Photovoice as a Participatory Research Tool in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Abstract

Background:

Photovoice is a qualitative research tool increasingly utilized in the healthcare field to understand the illness experience from the patient and caregiver perspective. This is the first study to evaluate photovoice in the context of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Objective:

A patient and caregiver centered research tool was utilized to gain a greater understanding of challenges faced when living with ALS.

Methods:

Eight patients and three corresponding caregivers participating by taking photographs, writing descriptive text, and participating in individual and group interviews. Inductive thematic analysis was employed to uncover recurring themes.

Results:

Five main themes were identified; 1) facing the diagnosis, 2) loss of function, 3) isolation, 4) health system challenges, and 5) hope. Despite the devasting impact of ALS, the majority of participants reported a surprising amount of positivity in the face of receiving this difficult diagnosis, and demonstrated incredible creativity and adaptability to meet the ensuing loss of function. However, patients and caregivers discussed feelings of isolation and health care system challenges. The importance of hope was a strong and recurring theme.

Conclusions:

The photovoice research tool demonstrates the profound resilience of these participants, and challenges the medical community to find ways of fostering positivity and hope throughout the ALS disease course. Further clinic and community resources, education, and supports are needed to combat the sense of isolation and health care system challenges experienced by patients and their caregivers.

INTRODUCTION

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a devastating motor neuron disease, which causes progressive loss of limb, bulbar and respiratory function, resulting in death usually within 2–5 years [1]. Due to the relentlessly progressive nature of the disease, patients often require increasing assistance with activities of daily living [2]. The quality of life for both patients and caregivers is affected, and supports and resources for emotional and physical needs are at times inadequate [3–5]. Economic pressures, caregiver burden, and psychological distress are common for both patients with ALS and their caregivers [6–8]. It is becoming increasingly recognized that a paradigm shift in medical research is necessary to foster patient (and caregiver) centered research efforts [9, 10].

Photovoice is a qualitative research tool increasingly used in the healthcare field to understand the illness experience from the patient and caregiver perspective [11]. In this research method, participants take photographs that illustrate their circumstances with respect to the topic in question, which is then followed by individual and/or group discussion with researchers [11]. Photovoice has been used as a pilot research tool in a number of neurological disorders, including Parkinson’s [12], Huntington’s [13], myotonic dystrophy [14], and stroke [15], but no studies have utilized the photovoice method in ALS to date.

Using the Photovoice method, this qualitative study aimed to understand the experiences of patients with ALS and their caregivers. This may be useful in order to raise awareness of the impact of ALS on those living with the disease, and to identify topics which may benefit from ongoing advocacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants with a diagnosis of ALS attending the multidisciplinary ALS clinic in Saskatchewan, Canada were recruited to participate. A notification was placed in the provincial ALS society newsletter, and all eligible patients attending the clinic were consecutively invited to participate until recruitment was complete (a predetermined target number of participants was achieved). Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of ALS and age over 18; these patients’ caregivers over the age of 18 were also invited to participate. Patients were excluded if cognitive or language dysfunction prevented them from understanding the study or communicating with the researchers. Consent was obtained and the photovoice method was explained either in person or over the phone. Participants were given an information sheet with instructions on photo-taking and the photovoice method, and were instructed to take photos with their own mobile devices. Eleven patients initially consented, but 3 withdrew consent due to progressing disease and their perceived inability to participate. A total of 8 patients (3 female, 5 male) and 3 corresponding caregivers (all female) consented to participate. We do not present any demographic information in order to reduce the identifiability of the participants; this is particularly important considering the low numbers of participants, the close-knit ALS community, and the small clinic numbers from which we recruited. For clarity, quotations are attributed to either patient (P) or caregiver (C) and their study identification number.

Data collection

Participants were asked to take photos illustrating life with ALS, including challenges and barriers faced, as well as things which facilitated living with the disease. Instructions regarding the content of potential photographs was purposefully left open-ended to maximize participant autonomy, thus ensuring that themes and content were truly patient and caregiver driven. To maintain confidentiality, participants were asked to not take pictures of people. Participants submitted 5–10 photographs with a description of each photograph, which was followed by an individual telephone interview with one researcher to further discuss themes from the photos. Consenting individuals also participated in one of two group discussions, the first with 4 participants (2 patients, 2 caregivers), and second with 3 participants (2 patients, 1 caregiver). The group interviews were done over secure WebEx videoconferencing software. In both the individual and group interviews, participants were invited to describe the photos in context of living with ALS. The semi-structured interview format allowed participants the freedom to discuss the issues which were most important to them. Individual and group interviews were audio recorded and transcribed by the interviewer. The 8 individual interviews lasted between 24–86 minutes (mean 48 minutes), and the group interviews were 49 and 66 minutes in length. The project was approved by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of Saskatchewan.

Data analysis

The data were evaluated according to inductive thematic analysis; a qualitative method of data analysis used to identify and analyze themes or patterns [16]. After the interviews were transcribed, an anonymized version was provided to two researchers (KLS, GH) who independently reviewed the data, and then coded the individual and group interviews to uncover recurring patterns. The researchers refined the emerging themes through a multistage process of continued data review and coding. Discrepancies between researchers were resolved through an iterative process of discussion and reexamination of the themes until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

Five themes and additional related sub-themes were identified; 1) facing the diagnosis, 2) loss of function, 3) isolation, 4) health system challenges, and 5) hope. (Table 1)

Table 1

Themes and Subthemes

| Themes | Subthemes |

| Facing the diagnosis | –Hardship |

| –Disbelief | |

| –Unexpected change in plans | |

| –Finding positivity | |

| Loss of function | –Loss of independence and reliance |

| on caregivers | |

| –Equipment | |

| –Giving up activities | |

| –Need for adaptation | |

| Isolation | –Lack of understanding from friends |

| and strangers | |

| –Caregiver isolation | |

| –Lack of public awareness | |

| regarding ALS | |

| Health system challenges | –Need for additional supports |

| –Need for timely care | |

| Hope | –Time with loved ones |

| –Channeling anger | |

| –Focussing on the positive |

Facing the diagnosis

Receiving the diagnosis of ALS was devastating for all participants. The sense of loss and hardship with facing such a difficult and unexpected diagnosis was evident, and many described a feeling of unreality or disbelief that accompanied the early days of diagnosis.

‘I was devastated. You know, I cried every day for a month ... It changed my world.’ [P1]

‘The first week was really tough. It was hell on earth. Your mind races through everything from, we’ve lived in a house 40 years ... what’s going to happen when I’m not here? ... You find yourself making list after list of things that need to be done ... you want to make sure your family and your spouse are all looked after and there’s no loose ends.’ [P6]

‘It still doesn’t feel like reality. Maybe it never will, until I’m taking my last breath.’ [P7]

However, even in the midst of such distress, there were individuals who saw reasons for optimism or gratitude despite the diagnosis. For all but two participants, a recurring theme around accepting the diagnosis was finding some aspect of positivity to cling to.

‘I have far more time than some individuals who don’t wake up in the morning ... I have this time that I’ve been granted for my good-byes ... that’s basically what keeps me going. I try to be as positive as I can, and pay attention to the time I have left, and I’m thankful that I have that time.’ [P3]

‘It struck me like a crossroads in your life ... you can either go left or you can go right, and I choose to go right ... it’s just the idea that you’ve got to decide how you’re going to deal with it, and there’s just not much point in being anything but positive.’ [P6] (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1

A cross-roads in your life.

Loss of function

All participants discussed the challenges associated with progressive decline in function. The loss of independence, the need for equipment, and the reliance on caregivers were consistently stated sub-themes.

‘He gets frustrated with himself because he can’t come out and help ... he comes out in the yard and sits on the chair and watches everybody work when he’s feeling guilty.’ [C2]

‘Having to actually sell her van was definitely more of a loss of independence, and it was very emotionally difficult for her. Even though she knew she couldn’t [drive] ... But even when we would go to appointments, if we took her van and put the gas in it, she somehow felt more in control.’ [C4]

Participants mourned the loss of previously enjoyed activities, including self-sufficiency in their activities of daily living, but were remarkably creative in adapting to their ‘new normal’.

‘One of the major things ALS has stolen from me is time. It takes so long for me to do things now. Every action seems to be in slow motion ... When eating out, I end up taking half home as I feel I’m keeping my friends too long when I’m still eating an hour and a half or two later ... So, the cracked watch really represents to me how my time is so fractured now.’ [P7] (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2

ALS has stolen my time.

‘That’s where I eat. There’s a pool noodle that helps support the arms. And the bent spoon so I am able to get the food to my mouth which is getting harder and harder every day. You know, as a kid you strive to be able to feed yourself, and [as an adult] you sure don’t want to get someone to have to feed you. But you do adjust to it ... you can’t be afraid to try things and you can’t be afraid to invent.’ [P3] (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3

You can’t be afraid to invent.

‘She couldn’t lift her arms up but she could utilize her hands for a while. If it was elastic to pull down, then she managed. Then we put loops on the sides of her pants so that she could put her thumb in and pull her pants down ... she should have been in Cirque de Soleil because she was so agile - we could lay her clothes on the bed and somehow she would slither into them ... she was determined to keep her independence as much as possible.’ [C4] (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4

She was determined to keep her independence.

Isolation

Participants expressed the concern that both friends and strangers did not understand the disease, or its impact on their functioning. In some cases, this led to a sense of isolation and feeling misunderstood.

‘I’ve never ever talked to anybody that’s going through the same thing, there’s just not enough people that have it. I find that kind of frustrating.’ [P3]

‘I’m always worried that someone’s going to think “Can you not even do that for yourself?” because I can’t do dishes anymore, I can’t fold clothes ... oddly enough, it’s those simple things that I didn’t even think of before.’ [P8]

‘ ... going into long-term care, some of her friends discontinued coming to see her ... and it has nothing to do with the one that’s ill, if the friends are uncomfortable in that environment. But that was very shocking to her and very hurtful.’ [C4]

‘I didn’t take [the picture of the bird sitting in the tree] specifically with anything in mind, but the more I looked at it, the more I thought ... you’re not alone. So, it’s one I actually keep on my phone ... all of those people who know you are with you. You’re just not all alone (crying).’ [P6] (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5

You are not alone.

Caregivers also experienced a sense of isolation, including isolation from their loved one.

‘You don’t realize how much you talk. (Laughter). But he can’t. So, I feel like I’m single because I sit in the living room watching TV by myself, I go out by myself.’ [C5]

Health system challenges

Patients and caregivers felt the need for more supports, and specifically, the need for more timely care. Many also discussed the financial burden associated with ALS. In some cases, although help was provided, it was insufficient for their needs.

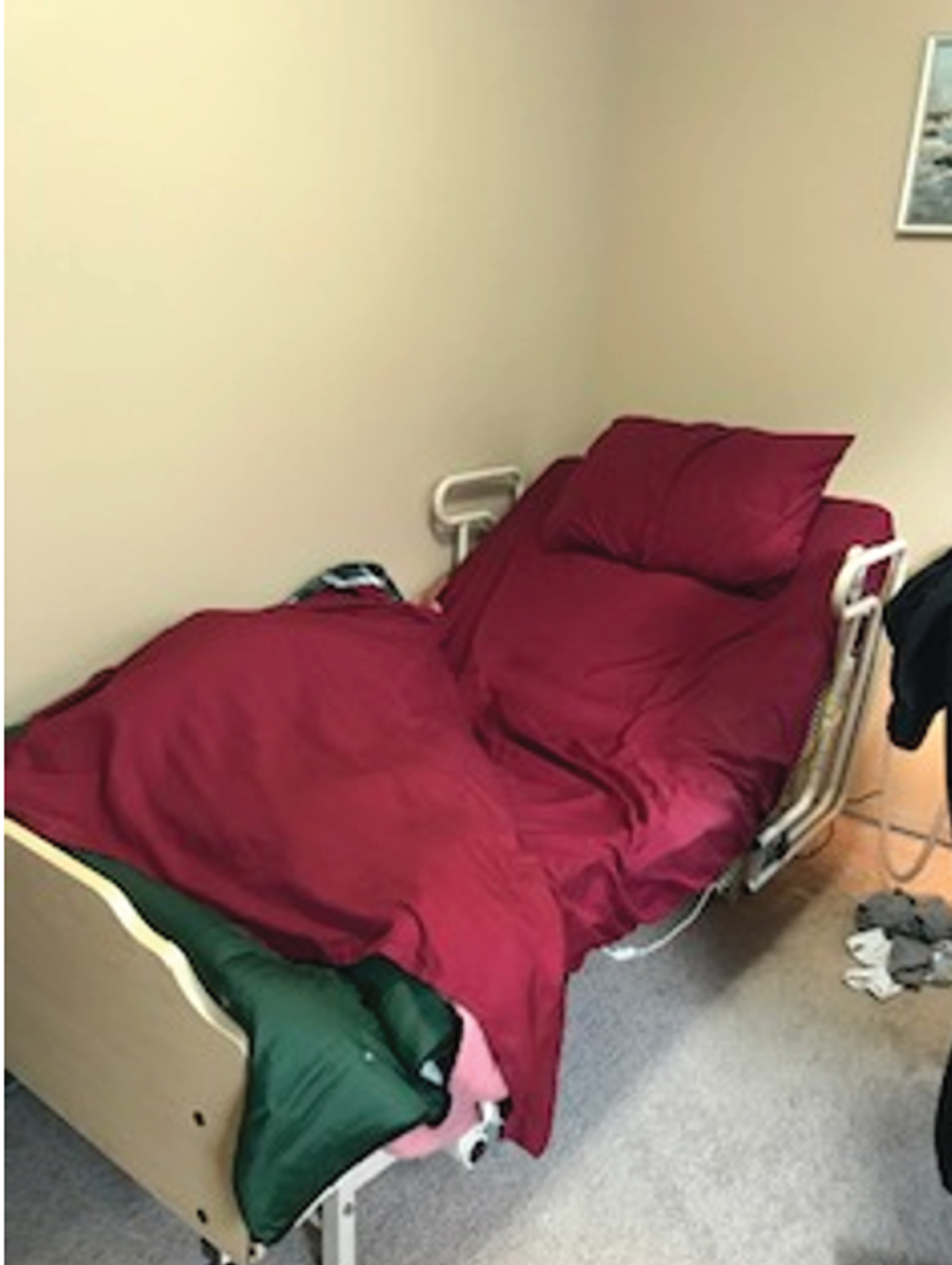

‘[They] had a bed so they loaned it to us, which was really nice. And it’s raised ... so we do [feeding] in bed most of the time ... it was great getting the bed ... but they take extra-long sheets so none of your sheets fit. I don’t think anybody ever thinks about that.’ [C5] (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6

I don’t think anybody ever thinks about that.

‘I just find the whole healthcare system can just be a knee-jerk reaction. They don’t do much until you complain.’ [P7]

One participant told a story of how the lack of wheel-chair accessible bathroom stalls impacted her ability to cope.

‘In regular stalls, there is nothing to use to raise yourself from your seated position ... there is major anxiety when trying to succeed at this feat, when all the while staring down the door you locked for privacy’s sake. If you can’t get up, no one can get in to help you!’ [P7]

The public’s lack of awareness of ALS was also cited as a frustration.

‘Education and public awareness are much needed. I know even with our community members and our family members, lots of people didn’t understand how it began. They said, “oh, your mom can’t have ALS because it starts in your legs.” And I said “well, I think it’s a little bit different for everyone.”’ [C4]

Hope

Despite the upheaval and suffering of living with ALS, participants emphasized the need for hope, and how positivity buoyed them up during the challenges they faced every day.

‘That’s something else that both mom and I wanted to get through with your study. That it’s not over with the diagnosis. There are tons of opportunities if you can brainstorm, have the support, adapt ... . Attitude, it’s all about attitude.’ [C4]

‘I think I [stay positive] because I have to for the sake of my kids... I sometimes think it’s harder for them than it is for me ... I don’t want to waste a minute crying about it ... I just want to enjoy the time that I have with them.’ [P8]

‘[There is] residual anger from the diagnosis and it never leaves your body, it never leaves your mind. I try and channel [it] not so much at external things, but internally so that it keeps driving me ... I’m kind of at peace with this whole thing at the moment ... I’m hoping I can maintain this ... So that you can focus on being the best that you can be ... ’ [P6]

‘The pathway will continue until it’s end ... I hope to a brighter end.’ [P7] (Fig. 7)

Fig. 7

A brighter end.

‘There’s a saying ‘you should not be dying with ALS, you should be living with ALS.’ ... It’s an ugly card we’ve been dealt, but you’ve got to deal with it. To be mad at the world because of it, that makes matters worse ... Right now, we still have tomorrow.’ [P3]

DISCUSSION

Despite the devasting impact of ALS, the majority of participants reported a surprising amount of positivity in the face of receiving this difficult diagnosis, and demonstrated incredible creativity and adaptability to meet the ensuing loss of function. However, patients and caregivers discussed feelings of isolation and health care system challenges. The importance of hope was a recurring and strong theme for both patients and caregivers.

Positivity when receiving the diagnosis, and maintaining hope throughout disease stages were identified as strong themes. Hope has been shown to be a powerful determinant of satisfaction with life, and the importance of hope for those suffering with ALS is widely recognized [8, 17, 18]. Patient-identified factors in facilitating hope include autonomy and agency in decision making, a strong social support, tangible supports (equipment and agencies), and cognitive strategies to promote hope [18]. While there is robust qualitative information extracted from patient and caregiver experiences, there is very little research evaluating interventions to increase hope. It behooves physicians and care providers to find ways of fostering positivity in their interactions with patients and caregivers at all stages of disease. The physician role in fostering hope at the point of initial contact with diagnosis delivery has been previously studied. The manner in which the diagnosis of ALS is delivered has been identified as an area of discontent for patients [19, 20], and has a profound impact on the psychological well-being of patients and their families [21]. This has lead the medical community to investigate current skill in diagnosis delivery and methods of improving physicians’ comfort in breaking bad news in this context [22, 23]. This has included physician surveys and evaluation of trainees’ skill level in diagnosis delivery. Practice recommendations exist to guide physicians in breaking the bad news of an ALS diagnosis and outline the importance of fostering hope [24]. Courses have been developed for neurologists-in-training to improve sensitivity and skill in delivering difficult diagnoses such as ALS [25].

In the literature, less attention has been afforded to how physicians and providers can foster hope throughout the disease course including end of life. A prior study of patients with ALS receiving palliative care showed that individuals differed in their ability to maintain hope, but that hope was not dependent upon disease stage as measured by ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS) or pulmonary function [26]. The results of our study are in keeping with this observation, since participants articulated positivity in stages beginning with diagnosis delivery through to end of life. However, there are few studies which evaluate interventions to foster hope for patients with ALS and their caregivers in the latter stages of disease. Dignity therapy provides persons an opportunity to discuss life events, memories, and accomplishments during a recorded interview. Although it was well received, and may have benefit simply in that regard, there were no statistically significant impacts on objective measures of hope for either patients or caregivers [27, 28]. It is evident from the strong focus on hope provided by the participants in this study, that further attention to this issue is warranted.

Despite the inspiring creativity the patients in this study demonstrated when adapting to their progressive functional losses, it is evident that additional supports would have been beneficial. The need for additional resources to support persons with ALS and their caregivers is a common theme in the existing literature [3–5]. It has been demonstrated that fewer perceived unmet service needs are correlated with better caregiver mental health [29], and that a reciprocal influence between caregiver and patient mental health exists [3]. Provision of adequate resources might not only meet the physical needs, but also address some of the emotional challenges associated with living with this disease for both the patient and the caregiver. Additional education and awareness of ALS at a societal level may serve to mitigate the sense of isolation which many participants described. Isolation has been identified as a factor which disables hope, while tangible resources such as equipment support have been demonstrated to foster hope [18]. This study brings awareness that these factors must be addressed for patients according to individual need.

This study highlights the unique challenges and facilitators linked to this devastating disease in ways not previously recorded. The addition of personal photographs (as opposed to interviews alone) adds an element of intimacy in the discussion of patient experiences with ALS not previously available in the literature. The importance of hope as a mitigating factor and coping strategy to deal with functional losses is central in this study compared to other photovoice studies in neuromuscular disease, but consistent with the previous qualitative literature in ALS. This study provides an additional compelling voice that further study into tangible strategies for bolstering hope in ALS is needed.

Photovoice provides a unique perspective in a climate where research is becoming increasingly patient centered. To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize photovoice in ALS. Studies of photovoice in other neurological diseases such as Huntington’s, myotonic dystrophy, and Parkinson’s disease have concentrated on quality of life, and have served to remind health care professionals to refocus their efforts on disease aspects which are of greatest concern to the patients and their caregivers [12–14]. A study of photovoice in stroke survivors demonstrated three phases of coping; initial physical and emotional impacts, coping with barriers including physical disability, and long-term adaption [15]. Our study differs from the adaptation patterns seen in stroke since ALS follows a very different disease trajectory, with relentlessly progressive disability until death. The use of photographs as a springboard to discuss ideas may resonate with some individuals for whom an interview alone might be daunting or challenging. Going forward, we hope to pilot and assess the routine use of Photovoice to facilitate conversations in our ALS clinic.

A limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size (n = 8). This, however, is comparable to the number of participants obtained in studies utilizing photovoice in other neurological diseases. Another limitation of the study is the requirement for participants to use their own mobile phone with a camera; this has the potential to exclude those without the necessary device. In retrospect, it would have been helpful to obtain some qualitative and quantitative data on the perceived importance and acceptability of photovoice as a research tool. Despite the lack of formal feedback, several participants volunteered that the process was useful in working through difficult feelings and experiences, and found the process of giving voice to their thoughts through pictures very rewarding.

CONCLUSION

The photovoice technique has given a voice to patients with ALS and their caregivers. The profound resilience of these participants is inspiring, and challenges the medical community to find ways of fostering positivity and hope throughout the ALS disease course. Further clinic and community resources are necessary to augment the creativity and adaptability that patients and caregivers already demonstrate when navigating the functional losses caused by ALS; this includes timely access to necessary equipment and support agencies. Education, awareness, and emotional supports through clinic staff and societies are needed to combat the sense of isolation so often experienced by patients and their caregivers. Additional research of strategies to promote hope for patients and caregivers is needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the College of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan for providing funding for Adriana Gunton through a Dean’s Project grant.

REFERENCES

[1] | Hardiman O , Van Den Berg LH , Kiernan MC . Clinical diagnosis and management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. (2011) ;7: (11):639–49. |

[2] | Kiernan MC , Vucic S , Cheah BC , Turner MR , Eisen A , Hardiman O , et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The Lancet. (2011) ;377: (9769):942–55. |

[3] | Chen D , Guo X , Zheng Z , Wei Q , Song W , Cao B , et al. Depression and anxiety in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Correlations between the distress of patients and caregivers. Muscle Nerve. (2015) ;51: (3):353–7. |

[4] | Ng L , Talman P , Khan F . Motor neurone disease: Disability profile and service needs in an Australian cohort. Int J Rehabil Res. (2011) ;34: (2):151–9. |

[5] | Schellenberg KL , Hansen G . Patient perspectives on transitioning to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis multidisciplinary clinics. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2018) ;11: :519–24. |

[6] | Gladman M , Dharamshi C , Zinman L . Economic burden of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A Canadian study of out-of-pocket expenses. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener. (2014) ;15: (5-6):426–32. |

[7] | Bruletti G , Comini L , Scalvini S , Morini R , Luisa A , Paneroni M , et al. A two-year longitudinal study on strain and needs in caregivers of advanced ALS patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener. (2015) ;16: (3-4):187–95. |

[8] | Pagnini F . Psychological wellbeing and quality of life in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A review. Int J Psychol. (2013) ;48: (3):194–205. |

[9] | Frank L , Basch E , Selby JV , Frank L . The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. (2014) ;312: (15):1513–4. |

[10] | de Wit M , Cooper C , Reginster J-Y . Practical guidance for patient-centred health research. The Lancet. (2019) ;393: (10176):1095–6. |

[11] | Catalani C , Minkler M . Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. (2010) ;37: (3):424–51. |

[12] | Roger K , Wetzel M , Penner L . Living with Parkinson’s disease - perceptions of invisibility in a photovoice study. Ageing Soc. (2018) ;38: (5):1041–62. |

[13] | Aubeeluck A , Buchanan H . Capturing the Huntington’s disease spousal carer experience: A preliminary investigation using the ‘Photovoice’ method. Dementia. (2006) ;5: (1):95–116. |

[14] | Ladonna KA , Venance SL . Picturing the experience of living with myotonic dystrophy (DM1): A qualitative exploration using photovoice. (Report). J Neurosci Nurs. (2015) ;47: (5):285–95. |

[15] | Revathi B , Benjamin K , Rennie N , Kezhen F , Judith Goldfinger Z , Carol R . Horowitz. Life after Stroke in an Urban Minority Population: A Photovoice Project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) ;14: (3):293. |

[16] | Braun V , Clarke V . Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) ;3: (2):77–101. |

[17] | Galin S , Heruti I , Barak N , Gotkine M . Hope and self-efficacy are associated with better satisfaction with life in people with ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener. (2018) ;19: (7-8):611–8. |

[18] | Soundy A , Condon N . Patients experiences of maintaining mental well-being and hope within motor neuron disease: A thematic synthesis. Front Psychol. (2015) ;6: :606. |

[19] | Mccluskey L , Casarett D , Siderowf A . Breaking the news: A survey of ALS patients and their caregivers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. (2004) ;5: (3):131–5. |

[20] | Johnston M , Earll L , Mitchell E , Morrison V , Wright S . Communicating the diagnosis of motor neurone disease. Palliat Med. (1996) ;10: (1):23–34. |

[21] | Chio A , Borasio GD . Breaking the news in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Mot Neuron Disord Off Publ World Fed Neurol Res Group Mot Neuron Dis. (2004) ;5: (4):195–201. |

[22] | Schellenberg KL , Schofield SJ , Fang S , Johnston WSW . Breaking bad news in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The need for medical education. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener. (2014) ;15: (1-2):47–54. |

[23] | Aoun SM , Breen LJ , Edis R , Henderson RD , Oliver D , Harris R , et al. Breaking the news of a diagnosis of motor neurone disease: A national survey of neurologists’ perspectives. J Neurol Sci. (2016) ;367: :368–74. |

[24] | EFNS Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis:, Andersen P , Abrahams S , Borasio G , de Carvalho M , Chio A , et al. EFNS guidelines on the clinical management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MALS)–revised report of an EFNS task force. J Neurol. (2012) ;19: (3):360–75. |

[25] | Watling CJ , Brown JB . Education research: Communication skills for neurology residents: Structured teaching and reflective practice. Neurology.E. (2007) ;69: (22):20–6. |

[26] | Fanos JH , Gelinas DF , Foster RS , Postone N , Miller RG . Hope in palliative care: From narcissism to self-transcendence in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Palliat Med. (2008) ;11: (3):470–5. |

[27] | Bentley B , O’Connor M , Kane R , Breen LJ . Feasibility, Acceptability, and Potential Effectiveness of Dignity Therapy for People with Motor Neurone Disease.(Research Article). PLoS ONE. (2014) ;9: (5):e96888. |

[28] | Bentley B , O’Connor M , Breen L , Kane R . Feasibility, acceptability and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for family carers of people with motor neurone disease. BMC Palliat Care. (2014) ;13: (1):12. |

[29] | Peters M , Fitzpatrick R , Doll H , Playford ED , Jenkinson C . The impact of perceived lack of support provided by health and social care services to caregivers of people with motor neuron disease. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. (2012) ;13: (2):223–8. |