Association of Alzheimer’s Disease with COVID-19 Susceptibility and Severe Complications: A Nationwide Cohort Study

Abstract

Background:

Identification of patients at high susceptibility and high risk of developing serious complications related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection is clinically important in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective:

To investigate whether patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are more susceptible to COVID-19 infection and whether they have a higher risk of developing serious complications.

Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed the Korean nationwide population-based COVID-19 dataset for participants who underwent real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays for COVID-19 between January 1 and June 4, 2020. A 1 : 3 ratio propensity score matching and binary logistic regression analysis were performed to investigate the association between AD and the susceptibility or severe complications (i.e., mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission, or death) of COVID-19.

Results:

Among 195,643 study participants, 5,725 participants had AD and 7,334 participants were diagnosed with COVID-19. The prevalence of participants testing positive for COVID-19 did not differ according to the presence of AD (p = 0.234). Meanwhile, AD was associated with an increased risk of severe COVID-19 complications (OR 2.25 [95% CI 1.54–3.28]). Secondary outcome analyses showed that AD patients had an increased risk for mortality (OR 3.09 [95% CI 2.00–4.78]) but were less likely to receive mechanical ventilation (OR 0.42 [95% CI 0.20–0.87]).

Conclusion:

AD was not associated with increased susceptibility to COVID-19 infection, but was associated with severe COVID-19 complications, especially with mortality. Early diagnosis and active intervention are necessary for patients with AD suspected COVID-19 infection.

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a novel coronavirus that is designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. During this ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the highly contagious viral illness continues to spread around the world, and it is the most crucial global health threat of the 21st century. Although the majority of people infected with COVID-19 (about 75–80%) have mild symptoms or are asymptomatic, a non-ignorable percentage of patients infected with COVID-19 can develop severe complications such as respiratory failure, which often require mechanical ventilation and intensive care [2]. Also, mild symptoms of COVID-19 can suddenly turn into severe symptoms in patients affected by the disease. Due to its high infectivity and related complications, COVID-19 in recent times, has become one of the leading causes of death worldwide [3]. Therefore, identification of patients at high susceptibility and high risk of developing serious complications related to COVID-19 infection is clinically important for early treatment and proper allocation of medical resources. Several epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that the presence and number of underlying conditions and medical illnesses are strongly associated with susceptibility to COVID-19 and to poor prognosis after COVID-19 infection [4, 5].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia and is one of the major causes of disability, dependency, and death among older people globally [6]. Patients with AD are frequently accompanied by multiple comorbidities and they are extremely vulnerable to several medical conditions [7, 8]. In particular, infection such as pneumonia is a common complication in AD patients and it is one of the main causes of death [9, 10]. Patients with AD may not properly complain of early symptoms of COVID-19 infection due to cognitive decline and language problems [11]. Therefore, the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 infection could be delayed in AD patients, which may eventually lead to poor prognosis after COVID-19 infection [12]. Moreover, dysregulated immunity in AD can predispose patients to COVID-19 infection and complications [13–15]. Aging and delirium conditions associated with AD may also increase the vulnerability to COVID-19 infection [16, 17]. In the current study, we investigated whether patients with AD were more susceptible to COVID-19 infection compared to non-AD individuals in the general population, based on a nationwide population-based COVID-19 dataset. We also investigated whether AD patients infected with COVID-19 were more likely to experience severe complications compared to non-AD patients with COVID-19 infection.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This retrospective observational study was based on a nationwide population-based COVID-19 dataset from South Korea. Since South Korea has a public and single-payer health insurance system, the National Health Information Database by National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) contains all health care service information on hospital visit, admission, diagnoses (recorded using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)-10 codes), procedures, prescriptions, demographics, and mortality of the whole Korean population [18, 19]. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and NHIS released the nationwide COVID-19 dataset consisting of all Koreans who underwent real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays of nasal and pharyngeal swabs for COVID-19 from January 1 to June 4, 2020 for academic research [20]. The real-time RT-PCR assays kit followed the World Health Organization guidelines, and it was validated by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [21]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution (Seoul Hospital Ewha Womans University College of Medicine 2020-10-021), and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective analysis and use of the fully anonymized dataset.

Alzheimer’s disease

The presence of AD was defined when patients had ICD-10 codes F00 and G30 as the main or secondary diagnosis with the prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) or memantine for the treatment of AD prior to COVID-19 RT-PCR test. Patients with vascular dementia (F01) or stroke (I60-63) were excluded from the study to rule out possible confounding factors that were present with vascular dementia [22, 23].

Study outcome

We investigated (1) whether patients with AD were more susceptible to COVID-19 infection, and (2) whether AD was associated with a poor prognosis in COVID-19 infected patients. The study outcomes were defined as (1) positivity in testing of COVID-19 and (2) the development of severe complications after COVID-19 infection. The development of severe complications was defined as either mechanical ventilation, admission to the intensive care unit, or death within 2 months after the diagnosis of COVID-19. Based on the health claim database, mechanical ventilation was identified by the presence of related claim codes for mechanical ventilation (M5850, M5857, M5858, and M5860) [24]. The admission to the intensive care unit was defined as related claim codes (AH110, AH150, AH180-85, AH190-5, AH210, AH250, AH280-9, AH28A, AH290-9, AH380-9, AH38A, AH390-9, AH501, AJ001–AJ011, AJ020-1, AJ031, AJ100-390, AJ2A0, AJ3A0, AJ500-590, V5100, V5200, V5210-20, and V5500-5520). Mortality data were provided by the NHIS, and they had been previously validated [25, 26].

Covariates

We acquired demographic information regarding sex, age at COVID-19 RT-PCR test, and household income level (tertiles). In the COVID-19 dataset, age was presented in 10-year increments for privacy reasons. In the analysis, the age group was dichotomized using a cutoff of 60 years. The presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, asthma, chronic kidney disease, and malignancy were collected as covariates, and they were determined based on the health claims database [27]. Definition of covariates are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Statistical analyses

Comparative analyses of COVID-19 test positivity and the development of severe complications of COVID-19 infection were performed in both the unmatched cohort and the propensity score-matched cohorts. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using the greedy nearest-neighbor algorithm to balance all collected covariates in both groups with and without AD. To evaluate the susceptibility to COVID-19 infection according to AD, a 1 : 3 ratio PSM was performed among study participants who received the COVID-19 RT-PCR test. To investigate the association of AD with severe complications of COVID-19 infection, a 1 : 3 ratio PSM was performed among COVID-19 positive patients. To check whether PSM was performed properly, the standardized differences of each variable included in the PSM were calculated accordingly. If absolute value of the standardized differences were less than 0.20, the PSM was considered appropriate [28].

Binary logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of AD for susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and the development of severe complications in the unmatched cohort and PSM cohorts, respectively. We additionally evaluated associations between AD and individual components in severe complications of COVID-19 infection, that is, mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit, and death. Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SAS 9.4 version (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Susceptibility to COVID-19 infection in patients with AD

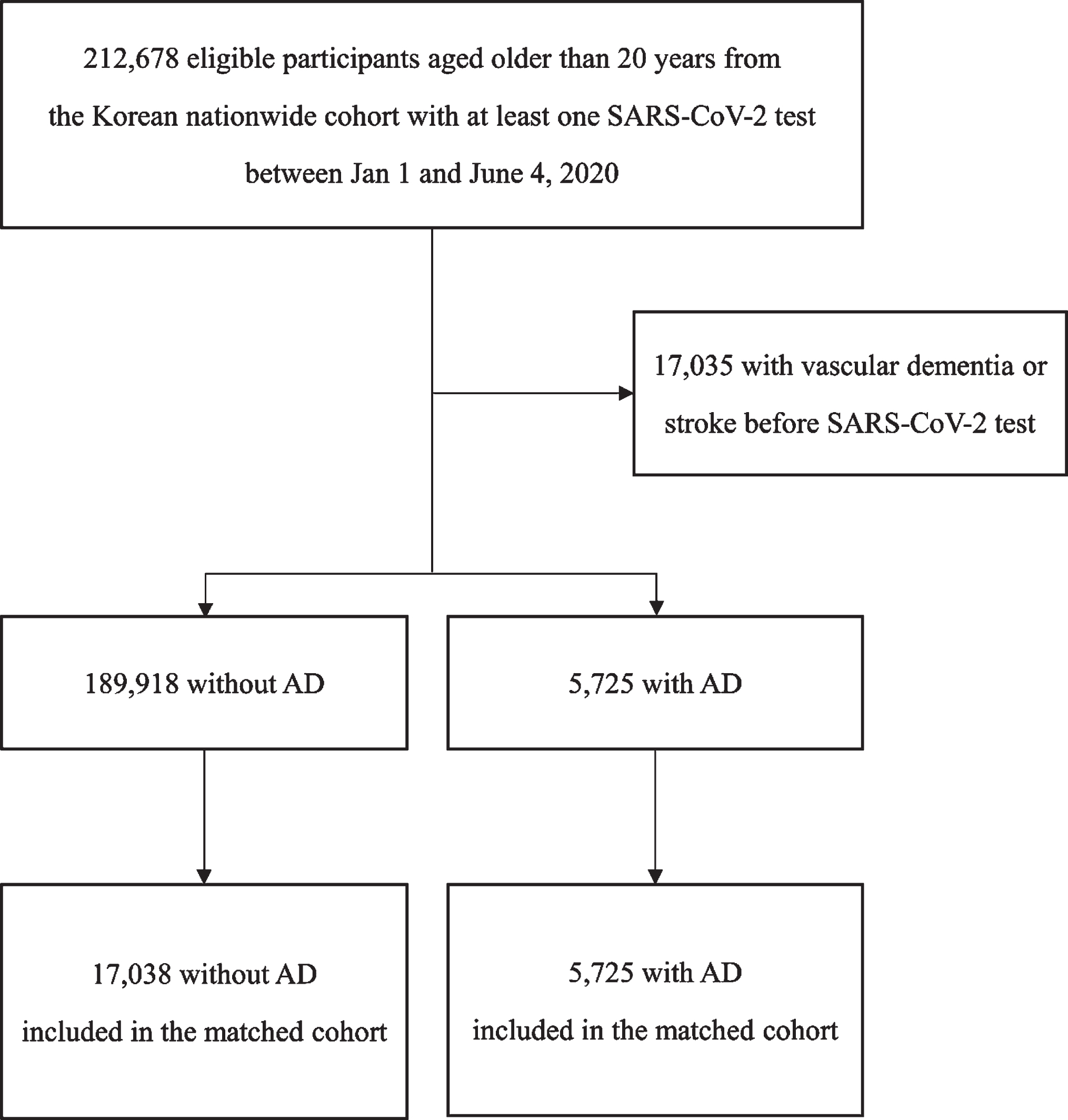

The Korean nationwide COVID-19 dataset included 212,678 participants aged > 20 years who underwent at least one SARS-CoV-2 test between January 1 and June 4, 2020 (Fig. 1). After excluding 17,035 individuals with a history of vascular dementia or stroke before the COVID-19 RT-PCR test, 189,918 individuals without AD and 5,725 (2.9%) individuals with AD were included in the unmatched cohort (Table 1). When we evaluated the susceptibility to COVID-19 infection in the unmatched cohort, COVID-19 RT-PCR positivity did not differ according to the presence of AD (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.75–1.01, p = 0.071; Table 2). In the PSM cohort (5,725 individuals with AD and 17,038 individuals without AD; Table 1), COVID-19 RT-PCR positivity also did not differ according to the presence or absence of AD (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.94–1.31, p = 0.234; Table 2).

Fig. 1

Flow chart depicting patient selection for analysis of the susceptibility to COVID-19 infection. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of participants who underwent COVID-19 test with and without Alzheimer’s disease before and after propensity score matching

| Variable | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | Standardized difference* | ||

| Without AD (N = 189,918) | With AD (N = 5,725) | Without AD (N = 17,038) | With AD (N = 5,725) | ||

| Sex, male | 88,955 (46.84) | 2,108 (36.82) | 6,575 (38.59) | 2,108 (36.82) | 0.0361 |

| Age, y | 0.0002 | ||||

| <60 | 139,022 (73.20) | 90 (1.57) | 266 (1.56) | 90 (1.57) | |

| 60–69 | 23,904 (12.59) | 314 (5.48) | 940 (5.52) | 314 (5.48) | |

| ≥70 | 26,992 (14.21) | 5,321 (92.94) | 15,832 (92.92) | 5,321 (92.94) | |

| Household income | –0.0383 | ||||

| T1 | 62,995 (33.17) | 2,428 (42.41) | 6,809 (39.96) | 2,428 (42.41) | |

| T2 | 65,610 (34.55) | 1,226 (21.41) | 3,929 (23.06) | 1,226 (21.41) | |

| T3 | 61,313 (32.28) | 2,071 (36.17) | 6,300 (36.98) | 2,071 (36.17) | |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | 47,825 (25.18) | 4,256 (74.34) | 12,666 (74.34) | 4,256 (74.34) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20,766 (10.93) | 1,840 (32.14) | 5,501 (32.29) | 1,840 (32.14) | 0.0037 |

| Coronary artery disease | 10,445 (5.50) | 947 (16.54) | 2,726 (16.00) | 947 (16.54) | –0.0176 |

| Heart failure | 13,456 (7.09) | 1,669 (29.15) | 4,714 (27.67) | 1,669 (29.15) | –0.0403 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4,409 (2.32) | 561 (9.80) | 1,525 (8.95) | 561 (9.80) | –0.0360 |

| Asthma | 11,843 (6.24) | 781 (13.64) | 2,192 (12.87) | 781 (13.64) | –0.0262 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 13,925 (7.33) | 1,249 (21.82) | 3,647 (21.41) | 1,249 (21.82) | –0.0119 |

| Malignancy | 25,437 (13.39) | 1,112 (19.42) | 3,687 (21.64) | 1,112 (19.42) | 0.0600 |

| CCI | 2.43±2.54 | 5.00±2.75 | 5.00±2.96 | 5.00±2.75 | –0.0003 |

Data are presented as number with percentage or mean with standard deviation. *A standardized difference between groups with and without Alzheimer’s disease after propensity score matching. All absolute value of standardized differences are less than 0.20, suggesting that covariates are balanced between the groups after propensity score matching. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; T, tertile; CCI, Charlson Commodity index; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2

The proportion of participants testing positive for COVID-19 according to Alzheimer’s disease before and after propensity score matching

| Variable | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | ||||||

| Without AD (N = 189,918) | With AD (N = 5,725) | OR [95% CI] | p | Without AD (N = 17,038) | With AD (N = 5,725) | OR [95% CI] | p | |

| COVID-19 | 0.071 | 0.234 | ||||||

| Negative (-) | 182773 (96.24) | 5536 (96.70) | Ref | 16529 (97.01) | 5536 (96.70) | Ref | ||

| Positive (+) | 7145 (3.76) | 189 (3.30) | 0.87 [0.75–1.01] | 509 (2.99) | 189 (3.30) | 1.11 [0.94–1.31] | ||

Data are presented as number with percentage. OR and 95% CI are derived from univariate binary logistic regression analysis for COVID-19 test positivity. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Prognosis of COVID-infection in patients with AD

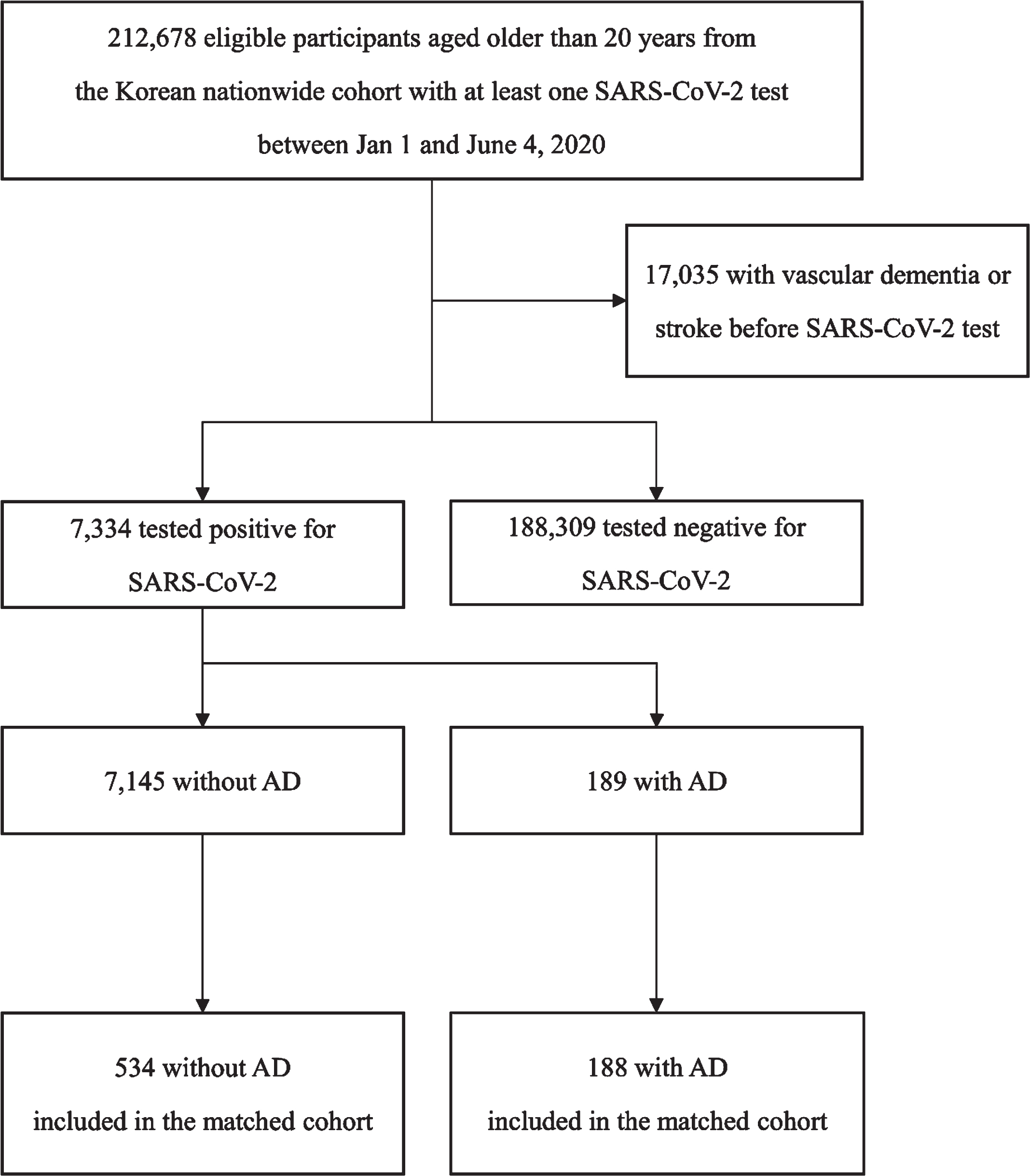

The COVID-19 dataset consisted of 7,334 patients positive for the COVID-19 RT-PCR test (Fig. 2). Among the 7,334 COVID-19 patients, 189 (2.5%) had AD (Table 3). During the two months after COVID-19 infection, 351 (4.8%) patients developed severe complications (composite of mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit, or death). The number of patients infected with COVID-19 who received mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission, and who died was 155 (2.1%), 223 (3.0%), and 160 (2.2%), respectively. In the unmatched cohort of patients with COVID-19 infection, AD was associated with a high risk for the development of severe complications (OR 11.26, 95% CI 8.12–15.62, p < 0.001; Table 4). In the PSM cohort with COVID-19 patients (188 patients with AD and 534 patients without AD), the finding of a significant association between AD and severe complications of COVID-19 was consistent (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.54–3.28, p < 0.001; Table 4).

Fig. 2

Flow chart depicting patient selection for analysis of prognosis in patients with COVID-19 infection. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; AD, Alzheimer’s disease.

Table 3

Baseline characteristics of COVID-19 patients with and without Alzheimer’s disease before and after propensity score matching

| Variable | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | Standardized difference* | ||

| Without AD (N = 7,145) | With AD (N = 189) | Without AD (N = 534) | With AD (N = 188) | ||

| Sex, male | 2,817 (39.43) | 58 (30.69) | 199 (37.27) | 58 (30.85) | 0.1350 |

| Age, y | 0.0040 | ||||

| <60 | 5,416 (75.8) | 5 (2.65) | 15 (2.81) | 5 (2.66) | |

| 60–69 | 1,100 (15.40) | 16 (8.47) | 45 (8.43) | 16 (8.51) | |

| ≥60 | 629 (8.80) | 168 (88.89) | 474 (88.76) | 167 (88.83) | |

| Household income | -0.0516 | ||||

| T1 | 3,071 (42.98) | 87 (46.03) | 240 (44.94) | 86 (45.74) | |

| T2 | 2,071 (28.99) | 46 (24.34) | 116 (11.72) | 46 (24.47) | |

| T3 | 2,003 (28.03) | 56 (29.63) | 178 (33.33) | 56 (29.79) | |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension | 1,318 (18.45) | 121 (64.02) | 333 (62.36) | 120 (63.83) | -0.0337 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 576 (8.06) | 59 (31.22) | 160 (29.96) | 58 (30.85) | -0.0374 |

| Coronary artery disease | 236 (3.30) | 23 (12.17) | 60 (11.24) | 23 (12.23) | -0.0379 |

| Heart failure | 306 (4.28) | 52 (27.51) | 113 (21.16) | 51 (27.13) | -0.1721 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 74 (1.04) | 20 (10.58) | 30 (5.62) | 19 (10.11) | -0.1960 |

| Asthma | 294 (4.11) | 13 (6.88) | 32 (5.99) | 13 (6.91) | -0.0406 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 343 (4.80) | 21 (11.11) | 51 (9.55) | 21 (11.17) | -0.0603 |

| Malignancy | 420 (5.88) | 27 (14.29) | 72 (13.48) | 27 (14.36) | -0.0295 |

| CCI | 1.80±1.86 | 4.06±1.97 | 3.71±2.29 | 4.06±1.97 | 0.1800 |

Data are presented as number with percentage or mean with standard deviation. *A standardized difference between groups with and without Alzheimer’s disease after propensity score matching. All absolute value of standardized differences are less than 0.20, suggesting that covariates are balanced between the groups after propensity score matching. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; T, tertile; CCI, Charlson Commodity index; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4

Severe complication of COVID-19 patients with and without Alzheimer’s disease before and after propensity score matching

| Outcomes | Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | ||||||

| Without AD (N = 7145) | With AD (N = 189) | OR [95% CI] | P | Without AD (N = 534) | With AD (N = 188) | OR [95% CI] | p | |

| Severe complication of COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 146 (2.04) | 9 (4.76) | 2.40 [1.20–4.78] | 0.013 | 57 (10.67) | 9 (4.79) | 0.42 [0.20–0.87] | 0.019 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 203 (2.84) | 20 (10.58) | 4.05 [2.50–6.57] | <0.001 | 60 (11.24) | 20 (10.64) | 0.94 [0.55–1.61] | 0.822 |

| Death | 113 (1.58) | 47 (24.87) | 20.60 [14.11–30.08] | <0.001 | 52 (9.74) | 47 (25.00) | 3.09 [2.00–4.78] | <0.001 |

| Composite of outcome | 290 (4.06) | 61 (32.28) | 11.26 [8.12–15.62] | <0.001 | 94 (17.60) | 61 (32.45) | 2.25 [1.54–3.28] | <0.001 |

Data are presented as number with percentage. OR and 95% CI are derived from univariate binary logistic regression analysis for outcomes with COVID-19 infection. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

We performed secondary outcome analyses to determine the association between the individual components of severe complications and AD (Table 4). In the unmatched cohort, AD was associated with the risk of mechanical ventilation (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.20–4.78, p = 0.013), intensive care unit admission (OR 4.05, 95% CI 2.50–6.57, p < 0.001), and mortality after COVID-19 infection (OR 20.60, 95% CI 14.11–30.08, p < 0.001). In the PSM cohort with COVID-19 patients, AD was associated with a high risk of mortality (OR 3.09, 95% CI 2.00–4.78, p < 0.001). However, there was no difference in the rate of admission to the intensive care unit according to the presence of AD (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.55–1.61, p = 0.822). Additionally, mechanical ventilation rate was lower in AD patients after COVID-19 infection (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.20–0.87, p = 0.019) in the PSM cohort.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated whether patients with AD were more susceptible to COVID-19 and whether they had a poor prognosis. The major findings were as follows: 1) Individuals with AD were not more susceptible to COVID-19 infection; 2) Individuals with AD had a higher risk of serious complications, particularly death, when infected with COVID-19 than those without AD. These findings suggest that patients with AD should be more cautious not to be infected with COVID-19 because of a higher risk of severe complications upon infection. Strict preventive management or close monitoring for complications would be needed for patients with AD who infected with COVID-19.

The global pandemic of COVID-19 has not only caused many casualties, but it also has a major impact on social, economic, and public health aspects around the world. Therefore, early detection of COVID-19-infected patients at high risk of serious complications or death is important for the implementation of appropriate therapeutic strategies and the optimization of hospital resource reallocation. In this study, we found that patients with AD were not more susceptible to COVID-19 infection than non-AD individuals but were associated with an increased risk of serious complications upon COVD-19 infection. The evidence to date indicates that the elderly with AD or dementia have a high risk of contracting COVID-19 and, once infected, they have a high risk of severe COVID-19 and mortality [29–32]. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association between AD and COVID-19 susceptibility and serious complications. First, risk factors for AD, including old age, underlying comorbidities, and long-term care facilities, are also risk factors for COVID-19 infection and severe COVID-19 [33], making patients with dementia more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection. Second, the increased mortality of patients with AD may be related to socio-clinical factors. Older patients infected with COVID-19 tend to present with atypical non-respiratory symptoms such as delirium or isolated functional decline [34]. Decreased communication ability in patients with AD can also delay the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and can underestimate the disease severity [35]. Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with the manifestation and exacerbation of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with AD [36], which can have detrimental effects on mortality [37]. Third, the pathomechanisms underlying AD share the mechanisms that increase the susceptibility, morbidity, and mortality associated with COVID-19 infection [12, 31, 32]. Elevated plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6, are observed both in patients with AD and COVID-19-infected patients with increased mortality [38]. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ɛ4 allele is a common risk factor for AD, and some evidence has shown that individuals with APOE ɛ4/ɛ4 homozygote have higher COVID-19 susceptibility and fatality than those with other genotypes [39, 40]. A genetic variant of oligoadenylate synthetase 1, known to be associated with severe outcome with COVID-19 infection, is also associated with an increased risk for AD [31]. Moreover, older people with dementia would have a condition called immune senescence [41], which leads to a reduced ability to respond to new antigens and hinders the fight against infections [42].

In terms of the susceptibility of AD patients to COVID-19 infection, discrepancies with previous studies may be due to differences in study designs, limited time periods, and ethnic backgrounds. In particular, our study included patients diagnosed with AD who had received anti-dementia medications based on the health claims database. Therefore, patients with AD who did not receive medication could have been omitted in our study. The clinical heterogeneity of AD could not be taken into account when analyzing the data due to the lack of information in the health claims database [43, 44]. Moreover, detailed information about the severity of AD could not be obtained since our dataset did not cover cognitive function assessment, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale. Further analysis by stratification of dementia severity is needed to draw firm conclusions about the susceptibility of dementia patients to COVID-19 infection. Alternatively, the presence of early stages of AD, which is not severe enough to require care in nursing facilities, can affect lifestyles and reduce exposure to infectious pathogens by way of reduction in the times these patients go outside their homes. In this context, a recent nationwide cohort study demonstrated that the presence of mental illness is not inherently associated with increased susceptibility to COVID-19 infection, but it is associated with worse clinical pathophysiology [20].

The main result of this study on the prognosis of AD patients infected with COVID-19 is in line with previous literature [29, 30, 45, 46], showing that AD is associated with increased mortality after COVID-19 infection. As discussed above, AD shares risk factors and the pathophysiology of poor clinical outcomes associated with COVID-19 infection. Moreover, AD can lead to social isolation, which subsequently makes it difficult for AD patients to access the health care system, and as a vicious cycle, social isolation can worsen a patient’s underlying dementia [20, 47]. Interestingly, we found that AD was associated with a higher risk for mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit admission in the unmatched cohort, but not in propensity score-matched cohort controlling for major known comorbidities. These findings suggest that medical comorbidities other than dementia (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and respiratory disease), which were more prevalent in AD patients than non-AD populations in the unmatched cohort, may make a greater contribution to worsening of the health status of patients or impact the COVID-19 severity when they become infected with COVID-19 [48, 49]. In particular, patients with AD were less likely to receive mechanical ventilation in the propensity score-matched cohort. This may be because patients with AD would not want active interventions such as mechanical ventilation. Nevertheless, AD was consistently an independent risk factor for increased mortality after COVID-19 infection in both unmatched and matched cohorts, indicating that close monitoring and active intervention are necessary for dementia patients with COVID-19 infection.

Our study had some limitations. First, the causal relationship could not be proven since our study had a retrospective cohort study design. Second, it was difficult to generalize our results to the overall ethnicity since our dataset consisted only of the general Korean population. Third, this study was conducted at the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, and future studies would be needed to investigate the impact of recently emerged variants such as the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) and the Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) on patients with dementia.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrated that AD was not associated with increased susceptibility to COVID-19 infection, but it was associated with an increased risk of severe complications in patients with COVID-19. These findings suggest that clinicians and caregivers should be aware that patients with AD have poor clinical outcomes related to COVID-19 infection and they should be given priority in terms of treatment to avoid severe complications. A larger prospective cohort study is needed to draw a firm conclusion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (grant number: NRF-2021R1F1A1048113, NRF-2021R1I1A1A01059868, NRF-2021R1I1A1A01059678, and NRF-2020R1I1A1A01060447).

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/22-0031r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-220031.

REFERENCES

[1] | Wiersinga WJ , Rhodes A , Cheng AC , Peacock SJ , Prescott HC ((2020) ) Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. JAMA 324: , 782–793. |

[2] | Tian S , Hu N , Lou J , Chen K , Kang X , Xiang Z , Chen H , Wang D , Liu N , Liu D , Chen G , Zhang Y , Li D , Li J , Lian H , Niu S , Zhang L , Zhang J ((2020) ) Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. J Infect 80: , 401–406. |

[3] | Koh HK , Geller AC , VanderWeele TJ ((2021) ) Deaths from COVID-19. JAMA 325: , 133–134. |

[4] | Chen T , Wu D , Chen H , Yan W , Yang D , Chen G , Ma K , Xu D , Yu H , Wang H , Wang T , Guo W , Chen J , Ding C , Zhang X , Huang J , Han M , Li S , Luo X , Zhao J , Ning Q ((2020) ) Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. BMJ 368: , m1091. |

[5] | Jordan RE , Adab P , Cheng KK ((2020) ) Covid-19: Risk factors for severe disease and death. , m. BMJ 368: , 1198. |

[6] | Alzheimer’s Association ((2021) ) 2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 17: , 327–406. |

[7] | Bunn F , Burn A-M , Goodman C , Rait G , Norton S , Robinson L , Schoeman J , Brayne C ((2014) ) Comorbidity and dementia: A scoping review of the literature. BMC Med 12: , 192–192. |

[8] | Wang JH , Wu YJ , Tee BL , Lo RY ((2018) ) Medical comorbidity in Alzheimer’s disease: A nested case-control study. J Alzheimers Dis 63: , 773–781. |

[9] | Kukull WA , Brenner DE , Speck CE , Nochlin D , Bowen J , McCormick W , Teri L , Pfanschmidt ML , Larson EB ((1994) ) Causes of death associated with Alzheimer disease: Variation by level of cognitive impairment before death. J Am Geriatr Soc 42: , 723–726. |

[10] | Kalia M ((2003) ) Dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Metabolism 52: , 36–38. |

[11] | Palmer K , Monaco A , Kivipelto M , Onder G , Maggi S , Michel JP , Prieto R , Sykara G , Donde S ((2020) ) The potential long-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on patients with non-communicable diseases in Europe: Consequences for healthy ageing. Aging Clin Exp Res 32: , 1189–1194. |

[12] | Xia X , Wang Y , Zheng J ((2021) ) COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s disease: How one crisis worsens the other. Transl Neurodegener 10: , 15. |

[13] | Shi M , Chu F , Tian X , Aerqin Q , Zhu F , Zhu J (2021) Role of adaptive immune and impacts of risk factors on adaptive immune in Alzheimer’s disease: Are immunotherapies effective or off-target? Neuroscientist, doi:10.1177/1073858420987224. |

[14] | Shi M , Li C , Tian X , Chu F , Zhu J ((2021) ) Can control infections slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s disease? Talking about the role of infections in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 13: , 685863. |

[15] | Lutshumba J , Nikolajczyk BS , Bachstetter AD ((2021) ) Dysregulation of systemic immunity in aging and dementia. Front Cell Neurosci 15: , 652111. |

[16] | Hariyanto TI , Putri C , Hananto JE , Arisa J , Fransisca VSR , Kurniawan A ((2021) ) Delirium is a good predictor for poor outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Psychiatr Res 142: , 361–368. |

[17] | Singhal S , Kumar P , Singh S , Saha S , Dey AB ((2021) ) Clinical features and outcomes of COVID-19 in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 21: , 321. |

[18] | Seong SC , Kim YY , Park SK , Khang YH , Kim HC , Park JH , Kang HJ , Do CH , Song JS , Lee EJ , Ha S , Shin SA , Jeong SL ((2017) ) Cohort profile: The National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open 7: , e016640. |

[19] | Chang Y , Lee JS , Lee KJ , Woo HG , Song TJ ((2020) ) Improved oral hygiene is associated with decreased risk of new-onset diabetes: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Diabetologia 63: , 924–933. |

[20] | Lee SW , Yang JM , Moon SY , Yoo IK , Ha EK , Kim SY , Park UM , Choi S , Lee SH , Ahn YM , Kim JM , Koh HY , Yon DK ((2020) ) Association between mental illness and COVID-19 susceptibility and clinical outcomes in South Korea: A nationwide cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 7: , 1025–1031. |

[21] | Lee SW , Ha EK , Yeniova A , Moon SY , Kim SY , Koh HY , Yang JM , Jeong SJ , Moon SJ , Cho JY , Yoo IK , Yon DK ((2021) ) Severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 associated with proton pump inhibitors: A nationwide cohort study with propensity score matching. Gut 70: , 76–84. |

[22] | Jeong SM , Shin DW , Lee JE , Hyeon JH , Lee J , Kim S ((2017) ) Anemia is associated with incidence of dementia: A national health screening study in Korea involving 37,900 persons. Alzheimers Res Ther 9: , 94. |

[23] | Jang JW , Park JH , Kim S , Lee SH , Lee SH , Kim YJ ((2021) ) Prevalence and incidence of dementia in South Korea: A nationwide analysis of the National Health Insurance Service Senior Cohort. J Clin Neurol 17: , 249–256. |

[24] | Son M , Seo J , Yang S ((2020) ) Association between renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and COVID-19 infection in South Korea. Hypertension 76: , 742–749. |

[25] | Song TJ , Jeon J , Kim J ((2021) ) Cardiovascular risks of periodontitis and oral hygiene indicators in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab 47: , 101252. |

[26] | Lee J , Lee JS , Park S-H , Shin SA , Kim K ((2016) ) Cohort Profile: The National Health Insurance Service–National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol 46: , e15–e15. |

[27] | Chang Y , Woo HG , Lee JS , Song TJ ((2021) ) Better oral hygiene is associated with lower risk of stroke. J Periodontol 92: , 87–94. |

[28] | Cohen J ((1988) ) Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Earlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. |

[29] | Numbers K , Brodaty H ((2021) ) The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 17: , 69–70. |

[30] | Hariyanto TI , Putri C , Arisa J , Situmeang RFV , Kurniawan A ((2021) ) Dementia and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 93: , 104299. |

[31] | Magusali N , Graham AC , Piers TM , Panichnantakul P , Yaman U , Shoai M , Reynolds RH , Botia JA , Brookes KJ , Guetta-Baranes T , Bellou E , Bayram S , Sokolova D , Ryten M , Sala Frigerio C , Escott-Price V , Morgan K , Pocock JM , Hardy J , Salih DA ((2021) ) A genetic link between risk for Alzheimer’s disease and severe COVID-19 outcomes via the OAS1 gene. Brain 144: , 3727–3741. |

[32] | Tahira AC , Verjovski-Almeida S , Ferreira ST ((2021) ) Dementia is an age-independent risk factor for severity and death in COVID-19 inpatients. Alzheimers Dement 17: , 1818–1831. |

[33] | Williamson EJ , Walker AJ , Bhaskaran K , Bacon S , Bates C , Morton CE , Curtis HJ , Mehrkar A , Evans D , Inglesby P , Cockburn J , McDonald HI , MacKenna B , Tomlinson L , Douglas IJ , Rentsch CT , Mathur R , Wong AYS , Grieve R , Harrison D , Forbes H , Schultze A , Croker R , Parry J , Hester F , Harper S , Perera R , Evans SJW , Smeeth L , Goldacre B ((2020) ) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584: , 430–436. |

[34] | D’Adamo H , Yoshikawa T , Ouslander JG ((2020) ) Coronavirus disease 2019 in geriatrics and long-term care: The ABCDs of COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc 68: , 912–917. |

[35] | Bianchetti A , Rozzini R , Guerini F , Boffelli S , Ranieri P , Minelli G , Bianchetti L , Trabucchi M ((2020) ) Clinical presentation of COVID19 in dementia patients. J Nutr Health Aging 24: , 560–562. |

[36] | Brown EE , Kumar S , Rajji TK , Pollock BG , Mulsant BH ((2020) ) Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28: , 712–721. |

[37] | Diwell RA , Davis DH , Vickerstaff V , Sampson EL ((2018) ) Key components of the delirium syndrome and mortality: Greater impact of acute change and disorganised thinking in a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 18: , 24. |

[38] | Chen X , Zhao B , Qu Y , Chen Y , Xiong J , Feng Y , Men D , Huang Q , Liu Y , Yang B , Ding J , Li F ((2020) ) Detectable serum severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral load (RNAemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 level in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 71: , 1937–1942. |

[39] | Kuo CL , Pilling LC , Atkins JL , Masoli JAH , Delgado J , Kuchel GA , Melzer D ((2020) ) ApoE e4e4 genotype and mortality with COVID-19 in UK Biobank. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75: , 1801–1803. |

[40] | Finch CE , Kulminski AM ((2021) ) The ApoE locus and COVID-19: Are we going where we have been? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 76: , e1–e3. |

[41] | Aiello A , Farzaneh F , Candore G , Caruso C , Davinelli S , Gambino CM , Ligotti ME , Zareian N , Accardi G ((2019) ) Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: How to oppose aging strategically? A review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Front Immunol 10: , 2247. |

[42] | Bonanad C , García-Blas S , Tarazona-Santabalbina F , Sanchis J , Bertomeu-González V , Fácila L , Ariza A , Núñez J , Cordero A ((2020) ) The effect of age on mortality inpatients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis with 611,583 subjects. J Am Med Dir Assoc 21: , 915–918. |

[43] | Lam B , Masellis M , Freedman M , Stuss DT , Black SE ((2013) ) Clinical, imaging, and pathological heterogeneity of the Alzheimer’s disease syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther 5: , 1. |

[44] | Ferreira D , Nordberg A , Westman E ((2020) ) Biological subtypes of Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 94: , 436–448. |

[45] | Kim YJ , Jee Y , Park S , Ha EH , Jo I , Lee HW , Song MS ((2021) ) Mortality risk within 14 days after coronavirus disease 2019 diagnosis in dementia patients: A nationwide analysis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 50: , 425–436. |

[46] | Wang SM , Park SH , Kim NY , Kang DW , Na HR , Um YH , Han S , Park SS , Lim HK ((2021) ) Association between dementia and clinical outcome after COVID-19: A nationwide cohort study with propensity score matched control in South Korea. Psychiatry Investig 18: , 523–529. |

[47] | Kyoung DS , Lee J , Nam H , Park MH ((2021) ) Dementia and COVID-19 Mortality in South Korea. Dement Neurocogn Disord 20: , 38–40. |

[48] | Grivas P , Khaki AR , Wise-Draper TM , French B , Hennessy C , Hsu CY , Shyr Y , Li X , Choueiri TK , Painter CA , Peters S , Rini BI , ThompsonMA BI , Mishra S , Rivera DR , Acoba JD , Abidi MZ , Bakouny Z , Bashir B , Bekaii-Saab T , Berg S , Bernicker EH , Bilen MA , Bindal P , Bishnoi R , Bouganim N , Bowles DW , Cabal A , Caimi PF , Chism DD , Crowell J , Curran C , Desai A , Dixon B , Doroshow DB , Durbin EB , Elkrief A , Farmakiotis D , Fazio A , Fecher LA , Flora DB , Friese CR , Fu J , Gadgeel SM , Galsky MD , Gill DM , Glover MJ , Goyal S , Grover P , Gulati S , Gupta S , Halabi S , Halfdanarson TR , Halmos B , Hausrath DJ , Hawley JE , Hsu E , Huynh-Le M , Hwang C , Jani C , Jayaraj A , Johnson DB , Kasi A , Khan H , Koshkin VS , Kuderer NM , Kwon DH , Lammers PE , Li A , Loaiza-Bonilla A , Low CA , Lustberg MB , Lyman GH , McKay RR , McNair C , Menon H , Mesa RA , Mico V , Mundt D , Nagaraj G , Nakasone ES , Nakayama J , Nizam A , Nock NL , Park C , Patel JM , Patel KG , Peddi P , Pennell NA , Piper-Vallillo AJ , Puc M , Ravindranathan D , Reeves ME , Reuben DY , Rosenstein L , Rosovsky RP , Rubinstein SM , Salazar M , Schmidt AL , Schwartz GK , Shah MR , Shah SA , Shah C , Shaya JA , Singh SRK , Smits M , Stockerl-Goldstein KE , Stover DG , Streckfuss M , Subbiah S , Tachiki L , Tadesse E , Thakkar A , Tucker MD , Verma AK , Vinh DC , Weiss M , Wu JT , Wulff-Burchfield E , Xie Z , Yu PP , Zhang T , Zhou AY , Zhu H , Zubiri L , Shah DP , Warner JL , Lopes G ((2021) ) Association of clinical factors and recent anticancer therapy withCOVID-19 severity among patients with cancer: A report from theCOVID-19 and Cancer Consortium. Ann Oncol 32: , 787–800. |

[49] | Kwenandar F , Japar KV , Damay V , Hariyanto TI , Tanaka M , Lugito NPH , Kurniawan A ((2020) ) Coronavirus disease 2019 and cardiovascular system: A narrative review. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 29: , 100557. |