differences in Stigma Associated with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Background:

Stigma is an important social attitude affecting the quality of life (QoL) of people with Parkinson’s disease (PwP, PD) as individuals within society.

Objective:

This systematic review aimed to 1) identify the factors associated with stigma in PD and 2) demonstrate culture-based diversity in the stigmatization of PwP. We also reported data from the Turkish PwP, which is an underrepresented population.

Methods:

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, a literature search of the PubMed/Medline electronic database was performed covering the last 26 years. Articles on self-perceived stigma in PD with a sample size > 20 and quantitative results were included. Data were extracted by independent reviewers.

Results:

After screening 163 articles, 57 were eligible for review, most of which were from Europe or Asia. Only two studies have been conducted in South America. No study from Africa was found. Among the 61 factors associated with stigma, disease duration, sex, and age were most frequently studied. A comparison of the investigated factors across the world showed that, while the effect of motor impairment or treatment on stigma seems to be culture-free, the impact of sex, education, marriage, employment, cognitive impairment, and anxiety on stigma may depend on culture.

Conclusion:

The majority of the world’s PD population is underrepresented or unrepresented, and culture may influence the perception of stigma in PwP. More diverse data are urgently needed to understand and relieve the challenges of PwP within their society.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases with diverse clinical manifestations. The progressive nature of PD, as well as the absence of a disease-modifying therapy, indicates an almost inevitable increase in disability throughout the disease course [1]. Evaluating the severity of this disability using conventional symptom-based assessments falls short of depicting the full impact of PD on affected individuals [1]. Therefore, today, more comprehensive and patient-oriented approaches suited to the daily lives of patients have been increasingly recognized. Quality of life (QoL) assessment has become one of the key determinants of the disease-related health status of patients with PD (PwP), as it takes the subjective perception of the individual into account in line with the so-called “patient-focused” approach [2–4]. Accordingly, studies using QoL measures as the main outcome have been increasingly published in the last decades [5–9].

One of the important aspects of QoL determination in PD is stigma, given that it evaluates how having PD affects the individual’s relationship with society she/he lives in [10]. Stigma is a unique feature in the QoL of PwP, as it questions negative interactions between the patient and society including labeling, discrimination, and loss of status [11]. This is a potentially critical issue in the daily life of PwP, as PD is a chronic progressive disease, and stigmatization of PwP in society may lead to long-term and increasing consequences, such as treatment non-compliance, hopelessness, social isolation, or even suicide [12–14]. However, despite these concerns, stigma has been relatively under-investigated in PD [15]. It should also be noted that the pattern and level of stigmatization of PwP are intrinsic to the culture of the given population and, thereby, may well vary across the world. Reports from different countries highlighted elements associated with stigma in PwP; however, few studies have underlined the cultural differences in stigma related to PD [16]. Clarifying this aspect would help to reveal the diversity in stigmatization in PD and enhance the recognition of the culture-specific challenges that PwP experience in their lives. Therefore, in this systematic review, we aimed to investigate the factors associated with stigma in PD and to demonstrate variations in these factors across populations globally. In addition, we report data on stigma in PD from Turkey, which is also a relatively understudied country on this topic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Review questions

This systematic review addresses the following questions:

1. Which factors are associated with stigma in PD?

2. Are there culture-specific differences in the stigmatization of PwP?

Literature search strategy

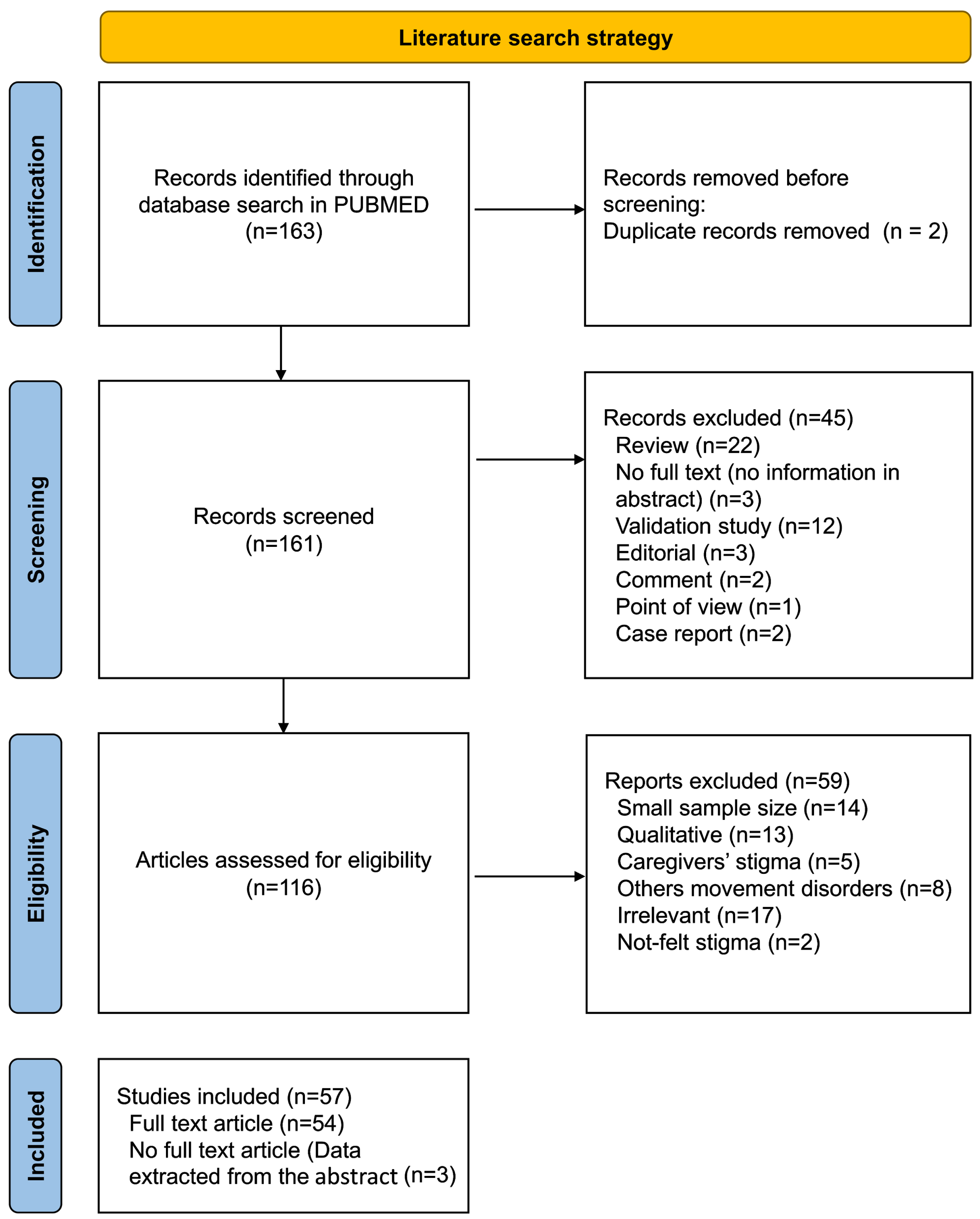

This review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [17]. A literature search in PubMed/Medline electronic database was reviewed for articles published between July 1976 and August 11, 2022 using the search terms: (“social stigma”[MeSH Terms] OR (“social”[All Fields] AND “stigma”[All Fields]) OR “social stigma”[All Fields] OR “stigma”[All Fields] OR “stigmas”[All Fields] OR “stigma s”[All Fields]) AND (“parkinson disease”[MeSH Terms] OR (“parkinson”[All Fields] AND “disease”[All Fields]) OR “parkinson disease”[All Fields] OR “parkinsons”[All Fields] OR “parkinson”[All Fields] OR “parkinson s”[All Fields] OR “parkinsonian disorders”[MeSH Terms] OR (“parkinsonian”[All Fields] AND “disorders”[All Fields]) OR “parkinsonian disorders”[All Fields] OR “parkinsonism”[All Fields] OR “parkinsonisms”[All Fields] OR “parkinsons s”[All Fields]). Excluded were: (i) irrelevant records, (ii) studies with a sample size smaller than 20, (iii) duplicated articles, and (iv) studies with qualitative results. Full texts that were not within our reach were evaluated based on their abstracts. As this review aimed to report data from different regions, articles in languages other than English were evaluated based on their abstracts if written in English. In addition, studies that focused on another outcomes but reported data on stigma were also included. The flow diagram of the literature search is given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Stepwise selection of the studies.

Screening and data extraction

Titles and abstracts of the retrieved publications were equally shared between the two reviewers (AVK and SNK) and single-screened in terms of matching the inclusion criteria. In cases of uncertainty, the full texts were screened. For articles in which uncertainty persisted, consensus was achieved through discussion moderated by a third reviewer (RY). After screening, data extraction from the eligible articles was performed separately by two independent reviewers (AVK and SNK) using a standardized data extraction form. Conflicts in the data were resolved through discussions. The extracted data from the selected publications included: country, sample size, stigma assessment tool, and investigated factors regarding their association with perceived stigma in PD. When not mentioned in the text, the study was counted as belonging to the authors’ country. In case of two consecutive studies from the same group with overlapping data, the last study was included. In multinational studies, the outcomes were extracted for each country separately.

Owing to the high degree of heterogeneity in the study design and data across the included studies, we were unable to quantitatively synthesize the results. Therefore, a qualitative narrative synthesis of the results is conducted. Considering the complexity of the investigated factors, we categorized the investigated effects on stigma into six domains: demographics, motor factors, non-motor factors, treatment effects, other subscales of the PDQ-39, and other factors. In some articles, the median values of the disease severity scores were calculated from the given data to report the study information extensively (Supplementary Table 1). The number of studies for each country is visually displayed on a heatmap on the world map.

Risk of bias assessment

Evaluation to assess the risk of bias for each study was performed according to the presence of potential bias in the study objective, patient selection, ruling out dementia, and statistical analysis (whether the potential confounders were taken into account or not). In the pool of heterogeneous study types, assessments were presented for each selected criterion instead of a single quality score. Three authors (GK, TA, and RY) independently performed the critical appraisal, and a final decision was reached by consensus in unclear cases.

Stigma in Turkey: Patients and clinical assessments

Patients diagnosed with PD according to the UK Brain Bank Criteria were recruited from the Ankara University School of Medicine Department of Neurology between September 2020 and January 2022 as part of a study investigating the prevalence of lysosomal variants in PD. Briefly, detailed data including demographics, comorbidities, and motor and non-motor symptoms were evaluated. QoL was assessed using the PDQ-39 which includes four questions evaluating stigma in PD [18]. Participants with dementia, loss of vision, hearing, or language barriers were excluded. The study was approved by the Ankara University School of Medicine Ethical Committee (approval number: I4-209-20). All procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Statistical analysis

Study data (except the Movement Disorders Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, MDS-UPDRS) were collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Department of Neurology [19]. For reporting the results of the systematic review, no statistical analyses were performed. The distribution of the data from the Turkish cohort was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test and histograms. To investigate the factors associated with stigma in PD, multiple linear regression was performed with the total stigma score in the PDQ-39 as the dependent variable. The regression test was run for females and males separately using a backward method, in which the contribution of each predictor was calculated before removal or inclusion in the final model. Potentially relevant independent variables were chosen based on the literature. The significance threshold was set at p < 0.05. SPSS Statistics software (version 21.0, SPSS Ltd., Chicago, IL, US) was used for analysis.

RESULTS

Stigma in Turkey

Of the 301 participants, 10 were excluded due to missing data on stigma, five were excluded due to communication problems (hearing loss or language barrier), and 54 were excluded due to dementia, leaving 232 to analyze (Table 1).

Table 1

Demographic and disease-related information of the Turkish PwP (n = 232)

| Demographics | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 61.5 (11.7) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 131 (56.5) |

| Education y, mean (SD) | 9.03 (5.0) |

| Family history for PD, n (%) | 37 (15.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.8) |

| Disease-related information | |

| Disease duration, median (range) | 4.0 (0-30) |

| Deep brain stimulation, n (%) | 23 (10) |

| LEDD, mean (SD) | 622.9 (461.5) |

| MDS-UPDRS part-I, mean (SD) | 11.7 (6.6) |

| MDS-UPDRS part-II, mean (SD) | 13.4 (9.5) |

| MDS-UPDRS part-III, mean (SD) | 36.8 (17.2) |

| MDS-UPDRS part-IV, median (range) | 1.0 (0-11) |

| Hoehn &Yahr Stage, median (range) | 2.0 (0-5) |

| Quality of life (PDQ-39) mean (SD) | 49.0 (27.0) |

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 26.7 (1.9) |

| HADS mean (SD) | 12.3 (6.8) |

| Anxiety, mean (SD) | 6.0 (4.0) |

| Depression, mean (SD) | 6.3 (6.0) |

SD, standard deviation; LEDD, levodopa equivalent daily dosage; MDS-UPDRS, Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society –Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; PDQ-39, Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination, HADS, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale.

To evaluate factors associated with stigma in Turkish PwP, a multiple linear regression was performed using a backward stepwise method. Age, education, waist circumference, family history of PD, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, disease duration, MDS-UPDRS-I-IV, Hoehn and Yahr score, PD motor subtypes (TD vs. others, dummy coded), LEDD, MMSE, and depression and anxiety scores of the HADS were included in the model. Regression models were run separately for females and males. After excluding the non-relevant variables, the remaining variables were significantly associated with stigma scores in males, F(3, 70)=7.297, p < 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.21, and in females, F(7,48)=4.804, p < 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.33. For male sex, the model showed significant associations between stigma scores and age, MDS-UPDRS-IV score, and PD subtype. According to the model, a one-point increase in age was associated with a 0.1-point decrease in the stigma score (B=-0.09, 95% CI: -0.17 –-0.20, p = 0.018). The MDS-UPDRS-IV score was positively associated with increased stigma scores (B = 0.22, 95% CI: 0.01 –0.44, p = 0.044). Also, having a TD subtype had a 2.2 times higher likelihood of increased stigma in males (B = 2.21, 95% CI: 0.29 –4.14, p = 0.025). For females, age was also negatively associated with stigma (B=-0.21, 95% CI: -0.35 –-0.10, p = 0.007). Similar to men, those with a TD subtype had a three times higher likelihood of increased stigma (B = 3.04, 95% CI: 0.63 –5.45, p = 0.015). Disease duration, MDS-UPDRS-II score, and waist circumference were also positively associated with stigma scores (B = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.02 –0.37, p = 0.032; B = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.10 –0.28, p = 0.003; B = 0.14, 95% CI: 0.04 –0.25, p = 0.007, respectively). In females, LEDD was negatively associated with stigma scores, with a small effect size (B=-0.005, 95% CI: -0.007 –-0.002, p < 0.001).

Study selection and characteristics

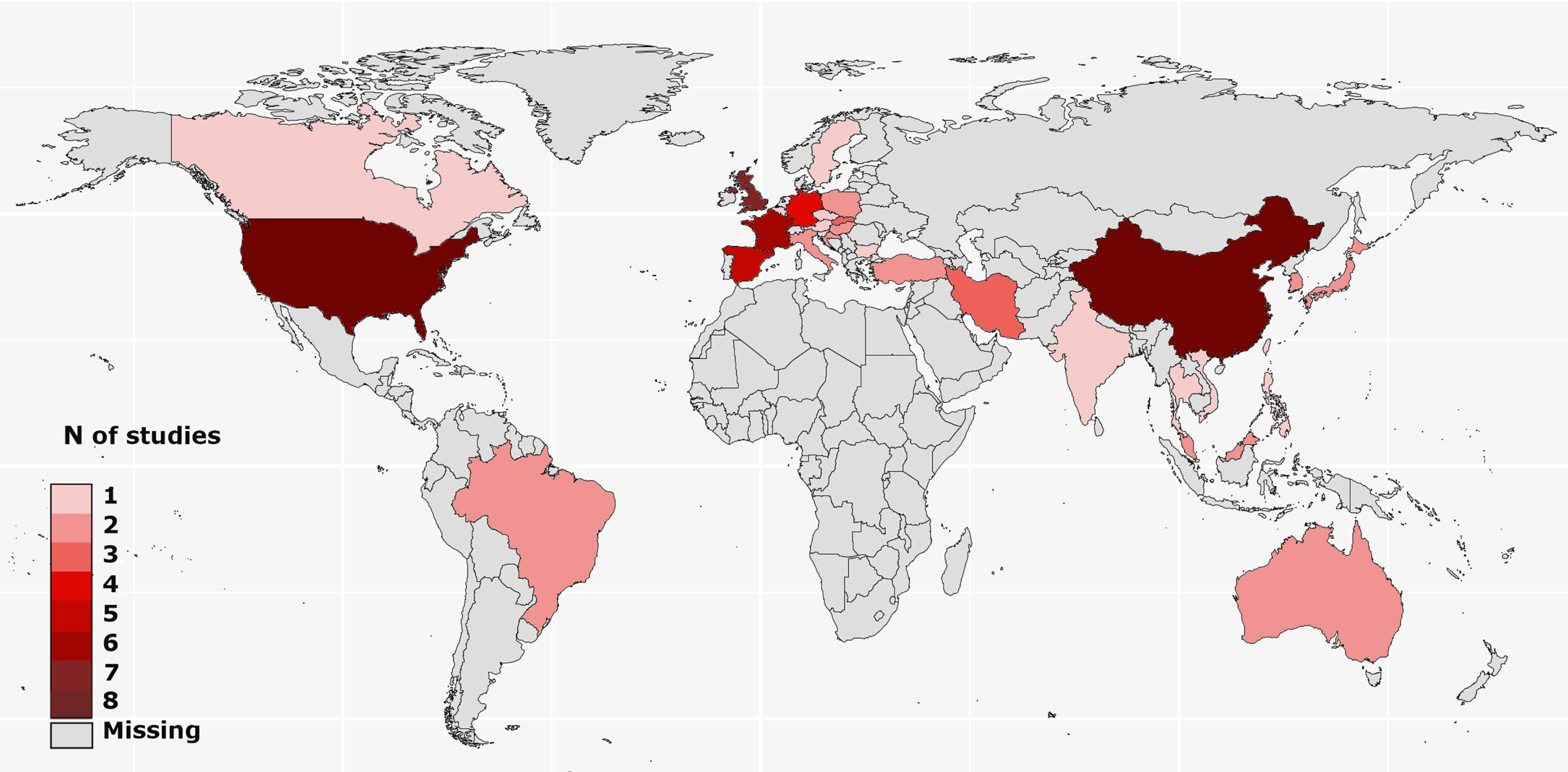

The study selection process followed the PRISMA guideline is given in Fig. 1. The literature search identified 163 studies to screen. The authors agreed that 57 articles were eligible for review. Eight studies were multinational. The included studies provided data from five continents and 32 countries, most of which were from Europe (15 countries, 46.9%) and Asia (13 countries, 40.6%). Nine studies were conducted in North America, one in Canada, and eight in the USA. There were only two studies from South America, both of which were from Brazil. In Oceania, two reports from Australia have been published. No study matching the review criteria was found from Africa (Fig. 2). Data from the included studies are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Fig. 2

Geographical distribution of the studies on stigma in Parkinson’s disease.

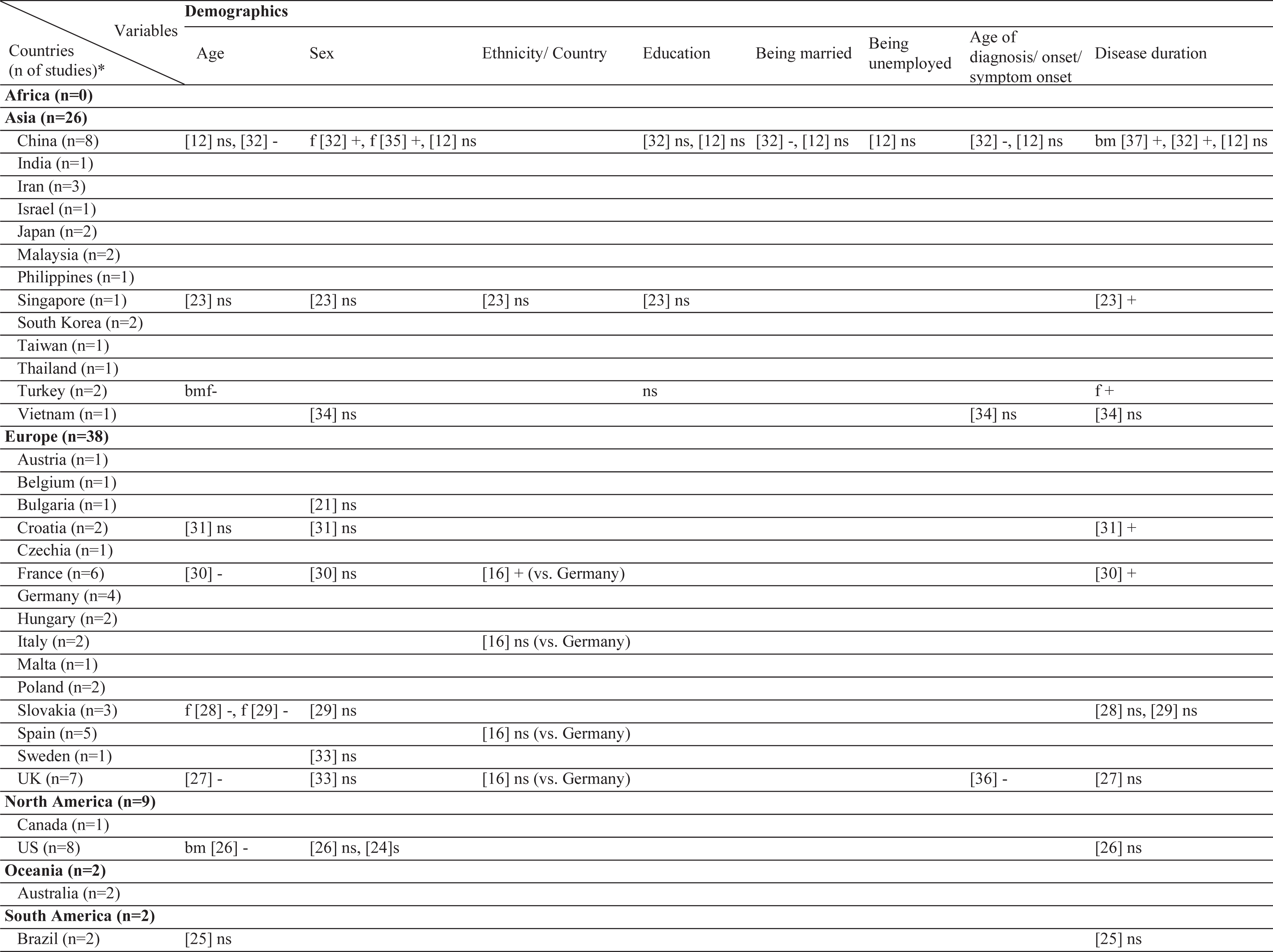

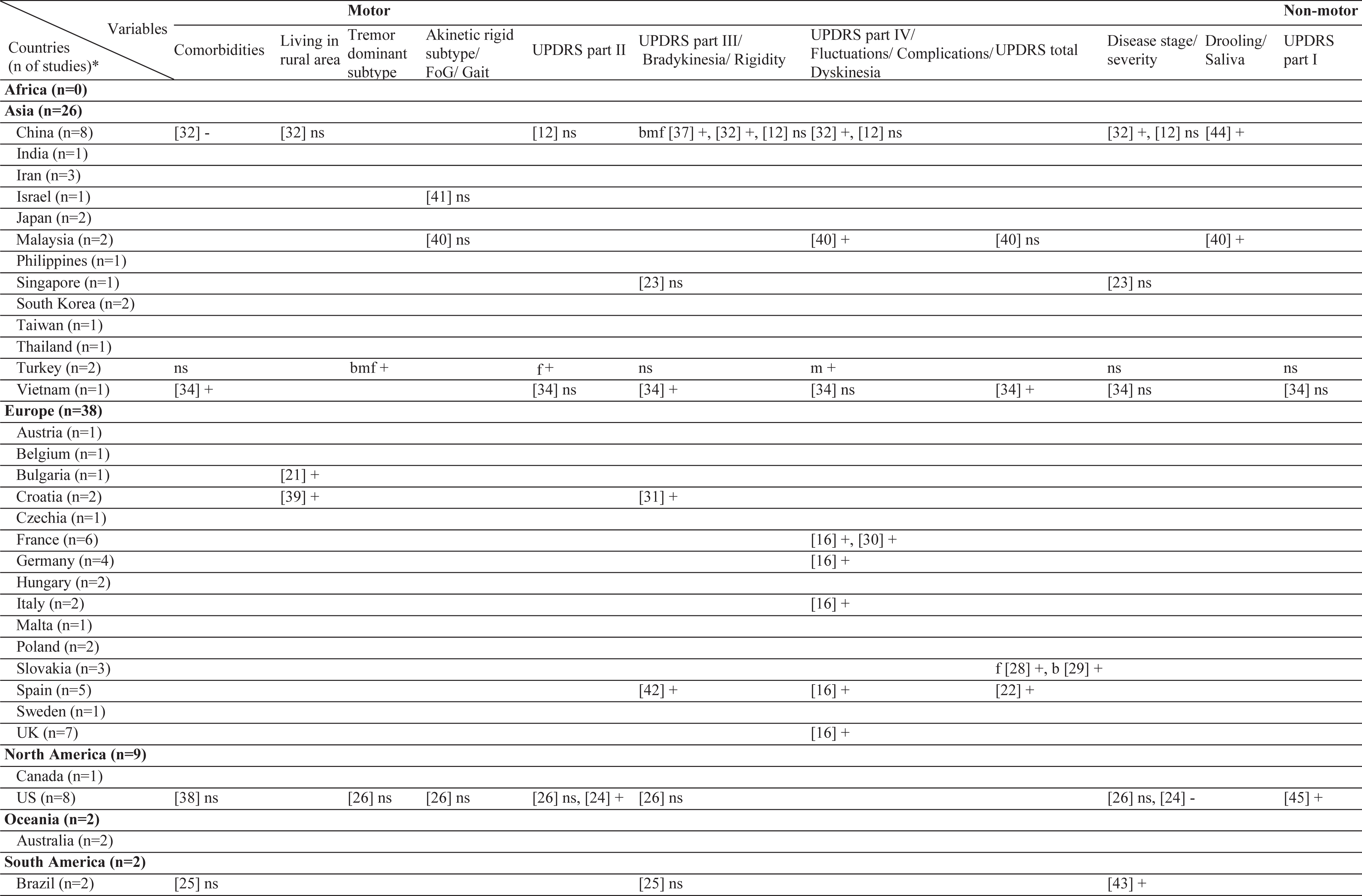

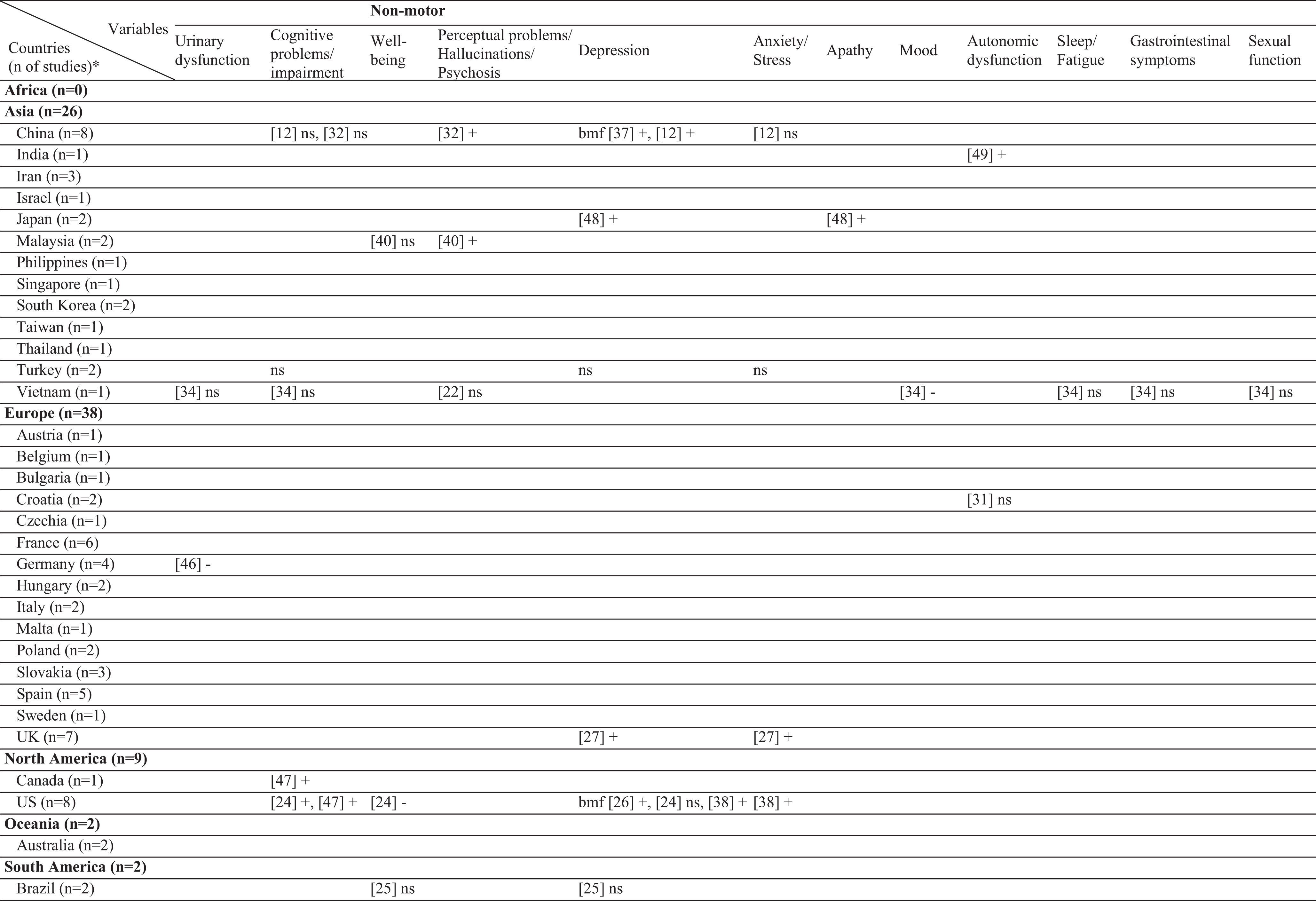

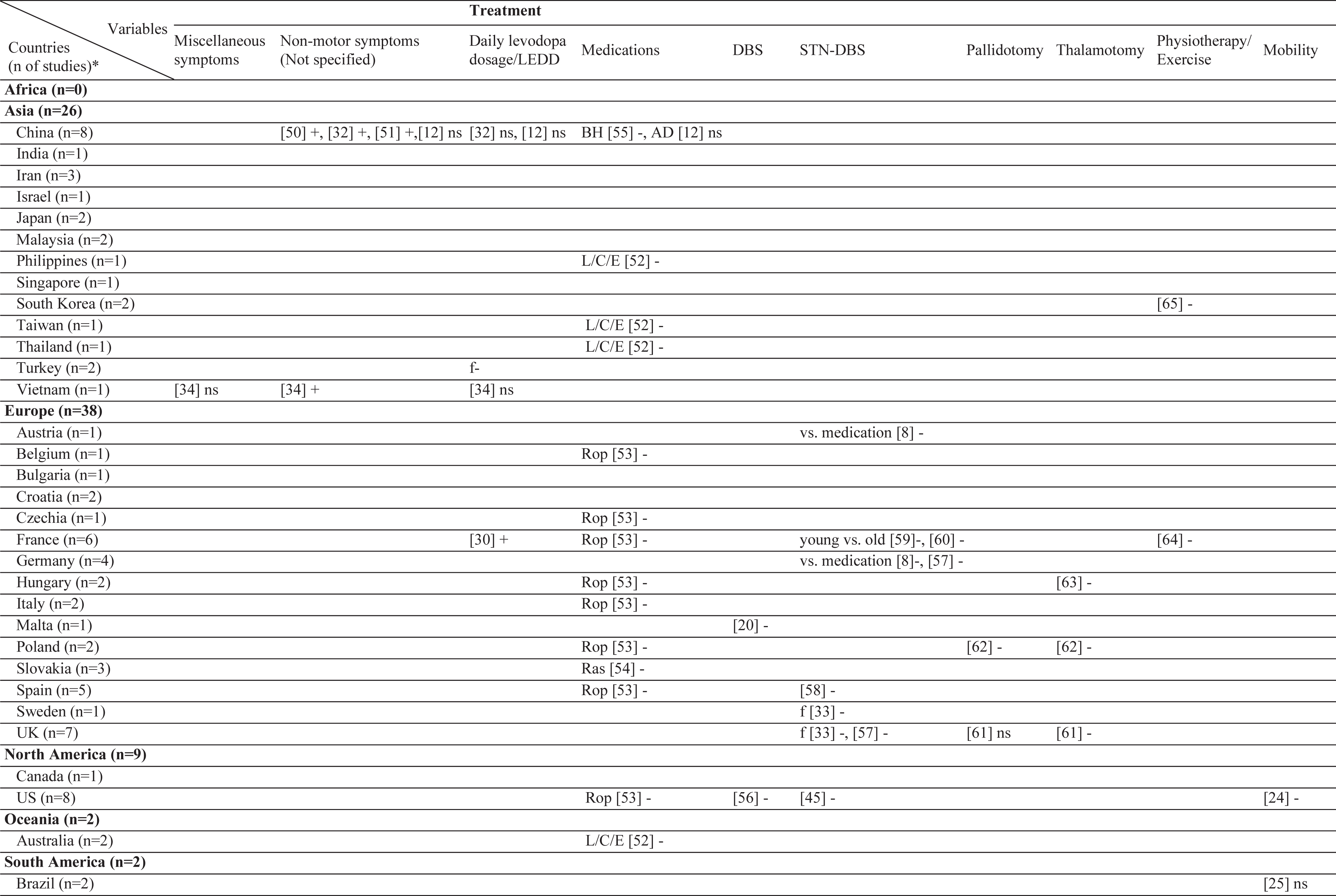

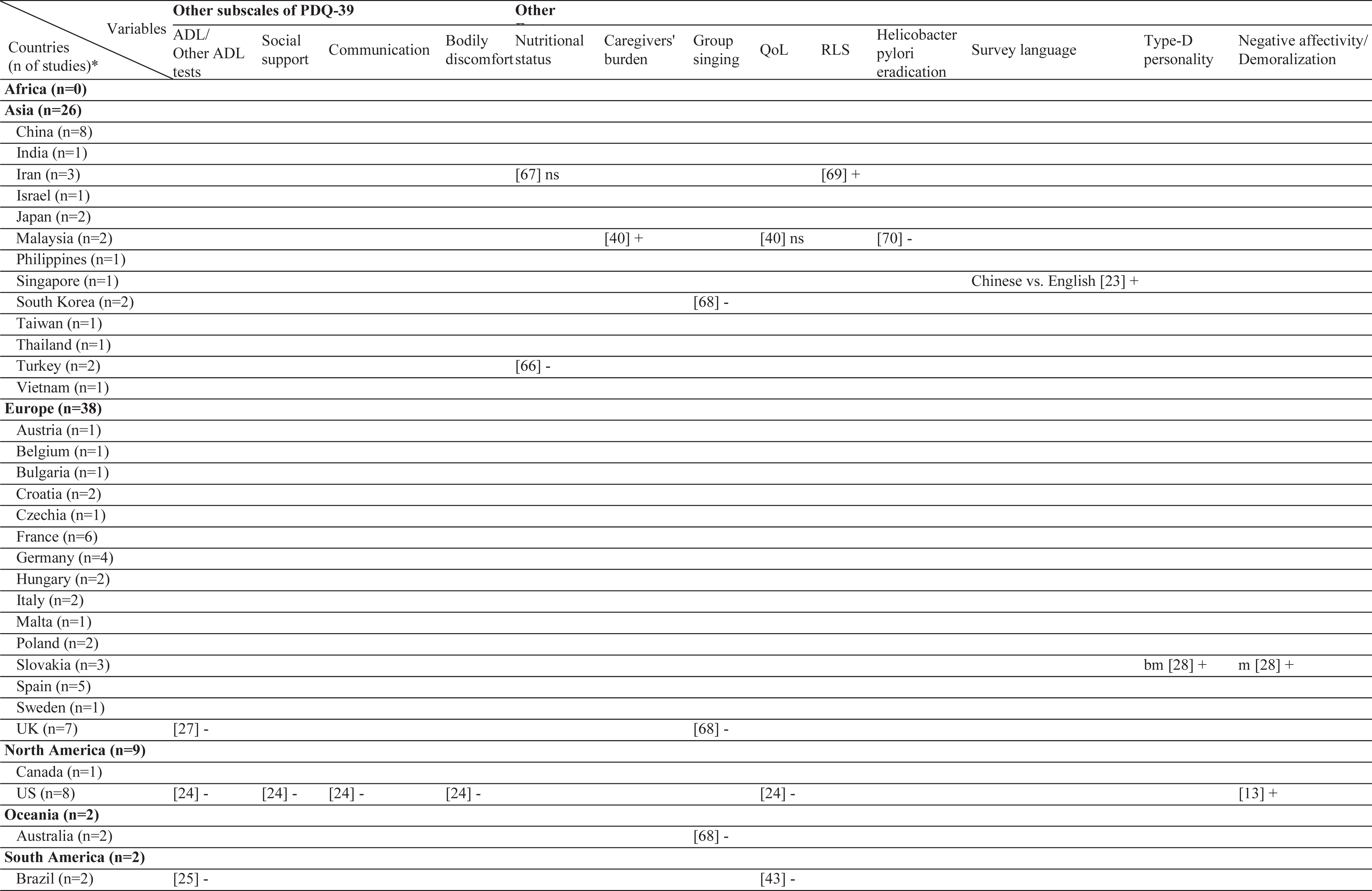

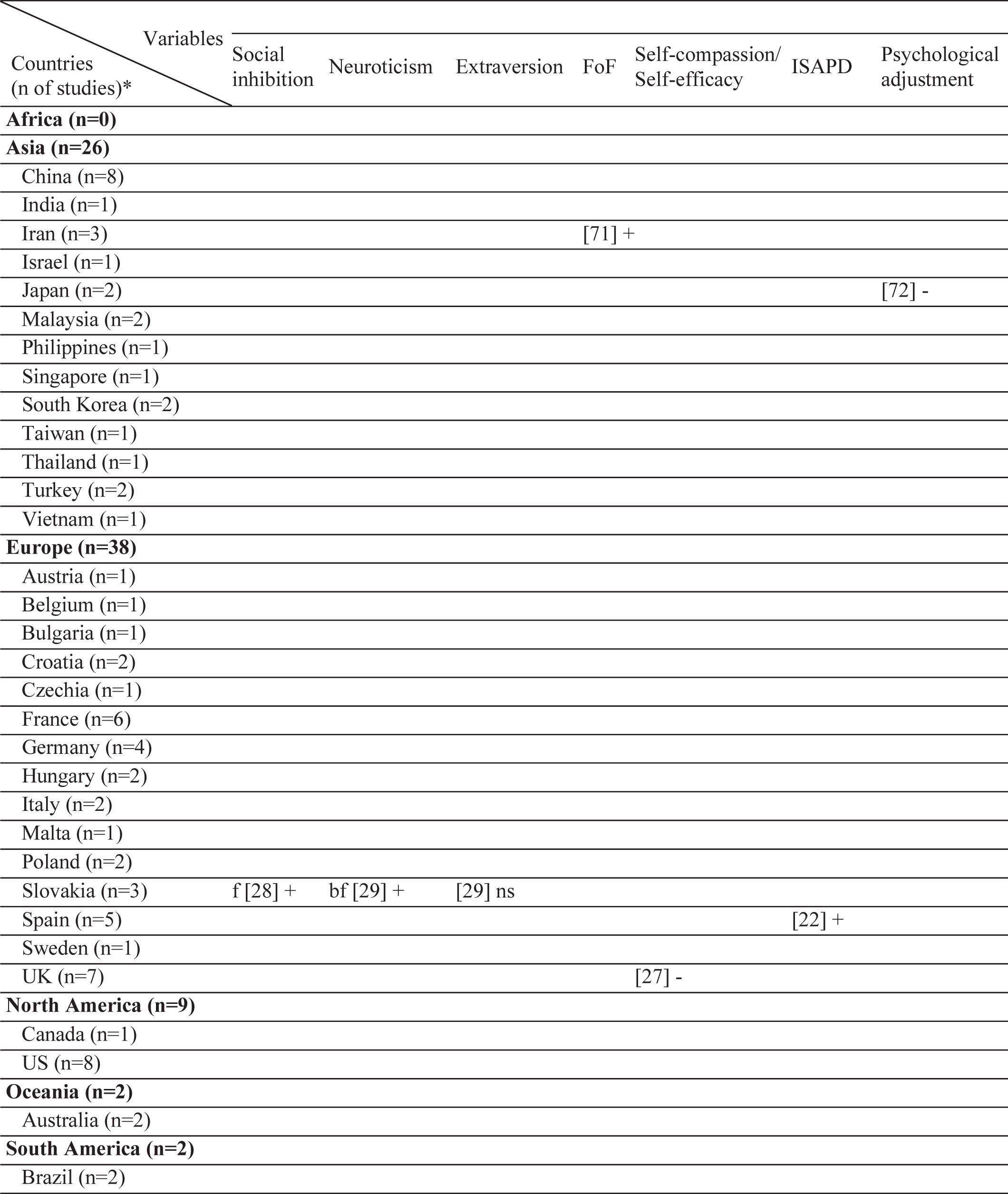

Results of this systematic review includes the currently analyzed Turkish data as well. The sample sizes of the included studies varied from 26 [20] to 866 [21]. Three different stigma scales were used [22–24]. In the literature, 61 different factors have been associated with stigma in PD (Table 2). Among those, the most frequently investigated factors were disease duration, sex, and age. The factors most frequently associated with stigma were disease duration, UPDRS-III, and IV/dyskinesia scores. In contrast, an inverse relationship has been frequently reported for age, subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS), and anti-Parkinson medications. The most frequent nonsignificant factor was sex, which was not associated with stigma in 10 of the 12 studies (Table 3). The study characteristics, assessment tools, and findings of all included studies are summarized in the Supplementary Material.

Table 2

Geographical distribution of the included studies and investigated factors regarding their associations with stigma

|  |  |  |  |  |

ns, no significant association with stigma; -, negatively associated with stigma;+, positively associated with stigma; f (female), associated with stigma only in female patients; m (male), associated with stigma only in male patients; bm (both, male), associated with stigma in total sample and in male patients but not in female patients; bf (both, female), associated with stigma in total sample and in female patients but not in male patients; bmf (both, male, female), associated with stigma in total sample and in both male and female patients either evaluated separetly or together; FoG, Freezing of Gait; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale; LEDD, L-dopa equivalent daily dose; BH, Bushen Huoxue Granule; AD, Antidepressant; L/E/C, Carbidopa / Levodopa / Entacapone; Rop, Ropirinole; Ras, Rasagiline; DBS, Deep Brain Stimulation; STN-DBS, Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; QoL, Quality of Life; RLS, Restless Leg Syndrome; ISAPD, Intermediate Scale for Assessment of PD. *The table includes Turkish data presented in this study.

Table 3

The most frequently investigated factors and their associations with stigma

| Total n of studies* | Positive association n of studies | Negative association n of studies | No association n of studies | |

| Top reported factors | ||||

| Disease duration | 13 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| Sex | 12 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Age | 11 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| Top reported factors as positively associated with stigma | ||||

| Disease duration | 13 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| UPDRS Part III | 9 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| UPDRS Part IV | 7 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| Top reported factors as negatively associated with stigma | ||||

| DBS-STN | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Age | 11 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| Medications | 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Top reported non-significant factors | ||||

| Sex | 12 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

| Disease duration | 13 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| Disease stage/severity | 8 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

UPDRS, Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale; DBS-STN, deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. *The table includes Turkish data presented in this study.

Risk of bias in selected studies

The results of the assessments for potential bias in the included studies are presented in the supplement (Supplementary Table 2). Three studies, written in languages other than English were evaluated based on their abstracts. Of the included 57 studies, only seven reported stigma in PD as the main objective. Forty-four studies investigated stigma in the context of QoL. Six studies had other objectives but included data on stigma in PD. Twenty studies were interventional with specific inclusion criteria but also included data on stigma. Details regarding the risk of bias are summarized in the Supplementary Material.

Association of stigma with demographic factors

Of the included studies, the association between age and stigma was either non-significant or negative, with no studies reporting increased stigma with aging. Four of the five (80%) studies from Europe and one in three (33%) studies from Asia reported a negative effect with age. Sex was also not associated with stigma globally, with the exception of two studies from China, which showed a positive association with female sex. Ethnicity was also not significantly related to stigma in most studies. In only one multicenter study, French patients reported more stigma than German patients did. The effect of some demographic factors on stigma, such as education, marriage, and employment has been investigated only in Asia. Rural living was associated with stigma in two East European countries (Croatia and Bulgaria), but not in China. Similar to age, the age of onset/diagnosis were either not associated or negatively associated with stigma. A positive association with disease duration was reported in Europe and Asia, whereas two studies from America (USA and Brazil) found no such association. The presence of comorbidities was positively related to stigma in only one study that included young-onset PwP.

Association of stigma with motor symptoms

Interestingly, the motor subtype of PD has rarely been investigated in relation to the stigma. With regard to tremor dominant (TD) or postural instability gait difficulty (PIGD) subtypes, studies from the USA and Asia found no significant association with stigma. In contrast, our data showed a positive association with TD subtype in both sex. Additionally, for the UPDRS-II scores, two studies from the USA found discrepant findings, with no significant results from Asia except our results which showed a positive association in females. The association of UPDRS-III with stigma scores was positive in Europe (Spain and Croatia), non-significant in America (USA and Brazil), and discrepant in Asia. Motor fluctuations, dyskinesia, and UPDRS-IV scores were among the most studied factors. These studies were conducted in five European countries, all of which found a positive association. The findings from Asia were mixed, and no study from America was found. Drooling has only been investigated in Asia and a positive association with stigma has been reported.

Association of stigma with non-motor symptoms

In the literature, only two studies reported data on the UPDRS-I, one with a positive association and one with a non-significant association. Our data also showed no association. Interestingly, a German study reported a negative association with urinary dysfunction. Cognitive impairment was not related to stigma in our cohort and in two Asian studies, whereas three North American studies found a positive association. Similarly, anxiety was related to stigma in the UK and USA, but not in China and Turkey. With regard to depression, a positive association has been reported in most countries, except three studies from the USA, Brazil, and Turkey. Psychosis has been investigated only in Asia, with the majority of studies finding a positive association. On the contrary, apathy was investigated in only one Japanese study. In China, most studies found a positive relationship with stigma when non-motor symptoms were taken as a whole. Solitary symptoms, such as gastrointestinal problems or sexual dysfunction were investigated in only one study from Vietnam, which found no association.

Association of stigma with treatment

The effects of treatment have frequently been investigated. However, no study on selegiline, rasagiline, pramipexole, or rotigotine was selected in this review. In European studies, treatment with ropinirole resulted in a decrease in stigma. In line with this, treatment with levodopa improved thoughts of stigma in PwP. With regard to DBS, all the studies showed a negative association. The majority of the ablative surgeries have also reported a negative association. Of note, no study from Asia has covered the effect of DBS or ablative surgery on stigma. Also, no study matched the criteria of this review that subjected stigma directly with continuous apomorphine or levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) therapy. Two reports on physiotherapy showed a negative association with stigma.

DISCUSSION

In this review, we collected studies reporting stigma in PwP to identify the factors associated with stigma in PD. We also explored potential differences in the perception of stigmatization, which could be attributed to the specific culture of PwP. Our results show a considerably imbalanced representation of populations worldwide. The results also indicate that some factors affecting stigma may differ depending on culture. In this study, we also report data from Turkey, which is a relatively underrepresented region in studies on stigma in PD.

In some subfields of PD-related research, achieving data diversity is a huge unmet challenge that compromises the credibility of the reached conclusions, recognition of region-specific needs, and generalization of the existing knowledge derived from PwP. The area of PD genetics is one example in which the lack of diversity has been underlined as “unacceptable” [73]. Likewise, one finding of this review is the striking inequality in regional representation, especially for Africa. We found no study from Africa (matching the inclusion criteria) which is the second most populated continent in the world. This indicates an urgent need for studies revealing the perception of the stigmatization of African PwP in their social structure. The results showed that South America is an underrepresented region. We included two studies from South America, both of which were from Brazil. It should also be noted that nearly half of the studies on stigma have been conducted in Europe, which constitutes only approximately 10% of the world’s entire population. More studies are needed to fully understand the stigma-related difficulties of PwP in Africa and South America.

In the literature, a wide array of factors has been investigated for their potential association with stigma in PD (Table 2). Among these, the most frequently investigated factors can be summarized as follows: 1) demographics (age, sex, and disease duration), 2) treatment effects (medical and surgical), and 3) motor assessments (motor impairment, fluctuations, or dyskinesia) (Table 3). Except for two studies that reported a non-significant change (with pallidotomy and antidepressants), all studies reported a decrease in stigma with symptomatic treatment, independent of the treatment type. With regard to demographics, age seemed to be more negatively associated with stigma in Europe compared to Asia. A plurality of studies found no significant association with sex. In addition, seven studies in the literature reported a non-significant association between disease duration and stigma compared to five, which found a positive association. Data from our cohort also showed a positive association in females. Results of the studies which found no association with disease duration may indicate the success of the symptomatic treatments in PD, allowing PwP to not feel stigmatized within society despite years of PD. Another reason for the lack of such association may be the acceptance of having PD in time or may be due to the fact that the feelings of stigmatization in PwP begin at the very early stages remaining unchanged throughout the disease course. Having said that, motor complications have been found to be increasingly related to stigma, underpinning the importance of successful treatment when complications occur. One interesting finding of this review is the relative scarcity of studies investigating the effects of tremor or a TD subtype. Resting tremor is a hallmark of PD that may cause a feeling of stigmatization among PwP. However, this was not the case in the three studies that found no association with motor subtype in contrast to our cohort of Turkish PwP.

One of the objectives of this review was to explore the culture-specific influences on the stigmatization of PwP. Of course, the outcomes of this objective are somewhat indirect, as there is no head-to-head comparison between cultures, with the exception of a European study in which the French felt more stigmatized than the German PwP [16]. With regard to the association of specific factors with stigma, sex could be a factor that may be confounded by culture. Female sex was found to be associated with stigma only in China (two of three studies), whereas no other study in Asia, including one Vietnam and Singapore study, found such a result. It is also worth noting that education, marital status, and employment were studied in only Asia, possibly pointing to the cultural implications of these factors in Asian societies. Similarly, effects of psychosis and drooling have only been studied in Asia. Anxiety was also non-significant two studies (our cohort and China), whereas two studies from the USA and the UK found an association. Additionally, there seems to be a culture-specific effect on cognition. Cognitive impairment was not found to be associated with stigma in Asian studies; however, two studies from the USA and Canada found more stigma feelings with worse cognition. On the other hand, it can be said that cultural differences do not play a role as the effect of age, depression, and medical treatment on stigma seems to be universal in the literature.

A literature search showed that Turkey is also an underrepresented population, with only one previous study matching the criteria [66]. Our analysis of data from 232 Turkish PwP showed that age was negatively associated with stigma in Turkish PwP, similar to most European studies. Moreover, having a TD subtype was associated with an increased likelihood of feelings of stigma, which was in contrast to previous studies, which are few, as discussed above. Apart from that, motor complications (assessed with the MDS-UPDRS-IV) were related to stigma in men, whereas disease duration, MDS-UPDRS-II, and waist circumference were associated with stigma in female Turkish PwP.

The limitations of this review should be noted. First, the extent to which the included studies represented the population they were conducted is questionable. Of the 57 included studies, 23 (40%) had a sample size of less than 100 PwP. Moreover, 15 countries were represented by only one study, which may hinder conclusive comments on stigma in PwP in that culture. In this regard, the most reliable inferences can be made for China, France, Germany, Spain, the UK, and the USA, which were represented by at least four studies (Fig. 2). Another limitation may be the tools used to assess stigma. In most studies, stigma was investigated using sub-questions from a QoL questionnaire, rather than tools that focused solely on stigma. Related to this, interventional studies had specific inclusion criteria that introduced potential bias in patient selection while investigating stigma. Third, our review was performed only in the PubMed/Medline electronic database; thus, studies in other databases may have been missed. Finally, in the PubMed/Medline electronic database, the search terms we used were scanned only in the title and abstract of the studies, which may have rendered some studies missing that mentioned the search terms not in the title or abstract but in the manuscript. Apart from that, the meticulous review process followed according to the PRISMA guidelines with two independent reviews is a clear strength of this review. Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first review to consider culture-specific effects that may play a role in stigma by exploring the potential differences in countries across the world.

In conclusion, in this review, we identified a large spectrum of factors that are universally associated with stigma in PwP, factors with discrepancies regarding their association with stigma in PD, and factors that may be related to stigma in PD depending on the specific culture of PwP. As in most areas of PD research, the available data are geographically biased. This creates a large unmet need for data diversity and hinders understanding and taking action against the culture-specific challenges of PwP in the era of precision medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Gülnur Ayık and Dudu Genç Batmaz for their support in collection of the local data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JPD-230050.

REFERENCES

[1] | Shulman LM ((2010) ) Understanding disability in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 25 Suppl 1: , 25 S131–S135. |

[2] | Stührenberg M , Berghäuser CS , van Munster M , Pedrosa Carrasco AJ , Pedrosa DJ ((2022) ) Measuring quality of life in Parkinson’s disease-a call to rethink conceptualizations and assessments. J Pers Med 12: , 804. |

[3] | Bloem BR , Henderson EJ , Dorsey ER , Okun MS , Okubadejo N , Chan P , Andrejack J , Darweesh SKL , Munneke M ((2020) ) Integrated andpatient-centred management of Parkinson’s disease: A network modelfor reshaping chronic neurological care. Lancet Neurol 19: , 623–634. |

[4] | Fabbri M , Caldas AC , Ramos JB , Sanchez-Ferro Á , Antonini A , Ržička E , Lynch T , Rascol O , Grimes D , Eggers C , Mestre TA , Ferreira JJ ((2020) ) Moving towards home-basedcommunity-centred integrated care in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 78: , 21–26. |

[5] | Gray R , Ives N , Rick C , Patel S , Gray A , Jenkinson C , McIntosh E , Wheatley K , Williams A , Clarke CE , et al. ((2014) ) Long-term effectiveness of dopamine agonists and monoamine oxidase B inhibitors compared with levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson’s disease (PD MED): A large, open-label, pragmatic randomised trial. Lancet 384: , 1196–1205. |

[6] | Drapier S , Eusebio A , Degos B , Vérin M , Durif F , Azulay JP , Viallet F , Rouaud T , Moreau C , Defebvre L , Fraix V , Tranchant C , Andre K , Courbon CB , Roze E , Devos D ((2016) ) Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease improved by apomorphine pump: The OPTIPUMP cohort study. J Neurol 263: , 1111–1119. |

[7] | Antonini A , Mancini F , Canesi M , Zangaglia R , Isaias IU , Manfredi L , Pacchetti C , Zibetti M , Natuzzi F , Lopiano L , Nappi G , Pezzoli G ((2008) ) Duodenal levodopa infusion improves quality of life in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegener Dis 5: , 244–246. |

[8] | Deuschl G , Schade-Brittinger C , Krack P , Volkmann J , Schäfer H , Bötzel K , Daniels C , Deutschländer A , Dillmann U , Eisner W , Gruber D , Hamel W , Herzog J , Hilker R , Klebe S , Kloß M , Koy J , Krause M , Kupsch A , Lorenz D , Lorenzl S , Mehdorn HM , Moringlane JR , Oertel W , Pinsker MO , Reichmann H , Reuß A , Schneider G-H , Schnitzler A , Steude U , Sturm V , Timmermann L , Tronnier V , Trottenberg T , Wojtecki L , Wolf E , Poewe W , Voges J ((2006) ) A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 355: , 896–908. |

[9] | Martinez-Martin P ((2017) ) What is quality of life and how do we measure it? Relevance to Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Mov Disord 32: , 382–392. |

[10] | Goffman E (1963) Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. |

[11] | Link BG , Phelan JC ((2003) ) Conceptualizing stigma. Ann Rev Sociol 27: , 363–385. |

[12] | Lin J , Ou R , Wei Q , Cao B , Li C , Hou Y , Zhang L , Liu K , Shang H ((2022) ) Self-stigma in Parkinson’s disease: A 3-year prospective cohort study. Front Aging Neurosci 14: , 790897. |

[13] | Zhu B , Kohn R , Patel A , Koo BB , Louis ED , De Figueiredo JM ((2021) ) Demoralization and quality of life of patients with Parkinson disease. Psychother Psychosom 90: , 415–421. |

[14] | Schomerus G , Evans-Lacko S , Rüsch N , Mojtabai R , Angermeyer MC , Thornicroft G ((2015) ) Collective levels of stigma and national suicide rates in 25 European countries. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 24: , 166–171. |

[15] | Koerts J , König M , Tucha L , Tucha O ((2016) ) Working capacity of patients with Parkinson’s disease - A systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 27: , 9–24. |

[16] | Hechtner MC , Vogt T , Zöllner Y , Schröder S , Sauer JB , Binder H , Singer S , Mikolajczyk R ((2014) ) Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients with motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in five European countries. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20: , 969–974. |

[17] | Page MJ , McKenzie JE , Bossuyt PM , Boutron I , Hoffmann TC , Mulrow CD , Shamseer L , Tetzlaff JM , Akl EA , Brennan SE , Chou R , Glanville J , Grimshaw JM , Hróbjartsson A , Lalu MM , Li T , Loder EW , Mayo-Wilson E , McDonald S , McGuinness LA , Stewart LA , Thomas J , Tricco AC , Welch VA , Whiting P , Moher D ((2021) ) The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: , n71. |

[18] | Peto V , Jenkinson C , Fitzpatrick R , Greenhall R ((1995) ) The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res 4: , 241–248. |

[19] | Harris PA , Taylor R , Thielke R , Payne J , Gonzalez N , Conde JG ((2009) ) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: , 377–381. |

[20] | Chircop C , Dingli N , Aquilina A , Zrinzo L , Aquilina J ((2018) ) MRI-verified “asleep” deep brain stimulation in Malta through cross border collaboration: Clinical outcome of the first five years. Br J Neurosurg 32: , 365–371. |

[21] | Hristova DR , Hristov JI , Mateva NG , Papathanasiou J V ((2009) ) Quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 51: , 58–64. |

[22] | Martínez-Martín P , Frades Payo B , FontánTirado C , Martínez Sarriés FJ , Guerrero MT , delSer Quijano T ((1997) ) [Assessing quality of life in Parkinson’sdisease using the PDQ-39. A pilot study]. Neurologia 12: , 56–60. |

[23] | Zhao YJ , Tan LCS , Lau PN , Au WL , Li SC , Luo N ((2008) ) Factors affecting health-related quality of life amongst Asian patients with Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol 15: , 737–742. |

[24] | Ma HI , Saint-Hilaire M , Thomas CA , Tickle-Degnen L ((2016) ) Stigma as a key determinant of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res 25: , 3037–3045. |

[25] | da Silva AG , Leal VP , da Silva PR , Freitas FC , Linhares MN , Walz R , Malloy-Diniz LF , Diaz AP , Palha AP ((2020) ) Difficulties in activities of daily living are associated with stigma in patients with Parkinson’s disease who are candidates for deep brain stimulation. Braz J Psychiatry 42: , 190–194. |

[26] | Salazar RD , Weizenbaum E , Ellis TD , Earhart GM , Ford MP , Dibble LE , Cronin-Golomb A ((2019) ) Predictors of self-perceived stigma in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 60: , 76–80. |

[27] | Eccles FJR , Sowter N , Spokes T , Zarotti N , Simpson J ((2023) ) Stigma, self-compassion, and psychological distress among people with Parkinson’s. Disabil Rehabil 45: , 425–433. |

[28] | Dubayova T , Nagyova I , Havlikova E , Rosenberger J , Gdovinova Z , Middel B , Van Dijk JP , Groothoff JW ((2009) ) The association of type D personality with quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Aging Ment Health 13: , 905–912. |

[29] | Dubayova T , Nagyova I , Havlikova E , Rosenberger J , Gdovinova Z , Middel B , Van Dijk JP , Groothoff JW ((2009) ) Neuroticism and extraversion in association with quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res 18: , 33–42. |

[30] | Chapuis S , Ouchchane L , Metz O , Gerbaud L , Durif F ((2005) ) Impact of the motor complications of Parkinson’s disease on the quality of life. Mov Disord 20: , 224–230. |

[31] | Tomic S , Rajkovaca I , Pekic V , Salha T , Misevic S ((2017) ) Impact of autonomic dysfunctions on the quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients. Acta Neurol Belg 117: , 207–211. |

[32] | Wu Y , Guo XY , Wei QQ , Song W , Chen K , Cao B , Ou RW , Zhao B , Shang HF ((2014) ) Determinants of the quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: Results of a cohort study from Southwest China. J Neurol Sci 340: , 144–149. |

[33] | Hariz GM , Limousin P , Zrinzo L , Tripoliti E , Aviles-Olmos I , Jahanshahi M , Hamberg K , Foltynie T ((2013) ) Gender differences in quality of life following subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand 128: , 281–285. |

[34] | Tran TN , Ha UN Le , Nguyen TM , Nguyen TD , Vo KNC , Dang TH , Trinh PMP , Truong D ((2021) ) The effect of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life in patients with young onset Parkinson’s disease: A single center Vietnamese cross-sectional study. Clin Park Relat Disord 5: , 100118. |

[35] | Meng D , Jin Z , Gao L , Wang Y , Wang R , Fang J , Qi L , Su Y , Liu A , Fang B ((2022) ) The quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease: Focus on gender difference. Brain Behav 12: , e2517. |

[36] | Schrag A , Hovris A , Morley D , Quinn N , Jahanshahi M ((2003) ) Young- versus older-onset Parkinson’s disease: Impact of disease and psychosocial consequences. Mov Disord 18: , 1250–1256. |

[37] | Hou M , Mao X , Hou X , Li K ((2021) ) Stigma and associated correlates of elderly patients with Parkinson’s disease. Front Psychiatry 12: , 708960. |

[38] | Islam SS , Neargarder S , Kinger SB , Fox-Fuller JT , Salazar RD , Cronin-Golomb A ((2022) ) Perceived stigma and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease with additional health conditions. Gen Psychiatry 35: , e100653. |

[39] | Klepac N , Pikija S , Kraljić T , Relja M , Trkulja V , Juren S , Pavlicek I , Babić T ((2007) ) Association of rural life settingand poorer quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients: Across-sectional study in Croatia. Eur J Neurol 14: , 194–198. |

[40] | Rajiah K , Maharajan MK , Yeen SJ , Lew S ((2017) ) Quality of life and caregivers’ burden of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroepidemiology 48: , 131–137. |

[41] | Moore O , Peretz C , Giladi N ((2007) ) Freezing of gait affects quality of life of peoples with Parkinson’s disease beyond its relationships with mobility and gait. Mov Disord 22: , 2192–2195. |

[42] | Cano-De-La-Cuerda R , Vela-Desojo L , Miangolarra-Page JC , Macías-Macías Y ((2014) ) Isokinetic dynamometry as atechnologic assessment tool for trunk rigidity in Parkinson’sdisease patients. Neurorehabilitation 35: , 493–501. |

[43] | Moreira RC , Zonta MB , De Araújo APS , Israel VL , Teive HAG ((2017) ) Quality of life in parkinson’s disease patients: Progression markersof mild to moderate stages. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 75: , 497–502. |

[44] | Ou R , Guo X , Wei Q , Cao B , Yang J , Song W , Shao N , Zhao B , Chen X , Shang H ((2015) ) Prevalence and clinical correlates of drooling in Parkinson disease: A study on 518 Chinese patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 21: , 211–215. |

[45] | Lyons KE , Pahwa R ((2005) ) Long-term benefits in quality of life provided by bilateral subthalamic stimulation in patients with Parkinson disease. J Neurosurg 103: , 252–255. |

[46] | Tkaczynska Z , Becker S , Maetzler W , Timmers M , Van Nueten L , Sulzer P , Salvadore G , Schäffer E , Brockmann K , Streffer J , Berg D , Liepelt-Scarfone I ((2020) ) Executive function is related to the urinary urgency in non-demented patients with Parkinson’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 12: , 55. |

[47] | Reginold W , Duff-Canning S , Meaney C , Armstrong MJ , Fox S , Rothberg B , Zadikoff C , Kennedy N , Gill D , Eslinger P , Marshall F , Mapstone M , Chou KL , Persad C , Litvan I , Mast B , Tang-Wai D , Lang AE , Marras C ((2013) ) Impact of mild cognitive impairment on health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 36: , 67–75. |

[48] | Oguru M , Tachibana H , Toda K , Okuda B , Oka N ((2010) ) Apathy and depression in Parkinson disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 23: , 35–41. |

[49] | Bansal N , Paul B , Paul G , Singh G ((2022) ) Gender differences and impact of autonomic disturbance on fatigue and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Neurol India 70: , 203–208. |

[50] | Dong H , Liu C , Hu X ((2014) ) [Effects of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 94: , 813–815. |

[51] | Song W , Guo X , Chen K , Chen X , Cao B , Wei Q , Huang R , Zhao B , Wu Y , Shang HF ((2014) ) The impact of non-motor symptoms on the health-related quality of life of Parkinson’s disease patients from Southwest China. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20: , 149–152. |

[52] | Fung VSC , Herawati L , Wan Y , Boyle R , Hughes A , Lueck C , Silburn P , Snow B , Stell R , Temlett J ((2009) ) Quality of life in early Parkinson’s disease treated with levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone. Mov Disord 24: , 25–31. |

[53] | Pahwa R , Stacy MA , Factor SA , Lyons KE , Stocchi F , Hersh BP , Elmer LW , Truong DD , Earl NL ((2007) ) Ropinirole 24-hour prolonged release:Randomized, controlled study in advanced Parkinson disease. Neurology 68: , 1108–1115. |

[54] | Cibulcik F , Benetin J , Kurca E , Grofik M , Dvorak M , Richter D , Donath V , Kothaj J , Minar M , Valkovic P ((2016) ) Effects of rasagiline on freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease - An open-label, multicenter study. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 160: , 549–552. |

[55] | Li M , Yang HM , Luo DX , Chen JZ , Shi HJ ((2016) ) Multi-dimensional analysis on Parkinson’s disease questionnaire-39 in Parkinson’s patients treated with Bushen Huoxue Granule: A multicenter, randomized, double-blinded and placebo controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 29: , 116–120. |

[56] | Zahodne LB , Okun MS , Foote KD , Fernandez HH , Rodriguez RL , Wu SS , Kirsch-Darrow L , Jacobson IV CE , Rosado C , Bowers D ((2009) ) Greater improvement in quality of life following unilateral deep brain stimulation surgery in the globus pallidus as compared to the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurol 256: , 1321–1329. |

[57] | Dafsari HS , Reker P , Stalinski L , Silverdale M , Rizos A , Ashkan K , Barbe MT , Fink GR , Evans J , Steffen J , Samuel M , Dembek TA , Visser-Vandewalle V , Antonini A , Ray-Chaudhuri K , Martinez-Martin P , Timmermann L , EUROPAR and the IPMDS (International Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Society) Non-Motor Parkinson’s Disease Study Group ((2018) ) Quality of life outcome after subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease depends on age. Mov Disord 33: , 99–107. |

[58] | Lezcano E , Gómez-Esteban JC , Tijero B , Bilbao G , Lambarri I , Rodriguez O , Villoria R , Dolado A , Berganzo K , Molano A , de Gopegui ER , Pomposo I , Gabilondo I , Zarranz JJ ((2016) ) Long-term impact on quality of life of subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 263: , 895–905. |

[59] | Derost P-P , Ouchchane L , Morand D , Ulla M , Llorca P-M , Barget M , Debilly B , Lemaire J-J , Durif F ((2007) ) Is DBS-STN appropriate to treat severe Parkinson disease in an elderly population? Neurology 68: , 1345–1355. |

[60] | Drapier S , Raoul S , Drapier D , Leray E , Lallement F , Rivier I , Sauleau P , Lajat Y , Edan G , Vérin M ((2005) ) Only physical aspects of quality of life are significantly improved by bilateral subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 252: , 583–588. |

[61] | Gray A , McNamara I , Aziz T , Gregory R , Bain P , Wilson J , Scott R ((2002) ) Quality of life outcomes following surgical treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 17: , 68–75. |

[62] | Sobstyl M , Zabek M , Koziara H , Kadziołka B ((2003) ) [Evaluation ofquality of life in Parkinson disease treatment]. Neurol Neurochir Pol 37 Suppl 5: , 221–30. |

[63] | Valálik I , Sági S , Solymosi D , Julow J ((2001) ) CT-guided unilateral thalamotomy with macroelectrode mapping for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 143: , 1019–1030. |

[64] | Ory Magne F , Fabre N , Gu C , Pastorelli C , Tardez S , Marchat JC , Marque P , Brefel Courbon C ((2014) ) An individual rehabilitation program: Evaluation by Parkinsonian patients and their physiotherapists. Rev Neurol (Paris) 170: , 680–684. |

[65] | Lee JH , Choi MK , Yoo Y , Ahn S , Jeon JY , Kim JY , Byun JY ((2019) ) Impacts of an exercise program and motivational telephone counseling on health-related quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease. Rehabil Nurs 44: , 161–170. |

[66] | Ongun N ((2018) ) Does nutritional status affect Parkinson’s disease features and quality of life? PLoS One 13: , e0205100. |

[67] | Fereshtehnejad SM , Ghazi L , Shafieesabet M , Shahidi GA , Delbari A , Lökk J ((2014) ) Motor, psychiatric and fatigue features associated with nutritional status and its effects on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS One 9: , e91153. |

[68] | Irons JY , Hancox G , Vella-Burrows T , Han E-Y , Chong H-J , Sheffield D , Stewart DE ((2021) ) Group singing improves quality of life for people with Parkinson’s: An international study. Aging Ment Health 25: , 650–656. |

[69] | Fereshtehnejad SM , Shafieesabet M , Shahidi GA , Delbari A , Lökk J ((2015) ) Restless legs syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A comparative study on prevalence, clinical characteristics, quality of life and nutritional status. Acta Neurol Scand 131: , 211–218. |

[70] | Hashim H , Azmin S , Razlan H , Yahya NW , Tan HJ , Manaf MRA , Ibrahim NM ((2014) ) Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection improves levodopa action, clinical symptoms and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 9: , e112330. |

[71] | Mehdizadeh M , Lajevardi L , Habibi SAH , ArabBaniasad M , Baghoori D , Daneshjoo F , Taghizadeh G ((2016) ) The association between fear of falling and quality of life for balance impairments based on hip and ankle strategies in the drug On- and Off-phase of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’ disease. Med J Islam Repub Iran 30: , 453. |

[72] | Suzukamo Y , Ohbu S , Kondo T , Kohmoto J , Fukuhara S ((2006) ) Psychological adjustment has a greater effect on health-related quality of life than on severity of disease in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 21: , 761–766. |

[73] | Schumacher-Schuh AF , Bieger A , Okunoye O , Mok KY , Lim SY , Bardien S , Ahmad-Annuar A , Santos-Lobato BL , Strelow MZ , Salama M , Rao SC , Zewde YZ , Dindayal S , Azar J , Prashanth LK , Rajan R , Noyce AJ , Okubadejo N , Rizig M , Lesage S , Mata IF ((2022) ) Underrepresented populations in Parkinson’s genetics research: Current landscape and future directions. Mov Disord 37: , 1593–1604. |