Publishing in the doghouse: Protecting copyright, enabling access, or both?

1.The problem of access

It is a truth not universally acknowledged in our business that publishing is an industry with a reputation problem. We are not much loved by governments, who tend to see publishers as resistant to change, despite the remarkable record of the industry in its digital migration and its adoption of new business models. We are not much loved either by librarians, who see publishers as unfairly exerting their market power. They are little persuaded that the ‘serials crisis’ is the product of budgets failing to match the growth of research output. They are more likely to see ‘excessive’ price increases supporting ‘abnormal’ profits. Nor are publishers as much loved by the research community as we would like to think.

In some ways this is unsurprising. After all, publishers do typically reject something in the region of two thirds of the articles that are submitted to them. This means that for the majority of authors the process of publication starts with rejection. Added to which, that rejection often happens after weeks, sometimes months, of peer review, to be followed by a cycle of revision and re-submission, perhaps multiple times.

However, there are other factors at play here in the low regard researchers may have of publishers. Though we are usually aware that the experience of submission and peer review can be unsatisfactory and that we make access to publication difficult, we do not often recognize the problems we create in giving access to content. For customers brought up in a digital environment, the difficulties we create in gaining access to articles must be wholly incomprehensible. My contention here is that this is not just unfortunate for our customers, but threatening to the future of our industry. Access, by which I mean both lack of access and lack of ease of access, is perhaps the fundamental issue in the industry, and one which we ignore at our peril.

2.Ease of access

Some publishers reading this may ask, ‘What is the problem with ease of access? Aren’t pretty much all journals available these days in pretty much all research libraries?’ To which the answer, sadly, is that access isn’t universal, and isn’t always easy.

Take as an example a research student who happens to be off-campus, working from home. To be more specific, a PhD student at Cambridge, unquestionably one of the world’s leading universities, wanting to read an article in Econometrica, unquestionably one of the leading journals in Economics. Naturally, he begins his search with Google, and the object he is looking for is a PDF. For the great majority of graduate students, PDF signals ‘final version,’ and for them Version of Record means nothing.

A simple Google search serves up many versions of the article being sought, to be found in many places. It is a common and mistaken assumption of the publishing community that journal articles live only in the safe confines of their publishers’ sites, when in fact they are to be found in different guises outside the castle walls. They may appear in pre-print servers such as SSRN or RePEc. They may be on the author’s personal website, his departmental site, or in his institutional repository. They may indeed be found on Social Collaboration Networks such as ResearchGate or Academia.edu. In this example, Research Gate may be offering a PDF, one that can be downloaded in a couple of clicks with no registration required. Even if that PDF is not in fact the final published version, it may be good enough.

By contrast, what happens if our graduate student decides to find the article on the publisher’s site, Wiley Online Library? Because he is not on campus, the system we know as IP Authentication doesn’t work. He is served up with the abstract of the article he wants, but needs to click on to read the full article. Here he is presented with puzzling choices. Does he want to buy the article? Does he want to rent it? As a Cambridge student he assumes he has free access, and so is asked either to log in via Open Athens or search via Shibboleth. But how many publishers, let alone students, know what those are? At this point, he’s shooting in the dark. He chooses Open Athens, searches on Cambridge, to find multiple hits, all of them irrelevant. He finds the East of England Ambulance Service, for example, or Cambridge Journals Online, but not the University of Cambridge. Little does he know that his university does not use Open Athens. Time to start again. A search on Shibboleth does take him to his library login, and finally to the article.

His search therefore took him seven or eight steps to arrive at what we publishers call the Version of Record. Two clicks would have taken him to a good-enough version on ResearchGate. So, in this example, we have a problem with ease of access. More generally, we have two problems with access. Some customers simply don’t have access. Others do, but we make getting access unnecessarily difficult for them. In a digital environment, lack of access drives piracy, and lack of ease of access drives customers towards simple one-click solutions. This is evident in other media, taking music and film as examples. But is there evidence to support that assertion in the publishing industry?

3.Drivers of site visits

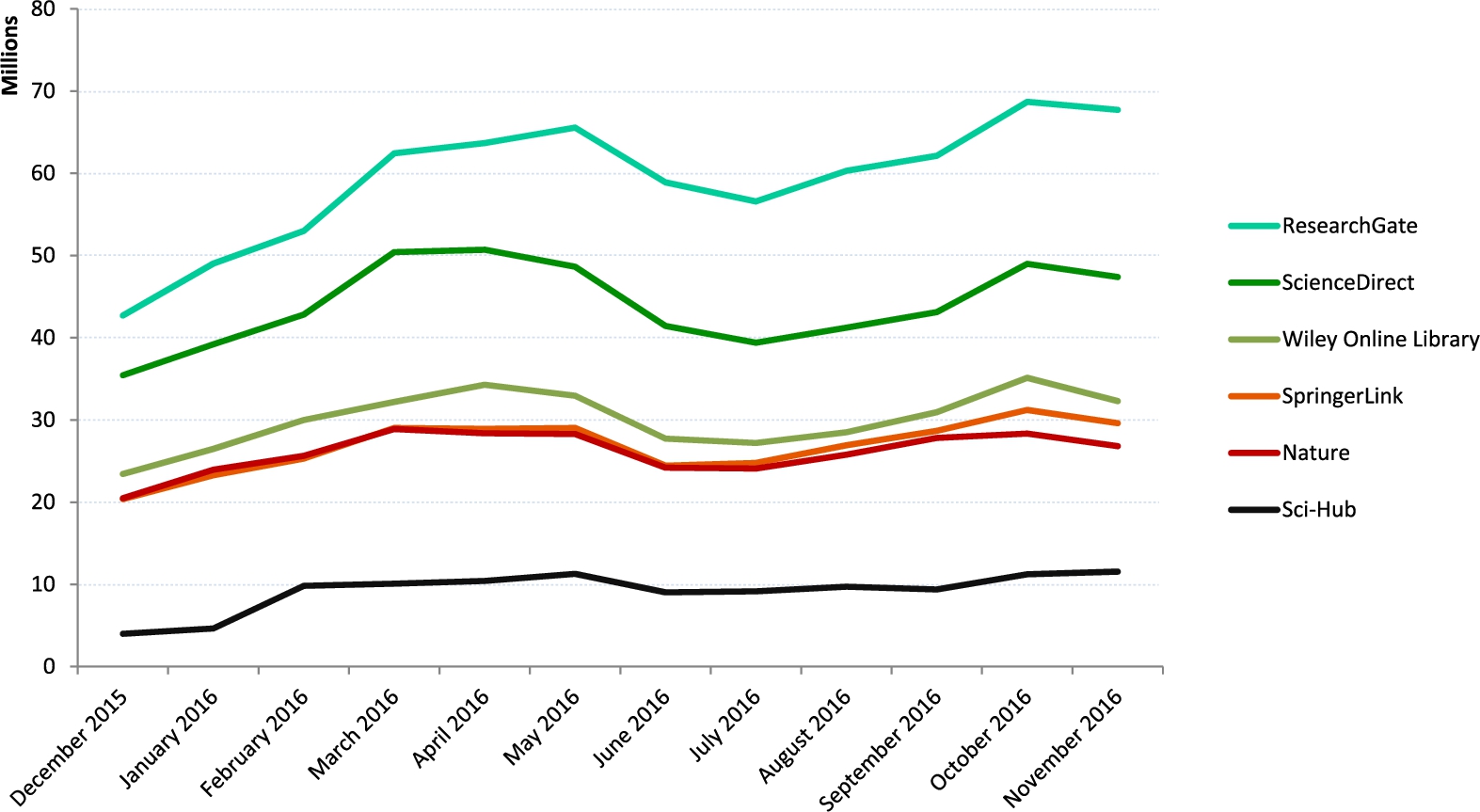

Figure 1 quantifies site visits for the three major publishers during 2016, and in addition for the pirate site SciHub and the Social Collaboration Network ResearchGate. The first striking observation is that visits to the ResearchGate platform are substantially greater than to any single publisher site. One may say that these data are for site visits, not for article downloads. True enough, but let’s assume that many of those visits are to obtain content. One may then say that what users are downloading may not be the final published version of articles. But the status of the article, be that the submitted version, author’s version, or version of record, may matter less to the reader than publishers may like to think. And finally one may say that many of those articles hosted on ResearchGate are there in violation of copyright. Recently published research [3] has suggested that this may be true for a half of the articles posted on the site, and that authors are posting them in contravention of their publisher agreement. Few would argue that they do so maliciously. It would be more fair to say that authors generally don’t understand or care too much about publishers’ arcane rules around copyright, licenses and embargo periods. That is not their business.

Fig. 1.

Comparative visits by site, past 12 months.

A second striking observation is that SciHub, unambiguously a pirate site, its status having been determined clearly in the New York courts, is a major presence in scholarly communications, whether publishers like it or not.

So what is driving these remarkable levels of usage? I would argue that the usage of Research Gate is mostly driven by ease of access. One click gives access to a great deal of content from a great many publishers. Estimates vary as to how much content is hosted on the site, but we can assume it is in excess of 10 million articles. ResearchGate claims in excess of 100 million, which would make it many times larger than Wiley Online Library. No matter what the real figure, that ease of access to a huge array of content is exactly what the digital consumer expects. It is what they receive from Amazon, where you can buy pretty much any book with one click, or from Netflix, with its vast range of movies.

Conversely, I would argue that the usage of SciHub is mostly driven by lack of access. It has been argued by John Bohannon [1] that researchers who have legal access to content are using SciHub because it is simply easier to navigate. It is certainly true that entering a DOI is all that’s needed to retrieve an article, and the number of articles is again very large. However, Fig. 2 tells a somewhat different story.

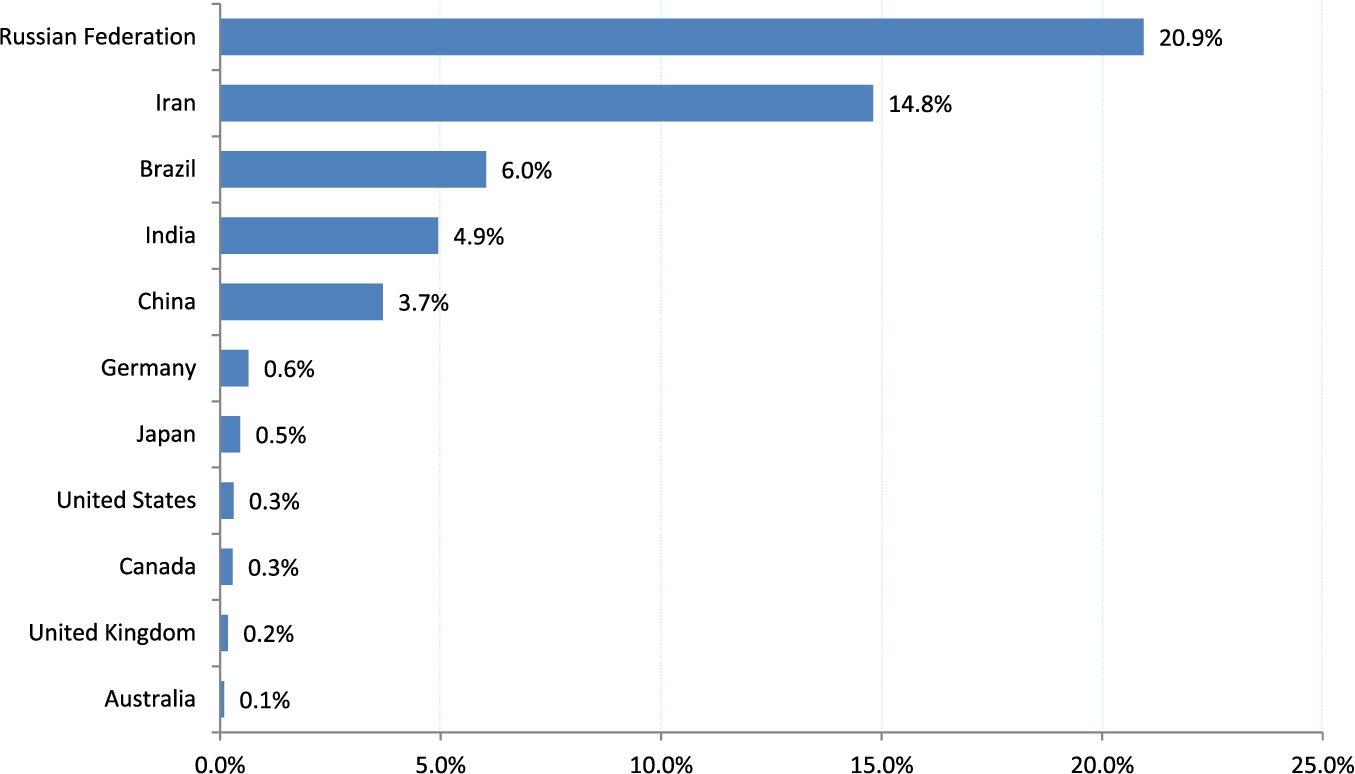

Fig. 2.

Download percentage on SciHub versus Wiley Online Library by country.

We can see that the percentage of downloads on SciHub compared with Wiley Online Library varies greatly by country, and appears to correlate with the availability of institutional resources. In the case of the Russian Federation, we know that for the period in question a significant proportion of researchers would not have had legitimate access, since funding for a large consortium license agreement with Wiley had been withdrawn. Similarly, we know that in Iran institutions affiliated to the Ministry of Science and Technology would not have had access, though those associated with the Ministry of Health would have done so. Conversely, the percentage of downloads on SciHub in the USA or the UK is very small.

The inference therefore is that lack of legitimate access is driving usage of a pirate site, consistent with the general supposition that, in a digital environment, lack of access drives users to find and use a pirate version.

Anecdotal evidence for this is not hard to find. For example, a Peruvian biologist commented as follows when his library system cancelled access to Science Direct for lack of funding:

‘I’m not worried. Downloading papers is rather easy now with SciHub… Now everyone uses SciHub. I’m 30 years old, and I would say that 95% of my generation uses it.’

(quoted in [4])

4.Competing with piracy

The point then is that for research publishing, as for all other digital media, once digital versions are released it is very difficult to control them. Steve Jobs commented appositely:

‘You’ll never stop [piracy]. So what you have to do is compete with it.’

(quoted in [2])

Pirates, we need to recognize, don’t just compete on price, or lack of it. They may offer other advantages too, such as convenience, timeliness or a better user experience. With that in mind, we need to ask how we can win against the pirates.

In the first place, we could choose to make our offering simply better: that is, more convenient, more timely, more usable, or all of these things. That, for example, is what Netflix did to compete with BitTorrent by making it so easy to watch on any device, while also removing the risk of having one’s computer infected. (See Smith and Telang [5] for discussion of this.)

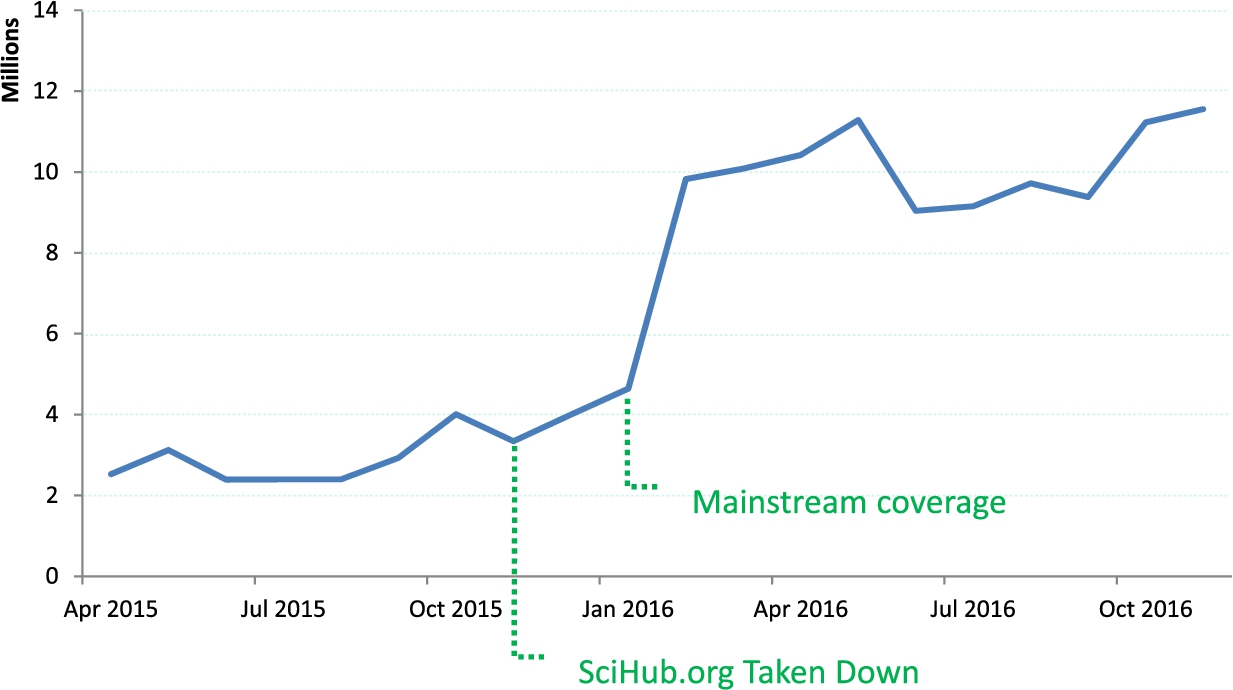

The alternative is to take the legal route. Litigation may make the pirate version less accessible, harder to use, less convenient, and quite obviously unlawful. That involves working through the courts, ideally with the support of government agencies. But this approach has its limitations. Figure 3 illustrates what happened when Elsevier, acting on behalf of the industry, successfully took action against SciHub in the New York courts.

Fig. 3.

SciHub usage by month before and after U.S. site taken down.

Newspaper reports subsequent to the ruling blew oxygen onto the flames, making a great many more aware of the site’s existence than before and doubling usage in a matter of weeks, with visits continuing to increase from that new higher point. In a depressing exercise of Whac-A-Mole, Elsevier successfully whacked the mole in the USA only for that very mole to reappear in Russia twice the size.

Is this to say that publishers should renounce litigation as a means of copyright protection against piracy and other forms of infringement? Of course not. But we do need to recognize the limits of that approach and that we cannot rely on it alone. We need to see that pirates and what we might call ‘para-publishers’ are competing not just on access but on ease of access too, and that if we are to thrive as an industry we need to grapple with those twin issues. If we fail to do that, we fail to meet out customers’ expectations and they will go elsewhere.

5.Enabling ease of access

Happily, there are existing initiatives taking the publishing industry forward, particularly a project known as RA21, sponsored by the STM Association working in collaboration with the Copyright Clearance Center and NISO [6]. RA21 starts from the recognition that the access control mechanism known as IP Authentication is a twenty year old technology that is no longer adequate to its task. In the first place it makes the theft of articles using compromised credentials simply too easy, and is consequently a threat to the digital security of the whole campus system. Secondly, for all its ease of use on campus, it is an impediment to today’s mobile researcher who may be working in Starbucks, on a train, or, as in our earlier example, at home.

The RA21 project has set out a number of principles which can be crudely summarized as follows. The industry needs to provide access that is as seamless as, for example, SciHub. It needs to provide secure personal authentication that is trouble-free for the user. And it needs a technology which stops the leakage of content.

Doing that much would put the industry on a competitive par, but it would not out-compete the pirates. That may require a more fundamental rethinking by publishers of their platforms. For example, they could seek to make their sites a place where researchers discover articles or other content they need and do their work, where now they function mostly as download stores, places where researchers grab PDFs and go. Though publishers will probably never regain control of search, they could win back control of discovery by using both content and user metadata to create content recommendations and discovery pathways for researchers.

More fundamentally, publishers need to stop thinking of their sites as sources of differentiation from each other. The pursuit of fractional competitive advantage through site development is surely a mistaken activity when publishers’ true competitors are not each other but pirates, para-publishers and other potential disruptors. To realize that is to create a collaborative agenda across the industry, one which will be to the benefit not just to publishers but to the community of researchers.

6.Protecting copyright, enabling access, or both?

My argument here has been that the protection of copyright is not, in itself, a sufficient or sustainable agenda for the publishing industry. To meet the needs of its digital consumer, it needs grapple more seriously with enabling access. That means providing access to more researchers and making access both simple and more secure.

My focus in this has been on some of the technology issues involved. However, there is much more that publishers are doing to enable access in other ways. Take for example Research4Life, a philanthropic scheme which gives access to research content for those countries that could not otherwise afford it. Publishers can and should do more to modernize the technology of that platform and simplify access authentication. Again, as both publishing and purchasing consolidate, we are seeing more license deal which give access either to whole national educational systems, or to whole national populations. That is the case, for example, with the Egyptian Knowledge Bank, a kind of digital, universal Library of Alexandria which gives access to huge swathes of research and educational materials to anyone with an internet connection. And not to be overlooked here are the very substantial investments publishers have made in Open Access publishing, in the creation of new journals and the complex systems which underpin a different business model.

As an industry, we should do more of those things, and we should be less reticent about discussing the many things we do to make the research literature pervasively available. That said, the publishing industry urgently needs to address the access question, because unless we out-compete the pirates, para-publishers and would-be disruptors we will be failing our customers and our future will be uncertain.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Danielle Reisch of Wiley for providing the data and analysis which appears in the figures and Will Carpenter of Cambridge University for his input on issues of access and the economics of the media industries.

References

[1] | J. Bohannon, Who’s downloading pirated papers? Everyone, Science, April 29, 2016. |

[2] | J. Goodell, Steve Jobs: The Rolling Stone interview, Rolling Stone, December 3, 2003. |

[3] | H.R. Jamali, Copyright compliance and infringement in ResearchGate full text journal articles, Scientometrics, February 2017. |

[4] | Q. Schiermeier and E.R. Mega, Scientists in Germany, Peru and Taiwan to lose access to Elsevier journals, Nature, January 9, 2017. |

[5] | M.D. Smith and R. Telang, Streaming, Sharing, Stealing: Big Data and the Future of Entertainment, The MIT Press, (2016) . |

[6] | STM Association, RA21: Research Access in the 21st century, stm-assoc.org/standards-technology/RA21. |