Developmentally Appropriate Prevention of Behavioral and Emotional Problems, Social-Emotional Learning, and Developmentally Appropriate Practice for Early Childhood Education and Care – The Papilio Approach from 0 to 9

Abstract

This thematic section editorial gives an overview of the three related articles introducing the programs Papilio-3to6, Papilio-U3, and Papilio-6to9. The essential, connecting elements are presented (developmentally appropriate prevention, social-emotional learning [SEL], and developmentally appropriate practice) and the relation between the three programs is explained in the context of an overarching educational approach from 0 to 9 to early childhood education and care (ECEC).

Dedicated to Heidrun Mayer (†) – her vision became reality!

The development and differentiation of social-emotional competencies is one of the important developmental tasks in early childhood. Simply expressed, social competence describes the ability of a child to fulfil personal needs in a social situation without harming or disadvantaging someone else or violating social norms. Developmental prerequisites for this are the ability to take perspectives of third parties and empathy, but also emotional competencies: Emotionally competent children perceive and recognize emotions in themselves and in others, e.g., they know the corresponding body signals, facial expressions, etc., and know how to regulate emotions. At preschool and elementary school age, for example, they also learn to deal with ambivalent emotions or to express and regulate their emotions appropriately in complex social situations. Children with high social and emotional competencies also have higher skills associated with academic outcomes, such as executive functions (e.g., impulse control, attention control), as these skills are central to the development of learning related social skills (Scheithauer et al., 2019, p. 49). The fostering of emotional and social competencies in early childhood thus represents an important starting point for better important life skills and a positive developmental trajectory into adolescence and adulthood (cf. Domitrovich et al., 2017).

After more than 20 years of program development, evaluation, and development of implementation approaches, three programs (Papilio-U3, Papilio-3to6, Papilio-6to9) are available for implementation in the field of early childhood education and care (ECEC) in Germany, which can reach children, their parents, educators and teachers to foster children aged 0 to about 9 years in their basic emotional and social development and prevent behavioral and emotional problems. Originally developed for the preschool context (targeting preschool teachers and 3- to 6-year-old-children), the preventive intervention program has been expanded since 2016 to include the age groups of first and second graders and under-three-year-olds. This thematic issue aims to introduce the three programs and to present the overarching framework of the Papilio approach.

Articles of the Thematic Section

Scheithauer et al. (2022) present the program Papilio-3to6, its implementation into everyday ECEC, and results from an effectiveness and fidelity evaluation study. Papilio-3to6 is “a universal preventive intervention program that focuses on social-emotional skills, and cooperative peer relations in early childhood (age 3 to 6) to prevent the onset of emotional and behavioral problems” (p. 83f). It targets children in ECEC centers and their preschool teachers who are trained to implement the program’s measures. Presented results from the evaluation study demonstrate the effectiveness of the program, in comparison to the control group, regarding multiple outcome variables, and indicate the positive impact and feasibility of the program.

Ortelbach et al. (2022) present the program Papilio-U3, a universal preventive intervention program for the ECEC context, fostering positive and sensitive preschool teacher-child interactions as well as fostering children’s early social-emotional competence, and secure child-teacher attachment relationships. They describe the program development, following the Intervention Mapping Approach (IMA), the evaluation design, and report first results of the formative evaluation derived from the pilot evaluation study, with promising results.

Lechner et al. (2022) present the program Papilio-6to9, a program for elementary school children and their teachers. The universal, school-based prevention program Papilio-6to9 aims at facilitating the transition from preschool to elementary school, improving social-emotional competences, and preventing behavior and emotional problems, with the long-term aims to foster academic performance and competences trough increased learning motivation and executive functions. The development of this program also followed the steps of the IMA.

All three programs build on each other in terms of content, methodology, and implementation approach. The focus is on the fostering of emotional and social competencies, including behavior and emotion regulation, or important precursor conditions, as well as the prevention of emotional and behavioral problems. Each program makes use of age-specific methods and includes the fostering of further targeted, age-specific outcomes (e.g., attachment security in the Papilio-U3 program or learning-related social skills and executive functions in the Papilio-6to9 program). A vital strength of the Papilio approach is its sustainability: Preschool and elementary school teachers are program implementers, because they are “central change agents” with a consistent presence in the classroom enabling them to foster children’s social-emotional development. Teachers are equipped to implement the program by the time they attend the first training session and continue to integrate the acquired knowledge and skills in their daily routines and interactions with the children. ECEC institutions are key settings where any deficiencies in social-emotional and problem-solving skills may be addressed. All of the three programs are universal preventive intervention programs, directed toward the entire group of children or classroom while additional indicated program elements focus on remediating skill deficits and reducing the existing problems of children, e.g., with behavioral disturbances. This way, stigmatization of children with deficits is avoided.

Three main elements are part of all three programs: The programs combine measures of developmentally appropriate practice, and measures of social-emotional learning to foster, e.g., emotional and social competence, with strategies of developmentally appropriate prevention, e.g., of behavioral and emotional problems.

Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

SEL is crucial for a child’s development and a proven method to foster children’s cognitive, social, and emotional development. The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2020) defines “social-emotional learning as ‘an integral part of education and human development’ through which children, adolescents, and adults are enabled to deal with emotions, show empathy and make caring decisions considering personal and collective aims” (Lechner et al., 2022, p. 100). Social-emotional learning includes: Learning to recognize and regulate emotions, developing care for other human beings (compassion and prosocial behavior), setting positive goals and making responsible choices, establishing and maintaining positive relationships, and being able to solve problems constructively (Scheithauer et al., 2019).

The long-term, positive effects of SEL are well documented. For example, in a meta-analysis, Durlak et al. (2011), summarizing 213 studies involving 270,034 children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years on the implementation of SEL programs, reported: Children or adolescents who participated in systematically implemented SEL programs demonstrated higher social and emotional competencies, more positive attitudes toward self and others, more positive social behavior, less problem behavior, less emotional distress, and an average 11% improvement in school performance. In a meta-analysis of follow-up studies of intervention effectiveness (with follow-up intervals of 6 months to 18 years postintervention) Taylor et al. (2017) also proved SEL’s long-term enhancement of positive youth development, e.g., regarding social-emotional skills, attitudes, and indicators of well-being. Thus, it can be concluded that SEL measures should be an important component of preventive interventions in the field of ECEC.

Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) for ECEC

The development and implementation of the programs follows principals of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) (e.g., National Association for the Education of Young Children [NAEYC], 2009). DAP describes standards for teachers in school institutions and elementary schools for the education, upbringing and care of children, quality assurance, as well as professionalization of the professionals. DAP uses “methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approach to joyful, engaged learning” (NAEYC, 2020, p. 5). DAP can be characterized as follows: involving a curriculum which helps to actively engage children; children learn through teacher–supported play; children are encouraged in their initiatives and making choice; involving a curriculum that fosters children’s optimal development and learning (Copple & Bredekemp, 2009, in Mengstie, 2022). For (preschool) teachers, educators, etc., this means taking into account what is known about children’s development and learning at this age and incorporating children’s individual needs and competencies accordingly. (Preschool) teachers should orient the care, upbringing, and education of young children to their age group with its specific characteristics and to their individual idiosyncrasies. A teacher of an ECEC center, for example, behaves in a developmentally appropriate manner if he or she takes into account what is known about children’s development and learning (e.g., typical developmental trajectories and phases) and which materials, activities, tasks, interactions, experiences, etc. are safe, healthy, interesting, attainable, and challenging or even manageable for the respective age group. He/she takes into account what is known about the strengths and weaknesses, needs and interests of the individual children in the group and has knowledge of social and cultural milieus from which the children come.

Developmentally Appropriate Prevention

The development of the programs followed principals of developmentally appropriate prevention of behavioral and emotional problems (e.g., Tremblay & Craig, 1995). Developmentally appropriate prevention takes into account developmental psychology findings, e.g.: knowledge about the typical development of a child; differences in the level of development within an age group; different meaning of “conspicuousness” depending on age (e.g., testing limits); influence of important developmental steps on a child’s behavior. Developmental prevention aims to reduce risk factors and promote protective factors that are known to influence the (positive or negative) development of an individual (Scheithauer et al., 2019).

Developmentally appropriate prevention, e.g., of aggressive behavior, considers findings and principals of developmental science, e.g., the reciprocal influence of normal and maladaptive (psychopathological) development as well as a biopsychosocial perspective (cf. Malti et al., 2009; Scheithauer & Niebank, 2022). Thus,

“developmentally appropriate interventions or preventions should build on empirically and theoretically derived models of normal and abnormal developmental pathways, and on evidence about those factors that facilitate and [foster](. . .) child development, and those that hinder it, by (1) reducing the impact of important risk factors and fostering those factors that protect children from [e.g.] developing aggressive / antisocial behavior and enhance their resilience, (2) helping children to complete relevant developmental tasks, and (3) considering key developmental transitions and cultural circumstances in which children and adolescents grow up.” (Malti et al., 2009, p. 216).

For example, the Papilio-3to6 program –following a developmentally appropriate prevention approach –prevents, beside emotional and behavioral problems in early childhood, later aggressive, violent behavior in childhood/adolescence unspecifically (by fostering important social and emotional skills), as well as substance abuse in adolescence (cf. Webster-Stratton & Taylor, 2001).

Outlook - Combining Programs Within the Framework of the Educational Approach for ECEC: Papilio-0to9

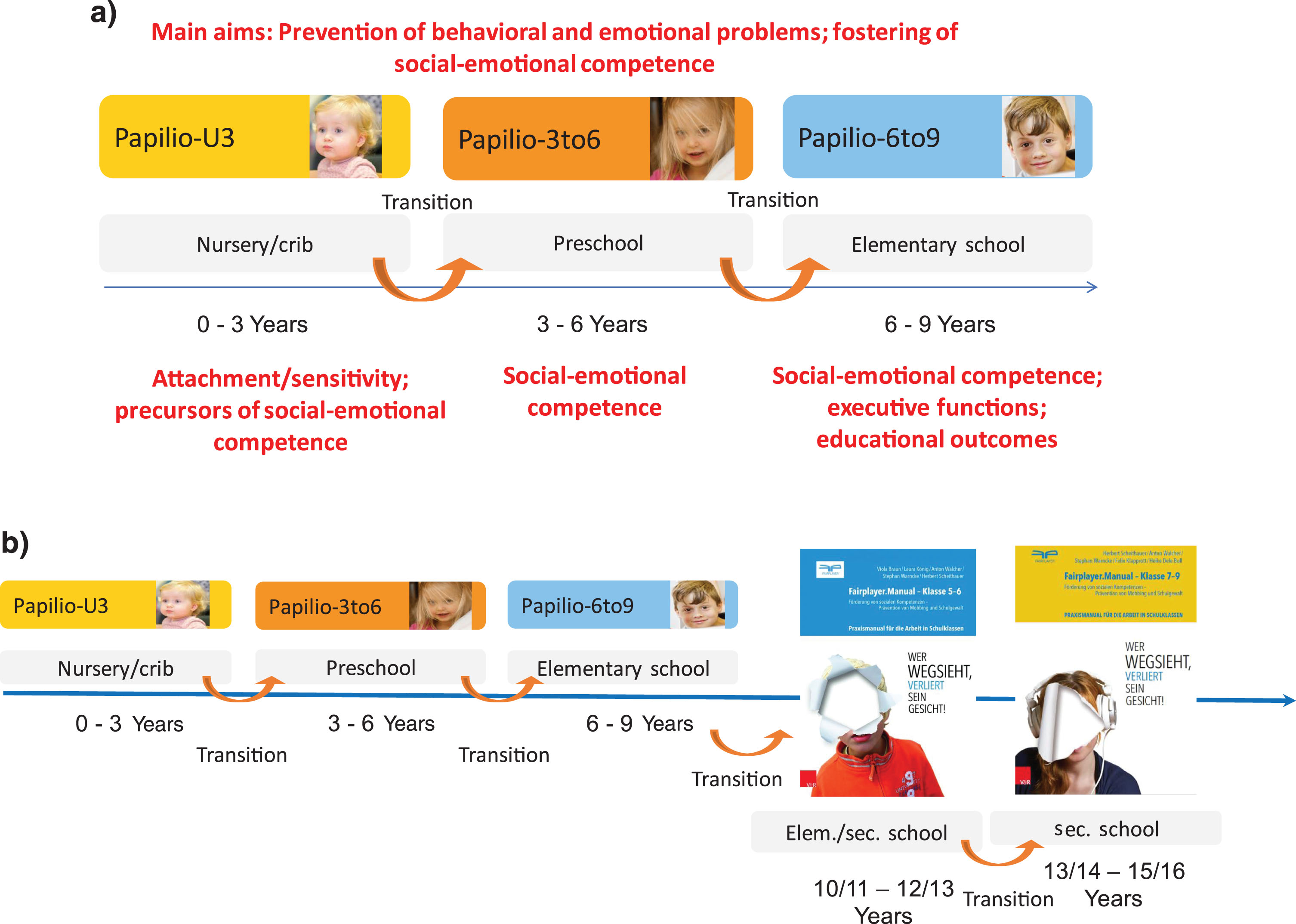

Each of the three Papilio programs takes a developmental approach on its own, with age-specific emphasis regarding developmental outcomes and developed methods. However, the programs were designed in such a way that they can also be combined –e.g., in the context of implementation in communities –and thus children aged 0 to 9 years can go through all three programs one after the other. This combined implementation also makes sense against the backdrop of the diverse requirements that children must successfully master in early development. For example, the transition to childcare is certainly the first major transition in the life of most children. Another important transition is the one from informal preschool settings to formal schooling. Associated developmental tasks such as adapting to classroom routines and a new (school) environment or an increase of structured teacher-directed academic activities make new demands on children. For this reason, it is important to accompany the children and their families during these important developmental transitions (see Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Combination of the Three Papilio Programs for the ECEC Context (a) and Combination with Additional Programs (b) in Secondary School.

In addition, it is possible to combine Papilio programs at other key developmental points (e.g., transition to secondary school), e.g., with bullying prevention programs that also use similar methods, such as SEL, and focus on social and emotional skills. Examples would be the Fairplayer.Manual-Grade 5-6 (Braun et al., 2019). and Fairplayer.Manual-Grade 7-9 (Scheithauer et al., 2019) programs (see Fig. 1b), which were also developed in our working groups. This would correspond to a developmental approach to violence prevention, with nonspecific interventions in early childhood and specific interventions in childhood/adolescence.

In summary, with the basic developmental orientation, the incorporation of the developmentally appropriate practice approach, and the implementation approach chosen, the Papilio programs collectively represent a developmentally oriented educational approach for ECEC and for children ages 0–9.

References

1 | Braun, V. , König, L. , Walcher, A. , Warncke, S. , & Scheithauer, H. (2019). Klasse: Förderung von sozialen Kompetenzen 5–6: Prävention von Mobbing und Schulgewalt. Praxismanual für die Arbeit in Schulklassen [Fairplayer.Manual-Grade 5-6: Fostering of social competence –prevention of bullying and school violence. Manual forworking with school classes]. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. |

2 | Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2020, March). Fundaments of SEL. https://casel.org/what-is-sel/ |

3 | Domitrovich, C.E. , Durlak, J.A. , Staley, K.C. , & Weissberg, R.P. ((2017) ) Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Development, 88: (2), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12739 |

4 | Durlak, J.A. , Weissberg, R.P. , Dymnicki, A.B. , Taylor, R.D. , & Schellinger, K.B. ((2011) ) The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82: (1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x |

5 | Lechner, V. , Ortelbach, N. , Peter, C. , & Scheithauer, H. ((2022) ) Developmentally appropriate prevention of behavior and emotional problems and fostering of social and emotional skills in elementary school – Overview of program theory and measures of the preventive intervention program Papilio-6to9. International Journal of Developmental Science 16: (3-4), 99-118. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-220335 |

6 | Malti, T. , Noam, G.G. , & Scheithauer, H. ((2009) ) Editorial: Developmentally appropriate prevention of aggression –Developmental science as an integrative framework. International Journal of Developmental Science, 3: (3), 215–217. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-2009-3301 |

7 | Mengstie, M.M. (2022). Preschool teachers’ beliefs and practices of developmentally appropriate practice (DAP). Journal of Early Childhood Research, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X221145464 |

8 | National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. A position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children. http://www.naeyc.org/files/naeyc/file/positions/PSDAP.pdf |

9 | National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) ((2020) ), Position statement on developmentally appropriate practice in programs for 4- and 5-year olds. Young Children, 41: (6), 20–29. https://www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap/contents |

10 | Ortelbach, N. , Bovenschen, I. , Gerlach, J. , Peter, C. , & Scheithauer, H. ((2022) ) Design, implementation, and evaluation of a preventive intervention program to foster social-emotional development and attachment security of toddlers in early childhood education and care: The Papilio-U3 program. International Journal of Developmental Science 16: (3-4), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-220336 |

11 | Scheithauer, H. , Braun, V. , Adam-Gutsch, D. , Ortelbach, N. , & Peter, C. (2019). Sozial-emotionales Lernen in der Kita –Basis einer gesunden Entwicklung [Social-emotional learning in the daycare center – the basis of healthy development]. In BVKJ Berufsverband der Kinder- und Jugendärzte (Eds.), Psychosomatik im Kinder- und Jugendalter (Thematic Issue) (pp. 49-52). |

12 | Scheithauer, H. , Hess, M. , & Niebank, K. (2022). Risikound Schutzfaktoren, Resilienz und entwicklungsorientierte Prävention [Risk and protective factors and developmentally appropriate prevention]. In H. Scheithauer, & K. Niebank (Eds.), Entwicklungspsychologie –Entwicklungswissenschaft des Kindes- und Jugendalters (pp. 493-519). Pearson. |

13 | Scheithauer, H. , Hess, M. , Zarra-Nezhad, M. , Peter, C. , & Wölfer, R. ((2022) ) Developmentally appropriate prevention of behavioral and emotional problems, social-emotional learning, and developmentally appropriate practice for early childhood education and care: The Papilio-3to6 program. International Journal of Developmental Science 16: (3-4), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-220331 |

14 | Scheithauer, H. , & Niebank, K. (Eds.) (2022). Entwick-lungspsychologie – Entwicklungswissenschaft des Kindes- und Jugendalters. [Developmental psychology – developmental science of childhood and adolescence]. Pearson. |

15 | Scheithauer, H. , Walcher, A. , Warncke, S. , Klapprott, F. , & Bull, H. D. (2019). Fairplayer.Manual –Klasse 7–9: Förderung von sozialen Kompetenzen –Prävention von Mobbing und Schulgewalt. Theorie- und Praxismanual für die Arbeit mit Jugendlichen in Schulklassen (4. Auflage) [Fairplayer.Manual-Grade 7-9: Fostering of social competence –prevention of bullying and school violence. Theory book and manual for working with adolescents in school classes]. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. |

16 | Taylor, R.D. , Oberle, E. , Durlak, J.A. , & Weissberg, R.P. ((2017) ) Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88: (4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12864 |

17 | Tremblay, R. E. , & Craig, W. M. ((1995) ). Developmental crime prevention. In M. Tonry & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Building a safer society: Strategic approaches to crime prevention (pp. 151–236). The University of Chicago Press. |

18 | Webster-Stratton, C. , & Taylor, T.K. ((2001) ) Nipping early risk factors in the bud: Preventing substance abuse, delinquency, and violence in adolescence through interventions targeted at young children (0–8 Years). Prevention Science, 2: (3), 165–192. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011510923900 |

Bio Sketches

Herbert Scheithauer is Professor for Developmental and Clinical Psychology at Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany, and Head of the Unit “Developmental Science and Applied Developmental Psychology”. His research interests are on bullying, cyberbullying, and the development and evaluation of preventive interventions.

Heidi Scheer is the managing director of Papilio gGmbH (limited). She has a diploma in health management, is certified as a Papilio trainer. Her topics are prevention in early childhood from 0 to 9 years. Besides managing the organization and fundraising she gives trainings for Papilio trainers.