Barriers to Accessing Healthcare Services for People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease is a complex condition that affects many different aspects of a person’s health. Because of its complexity, people with Parkinson’s disease require access to a variety of healthcare services. The aim of the present study was to identify the barriers to access healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s disease. We conducted a scoping review according to guidelines posed by Arksey & O’Malley (2005). A search of MEDLINE, Embase, CINHAL, and PsycINFO databases was conducted, and 38 articles were selected based on the inclusion criteria. The review findings identified person-level and system-level barriers. The person-level barriers included skills required to seek healthcare services, ability to engage in healthcare and cost for services. The system-level barriers included the availability of appropriate healthcare resources. Based on the existing barriers elucidated in the scope review, we have discussed potential areas in healthcare that require improvement for people with Parkinson’s disease to manage their healthcare needs more equitably.

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurological disease that causes a substantial disease burden among elderly populations [1, 2]. The complex nature of the disease manifests as both motor and non-motor symptoms, and as a result, the affected persons need diverse healthcare services that range from pharmacological management and rehabilitation services to palliative care [3]. Studies have reported that people with Parkinson’s disease utilize more healthcare services such as overnight hospitalizations, appointments with physicians and medical specialists, and emergency admissions, beyond the frequency seen in the general Canadian population [4, 5]. The literature highlights that access to healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s disease is not always easy. Studies have reported that delays in diagnosis, a lack of appropriate healthcare services, especially in underservices regions, extensive waiting lists for specialist services, and the cost of care are some of the barriers to access healthcare services [6, 7].

There remain gaps in the knowledge and extent of the barriers blocking healthcare access for persons living with Parkinson’s disease. Previous review articles expressed that the barriers to access healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s disease are primarily derived from the care and service distribution and allotment [6, 7]. Care and service distribution are among other dimensions of healthcare barriers. As discussed by Levesque, Harris, & Russell (2013), five provider-related dimensions of access are pertinent; including approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness of healthcare services [8]. These dimensions interact with five corresponding patient-related dimensions, including the ability to perceive, ability to seek, ability to reach, ability to pay, and ability to engage in healthcare. The barriers to access healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s can arise from any of the dimensions alone, or in combination. However, the barriers for people with Parkinson’s disease from other relevant and less documented dimensions of access have not yet been explored through a rigorous literature review.

Since the body of literature was not well developed in this area, it was determined that a scoping review was the best approach. A comprehensive review of articles was undertaken, irrespective of study design for mapping the key research finding and gaps [9, 10]. The scoping review was intended to examine a broader area of knowledge, without eliminating studies on the basis of methodology [9, 10]. The objective of scoping review was mapping all reported barriers to access healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s disease. This mapping would help in identifying further potential dimensions of access that need to be addressed to ensure that healthcare services appropriately accessible for people with Parkinson’s disease. The overarching question of the review was, ‘what are the barriers that people with Parkinson’s disease face in accessing services? For the parameters of the current scoping review, we considered the access framework of Levesque et al. (2013) to categorically map the barriers [8].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The scoping review was conducted according to the guideline by Arksey & O’Malley (2005) [9]. The search strategy aimed to derive peer-reviewed articles from electronic bibliographic databases and reference lists of articles. The search was conducted with the consultation of a health science librarian at Bracken Health Science Library, Queens University. We searched four electronic databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINHAL, and PsycINFO.

Studies were included in the review regardless of geographical location or methodology. The inclusion criteria were:

• English language articles published between the date of inception of their respective databases and December 2020.

• Inclusion of people with Parkinson’s disease in the study.

• Using some or all the following keywords: Parkinson’s Disease, healthcare services, and access to healthcare. Detailed keyword search strategies are presented in Table 1.

• Review articles and empirical studies that conducted a primary or secondary analysis of data.

Table 1

List of keywords for database search

| Databases | Keywords |

| Medline | Parkinsonian Disorders or Parkinson and exp Health Services Accessibility/ or (“health care” adj3 access).mp. and exp patient compliance/or patient dropouts/ The search was limited to the English language. |

| Embase | Exp Parkinson disease/ or Parkinson*.mp. and (Barriers*adj3 care).mp. or exp patient compliance/ or HealthTT services accessibility.mp. |

| The search was limited to English language, articles, or conference abstract or conference paper or ‘conference review. | |

| PsycINFO | Parkinson’s disease/ or Parkinson*.mp and health care utilization/or (“health care” adj3 access*). mp. or Treatment barriers/ or treatment compliance/The search was limited to the English language. |

| CINAHL | (MH “Parkinson Disease’) or “Parkinson” and (MH ‘Health Services Accessibility+”) or ‘Barriers” or (MH ‘Patient Compliance+’) |

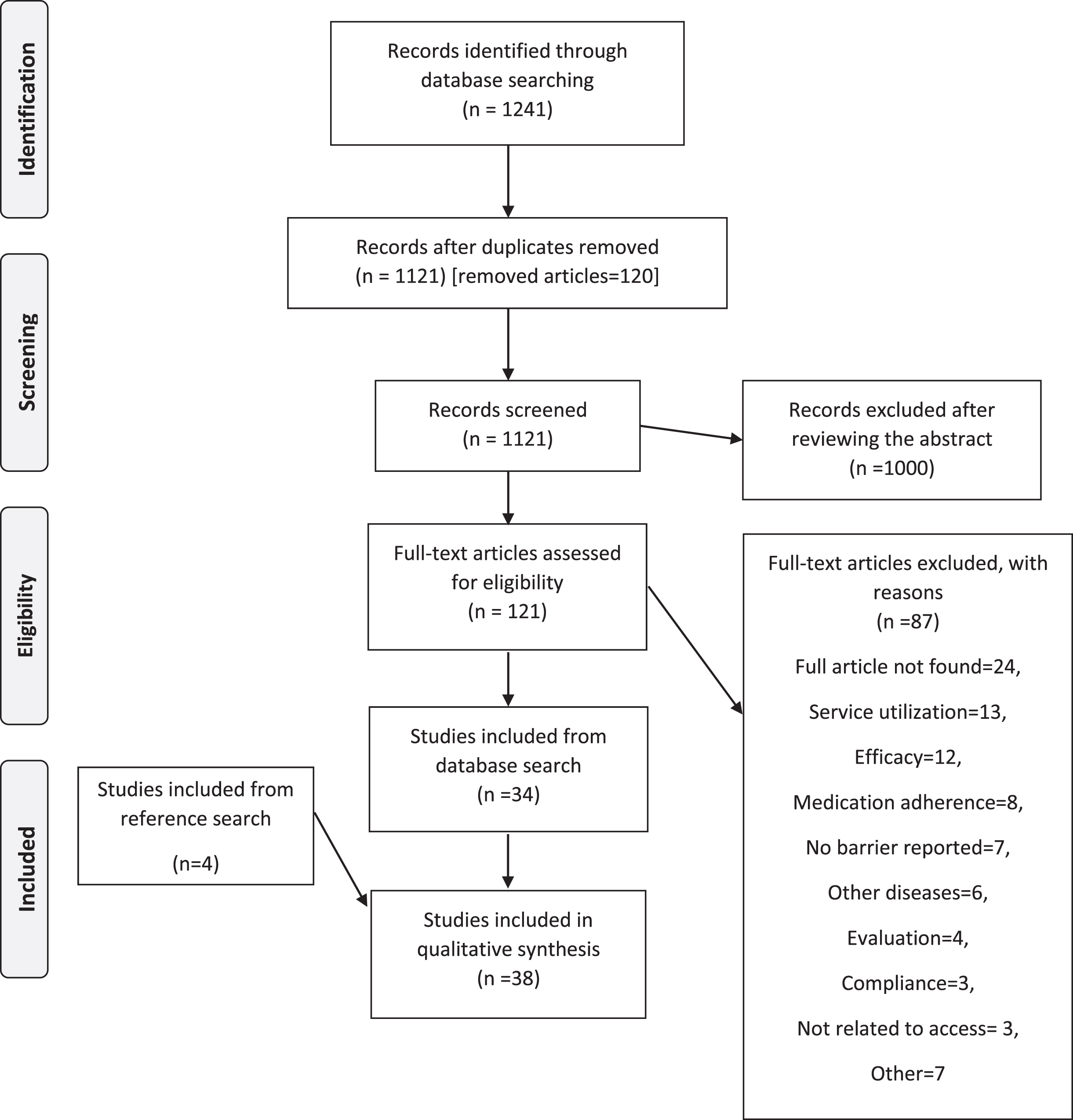

The database search yielded 1,121 articles after removing duplicates. Titles and abstracts of all these articles were screened for relevance. The screening was conducted independently by two reviewers. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer when necessary. Articles were excluded if they did not report data on people with Parkinson’s disease or address the primary research question. A total of 1, 000 articles were excluded, leaving 121 articles to be considered for full-text review. 24 of the 121 articles were excluded as their full text could not be retrieved. The remaining 97 articles were then considered for a full-text review. Of the remaining 97, 63 articles were excluded on the basis of poor-fit to the inclusion criteria and research question. Thus, 34 articles were selected to include in the presented scoping review. The excluded articles were related to adherence to medication (n = 9), compliance (n = 4), efficacy (n = 12), evaluation (n = 4), people with other health conditions (n = 6), healthcare utilization (n = 14), physical activity (2), and other (n = 7). An additional 4 articles were included after hand searching the reference lists of those 34 selected articles.

The final set for the scoping review consisted of 38 articles. The search results are summarized in the PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1. These 38 articles were published between 1997 and 2020 (Table 2), with the majority of articles (n = 27) published after 2010. Of the 38 articles, 19 articles stemmed from quantitative research. Most of the studies were conducted in North America (n = 20), and two were multi-centre international studies. Five studies included samples that included participants with other diseases including cardiovascular disease, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, Huntington’s disease, and epilepsy.

Fig. 1

Screening and selection of articles in PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2

Characteristics of the articles (total n = 38)

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

| Study design | |

| Quantitative study | 19 (50) |

| Cross-sectional survey | 12 (31.6) |

| Secondary data analysis | 6 (15.8) |

| Retrospective cohort | 1 (2.6) |

| Qualitative study | 11 (28.9) |

| Mixed method study | 1 (2.6) |

| Review study | 7 (18.4) |

| Country of origin | |

| USA | 17 (44.7) |

| UK | 9 (23.7) |

| Canada | 3 (7.9) |

| Other countries in Asia, Europe and Australia | 9 (23.7) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2010 and earlier | 11 (28.9) |

| 2011–2020 | 27 (71.1) |

| Type of sample involved in the study | |

| People with Parkinson’s disease | 33 (86.8) |

| People with Parkinson’s and other diseases | 5 (13.2) |

The ‘descriptive-analytical’ method was used for charting data from the selected articles [9]. A data extraction table (Microsoft Excel 2016 for Windows) was used for all selected articles that included information on year of publication, country of data collection, the objective of the study, study population, sample size, design of the study, the method of data collection, and barriers for accessing the healthcare services. The reviewers independently extracted data from the selected articles, then consulted with each other and finalized the data extraction table. A description of the 38 articles is presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Study designs, samples, and key findings of the reviewed articles

| Study | Research objectives | Research method | Sample | Key findings (barriers) in relation to the present review |

| [23] | To provide an overview of medication adherence issues in older adults with Parkinson’s disease | Review article | – | Prescriber-related factors including physician communication, and patient-related factors including co-morbidities, depression, cognitive ability, health belief, health literacy, race, income, type of insurance affected medication use |

| [31] | To identify the principal intervention needs of elderly couples living with moderate-stage Parkinson disease and their preferences regarding the modalities of a possible nursing intervention | Qualitative study | People with moderate-stage PD over the age of 65 years and their spousal care givers. | Lack of health literacy prevented access to resource for care |

| Poor communication caused difficulties in interaction with family, friends, and healthcare providers | ||||

| [36] | To examine deep brain stimulation (DBS) use in Parkinson’s disease and to determine which factors, among a variety of demographic, clinical, and socioeconomic variables, drives DBS use | Quantitative study conducted by secondary analysis of nation-wide data | 2408302 patients with Parkinson’s discharged from non-federal hospitals in the USA | African American status and use of Medicaid relative to Medicare and private insurance caused non-use of Deep Brain Stimulation |

| [38] | To determine the incidence of Parkinson’s disease and the effects of race/ethnicity, other demographic characteristics, geography, and healthcare utilization on probability of diagnosis | Quantitative study conducted by secondary analysis of state-wide data | 182271 Medicaid eligible adults ages 40 to 65 years who did not meet the study definition of Parkinson’s disease in the year before the start of the study. | African American people were less likely diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease |

| [39] | To identify racial disparities in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease | Quantitative study conducted by secondary analysis of state-wide data | 307 new cases of Parkinson’s disease from Medicaid claims | African American patients less likely received medication treatment and physical therapy |

| [42] | To compare access to caregiving between men and women with Parkinson disease | Cross sectional and longitudinal study | 7209 people with Parkinson’s disease | Females with Parkinson’s disease less likely had caregiver |

| [12] | To determine the self-perceived physical limitations and compensatory strategies of people living with Parkinson’s disease | Qualitative study with focus group discussion | 9 people with Parkinson’s disease | Lack of outreach or community program prevented reaching physical therapy services. |

| Exercise facilities did not accommodate the need of people with Parkinson’s | ||||

| Lack of institutional attention adversely influenced use of assistive device, Healthcare provider did not communicate well about the disease. | ||||

| [22] | To examine the pharmacological management of patient with Parkinson’s disease during surgical admissions | Quantitative study conducted by secondary analysis by hospital records | 68 patients with Parkinson’s disease with hospital admission under surgical specialties | Patients’ inability of swallowing, and out of stock caused missed or late doses of Parkinson’s medication during hospital admission |

| [15] | To identify and describe barriers to mental health care utilization for people with Parkinson’s disease | Quantitative cross-sectional study | 883 people with Parkinson’s disease | Struggling with situation, insensitivity of doctors to the mental health problems, out of pocket payment, not been referred, unavailability of services, not involved in decision making, transportation related problems caused inaccessibility to mental service |

| [16] | To determine the options of individuals with neurological conditions on factors facilitating their physical activity participation | Qualitative study with focus group discussion | 24 people with neurological condition including muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson’s disease | Inaccessibility of fitness facilities, cost of services, transportation problem, social embarrassment, perceived lack of condition-specific knowledge of the fitness professionals prevented participation in physical activity |

| [24] | To reveal significant relationships among Parkinson’s, depression, and medication adherence | Review article | – | Depression in people with Parkinson’s disease adversely affect use of medication |

| [11] | To know about the lived health-care experiences of persons living with palliative stage Parkinson’s disease and the family members who care for them | Qualitative study with phenomenological method and semi-structure in-depth interview | 7 participants including 3 people with Parkinson’s disease, and 4 family members | Healthcare provider did not provide sufficient information regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and homecare services |

| Poor health literacy and lack of power imbalance between doctors and patients prevented in getting health information. | ||||

| [44] | The study investigated the influence of lockdown during the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease | Survey | 113 people with Parkinson’s disease | Infection prevention and control measures prevented access to healthcare during COVID-19 pandemic situation |

| [43] | To describe Parkinson’s disease medication administration for a group of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who are admitted to a hospital, and to investigate medication administration schedule discrepancies during hospitalization | Quantitative study conducted by retrospective review of hospital data | 100 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who were hospitalized | Use of different specialist services (neurologist vs. non-neurologist) affected the administration of Parkinson’s disease medication differently during hospital admission |

| [27] | To explore overall and any symptom specific barriers to help-seeking for Non-motor symptoms | Cross sectional survey | 358 people with Parkinson’s disease | Acceptance of symptoms, lack of awareness about non-motor symptoms, health belief on efficacy of treatments, social embarrassment about sexual dysfunction prevented accessing care for non-motor symptoms |

| [35] | To explore barriers to help-seeking using two theoretical frameworks, the Common Sense Model of illness perception and Theoretical Domains Framework | Qualitative study with semi-structure interview | 20 people with Parkinson’s disease | Health belief about Parkinson’s related non-motor symptom, severity of symptoms, efficacy of treatment; social embarrassing; patient communication skills, healthcare professional’s communication skills and relation with patients, giving less importance to non-motor symptoms in consultation; problem with memory and concentration prevented access to healthcare for non-motor symptom |

| [17] | To systematically review the literature on clinical and demographic factors associated with medication non-adherence in Parkinson’s disease | Review article | – | Mood disorders, cognition, poor symptom control, polypharmacy, risk taking behavior, poor knowledge of Parkinson’s disease, low income, employment and gender identity affected use of medication adversely |

| [13] | To explore the perceptions of exercise and barriers that may affect participation in people with Parkinson’s disease | Qualitative study with focus group discussion and individual interview | 15 samples including 13 people with Parkinson’s disease, and 2 neurologists | Difficulties of diagnosis, lack of informational support provided by neurologist, lack of referral to physiotherapy services, disease specific issues, lack of time, lack of health system resources, and setting-related issues prevented participation in exercises |

| [28] | To elicit patient-reported needs and barriers to care and evaluate patient-reported quality of life (QOL), frequency of non-motor symptoms (NMS), and the impact of NMS on QOL | Quantitative cross-sectional study | 96 samples including 19 people with essential tremor and 77 people with Parkinson’s disease | Cost of care, non-coverage of cost by insurance, stigma, transportation problems, balancing family work, lack of support from family prevented use of care for non-motor symptoms |

| [26] | To examine health care professionals’ experiences of potential barriers and facilitators in providing palliative care for people with Parkinson’s disease in the Netherlands | Qualitative descriptive study With individual interview and focus group discussion | 29 people with Parkinson’s disease | Cognitive deficits, patients’ communication skills, limited resources, a lack of competences of healthcare professionals, and limited communication between health care professionals prevented use of palliative care |

| [29] | To evaluate and compare clinical management, utilization of health services and quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease attending clinics in urban and regional area | Quantitative cross-sectional study | 210 patients with Parkinson’s disease attending specialist neurological clinics in a regional area and an urban area | Patients residing in rural area had less frequency of health visits, experienced high rate of early misdiagnosis, and had relatively poor knowledge about the disease |

| [32] | To document the existence of reluctance to start medication as an issue for patients with Parkinson’s disease in four different countries, and to explore the reasons for this reluctance and to complement it with the physician perspective | Quantitative cross-sectional study | 201 people with Parkinson’s disease from three countries including Portugal, Germany, and Canada | Fear of side effects, non-acceptance of diagnosis, dislike for medications, skepticism regarding the efficacy of medication, and dislike for chronic medication caused reluctance for initiating start medication |

| [46] | To assess the self-reported health status, access to a variety of health and other services, and relationship between health status and access to services for individual with Parkinson’s disease | Quantitative survey | 178 people with Parkinson’s disease | There was lack of access to healthcare services including services of general practitioner, social services professionals, physiotherapist and assistive devices |

| [45] | This study aimed to explore the effects of prolongation of lockdown on patients with Parkinson’s disease by evaluating possible problems faced during a lockdown and worsening of symptoms if any | Quantitative cross sectional | 100 people with Parkinson’s disease and their caregiver | Prolong lockdown because of COVID-19 pandemic caused inaccessibility to healthcare facilities |

| [14] | To assess the clients’ views about independent exercise program, therapists’ view about prescribing such program, impact of disease-specific and non-disease specific issues on the design and implementation of exercise program and factors do therapists consider important when designing independent exercise program | Qualitative study with focus group discussion and individual interview | 18 samples including 8 physical therapist, 5 people with Huntington disease, and 5 people with Parkinson’s disease | Physical and cognitive impairment, lack of information on exercise, balance problems, home environment prevented participation in exercises |

| [30] | To summarize the evidence base for palliative care in Parkinson’s disease, linking current understanding with implications for clinical practice and identify areas for future research | Review article | – | Poor patient-healthcare provider communication hamper in the planning for palliative care |

| [18] | Identify key features of an enduring group exercise program for people with Parkinson’s disease by exploring experiences of participants, student assistants and the exercise instructor through a convergent mixed methods design | Convergent mixed-method design study: Qualitative study with interview and written reflection and quantitative study through administration of questionnaire | 14 people with Parkinson’s disease | Health related issues and transportation problem prevented participation in exercises |

| [19] | To reveal the unmet needs of nursing home residents with Parkinson’s disease | Qualitative study with focus group discussions and individual interviews | 30 samples including 15 people with Parkinson’s and 15 informal caregivers | Limited knowledge on the disease among healthcare professionals caused poor administration of Parkinson’s medication and no or poorly delivered emotional support Immobility prevented from paying regular visits for healthcare |

| [37] | To evaluate racial and ethnic differences in the utilization of neurologic care across a wide range of neurologic conditions | Quantitative study conducted by secondary analysis of nationwide data | 279,103 samples, of which 16,936 were self-reported neurologic patients including 3,338 with cardiovascular disease, 2,236 with epilepsy, 399 with multiple sclerosis, and 397 with Parkinson’s disease | Black, and Hispanic patients less likely visited outpatient neurologists |

| [41] | The goal of this pilot study was to determine whether there are gender discrepancies in diagnosis and time to present to a movement disorder specialist, and to assess whether clinical and referral factors account for these differences | Quantitative cross-sectional study | 109 people with Parkinson’s disease (53 women, 56 men) | Females took longer duration to see movement disorder specialists for the first time |

| [6] | To obtain an understanding of the access to care issues for patients with Parkinson’s disease across the United States and review past and current solutions to aid their provision of care | Review article | – | Cost of care, non-coverage of insurance services, unavailability of specialist services, stigma on having movement disorder, transportation problem, lack of coordination, lack of family support prevented accessing specialist services including services of neurologist, movement disorder specialist, and mental healthcare providers |

| [33] | To understand experiences of people with Parkinson’s disease to initiate medication therapy for Parkinson’s disease | Descriptive qualitative study with semi-structure interviews | 21 samples including 16 community dwelling individuals with Parkinson’s disease, and 5 family members | Trust in health care providers, and belief of treating Parkinson’s disease naturally affect acceptance and initiation of medication use |

| [20] | To describe challenges in adherence to medication regimens and to identify strategies used to facilitate adherence to medication regimens in people with Parkinson’s disease | An exploratory, descriptive qualitative research design with semi-structured interview | 16 people with Parkinson’s disease | Poor outcome of medication use, cost of medication, and forgetfulness prevented use of medication |

| [34] | To explore factors contributing to willingness to seek mental health treatment and to identify any significant barriers and /or facilitators of treatment-seeking behavior | Quantitative cross-sectional survey | 327 people with Parkinson’s disease | Dependency, efficacy, and side effect of treatment; stigma; and concern regarding doctor’s reaction prevented utilization of mental health care |

| [21] | To determine the demographic, social, and clinical aspects modifying therapy adherence in Parkinson’s disease | Quantitative cross-sectional study | 450 people with Parkinson’s disease | Knowledge about the disease, family support, income, cognitive status, and psychiatric pathology affected use of medication |

| [25] | To discuss societal and Parkinson-specific barriers that could impede implementation of patient-centered care to the management of Parkinson’s disease and other chronic conditions | Review article | – | Lack of guidelines for patient centered care, patients’ age and cognitive capacity, and reimbursement procedure for healthcare professionals prevented implementation of patient centered care |

| [40] | To investigate the utilization of neurologist providers in the treatment of patient with Parkinson’s disease and to determine whether neurologist treatment is associated with improved clinical outcome | Retrospective cohort study | 138000 incident Parkinson’s disease cases | Race and sex identity influenced accessing neurologist care |

| [7] | To review the most important current issues in the diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease | Review article | – | Failure to recognize symptoms and signs of early Parkinson’s disease, long waiting lists for new and follow-up appointment, starting treatment before the diagnosis is confirmed by a specialist, lack of information given to patient and carers, lack of psychological support, GPs unfamiliarity of new medication, and unavailability of rehabilitation specialist prevent access to healthcare |

RESULTS

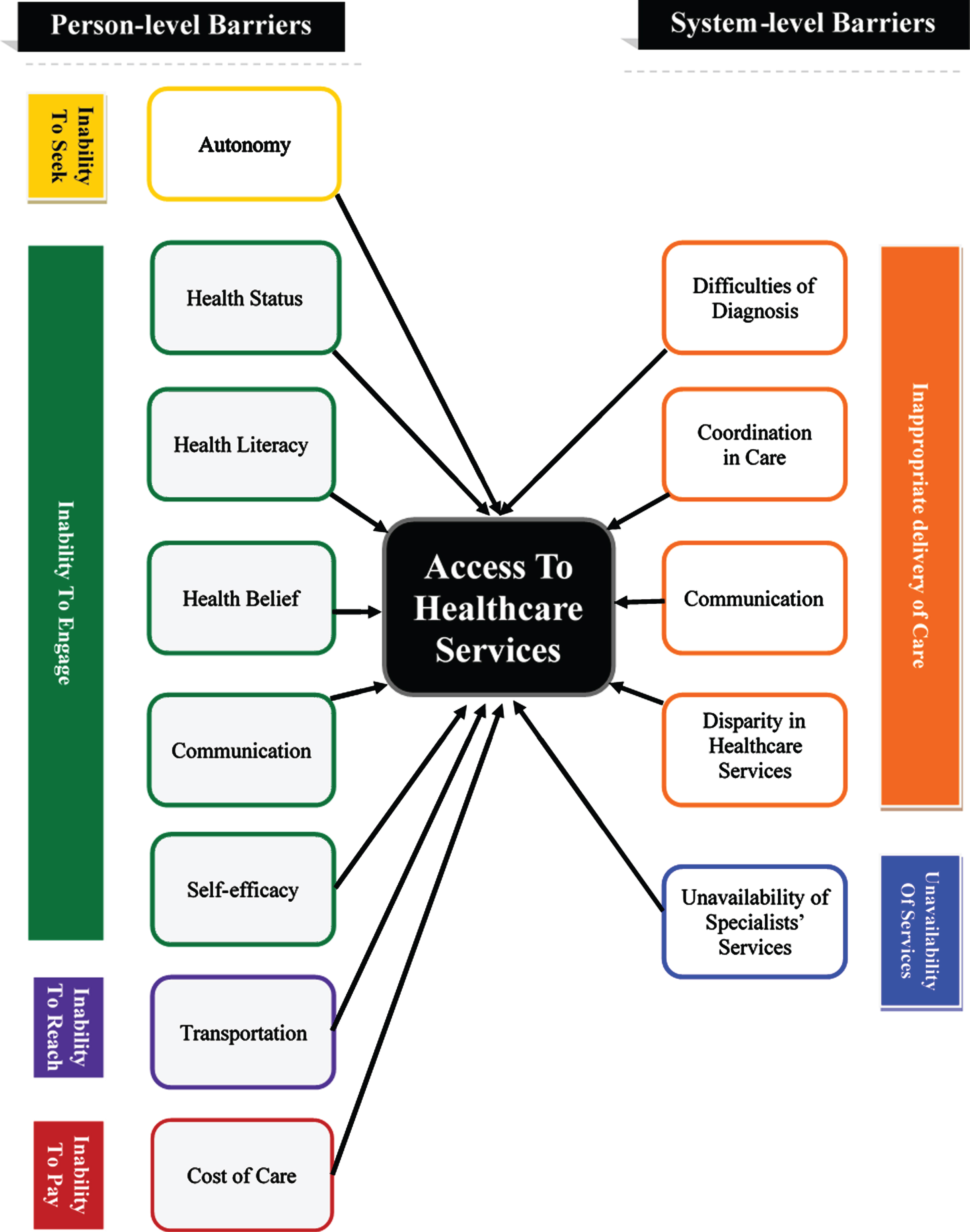

The results of the review showed that the barriers for accessing healthcare services occur at two levels (Fig. 2): Person-level barriers (reported by 27 papers) and system-level barriers (reported by 25 papers). Table 4 lists the barriers to healthcare services that were identified by the reviewed articles.

Fig. 2

Barriers to access healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s disease.

Table 4

Barriers to healthcare services reported in the studies

| Themes of barriers | Domains of access | Barriers | Number of studies | Studies |

| Person level barriers | Ability to seek healthcare services | Autonomy | 4 | [11–14] |

| Ability to engage in healthcare | Health status | 14 | [13, 14, 23–26, 15–22] | |

| Health literacy | 11 | [11–14, 17, 23, 27–30] | ||

| Health belief | 6 | [23, 27, 32–35] | ||

| Communication | 11 | [11, 12, 35, 13–15, 26–29, 31] | ||

| Self-efficacy | 4 | [11, 15, 16, 34] | ||

| Ability to reach healthcare services | Transportation | 4 | [15, 16, 18, 28] | |

| Ability to pay for healthcare services | Cost of care | 9 | [11, 15–17, 20, 23, 28, 36, 37] | |

| System level barriers | Appropriate delivery of healthcare services | Difficulties of diagnosis | 2 | [7, 13] |

| Coordination in care | 7 | [6, 7, 12, 13, 15, 25, 28] | ||

| Communication | 5 | [11–14,26] | ||

| Disparity in healthcare services | 9 | [28, 34, 36–42] | ||

| Availability of healthcare services | Unavailability of specialists’ services | 9 | [12, 15, 46, 16, 19, 22, 28, 29, 43–45] |

Person level barriers

At the person-level, people with Parkinson’s disease face barriers in most of the dimensions (4 out of 5) of access, previously mentioned under Background, as defined by Levesque et al., (2013) [8]. These barriers include their ability to seek healthcare services and engage in healthcare, transportation logistics, and cost of care. Details of these barriers are elaborated on below.

Skills to seek healthcare services

Four (4) articles showed the inability of people with Parkinson’s disease in seeking healthcare services, that included the concept of personal autonomy and capacity to seek care, as well as knowledge about healthcare options, better know as healthcare literacy. As described in the article by Giles & Miysaki (2009), many people with Parkinson’s disease are not adequately knowledgeable on the pertinent questions to address with their doctors, required to ensure sufficient health management [11]. Consequently, they end up with poor interactions with healthcare professionals (HCPs) during the healthcare visits, which negatively impacts their access to other related services such as homecare services [11]. Several other studies have also confirmed the noted trend of dependency on healthcare professional for health-related information or services amongst people with Parkinson’s disease [12–14]. The studies further reported that people with Parkinson’s disease assume that the HCPs are the only responsible persons for providing health information or taking healthcare decisions. As a result people with Parkinson’s disease depend on HCPS for prescribing physiotherapy or use of assistive devices [11–14]. A vast minority of people with Parkinson’s disease feel that they should be the ones to initiate healthcare discussion within the patient-provider relationship [12, 13]. The studies reported that very few people (n = 2 out of 22 participants between two qualitative studies) with Parkinson’s disease look for alternative sources of health information, in the absence of physician advice, including the internet and Parkinson’s disease support groups [12, 13].

Ability to engage in healthcare

Many of the reviewed studies (n = 25) reported a significantly reduced tendency for people with Parkinson’s disease to engage in healthcare services. The ability to engage in healthcare, within our context, specifically refers to the involvement of the patient in their treatment or healthcare-related decisions [8]. The ability to engage in healthcare services is influenced by an individual’s: (a) health status; typically, denoted by poor physical and mental health for our target demographic; (b) health literacy and health belief; (c) communication skills and self-efficacy; that is, the perceived confidence of engaging in healthcare.

(a) Health status. Poor health status, including the typically poor physical and mental health conditions of people with Parkinson’s disease negatively affects the utilization of various healthcare services, adherence to treatments and pharmacological regimens, and active involvement in patient-centered care. Several studies showed that health conditions including physical and balance impairments, cognitive problems, mood disorders and any concomitant pharmacological side-effects that can prevent people with Parkinson’s disease from participating in physical activities [13–21]. Similarly, Rumund et al. (2014) reported that people with Parkinson’s disease, who live in a nursing home, are less willing on average to visit neurologists regularly, because of their physical immobility [19]. Furthermore, studies have also shown that an inability to swallow (e.g. medication, food, etc.), forgetfulness, psychiatric or mood problems, or cognitive impairments prevent people with Parkinson’s disease from self-administering medication at the necessary intervals [17, 20–24]. Eijk, Nijhuis, Faber, & Bloem (2013) showed that age and cognitive capacity play a significant role in understanding medical information and making treatment decisions in patient-centered care [25]. Lennaerts et al. (2019) further expressed that a in late-stage Parkinson’s disease, persons’ needs and wishes can be hard to elicit due to cognitive decline. As a consequence, appropriate palliative care cannot be provided [26].

(b) Health literacy and health belief. Fourteen (14) of the 38 articles reviewed reported that health literacy and health belief of people with Parkinson’s disease affect their access to healthcare by interrupting their awareness and communicative abilities within their own healthcare. Reviewed articles from Australia, Canada, Jordan, the USA, and the UK have showed that the status of the health literacy of the people with Parkinson’s disease is not satisfactory as they have poor knowledge on the disease itself, let alone its consequences [11–14, 27–29]. Studies reported the observed proportion of the people with Parkinson’s disease who have a poor knowledge on the disease, ranges from 14.7 to 20%[28, 29]. Poor health literacy impacts the engagement of people with Parkinson’s disease in healthcare and ultimately affect the adherence of treatment. For example, Hurt et al. (2019) showed that those with lower health literacy are less likely to report non-motor based symptom to their healthcare professionals [27]. Davis et al. (2003) showed that people with Parkinson’s disease stop using their assistive devices as they do not have the necessary training or understanding for their proper use [12]. Similarly, some people with Parkinson’s disease do not actively engage themselves in physical activities and exercises as they have not received education on Parkinson’s disease-specific exercises that can accommodate their range of mobility [13, 14]. Richfield, Jones, & Alty (2013) showed that a lack of health literacy is ultimately a delimiting factor in planning for palliative care [30]. Beaudet & Ducharme (2013) showed that lack of knowledge also prevents people with Parkinson’s disease from accessing formal and informal support services in the community [31]. James, Kyaw, John, Helen, & Deane (2012) and Bainbridge et al. (2009) showed that poor knowledge, or health literacy, about the disease is a significant barrier to health management, associated (p = 0.04) with non-adherence of pharmacological regimens [17, 23].

The other barrier that influences the engagement of people with Parkinson’s disease in healthcare is beliefs about medication and disease. These were found to play a significant role in decision-making, especially about pharmacological approaches to treating Parkinson’s disease [23]. Concerns about real or perceived side effects, dislike for drug interventions, and general skepticism about drugs were cited as person-level barriers [32]. Trust of healthcare professionals however can overcome these problems and facilitate pharmacological therapy [33]. Preference for naturopathic remedies can also be a barrier to medication non-adherence [33]. In particular, mental health treatments may be avoided due to fears about dependency on medication [34] and tendencies to under-report non-motor symptoms or their severity [27, 34, 35].

(c) Communication skills and self-efficacy. Poor communication skills and self-efficacy prevents people with Parkinson’s disease from obtaining necessary health information, accessing mental health services, and participating in physical activities in public facilities. As an individual’s Parkinson’s condition progresses, their speech and communication skills are further afflicted. These communication problems affect their interactions with healthcare professionals. Following this observation in patients, studies have shown that a significant portion of people living with Parkinson’s disease may not achieve adequate health literacy, regarding their diagnosis, pharmacological and non-pharmacological symptom management, and assistive devices, as a result of these communication problems and poor self-efficacy [11–15, 28, 29, 31]. The result of these communication barriers is that people with Parkinson’s disease face difficulties in approaching healthcare providers to obtain health information, which is exacerbated by a perceived imbalance of power between HCPs and patients [11]. Furthermore, Dobkin et al. (2013) and Troeung et al. (2015) showed that poor communication and self-efficacy that limit expression of emotional or coping issues to healthcare providers, is a barrier for accessing mental health services. Elsworth et al. (2009) further supports this notion by stating that a lack of confidence in managing anxieties about adapting to a new environment can prevent people with Parkinson’s disease from participating in physical activities in public spaces [16].

Transportation

Four (4) articles provided evidence of transportation difficulties, including limited access to transportation services or ability to drive, that people with Parkinson’s disease face in reaching healthcare services. A study conducted in the USA showed that a lack of transportation was a major reason for not accessing mental health and other health care services for 8–12%of people with Parkinson’s disease [15, 28]. Similarly, qualitative studies from the UK and the USA identified a lack of transportation as a significant perceived barrier for reaching facilities for physical activities [16, 18].

Cost for healthcare services

Nine (9) articles discussed the financial hardship of people with Parkinson’s disease in paying for healthcare services. These financial hardships were comprised of: (a) limited resources to pay out of pocket, (b) not having health insurance, and (c) lack of insurance coverage. Several studies showed that people with Parkinson’s disease tend to not use healthcare services for non-motor symptoms [15, 28], as well as they tend not to subscribe to community facilities for physical activity [16] or use home care services [11] because of their inability to afford the services. It is also the biggest cause of non-adherence to the pharmacological regimens [17, 20, 23]. Various articles have also expressed that a lack of coverage of health insurance can also prevent people with Parkinson’s from accessing necessary health care services [28, 36, 37]. For example, the use of Medicaid and private insurance predicts a lesser administration of stereotactic deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery as treatment for Parkinson’s disease, in the USA [36].

System-level barriers

This section pertains to barriers related to the healthcare system and associated providers that are implicated in the inappropriate delivery and lack of availability of healthcare services.

Inappropriate delivery of healthcare services

Twenty (20) of the 38 articles reported barriers related to inappropriate delivery of healthcare services. Levesque et al. (2013, p.6) denoted appropriateness as “the fit between services and clients need, its timeliness, the amount of care spent in assessing health problems and determining the correct treatment and the technical and interpersonal quality of the services provided” [8]. The reported barriers in the reviewed articles related to the inappropriate delivery of healthcare services were: (a) delays in the confirmation of diagnoses; (b) poor coordination of interprofessional care that included long waiting time for specialist visits, a lack of clinical referrals, and a lack of coordinated communication between the care settings; (c) poor communication skill of healthcare providers within a care setting; and (d) disparities that exist in the healthcare system and prevent equitable access to healthcare services.

Generally, a confirmed diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease is made by a neurologist. However, an article by Khalil et al. (2016) reported that people with Parkinson’s disease typically undergo a stressful process of first consulting with their general physicians to establishing a diagnosis before being referred to a neurologist for a confirmation of their diagnosis [13]. Khalil et al. (2016) further added that the delay in reaching a diagnosis not only caused undue distress for people with Parkinson’s disease, but that the delay also prevent them from accessing required health services in a timely manner. Worth (2007) also identified that delays or inaccurate diagnosis is a common problem in the care pathway for people with Parkinson’s disease [7]. These delays or inaccurate diagnoses can inhibit early treatments that may slow the progression of the disease if administered as early as possible.

Poor interprofessional coordination between healthcare settings exists in the care of Parkinson’s disease [6, 28]. A significant gap in care is experienced when people with Parkinson’s disease try to access various interprofessional specialists for the confirmation of their diagnosis, services for mental health problems and physiotherapy, despite the fact that existing international guidelines recommend quick referral processes and prompt access to specialist care to uphold the best outcome for patients [7, 12, 13, 15]. Worth (2007) expressed that a significant number of people with Parkinson’s disease begin pharmacological treatment for their condition, based on their general practitioner’s guidelines, despite forgoing diagnostic confirmation by a neurological specialist [7]. Worth (2007) also added that the long waiting periods for the specialist’s visit is an underlying reason that confers a legitimate obligation for the general practitioner to initiate the medication before the patients see a specialist [7]. On the other hand, some people with Parkinson’s disease who showed symptoms but could not start medication as they were waiting for specialists’ appointment [7]. Worth also found that some people had been diagnosed incorrectly by general physicians [7]. The consequence of the delayed or inaccurate diagnosis can affect patients both psychologically and physiologically [7]. Other authors confirmed Worth’s findings [6].

The next issue related to uncoordinated care is a lack of interprofessional referrals. In the study of 755 participants in the USA about 55%of people with Parkinson’s disease found that their doctors were not adequately perceptive of Parkinson’s related mental health issues [15]. The study also showed 28%of people with Parkinson’s disease perceived that they were mistreated by doctors for mental health problems [15]. Conversely, referrals for mental health services were not provided for about 39%of the observed participants with Parkinson’s disease [15]. Similarly, related studies reported that people with Parkinson’s disease do not receive individualized exercise programs or physiotherapy and face difficulties in accessing more informal outreach programs [12, 13].

Another important topic related to uncoordinated care is the lack of coordinated communication between primary and secondary care settings for the management of Parkinson’s disease. Van Der Eijk et al. (2013) argued that the lack of communication and coordination across different settings is a systemic barrier implicated in disabled people with Parkinson’s disease in patient-centered collaborative care [25].

Communication breakdown between people with Parkinson’s disease and healthcare professions can also arise due to poor communication skills of the HCPs on an individual basis [11–13, 26]. Studies demonstrated poor communication skills of HCPs can put people with Parkinson’s disease in distressing situations. Studies show that people with Parkinson’s disease experience undue duress while awaiting an accurate diagnosis [13]. Although individuals with Parkinson’s viewed informative updates as a source of psychological relief during the waiting period, many reported that proper explanations and information were not provided to them [13]. Even after reaching an accurate diagnosis, many people with Parkinson’s disease are not provided with the necessary health information that they require to understand the disease, manage the condition, and promote their health independently [11, 12, 14]. This poor communication may lead to poor self-care of people with Parkinson’s disease [12, 15]. Similarly, Lennaerts et al., (2019) showed that the a lack of communication and information continuity in situations where different healthcare professionals are involved act as barrier for providing palliative care.

Disparities in the health care system prevent people with Parkinson’s disease from reaching healthcare services necessary for an initial diagnosis and management of symptoms. Studies showed non-white Americans are half as likely to be diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the USA, as well as having a lesser access to healthcare services including medication, neurologist’s care, physiotherapy, and deep brain stimulation surgery [36–40]. The social stigma around having a mobility disorder specialist may also prevent people with Parkinson’s disease from accessing the required specialist’s services [28]. Stigma is also found as a barrier to the utilization of mental health services [34]. Furthermore, Saunders-Pullman et al. (2011) showed females with Parkinson’s disease experience more delay in having movement disorder specialist visits [41] and Dahodwala et al. (2018) expressed that fewer females have caregivers on average when compared with males with the condition [42]. Saunders-Pullman et al. (2011) expressed that the difference in progression of disease and family history may contribute to the disparity of having a movement disorder specialist for females [41]. But these factors can not fully account for the problem. Dahodwala et al. (2018) argued that a vast majority of the caregivers for people with Parkinson’s disease are spouse or partners [41]. Females with Parkinson’s disease are less likely to receive care from their male partners as women usually shoulder the burden of caregiving duties, not men.

Availability of health care services

Nine (9) articles showed that many people with Parkinson’s disease cannot access healthcare services because of the unavailability of services. The availability of healthcare services is referred to as a service’s ability to be physically accessed by patients, within a prompt span of time [8]. The unavailable health care services for this demographic includes specialist care, services for physical activities, and pharmaceutical supplies during hospital admission [15, 16, 19, 22, 28, 29, 43].

Specialist services including access to mental health experts, rehabilitation experts, and neurologists are particularly unavailable in many underserviced localities [15, 28, 29]. In studies within the USA, a lack of mental health services was reported by 25%[15] and a lack of specialty services was reported by 14%of observed patients with Parkinson’s disease [28]. Even where these services exist, the quality of the services are often unacceptably diminished in capacity or capability [15]. Similarly, in a study in Australia, 20%of people who live in rural locale have had to travel more than 100 km one-way to access neurologists and rehabilitation professionals [29]. Recent studies from China and India, conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic situation, displayed that people with Parkinson’s disease faced added inaccessibility to their standard healthcare services, due to the infection prevention and control measures taken during this period [44, 45].

Moreover, a UK based study reported that people with Parkinson’s disease could not access specialists’ care as frequently as they felt was necessary for them [46]. The study reported only half of its participants had seen a hospital-based doctor and a quarter or less had seen other health care professionals once a year [46]. The most frequently reported dissatisfaction is related to access to a physiotherapist [46]. However, the study data that was reviewed for this report, was documented 20 years ago and no recent studies were conducted to confirm the findings.

The need for services for physical activity and exercise is frequently expressed throughout the reviewed literature [12, 16]. A study conducted in the UK has shown that people with Parkinson’s disease receive limited services for physical activity through primary health care services [16] and the available services for physical activity and exercise including services of physiotherapists and gym programs do not fulfill the need for personalized care [12]. People with Parkinson’s disease find it hard to get services that accommodate Parkinson’s disease-specific problems [12]. Another study showed that the inaccessible environment of places where exercise services are offered to disrupt people with Parkinson’s disease from participating in physical activity [16]. Similarly, Derry et al. (2010) found that not having Parkinson’s disease medication in-stock at hospitals is a notable reason for missed doses of drugs for about 12%Parkinson’s patients admitted to hospitals [22].

DISCUSSION

This scoping review intended to identify barriers that prevent people with Parkinson’s disease from accessing healthcare services. Reviewed literature showed that barriers for accessing health services occurred at two levels: at the person-level and at the system-level. In addition to the barriers reported in previous review studies [6, 7], the current scoping review highlighted the person-level barriers that affects people with Parkinson’s ability to engage in healthcare.

The issue of access to services for people with Parkinson’s disease has gained the momentum for intellectual inquiry in the last ten years. The increase of disease burden and compatibility of the healthcare systems in fulfilling the healthcare needs of people with Parkinson’s disease are two possible reasons as to why access to healthcare services has become a more pressing concern for people with Parkinson’s disease in recent years. A recent global study has shown that the disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost and mortality from Parkinson’s disease has increased substantially from 1990 to 2015 [47]. The disease burden is increased because of an aging population and therefore increased prevalence of the disease [48]. Despite the increased burden, the healthcare systems have not proportionally developed to fulfill the healthcare needs of people with Parkinson’s disease. A recent survey conducted in Canada showed that the nation’s healthcare system is not accessible for a significant population of people with Parkinson’s disease [49]. This scoping review has revealed that access to healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s disease is a problem for many other developed counties such as the USA, the UK, and Australia. This scoping review could not find any studies that were conducted in the context of developing countries. Therefore, further research is recommended for exploring access to healthcare services issues for people with Parkinson’s disease in developing countries.

Many barriers interrupt access to healthcare services for people with Parkinson’s disease. In addition to the current knowledge from other review articles [6, 7], this scoping review has identified evidence that has revealed barriers implicated in both the patient and systemic sides of healthcare. Importantly, this review has identified patient-related barriers that are not emphasized in preceding reviews. For example, poor health literacy is one of the barriers that has not been reported in previous reviews. As found in this scoping review, several articles reported that people with Parkinson’s disease have poor health literacy that includes poor knowledge of their diagnosis, treatments, prognosis, health promotion activities, and use of assistive devices [11–14, 20, 37]. The poor health literacy of people with Parkinson’s disease not only affects their access to healthcare but also their health-related outcomes [50]. Studies have shown that patients with inadequate health literacy are 1.5 to 3 times more likely to have poor health-related outcomes [51]. Thus, interventions targeting to overcoming the person-level barriers to access healthcare services is required for people with Parkinson’s disease.

A considerable number of articles in the scoping review have identified that patient-HCP disparities in communications are a significant barrier in accessing healthcare services [11–15, 28, 29]. The communication impairments of people with Parkinson’s has also been reflected in other review studies [52, 53]. These prior studies have suggested addressing the important barrier to make the healthcare journey of people with Parkinson’s disease more collaborative and patient centered [52, 54]. Considering the significance of communication problems, international guidelines on Parkinson’s disease have emphasized empowering people with Parkinson’s disease to facilitate their participation in healthcare processes and decision-making [55, 56]. Therefore, the development of interventions to address the aforementioned communication problems should be considered.

Moreover, communication in healthcare is a two-way process between patients and HCPs. Studies reported the breakdowns of communication could happen from either side of the patient-HCP interface [11–14]. Nonetheless, the healthcare professionals should achieve the necessary communication skills through the training they attend before they enter in practice; the opportunity of improving communication skills of patients are scarce by comparison. Besides, as found in the scoping review, to a great extent, the patient-HCPs communication discrepancies are caused by the difficulty of persons with Parkinson’s disease to communicate effectively with HCPs. For instance, Dobkin et al. (2013) stated that people with Parkinson’s disease struggle to express their mental health problems to healthcare professionals [15]; Giles & Miysaki (2009) detailed that anxiety, lack of confidence and poor health-literacy of persons with Parkinson’s disease, all affect communication with HCPs [11]. Thus, the need for mediation of communication, particularly for people with Parkinson’s disease, is warranted.

There are limitations in this scoping review. The scoping review did not consider searching the gray literature and conference papers; therefore, anecdotal evidence has not been considered. Furthermore, this scoping review only included articles that were published in English that might have caused articles retrieval mainly from western countries with less representation of developing countries.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the barriers to accessing healthcare services include both person-level and system-level barriers. The overarching barriers are poor health literacy, poor communication along the patients-healthcare provider interface, poor coordination between healthcare settings, and a lack of availability of mental health and rehabilitation services. A significant gap remains in current practice for overcoming the person-level barriers for people with Parkinson’s disease. Thus, the development of appropriate interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease is recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Paola Durando, Health Sciences Librarian, Queens University Library for her contribution in developing the search strategies for the scoping review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

[1] | Hirsch L , Jette N , Frolkis A , Steeves T , Pringsheim T ((2016) ) The incidence of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 46: , 292–300. |

[2] | Pringsheim T , Jette N , Frolkis A , Steeves TDL ((2014) ) The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord 29: , 1583–1590. |

[3] | Grimes D , Firzpatrick M , Gordon J , Miyasaki J , Fon EA , Schlossmacher M , Suchowersky O , Rajput A , Lafontaine AL , Mestre T , Appel-Cresswell S , Kalia SK , Schoffer K , Zurowski M , Postuma RB , Udow S , Fox S , Barbeau P , Hutton B ((2019) ) Canadian guideline for Parkinson disease. CMAJ 191: , E989–1004. |

[4] | Hobson DE , Lix LM , Azimaee M , Leslie WD , Burchill C , Hobson S ((2012) ) Healthcare utilization in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A population-based analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18: , 930–935. |

[5] | Wolfson C , Fereshtehnejad SM , Pasquet R , Postuma R , Keezer MR ((2019) ) High burden of neurological disease in the older general population: Results from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Eur J Neurol 26: , 356–362. |

[6] | Schuller KA , Vaughan B , Wright I ((2017) ) Models of care delivery for patients with Parkinson disease living in rural areas. Fam Community Health 40: , 324–330. |

[7] | Worth PF ((2007) ) A perspective on the current issues in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Br J Hosp Med 68: , S6, S8-11, S4-5. |

[8] | Levesque JF , Harris MF , Russell G ((2013) ) Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 12: , 18. |

[9] | Arksey H , O’Malley L ((2005) ) Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8: , 19–32. |

[10] | Levac D , Colquhoun H , O’Brien KK ((2010) ) Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5: , 69. |

[11] | Giles S , Miysaki J ((2009) ) Palliative stage Parkinson’ s disease: Patient and family experiences of health-care services. Palliat Med 23: , 120–125. |

[12] | Davis JT , Ehrhart A , Trzcinski BH , Kille S , Mount J ((2003) ) Variability of experiences for individuals living with parkinson disease. Neurol Rep 27: , 38–45. |

[13] | Khalil H , Nazzal M , Al-Sheyab N ((2016) ) Parkinson’s disease in Jordan: Barriers and motivators to exercise. Physiother Theory Pract 32: , 509–519. |

[14] | Quinn L , Busse M , Khalil H , Richardson S , Rosser A , Morris H ((2010) ) Client and therapist views on exercise programmes for early-mid stage Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Disabil Rehabil 32: , 917–928. |

[15] | Dobkin RD , Rubino JT , Friedman J , Allen LA , Gara MA , Menza M ((2013) ) Barriers to mental health care utilization in Parkinson’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 26: , 105–116. |

[16] | Elsworth C , Dawes H , Sackley C , Soundy A , Howells K , Wade D , Hilton-Jones D , Freebody J , Izadi H ((2009) ) A study of perceived facilitators to physical activity in neurological conditions. Int J Ther Rehabil 16: , 17–24. |

[17] | James D , Kyaw P , John R , Helen K , Deane OL ((2012) ) Systematic review on factors associated with medication non-adherence in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18: , 1053–1061. |

[18] | Rossi A , Torres-Panchame R , Gallo PM , Marcus AR , States RA ((2018) ) What makes a group fitness program for people with Parkinson’s disease endure? A mixed-methods study of multiple stakeholders. Complement Ther Med 41: , 320–327. |

[19] | Rumund van A , Weerkamp N , Tissingh G , Zuidema SU , Koopmans RT , Munneke M , Poels PJE , Bloem BR ((2014) ) Perspectives on Parkinson disease care in Dutch nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15: , 732–737. |

[20] | Shin JY , Habermann B , Pretzer-Aboff I ((2015) ) Challenges and strategies of medication adherence in Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap) 36: , 192–196. |

[21] | Valldeoriola F , Coronell C , Pont C , Buongiorno MT , Cámara A , Gaig C , Compta Y , Camara A , Gaig C , Compta Y , ADHESON Study Group ((2011) ) Socio-demographic and clinical factors influencing the adherence to treatment in Parkinson’s disease: The ADHESON study. Eur J Neurol 18: , 980–987. |

[22] | Derry CP , Shah KJ , Caie L , Counsell CE ((2010) ) Medication management in people with Parkinson’s disease during surgical admissions. Postgrad Med J 86: , 334–337. |

[23] | Bainbridge JL , Ruscin JM ((2009) ) Challenges of treatment adherence in older patients with Parkinson’s disease. Drugs Aging 26: , 145–155. |

[24] | Erickson CL , Muramatsu N ((2004) ) Parkinson’s disease, depression and medication adherence: Current knowledge and social work practice. J Gerontol Soc Work 42: , 3–18. |

[25] | Van Der Eijk M , Nijhuis FAP , Faber MJ , Bloem BR ((2013) ) Moving from physician-centered care towards patient-centered care for Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 19: , 923–927. |

[26] | Lennaerts H , Steppe M , Munneke M , Meinders MJ , Van Der Steen JT , Van Den Brand M , Van Amelsvoort D , Vissers K , Bloem BR , Groot M ((2019) ) Palliative care for persons with Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study on the experiences of health care professionals. BMC Palliat Care 18: , 1–9. |

[27] | Hurt CS , Rixon L , Chaudhuri KR , Moss-Morris R , Samuel M , Brown RG ((2019) ) Barriers to reporting non-motor symptoms to health-care providers in people with Parkinson’s. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 64: , 220–225. |

[28] | Lageman SK , Cash T V , Mickens MN ((2014) ) Patient-reported needs, non-motor symptoms, and quality of life in essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 4: , 240. |

[29] | Lubomski M , Louise Rushworth R , Lee W , Bertram K , Williams DR ((2013) ) A cross-sectional study of clinical management, and provision of health services and their utilisation, by patients with Parkinson’s disease in urban and regional Victoria. J Clin Neurosci 20: , 102–106. |

[30] | Richfield EW , Jones EJS , Alty JE ((2013) ) Palliative care for Parkinson’s disease: A summary of the evidence and future directions. Palliat Med 27: , 805–10. |

[31] | Beaudet L , Ducharme F ((2013) ) Living with moderate-stage parkinson disease: Intervention needs and preferences of elderly couples. J Neurosci Nurs 45: , 88–95. |

[32] | Mestre TA , Teodoro T , Reginold W , Graf J , Kasten M , Sale J , Zurowski M , Miyasaki J , Ferreira JJ , Marras C ((2014) ) Reluctance to start medication for Parkinson’s disease: A mutual misunderstanding by patients and physicians. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20: , 608–612. |

[33] | Shin JY , Habermann B ((2016) ) Initiation of medications for Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative description. J Clin Nurs 25: , 127–133. |

[34] | Troeung L , Gasson N , Egan SJ ((2015) ) Patterns and predictors of mental health service utilization in people with Parkinson’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 28: , 12–18. |

[35] | Hurt CS , Rixon L , Chaudhuri KR , Moss-Morris R , Samuel M , Brown RG ((2019) ) Identifying barriers to help-seeking for non-motor symptoms in people with Parkinson’s disease. J Health Psychol 24: , 561–571. |

[36] | Chan AK , McGovern RA , Brown LT , Sheehy JP , Zacharia BE , Mikell CB , Bruce SS , Ford B , McKhann GM 2nd ((2014) ) Disparities in access to deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson disease: Interaction between African American race and Medicaid use. JAMA Neurol 71: , 291–299. |

[37] | Saadi A , Himmelstein DU , Woolhandler S , Mejia NI ((2017) ) Racial disparities in neurologic health care access and utilization in the United States. Neurology 88: , 2268–2275. |

[38] | Dahodwala N , Siderowf A , Xie M , Noll E , Stern M , Mandell DS ((2009) ) Racial differences in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24: , 1200–1205. |

[39] | Dahodwala N , Xie M , Noll E , Siderowf A , Mandell DS ((2009) ) Treatment disparities in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 66: , 142–145. |

[40] | Willis AW , Schootman M , Evanoff BA ((2011) ) Neurologist care in Parkinson disease A utilization, outcomes, and survival study. Neurologu 77: , 851–858. |

[41] | Saunders-Pullman R , Wang C , Stanley K , Bressman SB ((2011) ) Diagnosis and referral delay in women with Parkinson’s disease. Gend Med 8: , 209–217. |

[42] | Dahodwala N , Shah K , He Y , Wu SS , Schmidt P , Cubillos F , Willis AW ((2018) ) Sex disparities in access to caregiving in Parkinson disease. Neurology 90: , E48–E54. |

[43] | Hou JG , Wu LJ , Moore S , Ward C , York M , Atassi F , Fincher L , Nelson N , Sarwar A , Lai EC ((2012) ) Assessment of appropriate medication administration for hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18: , 377–381. |

[44] | Guo D , Han B , Lu Y , Lv C , Fang X , Zhang Z , Liu Z , Wang X ((2020) ) Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis 2020: , 1216568. |

[45] | Prasad S , Holla V , Neeraja K , Surisetti B , Kamble N , Yadav R , Pal P ((2020) ) Impact of prolonged lockdown due to COVID-19 in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurol India 68: , 792–795. |

[46] | Peto V , Fitzpatrick R , Jenkinson C ((1997) ) Self-reported health status and access to health services in a community sample with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil 19: , 97–103. |

[47] | Feigin VL , Krishnamurthi RV , Theadom AM , Abajobir AA , Mishra SR , Ahmed MB , Abate KH , Mengistie MA , Wakayo T , Abd-Allah F , et al. ((2017) ) Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol 16: , 877–897. |

[48] | Ray Dorsey E , Elbaz A , Nichols E , Abd-Allah F , Abdelalim A , Adsuar JC , Ansha MG , Brayne C , Choi JYJ , Collado-Mateo D , Dahodwala N , Do HP , Edessa D , Endres M , Fereshtehnejad SM , Foreman KJ , Gankpe FG , Gupta R , Hankey GJ , Hay SI , Hegazy MI , Hibstu DT , Kasaeian A , Khader Y , Khalil I , Khang YH , Kim YJ , Kokubo Y , Logroscino G , Massano J , Ibrahim NM , Mohammed MA , Mohammadi A , Moradi-Lakeh M , Naghavi M , Nguyen BT , Nirayo YL , Ogbo FA , Owolabi MO , Pereira DM , Postma MJ , Qorbani M , Rahman MA , Roba KT , Safari H , Safiri S , Satpathy M , Sawhney M , Shafieesabet A , Shiferaw MS , Smith M , Szoeke CEI , Tabarés-Seisdedos R , Truong NT , Ukwaja KN , Venketasubramanian N , Villafaina S , Weldegwergs KG , Westerman R , Wijeratne T , Winkler AS , Xuan BT , Yonemoto N , Feigin VL , Vos T , Murray CJL ((2018) ) Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 17: , 939–953. |

[49] | Parkinson Canada (2018) People with Parkinson’s face gaps in the availability of health services. Factum, pp. 28-31. |

[50] | Fleisher JE , Shah K , Fitts W , Dahodwala NA ((2016) ) Associations and implications of low health literacy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract 3: , 250–256. |

[51] | DeWalt DA , Berkman ND , Sheridan S , Lohr KN , Pignone MP ((2004) ) Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med 19: , 1228–1239. |

[52] | A. A ((2010) ) Pros and cons of apomorphine and l-dopa continuous infusion in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15: , S97–S100. |

[53] | Ghahari S , Manji , Man K (2015) Barriers to healthcare utilization for people with Parkinson’s disease. In Society of Occupational Therapy Conference, Kingston. |

[54] | Bloem BR , Stocchi F ((2012) ) Move for Change Part I: A European survey evaluating the impact of the EPDA Charter for People with Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol 19: , 402–410. |

[55] | Grimes D , Gordon J , Snelgrove B , Lim-Carter I , Fon E , Martin W , Wieler M , Suchowersky O , Rajput A , Lafontaine a L , Stoessl J , Moro E , Schoffer K , Miyasaki J , Hobson D , Mahmoudi M , Fox S , Postuma R , Kumar H , Jog M , Gordan J , Snelgrove B , Lim-Carter I , Fon E , Martin W , Wieler M , Suchowersky O , Rajput A , Lafontaine a L , Stoessl J , Moro E , Schoffer K , Miyasaki J , Hobson D , Mahmoudi M , Fox S , Postuma R , Kumar H , Jog M ((2012) ) Canadian guidelines on Parkinson’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci 39: , S1–S30. |

[56] | Stewart DA ((2007) ) NICE guideline for Parkinson’s disease. Age Ageing 36: , 240–242. |