Creating Cultural and Lifestyle Awareness About Dementia and Co-morbidities

Abstract

Dementia is a major health concern in society, particularly in the aging population. It is alarmingly increasing in ethnic minorities such as Native Americans, African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, and to some extent Asians. With increasing comorbidities of dementia such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension, dementia rates are expected to increase in the next decade and beyond. Understanding and treating dementia, as well as determining how to prevent it, has become a healthcare priority across the globe for all races and genders. Awareness about dementia and its consequences such as healthcare costs, and caregiver burden are immediate needs to be addressed. Therefore, it is high time for all of us to create awareness about dementia in society, particularly among Hispanics/Latinos, Native Americans, and African Americans. In the current article, we discuss the status of dementia, cultural, and racial impacts on dementia diagnosis and care, particularly in Hispanic populations, and possible steps to increase dementia awareness. We also discussed factors that need to be paid attention to, including, cultural & language barriers, low socioeconomic status, limited knowledge/education, religious/spiritual beliefs and not accepting modern medicine/healthcare facilities. Our article also covers both mental & physical health issues of caregivers who are living with patients with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease-related dementias. Most importantly, we discussed possible measures to create awareness about dementia, including empowering community advocacy, promoting healthy lifestyle choices, education on the impact of nutrition, encouraging community participation, and continued collaboration and evaluation of the success of dementia awareness.

INTRODUCTION

Dementia manifests as a syndrome marked by a deterioration in cognitive functions, including memory, cognition, and reasoning, reaching a severity that hinders daily activities. Rather than being a distinct ailment, it represents a collection of symptoms linked to various underlying conditions like vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal dementia, or Lewy body dementia [1]. AD and other unexplained dementias are linked to epigenetic changes, which establish a connection between environmental factors and genetic predispositions in disease development. This association has prompted the exploration of therapeutic strategies targeting epigenetic mechanisms for managing these conditions. Epigenetic modifications gradually emerge over time in response to environmental influences [2]. A comprehensive model of AD etiology should consider both genetic and non-genetic factors, with polygenic effects playing a significant role. For instance, the neuronal presence of ApoE4 triggers the onset of AD via diverse pathophysiological mechanisms. Additionally, the APOE ∈4 allele is the strongest genetic risk factor for AD [3]. Lahiri and colleagues proposed that AD encompasses a spectrum of conditions with distinct causes, including rare fully genetic cases (e.g., familial AD) and sporadic cases triggered by environmental factors like head trauma or oxidative stress, suggesting a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers [4]. Understanding and treating dementia, as well as determining how to prevent it, has become a healthcare priority across the globe. Individuals with mental illness face a dual challenge. On one side, they grapple with the symptoms and impairments arising from the condition. On the other, they encounter stereotypes and prejudice fueled by misunderstandings about mental illness [5]. The consequences of stigma attached to mental illnesses like dementia include social isolation, a decline in the quality of life, and a loss of independence. Moreover, stigma serves as a significant obstacle to seeking and obtaining support, diagnosis, treatment, and information [6]. Consequently, mitigating the stigma surrounding individuals with dementia stands as a crucial global policy objective, highlighted in the World Health Organization Global Action Plan [7]. While dementia is more common in some populations than others, there is not a corner of the world that has not had to confront the rise of this group of neurodegenerative disorders characterized by multiple cognitive impairments, but most noticeably, loss of memory [8].

The projected growth suggests that the global count of individuals with dementia is anticipated to rise from 57.4 million cases in 2019, with a 95% uncertainty interval between 50.4 and 65.1 million, to 152.8 million cases by the year 2050 [9]. It impacts people from all walks of life and does not discriminate [10]. To create a plan of cultural and lifestyle awareness about dementia and co-morbidities, we must look at how culture defines us and what lifestyle issues are behind our current situation in one of our fastest-growing demographic groups—namely a growing elderly Hispanic population.

The United States boasts the world’s most extensive immigrant population, comprising approximately 45 million individuals born outside the country. Among these immigrants, more than 44% are of Hispanic origin, followed by non-Hispanic Asians at 27%, non-Hispanic Whites at 18%, and non-Hispanic Blacks at 9% [11]. Various factors, including increased rates of marital disruption, delayed first births, and reduced fertility, have contributed to a reduction in the average family size in the United States throughout the twentieth century. While Mexican Americans traditionally had larger families than non-Hispanics, they, too, have witnessed a decline in average family size, expected to persist in the future. Concurrently, life expectancy has risen notably, particularly among Mexican Americans, surpassing that of African Americans and European Americans. This has led to an escalating old-age dependency ratio, presenting potential challenges for Mexican American families and social policies across government levels [12]. They are also a population that has higher rates of comorbidities like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [13] than their White counterparts and are far less represented in medical research [14]. The likelihood of developing AD is estimated to be 1.5 times higher in the Hispanic community compared to White non-Hispanics [13, 15]. AD has reached epidemic proportions, carrying substantial socioeconomic implications. While aging remains the primary risk factor for AD, ongoing research is examining various demographic factors contributing to the increasing prevalence of AD in the United States. One noteworthy factor is linked to the rapid growth of the Hispanic population [13]. Despite facing an elevated risk, Hispanics are inadequately represented in clinical trials. The absence of meaningful participation from Hispanic Americans and other underrepresented groups in AD clinical trials and research hinders a comprehensive understanding of how racial and ethnic variations might impact the effectiveness and safety of potential new treatments.

A major goal of the Healthy Aging study currently being undertaken by the Reddy Internal Medicine lab at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center is to research healthy aging practices across all populations. Our study aims to identify the factors influencing cognitive health in the aging population. Aligning with the World Health Organization’s emphasis on comprehending the mechanisms of healthy aging, our goal is to identify lifestyle factors and prevention strategies against dementia [16]. Therefore, it is essential to explore the factors that foster healthy cognitive aging and impede the progression toward dementia. However, to date, most participants have been white. This paper seeks to understand the cultural considerations that will allow this research team to effectively engage with and recruit Hispanic participants for the Healthy Aging Study. An important byproduct of this literature review will be to guide the development of a program to increase awareness about dementia and comorbidities among the Hispanic population. A third anticipated outcome will be to utilize cultural best practices to develop a program of lifestyle enhancement for this same group.

WHY DEVELOP THIS PROGRAM NOW?

As the elderly population vulnerable to cognitive impairment continues to rapidly increase, there is a pressing need to prioritize efforts in enhancing the health and quality of life for this demographic. Despite significant advancements in extending longevity, it is crucial to recognize that prolonged life does not always correlate with sustained health and independence. Preserving normal cognitive function is vital for upholding independence, as the decline in cognitive abilities stands as one of the most common and dreaded challenges in the later stages of life. The likelihood of experiencing cognitive impairment escalates significantly with advancing age [17]. Conducting a study that delves into the lifestyle factors contributing to cognitive health in the aging population is of paramount importance. As our elderly demographic continues to grow, understanding the elements that positively impact cognitive well-being becomes crucial for promoting a higher quality of life. This type of research not only provides insights into effective preventive measures against cognitive decline but also empowers individuals, healthcare professionals, and policymakers to implement targeted interventions. By identifying lifestyle practices that foster cognitive health, we pave the way for informed strategies that can enhance the overall well-being and independence of the aging population, ensuring they enjoy healthier and more fulfilling lives.

The burgeoning population of elderly Hispanics underscores the urgent necessity to prioritize and comprehend their cognitive health. Addressing the unique challenges this demographic faces is crucial to ensuring their well-being, fostering understanding, and implementing targeted measures to safeguard cognitive vitality in later years. Latinos/Hispanics residing in the United States face a higher prevalence and more severe trajectory of specific health conditions linked to dementia compared to the general population. A meticulous examination of these disparities is essential for enhancing the early and accurate identification of neurodegenerative processes and intervening in potentially treatable causes of cognitive decline. This scrutiny entails investigating both biological and sociocultural factors contributing to medical comorbidities within various Latino/Hispanic subgroups. Common medical comorbidities associated with dementia and cognitive decline among Latinos/Hispanics in the U.S. include type 2 diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea, thyroid disease, infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C, depression, alcohol abuse, and nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin B12 and folate [18].

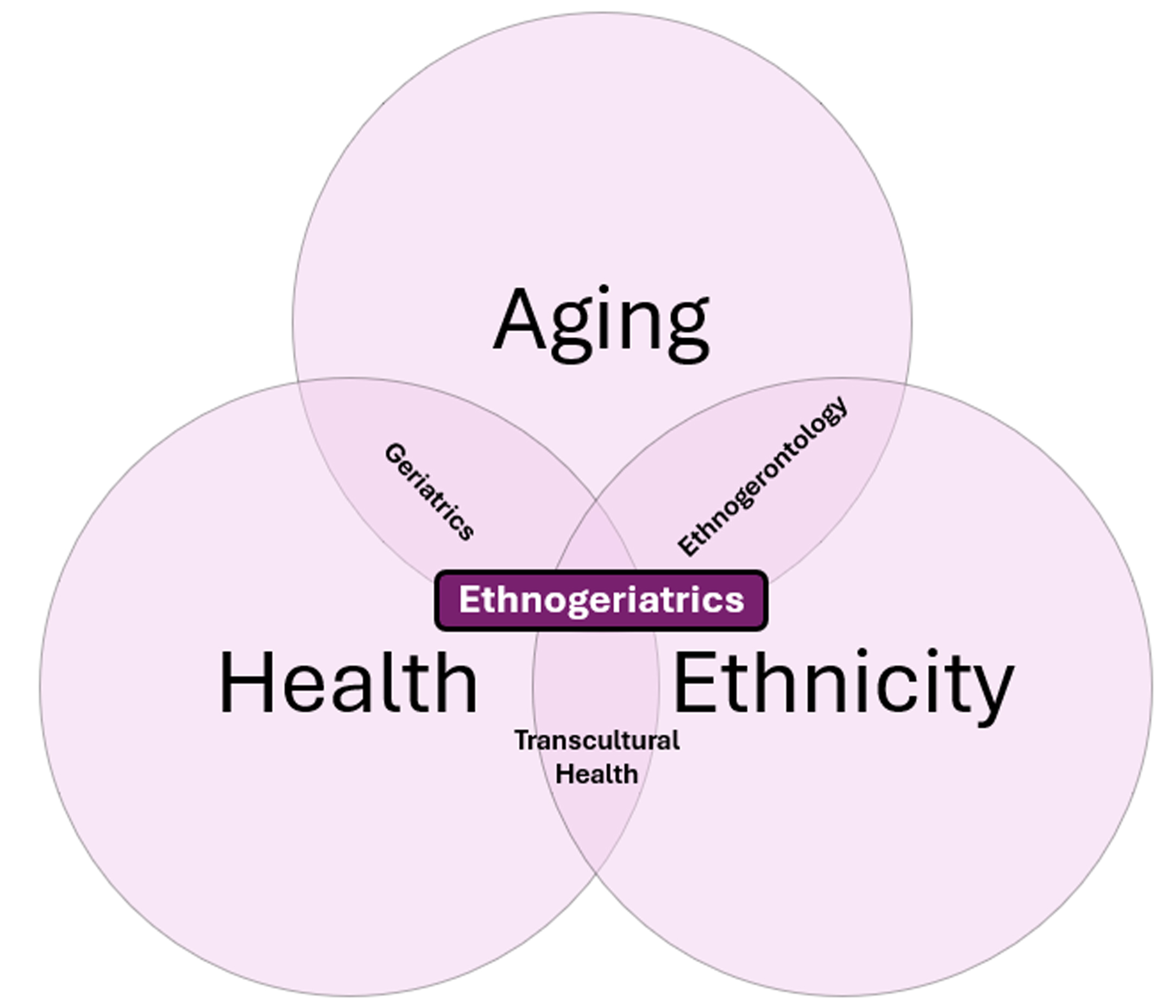

The Healthy Aging Study at P. Hemachandra Reddy’s laboratory is poised to expand the recruitment of Hispanic participants but is aware that additional cultural considerations need to be addressed. To truly achieve an understanding of healthy aging principles, the Hispanic population must be well represented in our study. A deficiency in the representation of ethnic groups in randomized controlled trials has been documented for both neurological and non-neurological disorders [19–21]. Despite the growing volume of research on dementia in recent decades, the involvement of patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds in studies for dementia treatment remains notably insufficient [22]. Hispanics experience an extended duration with AD and related dementias (AD/ADRD), exhibit elevated rates of neuropsychiatric symptoms, and tend to underutilize long-term services and supports. Despite over 200 clinical trials involving over 70,000 participants across the United States, Hispanics constitute only a small fraction of enrolled participants, despite comprising 19% of the total U.S. population [23]. On a macro level, research trends for this demographic are troubling and best practices for interventions must be developed and based on ethnogeriatric principles. Simply stated, ethnogeriatrics is the study of aging populations from diverse ethnic backgrounds. As shown in Fig. 1, it is a field of study with many overlapping and intersectional dynamics.

Fig. 1

Ethnogeriatrics refers to the healthcare of elderly individuals, focusing on the convergence of aging, health, ethnicity, and culture.

As previously noted, the population of Hispanic elderly is increasing rapidly. It is the fastest-growing population subgroup in the United States. Sadly, this is also the group of people most likely to suffer from dementia, particularly ADRD. In addition to the prevalence of various dementias, this same population has an extremely high rate of comorbidities, notably cardiovascular disease, high cholesterol, diabetes, and kidney disease [24]. In 2019, Hispanics in the United States exhibited a life expectancy advantage of 3.0 years and 7.1 years compared to non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks, respectively. This advantage persisted despite Hispanic households having real-household income values 26 percentage points lower than non-Hispanic White households [25]. However, despite their longer life expectancy compared to other racial and ethnic groups, Hispanics still confront similar health issues, including some of the primary causes of illness and death.

The fact that Hispanics are woefully underrepresented in research studies certainly speaks to systemic issues such as poverty and disparity in access to healthcare. However, a more insidious issue may also be at play—the reluctance of medical researchers to contemplate the impact of cultural considerations as they recruit research study participants, particularly those of diverse ethnic backgrounds. Although the National Institutes of Health, the FDA, and both Medicaid and Medicare have attempted to create programming that will improve the representation of ethnic minorities in research for some time, studies show that while minorities make up almost half of the US population, they make up less than 18% of medical research participants [14]. This disparity impacts research at all levels, complicating the recruitment, enrollment, and retention of study participants. If not addressed, this issue will also lead to faulty research results that are unable to provide culturally appropriate interventions [14]. Based on this knowledge, there is an opportunity to vastly improve our understanding of this population and create implementable strategies to improve their participation in and benefit from medical research on dementia and its comorbidities.

WHAT IS CULTURE?

To create a cultural shift, we must first define what culture is. In a presentation titled “Belief and Traditions that Impact Latino Healthcare,” Dr. Claudia Medina of LSU School of Public Health defines culture as “one’s worldview which includes experiences, expressions, symbols, materials, customs, behaviors, morals, values, attitudes, and beliefs created and communicated among individuals and passed down through generations.” Dr. Medina goes on to state that within a culture, there are concepts that define the use of language, the role of family, and the importance of religion and spirituality, among others.

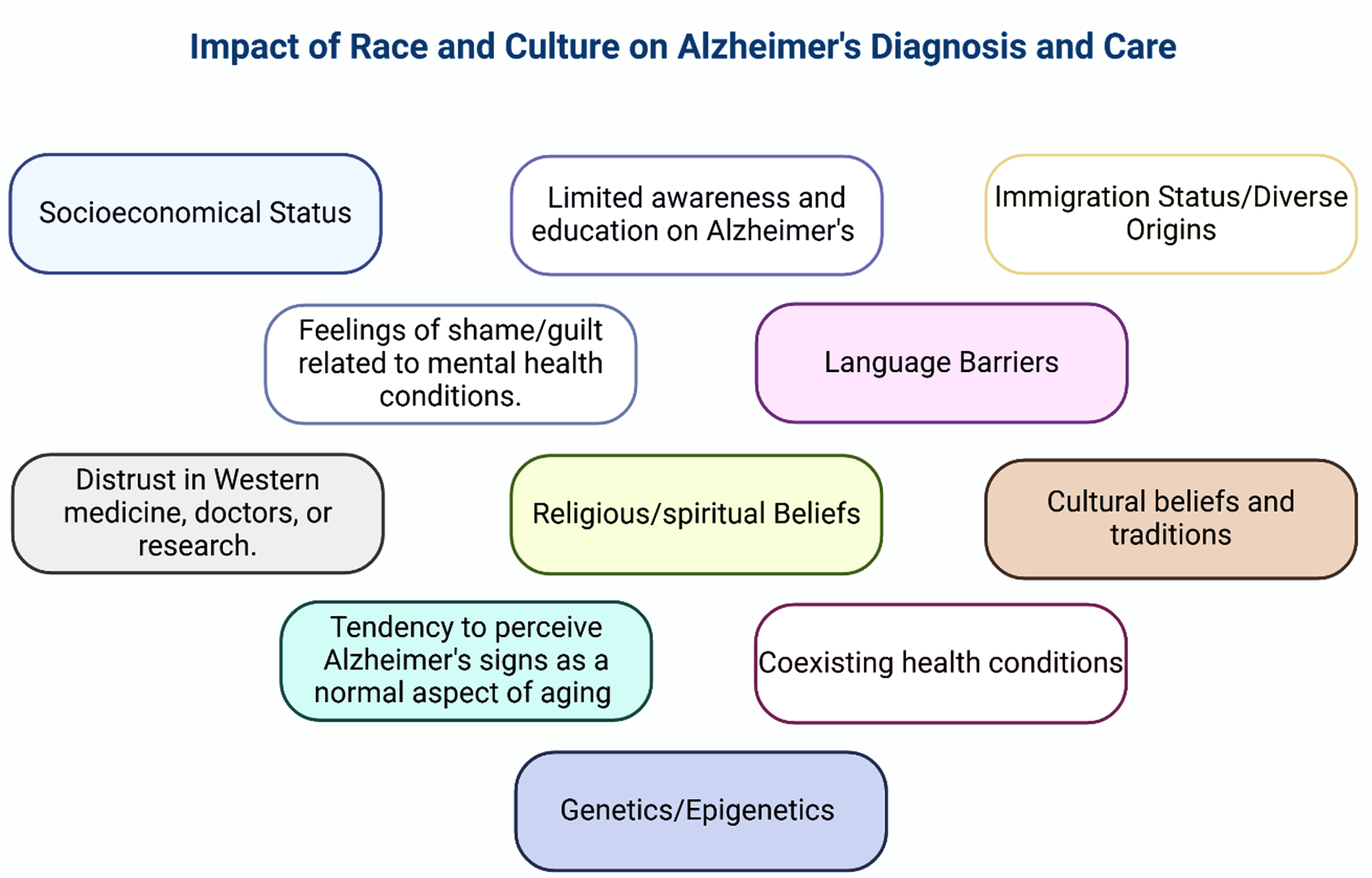

Another helpful definition of culture states that a culture includes collections of values, beliefs, and habits learned during socialization, which then shape the sphere of ideas, perceptions, and decisions, and how those individuals act and react [26, 27]. As we strive to uncover the secret to unlocking dementia, the scourge of our time for our increasingly elderly population, we would be remiss in not considering how culture may impact our findings. In recent times, increased focus has been placed on understanding racial, ethnic, and cultural variations in the dementia caregiving experience, especially as the older adult population in the United States becomes more diverse. Assumptions drawn from research on White Americans may not universally apply, and service delivery based on such assumptions may prove inappropriate for other groups [28]. Recognizing potential variations in the dementia diagnosis and care experience across racial, ethnic, and cultural lines can enable healthcare professionals and policymakers to better cater to the diverse needs of elderly populations of different ethnic groups, refer to Fig. 2. Culturally adapting evidence on dementia prevention for ethnically diverse communities entails thoughtful adjustments in the mode of delivery, imagery, and tone of the resource under development. This process involves ensuring cultural adequacy, anticipating the needs of the end-users, and effectively managing linguistic challenges associated with working across multiple languages [29]. The approach taken in applying these ideas to our studies will either enhance or impede the success and scalability of our results.

Fig. 2

Impact of race, culture, and ethnicity on dementia diagnosis and care. Cultural and racial beliefs about dementia vary widely, shaped by factors like viewing signs as normal aging, limited awareness of mental health conditions, socioeconomic status, immigration status, shame and guilt, language barriers, distrust in Western medicine, comorbidities, cultural beliefs, hesitancy in seeking medical help, genetics, and epigenetics, seeking support from religious leaders, and using religion or prayer to cope with caregiving stress.

In this paper, we will consider how many of these cultural considerations impact the willingness of Hispanics to a) participate in medical research and b) alter their behaviors to prevent the disease processes uncovered by this research. We will also develop a better understanding of how the underlying culture affects their feelings about research participation in general and the medical aspect of the research more specifically.

In the area of our study, the Hispanic population would be our primary focus, so it will be through that lens that we examine these cultural concepts. Hispanics as a whole share a strong heritage that includes their attitudes about things like family and religion. Yet within the demographic of “Hispanic,” there are a wide variety of subgroups from geographic locations around the world that have distinct cultural beliefs and customs, further complicating our understanding and ability to provide wide-ranging intervention.

INFLUENCES OF HISPANIC CULTURE

Religion

Religion and spirituality show a positive association with cognitive function and individual dementia risk factors. However, there is a scarcity of studies that have thoroughly explored the association between religion/spirituality and dementia. The identification of potential protective factors against the development of dementia is crucial in mitigating the increasing burden of this condition [30]. Most Hispanics are Catholic, and their religious affiliation is about much more than going to church on Sunday. It is an integral part of their lives and community. There is a tendency, particularly among older Hispanics, to make health-related deals with protective saints in the Catholic religion, promising that if they are healed, for example, they will fulfill some promise like completing a pilgrimage to a sacred site. This practice is known as making mandas [31]. It is also hypothesized that Hispanics, particularly those of advanced age, feel that they have little to no control over their lives and that active practice of their religious rituals gives them a feeling of power in a world where they feel powerless [32]. Additionally, engagement in religious practices and participation in a religious community seems to be key to improved mental health, improving self-worth, and engaging patrons in social interaction [33]. Nguyen’s research indicates that increased participation in and attendance at church supports fewer instances of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse among this population. There is also a very large influence in magico-religious beliefs among Hispanics, particularly the elderly and more traditional. This paradigm states that supernatural forces dominate the fate of the world and all those that are in it. The interaction of Catholicism and supernatural interventions leave its followers with a certain fatalistic approach towards medical intervention. They believe that God’s will be done.

Views on health and healing

This fatalism carries over into Hispanic views on both preventative health care as well as prescribed medical interventions even at the latest stages of illness or disease. It is common for the Hispanic population to think dementia is just a normal part of aging, to say they will not live long enough to get dementia, or to find the suggestion that they undergo cognitive testing to be an insult [34].

A study by Cabrera and colleagues addresses the limitation of clustering Hispanics as a single group in AD research by examining knowledge and attitudes among two distinct Latino groups—Mexicans and Puerto Ricans. The study, involving five focus groups and two interviews in Spanish with participants aged 40 to 60 in Michigan, revealed common themes like improving knowledge and awareness, barriers, and home-based family care. Puerto Rican participants expressed more concerns about the disease, while Mexicans highlighted a lack of knowledge as a significant theme [35]. While Latino individuals are often categorized based on linguistic similarities, this term encompasses a highly diverse group in terms of geography, culture, race, and genetics [36]. Additionally, Latinos residing in the United States exhibit significant variations in their historical immigration experiences, acculturation to the United States [37], as well as differences in socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, English-language proficiency, and education. These diverse factors contribute to distinct perspectives and perceptions of dementia within the Hispanic population.

In the older members of Hispanic communities there also continues to exist a reliance on folk medicine and herbal remedies, usually “prescribed” by a folk healer or “curandero.” In this tradition, illnesses are thought of and referred to as either hot or cold. Diabetes, one of the diseases most prevalent in elderly Hispanics, is hot. This population is also most prone to believe myths that have developed within the community. One such idea is that elderly Hispanics are resistant to taking insulin as a treatment for diabetes because they have heard from trusted friends that the injection causes blindness and amputation of limbs. It is not a direct correlation between insulin and blindness for example, but because so many of the elderly are diagnosed at later stages of the disease, these outcomes are more likely. But it is myths, and word-of-mouth stories like this that can drive a wedge in the opportunity to include this population in both clinical research and improved medical treatment.

Familism

Familism is a cultural value characterized by a focus on collectivism and strong family attachment. It encompasses three key elements: familial obligations (the sense of duty to provide care), perceived support (the perception of support received from family), and family as referents (using the views and opinions of relatives as guides for behavior and attitudes) [38]. When compared to Whites, Hispanic participants demonstrated elevated levels of familism. Exploratory analyses revealed notable connections between familism and self-efficacy. Within the Hispanic subgroup, variations in familism were observed based on acculturation levels [39]. Almeida and colleagues discovered that familism tends to be lower among Hispanic individuals who predominantly speak English at home, were born in the United States, and have higher socioeconomic status. These findings suggest that familism may decrease with increased exposure to U.S. values over time [40]. However, conflicting evidence exists, as some studies, such as Crist and Fellows found that familism tended to be higher among more acculturated individuals, challenging the notion of an inverse relationship between familism and acculturation [41].

The importance of family in Hispanic culture cannot be overstated. And yet the role of the family in the practice of caregiving is far from ideal. The belief in the importance that family should care for their own and is a necessary sacrifice undertaken by females in the family can create a yoke of obligation that is a large burden to bear, often resulting in stress and depression.

Views about aging

Various subgroups within the Hispanic population hold unique cultural beliefs and traditions. In the case of specific health conditions, older Hispanics experience a disproportionate burden of disease, injury, death, and disability in comparison to non-Hispanic White elders, who constitute the largest racial/ethnic population in the United States. In a study exploring experiences and perceptions of aging and cognitive decline across diverse racial and ethnic groups, it was discovered that the perspective of Latino participants differed from that of White individuals, African Americans, and physicians. While the latter groups tended to view aging negatively, expressing concerns about change and a diminished societal role, Latino participants focused on positive aspects. They emphasized unlimited opportunities for learning and the ability to pursue desires and wishes associated with one’s age. This contrast in viewpoints underscores the diverse perspectives on aging within various cultural groups [42]. In another study, researchers focused on an initial examination concentrating on the influence of family relationships on the cognitive function of the Hispanic older population in the United States. The findings of this study indicated that a more diverse family network and financial support from family members exhibit positive associations with cognitive function among Hispanic older adults. Notably, the number of individuals residing in the household and perceived support (both positive and negative) did not show significant associations. Importantly, these associations were more pronounced among Hispanic older women than men [43]. Similarly, Paige’s research on health beliefs regarding cognitive aging, cognitive health behaviors, help-seeking tendencies, and cognitive health self-efficacy among Hispanics revealed that cognitive health promotion was perceived as linked to a broader concept, encompassing safeguarding the physical brain, self-care, cognitive enrichment, and maintaining a positive mindset. Participants of the study reported a spectrum of perceived control over cognitive aging, along with various barriers to maintaining cognitive health [44].

While elders in Hispanic families are respected and the familial desire to care for them at home is strong, it is not always administered with the right motivations. A sense of obligation to perform the caregiving duties seems to cause stress and mental health woes among many caregivers.

Role of caregivers

Hispanic caregivers face a greater caregiving burden compared to their non-Hispanic counterparts, partly due to contextual factors such as obstacles in accessing healthcare, difficult employment conditions, lower education and income levels, immigration challenges, and minority stress. Spirituality could serve as a coping mechanism for Hispanic caregivers, potentially impacting their health-related quality of life by alleviating the loneliness associated with caregiving [45]. The concept of caregiving is deeply ingrained in Hispanic culture, primarily due to the value of familism. Familism places a greater emphasis on the family unit, prioritizing respect, support, and obligation to the family over individual concerns [46]. Persistent stress resulting from caregiving has been associated with adverse health outcomes, increased morbidity, and higher mortality rates [47]. It is crucial to address and alleviate caregiver stress to ensure the well-being of family caregivers. While evidence-based caregiver intervention programs have shown positive outcomes in enhancing caregiver well-being and reducing stress [48], there is a lack of interventions that specifically incorporate cultural tailoring [49].

Nativity, referring to the country of birth, holds particular significance for Mexican-origin caregivers as it indicates potentially distinct social backgrounds and cultural teachings related to the caregiver role. Previous research substantiates this notion, demonstrating variations in health, health behavior, and family formation among Latinos based on nativity or generational status [50]. From a cultural psychological perspective, the tendency of Latina daughters and daughters-in-law to assume caregiving roles within their families may be explained by the concept of symbolic inheritance in Latino culture [51]. Within Hispanic culture, there is an ingrained expectation that female family members prioritize the needs of the family, particularly the male members, over their wants and desires [52]. This cultural expectation, known as marianismo, is believed to shape certain culturally accepted behaviors while discouraging others, influencing the adoption of specific caregiving roles and practices [53–55]. Therefore, caregivers are overwhelmingly female in Hispanic culture.

The community maintains a patriarchal hierarchy and their views on familial roles are rigid. This may be a natural progression of the ideals of machismo (that men are strong and responsible for the financial support of the family) and marianismo, the female obligation in Hispanic cultures to sacrifice all for the good of the family and be the nurturer and caretaker for all. These traditional roles seem to be taking a toll on Hispanic women as studies indicate that female caregivers have more depression, anxiety, and poorer rates of overall life satisfaction than men [8]. More research needs to be undertaken to explore the cultural concepts behind this phenomenon.

CREATING CULTURAL AND LIFESTYLE AWARENESS ABOUT DEMENTIA

With the projected significant increase in the proportion of older adults in the United States in the upcoming decades, it becomes imperative for public health initiatives to focus on and preserve the cognitive health of this expanding demographic. Currently, more than 6 million Americans are living with AD and ADRD, a number expected to more than double by 2050. The public health community needs to proactively outline a response to this escalating crisis. Essential components of this response include promoting risk reduction for cognitive decline, early detection, and diagnosis, and enhancing the utilization and accessibility of timely data [56]. There are numerous modifiable risk factors throughout life that can reduce the prevalence of dementia, and public awareness of these factors is growing. However, dementia is often misconstrued and stigmatized, and the prevention of dementia is not widely acknowledged as a health priority. Current shortcomings in public health campaigns for dementia prevention need to be addressed, and innovative alternatives must be developed to enhance public understanding and encourage the implementation of preventive measures at all stages of life [57]. Increasing dementia awareness is vital for early detection, reducing stigma, and fostering understanding and empathy within communities. This heightened awareness empowers caregivers, facilitates access to crucial resources, and promotes community readiness to support individuals living with dementia. Additionally, it can spur increased research funding and efforts toward finding effective treatments and ultimately a cure, refer to Fig. 3.

Fig. 3

Raising Awareness of Dementia. By addressing language barriers in the healthcare system, fostering community participation, educating individuals on the role of nutrition in preventing dementia, enhancing access to healthcare, empowering community advocacy, encouraging affected individuals and families to become advocates for change, promoting collaborations among government agencies, non-profit organizations, academia, and healthcare providers, and endorsing healthy lifestyle choices, we can effectively raise awareness about dementia and its prevention in the Hispanic community.

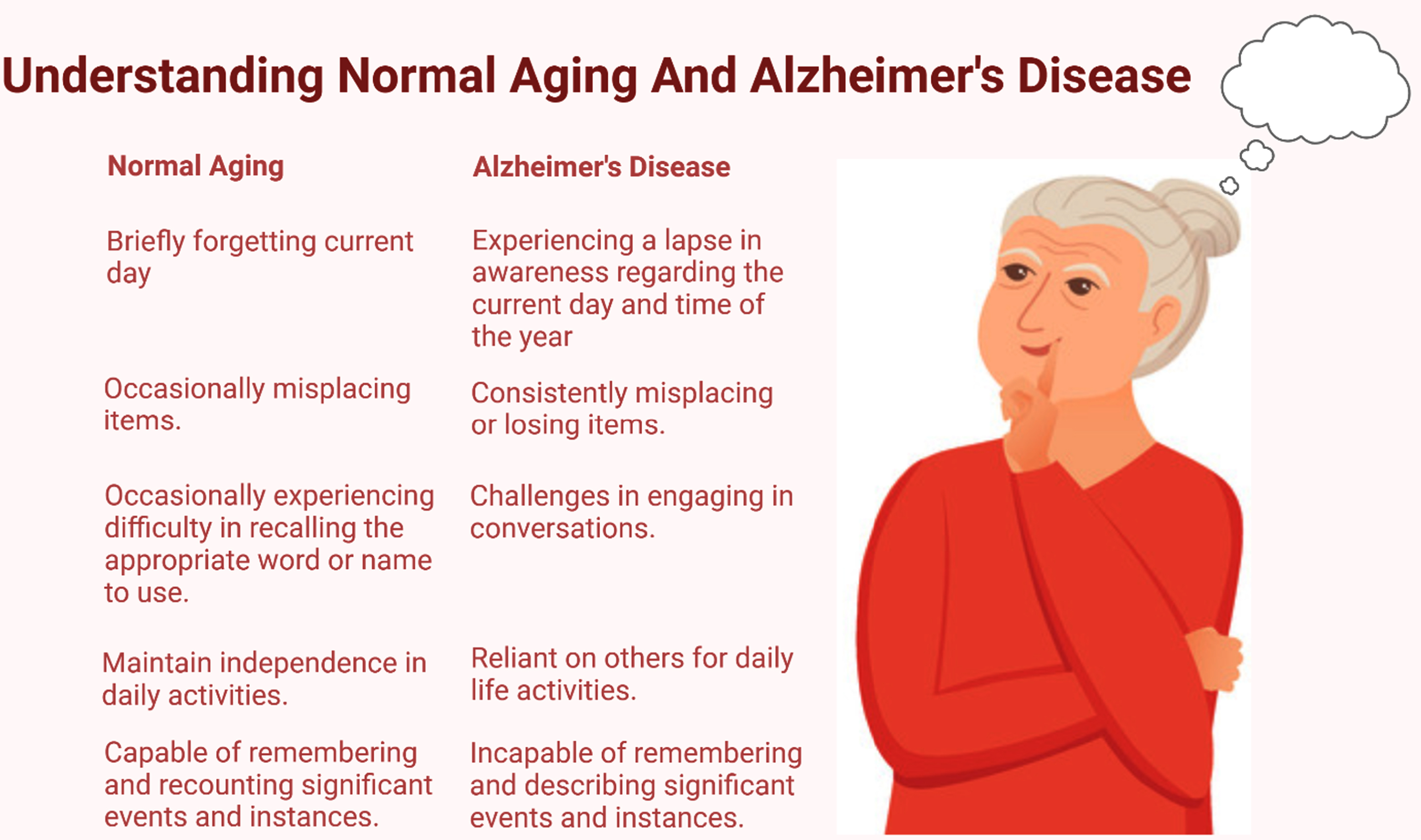

According to the World Health Organization, people worldwide who have dementia, along with their caregivers and families, continue to face stigma, discrimination, and violations of human rights. Additionally, dementia is often wrongly perceived as a natural and unavoidable aspect of aging, refer to Fig. 4. To counter these misconceptions and stereotypes, the initial step involves providing accurate information to enhance public comprehension of dementia. The Global Dementia Action Plan of the World Health Organization acknowledges this issue by dedicating one action area to enhancing public awareness, acceptance, and understanding of dementia. It establishes global targets, aiming to implement at least one functional public awareness campaign on dementia in 100% of countries and initiate at least one dementia-friendly initiative in 50% of countries to promote a society inclusive of individuals with dementia.

Fig. 4

Understanding the difference between normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease involves significant cognitive decline beyond typical age-related changes. Understanding these differences allows for early detection and intervention, enabling individuals to access appropriate care and support.

Taking into consideration the genuine needs and concerns of individuals in Hispanic populations, particularly affected by dementia and their caregivers, we propose the following actions to enhance awareness about dementia:

Language and communication

While the United States is a multicultural and multilingual society, the healthcare system is predominantly oriented toward serving English speakers [58]. There is a widely held belief that when a patient cannot communicate in the same language as their healthcare provider, it may lead to several adverse effects on the patient’s healthcare [59, 60]. The challenge of the language barrier is further complicated by the absence of effective systems in many providers and institutions to address language barriers when they arise. Commonly employed strategies, such as relying on untrained individuals like family members for interpretation, come with ethical risks and potential inaccuracies [59, 61, 62]. However, despite the likely connection between a language barrier and suboptimal healthcare, the specific impact of language on the healthcare of non-English speakers remains poorly understood [63].

Among Hispanic elderly, there is often a language barrier that exists between themselves and medical providers. Even if the language is translated into Spanish, there is still a divide and lack of understanding of medical concepts that are not known or understood. Additionally, it has been found that a mistake that many medical providers make is a lack of using the correct formal tone and even language specifics when addressing Hispanic elders. The elderly are well respected in their culture and yet often find that those outside of the community do not use formal language as is their preference for “outsiders.”

Strategies to overcome language barriers in healthcare, enhance communication, and improve healthcare outcomes may involve healthcare organizations providing written materials in multiple languages, offering multicultural training to healthcare providers, considering the expansion of Spanish proficiency among healthcare providers, and hiring qualified interpreters and translators. Additionally, implementing bilingual medical documentation, such as electronic health records accessible to non-English speakers, can play a crucial role in breaking down language barriers in healthcare. However, to foster awareness of dementia and encourage early detection of neurodegenerative diseases within the Hispanic population, it is crucial to implement culturally tailored strategies. Develop culturally sensitive materials in Spanish, disseminate information through Spanish-language media, and conduct community outreach programs in Hispanic neighborhoods. Collaborate with community leaders and influencers, utilize Spanish in healthcare settings, and establish Spanish-speaking support groups. Additionally, promotes regular health check-ups and screenings, provides telehealth services in Spanish, and trains healthcare professionals on cultural competence. These efforts aim to bridge language and cultural gaps, ensuring that the Hispanic community receives information in a relatable manner, fostering awareness, and promoting early detection and intervention for neurodegenerative diseases.

Community engagement

Although there is evidence indicating that Hispanic/Latino populations are 1.5 times more susceptible to developing ADRD compared to non-Hispanic Whites, there is an underrepresentation of Hispanics in clinical trials assessing treatments for ADRD. It is essential to gather data on the factors that facilitate participation in ADRD clinical trials among Hispanics. Enhancing the representation of Hispanic communities in clinical trials for AD/ADRD necessitates improved dissemination of bilingual information and education about AD/ADRD and clinical trials. Collaboration with trusted local, regional, and national organizations can play a crucial role in increasing participation. Moreover, the involvement of Hispanics in research efforts is likely to rise when research teams demonstrate altruistic actions and effectively inform participants about the public health reasons that necessitate their engagement [15].

The familism so strong among Hispanics leads to a reluctance to participate a great deal in engaging with other members of the community. Thus, it will benefit these efforts to develop strong collaborations with the community locations that elderly Hispanics frequent—primarily churches and medical facilities. Hispanics tend to be untrusting of information unless they receive it from a close personal contact. Word of mouth is by far the best way to influence them. Short of that, engaging with trusted community influencers might help spread messages and information effectively. Christy Martinez-Garcia is both the founder and publisher of the magazine Latino Lubbock as well as a City Council woman for the heavily Hispanic District 1, in the northeastern areas of Lubbock.

Partnering with community organizations is a highly recommended recruitment and retention tool for increasing participation in research studies by minorities. Another recommendation is to improve the retention of research staff in these culturally relevant research programs. Continuity of personnel tends to increase comfort level, trust, and continued participation in studies [14].

Community engagement is a vital strategy for raising awareness of dementia within the Hispanic population. This approach enables the development of culturally sensitive initiatives tailored to the specific needs and preferences of the community. Through active collaboration with local leaders, influencers, and organizations, trust and credibility are established, facilitating the dissemination of information about dementia. Community workshops, events, and partnerships with healthcare providers enhance direct interaction and the delivery of relevant information. By utilizing familiar community spaces and emphasizing a family-centered approach, community engagement ensures that messaging and materials are relatable and culturally appropriate. Digital and social media campaigns further extend the reach of dementia awareness initiatives. Overall, involving the Hispanic community actively fosters a more inclusive and culturally relevant approach, contributing to increased awareness, early detection, and better support for those affected by dementia and their families.

Nutrition and dementia

They fear being mocked, particularly for their poor traditional diet which is high in carbohydrates and fat. There is also a high reliance on fast food in the modern Hispanic culture. Recently, there has been a growing focus on the potential to positively impact cognitive trajectories by promoting lifestyle modifications. Among these, the connection between nutritional habits and cognitive health has garnered significant attention. Nutrition emerges as a pivotal factor in both the onset and prognosis of dementia, representing a crucial aspect of lifestyle modifications in strategies aimed at combating the condition [64]. The exploration of delaying or preventing dementia through nutritional and dietary habits has gained prominence. Consistent with existing epidemiological evidence, various nutritional compounds and regimens have demonstrated significant cognitive benefits in older individuals participating in placebo-controlled studies. This emphasizes the potential role of nutrition in influencing cognitive well-being and underscores the importance of ongoing research in this area [65]. Numerous studies have documented the impact of various foods on cognitive health, for instance, foods rich in dietary fibers play a role in delaying atherosclerosis by reducing cholesterol absorption, consequently contributing to the postponement of vascular aspects associated with dementia, whereas saturated fatty acids, by elevating LDL cholesterol levels, contribute to the promotion of atherosclerosis, subsequently influencing vascular aspects associated with dementia [65]. Additionally, these fatty acids can increase insulin resistance, potentially leading to the development of type II diabetes [66]. Individuals who predominantly consume diets high in sugar, saturated fat/trans fat, and lacking sufficient fiber and vitamins, experience more significant cognitive decline. In contrast, Mediterranean diets, characterized by high consumption of fruits, vegetables, fiber, polyphenols, and omega-3 fatty acids, appear to be linked with a lower incidence of dementia and reduced cognitive decline in both dementia and old age. Considering the cumulative and long-term effects of poor diets, transitioning to a Mediterranean diet earlier in life is advisable for cognitive health [67]. In a cohort study involving 6,321 Hispanic/Latino adults, strong adherence to the Mediterranean diet was linked to improved global cognition and a reduced decline in learning and memory over 7 years, as compared to low adherence to the diet. These findings suggest that adopting a culturally tailored Mediterranean diet may contribute to a lowered risk of cognitive decline and AD among middle-aged and older adults of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity [68].

To foster healthy eating habits within the Hispanic population and reduce the risk of dementia, a multifaceted approach can be implemented. This involves developing culturally tailored nutrition education materials and organizing community workshops and cooking classes that showcase the preparation of healthy, culturally relevant dishes. Collaboration with local Hispanic grocery stores and markets can promote and display nutritious food options, while health screenings with nutritional counseling sessions can provide personalized guidance. Engaging community influencers, such as local leaders and healthcare professionals, can effectively communicate the importance of healthy eating. Utilizing social media platforms popular within the Hispanic community for campaigns, celebrating cultural festivals with healthy foods, and offering incentives for adopting and maintaining healthy habits are additional strategies. A family-centered approach, peer support groups, and long-term educational programs can create a supportive environment for embracing a brain-healthy diet. Addressing economic barriers and advocating for access to affordable, healthy foods further contributes to the success of these initiatives, emphasizing the cultural connection between dietary choices and overall well-being.

Access to care and support services

The challenges faced by Hispanics, such as lower average income and educational attainment, pose obstacles to accessing timely and suitable healthcare. Individuals with lower incomes may struggle to afford out-of-pocket expenses, even with health insurance coverage. Additionally, limited education can hinder one’s ability to navigate the intricate healthcare delivery system, communicate effectively with healthcare providers, and comprehend their instructions. The association between Hispanics’ lower incomes and occupational characteristics further contributes to lower rates of health insurance coverage. The absence of health insurance emerges as a critical barrier, rendering the costs of healthcare services prohibitive for many individuals and significantly impeding adequate healthcare access [69]. Oh and colleagues proposed that Hispanics stand to gain significant benefits from the implementation of policies aimed at expanding health insurance coverage, addressing linguistic barriers, fostering an inclusive healthcare environment for patients, minimizing mobility barriers to seeking care, increasing the number of primary care physicians (PCPs), and providing training for additional Spanish-speaking PCPs [70]. The existing literature suggests that individuals of African American and Hispanic descent residing in rural areas may experience limited access to medical services, lower rates of health insurance coverage, and fewer visits to physicians when compared to urban residents or rural individuals who are not of Hispanic or African American origin [71]. We propose identifying and addressing barriers to accessing dementia care and support services in rural and underserved areas. And to enhance outreach efforts to ensure that individuals and families affected by dementia can access the resources they need.

Promoting healthy lifestyles

Various preventive factors, encompassing lifestyle behaviors and cardiovascular conditions, have been identified, each independently contributing to a reduced risk of cognitive decline and AD [72, 73]. These factors, including diet and exercise, are likely to have synergistic effects on dementia risk. Implementing behavioral prevention strategies can play a crucial role in sustaining high levels of cognition and functional integrity, thereby reducing the social, medical, and economic burdens linked to cognitive aging and age-associated neurodegenerative diseases. Interventions that incorporate physical exercise and cognitive training have consistently demonstrated positive effects on cognition in older adults [74]. Engaging in physical activity and maintaining a healthy diet are integral aspects of people’s lifestyles. Currently, numerous research studies demonstrate that physical activity can serve as an effective intervention in delaying cognitive decline in AD [75].

Our goal is to encourage a mindset shift among the Hispanic population, emphasizing that even small, healthy lifestyle changes can significantly reduce the risk of AD. This involves promoting an active lifestyle, advocating for smoking cessation, abstaining from alcohol, and actively managing blood pressure and blood glucose levels. Through these achievable lifestyle modifications, we aim to empower the Hispanic population to proactively enhance their brain health and minimize the risk of AD. Thus, promoting healthy lifestyle choices and risk reduction strategies to prevent or manage co-morbidities associated with dementia, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression is important. Moreover, encourages physical activity, nutritious eating, and social engagement tailored to the local context.

Cultural sensitivity in healthcare settings

Culture exerts its influence across various aspects of human existence, shaping perceptions of health, illness, and the pursuit of remedies for ailments or distress. The rise in global mobility has led to the emergence of multicultural trends worldwide, evident in the diverse cultural backgrounds encountered by healthcare professionals in their routine encounters. In these interactions, patients introduce their unique worldviews, expectations, norms, and taboos to the clinical setting, giving rise to cross-cultural transactions whenever participants hold distinct cultural backgrounds [76]. Providing cultural competency training for healthcare professionals is vital to enhance their understanding of diverse cultural beliefs and practices related to dementia care. There is a dire need to foster an environment of respect and empathy in healthcare settings to better serve patients and families.

Poverty, absence of insurance, legal status, and minority status pose barriers to healthcare access among Hispanics. Research has pinpointed elements of Hispanic culture, values, and traditions that shape the dynamics of the patient-doctor relationship and impact the quality of healthcare services. Despite ongoing educational initiatives by nonprofit organizations, the government, healthcare professionals, and pharmaceutical manufacturers, there remains a gap in addressing the specific need for readily available and culturally sensitive information tailored to the diverse Hispanic community. Recognizing Hispanics’ consumption practices and expectations concerning medications is essential for the effectiveness of various treatment plans [77]. Similarly, culturally sensitive approaches are crucial to raising dementia awareness in the Hispanic population, fostering understanding, and bridging gaps in healthcare. Tailoring information and outreach to align with Hispanic cultural nuances ensures a more effective and inclusive strategy for dementia education and support.

Empowering community advocacy

Another very effective strategy to raise awareness of mental illnesses and comorbidities is to empower individuals and families affected by dementia to become advocates for change in their communities. Support grassroots initiatives that aim to raise awareness, reduce stigma, and improve access to dementia care and support services. The stigma associated with dementia diagnosis, akin to other mental disorders, stems from cultural beliefs on its origins and the unsocial behaviors linked to cognitive impairment. This stigma not only impacts self-esteem and induces distress but also hinders social inclusion and may postpone the identification of dementia [78]. Individuals grappling with dementia can play a pivotal role in dismantling stigmas by sharing their experiences openly, fostering understanding, and actively engaging in conversations about dementia. Their narratives contribute significantly to raising awareness and dispelling misconceptions surrounding the condition.

Continued collaboration and evaluation

Fostering ongoing collaboration among stakeholders, including government agencies, non-profit organizations, academia, and healthcare providers, is the key to addressing the involving needs of the community. Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of awareness initiatives and adjust strategies as needed to ensure meaningful impact.

In the past years, there has been substantial legislative activity at the state level in the United States regarding immigration and immigrants. While certain policies seek to enhance access to education, transportation, benefits, and other services, others impose limitations. Despite the intrinsic connection between social and economic policies and health outcomes, there is a notable scarcity of research exploring the impact of state-level immigration-related policies on Hispanic health from social determinants of health perspective [79]. The economic and social factors influencing immigrant health may vary between undocumented and documented immigrants. Three key mechanisms shaping these differences are healthcare accessibility, access to health-protective resources (including social, economic, and political contributors), and immigration enforcement actions. However, within the Latino/Hispanic population, social factors within these mechanisms have distinct impacts on undocumented immigrants [80]. Recognizing the complexity of healthcare disparities, it is crucial to comprehend the risk factors affecting the overall health of the elderly Hispanic population and emphasize efforts to address them. Establishing collaborations among stakeholders and implementing interventions aligned with the various levels of the social structure of Hispanics can effectively work towards diminishing and eventually eradicating the inequalities in healthcare access for Hispanic communities throughout the United States.

The role of acculturation in the Hispanic community

Since health-related challenges pose a risk to Hispanic Americans, marked by disparities in conditions like diabetes and obesity, limited access to health services, and insufficient health insurance coverage, placing them at a disadvantage. Further exploration is needed to understand the impact of sociocultural factors, particularly acculturation, on the health of Hispanic Americans [81]. In a recent study, the impact of acculturation on cognition was investigated in 142 older Hispanics categorized into cognitively normal, mild cognitive impairment, amnestic, and dementia groups. Acculturation levels were identified using the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics, distinguishing between high and low acculturation. The analysis, controlling for age and education, revealed that highly acculturated cognitively normal individuals performed better on various neuropsychological tests. This association suggested that high acculturation correlated with improved performance in episodic memory, auditory attention, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and processing speed among cognitively normal Hispanics [82]. While it appears to most outsiders that Hispanic culture is still strong, we may see in the upcoming generations a distancing from these outdated concepts as longer periods of acculturation is making these long-held beliefs less important. Lower levels of familism are predicted as generations become further distanced from their heritage and traditional influencing factors [39]. Richardson et al. also found acculturation to be impacting current care and caregiving roles [10].

AWARENESS CAMPAIGN

To alleviate the escalating public health burden of dementia, there is a critical need for strategies aimed at reducing the risk of this condition. Unfortunately, many individuals lack awareness regarding the possibility of dementia risk reduction and the means to achieve it. Addressing this gap through health education, particularly through public awareness campaigns focused on dementia risk reduction, can play a crucial role in disseminating essential information [83]. A study by Askari and colleagues aimed to design an educational program on AD and dementia for Promotoras linked to a local community education and health advocacy group. This initiative seeks to increase awareness and knowledge about dementia specifically among individuals of Hispanic/Latino heritage. The strategy involves educating the Latino population about dementia, fostering trust, and encouraging early detection and treatment, utilizing the Community-Based Participatory Research model for effective educational campaigns [84].

The Alzheimer’s Association has launched a fresh campaign aimed at increasing awareness of the disease within Hispanic communities. Named “Some Things Come with Age,” the campaign was unveiled during the last week of Hispanic Heritage Month on September 15, 2023. It offers online bilingual resources, including a list of warning signs such as disruptive memory loss, challenges in completing routine tasks, and difficulty retracing steps. The objective is to empower families to identify these signs early on and facilitate medical access to slow the progression of AD. We need more initiatives like this to promote awareness of mental health among different communities across the United States.

We propose initiative involves partnering with local Hispanic markets such as flea markets, Hispanic grocery stores, local radio stations, and newspapers, utilizing social media platforms. The aim is to motivate Hispanic communities to distinguish between normal aging and early signs of AD. Through our campaigns and community reach out we seek to dispel fatalistic views about neurodegenerative diseases and associated comorbidities, challenge misconceptions and stigmas, and highlight the transformative potential of research and participation in research in advancing breakthroughs for individuals affected by dementia.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

AD stands as the most prevalent form of dementia, characterized by a progressive onset involving mild memory loss and potential escalation to an inability to engage in conversations or respond to the environment, affecting areas of the brain related to thought, memory, and language. Despite being almost twice as likely to receive an AD diagnosis compared to white Americans, the actual prevalence among Hispanics may surpass these statistics due to cultural factors, making caregiving a significant responsibility in Hispanic culture. The reluctance to seek help or discuss concerns about dementia within the community is influenced by cultural norms, as older adults may perceive mental disorders as weaknesses, contributing to the stigma. This critical juncture underscores the importance of informed caregivers who can navigate conversations about dementia and/or AD, removing the associated stigma.

Our paper highlights the dire needs of the Hispanic population, where the desire to understand dementia and its comorbidities and engage in research coexists with limited awareness and opportunities.

To enhance Hispanic representation in research, local organizations must extend simultaneous invitations, and public health messages, tailored to cultural values, are essential for encouraging early dementia detection. As the older American population becomes more diverse, our paper suggests culturally tailored AD awareness campaigns not only for Hispanic communities but also for other ethnic groups to promote brain health.

Although so much research has been done on dementia and AD awareness in general, still we are unable to create effective awareness among Hispanics and other minorities in the US and around the globe. As discussed in our article, the current challenges remain the same such as language & cultural barriers, low socioeconomic status, limited knowledge/education, religious/spiritual beliefs and not accepting modern medicine/healthcare facilities. Further, mental and physical health issues of caregivers who are living with dementia and AD patients.

Most importantly, as we discussed possible measures need to be taken by local, state, and federal agencies to create awareness about dementia, including empowering community advocacy, promoting healthy lifestyle choices, education on the impact of nutrition, encouraging community participation, and continued collaboration and evaluation of the success of dementia awareness.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Malcolm Brownell (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review & Editing); Ujala Sehar (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review & Editing); Upasana Mukherjee (Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review & Editing); Hemachandra Reddy (Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review & Editing).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no acknowledgments to report.

FUNDING

The research and relevant findings presented in this article were supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant, AG079264.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

[1] | van Kooten J , Binnekade TT , Van Der Wouden JC , Stek ML , Scherder EJ , Husebø BS , Smalbrugge M , Hertogh CM ((2016) ) A review of pain prevalence in Alzheimer’s, vascular, frontotemporal and Lewy body dementias. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 41: , 220–232. |

[2] | Maloney B , Lahiri DK ((2016) ) Epigenetics of dementia: Understanding the disease as a transformation rather than a state. Lancet Neurol 15: , 760–774. |

[3] | Farlow M , Lahiri D , Poirier J , Davignon J , Schneider L , Hui S ((1998) ) Treatment outcome of tacrine therapy depends on apolipoprotein genotype and gender of the subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 50: , 669–677. |

[4] | Lahiri DK , Maloney B ((2010) ) The “LEARn”(Latent Early-life Associated Regulation) model integrates environmental risk factors and the developmental basis of Alzheimer’s disease, and proposes remedial steps. Exp Gerontol 45: , 291–296. |

[5] | Corrigan PW , Watson AC ((2002) ) Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 1: , 16. |

[6] | Farina N , Hughes LJ , Jones E , Parveen S , Griffiths AW , Galvin K , Banerjee S ((2020) ) The effect of a dementia awareness class on changing dementia attitudes in adolescents. BMC Geriatr 20: , 188. |

[7] | World Health Organization Organization (2012) Dementia: A public health priority, World Health Organization. |

[8] | Sehar U , Rawat P , Choudhury M , Boles A , Culberson J , Khan H , Malhotra K , Basu T , Reddy PH ((2023) ) Comprehensive understanding of Hispanic caregivers: Focus on innovative methods and validations. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 7: , 557–574. |

[9] | Nichols E , Steinmetz JD , Vollset SE , Fukutaki K , Chalek J , Abd-Allah F , Abdoli A , Abualhasan A , Abu-Gharbieh E , Akram TT ((2022) ) Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7: , e105–e125. |

[10] | Richardson VE , Fields N , Won S , Bradley E , Gibson A , Rivera G , Holmes SD ((2019) ) At the intersection of culture: Ethnically diverse dementia caregivers’ service use. Dementia 18: , 1790–1809. |

[11] | Mudrazija S , Ayala SG ((2024) ) Public benefits use for Hispanic and non-Hispanic older immigrants in the United States. Public Policy Aging Rep 34: , 31–33. |

[12] | Antequera F , Rote S , Cantu P , Angel J ((2024) ) Paying the price: The cost of caregiving for older Latinos enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. Public Policy Aging Rep 34: , 18–21. |

[13] | Vega IE , Cabrera LY , Wygant CM , Velez-Ortiz D , Counts SE ((2017) ) Alzheimer’s disease in the Latino community: Intersection of genetics and social determinants of health. J Alzheimers Dis 58: , 979–992. |

[14] | George S , Duran N , Norris K ((2014) ) A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health 104: , e16–e31. |

[15] | Marquez DX , Perez A , Johnson JK , Jaldin M , Pinto J , Keiser S , Tran T , Martinez P , Guerrero J , Portacolone E ((2022) ) Increasing engagement of Hispanics/Latinos in clinical trials on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 8: , e12331. |

[16] | World Health Organization (2020) Decade of healthy ageing: Plan of action. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. |

[17] | McNeal MG , Zareparsi S , Camicioli R , Dame A , Howieson D , Quinn J , Ball M , Kaye J , Payami H ((2001) ) Predictors of healthy brain aging. , . J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 56: , B294–B301. |

[18] | Gable SC , O’Connor MK (2020) Treating medical comorbidities associated with dementia among Latinos. In Caring for Latinxs with Dementia in a Globalized World: Behavioral and Psychosocial Treatments, pp. 69-89. |

[19] | Robbins NM , Bernat JL ((2017) ) Minority representation in migraine treatment trials. Headache 57: , 525–533. |

[20] | Burneo JG , Martin R ((2004) ) Reporting race/ethnicity in epilepsy clinical trials. Epilepsy Behav 5: , 743–745. |

[21] | Zhang Y , Ornelas IJ , Do HH , Magarati M , Jackson JC , Taylor VM ((2017) ) Provider perspectives on promoting cervical cancer screening among refugee women. J Community Health 42: , 583–590. |

[22] | Vyas MV , Raval PK , Watt JA , Tang-Wai DF ((2018) ) Representation of ethnic groups in dementia trials: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci 394: , 107–111. |

[23] | Aranda MP , Marquez DX , Gallagher-Thompson D , Pérez A , Rojas JC , Hill CV , Reyes Y , Dilworth-Anderson P , Portacolone E ((2023) ) A call to address structural barriers to Hispanic/Latino representation in clinical trials on Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: A micro-meso-macro perspective. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 9: , e12389. |

[24] | Sheladia S , Reddy PH ((2021) ) Age-related chronic diseases and Alzheimer’s disease in Texas: A Hispanic focused study. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 5: , 121–133. |

[25] | Fernandez J , García-Pérez M , Orozco-Aleman S ((2023) ) Unraveling the Hispanic health paradox. J Econ Perspect 37: , 145–167. |

[26] | De Mooij M (2019) Consumer behavior and culture: Consequences for global marketing and advertising. In Consumer Behavior and Culture, SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 1-472. |

[27] | Hofstede G ((1980) ) Culture and organizations. Int Stud Manag Organ 10: , 15–41. |

[28] | Janevic MR , M Connell C ((2001) ) Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in the dementia caregiving experience: Recent findings. Gerontologist 41: , 334–347. |

[29] | Brijnath B , Navarro Medel C , Antoniades J , Gilbert AS ((2023) ) Culturally adapting evidence on dementia prevention for ethnically diverse communities: Lessons learnt from co-design. Clin Gerontol 46: , 155–167. |

[30] | Britt KC , Richards KC , Acton G , Radhakrishnan K , Hamilton J ((2023) ) Impact of religious and spiritual activity on risk of dementia and cognitive impairment with differences across race/ethnicity and sex. JASNH 20: , 19–26. |

[31] | Krause N , Bastida E ((2012) ) Religion and health among older Mexican Americans: Exploring the influence of making mandas. J Relig Health 51: , 812–824. |

[32] | Schieman S , Pudrovska T , Pearlin LI , Ellison CG ((2006) ) The sense of divine control and psychological distress: Variations across race and socioeconomic status. J Sci Study Religion 45: , 529–549. |

[33] | Nguyen AW ((2020) ) Religion and mental health in racial and ethnic minority populations: A review of the literature. Innov Aging 4: , igaa035. |

[34] | Quiroz YT , Solis M , Aranda MP , Arbaje AI , Arroyo-Miranda M , Cabrera LY , Carrasquillo MM , Corrada MM , Crivelli L , Diminich ED ((2022) ) Addressing the disparities in dementia risk, early detection and care in Latino populations: Highlights from the second Latinos & Alzheimer’s Symposium. Alzheimers Dement 18: , 1677–1686. |

[35] | Cabrera LY , Kelly P , Vega I ((2021) ) Knowledge and attitudes of two latino groups about alzheimer disease: A qualitative study. J Cross Cult Gerontol 36: , 265–284. |

[36] | Mehta KM , Yeo GW ((2017) ) Systematic review of dementia prevalence and incidence in United States race/ethnic populations. Alzheimers Dement 13: , 72–83. |

[37] | Arana M ((2001) ) The elusive Hispanic/Latino identity. Nieman Rep 55: , 8. |

[38] | Knight BG , Sayegh P ((2010) ) Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 65: , 5–13. |

[39] | Falzarano F , Moxley J , Pillemer K , Czaja SJ ((2022) ) Family matters: Cross-cultural differences in familism and caregiving outcomes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 77: , 1269–1279. |

[40] | Almeida J , Molnar BE , Kawachi I , Subramanian S ((2009) ) Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Soc Sci Med 68: , 1852–1858. |

[41] | Crist JD , Speaks P ((2011) ) Keeping it in the family: When Mexican American older adults choose not to use home healthcare services. Home Healthc Now 29: , 282–290. |

[42] | Roberts LR , Schuh H , Sherzai D , Belliard JC , Montgomery SB ((2015) ) Exploring experiences and perceptions of aging and cognitive decline across diverse racial and ethnic groups. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 1: , 2333721415596101. |

[43] | Xiao C , Mao S , Jia S , Lu N ((2021) ) Research on family relationship and cognitive function among older Hispanic Americans: Empirical evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Hisp J Behav Sci 43: , 95–113. |

[44] | Paige A (2022) Health beliefs about cognitive aging, cognitive health behaviors, help-seeking, and cognitive health self-efficacy among Hispanic/Latino/x Older Adults. Dissertation. Pacific University Oregon. |

[45] | King JJ , Badger TA , Segrin C , Thomson CA ((2024) ) Loneliness, spirituality, and health-related quality of life in hispanic english-speaking cancer caregivers: A qualitative approach. J Relig Health 63: , 1433–1456. |

[46] | Adams B , Aranda MP , Kemp B , Takagi K ((2002) ) Ethnic and gender differences in distress among Anglo American, African American, Japanese American, and Mexican American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. J Clin Geropsychol 8: , 279–301. |

[47] | Gouin J-P ((2011) ) Chronic stress, immune dysregulation, and health. Am J Lifestyle Med 5: , 476–485. |

[48] | Elliott AF , Burgio LD , DeCoster J ((2010) ) Enhancing caregiver health: Findings from the resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s caregiver health II intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: , 30–37. |

[49] | Pharr JR , Dodge Francis C , Terry C , Clark MC ((2014) ) Culture, caregiving, and health: Exploring the influence of culture on family caregiver experiences. ISRN Public Health 2014: , 1–8. |

[50] | Lara M , Gamboa C , Kahramanian MI , Morales LS , Hayes Bautista DE ((2005) ) Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health 26: , 367–397. |

[51] | Harwood DG , Barker WW , Ownby RL , Bravo M , Aguero H , Duara R ((2000) ) Predictors of positive and negative appraisal among Cuban American caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 15: , 481–487. |

[52] | García B , De Oliveira O ((1997) ) Motherhood and extradomestic work in urban Mexico. Bull Latin Am Res 16: , 367–384. |

[53] | Mendez-Luck CA , Applewhite SR , Lara VE , Toyokawa N ((2016) ) The concept of familism in the lived experiences of Mexican-origin caregivers. J Marriage Fam 78: , 813–829. |

[54] | Mendez-Luck CA , Anthony KP ((2016) ) Marianismo and caregiving role beliefs among US-born and immigrant Mexican women . J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 71: , 926–935. |

[55] | McDermott E , Mendez-Luck CA ((2018) ) The processes of becoming a caregiver among Mexican-origin women: A cultural psychological perspective. Sage Open 8: , 2158244018771733. |

[56] | Olivari BS , French ME , McGuire LC ((2020) ) The public health road map to respond to the growing dementia crisis. Innov Aging 4: , igz043. |

[57] | Siette J , Dodds L , Catanzaro M , Allen S ((2023) ) To be or not to be: Arts-based approaches in public health messaging for dementia awareness and prevention. Australas J Ageing 42: , 769–779. |

[58] | Flores G ((2000) ) Culture and the patient-physician relationship: Achieving cultural competency in health care. J Pediatr 136: , 14–23. |

[59] | Tang SY ((1999) ) Interpreter services in healthcare: Policy recommendations for healthcare agencies. J Nurs Adm 29: , 23–29. |

[60] | Woloshin S , Bickell NA , Schwartz LM , Gany F , Welch HG ((1995) ) Language barriers in medicine in the United States. JAMA 273: , 724–728. |

[61] | Perkins J , Wong D , Youdelman M (2003) Ensuring Linguistic Access in Health Care Settings: Legal Right and Responsibilities, National Health Law Program. |

[62] | Torres RE ((1998) ) The pervading role of language on health. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 9: , S21–S25. |

[63] | Timmins CL ((2002) ) The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: A review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Womens Health 47: , 80–96. |

[64] | Gómez-Pinilla F ((2008) ) Brain foods: The effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci 9: , 568–578. |

[65] | Canevelli M , Lucchini F , Quarata F , Bruno G , Cesari M ((2016) ) Nutrition and dementia: Evidence for preventive approaches? . Nutrients 8: , 144. |

[66] | Boden G , Shulman G ((2002) ) Free fatty acids in obesity and type 2 diabetes: Defining their role in the development of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. Eur J Clin Invest 32: , 14–23. |

[67] | Valls-Pedret C , Sala-Vila A , Serra-Mir M , Corella D , De la Torre R , Martínez-González MÁ , Martínez-Lapiscina EH , Fitó M , Pérez-Heras A , Salas-Salvadó J ((2015) ) Mediterranean diet and age-related cognitive decline: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 175: , 1094–1103. |

[68] | Moustafa B , Trifan G , Isasi CR , Lipton RB , Sotres-Alvarez D , Cai J , Tarraf W , Stickel A , Mattei J , Talavera GA ((2022) ) Association of Mediterranean diet with cognitive decline among diverse hispanic or latino adults from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. JAMA Netw Open 5: , e2221982. |

[69] | Escarce JJ , Kapur K (2006) Access to and quality of health care, National Academies Press Washington, DC. |

[70] | Oh H , Trinh MP , Vang C , Becerra D ((2020) ) Addressing barriers to primary care access for Latinos in the US: An agent-based model. J Soc Soc Work Res 11: , 165–184. |

[71] | Caldwell JT , Ford CL , Wallace SP , Wang MC , Takahashi LM ((2016) ) Intersection of living in a rural versus urban area and race/ethnicity in explaining access to health care in the United States. Am J Public Health 106: , 1463–1469. |

[72] | Norton S , Matthews FE , Barnes DE , Yaffe K , Brayne C ((2014) ) Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 13: , 788–794. |

[73] | Ngandu T , Lehtisalo J , Solomon A , Levälahti E , Ahtiluoto S , Antikainen R , Bäckman L , Hänninen T , Jula A , Laatikainen T ((2015) ) A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 385: , 2255–2263. |

[74] | Smith GE ((2016) ) Healthy cognitive aging and dementia prevention. Am Psychol 71: , 268. |

[75] | Klimova B , Maresova P , Kuca K ((2019) ) Alzheimer’s disease: Physical activities as an effective intervention tool-a mini-review. Curr Alzheimer Res 16: , 166–171. |

[76] | Ayonrinde O ((2003) ) Importance of cultural sensitivity in therapeutic transactions: Considerations for healthcare providers. Dis Manag Health Out 11: , 233–248. |

[77] | Askim-Lovseth MK , Aldana A ((2010) ) Looking beyond “affordable” health care: Cultural understanding and sensitivity—Necessities in addressing the health care disparities of the US Hispanic population. Health Mark Q 27: , 354–387. |

[78] | Mukadam N , Livingston G ((2012) ) Reducing the stigma associated with dementia: Approaches and goals. Aging Health 8: , 377–386. |

[79] | Philbin MM , Flake M , Hatzenbuehler ML , Hirsch JS ((2018) ) State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med 199: , 29–38. |

[80] | Cabral J , Cuevas AG ((2020) ) Health inequities among latinos/hispanics: Documentation status as a determinant of health. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 7: , 874–879. |

[81] | Buscemi CP , Williams C , Tappen RM , Blais K ((2012) ) Acculturation and health status among Hispanic American elders. J Transcult Nurs 23: , 229–236. |

[82] | Mendoza L , Garcia P , Duara R , Rosselli M , Loewenstein D , Greig-Custo MT , Barker W , Dahlin P , Rodriguez MJ ((2022) ) The effect of acculturation on cognitive performance among older Hispanics in the United States. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 29: , 163–171. |

[83] | Van Asbroeck S , van Boxtel MP , Steyaert J , Köhler S , Heger I , de Vugt M , Verhey F , Deckers K ((2021) ) Increasing knowledge on dementia risk reduction in the general population: Results of a public awareness campaign. Prev Med 147: , 106522. |

[84] | Askari N , Bilbrey AC , Garcia Ruiz I , Humber MB , Gallagher-Thompson D ((2018) ) Dementia awareness campaign in the Latino community: A novel community engagement pilot training program with Promotoras. Clin Gerontol 41: , 200–208. |