Lucidity in the Deeply Forgetful: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Background:

Even in severe states of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), accounts of an unexpected or paradoxical return of awareness and lucidity have been reported in some patients, documented formally, and studied.

Objective:

A scoping review was undertaken to survey the literature on the topic.

Methods:

Five databases were searched using pertinent search terms. Results were deduplicated and subsequently screened by title and abstract for relevance. Remaining reports were read and included or excluded using specific inclusion criteria. 30 results consisted of a mix of perspective papers, case reports, qualitative surveys of caregivers, law journal comments, and mechanistic speculation.

Results:

An equal mix of primary and secondary research was identified.

Conclusions:

The papers collected in this review provide a valuable methodological outline for researching the topic of lucid episodes in ADRD. The verified legitimacy and simultaneous inexplicability of these events promote philosophical discussion, mechanistic investigations, and sorely needed research in the field of ADRD.

INTRODUCTION

Dementia, literally a decline from a former mental state, is a syndrome with numerous neurodegenerative disease causes. A century ago, neurosyphilis was the primary cause, whereas today, in the age of antibiotics and as people are living into older ages, dementia is tropically secondary to many diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or Lewy Body diseases to mention just a few of dozens. In a nationally representative cross-sectional survey, the 2016 Health and Retirement Study found that 10% of individuals aged 65 years and older in the US had dementia [1]. Based on 2020 US census data, another study estimated the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the same age group at 1 in 9 [2]. Increasingly, clinicians speak of “mixed diagnoses” combining Alzheimer’s disease with vascular dementia, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and so forth. In all cases of dementia, there is a gradual decline in mentation and a point where human frailty and dependence make a caregiver necessary.

The term paradoxical lucidity can be defined as the spontaneous, unexpected reemergence of cognitive faculties in a deeply forgetful person for a transient time, or as described by the National Institute on Aging Work-shop on Lucidity in Dementia, the “unexpected, spontaneous, meaningful, and relevant communication or connectedness in a patient who is assumed to have permanently lost the capacity for coherent verbal or behavioral interaction due to a progressive and pathophysiologic dementing process” [3]. We prefer the term “unexpected lucidity” because relatively few people understand the meaning of “paradoxical” in this context, but in this review we use it because it does have a certain unfortunate dominance in the literature. Due to the unexpected nature of such occurrences, it can also be referred to as ‘unexpected lucidity’ [4]. Clinically, ‘deeply forgetful’ [4] connotes those individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), who have limited capacity for memory. The phenomenon of unexpected lucidity is in some sense perhaps paradoxical because cognitive faculties previously presumed extinct reappear, including speech, facial recognition, curiosity, self-identity, and others. Such events, whatever their length and depth, constitute a medical and epistemological surprise, especially to caregivers. The nomenclature of paradoxical or unexpected lucidity is much broader in scope than its cousin, ‘terminal lucidity’, which is more widely anthologized in the literature and is characterized by such a recovery of cognitive activities shortly before death [5, 6]. Unexpected lucidity can occur over many years, sporadically or through stimulation such as personalized music, visual or olfactory stimuli, and touch. It can occur any time in the experience of ADRD and does not have any relation to or require an imminent death. Unexpected or paradoxical lucidity appears as a non-chronological feature of ADRD [5].

The human person is at the center of this discussion. It is with this underlying but opaque continuity of identity and personhood in mind that paradoxical lucidity takes on meaning; namely, that the human subject, regardless of alertness or mental aptitude, remains present to those around them even if signs of properly human emotive and verbal communication have receded. Paradoxical lucidity amounts to a transient reversal of the signs of disease and presents an opportunity for new understanding of the human person still present throughout the disease. ADRD are fraught with medical and ethical quandaries, and these discussions must be centered around the personhood of the patient. In a sphere dominated by hypercognitive bias [4, 7] we must make room to notice the elements of self-identity that may reappear in unexpected ways, episodes that redefine the caregiver’s attitude and morale as such.

Until recent years, paradoxical lucidity has received comparatively little direct attention in the neurodegenerative and geriatric research space. The infancy of this topic stems from opaque neurological mechanisms and scarce population-based surveys [8]. With the aim of recentering on the continuity of the underlying identity of the human self, the present scoping review seeks to survey the literature about paradoxical lucidity including the extent and nature of the evidence on the topic, and to identify any gaps in the current body of knowledge spanning heterogenous disciplines (e.g., neurology, psychiatry, psychology, bioethics, etc.). While paradoxical lucidity is not widely characterized in the literature, studies are ongoing [9, 10].

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first comprehensive literature review on the topic. The scoping review intends to survey the landscape, report the findings to date, and amplify the experiences of deeply forgetful people and their caregivers— who witness paradoxical lucidity— as worthy of attention and thoughtful consideration.

METHODS

A small body of published literature, and an even smaller body of actionable data, exist about episodes of lucidity in deeply forgetful people. For this reason, a scoping review of the existing material was undertaken according to JBI guidelines and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist [11]. Identifying and characterizing primary and secondary sources about paradoxical lucidity, regardless of discipline or field, was the aim of the scoping review. Primary research is limited to direct evidence: experiments, case reports, surveys and qualitative or quantitative studies. Secondary research consists of theoretical articles, perspectives, and reviews about the topic.

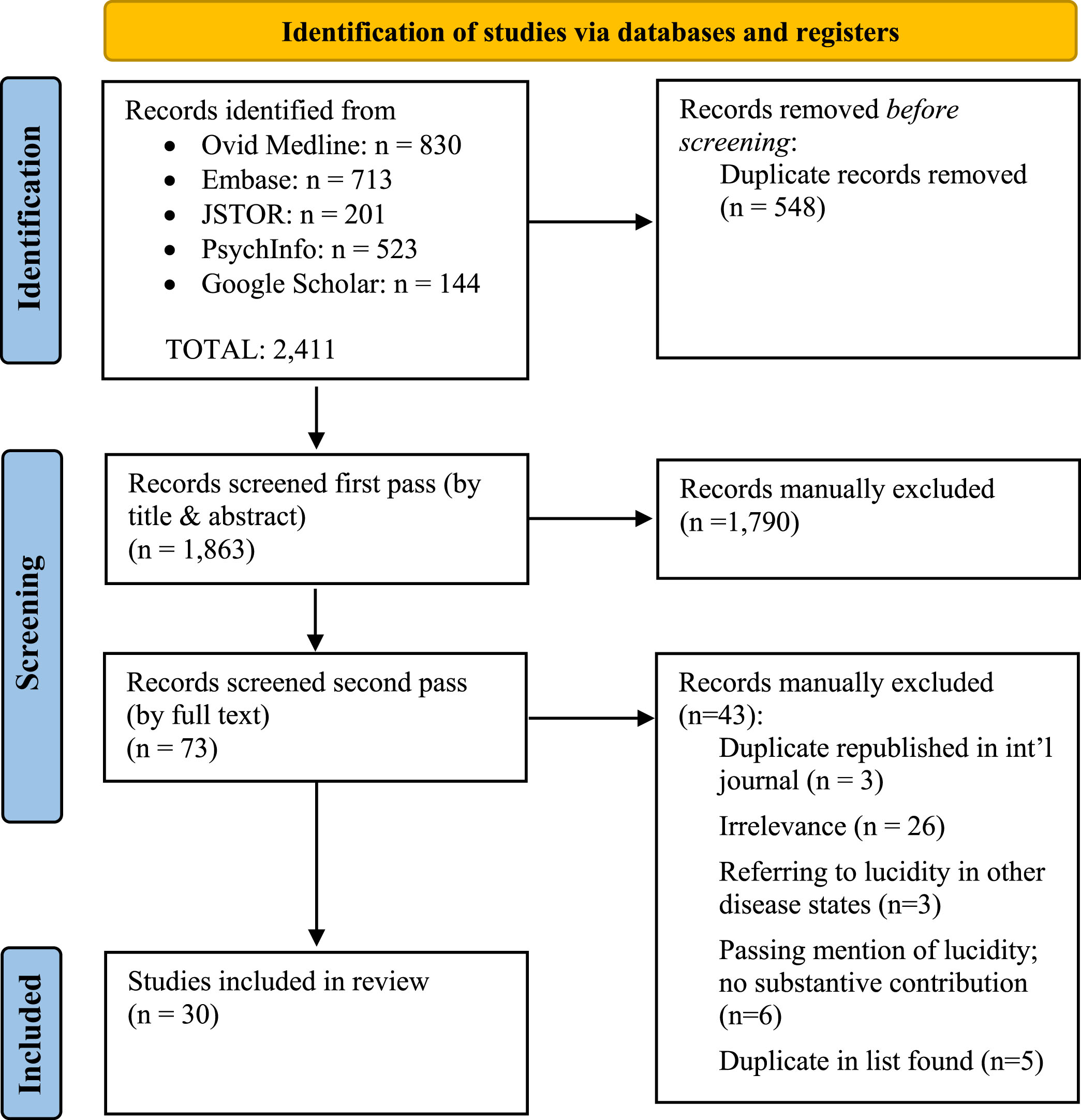

English language literature published from the inception of each database until the month of the scoping review initiation (July 2023) was collected (Fig. 1). The databases included: MEDLINE (hosted by Ovid); Embase (hosted by Elsevier); PsychInfo (hosted by EBSCO); and JSTOR (for possible humanities results). Terms for the concepts of “lucidity” and “advanced dementia” were combined with Boolean operators and searched in the title, abstract and keyword fields. Controlled vocabulary terms were also searched where available. Finally, the Google Scholar search engine was consulted for any stray sources in fields possibly not encompassed by the database searches and a pragmatic decision about quantity was made as display results became less relevant. (See Supplementary for full disambiguation of searches.)

Fig. 1

Review algorithm of search results from inception of each database.

Article eligibility was limited to all descriptions of the phenomenon of paradoxical lucidity in the form of data collection studies and secondary literature. Sources were excluded if they addressed properly perimortem phenomena, such as “terminal lucidity”. However, some articles were strategically included if they addressed terminal lucidity in a fashion that noted overlap with paradoxical lucidity. Additionally, if the full text of an article could not be retrieved, such as in symposia or expert workshop summaries, then the result was excluded. Ongoing studies were omitted.

Furthermore, if an eligible article was identified, it was extracted and entered into a record for synthesis in summary format. Information about the article recorded included authorship, date of publication, journal, country, design/article type and author conclusions.

Initial results were downloaded from each database and collated in EndNote 20, where the first author subsequently deduplicated them semi-manually. The results were then uploaded to the Rayyan software (rayyan.ai) where the first phase of screening was performed by title and abstract salience by the first author. In the second phase of screening, full text versions of each result were read to ensure eligibility by the first and second authors. A second, entirely manual deduplication was performed at this stage, to preclude results initially published in a domestic journal and later republished in an international journal. In several cases, journal issues were obtained through interlibrary loan. Finally, a snowballing review of each publication’s citations was performed to account for any otherwise uncovered and germane material. Screening and extraction were completed by the primary author of this paper.

RESULTS

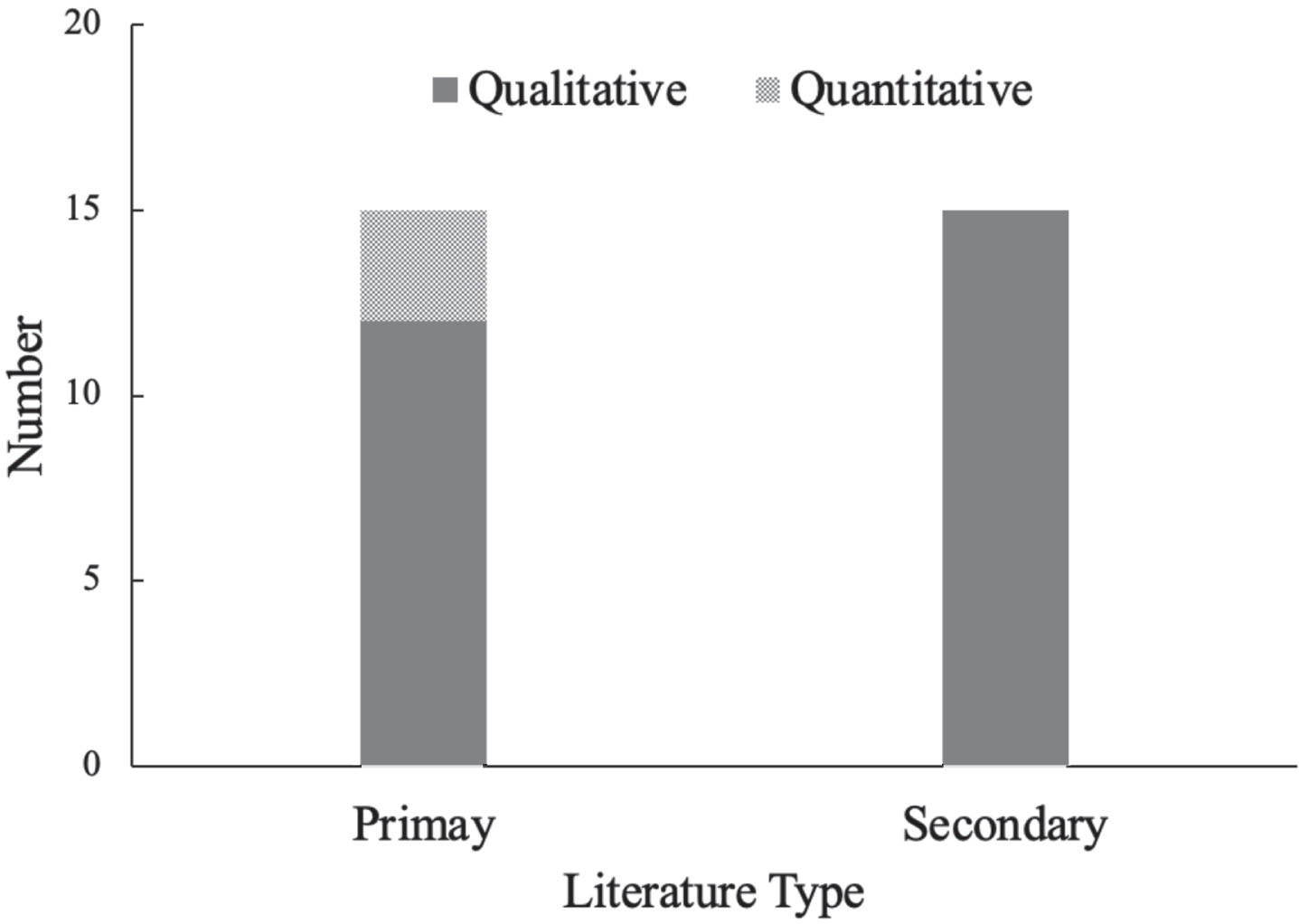

A total of 2,411 records were obtained. 30 were found to be eligible (Table 1). An equal portion of primary and secondary research was identified and included in the final tabulation (Fig. 2). Case studies and insightful perspective papers predominated the results, mostly from the last five years. Most work has attempted to propose a valid methodological framework for studying lucidity in ADRD, with a common focus on defining episodes of lucidity, and consistent caregiver education and reporting techniques.

Fig. 2

Primary research was predominantly qualitative content analyses of caregiver questionnaires, interviews, or other survey method. Some population-data was quantitatively assessed. Secondary literature focused on theoretical aspects of lucidity and methodology.

Table 1

Database results and takeaways

| Source | Journal | Year | Country | Design/Article Type | Author’s Conclusion |

| Batthyány and Greyson [12] | Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice | 2021 | Multi-national | Survey/Qualitative Study | Lucid episodes are primarily a near-death phenomenon. Discussion of relationship between paradoxical and terminal lucidity. |

| Benson et al. [13] | Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders | 2023 | United States | Case Report | Lucid episode is distressful to the patient. Episodes exist along a continuum in the disease progression. |

| Bostanciklioglu [14] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2021 | Türkiye | Theoretical Article | Sudden changes to neuromodulatory circuits in advanced dementia can produce neurotransmitter discharge triggering arousal &attention. Lucid dreaming may be a mechanistic model for studying lucidity in dementia. |

| Bostanciklioglu [15] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2020 | Türkiye | Theoretical Article | Conventional hippocampus-centered memory theory may not be valid. Researching the relationships of the raphe nucleus, locus coeruleus, main mediators of serotonin level in brain, and memory retrieval may make progress in the study of lucidity and treatment of ADRD. |

| Eldadah, Fazio, and McLinden [16] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2019 | United States | Perspective | Research resources offer potential for understanding mechanisms of ADRD and consciousness |

| Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al. [17] | The Gerontologist | 2023 | United States | Qualitative Study | Episodes of lucidity are distinct from routine fluctuations of the disease process. Caregiver interpretations vary. Observation is the best way to study the phenomenon; caregivers are central to the discussion. Qualitative appraisal instruments needed. |

| Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al. [18] | Journal of Gerontological Nursing | 2021 | United States | Letter to the Editor | Episodes of lucidity could occur when the person is alone. Scope of definition must be broad because meaning of episode is not limited to the caregiver. |

| Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al. [19] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2023 | United States | Perspective | Guiding questions, considerations, possible hypotheses &flowchart of event characteristics. Potential for disambiguating between paradoxical and terminal lucidity. |

| Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al. [20] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2023 | United States | Qualitative Study | Episodes of lucidity are both positive and negative experiences for caregivers. |

| Gotell, Brown, and Ekman [21] | International Psychogeriatrics | 2003 | Sweden | Comparative Study | Music can arouse lucid episodes. A unifying mechanism is nebulous. |

| Griffin et al. [22] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2022 | United States | Qualitative Study | Caregiver experience with lucid episodes are usually positive and sometimes stressful. |

| Klapman [23] | The University of Western Ontario | 2021 | Canada | Thesis/Quantitative Study | Experiment gives framework for studying the effect of music on lucidity. Tempo-specified or familiar music had no effect on the variable of divergent thinking. |

| Mashour et al. [24] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2019 | United States | Theoretical Article | Upon systematic verification, lucid episodes can show that the brain can assess functional networks to reach the outside world even in the setting of severe dementia. Ethical and research frameworks proposed. |

| Meeks [25] | University of Dayton Law Review | 2018 | United States | Law Journal Comment | Lack of objective measurement of lucid episodes creates legal ambiguities which can be resolved by the creation of Certified Alzheimer’s Legal Specialists. This can avoid serious legal quandaries. |

| Morris and Bulman [26] | Journal of Gerontological Nursing | 2020 | Canada | Concept analysis/Literature Review | The concept of lucidity has a basis in law and dream study. A theoretical definition is proposed, distinguished by spontaneity in the context of neurodegenerative disease and meta-awareness. |

| Nahm et al. [5] | Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics | 2012 | United States | Review | Repots of lucidity prevalent in 19th century medical literature. Mechanisms of lucidity are elusive; more research and neuroscientific models are needed. |

| Nahm [27] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2022 | Germany | Letter to the Editor | Paradoxical lucidity and terminal lucidity sometimes overlap. Terminal lucidity does not necessitate a neurodegenerative disorder. Paradoxical lucidity is germane to advanced neurodegenerative disorders and may or may not be expressed shortly before death. |

| Nahm [28] | Journal of Anomalous Experience and Cognition | 2022 | Germany | Perspective | Memory and consciousness is elusive, as demonstrated in individuals with malformed brains. Anomalous events are crucial to study. Implications for enhancing the understanding of consciousness. |

| Ney, Peterson, and Karlawish [29] | Journal of the American Geriatric Society | 2021 | United States | Case Study | Paradoxical lucidity has vast ethical implications. Preliminary ethical framework for patient, caregiver(s), and family proposed. Humility in approach is foundational. |

| Normann et al. [30] | Journal of Clinical Nursing | 2006 | Sweden | Population Prevalence Study | Episodes of lucidity were observed in every second resident, in a sample of people living with severe dementia in institutions |

| Normann, Asplund, and Norberg [31] | Journal of Advanced Nursing | 1998 | Norway | Survey/Qualitative Study | Lucid episodes are an important phenomenon of caregiving for people with severe dementia. Research of episodes of lucidity must be based on systematic observational criteria. Dementia does not destroy personhood or selfhood. |

| Normann et al. [32] | Journal of Clinical Nursing | 2005 | Norway | Case Study | Focus should be given to the topics raised by the person with dementia if they can communicate. Supportive, kind attitude important. Results cannot be generalized because this article is a case study. |

| Normann, Norberg, and Asplund [33] | Journal of Advanced Nursing | 2002 | Norway | Case Study | Supportive attitude towards the patient and avoiding making demands paramount. It is crucial that the person with dementia experience relatedness and being a part of. The connection between supporting and avoiding demands and lucidity/non-lucidity during conversation needs further study. |

| Peterson et al. [34] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2022 | United States | Letter to the Editor | Terminal lucidity is a type of paradoxical lucidity. |

| Peterson et al. [3] | Alzheimer’s & Dementia | 2022 | United States | Perspective | The provisional definition of paradoxical lucidity given by the National Institute on Aging 2018 expert workshop is unsatisfactory: refined definition proposed. Debate is important to establish the relationship between basic concepts within the provisional definition &how paradoxical lucidity is measured. |

| Ramirez et al. [35] | Aging & Mental Health | 2023 | United States | Survey/Qualitative Study | Collaborative work of an External Advisory Board, modified focus groups with staff and family caregivers, and structured cognitive interviews with health professionals were used to create a revised version of the lucidity measure. |

| Rice, Howard, and Huntley [36] | International Psychogeriatrics | 2019 | United Kingdom | Systematic Review | Awareness is relational according to caregivers. Systematized training of caregivers to assess awareness is desirable. All studies used a qualitative approach and there was significant variations of research questions, sample sized &methods. |

| Robnett et al. [37] | The American Journal of Occupational Therapy | 2021 | United States | Mixed Methods Survey | Music may be a catalyst for episodes of paradoxical lucidity. Directed stimulation should be researched to make lucid episodes more common. |

| Shulman et al. [38] | Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online | 2015 | United States | Law Journal Comment/Research Article | The application of the legal concept of the lucid interval is invalid in the setting of dementia and should not be used by courts to establish testamentary capacity. |

| Teresi et al. [39] | Journal of Gerontological Nursing | 2023 | United States | Pilot Study/Survey | The idiosyncratic nature of lucid episodes make them challenging to study systematically; reliance on caregivers’ and healthcare professionals’ reports is necessary. Most of them have seen unexpected lucid episodes. Structured interview instrument is designed. Systematic studies needed to permit elucidation of physiological or psychological mechanisms. |

DISCUSSION

While it is encouraging to see enthusiasm for the topic, none of the research performed thus far is medically actionable. The study of lucidity in ADRD is nascent and its research frameworks are undergoing multimodal validation [8]. Episodes of lucidity are real, unexplained, and difficult to interpret. Is grandma still fully there in some mysterious sense underlying the neurological decline, or are these episodes simply moments when certain neurological fragments are residually activated [7]? Sir John Eccles, the Nobel Laureate who originally discovered the neurotransmission ongoing at the synapse, and with whom Post studied, warned against the reductionism of “promissory materialism,” as have many great philosophers of mind in recent years including the pre-eminent Thomas Nagel in his 2012 classic Mind and Cosmos [40]. On the other hand, one can interpret these episodes within a metaphysics of pure materialism [7]. The scientific facts remain what they are, but they can be interpreted in different cultural contexts. These facts pose challenges and research opportunities for studies from fields ranging from neurobiology to philosophy of consciousness [41]. Vestigial interdisciplinary walls break down when studying the human mind. A transdisciplinary approach is merited.

The open question of some continuity of underlying identity despite communicative losses related to ADRD is ethically laden. This is because our respect for the deeply forgetful person is at stake. For example, if the person is in some surprising sense “still there” despite losses we are less likely to apply negative metaphors, such as “husk,” “shell,” “gone,” and “empty,” and we are more likely to make attentive efforts to notice the hints or signs of self-identity upon which “respect for persons” is based.

The precise nature of consciousness in deeply forgetful people is poorly understood, leaving open questions. Nonetheless, unfilled gaps in the scientific knowledge of this phenomenon cannot be justification for nonscientific or paranormal explanations. Such arguments by way of negation amount to the fallacy of denying the consequent and their conclusions are invalid (e.g., something of the form: if the brain is purely physical and consciousness is the purely physical product of its activity, then without the brain consciousness is impossible. But we see spontaneous return of consciousness in the setting of the most debilitating, severe, and terminal brain deficits. Ergo, consciousness may not be a purely physical phenomenon.). At the same time, it must be affirmed that the phenomenological whole value-picture of each human life is greater than the sum of its individual biological components.

Conversations about the theory of consciousness are academically enticing but bear little relevance in the day to day lives of deeply forgetful people and their caregivers. The greatest impact in the field of ADRD will come from treatment solutions derived from validated biological mechanisms. These conclusions are thoroughly delineated in the collective results of this review. In other words, in the works found, authors tend to agree that an accurate elucidation of the biological mechanism of these events will promote discovery of possible neurological loci for these experiences and eventual treatment for ADRD. At this point in time, lucidity in ADRD remains shrouded in mystery. Impact will also derive from a better understanding the emotional responses that primary, secondary, and professional caregivers have when they witness these episodes. Are these experiences inspiring of hope and meaning in caregivers, or do they lead to anxiety? Future and ongoing studies would benefit from examining the population prevalence of lucidity in ADRD as well its emotional impact on the caregiver. In a subsequent paper we will resolve the emotional responses to these episodes based on a national survey of caregivers.

Limitations

Limitations to this review method include one person making the first phase screening and data extraction decisions, as well as the exclusion of non-English language reports.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

John P. Ross (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Software; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing); Stephen G. Post (Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing – review & editing); Laurel Scheinfeld (Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Software; Writing – review & editing).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no acknowledgments to report.

FUNDING

The authors have no funding to report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary material.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-231396.

REFERENCES

[1] | Manly JJ , Jones RN , Langa KM , Ryan LH , Levine DA , McCammon R , Heeringa SG , Weir D ((2022) ) Estimating the prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in the US: The 2016 Health and Retirement Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol Project. JAMA Neurol 79: , 1242–1249. |

[2] | Rajan KB , Weuve J , Barnes LL , McAninch EA , Wilson RS , Evans DA ((2021) ) Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020–2060). Alzheimers Dement 17: , 1966–1975. |

[3] | Peterson A , Clapp J , Largent EA , Harkins K , Stites SD , Karlawish J ((2022) ) What is paradoxical lucidity? The answer begins with its definition. Alzheimers Dement 18: , 513–521. |

[4] | Post SG (2022) Dignity for Deeply Forgetful People. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. |

[5] | Nahm M , Greyson B , Kelly EW , Haraldsson E ((2012) ) Terminal lucidity: A review and a case collection. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 55: , 138–142. |

[6] | Nahm M , Greyson B ((2009) ) Terminal lucidity in patients with chronic schizophrenia and dementia: A survey of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis 197: , 942–944. |

[7] | Post SG (2000) The moral challenge of Alzheimer disease: Ethical issues from diagnosis to dying, 2nd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. |

[8] | Huntley J , Bor D , Deng F , Mancuso M , Mediano PAM , Naci L , Owen AM , Rocchi L , Sternin A , Howard R ((2023) ) Assessing awareness in severe Alzheimer’s disease. Front Hum Neurosci 16: , 1035195. |

[9] | George Mason University (2023) Paradoxical lucidity in dementia. Available from: https://www.ippp.gmu.edu/post/paradoxical-lucidity-in-dementia. |

[10] | New York University Grossman School of Medicine (2023) Parnia Lab. Consciousness at End of Life: Paradoxical Lucidity. Available from: https://med.nyu.edu/research/parnia-lab/consciousness/consciousness-end-lifeparadoxical-lucidity. |

[11] | Tricco AC , Lillie E , Zarin W , O’Brien KK , Colquhoun H , Levac D , Moher D , Peters MDJ , Horsley T , Weeks L , Hempel S , Akl EA , Chang C , McGowan J , Stewart L , Hartling L , Aldcroft A , Wilson MG , Garritty C , Lewin S , Godfrey CM , Macdonald MT , Langlois EV , Soares-Weiser K , Moriarty J , Clifford T , Tuncalp Ö , Straus SE ((2018) ) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169: , 467–473. |

[12] | Batthyány A , Greyson B ((2021) ) Spontaneous remission of dementia before death: Results from a study on paradoxical lucidity. Psychol Conscious 8: , 1–8. |

[13] | Benson C , Fehland J , Botsch M , Block L , Gilmore-Bykovskyi A ((2023) ) The impact of episodes of lucidity on people living with dementia and their caregivers: A case report. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 37: , 142–144. |

[14] | Bostanciklioglu M ((2021) ) Unexpected awakenings in severe dementia from case reports to laboratory. Alzheimers Dement 17: , 125–136. |

[15] | Bostancıklıoglu M ((2020) ) An update on memory formation and retrieval: An engram-centric approach. Alzheimers Dement 16: , 926–937. |

[16] | Eldadah BA , Fazio EM , McLinden KA ((2019) ) Lucidity in dementia: A perspective from the NIA. Alzheimers Dement 15: , 1104–1106. |

[17] | Gilmore-Bykovskyi A , Block L , Benson C , Fehland J , Botsch M , Mueller K , Werner N , Shah MJ ((2023) ) “It’s You”: Caregiver and clinician perspectives on lucidity in people living with dementia. Gerontologist 63: , 13–27. |

[18] | Gilmore-Bykovskyi A , Block L , Benson C , Griffin JM ((2021) ) The importance of conceptualizing and defining episodes of lucidity. J Gerontol Nurs 47: , 5. |

[19] | Gilmore-Bykovskyi A , Griffin JM , Mueller KD , Parnia S , Kolanowski A ((2023) ) Toward harmonization of strategies for investigating lucidity in AD/ADRD: A preliminary research framework. Alzheimers Dement 19: , 343–352. |

[20] | Gilmore-Bykovskyi A , Block L , Benson C , Fehland J , Botsch M , Mueller K ((2023) ) The impact of episodes of lucidity on people living with dementia and their caregivers: A case report. Alzheimers Dement 37: , 142–144. |

[21] | Götell E , Brown S , Ekman SL ((2003) ) Influence of caregiver singing and background music on posture, movement, and sensory awareness in dementia care. Int Psychogeriatr 15: , 411–430. |

[22] | Griffin JM , Kim K , Gaugler JE , Biggar V , Frangiosa T , Bangerter L , Batthyany A , Finnie DM , Lapid MI ((2022) ) Caregiver appraisals of lucid episodes in people with late-stage Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias. Alzheimers Dement 14: , e12313. |

[23] | Klapman S (2021) ‘The Memory of All That’: The effects of music on paradoxical lucidity in older adults [master’s thesis]. The University of Western Ontario, London, ON. |

[24] | Mashour GA , Frank L , Batthyany A , Kolanowski AM , Nahm M , Schulman-Green D , Greyson B , Pakhomov S , Karlawish J , Shah RC ((2019) ) Paradoxical lucidity: A potential paradigm shift for the neurobiology and treatment of severe dementias. Alzheimers Dement 15: , 1107–1114. |

[25] | Meeks KC ((2018) ) Losing your mind, losing your rights: A certification process to safeguard Alzheimer’s patients and the moving target of the lucid interval. U Dayton L Rev 44: , 79. |

[26] | Morris P , Bulman D ((2020) ) Lucidity in the context of advanced neurodegenerative disorders: a concept analysis. J Gerontol Nurs 46: , 42–50. |

[27] | Nahm M ((2022) ) Terminal lucidity versus paradoxical lucidity: A terminological clarification. Alzheimers Dement 18: , 538–539. |

[28] | Nahm M ((2022) ) The importance of the exceptional in tackling riddles of consciousness and unusual episodes of lucidity. J Anomalous Exp Cog 2: , 264–296. |

[29] | Ney DB , Peterson A , Karlawish J ((2021) ) The ethical implications of paradoxical lucidity in persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 69: , 3617–3622. |

[30] | Normann HK , Asplund K , Karlsson S , Sandman PO , Norberg A ((2006) ) People with severe dementia exhibit episodes of lucidity. A population-based study. J Clin Nurs 15: , 1413–1417. |

[31] | Normann HK , Asplund K , Norberg A ((1998) ) Episodes of lucidity in people with severe dementia as narrated by formal carers. J Adv Nurs 28: , 1295–1300. |

[32] | Normann HK , Henriksen N , Norberg A , Asplund K ((2005) ) Lucidity in a woman with severe dementia related to conversation. A case study. J Clin Nurs 14: , 891–896. |

[33] | Normann HK , Norberg A , Asplund K ((2002) ) Confirmation and lucidity during conversations with a woman with severe dementia. J Adv Nurs 39: , 370–376. |

[34] | Peterson A , Clapp J , Harkins K , Kleid M , Largent EA , Stites SD , Karlawish J ((2022) ) Is there a difference between terminal lucidity and paradoxical lucidity? Alzheimers Dement 18: , 540–541. |

[35] | Ramirez M , Teresi JA , Ellis J , Gonzalez-Lopez P , Silver S , Rutigliano M , Vidal-Manzano J , Boratgis G , Devanand DP , van Meer I , Bhatti I , Bhatti U , Luchsinger JA ((2023) ) Unexpected lucidity in dementia: Application of qualitative methods to develop an informant-reported lucidity measure. Aging Ment Health 27: , 2395–2402. |

[36] | Rice H , Howard R , Huntley J ((2019) ) Professional caregivers’ knowledge, beliefs and attitudes about awareness in advanced dementia: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int Psychogeriatr 31: , 1599–1609. |

[37] | Robnett RH , Meuser T , Michael C , Garside M , Gibson B ((2021) ) First steps toward promoting paradoxical lucidity: Meaningful engagement when least expected at the end of life. Am J Occup Ther 75: (Suppl 2), 7512510256p1. |

[38] | Shulman KI , Hull IM , DeKoven S , Amodeo S , Mainland BJ , Herrmann N ((2015) ) Cognitive fluctuations and the lucid interval in dementia: Implications for testamentary capacity. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 43: , 287–292. |

[39] | Teresi JA , Ramirez M , Ellis J , Tan A , Capezuti E , Silver S , Boratgis G , Eimicke JP , Gonzalez-Lopez P , Devanand DP , Luchsinger JA ((2023) ) Reports about paradoxical lucidity from health care professionals: A pilot study. J Gerontol Nurs 49: , 18–26. |

[40] | Nagel T (2012) Mind and Cosmos. Oxford University Press, New York. |

[41] | Huntley JD , Fleming SM , Mograbi DC , Bor D , Naci L , Owen A , Howard R ((2021) ) Understanding Alzheimer’s disease as a disorder of consciousness. Alzheimers Dement 7: , e12203. |