Facilitating intergenerational storytelling for older adults in the nursing home: A case study

Abstract

In this paper, we present our study regarding facilitating storytelling of older adults living in the nursing home with their children. The paper was driven by the following research questions: (1) What life stories would the older adults like to share? And (2) In which ways, could design enable the older adults to tell their stories? We designed a tangible device named Slots-Story, and conducted a preliminary evaluation to refine it. In the field study, eight pairs of participants (each pair consisted of an elderly adult and his/her child) were recruited to use the prototype for around ten days. Semi-structured interviews were conducted before and after the implementation. In total 344 stories were collected. Thematic, structural, and interaction analyses were conducted with the stories. In the discussion, we conclude the paper with design considerations for promoting older adults’ storytelling with their children.

1.Introduction

The aging society is coming. The worldwide population over age 65 is expected to more than the double of 357 million in 1990 to 761 million in 2025 [35]. Up to 50% of this group is over the age of 85 and likely to be placed in a nursing home at some point in their lives [56]. While there are benefits to living in an institutional setting, many new residents report a profound sense of loss [54]. They have limited involvement in social connections, and social isolation is a widespread problem [52]. Living separately from their children also makes it challenging to communicate with each other, because of different interests, stereotypes of aging, geographical distance, and the fast pace of contemporary life. Given that one precious characteristic of older adults is their memory of events, people, and places [21], intergenerational storytelling could act as an effective way to keep them in touch with their children. Intergenerational storytelling not only improves psychological well-being, reduces feelings of loneliness and depression of the elderly [19], but also contributes to the development of a strong sense of intergenerational self, which is associated with children’s increased resilience, better adjustment, and improved likelihood of overcoming challenges [26]. Preservation of the life stories is also significant because stories are an essential part of identity preservation. As a family story continues to be told across generations, the story becomes a legacy [63]. The elderly hope they will be remembered.

However, when the elderly pass, their family members are only left with bundles of images, materials, objects, and wishes of the deceased [71]. Recently, new practices on sharing personal content have emerged with the rapid growth of online sharing services. However, story sharing and preservation are still problematic for older adults, especially those living in a nursing home. First, despite that sitting together to communicate face-to-face is the most common and enjoyable way to share stories and mementos [46], a growing number of older adults move to the nursing home and live separately from their children. Video calls (e.g. Skype and iChat) help to a certain extent, but older adults and their children’s daily schedules are antisymmetric [65]. It also needs to be pre-scheduled and is less familiar to old adults [3]. Second, instant messenger applications (e.g. WhatsApp and Messenger) help to share the stories to some degree, but they are more about the current moments and less about the past moments [49], and they are multipurpose and are designed for smart-phone users. Our target group is the aged non-tech-savvy people. While younger seniors are embracing online social technologies, their parents, many of whom are still living, are neglected in this trend [5]. Internet and social media use drop significantly for people age 75 and older [73]; only 34% of the people in the G.I. Generation (born in 1936 or earlier) use the Internet [48]. Older adults are still disconnected from the mainstream social circles due to lack of technology and devices that resonate with them [69].

In this paper, we describe our explorative work, focusing on prompt older adults to share and preserve their life stories with their children. The research was conducted in a Research-through-Design manner. Based on our previous work, we first designed a research prototype, a tangible device facilitating life storytelling for older adults (Section 3). In the field study (Section 4), eight pairs of participants (each pair consisting of an older people and his/her child) were recruited to use it for about ten days. After that, semi-structured interviews were conducted with older adults and their children. Subsequently, stories were firstly transcribed, and thematic, structural, and interaction analysis were conducted. All the data forms the foundation of the insights on the research questions. One feature of our study is that we see life story sharing is a cooperation process that both the storytellers and listeners should actively involve, and we particularly investigate what roles could the young generation play in family storytelling. Their roles are highlighted in our study. They are not only the audiences of storyteller (the elderly), but also could be the memory trigger provider, and organizer of the digital collections. Next, we will start with an overview of the research background and related activities in the field.

2.Related work

2.1.Theoretical knowledge of life story sharing

2.1.1.Definition of life story

Storytelling plays a fundamental role in human communication. It is so common that we seem to be unware of it. From a hermeneutic point of view, human life is a process of story and narrative interpretation [72]. As Robert Atkinson put it: “Storytelling can serve an essential function in our lives. We often think in story form, speak in story form, and bring meaning to our lives through story” [4]. The definition of life story, according to Charlotte Linde, is almost synonymous with personal narrative; it consists of all the stories and associated discourse units, such as explanations and chronicles, and the connections between them, told by an individual during the course of his/her lifetime [45]. There is considerable variation in the definitions across different disciplines. In sociolinguistics, life story refers to brief, topically specific stories organized around characters, setting and plot [42]. In anthropology and social history, life story refers to an entire life history which is woven from the threads of interviews, observation, and documents [53]. In sociolinguistics, life story refers to brief, topically specific stories organized around characters, setting and plot [42]. In psychology and sociology, it encompasses long sections of talk – extended accounts of lives in context that develop over the course of single or multiple interviews [57].

Robert Atkinson sets forth a comprehensive definition of life story: Life story is the story a person chooses to tell about the life he/she has lived and what is remembered of it. A life story is the essence of what has happened to a person. It can cover the time from birth to the present or before and beyond [4]. It can be inferred from the above that life story is a broad concept.

2.1.2.Multiple functions of storytelling of the elderly

Storytelling of the elderly serves multiple functions. From a physiological perspective, reminiscing and sharing of life stories improve self-esteem, mood, well-being and enhances feelings of control and mastery over life as one ages. Research has also associated reminiscence with improving psychological well-being, reducing feelings of loneliness and depression, and helping older adults find meaning in their life [19]. Although stories are unscientific, and imprecise narratives of human thought, they help organize and integrate the neural networks of the brain [62]. Besides, as well-told stories contain emotions, thoughts, conflicts and resolutions, they are critical to brain development and learning [16]. From a social perspective, stories transmit cultural and individual traditions, values, and moral codes [40]. Stories told by the elderly create meaning beyond the individual and provide a sense of self through historical time and in relation to family members, and thus may facilitate positive identity [25]. It has been well recognized that telling life stories can also have a ‘recuperative role’ [28,58], for individuals, relationships and societies and therefore becomes a moral act [29]. Life stories allow us to bring together many layers of understandings about a person, about their culture, and about how they have created change in their lives [23]. From a broader perspective, stories told by the elderly are treasured intangible source of cultural heritage. When individuals regard that they approach to the end of their lives, they tend to document segments of their personal history and issues of generativity and knowledge transmission to younger generations are considered as significant to seniors [66]. Storytelling and preservation benefit to older adults so significantly, and this is one important motivation for us to conduct this research.

2.2.Practices of older adults’ story sharing

Jenny Waycott et al. investigate the role of digital content created by older adults in the nursing home, for the purpose of forging new relationships [69]. We build on the idea of “older adults acting as story content producers”, and extend it into intergenerational story sharing. We mainly focus on the related applications within (Human-Computer Interaction) HCI area, which is a multidisciplinary field of study focusing on the design of computer technology and, in particular, the interaction between humans (the users) and all forms of information technology design [1].

Intergenerational storytelling for older adults is the intersection between storytelling for older adults and intergenerational communication. One thing to note is, since people above the age of 65 years old are diverse regarding cognitive ability, they compromise a group that is considerably more diverse than people of the general (younger) population, and their level of technological mastery varies [34]. Therefore, they could be roughly divided into the non-tech-savvy and tech-savvy group. Our target group is older adults in the nursing home, according to our investigation, most of them are non-tech-savvy users [43].

2.2.1.Applications supporting story sharing for older adults

Since tangible user interface (TUI) has proved to be a great potential to improve older adults’ technology acceptance [61], applications for non-tech-savvy older adults mostly adopt this interface. There are applications improving their connections with other fellow residents: a system aiming to help residents in the nursing home make connections with each other through sharing stories [47], using landscape tangibles as proxy objects to aid reminiscence [6]. There are also applications improving their connections with people outside: a tangible installation aims to facilitate story sharing between older adults and citizens [44].

2.2.2.Applications supporting intergenerational communicating

There are applications designing for co-present sharing, for example, Cueb is an interactive digital photo cubes with which parents and teenagers can share experiences [32]. For the family members over a distance, a video system permitting sharing everyday life between multiple locations was designed [39]. There are studies enhancing communication within remote family members through sharing photos [8,54], there are also applications aiming to strengthen family connectivity through ambient awareness [14]. Another study explores how older adults’ favorite objects could be augmented to connect with adult children living remotely [10].

Particularly for intergenerational storytelling, related applications are mostly mobile applications used by the listeners – the young. For example, a mobile application supporting conversation between young people and older adults with dementia [70]. Similar applications include smartphone applications or webs for creating multimedia stories [20], a software of managing family stories [49], software for videos to be saved in user-specified real-world locations, shared with friends and family [7], and a software support digital reminiscing of the elderly [38], and a mobile application for reading and editing books, or even creating all new stories on an iPhone [20]. These applications typically could be used only when both the older adults and their children are present. For the applications specifically designing for non-tech-savvy users, there is a tangible device allowing sharing photos, tangible artefacts between grandparents and remote grandchildren (below the age of ten) [68].

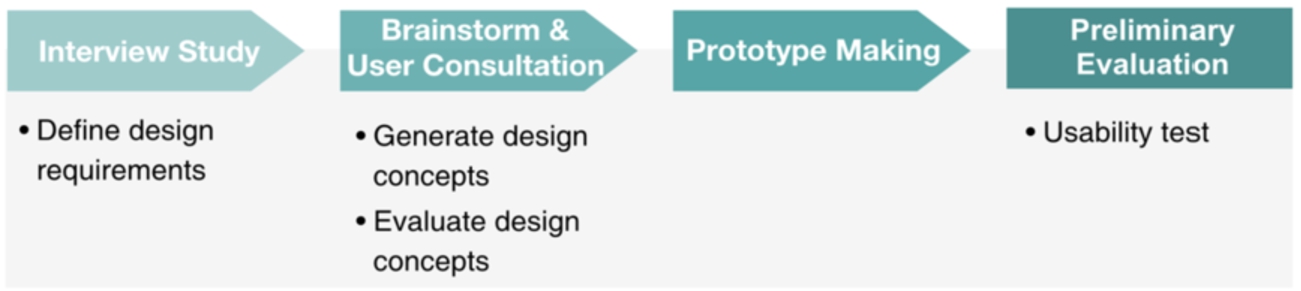

Fig. 1.

Design process of our research prototype.

2.3.Summary

Through retrieving the definition of life story from literature, we find the life story is a broad concept. From the perspective of practice, our study focuses on intergenerational life storytelling of older adults in nursing homes. Based on their two characteristics – living separately from their children, and most are non-tech-savvy users, we designed a tangible device to integrate memory triggers into their daily lives. Features of the study lies in two aspects. For the research prototype itself, we focus on older adults’ life stories, and we particularly adopt trigger questions as memory cues. We probe how to provide the older adults explicit memory trigger questions through a tangible device and bring them an enjoyable using experience. To make the non-tech-savvy older adults share and preserve life story independently, we also build on a tangible interface to bridge the technological gap for older users. While for the study, we see intergenerational story sharing as a cooperation process that both the storytellers and listeners should actively involve. Therefore, roles of the story listener – the young, are highlighted in our study: They are not only the audiences of storyteller (the elderly), but also could be the memory trigger provider, and organizer of the digital collections. In this paper, through the thematic analyzing of the stories collected by the prototype, we had a better understanding of older adults preference for life stories topics. And through the structural and interactional analysis, we had a better understanding of the characteristics of their storytelling. We finally break the intergenerational life story sharing into four steps: Trigger Process, Telling Process, Sharing Process, and Curating Process. Design considerations are proposed accordingly based on the findings gathered from the field study.

3.Design intervention

3.1.Prototype

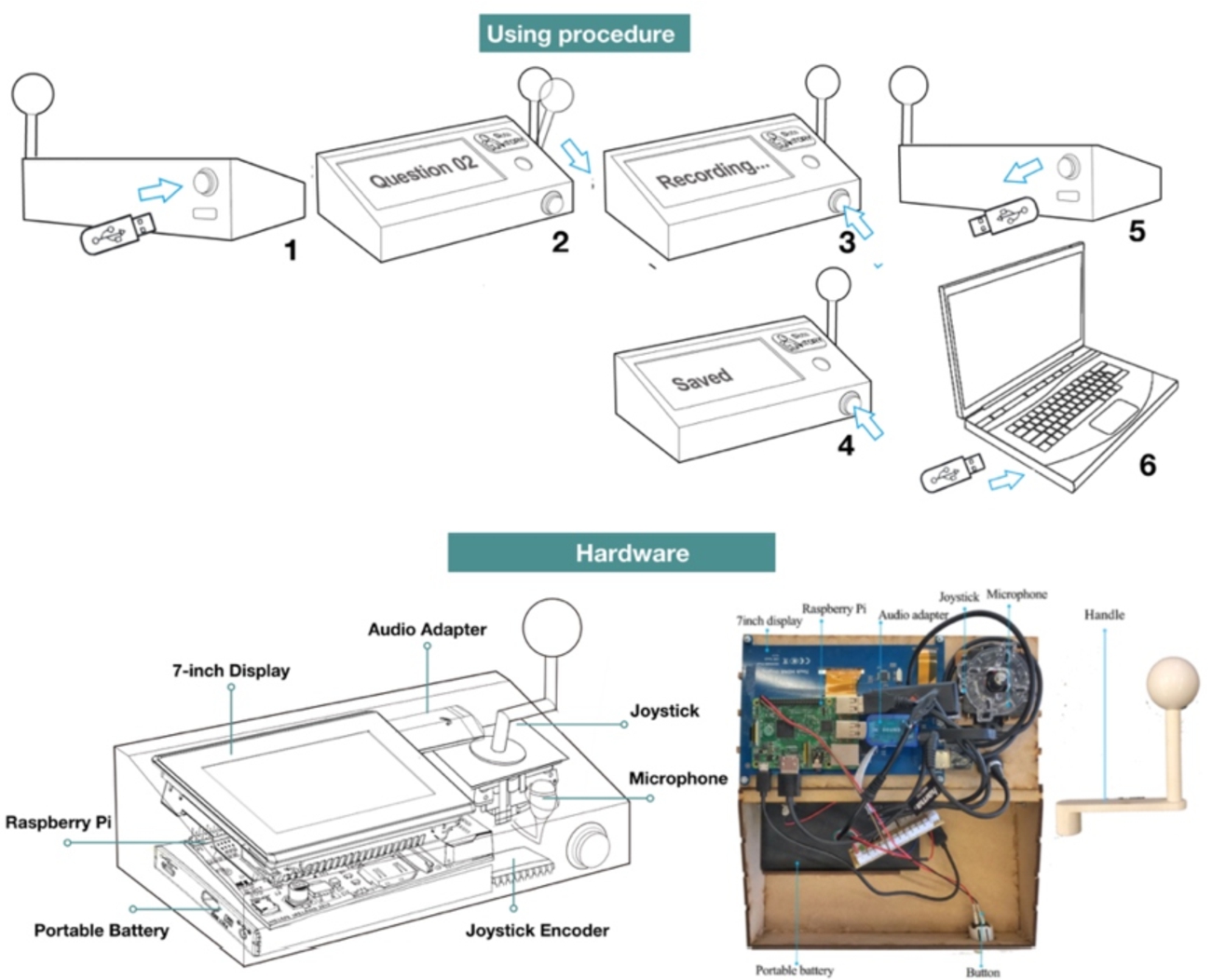

The research prototype is based on our previous work [43], and the design process is shown in Fig. 1. The initial prototype was further refined after preliminary evaluation. The prototype integrates functions of memory cue generator and story recording. Its operation draws inspiration from slots-machine: User could pull down/up the handle to switch trigger questions, and press the white button to record stories (Fig. 2). We aim to provide an intuitive, familiar, and enjoyable use experience for these non-tech-savvy users. Since their children visit them regularly, according to our contextual inquiry, our prototype could be used either face-to-face or separately.

3.1.1.Appearance and display interfaces

For ergonomic purpose, it is wedge-shaped, making the display easy to see, and lever and buttons easy to access. A 7-inch display and a microphone are arranged on the upside, and a button is on the front side. The lever is on the right side. The handle on the back, together with a compact dimension, makes it easy to carry (L = 22 cm, W = 11 cm). The main body is made of porcelain white acrylic, and part is covered with wood-grained paper, making it look slightly old-fashioned, which is in line with the aesthetic taste of older adults.

It includes two display interfaces: the “Question interface” and “Recording interface”. Vintage style is also applied in both the interface elements and fonts. Considering fading eyesight of the elderly, bold and massive fonts are used for the text. There are usage tips at the bottom: “Note: Press “REC/STOP button before/after recording.” The “Question interface” displays one specific question, which will be switched to Next/Previous question by pulling down/pushing up the lever, and it will be switched to “Recoding interface” if the REC/STOP button is pressed. In the “Recoding interface”, a dynamic recording icon and timer widget are placed to provide real-time feedback.

3.1.2.Hardware

The hardware consists of a Raspberry Pi, a 7-inch display, a joystick, lever, portable battery, microphone, audio adapter, and a button (Fig. 3). Raspberry Pi 2 Model B is chosen as the hardware platform, and Joystick USB Encoder board is the medium to connect Raspberry Pi and joystick. The lever is 3D printed which could fit into the joystick component. Assembly of microphone and sound-card provides audio input, and the LCD Screen is graphical output. The prototype is powered by a power bank.

Fig. 2.

Initial prototype: USB flash disk, preliminary evaluation, refined prototype and interfaces.

Fig. 3.

Use procedure and hardware of prototype.

3.1.3.Interaction

The interaction process with Slots-Story (Fig. 3):

– Insert the flash disk into the prototype.

– The older adult pulls down/pushes up the lever to switch trigger questions.

– Press the button to start recording.

– Press the button again to save the recording.

– Stories told by the older adult now are in the flash disk.

– The young Plugs the flash disk into a computer to listen and keep stories, and further modify trigger questions.

– The Slots-Story could also be used face-to-face.

3.1.4.USB flash disk

We initially attempted to make the recording transmission wireless. However, audio files (by default were 320 kbps) recorded by Raspberry Pi were too large to make the sending process stable. We then adopted a compromise proposal: using a flash disk as a data mediation to store the trigger questions and audios.

3.1.5.Trigger questions of different themes

Most of the trigger questions were from The Life Story Interview [4], which cover most aspects of an entire life course, themes such as birth and family of origin, culture setting, and traditions, education, love and work, etc. Compared with other types of memory cues, questions are more explicit and straightforward, and targeted answers will be triggered. The young participants could choose what they were interested in and add customized questions. In order to avoid making old people think of negative memories, we encourage them to choose positive and neutral attitude trigger questions. Example trigger questions are as follows: Childhood: 1. Were you ever told anything unusual about your birth? 2. What is your earliest memory? 4. What clubs, groups, or organizations did you join? … Family: 1. What was going on in your family, your community, and the world at the time of your birth? 2. What beliefs or ideals your parents tried to teach you? … School and work: 1. What is your first memory of attending school? 2. What was your first experience of leaving home like?…

3.2.Usage scenarios

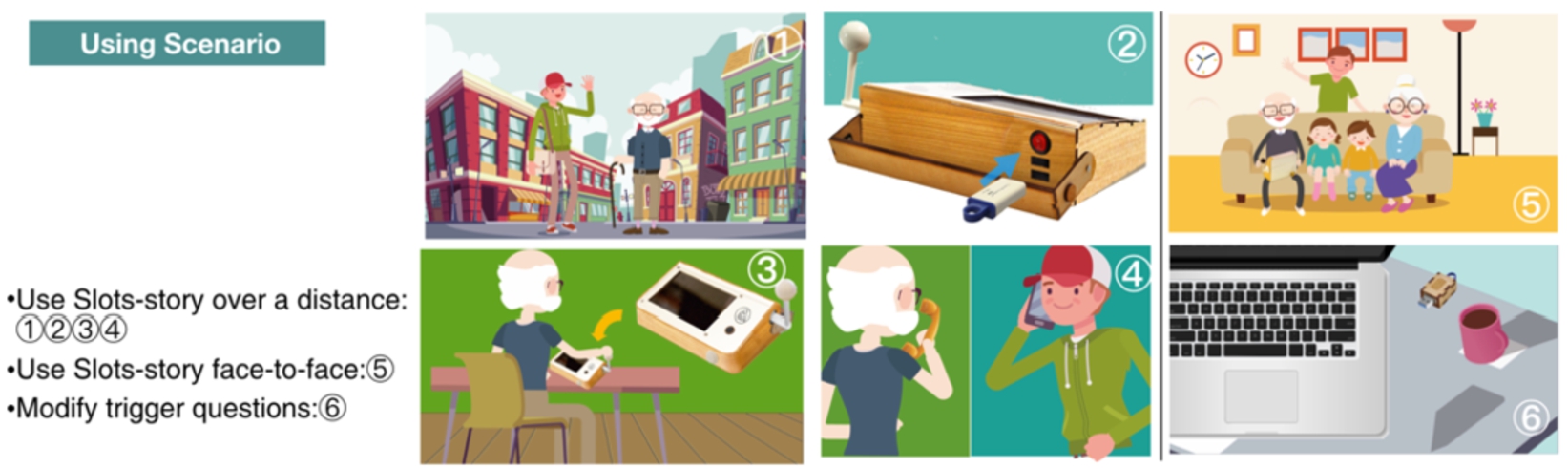

David grows old and lives alone. Someday his son gives him Slots-Story, and he soon masters functions of it after his son’s short instruction (Fig. 4).

3.2.1.Use Slots-Story separately

David operates the lever to select questions that he is interested in. David’s son gets the flash disk and plugs it into a computer to listen to the recordings. With great interests, his son wants to know more details of the question “What is your earliest memory?” His son then calls David: “Hey Dad, I listened to your story about your earliest memory, and I am very interested and want to know more about my grandmother at that time.” David then tells more details of that story, and his son feels knowing more about his father and grandmother.

3.2.2.Use Slots-Story face-to-face

Every weekend David’s son and his grandson visit him, which is the happiest moment for him. David’s grandson likes him because his grandson could always hear lots of stories from him. With the trigger questions provided by Slots-Story, the whole family get together and listen to stories from David.

Fig. 4.

Usage scenarios.

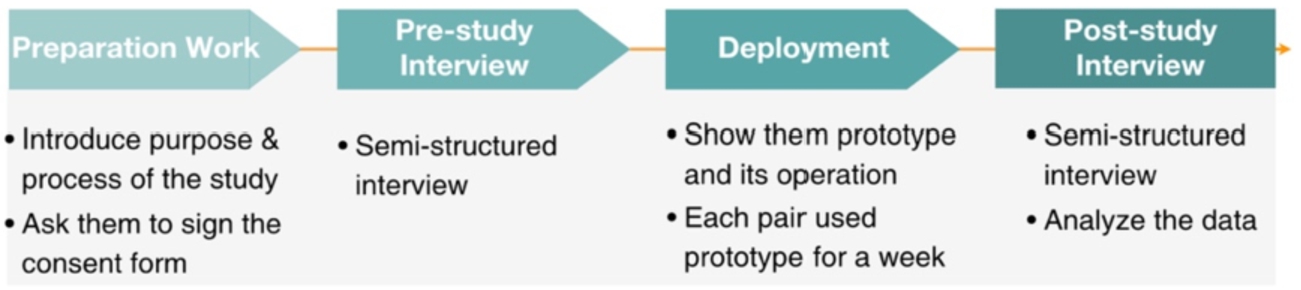

Fig. 5.

Field study procedure.

4.Implementation

4.1.Field study

4.1.1.Procedure, method, and participants

Three same prototypes were made, and each one was provided with a paper instruction for use. We recruited eight pairs of participants (each pair consisted of an old adult and his/her children). The older adults were from a Dutch nursing home, and they were recruited by the recommendations of the caregivers. None of them reported any significant physical impairments. All of them would like to share the stories with us on an anonymous basis, with a formal consent form. Detailed procedure is shown in Fig. 5: Purpose, functions, and operation procedure were introduced to them, and each pair used the prototype for around ten days, with semi-structured interviews at the start and end of this period. Each interview was audio-recorded. All names and data reported in this paper have been anonymized, and we restricted access to the data to our research team only. We also made small edits in part of the quotes for clarity. Grounded theory techniques [15] were adopted to analyze the data, to allow themes to emerge from them in a bottom-up manner.

4.1.2.Pre-study and post-study interview

The pre-study interview aimed to gain a better understanding of the status quo of their life storytelling, and the following topics were discussed: basic demographic information (age, gender, physical condition. Familiarity with technology), communication habits with family members, (Who, number, frequency, duration of contacting with family. The way of keeping in touch (face-to-face, phone, skype, etc.). Activities and talking topics when getting together, and familiarity with technology.) the current story sharing situation (Whether like to share stories, why. Situations and reasons for sharing life stories. Topics, duration, and frequency of story sharing. Triggers of life story sharing. Problems encountering during story sharing).

After using the prototype, we conducted the second round of interview, asking them to reflect on their use of Slots-Story to share stories. We explored the following topics with the older adults: Validity (Do you think it could facilitate sharing stories, and why? Would you like to use it?) Content (Preference of questions provided: A. Childhood B. Family C. School & Work D. Friend & Fun E. Historical Events G. Others) Appearance (What kind of appearance style would you prefer: A. Vintage B. High-tech C. Colorful/Lovely D. Simple) Interaction (Do you understand the concept of it? Do you find it easy to use? What is the most difficult part?) Comments for improvements (Which part do you like/dislike most of the prototype? why?) Open questions (Would you like to use it face to face/over a distance? Other comments). We interviewed their children based on the following questions: What’s your feeling after listening to the stories? Did you contact your parents after listening to the stories? Preference of stories: A. Childhood B. Family C. School and Work D. Friend and Fun E. Historical Events G. Others Comments for improvements) The following are the findings.

4.2.Findings of pre-study: Current life storytelling

4.2.1.Basic information and familiarity with technology

Most interviewees suffered from physical declines, such as vision and hearing loss, loss in sensitivity, flexibility, and mobility (some used rolling walkers), which had a passive influence on their daily lives: “Now two things influence my life, bad mobility, and bad eyesight.” Regarding familiarity with technology, apart from the youngest elderly participant (F, age = 73) had an iPad and used it to browse news, watch videos, and play simple games, the rest didn’t use computers or smartphones. They obtained outside information mainly by watching TV and reading Newspapers. Therefore, they still relied heavily on traditional objects and preferred physical operation. Lack of using experiences and physical decline lead to this situation.

4.2.2.Communication pattern with family members

Elderly participants had regular contact with their children, but they wanted more. The connection with their friends of the same age, sisters/brothers was less as they were also aged and even passed away: “I have one sister and one brother, but contact with them less because they are dying. I am old and couldn’t take a train or drive to visit them.” Except for one interviewee, they all had more than one child, who visited them regularly (from once a week to once a month), and the duration of each visit lasted 3–5 hours. They also connected by telephone, but they called their children only when in special and urgent circumstances (festivals, diseases, etc.): “I don’t call my children very often because I don’t want to disturb them. They have to work after all.” The elderly enjoyed the family union: “When they visit me, sometimes we have dinner together. It is the coziest moment, and I like that.” Although they felt they had regular connections, they wanted more, and their children’s busy work hindered it: “I hope they could visit me more often, but they are too busy.” Regarding activities and talking topics. When getting together with family, they usually had dinner together, did grocery, and drove out. They preferred to stay in their own apartments rather than the public space of the nursing home. Talking topics were various: daily lives, sports, weather, politics, etc., but mainly were related to family, which were private and personal.

4.2.3.Current life story sharing situation

First, nostalgia was prevalent among them. The elderly became emotional and depressed, and would like to recall the past: “I do not know. I am often easily emotional. For example, when I see one little girl ride bicycles, she is very friendly and nice. she reminds me of when I was young, I was a girl.” Reasons are as follows. First, they could not do some things they could before, making them easy to be frustrated: “When I encounter a problem, I first try to solve it by myself. But now I need care services, and that’s why moved here.” Second, people tended to be nostalgic naturally when they grew old, as one said: “Past things come to my minds somehow. I often look back to my life and feel life is short. Maybe you couldn’t understand unless you really grow old.” Another said: “I don’t understand the society of today. I miss the past. Recalling the past is like watching a movie.”

Second, the elderly would like to share life stories, but their children seemed to lack awareness of listening and preserving the elderly’s stories. Older adults would like to reflect on their past, but they were not asked specifically, nor did they have many chances to tell. They hoped their children would ask them more: “There is no doubt that I’d like to tell my past things to my children if they ask me, but I won’t force them to listen.” “I rarely initiated the storytelling. It was only when they asked, would I tell my past.” According to their children, all showed interests in their parents/grandparents’ past, but usually they just didn’t realize the importance of the stories. “It was only when my father passed away that I realized I didn’t know too much about him. At his funeral, I tried to recall him, but I found I knew his life little.” “When we were young, we were rarely interested in our parents’ past, but when we grew up and experienced more, we began to want to know more about our parents’ past.” They all agreed that listening and preserving the elderly’s life stories were important. Therefore, they felt a sense of guilt for not paying attention to it.

Third, situations and reasons for older adults’ story sharing. The older adults didn’t share life stories specifically and deliberately in daily lives, and their life story sharing was fragmented and happened unconsciously. Since it happened informally, casually, and unnoticeable, this made the stories hard to preserve. Situations and reasons could be summarized as follows. First, when chat topics were related to their past, acting as memory triggers to tell past: “Someone said his past things, or the talking topics just reminded me about my past, then I would like to tell my stories.” Second, when someone asked the older adults about their past specifically: “Children are curious about how it all went before, because life now is very different, and they sometimes asked me about that.” Third, older adults sometimes needed to talk with someone, as an outlet for their painful memories. Fourth, when the family was getting together to view family albums, photos also acted as memory cues. Other situations included meeting friends hadn’t seen for a long time, and one interviewee used to use a tape recorder to record stories for his grandson, and another one who was a Christian sometimes talked about her life experiences when explaining the bible. All the above situations happened occasionally.

Fourth, children were whom the elderly would like to tell stories to, and they hoped they could be remembered. First, although the interviewees lived together with fellow residents in the nursing home, their connections were mostly superficial. Second, although some lived with a spouse, they felt no necessity to share life stories with each other: “My wife and I know each other too much, and I don’t think it is necessary to tell my past to her again.” Overall, they preferred to share with their children: “I hope my children could understand my life by telling my stories to them.” The reason, perhaps was because they wanted to be remembered. For example, one elderly participant had made a brief biographical note, in case their children wanted to know him when he passed away. Another had filmed a video to document his life: “I recorded a DVD to tell my life. So, when I pass away, my children don’t have to do anything, and they just need to play it, that’s all.”

Fifth, problems encountered when sharing life stories. First, as some felt their lives were ordinary, their first concern was their stories were unappealing to others. One said: “I suppose those successful or rich people would like to tell their life stories. The celebrities publish their biography to express their thoughts, convey experience, and record history. For us ordinary people, there is nothing worth telling.” Second, the lack of storytelling topics. “We rarely talk specifically about the past, because we usually talk about what happens now.” Third, the limited visiting duration: “Visiting time is short, so we don’t have too much time to talk about the past specifically.” Fourth, some interviewees were emotional, and they might weep when recalling, and they felt it was embarrassing.

4.2.4.Summary of pre-study interview

The elderly didn’t share life stories, specifically and deliberately in their daily lives. Life story sharing was fragmented and happened informally, which made the stories hard to preserve. The elderly would like to share their life stories, but they were rarely explicitly asked. They had regular contact with their children, who visited them weekly. And this provided the potential for us to focus on intergenerational storytelling. Their intergenerational talking topics were mainly about family, which was private and personal. Memory triggers were necessary to facilitate life storytelling. Currently, their life memories were recalled by conversation topics, family mementoes, etc. Given that the meeting time of the young and the elderly was limited every week, we could also consider separating the process of storytelling and story listening.

4.3.Findings of post-study interview

4.3.1.Interview with the elderly

Validity of Slots-Story: Their feelings and opinions Most thought it could facilitate life storytelling. One said: “No one has ever asked me so many questions like this machine. It encourages me to sit together with my children to tell stories.” It helped them to remember what they almost forgot, reflect their life again, and provided an easy way to record the memories: “The explicit questions make it easy to remember the long-forgotten things, and some questions are what you might not think of yourself, they are good prompts.” They also enjoyed and benefited from the recalling: “I had a lot of fun when telling my own memories, experiences and feelings.” One reason was they could get insights from looking back to the past: “The recalling gave me insights into the past, mistakes I made, and reactions of people who are very close to me.”

Appearance and interaction of Slots-Story Although their preferences for the appearance styles varied, they all thought appearance should be unobtrusive when putting it at home. Therefore, decorative effects should be highlighted: “Options in the questionnaires are electronic products and look like radios, I think I have enough house appliances in my home, and I don’t want another one.” “Since you are making an intergenerational communication tool, you should make it a sense of family.” Most preferred vintage style, since it indicated the past, and brought a sense of mysteriousness. Regarding the interaction, most interviewees showed great interests, especially its intuitive operation of the lever. The metaphor of slots-machine was understood and accepted by them. Trigger questions and the lever operation were the most interesting functions for them: “The slots-machine-like operation raises me a sense of expecting and curiosity for the unknown.” Also, they appreciated the accessibility of voice-based preservation: direct storytelling behavior was convenient compared with writing. Especially for those who had difficulty in writing: “Without good eyesight, you cannot do much alone, even if you are mentally totally fit.” One unexpected finding was they appreciated the Flash disk as a tangible carrier to preserve their memories.

Comments for improvements The comments were mainly related to usability aspects. First, some participants complained it always displayed the same question after startup. It should be able to memorize the question displayed last time automatically. Second, the sensitivity of operation should be reduced, as their hands were clumsy. Third, one participant thought it could be more friendly by displaying “Thanks for your story” after telling stories. Fourth, by default, it should display the questions as a slideshow, so as to attract their attention, and encourage them to use.

Others As mentioned earlier, we tried to avoid negative trigger questions. However, some elderly participants found Slots-Story a tool to vent their negative emotions and frustrations. They had some memories that they couldn’t let go, while Slots-Story provided an outlet and unburdening for them: “I felt it is a total stranger that I could feel free to say anything to it.” They suggested the trigger questions could be comprehensive, including both positive, neutral, and negative topics. Although they knew their children were their story listeners, some of the older participants argued that when they used the prototype, they felt as if they were telling to strangers, and they felt at ease: “I feel like a broadcaster, and I’m telling strangers about my life journey.” They also would like to share their stories with strangers on an anonymous basis.

4.3.2.Interview with the older adults’ children

Validity: Their feelings and opinions First, not only did they know new things they didn’t know before, but also they felt closer to the elderly. Some said they learned completely new things, and they were surprised that there were lots of things they didn’t know before: “In the audio, my mother talked the origin of her nickname.” “I didn’t know too much about my great grandfather because he had passed away before I was born. I heard a lot about him through my mother’s recordings.” After review the elderly’s life, the young had reverence for the elderly: “I thought she is great, and her achievements are admirable.” It had a positive effect on intergenerational relationships, besides simply facilitating storytelling. Second, they felt the prototype could develop intergenerational conversations when using face-to-face, as one said: “It helps to develop conversations, and I think the trigger questions have been thought of for me, in case I didn’t ask my father.” Another said: “It can serve as a conduit for discussion, and one gets to know my grandparents differently.” Third, they attached importance to the story preservation in the long run, they felt recordings were not only valuable memories worth cherishing, but also could be a consolation if the elderly passed away: “If mom once died, these recordings with many heartfelt memories can certainly give me a little consolation. They could be something to give me comfort when she is gone, and I will treasure it forever. “They are valuable memory, and it will be eternal memory for me.” The recordings are also a treasure to pass on to the next generation, as the recordings were like biography encapsulating the storyteller’s life: “Our parents are guardians of a very personal memory treasure, which need to be preserved. I think that is the meaning of the prototype.” Another said: “I can play the recording to the next generation and talk about how it was with her grandmother back then, great idea for recording memories to be handed down the generations”. “It’s something you leave your children behind after death when they cannot ask for details anymore.” Fourth, they felt familiarity and emotion in the audios: “The voice is so familiar, and she is telling her own story, the things she has been going through.” “The recordings really brought me back heart-touching memories.” The background sound in the audios also made the young could imagine the scene of the elderly telling stories: “I even hear the meow of her cat. I could imagine the scene when she told her stories.” They appreciated that the prototype could preserve the elderly’s voice: “I ever made a short video consisting of photos, to honor my father, who has passed. I had photos and added background music to the video, but I don’t have my father’s real voices.” Fifth, some find it a good way to ask some embarrassing questions, as listening to the recordings was different from talking face to face. The prototype provided a way for avoiding awkward situations, when it came to embarrassing topics: “My dad is a serious man, and never tells me about his love experience. Using this tool makes him tell me indirectly.” Finally, our project together with the prototype enabled the young to be aware of the importance of intergenerational storytelling and preservation. As one said: “The stories are right there, we just need to dig them out.” More importantly, the project made them are aware of the urgency to listen and preserve the elderly’s lives, as they found there were some memories that the elderly couldn’t remember. Therefore, the sooner they tell their stories, the more they could remember: “When we were young, we might be not interested in stories of parents. But later, when we would like to ask them, they may already pass away, and we couldn’t ask anything longer. I will keep all these memories well and will learn much more.”

The young participants frankly mentioned that not all the stories aroused their interests. They had different reactions to different themes. Some were appealing to them, while for those were boring and uninteresting for them, they choose to fast forward, or even skip. Also, the large number of audios and photos increase the cost for organization and curation, and made it hard for subsequent retrieval. Even so, their attitudes towards the preserving were conservative, they preferred to keep them all. The first motivation was they preserved for the future, and even for the next generation.

The young generation’s preference for story topics Their preference for story topics was various. Some were interested in stories related to the war: “I learned WWII from the book, but I want to know some real stories.” Some were interested in their family members: “I never saw my grandfather, because when I was born, he had passed away. I am interested in stories about him.” Some were interested in the lifestyle of the past, as it was different from today, and some were interested in the things before they could remember.

Comments for improvements Some suggested that a cellphone application could be designed for them, together with the prototype, making them a complete system.

4.3.3.Summary of the post-study interview

For the elderly, most of them provided positive feedback on the prototype, and they especially appreciated the voice-based story preservation. Two unexpected findings include they recognized the Flash disk as a tangible carrier to preserve their memories, and some elderly participants found Slots-Story a tool to vent their negative emotions. Comments for improvements of the elderly mainly focus on the usability aspects. While for their children, their opinions could be summarized as, know new things of the elderly, developing intergenerational conversations when using face-to-face, they felt familiarity and emotion in the audios, and a good way to ask some embarrassing questions. Since not all the stories aroused their interests, and their preferences for story topics were various, it reminded us to avoid aimless story capture.

5.Analysis of stories

5.1.Quantitative data

5.1.1.Overview of stories collected by Slots-Story

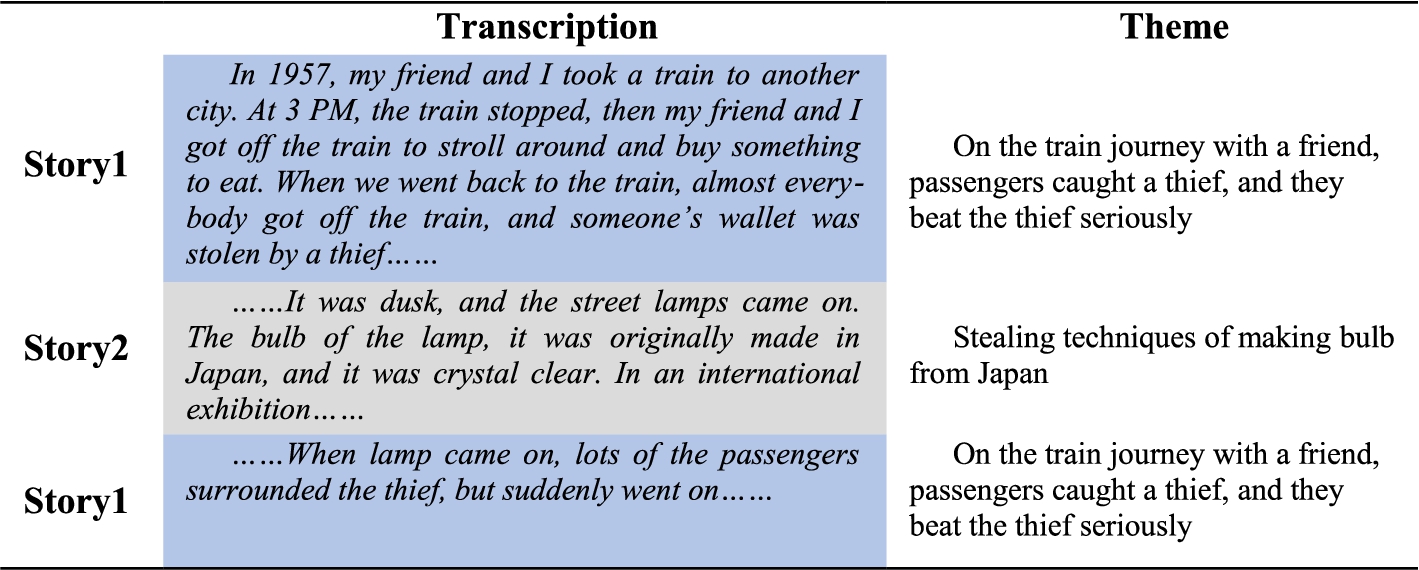

There existed some audios, such as: “I don’t remember.” “I don’t want to talk about it.” “I don’t know.” “Yes, I think I make friends easily.” After all these kinds were eliminated, totally 344 valid stories were collected. The Table 1 shows the overall results of the stories. Transcription conventions and guidelines were based on Robert Miller’s transcription guideline [51]. Stories were analyzed from three dimensions: thematic, structural, and interactional analysis. The thematic analysis emphasizes the content. The structural analysis focuses on the way stories are told. The interactional analysis emphasizes on the dialogic process between teller and listener.

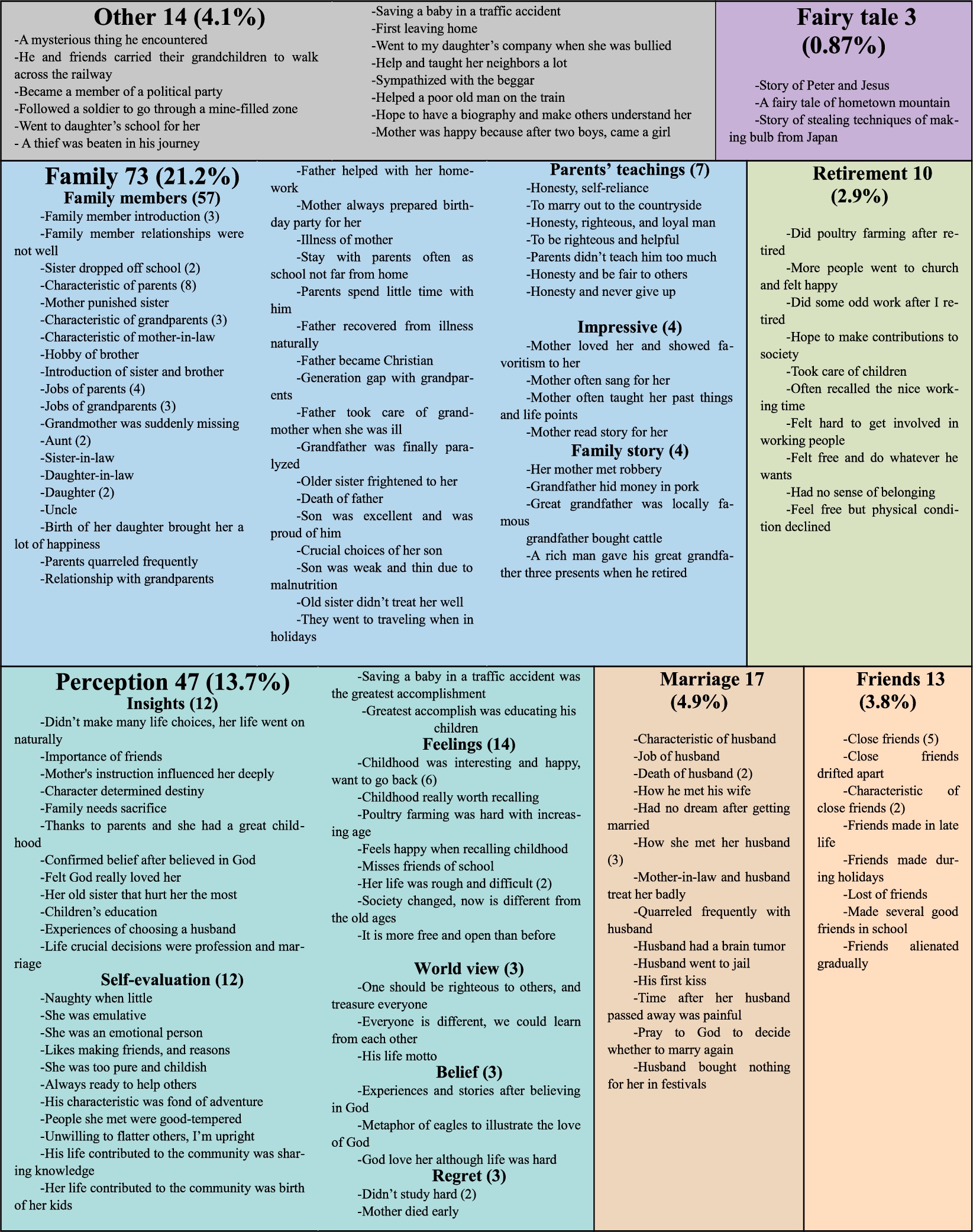

5.1.2.Using frequency of the prototype

Although we did not have too much findings from their using frequency (Fig. 6), we found there was a novel effect during their using Slots-Story for most users. Except or P6 and P4, whose using frequency was almost average, for the rest participants, there were peaks during their using. These peaks happened during their children visiting them.

Table 1

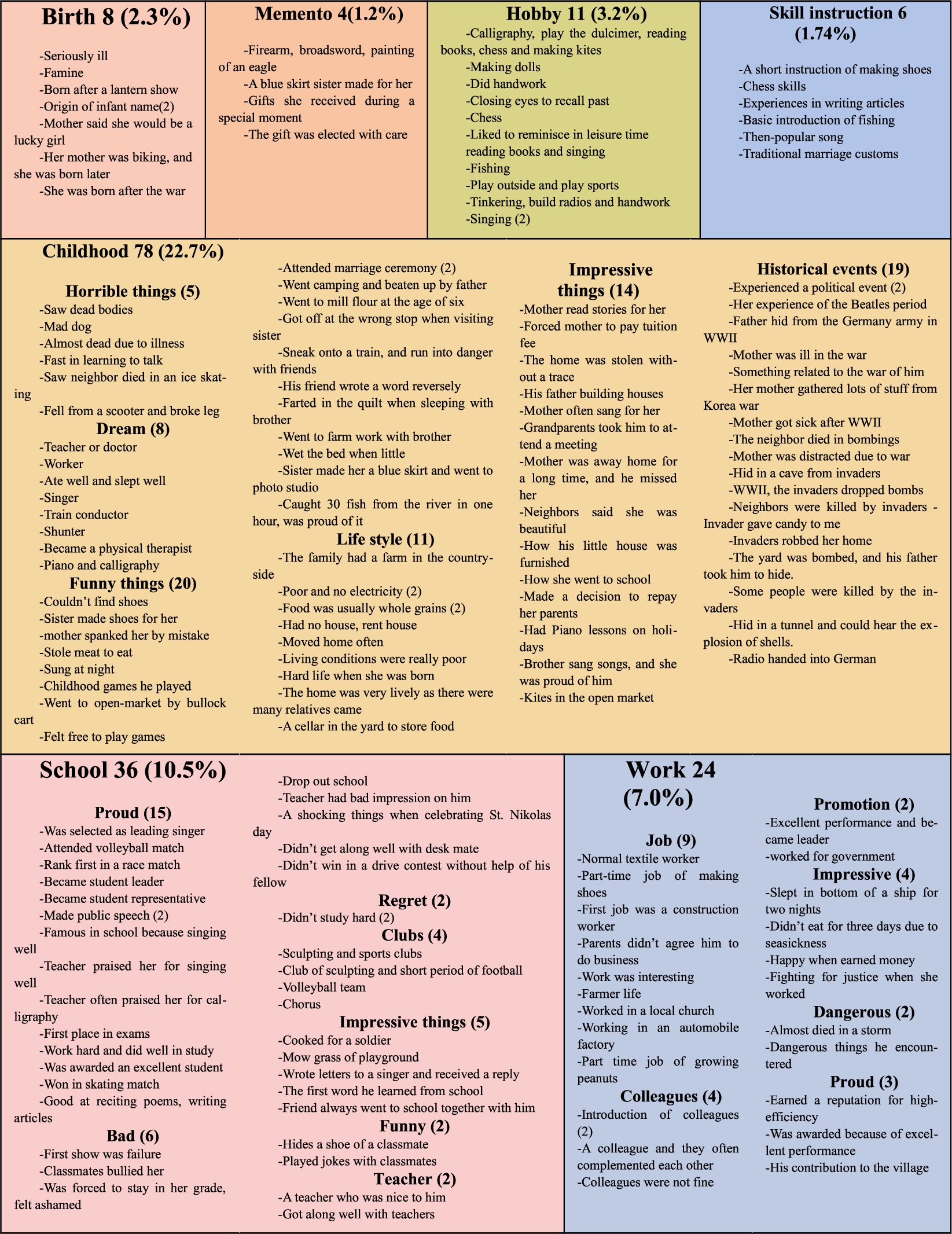

Themes, the absolute number, and the same number in percentages of the total number

|

Table 1

(Continued)

|

Fig. 6.

The elderlies’ usage frequency of prototype and demographic information.

Table 2

A snippet of transcription

| Transcription | Theme | Label |

| The first question is ‘were you ever told anything unusual about your birth.’ When I see this question um | Her mother believed she was a lucky girl as when she was born in autumn harvest | Birth |

5.2.Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting themes within data, and it minimally organizes the data set in (rich) detail [9]. Following [59], the themes of the stories were defined, and were labeled according to categories (Table 1).

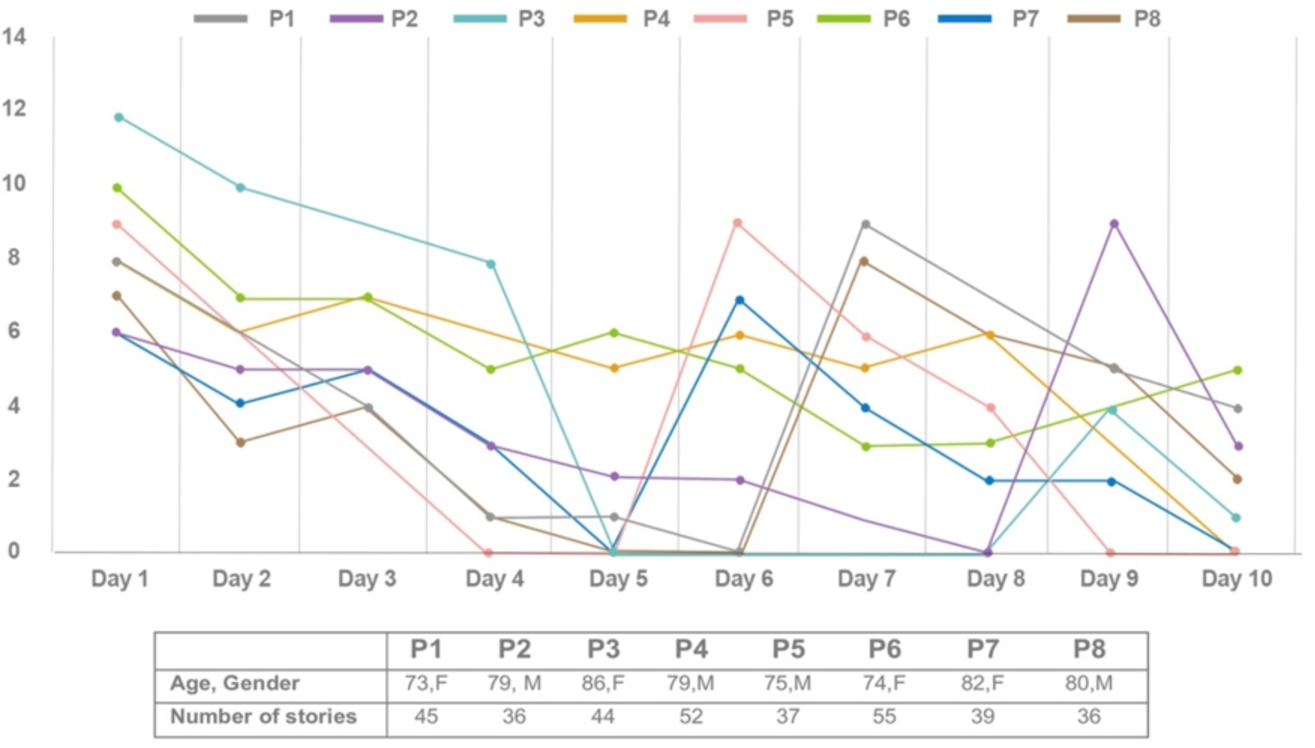

5.2.1.Overview of the story themes

Figure 7 describes themes, the absolute number, and the same number in percentages of the total number of stories. All the themes are generalized into the following categories, from high to low they were: Childhood (funny thing, historical event, impressive thing, lifestyle, dream, horrible thing), Family (family member, parents teaching, impressive thing, family story), Perception (feeling, insight, self-evaluation, world-view, belief, regret), School (proud thing, bad thing, impressive thing, club, funny thing, teacher, regret), Work (job, colleague, impressive thing, proud thing, promotion, danger), Marriage, Friends, Hobby, Retirement, Birth, Skill instruction, Memento, Fairy tale, Others. These stories could be roughly divided into description and perception. The former is mainly concerning the description of an event, object, or people. The latter is mainly concerning feeling, self-evaluation, and life insight, etc.

Fig. 7.

Percentage of story themes.

5.2.2.Proportions of the story themes and reasons

We further make a histogram to present the proportions of story themes better, reflecting their preferences for story topics from an objective perspective. For clarity, we present this section in the form of “proportion of the story topic” (quantitative data) + “reason behind it” (related interview data). 22.7% of the themes were about Childhood, among which “funny thing” and “historical event” were the most, which was in line with the interview: they would like to talk about happy and positive things, especially childhood. The reason, could be explained by the quotes from elderly interviewees: “Recalling the past makes me feel go back to the past.” “Telling happy things itself is a happy thing, and it also brings happiness to others.” Next was related to “lifestyle”, and the reason was, they often felt great changes had happened, and life now was different from the old-time, and they missed the old days. Followed by “dream” and “horrible thing”. Next, 21.2% were related to Family, among which the most was about “family member”, and followed by “parent’s teaching”, which were beliefs and ideals that parents taught them. The last was “family story” and “impressive thing”. Both the quantitative data and our interview indicated that the older adults focus more on the people they were familiar with, their parents, children, and friends, etc., and this was in line with Carstensen et al.’s study, pointing that older adults’ social and emotional goals towards strengthening existing emotionally fulfilling relationships rather than pursing novel social partners [12]. 13.7% were about Perception. Next was School (10.5%), among which “proud thing” was the most, which was also in line with the interview: they would like to tell stories they were proud of. One reason seems to be that they could not do some things they could before: “I like to recall the past, when I was young and strong. I am old now.” Followed by Work (7.0%), including the description of their jobs and their colleague. And others were some memorable events: “promotion”, “dangerous thing”, “proud thing”. Followed by Marriage and Impressive thing.

The category of Others was varied and hard to be classified into a certain category, mainly about memorable stories – for example, important life decision, mysterious thing, dangerous thing, etc. One thing to note was the Skill instruction, which was interspersed in their narratives – for instance, making hand-made shoes, chess skills, skills of writing articles. They were an intangible treasure worth preserving. Additionally, in the theme of Memento, which referred to photographs, mementos, and artifacts, as they were important visual clues to help the elderly to recall. These kinds of memory cues also need to be explored in the next iteration.

5.2.3.Finding: Story themes weren’t limited to the trigger questions

Results showed that story themes told by the elderly were not limited to the trigger questions provided by the young, nor didn’t they slavishly follow the trigger questions and dutifully record corresponding stories. Reasons are twofold. Firstly, some participants got used to using the prototype to tell stories gradually, and when a story suddenly came to his/her mind, he/she would like to use the prototype to record. For example, one audio starts with “I suddenly come up with an interesting thing, maybe it is not relevant

This finding indicated that trigger questions in our prototype were not the themes of stories, but the starting points. Also, the process of recalling gave them an opportunity to review his/her life, which was a critical review or a second glance on his/her life. Therefore, trigger questions that are targeted for stories that the elderly particularly want to tell, as well as new life insights and stories generated after answering the typical trigger questions could be added. Such as, “Do you have some stories you particularly would like to tell?” “Does the life review remind you of other interesting memories?”

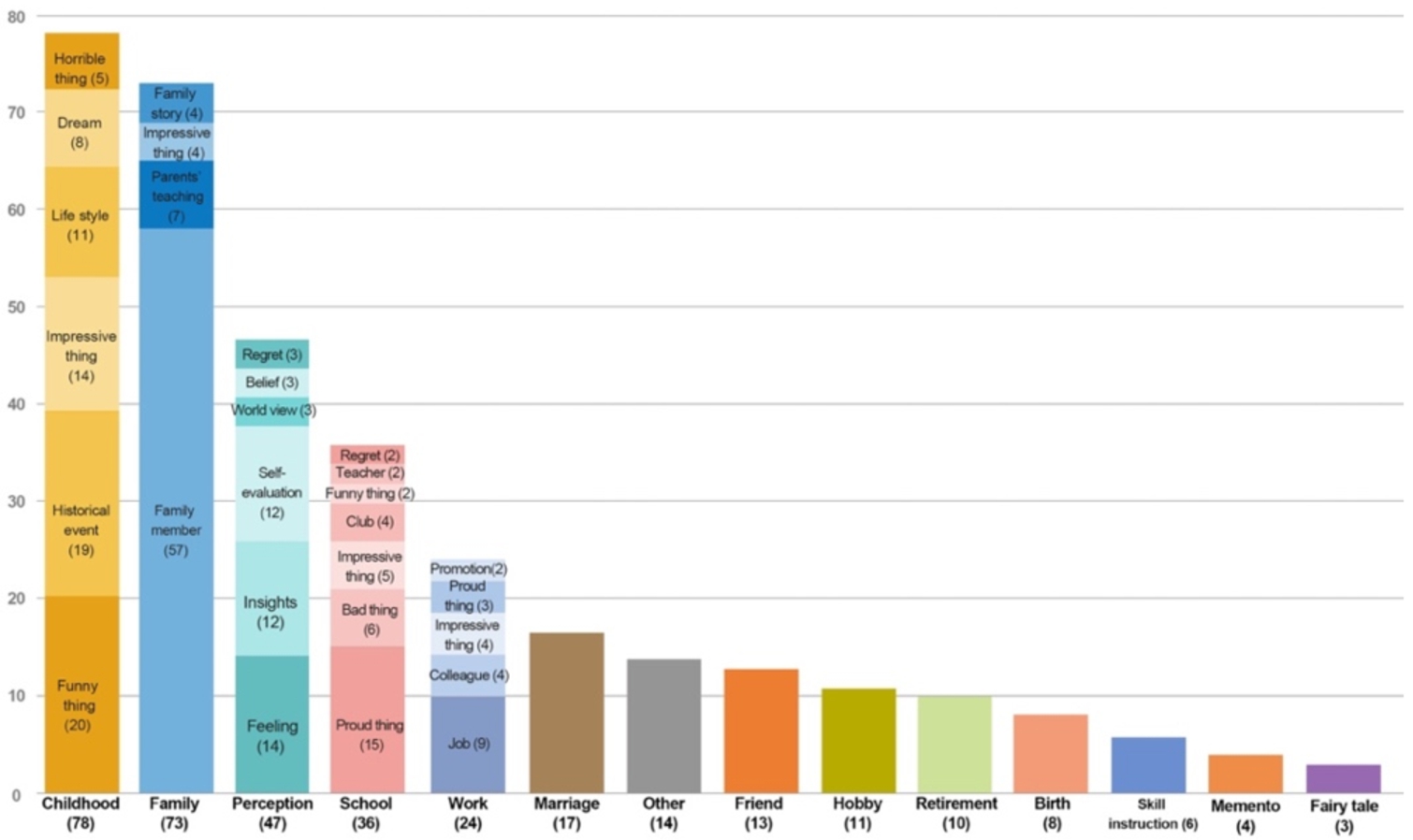

Fig. 8.

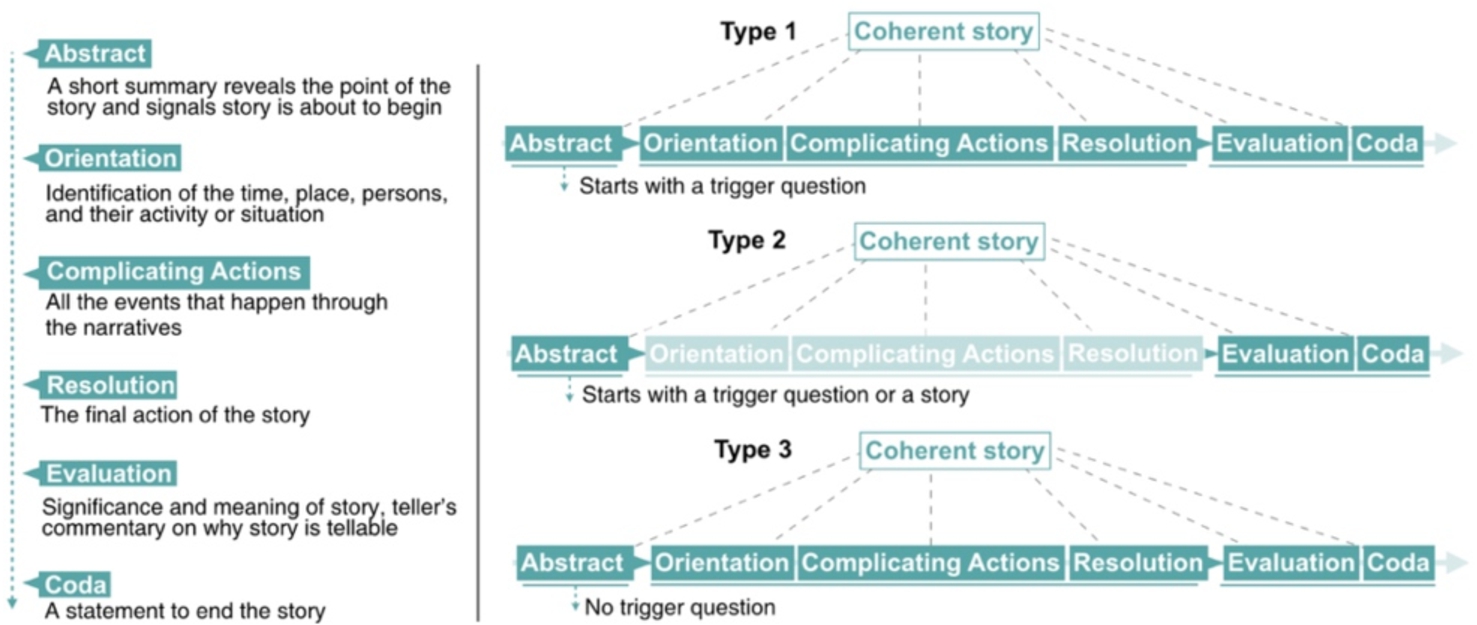

Labov’s model of natural narrative structure (left), and the four structural types in our case (right).

5.3.Structural analysis

Narratives are structured, having plots with both temporal and spatial features [2]. Structural analysis is necessary as a self-told life narrative reveals a common formal structure across a wide variety of contents [11]. The structure of stories is more stable than the content, while the content of stories is influenced by trigger questions [40]. We first analyzed the structure of stories by applying Labov’s model, then analyzed the structural relationship between the stories.

We applied Labov’s model to conduct structural analysis, and the first reason is that Labov’s model is applicable to “natural narrative” as its origins are situated in the everyday discourse practices of real speakers in real social contexts [64]. In our case, stories were life stories that related to the storyteller (the elderly), and were told in an informal manner. In other words, they are “natural narratives” [37]. Secondly, Labov’s model is based entirely on a talk by a single person, that is, the narrator, and it does not consider actual contributions by the audience [37]. In our case, most stories are personal narratives. According to Labov’s model, narratives have formal properties, and each has a function. A “fully formed” narrative includes six common elements: Abstract, Orientation, Complicating action, Resolution, Evaluation, and Coda [42]. After the Labov’s model was applied in our transcriptions, three types emerged.

5.3.1.Three structure types of the stories in our study

Type one: Trigger question serves as “Abstract”, and the story consists of all six elements As shown in Fig. 8, this is the most common type in our study. It contains not only concrete plots but also comments and reflections. Specifically, trigger question acts as “Abstract”, which is the introductory part, and a summary of the event to spark attention. The participants often read the question out, in the meanwhile, they are thinking and recalling. For instance, most start with: “As for my first experience of leaving home. Hmm

Type two: The story without “Orientation”, “Complicating Actions”, “Resolution” This type contains only subjective perception without a specific story plot. Trigger question also acts as “Abstract”, and this type is normally evoked by abstract trigger questions, such as “How would you describe your world view?” Another situation was emerging at the end of a story, for example, After telling a story of his childhood friend, the audio then turned to tell the elderly’s understanding of “friend”, including his definition of a true friend, his principle of making friends. In our case, these subjective perceptions include word view, insight on life, feeling, self-evaluation, and regret, etc.

Type three: The story not starting with a trigger question This type appears in the following situations: First, stories that they specifically would like to tell, but are not covered by the trigger questions. Second, one story might remind the elderly of another related story. For example, one story is about the club she used to join, and she talked chorus, and then a funny thing that happened in that club, and then a friend she met there. Finally, she said: “I find recalling the past is interesting, a train of recollections are awakened, even those nearly forgot.”

Table 3

A snippet of stories told by the elderly

|

Table 4

A snippet of conversation transcription

| Y | This question is what was going on in your family, your community, and world at the time of your birth? |

| E | There were my parents and grandfather. Umm |

| Y | So what’s your life like at that time? |

| E | We didn’t own a house, we just rent. |

| Y | Why? Was it because in a war? |

| E | Yes, it was in WWII. |

5.3.2.The structural relationship between the stories

The trigger questions were explicitly about given topics, but stories remained non-directive. That is, the trigger questions act as jumping-off points which spark broader memories, gradually the narrative becomes non-directive and unfocused. Concerning the contents, some were lengthy and discursive, which started from the trigger questions and gradually tangent, but in most cases, the content would return to the original point. The snippet (Table 3) is one example that one story was interlarded with another story.

5.3.3.Insights on structural analysis

Despite the Type one and Type two were most typical in our study, the Type three – the story not starting with a trigger question implies that open questions should be added, since trigger questions couldn’t cover every aspect of one’s life. The open questions could be like: “Do you have stories that the trigger questions aren’t covered?” While by analyzing the structural relationship between the stories, we found the elderly’ storytelling was not always told in a linear fashion.

5.4.Interactional analysis

Storytelling itself has properties of social interaction, and it performs social actions, and audiences are involved directly or indirectly [60]. Interactional analysis emphasizes on the dialogic process between teller and listener. In our study, social interaction behaviors occurred in two cases: the young contacted the elderly after listening to the stories, and the elderly and the young used Slots-Story face-to-face.

5.4.1.Stories told when using Slot-story face-to-face are “small stories”

The term “small stories” is used to describe a variety of non-prototypical kinds of narrative, including tales of ongoing, future, hypothetical, or already-shared events [31]. Table 4 is an example snippet of using the prototype face-to-face, which audios collected included conversations between the elderly and her grandson. In this case, the stories served for the conversations. Trigger questions were the starting point of the conversations, which were easy to be irrelevant to the trigger questions. Meanwhile, the young provided instant feedback, which acted as a new memory clue to trigger the storyteller telling new stories. Therefore, more topics were launched. Additionally, in this case, the stories were short, and the storytelling gradually turned into conversation pattern. Stories are fewer performances of self and more aimed at creating shared expectations [31]. In our case, we found the listeners influenced the storyteller in serval ways: by evaluations, by changing trigger questions, and even by acting as co-tellers, where teller and listener create meaning collaboratively.

5.4.2.Using Slots-Story separately

Unlike conversations that the listener could communicate with storyteller instantly, the storytelling and story listening were un-simultaneous when using separately. Reasons for the young contacting the elderly after listening to the stories are concluded as: First, the young wanted to know more detail of some stories. Second, the young expressed their viewpoints on the elderly’s stories. Third, the young expressed emotions of love, appreciation, and sympathy, etc. to the elderly. Either way, intergenerational communications were raised during the field study.

5.4.3.Insights on interactional analysis

Based on the interactional analysis, we could understand the differences between using the prototype face-to-face and separately by the elderly and their children. In the former case, the prototype acts as a “conversation topic generator”, and the storytelling serves for conversations: the audio recordings were mixed with multiple people, and stories they told were not complete but fragmented. While in the latter case, the elderly could totally calm down to reminiscence and were entirely concentrated to tell the past with deeper insights.

6.Discussion

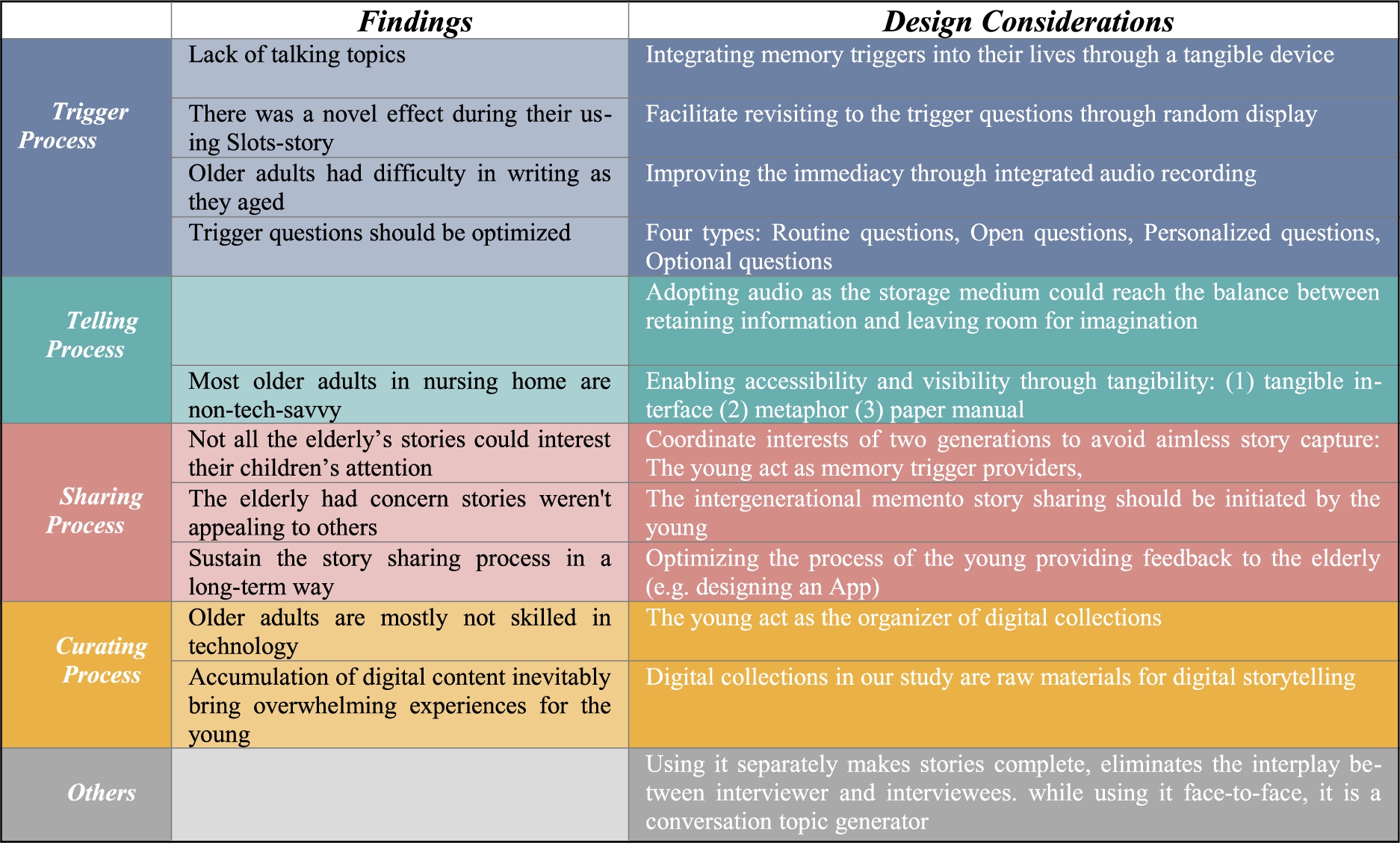

The discussion section is roughly organized into two major sub-sections: characteristics of older adults’ life story sharing, and design considerations for promoting older adults’ storytelling with their children. The former reveals the current situation and problems they encountered of older adults’ story sharing. In response to it, the latter proposes corresponding design strategies derived from the implementation of Slots-Story.

6.1.Summary of current situation of intergenerational storytelling

Although their children visited them regularly (from once a week to once a month), the duration of every visit was limited. Compared with the young generation that tended to share the present, the older adults preferred more to recall and share the past. Children were who the elderly would like to tell stories to, because they hoped they could be remembered, and they had the responsibility of passing on family stories. However, their children seemed to lack awareness of listening and preserving the elderly’s stories. They didn’t share life stories specifically and deliberately in daily lives, and life story sharing was fragmented and happened unconsciously. In addition, the elderly had the concern that their stories were unappealing to others. The gap between the generations regarding life story sharing needs to be bridged.

6.2.Design considerations

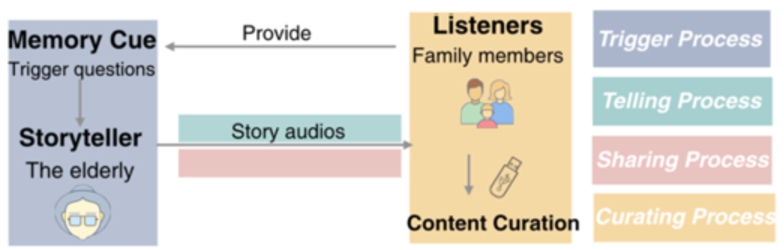

For clarity, we break the intergenerational story sharing into four steps: Trigger Process (the process of elderly’s recalling), Telling Process (the elderly’s storytelling), and Sharing Process (story sharing), and Curating Process (the curation of digital stories).

6.2.1.Design for the elderly’s reminiscence (Trigger Process)

6.2.1.1. Integrating memory triggers into their lives through a tangible device The interviews indicated one major problem of their life story sharing was the apparent lack of topics, and memory triggers are so indispensable that it is one of the keys to success in terms of facilitating and supporting remembering [67]. A memory trigger is “a circumstance or piece of information which aids the memory in retrieving details not recalled spontaneously [55].” Despite the numerous study focusing on why and how memory triggers evoke people’s reminiscence, we investigate how to integrate them into the elderly’s daily lives. In our case, we adopt trigger questions as memory cues. Compared with other types of memory cues, questions are more explicit and straightforward, and targeted answers will be triggered [4]. As mentioned, older adults and their children’s daily schedules were antisymmetric, and their children’ visiting time was limited (usually 2–4 hours). Therefore, we hoped the elderly could tell life stories independently in their daily lives. Specifically, a tangible device with simple operation was designed, which was accepted by the elderly in the field study. From the perspective of design, Slots-Story is an interactive device with a tangible interface. The classic appearance made it unobtrusive when putting it at home, which would encourage and attract the elderly to use. In this sense, Slots-Story serves as a tangible reminder, embedded in their everyday landscape.

Facilitate revisiting to the trigger questions through random question display

Although previous research point that physical object are much more embedded in the everyday landscape and may trigger memories simply by being seen [33], simple physicality is not enough. In field study, we found an obvious novel effect during their using the prototype. Although the prototype itself should be unobtrusive when putting it at their home, the trigger questions for displaying should be dynamic to attract the elderly’s attention and encourage them to use. Therefore, questions could be displayed randomly like a slide, acting as involuntary memory cues, to achieve long-term, sustained use.

6.2.2.Implications for designing trigger questions (Trigger process)

Based on the above analysis, we conclude that trigger questions should contain four types: Routine questions, Open questions, Personalized questions, Optional questions.

Routine questions cover most aspects of life themes, in our case from [4]. Answering these questions contributes to an overview of their life course by recalling their experiences and events memorable. This overview of their life span offers two advantages: Firstly, as stated, the recalling allows the elderly to review his/her life, and new life insights will be generated. Through integrating past experiences with some view of the future in mind, the life story narratives help the elderly acquire a new sense of personal authorship and life reflections in their life journey [50]. Secondly, stories that irrelevant to trigger questions will also be recalled, as discussed in the thematic analysis. Open questions are targeted for stories that the elderly particularly want to tell, as well as new life insights and stories generated after answering routine questions. We found that the elderly told some stories that were irrelevant to the trigger questions. These story themes were personalized and individual, which were not easily covered by the trigger questions, and were hard to be classified into a certain category. Therefore, open questions were necessary to prompt them to tell, which could be like: “Do you have some stories you particularly would like to tell?” “Do you have stories that the trigger questions don’t cover?” Secondly, after a life review process by answering the Routine questions, the elderly will acquire a new sense of personal authorship and life reflections in life journey. Open questions could be like: “What’s your new insights on life after a review of your life?” Alternatively, “Does the life review remind you of other interesting memories? Personalized questions are raised by their children, and it is a way to involve the young generation. We found topics that the young were interested were varied, and not all the questions fit the individual person. The diversity requires personalization of the trigger questions. Optional questions: Topics could be as comprehensive as possible, and negative topics could be optional.

Although negative topics would bring passive memories to them, the interviews turned out that Slots-Story could help older people vent their bad memories to some extent, and therefore it might be better to tell memories out than to bury them deep in the bottom of their hearts. Of course, this did not apply to all older people, and we shouldn’t force the older adults to recall negative memories, but we should also give them a chance to tell if they want to. Therefore, negative questions could be optional.

6.2.3.Design for the elderly’s life storytelling (Telling Process)

Making the memory triggers materially present in their home only supports their reminiscence. To facilitate their storytelling, the following considerations of lowering their cost of storytelling are derived.

6.2.3.1. Improving the immediacy through integrated audio recording Similar to the situations of young generations’ storytelling, which is hampered by the lack of immediacy (switch the computer on, navigate the files, and start pc application) [47]. According to our interview, although some older adults had the desires of writing their stories, the heavy load of writing hindered that. Given that they felt difficulty in writing as they age, direct speaking is more natural than handwriting. Moreover, the strategy of “integrated capture” was adopted in our prototype, where interaction with objects that are a natural part of the activity initiates capture of that moment [38]. To be specific, the stories told by the elderly are recorded by a simple press operation, offering a “seamless connection” between viewing trigger questions and storytelling. The behavior of recording audio is also less likely to intrude and disrupt the moment than other forms of capture, because prototype could be unobtrusive, even hidden.

6.2.3.2. Adopting audio as the storage medium could reach the balance between retaining information and leaving room for imagination In our context, audio is the optimum story forms between text, audio, and video. First, compared with text, audio contains emotions, personalities, and feelings of the voice, which could convey more information than text alone. The audio could also evoke a deeper reminiscence and emotional response since the sound draws the listener more into the recorded moment [38]. Second, audio also shows advantages over video. Psychologically speaking, the video is a hot medium containing a higher density of information, thus it requires the viewer to do less interpretive work to understand the content [30]. Video is too real to allow room for thinking and talking about the past with others [13]. According to the young participants, viewing the mementos while listening to the audios gave them space for imagination and reminiscence. Although the previous study reports that sounds are ideal materials to enrich digital photography, compared to handwriting, text or even short video clips [18]. In our field study, the ambient sound was emphasized by the young participants, which could make the young imagine the scenarios of the elderly’s storytelling, rendering the atmosphere, enhancing familiarity.

6.2.3.3. Enabling accessibility and visibility through tangibility: Including tangible interface, metaphor, and paper manual Although the previous study has reported the physicality of the tangible interface conveys advantages over conventional graphical interfaces in terms of its support for real-world skills [22], natural affordances, learning and memorization [41] and for collaborative activity [36]. Our finding further expand the advantages of tangibility for elderly users.

First, the prototype is positioned on the desk, occupying space, and act as an external physical reminder adding to the elderly’s daily landscape. The tangibility could produce deeper engagement than digital materials. Additionally, one unexpected finding in our filed study was the elderly appreciated the flash disk as a tangible carrier to preserve their memories. Its physicality was better in accordance with their cognition of concept of storing, who were familiar with tapes and DVD. The tangibility seemingly brought them a sense of familiarity and “sureness”. Second, interaction is strongly associated with the content organization. Questions organization in Slots-Story is based on the metaphor of slot-machine, which enables the question navigation intuitive and more natural: the elderly user is able to explicitly browse a question by pulling up/down the handle. Third, paper manual. As we found in the pre-study interview, older adults in nursing home relied heavily on paper and preferred physical interaction. The instructions in paper manuals are static, which are easier for some older users, as it matched their learning style. Research indicates that older adults have a stronger preference for using the device’s instruction manual over trial-and-error because it matches their learning style.

6.2.3.4. Three advantages of using prototype independently by the elderly First advantage of using prototype independently is eliminating the interplay between interviewer and interviewees. Traditionally speaking, a life story biography needs to be conducted by a professional interviewer. In the traditional manual life story interview, the interplay between interviewer and interviewee was a central concern. The interviewer’s characteristics are bound to affect the course the interview will take. The interviewee may be influenced or even dominated by the interviewer, which made collecting information positively misleading [51]. Non-involvement of the interviewer is an ideal but unattainable situation. The Slots-Story could eliminate the interplay between interviewer and interviewees to some extent. The elderly interviewee could freely choose wherever, whenever they want to tell their life stories. In this sense, Slots-Story makes it possible that stories could be told in a way that is both natural and comfortable for the elderly. Second is making the stories complete and integrated. When the elderly use the prototype by themselves, it was asynchronous, and they could totally calm down to reminiscence and are entirely concentrated to tell the past with deeper insights. As one elderly participant pointed out in the interview, when telling stories by herself, she could focus on the reminiscence and recalling, and she need not care about other’s attitudes or expressions, nor did she worry about being interpreted. In this case, the stories they told were complete and integrated. The third advantage is that it left rooms for older adults to tell their life stories. As the young interviewees pointed out, the prototype was a promising way to ask some embarrassing questions. Likewise, the elderly interviewee also expressed their concern that they felt shy when talking about embarrassing topics. Using Slots-Story separately could naturally alleviate this problem.

6.2.3.5. It is a conversation topic generator when using face-to-face It is a natural chat and the storytelling serves for conversations: the young act as the listener and provides instant feedback. The storyteller (the elderly) must monitor the reaction of the audience, responding to explicit and implicit questions about the setting, focus, or outcome of the story [40]. They need to ensure the audience stays engaged by appealing to the audience’s attention. Accordingly, the audio recordings are mixed with multiple people, and stories they told are not complete but fragmented. While when using separately, it was an asynchronous process. Older adults could totally be immersed in reminiscence, and were fully concentrated to tell the past with deeper insights, without concerning the listeners’ feedback. In such circumstance, the stories are complete and integrated, which are easy to preserve and pass down for generations.

6.2.4.Design for the elderly’s memento story sharing (Sharing Process)

6.2.4.1. Coordinate the interests of different generations to avoid aimless memento capture The intergenerational life story sharing should be initiated by the young, given that the elderly had the concern that their stories were less appealing to others. In our study, we found although most young participants showed interests in their parents/grandparents’ stories, the older adults had an ambivalence regarding sharing them. On the one hand, they would like to tell stories to their children, either because they hoped they could be remembered, or because they felt they had the responsibility of carrying on family history. On the other hand, they worried their children were not interested in their stories. They didn’t want to bother their children, nor did they want to force them to listen. Therefore, there actually exists a gap between the two generations regarding memento story sharing, which needs to be bridged.

Second, interests of these two generations should be further coordinated. In order to avoid blind storytelling by the older adults, in our case, the young could provide trigger questions, that is to say, the roles of the story listeners (the young) are highlighted in our case. Although previous research indicates the importance the roles of story listeners by pointing that story sharing is a collaboration process requiring the participation of both storyteller and story listener, and it makes sense only when both old and young generations participate and engage in. Our research further points that the story listener could not only be the audience, but also be the memory trigger provider. It also makes the elderly feel that their children are interested in their life stories.

Third, intergenerational cooperation promotes intergenerational communication. The Slots-Story system contains two phases: editing trigger questions and story recording. Older adults had the demand for preserving their lives, but they lack appropriate tools. Given that older adults are normally not skilled in technology, we then propose the scheme of intergenerational collaboration, the young and older adults had different duties: trigger questions editing is completed by the young, and older adults are the story producers. The whole process is achieved by intergenerational collaboration. Not only the stories themselves retain elements of intimacy and personal connection, but also intergenerational communication and conversation are generated. In the sharing process, the young generation get a better understanding of their families’ past, while older adults feel more fulfilled.

6.2.4.2. The process of story sharing We formulate the process of story sharing in our study (Fig. 9): Memory cues take various forms, and in our case trigger questions are adopted. Storytellers are exporters of stories, and listeners are receivers of the stories. Stories are also in various forms (text, drawing, audio, video), and in our case, audio is adopted. We see story sharing is a not solitary but a collaboration process: the listeners not only provide feedback on the stories but also are the memory trigger providers. The listeners’ role is highlighted in our study, and the story could even be viewed as a product of two minds instead of one.

Fig. 9.

The process of story sharing in our study.

Table 5

Findings gathered from field study and the corresponding design considerations

|

6.2.4.3. The sustainability of Slots-Story The sustainability embodies in two aspects: First, life stories range and increase across time. Regularly life stories one elderly told cover the events of the elderly’s life course up to the present. Unless the storyteller is very old and sees himself/herself at the end of their life, any biographical account, as well as the life it purports to represent, will be presented as incomplete [51]. Thus, the same trigger questions could be asked again when they grow even older, and different stories and feelings will be generated. In addition, stories have new meanings at different times [27]. According to the elderly participants, some mentioned they even would like to listen to their own life stories in the future. Second, close the loop of story sharing process by involving the young generation. Feedback from the young could effectively encourage the storytellers to tell more, and also the feedback may act as a new memory cue. In the current situation, the using of flash disk brought inconvenience to the young participants. Efforts should be made to turn them into active participants. This could be achieved by optimizing the process of the young providing feedback to the elderly, after listening to the stories. As suggested by the young participants in the interview, a cellphone application could be designed for them, together with the prototype, making them a complete system.

6.2.5.Digital collections in our study are raw materials for digital storytelling (Curating Process)

The accumulation and proliferation of digital content inevitably bring overwhelming experiences, putting pressure on the organization and managing of the digital collections. Although in our field study, most young participants stated they would make good use of the digital content and treasure them, currently they are in a state of overload due to a lack of curation of digital content, which has a negative effect on long-term retrieval of photographs [6]. To better make use of the digital content, based on the feedback and previous study, we think the digital collections in our study are raw materials for digital storytelling. Digital storytelling is the process of creating a narrative, driven by a central storyteller and supporting that narrative with a combination of text, still photographs, audio, graphics, and animations [24]. Traditionally speaking, methods of storytelling collection are typically realized through interview, and visual images and interview data produce multimodal outputs [17]. Apparently, Slots-Story contributes to life story acquisition since it is a story collector in a sense. The digital collections could be further developed into a multimedia album, or transcribed into text to make a biography, etc.

7.Conclusion

7.1.Design strategies for facilitating intergenerational storytelling for older adults

In this paper, we report our implementation of Slots-Story, a tangible device facilitating life storytelling for older adults. Given the above discussions, we provide the takeaway (Table 5) to conclude design strategies for facilitating intergenerational storytelling for older adults.

7.2.Limitation and future work

Our prototype was designed for younger adults older than twenty, since in early adolescence, children strive for freedom and independence, and they spend less time together. This period may be a time when parents and children have more difficulties communicating [32]. For prototype itself, it was more a research prototype than a mature product: It was with some trade-offs. For example, the using of flash disk brought inconvenience to the participants. It will be more convenient for teenagers if the story-audio could be uploaded to internet, making the story sharing wirelessly. Additionally, the design intervention in our study was relatively short-term, which was not comprehensive enough to cover every aspect of a life span for the elderly people.