Celebrating serendipity and collaboration

Abstract

Although every career has its own unique trajectory, when I look back at my own path to my present position at the University of Florida (UF), it was entirely unplanned and unanticipated, yet in hindsight, the pieces all fit together quite neatly. The progression from a compulsive reader signing up to work in her 8th grade library so she would have better access to the books to the Dean of University Libraries at a large research-intensive public university seems almost inevitable. The opportunity to observe, and participate in, the transformation of the way information is produced, delivered, analyzed and preserved from the perspective of small special libraries and large academic research libraries, as well as from government agencies and information companies, has been both exhilarating and challenging. However, while we do many things differently now because of the opportunities that technology has brought, we continue to share a common goal of providing essential, reliable information to users at the point of need and to seek ways to develop and employ technology to improve the accuracy and efficiency with which we accomplish that goal. Although we may compete to be the first or the best, and some of us are motivated by profits and others have the opportunity to deliver “free” (no fee) or not-for-profit services, we are not adversaries. This paper will demonstrate that we are colleagues who can and do benefit from collaboration and learn from one another.

1.The journey begins

By the time I graduated from college, I had worked in my junior and senior high school libraries and my college library and had summer jobs in four special libraries. I went to graduate school at The Catholic University of America with the specific intention of working in special libraries (the first and probably the last intentional act in my career planning and execution). I did spend a decade in special libraries, first establishing the technical library for COMSAT Laboratories, the research facility for the Communications Satellite Corporation, then establishing an information center for an NSF-funded research project on the diffusion of innovation, and then finally setting up and managing the information services for the Congressional Office of Technology Assessment (OTA). It was at COMSAT that I first recognized that a research library was an essential tool for its patrons, as valuable as any expensive piece of laboratory equipment, both for its content and its services. This perspective has been reinforced throughout my career and is particularly relevant in my current position. I also learned to welcome the challenge and embrace the opportunities presented by new technology. If I ever lose that, I will know it is time to retire!

I was recruited to work in product development for an information company in Denver while working at OTA. That position changed the trajectory of my career. It led to engagement with the Information Industry Association (now the Software and Information Industry Association) and NFAIS™ (The National Federation of Advanced Information Services), and eventually to other jobs in the industry in product development, acquisitions, marketing and government relations.

Later, while working for Lexis-Nexis (then Mead Data Central), I was appointed to the Depository Library Council, the first member who was not a government documents librarian. I was chosen because I had experience with electronic databases, CD-ROM publishing, and telecommunications. The Government Printing Office (GPO), as it was named at the time, was preparing for electronic distribution of government publications to depository libraries and needed someone with relevant experience. That in turn led to an invitation to move back to Washington and work at GPO, where I planned for the transition to a more electronic Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) and set up the Office of Electronic Information Dissemination Services. I was there when the legislation passed to establish GPO Access, subsequently known as the Federal Digital System (FDsys) and now transforming into govinfo (https://www.govinfo.gov/).

When we launched GPO Access, it was a database that delivered only ASCII text, but what our users wanted (as did the users of commercial information services such as Lexis and Westlaw) was the typeset versions of the Federal Register, Congressional Record and other government publications. Shortly after launch, GPO received a visit from Adobe to show us a pre-release version of the Portable Document Format, and that changed everything. Magically, we could deliver a searchable, typeset version derived directly from the printing process. As a result, I had the opportunity to collaborate with representatives of Adobe to demonstrate both to government agencies and at several industry conferences the way in which GPO was using the application. The users of GPO Access were wildly enthusiastic. Agency publishers and the information industry quickly adapted their services to take advantage of the new capability.

Shortly after leaving GPO, I went to work for the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science (NCLIS), which was later merged into the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). NCLIS was a tiny agency with only five employees and fifteen part-time Presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed Commissioners, with a big responsibility for advising the White House and the Congress on the information needs of the American people. NCLIS only generated a few reports and recommendations each year, but it was involved in so many important aspects of information policy: kids and the Internet, information services for people with disabilities, the role of public libraries in the provision of internet access (long before we even imagined access on our cell phones and iPads), and the role of libraries in response to terror attacks and natural disasters, to mention but a few. When the agency closed in 2008, I was one of the authors of the final report summarizing its accomplishments and identifying future initiatives that remained to be addressed [1].

Many of the NCLIS reports, most of which are available online in the UF Digital Collections (http://ufdc.ufl.edu/NCLIS), are as relevant today as they were when they were issued. Although the technology has changed dramatically, the issues and the importance of access to information remain constant. For example, in 2000–2001, NCLIS undertook a major project to assess the then-current state of government information policy and propose a comprehensive reform to simplify and clarify the Federal government’s commitment to public access to its information [3]. In that report, the Commission recommended that the “United States Government formally recognize and affirm the concept that public information is a strategic national resource.” It also recommended “the inclusion of a standard provision in the enabling legislation for each agency incorporating public information dissemination as a primary agency responsibility integral to its mission.” Currently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the only cabinet-level agency in the U.S. government that has dissemination of information in its core mission – the primary legislative language establishing the agency and charging it with its fundamental responsibilities.11 These legislative proposals are as necessary – and perhaps even more necessary – today as they were then.

From NCLIS, I returned to GPO as the Superintendent of Documents, the second librarian and first woman to serve in that position. When I was there the first time, we projected that within ten years the FDLP would transform from a program that was disseminating government information primarily in print into one that was primarily electronic – and we were right. In ten years, the FDLP went from 95% print distribution to 95% electronic access, and most of the items that remained in print were also available in electronic form.

GPO had successfully migrated from hot metal to electronic technology for the production of its print publications many years before, but the transition to electronic dissemination and access, with the resulting decrease in printing, was more difficult for both the agency and the Federal Depository Library Community. During this time, GPO was given early access to the technology to apply digital signatures the electronic documents. This was particularly reassuring to the government documents librarians who trusted the authenticity of print and their ability to preserve it for future generations. Acceptance of digital access in addition to print access was relatively easy. Acceptance of digital access without print access was not! But government publishing had changed, the information industry had changed, and user expectations had changed. There was no way to put the genie back in the bottle – even if we had wanted to do so.

2.The journey continues

In hindsight, perhaps it is not surprising that the University of Florida would be open to hiring as dean of university libraries someone one who had not worked in an academic library since she graduated from college, but who had been broadly and deeply involved in the policy and technological changes that had transformed government and commercial publishing, and who had led the transformation of the FDLP from print distribution to electronic access, both at the beginning of the process and as it began to resolve a decade later.

Although each of these positions became a building block for my future positions, it would have been difficult starting my career, or even at the midpoint, to anticipate and plan for the opportunities that were to come. I could not have imagined, let alone planned, to move from special libraries to the information industry and then to government, culminating in my current position in academia. Although it is extremely hard to control the forward motion of a career, I suppose it does help to have a goal to guide the choice of intermediate opportunities as they arise. My career has been much less intentional, and has both surprised and delighted me as it progressed. If I had to choose a single word to describe my path, it would be serendipity.

When I went to UF, I was already active in NFAIS™, having served as the member representative for GPO, and I was on the NFAIS™ Board. I continued as a member representative for the Smathers Libraries at the University of Florida – the first academic research library to become a member – and I remained on the Board. When I told my staff that the Libraries were joining NFAIS, they asked me why, and I read them the mission statement. (There have been slight modifications through the years, but it is substantially the same.) It currently states, “The National Federation of Advanced Information Services (NFAIS™) is a global, non-profit, volunteer-powered membership organization that serves the information community – that is, all those who create, aggregate, organize, and otherwise provide ease of access to and effective navigation and use of authoritative, credible information.” Our Libraries do all of those things! In fact, we recently established the LibraryPress@UF, which is an imprint of the University of Florida Press, so we are now officially a publisher as well as a research library system.

3.Outreach and collaboration

Through the years, as my staff have participated in various NFAIS™ seminars, webinars, and conferences, each person has returned saying something like: “When we go to library meetings, we are talking to people like ourselves. When we go to NFAIS™ meetings, we are talking to people from different types of organizations who are trying to solve the same problems – and we learn so much!” They come back with new approaches and innovative solutions, having learned from both conversations and presentations.

They have also learned to respect their new colleagues – and it is that acceptance of the people that they have encountered through NFAIS™ that has led UF to participate in two important projects – a bilateral collaboration between the Smathers Libraries and Elsevier22 that has recently expanded through the Clearinghouse for Open Research of the United States (CHORUS) to include other publishers. Both of these projects demonstrate collaboration between academic libraries and publishers for interoperability of information systems that provide mutual benefit.

In conversations with my Provost, Vice President for Research, and the faculty senate research council over several years, I was asked repeatedly why the Libraries couldn’t solve the problem of identifying UF faculty research publications with minimal burden on our very busy faculty. There are many more academic faculty than library faculty, and they are very productive, generating over eight thousand journal articles per year, so we also needed a solution that placed minimal burdens on the library faculty and staff. These discussions became the impetus for approaching first Elsevier and then Chorus to explore opportunities for collaboration.

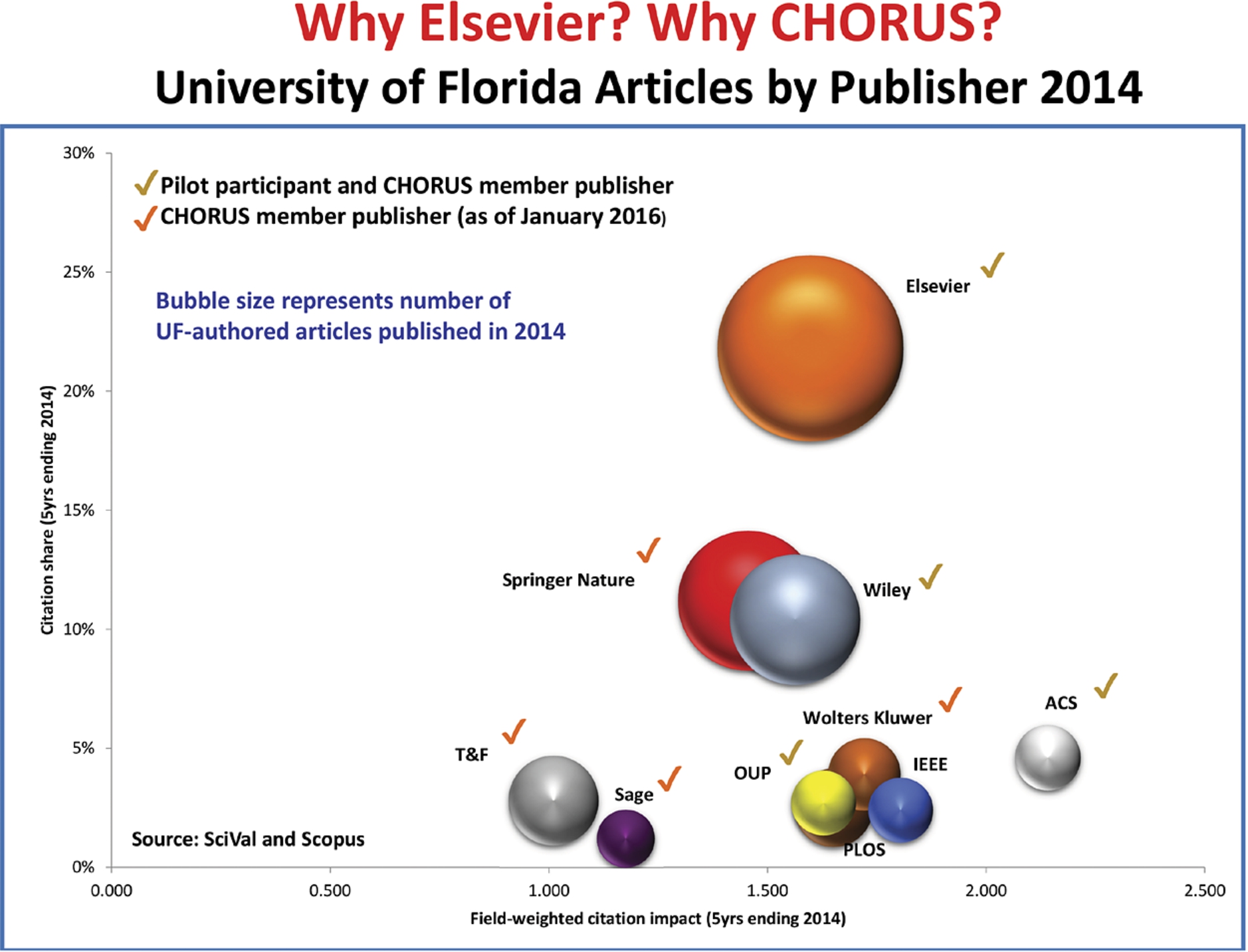

The most frequent questions I get asked about these two projects are why did I choose to work with Elsevier and CHORUS and why did they choose to work with UF. I think the images in Figs 1 and 2 answer those questions very effectively.

As shown in Fig. 1, eight of the ten publishers most selected by UF authors are CHORUS members. Elsevier has the largest volume of any publisher, with eleven hundred to thirteen hundred articles per year, followed by Springer/Nature and Wiley. Automated solutions for identification and access to articles by UF authors from multiple publishers reduces the burden on our academic faculty, the library faculty and staff, and by sharing data on compliance, on the staff of the compliance office under the Vice President of Research.

Fig. 1.

Why Elsevier? Why CHORUS? University of Florida Articles by Publisher 2014.

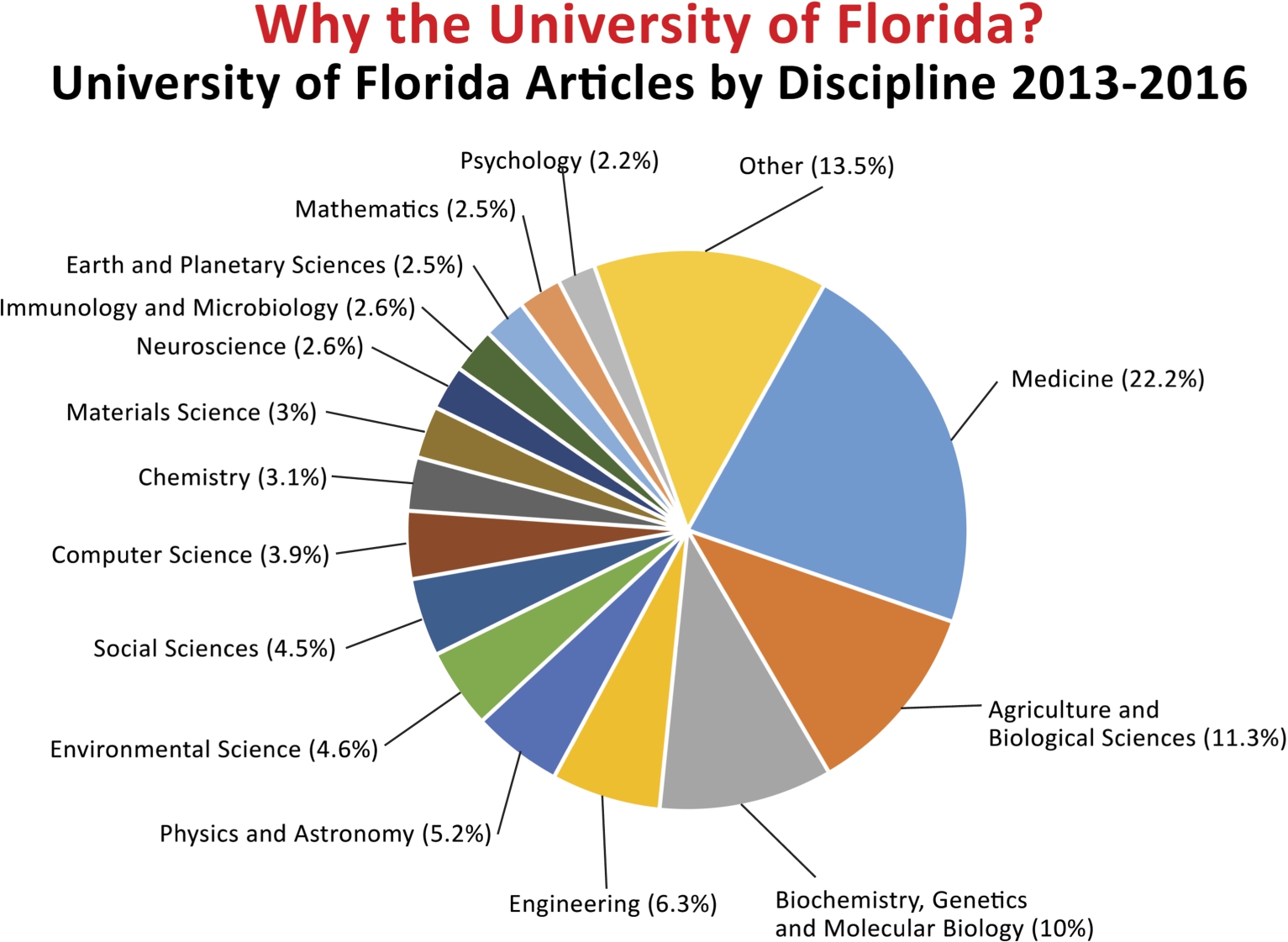

The inverse of that question is why would Elsevier and CHORUS choose to work with UF. First, because I asked! It helps to have a willing partner. Second, because UF is a large, comprehensive, research-intensive university. For example, UF ranks sixth in the US in the production of PhDs, with seven hundred and ninety-six awarded last year. Finally, UF authors publish in a wide variety of disciplines as shown in the Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Why the University of Florida? University of Florida Articles by Discipline 2014.

Since UF authors publish between eleven hundred and thirteen hundred articles in Elsevier journals each year, I approached Elsevier to see if I could obtain author manuscripts directly from them. I learned that Elsevier had recently developed Application Program Interfaces (APIs) to facilitate the identification and downloading of metadata for articles by university authors into local institutional repositories and was looking for a partner to test them. My staff quickly decided to use the APIs, rather than to continue to seek the manuscripts. This collaboration has provided real benefits to both UF and Elsevier. These include:

Collecting information without burden on UF faculty publishing in Elsevier journals.

Facilitating University oversight of compliance with public access mandates.

Achieving cost savings and efficiencies for the Libraries and UF through automation.

Testing and refining the Elsevier APIs to provide smooth scalability for engagement with future academic collaborators.

Improving understanding of publisher and academic library perspectives and addressing constraints inherent in these roles.

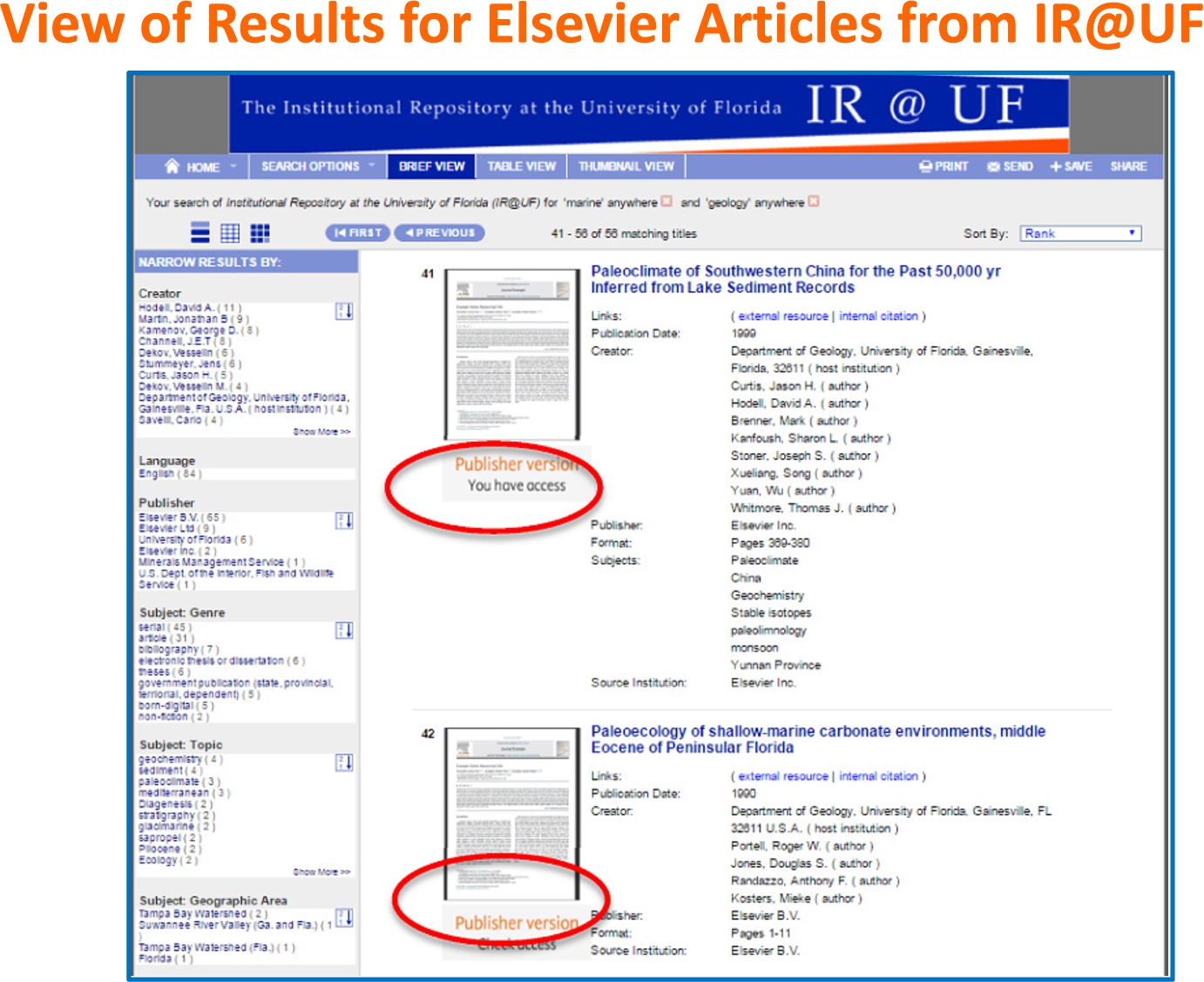

To put this in context, there is not a culture of deposit at UF. We had only seven Elsevier articles on deposit in the Institutional Repository (IR@UF) when the project started. They were all supported by the UF Open Access Publishing Fund, which required deposit of the final article in the IR@UF. We now have metadata for over thirty thousand articles by UF authors published in Elsevier journals, some as far back as 1949, and we are continuing to expand the scope of the project and to test new features.

Figure 3 is a screen capture of a two of these Elsevier articles as they appear in the IR@UF search results. The item with Check Access circled was published in 1990. UF does not own the backfile for that journal. Consequently, the Elsevier API identifies (correctly) that a user accessing the article from the UF IP range may not be entitled to access. A user from another institution with access to the backfile would see the message You Have Access. The API presents results that are specific to the status of the individual user.

Fig. 3.

View of Results for Elsevier Articles from IR@UF.

About the time that we began the Elsevier project, I attended a session on the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) mandate for public access to federally-funded research at which Howard Ratner spoke about the CHORUS project. He used a slide with the word compliance in the center and several figures surrounding it representing a funding agency, a publisher, the public, a librarian, and a researcher. I went up to Howard after his presentation about CHORUS and told him that the person on my campus who was losing sleep over compliance was not on his slide: the Vice President of Research. He accepted that friendly recommendation and we both continue to use versions of his original slide with that addition, as represented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Participants in Compliance with Mandates for Open Access to the Results of Federally-Funded Research.

I acknowledged the need to initially focus the development of CHORUS on publishers and funding agencies, but pointed out that this was a three legged stool and there were three figures from academic institutions (the librarian, the researcher, and, once added, the Vice President of Research) who were not participating in the design of the CHORUS system. I suggested that when they were ready, UF and other academic institutions should participate in the development of CHORUS to ensure that it met our needs as well as those of publishers and funders. A few months ago, Howard contacted me and said they were ready to expand the partnership. He asked if UF would participate, and I quickly agreed.

Elsevier is represented on the CHORUS Board and kept the Board informed about our bilateral project and that contributed to the willingness of other publishers to participate in the new collaboration. As a result, the seven publishers identified in Fig. 5 are working with UF and several other academic libraries on the pilot project.

Fig. 5.

Seven Publishers Participating in the CHORUS Pilot Working Group.

The most important goal of the CHORUS project is facilitating compliance. The steps CHORUS is taking are to identify articles by UF authors; check the metadata for the funding source; verify deposit in the appropriate funder repository; and report to UF through a dashboard that CHORUS is developing. The report might indicate that Professor Smith published an article based on a Department of Energy (DOE) grant and it is in the DOE-mandated repository, while Professor Jones published an article funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) that is not yet in the mandated repository. A subsequent report might confirm that Professor Jones’ article is now in the NSF repository. The UF compliance office will be informed about articles that have been published and can match them to the funding source in our grants management system. The compliance staff will only need to follow up on articles that are not yet deposited. Together we are developing an automated system that identifies UF faculty research publications with minimal burden on our very busy faculty and on the library faculty and staff and that will reduce the burden on the UF compliance office. The system will become even more valuable as more publishers participate.

As I said earlier, although some of us are motivated by profits while others have the opportunity to deliver “free” (no fee) or not-for-profit services, we are not adversaries. We are colleagues who can and do benefit from collaboration and learn from one another. When I look forward, that is the future that I see. We will continue to have divergent views over some policy issues and the libraries will continue to resist the annual price increases that go up faster than our budgets every year, but we will also learn from one another and find ways to benefit from collaboration.

4.Conclusion

There is an old African proverb that I often quote, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together!” The Smathers Libraries are active participants in a number of collaborative initiatives that provide significant benefits to our university, to our partners, and to others who share in the results of our efforts. Each of these initiatives requires a significant effort to establish and sustain trust and to maintain the value to the collaborators. Each step often takes longer to plan and to execute because a number of people have to be consulted and have their preferences and concerns addressed. Nevertheless, we continue to invest in these initiatives and to seek additional opportunities for deep collaboration because, in the end, they take us much farther than we can go alone, as the two projects I have described demonstrate.

Ultimately, every collaboration is a risk. They won’t all work well. They won’t all be sustainable. But we have to be open to the possibilities and able to identify the ones that are likely to pay off – and willing to recognize the value of the lessons learned from the ones that don’t. We need to be able to identify the risks, but focus on the benefits to our own institution and the others we seek to join us. We need to be able to convince others (internal and external) to participate, and we need the patience to persevere even though it is likely to take longer than expected.

And, to be honest, we won’t be able to convince everyone. Some colleagues in the library community were critical of my collaboration with Elsevier, but my own staff did not waiver from their belief that we were doing something important and worthwhile. I know that my own experiences in libraries, government, and the information industry made me more open to these collaborations and that the experience of my staff at various NFAIS meetings made them more confident in the face of criticism and more comfortable with their industry colleagues. I am very fortunate to have such talented and committed staff working on these projects and in the equally talented and committed participants from Elsevier and CHORUS.

Successful collaborations build trust and make the next collaboration with that partner (and perhaps with observers) easier. They surprise and delight, so even though it is hard work, the rewards both personal and professional are great – and it is more fun to travel with others than to travel alone. I am optimistic that there will continue to be more changes that will inspire and delight us as we pursue our common mission to “create, aggregate, organize, and otherwise provide ease of access to and effective navigation and use of authoritative, credible information” for the users we are all dedicated to serving. I fully expect that NFAIS will continue to be an important catalyst in that process.

About the author

Judith C. Russell has served as the Dean of University Libraries at the University of Florida since 2007. Russell was the Managing Director, Information Dissemination and Superintendent of Documents at the U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), now the Government Publishing Office, from 2003–2007. She served as Deputy Director of the U.S. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science from 1998–2003 and as director of the Office of Electronic Information Dissemination Services and the Federal Depository Library Program at GPO from 1991–1997. Russell worked for more than ten years in the information industry, doing marketing and product development as well as serving as a government–industry liaison. Her corporate experience includes Information Handling Services and its parent company, the Information Technology Group; Disclosure Information Group; Lexis-Nexis (then Mead Data Central), and IDD Digital Alliances, a subsidiary of Investment Dealers’ Digest. She also worked for more than ten years in special libraries. Russell is a past member of the Board of Directors of the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) and LLMC-Digital. She is also former member of the board and a past president of the Association of Southeastern Research Libraries (ASERL) and former member of the board and a past president of NFAIS (the National Federation of Advanced Information Services). She is active in the American Library Association and the Association for College and Research Libraries. Russell holds a Master of Science in Library Science from The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

Notes

1 “There shall be at the seat of government a Department of Agriculture, the general design and duties of which shall be to acquire and to diffuse among the people of the United States useful information on subjects connected with agriculture, rural development, aquaculture, and human nutrition, in the most general and comprehensive sense of those terms

2 For additional information about the early stages of the Elsevier project see [2].

References

[1] | N. Davenport and J. Russell, Meeting the Information Needs of the American People: Past Actions and Future Initiatives, a report from the U.S. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science (NCLIS), Washington, DC: NCLIS, 2008 (http://ufdc.ufl.edu/IR00000084/00001). |

[2] | J.C. Russell, A. Wise, C.S. Dinsmore, R.V. Phillips and L. Taylor, “Academic Library and Publisher Collaboration: Utilizing an Institutional Repository to Maximize the Visibility and Impact of Articles by University Authors,” Collaborative Librarianship, Vol. 8 (2016) (http://digitalcommons.du.edu/collaborativelibrarianship/vol8/iss2/4/). |

[3] | U.S. National Commission on Libraries and Information Science A Comprehensive Assessment of Public Information Dissemination: Final Report, 4 volumes, Washington, DC: NCLIS, 2001 (http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00038081/00001/allvolumes). |