Is the tail wagging the dog? Understanding the value of incentives in peer review

Abstract

Incentives for efforts expended in peer review remain controversial, as one of us [https://www.morressier.com/o/event/655b8f316515150019d5f90b/sessions/6569ca7c8d0e640013427ec3?eventId=655b8f316515150019d5f90b] reported at the recent APE Meeting in Berlin 2024. Publishers and researchers have different views on if, and how, peer review should and could be rewarded. We surveyed researchers regularly performing peer review for journals as well as editors and journal managers who assign articles in order to look at the use of incentives and how these influence behavior. Incentives for peer review remain relatively rare overall: Results show that more than 80% of editorial board members said they ‘did not reward’ or ‘rewarded in less than 25% of cases’, while, at the same time, the same proportion of respondents felt that rewarding peer reviewers would be a good idea. The majority of our respondents felt that giving ‘something was better than nothing’ and that a token incentive would help. In terms of actual rewards, APC tokens are both wanted (52%) and awarded (42%) while certificates are given far more (43%) than they are actually wanted (12%). Surprisingly, money is given out far less (4%) than wanted (27%); this reward is not actually desired as much as one might expect.

1.Background

The peer review process necessitates the survival and maintenance of a complex relationship between authors, editorial boards, ‘reviewers’ (active researchers working in specific disciplines) and ‘publishers’ (either for books or academic journals). The process is in part altruistic even though researcher-reviewers often feel ‘taken advantage of’ or even ‘exploited’ as they do a lot of work assessing articles without monetary compensation and recognition while publishers are the ones making financial profits. This nature of the relationships means that whether, or not, to reward peer reviewers for their work remains highly controversial. Is paying researchers for the service of reviewing in a process that generates profits for businesses ethical and legitimate or not? In other words: Does the payment influence a researcher’s independent judgment on the quality of research results? And if so, how can product categories like books and journal articles be handled completely differently? Data show that incentives, especially financial rewards, are much more common in book publishing than they are for academic journal articles [2]. Peer reviewers turn down requests for a number of reasons, as our data show (Fig. 1).

Peer review entails experts within a specific field assessing and providing feedback on research papers prior to their publication in journals or presentation at conferences. This process is the cornerstone of academic publishing: Peer review ensures that content can be trusted, re-used, and cited. However, despite its significance, numerous peer reviewers do not receive monetary compensation and rarely receive recognition for their valuable time and expertise. Among the frequent inquiries we receive from researchers are questions such as, ‘What constitutes payment for peer review?’ and ‘Why is compensation for peer review uncommon?’

Thus, in order to assess the significance and utility of incentives in peer review, we undertook a Reviewer Credits survey at the end of 2023. We leveraged our membership base and used social media channels as a control group. Results and key takeaways are presented and discussed in this article, alongside a series of recommendations both for the future of peer review incentives and their use and utility in academic publishing. It is worth noting at the outset that although peer reviewers feel hard done by, and often exploited by journals and publishers, actually about 60% of all published content (books and journals) in 2023 will involve some kind of recompense: article processing charges (APC) tokens, defrayed publishing fees, or credits from Reviewer Credits.

Fig. 1.

The shape of peer review: Why do some peer reviewers turn down requests from journals and editors?

2.Methods and results: The reviewer credits peer review incentives survey

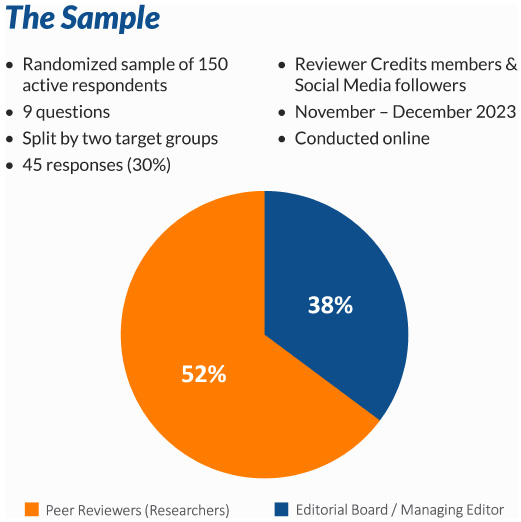

We leveraged our social media and networks within academia and the publishing industry to reach out to a representative sample of peer reviewers and editorial board members (Fig. 2). We asked these cohorts a series of nine questions which we report on in this article. Our survey was conducted in November and December 2023, entirely online.

Fig. 2.

The randomized sample used in the Reviewer Credits survey.

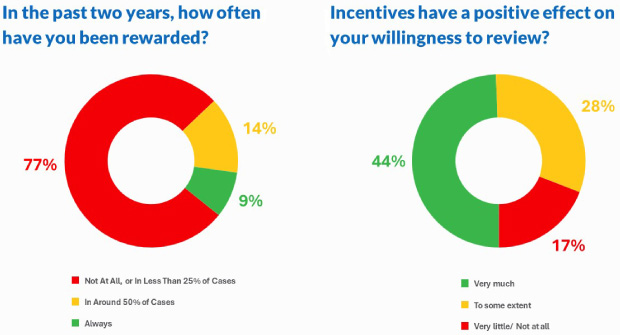

We started off by asking how often, over the last two years, they had been offered some kind of reward by a journal or publisher for the work they had done assessing a paper. Our results show that the clear majority of researchers, more than 75%, had not been offered any kind of reward for peer review, or that this happened infrequently (in less than 25% of cases). This result is at odds with perceptions in the publishing industry: Journals tend to feel that they do provide rewards and incentives for peer review. It is also striking that a small proportion of reviewers (23%) have actually been rewarded (in more than 50% of cases) for their work for journals.

We were then interested whether reviewers saw positive effects, if publishers offered incentives. The intention was to address publishers’ frequent concerns about articles in need of peer review growing faster than the number of researchers actually reviewing content. Our results show that in 44% of answers, reviewers claim that incentives actually do have a positive effect on their willingness to review (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Summary of responses from peer reviewers.

In terms of editors, our survey showed that more than 80% of journal editors do not reward peer reviewers. This is surprising given the results reported earlier. Indeed, more than 80% of respondents felt that appropriate rewarding would have a positive effect on peer review behavior. Indeed, it does seem clear that attractive rewards appear to be less important overall than simply giving reviewers something in return for their efforts, so they feel at least appreciated.

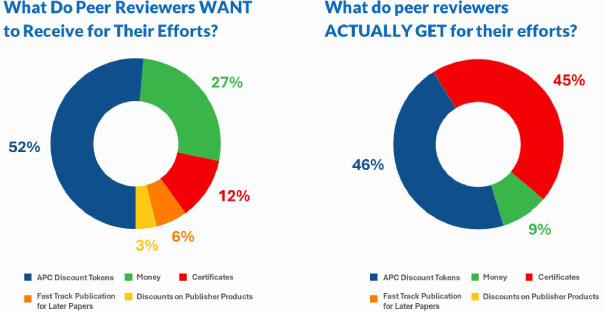

The most common kind of reward provided by journals and publishers to reviewers tends to be the use of APC tokens. These are wanted by 52% of reviewers and are actually given in 42% of cases. However, these rewards ‘hook’ peer reviewers into particular journal or publisher ecosystems. Certificates, viewed by journals and publishers as an effective rewarding system and hence being used more broadly, are actually only really appreciated in 12% of cases - these are given out as ‘rewards’ in 43% of cases. Similarly, a low number of reviewer respondents (27%) suggested that money would be appropriate as a reward for efforts working on papers: Payments are made in far fewer cases (4%), at least in journal peer review (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Differences in expected and realized incentives for peer review.

3.Discussion and recommendations

Peer reviewing is a time-consuming and intellectually demanding task, and it is seen as the core value creation of the academic publishing process. Reviewers are asked to read and evaluate manuscripts, provide constructive feedback, and ensure that research meets the standards of the journal or conference. This process can take hours, and sometimes even days, depending on the complexity of the work being reviewed. So, why are so many peer reviewers not compensated for their efforts despite the fact that our survey results clearly show that the use of incentives, especially cash and APC tokens, can both speed up the process and enhance its effectiveness?

Informal discussions within STM publishing and with researchers and academics across the Reviewer Credits network reveal that several factors contribute to this interesting phenomenon. These include tradition: The practice of unpaid peer review has a long history in academia. It is seen as a professional duty and a way for researchers to contribute to their academic communities. Some ethics researchers also feel that adding clear incentives to peer review will somehow ‘pollute’ the process. At the same time, it is also true that many academic journals and conferences operate on limited budgets, especially those that are not-for-profit or have a narrow readership. Allocating funds for reviewer compensation may strain their resources.

Peer review is often considered a voluntary service provided by researchers to maintain the integrity of their field. It is viewed as part of one’s professional responsibilities. In sum, this means that paying peer reviewers may raise concerns about conflicts of interest, as reviewers may have financial incentives to favor certain authors or research outcomes. It is therefore often considered more appropriate to provide reviewers with non-monetary rewards, such as recognition, career advancement, and the opportunity to stay informed about the latest research in their field.

Nevertheless, some journals and conferences offer token honoraria or small payments to peer reviewers as a gesture of appreciation for their time and expertise. While these payments may not fully compensate for the effort involved, they acknowledge the value of reviewers’ contributions. We are starting to implement this kind of rewarding structure at Reviewer Credits.

It is important to mention that peer review is not free of inequalities, even without payments or non-financial benefits. For researchers, it makes a big difference which journal or book program they review for - not only reputationally, but also with respect to why many researchers review regularly, namely to stay up to date on the progress of research in their domain. It is a question for further research, whether economic benefits in peer review can have the effect of balancing existing inequalities in the peer review system.

3.1.How to redress the balance?

Academic institutions and funding agencies could consider providing financial support or incentives for researchers who engage in peer review. This could be in the form of grants, awards, or professional development opportunities. Publishers can also further take steps to diversify their reviewer pools, ensuring that a broader range of voices is heard in the peer review process. This may involve actively recruiting reviewers from underrepresented groups.

Similarly, journals should also recognize the contributions of peer reviewers more publicly by listing their names and affiliations on published articles or conference proceedings. This recognition can serve as a form of compensation. Providing training and resources to peer reviewers can help them perform their duties more efficiently and effectively, reducing the time burden. Some organizations are exploring alternative models of peer review, such as crowd-sourced review or post-publication review, where reviewers and authors engage in open discussions about the research after it is published.

3.2.What are alternative models in digital academic publishing?

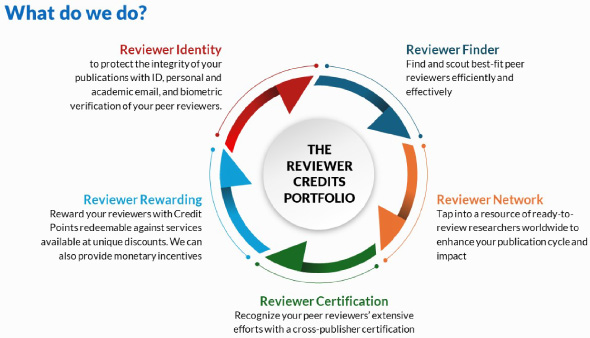

Digitization has opened new opportunities to create transparency and equity in peer review. Reviewer Credits was created by researchers to make peer review visible on academic records and to reward time spent on this task. We also aim to rectify negative perceptions about peer review amongst both authors and editors in our vision for Reviewer Credits: We provide solutions for many of the challenges authors face during the peer review process (and therefore publishers) (Fig. 5).

The model is based on reviewer verification, another key issue for publishers globally. As discussed, from the perspective of peer reviewers’ and understanding their time constraints, publishers need to create a competitive incentive to other activities – first and foremost doing research or writing a paper – in favor of peer review. In a research climate increasingly characterized by a demand to hit different measurable performance indicators, how can researchers be expected to invest a substantial portion of their time on an ‘invisible’, unrewarded task? One peer review easily takes them four to six hours of work (or more if English language is an issue) – and research indicates that an aggregate of 15,000 years of peer review were conducted in 2020 alone [3].

Fig. 5.

The Reviewer Credits portfolio.

3.3.Equitability

Reviewer Credits journal and publisher partners are given the opportunity to reward their reviewers. Partners award Credits to peer reviewers for work done, and these are accrued by researchers and can be redeemed for products and services useful for their work including publishing discounts, editorial and translation services. Giving due credit to researchers also increases review request acceptance.

Peer review is a vital component of the publishing ecosystem, yet little attention has been paid to address its specific challenges in the past decade. Publishers and libraries focused on making digital content more open and accessible – no doubt a worthwhile piece of work – but missed (with a few notable exceptions) out on those elements of the workflow that did not directly contribute to article output.

Now is the time to take the next steps in digitizing academic publishing, and peer review needs to be part of that. Ultimately, the issue of compensation for peer review is a complex one, with no one-size-fits-all solution. It is important to strike a balance between recognizing the value of reviewers’ time and expertise and preserving the integrity and impartiality of the peer review process.

3.4.What about money?

While monetary compensation may not be feasible for all journals and conferences, finding creative ways to acknowledge and reward peer reviewers is essential. One solution is Reviewer Credits: A combination of incentives, recognition, and clear certification for peer reviewers. Our goal is to create a system that is fair, sustainable, and inclusive, where researchers are motivated to provide high-quality reviews without undue burden.

Finally, the question of why peer reviewers are often not paid raises important issues about equity, recognition, and the sustainability of the peer review system. As the academic community continues to grapple with these challenges, it is crucial to engage in thoughtful discussions and explore innovative solutions to ensure that the peer review process remains robust and serves the best interests of science and scholarship.

Acknowledgements

We thank Astrid Engelen for the opportunity to contribute this paper and for her comments on an earlier draft. We also thank our colleagues at Reviewer Credits for their help and support (especially Emre Danisan, Dmytro Shestakhov and Catherine Anderson) as well as the organizers of the APE Conference 2024.

References

[1] | |

[2] | I. Vesper, Peer reviewers unmasked: Largest global survey reveals trends, Nature News (2018), https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-06602-y. |

[3] | A. Dance, Stop the peer-review treadmill. I want to get off, Nature Careers (2023), https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00403-8. |