MDSGene: Closing Data Gaps in Genotype-Phenotype Correlations of Monogenic Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

Given the rapidly increasing number of reported movement disorder genes and clinical-genetic desciptions of mutation carriers, the International Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society Gene Database (MDSGene) initiative has been launched in 2016 and grown to become a large international project (http://www.mdsgene.org). MDSGene currently contains >1150 variants described in ∼5700 movement disorder patients in almost 1000 publications including monogenic forms of PD clinically resembling idiopathic (PARK-PINK1, PARK-Parkin, PARK-DJ-1, PARK-SNCA, PARK-VPS35, PARK-LRRK2), as well as of atypical PD (PARK-SYNJ1, PARK-DNAJC6, PARK-ATP13A2, PARK-FBXO7). Inclusion of genes is based on standardized published criteria for determining causation. Clinical and genetic information can be filtered according to demographic, clinical or genetic criteria and summary statistics are automatically generated by the MDSGene online tool. Despite MDSGene’s novel approach and features, it also faces several challenges: i) The criteria for designating genes as causative will require further refinement, as well as time and support to replace the faulty list of ‘PARKs’. ii) MDSGene has uncovered extensive clinical data gaps. iii) The quickly growing body of clinical and genetic data require a large number of experts worldwide posing logistic challenges. iv) MDSGene currently captures published data only, i.e., a small fraction of the available information on monogenic PD available. Thus, an important future aim is to extend MDSGene to unpublished cases in order to provide the broad data base to the PD community that is necessary to comprehensively inform genetic counseling, therapeutic approaches and clinical trials, as well as basic and clinical research studies in monogenic PD.

The advent of next-generation sequencing has led to a quickly growing number of reports on patients with monogenic forms of Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, these data and literature are becoming increasingly difficult to follow and interpret. Numerous reviews have been published attempting to summarize current knowledge on monogenic PD, however, the vast majority of reviews are narrative, i.e., they are not based on an unbiased systematic and comprehensive review of the literature. Perhaps not surprisingly, the amount and quality of genetic data has long surpassed that of published clinical information which is fraught with data data gaps, thus urgently calling for ‘next-generation phenotyping’ [1]. Another related problem has emerged through the accelerated reporting of putative novel genes linked to or associated with PD and other movement disorders. The majority of genes and loci in the frequently published numeric list of ‘PARK’s have either not yet been independently confirmed, are duplicated in the case of SNCA or represent mere risk factors [2, 3]. It was on this background that the International Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) Gene Database (MDSGene) initiative was launched in 2016 and has now grown to become a large international project encompassing genes for PD as well as for several other inherited movement disorders [4] (http://www.mdsgene.org).

At present, MDSGene aims to provide a comprehensive online resource linking reported genetic mutations with movement disorder phenotypes and other demographic and clinical information. It is sponsored by MDS with the aim to comprehensively extract, summarize, and curate data on the individual level published in the English language. Data extraction and curation for MDSGene is performed according to a standardized data extraction protocol by clinicians, geneticists, and epidemiologists. MDSGene currently contains >1150 variants reported in ∼5700 movement disorder patients from almost 1000 publications including monogenic forms of Parkinson’s disease clinically resembling the idiopathic form (PARK-PINK1, PARK-Parkin, PARK-DJ-1, PARK-SNCA, PARK-VPS35, PARK-LRRK2), as well as of atypical PD (PARK-SYNJ1, PARK-DNAJC6, PARK-ATP13A2, PARK-FBXO7). Additional confirmed PD genes/strong genetic risk factors, e.g., CHCHD2 as well as GBA, will soon be added to the database.

Curation of clinical data is carried out by movement disorder fellows and supervised by movement disorder experts, whereas genetic data, along with pathogenicity scoring of each individual reported mutation/variant, is performed by geneticists. In brief, pathogenicity of reported variants is classified as ‘possible’, ‘probable’, or ‘definite’ based on the following criteria: i) co-segregation with disease in the reported pedigrees and/or the number of reported mutation carriers, ii) frequency in ∼120,000 ethnically diverse individuals from the gnomAD (Genome Aggregation Database) browser (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), iii) CADD (“Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion”) score as an in-silico measure of deleteriousness of genetic variants [5], and iv) reported molecular evidence from in-vivo and/or in-vitro studies. Each evidence domain is divided into four categories, each accumulating specific points, weighted by category (for further detail, please see http://www.mdsgene.org/methods and [6]. Reported genetic variants that are classified as benign using this scoring algorithm are not listed in MDSGene.

Inclusion of genes into MDSGene is based on the recommendations of the MDS Task Force for Nomenclature of Genetic Movement Disorders. These recommendations provide lists of genes for which confirmatory evidence of a causal relationship to a movement disorder phenotype is available [2]. Accordingly, MDSGene focuses on these causative gene mutations. This is consistent with the aim to enable genotype-phenotype correlations at the individual level as well as to describe these relationships at the group level. It will be very interesting, in the future, to potentially broaden the scope of MDSGene by including genetic risk factors as modifiers of phenotype. Genome-wide association studies of PD have identified at least 29 genome-wide significant risk loci [7, 8] indirectly linked to nearby genes, which, presumably, influence disease penetrance and expressivity in patients with monogenic PD. If individual-case phenotypic data on individuals carrying risk factor mutation become more widely available, this type of data could also be incorporated into MDSGene in order to allow relationships between causal and modifying genetic factors and resulting phenotypes to be described.

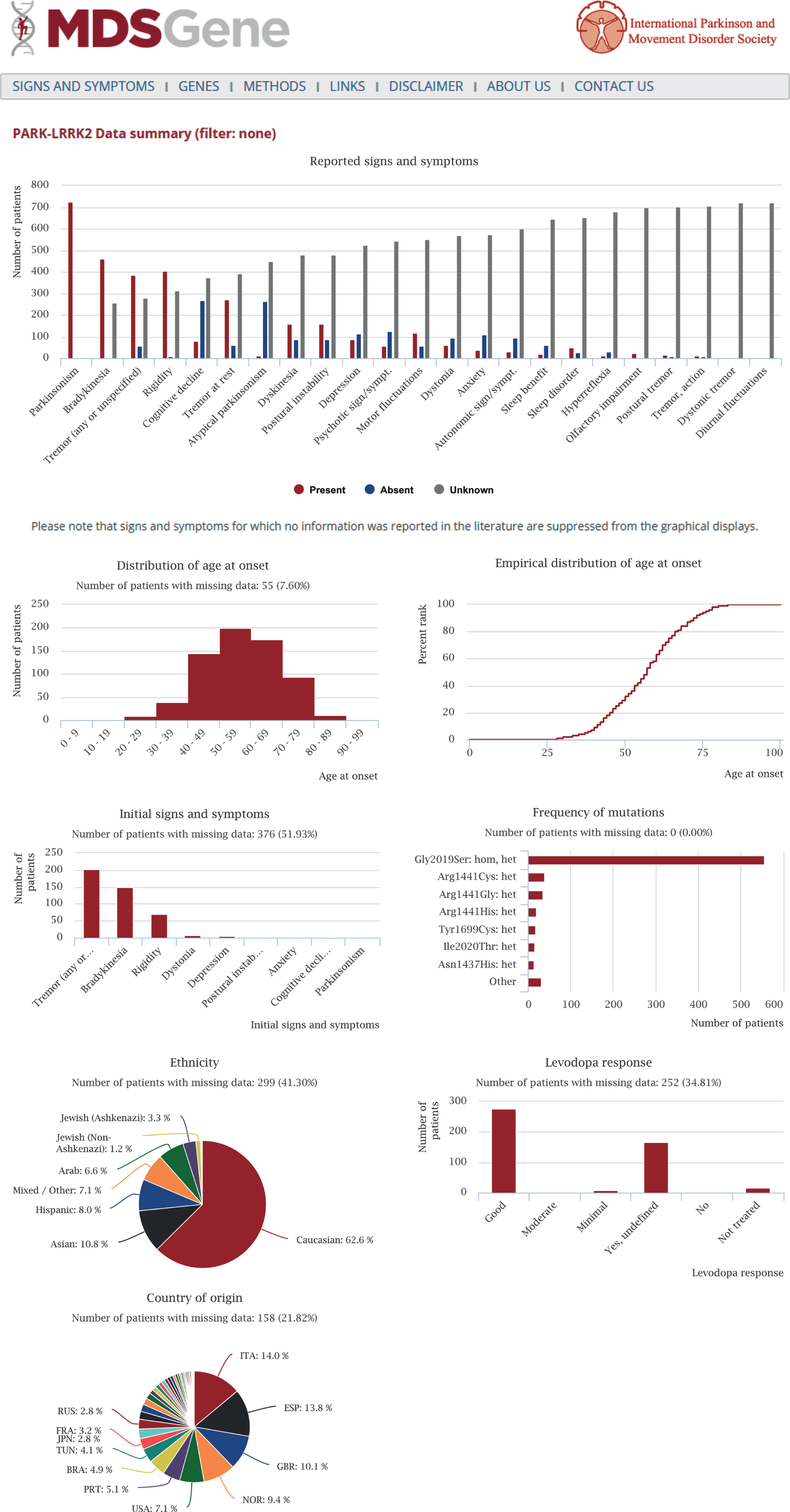

Detailed clinical information contains motor and non-motor signs of movement disorders and can be filtered according to a number of different demographic, clinical or genetic criteria. Summary statistics are readily generated by the MDSGene online tool and allow for unprecedented and easy-access data mining. Fig. 1 shows an output file of the summary statistics tool using PARK-LRRK2 as an example. The first two MDSGene Systematic reviews are based on this resource and cover recessive (PARK-Parkin, PARK-PINK1, PARK-DJ1 [9]) and dominant forms of inherited PD (PARK-SNCA, PARK-LRRK2, PARK-VPS35 [10], respectively. Another feature of MDSGene is its ‘signs and symptoms’ function. Considering all signs and symptoms reported in MDSGene, an optional number of clinical features can be selected in order to obtain suggestions on possible genetic diagnoses using the ‘signs and symptoms tool’. For example, when selecting ‘parkinsonism’, ‘early-onset’, and ‘dyskinesia’, the most likely genetic cause underlying this constellation of signs is given as a Parkin mutation, followed by PINK1 and DJ-1 mutations based on the frequency of these mutations in the database. This aspect of the tool will become functional for other phenotypes as data for more movement disorders are collected and uploaded. For instance, as ataxias are not yet part of MDSGene, the tool may suggest an episodic ataxia as the most likely option when selecting ‘ataxia’ as a sign, whereas, in reality, a dominantly or inherited, non-episodic ataxia would be the much more likely diagnosis. In addition, an algorithm is currently being adapted for this tool taking into account frequencies of individual signs and symptoms among cases with mutations in each gene in conjunction with mutation frequency.

Fig.1

Output file of the summary statistics tool of the MDSGene database using PARK-LRRK2 as an example. The following analyses are generated: frequency of clinical features (red bars – symptom or sign is present; blue bars – symptom or sign is absent; gray bars – no information available), age-at-onset distribution, information on initial signs and symptoms, levodopa response, frequency of mutations, and ethnic background as well as country of origin.

While MDSGene features many novel and unique approaches to address the above-mentioned problems, there are several additional challenges that need to be tackled in future, likely global efforts. First, although the new nomenclature, classification and strict reliance on ‘confirmed movement disorder genes only’ approach that MDSGene is based on most likely represents an advancement over previous systems, it is still imperfect. The decision to confer a ‘PARK’ prefix on a gene according to the new criteria [2, 3] is based on both objective and subjective elements. For example, the criterion requiring confirmation of association by independent groups is straightforward. However, the criterion that the movement disorder must be a prominent aspect of the clinical presentation in a majority of individuals is more difficult to determine. The extent to which parkinsonism dominates the clinical presentation of mutations in a particular gene is difficult to quantify and is often based on subjective assessment of incomplete and poorly detailed reports. Refinement of these criteria as we gain experience operationalizing them for different movement disorder phenotypes will be an ongoing process.

Second and related to the aforementioned problem, is the issue of enormous data gaps in the literature, especially when it comes to clinical descriptions. This is a problem that MDSGene can uncover and bring to the attention of the field. For example, collecting data for MDSGene has revealed that missing data on non-motor signs for PD caused by Parkin, PINK1 or DJ-1 mutations ranges from an alarming ∼45 to almost 100% [9]. It is somewhat surprising that guidelines and accepted quality criteria are in place for many types of studies, such as clinical trials or genome-wide association studies, whereas publications on genotype-phenotype correlations do not fall under any such formal international recommendations.

Along similar lines, there is an overreliance on expert opinion review articles that sometimes perpetuate commonly held notions that may not always reflect the actual situation. When comparing actual data from MDSGene with expert knowlegde on monogenic PD phenotype-genotype correlations published in review articles, we observed important differences [5]. For example, in review articles on Parkin-linked PD, almost half of the experts considered age of onset to be juvenile, while, based on MDSGene data, less than a sixth of the patients have a juvenile age of onset (<20 years). In contrast, none of the reviewers mentioned that age of onset can be late, as is the case in almost a quarter of all Parkin mutation carriers [5]. However, it also has to be borne in mind that genotype-phenotype correlations based on published literature are currently heavily dependent on the individual studies’ inclusion criteria. For example, Parkin mutations have previously been mostly tested for in early-onset cohorts, thus resulting in a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ of finding Parkin mutations in early-onset patients. As ‘hypothesis-free’ (exome and genome) sequencing is becoming increasingly available and will be applied to less restricted patient samples or even in a population-based fashion, we will obtain much more accurate and unbiased phenotype-genotype relationships.

In the meantime, it will take not only scientists but also journal editors to promote the process of more comprehensive and systematic reporting sand to increase the quality of genotype-phenotype investigations in PD and other fields. MDSGene has inspired the development of reporting checklists akin to those available for observational and interventional studies on the Equator Network. We are developing such checklists for each movement disorder phenotype to improve the reporting of clinical information. The intent is that journals can encourage authors to consult and complete these checklists prior to submission of manuscripts to the journal. We anticipate that this may be particularly helpful to authors who are not movement disorder specialists.

Third, the tremendous scope of the task and the vast and quickly growing body of literature poses logistical challenges to keep the data up to date. New software developments such as direct electronic data entry will provide partial solutions to this problem but an important attribute of MDSGene is the participation of movement disorder experts and geneticists carefully curating the clinical and genetic information. The nature of this task requires a very large team of ‘MDSGene members’ worldwide with different areas of expertise to cover the broad field of movement disorders. Currently, the MDSGene ‘team’ consists of more than 80 volunteers in 15 countries. The dedication of this large team is a testament to the perceived value of the information that MDSGene can provide. The opportunity that MDSGene affords to systematically and objectively summarize current knowledge of genotype-phenotype correlations is extremely important, to reveal knowledge gaps, as well as to minimize the perpetuation of misconceptions due to disproportionate influence of a few high-profile reports.

The final major challenge we would like to address in the future is the fact that MDSGene currently captures only a small fraction of the available data on monogenic PD that is available world-wide, i.e., the published data. The lack of novelty of simple reporting of a new mutation in a known gene or an unusual phenotypic expression associated with a known gene or mutation, along with space constraints of journals, will not encourage systematic publication of phenotype-genotype correlations in known genes in the future. Indeed, the field has been moving to reporting group-level data in many instances, thereby precluding any access to individual patient information. Furthermore, availability of diagnostic genetic testing is growing so quickly that the fraction of unpublished patients and mutation carriers even today is much larger than that of published cases. In a recent international survey, we found the number of reported monogenic PD cases to exceed that of published cases by a factor of 2.8 (unpublished data). Therefore, the natural extension of MDSGene will be to include also unpublished cases and we are currently gathering clinical-genetic information on monogenic PD from ∼150 centers world-wide with the aim to include these data in a new branch of MDSGene featuring unpublished data. Novel ways of global team science will have to be pursued in order to provide to the community the urgently needed clinical-genetic data to comprehensively inform genetic counseling, therapeutic approaches and clinical trials, as well as basic and clinical research studies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors do not report any conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MDSGene is supported by a grant from the International Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society. CK is the recipient of a career development award from the Hermann and Lilly Schilling Foundation and from the DFG (FOR2488).

REFERENCES

[1] | Grunewald A , Kasten M , Ziegler A , Klein C ((2013) ) Next-generation phenotyping using the parkin example: Time to catch up with genetics. JAMA Neurol 70: , 1186–1191. |

[2] | Marras C , Lohmann K , Lang A , Klein C ((2012) ) Fixing the broken system of genetic locus symbols: Parkinson disease and dystonia as examples. Neurology 78: , 1016–1024. |

[3] | Marras C , Lang A , van de Warrenburg BP , Sue CM , Tabrizi SJ , Bertram L , Mercimek-Mahmutoglu S , Ebrahimi-Fakhari D , Warner TT , Durr A , Assmann B , Lohmann K , Kostic V , Klein C ((2016) ) Nomenclature of genetic movement disorders: Recommendations of the international Parkinson and movement disorder society task force. Mov Disord 31: , 436–457. |

[4] | Lill CM , Mashychev A , Hartmann C , Lohmann K , Marras C , Lang AE , Klein C , Bertram L ((2016) ) Launching the movement disorders society genetic mutation database (MDSGene). Mov Disord 31: , 607–609. |

[5] | Kircher M , Witten DM , Jain P , O’Roak BJ , Cooper GM , Shendure J ((2014) ) A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet 46: , 310–315. |

[6] | Trihn J , Tadic V , Klein C ((2018) ) How do i confirm that a new mutation is pathogenic?. Mov Disord Clin Pract 5: , 229. |

[7] | Nalls MA , Pankratz N , Lill CM , Do CB , Hernandez DG , Saad M , DeStefano AL , Kara E , Bras J , Sharma M , Schulte C , Keller MF , Arepalli S , Letson C , Edsall C , Stefansson H , Liu X , Pliner H , Lee JH , Cheng R , International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC); Parkinson’s Study Group (PSG) Parkinson’s Research: The Organized GENetics Initiative (PROGENI); 23andMe; GenePD; NeuroGenetics Research Consortium (NGRC); Hussman Institute of Human Genomics (HIHG); Ashkenazi Jewish Dataset Investigator; Cohorts for Health and Aging Research in Genetic Epidemiology (CHARGE); North American Brain Expression Consortium (NABEC); United Kingdom Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC); Greek Parkinson’s Disease Consortium; Alzheimer Genetic Analysis Group, Ikram MA , Ioannidis JP , Hadjigeorgiou GM , Bis JC , Martinez M , Perlmutter JS , Goate A , Marder K , Fiske B , Sutherland M , Xiromerisiou G , Myers RH , Clark LN , Stefansson K , Hardy JA , Heutink P , Chen H , Wood NW , Houlden H , Payami H , Brice A , Scott WK , Gasser T , Bertram L , Eriksson N , Foroud T , Singleton AB ((2014) ) Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet 46: , 989–993. |

[8] | Chang D , Nalls MA , Hallgrimsdottir IB , Hunkapiller J , van der Brug M , Cai F , International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium; 23andMe Research Team, Kerchner GA , Ayalon G , Bingol B , Sheng M , Hinds D , Behrens TW , Singleton AB , Bhangale TR , Graham RR ((2017) ) A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat Genet 49: , 1511–1516. |

[9] | Kasten M , Hartmann C , Hampf J , Schaake S , Westenberger A , Vollstedt EJ , Balck A , Domingo A , Vulinovic F , Dulovic M , Zorn I , Madoev H , Zehnle H , Lembeck CM , Schawe L , Reginold J , Huang J , Konig IR , Bertram L , Marras C , Lohmann K , Lill CM , Klein C ((2018) ) Genotype-phenotype relations for the Parkinson’s disease genes Parkin, PINK1, DJ1: MDSGene systematic review. Mov Disord 33: , 730–741. |

[10] | Trihn J , Zeldenrust FMJ , Huang J , Kasten M , Schaake S , Petkovic S , Madoev H , Grünewald A , Almuammar S , König I , Lill CM , Lohmann K , Klein C , Marras C ((2018) ) Genotype-phenotype relations for the Parkinson’s disease genes SNCA, LRRK2, VPS35: MDSGene systematic review. Mov Disord, doi:10.1002/mds.27527 |