The relationship between e-marketing mix framework (4Ps) and customer satisfaction with electronic information services: An empirical analysis of Jordanian university libraries

Abstract

This study employs Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using Smart PLS 3.2.9 to offer valuable insight into the relationship between e-marketing mix (4Ps) and customer satisfaction with electronic information services provided by public university libraries in Jordan. The identified primary aspects within the e-marketing mix encompass e-product, e-pricing, e-place, and e-promotion. An online survey (questionnaire) targeting postgraduate student respondents at Jordanian public universities (a total of 792 participants) was used to gather data using a quantitative technique. Participants were chosen using voluntary response sampling. The study’s findings revealed that all relevant elements of the e-marketing mix establish significant relationships with customer satisfaction among postgraduate student respondents utilizing e-information services in public university libraries in Jordan. Notably, e-products, e-pricing, and e-promotion demonstrated substantial positive relationships with customer satisfaction. Conversely, there was a negative relationship observed with e-place. The novelty of this study lies in its exploration of the previously unexplored realm of the e-marketing mix framework (4Ps) in the context of customer satisfaction with electronic information services within university libraries in Jordan.

1.Introduction

The landscape of information technology has undergone a profound transformation with the advent of contemporary concepts like artificial intelligence, cloud computing, the knowledge economy, social media platforms, mobile applications, and the evolving nature of information recipients’ requirements [1]. This transformation has contributed the delivery, marketing, and accessibility of electronic information services, strongly emphasising customer experience and a deep understanding of their needs [2]. Within the academic domain, there is a consistent scholarly interest in integrating new technologies into marketing electronic services and products [3]. This focus is well-founded, as research consistently indicates that organisations heavily investing in new technology for marketing purposes enjoy enhanced flexibility, a robust competitive edge, and heightened levels of customer satisfaction compared to those that do not invest [4]. Many libraries, particularly university libraries, have recognised the advantages of incorporating new technologies into their electronic services. This recognition has prompted the development of methods to market these services, with e-marketing emerging as a notable approach [5]. The utilization of e-marketing and social networking sites for marketing in libraries, especially in response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, have proven to be strategic initiatives. These approaches contribute significantly to the enhancement and optimisation of the way libraries deliver their services to beneficiaries [6]. Additionally, this strategy is complementary in assisting students, researchers, faculty members, and administrators in elevating their cultural knowledge and research capacities, ultimately contributing to their satisfaction [7].

E-marketing is acknowledged as a successful and pivotal mechanism contributing to the survival and resilience of university libraries in the ever-evolving landscape of technology. It stands out as the most efficient means to swiftly deliver services and products that align closely with the evolving needs of users [8]. In addition to being the most effective way to increase users’ satisfaction with the library environment in terms of its e-products (services and resources), the time of submission of those products, subscription prices, electronic methods of distribution, and promotion [9]. As per Ubogu [10], libraries have historically maintained positive relationships with users, necessitating the adaptation of technological innovations to heighten user satisfaction. This becomes particularly relevant with the surge in the utilisation of electronic information services and the proliferation of e-information sources. Achieving this objective involves adeptly applying marketing techniques and effectively implementing marketing strategies [9]. Libraries, inherently user-centric, have long embraced marketing principles, predating the widespread recognition of the term in the library sector. Pioneering this approach were American libraries, utilizing marketing strategies and components to win beneficiaries’ and users’ material and moral support, especially during difficult times financially [11]. But recently, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the necessity of providing high-quality electronic information sources and services through e-marketing techniques has come into sharper focus [6]. In response, libraries have had to realign their policies and goals to engage beneficiaries through contemporary marketing techniques. These methods are increasingly employed as a daily marketing strategy, attracting beneficiaries and elevating their satisfaction levels [12]. Bouaziz’s research [13] emphasises the crucial role of e-marketing in Algerian university libraries, stating that it is essential for excellence and innovation in information services in line with the digitisation era. Mohapatra [14] asserts that embracing e-marketing is no longer optional but a requirement for libraries, considering it a successful business model. The e-marketing mix, being user-centric, is vital for satisfying customer needs and introducing tailored information services [10].

Technology, information, and communication resources are used efficiently, which is closely related to the rapid growth of electronic information services in Jordanian university libraries. Despite being crucial hubs for teaching, learning, and research, public university libraries in Jordan face concerns regarding user satisfaction, keeping up with technology, and librarians’ digital skills [15]. The digital era and challenges from the COVID-19 pandemic have further complicated matters, affecting user behaviour and needs [16]. Notably, postgraduate students, often tied to jobs, rarely visit the library, posing a challenge to ensuring their information service needs are met. To address the rising demand, libraries ought to use marketing techniques to advertise their e-resources and services [17]. Additionally, there is still a gap between users and electronic library services, especially among postgraduate students who are often unaware of available remote education support [18]. Low database utilisation and limited searches indicate the underutilisation of library services, exacerbated by weak marketing efforts [19]. Users’ perception of library websites as mere communication interfaces hinders optimal use [20]. To thrive in the competitive landscape, Jordanian public university libraries must embrace e-marketing strategies, utilising electronic means to enhance accessibility and user communication. Viewing e-marketing as an opportunity, not a challenge, is crucial for improving user satisfaction [10]. The researchers point out that previous studies conducted in numerous industries and nations have demonstrated the importance of the e-marketing mix in enhancing customer satisfaction. However, there is still a noticeable gap in the literature studying how the e-marketing mix affects consumer satisfaction in Arab countries, especially Jordan. Furthermore, contradictory findings on the connection between e-marketing and consumer satisfaction may be found in the research. While several empirical studies in industrialised nations support a positive impact between the commercial [21], economic [22], and internet shopping [23] sectors, other studies find no evidence of a meaningfully beneficial relationship [24].

The gap highlights the requirement for additional study and examination to provide an extra comprehensive understanding of the relationships between the e-marketing mix and customer satisfaction, especially in the context of Arab nations and Jordan’s special situation. Research on the connection between electronic marketing and consumer satisfaction in university libraries is lacking. This demonstrates Jordanian university libraries’ very low level of interest in the subject and emphasises the urgent need for further empirical study in this area. The absence of study results in this field highlights that, compared to other industries, university libraries in Jordan have not yet completely embraced the possibilities of the e-marketing mix. Top management at university libraries has paid very little attention to customer satisfaction, partly because there is an absence of research about the advantages of e-marketing for these types of libraries. This gap has strengthened the research framework for inquiry and analysis to solve this scholarly deficiency by creating a significant theoretical and literary gap in the published literature surrounding university libraries. These gaps serve as the main driving forces for our investigation. Concerning the electronic information services provided by university libraries in Jordan, the current study intends to investigate and assess the relationships between the e-marketing mix framework (4Ps) (EMM: e-product, e-pricing, e-place, and e-promotion) and customer satisfaction.

2.Literature review

Technological advancements, information media, and electronic communications have evolved the marketing landscape. E-marketing, also known as online marketing, web marketing, internet marketing, or digital marketing, is a modern form of marketing [25]. The description of e-marketing is a topic of debate, with some considering it a new approach and others viewing it as a complementary method to traditional approaches [26]. E-marketing had its inception in the early nineties, initially adopted by leading institutions and subsequently embraced by service organisations, information centres, and libraries through the establishment of websites to extend their reach to a broader audience [27]. Al-Zyoud et al. [25], amongst differing viewpoints on e-marketing, characterise it as a tactical method that uses technology, the internet, and associated applications in marketing to interact and successfully establish connections with a broad consumer base. Similarly, Alamro [28] defines e-marketing as using social media, mobile devices, the Internet, and other avenues to reach out to consumers. According to Alamro’s understanding, e-marketing now includes SMS, interactive bulletin boards, and other online advertising techniques in addition to the Internet. This interactive strategy uses email advertisements, sponsored Tweets, and search result ads to target certain client categories. Within the realm of university libraries, Ben Amira [27] defines e-marketing as the utilisation of digital channels and technologies to achieve marketing objectives, optimise the gains of information institutions, and consistently cater to the personal needs of beneficiaries. This interactive approach involves delivering information services through diverse channels, including software applications, websites, mobile text, email, social media, search engines, and display advertising. Neves [29] considers e-marketing a pivotal strategy for libraries, enhancing user attraction, disseminating information products, and equipping librarians with strategies for establishing a digital presence on social media. Sahu, Deb, and Mazumder [30] characterize e-marketing in libraries as the strategic process involving the planning, execution, and promotion of products and services. This is achieved through the utilization of information communication technologies with the primary goal of meeting the diverse needs of users. Moreover, Aloysius, Awa, and Aquaisua [31] assert the essentiality of e-marketing for Nigerian university libraries to overcome poor patronage. They emphasise the utilisation of information technology for marketing activities that align with organisational objectives, aiming to increase student satisfaction and loyalty. In the library context, the e-marketing mix is conceptualised as the strategic use of digital technologies, including email and Web 2.0 tools, to generate awareness about library materials and services [10].

2.1.E-marketing mix framework

E-marketing and e-marketing mix are essentially interchangeable concepts, with the distinction primarily lying in terminology. The term “e-marketing mix” pertains to the constituent elements, principles, or components integral to e-marketing strategies. According to Kotler and Keller [32], the e-marketing mix is characterised as a cohesive set of elements strategically combined to efficiently cater to the needs of recipients, ultimately ensuring their satisfaction. Likewise, Kotler and Armstrong [33] assert that the e-marketing mix is comprised of a combination of specialized elements carefully customized by an organization to elicit the desired response from target markets. The objective is to meet customer needs and achieve satisfaction. Jerome McCarthy, a notable marketing scholar and researcher, introduced the fundamental principles of the marketing mix, encompassing four core elements: product, price, place, and promotion (4Ps) [28]. Nevertheless, McCarthy’s 4Ps model has been criticised for its oversimplification and shortcomings in addressing intricate situations [34]. To overcome these limitations, Booms and Bitner [35] introduced three additional elements (people, process, and physical evidence), thereby expanding the marketing mix to a 7Ps model [36]. Subsequently, Philip Kotler and Kevin Lane Keller proposed a modification to the traditional 4Ps model, evolving it into an 8Ps model that incorporates product, price, place, promotion, people, process, programs, and performance [32]. Regarding the elements of the e-marketing mix, several trends have emerged. Originally designed to resemble the conventional marketing mix (4Ps), e-product, e-pricing, e-place, and e-promotion are now included in their development due to the convergence of technology, communication networks, and the internet. Another trend, which takes its cues from Jean J. Rechenmann, adds three more components to the e-marketing mix: people, processes, and tangible proof. This approach brings the mix into line with advancements in the e-services environment. Beyond the first four e-marketing mix components (4Ps), a third trend—proposed by McIntyre and Kalyanam—incorporates the 2Ps (personalisation and privacy), 3Ss (sales promotion, site, and security), and 2Cs (customer service and communities) [36].

According to Lamrous and Mehadjbi [37], the e-marketing mix in library settings is a purposeful combination of components library management uses to provide the right information product at the right cost and location. This method is purposefully created to both successfully meet the requirements of beneficiaries and achieve the library’s marketing goals. The 4Ps (e-product, e-price, e-place, and e-promotion) paradigm is widely used in business and is especially important for physical e-products. Nonetheless, a more thorough 7Ps approach is often used in service-oriented industries like libraries. The e-product, e-price, e-place, e-promotion, people, procedures, and tangible proof are all included in this expanded model. In service-oriented environments, the 7Ps paradigm is implemented to guarantee consumer satisfaction and meet their demands [38]. Electronic information services have specific characteristics, including providing effective means of accessing information, organising resources for easy retrieval, and ensuring the quality of the information offered. Incorporating the E-Marketing Mix, specifically the 4 Ps (e-product, e-price, e-place, and e-promotion), is a pioneering focus within the realm of university libraries in Jordan. In the current research, researchers have chosen to utilize this framework to assess its relationships with customer satisfaction. The study is particularly centred around electronic information services, covering aspects such as research assistance and educational programs to postgraduate students. These services are deemed pivotal in sustaining and relationship with customers’ satisfaction levels, aligning with findings from prior research conducted in different sectors. Comprehending the e-marketing mix framework is crucial for assessing the strategies and methodologies employed in promoting electronic goods and services. This section delves into the concepts and structure of the e-marketing mix framework, providing an understanding of its significance. The e-marketing mix contains numerous aspects, each performing a distinct function in promoting electronic goods and services. The following discourse offers a comprehensive examination of every element e-product, e-pricing, e-place, and e-promotion—and clarifies their respective roles in the marketing mix. Here is an in-depth review of every component:

1. E-Product

E-products play a crucial role in the e-marketing mix, serving as the foundation for decision-making in other elements. Studies by Loo and Leung [39] in Taiwan’s hotel industry and Abedian et al. [40] in Iran’s automotive parts market emphasise the examination of products as services, considering various factors. In the library context, e-products encompass a wide range, including services, information resources, programs, ideas, and information tailored to meet online library users’ needs [41]. Morsi [42] underscores the pivotal role of products (information sources) in driving changes within library services, facilitating active user engagement and adaptation to shifting needs. Gamit, Patel, and Patel [43] elaborate on electronic products in libraries, including e-books, e-journals, databases, and services like user training. E-products enhance the library’s capability to offer seamless remote access, contributing to sustainability and enhancing the user experience [44]. Fatmawati [45] stresses the role of marketing in distinguishing libraries’ unique e-resources and capturing user attention. This approach optimises the utilisation of electronic information resources, providing pleasant services and enhancing user satisfaction [46]. Continuous remote access offered by e-products eliminates the need for physical library visits, meeting research needs and enhancing satisfaction [41]. Fraser-Arnott [47] advocates for parliamentary libraries to share and upload documents on public websites, contributing to user satisfaction. Product updates ensure access to the latest information, anticipating user needs and enhancing satisfaction. Overall, e-products are integral to the library’s visibility, user satisfaction, and the optimisation of electronic information resources.

2. E-Pricing

In libraries, e-price pertains to the expenses associated with accessing online library resources. This encompasses subscription charges for specific databases, resources or, premium information services, along with fees for specific services and fines incurred for overdue books [43]. While many library services remain complimentary, certain libraries have introduced financial fees to address challenging economic conditions, escalating raw material costs, and heightened market competition [27]. These charges serve as a vital source of the library’s budget [42]. E-pricing empowers libraries to adeptly adjust the prices of their products or services in response to various factors, enabling them to align with evolving economic landscapes and achieve organisational objectives by introducing fees for information commodities or services [27]. According to Al-Habbari [41], e-pricing is crucial in user satisfaction, meeting their needs, and managing expectations. It facilitates the provision of a diverse range of resources, potentially attracting new beneficiaries from abroad. Optimal satisfaction is achieved by selecting electronic payment models that align with users’ preferences, and effective e-pricing strategies assist libraries in optimising budgets and efficiently allocating resources. Recognising that e-pricing decisions are dynamic and flexible, without a one-size-fits-all approach is imperative. The application of e-pricing allows it to adapt to the constantly evolving dynamics of the market and the myriad of factors related to pricing decisions [28].

3. E-Place

In the service sector, “place” refers to the location where services are made accessible to customers, involving the process of bringing services to them [48,49]. In a library context, “place” translates to access channels, encompassing the “when”, “where”, and “how” of service availability for users. The “when” denotes the timing of information provision, the “where” indicates service locations, and the “how” encompasses distribution methods, ensuring beneficiaries can access electronic resources and services [50]. This involves enhancing electronic platforms for easy navigation and ensuring resource availability across different sites and channels. E-place is crucial as many information services are not confined to the library at the time of production. It facilitates the dissemination of information services from the library’s production space to locations where users can access and utilize them, addressing service delivery’s temporal and spatial aspects [41]. E-place also bridges the temporal gap between production and beneficiary requests, ensuring that resources are provided when needed and accessible wherever required [42].

4. E-Promotion

Matura, Mbaiwa, and Mago [51] explored the role of promotion in introducing and reinforcing awareness of products and services provided by tourism companies in Zimbabwe, highlighting the efficacy of electronic promotion for success. Similarly, within a library context, e-promotion encompasses using technological channels to inform and engage existing and potential beneficiaries regarding the library’s products, information, and services [42]. This involves employing online advertising, email campaigns, social media marketing, search engines, instant messaging, and other interactive platforms facilitating communication between the library and users [52]. Promotion activities in libraries, as emphasised by Segun-Adeniran, Olawoyin, and Lawal-Solarin [53], aim at establishing accessible communication routes, such as emails and instant messaging, to allow users to express their information needs and receive assistance in selecting suitable resources and services. E-promotion assumes a vital role in reshaping user perceptions, enhancing their mental image of the library, and persuading them about the benefits and advantages offered [27]. Libraries need to employ modern electronic promotional strategies to inform users about the full range of services and resources, both print and digital, to meet their needs and overcome issues of user ignorance and temporal/spatial restrictions [6]. Adapting messages and announcements about library activities to user interests enhances interaction and awareness [50]. Effective e-promotion creates an open line of communication with users, leading to higher satisfaction levels [41]. Therefore, libraries should leverage electronic promotional strategies to optimise user engagement, educate users about available services, and ultimately enhance overall user satisfaction and library development.

2.2.Conceptualisation and the research hypothesis

- The Relationship between E-Product and Customer Satisfaction

According to this study’s operational definition, an “e-product” is any program, electronic information source, service that Jordanian university libraries provide to postgraduate students to meet their information demands. In this context, a review of relevant research is conducted. Egharevba [54] examined the state of libraries and highlighted the positive relationships between ICT-based resources at the Igbinedion University Library in Nigeria and increased user satisfaction. Moreover, Saidani and Sudiarditha [55] found a positive effect between consumer satisfaction and product quality in Jakarta, indicating that better-quality products result in more satisfied consumers. Furthermore, Razak, Nirwanto, and Triatmanto [56] demonstrated a favourable correlation between product quality and customer satisfaction. Hassan and Alassouli [57] concluded that e-product positively impacts client satisfaction. Tirtayasa et al. [58] showed that product innovation significantly effects competitive advantage and satisfaction in Indonesia. Almugari et al. [59] revealed that product information, quality, and e-service positively influence online shopping satisfaction in India. Cai and Chi [60] indicated product quality affects satisfaction in China. Sopyan et al. [61] showed the e-marketing mix positively affects e-customer satisfaction. Alqudah [62] found that e-marketing strategies, including product development, influence SMEs positively in Jordan. Afandi and Parhusip [63] emphasised the product’s relationship with customer satisfaction in Indonesia. Al-Habbari [41] demonstrated that e-products have positive relationships with customer satisfaction in Yemen. Kibebsii, Egwu, and Ntangti [64] found service and product quality to influence satisfaction in Cameroon. Al-Sukar and Alabboodi [65] revealed e-marketing mix impacts customer satisfaction in Jordan. Nasib [66] showed relationship between quality service and customer loyalty in Indonesia. Based on the foregoing discussion, it becomes apparent that e-products play a crucial role in shaping relationships with customer satisfaction. Consequently, the present research aims to explore whether comparable patterns exist within public university libraries in Jordan. This inquiry gives rise to hypothesis 1: “There is a significant and positive relationship between e-products and customer satisfaction regarding electronic information services (CSEIS).”

- The Relationship between E-Pricing and Customer Satisfaction

For the purposes of this study, “e-pricing” refers to the subscription fees or other charges that university libraries in Jordan levy on postgraduate students in exchange for timely access to information services. This section thoroughly evaluates earlier studies on the relationships between e-pricing and customer satisfaction in light of this operational definition. The study by Arizal, Listihana, and Nofrizal [67] in Pekanbaru-Riau, Indonesia, found a strong correlation between e-pricing and hotel patron satisfaction. Similarly, Saidani and Sudiarditha [55] found that pricing had a large and beneficial effect on customer satisfaction in Jakarta. According to research by Erdem and Tufan [68] on Turkish SMEs and Alqudah [62] on Jordanian SMEs, effective pricing strategies positively affect customer satisfaction. Do and Vu [38] underlined the importance of pricing in customer choices and satisfaction in the Vietnamese railway industry. Al-Sukar and Alabboodi’s [65] research in Jordan and Othman et al.’s [69] study in the Umrah Travelling Industry in Malaysia discovered statistically significant connections between the e-marketing mix (price) and consumer satisfaction. Nasib [66] used customer satisfaction at Binjai Hypermart in Indonesia to show how pricing has a favourable and substantial relationship with customer loyalty. According to research by Alamro [28] and Al-Zyoud et al. [25] conducted in Jordan, that e-pricing and customer satisfaction in the ICT industry have a significant positive relationship. At a coffee shop in Malang, Indonesia, Muhaimin and Yapanto [70] emphasised the influence of price on judgements about what to buy. Almugari et al. [59] discovered a strong positive correlation between pricing and consumer satisfaction in online purchasing in India. According to Elgarhy and Mohamed’s [71] research, traveller satisfaction with Egyptian travel agents is favourably influenced by pricing. Al-Zu’bi’s [72] study in Jordan emphasised the statistically significant effect of e-pricing on the competitiveness of tourist enterprises, notably during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pricing positively affected customers’ satisfaction with J&T Express Saentis Delivery Service in Indonesia, according to Afandi and Parhusip’s [63] findings. It’s crucial to remember that there are conflicting results as well. Mohammad’s [73] study in northeast Nigeria and Khumnualthong’s [74] research in Bangkok indicated a negative or no significant effect of pricing on customer satisfaction. The studies conducted in Palestine by Hassan and Alassouli [57] and Yemen by Al-Habbari [41] at private university libraries did not discover any statistically significant correlation between e-price and customer satisfaction. Similarly, a study conducted in South Korea by Basnet, Sherpa, and Del Cid [75] found that complicated payment and delivery procedures meant that e-price had no discernible impact on Coupang’s international students’ satisfaction. Suyono et al.’s study [76] in Pekanbaru, Indonesia, found that pricing had a significant and unfavourable effect on client satisfaction at a tax consulting firm. Similarly, Sabir et al.’s [77] research in the Pakistani setting showed a negative relationship between pricing and customer satisfaction in the restaurant business. Additionally, in Taiwan, Cheng et al.’s [78] analysis indicated that perceived pricing had a negative relationship with customer satisfaction within the fast-food business. Based on the foregoing discussion, it becomes apparent that e-pricing plays a crucial role in shaping relationships with customer satisfaction. Consequently, the present research aims to explore whether comparable patterns exist within public university libraries in Jordan. This inquiry gives rise to hypothesis 2: “There is a significant and positive relationship between e-pricing and customer satisfaction regarding electronic information services (CSEIS).”

- The Relationship between E-Place and Customer Satisfaction

In the scope of this study, “e-place” pertains to the distribution channels that facilitate access to information or product distribution from Jordanian university libraries to postgraduate students. This includes online platforms, social media, and mobile apps, intending to achieve cost-effective and timely access. Relevant literature has been explored to elucidate this concept. Al-Dwairi et al. [79] uncovered that online distribution channels positively impact consumer satisfaction and SME performance in Jordan. Muhaimin and Yapanto [70] showed the relationship between e-place and purchases in Indonesia. Othman et al. [69] found a significant effect between service marketing mix (place) and customer satisfaction in the Umrah Traveling Industry in Malaysia. Saidani and Sudiarditha [55] highlighted the positive effect of distribution on consumer satisfaction in Jakarta, emphasising the importance of smooth distribution for enhanced satisfaction. Al-Sukar and Alabboodi’s [65] study in Jordan showed a statistically significant impact between e-marketing mix (location) and customer satisfaction. Altay, Okumus, and Adıguzel Mercangoz [80] described positive impacts of e-marketing channels on customer satisfaction in Turkish on-demand grocery shopping services.This finding suggests that using electronic marketing channels positively enhances customer satisfaction within the context of on-demand grocery shopping services in Turkey. AL-Zu’bi [72] demonstrated a significant effect between e- place and the competitiveness of tourism firms in Jordan. This underscores the crucial role of the e-marketing mix in enhancing competitiveness and customer satisfaction, particularly during challenging times such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The study suggests that effective e-distribution strategies contribute to the overall competitiveness of tourism firms, showcasing the importance of adapting marketing approaches in response to dynamic situations. Alqudah’s [62] study in Jordan revealed a positive influence of all e-marketing mix strategies, including online distribution channels, on SME organisational performance. Afandi and Parhusip’s [63] results in Indonesia showed positive effects of online place channels on J&T Express Saentis Delivery Service users’ satisfaction. Contrastingly, Mohammad’s [73] study in Northeast Nigeria and Khumnualthong’s [74] research in Bangkok found negative or no significant effects of place on customer satisfaction. Arizal, Listihana, and Nofrizal [67] observed no significant effect of e-place on hotel customer satisfaction in Indonesia. This finding indicates that, in the specific context of the hotel industry in Indonesia, electronic distribution channels or online platforms may not have a substantial effect on customer satisfaction. It underscores the importance of considering industry-specific factors when assessing the effect of e-place on customer satisfaction. Hassan and Alassouli’s [57] study in Palestine found no statistically significant impact between e-distribution and client satisfaction. This suggests that, in the context of the study in Palestine, electronic distribution channels did not significantly impact client satisfaction. Similarly, Mishbakhudin and Aisyah [81] showed no significant relationship between e-place and consumer decisions in the Sharia marketplace Tokopedia Salam, Indonesia, during the Covid-19 Pandemic. This indicates that, during the specified period and within the given market, e-distribution channels did not have a significant relationship with consumer decisions. These findings highlight the need to consider specific market conditions and circumstances when evaluating the relationship between e-distribution or e-place and customer satisfaction. Al-Habbari [41] found no relationship between e-place and customer satisfaction in Yemeni private university libraries. This suggests that, in the context of Yemeni private university libraries, electronic distribution channels or online platforms may not have significantly relationship with customer satisfaction. Basnet, Sherpa, and Del Cid [75] indicated no significant impact of e-place on Coupang’s customer satisfaction among international students in South Korea. This implies that, within the specified international student market in South Korea, the electronic distribution channels used by Coupang did not have a statistically significant impact on customer satisfaction. Suyono et al. [76] demonstrated a significant negative effect of the location variable on customer satisfaction at a tax consultant office in Indonesia. This indicates that the physical location or distribution aspect negatively influenced customer satisfaction in the context of the tax consultant office. In the Malaysian tourism sector, Kadhim et al. [82] revealed that inconvenient locations result in customer dissatisfaction, negatively affecting the organisation. This underscores the importance of convenient locations in the tourism sector to enhance customer satisfaction. Building on the comprehensive review of various studies, it is evident that the relationships between e-place and customer satisfaction vary across different contexts and industries. Given this understanding, the researcher aims to investigate the specific relationship between e-place and customer satisfaction within the context of e-information services in public university libraries in Jordan. This leads to the formulation of the hypothesis 3: ``There is a significant and positive relationship between e-place and customer satisfaction regarding electronic information services (CSEIS).”

- The Relationship between E-Promotion and Customer Satisfaction

Within the framework of this study, “e-promotion” refers to the electronic marketing strategies Jordanian university libraries use to advertise their services to postgraduate students and other interested parties. This is an overview of earlier research on the relationships between e-promotion and customer satisfaction: In Pekanbaru-Riau, Indonesia, Arizal, Listihana, and Nofrizal [67] showed that e-promotion had a favourable effect on hotel patron satisfaction. This shows that electronic promotional activities positively effect customer satisfaction in the hotel business in the given setting and context. Successful e-promotional strategies have a beneficial effect on customer satisfaction at pharmaceutical enterprises in Jordan, according to research by Al-Shbiel and Siam [83]. Saidani and Sudiarditha [55] in Indonesia and Ben Shanina and Mattai [84] in Algerian Banks both determined that e-promotion has a favourable and substantial relationship with client satisfaction. According to Al-Sukar and Alabboodi’s [65] research in Jordan and Othman et al.’s [69] study in Malaysia, there are statistically significant correlations between customer satisfaction and the E-marketing mix (promotion). According to Do and Vu’s [38] research in the railway sector in Vietnam, promotional campaigns are highly and significantly related to consumer satisfaction with railway transit. In an Indonesian coffee business, Muhaimin and Yapanto [70] demonstrated a statistically significant of e-promotion on customer satisfaction and purchase choices. This shows that, in an Indonesian coffee shop setting, electronic advertising activities have a favourable effect on both customer satisfaction and the consumers’ decision-making process. E-promotion, customer satisfaction, and competitive advantage in the ICT industry in Jordan are significantly positive relationships, this suggests that successful e-marketing techniques improve customer satisfaction and boost an organization’s ability to compete in the Jordanian ICT market. During crises like the COVID-19 Pandemic, e-promotion substantially relationship between competitiveness, competitive advantage, and customer happiness, as established by Alamro [28]. As shown by AL-Zu’bi’s [72] research on tourist enterprises in Jordan. Suyono et al.’s study [76] from Indonesia revealed that e-promotion significantly improved client satisfaction at a tax consulting firm. Sopyan et al.’s [61] research conducted in Indonesia on e-commerce found that the e-marketing mix, or sales promotion, had a significant beneficial effect on the satisfaction of consumers of online shopping transaction services. According to Alqudah’s research conducted in Jordan [62], e-promotion and all other e-marketing strategies significantly influence organisational performance indicators. Al-Habbari [41] found that e-promotion significantly improves consumer satisfaction with information services in Yemeni university libraries. According to Afandi and Parhusip’s [63] findings in Indonesia, e-promotion positively affected consumers’ contentment with the J&T Express Saentis Delivery Service. There are conflicting results, however. Hassan and Alassouli’s [57] research in Palestine and Muhammad’s [73] study in Northeast Nigeria demonstrated a statistically significant detrimental effect of e-promotion on customer satisfaction. According to research by Sanny et al. [85], e-promotion does not affect customer satisfaction in online SMEs on Instagram. International students’ satisfaction with Coupang’s customer service was not significantly impacted by e-promotion, according to research conducted in South Korea by Basnet, Sherpa, and Del Cid [75]. Building on these analyses of several research, e-promotion plays a crucial role in shaping relationships with customer satisfaction in various businesses and scenarios. With this knowledge in mind, the researcher wants to learn more about the relationships between e-promotion on patron satisfaction in the context of electronic information services offered by Jordanian public university libraries. Consequently, the formulation of hypothesis 4: ``There is a significant and positive relationship between e-promotion and customer satisfaction regarding electronic information services (CSEIS).”

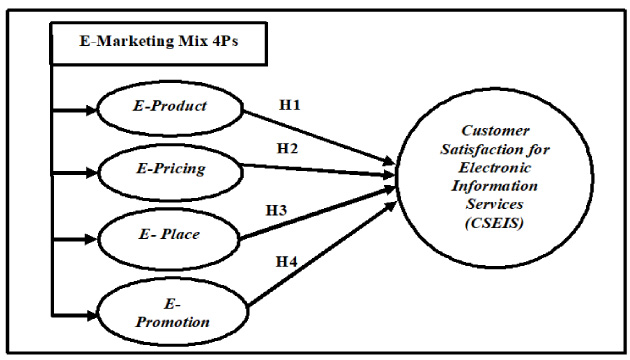

It is worth noting that very few studies attempted to verify the relationship between the e-marketing mix and customer satisfaction in the library sector. However, there are many in other sectors. Moreover, no study was found in the context of Jordanian university libraries and customer satisfaction with electronic information services. It can be said that the e-marketing mix is hardly explored as a multidimensional construct. Hence, the present study proposes a framework (shown in Fig. 1) based on four dimensions of customer satisfaction.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

3.Materials and methods

The present study offers valuable insight into the relationship between the e-marketing mix (4Ps) and customer satisfaction with electronic information services provided by public university libraries in Jordan. An extensive description of the research method is covered in depth in the following section.

3.1.Instrumentation

The survey was conducted using a questionnaire method to capture all the research’s independent and dependent variables (exogenous and endogenous). The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section gathered demographic information, while the second section analysed the relationship between different constructs per the conceptual model (refer to Fig. 1). These constructs, which total 46 items, were modified from earlier research and verified through a pilot study. A 7-point Likert scale was used to measure each item on the scale. The e-product (EPRD) was assessed using 10 items taken from Esan and Adeyemi [86] after adjustments. E-pricing (EPRI), with 7 elements, was derived from Otuu and Unegbu [87], Alamro [28], and Esan and Adeyemi [86] after incorporating adjustments. Nine elements that were modified and adapted from Esan and Adeyemi [86] and Nabila and Erlianti [50] form the basis of E-place (EPIC). Ten components serve as the foundation for e-promotion (EPROM), each of which was modified from Otuu and Unegbu [87], Alamro [28], and Nabila and Erlianti [50]. Customer satisfaction, the dependent variable, was modified from Haftu [88] and Alam and Mezbah-ul-Islam [89] and consists of ten components.

3.2.Population

This study focuses on postgraduate students within Jordanian public universities as its target population. The total postgraduate student population at these universities, comprising 21,394 individuals in the academic year 2022–2023, serves as the denominator for distributing questionnaires. This figure is sourced from the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MoHE) and is categorized by gender, academic level, academic discipline, and age group in Table 1. The ministry’s records indicate a breakdown of 21,394 postgraduate students across the eight public universities in the country, with a specific count for males and females. Furthermore, the data delineate the distribution of students pursuing Ph.D. and Master’s degrees, categorized by academic disciplines such as Humanity faculties, Scientific faculties, and medical faculties. Age-wise, the postgraduate student population is stratified into groups: above <30 years old, 31–40 years, 41–50 years, and those above 51 years old, each with their corresponding student counts.

These categories of respondents were specifically chosen from the postgraduate student community to constitute the research population. This selection was made due to their predominant role as the primary users and beneficiaries of the library’s information services, surpassing undergraduate students and other user categories. The preference for postgraduate students is rooted in their intensive engagement in rigorous research activities and academic endeavors. Furthermore, the library offers a diverse array of electronic information services tailored specifically to postgraduate students, a distinction that sets them apart from other user groups. Notably, a dedicated electronic entry portal named “Ezlibrary” exclusively caters to the unique needs of postgraduate students, underscoring the library’s commitment to meeting their specialized requirements. Equally, these libraries were preferred based on all being accredited by MoHE. The MoHE accreditation of all these libraries made them the preferred choice. These libraries also offer a wide range of electronic information services to a large number of users and beneficiaries. Compared to other libraries. In a similar vein, the chosen universities also enjoy numerous postgraduate students.

3.3.Sample size determination

Given the challenge posed by the extensive size of the population, the researchers have opted for a sampling technique. This method relies on a formula established by Krejcie and Morgan (1970) [90] to ascertain a suitable sample size for empirical studies, such as surveys. This strategic use of sampling allows the researchers to draw meaningful conclusions and insights from a representative subset of the population, ensuring the feasibility and efficiency of the study within practical constraints. In reference to Krejcie and Morgan’s sampling table, it is noted that the specified target population for this study is not explicitly covered, as it falls within the range of 20,000 to 30,000 individuals suggested by Krejcie and Morgan. Consequently, the population margin for this research is considered. Utilizing the formula recommended by Krejcie and Morgan, the sample size is derived based on the following criteria: for a population (N) of 20,000, the required sample (S) is 377, and for a population (N) of 30,000, the recommended sample (S) is 379. Given that the current study’s population is N = 21, 394, the sample size is determined as the average of these figures: ((377 + 379)/2) = 378. In this context, a minimum sample size of 378 respondents is deemed sufficient to yield meaningful results [91].

Limitations of this sampling model include the potential for self-selection bias, where individuals with a particular interest in the survey topic are more likely to respond. Additionally, the use of voluntary sampling introduces the risk of underrepresentation or overrepresentation of certain groups, affecting the generalizability of the findings. To mitigate non-response bias, the researchers collected a number larger than the minimum sample size recommended by Krejcie and Morgan, to achieve meaningful results, avoid unjustified sensitivity in statistical tests that comply with the established standards in this field, and ensure obtain the number of analytical responses after excluding non-analysable responses. Furthermore, strategies such as follow-up reminders 3 weeks after the link was distributed were used to encourage a reasonable response rate from the five categories of the population according to the ministry data. It’s worth noting that the literature suggests that a sample size of 500 is likely to be very good, and 700 to 1000 samples are considered excellent [92].

3.4.Sampling procedure and data collection

The online survey was conducted with a sample of postgraduate student respondents, and answers were gathered using Google Forms. From June to August of 2023, a sample of respondents was chosen from each of the eight public universities in Jordan. Voluntary sampling is a non-probability sampling approach that was used in this study. A Google Forms-created internet questionnaire was used for the data-gathering procedure. The Department of Electronic Services for Jordanian students at the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MoHE) first received the questionnaire link. The ministry verified the questionnaire’s substance, and then formal approval to distribute it was given. After receiving the link, the Centre for Postgraduate Studies (CPS) at public universities sent the questionnaire to each college’s Postgraduate Office (PG) and all postgraduate student respondents by email. An email invitation to participate in the survey was sent to postgraduate students and a link to view the questionnaire. The data collection process resulted in responses from 800 postgraduate students across eight public universities in Jordan. The response rate is calculated by dividing the number of responses received (800) by the total population that was surveyed (21,394) and then multiplying by 100 to express it as a percentage. Therefore, the response rate for this survey is approximately 3.61% of the total study population. To ensure the quality of the sample, the researchers conducted two preliminary stages: checking for missing values (none were found) and cleaning the data by removing outliers. These steps led to a conclusive sample size of 792 postgraduate student respondents. The response rate is 99% for the total collected responses, representing a diverse group from the eight Jordanian public universities. This diverse group aligns with the demographic characteristics outlined in Table 1, providing an overview of the responses gathered and their concordance with the actual postgraduate student population across the selected institutions.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics of the population and respondent

| Population | Respondents | ||||

| Categories | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | Female | 13245 | 61.9% | 453 | 57.2% |

| Male | 8149 | 38.1% | 339 | 42.8% | |

| Level of study | Ph.D. | 3867 | 18.1% | 213 | 26.9% |

| Master’s | 17527 | 81.9% | 579 | 73.1% | |

| Specialisation | Humanity faculties | 8841 | 41.3% | 318 | 40.2% |

| Scientific faculties | 7590 | 35.5% | 246 | 31.1% | |

| Medical faculties | 4963 | 23.2% | 228 | 28.7% | |

| University | Mutah University | 2487 | 11.6% | 108 | 13.6% |

| The Hashemite University | 1382 | 6.5% | 93 | 11.7% | |

| Al-Balqa’ Applied University | 830 | 3.9% | 83 | 10.5% | |

| Yarmouk University | 4864 | 22.7% | 108 | 13.6% | |

| Al-Hussein Bin Talal University | 678 | 3.2% | 77 | 9.7% | |

| Al al-Bayt University | 2235 | 10.4% | 99 | 12.5% | |

| The University of Jordan | 6965 | 32.6% | 128 | 16.2% | |

| Jordan University of Science and Technology | 1953 | 9.1% | 96 | 12.2% | |

| Age | <30 | 6148 | 28.7% | 260 | 32.8% |

| 31–40 | 4702 | 22, 0% | 232 | 29.3% | |

| 41–50 | 6896 | 32.2% | 234 | 29.5% | |

| >51 | 3648 | 17.1% | 66 | 8.4% | |

| Total | 21,394 | 100% | 792 | 100% | |

Overall, the demographic properties in Table 1 indicate the gender, level of study, specialization, university, and age of student respondents compared to the population from which they are drawn. Females predominate in both instances (57.2% and 61.9%). There is a preponderance of master’s students (73.1% and 81.9%). Areas of specialization are nearly equivalent with Humanity faculties the largest (40.2% and 41.3%). University representation is very similar with only The University of Jordan being significantly underrepresented (16.2% and 32.6%). Student age is a little younger in the sample with those under 30 the largest (32.8%) compared to a slightly older population overall, with those aged 41–50 predominating (32.2%). Thus, it can be said that the sample demographics approximate the population, particularly within Jordan’s public university libraries, supporting the generalizability of the research findings.

4.Results

4.1.Measurement model

The data analysis was performed using Smart PLS-SEM (Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling) Version 3.2. The conceptual model was subjected to a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 subsamples to test its validity. Table 2 presents detailed information on the items, including Indicator Reliability (Outer Loadings) (OL), Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct in the study. To meet the criterion of a positive factor loading larger than 0.60 [91], eight items (EPRD9, EPRD10, EPRI7, EPLC2, EPLC3, EPRM4, EPRM5, and EPRM10) were excluded from the overall model. The remaining items, surpassing the 0.60 threshold, were retained, as outlined in Table 2. All retained items demonstrated satisfactory indicator reliability, with values ranging from 0.660 to 0.966. This underscores the reliability of the measurements used in the study. The assessment of internal consistency was conducted by examining the values of Cronbach’s alpha, and it was determined that all constructs achieved values higher than 0.70. This outcome aligns with the standard level of reliability, ensuring the robustness of the measurements used in the study. The disclosure of Cronbach’s alpha values for all constructs was considered appropriate [91]. Furthermore, all constructs exhibited composite reliability ratings exceeding 0.70, indicating their adherence to the standard level of reliability. The suitability of composite reliability ratings for consideration and disclosure is evident from Table 2 [91]. In the context of this study, Table 2 additionally provides the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for all reflective constructs. Importantly, all AVE values exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.50 as suggested by [91] and [93]. This indicates that convergent validity is established for all constructs in the study, as supported by AVE values surpassing the recommended threshold.

Table 2

Summary of measurement model

| Construct | Items | OL | 𝛼 | CR | AVE | |

| E-Product (EPRD) | 1 | My library is committed to offering e-information sources that align with my needs. | 0.722 | 0.721 | 0.940 | 0.663 |

| 2 | The library consistently supplies users with e-products across various fields of knowledge. | 0.785 | ||||

| 3 | Authoritative e-informatics products are provided by my library. | 0.849 | ||||

| 4 | My library ensures the availability of up-to-date e-informatics products. | 0.846 | ||||

| 5 | There is a diversity of e-information services (e-journals, current awareness service, online searching service, etc.) offered by my library. | 0.841 | ||||

| 6 | Users are regularly informed about the available e-services provided by the library. | 0.855 | ||||

| 7 | Electronic marketing of library resources and services has heightened my awareness and motivation to use them. | 0.787 | ||||

| 8 | My library provides information sources via its website around the clock, seven days a week. | 0.818 | ||||

| E-Pricing (EPRI) | 1 | The membership fee for external postgraduate students at my library is reasonably priced. | 0.908 | 0.934 | 0.948 | 0.754 |

| 2 | My library ensures that e-services are promptly made accessible to users. | 0.864 | ||||

| 3 | Information services at my library are provided free of charge to all members of the university community. | 0.906 | ||||

| 4 | My library follows a policy of processing service fees through various electronic media, such as bank credit cards. | 0.865 | ||||

| 5 | The costs (subscription fees) of services provided by my library are determined and communicated through its website. | 0.865 | ||||

| 6 | My library imposes a reasonable fee for photocopying search results in e-databases. | 0.795 | ||||

Table 2 (Continued).

| Construct | Items | OL | 𝛼 | CR | AVE | |

| E-Place (EPLC) | 1 | My library permits me to download information products from its website. | 0.875 | 0.950 | 0.959 | 0.770 |

| 4 | The library offers links for contacting and communicating with staff through its website. | 0.865 | ||||

| 5 | The library sends a list of newly arrived books to users via email. | 0.860 | ||||

| 6 | Users have access to a list of newly arrived books through the library’s website. | 0.907 | ||||

| 7 | E-services are accessible to users through the Online Public Access Catalog (OPAC). | 0.881 | ||||

| 8 | Users can access e-services through phone calls or WhatsApp chat. | 0.885 | ||||

| 9 | My library offers open access to numerous electronic resources. | 0.870 | ||||

| E-Promotion(EPRM) | 1 | My library employs a website to promote accessible e-databases. | 0.924 | 0.974 | 0.978 | 0.864 |

| 2 | SMS services are utilized for the promotion of e-information services. | 0.940 | ||||

| 3 | Email lists are employed to promote e-information services. | 0.895 | ||||

| 6 | The library includes links to virtual book fairs on its website. | 0.898 | ||||

| 7 | The advertisements on the website are consistently refreshed. | 0.953 | ||||

| 8 | My library leverages social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and Telegram to share interactive announcements about its latest activities. | 0.966 | ||||

| 9 | Flyers and blogs are utilized for the promotion of e-information services. | 0.928 | ||||

| Customer Satisfaction with Electronic Information Services (CSEIS) | 1 | The e-information services provided by the library meet my satisfaction. | 0.818 | 0.917 | 0.931 | 0.576 |

| 2 | The library’s e-services consistently fulfill all my information requirements for scientific research purposes. | 0.800 | ||||

| 3 | The library demonstrates a commitment to offering contemporary services in comparison to other libraries. | 0.740 | ||||

| 4 | Library resources are distinguished by their modernity. | 0.664 | ||||

| 5 | The library promptly delivers its services to users. | 0.653 | ||||

| 6 | I am content with the library staff’s ability to deliver the promised e-services. | 0.764 | ||||

| 7 | I express an intention to utilize the library in the future. | 0.731 | ||||

| 8 | I am inclined to recommend the library’s services to others. | 0.812 | ||||

| 9 | As a university library, I perceive the quality of e-services provided as excellent and effective. | 0.821 | ||||

| 10 | The library possesses satisfactory and ample resources. | 0.768 | ||||

Table 3 illustrates the discriminant validity as determined by the Fornell-Larcker criterion. Notably, all values for each construct are greater than the correlations with their respective constructs. This observation indicates that the variance of each construct surpasses the measurement error variance, aligning with the recommendation by Hair et al. [91]. Hence, according to the Fornell-Lacker criterion presented in Table 3, the measurement model demonstrates discriminant validity, confirming that each construct is distinct from others in the model.

Table 3

Descriptive statistics: Fornell-Larcker criterion

| CSEIS | EPLC | EPRI | EPRD | EPRM | |

| CSEIS | 0.759 | ||||

| EPLC | 0.724 | 0.878 | |||

| EPRI | 0.589 | 0.719 | 0.868 | ||

| EPRD | 0.943 | 0.767 | 0.560 | 0.814 | |

| EPRM | 0.707 | 0.464 | 0.384 | 0.575 | 0.929 |

The Fornell-Larcker Criterion results indicate strong discriminant validity, as the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeds its correlations with other constructs. However, the exceptionally high correlation of EPRD (E-Product) with itself (0.943) and CSEIS (0.759) raises concerns about potential multicollinearity or shared variance between these constructs. The exceptionally high correlation of EPRD (E-Product) with itself (0.943) and CSEIS (0.759) may suggest a potential overlap in the underlying constructs or shared variance, possibly indicating issues with specific items within these scales. Future studies could benefit from a more granular examination of the items comprising EPRD and CSEIS to identify and refine those contributing to the high correlation, thereby enhancing the precision and reliability of the measurement instruments.

4.2.Structural model

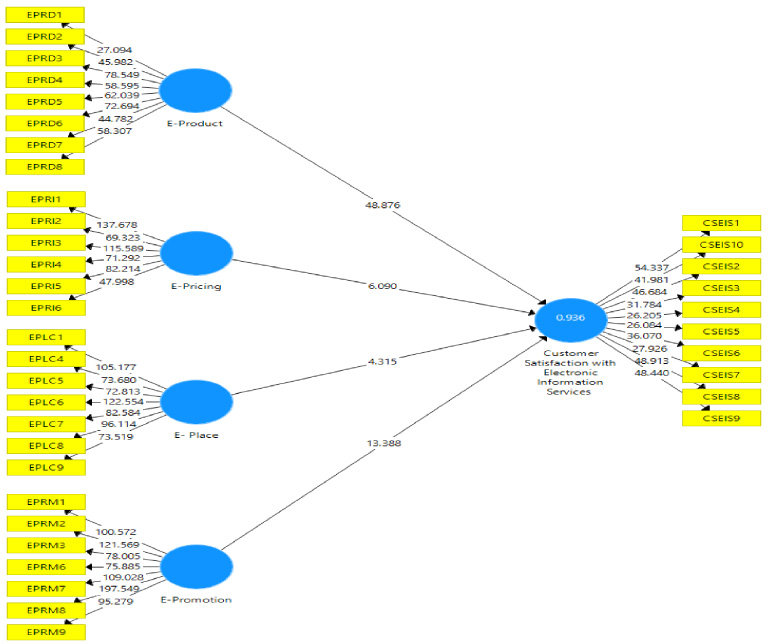

Testing hypotheses in line with the research objectives is part of the structural model assessment process, as shown in Fig. 2. Based on the established research framework, four research hypotheses were produced for this study. The structural model evaluation, which employs the approach described by Ramayah et al. [93], seeks to pinpoint important and influential trajectories that support the proposed assumptions. Throughout the review, the model’s structural elements are thoroughly discussed. Three essential criteria need to be met to evaluate a structural model: the model’s predictive relevance (Q2 value), relationship magnitude (f2 value), and coefficient of determination (R2 value).

Fig. 2.

Structural model (inner model).

Table 4 presents results that support Hypothesis 1, confirming a statistically significant relationship between EPRD and CSEIS (

Table 4

Results of structural equation analysis

| Path | Standard deviation | Beta (𝛽) | Tstatistics | P values | Result | |

| H1 | EPRD → CSEIS | 0.02 | 0.823 | 48.88 | p ≤ 0.01 | Significant (positive relationship) |

| H2 | EPRI → CSEIS | 0.02 | 0.100 | 6.09 | p ≤ 0.01 | Significant (positive relationship) |

| H3 | EPLC → CSEIS | 0.02 | −0.088 | 4.32 | p ≤ 0.01 | Significant (negative relationship) |

| H4 | EPRM → CSEIS | 0.02 | 0.232 | 13.39 | p ≤ 0.01 | Significant (positive relationship) |

When the dependent variable of the model is the expected result, the coefficient of determination (R2) is a measure used to evaluate how well a statistical model can predict an event [94]. Moreover, R2 sheds light on the relationship between the independent variable (exogenous) and the dependent (endogenous) construct by explaining the percentage of the dependent variable’s variation that can be ascribed to the independent variable. The R2 values for the model were 0.936. The results in Fig. 2 thus illustrate that the present model explained 0.936 of the variances in the utilization of CSEIS. This indicates a high level of explanatory power for the model in understanding and predicting student respondents’ satisfaction with electronic information services in Jordanian university libraries.

5.Discussion

The first hypothesis posits that student respondents are cognizant of the significant relationship between e-products and CSEIS. This assertion is in harmony with the findings of several studies conducted by Egharevba [54], Saidani and Sudiarditha [55], Hassan and Alassouli [57], Al-Sukar and Alabboodi [65], and Tirtayasa et al. [58]. These studies collectively assert that e-products offer manifold advantages, augmenting satisfaction among student respondents through remote access to journals, e-books, databases, and other resources. This accessibility, facilitated by an internet connection, proves valuable for student respondents unable to visit the library during regular hours. Furthermore, e-products enable libraries to provide a diverse range of resources without spatial constraints, addressing the varied information needs of users. Equipped with search and discovery tools, e-products simplify full-text searches, enhancing the overall customer experience. Remote access also fosters inclusivity, particularly benefiting library patrons with mobility restrictions, such as patients and individuals with special needs. This indirectly contributes to heightened student respondent satisfaction. Additionally, incorporating interactive multimedia content in some e-products offers an engaging experience for tech-savvy users, leading to increased satisfaction levels for them. The immediacy of accessing digital copies eliminates wait times associated with physical resource handling, further enhancing the user experience. Moreover, the ease of updating e-products ensures maintaining current and relevant collections and adapting to the evolving information landscape. This, in turn, enhances library services’ value and improves customer satisfaction and retention.

The findings of the second hypothesis indicate that e-pricing does indeed have a statistically significant and direct relationship with CSEIS. This implies that the pricing strategies employed by libraries play a crucial role in the relationship with student respondents’ satisfaction. The results emphasise the importance of further exploration and potential adjustments in e-pricing strategies to better align with user expectations and enhance overall satisfaction with electronic information services. Consequently, this research offers insights to assist libraries in making informed decisions regarding e-pricing models and strategies for enhancing customer satisfaction. This aligns with the findings of Arizal, Listihana, and Nofrizal’s [67] study, Saidani and Sudiarditha [55], Erdem and Tufan [68], Alqudah [62], Do and Vu [38], Al-Sukar and Alabboodi’s [65]. However, it’s important to note that there are also contrasting findings, like Mohammad [73], Khumnualthong [74], Hassan and Alassouli [57], Al-Habbari [41], and Basnet, Sherpa, and Del Cid’s study [75].

The third hypothesis results indicated a significant but negative relationship between e-place and CSEIS, which shows that postgraduate student respondents are dissatisfied with their experiences in the e-place and have encountered problems like slow loading times, usability issues of the library websites outside the university campus, poor user service, security concerns, difficulty finding information, and delayed responses to inquiries. Jordanian university libraries should investigate ways to improve the overall experience on digital platforms and identify and resolve website issues to improve students’ interactions with the e-place. The study emphasises the need for further analysis to identify specific components within the e-place that led to the dissatisfaction reported by postgraduate student respondents. It suggests that improvements in service locations and addressing specific issues could enhance customer satisfaction. This research finding aligns with studies by Suyono et al. [76], Mohammad [73], Mishbakhudin and Aisyah [81], Arizal, Listihana, and Nofrizal [67], Hassan and Alassouli [57], Al-Habbari [41], as well as Basnet, Sherpa, and Del Cid [75].

The obtained outcomes confirm the validity of the fourth hypothesis, highlighting the positive relationship between e-promotion and student respondents’ satisfaction. It is imperative to recognise that this favourable relationship is intricately linked to the credibility and precision of e-advertising, successful e-promotion enables direct engagement with student respondents at strategic intervals through customised marketing initiatives aligned with their research, scientific, and educational requirements. Monitoring students’ interactions with these campaigns and making necessary adjustments enhances the overall student respondents’ experience. Jordanian university libraries demonstrate a reliance on measurable data analytics to comprehend users’ behaviour and preferences, particularly in an era dominated by extensive online shopping and digital experiences. The heightened awareness among student respondents regarding the significance of promotional activities and strategies has likely escalated post-COVID-19, prompting teaching, learning, research, and innovation endeavours. Sustaining customer loyalty to service providers can be achieved through effective marketing endeavours. Consequently, continuous monitoring and optimisation of e-promotion initiatives by Jordanian university libraries are indispensable for attaining desired outcomes and meeting customer expectations. The findings of this study align with many previous research efforts, consistently supporting the positive relationships between e-promotion and customer satisfaction. Examples include studies by Arizal, Listihana, and Nofrizal [67], Al-Shbiel and Siam [83], Saidani and Sudiarditha [55], Al-Sukar and Alabboodi [65], Muhaimin and Yapanto [70], Suyono et al. [76], Alqudah [62], and Al-Habbari [41]. These factors collectively contribute to enhancing student respondents’ satisfaction with e-information services, validating the utilization of the e-marketing mix framework in this study.

6.Limitations of the research

While the research has contributed valuable insights into the subject matter, it is also subject to certain limitations that can be categorized into result-related and methodological constraints. Firstly, the focus exclusively on Jordanian public university libraries restricts the generalizability of the research outcomes. Extending the findings to other library types, particularly private university libraries, may not yield comparable results. To enhance external validity, future research should aim for a more diverse sample, encompassing various library categories. Secondly, the data collection process is confined to postgraduate students in public universities. Expanding the sample to include the entire population could address potential non-response bias inherent in this sampling model, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of electronic information service satisfaction. Thirdly, certain components of the E-marketing Mix (EMM), such as personalization, privacy, security, community, and performance, which may influence customer satisfaction, are not fully explored in this research. Future studies could consider incorporating these elements for a more nuanced analysis. Additionally, the dynamic nature of EMM practices and rapid technological advancements pose a challenge in accurately predicting future trends or shifts based on the current findings.

From a methodological standpoint, the formulation and collection of “independent” vs. “dependent” variables introduce challenges in avoiding a methodology-driven correlation between the two sets of variables. Future research might benefit from employing external measures of satisfaction, such as the extent of service use and real-time feedback on service utilization in the library system. Furthermore, the observed high correlation between EPRD and CSEIS indicates potential overlap and lack of independence, suggesting that revising individual items within this scale or adopting external methods for collecting satisfaction data could be explored in future studies to enhance measurement precision.

7.Conclusion

The current study addresses a notable gap in the literature by investigating the relationship between the e-marketing mix (4 Ps) and student respondents’ satisfaction with e-information services, specifically within the context of public university libraries in Jordan. While past research has explored the e-marketing mix in various sectors, there has been limited attention to its application in the domain of university libraries. This study highlights the rapid growth of e-information services in university libraries in Jordan, underscoring their crucial role in addressing the diverse needs of faculty, researchers, and postgraduate students. While advancements have been made, lingering concerns revolve around user satisfaction and the challenge of keeping abreast of modern technology. The study significantly contributes to understanding the factors influencing customer satisfaction. It highlights the paramount role of the e-marketing mix framework, emphasising its relationship with postgraduate students’ respondents’ satisfaction with e-information services. Indeed, the research emphasizes the crucial role of services in relation to user behaviors and satisfaction, recognising their significance in shaping the overall user experience. Implications of the research extend to decision-makers within public university libraries and similar institutions, this research provides actionable insights into formulating e-marketing strategies and plans aimed at improving customer satisfaction. For librarians and information specialists, this research provides insights to foster a deeper understanding of the e-marketing culture and the phenomenon of technology turbulence within library environments. For Postgraduate students, this research provides insights to enhance their awareness of the pivotal role of electronic information services in their academic and research pursuits.

The research has certain limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the primary emphasis on Jordanian public university libraries narrows the generalizability of the research results. Generalizing the findings to other libraries, especially private university libraries, might not yield similar outcomes. Future research should aim for a more diverse sample, encompassing various types of libraries, to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the data collection is limited to that of postgraduate students in public universities only. For more research, the sample could be expanded to the whole population to address the issue of non-response bias in this type of sampling model and its limitations. Third, other elements of EMM like personalization, privacy, security, community, and performance influencing customer satisfaction are not fully accounted for in the research. Finally, the dynamic nature of EMM practices and rapid technological advances may limit the findings’ ability to predict future trends or shifts accurately. Future research could broaden the scope by using external measures of satisfaction e.g., extent of service use and real-time feedback on service use. Additionally, exploring other variables for EMM, such as personalization, privacy, security, community, and performance could enhance understanding.

References

[1] | F. Pascucci, E. Savelli and G. Gistri, How digital technologies reshape marketing: Evidence from a qualitative investigation, Italian Journal of Marketing(1) ((2023) ), 27–58. doi:10.1007/s43039-023-00063-6. |

[2] | S. Alsaudi, The Status Que of Using Electronic Publishing Tools to Marketing Information Services in Jordanian University Libraries in the Central Region from their Employees Perspectives (Unpublished Master’s Thesis), University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan, 2022. |

[3] | E. Bruce, Z. Shurong, D. Ying, M. Yaqi, J. Amoah and S.B. Egala, The effect of digital marketing adoption on SMEs sustainable growth: Empirical evidence from Ghana, Sustainability 15: (6) ((2023) ), 4760. doi:10.3390/su15064760. |

[4] | D.L. Hoffman, C.P. Moreau, S. Stremersch and M. Wedel, The rise of new technologies in marketing: A framework and outlook, Journal of Marketing 86: (1) ((2022) ), 1–6. doi:10.1177/00222429211061636. |

[5] | D. Joshua and D. Michael, Effective marketing techniques for promoting library services and resources in Academic libraries, Library Philosophy and Practice, (e-journal) 1: : ((2020) ), 1–30, https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4091. |

[6] | B. Mandrekar and M.C. Rodrigues, Marketing of library and information products and services during covid-19 pandemic: A study, Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) ((2020) ), 4514, Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4514. |

[7] | A.F. Gaber, H.A. Abuelmagd and A.I. Ahmed, The impact of e-marketing on achieving sustainable competitive advantage among libraries: A case study on Ithraa public library in Dammam-KSA, Ilkogretim Online 20: (3) ((2021) ), 2647–2668, URI: http://hdl.handle.net/10760/40726. |

[8] | D. Arbani, Digital marketing and user satisfaction in library 2.0. in: Proceeding of the 8th International Conference on Management and Muamalah (ICoMM). International Islamic University College Selangor, Malaysia, (2020) , pp. 021–041.. |

[9] | D.A. Arbani and C.Z. Abdullah, Digital marketing and user satisfaction in library 2.0: A concept and research framework, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 7: (12) ((2017) ), 515–522. doi:10.6007/ijarbss/v7-i12/3632. |

[10] | J.O. Ubogu, E-marketing of library resources and services. Library of progress-library science, Information Technology & Computer 41: (1) ((2021) ), 144–154. doi:10.5958/2320-317X.2021.00016.7. |

[11] | M. Al-Khalidi, Marketing information services in university libraries central library at Al-Qadisiya university model, Journal of Al-Qadisiya in Arts and Educational Sciences 19: (3) ((2019) ), 307–331. |

[12] | H. Alawi, The role of social networks in the development and marketing of information services in Algerian public reading libraries during the corona crisis, The Journal of the Arab Center for Research and Studies in Library and Information Sciences 8: (15) ((2021) ), 3–20. doi:10.33951/1543-008-015-002. |

[13] | E. Bouaziz, The reality of e-marketing of information in university libraries: A field study at the central library Ahmed Erwa of Prince Abdul Qader Islamic University in Constantine (Unpublished Master’s Thesis), University of Guelma, Algeria, 2019. |

[14] | N. Mohapatra, E-marketing: The library perspective, International Journal of Library Science and Information Management (IJLSIM) 3: (1) ((2017) ), 34–43, URI: http://hdl.handle.net/10760/40749. |

[15] | Y. Shawabkeh and E. Sultan, Job satisfaction of library staff at public Jordanian university libraries and its relationship to the quality of information services as perceived by them, Dirasat: Educational Sciences 2: (46) ((2019) ), 19–45. |

[16] | O.A. Obeidat, Evaluation digital library services during COVID-19 pandemic: Using user’s experience in academic institution, Jordan, International Journal of Library and Information Science Studies 6: (3) ((2020) ), 39–48. |

[17] | O. Hamshari, The degree of e-resources use by postgraduate students of the faculty of educational sciences at the university of Jordan and the difficulties they face from their perspective, Zarqa Journal for Research and Studies in Humanities 19: (1) ((2018) ), 132–147. doi:10.12816/0054791. |

[18] | A.B. Al-Sherman, The Hashemite university library: Originality, contemporary and challenges: Working in light of the coronavirus pandemic as an example, Jordan Journal of Libraries and Information 55: (3) ((2020) ), 63–70. doi:10.36372/1163-055-003-003. |

[19] | H. Al Zyoud, Status Quo of Information Services Provided by Governmental University Libraries in Jordan During the Corona Pandemic From their Employees Point of View (Unpublished Master’s Thesis), University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan, 2022. |

[20] | R. Elayyan, H. Al Zyoud and M. Elfadel, Difficulties in providing e-information services in public academic libraries in Jordan during the corona pandemic from their employees point of view, The Saudi Journal of Library and Information Studies 1: (1) ((2022) ), 167–215. |

[21] | A.I.A. Algnaidi, A.K. Tarofder and S.F. Azam, The impact of trust on e-marketing and customer satisfaction in the commercial banks of a developing country, Psychology and Education 58: (1) ((2021) ), 2602–2614. doi:10.17762/pae.v58i1.1141. |

[22] | D.M. Bader, F.L. Aityassine, M.A. Khalayleh, A.Z. Al-Quran, A. Mohammad, S.I. Al-Hawary , The impact of e-marketing on marketing performance as perceived by customers in Jordan, Information Sciences Letters 11: (6) ((2022) ), 1897–1903. |

[23] | A. Alkufahy, F. Al-Alshare, F. Qawasmeh, N. Aljawarneh and R. Almaslmani, The mediating role of the perceived value on the relationships between customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and e-marketing, International Journal of Data and Network Science 7: (2) ((2023) ), 891–900. doi:10.5267/j.ijdns.2022.12.022. |