Hispanic Perspectives on Parkinson’s Disease Care and Research Participation

Abstract

Background:

Hispanics are under-represented in Parkinson’s disease (PD) research despite the importance of diversity for results to apply to a wide range of patients.

Objective:

To investigate the perspective of Hispanic persons with Parkinson disease (PWP) regarding awareness, interest, and barriers to participation in research.

Methods:

We developed and administered a survey and qualitative interview in English and Spanish. For the survey, 62 Hispanic and 38 non-Hispanic PWP linked to a tertiary center were recruited in Arizona. For interviews, 20 Hispanic PWP, 20 caregivers, and six physicians providing service to Hispanic PWP in the community were recruited in California. Survey responses of Hispanic and non-Hispanic PWP were compared. Major survey themes were identified by applying grounded theory and open coding.

Results:

The survey found roughly half (Q1 54%, Q2 55%) of Hispanic PWP linked to a tertiary center knew about research; there was unawareness among community Hispanic PWP. Most preferred having physician recommendations for research participation and were willing to participate. Hispanics preferred teams who speak their native language and include family. Research engagement, PD knowledge, role of family, living with PD, PD care, pre-diagnosis/diagnosis emerged as themes from the interview.

Conclusion:

Barriers exist for participation of Hispanic PWP in research, primarily lack of awareness of PD research opportunities. Educating physicians of the need to encourage research participation of Hispanic PWP can address this. Physicians need to be aware of ongoing research and should not assume PWP disinterest. Including family members and providing research opportunities in their native language can increase research recruitment.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical research is essential for early detection, progression and treatment for Parkinson’s disease (PD), which affects an estimated 930,000 people in North America in 2020 [1] and is the second leading neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [2]. Participation of a diverse population in clinical trials is important to ensure that the results can be applicable to a wide range of people [3, 4]. Although Hispanics make up 17%of the US population [5], which is estimated to grow up to 30%by the year 2050 [4, 6], they are under-represented in clinical research studies [7–10]. In fact, the National Institutes of Health reports that racial and ethnic minorities make up 30%of enrollees in clinical trials and Hispanics represent only 7.6%of those participants [4]. While there is limited data on minority enrollment in PD research, it is estimated that only 8%of participants are non-white [11], suggesting Hispanic representation is even lower. While previous studies have identified obstacles for participation in research in the general Hispanic population as low awareness of opportunities, language and cultural barriers, logistical challenges, and negative perceptions of research [7, 9], the barriers for Hispanic persons with PD (PWP) have not yet been investigated.

In this study, we sought to determine Hispanic PWP: 1) awareness of general research opportunities for PD, 2) interest and motivation for participation in such studies, 3) perceived barriers or facilitators to participation, and 4) suggestions for overcoming those barriers. We also aimed to explore Hispanic persons’ access to PD care and disease knowledge. We used mixed methods to apply a survey and an interview to gain insight to patient, caregiver, and physician perspectives.

METHODS

Participants

Survey (tertiary center)

62 Hispanic PWP and 38 non-Hispanic PWP were recruited during a clinical visit at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, AZ or through the Institute’s Hispanic outreach program between July 2017 and August 2018. All non-Hispanic participants were Caucasian. Homebound Hispanic PWP living in the Phoenix metropolitan area were reached by promotores- outreach volunteers trained in PD who were responsible for community-based disease education and other related activities. Convenience sampling was used to obtain survey responses. As this was an exploratory study, no power analysis was performed.

Interview

20 Hispanic PWP over the age of 40 with a clinical PD diagnosis, 20 Hispanic caregivers spending at least three hours per day for three to four days a week with a Hispanic PWP, and six physicians managing care for Hispanic PWP on a regular basis in either San Diego or Imperial County were recruited through practices of community physicians between May 2017 and November 2017. We targeted people who identified as Hispanic or Latino regardless of their race. We collected ethnicity data and did not exclude individuals based on their identified race. Fourteen of the caregivers were spouses (13 wives, one husband) and six were children (three caring for their mother, three for their father). One physician was practicing family medicine, two were general neurologists, two were movement disorders specialists, and one was a psychiatrist. San Diego and Imperial County are highly populated by Hispanics accounting for 34%of the population in San Diego County including 80%in Chula Vista, and 85%in Imperial County [12]. Recruitment flyers were distributed via PD support groups in San Diego and Imperial County. Study information was also listed on Fox Trial Finder, an online clinical trial matching tool created by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF) to find volunteers for PD research studies.

The study was approved by the local institutional review boards. All participants were consented before the surveys or interviews and compensated with a gift card for their participation. Survey participants received a $15.00 gift card to a local gas station or grocery store and interview participants received a $40.00 Visa gift card.

Assessments

Survey

The team at Barrow (Phoenix) developed a self-report Likert-type (seven-point scale, rating 1–3 = disagree, rating 4 = neutral, rating 5–7 = agree) survey in English and Spanish to evaluate attitudes toward research among PWP. The survey was based on a literature review regarding racial and ethnic minority enrollment and attitudes toward research in multiple disease areas [11, 13, 14] (Supplementary Material 1). The Spanish translation was reviewed by eight (CM, GC, AO, LF, AB, RR) native language speakers involved in clinical care and research and deemed culturally appropriate. Caregivers were allowed to help fill out the survey if the PWP needed assistance. Surveys took approximately 15 min to complete.

Interview

Semi-structured phone interview guides were designed by the UCSD (San Diego) team to capture each interviewee’s experiences with diagnosis, care and research access, disease and research knowledge. A total of three guides were designed for each participant gr-oup (Hispanic PWP, caregivers, physicians) (Supplementary Material 2). The Spanish translation was reviewed by two native language speakers (IL, VL) involved in research and deemed culturally appropriate. Participants were verbally consented, screened, and agreed to be interviewed and audio recorded over the phone. Physicians were identified and initially contacted by the UCSD site principal investigator (IL) by email and phone. Interviews were conducted from May through November 2017 by a bilingual research coordinator and on average lasted 30 mins. All Hispanic PWP and caregivers chose to be interviewed in Spanish, but physicians were interviewed in English. Audio recordings were transcribed into Spanish and then translated into English.

Statistical analysis

Survey

Demographics were compared between Hispanic and non-Hispanic PWP using Chi-square and t tests with significance set at p < 0.05. Survey responses were compared between groups using Mann Whitney U tests for ordinal data, and Chi-square tests for categorical data (agree/neutral/disagree) with significance set at p < 0.05.

Interview

Grounded theory [15] open coding was used to identify all surveyed themes. We started with a purposive sample to address our research question, what are the perspectives of the Hispanic PD community on PD and PD research. We reviewed the data collected via interviews line by line using open coding to assign a code to describe the meaning of each phrase. The focus was then restricted to codes that surfaced repeatedly, and further grouped into themes and sub-themes. A codebook of themes, sub-themes, and definitions was created using the qualitative analysis software, QDA Miner [16]. Rigor of qualitative analysis was established by the systemic process we used to analyze data to minimize researcher bias. The reviewers did not use previous ideas about the Hispanic population but instead looked for themes that emerged from the data to draw conclusions on the research question. The coding scheme was evaluated by two reviewers (SB, VL) who independently coded a subsample of transcripts. If there was any discordance, the two coders discussed and reached a mutual decision. After the initial cross coding of the subsample, the codebook was considered final and the coding of the remainder of transcripts was completed. Coding frequency for each code was determined using the QDA Miner frequency tool. The frequencies represent the percentage of codes being repeated under each overarching theme.

Data availability statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

RESULTS

Demographics of the survey and interview participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographics of Participants

| Survey Participants (Tertiary) | Interview Participants (Community) | ||||

| Hispanic PWP (n = 63) | Non-Hispanic PWP (n = 38) | p | Hispanic PWP (n = 20) | Caregivers (n = 20)* | |

| Age | 65.3±11.1 | 71±8.1 | 0.007 | 65 (12) | 54 (11.5) |

| Disease Duration, y | 6.92±5.6 | 8.54±6.0 | 0.189 | 15.9 (35.0) | |

| Sex, female | 19 (31%) | 23 (59%) | 0.004 | 8 (40%) | 13 (81%) |

| Education Level | < 0.001 | ||||

| Elementary School | 11 (17.5) | 0 | 2 (10) | 2 (33) | |

| Middle School | 3 (15) | 1 (6) | |||

| High School | 22 (34.9) | 7 (17.9) | 4 (20) | 4 (25) | |

| College/Trade School | 12 (19.0) | 13 (33.3) | 7 (35) | 5 (31) | |

| Graduate School | 2 (30.2) | 17 (43.6) | 1 (5) | 3 (19) | |

| Unreported | 12(19.0) | 2 (5.13) | 3 (15) | ||

| Native Language | < 0.001 | ||||

| English | 0 | 39 (100) | 5 (25) | 4 (25) | |

| Spanish | 61 (96.8) | 0 | 15 (75) | 12 (75) | |

| English and Spanish | 1 (1.59) | 0 | |||

| Other | 1 (1.59) | 0 | |||

| Country of Origin | |||||

| USA | Not available | Not available | 13 (65) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Mexico | Not available | Not available | 6 (30) | 9 (56) | |

| Other | Not available | Not available | 1 (5) | 0 | |

Variables are reported as mean±SD or number (%) where applicable. PWP: Persons with Parkinson’s disease. *Demographic data was not collected from 4 caregivers.

Survey

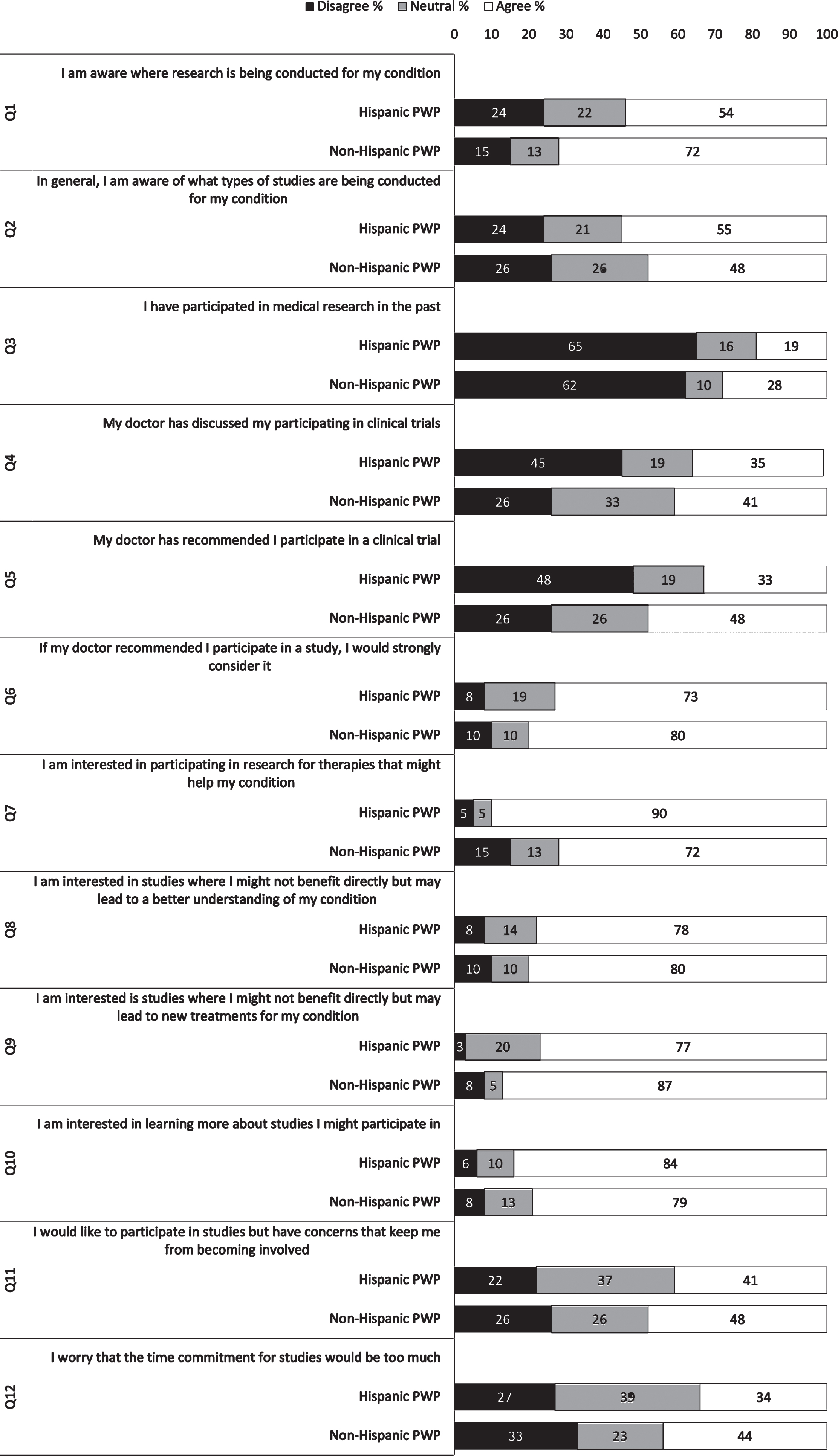

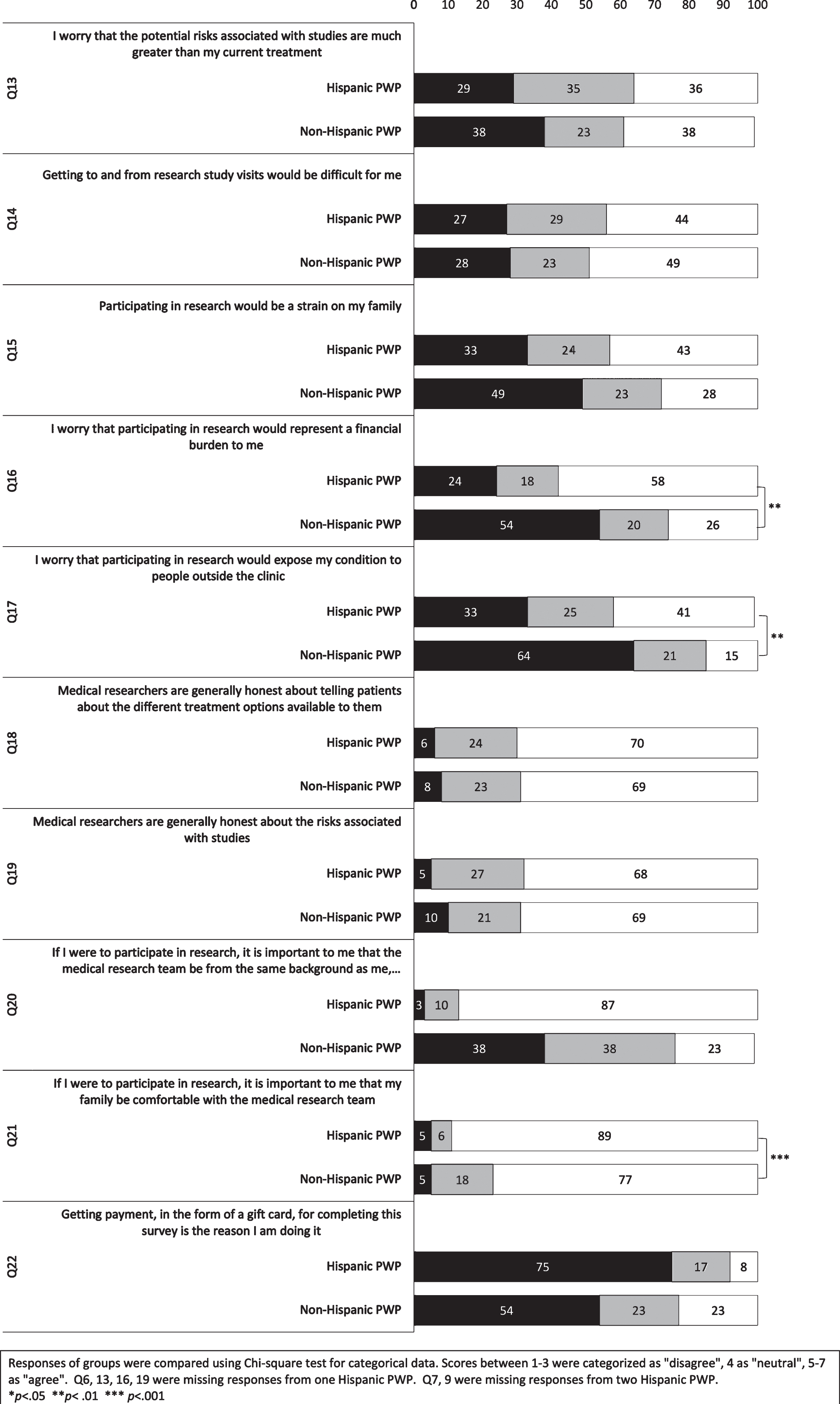

Hispanic PWP were younger and less educated than non-Hispanic PWP, without a significant difference for disease duration. Group responses to each question on the survey are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2. In general, Hispanic PWP and non-Hispanic PWP responded similarly, with over half agreeing that they were aware of the research studies and were interested in observational and drug studies which may benefit themselves and future generations, although very few had previously participated in a study. They believed that the researchers were generally honest about available treatment options and study risks, and physician recommendation for participation in a study was a strong factor for PWP to consider participation. However, responses by Hispanic PWP and non- Hispanic PWP differed significantly for several questions (Fig. 2). Hispanic PWP were more interested in participating in drug trials (U = 852, p = 0.004), but they were more concerned that research participation would represent a financial burden (U = 719.5, p < 0.001) and expose their condition (U = 803.0, p = 0.003). Hispanic PWP indicated the importance of the research team being from the same background, speaking their native language (U = 300, p < 0.001) and their family being comfortable with the research team much more strongly (U = 864, p = 0.005). Hispanic PWP tended to be less likely to have done the survey for the $15 gift card (U = 916.5 p = 0.002).

Fig. 1

Survey responses of Hispanic and non-Hispanic PWP compared using categorical data.

Fig. 2

Survey responses of Hispanic and non-Hispanic PWP compared using ordinal data.

Interview (community)

Six major themes emerged during the interviews: Research Engagement, Pre-diagnosis/Diagnosis, PD Care, Living with PD, Role of Family/Caregiver, and PD Knowledge (See Table 2 for further explanation of interview results.)

Table 2

Interview Codebook and Results

| Theme | Definition | Sub-themes | Findings | Hispanic PWP | Caregivers |

| Research Engagement | Dives deeper into the specific barriers and facilitators to research participation | •Aware/unaware of PD research opportunities | •Acknowledgement of the importance of research for finding a cure and providing PD related information to the community | 95% | 95% |

| •Research knowledge | •Motivation for research participation based on the benefit towards the greater community and future generations | 80% | 95% | ||

| •Research participation | •Previous participation in research due to a comorbidity | 10% | n/a | ||

| •Value of research | |||||

| •Attitudes toward research participation | |||||

| •Asked/not asked to participate in research | |||||

| Pre-diagnosis/Diagnosis | Explores the initial physical and emotional journey that a participant undergoes when recognizing PD symptoms and seeking a diagnosis | •Diagnostic accuracy | •Medical intervention sought due to advanced symptoms affecting daily life | 50% | 10% |

| •Diagnostic process | •Visits to at least two physicians during the diagnostic process | 80% | 40% | ||

| •Comorbidity | •Feeling depressed after the diagnosis | 55% | 65% | ||

| •Emotions at PD diagnosis | |||||

| •Referral | |||||

| Role of Family/ Caregiver | Provides insight into caregivers are gatekeepers of information and play a large role in decisions about care and treatment, including research participation | •Information seeking | •Hispanic PWP relied of family members as a source of support | 50% | n/a |

| •Family support | •Caregiver involvement of their loved one’s learning process regarding PD | n/a | 95% | ||

| •Desire for practical information for coping with and managing PD associated behaviors | 45% | 95% | |||

| PD Knowledge | Highlights various resources that individuals use to learn more about PD, different information-seeking behaviors and barriers that individuals experience when trying to learn more about research | •Knowledge level | •Lack of knowledge regarding the disease | 70% | 50% |

| •Information channels | •Sought information outside of physician-provided materials | n/a | 95% | ||

| •Information available | •Sought external information for improving quality of life with PD | 65% | n/a | ||

| •Information sought/not sought | •Sought external information regarding the progression of the disease, daily life improvements, and future expectations | n/a | 80% | ||

| •Spanish-language resources | |||||

| •Aware/unaware of PD resources | |||||

| •Limited access/resources | |||||

| •Language barrier | |||||

| PD Care | Looks at the second leg of the participant journey with PD, specifically the learning curve with medications (adherence and optimization) | •Medication optimization | •Limitations and challenges acquiring PD related information | 35% | 45% |

| •Treatment options | •Felt diet and exercise useful for managing PD | 35% | n/a | ||

| Living with PD | Examines changes that have occurred in individuals’ lives after a PD diagnosis and how they talk about living with PD | •Vernacular | •Overall decline of internal functions and progression of PD symptoms | 55% | 45% |

| •Change to quality of life | •Toll of PD diagnosis on the entire family | 35% | 30% | ||

| •Maintain quality of life | |||||

| •Emotions toward PD symptoms |

PD, Parkinson’s disease; PWP, Person(s) with Parkinson’s disease; n/a, not applicable.

Interview (physicians)

All physicians reported that Hispanic PWP have limited knowledge of PD and research. Only two physicians reported Hispanic PWP asking for information on resources including research. Four physicians had informed Hispanic PWP about participation in research. Physicians believe that barriers prevent Hispanic PWP from research participation, including transportation (n = 5), language (n = 4), financial (n = 2), and limited knowledge (n = 2).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to determine Hispanic PWP awareness of research opportunities, interest and motivation for participation in such studies, barriers to research participation, potential ways to overcome barriers and PD knowledge. We compared Hispanic PWP and non-Hispanic PWP perspectives using a survey and gathered further data on PWP, caregiver and physician perspectives through in-depth qualitative phone interviews. Interviews also evaluated knowledge of PD, opinions on PD care, living with PD and the role of family and caregivers.

Overall, PWP linked to a tertiary center were aware of ongoing research studies, trusted researchers, and were interested in research, although only a few had previously participated in research. In contrast, Hispanic PWP and caregivers not linked to a tertiary center were unaware of research studies, although they strongly endorsed the value of research and wanted to participate for the benefit of themselves and future generations. Strong motivation of Hispanic PWP to help future generations is similar to the study by Jefferson and colleagues [17] showing older adults participating in AD research are motivated for personal and society’s benefit. Hispanic PWP were interested in research as much as non-Hispanic PWP and were willing to participate in research.

The survey revealed potential barriers for research participation for the Hispanic PWP including potential financial burden and exposure of their condition. The interviews revealed that the primary barrier for those not linked to a tertiary center was unawareness of research opportunities. The most important barrier for Hispanic PWP and caregivers as well as for other ethnic minorities not linked to a tertiary center may be lack of awareness about research opportunities despite being very interested in research [18, 19]. Considering the majority of Hispanic and non-Hispanic PWP agreed that they would be willing to participate if their physician had recommended participation in a study, physicians not informing and providing the importance for PWP and their caregivers about research participation may be among the main reasons for Hispanic underrepresentation in PD research. These results stress the importance of physicians who care for Hispanic PWP outside of tertiary centers staying informed about ongoing res-earch in their area. Community-based physicians also reported in the interviews that they did not regularly discuss research participation with PWP and were rarely asked about research by the Hispanic PWP. Nevertheless, even for Hispanic PWP linked to a tertiary center of care, almost half of the PWP stated that their physician did not discuss or recommend participation in a trial. This may be due to physicians selectively referring non-Hispanic PWP over Hispanic PWP. Physicians may not be presenting the opportunity for research participation with Hispanic PWP due to their own assumptions that Hispanic PWP would have transportation difficulty and/or lack of interest [20, 21]. These potential barriers were brought up by the interviewed physicians and the Hispanic PWP linked to a tertiary center in our study. Nevertheless, these barriers were not brought up by Hispanic PWP not linked to a tertiary center. The discrepancy can perhaps be due to these individuals having limited knowledge of what research participation entails, which can be assessed in future studies. Additionally, Hispanics have less exposure to research opportunities given they are less apt to access sites, diagnostic centers and support groups, where research recruitment is more likely to happen [22].

Another important barrier for research participa-tion was found to be language. Hispanic PWP preferred the research team spoke their same language and their families were comfortable with the team, which likely reflects a better understanding of the Hispanic culture. Alongside language barriers, lack of healthcare coverage, family responsibilities, legal status, work schedules, and cultural differences were also previously reported as potential barriers for research participation in other diseases [23–26]. Previous studies have suggested that Hispanics are con-cerned with unethical research practices or potential harm [7], and that both Hispanics and African Americans have mistrust of the medical system [27, 28]. However, our results showed that trust in re-searchers is high in the Hispanic PWP population, and although Hispanic PWP may have reported concerns about financial barriers, non-Hispanic PWP also reported barriers such as transportation. Thus, financial barriers do not only apply to Hispanic PWP and this barrier should not be specifically assumed to exist only for Hispanics.

Our findings suggest that addressing potential fin-ancial burden, minimizing risk of condition disclosure, having study team members who can speak the native language of participants, and ensuring that families are comfortable can increase research participation among Hispanic PWP linked to a tertiary center who are already generally aware of ongoing PD research. As communicating in English can be a barrier to research participation, and Hispanic PWP prefer researchers from the same cultural background [10, 23], research teams should be expanded to include community-based volunteers of a similar background such as the promotores [6] who assisted in completion of surveys for this study. It is also equally important having translated versions of written research materials available in native languages and available to recruitment sources. Since PWP are interested and willing to participate once their physician recommends a study, it seems important for physicians to discuss research participation during clinic visits.

Regarding clinical care, majority of the Hispanic PWP had gone to multiple physicians for diagnosis. The majority of Hispanic PWP were evaluated by at least two physicians during the diagnostic process, most commonly due to a referral from primary care to a specialist followed by seeking better care and finding a trusted provider. Although the experience of non-Hispanic PWP is not well documented, a population-based study estimated that 20%of people with PD, who had already sought medical care, had not yet been diagnosed with PD [29]. Thus, it is not surprising that the Hispanic PWP had visited multiple physicians. The majority of the Hispanic PWP and half of the caregivers did not know much about the disease and sought information outside their physician to learn more. Almost all caregivers were very involved with learning about the disease and seeking information outside their physician. Physicians believed Hispanic PWP presented in clinic once symptoms are more advanced, which is related to early symptoms being underreported compared to non-Hispanic PWP. 50%of Hispanic PWP and 10%of caregivers interviewed in this study acknowledged that advanced symptoms interfering with daily activities propelled them to seek medical intervention. This may also be due to misinterpreting signs of disease as part of aging [22] or the culturally taboo topic of seeking help for mental health and cognition [22, 30].

Hispanic PWP rely on physicians for disease knowledge, which stresses the importance of physicians providing disease education and referrals to research. However, physicians should keep in mind that Hispanics tend to be less educated than other ethnic groups, with about half completing high school and fewer going on to further education [31, 32]. As healthy literacy is low across all ethnicities, with 1 in 4 having low healthy literacy and almost 50%low or marginal health literacy [33], Hispanics with lower education may be less likely to fully comprehend complicated medical jargon [22]. This is reflected in the education level of our two groups, with 30%of graduate level of education in those attending a tertiary center versus 5%among Hispanic PWP in the community. Therefore, community physicians and outreach workers working with the Hispanic community can improve disease knowledge and health literacy by providing education while being mindful of their varying knowledge levels.

More than half of Hispanic PWP and caregivers re-ported feeling depressed upon learning the diagnosis. Given that being newly diagnosed with a chronic illness is distressing for all ethnic groups [34], educ-ation, supportive services such as home visits, supportive groups, respite services, and research opp-ortunities in PWP’s and caregivers’ native language can also decrease the depressed and dispirited feelings. Inclusion of family members in the process is crucial as the impact, economic, and personal cost of PD is universal on families regardless of culture [35]. Surprisingly, only one-third of Hispanic PWP and caregivers, and one physician in our study mentioned the toll of a PD diagnosis on the whole family. However, our interviews also showed that spouses and children were consistently part of the diagnostic and information gathering processes as well as clinical care and were challenged with seeing the disease progression and not knowing the best way to support their loved one. Based on our findings and previous studies in Hispanics with dementia [36, 37], the importance of providing disease education and resources to support family members should not be overlooked.

Our study has several limitations. The sample size of interviewed physicians was low; however, both English and Spanish speaking physicians with a range of specializations were included and found to have similar perspectives. We collected ethnicity but were not able to collect uniform data on race. An open-ended question was used for race while a multiple choice format may have been more useful. The survey only focused on research, and the interview script also included diagnostic process and disease knowledge. For the purposes of this exploratory study, we kept our conversation limited to research in general. We did not address the specifics of different types of research trials nor the commitment required from the participant, although these specifics can have a further impact on participants’ perspectives. Future studies including both surveys and qualitative interviews focusing extensively on clinical care as well as research in PD can provide more insight to methods of overcoming Hispanic underrepresentation in PD research.

On the other hand, an important aspect of our study is that this is the first study to include both Hispanic PWP and non-Hispanic PWP using a survey, and an in-depth qualitative interview of Hispanic PWP, caregivers and physicians who usually manage Hispanic PWP. By recruiting participants from two different geographic locations, Arizona and California, we were able to investigate the experience of groups with different levels of access to healthcare and research opportunities. Although we found similarities between participant groups from different locations, the relatively small samples prevent generalization to all Hispanics or all non-Hispanic groups. However, we believe these preliminary results will pave the way for future research and recruitment efforts.

In conclusion, our results show that Hispanic PWP are interested in participating in research, believe that research is valuable, and are motivated to help future generations and themselves. The primary barrier for Hispanic PWP’s research participation stems from limited physician knowledge of ongoing research studies in their communities, discussion of ongoing studies in their communities, and invitation to participate. These barriers could be addressed in part by education of physicians, PWP, and caregivers, which is achievable with the help of non-profit organizations, academic institutions, and government agencies adjusting their current outreach and research recruitment strategies to focus on educating community physicians as gatekeepers to minority research participation. Overall, access to appropriate clinical care is the gateway to improve disease education, management, and research participation in PD.

While our research only included PD, we believe that our results are applicable to other diseases. We are hoping that these findings will serve to increase awareness on how to include minorities in research. Particularly within the AD research community addressing diversity has become an important focus over the last few years [38] and more recently amidst the current COVID-19 pandemic. Mainstream media has showcased ethnic health disparities demonstrated by the disproportionate infection rates among minorities, particularly among Hispanics. In California, Hispanics account for 61%of COVID-19 cases and almost half (48%) of deaths [39]. Improving access to care and providing educational resources to prevent disinformation are crucial to improve the wellbeing of minorities that are unequally affected by many other diseases including the new infections we are struggling to keep under control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our participants for their involvement in this project. We thank Angie Sanchez for reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript, Michelle Whitman for publication coordination, and the promotores for their help distributing the surveys. We also thank Claudia Martinez, Alejandra Borunda, and Ruby Rendon for reviewing the Spanish translation of the survey. This project was funded by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/21-0231r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210231.

REFERENCES

[1] | Marras C , Beck JC , Bower JH , Roberts E , Ritz B , Ross GW , Abbott RD , Savica R , Van Den Eeden SK , Willis AW , Tanner C ((2018) ) Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 4: , 21. |

[2] | Nussbaum RL , Ellis CE ((2003) ) Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 348: , 1356–1364. |

[3] | Dahodwala N , Siderowf A , Xie M , Noll E , Stern M , Mandell DS ((2009) ) Racial differences in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24: , 1200–1205. |

[4] | Wallington SF , Luta G , Noone AM , Caicedo L , Lopez-Class M , Sheppard V , Spencer C , Mandelblatt J ((2012) ) Assessing the awareness of and willingness to participate in cancer clinical trials among immigrant Latinos. J Community Health 37: , 335–343. |

[5] | Ennis SR , Rios-Vargas M , Albert NG (2011) The Hispanic Population: 2010 Census Briefs. U.S. Census Bureau, Suitland, MD. |

[6] | Ceballos RM , Knerr S , Scott MA , Hohl SD , Malen RC , Vilchis H , Thompson B ((2014) ) Latino beliefs about biomedical research participation: A qualitative study on the U.S.-Mexico border. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 9: , 10–21. |

[7] | Arevalo M , Heredia NI , Krasny S , Rangel ML , Gatus LA , McNeill LH , Fernandez ME ((2016) ) Mexican-American perspectives on participation in clinical trials: A qualitative study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 4: , 52–57. |

[8] | Calderón JL , Baker RS , Fabrega H , Conde JG , Hays RD , Fleming E , Norris K ((2006) ) An ethno-medical perspective on research participation: A qualitative pilot study. MedGenMed 8: , 23. |

[9] | Evans KR , Lewis MJ , Hudson S V ((2012) ) The role of health literacy on African American and Hispanic/Latino perspectives on cancer clinical trials. J Cancer Educ 27: , 299–305. |

[10] | Ford ME , Siminoff LA , Pickelsimer E , Mainous AG , Smith DW , Diaz VA , Soderstrom LH , Jefferson MS , Tilley BC ((2013) ) Unequal burden of disease, unequal participation in clinical trials: Solutions from African American and Latino community members. Health Soc Work 38: , 29–38. |

[11] | Schneider MG , Swearingen CJ , Shulman LM , Ye J , Baumgarten M , Tilley BC ((2009) ) Minority enrollment in Parkinson’s disease clinical trials. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15: , 258–262. |

[12] | US Census Bureau: Quick Facts San Diego County, California; Imperial County, California, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/imperialcountycalifornia,sandiegocountycalifornia/BZA010218. |

[13] | Tilley BC , Mainous AG , Elm JJ , Pickelsimer E , Soderstrom LH , Ford ME , Diaz VA , Siminoff LA , Burau K , Smith DW ((2012) ) A randomized recruitment intervention trial in Parkinson’s disease to increase participant diversity: Early stopping for lack of efficacy. Clin Trials 9: , 188–197. |

[14] | Mainous AG , Smith DW , Geesey ME , Tilley BC ((2006) ) Development of a measure to assess patient trust in medical researchers. Ann Fam Med 4: , 247–252. |

[15] | Scott JC , Glaser BG ((1971) ) The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Am Sociol Rev 36: , 335. |

[16] | Provalis research, QDA MINER LITE - Free qualitative data analysis software, https://provalisresearch.com/products/qualitative-data-analysis-software/freeware/. |

[17] | Jefferson AL , Lambe S , Chaisson C , Palmisano J , Horvath KJ , Karlawish J ((2011) ) Clinical research participation among aging adults enrolled in an Alzheimer’s disease center research registry. J Alzheimers Dis 23: , 443–452. |

[18] | Branson CO , Ferree A , Hohler AD , Saint-Hilaire M-H ((2016) ) Racial disparities in Parkinson disease: A systematic review of the literature. Adv Parkinsons Dis 05: , 87–96. |

[19] | Branson C , Bissonette S , Johnson T , Weinberg J , Saint-Hilaire M ((2018) ) Recruitment of minority populations with Parkinson’s disease at an urban hospital. Mov Disord 33: , S400. |

[20] | Guillemin M , McDougall R , Martin D , Hallowell N , Brookes A , Gillam L ((2017) ) Primary care physicians’ views about gatekeeping in clinical research recruitment: A qualitative study. AJOB Empir Bioeth 8: , 99–105. |

[21] | Nuytemans K , Manrique CP , Uhlenberg A , Scott WK , Cuccaro ML , Luca C , Singer C , Vance JM ((2019) ) Motivations for participation in Parkinson disease genetic research among Hispanics versus non-Hispanics. Front Genet 10: , 658. |

[22] | Gallagher-Thompson D , Solano N , Coon D , Areán P ((2003) ) Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: Issues to face, lessons to learn. Gerontologist 43: , 45–51. |

[23] | Hildebrand JA , Billimek J , Olshansky EF , Sorkin DH , Lee JA , Evangelista LS ((2018) ) Facilitators and barriers to research participation: Perspectives of Latinos with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 17: , 737–741. |

[24] | Ibrahim S , Sidani S ((2014) ) Strategies to recruit minority persons: A systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health 16: , 882–888. |

[25] | Cutts T , Langdon S , Meza FR , Hochwalt B , Pichardo-Geisinger R , Sowell B , Chapman J , Dorton LB , Kennett B , Jones MT ((2016) ) Community health asset mapping partnership engages Hispanic/Latino health seekers and providers. N C Med J 77: , 160–167. |

[26] | Bonevski B , Randell M , Paul C , Chapman K , Twyman L , Bryant J , Brozek I , Hughes C ((2014) ) Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 14: , 42. |

[27] | Ulrich A , Thompson B , Livaudais JC , Espinoza N , Cordova A , Coronado GD ((2013) ) Issues in biomedical research: What do Hispanics think? Am J Health Behav 37: , 80–85. |

[28] | Katz RV , Kegeles SS , Kressin NR , Green BL , Min QW , James SA , Russell SL , Claudio C ((2006) ) The Tuskegee Legacy Project: Willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved 17: , 698–715. |

[29] | Schrag A , Ben-Shlomo Y , Quinn N ((2002) ) How valid is the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in the community? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 73: , 529–534. |

[30] | Aranda MP ((2001) ) Racial and ethnic factors in dementia care-giving research in the US. Aging Ment Health 5: , 116–123. |

[31] | O’Brien EM ((1993) ) Latinos in higher education. Res Briefs 4: , 1–15. |

[32] | Office of the Surgeon General (US); Center for Mental Health Services (US); National Institute of Mental Health (US) (2001) Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General, Rockville, MD. |

[33] | Fitzsimmons PR , Michael BD , Hulley JL , Scott GO ((2010) ) A readability assessment of online Parkinson’s disease information. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 40: , 292–296. |

[34] | Kutner JS , Steiner JF , Corbett KK , Jahnigen DW , Barton PL ((1999) ) Information needs in terminal illness. Soc Sci Med 48: , 1341–1352. |

[35] | Whetten-Goldstein K , Sloan F , Kulas E , Cutson T , Schenkman M ((1997) ) The burden of Parkinson’s disease on society, family, and the individual. J Am Geriatr Soc 45: , 844–849. |

[36] | Maldonado D ((1985) ) The Hispanic elderly: A sociohistorical framework for public policy. J Appl Gerontol 4: , 18–27. |

[37] | Valle R ((2014) ) Care giving across cultures: Working with dementing illness and ethnically diverse populations, Routledge, Washington, DC. |

[38] | The National Institute on Aging (2020) Report of 2019-2020 Scientific Advances for the Prevention, Treatment, and Care of Dementia: The Urgent Need for Increased and Diverse Participation in Studies, Bethesda, MD. |

[39] | California Department of Public Health (2021) COVID-19 Race and Ethnicity Data, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/Race-Ethnicity.aspx, Last updated on 10 March 2021, Accessed on 17 March 2021. |