Emotional, sexual and behavioral correlates of attitudes toward sex robots: Results of an online survey

Abstract

Understanding people’s attitudes toward sex robots will be essential to facilitate this technology’s likely assimilation into human relationships in a way that maximizes benefit and minimizes conflict within the privacy of people’s bedrooms. This online survey was developed to investigate attitudes toward sex robots. Questions were chosen to explore a variety of emotional, behavioral, and sexual variables that could potentially be pertinent to individual’s receptivity to sex with robots. There were 376 respondents, 84.1% of which were heterosexual. Self-reports of depression, social anxiety, attention deficit disorder, and Asperger’s spectrum all correlated positively with receptivity toward sex robots. Challenges with monogamy, more lifetime sex partners, higher frequency of masturbation, more pornography consumption, greater consumption of alcohol and marijuana, and more frequent use of video games also all correlated positively with receptivity toward sex robots. Curiously, receptivity toward sex robots correlated positively with both the experience of sexual pleasure with human partners and with the experience of anxiety during sex with a human partner. It is our belief that research in this area is paramount to assist psychologists, anthropologists, roboticists, and couples in navigating the intimate challenges of the future.

1.Introduction

The impact of sex tech on human intimacy is a recent and increasingly impactful phenomenon (Doring & Poschl, 2018). Less than two decades ago, the idea that humans could have sex with robots was largely discounted, considered exclusively the purview of science fiction and thus of little interest to most. In 2007, David Levy authored a ground-breaking book predicting the inevitability of love and sex with robots (Levy, 2007). Nonetheless, and in spite of the fact that technology interfaces with almost all aspects of human life, technology’s impact on human intimacy remains relatively unnoticed (Scheutz & Arnold, 2016). Yet technology has proven capable of powerfully impacting human lives in a relatively short period of time. Consider the abrupt adaptation of the world wide web, smart phones, and internet pornography as examples. Recent history has demonstrated the very real ways humans are powerfully and rapidly impacted, for better or for worse, by technological gains.

There is a burgeoning literature on human-robot interaction, with a focus on educational benefits to children (Tazhigaliyeva et al., 2016), and the companionship and care of the elderly (Abdollahi et al., 2017) and the disabled (Jecker, 2020). However, in spite of the fact that sex with robots is controversial and bound with profound ethical and moral challenges (Javaheri et al., 2020), the study of human robot sex remains in its infancy. The Foundation for Responsible Robotics published “Our Future with Robots” (Foundation for Responsible Robotics, 2017) the first-of-its-kind multi-disciplinary report exploring the potential impact of sex robots. International journals and conferences are increasingly engaging scholars from a variety of fields, including technology, artificial intelligence, philosophy, ethics, psychology, and others about the potential implications of human/robot sexual and emotional intimacy. Multiple benefits are expected as sex robots become available. People with disabilities, couples seeking more creative outlets for sexual expression, and those who are geographically isolated are a few likely beneficiaries (McArthur, 2017). However, as with most innovation, negative consequences with this new technology are inevitable. Multiple ethical, legal and moral issues arise from the phenomenon of human intimacy with advanced technology (Richardson, 2019; Danaher & McArthur, 2017; Szczuka & Kramer, 2018; Liberati, 2020). Less advanced sex tech, including sex toys, sex apps, and VR porn have already significantly impacted people’s sex lives in a variety of ways. The extent of influence sex robots will have on human intimate relationships remains a point of controversy and speculation (Johnson and Verdicchio, 2020). Many recognize the very real challenges ahead, including the potential disruption of human-human intimate relationships, the objectification of women, and the modeling of sexual relationships with partners without emotional or sexual needs and that lack sexual agency (Galaitsi et al., 2019; Nyholm & Frank, 2019; Danaher et al., 2018). The potential negative impact of sex robots on women and intimate relationships is considered by some to be so extreme that the Campaign Against Sex Robots was initiated to abolish sex robots in the form of women and girls (Richardson, 2016). Furthermore, it has been suggested that sex robots will have an impact outside of people’s bedrooms. For example, by intensifying feelings of loneliness, and promoting gender inequality, social isolation, and decreased empathy towards women (Torjesen, 2017).

Researchers have only begun to explore the variables impacting people’s attitudes toward sex with robots. Scheutz and Arnold presented the first such survey in 2016 at the International Conference on Human Robot Interaction. Males were found to consistently hold more approving views about sex robots than females, a finding which has been replicated by these researchers (Scheutz and Arnold, 2016; 2018) and others (Nordmo 2020; Brandon et al., in press). This conclusion is interesting in that females were found to be more receptive when interacting with robots in a non-sexual way than males (Nomura et al., 2006). However, it is consistent with much researching indicating that males engage in more and diverse sexual behaviors than females, including masturbation (Herbenick et al., 2010), paraphilias (Dawson et al., 2014), and pornography consumption (Carroll et al., 2017), and they verbalize the desire for sexual frequency (Smith et al., 2011) and variety (Schmitt et al., 2001). In addition, males express a desire for greater numbers of sex partners (McBurney et al., 2005) and report higher libidos than females (Baumeister et al., 2001).

In addition to males expressing more positive attitudes toward sex robots, researchers have found that individuals more willing to take sexual risks and who fantasize more may be more likely to have sex with a robot, as well as folks more interested in sci-fi (Koverola et al. 2020). Consistent with the gendered findings detailed above, males demonstrate more willingness to take sexual risks (Cubbins & Tanfer, 2000), are more apt to pay for sex (Hammond & van Hooff, 2019), and report more frequent sexual fantasies (Wu et al., 2016) than females. Further, researchers have identified similarities in attitudes toward sex robots and prostitutes (Koverola et al. 2020; Gonzales-Gonzales et al. 2019; Richardson 2016), and males are the primary consumers of prostitutes (Hammond & van Hooff, 2019). The perception that sex with robots is an act of infidelity may influence attitudes toward sex robots as well (Szczuka & Kramer, 2018; Brandon et al., in press). Males appear to be less jealous of their partner having sex with a robot (Szczuka & Kramer, 2018).

In spite of these data, the reality of gendered interest in sex with robots remains controversial. Some suggest that the media, societal norms, and sex robot manufacturers fabricate men’s apparent greater interest in sex robots (Troiano et al., 2020). Indeed, some women demonstrate interest in sex with robots (Oleksy & Wnuk, 2021), and robots are already being designed to appeal to female consumers. Nonetheless, the fundamental and substantial discrepancy between male and female psychology (Archer, 2019; Meyers-Levy & Loken, 2015), biology (De Vries & Forger, 2015) and sexual behavior suggests that males will exhibit more interest in and hold more positive attitudes about sex robots than will women. This implies the potential for intensified gender tension as technology increasingly interfaces with human intimacy.

Furthermore, sex robots can be expected to impact not just gender relationships on a societal level, but individual couples in particular. The repertoire of human-robot interaction is expanding at such a rapid rate that researchers suggested the development of a new academic discipline, erobotics, to study and ultimately to positively influence human-machine integration and co-evolution (Dube & Anctil, 2020). Sex robots will likely present unique challenges for couples in long-term intimate relationships. Understanding people’s attitudes toward sex robots will be essential to facilitate this technology’s inevitable assimilation in a way that maximizes benefit and minimizes conflict within the privacy of people’s bedrooms. However, little research is currently available to appreciate these upcoming challenges (Doring et al., 2020). While some couples will likely integrate sex robots in ways that promote mutual sexual satisfaction, other individuals will experience them as threatening to their sex life and relationship.

This research contributes to this discussion of attitudes toward sex robots by exploring possible correlations with variables contributing to mental health, comfort with intimacy, sexual behaviors, and sexual concerns – variables that will ultimately enhance or detract from couples abilities to utilize advanced sex tech in ways that promote human-human intimacy. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore potential correlations between attitudes toward sex robots and typical sexual anxieties (“I feel pressure to perform sexually,” “I’m comfortable telling my partner what I really want in bed,” “I feel my partner would be attracted to my naked body, “I get aroused by pleasing my partner sexually,” “It’s difficult for me to initiate sex because rejection is so uncomfortable,” “I have concerns being a satisfactory lover”), sexual behaviors (frequency of porn use, masturbation, sexual fantasy, adventurous sex practices, number of lifetime sex partners, perception of sex drive), drug and alcohol use, time spent playing video games, comfort with romantic attachment behaviors (“I find it difficult to look in my partner’s eyes during sex,” “My relationship style is best described as..”), as well as attitudes toward prostitution and monogamy. This study aims to enhance our understanding of how emotional and behavioral variables that influence people’s intimate lives may impact people’s attitudes toward sex robots. It is our belief that research in this area is paramount to assist psychologists, anthropologists, roboticists, and couples in navigating the intimate challenges of the future.

2.Methods

2.1.Survey

A 27-question online survey (Table 1) was developed to investigate attitudes toward sex robots. Questions were chosen to explore a variety of emotional, behavioral, and sexual variables that could potentially be pertinent to individual’s receptivity to sex with robots. IRB approval was granted via New Paltz Human Research Ethics Board. Study participants were crowdsourced via Survey Monkey, opting in or out of the survey based on the survey title only. Participants were informed that they would be taking a survey called the “Sexual Attitudes Scale.” After agreeing to take the survey, they received directions offering more specific information. The directions were as follows, “Thank you for completing this confidential survey about sexual attitudes and behaviors. A few of the questions ask about your attitudes toward sex robots. Sex robots are expected to be available in several decades. They will walk, talk, and have sex in a humanoid fashion.” The survey requested information regarding biological sex, gender, sexual orientation, age, and relationship status. Additional questions queried a variety of mental health, behavioral, and sexual data. When appropriate, questions utilized a 5-point Likert scale. Responses were analyzed by biological sex, sexual orientation, age, relationship status and psychological disorder. Surveys were obtained on September 21, 2020 via SurveyMonkey. SurveyMonkey recruits participants via email who have previously offered to complete surveys in exchange for a nominal fee. SurveyMonkey gathers general data on subjects, such as their geographic region and income when they enroll as survey respondents.

3.Results

3.1.Statistical analyses

Descriptive and inferential analyses were performed on the study population, including t-tests, ANOVAs, and bivariate correlations.

3.2.Survey respondents

There were 376 survey respondents, consisting of 166 males, 205 females, and 5 individuals who identified as non-binary. Because of the limited number of non-binary subjects, those 5 were excluded from analysis, leaving a study population of 371, with 44.7% male and 55.3% female. The majority of respondents were heterosexual (84.1%). All respondents were from the United States, with broad geographical distribution as follows: 14.8% in the South Atlantic region, 23.5% Pacific, 13.7% East North Central, 11.7% Middle Atlantic, 11.7% West South Central, 6.0% East South Central, 4.4% West North Central, 10.4% Mountain, and 3.8% from New England. Income ranged from less than $10,000 to greater than $200,000, with a mode of $50,000–$74,999.

Respondents self-identified over the following age ranges: 18–24 years, 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, and 65 years or older. The percentage of respondents in each age bracket is shown in Table 1. There were slightly more individuals 44 years and younger (52.83%) and than individuals 45 years and older (47.17%), with the largest group being 25–34 years.

Relationship status is shown in Table 2. Over half of respondents were either married or in long-term committed relationships.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics of the sample, age (

| Frequency | Percent | |

| 18–24 | 64 | 17.3% |

| 25–34 | 77 | 20.8% |

| 35–44 | 55 | 14.8% |

| 45–54 | 75 | 20.2% |

| 55–64 | 48 | 12.9% |

| 65+ | 52 | 14.0% |

| Total | 371 | 100.0% |

Table 2

Demographic characteristics of the sample, relationship status (

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Single, not dating | 88 | 23.7% |

| Single and dating | 37 | 10.0% |

| Married, or in a long-term committed relationship | 208 | 56.1% |

| Divorced | 27 | 7.3% |

| Widowed | 11 | 3.0% |

| Total | 371 | 100.0% |

Self-reported psychological disorder prevalence is shown in Table 3. Over half of respondents reported struggling with a psychological disorder (51.5%).

Table 3

Demographic characteristics of the sample, psychological disorders (

| Frequency | Percent | |

| Depression | 131 | 35.3% |

| Social anxiety | 140 | 37.7% |

| Asperger’s spectrum | 12 | 3.2% |

| Attention deficit disorder | 37 | 10.0% |

| None of the above | 180 | 48.5% |

| Total | 371 | 100.0% |

3.3.Attitudes towards sex robots and respondent demographics

Responses to two statements regarding attitudes toward sex robots for the entire study population are presented in Table 4. Interestingly, a greater proportion of respondents indicated looking forward to when sex robots are easily available (18.6%) than respondents that indicated having a strong interest in having sex with a robot (7.5%).

Table 4

Responses regarding attitudes towards sex robots (

| Strongly disagree/Not at all | Strongly agree/Agree/A lot/Great deal | |

| I have interest in having sex with a robot | 67.4% | 7.5% |

| I look forward to a time when sex robots are easily available | 42.3% | 18.6% |

3.3.1.Influence of biological sex

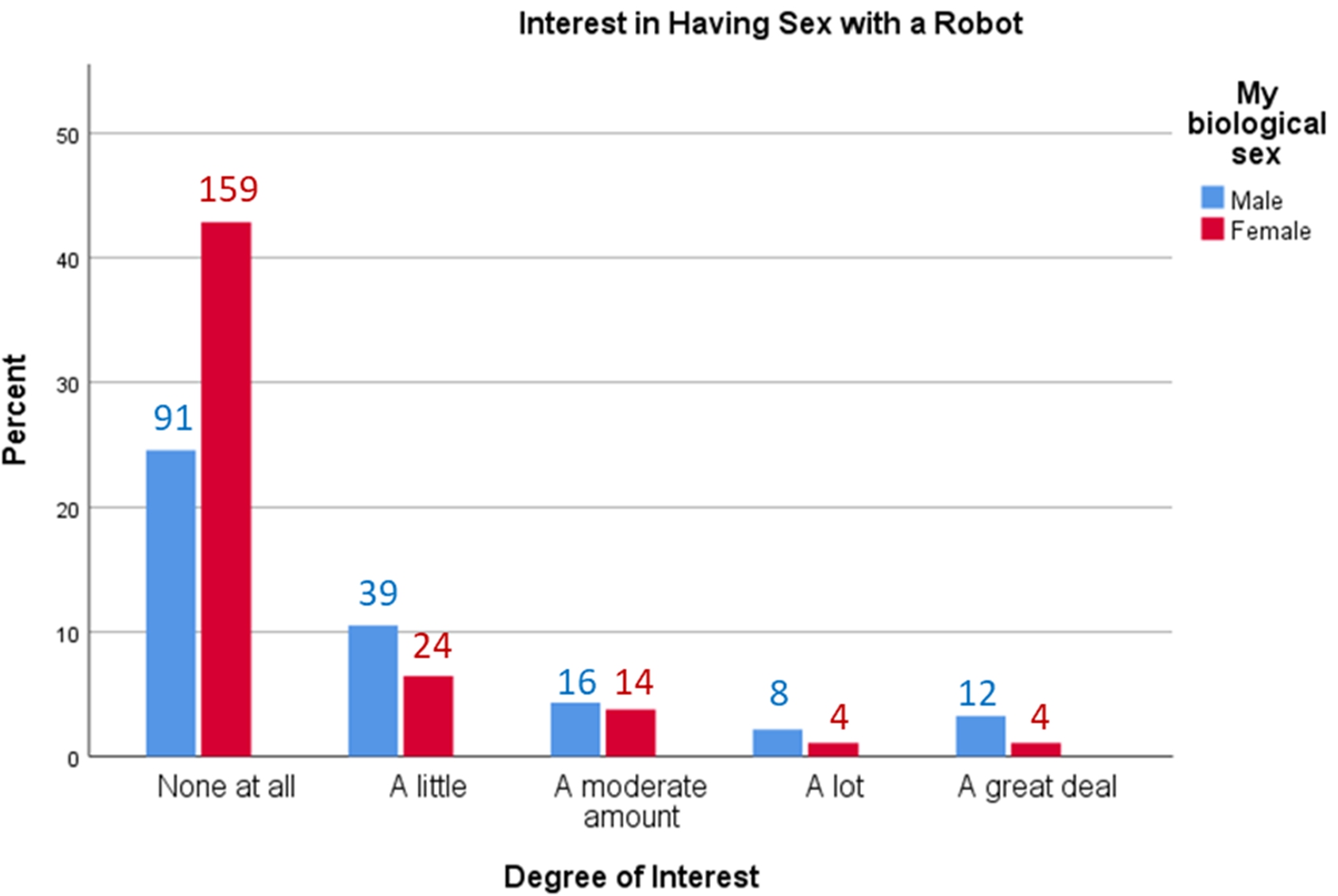

We hypothesized there would be sex differences in attitudes toward sex robots, with males generally reporting more positive attitudes regarding sex robots compared to females. Independent samples t-tests confirmed that males reported having a significantly greater interest in having sex with a robot (

Fig. 1.

Interest in having sex with a robot by sex (

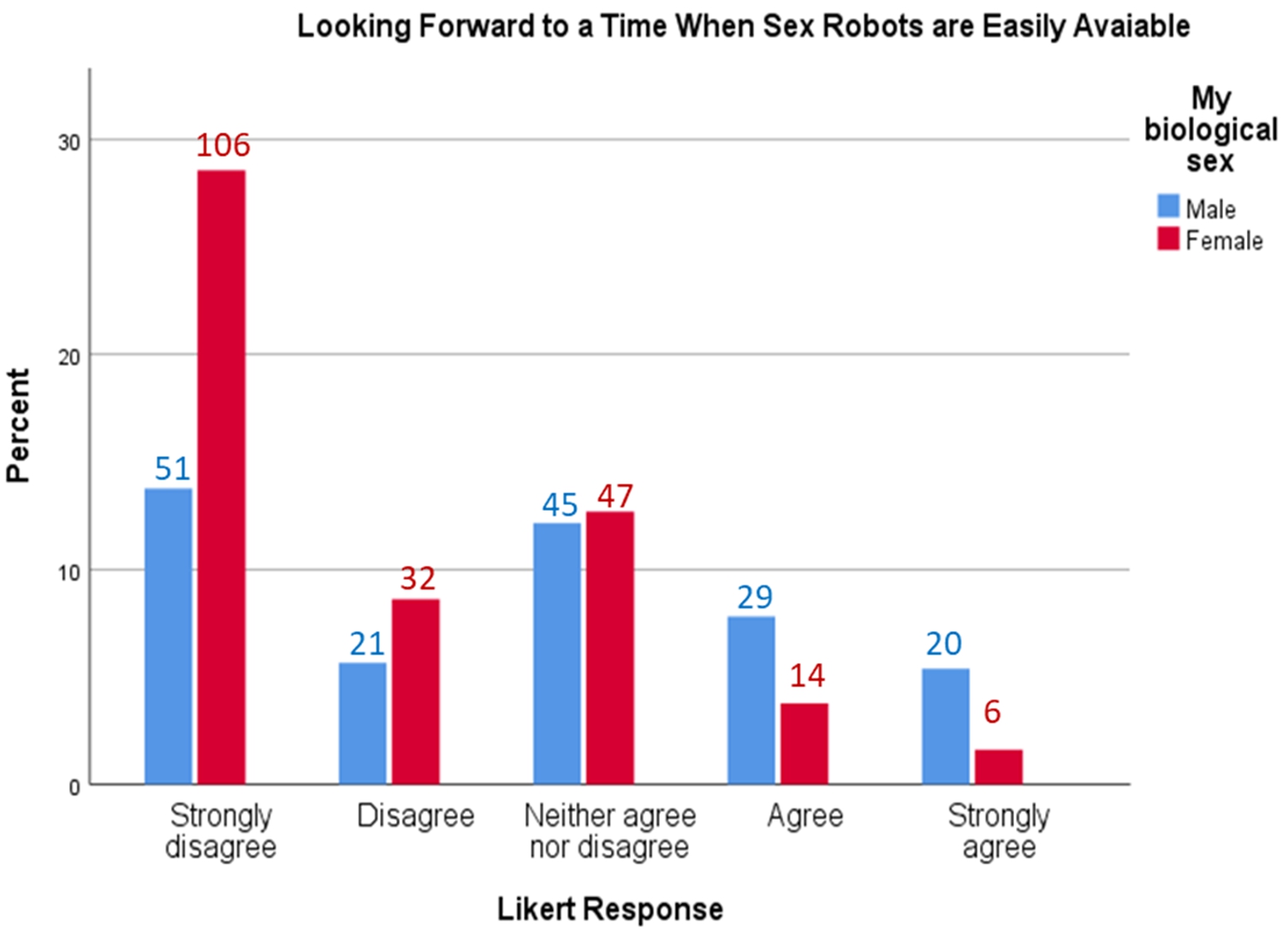

Fig. 2.

Looking forward to sex robot availability by sex (

3.3.2.Influence of age

Among men there were no significant differences in response to either question assessing attitudes toward sex robots based on age. Females significantly differed in the degree of interest in sex robots based on age (

Table 5

Correlations between attitudes towards sex robots and age by sex (

| Males ( | Females ( | |

| I have interest in having sex with a robot | −0.174∗ | −0.128 |

| ( | ( | |

| I look forward to a time when sex robots are easily available | −0.104 | −0.151∗ |

| ( | ( |

3.3.3.Influence of relationship status

Both males and females showed no differences in terms of their interest in having sex with sex robots based on relationship status,

3.3.4.Influence of psychological disorder diagnosis

A series of independent samples t-tests revealed that respondents who reported struggling with depression, social anxiety, attention deficit disorder, and/or Asperger’s spectrum disorder held more positive attitudes towards sex robots (see Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 6

Interest in having sex with a robot by psychological disorder

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Depression | 131 | 1.92 (1.29) | −3.77∗ | <0.001 |

| No depression | 240 | 1.43 (0.86) | ||

| Social anxiety | 140 | 1.87 (1.19) | −3.69∗ | <0.001 |

| No social anxiety | 231 | 1.44 (0.93) | ||

| Attention deficit disorder | 37 | 2.14 (1.58) | −2.23∗ | 0.031 |

| No attention deficit disorder | 334 | 1.54 (0.97) | ||

| Asperger’s spectrum | 12 | 3.42 (1.38) | −4.67∗ | 0.001 |

| No Asperger’s spectrum | 359 | 1.54 (0.99) |

Table 7

Looking forward to sex robot availability by psychological disorder

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Depression | 131 | 2.54 (1.38) | −3.04∗ | 0.003 |

| No Depression | 240 | 2.12 (1.24) | ||

| Social Anxiety | 140 | 2.59 (1.36) | −3.73∗ | <0.001 |

| No Social Anxiety | 231 | 2.07 (1.23) | ||

| Attention Deficit Disorder | 37 | 2.70 (1.58) | −1.80 | 0.079 |

| No Attention Deficit Disorder | 334 | 2.22 (1.26) | ||

| Asperger’s Spectrum | 12 | 4.00 (1.21) | −4.82∗ | <0.001 |

| No Asperger’s Spectrum | 359 | 1.54 (0.99) |

3.3.5.Influence of sexual orientation

Between-subject ANOVAs revealed significant differences in both interest in having sex with sex robots (

3.4.Attitudes towards sex robots and additional respondent characteristics

A series of bivariate correlations were conducted to identify relationships between attitudes towards sex robots and various items measuring relevant respondent characteristics. The results are displayed in Table 8. All correlations were statistically significant at the 0.05 level, with the exception of number of lifetime sex partners and looking forward to sex robot availability (

Table 8

Correlations between attitudes towards sex robots and respondent characteristics

| I have interest in having sex with a robot | I look forward to a time when sex robots are easily available | |

| Relationship style | 0.121∗ | −0.117∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Finds monogamy challenging | −0.340∗∗ | −0.309∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Sex drive | −0.198∗∗ | −0.194∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Lifetime sex partners | 0.129∗ | 0.081 |

| ( | ( | |

| Sexual fantasies | 0.384∗∗ | 0.331∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Masturbation | 0.422∗∗ | 0.351∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Pornography consumption | 0.492∗∗ | 0.406∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Alcohol | 0.222∗∗ | 0.191∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Marijuana | 0.353∗∗ | 0.307∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Prostitution approval | −0.329∗∗ | −0.414∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| Plays video games | 0.240∗∗ | 0.248∗∗ |

| ( | ( |

Note.

3.4.1.Influence of relationship style

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to elucidate the negative and positive significant correlations found between relationship style and attitudes towards sex robots. Respondents identified their relationship styles using a 6-point Likert scale, with 1 representing a preference to not be in a long-term relationship and 6 representing an overwhelming craving for emotional connection in relationships. Both ANOVAs were statistically significant for having interest in having sex with a robot,

3.4.2.Influence of perceptions of monogamy

Low scores on the monogamy variable indicate the respondent agrees that monogamy is challenging. Respondents who reported more positive attitudes toward sex robots tended to report finding monogamy challenging, as shown by the significant correlations in Table 8.

3.4.3.Influence of sex drive

Low scores on the sex drive survey item indicate a sex drive that is “far above average,” whereas high scores indicate the respondent’s self-reported sex drive is “far below average.” Similar negative correlations were found between both sex robot questions and sex drive, suggesting that respondents with higher sex drives reported more positive attitudes towards sex robots.

3.4.4.Influence of sexual fantasies, masturbation, porn, and video games

Based on the correlations reported in Table 8, those who have more sexual fantasies, masturbate frequently, consume porn frequently, and play video games frequently tend to have more interest in having sex with a robot and look forward to a time when sex robots are more easily available.

3.4.5.Influence of alcohol and marijuana

Additional weak but significant positive correlations also suggest that those who consume alcohol and marijuana tend to have more interest in having sex with a robot and look forward to sex robot availability more.

3.4.6.Influence of views on prostitution

The negative and significant correlations between the prostitution survey item and the questions assessing attitudes toward sex robots suggest that those who agree that prostitution is not wrong or inappropriate also tend to have more interest in having sex with a robot and look forward to sex robot availability.

3.5.Attitudes towards sex robots and respondent perceptions/feelings towards sex

An additional series of bivariate correlations were conducted to identify relationships between attitudes towards sex robots and items specifically assessing respondent’s perceptions and feeling surrounding sex. The results are displayed in Table 9, and then later discussed. All correlations were positive statistically significant at the 0.05 level except two analyses specific to looking forward to sex robot availability.

Respondents who report feeling comfortable communicating their needs in bed tend to report having a greater interest in having sex with a robot. Overall, feeling pressure to perform sexually, feeling your partner is attracted to you naked, feeling aroused by pleasing your partner, feeling it is difficult to initiate, and feeling concerned about being a satisfactory lover all correlated positively with positive attitudes towards sex robots. Finding it difficult to make eye contact during sex correlated with interest in sex robots, but not looking forward to their availability in the future. Lastly, the strongest correlations were between the adventurous sex survey item and the sex robot questions, suggesting respondents who find adventurous sex practices appealing (e.g., threesomes, BDSM) tend to hold more positive attitudes towards sex robots.

Table 9

Correlations between attitudes towards sex robots and respondent perceptions/feelings towards sex

| Question | I have interest in having sex with a robot | I look forward to a time when sex robots are easily available |

| I’m comfortable telling my partner what I really want in bed | 0.115∗ | 0.004 |

| ( | ( | |

| I feel pressure to perform sexually when I’m with a partner. For example, I often feel responsible for my partner’s pleasure | 0.222∗∗ | 0.241∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| I feel my partner would be attracted to my naked body | 0.184∗∗ | 0.149∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| I get aroused by pleasing my partner sexually | 0.207∗∗ | 0.149∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| It’s difficult for me to initiate sex because rejection is so uncomfortable | 0.273∗∗ | 0.249∗∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| I find it difficult to look in my partner’s eyes during sex | 0.141∗ | −0.086 |

| ( | ( | |

| I have concerns being a satisfactory lover | 0.169∗∗ | 0.104∗ |

| ( | ( | |

| I find adventurous sex practices appealing | 0.358∗∗ | 0.339∗∗ |

| ( | ( |

Note.

4.Discussion

Sex is a fundamental component of human intimate relationships, and sexual satisfaction correlates with relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction (Skałacka & Gerymski, 2019; Chao et al., 2011). For many couples, sexual intimacy is a critical aspect of their romantic relationship. On a socio-cultural level, our relationship to sex has changed dramatically in the last few decades, particularly in Westernized cultures. Laws supporting same sex marriage and sexual diversity are largely supported. Positive dialogue about all things sexual has increased in the media. Nonetheless, challenges remain. Research suggests that sexual frequency is on the decline (Ueda et al., 2020), and for at least some populations, sexual satisfaction appears to be decreasing (Burghardt et al., 2020). Against this ironic backdrop, sex robots may become the lovers of our future. While it is expected to be at least several decades before sex robots become more accessible to the general public (Muller & Bostrom, 2016), their impact may be dramatic for both individuals and couples. As such, exploring potential variables that may contribute to people’s positive and negative attitudes toward sex robots today may facilitate a more positive transition for this inevitable transformation in human intimate relationships.

Researchers have begun exploring possible variables impacting people’s attitudes toward sex robots. Males have been consistently found to exhibit more positive attitudes toward sex robots than females. This robust finding has led the speculation that people who engage in more sexual fantasies and enjoy more risky sex behaviors may hold more positive attitudes toward sex robots (Richards et al., 2017); as well as those holding more positive attitudes toward prostitution (Koverola et al., 2020; Richardson, 2016). This current survey seeks to gather further information about the emotional and behavioral characteristics of those with more positive attitudes toward sex robots.

Our research supports our past findings that while few people express a strong desire to have sex with a robot, males hold more positive attitudes about sex robots than females (Brandon et al., in press). In our sample, 45.2% of males showed at least some interest in having sex with a robot, as opposed to 22.4% of females. Similarly, 69.3% of males looked forward to a time when sex robots are available, in contrast to 48.3% of females. It does appear that the majority of female respondents have little interest in sex robots, now and in the future. Females with the most interest in sex robots were among the younger cohorts. In general, positive attitudes toward sex robots decrease with age for both men and women.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to correlate attitudes toward sex robots to a variety of emotional and behavioral data. We were surprised to find that every emotional, sexual, and behavioral variable we investigated correlated positively with attitudes toward sex robots. Some of these results were consistent with past research: people who fantasize more, engage in more risky sexual behavior, report greater intimacy fears, and have a higher sex drive have all expressed greater interest in having sex with a robot (Richards et al., 2017). Similarly, it has been suggested that people who hold more positive attitudes about prostitution may express more positive views about sex robots (Koverola et al., 2020; Richardson, 2016). However, many of our findings were novel and noteworthy. Specifically, self-reports of depression, social anxiety, attention deficit disorder, and Asperger’s spectrum all correlated with more positive attitudes toward sex robots. In addition, challenges with monogamy, more lifetime sex partners, higher frequency of masturbation, more pornography consumption, greater consumption of alcohol and marijuana, and more frequent use of video games all correlated with more positive attitudes toward sex robots. All questions exploring sexual pleasure shared with a partner correlated positively with attitudes toward sex robots, including being comfortable telling a partner what one likes in bed, feeling a partner would be attracted to one’s naked body, getting aroused by the concept of pleasing a partner sexually, and finding adventurous sex practices more appealing. Further, all questions exploring anxiety relating to sexual situations correlated positively with attitudes toward sex robots, including feeling pressure to perform sexually, finding initiation difficult because of the risk of rejection, finding it difficult to look in partner’s eyes during sex, and having concerns about being a satisfactory lover.

While the few numbers of individuals who identified as asexual prevented statistical analysis of this group, it was interesting to note that all five of our asexual respondents reported more interest in sex with robots than our heterosexual and bisexual respondents. This finding makes sense in light of the fact that folks who identify as asexual have been shown to enjoy and even prefer non-human sexual fantasies (Yule et al., 2017). How sexual orientation impacts attitudes toward sex robots is a worthwhile avenue for further study.

Some of our results surprised us. First, essentially half of our sample acknowledged struggling with one of the four mental health concerns we assessed, and that each of these disorders correlated with more positive attitudes toward sex robots. A Gallup poll assessing self-reported mental illness in 2020 revealed that approximately 34% of a United States sample experienced such challenges (Twenge & Joiner, 2020). As such, our sample seems to report more mental distress, although our survey questions likely measured different levels of distress than prior research. In addition, it seemed counter-intuitive that folks with depression reported more positive attitudes toward sex robots, in that depressed folks typically demonstrate less interest in sex (Kennedy and Rizvi, 2009). We were less surprised by the increased interest in folks with Asperger’s spectrum challenges, in that it has been speculated that such predispositions may correlate with more interest in sex dolls (Ciambrone et al., 2017). Folks with ADD have reported increased challenges with porn and hypersexuality (Boothe et al., 2019), so their more positive attitudes about sex robots could be understood from that perspective. Finally, folks with social anxiety report more fears of intimacy (Montesi et al., 2013). As has been speculated previously, is possible that people with intimacy fears will find sex robots less intimidating sex partners (Richards et al., 2017). Future research should evaluate and expand upon these possibilities.

Further, it wasn’t obvious to us that those who felt aroused by pleasing their partner would also demonstrate more positive attitudes toward sex robots. If pleasing one’s partner is an important aspect of sexual satisfaction, then it would seem to follow that sexually satisfying a robot would be less compelling than satisfying an actual human partner. Our interpretation of this finding is limited however, in that we were merely exploring attitudes toward sex robots, not a preference to a robot versus a human partner.

In sum, our data suggest that multiple emotional, sexual and behavioral variables contribute to positive attitudes toward sex robots. People who tend to experience sex more positively may hold more positive attitudes toward sex robots perhaps because they hold more positive attitudes toward sex in general. However, folks who tend to have emotional challenges or anxieties about sexual intimacy may also hold more positive attitudes toward sex robots, possibly because sex robots may be experienced as less intimidating than a human partner capable of judging or shaming them. As such, while diverse in their presentation, these groups likely find very different elements of sex with robots compelling.

Our results are subject to multiple limitations and must be interpreted accordingly. First, at the time of our data gathering, there was no validated questionnaire for assessing attitudes toward sex robots. As such, our questionnaire has not been statistically validated and reliability is uncertain. Second, data was gathered via crowdsourcing techniques. Such a self-selected sample limits the generalizability of our results. We can assume that many people would be uncomfortable answering questions online regarding such personal data as their sexual proclivities and anxieties, or their use of alcohol, and thus are not included in our analysis. In addition, self-report measures are subject to multiple limitations, and results are dependent on subjects’ self-awareness as well as their willingness to accurately reflect their experience. Confounding variables including cognitive bias, misinterpretation of questions, and malicious responding may be interfering with the validity of our findings. Finally, this research is based on speculation of people’s future experiences. It is impossible to foresee when and how advanced sex tech will unfold, as well as the cultural climate within which these changes will occur. As such, our conclusions today may prove inaccurate as the future of human intimacy unfolds.

As we anticipate the potentially profound impact that sex robots may have on human intimacy in both positive and negative ways, it is incumbent on researchers to develop a clearer awareness of the potential trials that await intimate relationships in the coming decades. The fact that the public remains relatively unaware of the upcoming challenges sex tech may offer intimate relationships only amplifies our professional responsibility. Because the public has yet to experience sex robots in a personal way, we have only their attitudes about sex robots at our disposal to explore currently. We call upon researchers to assist in further refining the vast array of emotional and behavioral variables that may correlate with attitudes toward sex robots.

5.Conclusion

In sum, our results were consistent with past findings that a majority of our study population acknowledged no interest in having sex with a robot, nor were they looking forward to a time when sex robots were easily available. Second, and consistent with past research, females held significantly more negative attitudes toward sex robots than males. Nonetheless, our research explored previously unexamined correlations between a variety of emotional, sexual, and behavioral variables as they related to attitudes toward sex robots. We found that all of the variables investigated correlated with more positive attitudes toward sex robots. It is our hope that future research will further our understanding of the multiple, complex variables influencing attitudes toward sex robots so that we may facilitate a smoother transition into the future of human intimate experience.

References

1 | Abdollahi, H., Mollahosseini, A., Lane, J.T. & Mahoor, M.H. ((2017) ). A pilot study on using an intelligent life-like robot as a companion for elderly individuals with dementia and depression. In 2017 IEEE-RAS 17th International Conference on Humanoid Robotics (Humanoids), Birmingham, UK (pp. 541–546). doi:10.1109/HUMANOIDS.2017.8246925. |

2 | Archer, J. ((2019) ). The reality and evolutionary significance of human psychological sex differences. Biological Review, 94: , 1381–1415. |

3 | Baumeister, R., Catanese, K. & Vohs, K. ((2001) ). Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5: , 242–273. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_5. |

4 | Boothe, B., Koos, M., Toth-Kiraly, I., Orosz, G. & Demetrovics, Z. ((2019) ). Investigating the associations of adult ADHD symptoms, hypersexuality, and problematic pornography use among men and women on a largescale, non-clinical sample. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16: (4), 489–499. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.01.312. |

5 | Brandon, M., Shlykova, N. & Morgentaler, A. and other attitudes towards sex robots: Results of an online survey. Journal of Future Robot Life. (in press). Curiosity. |

6 | Burghardt, J., Beutel, M., Hasenburg, A., Schmutzer, G. & Brahler ((2020) ). Declining sexual activity and desire in women: Findings from representative German surveys 2005 and 2016. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49: , 919–925. |

7 | Carroll, J., Busby, D., Willoughby, B. & Brown, C. ((2017) ). The porn gap: Differences in men’s and women’s pornography patterns in couple relationships. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 16: (2), 146–163. doi:10.1080/15332691.2016.1238796. |

8 | Chao, J.K., Lin, Y.C., Ma, M.C., Lai, C.J., Ku, Y.C., Kuo, W.H. & Chao, I.C. ((2011) ). Relationship among sexual desire, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life in middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 37: (5), 386–403. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2011.607051. |

9 | Ciambrone, D., Phua, V. & Avery, E. ((2017) ). Gendered synthetic love: Real dolls and the construction of intimacy. International Review of Modern Sociology, 43: , 59–78. |

10 | Cubbins, L. & Tanfer, K. ((2000) ). The influence of gender on sex: A study of men’s and women’s self-reported high-risk sex behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29: , 229–257. doi:10.1023/A:1001963413640. |

11 | Danaher, J., Earp, B. & Sandbert, A. ((2018) ). Should we campaign against sex robots? In J. Danaher and N. McArthur (Eds.), Robot Sex: Social and Ethical Implications (pp. 47–71). |

12 | Danaher, J. & McArthur, N. (Eds.) ((2017) ). Robot Sex: Social and Ethical Implications. Cambridge MA: MIT Press. |

13 | Dawson, S., Bannerman, B. & Lalumiere, M. ((2014) ). Paraphilic interests: An examination of sex differences in a non-clinical sample. Sexual Abuse, 28: , 20–45. doi:10.1177/1079063214525645. |

14 | De Vries, G. & Forger, N. (2015). Sex differences in the brain: A whole body perspective. Biology of Sex Differences, 6. doi:10.1186/s13293-015-0032-z. |

15 | Doring, N. & Poschl, S. ((2018) ). Sex toys, sex dolls, sex robots: Our under researched bed-fellows. Sexologies, 27: , 133–138. doi:10.1016/j.sexol.2018.05.003. |

16 | Doring, N., Rohangis Mohseni, M. & Walter, R. (2020). Design, use, and effects of sex dolls and sex robots: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(7). doi:10.2196/18551. |

17 | Dube, S. & Anctil, D. ((2020) ). Foundations of erobotics. International Journal of Social Robotics. doi:10.1007/s12369-020-00706-0. |

18 | Foundation for Responsible Robotics (2017). Our sexual future with robots. |

19 | Galaitsi, S.E., Ogilvie Hendren, C., Trump, B. & Linkov, I. (2019). Sex robots – A harbinger for emerging AI risk. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 29. doi:10.3389/frai.2019.00027. |

20 | Gonzales-Gonzales, C., Gil-Iranzo, R. & Paderewsky, P. ((2019) ). Sex with robots: Analyzing the gender and ethics approaches in design. In Interaccion ‘19: Proceedings of the XX International Conference on Human Computer Interaction. doi:10.1145/3335595.3335609. |

21 | Hammond, N. & van Hooff, J. ((2019) ). “This is me, this is what I am, I am a man”: The masculinities of men who pay for sex with women. The Journal of Sex Research, 57: (5), 650–663. doi:10.1080/00224499.2019.1644485. |

22 | Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Schick, V., Sanders, S., Dodge, B. & Fortenberry, J. ((2010) ). Sexual behavior in the United States: Results from a national probability sample of men and women age 14–94. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7: , 255–265. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. |

23 | Javaheri, A., Moghadamnejad, N., Keshavarz, H., Javaheri, E., Dobbins, C., Momeni-Ortner, E. & Rawassizadeh, R. ((2020) ). Public vs media opinion on robots and their evolution over recent years. CCF Transactions on Pervasive Computing and Interaction, 2: , 189–205. doi:10.1007/s42486-020-00035-1. |

24 | Jecker, N. ((2020) ). Nothing to be ashamed of: Sex robots for older adults with disabilities. Journal of Medical Ethics, 47: , 26–32. doi:10.1136/medethics-2020-106645. |

25 | Johnson, D. & Verdicchio, M. ((2020) ). Constructing the meaning of humanoid sex robots. International Journal of Social Robotics, 12: , 415–424. doi:10.1007/s12369-019-00586-z. |

26 | Kennedy, S. & Rizvi, S. ((2009) ). Sexual dysfunction, depression, and the impact of antidepressants. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29: (2), 157–164. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819c76e9. |

27 | Koverola, M., Dronsinou, M., Palomaki, J., Halonen, J., Kunnari, A., Repo, M., Lehtonen, N. & Laakasuo, M. ((2020) ). Moral psychology of sex robots: An experimental study – how pathogen disgust is associated with interhuman sex but not interandroid sex. Journal of Behavioral Robotics, 11: , 233–249. doi:10.1515/pjbr-2020-0012. |

28 | Levy, D. ((2007) ). Love & Sex with Robots. New York: HarperCollins. |

29 | Liberati, N. ((2020) ). Making out with the world and valuing relationships with humans. Journal of Behavioral Robotics, 11: , 140–146. doi:10.1515/pjbr-2020-0010. |

30 | McArthur, N. ((2017) ). The case for sexbots. In J. Danaher and N. McArthur (Eds.), Robot Sex: Social and Ethical Implications (pp. 31–46). Cambridge MA: MIT Press. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262036689.001.0001. |

31 | McBurney, D., Zapp, D. & Streeter, S. ((2005) ). Preferred number of sex partners: Tails of distributions and tales of mating systems. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26: , 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.09.005. |

32 | Meyers-Levy, J. & Loken, B. ((2015) ). Revisiting gender differences: What we know and what lies ahead. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25: (1), 129–149. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.06.003. |

33 | Montesi, J.L., Conner, B.T., Gordon, E.A., Fauger, R.L., Kim, K.H. & Heimberg, R.G. ((2013) ). On the relationship among social anxiety, intimacy, sexual communication, and sexual satisfaction in young couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42: , 81–91. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9929-3. |

34 | Muller, V. & Bostrom, N. ((2016) ). Future progress in artificial intelligence: A survey of expert opinion. In V.C. Muller (Ed.), Fundamental Issues of Artificial Intelligence, Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-26485-1. |

35 | Nomura, T., Kanda, T. & Suzuki, T. ((2006) ). Experimental investigation into influence of negative attitudes toward robots on human-robot interaction. AI & Society, 20: , 138–150. doi:10.1007/s00146-005-0012-7. |

36 | Nordmo, M. ((2020) ). Friends, lovers, or nothing: Men and women differ in their perceptions of sex robots and platonic love robots. Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00355. |

37 | Nyholm, S. & Frank, E. ((2019) ). It loves me, it loves me not: Is it morally problematic to design sex robots that appear to love their owner? Techne: Research in Philosophy and Technology, 23: (3), 402–424. |

38 | Oleksy, T. & Wnuk, A. (2021). Do women perceive sex robots as threatening? The role of political views and presenting the robot as a female-vs male-friendly product. Computers in Human Behavior, 117. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106664. |

39 | Richards, R., Coss, C. & Quinn, J. ((2017) ). Exploration of relationship factors and the likelihood of a sexual robotic experience. In A.D. Cheok, K. Devlin and D. Levy (Eds.), Love and Sex with Robots, Second International Conference, LSR 2016, London, UK, December 19–20, 2016 (pp. 97–103). London: Springer. |

40 | Richardson, K. (2016). The asymmetrical “relationship”: Parallels between prostitution and the development of sex robots. Presented at ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society. 10.1145/2874239.2874281. |

41 | Richardson, K. ((2019) ). The human relationship in the ethics of robotics: A call to Martin Buber’s I and Thou. AI & Society, 34: (1), 75–82. doi:10.1007/s00146-017-0699-2. |

42 | Scheutz, M. & Arnold, T. ((2016) ). Are we ready for sex robots? In Proceedings of the 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction (pp. 351–358). |

43 | Scheutz, M. & Arnold, T. ((2018) ). Intimacy, bonding, and sex robots: Examining empirical results and exploring ethical ramifications. In J. Danaher and N. McArthur (Eds.), Robot Sex: Social and Ethical Implications (pp. 247–260). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. |

44 | Schmitt, D., Shackelford, T., Duntley, J., Tooke, W. & Buss, D. ((2001) ). The desire for sexual variety as a key to understanding basic human mating strategies. Personal Relationships, 8: , 425–455. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2001.tb00049.x. |

45 | Skałacka, K. & Gerymski, R. ((2019) ). Sexual activity and life satisfaction in older adults. Psychogeriatrics, 19: (3), 195–201. doi:10.1111/psyg.12381. |

46 | Smith, A., Lyons, A., Ferris, J., Richters, J., Pitts, M., Shelly, J. & Simpson, J. ((2011) ). Sexual and relationship satisfaction among heterosexual men and women: The importance of desired frequency of sex. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 37: , 104–115. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2011.560531. |

47 | Szczuka, J. & Kramer, N. ((2018) ). Jealousy 4.0? An empirical study on jealousy-related discomfort of women evoked by other women and gynoid robots. Journal of Behavioral Robotics, 9: , 323–336. doi:10.1515/pjbr-2018-0023. |

48 | Tazhigaliyeva, N., Diyas, Y., Brakk, D., Aimambetov, Y. & Sandygulova, A. ((2016) ). Learning with or from the robot: Exploring robot roles in educational context with children. In A. Agah, J.J. Cabibihan, A. Howard, M. Salichs and H. He (Eds.), Social Robotics. ICSR 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 9979: ). Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47437-3_64. |

49 | Torjesen, I. ((2017) ). Society must consider the risks of sex robots, report warns. British Medical Journal, 358: , j3267. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3267. |

50 | Troiano, G., Wood, M. & Harteveld, C. ((2020) ). “And this, kids, is how I met your mother”: Consumerist, mundane, and uncanny features with sex robots. In CHI 2020, Honolulu, HI (pp. 25–30). |

51 | Twenge, J.M. & Joiner, T.E. ((2020) ). U.S. census bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic. Depression and Anxiety, 37: (10), 954–956. doi:10.1002/da.23077. |

52 | Ueda, P., Mercer, C., Ghaznavi, C. & Herbenick, D. (2020). Trends in frequency of sexual activity and number of sex partners among adults ages 18 to 44 years in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA Network Open, 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3833. |

53 | Wu, Y., Ku, L. & Zaroff, C. ((2016) ). Sexual arousal and sexual fantasy: The influence of gender, and the measurement of antecedents and emotional consequences in Macau and the United States. International Journal of Sexual Health, 28: , 55–69. doi:10.1080/19317611.2015.1111281. |

54 | Yule, M.A., Brotto, L.A. & Gorzalka, B.B. ((2017) ). Sexual fantasy and masturbation among asexual individuals: An in-depth exploration. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46: , 311–328. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0870-8. |