Consumer and Healthcare Professional Led Priority Setting for Quality Use of Medicines in People with Dementia: Gathering Unanswered Research Questions

Abstract

Background:

Historically, research questions have been posed by the pharmaceutical industry or researchers, with little involvement of consumers and healthcare professionals.

Objective:

To determine what questions about medicine use are important to people living with dementia and their care team and whether they have been previously answered by research.

Methods:

The James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership process was followed. A national Australian qualitative survey on medicine use in people living with dementia was conducted with consumers (people living with dementia and their carers including family, and friends) and healthcare professionals. Survey findings were supplemented with key informant interviews and relevant published documents (identified by the research team). Conventional content analysis was used to generate summary questions. Finally, evidence checking was conducted to determine if the summary questions were ‘unanswered’.

Results:

A total of 545 questions were submitted by 228 survey participants (151 consumers and 77 healthcare professionals). Eight interviews were conducted with key informants and four relevant published documents were identified and reviewed. Overall, analysis resulted in 68 research questions, grouped into 13 themes. Themes with the greatest number of questions were related to co-morbidities, adverse drug reactions, treatment of dementia, and polypharmacy. Evidence checking resulted in 67 unanswered questions.

Conclusion:

A wide variety of unanswered research questions were identified. Addressing unanswered research questions identified by consumers and healthcare professionals through this process will ensure that areas of priority are targeted in future research to achieve optimal health outcomes through quality use of medicines.

INTRODUCTION

While healthcare professionals strive to provide evidence-based care, there are often uncertainties in healthcare-related decision making on an individual patient level and the clinician/system level, particularly with regards to how to best deliver care in a healthcare system. While some level of uncertainty will always exist in healthcare, many areas of uncertainty are driven by a lack of research and/or inconsistent findings [1].

Historically, research agendas in healthcare have been determined by commercial entities, such as pharmaceutical companies, or researchers or policy analysts with minimal, if any, input from healthcare professionals and the people that the research intends to help (i.e., those living with the medical condition) [2, 3]. This approach can mean questions encountered by consumers and healthcare professionals in everyday practice remain unanswered. Choosing research questions that are important to consumers is likely to result in efficient use of research funding [4]. This is being increasingly recognized by funding bodies internationally, with many now recommending or even requiring consumer involvement in projects, including in the planning of the research questions [5]. It can take 17 years for research evidence to be translated into practice; the so called ‘evidence to practice gap’ [6]. One of the contributors to this may be that research is not asking the ‘right’ questions. Relevant stakeholder engagement has great potential to improve research adoption by realigning research with the needs of those impacted [7]. It is therefore essential that health and medical research is driven by the unanswered research questions that are most important to people with lived experience of medical conditions and those who treat and care for them [3, 8, 9]. Questions regarding quality use of medicines is one such example.

Quality use of medicines means using medicines safely and effectively to obtain optimal health outcomes. It involves selecting the best treatment option for the individual, and when a medicine is considered necessary, ensuring individuals and their healthcare professionals have the knowledge and skills to use those medicines in a safe and effective manner [10]. Quality use of medicines is a central objective of Australia’s National Medicines Policy and is underpinned by principles of the primacy of consumers and the wisdom of their experience, partnership, and consultative, collaborative and multidisciplinary activity [11]. Optimizing medicine use towards the goal of achieving quality use of medicines is an essential step towards improving the quality of life of people with chronic medical conditions. Despite this goal, in Australia, 250,000 hospital admissions and 400,000 emergency department visits annually are a result of medicine-related problems, with a cost of $1.4 billion, 50% of which are preventable [12]. There are similar concerns about medicine-related harm, and how it can be prevented, growing internationally [13]. It has been estimated that the global annual avoidable cost of suboptimal medicine use is US $500 billion [14].

In 2021, between 386,200 and 472,000 Australians were living with dementia, with numbers predicted to rise [15]. Internationally, 50 million people are living with dementia [16]. People living with dementia have greater physical health problems than others of the same age, experience more hospital admissions than other older people, and are at increased risk of delirium and other iatrogenic harms [17]. Achieving quality use of medicines in people living with dementia is complex [18, 19]. Most people living with dementia also have other medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, depression, and diabetes [20, 21]. Therefore, they are often prescribed multiple medicines, both to treat symptoms of dementia and to help manage comorbidities. On average, older adults living with dementia in the community take five regular medicines, with those in residential aged care facilities taking 10 regular medicines [20–24]. Additionally, about half are taking at least one potentially inappropriate medicine (where likely harms outweigh likely benefits for the individual) [25, 26]. Half of all residents of aged care facilities are living with dementia and most require assistance with medicine taking. Additional complexities arise with cognitive impairment, such as difficulties with shared-decision making and unintentional non-adherence [18].

A Lancet editorial noted that: “The quest for new drugs must not overshadow improving today’s care and patients’ lives”[27]. Therefore, it is imperative to ensure that currently available medicines for dementia and other comorbid conditions are used safely and effectively. There are many avenues for research in the field of quality use of medicines with potential to improve evidence-based care, and research activities should align with the needs of consumers and healthcare professionals. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify evidence uncertainties from the perspective of consumers and healthcare professionals regarding quality use of medicines in people living with dementia. This article describes the first steps in a larger research program which aims to identify the top 10 unanswered questions in the field of quality use of medicines in people with dementia, prioritized by people living with dementia, their carers (including friends and family), and healthcare professionals in Australia. While the ultimate goal of this program of work was to establish the Top 10 priorities, we present the first half of this work on identifying the unanswered research questions to illustrate how the field of quality use of medicines in people living with dementia is conceptualized by consumers and healthcare professionals and can be divided into themes, and to highlight the current state of research in this area.

METHODS

This study uses the James Lind Alliance (JLA) Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) method of bringing together consumers and healthcare professionals, on an equal basis, to identify and prioritize evidence uncertainties for research to address. It aims to ensure that clinical research is directed to clinical practice questions that are the most important, relevant, and beneficial to the end users [9, 28]. The JLA method has been used internationally in over 100 different topic areas [29, 30]. The method is flexible and responsive to the topic under consideration and needs of the population, with core principles of inclusivity, equal involvement, transparency, and a commitment to using and contributing to the evidence base. The JLA method was chosen as it is a multi-step process which combines qualitative and quantitative methods, includes review of the literature to establish the unanswered questions, and allows input from a large number and variety of stakeholders across a large and diverse geographical area (such as Australia). The JLA method was specifically set up to prioritize research questions and incorporate the voices of all end users of research. Additionally, it has been previously used in dementia-related priority setting activities [31, 32]. Consumers (including patients, carers, and family/friends) and healthcare professionals were the focus of this work as they are both end users of research. As such, they are best placed to know what research is the most important; for the patients and their loved ones by knowing what would benefit them, and therefore others like them, and for healthcare professionals by knowing what knowledge would best inform their ability to provide care to the variety of patients they support.

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of South Australia (#202847), using implied consent through completion and submission of anonymous surveys. This manuscript reports the first 4 steps of the JLA method (described below) which addressed the aim of identifying unanswered research questions. The remaining 2 steps which are concerned with prioritization will be reported separately (interim priority setting, final priority setting workshop) [33].

Establishment of the priority setting partnership

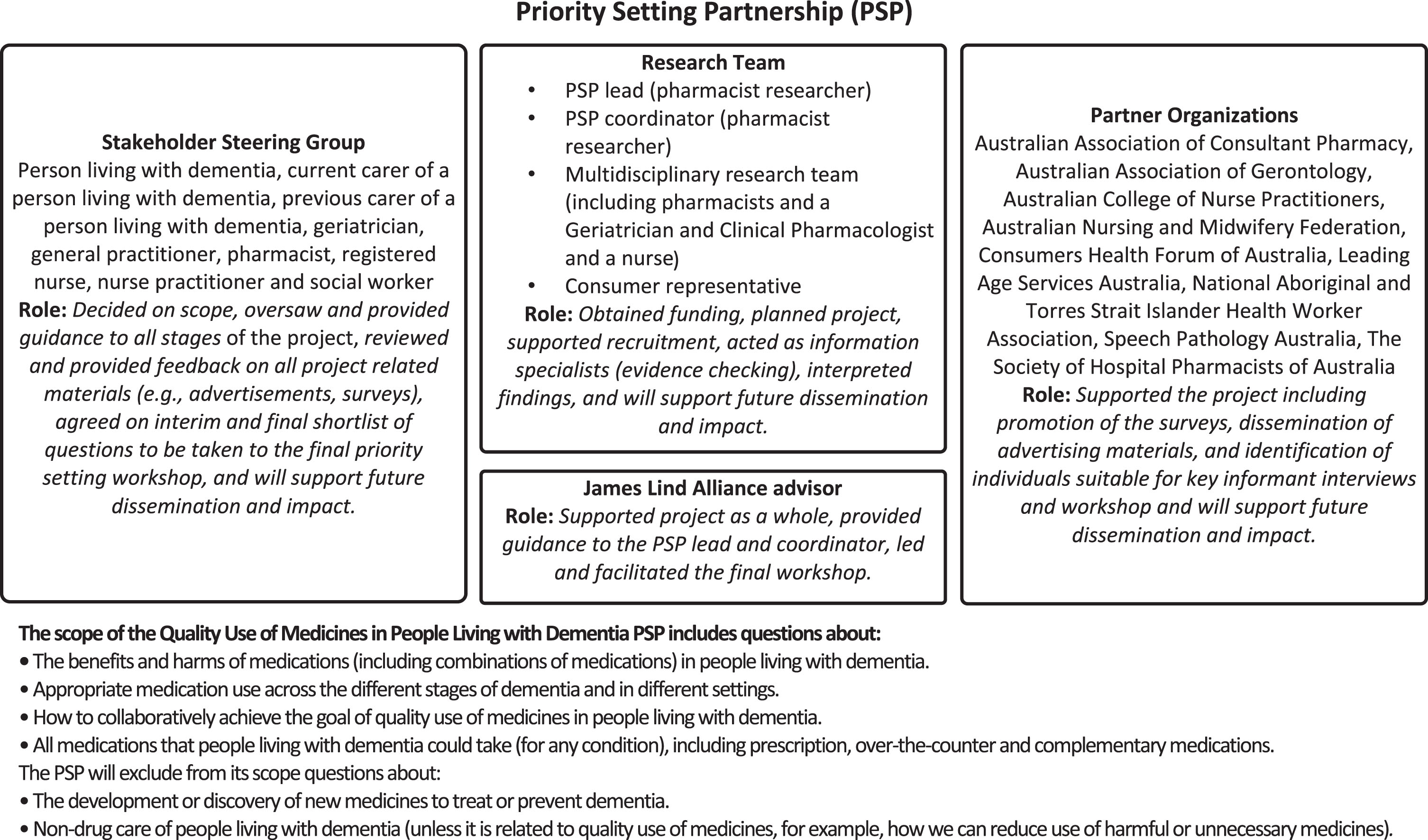

The Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) is the name given to the individuals and groups involved in the process of developing a ‘Top 10’ unanswered question list using the JLA method. Our PSP consisted of a Steering Group, Partner Organizations, a research team, and a JLA advisor. The composition and roles of these groups, and the scope of the PSP is shown in Fig. 1. The Steering Group was composed of 9 individuals (person living with dementia, current carer of a person living with dementia, previous carer of a person living with dementia, geriatrician, general practitioner, pharmacist, registered nurse, nurse practitioner, and social worker). The main roles of the Steering Group for the activities described in this manuscript were overseeing and informing the whole process, deciding on the scope, reviewing project related materials, and contributing to analysis and writing of summary questions. The topic of ‘quality use of medicines in people living with dementia’ was established prior to beginning the study; however, the Steering Group determined the specific scope within this broad area. For example, they decided to include complementary and herbal medicines and education of healthcare professionals. The 9 Partner Organizations (professional and consumer advocacy organizations) supported the project through promotion of the surveys, identification of participants for interviews and the workshop, and will support future dissemination and impact activities.

Fig. 1

Composition and scope of the Quality Use of Medicines in People Living with Dementia Priority Setting Partnership.

Gather evidence uncertainties

The second step in the JLA method aimed to identify as many evidence uncertainties about this topic as possible from stakeholders. Evidence uncertainties were gathered using a cross sectional, anonymous, qualitative survey, administered both online (using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of South Australia [34, 35]) and in hard-copy. Participants self-completed (or completed with the help of a friend, family member, or carer) the survey at a time and place of their choosing.

Participants

Two groups of participants were recruited for this study: consumers and healthcare professionals. Consumers included people living with dementia, carers (informal and unpaid carers such as family members or friends), family and friends of people living with dementia (who do not identify as carers), and members of the public with an interest in dementia (such as dementia advocates, previous carers). Healthcare professionals included any healthcare professional (including students and trainees) or person employed by a healthcare organization, with experience providing care for people living with dementia, including those in clinical, support and administrative roles. We targeted healthcare professionals who may have a role directly or indirectly in medicine management, review, or support (see professions listed in Supplementary file 2). All participants were at least 18 years old, able to read and write in English, and Australian citizens or currently living and working in Australia. This work was limited to Australia to ensure that the final Top 10 could be used to influence research, funders, and policy in Australia as many of the potential questions (such as those related to the healthcare system) would be context specific.

Survey design

The survey comprised two sections. Section one asked respondents to list up to three questions and/or concerns about medicine use in people living with dementia that are the most important to them (open question). Asking for three questions was chosen to encourage participants to submit more than one, while minimizing the participants’ anticipated time and burden to maximize completion of the survey (i.e., if the survey asked for up to 10, this may have deterred some from participating). Section two asked optional demographic questions (Table 1). Two different versions of the survey were used for the two different groups, with language and demographic questions tailored towards consumers or healthcare professionals. The surveys were developed based on ones used by previous groups using the JLA method [30], were reviewed by the research team and Steering Group, and piloted with 11 consumers and 5 healthcare professionals with changes made iteratively until they were deemed suitable by the Steering Group (Supplementary file 1: Consumer survey and Supplementary file 2: Healthcare professional survey).

Table 1

Participant characteristics (151/77; Consumer/Healthcare professionals)

| Characteristic (number of valid responses1) | Consumer N (%) | Healthcare N (%) |

| Which of the following best describes you? (146/NA) | ||

| Person living with dementia | 14 (9.6) 2 | – |

| Family or friend of a person living with dementia | 62 (42.5) | – |

| Carer3 of a person living with dementia | 38 (26.0) | – |

| Other4 | 32 (21.9) | – |

| Profession (NA/76) | ||

| GP | – | 6 (7.9) 2 |

| Geriatrician | – | 8 (10.5) |

| Other Medical Specialist | – | 6 (7.9) |

| Pharmacist | – | 11 (14.5) |

| Nurse Practitioner | – | 3 (3.9) |

| Registered or enrolled nurse | – | 26 (34.2) |

| Assistant in nursing or aged care worker | – | 4 (5.3) |

| Other healthcare professional5 | – | 11 (14.5) |

| Student/trainee | – | 3 (3.9) |

| Other non-clinical role | – | 1 (1.3) |

| Other6 | – | 5 (6.6) |

| Where do you live? (132/76) | ||

| ACT | 1 (0.76) | 7 (9.2) |

| NSW | 54 (40.9) | 10 (13.2) |

| NT | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| QLD | 19 (14.4) | 17 (22.4) |

| SA | 12 (9.1) | 26 (34.2) |

| TAS | 1 (0.76) | 2 (2.6) |

| VIC | 25 (18.9) | 13 (17.1) |

| WA | 20 (15.1) | 1 (1.3) |

| Your Gender (135/76) | ||

| Female | 104 (77.0) | 54 (71.1) |

| Male | 31 (23.0) | 22 (28.9) |

| Age (130/75) | ||

| 18–39 | 2 (1.5) | 21 (28.0) |

| 40–59 | 40 (30.8) | 37 (49.3) |

| 60–79 | 80 (61.5) | 16 (21.3) |

| 80+ | 8 (6.2) | 1 (1.3) |

| In which country were you born? (131/69) | ||

| Australia | 97 (74.0) | 48 (69.6) |

| Other | 34 (26.0) | 21 (30.4) |

| Are you of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin? (134/74) | ||

| No | 132 (98.5) | 72 (97.3) |

| Yes, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.7) |

| Approximately how many different medicines do you (or the person you care for) take? (133) | ||

| None | 8 (6.0) | – |

| 1–4 | 56 (42.1) | – |

| 5–9 | 45 (33.8) | – |

| More than 10 | 16 (1.2) | – |

| Don’t know | 8 (6.0) | – |

| Where do you work? (NA/66) | ||

| Primary care/community | – | 20 (30.3) 2 |

| Hospital | – | 33 (50.0) |

| Residential Aged Care Facility | – | 14 (21.2) |

| Outpatient/outreach clinics | – | 9 (13.6) |

| Other | – | 3 (4.5) |

| How long have you worked in your current profession? (NA/67) | ||

| Less than 1 year | – | 5 (7.5) |

| 1–5 years | – | 13 (19.4) |

| 6–10 years | – | 11 (16.4) |

| 11–20 years | – | 12 (17.9) |

| More than 20 years | – | 26 (38.8) |

| What is your experience in providing care for people with dementia? (NA/65) | ||

| A small to moderate proportion of the people that I care for are living with dementia (e.g., <50%) | – | 40 (61.5) |

| Most but not all of the people I care for are living with dementia (e.g., >50%) | – | 17 (26.2) |

| All of the people that I care for are living with dementia | – | 8 (12.3) |

1Demographic questions were optional to maximize responses to the first part of the survey. Numbers are shown as consumer/healthcare professional. 2May add up to greater than 100% as participants were able to select more than one option. 3Carers were individuals who self-identified as a carer (i.e., no pre-specified definition was given to potential participants). 4For example, participants reported being a previous carer for a person living with dementia who is now deceased, concerned that a loved one has dementia but without a formal diagnosis, advocate of people living with dementia, person with mild cognitive impairment (without a dementia diagnosis). 5Included: dentist (2), occupational therapist, physiotherapist, psychologist, social worker (2), other non-specified clinical role (4). 6Included: paid advocate (2) and non-specified.

Sample size

As there is no sample size calculation for this type of survey [33], our target sample size of 50–200 responses from each group was based on prior experience of the research team and previous studies that used the JLA method. The decision to stop recruitment was informed by qualitative methodology principles regarding saturation and information power [36, 37] and sufficient responses from a variety of potential participants (informed by participant demographic information) was achieved, while also considering pragmatic constraints such as the study timeline.

Survey promotion

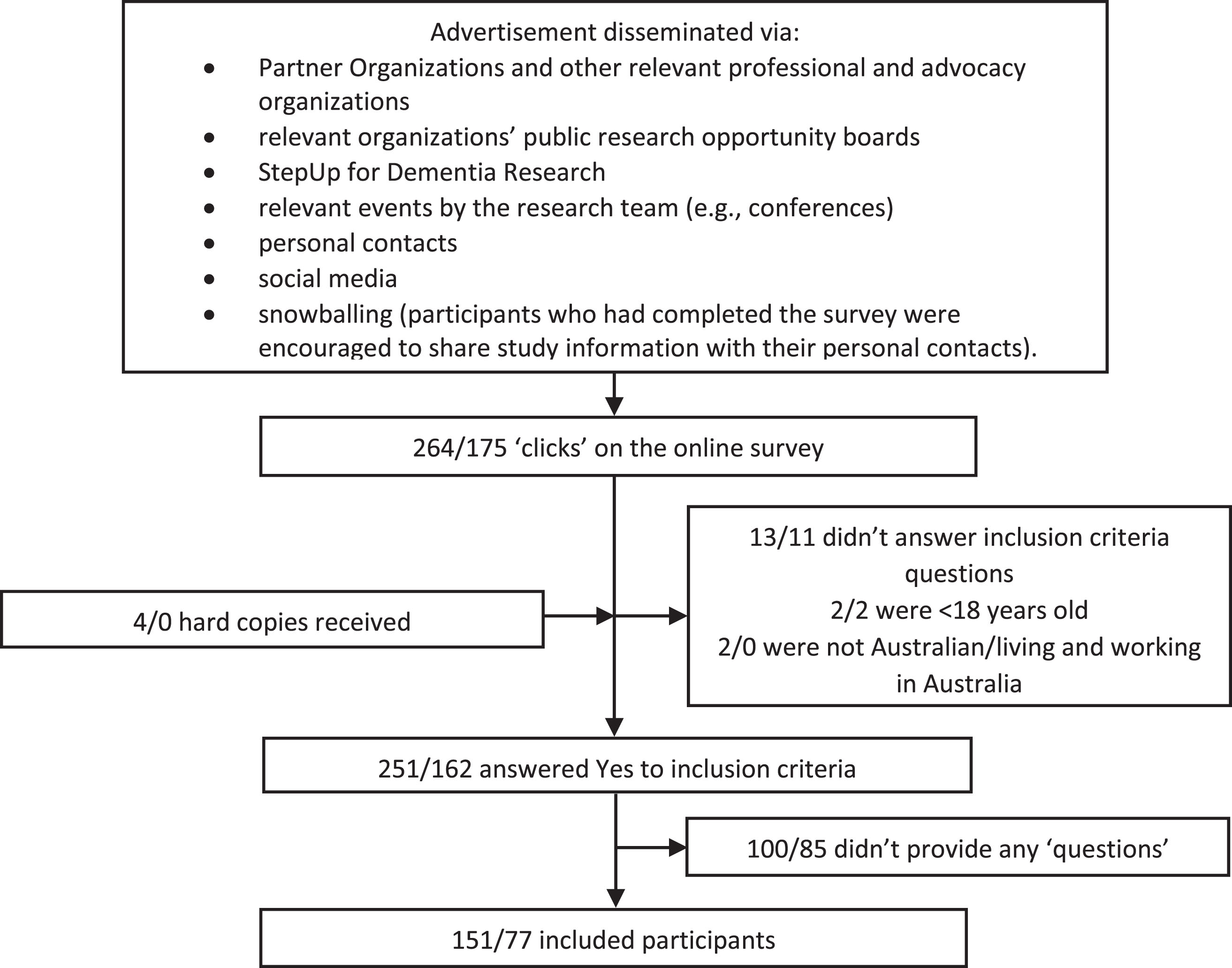

The survey was open from September to November 2020 inclusive. A broad and multifaceted approach to recruitment and convenience sampling was used to obtain responses from a diverse variety of participants across Australia (see Fig. 2). Mostly, the survey was promoted by emailing the advertisement to Partner Organizations and other professional and advocacy organizations, who were asked to distribute the advertisement to their members through the mechanism of their choice (e.g., via regular newsletters, social media posts, at events). Organizations to target were identified by the research team and Steering Group and through internet searches for Australian consumer, professional or other organizations. Additionally, a research engagement service for dementia research known as StepUp for Dementia Research Australia was used to advertise the consumer survey. The study was mostly advertised electronically; however, where requested, paper versions (including reply-paid envelopes) were provided.

Fig. 2

Survey participant recruitment flow chart. Numbers shown are Consumer/Healthcare professionals. Numbers shown here cannot be used to calculate a response rate as it is possible that individuals clicked on the survey to read about it, and then returned to the survey later to complete (which would result in 2 ‘clicks’). Total response rate cannot be calculated as the survey was distributed via external organizations and social media.

Additional data sources

In addition to the anonymous survey, unanswered questions were collected from (i) key informant interviews and (ii) relevant existing national documents identified by the research team (based on their knowledge of this research field). Interview participants were purposively recruited through the same mechanisms as used for the survey but targeted to individuals whose demographic characteristics were underrepresented in survey respondents. Recruitment for interviews was continued until identified gaps in survey respondent characteristics were all filled. The process was iterative, first we reached out to our Partner Organizations and then to other relevant organizations that could identify potential participants. We let them know the types of people we wanted to speak with (e.g., in a specific geographical area, or of a particular profession), the organizations then reached out to people to gain consent for us to contact them. Interviews were conducted by telephone or videoconferencing software, with notes taken by the interviewer (ER or LC, not audio recorded, Supplementary file 3: Key Informant Interview guide) and implied consent used (detailed in the participant information sheet and described verbally by the interviewer before starting the interview). Interviews allowed for in depth discussion and gathering of a large number of evidence uncertainties from a single person to compensate for people with similar characteristics being underrepresented in the survey responses.

Summarizing the responses gathered (analysis)

First, the responses to the survey were reviewed (by ER) and those that were out of scope (such as not medicine-related or related to the development of new medicines or non-drug care, Fig. 1), or not considered to be potential research questions (such as unclear submissions, or questions asking for information or advice) were removed. Second, conventional content analysis was used to analyze and group (categorize) the data [38]. In this approach, related sections of text were compared and put into groups based on conceptual relationships (i.e., those that were reporting the same concepts). Third, each group of related responses were reviewed, and an indicative summary question was generated. Fourth, summary questions were grouped into themes. This was then repeated with the interview notes and key documents, in a single analysis process (i.e., one set of results).

The conventional content analysis was conducted by a single investigator (ER), with the themes and summary questions reviewed by, and discussed with two members of the research team (MS and TN) on two occasions during the process of data collection. At the end of the data collection process, the Steering Group reviewed the themes, summary questions, and quotes which informed the questions; changes were made iteratively until consensus was achieved by the Steering Group (via virtual meetings and email). This could involve creating, altering, merging, or removing groups (i.e., summary questions) in alignment with the conventional content analysis process. The Steering Group also reviewed the quotes that were removed due to being out of scope or not research questions (deciding if any needed to be added back into the conventional content analysis) and could suggest new questions to be added based on their own lived experience that had not arisen from the data sources. QSR Nvivo 12 Plus software was used for data management, coding, and facilitation of the analysis. Participant characteristics were analyzed descriptively to describe the participant population.

Evidence checking

Following analysis, the next step involved determining if the summary questions were ‘unanswered’, that is, whether a level of uncertainty still exists about each question. Uncertainty was defined as no up-to-date, reliable systematic reviews or evidence-based guidelines of research evidence, or alternatively, up-to-date systematic reviews/guidelines reported that uncertainty existed. At this point (prior to evidence checking), no further questions could be added, and questions were removed or altered as a result of evidence checking.

Each summary question was checked by a member of the research team (ER, LC, MS, LKE, JG-T, ET, JKS, KT, SNH; referred to as ‘information specialists’ in the JLA method) using relevant key words in the following databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, National Institute for health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines, and Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines Registry. At the discretion of the information specialist, professional organization websites, PubMed, and Epistemonikos were also searched where relevant. References from 2018 until date of search (April 2021) were included. If the information specialist was unsure about whether a question was unanswered, this was resolved by discussion with another member of the research team and decided by the Project Lead when required. The research team had the opportunity to review all changes and removal of questions; however, no formal consensus process was conducted. The full details of this process are available online [39]. This rapid review approach aligns with the established JLA method, which recommends a pragmatic and proportionate evidence search [33]. Where it was identified that the summary question was ‘answered’ it was then removed from the list, to end up with a list of ‘unanswered questions’. Additionally, where the question was determined to be partially answered, it was reworded to focus on the unanswered element, with review of responses that informed the question to make sure that the summary question still represented the original data.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics and additional data sources

A total of 151 consumer participants and 77 healthcare professional participants completed the survey and were included in the analysis (Table 1, Fig. 2). Most consumers identified as a family member or friend (42.5%) or a carer (26.0%) of a person living with dementia with about 10% identifying as living with dementia. The most common healthcare professionals who responded were registered or enrolled nurses (34.2%) and pharmacists (14.5%). Most participants were female (consumers: 77.0% and healthcare professionals: 71.1%) and born in Australia (74.0% and 69.6%, respectively).

Eight key informant interviews were conducted with individuals with characteristics that were underrepresented in the survey; specifically, people living in three Australian states/territories (Tasmania, Queensland, Northern Territory); geriatricians; participants who had significant experience working in residential aged care facilities or worked in a practice that solely focused on caring for people living with dementia; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healthcare Workers and Practitioners; people who identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander; and those with experience in rural and remote communities (with most key informants fulfilling more than one of these characteristics).

Finally, an additional four existing documents were identified by the research team as relevant: a clinical practice guideline for people living with dementia, and recent reports from Dementia Australia, Alzheimer’s Disease International, and the Australian Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety [40–43].

Summary questions and themes

The 228 survey participants submitted a total of 545 questions (each participant was encouraged to list up to three). Analysis of the survey responses, key informant interviews and existing relevant documents were synthesized into 67 questions, and the Steering Group added one additional question during their review. These 68 questions were grouped into 13 themes (range of 1–12 questions in a theme, Table 2). No additional summary questions were created after the sixth key informant interview, or analysis of the four relevant existing documents (i.e., data saturation was achieved). Of the 68 questions identified, 59 questions were informed by both consumers and healthcare participants, six were informed by consumers only, and three by healthcare participants only. Summary questions were informed by between 1 and 83 unique respondents/sources. One question was solely informed by a single key informant interview.

Table 2

Themes and summary questions (pre-evidence checking)

| Theme | Question number ID | Summary Question (prior to evidence checking) | Example quotes from respondents | Number of consumer, healthcare, key informant respondents, existing key documents1 (Total respondents/ sources) |

| Awareness and Education | 1 | How can healthcare professionals best educate people living with dementia and their carers about their medicines? | Why do [you] prescribe medicine without giving me a written summary of what it is for, the side effects, review dates and what symptoms it might improve. (Consumer) | 27, 2, 5, 1 (35) |

| As the carer I away wanted to know how each new drug was going to help my husband . . . I wasn’t always sure I had enough information. (Consumer) | ||||

| Maybe some of the issues around actually giving people information in a way that makes it easy for them to understand. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 2 | How can medicine literacy (ability to read and understand information about medicines) be optimized in all people living with dementia and their carers? | Medication literacy is a huge problem - for a lot of medications . . . there are so many information sheets with lots of written information and documentation. These are generally not in a language that the general public can understand. (Key Informant) | 1, 0, 4, 1 (6) | |

| 3 | What knowledge and skills do healthcare professionals need to achieve safe, effective and appropriate medicine use in people living with dementia and also to support person- and relationship-centered care? What are effective ways of providing them with these skills and knowledge? | I am not confident that my doctor has enough knowledge or interest to reliably prescribe appropriate medications for me. I live in [regional Australia] and we have a constant turnover of doctors of various abilities. (Consumer) | 17, 5, 5, 2 (29) | |

| What training can be given to staff in the aged care sector to identify symptoms to trigger a medication review? (Clinician) | ||||

| Changed Behaviours | 4 | When and how should medicines be used to treat changed behaviors (previously referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia)? Does this recommendation vary by type and stage of dementia or setting of care? | I’m very concerned about the over-dependence on anti-psychotic therapy to ‘manage’ people living with dementia. (Consumer) | 25, 25, 3, 4 (57) |

| Is there a place for medicines in managing aggressive behavior, and if so what is the preferred medicine and dose? (Clinician) | ||||

| Why are we demonizing the therapeutic use of antipsychotics used in conjunction with behavioral plans . . . (Clinician) | ||||

| Managing behaviors - this is very poorly studied (although might be difficult to study - different patient will have different unique behavioral patterns). (Key Informant) | ||||

| While research tends to focus on managing agitation and depression, there is less research regarding treatment of other symptoms including apathy and anxiety. (Existing Key Document) | ||||

| 5 | What is the most effective and safe way to reduce the use of antipsychotics (when used to treat changed behaviors) in people living with dementia? | I’m very concerned about the over-dependence on anti-psychotic therapy to ‘manage’ people living with dementia. (Consumer) | 19, 6, 2, 4 (31) | |

| What can be done to ensure that medications are not given to people with dementia to manage ‘difficult behavior’ without ALL other management options being tried first? (Clinician) | ||||

| Staffing ratios and the impact on medications like antipsychotic use. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 6 | Do certain medicines increase the risk of changed behaviors (previously referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia) in people living with dementia? | Are the side effects of mood changes that occur in a number of medications (e.g., heart, blood pressure, etc.) taken into account when assessing someone with cognitive changes and their “challenging” behaviors? (Consumer) | 1, 2, 0, 0 (3) | |

| Do certain medicines increase the risk of BPSD in patients with dementia? (Clinician) | ||||

| Healthcare System and Person-Centered Care | 7 | How can healthcare professionals ensure that informed consent, from the person living with dementia or their substitute decision-maker, is obtained for medicine use? | My next of kin and other loved ones be involved in any decision about medications if I’m unable to give informed consent. (Consumer) Consent needs to be done properly as actual informed consent. Consent with psychotropics is also an issue . . . (Key Informant) | 9, 4, 4, 4 (21) |

| 8 | How can shared decision making about medicines be achieved between healthcare professionals and people living with dementia and their carers? | Being given options and the opportunity to make choices regarding medications. (Consumer) What is the best approach for using shared decision making for people with dementia? e.g., should carers always be involved? (Clinician) | 15, 3, 4, 1 (23) | |

| 9 | How can advanced care plans be used to inform decisions about medicines when the individual no longer has capacity to express their wishes? | Respect the wishes of person affected by cognitive disorders, as documented by them when they still had decision making capacity. (Clinician) | 0, 1, 0, 0 (1) | |

| 10 | What role do different healthcare professionals play in achieving safe, effective and appropriate medicine use in people living with dementia? And how can access to relevant healthcare professionals be achieved? | What is the expertise of the medical professional ordering such medications? GPs versus Gerontologist. Following administration who is monitoring person with dementia for adverse side effects? (Consumer) . . . need allied health and pharmacists embedded in RACFs. (Key Informant) | 7, 2, 7, 3 (19) | |

| Currently, ATSI [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander] HCW and P [Health Care Workers and Practitioners] are generally only involved at the end stage when there is non-compliance or when there is a problem. These professionals need to be involved right from the beginning. (Key Informant) | ||||

| Further research regarding the role of general practitioners in dementia care in Australia and the way in which they collaborate with specialists and hospitals is required. (Existing Key Document) | ||||

| 11 | How can communication between healthcare professionals be optimized, especially at transitions of care, to achieve multi-disciplinary care for people living with dementia? | That there is an understanding from all practitioners about medicines issued/prescribed by other health professionals to achieve best results for the person - not issuing/prescribing in isolation. (Consumer) | 8, 2, 8, 2 (20) | |

| There are also issues with communication - a pharmacist/GP/other may not be able to talk directly to care staff, so then they are relying on their documentation which can be really variable. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 12 | How could telehealth be used to achieve safe, effective and appropriate medicine use in people living with dementia, particularly for those living in rural and remote communities? | How can we use IT platforms to better connect those patients with dementia and polypharmacy with clinicians who are skilled in the medication management of this group. (Clinician) | 0, 1, 3, 0 (4) | |

| 13 | How can the process of drug approval be improved to ensure that the results are relevant to people living with dementia? | Have they been trialed on older people and both sexes? (Consumer) | 8, 0, 3, 1 (12) | |

| Need for clear data on the benefits and harms of medications in [People Living With Dementia]. No good [Randomized Controlled Trials] on the impact of different drugs/co-morbidities in [People With Dementia]. (Key Informant) | ||||

| Residential Aged Care Facilities (RACF) | 14 | How can residential aged care facilities best achieve safe, effective and appropriate medicine use in residents with dementia? | Staffing in residences of [people living with dementia] is problematic . . . has a high turnover rate. (Consumer) Why is that there are so many care recipients of [Residential Aged Care] homes that are consumers of polypharmacy - and when they are admitted to a general hospital are found to usually not require most of them? (Clinician) | 6, 4, 3, 3 (16) |

| In RACFs might also be dealing with multiple prescribers. The current model in RACFs is likely not sufficient. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 15 | What knowledge and skills do healthcare workers in residential aged care need to support safe, effective and appropriate medicine use in people living with dementia? What are effective ways of providing them with these skills and knowledge? | That whoever is administering the medicines understands what the medicines are, what they are used for, the implications of not taking these correctly. (Consumer) Why are those in nursing homes not trained in dementia to see the effects of medications on those with dementia? (Consumer) | 8, 3, 2, 4 (17) | |

| There is a reliance on low trained staff at RACFs to provide clinical information needed to make clinical decisions. (Key Informant) | ||||

| Medicine Management | 16 | What is the prevalence of non-adherence to medicines in people living with dementia? How can healthcare professionals and carers assess whether the person living with dementia is able to self-manage their medicines at home? | Are they remembering to take any prescribed medicines at the right time, right dose? (Consumer) Apart from the like of blood tests and other intrusive medical procedures, are there other ways of testing whether prescribed medication is being taken as prescribed? (Consumer) | 11, 2, 0, 0 (13) |

| 17 | How can people living with dementia and their carers be supported to manage medicines safely at home? | How can I safely and effectively ensure that my mother living with dementia takes her daily medicines at the correct time and dosage? (Consumer) | 52, 14, 5, 3 (74) | |

| One of my husbands meds is tiny and needs to be cut in half. He has enormous difficulty picking it up with his fingers (fine motor skills have deteriorated) and as he refuses to allow me to place them in his mouth I often find the 1/2 tab on the floor. (Consumer) | ||||

| Avoiding transfer to residential care simply for reasons of medication mismanagement. (Clinician) | ||||

| 18 | What is the best way to support safe and effective medicine management and administration when the person living with dementia is resistant to taking their medicines? | How to ensure that the person is taking his meds, including his conviction that they are not needed. (Consumer) | 4, 1, 0, 0 (5) | |

| One of the residents I work with, often refuses to take her medication, resulting in an escalation of her behavior . . . as she is in pain due to not taking her pain relief. (Clinician) | ||||

| 19 | What are the consequences of non-adherence, such as taking more or less than prescribed? | What happens if I forget my dementia medication tablet? (Consumer) | 12, 2, 0, 0 (14) | |

| Mum is on [asthma medication] and she forgets when she uses it and I often think she overuses it. Can this be harmful? (Consumer) | ||||

| 20 | What is the best time of day for people living with dementia to take their medicines? | What is the best time of day to take dementia medication? (Clinician) | 2, 1, 0, 0 (3) | |

| 21 | Can alternative delivery methods or routes of administration be used to facilitate use of medicines in people living with dementia (e.g., patches, crushed medicines)? | Is current research working on slow release medications that could be given weekly as opposed to daily for specific types of dementia to help improve medication compliance and limit the amount of drugs required to be taken on a daily basis? (Clinician) | 4, 3, 0, 0 (7) | |

| What other delivery methods could be used to ensure maximum effectiveness? e.g., Non crushable tablets being chewed (Clinician) | ||||

| Polypharmacy, Complexity and Deprescribing | 22 | What is the impact of polypharmacy (use of multiple medicines) on people living with dementia? What are effective ways to reduce polypharmacy, simplify medicine use, and reduce the cost for people living with dementia? | The cost; when you are on large numbers of medicines and are only on a pension, the cost is a HUGE imposition. (Consumer) Can a “cocktail” of prescribed medications cause the user more harm? (Consumer) | 32, 10, 4, 2 (48) |

| What can we do in balancing the person’s quality of life and use of medicines? (Clinician) | ||||

| Are there issues with taking multiple medications? (Clinician) | ||||

| Polypharmacy is a big problem - cannot put people with dementia multiple new drugs and expect them to cope. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 23 | What medicines are commonly used in people living with dementia? | What is the most commonly/prescribed drug for older people with dementia? (Clinician) | 1, 2, 0, 0 (3) | |

| 24 | How can ‘prescribing cascades’ (the starting of one drug to treat the side effect of another) in people living with dementia be prevented and reversed? | . . . a number of medications are being used to counteract the side effects of primary medications. (Clinician) | 1, 1, 1, 0 (3) | |

| Also concern about prescribing cascades. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 25 | What is the optimal model for medicine reviews to achieve safe, effective and appropriate medicine use in people living with dementia? Including who should be involved, how often should reviews be conducted, and what follow-up is needed? | To have a regular pharmaceutical review as I take many supplements with the six scripts . . . I have several sources of doctors writing scripts (Consumer) How can we improve timely ongoing review of medications being taken by those with dementia? (Clinician) | 11, 9, 3, 3 (26) | |

| Why are RMMRs [Residential Medication Management Reviews] not acted on in a timely manner? (Clinician) | ||||

| When doing medication reviews, it can be very hard for the pharmacist to find all the necessary information and follow-up on scripts. To have any financial viability of HMRs [Home Medicine Reviews] to rural and remote communities, they need to be done in batches (no travel allowance). (Key Informant) | ||||

| 26 | How can deprescribing (cessation of harmful and/or unnecessary medicines) be achieved in people living with dementia? And what are the benefits and risks of deprescribing? | What side effects will they have and what other medications can be taken or need to be stopped if taking this medication? (Consumer) Shouldn’t community pharmacists be authorized to deprescribe or monitor older patients who have been deprescribed? (Consumer) | 13, 16, 4, 0 (33) | |

| What is the best way to incorporate deprescribing advice into disease state treatment guidelines? (Clinician) | ||||

| Why isn’t more attention paid to deprescribing medicines for people with advanced dementia? (Clinician) | ||||

| 27 | Which medicines are potentially harmful or unnecessary in people living with dementia and should be stopped? | What medications can be STOPPED in people with dementia? (Clinician) | 4, 6, 2, 0 (12) | |

| If patients with severe dementia are taking drugs such as statin, which are for long term prophylaxis against vascular events, are these still indicated? (Clinician) | ||||

| 28 | What impact does one or more other medical conditions have on the safety and efficacy of medicines in people living with dementia? | How do you balance multiple medical issues hence multiple medications with a person’s dementia? (Consumer) | 15, 5, 3, 1 (24) | |

| I would like doctors to look at the whole person not just their dementia. For example, other conditions and medications. (Consumer) | ||||

| Do different comorbidities lead to less or more sensitivity of impact on particular outcomes. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 29 | What are the best tools, guidelines and resources for healthcare professionals to inform safe, effective and appropriate medicine use in people living with dementia? | When a person with dementia is already on long term medication for other conditions such as heart arrythmia or cholesterol management, are there tools for the prescribing doctor to prioritize medication, even if means stopping certain medications which might be counteracting the effects of medication aimed at slowing the progress of dementia? (Consumer) | 1, 0, 4, 2 (7) | |

| GPs need better guidance on prescribing in this population, particularly around polypharmacy - firm and practical guidance - and for what to do in different environments. (Key Informant) | ||||

| Treatment of Dementia | 30 | What are the short-term and long-term benefits and harms of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (medicines used to treat the symptoms of dementia)? When and how should these medicines be used and for what types and stages of dementia? | What are the long term effects of taking medications on a person’s health, e.g., side affects more memory loss nausea skin rashes, etc. (Consumer) Will the effect of the drug wear off over time and the dose need to increase or be stopped? (Consumer) | 60, 17, 4, 2 (83) |

| At what stage do medications have to start in order to be most effective? (Consumer) | ||||

| Does medication improve the quality of life? (Consumer) | ||||

| What are some downsides of medication to treat dementia? (Clinicians) | ||||

| What impact does the different types of dementia have on benefits and harms of medications? (Key Informant) | ||||

| 31 | Who is likely to benefit from medicines for dementia? Who is likely to experience harm? | Concern that we don’t always know how different medicines can affect people and each person is different and therefore the effect may also be different. (Consumer) . . . my most important question is usually clinical one . . . for a given patient, is it time to trial an anticholinesterase? (Clinician) | 5, 3, 3, 0 (11) | |

| Concern that we don’t always know how different medicines can affect people and each person is different and therefore the effect may also be different. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 32 | What is the prevalence of under-prescribing of medicines to treat dementia in people living with dementia, and how can this be improved? | How normal is it for dementia sufferers not to take medication for their condition? (Consumer) It is also likely that dementia is underdiagnosed in [remote] communities. And because diagnosis is tricky in remote communities, there is likely underuse of dementia medications. (Key Informant) | 2, 0, 3, 0 (5) | |

| 33 | Do any complementary, alternative or herbal medicines or dietary supplements have a benefit in treating dementia? | Are there natural herbal medicine that can be used with [prescription] medicine and help with dementia? (Consumer) | 8, 7, 2, 0 (17) | |

| Does Souvenaid help? specialists still seem to be recommending it. (Clinician) | ||||

| What evidence is there for non prescription medication e.g., herbal supplements in the treatment of dementia? (Clinician) | ||||

| 34 | Are there benefits in treating dementia with medical cannabis? | How much investigation has been done into cannabis both in early & advanced stages of dementia? (Consumer) | 2, 0, 0, 0 (2) | |

| 35 | Do any medicines registered for purposes other than dementia have a benefit in treating or preventing dementia? | Is antidepressant suitable to take or beneficial to treat symptoms of dementia? (Consumer) | 3, 2, 0, 0 (5) | |

| What are the best protocols to use non-standard medications for dementia, for example quetiapine . . . (Clinician) | ||||

| 36 | Do medicines used for reduction of risk factors (such as reducing cardiovascular risk) prevent or treat dementia? | In diagnosis of vascular dementias, can blood pressure and blood thinning medications be given preventatively? Do they help slow dementia? (Consumer) | 3, 2, 3, 1 (9) | |

| What role to CVD health and diabetes management have in prevention of dementia? (Key Informant) | ||||

| 37 | Are there any drug interactions between the medicines used to treat the symptoms of dementia and the other medicines that people living with dementia take (including non-prescription and herbal medicines)? | I would want to check that taking medicines for dementia didn’t react adversely with any medicines that I am already taking, including vitamins and minerals tablets. (Consumer) | 26, 7, 1, 0 (34) | |

| Any interactions with local anesthetics with adrenaline used for dental treatment? (Clinician) | ||||

| 38 | When should medicines which are used to treat the symptoms of dementia be stopped? How should these medicines be stopped? | How long should donepezil be continued? (Consumer) Does withdrawal of medication prescribed for dementia precipitate worsening of symptoms even if there is no perceived symptom benefit? (Clinician) | 6, 5, 1, 1 (13) | |

| How do we better educate ourselves regarding de-prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors? (Clinician) | ||||

| The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report Dispensing patterns for anti-dementia medications 2016-171 contributes to a growing body of evidence which demonstrates the under-review of anti-dementia medications . . . (Key Existing Document) | ||||

| Specific Comorbidities | 39 | When, how and in who should medicines be used to treat delirium in people living with dementia? | What medicines are best choice in persons with dementia who develop acute delirium in the hospital setting? (Clinician) | 0, 1, 1, 0 (2) |

| 40 | When, how and in who should medicines be used to treat depression and anxiety in people living with dementia? | I questioned the underuse of antidepressant medication - particularly when my mother was starting to experience memory loss and other symptoms and still had insight into this (and was depressed/grieving/not coping). (Consumer) | 14, 5, 0, 1 (20) | |

| What is the safest and most effective medication for treating anxiety and depression in persons with [Mild Cognitive Impairment] or mild dementia? (Clinician) | ||||

| 41 | When, how and in who should medicines be used and/or withdrawn to provide symptom relief in people living with dementia at end of life? | Poorly understood end of life and palliation in dementia care, reluctance to prescribe medications to ease suffering. (Consumer) | 2, 1, 1, 2 (6) | |

| We need quality end-of-life care. We need medication available in RACF to provide pain relief and help families to understand loved ones’ needs. (Key Existing Document) | ||||

| 42 | When, how and in who should medicines be used to treat severe mental health conditions in people living with dementia? | How are psychiatric medicines monitored in people with dementia if they are cognitively impaired? (Consumer) | 1, 1, 2, 1 (5) | |

| Another issue is multiple use of antipsychotics and other medications when they are seen by an older adult’s mental health professional . . . . they are always discharged back to the RACF on multiple medications, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, antipsychotics, etc. But they all seem to end up on different regimens, but they are always complex (i.e., there doesn’t seem to be any standard treatment guideline) (Key Informant) | ||||

| 43 | Are there any special considerations when using medicines to manage heart conditions and diabetes in people living with dementia? | Antihypertensive therapy in patients with cognitive impairment: is intensive therapy harmful? (Clinician) Clarity and consistency for recommendations regarding role of statins in people living with dementia - evidence and risk/benefit regarding side effects/harms versus benefits for people for whom vascular events may play a major role. (Clinician) | 4, 6, 3, 0 (13) | |

| 44 | When, how and in who should medicines be used to treat insomnia in people living with dementia? | Often GPs prescribe antidepressant medications to alleviate concerns/complaints by carer that the individual living with dementia is “apathetic” or has “troubles sleeping”. The gross prescription, and furthermore lack of review is a concern. (Consumer) | 2, 2, 0, 0 (4) | |

| What is the efficacy of melatonin for insomnia management in those living with dementia? (Clinician) | ||||

| 45 | When, how and in who should medicines be used to manage pain in people living with dementia? | First concern - poorly controlled pain management. (Consumer) | 5, 7, 0, 3 (15) | |

| What level of analgesia should be given simply based on observed signs of pain, like grimacing when standing or moving? (Clinician) | ||||

| 46 | Are there any special considerations when treating Parkinson’s Disease in people living with dementia? | What are the risks in keeping the balance between dementia and Parkinson’s when a person has both and how do you prioritize which condition gets precedence? (Consumer) | 1, 0, 0, 0 (1) | |

| 47 | Are there any special considerations when treating epilepsy or seizures in people living with dementia? | My concern about medication is if they prescribed something for the seizures would I be worse off? (Consumer) | 1, 0, 0, 0 (1) | |

| 48 | Are there any special considerations when prescribing antibiotics to people living with dementia? | Any considerations when prescribing antibiotics? (Clinician) | 1, 1, 0, 0 (2) | |

| 49 | Are there any special considerations when treating skin conditions in people living with dementia? | I observed after several months on [medication] that he was getting more confused and the skin on his face around his nose was peeling in thick layers. The inside of his ears were terribly dry and flaking too. (Consumer) | 1, 0, 0, 0 (1) | |

| Specific Adverse Drug Reactions and Harms | 50 | Which medicines have anticholinergic effects? How can risk of harm from these medicines be identified and measured (including cumulative load) to inform clinical care? | What medications are people on that cause sedation, are anticholinergic or increase the risk of falls. (Clinician) | 0, 1, 1, 1 (3) |

| Concern about anticholinergic and sedative load - which tools are best for identifying this, should take into account doses. (Key Informant) | ||||

| 51 | Which medicines cause drowsiness in people living with dementia? What are the harms of use of these medicines (such as benzodiazepines) in people living with dementia? | Do his medications increase his fatigue? (Consumer) Can Benzodiazepines taken long term affect one’s memory? (Consumer) | 13, 6, 1, 1 (21) | |

| Risks of prn [when required] and/or regular benzodiazepine use for BPSD in patients with dementia. (Clinician) | ||||

| 52 | Which medicines can cause delirium in people living with dementia? | Effect of anesthesia on patients with dementia . . . (Clinician) | 5, 2, 2, 0 (9) | |

| Some medications prescribed for dementia patients can make their symptoms worse –i.e., induce hallucinations. (Consumer) | ||||

| 53 | Which medicines impair function and activities of daily living in people living with dementia? | Will it affect my ability to function? (Consumer) Can the above-mentioned drugs have [an effect] on balance & mobility? (Consumer) | 11, 3, 1, 0 (15) | |

| Impact of these meds on physical dexterity or movement thus reducing ability to clean teeth via reduced motor skills. (Clinician) | ||||

| 54 | Can any medicines cause dementia? | I have read that prolonged use of some anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medication can contribute to the onset of dementia. Is this correct? (Consumer) | 9, 2, 1, 0 (12) | |

| I would like to know about long term anticholinergic use and its role in dementia development. (Clinician) | ||||

| 55 | Which medicines worsen memory and thinking in people living with dementia or speed up decline of dementia? | Which over the counter medicines may affect my memory? (Consumer) | 31, 9, 1, 1, (42) | |

| Or could [medicines] fasten cognitive decline in some people? (Consumer) | ||||

| What combination of medicines can worsen cognition in people with Lewy Body Dementia? (Clinician) | ||||

| 56 | Can any medicines alter mood or personality in people living with dementia? | Do the medicines alter mood or personality (Consumer) Dulling the person’s personality (Consumer) | 9, 1, 0, 0 (10) | |

| 57 | Which medicines increase the risk of falls in people living with dementia? | Is the medicine contributing to him falling?? (Consumer) | 6, 3, 2, 1 (12) | |

| Falls/fractures and functional decline are also a big concern - questions about how to prevent these from happening or worsening (Key Informant) | ||||

| 58 | Which medicines and combinations of medicines cause QT prolongation (changes in the rhythm of the heart which can lead to serious heart problems) in people living with dementia? | Risks of QT prolongation when patients are on multiple agents that can increase QT interval and how to manage this. (Clinician) | 0, 1, 0, 0 (1) | |

| 59 | Which medicines cause urinary incontinence in people living with dementia? | If a patient is on furosemide - why? . . . can contribute to urinary urgency and incontinence (Clinician) | 0, 2, 0, 0 (2) | |

| Are there medications that worsen urinary incontinence? (Clinician) | ||||

| 60 | Which medicines can harm the kidneys in people living with dementia? | Does taking medication to delay the progress of dementia affect [your] kidneys? (Consumer) | 1, 1, 1, 0 (3) | |

| 61 | Can medicines mask (hide) symptoms of dementia or other relevant symptoms or conditions? | Can medications mask illnesses (Clinician) | 0, 1, 0, 0 (1) | |

| Monitoring for Harms and Benefits | 62 | What is the best way to monitor for benefits (or lack of benefits) and harms (side effects and other risks) of medicines in people living with dementia? | Following administration who is monitoring person with Dementia for adverse side effects? (Consumer) Why are those in nursing homes not trained in dementia to see the effects of medications on those with dementia? (Consumer) | 23, 3, 3, 3 (32) |

| How you can measure the effectiveness, especially in the later stages of dementia. (Clinician) | ||||

| Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Changes | 63 | Should doses of specific medicines be changed in people living with dementia to prevent side effects? | Are there any relevant pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic changes that occur in people living with dementia in which a dose adjustment to a medication may be necessary? (Clinician) | 1, 2, 0, 0 (3) |

| Influences on Prescribing | 64 | What influences the prescribing and administration of medicines in people living with dementia? | Why do people stay on these medications if benefits are not being seen? (Consumer) | 11, 6, 2, 1 (20) |

| . . . nursing and personal care workers could influence the decision to prescribe psychotropic medications the most and many believed the medications to be more beneficial than is in fact the case. (Existing Key Documents) | ||||

| 64 | What influence does the media have on use of medicines in people with dementia? | Why don’t we rely on medical knowledge about drug use instead of media (Clinician) | 1, 1, 0, 0 (2) | |

| Media attention to psychotropic medications, as if any medication to calm a person with BPSD is cruel - the person with BPSD then has to live with agitation & distress due to media attention (Consumer) | ||||

| COVID-19, Vaccines and Restrictions | 66 | What is the impact of ‘locking down’ care facilities in response to COVID-19 and other infectious diseases on medicine management? | The current restrictions of visitors and visitation hours makes advocating and checking on a loved ones very difficult. There is very little or no check now on how many medication mistakes are being made. I have previously found and reported many. (Consumer) | 1, 0, 0, 0 (1) |

| 67 | What is known about COVID-19 in people with dementia in regard to susceptibility, risk of harms and how to treat? | What is known about COVID and meds used in people with dementia and their susceptibility to infections and likelihood of getting COVID - e.g., PPIs. What is known about COVID and delirium - need for COVID specific medication reviews and treatment algorithms. (Key Informant) | 0, 0, 1, 0 (1) | |

| 68 | What vaccines (such as the flu vaccine) should people living with dementia regularly receive? | This summary question was suggested by a Steering Group member (consumer) during the review of the summary questions and themes (no quote) | 0, 0, 0, 0 (0) |

1Number of unique survey respondents/key informants/documents which contributed to the summary question.

The themes (number of questions) were: Awareness and Education (3 questions), Changed Behaviours (3), Healthcare System and Person-Centred Care (7), Residential Aged Care Facilities (2), Medicine Management (6), Polypharmacy, Complexity, and Deprescribing (8), Treatment of Dementia (9), Specific Comorbidities (11), Specific Adverse Drug Reactions and Harms (12), Monitoring for Harms and Benefits (1), Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Changes (1), Influences on Prescribing (2), and COVID-19, Vaccines and Restrictions (3).

Evidence checking

The 68 summary questions underwent evidence checking (see Supplementary file 4: Evidence checking results). No questions were judged as ‘answered’; however, four questions were determined to be partially answered and so were revised to focus on the unanswered aspect of the question (Supplementary file 5: Questions altered after the evidence checking process). One question (Question 23: ‘What medicines are commonly used in people living with dementia?’) was removed during the evidence checking process, and this deletion was agreed by the Steering Group, as it did not focus on a specific issue that could have a direct impact on clinical practice.

This resulted in a final list of 67 unanswered research questions about quality use of medicines in people living with dementia, as suggested by consumers and healthcare professionals in Australia.

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings and comparison with previous research

This study represents the first application of the JLA method in an Australian context and for a research topic focused on ‘quality use of medicines’. The research identified 67 unanswered research questions, grouped into 13 themes, gathered from people living with dementia, their informal carers, family members and friends and the healthcare professionals that care for them. This work highlights the importance of asking people directly impacted by dementia and those caring for them about uncertainties with regards to medicines use and what research they want to inform optimizing the health and well-being of people living with dementia.

The grouping of summary questions into themes was performed primarily to assist with the review and presentation of the questions. However, the wide breadth of themes arising from the data shows the variety of different research areas within the field of quality use of medicines in people living with dementia. We identified themes about the awareness and education of both consumers and healthcare professionals, the healthcare system, the setting of residential aged care facilities, management of medicines in the home, polypharmacy, treatment of dementia, changed behaviors, and other medical conditions, specific adverse drug reactions and harms and others.

None of the summary questions identified in the present study were determined to be fully ‘answered’ in the literature. This was unsurprising as quality use of medicines in people living with dementia is an under researched and complex area [44]—both in the relationship between medicines and dementia and appropriate and safe use of medicines in this population. Clinical drug trials tend to exclude people with dementia, those who have more complex health issues (e.g., multiple medical conditions) and/or in later stages of the medical condition [45, 46]. It cannot, therefore, be assumed that the results of clinical trials are generalizable to people living with dementia, particularly those taking multiple medicines [47]. Evidence suggests that this population is at a higher risk of medicine-related toxicity due to changed pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, but the clinical importance of this is mostly unknown [48, 49]. Similarly, people living with dementia are often excluded from health services research owing to perceptions of inability to consent to participate in research, or take part in the processes required for the study [50, 51]. For example, Taylor et al. [52] found that 16% of original research in a leading geriatrics journal used recruitment methods that would prevent participation of people with cognitive impairment, and 29% of publications explicitly excluded this population. The authors also noted poor reporting regarding whether and how people with cognitive impairment were excluded [52].

Two previous groups (in the UK and Canada) have used the JLA method to conduct priority setting work on the broad topic of dementia. In their work, a small number of medicine specific questions arose, such as how to best treat (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) changed behaviors, long-term effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors, and how to support independence (including with respect to medicine-taking). While the majority of their unanswered questions did not explicitly mention medicines, many similarities exist with our themes and unanswered questions, such as aiming to achieve person-centered care, optimizing quality of life, staff training, and supporting people living with dementia to remain at home [31, 32].

It has been established that there is an important mismatch between research being conducted and research that consumers and healthcare professionals think should be prioritized. Crowe et al. compared the ‘Top 10’ priorities of the first 14 JLA Priority Setting Partnerships to a random sample of registered clinical trials over the same period. Medicine treatment was the focus of 86% of commercial registered trials, and 37% of non-commercial trials, yet was only the focus of 18% of consumer and healthcare professional priority research questions [3]. While our Priority Setting Partnership focused on the field of quality use of medicines, we similarly found that there were some questions related to the pharmacological treatment of dementia, but the majority covered a broad range of topics including the management of medicines, training of healthcare professionals, and how to optimize medicine use and minimize medicine-related harm.

Strengths and limitations

This study used a robust methodology developed by the JLA and employed for over 100 different health topics internationally. Additionally, the flexibility in data collection for the first survey enabled us to maximize responses from consumers and healthcare professionals across Australia.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we were limited to mostly distributing the survey and advertising the study online and our convenience sampling approach may have limited capturing the voices of people who are unfamiliar or unable to complete an online survey in English (such as people with moderate to severe cognitive impairment and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds). As this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic we adopted a risk minimization approach and chose not to conduct recruitment or data collection in person (considering the increased risk for people living with dementia [17]). We identified some groups as underrepresented in our online survey, such as those in a non-clinical role (e.g., administrators of residential aged care facilities) and people living in the Northern Territory. To address these gaps, key informant interviews were used, and existing documents reviewed. However, use of primarily Partner Organizations to recruit the key informants may have led to bias towards inclusion of people who are more informed about quality use of medicines issues. Some of the demographics of our population do reflect the broader target population, such as one third of the Australian population being culturally and linguistically diverse (26/30% consumers/healthcare professionals respectively of our respondents were not born in Australia), and the majority female respondents reflecting that women make up the greater part of the health and social sector workforce (especially pharmacists and nurses) [53], and that women make up the majority of carers [42]. Second, inherent limitations related to the survey methodology included not being able to determine a response rate, having no method to limit duplicate participation by a single participant, and not adjusting for missing data or non-responses. However, as our analysis was qualitative, and driven by the aim of identifying the broad range of possible research questions from a variety of people, these limitations are only likely to impact data concerning participant demographics. Third, we did not identify any new summary questions after the sixth key informant interview or after review of the relevant existing documents which could be considered as reaching data saturation. However, there were several summary questions which were only informed by a single respondent (and therefore may not fulfill other definitions of saturation such as degree of development of a code) [37]. Finally, while we employed a rapid review approach to evidence checking which is not as robust as a systematic review process, it was appropriate for this study given the high threshold for a question to be answered (i.e., if there was any doubt that the question had been answered, it was retained and considered an unanswered research question). Indeed, no questions were removed due to being answered. Additionally, the summary questions are not necessarily a single research question that could be answered in a single study and therefore, researchers acting on these unanswered summary questions will still need to review the existing literature when planning their future studies.

Research, clinical, and policy implications

National and international initiatives have highlighted the importance of ensuring quality use of medicines in older adults and people living with dementia. In June 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) released their report of ‘Medication Safety in Polypharmacy’ as a part of the current global patient safety challenge of ‘Medication Without Harm’. The WHO highlight that people living with dementia are a population to be targeted for medicine reviews as they are at risk due to polypharmacy [13]. In Australia, a Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety was established in October 2018 in response to concerns about the care of people living in residential aged care facilities, including the high prevalence of inappropriate antipsychotic medicine use in people living with dementia [43].

Solving national and international issues of medicine overuse and medicine-related harm will require research grounded in practice and informed by those who are most affected by them. The unanswered research questions identified in this study highlight areas of concern (such as medicine-related harm and the overuse of antipsychotics) and seek to find answers on how to solve these problems. For example, the theme of Changed Behaviours includes three questions that could direct the path of future research, including: asking when and how these medicines should be used (considering the type and stage of dementia); the most effective and safe way to reduce the use of antipsychotics; and if certain medicines increase the risk of changed behaviors. Additionally, questions in the Healthcare System and Person-Centred Care theme (such as how to achieve informed consent and shared decision making), Residential Aged Care Facilities theme (such as how to provide aged care staff with necessary knowledge and skills) and Polypharmacy, Complexity and Deprescribing theme (such as preventing prescribing cascades, optimal model of medicine reviews and how to achieve deprescribing) provide insight into how these issues could be addressed.

Conclusion

The findings from this study have great potential to provide benefits to people living with dementia and their carers by guiding researchers to align future studies in the field of quality use of medicines in dementia with the highlighted unanswered consumer and healthcare professional questions. Moreover, findings provide a consumer- and healthcare professional-centered foundation for researchers who are designing future research, while not replacing the need to include consumers and healthcare professionals in individual projects. By creating a list of unanswered questions relating to quality use of medicines driven by key stakeholders, future research will be inherently linked to optimizing care and quality of life for people living with dementia. Future work will involve further engagement via second survey and national workshop with consumers and healthcare professionals in Australia to determine the top 10 unanswered research questions about quality use of medicines in people living with dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate and acknowledge the input provided by Ann Pietsch, Timothy Pietsch, and Marie Wittwer as members of the Stakeholder Steering Group (other members of the Steering Group are listed as authors: LdlP, JT, SD, CW, JD, and RS). This work would not have been possible without the Steering Group.

We would like to acknowledge our Partner Organizations who supported the project including promotion of the surveys, dissemination of advertising materials, and identification of individuals suitable for key informant interviews: Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy, Australian Association of Gerontology, Australian College of Nurse Practitioners, Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation, Consumers Health Forum of Australia, Leading Age Services Australia, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Association, Speech Pathology Australia, The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia.

We acknowledge support from StepUp for Dementia Research in advertising the survey. StepUp for Dementia Research is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and implemented by a dedicated team at the University of Sydney

Proudly supported by the AAG Research Trust and the Dementia Australia Research Foundation - 2019 Strategic Research Grant.

ER was supported by a NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship (APP1105777), an NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP1195460), United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant and has received royalties for co-authoring a chapter on deprescribing in UpToDate and honorarium from the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia (leading workshops on deprescribing). MS was supported by a Dementia Centre for Research Collaboration Fellowship. TAN was supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship (APP1103860) and is currently supported by an NHMRC-Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) International Collaborative Research Grant (APP1154644), an NHMRC e-ASIA Joint Research Program Grant (APP2001548) and an NIH R01 Grant (AG064688). LMKE was supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship (APP1101788). JG-T was supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship (APP1107476). ECKT was supported by an NHMRC-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship (APP1107381). JKS was supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (APP1156439) and received grant funds from the Dementia Centre for Research Collaboration and Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy and honoraria from the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. LdlP, JD, JT, RS, and SD all received sitting fee payments for participating in this study as Steering Group members (paid to them via University of South Australia, funded by AAG Research Trust and the Dementia Australia Research Foundation Grant). SD has also received payments from Dementia Training Australia (for education), Biogen (Advisory Board member and support for attending meeting) and Roche (Advisory Board member). KC received payment for being an advisor for this study (paid to them via University of South Australia, funded by AAG Research Trust and the Dementia Australia Research Foundation Grant).

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/22-0827r2).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-220827.

REFERENCES

[1] | Evans I , Thornton H , Chalmers I , Glasziou P ((2011) ) Testing Treatments: Better Research for Better Healthcare, Pinter and Martin, London. |

[2] | Tallon D , Chard J , Dieppe P ((2000) ) Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 355: , 2037–2040. |

[3] | Crowe S , Fenton M , Hall M , Cowan K , Chalmers I ((2015) ) Patients’, clinicians’ and the research communities’ priorities for treatment research: There is an important mismatch. Res Involv Engagem 1: , 2. |

[4] | Chalmers I , Glasziou P ((2009) ) Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 374: , 86–89. |

[5] | Crowe S , Giles C ((2016) ) Making patient relevant clinical research a reality. BMJ 355: , i6627. |