The Profile of the Italian Centers for Cognitive Disorders and Dementia in the Context of New Drugs in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

Background:

The wait for the upcoming disease-modifying therapies (DMT) for Alzheimer’s disease in Europe is raising questions about the preparedness of national healthcare systems to conduct accurate diagnoses and effective prescriptions. In this article, we focus on the current situation in Italy.

Objective:

The primary goal is to propose a profile of the Italian Centers for Cognitive Disorders and Dementias (CCDDs) that could be taken into consideration by regional and autonomous provincial authorities when deciding on the prescribing centers for DMT.

Methods:

Based on responses to a national survey on CCDDs in Italy, we identified the CCDDs that meet the requirements for effective prescription: 1) Multidisciplinary team; 2) Minimum Core Test for the neuropsychological assessment; 3) PET, CSF, and Brain MRI assessments. Univariate and multivariate comparisons were conducted between CCDDs that met the criteria and the others.

Results:

Only 10.4% of CCDDs met the requirements for effective DMT prescription, mainly located in Northern Italy. They are also characterized by longer opening hours, a higher number of professionals, a university location, and a higher frequency of conducting genetic tests, and could potentially result in prescribing centers.

Conclusions:

The findings suggest that the Italian national healthcare system may benefit from further enhancements to facilitate the effective prescription of DMTs. This could involve initiatives to reduce fragmentation, ensure adequate resources and equipment, and secure sufficient funding to support this aspect of healthcare delivery.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition that progresses steadily, cannot be reversed, and ultimately leads to fatality.1 AD is the most common cause of dementia in those aged 65 and older globally. AD and other forms of dementia are often underestimated due to underdiagnosis in many countries.2 Despite a decrease in prevalence and incidence over the past 25 years in high-income countries, the total number of people with AD or other dementias is expected to continue increasing dramatically because of the growing number of people in the oldest age groups.3 Recent estimates4 foresee a substantial global increase in dementia cases from 57.4 million in 2019 to 152.8 million by 2050. Geographical variability is evident, with minimal percentage changes in high-income regions such as Asia Pacific and Western Europe, and the most significant increases expected in low and middle-income countries (i.e., North Africa, the Middle East, and Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa). Italy is expected to experience a 56% rise in dementia cases by 2050 (2.3 million).4 For these reasons, strategies that can hinder or postpone the onset of the disease and the resulting cognitive decline are urgently required.5

Recently, there has been a consecutive development of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), including anti-amyloid-β (anti-Aβ) monoclonal antibodies (e.g., aducanumab, lecanemab, and donanemab), developed to alter the underlying pathology of AD. These therapies showed potential efficacy in slowing, albeit modestly, the decline of cognitive functions although the risk-benefit profile remains very controversial and an analysis by clinical responders is largely insufficient.6–8 Aducanumab received conditional approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2021, and lecanemab received full approval in 2023.9,10 The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended refusing marketing authorization for aducanumab and is currently evaluating lecanemab.11 Additionally, lecanemab was granted approval by the Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA).12

The market entry of DMT is likely anticipated in Europe within the next years13 and is poised to revolutionize the field. However, transitioning these therapies from clinical trials to real-world healthcare systems should not be taken for granted. Screening people with dementia (PwD) suitable for treatment, ensuring appropriate prescriptions, and implementing follow-up after treatment with DMT are high-priority tasks for healthcare systems.14 In the USA, an examination of healthcare system readiness for new DMT prescription revealed significant challenges, including limited access to specialists, imaging facilities, and infusion centers.15 A similar investigation in six European countries highlighted a potential lack of the necessary capacity of healthcare infrastructures to provide PwD with timely access to treatment. This is primarily attributed to limitations in the ability of specialists to diagnose and in the availability of infusion delivery services.16

The features of the FDA-approved Prescribing Information9,10 and the Appropriate Use Recommendations from expert clinicians indicate how PwD selection and therapy maintenance should be conducted.17,18 DMTs have been tested in patients with a diagnosis of MCI due to AD and AD dementia17,19, based on the National Institute on Aging (NIA)-Alzheimer’s Association (AA) clinical criteria. 20,21 Core clinical criteria for the diagnosis of MCI due to AD comprise concern regarding a change in cognition, reported by the patient or an informant, objective impairment in one or more cognitive domains assessed with a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests, generally preserved activities of daily living, no dementia, and a positive AD biomarker.20 Diagnosis of probable AD dementia necessitates cognitive or behavioral impairment involving a minimum of two of the following domains: memory, executive function, visuospatial function, language, behavior. Cognitive impairment is detected and diagnosed through a combination of history-taking from the patient and a knowledgeable informant and an objective cognitive assessment through neuropsychological testing. Interference with the ability to function at work or in usual activities is also observed, with a decline from a previous level of functioning and performance, and a positive amyloid biomarker.21 To ensure mild severity of cognitive impairment, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)22 scores of 22–30 are suggested.17 Published clinical trials, FDA prescribing guidelines, and appropriate use recommendations from expert clinicians9–12,17, highlight the necessity to evaluate inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients to guarantee the treatment’s efficacy and safety. Individuals suspected of having dementia in many countries are referred to specialized memory clinics.23 To provide an effective prescription of DMT, these facilities should have: 1) Multi-professional teams (i.e., more than one physician specialized in cognitive disorders, and at least one psychologist/neuropsychologist); 2) Capability to conduct comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations; 3) Capability for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and/or PET biomarker assessments andMRI.

In Italy, the Centers for Cognitive Disorders and Dementia (CCDDs) are healthcare services that play a pivotal role in dementia diagnosis and care. Additionally, they are responsible for prescribing antidementia and antipsychotic drugs.24 CCDDs actively provide psychosocial, educational, and rehabilitative interventions, as well as post-diagnosis psychosocial support for both PwD and caregivers.25 In 2022, a national survey was conducted in Italy on CCDDs to provide a comprehensive description of their characteristics and organizational aspects.26 The latest update identified 534 main CCDDs and 163 branches, revealing significant heterogeneity in organizational structure and geographic distribution, similar to many countries.26 This variability is often attributed to the lack of international or national guidelines and established organizational standards.27 Specifically, Italian CCDDs predominantly involve neurologists and geriatricians as specialized physicians, along with psychologists and neuropsychologists.26 Neuropsychological assessments are available in 94% of these facilities, but there are variations in the number of tests administered. In particular, 57.1% of Italian CCDDs use a Minimum Core Test (MCT) (Vaccaro et al., unpublished data), defined as a neuropsychological assessment that includes at least one measure for each of the following cognitive domains: both verbal and visual episodic memory, attention, constructional praxis, verbal fluency, and executive functions.28 Moreover, amyloid PET, CSF assessments and brain MRI are provided, directly or by agreement, in 66.7%, 62.4%, and 81.6% of facilities, respectively.26

In Italy, the “Interceptor” project is underway in 19 CCDDs, which has the dual purpose of identifying the best combination of biomarkers predictive of conversion to dementia in a cohort of patients with MCI and of proposing a hub-spoke organizational model of clinical and expert centers in individual biomarkers.29 The results of the Interceptor study will be used to define the subgroup of patients who will be eligible for reimbursement for DMT within the National Health System (NHS). In the Italian NHS, the decision to identify the prescribing centers for DMT is the responsibility of the regional and autonomous provincial health authorities.

The primary objective of this study is to propose a profile of Italian CCDDs that could be taken into consideration by regional and autonomous provincial authorities when deciding on the prescribing centers for DMT. Additionally, the study aims to compare facilities with prescriptive capabilities with others, highlighting differences in organizational aspects and activity profiles, services provided to PwD, and continuing professional development and counselling services. Insights gained could inform strategic decision-making and resource allocation within the healthcare sector.

METHODS

Surveyed facilities

All 534 CCDDs operating in Italy were invited to participate in a survey study thanks to the coordinated action with the representatives of the Regions and Autonomous Provinces in the Permanent National Table on Dementia. A total of 223 CCDDs (41.8%) are in the Northern regions, 105 (19.7%) in the Central regions, and 206 (38.5%) in the South and Islands. A total of 511 (96%) CCDDs provided information on location and accessibility, while 450 (84%) CCDDs also provided information about staff, care services, type of diagnosis and characteristics of clinical activities based on data referred to 2019, and were considered for this study (further details on the characteristics of the surveyed CCDDs are reported in a previous paper).26

Survey structure

The survey questionnaire comprises two sections: profile and data-collection form. The profile part gathers details encompassing 1) primary facility and branch addresses, along with contact information; 2) the facility’s category (e.g., territorial, hospital, university); 3) operational days and hours weekly (for both the main facility and branches); 4) additional information regarding services, such as PwD access methods, activation date of the service, and clinical director of the facility (https://www.demenze.it/it-mappa). The data collection form, consisting of 20 questions, solicits information on 1) staff composition; 2) availability of an Integrated Care Pathway (ICP) document and digital archive; 3) utilized clinical and cognitive assessment tools; 4) clinical activities (e.g., waiting lists and average wait times for service access); 5) annual patient evaluation count and types of diagnoses; 6) direct provision or agreement-based availability of psychosocial, educational, and rehabilitation services. Respondents were requested to furnish information about the year 2019, the last one preceding the pandemic. Additionally, participants were queried about the activity of CCDDs during the pandemic years 2020 and 2021, encompassing whether the service remained fully operational or experienced partial closures, as well as the average duration of any such closures (for further details, refer to the previous paper).26

Procedure

Survey research took place from July 2022 to February 2023. Invitations for participation were extended to CCDDs through cover letters delivered via email. These letters provided information about the lead researcher, study objectives, and the goals of the “Italian Fund for Alzheimer’s and other dementias”. Clinical representatives from the services were responsible for administering the self-administered computer-based questionnaire. Participants had the flexibility to complete the survey in multiple sessions, with an average completion time ranging from 30 to 60 minutes. Upon obtaining consent, responses were automatically recorded in the online platform and then exported for statistical analysis, following the privacy policy. Additional details can be found in the previous paper.26

Requirements for effective prescription

Based on published clinical trials, FDA prescribing guidelines, and appropriate use recommendations from expert clinicians,8–11 we propose the requirements that CCDDs need to fulfill to ensure an effective prescription of DMT: 1) The presence of a multidisciplinary team, which includes at least two specialized medical professionals among geriatricians, neurologists, and psychiatrists, and at least one psychologist or neuropsychologist; 2) The use of MCT during the neuropsychological assessment; 3) The availability, directly or by agreement, of amyloid PET, CSF and Brain MRI assessments. Considering these specific characteristics, two groups of CCDDs were identified: one group that meets the specified requirements (“presence”), and another group that does not meet the requirements (“absence”).

Characteristics assessment of CCDDs

The characteristics of CCDDs were systematically evaluated across three distinct categories: 1) Organizational Aspects and Activity Profile. This category encompassed various elements, including the Italian macro-area of location, type of setting, weekly opening hours, total years of facility operation, staff availability beyond practitioners and psychologists, the presence of a computerized archive, availability of ICPs, existence of a waiting list for services, average duration of follow-up visits, and the annual number of patients attending the facilities. 2) Services Provided to Patients. The second category delved into services during the diagnostic phase, encompassing blood tests, ECG, cardiological examination, neuroimaging (MRI, CT scan, EEG, PET FDG, PET amyloid, SPECT), biomarker assessments (CSF, plasma), genetic testing and counselling, various rehabilitation treatments, telemedicine services, and more. This category also covered interventions such as Alzheimer’s café, meeting centers, mindfulness, art therapy, and other psychosocial, educational, and rehabilitative measures. 3) Continuing Professional Development and Counselling Services. The third category focused on continuing professional development and counselling services provided during the care phase. This included individual patient counselling, counselling for patients along with their families, individual counselling for family members and caregivers, informational activities, legal aid promotion, legal support, and training and professional updatingactivities.

Statistical analysis

The comparison between the “presence” and “absence” groups was conducted utilizing appropriate statistical tests for different variable types. Categorical variables were assessed using the Chi-square test, while continuous parameters were evaluated with the Wilcoxon test. Initial exploration involved univariable analysis, fixing a threshold of significance for a p-value of 0.05. This step identified characteristics associated with the presence of criteria for each of the three groups. Variables selected at the univariable level for each group were incorporated into three separate full models, each representing a specific topic. The logistic regression models were used to identify the characteristics independently associated with the presence of criteria within each group. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0 software.30

Ethical approvement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Italian National Institute of Health (Protocol 0024270; 22 June 2022).

RESULTS

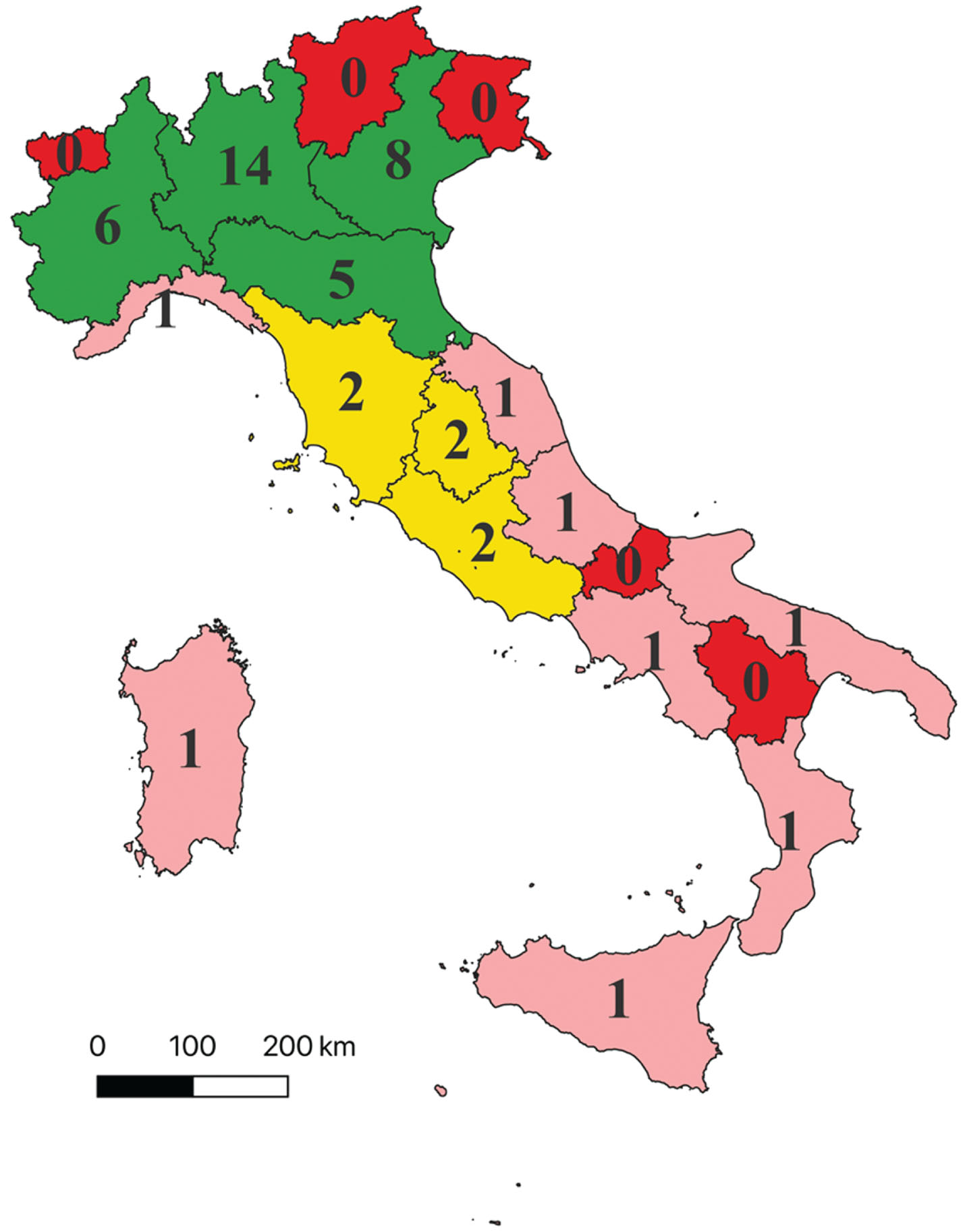

Out of 450 CCDDs, 47 (10.4%) met the requirements for effective DMT prescription. Notably, the majority of CCDDs with elective characteristics for DMT prescription are situated in Northern Italy (Fig. 1). CCDDs that meet the requirements are lacking in five regions (i.e., Basilicata, Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, Molise, Trentino Alto Adige, and Valle d’Aosta) totaling an estimated 64,970 PwD and 53,290 people with MCI who do not have access to such centers in their region (Supplementary Table 1). Among Italian regions, there is significant variability in the estimated number of cases per center with potential prescribing capabilities (cases/CCDD meeting requirements), ranging for dementia from a minimum of 9,736 (Umbria) to a maximum of 81,159 (Sicily) and for MCI from a minimum of 7,539 (Umbria) to a maximum of 79,104 (Campania). Among regions with at least one CCDD meeting elective criteria, those with a better proportion of estimated cases per CCDD (first quartile) are Umbria, Veneto, Lombardia, and Piemonte; followed by Emilia-Romagna, Abruzzo, Sardegna, and Marche (second quartile); Calabria, Liguria, and Toscana (third quartile); the regions with a poorer proportion are Lazio, Puglia, Campania, and Sicilia (fourth quartile) (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1

Distribution of Italian CCDDs encountering requirements for effective disease-modifying therapies prescription. The figure displays the distribution of the 47 CCDDs that meet the specified requirements for effective prescription of disease-modifying therapies. These requirements include a multidisciplinary team, a minimum core test for neuropsychological assessment, amyloid PET, CSF, and Brain MRI assessment. Legend: – Red: Indicates regions with no CCDDs meeting the elective requirements. – Pink: Represents regions with 1 CCDD meeting the elective requirements (first and second quartile of the distribution, excluding regions without elective CCDDs). – Yellow: Denotes regions with 2 CCDDs meeting the elective requirements (third quartile of the distribution, excluding regions without elective CCDDs). – Green: Signifies regions with more than 2 CCDDs meeting the elective requirements (fourth quartile of the distribution, excluding regions without elective CCDDs).

Univariate comparison

Univariate comparison between the groups with (“presence”) and without (“absence”) requirements for effective prescription reveals significant differences in variables across all the three presented categories. Regarding “Organizational features and activity profile”, CCDDs that met the criteria are more frequently located in Northern Italy, in a university setting, more commonly operate for more than 15 hours weekly, have the presence of more than 2 additional professionals beyond the multidisciplinary team, a computerized archive, an ICP, and a median number of patients exceeding 500. In contrast, CCDDs not meeting the criteria are more frequently located in the South and Islands and a territorial setting. Concerning “Services provided to patients”, the two groups exhibit significant differences in the provision of blood tests, ECG, SPECT, genetic testing, plasma markers, functional neuroimaging, day hospital and telemedicine services, which are more frequently utilized in CCDDs that meet the considered requirements. In the latter, the rehabilitation, both motor and speech and language, the activity of secondary prevention on MCI patients and contact with family associations and third sector organizations is more frequently provided. Concerning “Continuing professional development and counselling services offered in the care phase”, CCDDs that meet the elective characteristics more frequently offer individual counselling and informational activities for family members and caregivers, in addition to providing training and professional updating activities (see Table 1).

Table 1

Comparison of CCDDs according to presence or absence of requirements for Effective Prescription of disease-modifying therapies

| Presence N = 47 | Absence N = 403 | p | |

| Group 1: Organizational features and activity profile | |||

| Italian macro-area, n (%) | |||

| North | 34 (72.3%) | 168 (41.7%) | <0.001 |

| Center | 7 (14.9%) | 75 (18.6%) | |

| South | 6 (12.8%) | 160 (39.7%) | |

| Setting, n (%) | |||

| Territorial | 8 (17.0%) | 192 (47.6%) | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 29 (61.7%) | 179 (44.4%) | |

| University | 10 (21.3%) | 32 (7.9%) | |

| CCDD opening h/week, n (%) | |||

| <15 h | 11 (23.4%) | 212 (52.6%) | <0.001 |

| ≥15 h | 36 (76.6%) | 191 (47.4%) | |

| Length of activity of the facility, years, median (IQR) | 18 (13–23) | 17 (12–22) | 0.221 |

| N° of professionals in the staff beyond physicians and psychologists/neuropsychologists, n (%) | |||

| 0–1 | 12 (25.5%) | 258 (64.0%) | <0.001 |

| 2+ | 35 (74.5%) | 145 (36.0%) | |

| Availability of computerized archive, n (%) | 36 (76.6%) | 178 (44.2%) | <0.001 |

| Availability of a ICPs (Region, Hospital, Health Local Service, district level), n(%) | |||

| No | 15 (31.9%) | 172 (42.7%) | 0.010 |

| Yes | 32 (68.1%) | 192 (47.6%) | |

| NA | 0 (0%) | 39 (9.7%) | |

| Existence of waiting list to access the services, n (%) | |||

| No | 5 (10.6%) | 65 (16.1%) | 0.343 |

| Yes | 41 (87.2%) | 316 (78.4%) | |

| NA | 1 (2.1%) | 22 (5.5%) | |

| Average time spent per patient for a control visit, min, median (IQR) | 30 (30–30) | 31 (30–30) | 0.977 |

| Number of patients in charge annually visited, n (%) | |||

| <500 | 10 (21.3%) | 174 (43.2%) | 0.005 |

| > =500 | 29 (61.7%) | 155 (38.5%) | |

| NA | 8 (17.0%) | 74 (18.4%) | |

| Group 2: Services provided to patients | |||

| ECG and cardiological examination | 46 (97.9%) | 336 (83.4%) | 0.009 |

| Blood tests | 45 (95.7%) | 326 (80.9%) | 0.011 |

| CT scan | 46 (97.9%) | 320 (79.4%) | 0.002 |

| EEG | 47 (100.0%) | 304 (75.4%) | <0.001 |

| EEG with brain connectivity assessment | 21 (44.7%) | 129 (32.0%) | 0.081 |

| SPECT | 41 (87.2%) | 273 (67.7%) | 0.006 |

| Genetic testing | 43 (91.5%) | 211 (52.4%) | <0.001 |

| Plasma markers | 36 (76.6%) | 186 (46.2%) | <0.001 |

| Functional neuroimaging | 29 (61.7%) | 164 (40.7%) | 0.006 |

| Day hospital | 35 (74.5%) | 207 (51.4%) | 0.003 |

| Ordinary hospitalization | 40 (85.1%) | 257 (63.8%) | 0.003 |

| Cognitive rehabilitation | 37 (78.7%) | 266 (66.0%) | 0.079 |

| Motor rehabilitation | 35 (74.5%) | 231 (57.3%) | 0.024 |

| Speech and language rehabilitation | 36 (76.6%) | 213 (52.9%) | 0.002 |

| Occupational rehabilitation | 25 (53.2%) | 179 (44.4%) | 0.253 |

| Cognitive telerehabilitation | 15 (31.9%) | 89 (22.1%) | 0.130 |

| Motor telerehabilitation | 10 (21.3%) | 68 (16.9%) | 0.450 |

| Digital rehabilitation tools | 14 (29.8%) | 77 (19.1%) | 0.084 |

| Alzheimer’s café | 31 (66.0%) | 177 (43.9%) | 0.004 |

| Meeting center | 16 (34.0%) | 89 (22.1%) | 0.067 |

| Mindfulness | 7 (14.9%) | 62 (15.4%) | 0.930 |

| Art therapy | 13 (27.7%) | 113 (28.0%) | 0.956 |

| Sensory stimulation | 9 (19.2%) | 74 (18.4%) | 0.895 |

| Reminiscence therapy | 18 (38.3%) | 112 (27.8%) | 0.133 |

| Reality orientation therapy | 18 (38.3%) | 135 (33.5%) | 0.511 |

| Validation therapy | 12 (25.5%) | 112 (27.8%) | 0.743 |

| Psychotherapy | 28 (59.6%) | 186 (46.2%) | 0.081 |

| Behavioral therapy | 19 (40.4%) | 164 (40.7%) | 0.972 |

| Telemedicine | 31 (66.0%) | 175 (43.4%) | 0.003 |

| Telecare service | 10 (21.3%) | 100 (24.8%) | 0.593 |

| Use of digital tools for remote monitoring | 14 (29.8%) | 90 (22.3%) | 0.251 |

| Home visits | 23 (48.9%) | 227 (56.3%) | 0.335 |

| Secondary prevention activities on MCI Patients | 39 (83.0%) | 233 (57.8%) | 0.001 |

| Integrated home care | 33 (70.2%) | 265 (65.8%) | 0.541 |

| Day services | 33 (70.2%) | 252 (62.5%) | 0.301 |

| Residential service | 33 (70.2%) | 264 (65.5%) | 0.519 |

| Respite hospitalization | 34 (72.3%) | 231 (57.3%) | 0.048 |

| Transport service | 20 (42.6%) | 163 (40.4%) | 0.781 |

| Telephone listening points | 22 (46.8%) | 184 (45.7%) | 0.881 |

| Contacts with family associations | 42 (89.4%) | 255 (63.3%) | <0.001 |

| Contacts with third sector organizations | 30 (63.8%) | 195 (48.4%) | 0.045 |

| Percentage of patients with dementia that received an antipsychotics prescription in the last year, median (IQR) | 30% (20–50) | 30% (20–40) | 0.604 |

| Group 3: Continuing professional development and counselling services offered in the care phase | |||

| Individual patient counselling | 41 (87.2%) | 322 (79.9%) | 0.228 |

| Patient and family counselling | 44 (93.6%) | 339 (84.1%) | 0.083 |

| Individual counselling for family members and caregivers | 45 (95.7%) | 317 (78.7%) | 0.005 |

| Informational activities for family members and caregivers | 46 (97.9%) | 347 (86.1%) | 0.022 |

| Legal aid promotion | 29 (61.7%) | 213 (52.8%) | 0.250 |

| Legal support | 32 (68.1%) | 218 (54.1%) | 0.068 |

| Training and professional updating activities | 43 (91.5%) | 253 (62.8%) | <0.001 |

ICPs: integrated care pathways; NA not available information.

Characteristics of CCDDs linked to prescriptive capability

Regarding the multivariable analysis involving variables describing organizational features and activity profile of the structure, CCDDs located within a university and those with a higher number of weekly opening hours showed a higher probability of meeting the requirements for effective DMT prescription (OR: 7.22 for CCDDs located within a university vs territorial facility; OR: 3.79 for CCDDs with more than 15 h/week compared to those with fewer hours) (Table 2). Similarly, facilities with a computerized archive available and those that followed an ICP during their operations were found associated with a higher chance of meeting criteria (OR: 3.11 for CCDDs with a computerized archive vs those who had not; OR: 2.42 for CCDDs with ICPs compared to those without). Facilities with a working staff consisting of 2 or more professionals beyond physicians and psychologists were identified as having a higher probability of meeting criteria (OR: 4.34 for CCDDs with more or equal to 2 professionals compared to facilities with less than 2) (Table 2).

Table 2

Characteristics (first group) associated with the presence of requirements for Effective Prescription of disease-modifying therapies at univariable and multivariable analysis. In bold significant variables in the multivariable logistic regression model. OR, odds ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, confidence interval

| OR | 95% CI | p | AOR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Group 1: Organizational features and activity profile | ||||||||

| Italian macro-area | ||||||||

| North | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Center | 0.46 | 0.20 | 1.09 | 0.077 | 0.75 | 0.28 | 2.00 | 0.570 |

| South | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.45 | <0.001 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 1.29 | 0.141 |

| Setting | ||||||||

| Territorial | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Hospital | 3.89 | 1.73 | 8.73 | 0.001 | 4.97 | 1.97 | 12.56 | 0.001 |

| University | 7.50 | 2.75 | 20.43 | <0.001 | 7.22 | 2.26 | 23.09 | 0.001 |

| CCDD opening hours/week | ||||||||

| < =15 h | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| >15 h | 3.63 | 1.80 | 7.34 | <0.001 | 3.79 | 1.61 | 8.84 | 0.002 |

| N° of professionals in the staff beyond physicians and psychologists/neuropsychologists | ||||||||

| 0–1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2+ | 5.19 | 2.61 | 10.31 | <0.001 | 4.34 | 2.00 | 9.43 | <0.001 |

| Availability of computerized archive | 4.14 | 2.05 | 8.36 | <0.001 | 3.11 | 1.42 | 6.80 | 0.005 |

| Availability of a ICPs (Region, Hospital, Health Local Service, district level) | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.91 | 1.00 | 3.65 | 0.050 | 2.42 | 1.12 | 5.23 | 0.025 |

| NA | NE | NE | ||||||

| Number of patients in charge annually visited | ||||||||

| <500 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| > =500 | 3.26 | 1.54 | 6.90 | 0.002 | 1.19 | 0.48 | 2.97 | 0.709 |

| NA | 1.88 | 0.71 | 4.96 | 0.201 | 2.35 | 0.80 | 6.90 | 0.120 |

*ICPs: integrated care pathways; NA not available information; NE not estimable due to categories without event.

The presence of the provision of genetic testing showed a higher probability of meeting the criteria (OR: 5.68). Facilities that have contacts with family associations showed a three-fold higher probability of meeting effective prescription requirements with a trend toward statistical significance (OR: 3.02) (Table 3).

Table 3

Characteristics (second group) associated with the presence of requirements for Effective Prescription of disease-modifying therapies at univariable and multivariable analysis. In bold significant variables in the multivariable logistic regression model. OR, odds ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, confidence interval

| OR | 95% CI | p | AOR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Group 2: Services provided to patients | ||||||||

| Blood tests | 5.31 | 1.26 | 22.39 | 0.023 | 0.96 | 0.17 | 5.38 | 0.964 |

| ECG and cardiological examination | 9.17 | 1.24 | 67.67 | 0.030 | 3.22 | 0.32 | 32.54 | 0.321 |

| SPECT | 3.25 | 1.35 | 7.86 | 0.009 | 0.68 | 0.23 | 2.03 | 0.488 |

| Genetic testing | 9.78 | 3.45 | 27.76 | <0.001 | 5.68 | 1.55 | 20.90 | 0.009 |

| Plasma biomarkers | 3.82 | 1.89 | 7.71 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 0.50 | 2.80 | 0.706 |

| Functional neuroimaging | 2.35 | 1.26 | 4.37 | 0.007 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 2.44 | 0.849 |

| Day hospital | 2.76 | 1.39 | 5.47 | 0.004 | 0.97 | 0.38 | 2.46 | 0.950 |

| Ordinary hospitalization | 3.25 | 1.42 | 7.43 | 0.005 | 0.92 | 0.29 | 2.88 | 0.879 |

| Telemedicine | 2.52 | 1.34 | 4.76 | 0.004 | 1.27 | 0.61 | 2.66 | 0.528 |

| Motor Rehabilitation | 2.17 | 1.10 | 4.31 | 0.026 | 0.73 | 0.25 | 2.20 | 0.581 |

| Speech and language rehabilitation | 2.92 | 1.45 | 5.90 | 0.003 | 1.53 | 0.49 | 4.70 | 0.462 |

| Alzheimer’s Cafè | 2.47 | 1.31 | 4.67 | 0.005 | 1.30 | 0.61 | 2.74 | 0.496 |

| Secondary prevention activities on MCI patients | 3.56 | 1.62 | 7.81 | 0.002 | 1.80 | 0.73 | 4.42 | 0.203 |

| Contacts with family associations | 4.88 | 1.89 | 12.59 | 0.001 | 3.02 | 0.97 | 9.43 | 0.057 |

| Contacts with third sector organizations | 1.88 | 1.01 | 3.52 | 0.048 | 0.52 | 0.22 | 1.20 | 0.125 |

Concerning the third group of variables related to continuing professional development and counselling services offered in the care phase, the CCDDs that provided training and professional updating activities showed a higher probability of meeting the criteria (OR: 4.61) (Table 4).

Table 4

Characteristics (third group) associated with the presence of criteria. In bold significant variables in the multivariable logistic regression model. OR, odds ratio; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI, confidence interval

| OR | 95% CI | p | AOR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Group 3: Continuing professional development and counselling services offered in the care phase | ||||||||

| Individual counselling for family members and caregivers | 6.10 | 1.45 | 25.00 | 0.014 | 2.65 | 0.57 | 12.19 | 0.212 |

| Informational activities for family members and caregivers | 7.42 | 1.00 | 54.90 | 0.050 | 2.77 | 0.34 | 22.78 | 0.345 |

| Training and professional updating activities | 6.37 | 2.24 | 18.11 | 0.001 | 4.61 | 1.59 | 13.42 | 0.005 |

DISCUSSION

The present work is an in-depth study of the activities of the Italian CCDDs, conducted within the framework of the Fund for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias.31 The specific objective was to assess the current state of preparedness of the facilities for the accurate prescription of the potentially upcoming DMTs during the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. This research involved the Italian National Institute of Health with the collaboration of representatives from the Regions and Autonomous Provinces that are part of the Permanent National Table on Dementia. The strength of this study lies in its reliance on the CCDD data derived from a national survey, which achieved an 84% response rate.26 This approach provides an accurate snapshot of the current Italian landscape, as reported by center administrators. Based on published clinical trials, FDA prescribing guidelines, and appropriate use recommendations from expert clinicians9–12, we propose the minimum requirement for the accurate selection of PwD who could potentially gain benefits from the use of DMTs. These requirements include the presence of a multidisciplinary team, the implementation of neuropsychological MCT, and the provision of amyloid PET, CSF and Brain MRI assessment.

The first striking result is that very few (10.4%) CCDDs in Italy currently meet the three minimum requirements for an effective prescription of DMTs. Additionally, a clear geographical disproportion is observed, with approximately 70% (33/47) of these facilities located in only four regions of Northern Italy. The necessity to organize CCDDs into different levels of complexity and competence is practiced in other countries, for example, France,32 Germany,33 and the United Kingdom.34 It has also been advised in Italy35 through a proposal for a reorganization of dementia healthcare services into Community Center, a basic point of contact for individuals with cognitive disorders and dementia in the community; First-Level center, equipped to handle a wider range of services, with a multidisciplinary team, 1.5 T MRI scanner, CSF, and genetic assessments; Second-Level Center, the highest level of care equipped and staffed to provide advanced diagnosis, treatment, and management of dementia; and Prescribers Centers that should be further equipped with specialized pharmacy services, an outpatient clinic for intravenous infusion of medications, an emergency room for acute care needs, and training and updating programs for professionals working at the center.35 In this study, we identified the presence of at least two levels of care regarding the CCDDs in Italy. Specifically, the few CCDDs that would meet the requirements for effective prescription of DMTs are also characterized by longer opening hours, a higher number of professionals, a university location, availability of an ICP for dementia, as well as a higher frequency of conducting genetic tests, direct contacts with family associations, and continuous training programs for professionals. On the contrary, the other CCDDs more frequently have a territorial location, with fewer opening hours and a lower median number of patients. Additionally, they have access to a significantly lower number of diagnostic tests, while not differing significantly in terms of the frequency of non-pharmacological treatments. The characterization of CCDDs without the considered requirements aligns more closely with the definition of Community Centers in the classification by Filippi et al.35 Although Italy has a greater number of memory clinics than France, Germany and the UK,32–34 there is a need for a profound reorganization of these facilities by dividing them into those that have a predominantly diagnostic action for DMT from those that are mainly aimed at psychosocial, educational and rehabilitation interventions. It is important to underline that only a small proportion of patients with MCI or mild AD will be candidates for the prescription of DMTs, but this opportunity should be guaranteed in every region and autonomous province. In terms of public health, the entire Italian CCDD network must be reorganized and strengthened for all patients (MCI and dementia) as reported in the previous paper.26

The regional distribution of CCDDs meeting the requirements reflects the performance scores of different Italian regions and autonomous provinces in satisfying health Essential Levels of Assistance/care (Livelli Essenziali di Assistenza, LEA).36 This assessment measures three healthcare dimensions (e.g., prevention, community health services, and hospital assistance) using indicators established by the Italian Ministry of Health. The disparities in the presence of CCDDs potentially prescribing for DMT are pronounced between the North and South of the country. Specifically, Lombardia, Piemonte, and Veneto (Northern Italy) are identified as regions with the best proportion between estimated cases and CCDDs with potential prescription capabilities. In contrast, Puglia, Campania, and Sicilia (Southern Italy and Islands) exhibit the most disadvantageous proportion. However, as also highlighted regarding the LEA grid, the complete absence of service extends beyond the North-South inequity.36 In four regions and two autonomous provinces located in the Northeast (Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, autonomous provinces of Trento and Bolzano), Northwest (Val d’Aosta), and Southern Italy (Basilicata and Molise), CCDDs with prescribing requirements are completely absent. Although the estimated presence of cases in Basilicata, Molise, and Val d’Aosta is the lowest, consistent with their total resident population, this implies necessary inter-regional displacement for citizens who could potentially benefit from an effective diagnosis and prescription of new DMTs. Further consideration is warranted for the situation in Friuli-Venezia-Giulia and Trentino Alto Adige, where the estimated number of cases exceeds that of regions such as Abruzzo or Umbria, yet not a single CCDD potentially prescribing is available. A common characteristic of these territories is the presence of rural and mountainous areas, rendering citizen mobility challenging, thereby likely depriving them of an essential service for individuals with early-stage AD.

Based on the emerging data, it can be argued that a reorganization of the CCDDs network may be necessary, starting from the enhancement of the various competencies already present in the different services. Similarly to the United Kingdom,37 in Italy too, in fact, the dementia services (CCDDs) that will be able to prescribe DMT drugs are few and not uniformly distributed throughout the national territory. Italy has the highest proportion of older adults in Europe,38 posing the challenge of striking a sustainable balance between financial considerations and the quality of healthcare services. With the market entry of new DMT in Italy, the current organization of CCDDs may struggle to meet the demand for a higher number of early and accurate diagnoses, putting many individuals at risk of not receiving a prescription although PwD who will be able to take the DMT will be few compared to the total number of patients managed by the Italian CCDDs.14

A short-term challenge for health policymakers is ensuring equitable care for all citizens, regardless of their region of residence. Decreasing regional disparities would simultaneously reduce inequities.36 A fundamental necessity is to increase the number of CCDDs with prescribing potential, and a crucial first step is the recruitment of a multidisciplinary team, which includes at least two specialized medical professionals among geriatricians, neurologists, and psychiatrists, and at least one psychologist or neuropsychologist. Although the professional figure of the psychologist or neuropsychologist remains the one with the lowest percentage of permanent employment in CCDDs,26,39 the utilization of a neuropsychological MCT is a direct outcome of hiring psychologists at CCDDs28 (Vaccaro et al., unpublished data). Furthermore, from a public health perspective, it is essential to train all CCDDs staff who will prescribe DMT to understand the risk-benefit profile and the management of PwD who will take these new molecules. This necessity has been underscored by other European countries,40 and we stress its significance in the context of Italy as well.

To enhance the readiness of the national healthcare system to conduct accurate diagnoses and effective prescriptions of upcoming DMTs, it is necessary to increase the number of CCDDs with a multidisciplinary team. Furthermore, allowing a greater number of CCDDs to perform CSF, PET amyloid, and Brain MRI tests will help achieve the objective. Finally, a national training plan for all health professionals most involved in the diagnosis and care of PwD who will take these new drugs is urgent.

It is evident based on the current distribution of CCDDs who could potentially prescribe the new drugs that a more assertive action is required in regions where the presence of CCDDs with prescribing potential is inadequate, favoring the enhancement of existing services in those areas or activating inter-regional collaborative agreements.

Finally, from a public health perspective, greater integration and collaboration between all services involving people with dementia, from primary care to specialist centers, as part of effective and efficient ICP, appears urgent also with a view to including a hub-spoke model as suggested by the Interceptor project.29,41

Findings from this study should be interpreted cautiously due to certain limitations. Information about CCDD characteristics relies on self-reported statements obtained through a national survey, which could be influenced by social desirability bias or inaccurate reporting. However, when it comes to gathering “objective” data like staff composition and the use of neuropsychological tests or instrumental examinations, it is less likely that inaccurate information has been provided. Additionally, the methodology of analyzing responses from a national survey with a high response rate aligns to accurately assess the current preparedness of CCDDs, and acquire detailed information directly from the center’s responsible parties.

Conclusion

The challenges ahead are not without solutions, as demonstrated by experiences in other medical specialities.42 For instance, various oncological treatments may require specialized facilities for infusions, imaging services, and genetic or laboratory tests. With continued funding for neurological research, further breakthroughs could lead to the approval of additional therapies soon, making the management of AD easier through the introduction of blood-based biomarkers, streamlined neuroimaging procedures, and the safer administration of monoclonal antibodies via subcutaneous injection. With the anticipated arrival of new DMTs in Italy, the current organization of CCDDs may struggle to meet the demand for a higher number of early and accurate diagnoses, putting many individuals at risk of not receiving a prescription. Healthcare systems must be prepared to adapt accordingly. The situation described in Italy might be similar to other countries. The implementation of national plans in various countries often falls short in addressing the early detection and timely diagnosis of AD, focusing more on post-diagnosis support.43 National dementia plans need to prioritize early detection and diagnosis of AD to align with current innovations. This will require raising awareness about the importance of innovation in this area, with active support from those directly affected, from diagnosis to treatment. Attention needs to be paid also to formal and informal caregivers, from continuous education programs to specific support. Securing full funding for national plans remains a challenge in many countries. The national healthcare systems worldwide need to move beyond merely developing plans to ensuring they are fully funded for implementation.44 Furthermore, they must adapt to the emergence of DMTs and ensure equitable access.45

Permanent Table of the National Dementia Plan Study Group

Arabia Gennarina (Catanzaro), Amorosi Alessandro (Milano), Bacigalupo Ilaria (Roma), Bargagli Anna Maria (Roma), Bartorelli Luisa (Roma), Basso Cristina (Padova), Berardinelli Manuela (Roma), Bernardi Maria Pompea (Catanzaro), Bianchi Caterina B.N.A (Roma), Blandi Lorenzo (Pavia), Boschi Federica (Bologna-Ravenna-Modena), Bruni Amalia Cecilia (Lamezia Terme (CZ)), Caci Alessandra (Aosta), Caffarra Paolo (Parma), Canevelli Marco (Roma), Capasso Andrea (Napoli), Cipollari Susanna (Macerata-Roma), Cozzari Mariapia (Giovinazzo (BA)), Di Costanzo Alfonso (Campobasso), Di Fiandra Teresa (Roma), Di Palma Annalisa (Napoli), Fabbo Andrea (Bologna-Modena), Francescone Federica (Roma), Gabelli Carlo (Padova), Gainotti Sabina (Roma), Galeotti Francesca (Roma), Gambina Giuseppe (Verano), Gasparini Marina (Roma), Giannini Maria Assunta (Roma), Gilli Micaela (Trento), Giordano Marcello (Palermo), Greco Annarita (Napoli), Guaita Antonio (Abbiategrasso (MI)), Izzicupo Fabio (Senigallia (AN)), Landoni Fiammetta (Roma), Lidonnici Elisa (Genova), Locuratolo Nicoletta (Roma), Logroscino Giancarlo (Bari-Tricase (LE)), Lombardi Alessandra (Trento), Losito Gilda (Roma), Lubian Francesca (Bolzano), Lupinetti Maria Cristina (Pescara), Madrigali Sara (Firenze), Marra Camillo (Roma), Masera Filippo (Ancona), Massaia Massimiliano (Torino), Mastromattei Antonio (Roma), Matera Antonio (Potenza), Matera Manlio (Sesto Fiorentino (FI)), Mazzoleni Francesco (Sondrio), Melani Carla (Bolzano), Meloni Serena (Cagliari), Memeo Elena (Bari), Musso Marco (Torino), Notarelli Antonella (Firenze), Onofrj Marco (Pescara), Palummeri Ernesto (Genova), Panetta Valeria (Potenza), Petrini Carlo (Roma), Piccoli Tommaso (Palermo), Pirani Alessandro (Ferrara), Piras Stefano (Cagliari), Porro Gabriella (Milano), Possenti Mario (Milano), Rendina Elena (Roma), Riolo Antonino (Trieste), Riva Luciana (Roma), Salvi Emanuela (Roma), Santini Sara (Pescara), Scalmana Silvia (Roma), Scarpelli Nando (Perugia), Secreto Piero (Torino), Seganfreddo Monica (Aosta), Sensi Stefano (Chieti-Pescara), Severino Carla (Campobasso), Spadin Patrizia (Milano), Spallino Patrizia (Torino), Spinelli Anna Laura (Spoleto), Stracciari Andrea (Bologna), Trabucchi Marco (Roma), Vanacore Nicola (Roma), Zaccardi Antonio (Trieste).

The CCDDs Study Group

Accardo Egidio (Napoli), Ahmad Omar (Alghero, Sassari), Ajena Domenico (Legnago), Alba Giovanni (Agrigento), Albanese Alberto (Rozzano), Albergati Andrea (Pavia), Alessandria Maria (Martano), Alfieri Pasquale (Pomigliano d’Arco), Alimenti Mario (Roma), Aliprandi Angelo (Lecco), Altavilla Roberto (Casalpusterlengo), Amarù Salvatore (Rivoli), Ambrosino Immacolata (Nola), Amideo Felice (Sarno), Ammendola Stefania (Napoli), Amoruso Francesco (Torre del Greco), Andreati Candida (Portomaggiore), Andreone Vincenzo (Napoli), Angeloni Rossano (Montegranaro), Annunziata Francesco (Pompei), Antenucci Sara (Ortona), Appollonio Ildebrando (Monza), Arabia Gennarina (Catanzaro), Arcudi Luciano (Reggio di Calabria), Ardillo Marianna (Castrovillari), Arena Maria Carmela Gabriella (Acireale), Arighi Andrea (Milano), Arpino Gennaro (Ercolano), Bagalà Anna (Palmi), Baiano Antonio (Pozzuoli), Balestrino Antonio (Parma), Barbagallo Mario (Palermo), Barbuto Marianna (Treviglio), Bargnani Cesare (Ome), Barone Paolo (Salerno), Bartoli Antonella (Urbino), Bauco Claudia (Aquino, Cassino), Bellelli Giuseppe (Monza), Bellini Marco Antonio (Siena), Bellora Aldo (Alessandria), Benati Giuseppe (Forli’), Beretta Sandro (Vimercate), Bergamini Lucia (Mirandola), Bergonzini Eleonora (Guastalla), Bessi Valentina (Firenze), Bianchetti Angelo (Brescia), Bisio Erika (San Maurizio Canavese), Boiardi Roberta (Castelnovo Ne’ Monti), Bollani Elisabetta (Piombino), Bologna Laura (Santorso), Bolzetta Francesco (Dolo, Noale), Boni Stefano (Faenza, Lugo), Borgogni Tiziano (Castel Del Piano), Bottini Gabriella (Milano), Bottone Ida (Chieti), Bove Angela (Napoli), Bruno Bossio Roberto (Cosenza), Bruno Giuseppe (Roma), Bruno Patrizia (Giugliano in Campania), Bucca Carmela (Frosinone), Buganza Manuela (Trento), Buzzi Graziano (Montevarchi), Buzzi Paolo (Suzzara), Cacchio’ Gabriella (Ascoli Piceno), Cafarelli Arturo (Bondeno), Cafazzo Viviana (Jesi), Caggiula Marcella (Lecce), Cagnin Annachiara (Padova), Calabrese Gianluigi (Casarano), Calabrese Giusi Alessandro (Terni), Calandra Maria (San Giorgio Del Sannio), Caleri Veronica (Pistoia), Calvani Donatella (Prato), Camerlingo Massimo (Osio Sotto), Cantello Roberto (Novara), Capasso Andrea (Caivano), Capellari Sabina (Bologna), Capobianco Giovanni (Roma), Capoluongo Maria Carmela (Capua), Cappelletti Rossana (Colle di Val D’elsa, Poggibonsi), Capra Claudio (Sanluri), Caravona Natalia (Corigliano-Rossano), Stucchi Carlo Maria (Mantova), Carluccio Maria Alessandra (Poggibonsi), Carteri Severina (Melito di Porto Salvo), Casanova Anna (Trento), Caserta Francescosaverio (Napoli), Caso Paolo (Capaccio), Cassaniti Gaetana (Caltagirone), Cassetta Emanuele (Roma), Casson Silvia (Chioggia), Castiello Vincenzo (Torre Annunziata), Cattaruzza Tatiana (Trieste), Ceccon Anna (Camposampiero), Ceci Moira (Rovigo), Cella Sabatino (Avellino), Cenciarelli Silvia (Citta’ di Castello, Gubbio), Censori Bruno (Cremona), Cerqua Giuliano (Castel Volturno), Cerrone Paolo (Teramo), Cervera Pasquale (Napoli), Chemotti Silvia (Tione di Trento), Chiari Annalisa (Modena), Chiloiro Roberta (Conversano), Cirilli Luisa (Conegliano), Clerici Raffaella (Como), Coin Alessandra (Padova), Colacino Gianfranco (Pontecagnano Faiano), Colacioppo Francesco Paolo (Lanciano), Colao Rosanna (Lamezia Terme), Colin Antonio (Portici), Coluccia Brigida (Lecce), Conti Giancarlo Maria (Cinisello Balsamo), Coppola Filomena (San Giorgio a Cremano), Coppola Francesca (Fabriano), Corbo Massimo (Milano), Cossu Antonello (Ghilarza), Costa Alfredo (Pavia), Costa Gabriella (Piove Di Sacco), Costa Manuela (Carpi), Cotelli Maria Sofia (Esine), Cottone Salvatore (Palermo), Cozzolino Maria Immacolata (Civitavecchia), Crucitti Andrea (Gavardo), Cumbo Eduardo (Caltanissetta), Currà Antonio (Terracina), Dallocchio Carlo (Voghera), D’amico Ferdinando (Patti), D’Amore Anna (Caserta), De Carolis Stefano (Cesena, Savignano sul Rubicone), De Donato Maurizio (Salerno), De Feo Paola (Portoferraio), De La Pierre Franz (Aosta), De Laurentiis Maria (Vasto), De Lauretis Ida (Teramo), De Luca Gian Placido (Messina), De Palma Alessandro (Massa Marittima), De Togni Laura (Bussolengo, San Bonifacio, Verona), Demontis Antonio (Lanusei), D’Epiro Dora (Cosenza), Desideri Giovambattista (Avezzano), Desiderio Miranda (Vasto), Di Donato Marco (Citta’ Sant’Angelo), Di Emidio Gabriella (Sant’Egidio alla Vibrata), Di Giacopo Raffaella (Riva Del Garda, Rovereto), Di Lazzaro Vincenzo (Roma), Di Leo Rita (Venezia), Di Marco Salvatore (Lagosanto), Di Quarto Gaetano (Massafra), Dijk Babette (Chiavari), Dikova Natasa (Borgonovo Val Tidone), Dioguardi Maria Stefania (Terni), Dominici Federica (Montepulciano), Dotta Michele (Verduno), Dotti Carla (Cesano Boscone), Esposito Domenica (Cervinara), Esposito Sabrina (Napoli), Esposito Zaira (Negrar), Ettorre Evaristo (Roma), Fabbo Andrea (Modena), Faccenda Giovanna (Macerata), Falanga Angelamaria (Roma), Falorni Michela (Lucca), Falvo Fraia (Sant’Angelo Lodigiano), Fappani Agostina (Leno), Farina Elisabetta Ismilde Mariagiovanna (Milano), Fascendini Sara (Gazzaniga), Fattapposta Francesco (Roma), Favatella Irene (Palermo) Femminella Grazia Daniela (Napoli), Ferrara Salvatore (Siracusa), Ferrari Patrizia (Scandiano), Ferraris Alessandra (Casale Monferrato), Ferraro Franco (Ariano Irpino), Ferri Raffaele (Troina), Ferrigno Salvatore (Maiori), Filastro Francesco (Girifalco), Filippi Massimo (Milano), Finelli Antonio (Telese Terme), Finelli Chiara (Montecchio Emilia), Fiori Maria Rita (Senorbi’), Fiorillo Francesco (San Cipriano d’Aversa), Floris Gianluca (Monserrato), Fontanella Anna (Milano), Forgione Luigi (Villaricca), Foti Andrea (Roma), Foti Francesca Fulvia (Scilla), Frediani Fabio (Milano), Frontera Giovanni (Catanzaro), Fulgido Maria Luigia (Nardo’), Fundarò Cira (Pavia), Fuschillo Carmine (Volla), Gabbani Luciano (Firenze), Gabelli Carlo (Selvazzano Dentro), Galati Franco (Vibo Valentia), Galli Renato (Pontedera), Gallo Angelo (Corigliano-Rossano), Gallo Livia (Venezia), Gallucci Maurizio (Treviso), Galluccio Gabriella (Albano Laziale), Gareri Pietro (Catanzaro), Gasperi Lorenzo (Borgo Valsugana), Gelmini Giovanni (Langhirano, Borgo Val Di Taro), Gennuso Michele (Brescia), Gerace Carmela (Roma), Ghersetti Daria (Trieste), Giambattistelli Federica (Cremona), Giantin Valter (Bassano Del Grappa), Giordano Bernardo (Cava De’ Tirreni), Giorelli Maurizio (Barletta), Giorgianni Agata (Ragusa), Giubilei Franco (Roma), Godi Laura (Borgomanero), Gorelli Luciano (Abbadia San Salvatore, Sinalunga), Gragnaniello Daniela (Ferrara), Granziera Serena (Venezia), Greco Giuseppe (Orbetello), Grella Rodolfo (Teano), Grieco Michele (Matera), Grimaldi Luigi (Cefalù), Guarino Maria (Bologna), Guarnerio Chiara (Gallarate), Guidi Giovanni (Fano), Guidi Leonello (Empoli), Iallonardo Lucia (Fisciano), Iavarone Alessandro (Napoli), Ingegni Tiziana (Cortona), Insardà Pasqualina (Cinquefrondi), Ivaldi Claudio (Genova), Izzicupo Fabio (Senigallia), Labate Carmelo Roberto (Pinerolo), Lacava Roberto (Catanzaro), Lalli Francesco (Montecchio), Lammardo Anna Maria (Sala Consilina), Laurienzo Paolo Massimo (Campobasso), Leonardi Alessandro (Imperia), Leotta Maria Rosa (Mirano), Leuzzi Rosario (Messina), Linarello Simona (Bologna, Casalecchio Di Reno, Castenaso, Castiglione Dei Pepoli, Crevalcore,Porretta Terme, San Lazzaro Di Savena, San Pietro In Casale, Vergato), Litterio Pasqualino (Vasto), Lo Coco Daniele (Palermo), Lo Storto Mario Rosario (Padova), Logi Chiara (Camaiore), Logullo Francesco Ottavio (Fano), Lombardi Alessandra (Trento), Lombardi Fortunato (Napoli), Lorido Antonio (Bettola, Podenzano), Losavio Francesco Antonio (Saronno), Lubian Francesca (Bolzano), Luca Antonina (Catania), Ludovico Livia (Fontanellato, Busseto, Fidenza, Fornovo di Taro, San Secondo Parmense), Lunardelli Maria (Bologna), Lupo Mariarosaria (Cosenza), Luzzi Simona (Ancona), Maddestra Maurizio (Lanciano), Maio Gennaro (Benevento), Maiotti Mariangela (Foligno), Malagnino Anna Maria (Napoli), Mancini Giovanni (Roma), Manica Angela (Pergine Valsugana), Maniscalco Michele (Torino), Manni Barbara (Pavullo nel Frignano, Sassuolo), Manucra Antonio (Bobbio), Manzoni Laura (San Pellegrino Terme), Marabotto Marco (Cuneo), Marchesiello Giuseppe (Caserta), Marcon Michela (Arzignano, Vicenza), Marcone Alessandra (Milano), Marconi Roberto (Grosseto), Margiotta Alessandro (Ravenna), Marianantoni Angela (Terni), Mariani Donatella (Monza), Marino Gemma (Marano di Napoli), Marino Saverio (Castellammare di Stabia), Marinoni Vito (Ponderano), Marra Angela (Messina), Marra Camillo (Roma), Marrari Maria (Reggio di Calabria), Martelli Mabel (Imola), Marti Alessandro (Reggio nell’Emilia), Martorana Alessandro (Roma), Marvardi Martina (San Severino Marche), Mascolo Saverio (Potenza), Massimiliano Massaia Mario Bo (Torino), Massimo Lenzi Lucio (Napoli), Mastronuzzi Vita Maria Alba (Chiusi, Montepulciano), Mazzi Maria Letizia (Siena), Mazzone Andrea (Milano), Mecacci Rossella (Pescia), Mecocci Patrizia (Perugia), Medici Deidania (Ancona), Mei Daniele (Viterbo), Melandri Gian Giuseppe (Cervia), Melis Maurizio (Cagliari), Meneghello Francesca (Spinea), Menon Vanda (Modena), Menza Carmen (Pulsano), Merlo Paola (Bergamo), Milan Graziella (Napoli), Milia Antonio (Cagliari), Millia Calogero Claudio (Piazza Armerina), Minervini Sergio (Rovereto), Mobilia Carolina Anna (Aulla), Moleri Massimo (Bergamo), Molteni Elena (San Fermo della Battaglia), Moniello Giovanni (San Felice a Cancello), Montanari Stefano (Chiari), Mormile Maria Teresa (Acerra), Moro Giuseppe (Amantea), Moscato Gianluca (Livorno), Mossello Enrico (Firenze), Mundo Angela Domenica (Trebisacce), Mura Giuseppe (Olbia), Musca Fabio (Copertino), Musso Anna Maria (Verona), Nardelli Anna (Parma), Neviani Francesca (Modena), Nicosia Viviana (Orvieto), Nociti Vincenzo (Reggio di Calabria), Novelli Alessio (La Spezia), Nuccetelli Francesco (Guardiagrele), Onofrj Marco (Chieti), Orefice Lorenza (Arzano), Orsucci Daniele (Castelnuovo di Garfagnana), Pace Alfonso (Sapri, Centola), Paci Cristina (San Benedetto del Tronto), Padoan Roberta (Feltre), Padovani Alessandro (Brescia), Palleschi Lorenzo (Roma), Palmisani Maria Teresa (Tivoli), Palmucci Marco (Atri), Palumbo Pasquale (Prato), Panico Nadia Rita (Gagliano del Capo), Pansini Antonella (Atripalda), Pantieri Roberta (Bologna), Paolello Paolo (Cortemaggiore, Fiorenzuola d’Arda), Pardini Matteo (Genova), Parnetti Lucilla (Perugia), Parrotta Emma (Castrovillari), Passamonte Michela (Morbegno, Sondrio), Pastore Agostino (Albinea), Pastorello Ebe (Padova), Pelini Luca (Terni), Pellati Morena (Correggio), Pellegrino Mario (Aversa), Pellicano Clelia (Roma), Pelliccioni Giuseppe (Ancona), Pennisi Maria Giovanna (Catania), Perini Michele (Castellanza), Perotta Daniele (Rho), Persico Diego (Chieri), Petrella Virginia (Riccione, Rimini), Petri Fabia (Piacenza), Piccininni Maristella (Firenze), Pierguidi Laura (San Fermo della Battaglia), Pietrella Alessio (Roma), Pilotto Alberto (Genova), Pinto Patrizia (Bergamo), Pirani Alessandro (Cento), Pizza Vincenzo (Vallo della Lucania), Plantone Domenico (Siena), Plastino Massimiliano (Crotone), Poddighe Patrizia (Carbonia), Pomati Simone (Milano), Pompilio Angela (Taranto), Pontecorvo Marialuisa (Padova), Prelle Alessandro (Legnano), Previderè Giorgio (Abbiategrasso), Pucci Ennio (Pavia), Puoti Gianfrano (Napoli), Putzu Valeria (Cagliari), Rabasca Annaflavia (Sant’angelo dei Lombardi), Raffaele Massimo (Messina), Rainero Innocenzo (Torino), Rais Claudia (Cles, Mezzolombardo), Rana Michele (Gorizia), Ranzenigo Alberto (Cremona), Rea Giovanni (Nocera Inferiore), Righetti Enrico (Castiglione del Lago), Rinaldi Giuseppe (Bari), Rini Augusto (Brindisi), Rizzo Maria Rosaria (Napoli), Rizzo Massimo (Cosenza), Rocca Paola (Torino), Roffredo Laura (Acqui Terme), Roglia Daniela (Chivasso), Romagnoni Franco (Copparo), Romano Carlo (Torino), Romasco Annalisa (Venosa), Romeo Leonardo (Latina), Ronzoni Stefano (Roma), Rosci Chiara Emilia (Milano), Rosso Mara (Savigliano), Rozzini Renzo (Brescia), Ruberto Eleonora (Belluno), Ruberto Stefania (Cetraro), Rungger Gregorio (Brunico), Ruotolo Giovanni (Catanzaro), Russo Francesco (Frattamaggiore), Russo Giuseppe (Savona), Sabina Roncacci (Rieti), Sacco Simona (Avezzano), Sacilotto Giorgio (Milano), Salemi Giuseppe (Palermo), Salotti Paolo (Acquapendente, Civita Castellana, Soriano Nel Cimino, Tarquinia), Salvatore Elena (Napoli), Sambati Luisa (Bologna), Sanges Giuseppe (Palma Campania), Santamaria Francesco (Napoli), Santilli Ignazio Michele (Desio), Santoro Mariangela (Orbassano), Saponara Riccardo (Crema), Scarmagnan Monica (Este), Scataglini Fabrizio (Civitanova Marche), Seccia Loredana (Verbania), Selmo Vladimir (Trieste), Sensi Stefano (Pescara, San Valentino in Abruzzo Citeriore), Sicurella Luigi (Catania), Silvestri Antonello (Rocca Priora), Simone Massimo (Montesarchio), Sirca Antonella (Nuoro) Sleiman Intissar (Castiglione Delle Stiviere), Solla Paolo (Sassari), Sperber Sarah Anna (Lodi), Spinelli Laura (Spoleto), Spoegler Franz (Vipiteno), Sucapane Patrizia (L’Aquila), Suraci Domenico (Locri), Tagliabue Benedetta (Carate Brianza), Tagliente Stefania (Acquaviva delle Fonti), Tamietti Elena (Asti), Tedeschi Gianluca (Pomezia), Tetto Antonio (Merate), Tiezzi Alessandro (Arezzo), Tiraboschi Pietro (Milano), Tognoni Gloria (Pisa), Tomasetti Carmine (Giulianova), Torchia Francesco (Reggio di Calabria), Toriello Giuseppe (Eboli), Trevisi Giovanna (Campi Salentina), Tripi Gabriele (Erice, Marsala), Trombetta Giuseppe (Reggio di Calabria), Tulliani Alessandro (Trieste), Vaccina Antonella Rita (Castelfranco Emilia), Valentinis Luca (Portogruaro), Varricchio Gina (Caserta), Vasquez Giuliano Antonella (Maglie), Vella Filomena (Trieste), Verde Federico (Milano), Verlato Chiara (Valdagno), Vezzadini Giuliana (Castel Goffredo), Vidale Simone (Varese), Vignoli Assunta (Napoli), Villani Daniele (Cremona), Vitelli Alfredo (Santa Maria Capua Vetere), Volpentesta Luigina (Cosenza), Volpi Gino (Pistoia), Vozza Domenico (Piedimonte Matese), Wanderlingh Patrizia (San Bartolomeo in Galdo), Wenter Christian (Merano), Zaccherini Davide (Vignola), Zanardo Massimo (Castelfranco Veneto), Zanette Giampietro (Peschiera del Garda), Zanetti Michela (Carrara), Zanetti Orazio (Brescia), Zanferrari Carla (Vizzolo Predabissi), Zuffi Marta (Castellanza), Zupo Vincenzo (Sant’Agnello).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Francesco Giaquinto (Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing); Patrizia Lorenzini (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing); Emanuela Salvi (Investigation; Writing – review & editing); Giulia Carnevale (Investigation; Writing – review & editing); Roberta Vaccaro (Investigation; Writing – review & editing); Fabio Matascioli (Investigation; Writing – review & editing); Massimo Corbo (Investigation; Writing – review & editing); Nicoletta Locuratolo (Investigation; Writing – review & editing); Nicola Vanacore (Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing); Ilaria Bacigalupo (Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the designed delegates from each Italian region and autonomous province and all CCDD representatives, Maria Cristina Porrello and Gabriella Martelli for editorial assistance.

FUNDING

Project carried out with the technical and financial support of the Ministry of Health – chapter 2302.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-240594.

REFERENCES

1. | Jack CR , Bennett DA , Blennow K , et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (2018) ; 14: : 535–562. |

2. | Lang L , Clifford A , Wei L , et al. Prevalence and determinants of undetected dementia in the community: A systematic literature review and a meta-analysis. BMJ Open (2017) ; 7: : e011146. |

3. | Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement (2023) ; 19: : 1598–1695. |

4. | GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health (2022) ; 7: : e105–e125. |

5. | Rasmussen J and Langerman H. Alzheimer’s disease – why we need early diagnosis. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis (2019) ; 9: : 123–130. |

6. | Lacorte E , Ancidoni A , Zaccaria V , et al. Safety and efficacy of monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished clinical trials. J Alzheimers Dis (2022) ; 87: : 101–129. |

7. | Salemme S , Ancidoni A , Locuratolo N , et al. Advances in amyloid-targeting monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease: clinical and public health issues. Expert Rev Neurother (2023) ; 23: : 1113–1129. |

8. | Salemme S , Ancidoni A and Vanacore N. Responder analyses for anti-amyloid immunotherapies for Alzheimer’s disease: a paradigm shift by regulatory authorities is urgently needed. Brain Commun (2023) ; 5: : fcad276. |

9. | Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Grants Accelerated Approval for Alzheimer’s Drug. WA (DC): FDA/News & Events/FDA Newsroom/Press Announcements, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/pressannouncements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-alzheimers-drug (2021, accessed 1 February 2024). |

10. | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) FDA Grants Accelerated Approval for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-alzheimers-disease-treatment (2023, accessed 1 February 2024). |

11. | Frölich L and Jessen F. Lecanemab: Appropriate use recommendations — a commentary from a European perspective. J Prev Alzheimers Dis (2023) ; 10: : 357–358. |

12. | Biogen. LEQEMBI® Intravenous Infusion” (Lecanemab) for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease to be Launched in Japan on December 20, https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/leqembir-intravenous-infusion-lecanemab-treatment-alzheimers (2023, accessed 1 May 2024). |

13. | Villain N , Planche V and Levy R. High-clearance anti-amyloid immunotherapies in Alzheimer’s disease. Part 2: putative scenarios and timeline in case of approval, recommendations for use, implementation, and ethical considerations in France. Rev Neurol (2022) ; 178: : 999–1010. |

14. | Canevelli M , Rossi PD , Astrone P , et al. “Real world” eligibility for aducanumab. J Am Geriatr Soc (2021) ; 69: : 2995–2998. |

15. | Liu J , Hlávka J , Hillestad RJ , et al. Assessing the preparedness of the US health care system infrastructure for an Alzheimer’s treatment, RAND, Santa Monica, (2017) . |

16. | Hlavka JP , Mattke S and Liu JL. Assessing the preparedness of the health care system infrastructure in six European countries for an Alzheimer’s treatment. RAND health Q (2019) ; 8: : 2. |

17. | Cummings J , Apostolova L , Rabinovici GD , et al. Lecanemab: appropriate use recommendations. J Prev Alzheimers Dis (2023) ; 10: : 362–377. |

18. | Cummings J , Rabinovici GD , Atri A , et al. Aducanumab: appropriate use recommendations update. J Prev Alzheimers Dis (2022) ; 9: : 221–230. |

19. | Sims JR , Zimmer JA , Evans CD , et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA (2023) ; 330: : 512–527. |

20. | Albert MS , DeKosky ST , Dickson D , et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Focus (2013) ; 11: : 96–106. |

21. | McKhann GM , Knopman DS , Chertkow H , et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (2011) ; 7: : 263–269. |

22. | Folstein MF , Folstein SE and McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res (1975) ; 12: : 189–198. |

23. | Mehrani I and Sachdev PS. The role of memory clinics in the assessment and management of dementia, now and into the future. Curr Opin Psychiatry (2022) ; 35: : 118–122. |

24. | AIFA, Nota 85, https://www.aifa.gov.it/nota-85 (2023, Accessed 22 April 2024). |

25. | Di Fiandra T , Canevelli M , Di Pucchio A , et al. The Italian Dementia National Plan. Commentary. Ann Ist Super Sanità (2015) ; 51: : 261–264. |

26. | Bacigalupo I , Giaquinto F , Salvi E , et al. A new national survey of centers for cognitive disorders and dementias in Italy. Neurol Sci (2023) ; 45: : 525–538. |

27. | OECD. Care Needed: Improving the Lives of People with Dementia, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2018. |

28. | Di Pucchio A , Vanacore N , Marzolini F , et al. Use of neuropsychological tests for the diagnosis of dementia: A survey of Italian memory clinics. BMJ Open (2018) ; 8: : e017847. |

29. | Rossini PM , Cappa SF , Lattanzio F , et al. The Italian INTERCEPTOR Project: From the early identification of patients eligible for prescription of antidementia drugs to a nationwide organizational model for early Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. J Alzheimers Dis (2019) ; 72: : 373–388. Erratum in: J Alzheimers Dis 2020; 74: 409–409. |

30. | STATA, version 17.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA. |

31. | Ancidoni A , Sciancalepore F , Bacigalupo I , et al. The Italian fund for Alzheimer’s and other dementias: strategies and objectives to face the dementia challenge. Ann Ist Super Sanita (2022) ; 58: : 192–196. |

32. | Ministre de la santé et de la prévention, INSTRUCTION N° DGOS/R4/2022/217 du 10 octobre 2022 relative au nouveau cahier des charges des consultations mémoire et des centres mémoire ressources et recherche. NOR: SPRH2227923J (numéro interne: 2022/217), https://www.bourgogne-franche-comte.ars.sante.fr/media/113919/download?inline (2022, Accessed 22 April 2024). |

33. | Hausner L , Frölich L , von Arnim CA , et al. Memory clinics in Germany—structural requirements and areas of responsibility. Der Nervenarzt (2021) ; 92: : 708–715. |

34. | MSNAP. Quality Standard for Memory Services – Eight edition, Royal College of Psychiatrists, London, 2022. |

35. | Filippi M , Cecchetti G , Cagnin A , et al. Redefinition of dementia care in Italy in the era of amyloid-lowering agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: an expert opinion and practical guideline. J Neurol (2023) ; 270: : 3159–3170. |

36. | Betti M , De Tommaso CV and Maino F. Health Inequalities in Italy. Comparing regions among prevention, community health services and hospital assistance. Soc Dev Issues (2023) ; 45: : 61–76. |

37. | Belder CR , Schott JM and Fox NC. Preparing for disease-modifying therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol (2023) ; 22: : 782–783. |

38. | Istat, Rapporto annuale 2022. La situazione del paese, https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/271806 (2022, Accessed 1 February 2024). |

39. | Salvadori E , Pantoni L and Società Italiana di NeuroGeriatria (SINEG). The role of the neuropsychologist in memory clinics. Neurol Sci (2020) ; 41: : 1483–1488. |

40. | Mattke S , Gustavsson A , Jacobs L , et al. Estimates of current capacity for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease in Sweden and the need to expand specialist numbers. J Prev Alzheimers Dis (2024) ; 11: : 155–161. |

41. | Gervasi G , Bellomo G , Mayer F , et al. Integrated care pathways on dementia in Italy: a survey testing the compliance with a national guidance. Neurol Sci (2020) ; 41: : 917–924. |

42. | The Lancet Neurology. Treatment for Alzheimer’s disease: time to get ready. Lancet Neurol (2023) ; 22: : 455. |

43. | Dumas A , Destrebecq F , Esposito G , et al. Rethinking the detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Outcomes of a European Brain Council project. Aging Brain (2023) ; 4: : 100093. |

44. | Alzheimer’s Disease International. 2021 Alzheimer’s Innovation Readiness Index, Global Coalition on Ageing, https://www.alzint.org/u/GCOA_AIRI_AlzIndeXReport_FI-NAL.pdf (2021, Accessed 7 June 2024). |

45. | Alzheimer’s disease international. From plan to impact VII – Dementia at a crossroads. https://www.alzint.org/u/From-Plan-to-Impact-VII-Dementia-at-a-crossroads.pdf (2024, Accessed 7 June 2024). |