The Impact of a Global Pandemic on People Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: Analysis of 417 Lived Experience Reports

Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic is impacting the physical and emotional health of older adults living with dementia and their care partners.

Objective:

Using a patient-centered approach, we explored the experiences and needs of people living with dementia and their care partners during the COVID-19 pandemic as part of an ongoing evaluation of dementia support services in British Columbia, Canada.

Methods:

A survey instrument was developed around the priorities identified in the context of the COVID-19 and Dementia Task Force convened by the Alzheimer Society of Canada.

Results:

A total of 417 surveys were analyzed. Overall, respondents were able to access information that was helpful for maintaining their own health and managing a period of social distancing. Care partners reported a number of serious concerns, including the inability to visit the person that they care for in long-term or palliative care. Participants also reported that the pandemic increased their levels of stress overall and that they felt lonelier and more isolated than they did before the pandemic. The use of technology was reported as a way to connect socially with their loved ones, with the majority of participants connecting with others at least twice per week.

Conclusion:

Looking at the complex effects of a global pandemic through the experiences of people living with dementia and their care partners is vital to inform healthcare priorities to restore their quality of life and health and better prepare for the future.

INTRODUCTION

In the midst of the current global health crisis, it is especially important to capture the lived experiences of older adults and their care partners to inform priorities for health care services. The COVID-19 pandemic that surfaced in late 2019 has resulted in governments being called to action to manage the spread of the virus by limiting travel and closing businesses, disrupting the daily lives and routines of everyone. Public health authorities have advised drastic changes to everyday activities, including social distancing, limiting public gatherings, and restricting outings outside of the home. With these measures, there is an urgent need to focus on restoring and improving the quality of life and health outcomes for all people, particularly those who are vulnerable.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had important negative consequences for the lives of older adults as the virus has a significant impact on their physical and emotional health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), older adults are at a greater risk of severe illness if they contract COVID-19 due to “physiological changes that come with ageing and potential underlying health conditions” [1]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that to date, 8 out of 10 COVID-19 related deaths in the United States have been among adults aged 65 years and older [2]. For the province of British Columbia in Canada, where the present study was conducted, the first confirmed case was reported on January 26, 2020, and a provincial state of emergency was declared March 18, 2020 [3]. Additional risk factors included being over the age of 50, male, or having at least one chronic condition [4]. In addition, older adults living in long-term care facilities are at a higher risk for adverse outcomes due to their close proximity to others [5] and daily care needs [6]. With new regulations that have been implemented rapidly with limited preparation time, daily routines and activities have had to quickly adapt, especially for people living with dementia and their care partners. People living with dementia may be more restricted and confined within the home without opportunities to step out to get groceries, attend regular health care services, receive home care support, or access community supports and social networks. As in-person support has been temporarily suspended or transitioned to a virtual setting, for many the only option for social connectedness has been through the use of technology such as video calls, where available. In addition, families and care partners may encounter challenges in caring for a loved one living with dementia, such the inability to physically see their loved ones in a long-term care home.

This new and rapidly evolving context is leading to important ethical and social issues in dementia care. The rising rate of infected individuals puts a strain on the number of available hospital beds, ICU bed, and ventilators [7, 8], as well as available doctors and nurses to provide care if they become ill or quarantined [9]. Concerns have also been raised regarding the allocation of resources including vaccines and therapies to combat the virus [8, 10]. Social isolation and feelings of loneliness have been reported in older adults due to factors such as bereavement and living alone [11], which puts them at a greater risk of poor physical and mental health, higher mortality, and dementia [12]. With the extreme measures implemented as a result of the ongoing global pandemic, the well-being of people living with dementia and their care partners is of increased concern. For people living with dementia, whether at home or in long-term care facilities, they may feel heightened levels of loneliness as families and care partners are kept from visiting [13]. Beyond loneliness, limitations on visits also impact representation and advocacy for this population, with important negative consequences, such as instances where residents of long-term care facilities have been treated with potential pharmaceutical interventions without their consent [14]. As for care partners who are practicing social distancing, they may develop unhealthy coping habits due to isolation.

The impact of COVID-19 and associated health policies on individuals living with dementia is the subject of active research, including investigations of effects on neuropsychiatric symptoms [15], possible biological interactions between COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s disease [16], access to COVID-19 treatment for dementia patients [17], and actions that might mitigate harm to this group [18]. However, patient and provider perspectives on healthcare decisions often differ [19]. Therefore, it is important to develop pandemic-specific dementia services together with the populations who will use them: individuals with a lived experience of dementia and their care partners. As part of an ongoing evaluation of dementia support services in British Columbia, Canada, we aimed to better understand the experiences and needs of people living with dementia and their care partners during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

All study protocols were approved by the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board. In close collaboration with Alzheimer Society of British Columbia, a survey instrument was developed for both people living with dementia and their care partners around the priorities identified in the context of the COVID-19 and Dementia Task Force convened by the Alzheimer Society of Canada [20].

The survey was piloted by the research team and persons with lived experience of dementia and refined before launching using Qualtrics survey software on June 8, 2020. Participants were recruited from the Alzheimer Society of B.C. as well as through relevant Twitter accounts. Inclusion criteria for participation in the survey were: 1) the ability to read and write English, 2) aged 19 or older, 3) self-identifies as having lived experience of dementia or is in a care partner role for someone living with dementia.

Consent was obtained on the landing page of the survey and in line with COVID-19-specific research ethics protocols, participants were informed that the survey consisted of questions regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and were asked not to consent if they did not wish to answer questions about the pandemic. The survey instruments included questions around the following themes: 1) information and resource needs, 2) caring for someone living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic (specific to care partner surveys), 3) mental health and well-being needs, 4) the use of technology for social connection during the pandemic.

Responses for a participant were excluded from analysis if respondents responded to fewer than three content (i.e., non-demographic) questions. Survey data were visualized using the ggplot2 package in RStudio software [21]. Where indicated in the results, for simplicity of visualizations we sometimes collapsed responses on 5- and 7-point scales into three bins (e.g., a scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree collapsed down to three bins: disagree, neither agree nor disagree, and agree).

RESULTS

Sample

A total of 498 participant surveys were collected between June 8, 2020 and August 19, 2020. From these, n = 81 were excluded for failing to respond to at least three content (i.e., non-demographic) questions, resulting in a final sample of 395 care partners and 22 individuals with lived experiences of dementia. In addition, all responses were read by the research team to ensure their relevance to the study. Where percentages are reported below for both groups, the order is as follows: (care partners, persons living with dementia).

Participant information

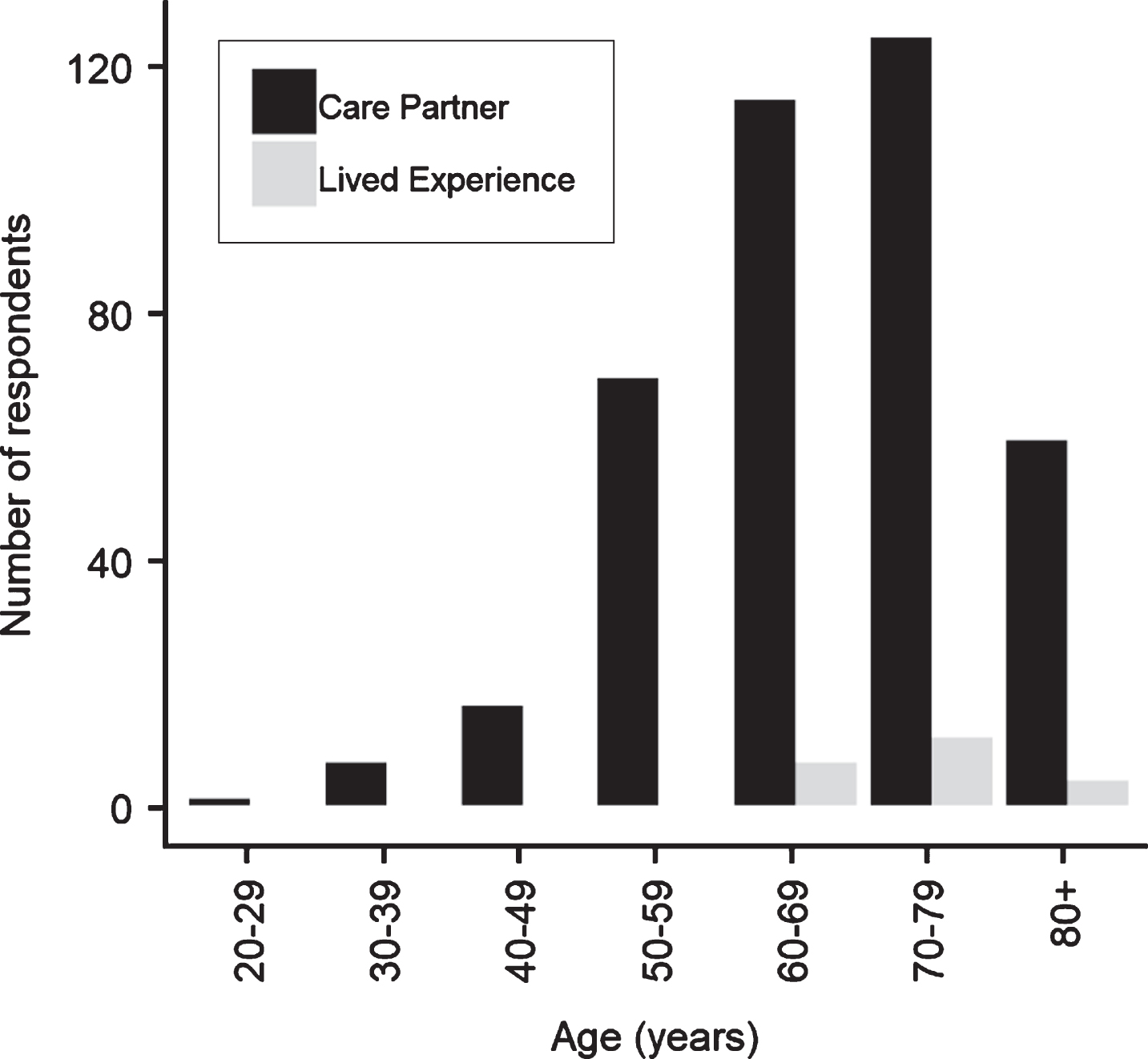

Respondents ranged from their twenties to their eighties, with the largest group in both cohorts (persons with lived experience of dementia and care partners) being those in their seventies (Fig. 1). The care partner sample was primarily female (310 women and 84 men) while the lived experience sample was evenly split between male and female subjects (n = 11 each). The majority of respondents across both groups were White/Caucasian (n = 376), with some respondents identifying as Chinese (n = 15), Indigenous Canadian or Native American (n = 3), and Japanese (n = 3).

Fig.1

Age of survey respondents (when reported).

Information and resource needs

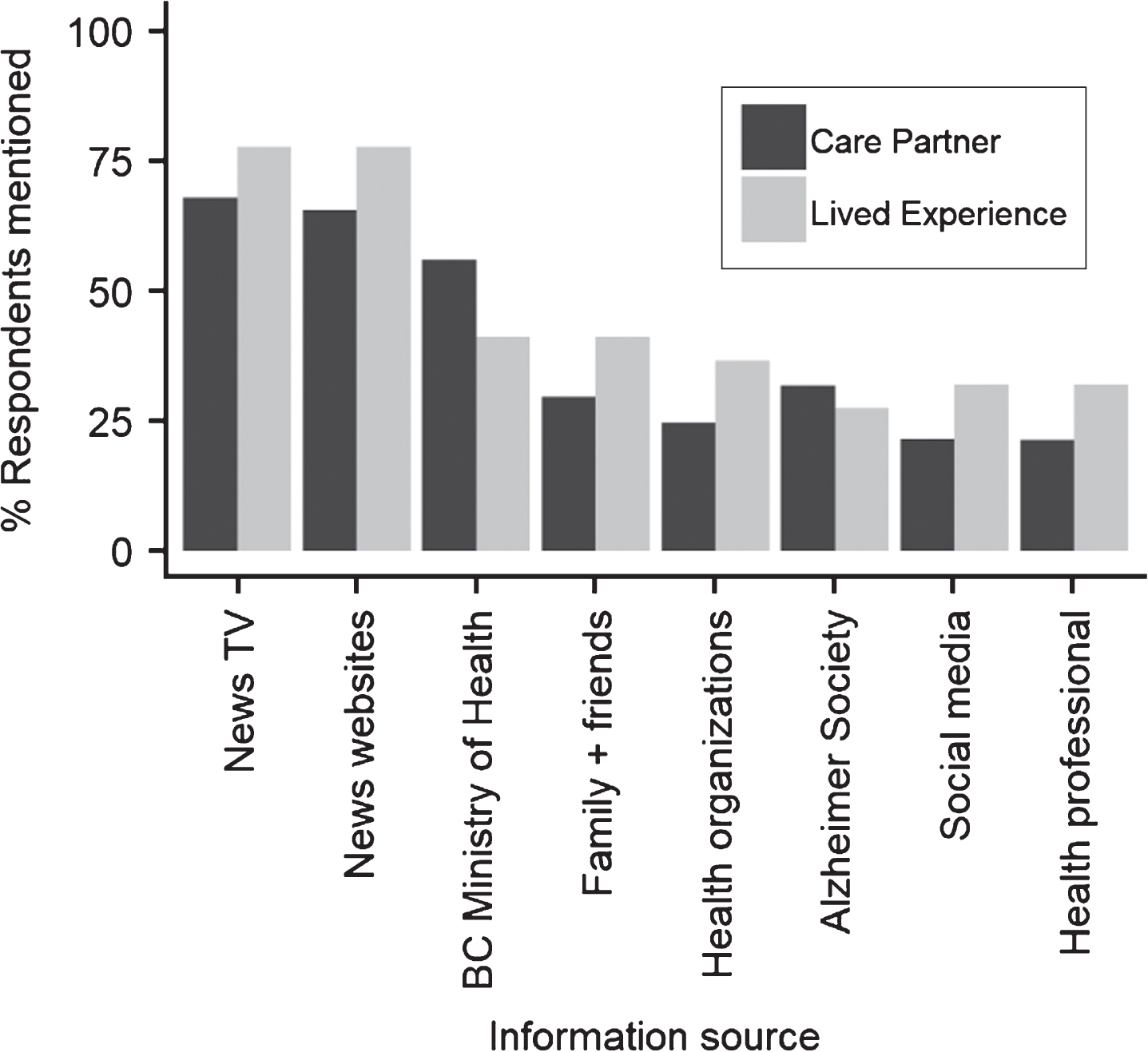

The most common sources of COVID-19 specific information that participants reported using were news on television (68% and 77% of care partner and live experience respondents, respectively), news websites (65%, 77%), the British Columbia Ministry of Health (56%, 41%), family and friends (29%, 41%) (Fig. 2).

Fig.2

Responses to the question “Where have you been getting information about the COVID-19 pandemic?”.

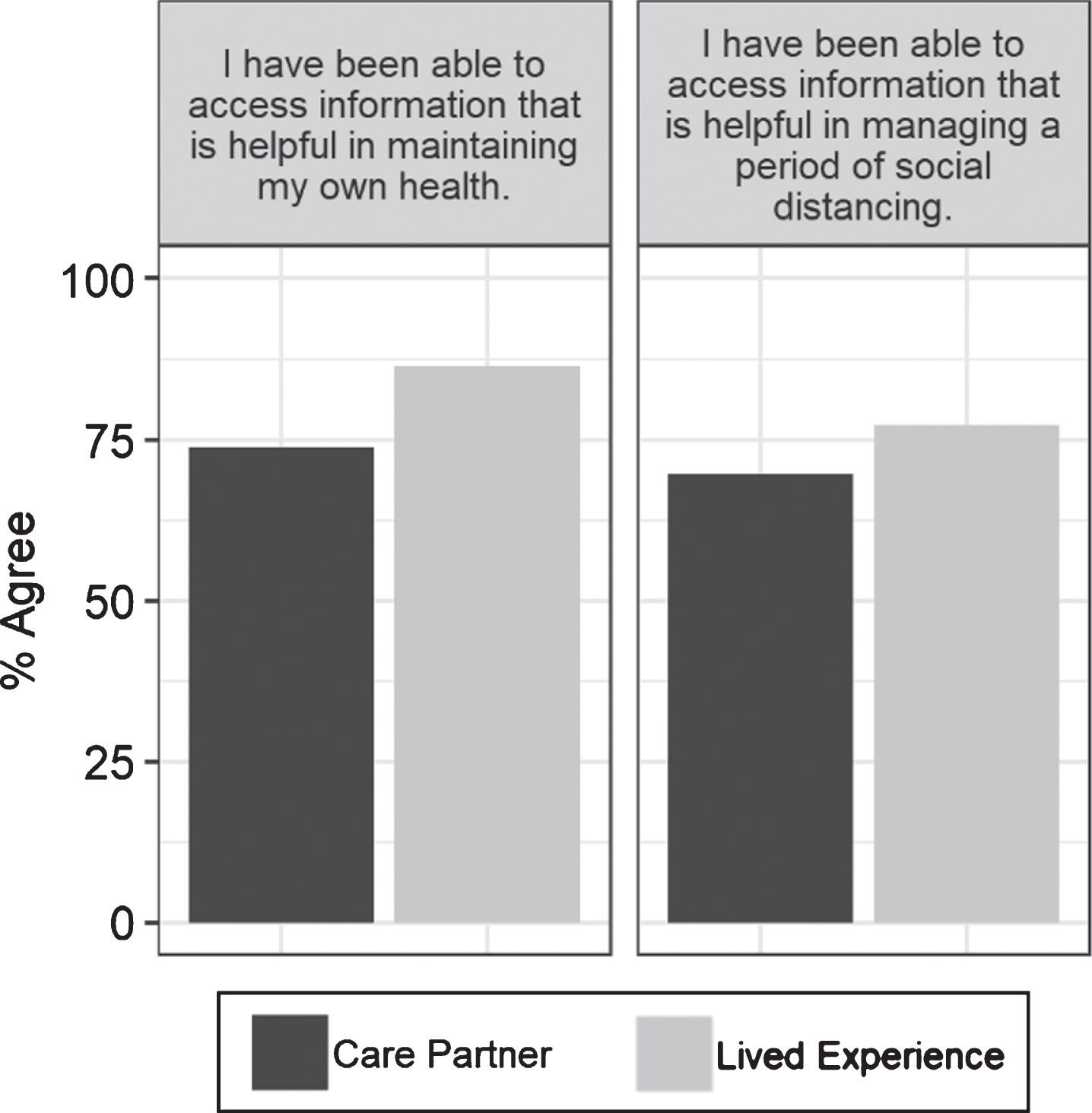

Participants were asked about the relevance of the information that they accessed (Fig. 3). A majority of respondents somewhat agreed, agreed, or strongly agreed that the information that they had been able to access information was helpful to them in maintaining their own health (74% of care partners, 86% of the lived experience group), and that they had been able to access information helpful for maintaining a period of social distancing (70%, 77%). The care partner group was less likely than the lived experience group to agree that they had been able to access information helpful for maintaining a period of social distancing (44% versus 63%). When asked about the impact of pandemic-specific information, respondents indicated that, overall, they found this information somewhat or very stressful (29%, 23%), neither stressful nor reassuring (23%, 23%), or somewhat or very reassuring (48%, 54%).

Fig.3

Percentage of responses that indicated agreement with information access questions.

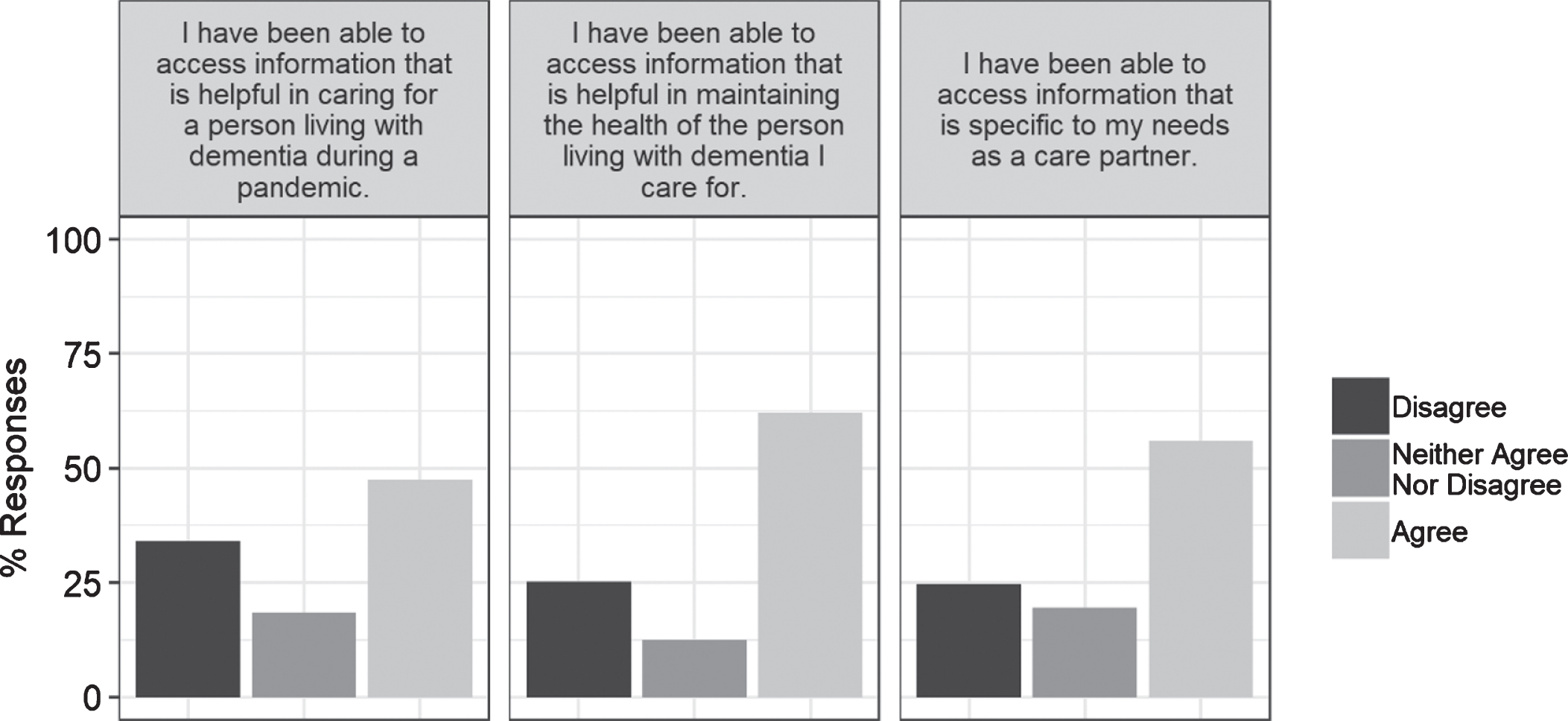

Access to dementia-specific information was important for care partners (Fig. 4). Over half of care partners agreed that they had been able to access information that was helpful in maintaining the health of the person living with dementia that they cared for (62%), that they had been able to access find information specific to their needs as a care partner (56%) and that they had been able to access information that was helpful in doing so during a pandemic (48%).

Fig.4

Responses to items about the helpfulness of information that respondents had accessed.

We also asked participants about additional information that they might like to receive. Care partners prioritized learning about care options including long-term care (37%), respite care (37%), self-care (33%), and home care (32%) The lived experience group expressed most interest in receiving additional information about self-care (50%), followed by care options like long-term care (23%), respite care (18%), and home care (14%). The two most popular formats to receive such information were written format. e.g.. email (77%, 86%) and via online dementia education webinar (29%, 50%).

Concerns around caring for someone living with dementia

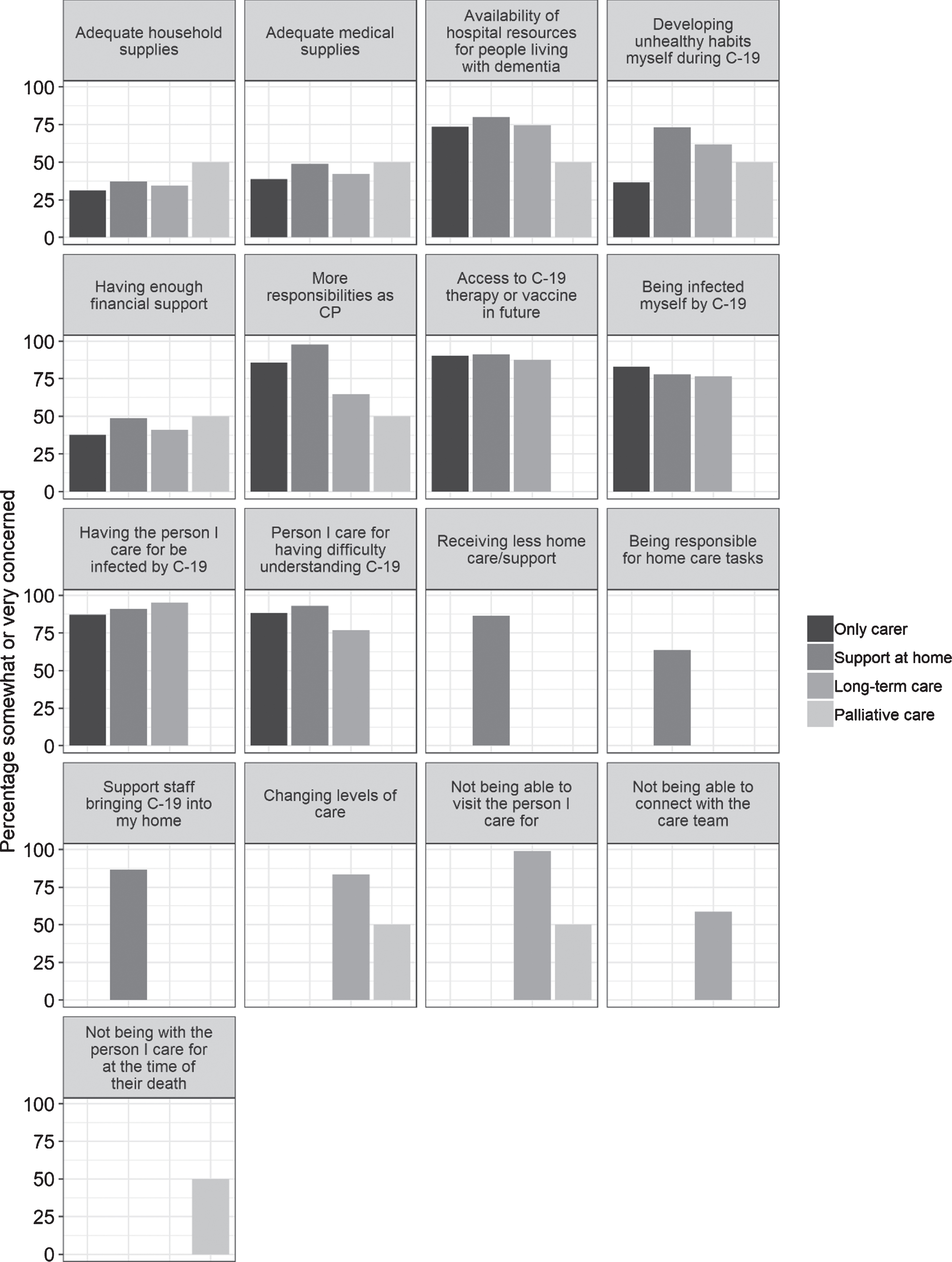

We collected responses from care partners caring for individuals across dementia stages (early stage/managing independently: 9%, middle stage/requiring moderate support: 46%, late stage/dependent on support: 40%). Respondents were engaged in a number of different care arrangements, including being the only carer (46%), receiving support within the home (13%), caring for an individual in long-term care (27%), and caring for someone receiving palliative care (1%; n = 2). These care partners were asked a series of questions in the survey regarding their caregiving-specific concerns during the pandemic. Note that some questions were not posed to all groups (e.g., only those who indicated receiving home care were asked about changing availability of home care).

Across care situations, there were a number of items of high concern (Fig. 5). These included, in order of importance: not being able to visit the person that they care for in long-term or palliative care (98% of all respondents, pooled across relevant groups), the person they cared for being infected with COVID-19 (90%), access to therapy and/or a vaccine for COVID-19 in the future (90%), the possibility that care staff might bring the virus into their homes (87%), reductions in home care support (86%), that the person they care for might have difficulty understanding the virus or social distancing recommendations (85%), changing levels of care available (83%), the possibility of becoming infected themselves (80%), increased responsibilities as a care partner (80%), availability of hospital resources for people living with dementia (75%), being responsible for new home care tasks as a result of the pandemic (64%), not being able to connect with care teams (59%), developing unhealthy habits themselves during COVID-19 (50%), and not being present with the person they care for at the time of their death (one of the n = 2 palliative care partners). Access to physical resources like medical and household supplies and adequate financial support were also concerns for 33–41% of care partners. An additional theme that emerged from respondents’ free-form comments was an inability to take a break from providing care.

Fig.5

Care partner responses about their pandemic-related concerns.

Mental health and well-being needs

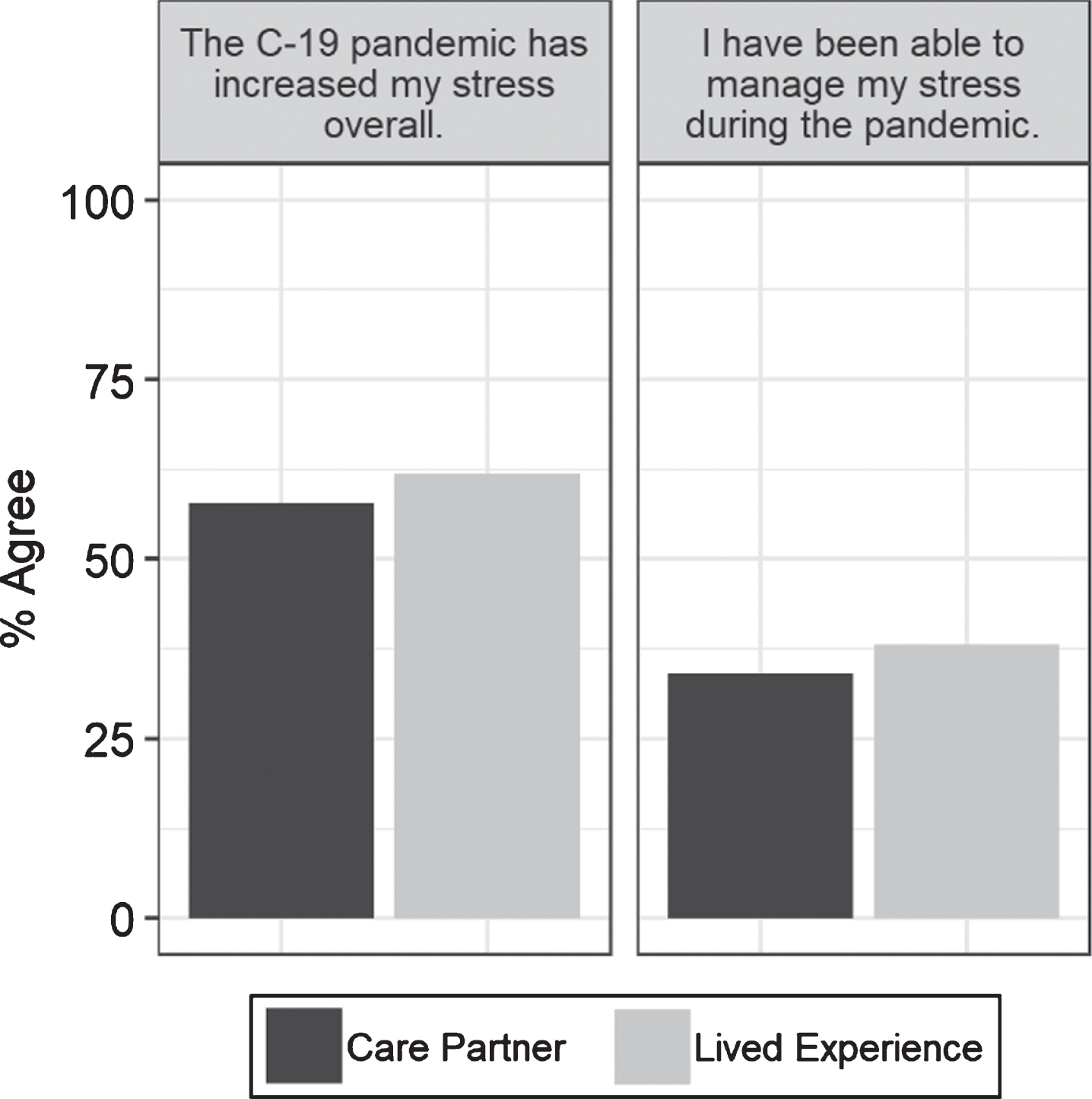

The pandemic and resulting public health recommendations in place had an impact on the participants’ well-being (Fig. 6). The majority of both groups agreed or strongly agreed that the pandemic had increased their stress overall (58%, 62%). Fewer than half felt that they had been able to manage their stress (34%, 38%).

Fig.6

Responses to items about stress and stress management during the pandemic.

Respondents engaged in a number of activities in order to manage their stress and maintain their well-being, including talking to friends and family (84%, 77%), walking around the neighborhood (68%, 86%), watching TV (60%, 59%), engaging in household work (64%, 55%), using the internet (60%, 50%), and exercising (51%, 55%).

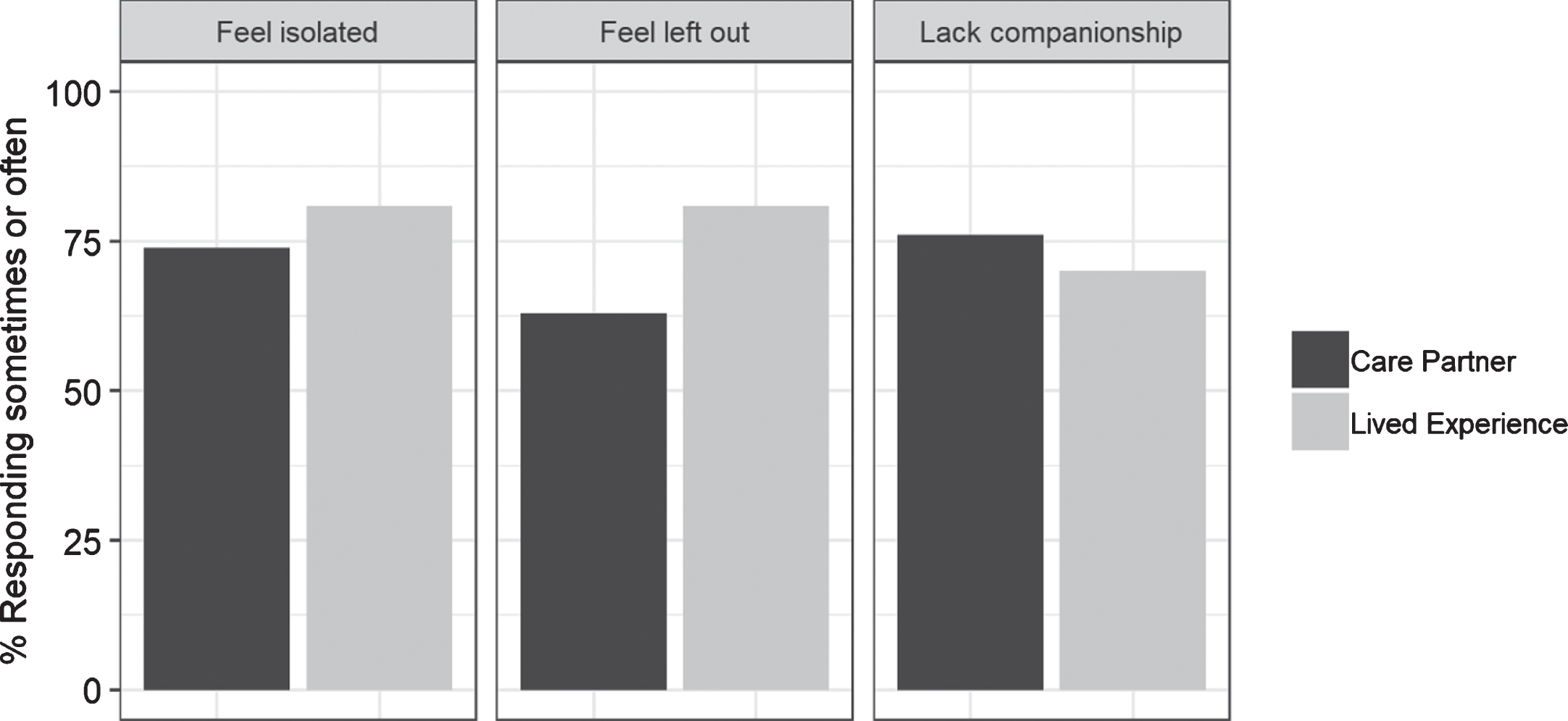

A 3-item short scale on loneliness was adapted from Hughes et al. and included in the survey [22] (Fig. 7). In addition to the stress they were experiencing, the majority of participants reported that some of the time or often they felt isolated (74%, 81%), left out (63%, 81%), and lacking companionship (70%, 76%). When comparing their current level of isolation to their feelings before the COVID-19 pandemic, most reported feeling more isolated or somewhat more isolated (89%, 83%).

Fig.7

Responses to items on the loneliness scale.

Technology and social connection

As a result of social and physical distancing to prevent the spread of the virus, many people had to quickly adapt and transition to a virtual setting for social connection. The majority (86%, 95%) reported that they had been able to socialize and connect with other people during the pandemic. They did so via cell phone or smartphone (66%, 68%), in person (58%, 68%), via devices like laptops and tablets (73%, 59%), and home phones (63%, 55%).

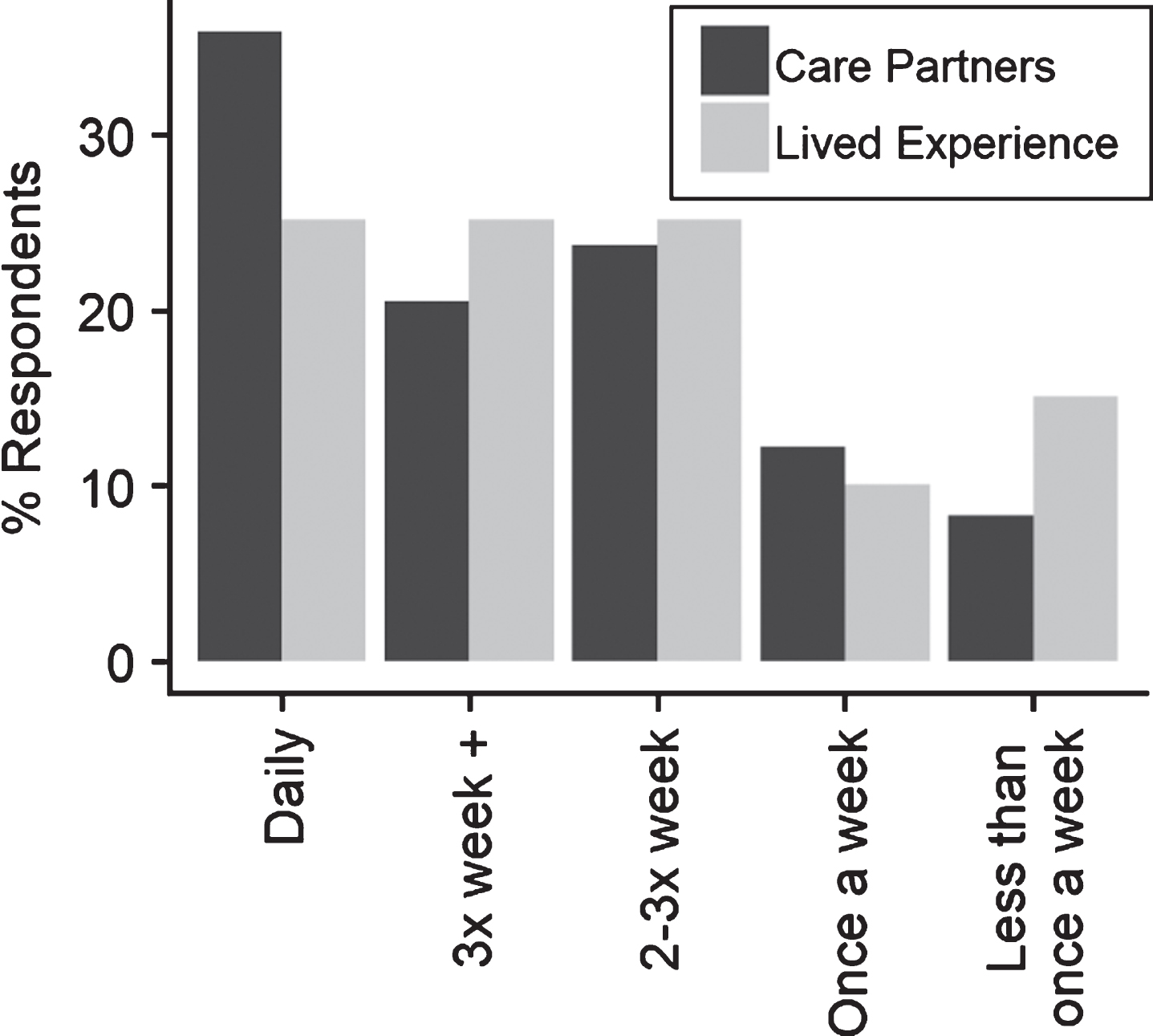

In terms of frequency of social connection, the majority of participants (79%, 75%) reported that such connections occurred at least twice per week (Fig. 8). However, 8% of care partners and 15% of those with lived experiences of dementia reported connecting with others less than once per week.

Fig.8

Frequency of social connection.

In terms of the quality of technology-mediated interactions, 19% of care partners and 36% of the lived experience group reported that using technology to connect with others felt the same as interacting with them in person. However, many reported that they felt comfortable using technology to connect with others (65%, 68%), and many indicated that they were interested in learning more about using technology in this way (32%, 50%).

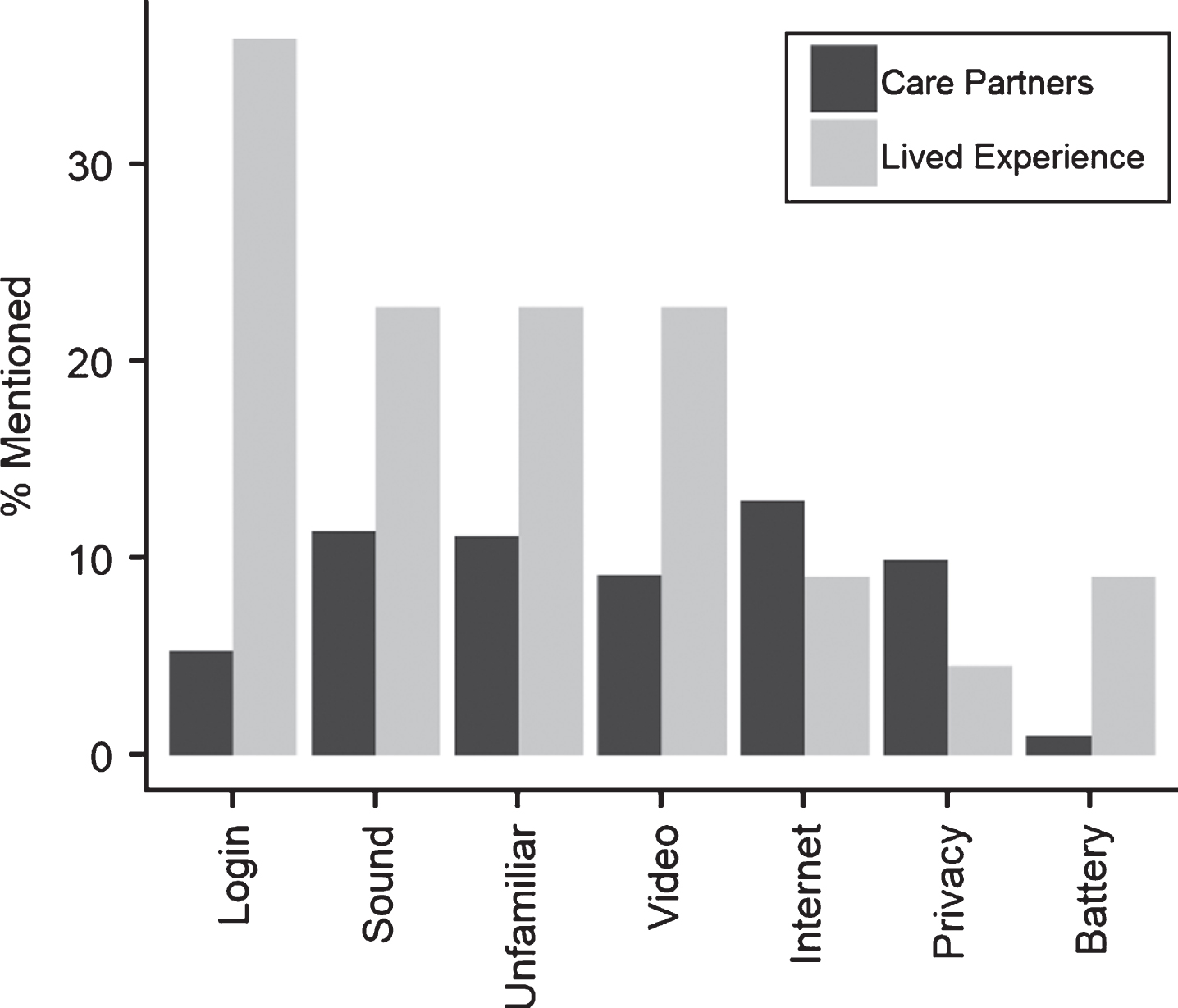

A majority of respondents reported using technology to connect with other during the pandemic without technical issues (58%, 55%). When issues did come up, they included problems logging in (5%, 36%), issues with sound (11%, 23%), not being familiar with how the technology worked (11%, 23%), issues with video (9%, 23%), internet quality (13%, 9%), privacy concerns (10%, 5%), and battery issues (1%, 9%) (Fig. 9).

Fig.9

Technical issues reported by participants.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this provincial survey highlight the impact of the global pandemic on people living with dementia and their families and care partners. This survey outlined several actionable priorities for this population surrounding additional information resources, specific concerns that arise for caregivers during the pandemic, and insight to their mental health and well-being needs with a focus on social connection and isolation during this time.

Respondents looked to a number of sources for information about the COVID-19 virus. While the majority of participants were able to access information about the pandemic, many reported that the information they found was stressful. The need for additional information also differed between the two groups we contacted; care partners wanted more information about care resources while people living with dementia were interested in learning more about self-care. This provides an opportunity to improve the access to quality information around the pandemic and highlights the significance of learning from the perspectives of those with lived experience. In the age of social media and the internet, many people often have access to misinformation that can be simultaneously circulated with information from reliable sources. There has been a rapid increase of misinformation on social media platforms such as Twitter regarding medical details and treatment of the virus [23–26]. By learning where people find their information, it provides better insight into the sources that they may personally deem credible. From this, it is important that high quality, evidence-based information is delivered through the different channels that people are already using. In addition, disseminating information to the dementia community requires efforts from advocacy originations and health care practitioners to tackle existing fake information and support accurate understanding in these populations [25].

We also identified care partners’ main concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. These reports can be instructive for directing healthcare resources. Overall, care partners had a high level of concern across all areas, as many were worried about having to take on new additional tasks in their role. Some reported burnout and needing time to take a break, and for others their main concerns included the ability to visit the person that they care for in long-term or palliative care, and the possibility of people living with dementia being infected with the virus. They furthermore reported a need for attention to be directed towards resource allocation whether it is for a future vaccine, emergency hospital beds and ventilators, or treatment of the virus. The ongoing pandemic has prompted important efforts in examining ethical resource allocation, with a focus on excluding demographic factors such as age in these decisions [27, 28]. Smith et al. emphasize the ethical issues in distributing scarce health resources during a pandemic, arguing that individuals with dementia should be treated under the same frameworks as those with other health conditions [8]. The authors offer principles to consider such as basing decisions for lifesaving resources around individual characteristics, providing people with dementia with the opportunity to express their goals around care, and engaging those with lived experience of dementia in developing protocols for allocation of scarce resources [8]. Applying the ethical value of maximizing benefits in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic should be aimed at saving the most lives and ensuring the improvement of an individuals’ prognosis [7, 8].

Feelings of isolation and a lack of companionship were apparent during a time where social distancing was rigorously enforced. We found that care partners were more stressed and less able to manage their well-being during the pandemic compared to the period beforehand, despite many reporting the use of stress reduction techniques. The presence of social support systems and engaging in social connection are therefore crucial during this time to maintain the mental well-being of people living with dementia and their care partners. While we found that both groups were socially connecting with others using technology, they reported that these connections did not feel the same as they would connecting in person. As technology was widely used as a source of social connection, there is a need to understand the barriers in its utilization. The primary issues reported by our respondents were internet quality, video and audio issues, and difficulty remembering login information. These findings are similar to those of Emanuel et al. who found that there were concerns around internet connections and the limited capabilities of older adults using the technology when engaged in a virtual delivery of care with health care providers [7]. This study did not include the exploration of the specific applications and programs that participants used, which could have contributed of the issues that were reported. However, to participate in this study, all participants successfully accessed and completed the online survey, which likely reflects a certain degree of baseline technical competence. All findings, particularly the result that the majority of participants did not report technical issues when connecting with others, should be interpreted in light of this fact. Identifying and addressing technological barriers for older adults will allow the full potential of social technology to be unlocked for this population for both social connection and access to care resources.

Beyond the purpose of social connection, technology provides actual care in forms of telehealth and other assistive technologies. Telehealth methods have successfully been used for assessments at a distance [29], and assistive technologies have been reported to enhance memory and support self-care [30]. An existing body of literature focuses on the usability of technology and applications for people living with dementia [31–34]. In light of the findings from the survey, a review of this literature as it applies to existing and emerging forms technology can help ensure that these solutions reach the highest standards for ease of use for people living with dementia. We recommend that researchers continuously review existing products for suitability for the dementia community using established frameworks [35–38] and provide guidance for the selection for the given applications and platforms. User-friendly guides on using technology and different applications could be developed to provide guidance on how to select suitable platforms and forms of technology for end-users (see example in Supplementary Figure 1).

With the first case of COVID-19 in British Columbia reported on January 23, 2020, public health measures implemented starting March 12, 2020 [3], and the surveys distributed between June 8, 2020 and August 19, 2020, we acknowledge that the cross-sectional design of this study could be a limitation. During the time between the first reported case and the time the surveys were completed, public measures, news coverage in the media, and the availability of services and resources may have changed which might have an impact on the results and experiences shared by the participants. From this, it would be interesting to compare results at a different time point and observe any changes in needs and concerns over time.

In this study, we learned from the community of people living with dementia, their families and care partners about their different areas of need. There was an interest in additional information about the pandemic specific to their situation, and ways to better support their social interactions and mental well-being. The suggestions given from our participants can inform the ways dementia programs and services implement short-term and long-term changes to better support the community during a challenging time of increased social distancing and feelings of isolation. This reflects the significance of looking at the unintended effects of a global pandemic in order to better manage the care of older adults and people living with dementia at present and in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Alzheimer Society of B.C., our advisory board members Barbara Lindsay, Michele McCabe, Jennifer Stewart, Judy Illes, Mario Gregorio, and Myrna Norman, and research members of the Neuroscience, Engagement, and Smart Technology (NEST) Lab for their support and contributions during the development and piloting of the survey instrument. We are grateful for the rich discussions that took place in the context of the Alzheimer Society of Canada Covid-19 and Dementia Taskforce which helped populate the list of concerns that were covered in the survey instrument. In particular, we wish to thank Drs. Serge Gauthier and John Fisk.

This work was supported by the Alzheimer Society of B.C.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-1114r1).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-201114.

REFERENCES

[1] | World Health Organization, WHO delivers advice and support for older people during COVID-19, https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-delivers-advice-and-support-for-older-people-during-covid-19, Last updated April 3, 2020, Accessed on July 21, 2020. |

[2] | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coronavirus Disease 2019: Older Adults, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/older-adults.html, Last updated August 16, 2020, Accessed on August 16, 2020. |

[3] | BC Centre for Disease Control ((2020) ) COVID-19: Where we are. Considerations for next steps, https://news.gov.bc.ca/files/COVID19_Update_Modelling-BROADCAST.pdf, Last updated on April 17, 2020, Accessed on October 16, 2020. |

[4] | BC Centre for Disease Control, COVID-19: Going Forward, https://news.gov.bc.ca/files/Covid-19_May4_PPP.pdf, Last updated on May 4, 2020, Accessed on October 16, 2020. |

[5] | Infection prevention and control guidance for long-term care facilities in the context of COVID-19: Interim guidance, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331508 Last updated March 21, 2020, Accessed on July 21, 2020. |

[6] | BC Centre for Disease Control, Infection Prevention and Control Requirements for COVID-19 in Long Term Care and Seniors’ Assisted Living, http://www.bccdc.ca/Health-Info-Site/Documents/COVID19_LongTermCareAssistedLiving.pdf, Last updated on June 30, 2020, Accessed on October 16, 2020. |

[7] | Emanuel EJ , Persad G , Upshur R , Thome B , Parker M , Glickman A , Zhang C , Boyle C , Smith M , Phillips JP ((2020) ) Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 382: , 2049–2055. |

[8] | Smith EE , Couillard P , Fisk JD , Ismail Z , Montero-Odasso M , Robillard JM , Vedel I , Sivananthan S , Gauthier S ((2020) ) Pandemic dementia scarce resource allocation. Can Geriatr J 23: , 216–218. |

[9] | Kaiser Health News, Surging Health Care Worker Quarantines Raise Concerns As Coronavirus Spreads, https://khn.org/news/surging-health-care-worker-quarantines-raise-concerns-as-coronavirus-spreads/, Last updated March 9, 2020, Accessed on July 21, 2020. |

[10] | Neurology Today, COVID-19: Prepare for Care-Rationing—Know Your Hospital Policies, https://journals.lww.com/neurotodayonline/blog/breakingnews/pages/post.aspx?PostID=932, Last updated April 8, 2020, Accessed July 21, 2020. |

[11] | Maharani A , Pendleton N , Leroi I ((2019) ) Hearing impairment, loneliness, social isolation, and cognitive function: Longitudinal analysis using English longitudinal study on ageing. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 27: , 1348–1356. |

[12] | Steptoe A , Shankar A , Demakakos P , Wardle J ((2013) ) Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: , 5797–5801. |

[13] | Medium, COVID-19 Pandemic Measures: Ethical Consequences of Barring Families From Hospitals and Long-term Care Centers, https://medium.com/@franco.carnevale/covid-19-pandemic-measures-ethical-consequences-of-barring-families-from-hospitals-and-long-term-951b812e7f49, Last updated April 18, 2020, Accessed on July 23, 2020. |

[14] | Galveston County The Daily News, Texas City COVID-19 patients receive hydroxychloroquine, https://www.galvnews.com/news/free/article_b59bab46-543a-5116-8e37-2f330a8fc008.html, Last updated April 6, 2020, Accessed on July 23, 2020. |

[15] | Boutoleau-Bretonnière C , Pouclet-Courtemanche H , Gillet A , Bernard A , Deruet AL , Gouraud I , Mazoue A , Lamy E , Rocher L , Kapogiannis D , El Haj M ((2020) ) The effects of confinement on neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease during the COVID-19 crisis. J Alzheimers Dis 76: , 41–47. |

[16] | Naughton SX , Raval U , Pasinetti GM ((2020) ) Potential novel role of COVID-19 in Alzheimer’s Disease and preventative mitigation strategies. J Alzheimers Dis 76: , 21–25. |

[17] | Cipriani G , Fiorino MD ((2020) ) Access to care for dementia patients suffering from COVID-19. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28: , 796–797. |

[18] | Brown EE , Kumar S , Rajji TK , Pollock BG , Mulsant BH ((2020) ) Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28: , 712–721. |

[19] | Mair FS , Goldstein P , May C , Angus R , Shiels C , Hibbert D , O’connor J , Boland A , Roberts C , Haycox A , Capewell S ((2005) ) Patient and provider perspectives on home telecare: Preliminary results from a randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare 11: , 95–97. |

[20] | Alzheimer Society Canada, COVID 19 and Dementia Task Force, https://alzheimer.ca/en/Home/Living-with-dementia/managing-through-covid-19/covid-19-and-dementia-task-force, Last updated June 16, 2020, Accessed on July 22, 2020. |

[21] | Wickham H ((2016) ) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, Springer International Publishing. |

[22] | Hughes ME , Waite LJ , Hawkley LC , Cacioppo JT ((2004) ) A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Res Aging 26: , 655–672. |

[23] | Kouzy R , Abi Jaoude J , Kraitem A , El Alam MB , Karam B , Adib E , Zarka J , Traboulsi C , Akl E , Baddour K ((2020) ) Coronavirus goes viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 misinformation epidemic on Twitter. Cureus 12: , e7255. |

[24] | Limaye RJ , Sauer M , Ali J , Bernstein J , Wahl B , Barnhill A , Labrique A ((2020) ) Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit Health 2: , e277–e278. |

[25] | O’Connor C , Murphy M ((2020) ) Going viral: Doctors must tackle fake news in the covid-19 pandemic. Br Med J 369: , m1587. |

[26] | Rosenberg H , Syed S , Rezaie S ((2020) ) The Twitter pandemic: The critical role of Twitter in the dissemination of medical information and misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. CJEM 22: , 418–421. |

[27] | Farrell TW , Ferrante LE , Brown T , Francis L , Widera E , Rhodes R , Rosen T , Hwang U , Witt LJ , Thothala N , Liu SW , Vitale CA , Braun UK , Stephens C , Saliba D ((2020) ) AGS position statement: Resource allocation strategies and age-related considerations in the COVID-19 era and beyond. J Am Geriatr Soc 68: , 1136–1142. |

[28] | Laventhal N , Basak R , Dell ML , Diekema D , Elster N , Geis G , Mercurio M , Opel D , Shalowitz D , Statter M , Macauley R ((2020) ) The Ethics of creating a resource allocation strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 146: , e20201243. |

[29] | Loh PK , Ramesh P , Maher S , Saligari J , Flicker L , Goldswain P ((2004) ) Can patients with dementia be assessed at a distance? The use of Telehealth and standardised assessments: Telehealth dementia assessment. Intern Med J 34: , 239–242. |

[30] | Lorenz K , Freddolino PP , Comas-Herrera A , Knapp M , Damant J ((2019) ) Technology-based tools and services for people with dementia and carers: Mapping technology onto the dementia care pathway. Dementia 18: , 725–741. |

[31] | Asghar I , Cang S , Yu H ((2018) ) Usability evaluation of assistive technologies through qualitative research focusing on people with mild dementia. Comput Human Behav 79: , 192–201. |

[32] | Holthe T , Halvorsrud L , Karterud D , Hoel K-A , Lund A ((2018) ) Usability and acceptability of technology for community-dwelling older adults with mild cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic literature review. Clin Interv Aging 13: , 863–886. |

[33] | Czaja SJ , Rubert MP ((2002) ) Telecommunications technology as an aid to family caregivers of persons with dementia. Psychosom Med 64: , 469–476. |

[34] | Nygård L , Starkhammar S ((2007) ) The use of everyday technology by people with dementia living alone: Mapping out the difficulties. Aging Ment Health 11: , 144–155. |

[35] | Robillard JM , Cleland I , Hoey J , Nugent C ((2018) ) Ethical adoption: A new imperative in the development of technology for dementia. Alzheimers Dement 14: , 1104–1113. |

[36] | Alm N , Dye R , Gowans G ((2003) ) Designing an interface usable by people with dementia. In Proceedings of the 2003 Conference on Universal Usability, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, pp. 156–157. |

[37] | Meiland F , Innes A , Mountain G , Robinson L , van der Roest H , García-Casal JA , Gove D , Thyrian JR , Evans S , Dröes R-M , Kelly F , Kurz A , Casey D , Szcześniak D , Dening T , Craven MP , Span M , Felzmann H , Tsolaki M , Franco-Martin M ((2017) ) Technologies to support community-dwelling persons with dementia: A position paper on issues regarding development, usability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, deployment, and ethics. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 4: , e1. |

[38] | Astell A , Alm N , Gowans G , Ellis M , Vaughan P , Dye R , Campbell J ((2009) ) Working with people with dementia to develop technology: The CIRCA and living in the moments projects. J Dement Care 17: , 36–39. |