Comprehensive Understanding of Hispanic Caregivers: Focus on Innovative Methods and Validations

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s disease-related disorders (ADRD) are late-onset, age-related progressive neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by memory loss and multiple cognitive impairments. Current research indicates that Hispanic Americans are at an increased risk for AD/ADRD and other chronic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and kidney disease, and given their rapid growth in numbers, this may contribute to a greater incidence of these disorders. This is particularly true for the state of Texas, where Hispanics are the largest group of ethnic minorities. Currently, AD/ADRD patients are taken care by family caregivers, which puts a tremendous burden on family caregivers who are usually older themselves. The management of disease and providing necessary/timely support for patients with AD/ADRD is a challenging task. Family caregivers support these individuals in completing basic physical needs, maintaining a safe living environment, and providing necessary planning for healthcare needs and end-of-life decisions for the remainder of the patient’s lifetime. Family caregivers are mostly over 50 years of age and provide all-day care for individuals with AD/ADRD, while also managing their health. This takes a significant toll on the caregiver’s own physiological, mental, behavioral, and social health, in addition to low economic status. The purpose of our article is to assess the status of Hispanic caregivers. We also focused on effective interventions for family caregivers of persons with AD/ADRD involving both educational and psychotherapeutic components, and a group format further enhances effectiveness. Our article discusses innovative methods and validations to support Hispanic family caregivers in rural West Texas.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s disease-related disorders (ADRD) are the most common cause of dementia among elderly individuals. AD refers to the pathological and morphological changes in the hippocampus and other areas of the cortex responsible for language, reasoning, and behavior changes that characterize the progression of the disease [1]. Significant clinical symptoms of AD include memory loss and multiple cognitive deficits [2]. About 6.5 million Americans are living with AD, and these numbers are predicted to reach 13.8 million by 2060, in the absence of a quantum leap development of medicine to prevent, slow, or cure AD [3]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it is the fifth leading cause of death for individuals aged 65 and over and a seventh leading cause of death for all adults. Between 2000–2019, the deaths reported due to AD increased by more than 145% while deaths from strokes, HIV, and heart disease decreased [3]. Much evidence suggests that a complex amalgamation of genetic and environmental factors leads to cognitive decline and the development of dementia [4]. The etiology of AD is unknown and involves the interaction of genes and environment, including diets and lifestyle [5]. However, the LEARn (latent-early life associated regulation) model attempts to explain the etiology of the most prevalent, sporadic, types of neurological illnesses by combining genetic and environmental risk factors in an epigenetic route [6, 7]. The health of Hispanics residing in Texas along the United States (US) and Mexico border may vary from those living in the US [8]. Communities with a higher number of Hispanic tend to have greater poverty, lower median incomes, less access to medical care, and smaller populations with high school or collegedegrees [9].

What is caregiving?

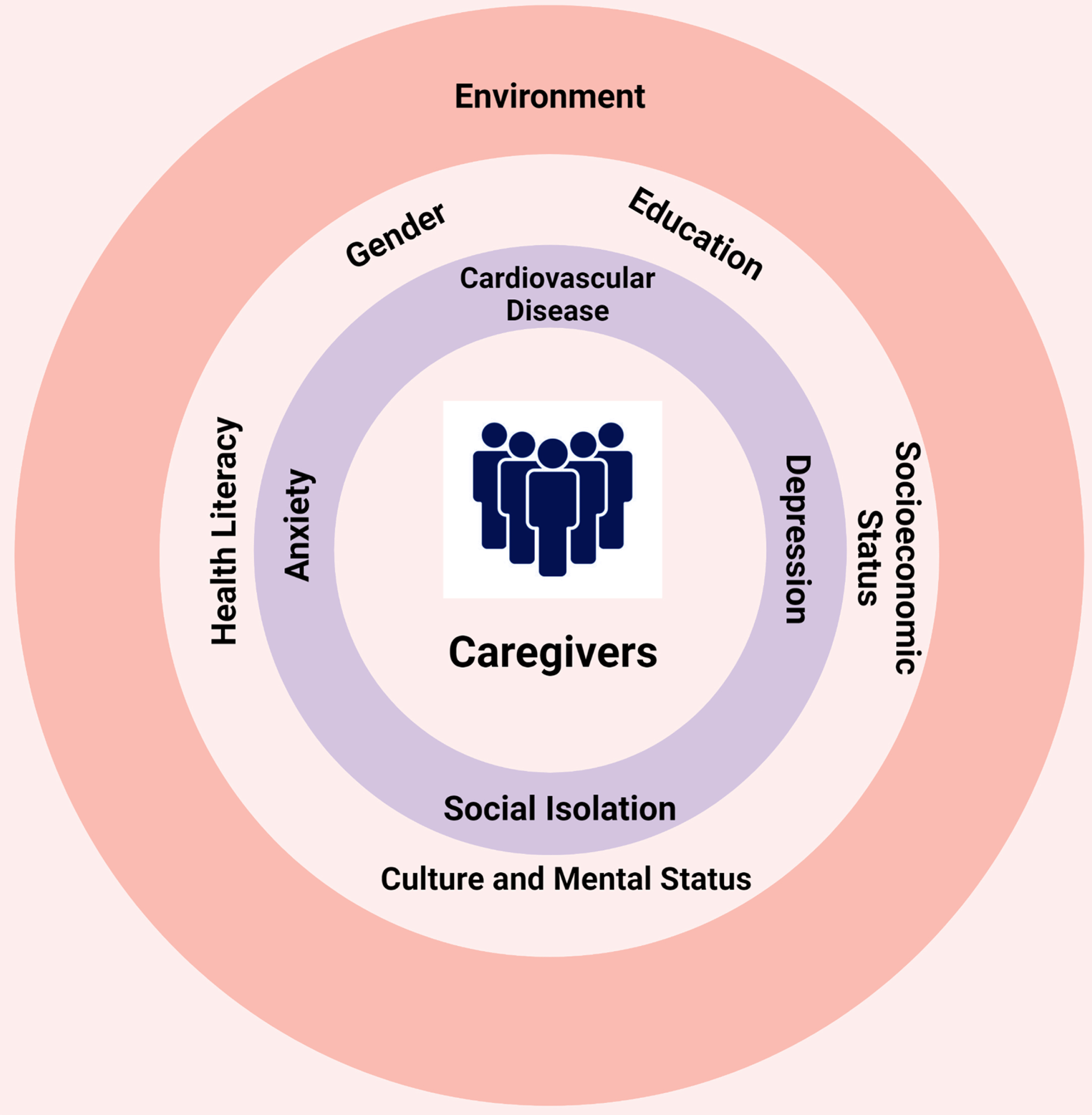

Fig. 1

Definition of a Caregiver. A caregiver can be anyone like family, children-in-law, parents, siblings, spouse, and friends who provide care to someone who needs extra care.

The caregiver refers to anyone who provides care to someone who needs extra care or help. The caregiver is a broad term; anyone could be a caregiver, a family person, a friend, a respite caregiver, or a primary caregiver (Fig. 1). AD and ADRD are those neurodegenerative diseases in which individuals cannot deal with routine functions and face cognitive impairment. In this condition, they need someone who can help them. In 2021, more than 11 million family members and other unpaid caregivers provided an estimated 16 billion hours of service care to people with AD or ADRD dementia. The value was estimated to be approximately $271.6 billion for unpaid dementia caregiving [3]. In 2022, AD and other dementia will cost the nation $321 billion; by 2050, this cost could reach $1 trillion [3]. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, approximately 13% of Hispanics aged 65 or over live with AD or another form of dementing illness. Much evidence suggests a remarkable difference exists in the prevalence, incidence, mortality, and treatment of AD among ethnic and racial groups in the US [10]. Due to the difference in pre-existing medical conditions, socioeconomic status, and social behaviors, minority populations such as Hispanic Americans show a greater risk of AD dementia and other types of dementia [11]. As the aging population increases, the demand for caregivers will gradually increase. Risk factors indicate that the future burden of AD will be disproportionally seen in individuals of specific racial backgrounds, such as Hispanic/Latino Americans [11, 12]. Caregiver burden and poor mental health in family caregivers result in adverse long-term effects [10], and research has also shown that it can negatively affect the person with AD/ADRD [13]. This review aims to identify the reason for the high number of informal caregivers in the Hispanic group and discusses a comprehensive understanding of the caregiver’s burden. We are also proposing innovative methods along with their validation to support caregivers. In this article, we have used the terms Latino and Hispanic interchangeably.

COMPREHENSIVE UNDERSTANDING OF CAREGIVERS IN AD AND ADRD

In 2022, Hispanic or Latino minority populations are projected to surpass non-Hispanic white as the majority population in Texas. Older Hispanic individuals are racially and ethnically heterogenous groups of people with widely different origins, migration history, cultural and traditional beliefs, economic and psychosocial status, language proficiency, and levels of acculturation to the dominant culture [14]. There are significant disparities among the racial and ethnic groups in Texas. The increased risk of developing AD and ADRD in Hispanic people is due to different socioeconomic factors and is often a frustrating experience for the people who are suffering and the individuals who are providing care to them. Other caregivers are classified based on their duties, such as family, independent, volunteer, informal, skilled nursing facility, etc. According to the report released by the US Census Bureau, Hispanics are the largest demographic group in Texas for the first time. As of July 1, 2021, an estimated 11.86 million Hispanic Texans comprise 40.2% of the Texas population and reflects a national demographic shift. The Hispanic population has increased by approximately three times that of the older black population since 2000 [15]. Research on racial and ethnic minorities in nursing homes found that between 1998–2008, the number of elderly nonwhite Hispanic individuals living in nursing homes increased by 54.9% due to a rapid growth in the older minority population [16]. Hispanic people face a lack of educational outreach, financial status, less access to medical facilities, linguistic barriers, and food habits (Fig. 2). The caregiver burden faced by this community is a significant issue in AD and ADRD clinical research [17]. Hispanic/ Latino people are at high risk of AD/ADRD, and therefore their disease often progress to require caregivers.

Fig. 2

Influence of different factors on caregiving. Many environmental, cultural, and socioeconomic factors influence the overall well-being of family caregivers.

According to the survey held by the AARP in 2020, one in five Hispanics/Latinos is providing informal care to an adult with a health issue or disability. 17% of family caregivers in the US are Hispanic/Latino. Due to poor socioeconomic status, lack of healthcare access, and cultural reasons, Hispanics opt for informal caregiving.

Rural versus urban

Texas is the second largest state in the US by area; however, its population is ranked twenty-sixth by population density [18, 19]. Houston, San Antonio, and Dallas are the most populous cities in Texas. According to a 2014 study, out of the 15 fastest-growing cities in the US, five are in East Texas [18]. The classification of any country or state as urban or rural depends on many factors. Texas presently has 82 urban counties, and 172 counties come under rural or non-metropolitan.

Rural West Texas is relatively less connected with the rest of the world. According to the Texas Almanac, rural Texas, along with food, fiber, and other manufacturing goods it exported, generated more than $21.2 billion for the state economy in 2019. If Texas cannot stabilize its rural communities, it will lose its place in the world economy.

Rural West Texas includes 108 counties and nearly 131,000 square miles of surface area or 50% of Texas’ overall surface area. [12]. Due to the immensely low population density all over this region, it is difficult for health industries to flourish in such areas [12]. Two dozen rural hospitals have shut down since 2005, and the community has no access to medical facilities. People in rural areas are poor and older, and fewer people can afford medical facilities. Texas has a very high rate of individuals who lack adequate health insurance, and in rural West Texas, the percentage of uninsured, and subsequent lack of access to healthcare is more extreme. Hispanic Americans are a significant population in rural West Texas [20]. The burden of AD/ADRD and other age-related chronic diseases is higher among Hispanic Americans as they are the majority group in this area [20]. More than 65 million Americans living in rural areas are above the age of 50 (US Department of Health and Human Service Rural Task Force). Older people from rural areas are more likely to reside alone, below or near the poverty line, and suffer from chronic disease (US Department of Health and Human Service Rural Task Force). An estimated 51% of caregivers in rural areas use population-based services [21]. Due to this overburden of AD and ADRD and the lack of medical facilities, the number of informal caregivers will gradually increase. Rural caregivers may be at increased risk of stress, and other medical conditions due to the relative isolation and reduced available support. This is linked to poorer psychological and health outcomes. Hispanic communities are more likely to underutilize health care services, and when received, they are usually low-quality care services [22].

Men versus women

Gender plays an essential role in caregiving. Gender may affect the understanding of caregiver burden [23]. Men and women report differences in their pattern of caregiver burden [24]. Men observed a lack of positive perspective and a need for social support, while women experienced increased caregiver burden in their relationship with family members and increased health issues [24]. In their comprehensive study, Yee and colleagues assumed that compared to men, women provide more time in caregiving [25]. They also found that most studies show that women caregivers experience a higher level of anxiety, depression, and other general psychiatric symptoms and lower levels of life satisfaction than male caregivers [25]. These findings were inconclusive as some studies demonstrated that women are less satisfied [26, 27], while other studies showed no difference in satisfaction levels among men and women caregivers [28, 29].

Despite both female and male Hispanics working hard over generations, the conventional image adversely affects them regarding caregiving. The typical traditional expectation of these communities is that women are responsible for caregiving. At the same time, men are responsible for machismo (to protect the honor and welfare of their families) and patriarchal authority [30]. 74% of Hispanic caregivers are female, and the majority of Hispanic caregiver recipients are female (57%) [31].

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status is well accepted social determinant of health. The inequity of socioeconomic status and cultural constructs among different communities may influence their risk perceptions, understanding, and knowledge of AD/ADRD. To test the consequences of significant and severe cultural deprivation, however, there would be no need to travel to other nations [32]. Extreme chemical exposures, economic hardship, and institutionalized deprivation are prevalent in many places in Canada and the US. For instance, Flint, Michigan, is in a nation that would be considered high income but given the community samples that McGill and colleagues analyzed, its situation implies significant inequality, and the long-term effects of these conditions would include neurological and psychological illnesses [33]. In 2021, the official poverty rate in the US was 11.6%, with 37.9 million people in poverty [34]. The official poverty rate for males was 10.5% and for females 12.6%, which is significantly higher than for males [34]. Based on data published by Statista Research Department, in 2021, an estimated 14.2% of Texas’s residents lived below the poverty line. The new census estimates showed that Hispanic residents are twice as likely as white residents to live under the poverty level. Though 14.2% of Texans are considered poor, 19.4% of Hispanics live below the poverty level.

Regarding income and socioeconomic status, the statistics for Texas are below the US national average [11]. According to the estimates, the median income for a white family in 2021 was $81,384, while for a Hispanic family it was $54,857. With Hispanic Americans set to become the majority population group within Texas by 2022, the poverty percentage level is also projected to increase, further increasing the poverty gap between Hispanic Americans and other race/ethnic groups. This force on finances results in deeper financial strain for Hispanic communities, which can also affect their capability to access certain forms of medical care for their loved ones or themselves as they age. It also showed less opportunity to develop generational wealth in the long-term. A higher difference, however, was noted in the poverty level. Murimi and colleagues’ study to determine the prevalence of food insecurity and coping strategies in rural West Texas found a significant prevalence of food insecurity in low-income households. Rural west Texas led to high consumption of energy-intense food with little nutrients, resulting in a higher prevalence of obesity, anemia, and other chronic diseases [35]. These diseases are comorbidities that are often present with certain modifiable risk factors of AD/ADRD [36].

Cultural and mental status

Different sociocultural factors affect perceptions and attitudes toward caregiving, such as beliefs, values, cultural norms, faith, and perception of the aging process [37]. Hispanic communities tend to have extended family networks that understand caregiving as a familial obligation. Adults in Hispanic communities generally do not question the need to provide care to an aging parent, grandparent, or family member with a disability. Their main goal is to keep the family close, living at home with family, rather than sending a loved one to a nursing facility for caregiving because of the strong sense of caregiver role responsibility [38, 39]. Being family-oriented can sometimes over-burden the family and lead to caregiver stress. Hispanic families experience higher levels of dementia caregiver burden linked with the cultural values they support, which may serve as protective against dementia caregiver burden or, equally, place them at an elevated risk for the same [40]. Sociocultural values and expectations may improve or worsen the emotional well-being of dementia caregivers [41].

Lack of health knowledge (health literacy)

Knowing the health literacy of elderly patients and their caregivers is necessary because caregivers assist patients in different tasks, manage daily health care, administer medication, and make health service utilization decisions [42]. According to WHO, health literacy is the cognitive and social skills that determine people’s ability to gain, access, understand, and use knowledge in ways that promote and maintain good health [43]. Economists estimate that low health literacy causes adverse consequence and add $106 billion to $238 billion annually to the US health care costs [44]. 13.5% of the US population are Spanish speakers [45]. An estimated 80 million people in the US have restricted health literacy [46]. Texas includes a significant number of residents who have immigrated from Mexico, and frequently travel between the two countries. Information related to the health and health Literacy of Hispanic individuals is sometimes not documented [8]. Among some Hispanic caregivers, AD/ADRD is often considered to be the result of having experienced a difficult life, “God’s Will”, or results from such forces such as “el mal ojo” (the evil eye). There are also instances where AD/ADRD may also carry the stigma of the older person “losing their mind” and therefore suitable medical treatment is overlooked [47]. According to the CDC, in rural West Texas, the rate of heart disease is higher in the Hispanic community [12]. Physical inactivity and unhealthy diets are part of their lifestyle [12]. The lack of knowledge about AD/ADRD is one of the reasons that Hispanic people think that any symptoms are part of normal aging. Many people do not know about the signs and symptoms of AD. Better health knowledge leads to better self-administration and prevention of any adverse effects. Lifestyle factors affect the onset of several diseases, such as strokes, kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes. There are also several environmental risk factors for AD, including diet and cholesterol levels, head injuries, and insufficient exercise. Most of the risk for AD does, however, seem to be established early in life [48]. The study by Christy et al. characterizing health among Spanish preferring Hispanics/Latinos individuals aged between 50 to 75 found 53% of participants having difficulty sometimes or always with written health information while 25% of participants always seek help in completing health forms [45]. Several studies showed association between health literacy, health care utilization, sociodemographic features, and preventive health models including social influence, religious beliefs, and self-efficacy among medically underserved communities [49].

Education

According to Literacy Statistics in the US for 2022 (Data and Facts), in 2022, 79% of US adults are literate in the US, and 21% are illiterate. According to the world population review, and Literacy Statistics in the US for 2022 (Data and Facts), Texas has the fourth lowest literacy rate of 81%, with 19% of adults lacking basic literacy skills. According to Literacy Texas, Texas places 49 out of 50 states in the percentage of adults with a high school education. In addition, Texas ranks 46 out of 50 for adult literacy; 43% of the adults with the lowest literacy rate live in poverty, and only 4% have high literacy skills, according to Literacy Texas. Between 2014 to 2018, the percentage of individuals aged 25 years and older who held a bachelor’s degree or higher education in the US was 31.5%, while Texas fell below the national average at 29.3% [11]. Although they accounted for over 40% of the total population of Texas in 2018, a mere 15.2% of Hispanic or Latino Americans held a bachelor’s degree or higher. Only 38% of Hispanics have a postsecondary education in Texas, compared with 71% of whites and 62% Blacks [50]. As with income and poverty level, a similar pattern is seen regarding education in Texas compared to the US national average.

The association between low socioeconomic status and lower educational attainment is bidirectional, and the combination can produce an additive disadvantage, resulting in a vicious cycle. Further investigation is warranted to better understand how these demographic factors contribute to age-related chronic diseases and cognitive decline within the Hispanic American population of Texas.

Language

Language barriers impact both patients and caregivers. Language is also a way by which healthcare provider accesses patients’ trust about health and illness and can create an opportunity to address their problems. The number of individuals (US) who communicate in languages other than English has substantially increased in the last few years. In the US, the language barrier is the most common challenge, with 51.3% of Hispanics reporting needing a translator when seeking health care [51]. 12% of older individuals in the Hispanic/Latino communities are affected by AD, the highest proportion in the US among the different ethnic groups [52]. The demand for ADRD caregivers is higher than other types of caregiving because of the chronic progressive nature of ADRD [53]. For most Latino caregivers, their mother tongue is Spanish, while public awareness seminars and campaigns on AD are often delivered in only the English language [54]. As a result, monolingual caregivers fail to receive current knowledge or information about AD and ADRD and cannot utilize the services. This language barrier affects the interaction with healthcare providers and therefore, the quality of care [55].

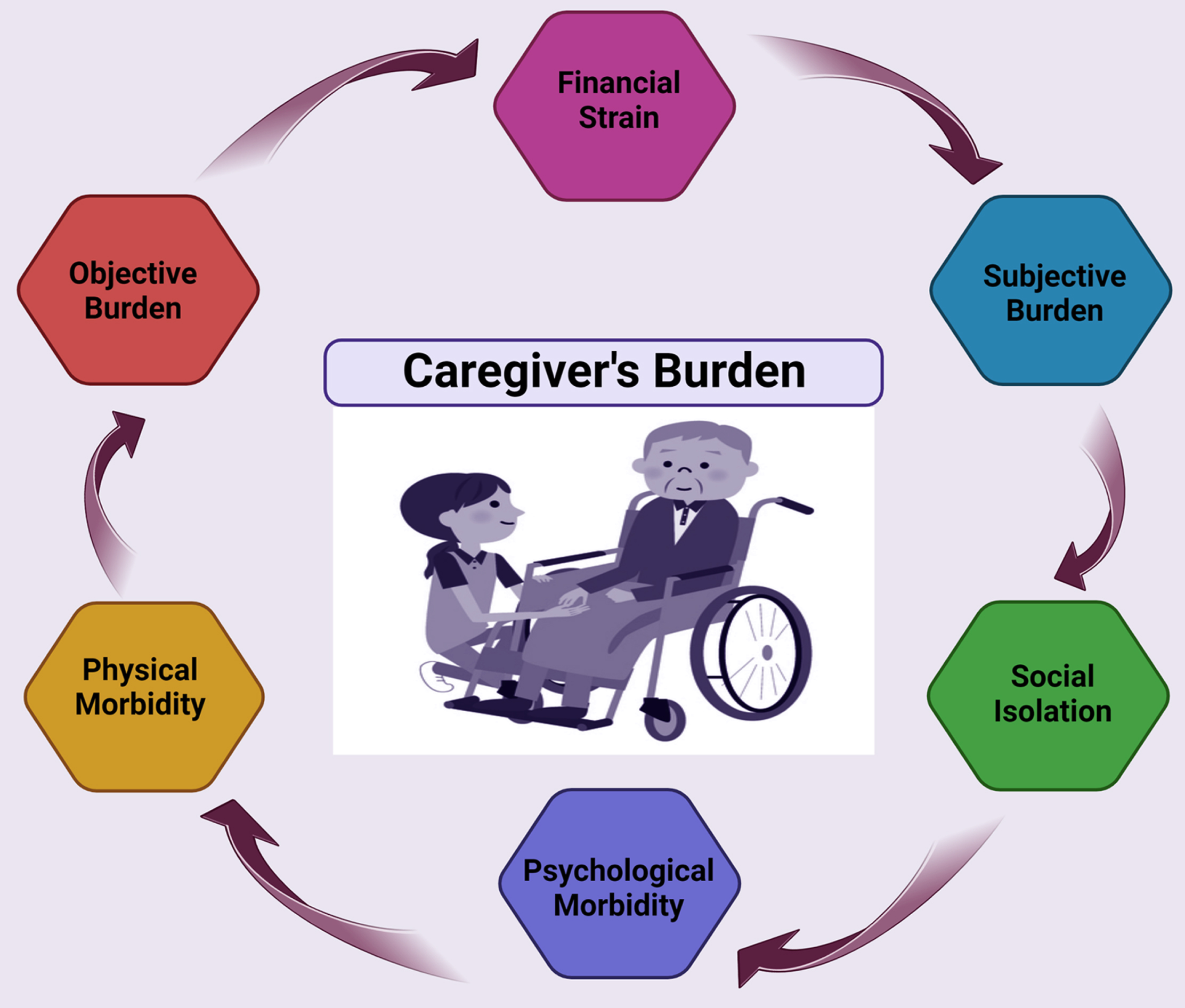

Consequences of care burden on the life of caregivers

The quality of life of individuals with AD/ADRD requiring care depends heavily on family caregivers, frequently referred to as “invisible second patients” [56]. Caregivers motivated by a sense of duty, guilt, and socio-cultural factors experience psychological distress greater than caregivers with more positive motivations [57]. Gender, ethnicity, education, and age can also influence how caregivers view their role [56]. According to many studies, dementia caregivers have a more significant burden than other caregivers [58–60]. AD and ADRD individuals cannot perform daily activities independently due to cognitive decline. AD/ADRD caregivers face depression, anxiety, physical burden, emotional trauma, stress, fatigue, and other long-term adverse effects. Behavioral problems of AD/ADRD individuals include various challenges related to depression (crying, suicidal threats), disruption (verbal and physical aggression), and memory (losing items, hiding things) [61]. These difficulties are also linked with a higher caregiver burden (Fig. 3). The effects on caregivers are different and complicated, and many other aspects may intensify how caregivers react and feel due to their role [56].

Fig. 3

Informal caregiver’s burden. The cognitive decline with the progression of AD/ADRD results in greater levels of responsibility and depression among caregivers.

The study by Mohamed et al. shows that severe psychiatric and behavioral problems, decreased patient quality of life, and lower functional capability were significantly linked with greater levels of burden and depression among caregivers at baseline [62]. They also observed reduced symptoms and improved quality of life after six months of changes, which were related to decreased burden and reported for most of the explained variance [62].

Harrington et al. identified a significant policy gap in supporting female family caregivers who provide most of the care to persons with AD/ADRD risking their health and financial security [63]. They also found nuances of gender, power, ideologies, and compulsory altruism [63].

Formal and informal caregivers

Caregiving can be categorized as either formal or informal. Formal caregivers are professionals that have been paid to aid in meeting the daily needs of individuals. In contrast, informal caregivers are often family, friends, and volunteers who are not paid for their services. People with AD/ADRD face a permanent decrease in their abilities to perform daily tasks. The progression of the disease and its consequence directly affects the families of these patients.

In most cases, families of dementia patients take on the responsibility of providing care [64]. As the health of AD/ADRD patients deteriorates with the progression of the disease, the caregivers are expected to assume increased responsibilities [65]. In the US, the majority of individuals with AD/ADRD live in the community, i.e., around 70% to 81% [66], and almost 75% of these patients with dementia receive caregiving from family and friends [67]. A breakdown of these figures will show a significant proportion of the caregivers are spouses, and children and their spouses, are primarily females. Two-thirds of family caregivers to AD/ADRD patients are women [68, 69], and most are in their midlife [70]. According to Alzheimer’s Association report, currently 11 million adults, the majority of midlife women, are providing 16 billion hours of informal care annually for AD/ADRD and other dementia individuals [71].

Hispanic families use fewer professional caregiver services [72, 73] and mostly rely on relatives compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts. There can be many reasons for Hispanics to be reluctant to rely on formal caregiving services, including fewer financial resources [67], lack of awareness, lack of caregiving facilities, language barrier, and limited culturally acceptable services [73]. Cultural norms, beliefs, and values often define the meaning of illnesses like AD/ADRD and the concept of caregiving in different ethnic populations. In Hispanics, their cultural norms, beliefs, and values strongly affect their caregiving practices. Hispanic culture governs their relationships, and the care of elders is expected to be given by extended family [74]. Familism, a culture that supports close and supportive family relationships, is the core value of Hispanic culture. Although family plays a significant role in caregiving practices; formal caregiving services are typically not discouraged [72].

Hispanic caregivers have a higher caregiving burden and lower overall health status, social functioning, and physical functioning than non-Hispanic caregivers. Since caregivers carry much emotional burden, they are reported to experience higher levels of physical pain and somatic symptoms. Hispanic cultural values influence caregiving’s significance and how caregivers balance perceived obligations to family members [75].

Within family values, the caregiver’s obligation and reciprocity towards aging parents and other family members are to respect and return the love and support shown during adolescence [76]. Hispanic caregivers are more likely than non-Hispanic white caregivers to be supportive and obligatory toward their familial responsibilities, and failure to fulfill such obligations is considered a family shame [38].

Culturally acceptable caregiving

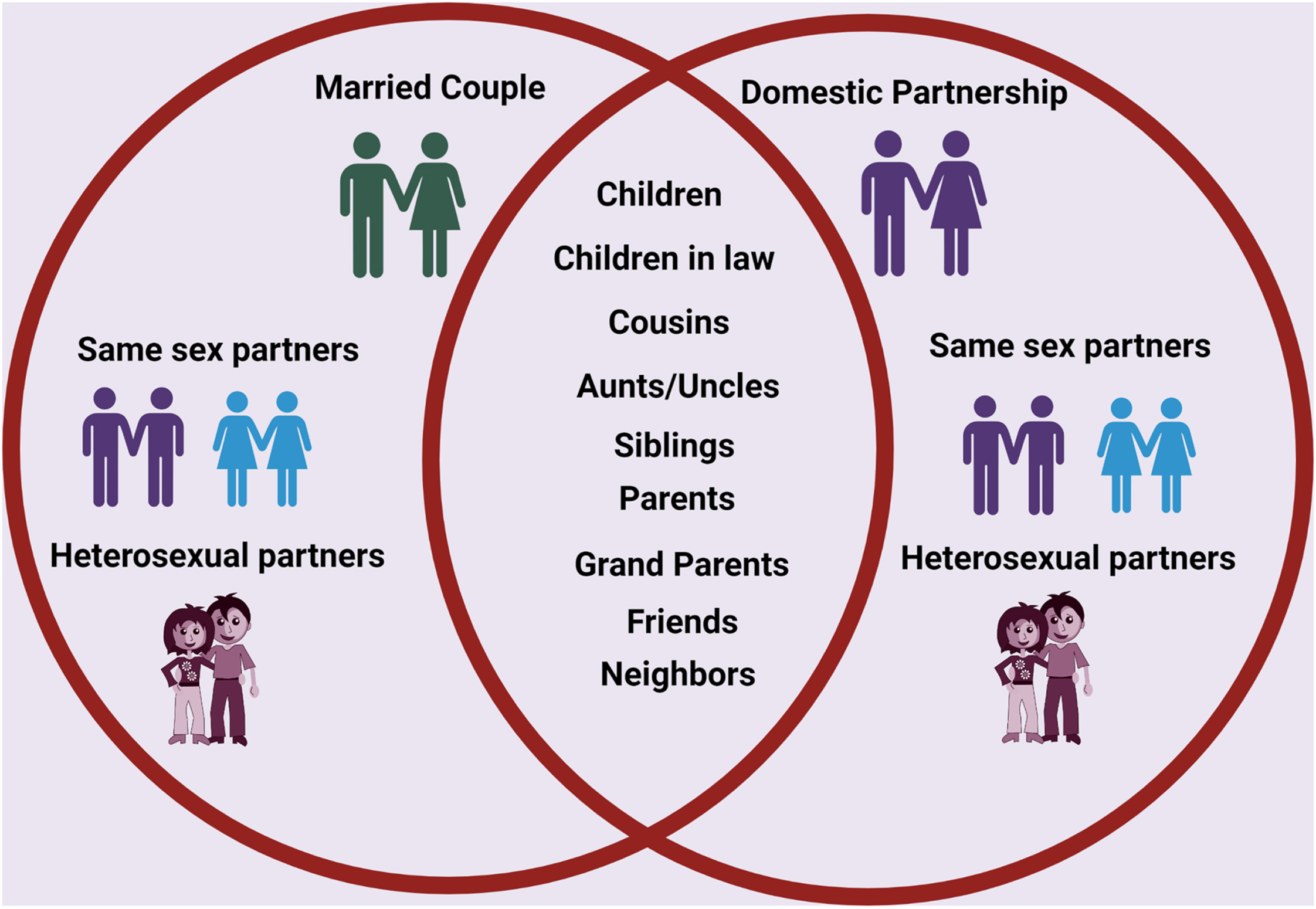

Fig. 4

Familismo, is a cultural value of Hispanics. The family paradigm in Hispanics is extended; grandparents, aunts, cousins, and even those who are not biologically related, like friends and neighbors, are considered family.

Culture is referred as a set of beliefs, values, traditions, and lifestyles shared by a group of individuals and is an imperative component of a person’s life. It is integrated into human behavior and passed down through generations [77]. Culture includes upbringing, language, religiosity, spiritual beliefs, education, gender roles, geographical location, and migration history. Culture also plays an essential role in disease perception, health behavior, and even the etiology of AD/ADRD. These factors may lead to delays in diagnosis, treatment of AD/ADRD, and the caregiving process. [41]. Ethnic, racial, and cultural diversity in the US and worldwide creates an urgency to promote cultural literacy and awareness by increasing multicultural education and training of ADRD clinicians and researchers [75]. Cultural values and norms strongly influence Hispanic caregiving practices. Studies revealed an association between caregiver attitudes and caregiver feelings of distress and depression, and depression was associated with greater adherence to norms that support family [78].

Dynamics of the Hispanic family

Hispanics have a propensity for being very sociable. Family is prioritized as the primary source of identity and one’s defense against life’s challenges. Only family members and close friends may genuinely feel a sense of family. Trust is frequently slow to be placed in those who are not family or close acquaintances. Grandparents, aunts, cousins, and even those not biologically related may be seen as immediate family members; the family paradigm is an extended one (Fig. 4). Familismo is the Spanish phrase for the most significant collective loyalty to extended family [79].

Hispanic poverty rates remain high due to a diverse range of issues, including the difficulties of immigration, low levels of human capital, racial prejudice, and settlement patterns. Recent theories of the decline in marriage, nonmarital childbirth, and female family headship center on a constellation of behaviors and environments linked to poverty, including low skill levels, employment insecurity, and inadequate male salaries [80]. The likelihood of Latinas marrying is higher among those not born in the US than those who were; it is lower among white women and higher among African American women [81]. Low-income early cohabitation or marriage is more common among Hispanic women. Only three in ten low-income Hispanic men have married or cohabitated by age 20, compared to more than half of both foreign-born and US-born low-income Hispanic women. However, more foreign-born low-income Hispanics report being not married than any other group. Low-income Hispanic Americans born in the US have marriage rates more in line with non-Hispanic whites [82].

Compared to non-Hispanic whites and blacks, Hispanics are more likely to live in family households. Additionally, family households of Hispanics are slightly bigger and far more likely to be extended than non-Hispanic whites. Hispanics have significantly more single-parent households and female family heads of households than non-Hispanic whites [80]. In Hispanic households, the actions and decisions of each member of the extended family are based largely on “pleasing the family.” Decisions are rarely taken independently. When a Hispanic family member becomes ill, the health and care-related decisions are strongly influenced by the extended family. Conflicts, non-compliance, discontent with care, and poor continuity of care may result if the healthcare professional fails to consider familismo. Familismo can cause delays in crucial medical decisions, because consulting with extended families requires time. Effective communication includes earning trust and confidence. It is vital to ask the patient’s or parent’s extended family’s viewpoint, and allow them sufficient time to discuss essential medical matters [79].

REACH I AND REACH II STUDIES

Recently, several interventions have been developed to reduce the emotional burden and enhance the physical and mental health of informal caregivers of AD/ADRD individuals. The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) project was planned to test several interventions to support family caregiving for persons with dementia [83]. According to a meta-analysis of the REACH I study, in terms of depression and emotional burden, individualized, structured, and outreach multicomponent interventions are found to be most effective [84]. REACH I was the program’s first step in which 15 well-defined intervention components were tested, evaluated, and compared to fulfill the needs of family caregivers of dementia individuals [85]. Based on results of the REACH I study results, the REACH II study was designed to address the individualized needs of culturally diverse caregivers of persons with Dementia, including African American, White, and Hispanic caregivers. The REACH II interventions showed benefits to African American, White, and Hispanic caregivers and have also been shown to improve the overall life quality of caregivers [86, 87].

DEVELOPING INNOVATIVE METHODS TO ASSESS CAREGIVERS

Although multiple support services are available to many families of individuals with AD/ADRD, caregivers often turn down accessible and affordable services. Previous studies have shown that denial of support services can be attributed to the inadequate matching of available services with the unmet needs of caregivers, lack of awareness, and lack of acknowledgment of caregivers’ unmet needs [88]. There is a dire need to develop innovative methods to assess Hispanic caregivers, to address the lack of educational outreach to Hispanics, low health literacy, financial challenges, lack of trust in formal caregivers, limited cultural and linguistic competency, and inequitable access to the healthcare system in the US.

Innovative methods

Disparities in health care and socioeconomic status for Hispanic/Latino communities show that this community has not equally benefited. Currently, there are numerous measures to examine the psychosocial functioning of family caregivers. However, these measures are limited in their reach to unique populations that are continuing to grow in the US. Some of the significant limitations of these scales include a lack of understanding of cultural factors (e.g., family structure). These limitations affect numerous family caregivers as clinicians cannot identify intervention targets using these measures to help inform treatment interventions. In that regard, the research proposed in this review is innovative because it elucidates the foundational knowledge needed to develop, in amalgamation with experts and stakeholders in the field, a culturally competent measurement tool to identify risk and protective factors for poor psychosocial outcomes in an underserved population.

Social media

Dementia presents caregivers with various issues, including shifting family dynamics, social isolation, and financial constraints. Social media and internet use are widely acknowledged as resources to improve public health and support [89]. Finding family caregivers and gaining access to them, as well as finding caregivers who have the time to participate despite their caring duties, are just a few of the problems involved in conducting research and approaching family caregivers of a progressively ill loved one [90].

Given social media’s advantage of eliminating the physical obstacles that generally prevent access to healthcare resources and support, its usage in public health education has been growing. Health education professionals are challenged to become more proficient in computer-mediated environments that optimize online and offline consumer health experiences as health promotion becomes more firmly ingrained in internet-based programming [91]. Since most US adults (69%) use social media, it is not startling that more people are using it to share and look for health-related information [92].

Murphy and colleagues discussed the challenges in recruiting family caregivers via social media. They discovered that caregivers would agree to take part in the study if they could see a need for assistance, had expectations and motivations for change, could see their value as caregivers, found the recruitment process to be timely, felt supported by the research staff, and could see the advantages of taking part [93].

It will be necessary to understand how to use social media and other recruitment channels to reach the desired subset of family caregivers to help them and enroll this significant demographic in research studies.

Religion and spirituality

Much research has focused on the connection between religion and the help-seeking behavior of older individuals and their caregivers. Numerous research has demonstrated that religion has positive benefits on mortality, pathological diseases, and health [94]. Although the relationship between human well-being and religion or spirituality has been studied for many years, caregivers of dependent persons have received comparatively little attention. Coin and colleagues have demonstrated that with AD dementia, higher levels of religiosity appear to be associated with a slower rate of cognitive and behavioral deterioration and a correspondingly large reduction in the caregiver’s burden [94].

Protective elements are required to reduce the progression of AD/ADRD and maintain quality of life. Common dementia symptoms, including neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), sleep issues, and cognitive decline, show disease progression and stress caregivers. A study on Arabic women showed that praying at midlife is associated with lower risk of mild cognitive impairment in women [95]. Another study investigated relationship between private prayer and NPS, sleep problems, and cognitive performance in dementia-affected older persons. The findings showed a strong correlation between higher personal prayer frequency and decreased NPS, improved cognitive function, and fewer sleep disruptions. All non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic participants prayed at least once a week. The results may be attributable to using cognitive processes in prayer during supplication, asking for assistance, and through communion with the divine, which lessens loneliness [96]. Similarly, faith-related activities, whether group or individual, can significantly aid caregivers of AD/ADRD patients in fostering a sense of belonging in a group and developing their spiritual life, improving feelings of self-worth, and resulting in better physical and mental health overall well-being.

A study examining a sample of Hispanic families in the US caring for an individual with AD employed the stress coping theory to assess the impact of spirituality and religion on depression. The study consisted of 209 Latino caregivers, and their baseline information was taken from the REACH II clinical trial. The results show that, in addition to having a direct influence on depression, church attendance also modifies the association between subjective types of stress and depression. According to the findings, religious involvement may be crucial in preventing depression through indirect and direct channels, which is consistent with religion’s significant role in Latino culture [97].

Incorporating religion/spirituality into the daily routines of family caregivers can alleviate their emotional burden. Activities like meditation, sharing or reading a prayer/holy book, attending, or watching religious services, and even spending time outdoors and connecting with nature would be good coping strategies. It is crucial to remember that while talking about religion/spirituality, they all relate to personal beliefs. Not everyone is religious, even though many individuals do so and find solace in it, but most individuals have some form of spiritual relationship. As intensely personal as beliefs are, each person has another way of infusing them into their daily lives.

Technological interventions

Technological advances and wearable technologies such as sensor-based networks for activity monitoring, fall and wandering detection, smart socks, clevercare smartwatches, and numerous e-health applications have assisted patients and their caregivers to lead independent lifestyles [98]. Wearable technologies help patients monitor and manage their health independently and support caregivers by granting them access to their health data. Although it has been anticipated that technology will help meet caregivers’ demands, there is only limited but growing evidence of technology-mediated interventions targeting caregivers [99].

Modern ambient and remote monitoring technologies (RMTs) make it possible for older persons who desire to age in place to receive individualized, patient-centered, and preventive care. Software and hardware solutions are being developed to manage chronic illness, monitor symptoms, and enhance the quality of life [100]. Both family caregivers and those receiving care can gain from RMTs that sense, record, and communicates different activities of older individuals from the comfort of their homes. RMTs can help caregivers feel more confident in their capacity to take care of a loved one. A new trend of digital health tracking in preventative care is becoming recognized. Products of a new generation of sensor technologies that monitor and transmit data in physical and remote ways continue to develop to support family caregivers and patients. These include smart tattoos that detect vital signs, ingestible digital pills that record and send information when a drug is taken, orthopedic clothing with heat sensors, and many other product solutions for the healthcare industry [101]. According to studies, around three-quarters (74%) of Hispanic caregivers are female and middle-aged. People in their midlife are considered familiar with modern technology, such as computers and smartphones. Therefore policymakers and experts believe that technology is more accessible to deploy for this generation than for older individuals. [102].

Like many other technological advances, the global positioning system (GPS) is a technology that can be used to support AD/ADRD patients and their caregivers. The cognitive impairment in AD/ADRD patients may lead them to get lost and wander when alone. This technology allows caregivers to monitor the geographical location of their loved ones while allowing for individual autonomy [103]. However, there are few, contentious and anecdotal research on the usability and level of acceptance of GPS systems among people with dementia and their caretakers.

Lack of knowledge regarding self and family care is a common challenge for family caregivers of those with AD/ADRD. Due to the unavailability of linguistically and culturally relevant information, this is particularly crucial for those who belong to ethnic minority groups. A website for Spanish-speaking caregivers was created in response to these demands. The bilingual website cuidatecuidador.com offers information about dementia and caregiver-related topics. The website’s content was developed and evaluated by resident caregivers from three countries. According to findings, a stronger sense of mastery and a decrease in depression symptoms may be associated with knowledge exposure [104].

There has been a wide range of intervention trials aimed at reducing the burden of caregiving and providing support to the family caregiver due to the increased reliance on family caregivers to help manage the growing older population. These interventions included skill development, counseling, case management, and social support. Additionally, they are given in various settings and forms, including individual and group sessions at home or in clinical settings. Unfortunately, many family members in the caregiving position do not benefit from these programs because they are unaware of their existence, or have obstacles to accessing them. Therefore, information and communication technologies are required [105].

Psychoeducational interventions

Most research on Latino families that include a member with mental illness has focused on how the family interacts with the patient and how those interactions may affect the patient’s well-being [106–109]. According to data, Latino family caregivers are more likely to reside with the ill individual, be tolerant, have higher hopes for recovery [102, 103], and make less critical remarks about the ill than European-American households [106–108]. There are four different caregiver interventions with psychological components: mindfulness-based interventions, psychoeducation, counseling, and psychotherapy [110]. Previous studies have revealed that family caregivers in palliative home care need to communicate with medical practitioners more effectively and that their requirements for information and psychological support are frequently unfulfilled [111].

As the global burden of AD/ADRD is increasing from 57.4 million cases in 2019 to 152.8 million cases in 2050 [112], additional programs have been created to assist caregivers in managing the care recipients and their difficulties. Few interventions directly focus on caring for caregivers; instead, they improve the caregiver’s ability to address behavioral issues and other deteriorations in functioning. It is believed that due to the effectiveness in fostering emotional well-being, strategies derived from psychotherapy are strategically significant in the support offered to caregivers [110].

A study was conducted to evaluate the possibilities of providing a psychoeducational intervention to Hispanic/Latino family caregivers of dementia patients in a group setting. Seventy primary caregivers who volunteered for the study made up the final sample; 27 were on a waiting list for three months, and 43 were enrolled in the intervention program. Comparisons between those who took part in the 8-week class, which was specifically created to be culturally sensitive and teach several specific cognitive and behavioral skills for managing the frustrations linked with caregiving, and those who remained on the waiting list for that same period were made on a pre-post basis. As compared to control group, those in the class reported drastically fewer depressive symptoms and showed a tendency toward better control over their anger and impatience [113].

Hispanic educators

Rapid transformations in the healthcare sector have shifted the scope of healthcare settings from acute care facilities to include other locations. Various ethnic and racial groupings are now represented in the healthcare workforce, which previously had a less diverse ethnic origin. Additionally, a wide variety of ethnic origins are represented among the patient population. According to estimates, Hispanics will make up most of the population by 2080, followed by African Americans and Asians [114]. However, language significantly impacts an individual’s ability to obtain and use healthcare, as well as how well they comprehend their health insurance and interact with their providers.

The language barrier is a significant reason for Latino caregivers’ underutilization of the social services available to them. Language limitations and the information offered by organizations that provide services for AD/ADRD remains problematic. Spanish is the predominant language of many Latino caregivers [78], and frequently Spanish-language public awareness information is not readily available. The development of innovative methods to support Hispanic family caregivers can benefit them only by understanding the obstacles preventing the Latino community from utilizing services. Spanish-speaking social workers’/Educators’ outreach to the Latino community would increase access and utilization of services. Incorporating the services of Hispanic healthcare professionals called promotor(a)s into mainstream healthcare may provide an opportunity to address this barrier. Promotoras are a group of health workers in rural Texas who provide basic health information in the community, educate families about health issues, and provide guidance in accessing community resources associated with healthcare [115]. Being from within the community themselves, they build strong relationships, which allow gaining information about the healthcare status of patients and promoting positive healthcare outcomes. They are better able to assess the cultural and ethnocentric beliefs of Hispanics surrounding AD/ADRD, which play a key role in both patient and caregiver behaviors and subsequently their health outcomes.

Validating innovative measures

As detailed above, Hispanic family caregivers of patients with AD/ADRD have unique challenges, and often receive the least amount of formal healthcare to manage the progress of the disease. Therefore, it is critically important to ensure that the plight of the family caregivers of AD/ADRD in the Hispanic community is considered. Necessary accommodations to improve their quality of life and provide resources necessary to support their AD/ADRD patients, while also taking care of cultural differences in knowledge and beliefs about AD/ADRD [50, 116].

Development of novel scales and measures are of critical importance in the ever-changing field of health and behavioral sciences. Novel diseases, populations and health-related outcomes pose the urgency for innovative measures. The need for culturally competent measures specific to informal caregivers of AD/ADRD is a matter of urgency. Development of novel and innovative measures is not enough, as they cannot be implemented until their psychometric properties are evaluated. This can be done by examining the validity and reliability of the measures. Validity refers to whether a measurement tool is measuring what it is designed to measure. There are several different types of validity which include: i) Content validity (or face validity) refers to expert opinion concerning whether the scale items represent the proposed domains; ii) Convergent validity can be demonstrated by correlating the measure with other related measures and; iii) Construct validity relates to how well the items in the measure are conceptually relevant [117]. Reliability on the other hand is essential and refers to the repeatability, stability, or internal consistency of a questionnaire. One of the most common ways to demonstrate this uses the test statistic known as Cronbach’s α statistic. This statistic uses inter-item correlations to determine whether individual items of the measure are yielding same results when repeated administered. Cronbach’s α should exceed 0.70 for a newly developed questionnaire or 0.80 for a more standard questionnaire. Each item on a questionnaire may have an individual Cronbach’s α to demonstrate its reliability. Test–retest reliability is another test, which can assess stability of a measure longitudinally and is an important statistical tool to be used in the development phase of a new measure [117, 118]. Validity and reliability are two main psychometric properties of any measure and it’s imperative to ensure that any novel, innovative measure satisfies these properties to be considered legitimate and be used in standard clinical practice.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The Hispanic population is the largest growing minority in the US, particularly in Texas, and the increasing prevalence of AD/ADRD is similar for the Hispanics. Family-centered caregiving is very common in the Hispanic population with over a third of the Hispanics in US caring for the elderly population. The discussion in this paper advances the knowledge by identifying the issues faced by Hispanic family caregivers of AD/ADRD patients that would contribute to developing innovating methods to help and support the caregiving community. Although the burden of caregiving has a negative impact on Hispanic households, the effect of culture on the perception of this burden has not been adequately studied. Currently, there is a lack of understanding of burden and psychosocial factors experienced by Hispanic family caregivers who are living with a person with AD/ADRD. Assessment and unique methodology are urgently needed to assist Hispanic family caregivers. The initial steps require a detailed review of the literature for cultural factors impacting caregiving and to assess status of measurement tools, and the development of methods to support Hispanic family caregivers in the US. Improved awareness, educational resources, and access to available facilities will allow Hispanic caregivers to better identify risks to their overall wellbeing, and implement preventative self-management strategies to avoid or lessen the negative health effects of caregiving.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors sincerely thank all healthy aging study personnel and also Reddy Lab members for critical reading of our manuscript.

FUNDING

The research and relevant findings presented in this article was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AG042178, AG047812, NS105473, AG060767, AG069333, AG066347 and AG079264.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

REFERENCES

[1] | Rawat P , Sehar U , Bisht J , Selman A , Culberson J , Reddy PH ((2022) ) Phosphorylated tau in Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies. Int J Mol Sci 23: , 12841. |

[2] | Sehar U , Rawat P , Reddy AP , Kopel J , Reddy PH ((2022) ) Amyloid beta in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci 23: , 12924. |

[3] | Gaugler J , James B , Johnson T , Reimer J , Solis M , Weuve J , Buckley RF , Hohman TJ ((2022) ) 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 18: , 700–789. |

[4] | Jack CR Jr , Knopman DS , Jagust WJ , Petersen RC , Weiner MW , Aisen PS , Shaw LM , Vemuri P , Wiste HJ , Weigand SD ((2013) ) Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol 12: , 207–216. |

[5] | Maloney B , Lahiri DK ((2016) ) Epigenetics of dementia: Understanding the disease as a transformation rather than a state. Lancet Neurol 15: , 760–774. |

[6] | Lahiri DK ((2012) ) The “LEARn” (latent early-life associated regulation) model: An epigenetic pathway linking metabolic and cognitive disorders. J Alzheimers Dis 30: Suppl 2, S15–S30. |

[7] | Lahiri DK ((2009) ) The LEARn model: An epigenetic explanation for idiopathic neurobiological diseases. Mol Psychiatry 14: , 992–1003. |

[8] | Anders RL , Olson T , Robinson K , Wiebe J , DiGregorio R , Guillermina M , Albrechtsen J , Bean NH , Ortiz M ((2010) ) A health survey of a colonia located on the west Texas, US/Mexico border. J Immigr Minor Health 12: , 361–369. |

[9] | Dewees S , Velázquez JA ((2000) ) Community development in rural Texas: A case study of Balmorhea public schools. Community Dev 31: , 216–232. |

[10] | Alzheimer’s Association ((2010) ) 2010 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 6: , 158–194. |

[11] | Sheladia S , Reddy PH ((2021) ) Age-related chronic diseases and Alzheimer’s disease in Texas: A Hispanic focused study. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 5: , 121–133. |

[12] | Reddy PH ((2019) ) Lifestyle and risk factors of dementia in rural West Texas. J Alzheimers Dis 72: , S1–S10. |

[13] | Lwi SJ , Ford BQ , Casey JJ , Miller BL , Levenson RW ((2017) ) Poor caregiver mental health predicts mortality of patients with neurodegenerative disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: , 7319–7324. |

[14] | Ortiz F , Fitten LJ ((2000) ) Barriers to healthcare access for cognitively impaired older Hispanics. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 14: , 141–150. |

[15] | Stone RI ((2015) ) Factors affecting the future of family caregiving in the United States. In Family Caregiving in the New Normal, Gaugler J, Kane R, eds. Elsevier, pp. 57–77. |

[16] | Feng Z , Fennell ML , Tyler DA , Clark M , Mor V ((2011) ) Growth of racial and ethnic minorities in US nursing homes driven by demographics and possible disparities in options. Health Aff (Millwood) 30: , 1358–1365. |

[17] | Connors MH , Seeher K , Teixeira-Pinto A , Woodward M , Ames D , Brodaty H ((2020) ) Dementia and caregiver burden: A three-year longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 35: , 250–258. |

[18] | Texas population 2022 (Demographic, Maps, Graphs), Texas population 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/states/texas-population |

[19] | World Population Review, United States by Density 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/state-densities. |

[20] | Valencia L ((2020) ) Texas Demographic Trends and Projections and the 2020 Census. Texas Demographic Center. https://demographics.texas.gov/Resources/Presentations/OSD/2021/2021_01_29_MexicanAmericanLegislativeLeadershipFellowship.pdf. |

[21] | Buckwalter KC , Davis LL ((2011) ) Elder caregiving in rural communities. In Rural Caregiving in the United States, Talley RC, Chwalisz K, Buckwalter KC, eds. Springer, pp. 33–46. |

[22] | Ortega AN , Rodriguez HP , Vargas Bustamante A ((2015) ) Policy dilemmas in Latino health care and implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Annu Rev Public Health 36: , 525–544. |

[23] | Almberg B , Jansson W , Grafström M , Winblad B ((1998) ) Differences between and within genders in caregiving strain: A comparison between caregivers of demented and non-caregivers of non-demented elderly people. J Adv Nurs 28: , 849–858 |

[24] | Etters L , Goodall D , Harrison B ((2008) ) Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 20: , 423–428. |

[25] | Yee JL , Schulz R ((2000) ) Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: A review and analysis. Gerontologist 40: , 147–164. |

[26] | Kuuppelomäki M , Sasaki A , Yamada K , Asakawa N , Shimanouchi S ((2004) ) Family carers for older relatives: Sources of satisfaction and related factors in Finland. Int J Nurs Stud 41: , 497–505. |

[27] | Rose-Rego SK , Strauss ME , Smyth KA ((1998) ) Differences in the perceived well-being of wives and husbands caring for persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontologist 38: , 224–230. |

[28] | del-Pino-Casado R , Frías-Osuna A , Palomino-Moral PA , Ramón Martínez-Riera J ((2012) ) Gender differences regarding informal caregivers of older people. J Nurs Scholarsh 44: , 349–357. |

[29] | Andrén S , Elmståhl S ((2005) ) Family caregivers’ subjective experiences of satisfaction in dementia care: Aspects of burden, subjective health and sense of coherence. Scand J Caring Sci 19: , 157–168. |

[30] | Galanti GA ((2003) ) The Hispanic family and male-female relationships: An overview. J Transcult Nurs 14: , 180–185. |

[31] | Evercare® Study of Hispanic Family caregiving in the USA (2008). Retreived from: https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Hispanic_Caregiver_Study_web_ENG_FINAL_11_04_08.pdf. |

[32] | Lahiri DK , Maloney B , Song W , Sokol DK ((2022) ) Crossing the “birth border” for epigenetic effects. Biol Psychiatry 92: , e21–e23. |

[33] | Maloney B , Bayon BL , Zawia NH , Lahiri DK ((2018) ) Latent consequences of early-life lead (Pb) exposure and the future: Addressing the Pb crisis. Neurotoxicology 68: , 126–132. |

[34] | Creamer J , Shrider E , Burns K , Chen F ((2022) ) Poverty in the United States: 2021. United States Census Bureau, Current Population Reports P60-277. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-277.html |

[35] | Murimi MW , Kanyi MG , Mupfudze T , Mbogori TN , Amin MR ((2016) ) Prevalence of food insecurity in low-income neighborhoods in West Texas. J Nutr Educ Behav 48: , 625–630. e1. |

[36] | Morton H , Kshirsagar S , Orlov E , Bunquin LE , Sawant N , Boleng L , George M , Basu T , Ramasubramanian B , Pradeepkiran JA ((2021) ) Defective mitophagy and synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease: Focus on aging, mitochondria and synapse. Free Radic Biol Med 172: , 652–667. |

[37] | Powers SM , Whitlatch CJ ((2016) ) Measuring cultural justifications for caregiving in African American and White caregivers. Dementia 15: , 629–645. |

[38] | Gallagher-Thompson D , Haley W , Guy D , Rupert M , Argüelles T , Zeiss LM , Long C , Tennstedt S , Ory M ((2003) ) Tailoring psychological interventions for ethnically diverse dementia caregivers. Clin Psychol 10: , 423. |

[39] | Losada A , Robinson Shurgot G , Knight BG , Márquez M , Montorio I , Izal M , Ruiz MA ((2006) ) Cross-cultural study comparing the association of familism with burden and depressive symptoms in two samples of Hispanic dementia caregivers. Aging Ment Health 10: , 69–76. |

[40] | Rosa D , Fuentes MA ((2020) ) Grief, loss, and depression in Latino caregivers and families affected by dementia. In Caring for Latinxs with Dementia in a Globalized World Adames HY, Tazeau YN, eds. Springer ,pp. 247–264. |

[41] | Vila-Castelar C , Fox-Fuller JT , Guzmán-v´lez E , Schoemaker D , Quiroz YT ((2022) ) A cultural approach to dementia— insights from US Latino and other minoritized groups. Nat Rev Neurol 18: , 307–314. |

[42] | Garcia CH , Espinoza SE , Lichtenstein M , Hazuda HP ((2013) ) Health literacy associations between Hispanic elderly patients and their caregivers. J Health Commun 18: , 256–272. |

[43] | Gellert P , Tille F ((2015) ) What do we know so far? The role of health knowledge within theories of health literacy. Eur Health Psychol 17: , 266–274. |

[44] | Vernon JA , Trujillo A , Rosenbaum SJ , DeBuono B ((2007) ) Low health literacy: Implications for national health policy. Department of Health Policy, School of Public Health and Health Services, The George Washington University, Washington, DC. |

[45] | Christy SM , Cousin LA , Sutton SK , Chavarria EA , Abdulla R , Gutierrez L , Sanchez J , Lopez D , Gwede CK , Meade CD ((2021) ) Characterizing health literacy among Spanish Language-preferring Latinos ages 50–75. Nurs Res 70: , 344. |

[46] | Berkman ND , Sheridan SL , Donahue KE , Halpern DJ , Crotty K ((2011) ) Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 155: , 97–107. |

[47] | Gray HL , Jimenez DE , Cucciare MA , Tong H-Q , Gallagher-Thompson D ((2009) ) Ethnic differences in beliefs regarding Alzheimer disease among dementia family caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 17: , 925–933. |

[48] | Lahiri DK , Maloney B ((2010) ) The “LEARn” (Latent Early-life Associated Regulation) model integrates environmental risk factors and the developmental basis of Alzheimer’s disease, and proposes remedial steps. Exp Gerontol 45: , 291–296. |

[49] | Christy SM , Gwede CK , Sutton SK , Chavarria E , Davis SN , Abdulla R , Ravindra C , Schultz I , Roetzheim R , Meade CD ((2017) ) Health literacy among medically underserved: The role of demographic factors, social influence, and religious beliefs. J Health Commun 22: , 923–931. |

[50] | Carnevale AP , Fasules ML ((2017) ) Latino education and economic progress: Running faster but still behind. Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce, Washington, DC. |

[51] | Duran M ((2012) ) Rural Hispanic health care utilization. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care 12: , 49–54. |

[52] | ((2021) ) 2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 17: , 327–406. |

[53] | Falzarano F , Moxley J , Pillemer K , Czaja SJ ((2022) ) Family matters: Cross-cultural differences in familism and caregiving outcomes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 77: , 1269–1279. |

[54] | Gallagher-Thompson D , Talamantes M , Ramirez R , Valverde I ((2014) ) Service delivery issues and recommendations for working with Mexican American family caregivers. In Ethnicity and the Dementias, Yeo G, Gerdner LA, Gallagher-Thompson D, eds. Taylor & Francis, pp. 137–152. |

[55] | Cersosimo E , Musi N ((2011) ) Improving treatment in Hispanic/Latino patients. Am J Med 124: , S16–S21. |

[56] | Brodaty H , Donkin M ((2022) ) Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 11: , 217–228. |

[57] | Pyke KD , Bengtson VL ((1996) ) Caring more or less: Individualistic and collectivist systems of family eldercare. J Marriage Fam 58: , 379. |

[58] | Clare L , Wu YT , Quinn C , Jones IR , Victor CR , Nelis SM , Martyr A , Litherland R , Pickett JA , Hindle JV , Jones RW , Knapp M , Kopelman MD , Morris RG , Rusted JM , Thom JM , Lamont RA , Henderson C , Rippon I , Hillman A , Matthews FE ; IDEAL Study Team ((2019) ) A comprehensive model of factors associated with capability to “live well” for family caregivers of people living with mild-to-moderate dementia: Findings from the IDEAL Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 33: , 29–35. |

[59] | González-Salvador MT , Arango C , Lyketsos CG , Barba AC ((1999) ) The stress and psychological morbidity of the Alzheimer patient caregiver. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 14: , 701–710. |

[60] | Ory MG , Hoffman III RR , Yee JL , Tennstedt S , Schulz R ((1999) ) Prevalence and impact of caregiving: A detailed comoparison between dementia and nondementia caregivers. Gerontologist 39: , 177–186 . |

[61] | Teri L , Truax P , Logsdon R , Uomoto J , Zarit S , Vitaliano PP ((1992) ) Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychol Aging 7: , 622–631. |

[62] | Mohamed S , Rosenheck R , Lyketsos CG , Schneider LS ((2010) ) Caregiver burden in Alzheimer disease: Cross-sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 18: , 917–927. |

[63] | Harrington C , Dean-Witt C, Z , Cacchione P ((2022) ) Female caregivers’ contextual complexities and familial power structures within Alzheimer’s care. J Women Aging, 10.1080/08952841.2022.2130655. |

[64] | Wilks SE , Croom B ((2008) ) Perceived stress and resilience in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers: Testing moderation and mediation models of social support. Aging Ment Health 12: , 357–365. |

[65] | Chiao CY , Wu HS , Hsiao CY ((2015) ) Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. Int Nurs Rev 62: , 340–350. |

[66] | ((2020) ) 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 16: , 391–460. |

[67] | Schulz R , Martire LM ((2004) ) Family caregiving of persons with dementia: Prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 12: , 240–249. |

[68] | Alzheimer’s Association ((2016) ) 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 12: , 459–509. |

[69] | Hurd MD , Martorell P , Delavande A , Mullen KJ , Langa KM ((2013) ) Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 368: , 1326–1334. |

[70] | Berg JA ((2011) ) The stress of caregiving in midlife women. Female Patient 36: , 33–36. |

[71] | ((2022) ) 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 18: , 700–789. |

[72] | Crist JD , Speaks P ((2011) ) Keeping it in the family: When Mexican American older adults choose not to use home healthcare services. Home Healthc Nurse 29: , 282–290. |

[73] | Dilworth-Anderson P , Williams IC , Gibson BE ((2002) ) Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: A 20-year review (1980–2000). Gerontologist 42: , 237–272. |

[74] | Dilworth-Anderson P , Gibson BE ((2002) ) The cultural influence of values, norms, meanings, and perceptions in understanding dementia in ethnic minorities. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 16: , S56–S63. |

[75] | Pharr JR , Dodge Francis C , Terry C , Clark MC ((2014) ) Culture, caregiving, and health: Exploring the influence of culture on family caregiver experiences. ISRN Public Health 2014: , 1–8. |

[76] | Blieszner R , Hamon RR ((1992) ) Filial responsibility: Attitudes, motivators, and behaviors. In Gender, Families, and Elder Care, DwyerJW, CowardR, eds. Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 105–119. |

[77] | Henrich J , McElreath R ((2003) ) The evolution of cultural evolution. Evol Anthropol 12: , 123–135. |

[78] | Cox C , Monk A ((1993) ) Hispanic culture and family care of Alzheimer’s patients. Health Soc Work 18: , 92–100. |

[79] | Carteret M ((2011) ) Cultural values of Latino patients and families. Retrieved from: https://www.dimensionsofculture.com/2011/03/cultural-values-of-latino-patients-and-families/ |

[80] | Landale NS , Oropesa RS , Bradatan C ((2006) ) Hispanic families in the United States: Family structure and process in an era of family change. In Hispanics and the Future of America, Tienda M , Mitchell F , eds. National Research Council (US) Panel on Hispanics in the United States, National Academies Press, Washington, DC, pp. 138–178. |

[81] | Lloyd KM ((2006) ) Latinas’ transition to first marriage: An examination of four theoretical perspectives. J Marriage Fam 68: , 993–1014. |

[82] | Wildsmith E , Scott M , Guzman L , Cook E ((2014) ) Family structure and family formation among low-income Hispanics in the US. Child Trends Publication #2014–48. |

[83] | Wisniewski SR , Belle SH , Coon DW , Marcus SM , Ory MG , Burgio LD , Burns R , Schulz R ((2003) ) The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): Project design and baseline characteristics. Psychol Aging 18: , 375–384. |

[84] | Gitlin LN , Belle SH , Burgio LD , Czaja SJ , Mahoney D , Gallagher-Thompson D , Burns R , Hauck WW , Zhang S , Schulz R ((2003) ) Effect of multicomponent interventions on caregiver burden and depression: The REACH multisite initiative at 6-month follow-up. Psychol Aging 18: , 361–374. |

[85] | Belle SH , Burgio L , Burns R , Coon D , Czaja SJ , Gallagher-Thompson D , Gitlin LN , Klinger J , Koepke KM , Lee CC ((2006) ) Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 145: , 727–738. |

[86] | Meyer OL , Liu X , Tancredi D , Ramirez AS , Schulz R , Hinton L ((2018) ) Acculturation level and caregiver outcomes from a randomized intervention trial to enhance caregivers’ health: Evidence from REACH II. Aging Ment Health 22: , 730–737. |

[87] | Elliott AF , Burgio LD , DeCoster J ((2010) ) Enhancing caregiver health: Findings from the resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s caregiver health II intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: , 30–37. |

[88] | Zwingmann I , Dreier-Wolfgramm A , Esser A , Wucherer D , Thyrian JR , Eichler T , Kaczynski A , Monsees J , Keller A , Hertel J ((2020) ) Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res 20: , 121. |

[89] | Gkotsis G , Mueller C , Dobson RJ , Hubbard TJ , Dutta R ((2020) ) Mining social media data to study the consequences of dementia diagnosis on caregivers and relatives. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 49: , 295–302. |

[90] | Morrison K , Winter L , Gitlin LN ((2016) ) Recruiting community-based dementia patients and caregivers in a nonpharmacologic randomized trial: What works and how much does it cost? J Appl Gerontol 35: , 788–800. |

[91] | Stellefson M , Paige SR , Chaney BH , Chaney JD ((2020) ) Evolving role of social media in health promotion: Updated responsibilities for health education specialists. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: , 1153. |

[92] | Pew Research Center ((2017) ) Pew Research Center. Social media fact sheet–Washington, DC. |

[93] | Murphy MR , Escamilla MI , Blackwell PH , Lucke KT , Miner-Williams D , Shaw V , Lewis SL ((2007) ) Assessment of caregivers’ willingness to participate in an intervention research study. Res Nurs Health 30: , 347–355. |

[94] | Coin A , Perissinotto E , Najjar M , Girardi A , Inelmen E , Enzi G , Manzato E , Sergi G ((2010) ) Does religiosity protect against cognitive and behavioral decline in Alzheimer’s dementia? Curr Alzheimer Res 7: , 445–452. |

[95] | Inzelberg R , Afgin AE , Massarwa M , Schechtman E , Israeli-Korn SD , Strugatsky R , Abuful A , Kravitz E , Farrer LA , Friedland RP ((2013) ) Prayer at midlife is associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline in Arabic women. Curr Alzheimer Res 10: , 340–346. |

[96] | Britt KC , Richards KC , Acton G , Hamilton J , Radhakrishnan K ((2022) ) Older adults with dementia: Association of prayer with neuropsychiatric symptoms, cognitive function, and sleep disturbances. Religions 13: , 973. |

[97] | Sun F , Hodge DR ((2014) ) Latino Alzheimer’s disease caregivers and depression: Using the stress coping model to examine the effects of spirituality and religion. J Appl Gerontol 33: , 291–315. |

[98] | Dai B , Larnyo E , Tetteh EA , Aboagye AK , Musah A-AI ((2020) ) Factors affecting caregivers’ acceptance of the use of wearable devices by patients with dementia: An extension of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 35: , 1533317519883493. |

[99] | Demiris G , Washington K , Ulrich CM , Popescu M , Oliver DP ((2019) ) Innovative tools to support family caregivers of persons with cancer: The role of information technology. Semin Oncol Nurs 35: , 384–388. |

[100] | Carroll N ((2016) ) Key success factors for smart and connected health software solutions. Computer 49: , 22–28. |

[101] | Snyder MM , Dringus LP , Schladen MM , Chenail R , Oviawe E ((2020) ) Remote monitoring technologies in dementia care: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of family caregivers’ experiences. Qual Rep 25: , 1233–1252. |

[102] | Popok PJ , Reichman M , LeFeber L , Grunberg VA , Bannon SM , Vranceanu AM ((2022) ) One diagnosis, two perspectives: Lived experiences of persons with young-onset dementia and their care-partners. Gerontologist 62: , 1311–1323. |

[103] | Pot AM , Willemse BM , Horjus S ((2012) ) A pilot study on the use of tracking technology: Feasibility, acceptability, and benefits for people in early stages of dementia and their informal caregivers. Aging Ment Health 16: , 127–134. |

[104] | Pagán-Ortiz ME , Cortées DE , Rudloff N , Weitzman P , Levkoff S ((2014) ) Use of an online community to provide support to caregivers of people with dementia. J Gerontol Soc Work 57: , 694–709. |

[105] | Czaja SJ , Perdomo D , Lee CC ((2016) ) The role of technology in supporting family caregivers. In International Conference on Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population Springer, Cham, 178–185. |

[106] | Karno M , Jenkins JH , De la Selva A , Santana F , Telles C , Lopez S , Mintz J ((1987) ) Expressed emotion and schizophrenic outcome among Mexican-American families. J Nerv Ment Dis 175: , 143–151. |

[107] | Kopelowicz A , Zarate R , Gonzalez V , Lopez SR , Ortega P , Obregon N , Mintz J ((2002) ) Evaluation of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: A comparison of Caucasians and Mexican-Americans. Schizophr Res 55: , 179–186 . |

[108] | Jenkins JH , Karno M , Selva A , Santana F ((1986) ) Expressed emotion in cross-cultural context: Familial responses to schizophrenic illness among Mexican Americans. In Treatment of Schizophrenia, Goldstein MJ, Hand I, Hahlweg K, eds. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 35–49. |

[109] | Kopelowicz A , Zarate R , Smith VG , Mintz J , Liberman RP ((2003) ) Disease management in Latinos with schizophrenia: A family-assisted, skills training approach. Schizophr Bull 29: , 211–228. |

[110] | Cheng ST , Au A , Losada A , Thompson LW , Gallagher-Thompson D ((2019) ) Psychological interventions for dementia caregivers: What we have achieved, what we have learned. Curr Psychiatry Rep 21: , 59. |

[111] | Ventura AD , Burney S , Brooker J , Fletcher J , Ricciardelli L ((2014) ) Home-based palliative care: A systematic literature review of the self-reported unmet needs of patients and carers. Palliat Med 28: , 391–402. |

[112] | Nichols E , Steinmetz JD , Vollset SE , Fukutaki K , Chalek J , Abd-Allah F , Abdoli A , Abualhasan A , Abu-Gharbieh E , Akram TT ((2022) ) Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7: , e105–e125. |

[113] | Gallagher-Thompson D , Arean P , Rivera P , Thompson LW ((2001) ) A psychoeducational intervention to reduce distress in Hispanic family caregivers: Results of a pilot study. Clin Gerontol 23: , 17–32. |

[114] | Tate DM ((2003) ) Cultural awareness: Bridging the gap between caregivers and Hispanic patients. J Contin Educ Nurs 34: , 213–217. |

[115] | Hausmann LR , Jeong K , Bost JE , Ibrahim SA ((2008) ) Perceived discrimination in health care and health status in a racially diverse sample. Med Care 46: , 905–914. |

[116] | Connell CM , Roberts JS , McLaughlin SJ , Akinleye D ((2009) ) Racial differences in knowledge and beliefs about Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23: , 110–116. |

[117] | Boateng GO , Neilands TB , Frongillo EA , Melgar-Quiñonez HR , Young SL ((2018) ) Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Front Public Health 6: , 149. |

[118] | Roberts P , Priest H ((2006) ) Reliability and validity in research. Nurs Stand 20: , 41–46. |