Oral Health Status in Subjects with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: Data from the Zabút Aging Project

Abstract

Background:

The relationship between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and periodontitis has been recently investigated with heterogenous results.

Objective:

This study aims to evaluate the oral health status and its relationship with cognitive impairment of participants, enrolled in the Zabút Aging Project, a community-based cohort study performed in a rural community in Sicily, Italy.

Methods:

A case-control study (20 subjects with AD, 20 with amnestic mild cognitive impairment [aMCI], and 20 controls) was conducted. The protocol included a comprehensive medical and cognitive-behavioral examination. Full-mouth evaluation, microbial analysis of subgingival plaque samples (by RT-PCR analysis), and oral health-related quality of life (OHR-QoL) were evaluated.

Results:

The decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) total score of AD subjects was significantly higher than aMCI (p = 0.009) and controls (p = 0.001). Furthermore, the “M” component of DMFT (i.e., the number of missing teeth) was significantly higher in AD than in aMCI (p < 0.001) and controls (p < 0.001). A Poisson regression model revealed that age (p < 0.001), male gender (p = 0.001), and AD (p = 0.001) were positively correlated with DMFT. Concerning oral microbial load, the presence of Fusobacterium nucleatum was significantly higher in AD than in controls (p = 0.02), and a higher load of Treponema denticola was found in aMCI than with AD (p = 0.004). OHR-QoL scores did not differ among the groups.

Conclusion:

The current research suggests that AD is associated with chronic periodontitis, which is capable of determining tooth loss due to the pathogenicity of Fusobacterium nucleatum. These data remain to be confirmed in larger population-based cohorts.

INTRODUCTION

The improvement in general health, observed in recent decades, has promoted life expectancy at birth of the world’s population. According to previsions, the percentage of people over 65 years of age will increase from 12% to 22% in developed countries [1, 2]. Since elderly populations are rising, the incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment has become a public health challenge.

Dementia is a common and disabling disorder; the World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 47.5 million people worldwide in 2015 suffered from dementia [1]; in Italy there are more than 1 million individuals affected by dementia [3]. Dementia is the main cause of cognitive impairment in the elderly, and it is usually associated with memory loss, judgment impairment, changes in personality, mood, and behavior, all of which lead to difficulty in performing day-to-day activities and familiar tasks. The major cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder accounting for 60–70% of all dementias [3, 4]. The disease is mostly sporadic (>95% of all cases) and results from the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. Its prevalence spreads with age, increasing from 3% in subjects aged 65 years or over, doubling every 5 years after 65 years [3–5].

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a clinical syndrome considered a prodromal phase of AD [6]. Subjects with MCI are not functionally impaired in everyday activities but they develop difficulty with memory, language, or other cognitive functions, and frequently show behavioral abnormalities [7, 8]. MCI with positive AD biomarkers [9], the so-called MCI due to AD, frequently show a prominent memory impairment. The latter is defined as amnestic MCI (aMCI), and it usually progresses to overt AD dementia [7].

A possible relationship between AD and oral health has been widely investigated, and many conditions related to poor oral health have been proposed as risk factors for the development of AD [10–13]. Subjects with MCI and AD have also been found to have a higher risk of developing severe periodontitis, tooth loss with impaired chewing capability [14–17]. Periodontitis is a local, chronic inflammatory disease with potential systemic effects [18], and, with dental caries, it is a major cause of tooth loss especially in elderly subjects [19–21].

Chronic periodontitis is associated with elevated blood levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, which may induce a low-grade, persistent, systemic inflammation, thus stimulating the peripheral nerves [11, 22–24]. Additionally, periodontal bacteria, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema forsythia, and Treponema denticola, may penetrate the bloodstream and infect organs directly or generate inflammatory reactions [5, 25, 26].

The aim of this study was to investigate the oral health status of subjects with aMCI and AD, drawn from a population-based cohort study, which had been conducted in rural subjects from southern Italy. The specific aims of the study were to: 1) evaluate dental status and characteristics in subjects with aMCI and AD compared to controls; 2) evaluate periodontal status and oral microbial load in aMCI and AD in comparison to controls; 3) determine oral health-related quality of life (OHR-QoL) among the three study groups; and 4) identify the relationships between cognitive impairment and poor oral health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject recruitment

A case-control study including 60 subjects (20 AD, 20 aMCI, and 20 cognitively normal individuals without cognitive and functional impairment [CONS]), sharing similar demographic characteristics, has been conducted. Participants were recruited during the 10-year follow-up of the Zabút Aging Project (ZAP), a population-based cohort study conducted in a rural community with a low educational level in the province of Agrigento (Sicily, Italy).

All subjects were examined in accordance with a comprehensive standardized protocol, including: physical, neurological, and psychiatric examinations; past and present comorbidities and medication. Finally, a comprehensive neuropsychological battery, including tests of global cognition, in addition to tasks evaluating specific cognitive domains (i.e., memory, language, attentive/visuo-constructional abilities, and executive functioning) were administered to all participants by psychologists trained in neuropsychology [27].

The diagnosis of dementia was ascertained by specialists according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria [28] and probable AD was diagnosed according to the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association criteria [29]. aMCI was defined according to modified Petersen’s criteria [6]. Global cognition was assessed with the Italian version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (age-, gender-, and education-adjusted cut-off points) [30]. Functional status was evaluated with the basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL and IADL) tools [31, 32]. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D), which is a short self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in the general population [33].

In order to exclude vascular cognitive impairment, subjects with aMCI and AD also underwent a routine 1.5T MRI scan (Signa HDxt; GE Medical System, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The MRI protocol employed included the following sequences: sagittal and axial T2w Fast Recovery Fast Spin Echo, axial and coronal T2w FLAIR, axial T1w FSE, axial T2*w Gradient Echo, and axial Echo-Planar Diffusion-Weighted Imaging. The axial plane for these analyses was parallel to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line, the coronal plane was parallel to the brainstem, and the sagittal plane was parallel to the interhemispheric fissure. MRI images were evaluated by an experienced neuro-radiologist, who was blind to the clinical diagnoses.

Lifestyles, vascular comorbidity, and biochemical/genetic parameters

Data regarding smoking and alcohol drinking were obtained by questioning the subjects or caregivers (in the case of a cognitively impaired or demented subject). For the current analyses, subjects were dichotomized into current smokers (subject smoking at least five cigarettes daily during the last 5 years) versus never/former smokers (subjects who had never smoked or had smoked and stopped at least 5 years prior to observation). Alcohol drinking was classified into two categories: never/infrequent drinkers (persons who never drink or who drank alcohol less than once a week) versus frequent drinkers (persons who drink alcohol at least once a week).

The following vascular comorbidities were assessed, as previously described [34]:

– obesity was evaluated using body mass index (BMI, with values ≥30 kg/m2). BMI was also used as a continuous variable and was considered as an indirect indicator of malnutrition in the elderly [35];

– hypertension (current use of antihypertensive medications or blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg);

– dyslipidemia [fasting Total Cholesterol (TC) ≥240 mg/dL and/or triglycerides (TG) ≥150 mg/dL, and/or HDL < 40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women, and/or LDL ≥160 mg/dL];

– diabetes mellitus (current use of hypoglycemic drugs and/or fasting blood glucose levels ≥110 mg/dL);

– atrial fibrillation and ischemic heart disease (angina, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, or angioplasty or stenting), as supported by clinical and/or instrumental records.

A venous blood sampling was obtained in the morning after an overnight fast to establish biochemical and genetic parameters. High sensitivity C-reactive protein was measured by a chemiluminescent immunoassay (Immulite, Medical Systems, Italy), used as an indicator of systemic inflammation. The apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype was determined from blood leukocytes. DNA was extracted by a standardized method, and APOE genotypes were analyzed by a polymerase chain reaction, as previously described [36]. All analyses were conducted comparing E4-carrying (E2/E4, E3/E4, E4/E4) versus non-E4 carrying genotypes.

The study agreed with the principles outlined in the Helsinki declaration, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their caregiver after the procedures had been fully explained. The ethical committee ASP-1 (“Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale”, i.e., provincial health authority) of Agrigento, Italy approved the ZAP protocol. Furthermore, general authorization relating to the genetic data treatment was provided by the Italian Data Protection Authority (code: 0000-0326-7509-4804).

Assessment of dental status and bacterial load

All participants (n = 60) underwent a complete assessment of oral health status. Oral examinations were performed at the patients’ home by a trained oral professional using mirrors, a dental probe, and intra-oral light. The findings were recorded on a standardized screening sheet. The initial data collection regarded an evaluation of dental status according to the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index [37]. The latter index is applied to the permanent dentition, being expressed as the total number of teeth which are decayed (D), missing (M), or filled (F); scores per individual can range from 0 to 28 or 32, depending on whether the third molars are included in the scoring (i.e., higher score are related to poorer oral status). The Community Periodontal Index (CPI) and the Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR) were used [37, 38] to assess the periodontal status of the enrolled subjects, following the recommendation of WHO for community-based screening programs. The two indices use a common evaluation method, based on the following three periodontal disease indicators: gingival bleeding on probing (BoP) calculus accumulation; and probing depth. Additionally, the PSR Index provides a more detailed picture of periodontal status by recording the presence of furcation involvement, tooth mobility, muco-gingival problems, and gingival recessions exceeding 3.5 mm. The data were collected and scored by dividing the mouth into six sextants, and each tooth into six different sites: mesiobuccal, midbuccal, distobuccal; and the corresponding lingual or palatal sites. Each tooth was scored from Code 0 to Code 4 but only the highest score of the sextant was recorded. Overall, the following oral parameters (i.e., bleeding or BoP, tooth mobility, orofacial pain, dental abscess, halitosis, and calculus) were collected (presence versus absence).

Thereafter, all subjects underwent a sampling of the sub-gingival plaque bacterial load (using a Carpegen® Perio Diagnostics kit with paper cones on gingival crevicular fluid) in order to perform an RT-PCR analysis for the quantitative determination of six marker organisms of periodontitis: Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A.a), Fusobacterium nucleatum (F.n.), Porphyromonas gingivalis (P.g.), Prevotella intermedia (P.i.), Treponema denticola (T.d.), and Tannerella forsythia (T.f.).

Finally, the OHR-QoL was evaluated using the Short Form Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) [39], a self-filled questionnaire useful to assess the impact of chronic oral problems on the patients’ everyday life. The OHIP-14 includes 14 items and 7 subscales regarding the following dimensions: functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability, and handicap. The oral health ZAP sub-study received specific approval from the ethical committee of the University Hospital “P. Giaccone” of Palermo, Italy.

Statistical analysis

The data were tabulated and analyzed according to means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions. Data with normal distribution were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and analyzed with the t-test or one-way ANOVA; non-parametric tests (e.g., Kruskall-Wallis) were also used. Dunn’s post-hoc test was applied to test pairwise multiple comparisons. This correction generates the adjusted p-value which compensates for a p-value increase by testing each hypothesis at a significance level of alpha over the number of hypotheses. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to test marginal associations between qualitative variables. A Poisson regression model was applied to model the DMFT total score related to demographic, clinical, biochemical/genetic, and dental characteristics among the three studied groups. A backward stepwise selection process with a lowering of the Akaike information criterion (AIC) for model selection was used. The data were analyzed using R software (version 3.5.1); a p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical features, comorbidity, and biochemical/genetic parameters

The demographic, clinical, biochemical, and genetic characteristics for CONS, aMCI, and AD are shown in Table 1. Overall, 55% of participants were female and the mean age of the subjects was 80±8.68 years, without any significant differences between the groups, although AD subjects were slightly older than aMCI and CONS. The overall sample had a mean year of educational level of 4.81±3.01, without significant difference between the groups. Clinically, the subjects with AD had a significantly longer disease duration than aMCI (p < 0.01). One-way ANOVA revealed a significant ADL and IADL effect between groups (p < 0.01 for both comparisons). After Dunn’s post hoc comparison, participants with AD reported a statistically higher number of ADL lost than aMCI and CONS (adjusted p < 0.001 for both comparisons), while the latter did not differ from the former. Similarly, AD showed a significantly higher number of IADL lost than aMCI and CONS (adjusted p < 0.001 for both comparisons), without any difference between the former and the latter. As expected, ANOVA showed a significant MMSE effect between groups (p < 0.01). After post-hoc analysis, AD showed a significantly lower MMSE score than aMCI and CONS (adjusted p < 0.001 for both comparisons), with the former performing worse than the latter (adjusted p < 0.001). Finally, no differences regarding depressive symptoms among the groups were observed. Concerning lifestyles and comorbidity, smoking habits and alcohol consumption did not significantly differ between groups and nor did vascular/metabolic comorbidities in the study groups. The results of biochemical and genetic parameters did not differ across the groups although the APOE4 allele was slightly more frequent in the AD group.

Table 1

Demographic, clinical, biochemical, and genetic characteristics of controls (CONS), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)*

| CONS n = 20 | aMCI n = 20 | AD n = 20 | p | Post-hoc | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y | 78.8±8.1 | 78.0±9.5 | 83.5±7.7 | 0.09 | n.s. |

| Education, y | 5.5±2.8 | 4.7±3.9 | 4.3±2.0 | 0.11 | n.s. |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (60) | 9 (45) | 12 (60) | 0.54 | n.s. |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Disease duration, y | n.a. | 1.75±0.85 | 5.05±3.36 | <0.01 | AD>aMCI |

| ADL lost | 0.25±0.44 | 0.45±0.51 | 2.7±2.15 | <0.01 | AD>CONS, AD > aMCI |

| IADL lost | 0.45±0.75 | 1.15±0.87 | 5.15±1.78 | <0.01 | AD>CONS, AD > aMCI |

| MMSE | 26.71±1.28 | 24.26±1.45 | 16.03±6.49 | <0.01 | AD<aMCI<CONS |

| CES-D | 13.3±9.38 | 16.75±9.01 | 17.3±9.17 | 0.33 | n.s. |

| Lifestyles and Comorbidity | |||||

| Alcohol, n (%) | 3 (15) | 4 (20) | 3 (15) | 1 | n.s. |

| Smoking, n (%) | 4 (20) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.15 | n.s. |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 12 (60) | 13 (65) | 15 (75) | 0.59 | n.s. |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 7 (35) | 5 (25) | 6 (30) | 0.78 | n.s. |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (20) | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 1 | n.s. |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 0.86 | n.s. |

| IHD, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (30) | 2 (1) | 0.02 | - |

| Obesity, n (%) | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 4 (20) | 0.74 | n.s. |

| BMI | 27±2.69 | 27.50±4.00 | 26.35±5.07 | 0.66 | n.s. |

| Biochemical and Genetic parameters | |||||

| hs-CRP mg/L | 0.30±0.24 | 0.55±0.77 | 0.45±0.47 | 0.92 | n.s. |

| APOE4 allele, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 0.48 | n.s. |

*Except were specified data are expressed as mean±SD. ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression scale; IHD, ischemic heart disease; BMI, body mass index; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; APOE4, Apolipoprotein E, ɛ4 allele; n.s., not significant.

Dental status, periodontal condition, oral bacterial load, and OHR-QoL

Table 2 shows DMFT scores and dental characteristics of CONS, aMCI, and AD. ANOVA revealed significant differences among the means of the DMFT total score in the three groups (p = 0.01). After post-hoc analysis patients with AD displayed a significantly higher DMFT total score than aMCI (adjusted p = 0.009) and CONS (adjusted p = 0.001), while the latter two groups did not significantly differ from each other. As a specific sub-item of the DMFT score, the “M” component (representing the number of missing teeth) significantly differed among the groups after ANOVA (p < 0.001). The AD group showed higher “M” values at pair comparison than the aMCI (adjusted p < 0.001) and CONS (adjusted p < 0.001), with no differences between aMCI and CONS. However, no significant differences were observed for the other components of the DMFT score (i.e., D and F, which assess decayed and filled teeth respectively) and other oral parameters (i.e., bleeding or BoP, tooth mobility, orofacial pain, dental abscess, halitosis, and calculus).

Table 2

DMFT scores and dental characteristics of controls (CONS), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)*

| Index | CONS n = 20 | aMCI n = 20 | AD n = 20 | p | Post-hoc |

| DMFT total score | 19.7±5.88 | 21±6.45 | 25.85±7.25 | 0.01 | AD>CONS, AD > aMCI |

| D | 2.6±2.01 | 2.1±1.58 | 2.3±1.21 | 0.62 | |

| M | 14.7±5.75 | 15.55±6.96 | 22.05±7.09 | <0.001 | AD>CONS, AD > aMCI |

| F | 2.4±1.95 | 3.35±3.06 | 1.4±1.63 | 0.05 | n.s. |

| DMFT by gender | |||||

| Men | 23.25±4.97 | 21.54±6.28 | 27.5±4.20 | 0.07 | n.s. |

| Women | 17.33±5.36 | 20.33±6.98 | 24.75±8.73 | 0.05 | n.s. |

| Dental characteristics, n (%) | |||||

| BoP (Yes versus No) | 12 (60) | 14 (70) | 8 (40) | 0.11 | n.s. |

| Tooth mobility (Yes versus No) | 9 (45) | 10 (50) | 5 (25) | 0.25 | n.s. |

| Orofacial pain (Yes versus No) | 5 (25) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 0.57 | n.s. |

| Dental abscess (Yes versus No) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.31 | n.s. |

| Halitosis (Yes versus No) | 7 (35) | 8 (40) | 3 (15) | 0.20 | n.s. |

| Calculus (Yes versus No) | 15 (75) | 13 (65) | 9 (45) | 0.18 | n.s. |

*Except were specified data are expressed as mean±SD. DMFT, decaying (D), missing (M) and filled (F) teeth index; BoP, bleeding on probing; n.s., not significant.

The periodontal indexes and oral microbial load data are shown in Table 3. The scores of the CPI and PSR indexes did not statistically differ among the groups. There were no statistically significant differences with the total oral microbial load of the three groups although groups differed when comparing specific bacterial loads, thereby revealing significant intergroup differences for F.n. and T.d. Specifically, one-way ANOVA revealed that F.n. load significantly differed between the groups (p = 0.04), and a post-hoc analysis revealed a higher F.n. load in AD than CONS (adjusted p = 0.02). However, the T.d. load differed significantly between the groups after ANOVA (p = 0.01), with a post-hoc analysis revealing a higher T.d. load in aMCI than AD (adjusted p = 0.004. There were no statistically significant differences in all the OHIP-14 domains among the three groups (see Table 4).

Table 3

Periodontal indexes and oral microbial load of controls (CONS), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)*

| Index | CONS n = 20 | aMCI n = 20 | AD n = 20 | p | Post-hoc |

| CPI score | 2.25±1.01 | 2.3±0.86 | 2.1±1.02 | 0.89 | n.s. |

| PSR score | 2.45±0.94 | 2.3±0.86 | 2.3±1.03 | 0.91 | n.s. |

| Periokit | |||||

| A.a. | 650.0±1,436.55 | 9,525.0±18,494.15 | 3,840.0±11,648.96 | 0.39 | n.s. |

| F.n. | 112,893.5±337,665.3 | 98,525.0±224,955.9 | 303,898.5±602,829.7 | 0.04 | AD>CONS |

| P.g. | 651,770.0±2,167,330.0 | 329,770.0±1,360,371.0 | 767,551.0±3,117,436.0 | 0.57 | n.s. |

| P.i. | 88,075.0±174,243.6 | 73,410.0±140,511.9 | 12,405.0±36,071.0 | 0.12 | n.s. |

| T.d. | 297,343.5±760,184.7 | 336,138.5±792,205.6 | 55,678.5±189,176.7 | 0.01 | aMCI>AD |

| T.f. | 421,665.0±629,904.8 | 619,805.0±1,233,501.0 | 775,950.0±1,281,404.0 | 0.45 | n.s. |

| Total bacterial load | 33,213,500.0±47,987,316.0 | 32,584,500.0±50,686,251.0 | 57,945,000.0±103,570,760.0 | 0.36 | n.s. |

*Data are expressed as mean±SD. CPI, community periodontal index; PSR, Periodontal Screening and Recording; A.a., Aggregati bacter Actinomycetemcomitans; F.n., Fusobacterium Nucleatum; P.g., Porphyromonas Gingivalis; P.i., Prevotella intermedia; T.d., Treponema denticola; T.f., Tannerella forsythia; n.s., not significant.

Table 4

OHIP-14 domains for the controls (CONS), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)*

| OHIP-14 domains | CONS n = 20 | aMCI n = 20 | AD n = 20 | p |

| 1. Functional limitation (items 1–2) | 1.45±1.87 | 1.30±1.94 | 1.90±2.40 | 0.82 |

| 2. Physical pain (items 3–4) | 2.35±2.81 | 1.95±1.73 | 1.65±2.10 | 0.69 |

| 3. Psychological discomfort (items 5–6) | 2.1±2.65 | 1.15±1.66 | 1.20±1.96 | 0.43 |

| 4. Physical disability (items 7–8) | 1.45±1.73 | 1.05±1.66 | 1.30±1.52 | 0.56 |

| 5. Psychological disability (items 9–10) | 1.80±2.19 | 0.85±1.31 | 0.95±1.35 | 0.34 |

| 6. Social disability (items 11–12) | 1.35±1.63 | 0.55±0.99 | 0.45±1.05 | 0.08 |

| 7. Handicap (items 13–14) | 1.45±2.03 | 0.75±1.33 | 0.55±1.09 | 0.14 |

*Data are expressed as mean±SD. OHIP, Oral Health Impact Profile.

Relationships between cognitive impairment and poor-oral health

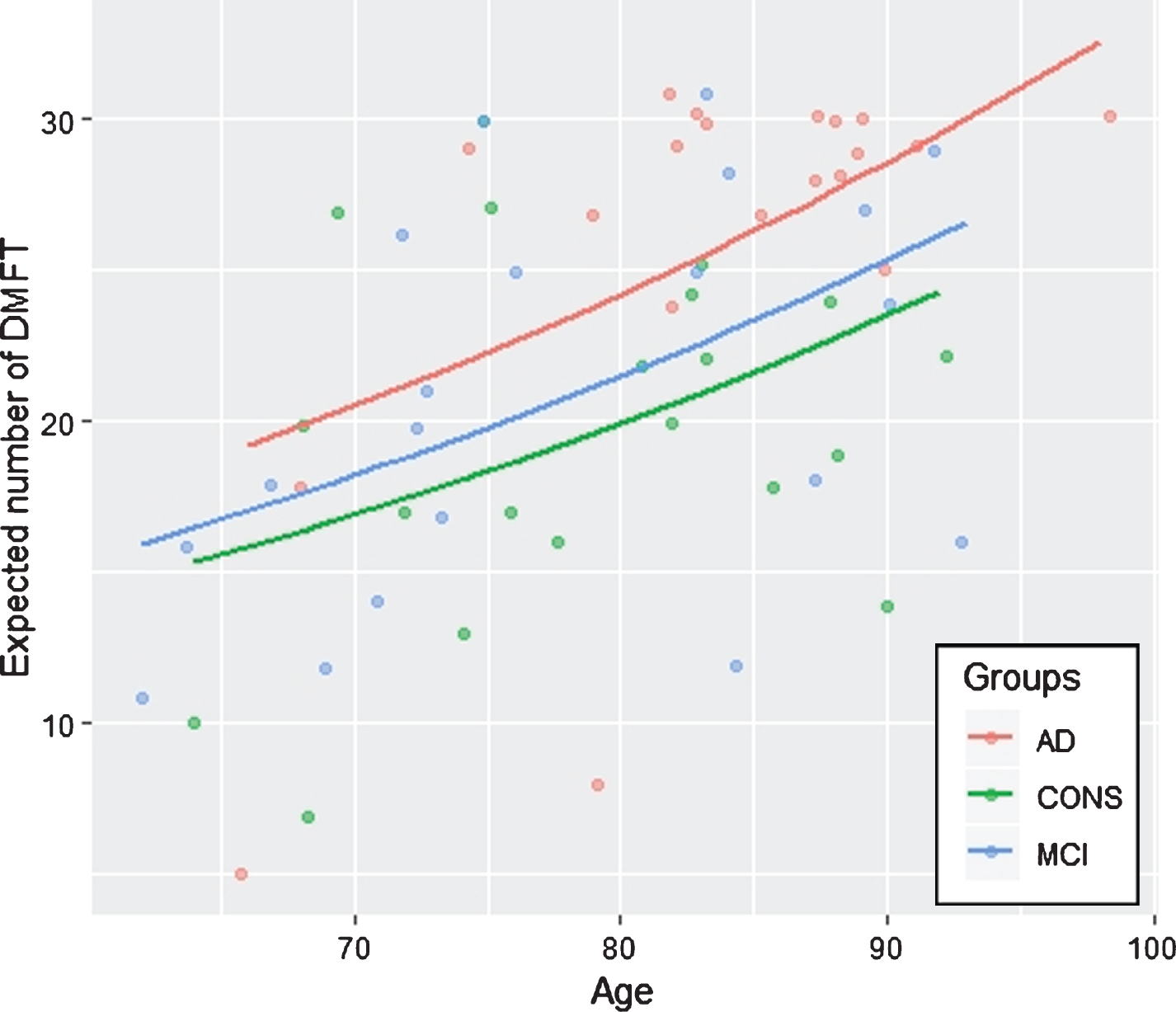

Table 5 shows the estimated regression coefficients, standard errors and p-values for the Poisson regression model, where the covariates were selected through the stepwise AIC procedure. The selected model comprised the following covariates: sex, age, group (AD or MCI), ADL lost, diabetes, calculus, BoP, and halitosis. The response variable was the DMFT total score. The subject baseline status was male without cognitive impairment, diabetes, halitosis, calculus, and BoP. The effect of gender (female versus male) on the DMFT was significant, and the latter total score was higher for males than females (p = 0.001). Moreover, age had a positive significant effect on the DMFT total score (p < 0.001). Concerning cognitive impairment, subjects with AD showed higher DMFT than both aMCI and CONS (p = 0.001). However, the DMFT total score did not differ in aMCI and CONS groups. Furthermore, the effect of diabetes, calculus, BoP, and halitosis, treated as dichotomous variables (presence versus absence) was statistically significant for the explanation of DMFT (p from 0.038 to <0.001), while ADL lost was not statistically significant. Figure 1 shows the predicted number of DMFT by groups for subjects aged between 60 and 100 years. A diagnosis of AD predicted most of the DMFT score, particularly in subjects aged 80 years or over. Although the DMFT score increased with age, CONS had the lowest predicted value of the DMFT score.

Table 5

Results from Poisson regression analysis*

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | p | |

| Intercept | 2.117 | 0.344 | 6.139 | <0.001 |

| Sex (Female versus Male) | –0.179 | 0.057 | –3.138 | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.014 | 0.004 | 3.570 | <0.001 |

| AD | 0.214 | 0.085 | 2.521 | 0.001 |

| aMCI | 0.016 | 0.073 | 0.221 | 0.825 |

| ADL lost | –0.037 | 0.022 | –1.666 | 0.09 |

| Diabetes (Yes versus No) | –0.220 | 0.081 | –2.693 | 0.007 |

| Calculus (Yes versus No) | –0.244 | 0.095 | 2.547 | 0.010 |

| BoP (Yes versus No) | 0.203 | 0.098 | 2.070 | 0.038 |

| Halitosis (Yes versus No) | –0.215 | 0.079 | –2.714 | <0.001 |

*The outcome variable was DMFT total score; covariates were selected with a backward stepwise selection process and a lowering of the Akaike information criterion. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; BoP, bleeding on probing.

Fig.1

Predicted number of DMFT of subjects with age between 60 and 100 years in controls (CONS), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

DISCUSSION

This case-control study examined the association between cognitive impairment and oral health status in elderly subjects drawn from a population-based cohort. Dental status, periodontal conditions, and oral microbial load were assessed in 20 AD subjects, 20 aMCI, and 20 healthy controls, all of whom did not differ in demographic characteristics. The main findings of this study were: 1) patients with AD showed poor health status related to chronic periodontitis and lower DMFT scores than aMCI and CONS; 2) the F. n. bacterial load was significantly higher in AD than CONS and a higher T.d. bacterial load was found when comparing aMCI than AD; 3) no statistically significant differences were observed in OHR-QoL domains among the three study groups; and 4) the diagnosis of AD predicted tooth loss, particularly in subjects aged 80 years or over.

The mean age of the AD group was higher in this study (even if non-statistically significant) than aMCI and CONS. Similarly, the educational level and gender distribution of the three groups did not differ. Concerning disability, AD showed a statistically significant higher number of ADL and IADL lost than aMCI and CONS. Moreover, and as expected, AD showed significant lower global cognitive performance (i.e., MMSE score) than aMCI and CONS, with the former scoring significantly worse than the latter. Although AD and aMCI showed a higher score than CONS in the CES-D these differences were not significant. The comorbidity and biochemical/genetic parameters of the three study groups (lifestyles and vascular risk factors/diseases, hs-CRP levels, and APOE4 allele) did not differ; the latter was markedly more frequent in AD than aMCI and CONS, even if due to the small sample included in this study, results did not reach statistical significance.

The AD neurodegenerative-related process can be influenced by several modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors [4]. Of the latter, age has been recognized as one of the most important: the aging process determines a decline of cognitive functioning, with a subsequent and significant worsening of dietary and oral hygiene habits in elderly people [5, 11]. Older subjects usually have reduced access to medical services, and their caregivers may often not give due care in maintaining effective oral hygiene procedures [11, 13]. The development of ADL and IADL impairment, therefore, lead to a reduction in daily oral hygiene procedures, leading to an increased risk of periodontal disease, the major risk factor of tooth loss in adults.

Several researchers have investigated the association between cognitive impairment and oral health status, with particular attention to chronic periodontitis; the direction of this association needs to be clarified [11, 13, 40–46]. Chen et al. have demonstrated that periodontitis increased the risk of AD 1.7-fold after 10 years [42]. Iwasaki et al. demonstrated that severe periodontitis was significantly associated with an increased risk of subsequent cognitive decline and incident MCI in two prospective studies [45, 46]. Similarly, Nilsson et al. reported that subjects with signs of periodontitis reported lower MMSE scores than subjects without [44].

Periodontitis is an infectious bacterial inflammatory disease of the supporting tissue of the teeth, with gingival bleeding, bone resorption and, subsequently, tooth loss. It is caused by local inflammation supported by periodontal bacteria (e.g., P.g., F. n., and T.d.). There are two main periodontitis-associated mechanisms, which are potentially related to cognitive impairment: 1) an increasing cerebral inflammation state, caused by a pathological, infectious periodontal process; and 2) direct periodontal bacteria access to the central nervous system, thereby potentially triggering preexisting neurodegenerative pathology [47].

Chronic periodontitis is related to the rise of blood pro-inflammatory cytokines levels, such as TNF, IL-6, IL-10, IL-8, and CPR, all of which are involved in the progression of several chronic diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders [24]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines can induce a systemic inflammation potentially capable of increasing the production of cerebral cytokines, via olfactory or trigeminal nerve fibers [47]. A relative increase in the pro-inflammatory status was demonstrated in AD patients with periodontitis during a 6-month follow-up period in the study by Ide et al. [41]. Various periodontal bacteria have demonstrated the capability of reaching the central nervous system and infecting the brain. Some species, such as Porphyromonas or Treponema, have been found in the trigeminal ganglia or in brain specimens of patients affected by AD [11, 48, 49]. These reports suggest the hypothesis of a direct bacterial toxic activity on brain cells, in turn triggering several inflammatory pathways and reactions which are strictly associated with the degenerative process of AD, such as the amyloid deposition [50].

No statistically significant differences regarding the total oral microbial load of the studied groups were found in this research. However, the F.n. load was significantly higher in AD compared to CONS. F.n. is a gram-negative anaerobic bacterium with the ability to survive in high proportions of oxygen. It is one of the commonest species in the human gingival sulcus, and it may be isolated both from healthy and compromised periodontal teeth [51]. F.n. can have a crucial role in the development and progression of periodontal disease: its prevalence increases with the severity of periodontitis, the progression of the inflammation and the pocket depth [52]. Indeed, it is a member of the bridging complex with the capability to co-aggregate with early and late colonizers, such as P.g. or A.a. and amplifies the damages of periodontal tissues, thereby favoring the formation of pathogen biofilms [52–54]. Overall, from the data discussed above it can be hypothesized that the colonization of the Fusobacterium nucleatum contributed to the development of a more aggressive periodontal disease in the AD group, with a consequent increase in the number of lost teeth compared to the other groups. Accordingly, these results support a role of periodontitis in AD development. Indeed, the latter has a natural history culminating in the loss of dental elements [47]. Accordingly, AD patients in this study suffered from a marked reduction in the number of teeth and higher DMFT scores than aMCI and CONS.

The evaluation of the oral microbial load has also revealed a higher load of T.d. in the aMCI group compared to AD. This result may be due to the fact that the distribution of oral treponema is usually not uniform within the dentition or around individual teeth, with high inter-individual variability [47]. Although T.d. is more likely to occur in patients with periodontitis than in healthy subjects, it has been demonstrated that plaque from most diseased sites and nearby healthy sites did not always contain detectable levels of spirochetes [55]. Furthermore, the assessment of oral bacterial load did not reveal any significant difference in P.g. load between groups. The latter is considered a keystone pathogen in the development of chronic periodontitis and has been found in AD brains [56]. These data further confirm that oral bacteria may escape the periphery and access the brain of patients with dementia. Interestingly, and substantially in line with the results of this study, recent research has not revealed any significant differences in the levels of antibodies against selected bacteria (including T.d. and P.g.) in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of subjects between the groups, particularly in AD [57].

No statistically significant differences were observed regarding the periodontal indexes (i.e., CPI and PSR scores) of the three groups. Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences in the OHIP-14 domains between groups. Overall, these results probably reflect the relatively small sample of subjects included in this research and the cross-sectional study design, which were unable to detect the dynamic periodontal process of the enrolled patients. Of interest, a recent systematic review of the association of OHR-QoL of life in AD reported a statistically significant difference between AD and controls only in one study, while others did not describe any differences [58]. These finding suggest that AD patients have reduced ability in reporting oral health complaints using a self-filled questionnaire such as the OHIP-14 due to cognitive impairment, and further tools are required to improve the evaluation of OHR-QoL in subjects with dementia.

In conclusion, case-control studies have evaluated the relationship between AD and periodontitis but the results were inconclusive due to the wide heterogeneity in the studies performed and their methodologies. Some studies were hospital-based [46, 59, 60] and others were based on population-based cohorts [42, 43, 61]. Furthermore, the majority of studies were retrospective cohorts [42, 46, 60, 61] with only a few being classified as prospective cohort [60]. Consequently, the hospital-based data collection and the retrospective study design may have introduced a selection bias, a misclassification or information bias, thus not representing the exposure experience of the true source population [60]. Furthermore, the authors of the aforementioned studies applied a wide heterogeneity of evaluation methods regarding the diagnosis of cognitive impairment (e.g., use of global cognitive measures, ICD diagnoses, clinical criteria) and chronic periodontitis (e.g., clinical diagnosis, standardized tools, oral microbial load) [47].

In order to reduce this heterogeneity, the authors of this study performed a population-based case-control study with an inherent reduction in selection bias. Moreover, a comprehensive oral health status assessment was conducted, including several standardized clinical tools and the evaluation of oral microbial load. Nonetheless, several limitations of this study should be considered. First, aMCI and AD were diagnosed according to clinical criteria, in the absence of the biomarkers of neurodegeneration or postmortem confirmation, leading to issues of diagnostic uncertainty. In order to reduce this problem, a multidimensional clinical and cognitive protocol was used, and the clinical classification was supported by 1.5 T MRI imaging to exclude vascular cognitive impairment. Second, a relatively small sample size of subjects was included in this research. This might increase the likelihood of spurious associations and a lack of significance (e.g., in some OHIP-14 domain mean scores of aMCI and AD were clearly lower than in CONS). Third, residual confounding cannot be excluded, and mechanisms independent of periodontitis (e.g., others comorbidities, difficulty in accessing dental care) could be associated with tooth loss in people with dementia. Lastly, the cross-sectional study design precludes making causal inferences about the relationship between periodontitis and the study outcomes (aMCI and AD).

In conclusion, in this study AD was associated with the presence of chronic periodontitis and tooth loss, possibly via a low-grade systemic inflammation due to F.n. Prospective ZAP data and that from other population-based cohorts are required to clarify the role of periodontitis as a risk factor for AD and dementia. These data would have relevant implication for the treatment of AD and its prevention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The ZAP 10-year follow-up data collection was completely supported by a grant project for young researchers 2007 (GR-2007-686973) from the Italian Ministry of Health to R.M., who is the PI of the ZAP. The sub-study regarding oral health receives further funding from a grant of the University of Palermo to G.C and R.M. (FFR-2012-ATE-0308). The authors thank all participants and all persons working in the Zabút Aging Project for data collection and management, with special regards to Dr. Angela Aronica and Dr. Nicoletta Termine.

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0385r1).

REFERENCES

[1] | World Health Organization ((2015) ) World Report on Ageing and Health. pp. 1–247. |

[2] | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ((2003) ) Trends in aging— United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 52: , 101–104, 106. |

[3] | Di Fiandra T , Canevelli M , Di Pucchio A , Vanacore N , Italian Dementia National Plan Working Group ((2015) ) The Italian Dementia National Plan. Commentary.á. Ann Ist Super Sanit 51: , 261–264. |

[4] | Scheltens P , Blennow K , Breteler MMB , de Strooper B , Frisoni GB , Salloway S , Van der Flier WM ((2016) ) Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 388: , 505–517. |

[5] | Monastero R , Caruso C , Vasto S ((2014) ) Alzheimer’s disease and infections, where we stand and where we go. Immun Ageing 11: , 1–4. |

[6] | Winblad B , Palmer K , Kivipelto M , Jelic V , Fratiglioni L , Wahlund L-O , Nordberg A , Backman L , Albert M , Almkvist O , Arai H , Basun H , Blennow K , de Leon M , DeCarli C , Erkinjuntti T , Giacobini E , Graff C , Hardy J , Jack C , Jorm A , Ritchie K , van Duijn C , Visser P , Petersen RC ((2004) ) Mild cognitive impairment - beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 256: , 240–246. |

[7] | Mariani E , Monastero R , Mecocci P ((2007) ) Mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis 12: , 23–35. |

[8] | Monastero R , Mangialasche F , Camarda C , Ercolani S , Camarda R ((2009) ) A systematic review of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 18: , 11–30. |

[9] | Albert MS , DeKosky ST , Dickson D , Dubois B , Feldman HH , Fox NC , Gamst A , Holtzman DM , Jagust WJ , Petersen RC , Snyder PJ , Carrillo MC , Thies B , Phelps CH ((2011) ) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7: , 270–279. |

[10] | Singhrao SK , Harding A , Poole S , Kesavalu L , Crean S ((2015) ) Porphyromonas gingivalis periodontal infection and its putative links with Alzheimer’s disease. Mediators Inflamm 2015: , 137357. |

[11] | Tonsekar PP , Jiang SS , Yue G ((2017) ) Periodontal disease, tooth loss and dementia: Is there a link? A systematic review. Gerodontology 34: , 151–163. |

[12] | Lexomboon D , Trulsson M , Wãrdh I , Parker MG ((2012) ) Chewing ability and tooth loss: Association with cognitive impairment in an elderly population study. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: , 1951–1956. |

[13] | Noble JM , Scarmeas N , Papapanou PN ((2013) ) Poor oral health as a chronic, potentially modifiable dementia risk factor: review of the literature. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13: , 384. |

[14] | Tonetti MS , Bottenberg P , Conrads G , Eickholz P , Heasman P , Huysmans M-C , López R , Madianos P , Müller F , Needleman I , Nyvad B , Preshaw PM , Pretty I , Renvert S , Schwendicke F , Trombelli L , van der Putten G-J , Vanobbergen J , West N , Young A , Paris S ((2017) ) Dental caries and periodontal diseases in the ageing population: call to action to protect and enhance oral health and well-being as an essential component of healthy ageing - Consensus report of group 4 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries be. J Clin Periodontol 44: , S135–S144. |

[15] | Gil-Montoya JA , Sánchez-Lara I , Carnero-Pardo C , Fornieles-Rubio F , Montes J , Barrios R , Gonzalez-Moles MA , Bravo M ((2016) ) Oral hygiene in the elderly with different degrees of cognitive impairment and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 65: , 642–647. |

[16] | Zuluaga DJM , Montoya JAG , Contreras CI , Herrera RR ((2012) ) Association between oral health, cognitive impairment and oral health-related quality of life. Gerodontology 29: , 667–673. |

[17] | Martande SS , Pradeep AR , Singh SP , Kumari M , Suke DK , Raju AP , Naik SB , Singh P , Guruprasad CN , Chatterji A ((2014) ) Periodontal health condition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 29: , 498–502. |

[18] | Highfield J ((2009) ) Diagnosis and classification of periodontal disease. Aust Dent J 54(Suppl 1): , S11–26. |

[19] | Burt B , Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology ((2005) ) Position paper - Epidemiology of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 76: , 1406–1419. |

[20] | Chapple ILC , Bouchard P , Cagetti MG , Campus G , Carra M-C , Cocco F , Nibali L , Hujoel P , Laine ML , Lingstrom P , Manton DJ , Montero E , Pitts N , Rangé H , Schlueter N , Teughels W , Twetman S , Van Loveren C , Van der Weijden F , Vieira AR , Schulte AG ((2017) ) Interaction of lifestyle, behaviour or systemic diseases with dental caries and periodontal diseases: consensus report of group 2 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol 44: , S39–S51. |

[21] | Beck JD , Sharp T , Koch GG , Offenbacher S ((1997) ) A 5-year study of attachment loss and tooth loss in community-dwelling older adults. J Periodontal Res 32: , 516–523. |

[22] | Pizzo G , Guiglia R , Russo L Lo , Campisi G ((2010) ) Dentistry and internal medicine: from the focal infection theory to the periodontal medicine concept. Eur J Intern Med 21: , 496–502. |

[23] | Olsen I , Singhrao SK ((2015) ) Can oral infection be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease? J Oral Microbiol 7: , 1–16. |

[24] | Cestari JAF , Fabri GMC , Kalil J , Nitrini R , Jacob-Filho W , De Siqueira JTT , Siqueira SRDT ((2016) ) Oral infections and cytokine levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment compared with controls. J Alzheimers Dis 52: , 1479–1485. |

[25] | Scannapieco FA , Cantos A ((2016) ) Oral inflammation and infection, and chronic medical diseases: implications for the elderly. Periodontol 2000 72: , 153–175. |

[26] | Fiorillo L , Cervino G , Laino L , D’Amico C , Mauceri R , Tozum TF , Gaeta M , Cicciú M ((2019) ) Porphyromonas gingivalis, periodontal and systemic implications: a systematic review. Dent J 7: , 114. |

[27] | Carlesimo GA , Caltagirone C , Gainotti G , Fadda L , Gallassi R , Lorusso S , Marfia G , Marra C , Nocentini U , Parnetti L ((1996) ) The Mental Deterioration Battery: normative data, diagnostic reliability and qualitative analyses of cognitive impairment. Eur Neurol 36: , 378–384. |

[28] | American Psychiatric Association ((2000) ) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, DC. |

[29] | McKhann GM , Knopman DS , Chertkow H , Hyman BT , Jack CR , Kawas CH , Klunk WE , Koroshetz WJ , Manly JJ , Mayeux R , Mohs RC , Morris JC , Rossor MN , Scheltens P , Carrillo MC , Thies B , Weintraub S , Phelps CH ((2011) ) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7: , 263–269. |

[30] | Grigoletto F , Zappalá G , Anderson DW , Lebowitz BD ((1999) ) Norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination in a healthy population. Neurology 53: , 315–320. |

[31] | Katz S , Ford AB , Moskowitz RW , Jackson BA , Jaffe MW ((1963) ) Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185: , 914–919. |

[32] | Lawton MP , Brody EM ((1969) ) Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9: , 179–186. |

[33] | Radloff LS ((1977) ) The CES-D Scale. Appl Psychol Meas 1: , 385–401. |

[34] | Marino Gammazza A , Restivo V , Baschi R , Caruso Bavisotto C , Cefalú AB , Accardi G , Conway de Macario E , Macario AJL , Cappello F , Monastero R ((2018) ) Circulating molecular chaperones in subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: data from the Zabút Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis, doi: 10.3233/JAD-180825. |

[35] | Cook Z , Kirk S , Lawrenson S , Sandford S ((2005) ) Use of BMI in the assessment of undernutrition in older subjects: reflecting on practice. Proc Nutr Soc 64: , 313–317. |

[36] | Monastero R , Cefalú AB , Camarda C , Buglino CM , Mannino M , Barbagallo CM , Lopez G , Camarda LKC , Travali S , Camarda R , Averna MR ((2003) ) No association between Glu298Asp endothelial nitric oxide synthase polymorphism and Italian sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett 341: , 229–232. |

[37] | Petersen PE , Baez RJ , WHO ((2013) ), Oral Health Surveys Basic Methods - Fifth Edition. |

[38] | Landry RG , Jean M ((2002) ) Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR) Index: precursors, utility and limitations in a clinical setting. Int Dent J 52: , 35–40. |

[39] | Corridore D , Campus G , Guerra F , Ripari F , Sale S , Ottolenghi L ((2013) ) Validation of the Italian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (IOHIP-14). Ann Stomatol (Roma) 4: , 239–243. |

[40] | Arrivè E , Letenneur L , Matharan F , Laporte C , Helmer C , Barberger-Gateau P , Miquel JL , Dartigues JF ((2012) ) Oral health condition of French elderly and risk of dementia: A longitudinal cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 40: , 230–238. |

[41] | Ide M , Harris M , Stevens A , Sussams R , Hopkins V , Culliford D , Fuller J , Ibbett P , Raybould R , Thomas R , Puenter U , Teeling J , Perry VH , Holmes C ((2016) ) Periodontitis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 11: , e0151081. |

[42] | Chen C-K , Wu Y-T , Chang Y-C ((2017) ) Association between chronic periodontitis and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective, population-based, matched-cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther 9: , 56. |

[43] | Nilsson H , Sanmartin Berglund J , Renvert S ((2018) ) Longitudinal evaluation of periodontitis and development of cognitive decline among older adults. J Clin Periodontol 45: , 1142–1149. |

[44] | Nilsson H , Berglund JS , Renvert S ((2018) ) Periodontitis, tooth loss and cognitive functions among older adults. Clin Oral Investig 22: , 2103–2109. |

[45] | Iwasaki M , Kimura Y , Ogawa H , Yamaga T , Ansai T , Wada T , Sakamoto R , Ishimoto Y , Fujisawa M , Okumiya K , Miyazaki H , Matsubayashi K ((2018) ) Periodontitis, periodontal inflammation, and mild cognitive impairment: A 5-year cohort study. J Periodontal Res 54: , 233–240. |

[46] | Iwasaki M , Yoshihara A , Kimura Y , Sato M , Wada T , Sakamoto R , Ishimoto Y , Fukutomi E , Chen W , Imai H , Fujisawa M , Okumiya K , Taylor GW , Ansai T , Miyazaki H , Matsubayashi K ((2016) ) Longitudinal relationship of severe periodontitis with cognitive decline in older Japanese. J Periodontal Res 51: , 681–868. |

[47] | Dioguardi M , Di Gioia G , Caloro GA , Capocasale G , Zhurakivska K , Troiano G , Lo Russo L , Lo Muzio L ((2019) ) The association between tooth loss and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis of case control studies. Dent J (Basel) 7: , 49. |

[48] | Riviere GR , Riviere KH , Smith KS ((2002) ) Molecular and immunological evidence of oral Treponema in the human brain and their association with Alzheimer’s disease. Oral Microbiol Immunol 17: , 113–118. |

[49] | Poole S , Singhrao SK , Kesavalu L , Curtis MA , Crean S ((2013) ) Determining the presence of periodontopathic virulence factors in short-term postmortem Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. J Alzheimers Dis 36: , 665–677. |

[50] | Sochocka M , Zwolińska K , Leszek J ((2017) ) The infectious etiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol 15: , 996–1009. |

[51] | Han YW ((2015) ) Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol 23: , 141–147. |

[52] | Rogers AH , Zilm PS , Diaz PI ((2002) ) Fusobacterium nucleatum supports the growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis in oxygenated and carbon-dioxide-depleted environments. Microbiology 148: , 467–472. |

[53] | Kaplan CW , Lux R , Haake SK , Shi W ((2009) ) Theouter membrane protein RadD is an arginine-inhibitable adhesin required for inter-species adherence and the structured architecture of multispecies biofilm. Mol Microbiol 71: , 35–47. |

[54] | Chaushu S , Wilensky A , Gur C , Shapira L , Elboim M , Halftek G , Polak D , Achdout H , Bachrach G , Mandelboim O ((2012) ) Direct recognition of Fusobacterium nucleatum by the NK cell natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46 aggravates periodontal disease. PLoS Pathog 8: , e1002601. |

[55] | Riviere GR , Smith KS , Carranza N , Tzagaroulaki E , Kay SL , Dock M ((1995) ) Subgingival distribution of Treponema denticola, Treponema socranskii, and pathogen-related oral spirochetes: prevalence and relationship to periodontal status of sampled sites. J Periodontol 66: , 829–837. |

[56] | Sadrameli M , Bathini P , Alberi L ((2020) ) Linking mechanisms of periodontitis to Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol 33: , 230–238. |

[57] | Laugisch O , Johnen A , Maldonado A , Ehmke B , Bürgin W , Olsen I , Potempa J , Sculean A , Duning T , Eick S ((2018) ) Periodontal pathogens and associated intrathecal antibodies in early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 66: , 105–114. |

[58] | Ming Y , Hsu S-W , Yen Y-Y , Lan S-J ((2019) ) Association of oral health–related quality of life and Alzheimer disease: A systematic review. J Prosthet Dent, doi; 10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.08.015. |

[59] | Lunet N , Azevedo A ((2009) ) On the comparability of population-based and hospital-based case-control studies. Gac Sanit 23: , 564. |

[60] | Nascimento PC , Castro MML , Magno MB , Almeida APCPSC , Fagundes NCF , Maia LC , Lima RR ((2019) ) Association between periodontitis and cognitive impairment in adults: a systematic review. Front Neurol 10: , 323. |

[61] | Choi S , Kim K , Chang J , Kim SM , Kim SJ , Cho HJ , Park SM ((2019) ) Association of chronic periodontitis on Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 67: , 1234–1239. |