Social media-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing practices among university students in Bangladesh

Abstract

The main aim of the present study is to investigate public university students’ social media-based copyright awareness as well as their knowledge-sharing practices. Students from a public university in Bangladesh were the target population of the study. A well-structured questionnaire was designed using Google Forms and distributed to the students via different social media platforms. A total of 267 students responded to the survey. The findings of the study showed that most of the students use Facebook and YouTube to connect with their friends and family. The majority of the students were aware of SM-based copyright practices and reported giving credit to the original writer while sharing their writings on SM. The test results found significant differences in students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices based on their awareness regarding SM terms and services and self-reported frequency of violating copyright in SM. However, students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices were significantly associated with their years of experience with SM, awareness regarding SM copyright terms and services, and their self-reported frequency of copyright violation. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first attempt in Bangladesh to examine public University students’ social media-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing practices.

1.Background of the study

A copyright is a type of intellectual property that, for a limited time, gives its owner the exclusive right to reproduce, transmit, alter, exhibit, and perform creative work. Literature, art, or music are all examples of creative labor. The term “copyright” describes the legal rights granted to the creator or other entities of the original work [1]. The technology behind social media (SM) as we know it has advanced to the point where we may readily share each other’s intellectual properties. When we share others’ creative property without permission, we commit copyright infringement unless an exception allows for the reuse [2].

Copyright aims to encourage and compensate authors by allowing them property rights to create new works and make them available for enjoyment to the broader public. Protecting copyright to increase creativity by giving writers proper protection is necessary, yet there are a few obvious issues that hinder its adoption [3]. Peer-to-peer file-sharing networks are commonly used to disseminate illegally copied content [4]. Copyright continues to serve as the primary link between the act of production and the availability of knowledge and knowledge-based materials.

Copyright infringement refers to the unauthorized use of intellectual property that infringes on the author’s exclusive right to generate or create derivative works based on their work [5]. The concept behind copyright is that whatever one does is an extension of one’s “person” and should be shielded from public usage. Copyright protection is essential to the development of writing, performing, and producing. Without copyright protection, there would be little inspiration or incentive for anyone to do anything since others would be free to use it in any way they please [5]. To put it another way, any unlawful use can constitute copyright infringement. Copyright infringement is a federally recognized civil claim. It happens when a copyrighted work is reproduced, distributed, performed, publicly exhibited, or transformed into a derivative work without the owner’s consent. Piracy, making multiple copies of copyrighted content using photocopiers, duplicating web pages, and other infractions are included in this context [6]. The application of copyright law highlights a few significant topics, including the notion of copyright, copyright defense, terms for obtaining copyright, copyright registration, copyright transfer, copyright infringement and piracy, and remedies, etc. [7]. Creativity is crucial for a society’s economic and social progress. The protection offered by copyright to the works of authors, artists, designers, dramatists, musicians, architects, and makers of sound records, cinematograph films, and computer software fosters a creative environment that inspires them to produce more [8].

The proliferation of social networking sites (SNSs) has facilitated the ability of people and organizations to share information. Individuals and organizations can use social networking platforms to interact, share, sell themselves, and reach a wider audience [9]. Users of SM platforms are encouraged to post both original and third-party content. This sharing ethic on SM contrasts with the implications of copyright law, which governs the use of literary, artistic, and dramatic works [10]. The basic goal of copyright is to foster creativity by compensating inventors for their efforts [11]. As a result, copyright offers artists the opportunity to limit how others use their work. Thus, copyright infringement occurs when a person performs any of the banned activities without the copyright owner’s permission, such as copying and disseminating the work to the public.

In Bangladesh, different SM platforms including Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram, etc. are frequently being used by students and gaining popularity day by day [12]. The newly produced SM tools and technologies provide key features that enable people to see and generate global text, image, audio, and video information, as well as exchange ideas through interaction [13]. As a result, SM sites have grown in popularity in recent years, as the core kind of online information transfer and social interaction [14] is comprised of the most common and fastest-growing forms of Internet sites [15].

Users of SM generate different kinds of content such as texts, photographs, images, musical content, videos, memes, and so on, and share them on their own. Much of this stuff is probably copyrightable [16]. Even SM sites have their copyright terms and policies to protect the copyrights of user-generated content. According to the terms of service of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and Pinterest, the user maintains all rights to any user-generated content [16].

The present study aims to fill a knowledge gap among Bangladeshi University students about their SM-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing activities. Previous studies have neglected key elements, such as influences of academic and demographic variables in these practices, especially in developing country contexts. In this study, we surveyed 267 students at a public University about their social media use, copyright awareness, and knowledge-sharing habits in SM platforms. Our findings showed considerable variances based on students’ understanding and experiences, offering new insights and recommendations for improving copyright awareness and ethical knowledge sharing.

1.1.Problem statement

The extensive usage of SM platforms by University students in Bangladesh has altered information sharing and copyright norms [17]. Despite the benefits of platforms such as Facebook and YouTube, there is still a substantial gap in comprehending students’ awareness of copyright issues and ethical information sharing [12].

University students frequently breach copyright rules unintentionally due to a lack of awareness, resulting in unethical knowledge-sharing practices [18]. There is a need to investigate the elements that influence these practices, such as academic background, demographic demographics, and other associated aspects. The existing academic discourse on this topic is devoid of facts, especially in the context of a developing country like Bangladesh.

This study highlights a lack of awareness and understanding of copyright regulations among Bangladeshi University students. It seeks to explore their SM-based copyright awareness, evaluate their knowledge-sharing habits, and identify factors impacting these behaviors. By doing so, the study hopes to provide insights that may be used to guide educational initiatives, policymaking, and SM rules to raise copyright awareness and promote ethical knowledge-sharing among students.

1.2.Significance of the study

The significance of this study lies in its potential to provide comprehensive insights into Bangladeshi University students’ social media-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing practices. It can aid in the development of targeted educational programs and awareness campaigns to increase understanding of copyright laws and ethical information-sharing practices. This study can also help to foster a culture of intellectual property rights among University students. Finally, policymakers can use the findings of this study to develop or refine regulations and guidelines addressing the specific challenges and needs associated with social media use and copyright issues in academia.

1.3.Objectives and Research Questions (RQs) of the study

The main aim of the present study is to investigate public University students’ awareness regarding SM-based copyright and their knowledge-sharing practices based on the effects of their academic, demographic and other covariates. The specific objectives of the study are:

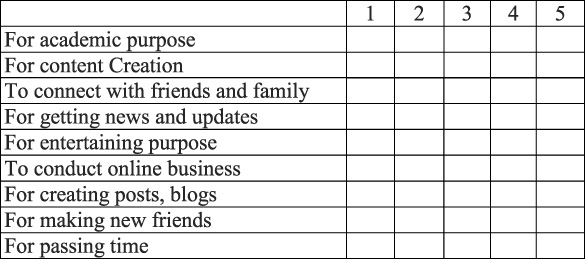

To investigate the reasons for using different SM platforms by the students

To assess students’ social media-based knowledge-sharing practices

To identify the differences in students’ social media-based knowledge-sharing practices based on their academic, demographic, and other covariates; and.

To determine the association of academic, demographic, and other covariates with students’ social media-based knowledge-sharing practices.

Based on these objectives, the following research questions have been formulated to guide this study:

RQ1: | Why do the students use different social media platforms? |

RQ2: | How do the students engage in knowledge-sharing practices on social media platforms? |

RQ3: | Are there any significant differences in students’ knowledge-sharing practices based on their academic, demographic and other covariates? |

RQ4: | Are there any significant associations in students’ knowledge-sharing practices based on their academic, demographic and other covariates? |

2.Literature review

Many studies have been conducted worldwide to investigate students’ awareness regarding copyright and copyright infringement. For example, Isiakpona [19] conducted a case study on undergraduate students’ perspective of copyright violation at the University of Ibadan. 200 students participated in the survey. The study found that though 85% of the students were aware of copyright, less than half of those really adhered to the rules set forth by the copyright law. In another study, Padil et al. [20] examined whether students’ knowledge of copyright law and awareness and knowledge of fair dealing affect students’ awareness of copyright. According to the study findings, knowledge of fair dealing and understanding of copyright law contribute to students’ awareness of copyright. Tella and Oyeyemi [6] conducted a survey on copyright violations among students at the University of Ilorin. The authors discovered that while the majority of students are aware of copyright, violations result in a shortage of supplies. The study also found that the undergraduate students of this University have moderate knowledge of copyright law and copyright violation. Korletey and Tettey [21] conducted a study to investigate copyright awareness among the students at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology and found that the majority of students acknowledged that they were aware of copyright and they must cite the sources of material they utilize in their academic writing. Adum et al. [22] conducted research to determine the degree to which undergraduate students are aware of copyright regulations. According to this research, students have extensive awareness of copyright violations, and the rate of copyright violations by the students was really low. Harrison et al. [23] surveyed to assess the degree of copyright awareness among Nazarene University undergraduate students and to enhance students’ knowledge of copyright concerns. The authors found that the majority of the respondents are aware of copyright and few of the respondents are not aware of copyright. Fiesler et al. [24] conducted a comparison between perceptions and realities of copyright tenure. Binti and Ab Rahim [25] conducted research to look into copyright violations for archives and libraries in Malaysia and the UK. The study was carried out to help Malaysian copyright laws better safeguard its libraries and archives. Bhat [26] conducted a qualitative analysis of the articles that portray the scene of various acts of legislation carried out by parliament under particular laws.

Several studies were found to investigate students’ awareness regarding Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs). For example, Ong et al. [27] investigated how Malaysian University students from two private universities perceive and are aware of intellectual property rights (IPR); Bansi and Reddy [28] discovered that organizations and universities would make an effort to improve IP registration; Mingaleva and Mirskikh [29] explored the issues with the formal act and the protection of IP and to investigate in the legal and economic settings; Nemlioglu [30] conducted a qualitative investigation to broaden the concept of IPR and compare investigate IP legislation in the UK and Turkey.

Only a few studies focused on different issues related to copyright in SM. For instance, Bosher and Yeşiloğlu [10] conducted a study about the fundamental incompatibility between copyright and social networking sites (SNSs). In addition, the study focused on the discrepancy between the prohibited activities of copying and communicating to the public under copyright law and the promotion of sharing on SNS Instagram. The authors found that Instagram users need to be properly informed about the consequences of sharing third-party material and the conditions of its user agreement. Pihlaja [31] used three case studies to examine SNS content where applying copyright laws might be problematic: videos that were posted to a site but later removed; user comments on videos posted to Facebook and YouTube; and user comments on sites that might be viewed as sensitive, like adult video pages. The study explored the legal requirements for using this resource by first giving situations where citing the copyrighted work of users is a clear legal requirement. García and Gil [32] conducted a study about the management of SM-based copyright issues using Blockchain and Semantic Web. The authors described how blockchain technologies could be used to control verified SM to ease its re-use for journalistic reasons. Jamar [33] conducted a study on the number of individuals and organizations using online SNSs like Facebook and YouTube, as well as the range of services and activities they provide, which is expected to increase. The study found that the cost and simplicity of hardware and software to modify digital works, together with social networking technologies, provide a fresh threat to copyright law.

In another study, Sharfina et al. [34] surveyed to investigate copyright infringement in prank films posted on SM. The authors developed this article using document studies, interviews, and internet polls. Results showed that the people who made the prank films suffered because of the YouTube videos containing joke material. Tao [35] conducted a study to explore SM and the current status of copyright law within the context of photography to expose the shortcomings of these rules when applied to private works of art, such as private images uploaded to SM sites. Wichtowski [36] found that ordinary SM user cannot defend their material against copyright infringers since the average expense of pursuing a copyright infringement lawsuit may be as high as two million dollars. Meese and Hagedorn [37] conducted a study to analyze how individuals value, guard, and share material on SM platforms by looking into the behaviors of SM users.

There is a scarcity of literature that shows differences in different student groups’ awareness regarding copyright. However, in a study, Sritharan et al. [38] conducted research to find out how much students at Sunway College know and understand about copyright violations. The authors created a questionnaire with three kinds of questions: demographic, internet-based, and copyright awareness. The researchers discovered that 54.3% of respondents do not comprehend the laws of copyright infringement, 73.6% of respondents do not grasp the rules, and 75.8% of respondents use the internet and are aware of copyright regulations. Pangilinan et al. [39] found that lack of understanding of copyright impairs comprehension of the repercussions of plagiarism and correct attributing, and students’ understanding of copyright is impacted by their inability to correctly credit works that are protected by copyright. In a study, Vasudevan and Suchithra [40] conducted a survey to determine Ph.D. students’ knowledge of copyright and found that the majority of scientific students are aware of the significance of copyright, the majority of non-science students are as well and responses from scientists are more knowledgeable about digital copyright than those from non-scientists. In another study, Aboyade et al. [5] found that in a University in South-West Nigeria, there is no discernible difference in the reasons given by students and lecturers for photocopying and their understanding of copyright varied per group. Samuel and Kisugu [41] conducted a study of copyright violations among federal college of education students. The authors found that a small number of students are unaware that copyright rules exist. Nonetheless, the student’s understanding of the existence of copyright rules is unsatisfactory for the simple reason that there is no obvious differentiation between those who claim complete knowledge and those who claim just partial awareness of the laws.

However, in Bangladesh, a small number of research have been conducted to investigate students’ awareness regarding copyright and related issues. For instance, Hossain [8] conducted research to illustrate the state of copyright in Bangladesh. The article is founded on current copyright laws, international agreements, many publications and pieces of writing by eminent lawyers, information from pertinent organizations, and websites. Rahman [7] investigated to comprehend the main guidelines and protections provided by the legislation, as well as the issues that may arise in Bangladeshi reality and their likely answers. Atikuzzaman and Saha [18] conducted a study among University students at Dhaka University to see how much awareness there is of current copyright regulations and how often they are violated. To investigate awareness among the students, the authors used chi-square and the Mann–Whitely U test. According to this research, the author found that the majority of respondents are familiar with copyright law and copyright violations.

From the above discussion, it is clear that researchers throughout the world have conducted a large number of studies on IPRs, copyright, and copyright violations focusing on the student community. However, no study has been found that focused on University students’ SM-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing practices, especially in the context of a developing country like Bangladesh. Hence, this gap drew the attention of the authors of the present study.

3.Methodology

3.1.Instrument development

An online survey was used to collect data from the students of a public university in Bangladesh who use different SM sites. A well-structured questionnaire with both open-ended and closed-ended questions was designed using Google Forms. The questionnaire included 5-point Likert scale items about students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices. There were two sections in the questionnaire. The first part was intended to gather information on students’ demographic, academic, and other information. The second, or main part included questions about students’ experiences of using SM, their SM-based knowledge-sharing practices, their self-reported frequency of copyright violation as well as the reasons for violating copyright in SM (see Appendix A). Some of the survey questions in the questionnaire were borrowed from earlier research [6,12,18,19,22,32,42] while the author created others.

3.2.Participants and data collection

Students from a regional public university situated on the southern coast of Bangladesh were the target population of the present study. The reason behind choosing such a type of population was to capture a distinct and diverse perspective on the topic under investigation. This group generally combines urban and rural backgrounds, providing a thorough picture of their social media usage and copyright knowledge. Emails and SM platforms i.e., Facebook, Messenger and WhatsApp were used to distribute the link to the questionnaire among the students. Convenience sampling technique was used to reach the target population of the study. In this way, a total of 267 students participated.

3.3.Data analysis

Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS version 20 were used for data analysis. The respondents’ demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Considering the type of information gathered by using a 5-point Likert scale on the purpose of using SM and students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices, various nonparametric tests were directed to investigate the differences and associations based on students’ demographic, academic and other covariates. The Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis test and Multiple Linear Regression analysis were performed in this regard.

4.Findings of the study

A total of 267 students participated in the survey. The demographic, academic, and other variables of the students as shown in Table 1 reveal that most of the students participated in the survey from the Faculty of Social Sciences (72, 27.0%). Most of them were males (151, 56.6%) and the maximum of them belonged to the 23–25 years age group (159, 59.6%). 220 (82.4%) students were from the undergraduate level of education. The majority of the students reported that they have been using SM for more than 5 years (164, 61.4%) whereas their self-reported daily hours of using SM were 3–5 hours (95, 35.6%). Most of the students responded that their departments have copyright-related courses in the curricula (170, 63.7%) and, the majority of them claimed to be aware of the copyright terms and policies in SM (228, 85.4%) before this study.

Table 1

Academic and demographic variables, SM use and copyright awareness of the students (source: table by authors)

| Variable name | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Gender | Male | 151 | 56.6 |

| Female | 116 | 43.4 | |

| Age group | 17–19 years | 3 | 1.1 |

| 20–22 years | 97 | 36.3 | |

| 23–25 years | 159 | 59.6 | |

| >25 years | 8 | 3.0 | |

| Education level | Undergraduate | 220 | 82.4 |

| Graduate | 47 | 17.6 | |

| Years of SM use | <1 year | 6 | 2.2 |

| 1–3 years | 30 | 11.2 | |

| 3–5 years | 67 | 25.1 | |

| >5 years | 164 | 61.4 | |

| Daily use of SM | <1 hour | 6 | 2.2 |

| 1–3 hours | 89 | 33.3 | |

| 3–5 hours | 95 | 35.6 | |

| 5–7 hours | 46 | 17.2 | |

| >7 hours | 31 | 11.6 | |

| Copyright course in the dept. | Yes | 170 | 63.7% |

| No | 73 | 27.3% | |

| I am not sure | 24 | 9.0% | |

| Awareness of SM copyright terms and services | Yes | 228 | 85.4% |

| No | 39 | 14.6% |

Table 2 shows that Facebook (263, 98.5%), YouTube (233, 87.3%), and WhatsApp (231, 86.5%) are the most frequently used SM sites reported by the students. However, students also use Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, Viber, and other SM sites. Students use these platforms for diverse reasons. Most reported using SM mainly to connect with their friends and family members, receive news and updates, and for entertainment purposes. They also use SM to pass the time and for academic purposes (Table 3).

Table 2

SM media platforms frequently used by the students (source: table by authors)

| SM platforms | Yes | % | No | % |

| 263 | 98.5% | 4 | 1.5% | |

| YouTube | 233 | 87.3% | 34 | 12.7% |

| 231 | 86.5% | 36 | 13.5% | |

| 150 | 56.2% | 117 | 43.8% | |

| 88 | 33.0% | 179 | 67.0% | |

| 58 | 21.7% | 209 | 78.3% | |

| Viber | 14 | 5.2% | 253 | 94.8% |

| Others | 9 | 3.4% | 258 | 96.6% |

Table 3

Purposes of using SM sites (source: table by authors)

| Category | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | Mean (SD) |

| To connect with friends & family | 6 (2.2) | 9 (3.4) | 39 (14.6) | 56 (21.0) | 157 (58.8) | 4.31 (0.99) |

| For getting news and updates | 4 (1.5) | 4 (1.5) | 45 (16.9) | 72 (27.0) | 142 (53.2) | 4.29 (0.90) |

| For entertainment purpose | 8 (3.0) | 7 (2.6) | 57 (21.3) | 48 (18.0) | 147 (55.1) | 4.19 (1.05) |

| For passing time | 8 (3.0) | 32 (12.0) | 69 (25.8) | 64 (24.0) | 94 (35.2) | 3.76 (1.14) |

| For academic purpose | 7 (2.6) | 27 (10.1) | 105 (29.3) | 62 (23.2) | 66 (24.7) | 3.57 (1.05) |

| For making new friends | 43 (16.1) | 61 (22.8) | 74 (27.7) | 52 (19.5) | 37 (13.9) | 2.92 (1.27) |

| For creating posts, blogs | 61 (22.8) | 55 (20.6) | 73 (27.3) | 43 (16.1) | 35 (13.1) | 2.76 (1.33) |

| For content creation | 109 (40.8) | 65 (24.3) | 54 (20.2) | 23 (8.6) | 16 (6.0) | 2.15 (1.22) |

| To conduct online business | 122 (45.7) | 57 (21.3) | 39 (14.6) | 23 (8.6) | 26 (9.7) | 2.15 (1.34) |

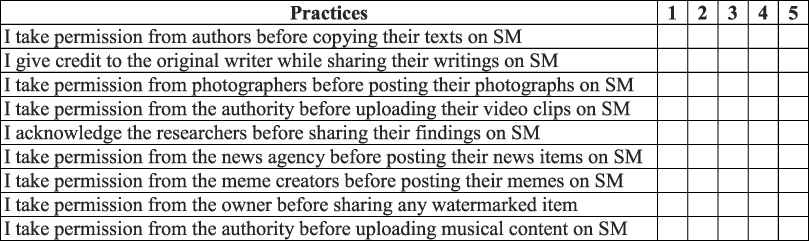

To measure their level of awareness regarding SM-based copyright practices, the students were asked to rate their frequency of performing different activities related to copyright in SM. Responses were collected on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Never to Always = 5. The mean and standard deviation (SD) were computed for each awareness item. As shown in Table 4, the highest mean score of 4.08 was obtained for “I give credit to the original writer while sharing their writings on SM”. On the other hand, the lowest mean score was obtained for the statements “I take permission from the meme creators before posting their memes on SM” (2.93), and “I take permission from the news agency before posting their news items on SM” (2.97). However, the mean scores of seven out of nine statements were higher than the average mean score of 3.

Table 4

Students’ knowledge-sharing practices in social media (source: table by authors)

| Awareness | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | Mean (SD) |

| I give credit to the original writer while sharing their writings on SM | 16 (6.0) | 18 (6.7) | 46 (17.2) | 35 (13.1) | 152 (56.9) | 4.08 (1.245) |

| I acknowledge the researchers before sharing their findings on SM | 24 (9.0) | 35 (13.1) | 52 (19.5) | 51 (19.1) | 105 (39.3) | 3.67 (1.348) |

| I take permission from authors before copying their texts on SM | 30 (11.2) | 31 (11.6) | 62 (23.2) | 37 (13.9) | 107 (40.1) | 3.60 (1.398) |

| I take permission from the owner before sharing any watermarked item | 33 (12.4) | 29 (10.9) | 65 (24.3) | 42 (15.7) | 98 (36.7) | 3.54 (1.396) |

| I take permission from photographers before posting their photographs on SM | 32 (12.0) | 33 (12.4) | 65 (24.3) | 39 (14.6) | 98 (36.7) | 3.52 (1.399) |

| I take permission from the authority before uploading musical content on SM | 43 (16.1) | 50 (18.7) | 55 (20.6) | 35 (13.1) | 84 (31.5) | 3.25 (1.472) |

| I take permission from the authority before uploading their video clips on SM | 42 (15.7) | 50 (18.7) | 56 (21.0) | 36 (13.5) | 83 (31.1) | 3.25 (1.462) |

| I take permission from the news agency before posting their news items on SM | 61 (22.8) | 53 (19.9) | 53 (19.9) | 32 (12.0) | 68 (25.5) | 2.97 (1.503) |

| I take permission from the meme creators before posting their memes on SM | 71 (26.6) | 40 (15.0) | 57 (21.3) | 36 (13.5) | 63 (23.6) | 2.93 (1.515) |

[i] Note: 1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Frequently, 5 = Always.

Table 5 describes students’ self-reported frequency of violating SM-based copyright. Nearly half of the students (132, 49.4%) reported that they never violated any copyright on SM. However, the other students violated SM-based copyright either once (30, 11.2%), a few times (63, 23.6%), several times (24, 9.0%), or many times (18, 6.7%).

Table 5

Students’ self-reported frequency of SM-based copyright violation (source: table by authors)

| Copyright violation in SM | Frequency | % |

| Never | 132 | 49.4% |

| Once | 30 | 11.2% |

| A few times (2–3 times) | 63 | 23.6% |

| Several times (4–5 times) | 24 | 9.0% |

| Many times (more than 5) | 18 | 6.7% |

| Total | 267 | 100.0% |

The students who violated copyright were asked to mention the reasons for such activities. According to Table 6, the majority of the students violated copyright because they were unaware of the consequences of doing such misconduct (56, 41.5%). The second highest number of students violated copyright in SM due to their lack of concern about the terms and conditions of SM (39, 28.9%).

Table 6

Reasons for violating SM-based copyright (N = 135) (source: table by authors)

| Reasons for violation (N = 135) | Frequency | % |

| Lack of awareness about the consequences | 56 | 41.5% |

| Lack of concerns about the terms and conditions of SM | 39 | 28.9% |

| There is no punishment | 18 | 13.3% |

| I do not feel the need to follow the copyright policy | 9 | 6.7% |

| My friend did so | 7 | 5.2% |

| I do not care about the policy | 6 | 4.4% |

| Total | 135 | 100.0% |

Table 7

Differences in students’ social media-based knowledge-sharing practices based on their academic, demographic, and other covariates (source: table by authors)

| Awareness | Gendera | Ageb | Edu levela | Years of expb | Daily hoursb | Copyright coursea | Terms and service awarenessa | Freq. of violationb |

| I give credit to the original writer while sharing their writings on SM | 0.291 | 0.454 | 0.086 | 0.182 | 0.359 | 0.599 | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| I acknowledge the researchers before sharing their findings on SM | 0.248 | 0.418 | 0.165 | 0.099 | 0.561 | 0.702 | 0.001*** | 0.000*** |

| I take permission from authors before copying their texts on SM | 0.223 | 0.934 | 0.020* | 0.024* | 0.594 | 0.622 | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| I take permission from the owner before sharing any watermarked item | 0.001*** | 0.537 | 0.066 | 0.040* | 0.282 | 0.956 | 0.005** | 0.012* |

| I take permission from photographers before posting their photographs on SM | 0.333 | 0.991 | 0.211 | 0.099 | 0.907 | 0.875 | 0.012* | 0.000*** |

| I take permission from the authority before uploading musical content on SM | 0.307 | 0.940 | 0.189 | 0.192 | 0.531 | 0.725 | 0.003** | 0.000*** |

| I take permission from the authority before uploading their video clips on SM | 0.707 | 0.808 | 0.935 | 0.294 | 0.592 | 0.129 | 0.030* | 0.000*** |

| I take permission from the news agency before posting their news items on SM | 0.849 | 0.453 | 0.784 | 0.393 | 0.361 | 0.184 | 0.071 | 0.014* |

| I take permission from the meme creators before posting their memes on SM | 0.085 | 0.828 | 0.050* | 0.164 | 0.093 | 0.494 | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

[i] aMann–Whitney U test, bKruskal Wallis test, *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; **p ≤ 0.001.

4.1.Differences in students’ social media-based knowledge-sharing practices based on their academic, demographic, and other covariates

To identify the differences in students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices based on their academic, demographic, and other covariates, the study used different non-parametric tests, i.e., the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal Wallis test. Table 7 shows the test results where Mann–Whitney U tests were run for students’ gender, education level, participation in the copyright-related course, and familiarity with copyright terms and services in SM. On the other hand, Kruskal Wallis tests were performed for their age groups, years of using SM, daily hours of using SM, and self-reported frequency of violating copyright in SM.

The Mann–Whitney U test results showed that there were no significant differences in male and female students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices in eight statements but significant differences were found in only one statement, i.e., “I take permission from the owner before sharing any watermarked item”. In this case, the mean value of female students was higher than the mean value of the male students meaning that the female students take permission from the owners before sharing their watermarked items on SM compared to the male students.

In terms of education level, the test results found no significant differences in seven statements except for two cases, i.e., “I take permission from authors before copying their texts on SM” and “I take permission from the meme creators before posting their memes on SM”. In these cases, the mean values of the graduate students were higher than the mean values of the undergraduate students meaning that the graduate students showed positive responses to these statements compared to the undergraduate students. In terms of whether the students participated in any copyright-related course, the test results found no significant differences between the students who participated in the course and those who did not.

In terms of their awareness regarding the copyright terms and services of SM sites, the test results found significant differences in eight statements except in one case. In these eight statements, the mean values of the students who are aware of the copyright terms and services in SM were higher than the mean values of the students who are not aware meaning that the students who are aware of the SM terms and services demonstrate positive awareness regarding copyright practices in SM.

The Kruskal–Wallis test results showed that there were no significant differences among students from different age groups in terms of their SM-based knowledge-sharing practices. Based on the years of using SM, the test results found significant differences in two statements, i.e., “I take permission from authors before copying their texts on SM” and “I take permission from the owner before sharing any watermarked item”. In these cases, the mean values of the students having more than 5 years of experience with SM were higher than the mean values of the students with other experiences meaning that the students who are using SM for more than 5 years possess a positive awareness of these cases compared to others. However, based on the daily hours of using SM, the test results found no significant differences in students’ SM-based copyright awareness.

Lastly, based on students’ self-reported frequency of violating copyright in SM, the test results found significant differences in all the statements. The mean values of the students who “never” violated copyright in SM were higher than the mean values of the students who violated copyright at least once or more times meaning that students who never violated copyright in SM have positive awareness regarding SM-based copyright practices compared to the students who violated it once or more times.

4.2.Association of academic, demographic, and other covariates with students’ social media-based knowledge-sharing practices

This study used multiple linear regressions with the total knowledge-sharing practices scores as dependent variables and demographic, academic, and other covariates as independent variables. Table 8 indicated that years of experience with SM (𝛽 = 0.163, p < 0.05), awareness regarding copyright terms and services (𝛽 = −0.163, p < 0.01), and frequency of violating copyright in SM (𝛽 = −0.244, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with the total awareness score. However, other demographic and academic variables, i.e., gender, age group, education level, hours of using SM every day, and participation in a copyright-related course in the department were not found to be significantly associated with the total knowledge-sharing practice scores. In combination, demographic and academic variables accounted for 12.2% of the variability in awareness, R2 = 0.148, adjusted R2 = 0.122, F (8, 258) = 5.601, p < 0.001.

Table 8

Association of academic, demographic, and other covariates with students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices (source: table by authors)

| b | Std. error | Beta | t | p-value | |

| Dependent Variable: Total knowledge-sharing practice scores | |||||

| (Constant) | 39.311 | 5.933 | - | 6.626 | 0.000 |

| Gender | 1.778 | 1.453 | 0.076 | 1.224 | 0.222 |

| Age group | −2.090 | 1.333 | −0.101 | −1.568 | 0.118 |

| Education level | 3.286 | 1.867 | 0.108 | 1.760 | 0.080 |

| Years of experience with SM | 2.419 | 0.954 | 0.163 | 2.535 | 0.012* |

| Hours spend on SM | −0.576 | 0.672 | −0.051 | −0.857 | 0.392 |

| Copyright course | −1.205 | 1.053 | −0.068 | −1.145 | 0.253 |

| SM copyright terms and service-related awareness | −5.329 | 1.995 | −0.163 | −2.672 | 0.008** |

| Copyright violation frequency | −2.177 | 0.527 | −0.244 | −4.131 | 0.000*** |

[i] *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; Adjusted R2: 12.2%.

5.Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate public University students’ SM-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing practices based on the effects of their academic, demographic and other covariates. The first research question (RQ1) of the study was related to investigating students’ use of different SM platforms. Findings showed that most of the students use Facebook and YouTube mainly to connect with their friends and family, to get news and updates and for entertainment purposes. The reason behind this is Facebook is the most used SM platform in Bangladesh [43]. This finding is quite relevant in the context of Bangladesh and is supported by the findings of several previous studies [12,17,42] where the authors found that Facebook and YouTube are the most used SM platforms in Bangladesh and are being used for a variety of purposes including communication with friends and family members and for receiving updated information.

The RQ2 of the study was related to assessing students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices. The findings indicated that the students were aware of different SM-based knowledge-sharing practices. However, the majority of them reported giving credit to the original writer while sharing their writings on SM, acknowledging the researchers before sharing their findings on SM and taking permission from authors before copying their texts on SM. This finding is a clear indication that the student communities adhere to the rights of the user-generated content in SM and thus they are aware of the consequences of violating these rights [44,45]. However, this finding is quite opposite to the findings of a study by [46] where the authors found that the younger generation had no moral or ethical concerns regarding the practice of online copyright infringement.

The RQ3 was related to identifying the differences in students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices based on their academic, demographic, and other covariates. Findings showed that there were no significant differences in students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices based on their gender, age group, education level, years of experience with SM, daily hours of using SM and their participation in any copyright-related course in their department, except for a few cases. This demonstrates a striking consistency in knowledge-sharing habits across various student populations. This uniformity shows that criteria generally thought to influence online behavior, such as age, gender, and educational background, may have little influence on how students share knowledge on social media in this setting. This finding is somewhat different from the findings of a study by [18] where the authors found a significant difference among Bangladeshi public University students’ copyright awareness based on their gender and education level. However, significant differences were found in their knowledge-sharing practices based on their awareness regarding the terms and services of SM and their self-reported frequency of violating copyright in SM. In these cases, the study revealed that students who are aware of SM terms and services have a more positive awareness regarding SM-based copyright practices. This finding is quite relevant as the terms and services are provided to restrain users from violating copyright. Students who are informed about these aspects are more likely to recognize the importance of respecting intellectual property rights and avoiding copyright infringement. Similarly, in terms of students’ self-reported frequency of violating copyright in SM, the test results indicated that the students who never violated copyright in SM have positive awareness regarding SM-based knowledge-sharing practices compared to the students who violated it once or more times.

The RQ4 was related to determining the association of academic, demographic, and other covariates with students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices. The linear regression analysis results revealed that students’ SM-based knowledge-sharing practices were significantly associated with their years of experience with SM, awareness regarding SM-based copyright terms and services, and their self-reported frequency of copyright violation. The significant association between years of experience with SM and knowledge-sharing habits implies that more experienced users create consistent and sophisticated means of sharing knowledge, most likely due to their familiarity with SM functions and online norms. Awareness of SM-based copyright terms and services also predicts knowledge-sharing practices, emphasizing the necessity of educating students about copyright rules and their consequences. Informed students are more cautious and responsible when sharing information. Furthermore, students who frequently break copyright rules demonstrate distinct sharing habits, which could be related to a lack of awareness, disdain for legal ramifications, or opposing attitudes regarding intellectual property, resulting in more liberal sharing without adequate attribution.

6.Implications, limitations and future research directions

The study’s findings offer valuable insights into improving students’ copyright awareness on SM platforms. The findings have several practical implications for educators, policymakers, and institutions. Educational institutions should consider copyright education. The findings might encourage students’ critical thinking and ethical awareness when it comes to sharing content online. Educators may help produce responsible digital citizens by teaching students to evaluate the validity and legality of the content they encounter or share. Besides, researchers and policymakers might consider developing and promoting digital tools, resources, and guides that help students easily determine whether they can use, modify, or share certain content legally and ethically on SM platforms.

However, the study has certain limitations. First, the design of the study limits our ability to demonstrate causal links between academic and demographic characteristics and copyright awareness. Furthermore, relying on self-reported data presents the possibility of recollection and social desirability biases, which could alter the accuracy of participants’ stated behaviors and awareness levels. The study’s sample mix and size may further restrict the findings’ generalizability to larger populations. The changing nature of SM platforms and copyright rules may not have been completely accounted for, thus reducing the study’s applicability over time. Finally, the study looks at a small set of demographic characteristics that are related to awareness of SM-based copyright practices. Cultural views toward copyright, academic discipline, and socioeconomic position may all have an impact on awareness, but these were not included in the present study.

Future studies could examine perceptions of SM-based copyright procedures across cultures. Long-term research could monitor changes in consciousness over time and determine what influences them. Interviews could improve the understanding of students’ thoughts and actions. Investigating additional characteristics such as culture and wealth may provide a more complete picture of how students comprehend and respect copyright restrictions on SM.

7.Conclusion and recommendations

This study investigated social media-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing activities among students at a regional public institution in southern Bangladesh. The findings revealed that most students are aware of copyright rules on social media and often give credit to original authors when sharing content. Significant disparities in knowledge-sharing behaviors were shown to be related to students’ education level, social media terms and services awareness and frequency of copyright infringement. These findings underscore the importance of focused educational programs to raise copyright awareness and encourage ethical knowledge sharing, laying the groundwork for future study and policy development.

To effectively communicate social media-based copyright awareness and knowledge-sharing practices among Bangladeshi University students, it is recommended that copyright education be integrated into the University curriculum via modules on digital literacy and copyright laws, which can be developed in collaboration with educational boards. Professionals should schedule regular workshops and seminars, making them necessary for new students and part of continuous professional development. Furthermore, online resources and social media campaigns should be created to educate kids on these topics constantly. Establishing student ambassadors and peer education programs can use peer influence to promote ethical behavior. Clear University policies on copyright violations, including clear consequences and encouragement for compliance, should be enforced. Collaborating with social media platforms to deliver educational content and tools directly on their sites will help to boost these efforts. Finally, developing systems for regular student input will ensure that these educational strategies are continuously improved and relevant.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author biographies

Mostafizur Rahman is a Master of Social Sciences (MSS) student at the Institute of Information Sciences, Noakhali Science and Technology University. He completed his graduation from the same institute. His research interests include copyright and IPRs, social media analysis, data science, information marketing and knowledge management.

Md. Atikuzzaman is currently serving as a Lecturer at the Institute of Information Sciences, Noakhali Science and Technology University, Bangladesh. He obtained the first position in his graduation and postgraduation from the University of Dhaka. He is the treasurer of the ‘Association for Information Science and Technology’ (ASIS&T) South Asia chapter and a life member of the Library Association of Bangladesh (LAB). As a young researcher, his interest revolves around the use of the internet and technologies, social media, information literacy, knowledge management, cloud computing, and so on.

Appendices

Appendix A.

Appendix A.Demographic information

1.1 Gender: □ Male□ Female

1.2 Age: □ 17–19 years□ 20–22 years□ 23–25 years

□ More than 25 years

1.3 Education Level: □ Undergraduate□ Graduate

1.4 Your experience on social media

□ Less than 1 year□ 1–3 years□ 3–5 years

□ More than 5 years

1.5 Your daily hours of using social media

□ Less than 1 hour□ 1–3 hours□ 3–5 hours

□ 5–7 hours □ More than 7 hours

1.6 Does your department provide an introductory course on copyright?

□ Yes□ No□ I am not sure

1.7 Are you aware of the copyright terms and services in social media?

□ Yes□ No

Appendix B.

Appendix B.Social media use, knowledge sharing practice and copyright awareness

2. Which of the following social media platforms do you usually use?

□ Facebook□ Instagram□ Twitter□ YouTube

□ WhatsApp□ LinkedIn□ Viber

□ Others, please mention______

3. How frequently do you use social media for the following purposes? (1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Frequently, 5 = Always)

4. How frequently do you perform the following practices while using social media? (Here, 1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Frequently, 5 = Always)

5. Did you violate any copyright law in social media?

□ Never□ Once□ A few times (2–3 times)

□ Several times (4–5 times)□ Many times (more than 5)

6. If you violated, then what was the reason for violating copyright in social media?

□ Lack of awareness□ Lack of proper punishment

□ Lack of concerns about the terms and conditions of SM

□ I do not feel the need to follow copyright policy

□ My friend did so□ I do not care about the policy

□ Others, please mention_________

References

[1] | R. Abduh and F. Fajaruddin, Intellectual property rights protection function in resolving copyright disputes, International Journal Reglement & Society (Ijrs) 2: (3) ((2021) ), 170–178. |

[2] | C.A. Harkins, Tattoos and Copyright Infringement: Celebrities, Marketers, and Businesses Beware of the Ink, Vol. 10: , Lewis & Clark Law Review, (2006) , p. 313. |

[3] | T.R. Mahmud, Legal mechanisms for copyright protection & its efficacy in economical uplift of Bangladesh, IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 21: (7) ((2016) ), 37–42. doi:10.9790/0837-2107073742. |

[4] | J.H. Gerlach, F.Y. Kuo and C.S. Lin, Self sanction and regulative sanction against copyright infringement: A comparison between US and China college students, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60: (8) ((2009) ), 1687–1701. |

[5] | W.A. Aboyade, M.A. Aboyade and B.A. Ajala, Copyright infringement and photocopy services among University students and teachers in Nigeria, International Journal of Arts & Sciences 8: (1) ((2015) ), 463. |

[6] | A. Tella and F. Oyeyemi, Undergraduate students’ knowledge of copyright infringement, Brazilian Journal of Information Science 11: (2) ((2017) ), 38–53. |

[7] | M.M. Rahman, Copyright and related rights in Bangladesh: The laws and the reality, International Journal of Multidisciplinary Sciences and Advanced Technology 1: (12) ((2020) ), 43–51. |

[8] | M.M. Hossain, Present situation of copyright protection in Bangladesh, Bangladesh Research Publications Journal 7: : ((2012) ), 99–109. |

[9] | L. Lundell, Copyright and Social Media: A Legal Analysis of Terms for Use of Photo Sharing Sites, (2015) . |

[10] | H. Bosher and S. Yeşiloğlu, An analysis of the fundamental tensions between copyright and social media: The legal implications of sharing images on Instagram, International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 33: (2) ((2019) ), 164–186. |

[11] | B. Day, In defense of copyright: Record labels, creativity, and the future of music, Seton Hall J. Sports & Ent. L. 21: ((2011) ), 61. |

[12] | Md. Atikuzzaman and S. Akter, Hate speech in social media: Personal experiences and perceptions of university students in Bangladesh, Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 72: (8/9) ((2022) ), 835–851. |

[13] | E. Akar and B. Topçu, An examination of the factors influencing consumers’ attitudes toward social media marketing, Journal of Internet Commerce 10: (1) ((2011) ), 35–67. |

[14] | J. Raacke and J. Bonds-Raacke, MySpace and facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory to exploring friend-networking sites, CyberPsychology & Behavior 11: (2) ((2008) ), 169–174. |

[15] | Nielsen-Wire. Social media stats: Myspace music growing, Twitter’s big move, July 2009. Available from: https://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/online_mobile/social-media-stats-myspace-music-growing-twitters-big-move. |

[16] | J.G. Alm, Sharing copyrights: The copyright implications of user content in social media, Hamline J. Pub. L. & Pol’y. 35: ((2014) ), 103. |

[17] | M. Atikuzzaman, Social media use and the spread of COVID-19-related fake news among University students in Bangladesh, Journal of Information & Knowledge Management 21: (Supp 01) ((2022) ), 2240002. |

[18] | M. Atikuzzaman and M. Saha, Students’ awareness and perceptions regarding copyright infringement: A study in a public University in Bangladesh, International Journal of Information and Knowledge Studies 1: (1) ((2021) ). |

[19] | C.D. Isiakpona, Undergraduate students’ perception of copyright infringement: A case study of the University of Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria, Library Philosophy and Practice ((2012) ). |

[20] | H.M. Padil, A.F. Azmi, N.L. Ahmad, N. Shariffuddin, N.A. Nudin and F.A. Razak, Awareness on Copyright Among Students. in: International Invention, Innovative & Creative (InIIC) Conference, (2020) . |

[21] | J.T. Korletey and E.K. Tettey, An investigation of copyright awareness at Kwame Nkrumah University of science and technology (KNUST), International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) 20: : ((2015) ), 390–404. |

[22] | A.N. Adum, O. Ekwenchi, E. Odogwu and K. Umeh, Awareness of copyright laws among select Nigerian University students, JL Pol’y & Globalization 86: ((2019) ), 183. |

[23] | J.N. Harrison, J. Otike and E. Bosire, Evaluation of Copyright Awareness among Undergraduate Students: A Case Study of Africa Nazarene University, Kenya. |

[24] | C. Fiesler, C. Lampe and A.S. Bruckman, Reality and perception of copyright terms of service for online content creation. in: Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, (2016) , pp. 1450–1461. |

[25] | Ab.H.Y. Rahim, A Comparative Analysis on Copyright Exception for Libraries and Archives Between Malaysia, UK and US, (2016) . |

[26] | S.R. Bhat, Innovation and intellectual property rights law—An overview of the Indian law, IIMB Management Review 30: (1) ((2018) ), 51–61. |

[27] | H.B. Ong, Y.J. Yoong and B. Sivasubramaniam, Intellectual property rights (IPR) awareness among undergraduate students, Corporate Ownership & Control 10: (1–7) ((2012) ), 711–714. |

[28] | R. Bansi and K. Reddy, Intellectual property from publicly financed research and intellectual property registration by universities: A case study of a University in South Africa, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 181: : ((2015) ), 185–196. |

[29] | Z. Mingaleva and I. Mirskikh, The problems of legal regulation and protection of intellectual property, Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 81: : ((2013) ), 329–333. |

[30] | I. Nemlioglu, A comparative analysis of intellectual property rights: a case of developed versus developing countries, Procedia Computer Science 158: : ((2019) ), 988–998. |

[31] | S. Pihlaja, More than fifty shades of grey: Copyright on social network sites, Applied Linguistics Review 8: (2–3) ((2017) ), 213–228. |

[32] | R. García and R. Gil, Social media copyright management using semantic web and blockchain. in: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Information Integration and Web-based Applications & Services, (2019) , pp. 339–343. |

[33] | S.D. Jamar, Crafting Copyright Law to Encourage and Protect User-Generated Content in the Internet Social Networking Context, Vol. 19: , Widener LJ, (2009) , p. 843. |

[34] | N.H. Sharfina, H. Paserangi, F.P. Rasyid and M.I.N. Fuady, Copyright issues on the prank video on the youtube. in: International Conference on Environmental and Energy Policy (ICEEP 2021), Atlantis Press, (2021) , pp. 90–97. |

[35] | E.J. Tao, A picture’s worth: The future of copyright protection of user-generated images on social media, Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 24: (2) ((2017) ), 617–636. |

[36] | R. Wichtowski, Increasing copyright protection for social media users by expanding social media platforms’ rights, Duke L. & Tech. Rev. 15: ((2016) ), 253. |

[37] | J. Meese and J. Hagedorn, Mundane content on social media: Creation, circulation, and the copyright problem, Social Media+ Society 5: (2) ((2019) ), 2056305119839190. |

[38] | K. Sritharan, V.M.E. Wee, R.M.Y. Chin and E.E.M. Jong, A case study: The knowledge and awareness levels of copyright infringement among learners utilising digital technologies in Sunway College Johor Bahru. |

[39] | R.R. Pangilinan, M.M.T. Yutuc, J.C. Nuqui, L.L. Garnica and S. Ayodele, Study on copyright awareness among college students, International Journal of Knowledge Engineering 6: (1) ((2020) ), 35–39. |

[40] | T.M. Vasudevan and K.M. Suchithra, Copyright awareness of doctoral students in Calicut University campus, Int. J. Digit. Libr. Serv. 3: (4) ((2013) ), 94–110. |

[41] | O.A. Samuel and O.A.M. Kisugu, Copyright Infringement among Students of the Federal Polytechnic Ilaro and Federal College of Education, Osiele, Abeokuta, World Journal of Innovative Research (WJIR) 6(3) (2019), 11--16. https://www.wjir.org/download_data/WJIR0603039.pdf . |

[42] | I. Jahan and S.Z. Ahmed, Students’ perceptions of academic use of social networking sites: A survey of University students in Bangladesh, Information Development 28: (3) ((2012) ), 235–247. |

[43] | StatCounter. Social Media Stats Bangladesh, 2023. Available from: https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/bangladesh. |

[44] | M. Luca, User-generated content and social media. in: Handbook of media Economics. Vol. 1, North-Holland, (2015) , pp. 563–592. |

[45] | S.K. Shriver, H.S. Nair and R. Hofstetter, Social ties and user-generated content: Evidence from an online social network, Management Science 59: (6) ((2013) ), 1425–1443. |

[46] | D.P. Collopy and D. Bahanovich, Music experience and behaviour in young people: Winter 2012–2013 [2011 National Survey]. |