Rationale, Design, and Methodology of a Prospective Cohort Study for Coping with Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia: The RECage Project1

Abstract

Background:

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) are quite challenging problems during the dementia course. Special Care Units for people with dementia (PwD) and BPSD (SCU-B) are residential medical structures, where BPSD patients are temporarily admitted, in case of unmanageable behavioral disturbances at home.

Objective:

RECage (REspectful Caring for AGitated Elderly) aspires to assess the short and long-term effectiveness of SCU-Bs toward alleviating BPSD and improving the quality of life (QoL) of PwD and their caregivers.

Methods:

RECage is a three-year, prospective study enrolling 500 PwD. Particularly, 250 community-dwelling PwDs presenting with severe BPSD will be recruited by five clinical centers across Europe, endowed with a SCU-B, for a short period of time; a second similar group of 250 PwD will be followed by six other no-SCU-B centers solely via outpatient visits. RECage’s endpoints include short and long-term SCU-B clinical efficacy, QoL of patients and caregivers, cost-effectiveness of the SCU-B, psychotropic drug consumption, caregivers’ attitude toward dementia, and time to nursing home placement.

Results:

PwD admitted in SCU-Bs are expected to have diminished rates of BPSD and better QoL and their caregivers are also expected to have better QoL and improved attitude towards dementia, compared to those followed in no-SCU-Bs. Also, the cost of care and the psychotropic drug consumption are expected to be lower. Finally, PwD followed in no-SCU-Bs are expected to have earlier admission to nursing homes.

Conclusion:

The cohort study results will refine the SCU-B model, issuing recommendations for implementation of SCU-Bs in the countries where they are scarce or non-existent.

INTRODUCTION

The percentage of people with neurodegenerative diseases is rapidly rising; since 2018, about 50 million people were living with dementia worldwide, while this number is expected to triple by 2050 [1]. The care of people with dementia (PwD) is a great burden for caregivers and societies, and the cost of dementia worldwide is also increasing [2]. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) is the term used in order not to describe a disease-specific clinical syndrome, but a combination of heterogeneous psychiatric symptoms [3]. Therefore, BPSD comprises a great spectrum of symptoms ranging from mood disorders such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders, and psychiatric symptoms such as agitation, psychosis, apathy, aberrant motor activity, hallucinations, and delusions [4].

BPSD are some of the most challenging problems arising during the course of dementia, causing severe stress in PwD and their families. They often lead to patient’s institutionalization [5] and incur large costs to the public health system [6, 7], since they affect almost 90%of PwD of any stages [8]. The prevalence of BPSD among neurocognitive diseases depends on the etiology of the cognitive disorder [9], and the reported numbers of the BPSD differ among studies and countries. This is because the prevalence of BPSD is associated with the type of the study’s sample or the facilities from where they were recruited, e.g., community-dwelling PwD versus people from hospitals, nursing homes, etc. [10].

However, according to the meta-analysis by Zhao et al. (2016), the sub-syndromes of hyperactivity, psychosis, affective disorders, and apathy frequently occur in the course of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), although with heterogeneity in their range. Generally, the most frequent symptoms among the neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD seem to be apathy with a prevalence of 49%, depression at 42%, and aggression with a prevalence of 40%[11]. The prevalence of anxiety and sleep disorders is 39%, while irritability and appetite disorders affect 36%and 34%of the patients, respectively [11]. Psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucination have a prevalence of 31%and 16%, respectively, while the prevalence of aberrant motor behavior is 32%. Among the less common symptoms occurring in AD include disinhibition (17%) and euphoria (7%) [11].

As far as the neurocognitive diseases of other etiology are concerned, BPSD is also reported in frontotemporal dementia (FTD), especially in the behavioral type (bvFTD) [12]. The most frequent symptoms in bvFTD seem to be apathy, irritability, disinhibition, wandering, social inappropriateness, and agitation/aggression [12, 13], while depression is also a common symptom, even if in lower percentages [14]. Behavioral symptoms in FTD seem to cause greater burden for FTD caregivers in comparison to AD caregivers [15]. Similarly, as far as vascular dementia is concerned, that is the second most frequent type of dementia [16], sleep disturbances and depression seem to be the most common symptoms with percentages of 63%and 59%, respectively, while apathy (56%), eating disorders (54%), and anxiety (49%) follow. Irritability (38%), aggression (33%), and aberrant motor activity (17%) are not so frequent, while delusions (11%), hallucinations (9%), and euphoria (1%) are present in lower percentages [17]. Finally, BPSD are also frequent in Lewy body dementia and sometimes very difficult to manage [18].

Furthermore, BPSD are more prominent in younger patients and are associated with loss of functioning [19]. They cause significant caregiver distress [20], often leading to institutionalization [5], and increase the costs of dementia care [6].

In order to reduce psychological caregiver’s distress and to avoid patient’s institutionalization, pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies are applied to treat BPSD [10]. Regarding pharmacological treatment, among the most frequently prescribed drugs for up to 60%of PwD for BPSD are antipsychotics (atypical or not) [21], while other medication includes psychotropic drugs, e.g., anxiolytics and anti-depressants [22]. However, pharmacological treatment with typical and atypical antipsychotics for BPSD in older adults should be used with caution, since they can cause adverse side effects [23] and deterioration of cognitive function [24–26], as well as cerebrovascular events such as stroke [27].

On the other hand, non-pharmacological therapy has to be in the first line of the treatment of BPSD [28] in order to avoid adverse events associated with antipsychotic drugs. Non-pharmacological therapy comprises a variety of interventions for BPSD management, such as aromatherapy [29], music therapy [30], massage [31], doll therapy [32], pet-assisted interventions [33], bright light treatment [34], Snoezelen rooms [35], and cognitive-behavior therapy [36], as well as interventions with caregivers such as caregiver’s education [37]. Moreover, over the last few years, a combination of non-pharmacological interventions (among the aforementioned) are utilized and seems to become more popular since it has a good effectiveness in BPSD management [38, 39]. However, besides the fact that there are many studies on the non-pharmacological interventions for BPSD in dementia patients, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding their real effectiveness on patient’s behaviors, due to methodological problems and small sample sizes.

The special medical care unit for PwD and BPSD (SCU-B)

SCU-B is a novel term that refers to “a residential medical structure lying outside of a nursing home, in a general hospital or elsewhere, e.g., in a private hospital or a geriatric or psychiatric hospital, where patients with BPSD are temporarily admitted when their behavioral disturbances are not amenable to control at home”. These special centers differ from the general day care centers for dementia or other special care units existing in other facilities such as nursing homes, since they are 1) medical institutions and 2) focused on the needs of PwD and severe BPSD and aim to mitigate the challenging symptoms and allowing patients to get back home. Furthermore, SCU-Bs adopt a philosophy which differs from the long-term or even permanent institutionalization. SCU-Bs emphasize respect of dignity of PwD and their ultimate goal, as already said, is to permit patients to get back home after the improvement of their BPSD.

Even though there is no organizational uniformity among the existing units among European countries, a common model of the SCU-B therapeutic approach comprises a combination of cautious drug therapy, plus non-pharmacological interventions, such as occupational therapy, physiotherapy, doll therapy, sensory rooms, etc. A variety of specialists in dem-entia care, such as neurologists, geriatrics and gerontologists, old age psychiatrists, doctors, and nurses, provide care in appropriate and friendly environments for PwD, such as rooms with safety devices and space for walking; moreover, in some SCU-Bs the therapeutic approach is in line with the Gentle care [40, 41], and/or the Person-Centered Dementia Care model [42, 43].

In any case, medical treatment in SCU-Bs follows the current guidelines for the management of BPSD [13, 44–46]. Evidence from clinical trials of both non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments, and from neurobiological studies, provides a range of management options that can be tailored to individual needs. It is suggested that non-pharmacological interventions (including psychosocial/psychological counseling, interpersonal management, and environmental management) should be attempted first, followed by the least harmful medication for the shortest time possible. Pharmacological treatment options, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, cholinesterase inhibitors, and memantine, need careful consideration of the benefits and limitations of each drug class [47].

As far as the effectiveness of these units is concerned, even though that there is a lack of studies regarding the short term SCU-Bs efficacy, especially because of the heterogeneity of these facilities am-ong European countries, there is some evidence that a short stay in SCU-Bs can improve BPSD [48–51].

With regard to the long term efficacy of SCU-Bs, the results are less clear since the efficacy of SCU-Bs in delaying institutionalization has not be studied so far. The institutionalization of patients with BPSD is a multi-dimensional issue since BPSD is only one of the potential reasons for patient’s institutionalization. Specifically, there are many factors that lead to institutionalization apart from the behavioral problems, e.g., the absence or even the unavailability of a caregiver, and the patient’s cognitive deterioration. Usually, the institutionalization is a permanent solution for PwD, since it is difficult for caregivers to cope with the great burden of care. However, the SCU-B’s greatest challenge is the patient’s admission to these facilities and their stay until the behavioral difficulties are controlled. Besides the fact that the ultimate goal of the SCU-Bs is the return of the patients to home when the crisis ends, the maintenance at home without regression is also important and, therefore, the longitudinal effect of interventions in SCU-Bs should be evaluated.

Study objectives and hypotheses

Since SCU-Bs are not currently implemented in all European countries, and—where they exist—are not widespread, thus no clear evidence of their long-term efficacy exists, the primary objective of the RECage project (REspectful Caring for AGitated Elderly), is to evaluate the clinical efficacy, both short and long-term, of the SCU-Bs, while the secondary objectives aspire: a) to assess the QoL of the patients and their caregivers; b) to estimate the cost-effectiveness of SCU-Bs; c) to estimate psychotropic drug consumption over time; and d) to assess the change of attitude of caregivers toward dementia.

Finally, a tertiary objective is to assess the capacity of SCU-Bs to delay institutionalization.

The main hypothesis is that the care pathways of patients with BPSDs including a SCU-B (available for admission in case of behavioral crisis, but not mandatory) are superior to the pathways lacking this facility. The side hypotheses that derive from our main hypothesis follow:

Hypothesis 1: BPSDs (measured through specific tools) will be mitigated via the SCU-B pathway compared to the no-SCUB one.

Hypothesis 2: The QoL, both for patients and their caregivers, who are cared by centers endowed with a SCU-B will be improved compared to the QoL of the patients followed by centers lacking a SCU-B.

Hypothesis 3: The attitude of caregivers toward dementia will be possibly improved, due to the psychoeducation they will have in SCU-Bs.

Hypothesis 4: SCU-Bs will be a cost-effective solution for both people with BPSD and their caregivers. People who will be admitted to SCU-B will present diminished costs compared to the patients who will not be admitted in SCU-B.

Hypothesis 5: People with BPSDs followed by SCU-B centers will have lesser psychotropic drug consumption.

Hypothesis 6: people with BPSDs followed by no SCU-B centers will be prone to earlier admission to institutions than people cared for by SCU-B centers.

METHODS

Study design

RECage is a three-year prospective observational study, comparing two groups of community-dwelling patients with a diagnosis of mild to severe dementia of any etiology and significant BPSD (e.g., hallucinations and aggressiveness as well as all the symptoms described in the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) with a total score above 32 points): the one followed up by centers with SCU-B and the other by centers lacking these facilities. Besides the fact that behavioral and psychological problems usually appear in moderate and severe stages of AD, there are also other types of dementia which appear similar problems, early enough in their course, such as the Lewy body disease and FTD. These difficulties are also a great burden for the caregivers, who usually are seeking for a solution to pharmaceutical treatment with antipsychotics, or to the patient’s admission to psychiatric clinics or special centers, if any. Therefore, since BPSD appear in all stages of dementia, it was chosen to include PwD at any stage, from mild to severe in the RECage study.

The design of the study comprises recruitment and follow-up of 500 PwD with BPSD for a duration of 36 months. This follow-up duration was mainly chosen due to our target of evaluating any differences between the institutionalization times among the groups. The duration of at least three years, is necessary to capture this long-term process. Visits will be performed every 6 months, as this is the usual practice in memory clinics.

The study sample will be divided in two groups. Eleven clinical centers from six European countries (Italy, Germany, France, Greece, Switzerland, Norway) are participating in the RECage project, five of them endowed with a SCU-B, the six others lacking this facility. PwD enrolled in a center with SCU-Bs do not have to be routinely admitted to this residential facility, but only if ordered by the treating physician during a phase of behavioral disorders not to be treated on outpatient basis. Actually, the philosophy of SCU-Bs is to temporarily accept PwD with the aim to enable them, if possible, to come back to their community. The other six centers without SCU-Bs act as a control group and will recruit and follow-up a second group of PwD with BPSD. The follow-up visits are scheduled as follows: a) at baseline, b) at 6 months, c) at 12 months, d) at 18 months, e) at 24 months, f) at 30 months, and g) at 36 months. However, the patient can request additional visits between the aforementioned, if needed.

The choice of an observational study of two parallel groups was done mainly for ethical reasons: ideally, a study restricted to centers with SCU-Bs (randomizing the patients to admission or not to the unit during a behavioral crisis) would have given better results as for the efficacy of the SCU-B, but is deemed to be unethical, since it would have deprived them of (possibly useful) treatment. Therefore, the comparison will be between two different groups (centers with/without SCU-Bs). The patients will be taken in charge by the participating centers according to their usual procedures. No alteration of the routine of the centers is requested and no additional therapy recommended. The total duration of the follow-up will be 3 years.

Participants/patients

In total, 500 PwD will be enrolled from 11 clinical centers from 6 different European countries. Two hundred and fifty people (n = 250) with dementia of any etiology as primary diagnosis will be enrolled from the centers (5) that include a SCU-B and 250 from the other (6) clinical centers. This specific diagnosis was chosen because BPSDs usually appear at all stages of dementia from mild to severe, and also in almost all dementias despite the reason. As far as the statistical balance of the study is concerned, the two groups will have no significant discrepancies between demographic features. Therefore, baseline characteristics will be comparable in terms of age, educational level, and primary caregiver’s characteristics. The countries and Consortium selection were based taking into account the present situation of the SCU-B facilities in different European countries.

For instance, Italy does not have a developed network of SCU-Bs, but only a few, whereas the outpatient clinics for PwD (called Centri per il Declino Cognitivo e la Demenza) are widespread.

In Germany, the treatment of BPSD and of some particular medical problems in severe dementia is provided by full sectorized care of the Psychiatric Hospitals in collaboration with Geriatric Internal Medicine specialists. Thus, more or less, all mental state Hospitals with an Old Age/Neuropsychiatric Psychiatry Department provide this care. Still, not all of these hospitals may have a dedicated special ward for dementia patients with severe behavioral disturbances, even though they all have to deal with these patients.

In Norway, psychiatric wards in all hospital trusts do admit PwD, but in their acute ward. Innlandet Hospital trust (Ottestad), which participate in the present study, is the only hospital trust with a SCU-B ward. But even there, persons with dementia are admitted to acute psychiatric wards, before being transferred to the SCU-B ward.

In France, there is a well-developed network of SCU-Bs called Unités Cognitivo-Comportementales, being parts of a National Alzheimer Plan and are widespread all over the country, while in Switzerland the situation is variable from one canton to another.

Other countries, such as Greece, completely lack such units. Therefore, Greek people with moderate to severe behavioral symptoms are usually treated at home mainly with antipsychotics drugs therapy, or they are referred to private hospitals. Nevertheless, on one hand the psychological burden of caregivers trying to cope with behavior is important, and on the other hand, the permanent admission to a private hospital often raises caregivers’ emotions of guilt. Due to the lack of these facilities in Greece, this country will participate in the RECage study only in the control group. In Greece, besides the fact that SCU-B do not exist, several day care centers for PwD provide help to patients and caregivers for coping with the neuropsychiatric symptoms. Therefore, the only treatment that can be provided in these centers to people with BPSD is pharmaceutical, support groups to their caregivers, and psychoeducation. The participation of these groups in the study was not excluded, since it was considered unethical to deprive patients of either pharmaceutical treatment or interventions to caregivers that could potentially help PwD to cope with behavioral and psychological symptoms. It is also worth noting that the above treatment can in no way be compared with the treatment that the experimental group will receive in SCU-Bs, which, as has been already described, comprises a combination of cautious pharmaceutical treatment with other non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as music and doll therapy or occupation therapy, cognitive-behavior therapy, and interventions for caregivers (psychoeducation and BPSD management techniques) as well, depending to the treatment followed in each SCU-B in the participated countries.

Some Italian and German clinical centers were invited to take part in the RECage Consortium due to the presence, in these countries, of centers “with” and “without SCU-Bs”. Besides the fact that there are differences among the participants, all centers had the experience, the resources, and the scientific background necessary to carry out the RECage project, and therefore were chosen.

The five clinical centers with SCU-B facilities chosen to participate the study comprised: 1) the “Fondazione Europea di Ricerca Biomedica (FERB)” in Gazzaniga, Italy, 2) the “Azienda Unita Sanitaria Locale di Modena (AUSLM)”, in Modena, Italy, 3) the “Université de Genève (UNIGE)” in Genève, Switzerland, 4) the “Zentralinstitut für Seelische Gesundheit (ZI)” in Mannheim, Germany, and 5) the “Innlandet Hospital trust (SI), in Ottestad, Norway.

The six centers without a SCU-B are: 1) the “Charité –Universitätsmedizin Berlin (CHARITE’)” in Berlin, Germany, 2) the “Universitá degli Studi di Perugia (UNIPG)”, in Perugia, Italy, 3) the “Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale di Mantova (ASSTM)”, in Mantova, Italy, 4) the “Cliniche Gavazzeni SpA (BG)”, in Bergamo, Italy, 5) the “Assistance Publique Hopitaux de Paris (AP-HP)” in Paris, France, and f) the “Aristotelio Panepistimio Thessalonikis (AUTH)”, in Thessaloniki, Greece.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the entrance of PwD with BPSD in the observational study are: 1) any age, 2) both males and females, 3) primary dementia diagnosis of any etiology according to the diagnostic criteria of (DSM IV), 4) score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≤24 [52] without a lower limit; 5) global score at Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [53]≥32/144; 6) a caregiver (informal, e.g., a family member, or formal caregiver, e.g., a paid one) who commits her/himself to accompany the PwD along the three-year course of the study and who live at home (nursing home residents are excluded).

As far as the BPSD types are concerned, all that are described in NPI will be assessed in the course of the three-year observational study; the electronic database that will be utilized (eCRF) for recording the study’s data does not comprise the total NPI score alone, but all the subtypes analytically, so as to be able to study their respective incidence and possible differences between the two groups.

Exclusion criteria are: 1) presence of uncontrolled physical diseases potentially contributing to the cognitive decline and BPSD, 2) concomitant psychiatric disorders or chronic alcoholism, and 3) concomitant diseases severe enough to reduce life expectancy.

Discontinuation and withdrawal criteria

Participants will be actively followed through all study visits until the final visit, during which the same assessment as the intermediate visits will be performed. Participants are free to withdraw from participation in the study at any time upon request. A participant will be considered lost to follow-up if he or she repeatedly fails to return for scheduled visits and is unable to be contacted by the study site. The following actions will be taken if a participant fails to return to the clinic for a required study visit:

• The site will attempt to contact the participant and reschedule the missed visit as soon as possible and counsel the participant on the importance of maintaining the assigned visit schedule and ascertain whether or not the participant wishes to and/or should continue in the study.

• Before a participant is deemed lost to follow up, the investigator or designee will make every effort to regain contact with the participant. These contact attempts should be documented in the participant’s medical record.

• Should the participant continue to be unreachable, he/she will be considered to have withdrawn from the study with a primary reason or lost to follow-up.

The expected drop-out rate is 25%.

Standard protocol approval and participants’ consents

After the adherence to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and before the patient’s recruitment in the RECage study, all participants will be informed orally and in written form regarding the study’s aim, its duration, the schedule of the follow-up visits, and the approximate time consumption for each visit as well. Furthermore, it will be stressed that, because of the observational nature of the study, the participant’s medical treatment will be personalized and not related to the study itself. Additionally, they will be informed that they can withdraw or refuse their participation to the study at any time they decide, without this affecting their treatment in any way. Fully informed valid consent will be obtained from all patients and caregivers who participate in the study; the written consent will be obtained by the patients themselves, if they are competent; for those who are not due to their cognitive status, an informed consent will be obtained by the legal representative/family caregiver according to the rules of the country.

As far as the data protection is consented, the participants and their caregivers will be informed that data will be collected through a web-based electronic CRF internally developed by Mediolanum Cardio Research, compliant with FDA 21 CFR part 11 and European Regulation and guidelines concerning security and data protection. Because of the nature of the study, personal data, such as the participant names and other information which might identify them, will be treated according to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, May 25, 2018) which states that the use of sensitive personal data is allowed only due to research reasons, will not be available to any person or group other than the clinicians of the center who referred the patients who have direct contact to them and will not appear in any presentation or publication resulting from this study. All clinical information will be kept in secure computer files protected by passwords and accessible only to the researchers involved in the study.

The study’s protocol will be reviewed and approved by independent Ethical Committees in the countries and centers that participate in this project and will be returned to the coordinating center that has experience of coordinating ethics approvals from multiple institutions.

Recruitment, screening, and follow-up visits

PwD will be recruited from the memory clinic of 11 aforementioned clinical centers. Even though the recruitment process will differ between centers according to the local standard of care, in many of them enrollment will be made during a regular visit in their memory clinics. Nine months were allotted to the centers to enroll patients.

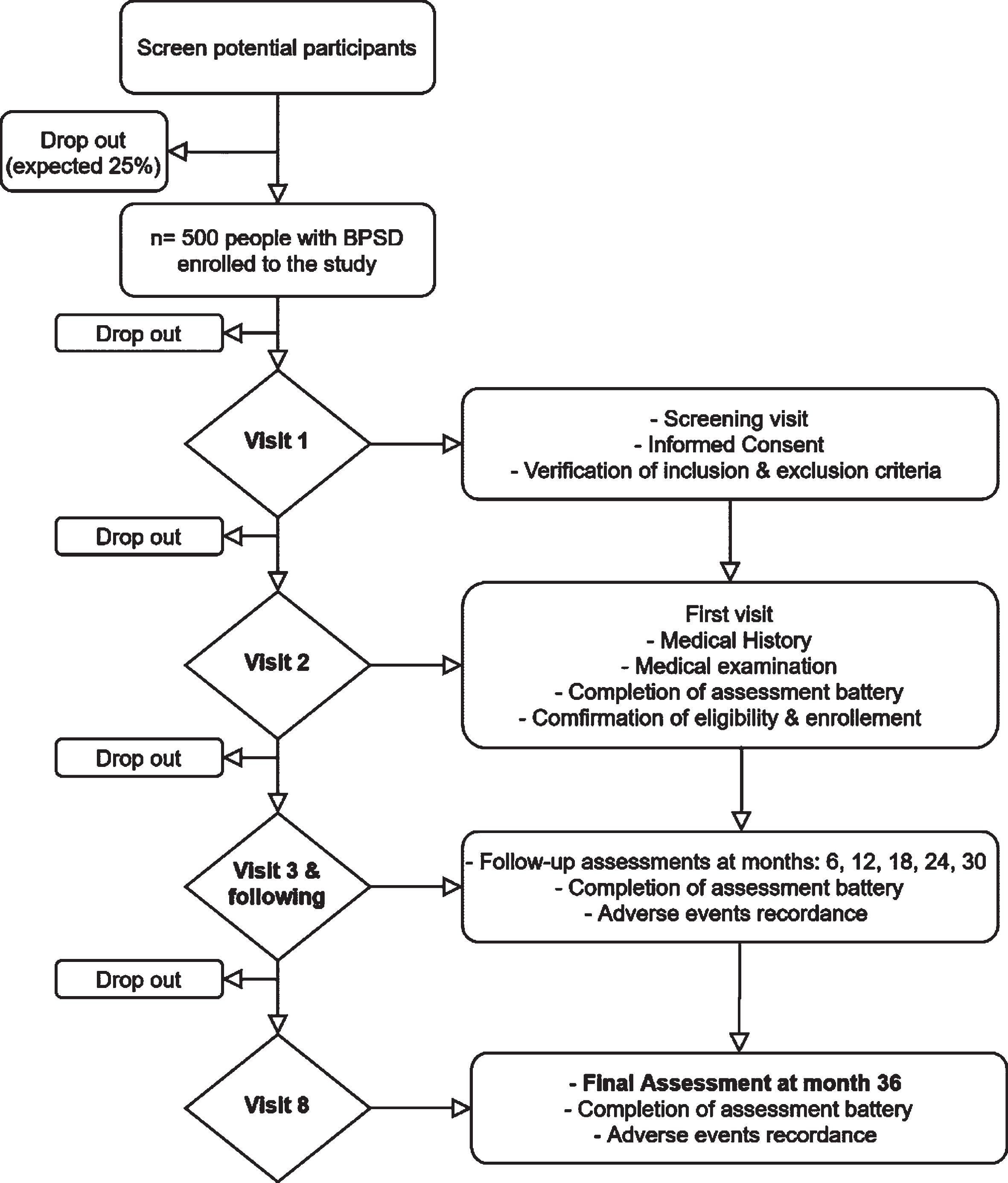

During the screening visit (Visit 1 –V1), all patients fulfilling the selection criteria, will have a first meeting with a physician (neurologist, geriatrician, or psychiatrist) who will orally illustrate the study and its goal; an information sheet of the study will be given to the PwD/caregiver. After the patient’s (or legal representative) and caregiver’s written consent the physician will collect data regarding patient’s and caregiver’s demographics, medical history and current medications, and a general physical examination with a short neurological examination will be performed either during the screening or up to 30 days before the baseline visit. The general protocol of the enrollment and the time points of the study are briefly presented in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Fig. 1

RECage study flowchart.

Table 1

Study endpoints

| Primary endpoint:Clinical efficacy, both short-and long-term, of the SCU-B. |

| Secondary endpoints: |

| 1) quality of life of patients and caregivers; |

| 2) cost-effectiveness of the SCU-B; |

| 3) psychotropic drug consumption over time; |

| 4) attitude of caregivers toward dementia. |

| Tertiary endpoint: time to nursing home placement. |

Due to the observational nature of the study, there are no exclusion criteria regarding the medication. However, all drugs and vaccines that the participant receives during enrolment or during the course of the 3 years study will be recorded, as well as the reason for their use, the dates of administration inc-luding start and end dates, and dosage information. Regarding the use of psychotropic drugs such as neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antiepileptics, and antiparkinsonian, will be carefully recorded as well.

Afterwards, during the baseline visit (Visit 2 –Time 0) (that will be performed on the same day of the screening visit or within 10 days from the V1), a detailed test battery will be administered by a psychologist, or another health care provider, depending each center’s structure. In order to avoid assessment’s bias, as best as possible, the same health care provider should administer the test battery at each following visit. After the re-confirmation of the selection criteria the patient will be assigned a number in the study. The precise procedure is briefly presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Outline and timelines of the study

| Procedure | Screening (up to 10 D before T0) | Study periods per months | ||||||

| T0 (±30 D) | T6 (±30 D) | T12 (±30 D) | T18 (±30 D) | T24 (±30 D) | T30 (±30 D) | T36 (±30 D) | ||

| Informed Consent | x | x | ||||||

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | x | |||||||

| Demographics | x | |||||||

| Brief physical exam | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Past and current medical conditions | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Vital signs | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| AE review | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| SAE review | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Concomitant medication review | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Rating scales/ questionnaires | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

T, times; D, days; AE, adverse events; SAE, serious adverse events.

As far as the intermediate visits is concerned, they will be scheduled every 6 months (Visit 2 –Visit 7), at months 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30, where medical data, medical examination, and assessment scales will be reviewed and updated by the physician and the health care provider, respectively. Adverse events as well as the following occurrences will be also recorded: 1) temporary admission to the SCU-B pertaining to the center, 2) admission to a SCU-B not pertaining to the participating center (that may happen in some centers, like Berlin, Paris or Bergamo-Gavazzeni which, even though lacking a SCU-B, can resort to an existing SCU-B located in the same town or nearby), and 3) institutionalization, that is nursing home placement. The final visit will be at month 30 (Visit 8). The same battery assessment and medical exams will be also performed. Any unscheduled visit will be considered as part of the usual standard care of the center.

Tools and assessments

A detailed battery of tests and scales for cognitive, neuropsychiatric, emotional, and economical assessment will be performed by neuropsychologist or other trained health care providers, at each of the 8 visits.

The complete battery, to be administrated at each visit, is the following: 1) MMSE for assessing general cognitive status [52], 2) Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living scale for assessing the general functional status [54], 3) NPI [53], and 4) Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) [50], for the assessment of the patient’s BPSD.

As far as the assessment of the patient’s QoL is concerned, the following scales were administered: 1) the proxy-version of the Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease (Qol-AD) [55, 56], 2) the EQ-5D-5L scale [57], for assessing the generic quality of life scale, and the 3) ICECAP-O [58], for assessing the QoL with preference-based tariffs.

Regarding the QoL of the caregiver, the following scales were administered: 1) the Adult Carer Quality of life Questionnaire (ACQoL) [59], 2) the EQ-5D-5L scale [57], 3) the Caregiver’s Burden Inventory (CBI) [60], and 4) the Dementia Attitude Scale (DAS) [61], for the assessment of caregiver’s attitude toward dementia were administered.

Finally, the Resource utilization scale (RUD) [62] was also utilized for the evaluation of the resource utilization and caregiver time.

Statistical analysis

As far as the data management, coding of medical terms and the statistical analysis of data of RECage project, will be managed by the Mediolanum Cardio Research SRL (MCR) informatic and statistical team. A sample size of 250 PwD in each of the two cohorts will allow to demonstrate between the two cohorts an effect size of about 0.25 (change of BPSD, recorded by NPI and CMAI rating scales, from baseline to the final visit standardized by the phenomenon variability) at a Student’s t test for unpaired data with a power of 0.80 and a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). Since the actual analysis of the change will be done according to an ANOVA/ANCOVA mixed model for repeated measurements described in the following, the above sample size has been calculated according to a simple statistical analysis in order to avoid the guess of the variance-covariance matrix pattern of the repeated measurements and have a conservative number allowing for the dropout rate. Furthermore, the data will be analyzed according to the Intention to treat (ITT) principle by including all the available data of the enrolled patients who have at least one follow-up visit after baseline independently from protocol violations.

Within each cohort, quantitative variables will be summarized by arithmetic mean, standard deviation, median, first and third quartile (Q1, Q3), and minimum and maximum; qualitative variables will be summarized by absolute frequencies and percentages. 95%Confidence Intervals (CI) will be calculated for means and proportions of the main clinically relevant variables.

Baseline quantitative characteristics will be compared among the two cohorts by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or its alternative non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis) in the case of a skew distribution (difference between mean and median more than 30%). Student’s t test for unpaired data or its alternative non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test will be used in the case of only two groups. In the case of statistically significant difference a factorial ANOVA will be carried out for the comparison between the cohorts taking into account other factors such as gender, disease severity, etc.

Cohorts will be compared for qualitative variables by means of the chi-squared test. In the case of a statistically significant difference, multivariable logistic regression will be used together with the above reported factors.

The primary endpoint (comparison of the change of BPSD between the cohorts) will be measured through the NPI and CMAI scales over time (at time 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36 months/final study visit) and the pattern of the score of NPI and CMAI scales over the time will be compared between the two cohorts after having matched the PwD, according to the propensity score method, by means of a repeated measures ANOVA/ANCOVA mixed model with the baseline value and age as covariates, time, cohort, and gender as fixed factors, and finally, subject as a random factor.

The problem of the missing data, assumed from a Missing At Random (MAR) mechanism, will be considered by fitting mixed models with different variance-covariances matrix (proc Mixed of SAS: Statistical Analysis Software, Version 9.2, at least). Several variance-covariance matrices will be considered in order to obtain the model with the lowest Akaike’s Information criterion in the context of General Linear Models, Heterogeneous General Linear Model, and Random Coefficients Linear Model.

In the case of a no statistically significant interaction term “times by cohorts” and a statistically sig-nificance of the term “time”, the comparisons among the times will be carried out according to linear, qua-dratic, cubic, etc., polynomial contrasts. In the case of statistically significant interaction “time by group”, the above polynomial contrasts of the times will be carried out within each cohort.

The parametric statistical analyses will be relay on the property of the Central Limit theorem and on the robustness of the ANOVA/ANCOVA procedure. Furthermore, the ANCOVA method will be replaced by the ANOVA in the case of a statistically significance of the parallelism test.

A sensitivity analysis will be carried out by considering different number of classes of the propensity score, the propensity score as a continuous variable and without the propensity score.

The secondary efficacy quantitative end-points recorded at the above times, will be analyzed according the above reported ANOVA/ANCOVA mixed factorial model for repeated measurements. This statistical model will be carried out on the “Quality of Life (QoL) of patients and caregivers”, estimated through QoL-AD and EQ-5D-5L (patient) and ACQoL, EQ-5D-5L, CBI (caregiver), the “change in care costs over time” and “Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio”, estimated through RUD, ICECAP-O and EQ-5D-5L, and, finally, the “change of attitude of caregivers toward dementia”, assessed through Dementia Attitude Scale (DAS).

The secondary endpoint “comparison of the drug consumption between the cohorts” will be measured through the cumulative number of psychotropic drugs used by each PwD standardized by his/her follow-up time and compared by the Wilcoxon test.

The tertiary (exploratory) endpoint (time of the definitive admission to a nursing home) will be analyzed by using the Kaplan-Meier method for estimating the probability of the not occurrence of an event. Then, the comparisons between the two cohorts will be carried out by the Logrank test stratified by the propensity score classes and by the Cox’s proportional hazard regression for a multivariable analysis taking into account some known predictors of the event and some baseline characteristics actually associated with the considered event. The assessment of the statistical assumption of the proportional hazard Cox’s regression will be carried out. Qualitative safety data will be compared by means of a chi-squared test at each visit and overall. All the statistical analyses will be carried out at the nominal statistical significance of 0.05. However, in the case of a statistically significance results, multiple comparisons will be done conservatively by using the Bonferroni’s correction. SAS Version 9.4 will be used to carry out the analyses. STATA and R or Excel will be used for health-economic analyses.

RESULTS

The RECAGE study is a study in progress, therefore no final results exist yet. Nevertheless, there are some expected results yielding from the REcage protocol main objectives and hypotheses that will be presented below.

It is expected that people, after their admission in a SCU-B, in comparison to the cohort followed by the no-SCU-B centers will have:

1) less behavioral problems, according to NPI and CMAI scales pattern over the follow-up time (primary objective);

2) a higher performance QoL pattern, measured by the QoL-AD and EQ-5D-5L scales (secondary objective);

3) reduced costs, according to RUD, ICECAP-O, and EQ-5D-5L scales (secondary objective);

4) a lower number of psychotropic drug consumption (secondary objective);

5) a lower probability of an earlier admission to nursing homes, estimated by univariate and multivariate survival analysis (tertiary objective).

In addition, it is expected that the caregivers of patients admitted in SCU-Bs in comparison to the caregivers of PwDs followed by centers lacking a SCU-B will show:

1) higher scores in QoL, measured by ACQoL, EQ-5D-5L, and CBI scales, during the follow-up time;

2) an improved attitude toward dementia, assessed by DAS, due to the psychoeducation and psychotherapy interventions received in SCU-Bs.

DISCUSSION

RECage project is a three-year multicenter prospective observational study which has as primary objective to evaluate both short and (mainly) long-term efficacy of SCU-Bs as components of the care pathways for PwD. The SCU-B follows a more person-centered philosophy and therefore, adapts a therapeutic process which comprises a more cautious pharmaceutical treatment in combination with non-pharmaceutical interventions both for patients and caregivers. Therefore, it aims to assess the QoL, not only of patients, but also of caregivers and to estimate the psychotropic drug consumption against the cost-effectiveness of SCU-Bs. Last but not least, RECage aims to explore the capacity of SCU-B to delay institutionalization.

Even though it is not possible to know whether our main hypothesis and the side ones will be confirmed, some potential answers could be derived. Besides the fact that the short-term effectiveness of SCU-Bs in migrating BPSD compared to no-SCU-Bs is, according to some studies, already proved [48, 49], the long-term SCU-Bs efficacy is under investigation.

A more detailed discussion regarding the potential effects of the centers with SCU-Bs versus the no SCU-B centers and the potential answers of our hypothesis follows.

Changes in QoL and in attitude toward dementia

BPSD as a major problem in the course of dementia, lead to increased caregiver’s psychological burden and [15] diminished quality of caregivers’ life [63, 64]. BPSD also affect patients’ life by reducing QoL, due to over-medication that is usually applied for managing symptoms, and also due to the reduced carer’s desire to be engaged with the person with dementia into a social environment [65]. Nowadays, it is evident that psychological interventions are effective both for people with BPSD and their caregivers by minimizing patients’ BPSD and by enhancing QoL for both, therefore reducing the burden of caregivers [66]. Patients from countries without SCU-Bs and other associated centers, usually do not have access to such facilities and as a result, caregivers utilize mostly pharmaceutical treatment and avoid the social contacts. Based on that, the services provided in SCU-Bs (which mostly comprise non-pharmaceutical interventions), could potentially improve QoL in patients and caregivers.

The improvement of QoL both for patients and caregivers is also associated with the attitude that caregivers have toward dementia. In many cases, caregivers with less access in information regarding dementia and without SCU-Bs are used to retain their stereotypes about the disease and therefore, to believe that behavioral problems are controllable by the patients and consequently they lead to misconceptions about the disease and deterioration of patient’s behavior [70, 71]. The psycho-education programs are utilized by SCU-Bs, accompanied by behavior management techniques which center on individual patient’s and caregiver’s behaviors, can lead to a better understanding of the needs of PwD and also the reasons behind each behavioral problem. Therefore, it is possible that caregivers change their attitude toward dementia and provide better care and QoL for their patients but also for themselves. As well known, BPSD are associated with several biological, psychosocial, psychological, and environmental factors that can lead to a behavioral crisis [47]. For example, a problematic behavior can be caused by an untreated or undertreated pain or because of an over stimulating environment, e.g., a noisy environment, or even because of a caregiver’s psychological situation (e.g., stress and depression) [70]. Since SCU-Bs provide the above services, we assume that the caregivers’ attitude toward dementia will be possibly improved in comparison to the attitudes of the caregivers without SCU-B.

SCU-B’s cost effectiveness and psychotropic drug consumption

BPSD constitutes a situation that is quite costly for caregivers [7, 17]. Dementia costs are divided to direct and indirect. Direct costs include visits to medical doctors and/or hospitals, medications, home care nurses, day programs, etc., where indirect costs are associated with the caregiver, such as the time that the caregiver spends away from work or the lack of leisure activities by the caregiver or the patient, as a result of the disease [7]. Caregivers are forced to seek help from medical health providers in order to pursue medical treatment, to increase the pharmaceutical treatment, or even to hire a formal caregiver for helping them when they are out of home, e.g., when they are at work, a fact that can lead to increased costs of care. As a result, caregivers have extra costs, especially when the patients’ behavioral problems are delusions, hallucinations, or agitation of high severity [17]. People with BPSD who are admitted in SCU-Bs and also their caregivers are provided with a variety of non-pharmaceutical interventions and cautious pharmaceutical treatment for a short time period, until the behavioral crisis ends. As a consequence, both the direct and the indirect costs associated with BPSD may be diminished for people who are admitted to SCU-Bs in comparison to people who are at home care during the three years of period, while the admission in SCU-Bs may be more cost effective.

Another issue which is directly associated with raised costs in dementia care is medical treatment for BPSD. While non-pharmaceutical treatment for BPSD is in the first line of therapy [45, 48, 67], the pharmaceutical treatment is associated with noteworthy side effects that range from severe medical conditions and mortality to cognitive decline and deterioration of the functionality in activities of daily living [45, 68, 69]. The use of antipsychotic drugs is nowadays still in a widespread utilization among patients with BPSD. For several cases, the pharmaceutical treatment with drugs with psychotropic effects are the only alternative to the treatment of BPSD, when no other facilities/units which provide alternative types of therapy exists [69]. The medical treatment in SCU-Bs by following the current guidelines for the treatment of BPSD emphasizes in a bio-psycho-social framework for behavioral changes in PwD [70]. Since the majority of SCU-Bs follows a cautious drug treatment in order to cope with severe BPSD, we assume that the admission to SCU-Bs will be associated with less drug consumption compared to the countries with no BPSD which are forced to seek help to medical solutions.

Institutionalization of people with BPSD

Institutionalization, especially in late stages of dementia, is a quite common caregiver’s decision, when behavioral problems are difficult to be controlled [5]. The emotional reaction to patient’s behavior and the lack of the appropriate caregiver’s education in BPSD management play a more crucial role in the decision of institutionalization, than the behavioral problems per se [72]. The lack of SCU-Bs and as a result, the lack of appropriate care and education in several centers among countries, may be another cause for the early admission to institutes, such as in nursing homes. Patients with BPSD are admitted to SCU-Bs for a short time period depending on each SCU-B regulation and return to their homes when the behavioral crisis ends. Even if the possibility of regression always exists and the person with BPSD may to return to a SCU-B, the short-term admission philosophy of SCU-Bs prohibits the patient’s permanent institutionalization that leads to diminished QoL [73, 74]. On the contrary, caregivers in centers without SCU-B, face a great burden and as a result they usually decide their patients’ permanent institutionalization. Relative study which assesses the effect of behavioral symptoms on the institutionalization of patients with dementia confirms that a great percent (41%) of patients with BPSD are institutionalized during the two-year period after the symptoms’ onset [72] and furthermore, the distress related to BPSD was a significant predictor of the institutionalization. The delay of the early institutionalization for a long time period is always the ultimate goal of SCU-Bs, and we assume that via the therapeutic process of these units, people with BPSD will minimize institutionalization compared to people with no access in such facilities.

CONCLUSIONS

SCU-Bs are not widespread all over the European countries and, where they exist, a large heterogeneity is presented both among countries and within the same country. Besides the differentiations of SCU-Bs in structure, they show many similarities regarding 1) the therapy they utilize, 2) the specialized health care professionals, 3) the special architectural features, and 4) in some extent the admission criteria. The return of a patient back home and the patient’s and caregiver’s QoL assurance are always desired goals. The SCU-B model gives priority to patient’s and caregiver’s dignity and tries to avoid the possibility of patient’s permanent institutionalization because of uncontrolled behavioral difficulties.

Via this study’s upcoming results, we hope to pave the way for the adoption of the SCU-B model on a larger scale and to decrease the differences of existent SCU-Bs so as to achieve uniformity in operations. At the end of the RECage project, specific recommendations will be created for the implementation of the intervention, initially in the countries who take part in the study and in later steps in other EU countries. Based on the RECage project’s expected results, a plan for scaling up the intervention in countries where SCU-B does not exist, such as Greece, will be also provided.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 779237.

The content of this publication represents the views of the authors only and is their sole responsibility and the Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-1215r2).

REFERENCES

[1] | Patterson C ((2018) ) World Alzheimer Report 2018. The state of the art of dementia research: New frontiers, Alzheimer’s Disease International, London. |

[2] | World Health Organization, Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. |

[3] | Ipa-online.org, IPA Complete Guides to Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). International Psychogeriatric Association. |

[4] | Lyketsos C ((2000) ) Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: Findings from the Cache County study on memory in aging. Am J Psychiatry 157: , 708–714. |

[5] | Backhouse T , Camino J , Mioshi E ((2018) ) What do we know about behavioral crises in dementia? A systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis 62: , 99–113. |

[6] | Maust D , Kales H , McCammon R , Blow F , Leggett A , Langa K ((2017) ) Distress associated with dementia-related psychosis and agitation in relation to healthcare utilization and costs. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 25: , 1074–1082. |

[7] | Herrmann N , Lanctôt K , Sambrook R , Lesnikova N , Hébert R , McCracken P , Robillard A , Nguyen E ((2006) ) The contribution of neuropsychiatric symptoms to the cost of dementia care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 21: , 972–976. |

[8] | Gitlin LN , Kales HC , Lyketsos CG ((2012) ) Managing behavioral symptoms in dementia using nonpharmacologic approaches: An overview. JAMA 308: , 2020–2029. |

[9] | Prince M , Jackson J ((2009) ) World Alzheimer Report 2009. Alzheimer’s Disease International, London. |

[10] | Cerejeira J , Lagarto L , Mukaetova-Ladinska E ((2012) ) Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol 3: , 73. |

[11] | Zhao Q , Tan L , Wang H , Jiang T , Tan M , Tan L , Xu W , Li J , Wang J , Lai T , Yu J ((2016) ) The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 190: , 264–271. |

[12] | Lima-Silva T , Bahia V , Carvalho V , Guimarães H , Caramelli P , Balthazar M , Damasceno B , Bottino C , Brucki S , Nitrini R , Yassuda M ((2015) ) Neuropsychiatric symptoms, caregiver burden and distress in behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 40: , 268–275. |

[13] | Kales H , Gitlin L , Lyketsos C ((2015) ) Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ 350: , h369–h369. |

[14] | Kuring J , Mathias J , Ward L ((2018) ) Prevalence of depression, anxiety and PTSD in people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev 28: , 393–416. |

[15] | Boutoleau-Bretonnière C , Vercelletto M , Volteau C , Renou P , Lamy E ((2008) ) Zarit Burden Inventory and Activities of Daily Living in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 25: , 272–277. |

[16] | Bonnici-Mallia AM , Barbara C , Rao R ((2018) ) Vascular cognitive impairment and vascular dementia. InnovAiT 11: , 249–255. |

[17] | D’Onofrio G , Sancarlo D , Panza F , Copetti M , Cascavilla L , Paris F , Seripa DG , Matera M , Solfrizzi V , Pellegrini F , Pilotto A ((2012) ) Neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional status in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia patients. Curr Alzheimer Res 9: , 759–771. |

[18] | Odawara T , Manabe Y , Konishi O ((2019) ) A survey of doctors on diagnosis and treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies: Examination and treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Psychogeriatrics 19: , 310–319. |

[19] | Kolanowski A , Boltz M , Galik E , Gitlin L , Kales H , Resnick B , Van Haitsma K , Knehans A , Sutterlin J , Sefcik J , Liu W , Petrovsky D , Massimo L , Gilmore-Bykovskyi A , MacAndrew M , Brewster G , Nalls V , Jao Y , Duffort N , Scerpella D ((2017) ) Determinants of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A scoping review of the evidence. Nurs Outlook 65: , 515–529. |

[20] | Mukherjee A , Biswas A , Roy A , Biswas S , Gangopadhyay G , Das S ((2017) ) Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: Correlates and impact on caregiver distress. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 7: , 354–365. |

[21] | Gentile S ((2010) ) Second-generation antipsychotics in dementia: Beyond safety concerns. A clinical, systematic review of efficacy data from randomised controlled trials. Psychopharmacology 212: , 119–129. |

[22] | Ijaopo E ((2017) ) Dementia-related agitation: A review of non-pharmacological interventions and analysis of risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy. Transl Psychiatry 7: , e1250–e1250. |

[23] | Reus V , Fochtmann L , Eyler A , Hilty D , Horvitz-Lennon M , Jibson M , Lopez O , Mahoney J , Pasic J , Tan Z , Wills C , Rhoads R , Yager J ((2016) ) The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry 173: , 543–546. |

[24] | Steinberg M , Lyketsos C ((2012) ) Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: Managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry 169: , 900–906. |

[25] | Emanuel J , Lopez O , Houck P , Becker J , Weamer E , DeMichele-Sweet M , Kuller L , Sweet R ((2011) ) Trajectory of cognitive decline as a predictor of psychosis in early Alzheimer disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 19: , 160–168. |

[26] | Russ T , Batty G , Starr J ((2011) ) Cognitive and behavioural predictors of survival in Alzheimer disease: Results from a sample of treated patients in a tertiary-referral memory clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 27: , 844–853. |

[27] | Ma H , Huang Y , Cong Z , Wang Y , Jiang W , Gao S , Zhu G ((2014) ) The efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Alzheimers Dis 42: , 915–937. |

[28] | Jin B , Liu H ((2019) ) Comparative efficacy and safety of therapy for the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systemic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Neurol 266: , 2363–2375. |

[29] | Press-Sandler O , Freud T , Volkov I , Peleg R , Press Y ((2016) ) Aromatherapy for the treatment of patients with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A descriptive analysis of RCTs. J Altern Complement Med 22: , 422–428. |

[30] | Fakhoury N , Wilhelm N , Sobota K , Kroustos K ((2017) ) Impact of music therapy on dementia behaviors: A literature review. Consult Pharm 32: , 623–628. |

[31] | Wu J , Wang Y , Wang Z ((2017) ) The effectiveness of massage and touch on behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: A quantitative systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 73: , 2283–2295. |

[32] | Moyle W , Murfield J , Jones C , Beattie E , Draper B , Ownsworth T ((2018) ) Can lifelike baby dolls reduce symptoms of anxiety, agitation, or aggression for people with dementia in long-term care? Findings from a pilot randomised controlled trial. Aging Ment Health 23: , 1442–1450. |

[33] | Yakimicki M , Edwards N , Richards E , Beck A ((2018) ) Animal-assisted intervention and dementia: A systematic review. Clin Nurs Res 28: , 9–29. |

[34] | Hjetland G , Pallesen S , Thun E , Kolberg E , Nordhus I , Flo E ((2020) ) Light interventions and sleep, circadian, behavioral, and psychological disturbances in dementia: A systematic review of methods and outcomes. Sleep Med Rev 52: , 101310. |

[35] | Strøm B , Ytrehus S , Grov E ((2016) ) Sensory stimulation for persons with dementia: A review of the literature. J Clin Nurs 25: , 1805–1834. |

[36] | Koder D ((2016) ) The use of cognitive behaviour therapy in the management of BPSD in dementia (Innovative practice). Dementia 17: , 227–233. |

[37] | Sakurai H , Terayama H , Jaime R , Otakeguchi K , Hirao K , Sato T , Shimizu S , Kanetaka H , Umahara T , Hanyu H ((2017) ) Caregivers’ education decreases depressive symptoms and burden in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Neurol Sci 381: , 1137. |

[38] | Dimitriou TD , Verykouki E , Papatriantafyllou J , Konsta A , Kazis D , Tsolaki M ((2018) ) . Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation/aggressive behaviour in patients with dementia: A randomized controlled crossover trial. Funct Neurol 33: , 143–147. |

[39] | Dimitriou T , Verykouki E , Papatriantafyllou J , Konsta A , Kazis D , Tsolaki M ((2020) ) Non-pharmacological interventions for the anxiety in patients with dementia. A cross-over randomised controlled trial. Behav Brain Res 390: , 112617. |

[40] | Jones M ((1999) ) Gentlecare: Changing the experience of Alzheimer’s disease in a positive way, Hartley & Marks Publishers. |

[41] | Gallese G , Stobbione T ((2013) ) “Need-driven-dementia-compromised-behavior” model and “gentle care” as answer to Alzheimer’s disease. Prof Inferm 66: , 39–47. |

[42] | Fazio S , Pace D , Flinner J , Kallmyer B ((2018) ) The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. Gerontologist 58: , S10–S19. |

[43] | Kitwood T ((1997) ) Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Open University Press, Buckingham. |

[44] | Frederiksen K , Cooper C , Frisoni G , Frölich L , Georges J , Kramberger M , Nilsson C , Passmore P , Mantoan Ritter L , Religa D , Schmidt R , Stefanova E , Verdelho A , Vandenbulcke M , Winblad B , Waldemar G ((2020) ) A European Academy of Neurology guideline on medical management issues in dementia. Eur J Neurol 27: , 1805–1820. |

[45] | Reese TR , Thiel DJ , Cocker KE ((2016) ) Behavioral disorders in dementia: Appropriate nondrug interventions and antipsychotic use. Am Fam Physician 15: , 276–282. |

[46] | Azermai M , Petrovic M , Elseviers M , Bourgeois J , Van Bortel L , Vander Stichele R ((2012) ) Systematic appraisal of dementia guidelines for the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms. Ageing Res Rev 11: , 78–86. |

[47] | Gauthier S , Cummings J , Ballard C , Brodaty H , Grossberg G , Robert P , Lyketsos C ((2010) ) Management of behavioral problems in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 22: , 346–372. |

[48] | Delphin-Combe F , Roubaud C , Martin-Gaujard G , Fortin ME , Rouch I , Krolak-Salmon P ((2013) ) Effectiveness of a cognitive-behavioral unit on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Rev Neurol 169: , 490–494. |

[49] | Koskas P , Belqadi S , Mazouzi S , Daraux J , Drunat O ((2010) ) Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in a pilot psychogeriatric unit: Management and outcomes. Rev Neurol 167: , 254–259. |

[50] | Colombo M , Vitali S , Cairati M , Vaccaro R , Andreoni G , Guaita A ((2007) ) Behavioral and psychotic symptoms of dementia (BPSD) improvements in a special care unit: A factor analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 44: , 113–120. |

[51] | Bianchetti A , Benvenuti P , Ghisla K , Frisoni G , Trabucchi M ((1997) ) An Italian model of dementia special care unit. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 11: , 53–56. |

[52] | Folstein MF , Folstein SE , McHugh PR ((1975) ) “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12: , 189–198. |

[53] | Cummings J ((1997) ) The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology 48: , 10S–16S. |

[54] | Galasko D , Bennett D , Sano M , Ernesto C , Thomas R , Grundman M , Ferris S ((1997) ) An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 11: , 33–39. |

[55] | Finkel S , Lyons J , Anderson R ((1992) ) Reliability and validity of the Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory in institutionalized elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 7: , 487–490. |

[56] | Torisson G , Stavenow L , Minthon L , Londos E ((2016) ) Reliability, validity and clinical correlates of the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s disease (QoL-AD) scale in medical inpatients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 14: , 90. |

[57] | Brooks R ((1996) ) EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy 37: , 53–72. |

[58] | Coast J , Flynn T , Natarajan L , Sproston K , Lewis J , Louviere J , Peters T ((2008) ) Valuing the ICECAP capability index for older people. Soc Sci Med 67: , 874–882. |

[59] | Elwick H , Joseph S , Becker S , Becker F (2010) Manual for the Adult Carer Quality of Life Questionnaire (AC-QoL). The Princess Royal Trust for Carers, London. |

[60] | Novak M , Guest C ((1989) ) Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist 29: , 798–803. |

[61] | O’Connor M , McFadden S ((2010) ) Development and psychometric validation of the Dementia Attitudes Scale. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2010: , 454218. |

[62] | Wimo A , Wetterholm AL , Mastey V , Winblad B ((1998) ) Evaluation of the resource utilization and caregiver time in Anti-dementia drug trials –a quantitative battery. In The Health Economics of Dementia, Wimo A, Karlsson G, Jönsson B, Winblad B, eds. Wiley, London. |

[63] | Schumann C , Alexopoulos P , Perneczky R ((2019) ) Determinants of self-and carer-rated quality of life and caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 34: , 1378–1385. |

[64] | Feast A , Orrell M , Russell I , Charlesworth G , Moniz-Cook E ((2017) ) The contribution of caregiver psychosocial factors to distress associated with behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 32: , 76–85. |

[65] | Lowery D , Warner J ((2009) ) Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): The personal and practical costs of dementia. J Integr Care 17: , 13. |

[66] | Poon E (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of dyadic psychological interventions for BPSD, quality of life and/or caregiver burden in dementia or MCI. Clin Gerontol, doi: 10.1080/07317115.2019.169411 |

[67] | Livingston G , Kelly L , Lewis-Holmes E , Baio G , Morris S , Patel N , Omar RZ , Katona C , Cooper C ((2014) ) A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sensory, psychological and behavioural interventions for managing agitation in older adults with dementia. Health Technol Assess 18: , 1–226. |

[68] | Wang F , Feng TY , Yang S , Preter M , Zhou JN , Wang XP ((2016) ) Drug therapy for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Curr Neuropharmacol 14: , 307–313. |

[69] | Taipale H , Koponen M , Tanskanen A , Tolppanen AM , Tiihonen J , Hartikainen S ((2014) ) High prevalence of psychotropic drug use among persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease in Finnish nationwide cohort. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 24: , 1729–1737. |

[70] | Kales HC , Gitlin LN , Lyketsos CG , Detroit Expert Panel on Assessment and Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia ((2014) ) Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: Recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc 62: , 762–769. |

[71] | Paton J , Johnston K , Katona C , Livingston G ((2004) ) What causes problems in Alzheimer’s disease: Attributions by caregivers. A qualitative study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19: , 527–532. |

[72] | de Vugt ME , Stevens F , Aalten P , Lousberg R , Jaspers N , Verhey FR ((2005) ) A prospective study of the effects of behavioral symptoms on the institutionalization of patients with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 17: , 577–589. |

[73] | Grossman P , Tiefenthaler-Gilmer U , Raysz A , Kesper U ((2007) ) Mindfulness training as an intervention for fibromyalgia: Evidence of postintervention and 3-year follow-up benefits in well-being. Psychother Psychosom 76: , 226–233. |

[74] | Risco E , Cabrera E , Jolley D , Stephan A , Karlsson S , Verbeek H , Saks K , Hupli M , Sourdet S , Zabalegui A , RightTimePlaceCare Consortium ((2015) ) The association between physical dependency and the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms, with the admission of people with dementia to a long-term care institution: A prospective observational cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud 52: , 980–987. |