Health literacy: Global advances with a focus upon the Shanghai Declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

Abstract

In a steadily growing effort, the world has witnessed more than three decades of effort in research, practice, and policy to socially construct what has been identified as ‘health literacy. While much of the earlier work in health literacy was in the United States, the extent of scholars and practitioners is now truly global. To advance international health literacy, the chapter highlights the role of the World Health Organization (WHO) and a series of international conferences that began in 1980s. More specifically, the chapter outlines World Health Organization’s overarching health literacy efforts, notes the importance of health literacy within WHO’s new organization structure, briefly describes how the concept of health literacy emerged throughout a generation of the WHO’s international conferences, suggests an ethical foundation for the WHO’s health literacy work, and explains how the groundwork set by the WHO provides some challenges and foundations for future health literacy research and practice.

1.Introduction

On one hand, there is nothing unique in human experience about the skills, abilities, and resources identified within the theories, definitions, conceptual frameworks, understandings, or rhetoric about health literacy. Those complex yet simple attributes of being alive and aware are – to varying degrees – present in nearly every act of being human.

On the other hand, the collection of ideas that have slowly cobbled together under the label of health literacy is proving to be among the strongest determinants of the quality and length of human life. Health literacy is, indeed, a life and death issue.

That is the core justification for more than three decades of effort in research, practice, and policy to socially construct what has been identified as ‘health literacy’ [1–4].

Such a strong attribution of life and death to health literacy is socially unfair to practitioners and proponents of literacy, plain language, education, accessibility, media literacy, public communication of science and technology, and a host of other related fields of activity. The shared set of skills, activities, ideas, and knowledge underpinning those fields clearly has a strong effect upon human longevity and productivity. Many of those relationships were well-grounded before health literacy emerged and, in fact, were a significant basis for the initial development of health literacy.

Nonetheless, health literacy has been highlighted in many ways and an ensuing movement continues to gain momentum around the world. In fact, even a casual observer would note that much of the impetus of health literacy has shifted outside the United States in recent years. Perhaps the field of health literacy is simply riding in the wake of the socially constructed importance of medicine while simultaneously critiquing the actions of the medical field – which also is perhaps the field of health literacy’s greatest benefactor and obstacle. Ideally, a collective consensus of health literacy ultimately will prove capable of building a foundation for a cohesive and significant global movement to raise the bar on the determinants of health, health outcomes, and related costs. Time will tell.

Over time, the sheer volume of scholarly publications focused on health literacy has increased steadily. While authors from the United States created most of the academic literature early on, it seems fair, accurate, and very welcome to observe that the momentum around the world has shifted. Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Asia are now active in addressing health literacy followed in level of activity by South America and Africa [5,6]. Importantly, the latter assessment refers only to the quantity of work, which is distinct from its quality.

At this point, it almost seems self-evident that policies addressing health literacy have progressed more rapidly outside than inside the United States. The authors are aware of no national effort to advance health literacy policy in the United States since the U.S. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy in 2010 [7]. Perhaps one could argue that the ongoing (at this writing) effort to create a new definition of health literacy for the Healthy People 2030 plan qualifies, but the outcomes of that effort are undetermined. By and large, however, the U.S. government and related institutions, such as the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, have remained steadfast in their use of a now nearly 20-year-old definition of health literacy and the accompanying baggage of an inaccurate and outdated definition [8].

While the current political environment in the United States does not seem conducive to further advancing health literacy within national policy - many advances in policy and practice have occurred and continue to arise at local, state, and regional levels. For example, the non-profit organization Health Literacy Media, which was founded a decade ago in Missouri, now works around the world. (www.healthliteracy.media).

In comparison, an incomplete (but hopefully somewhat representative) list of policies, policy statements, and activities addressing health literacy that have emerged around the world since 2008 includes (in no order of significance):

The Eurobarometer: Measuring health literacy across Europe

National Statement on Health Literacy in 2014 in Australia

Health literacy identified as one of ten health targets for Austria, drafted in 2012.

The Austrian Ministry of Health released the policy National Health Target No. 3: Improving Population Health Literacy, 2014

The National Plan of Health Literacy Promotion Initiatives for Chinese Citizens in 2008

Strategic Plan on Health Literacy Promotion for Chinese Citizens (2014–2020) in 2014

The New Zealand Health Strategy 2016–2026 addressing health literacy as key priority

The first and second releases of Making it Easy: A Health Literacy Action Plan for Scotland in 2014 and 2017–2025

A Vision for a Health Literate Canada: Report of the Expert Panel on Health Literacy, in 2008

The Public Health Association of British Columbia discussion paper, An Intersectoral Approach for Improving Health Literacy for Canadians in 2012

Many South American public health policies are mentioning health literacy as an important element for dealing with some health conditions, particularly NCDs. These efforts most often, albeit not without disagreement, call health literacy “alfabetización en salud” and are mostly concerned with language and comprehensibility

In Chile, health literacy is mentioned in at least three National Laws: Food Labeling (Ley 20.606 de 2012), Tobacco (Ley 20.660 de 2013) and Physical Education and Health at Schools (Decreto 614 de 2014)

In Brazil, health literacy is being considered a key-element to improve people’s health (particularly regarding NCDs) in a few national health policies from the Brazilian Ministry of Health since 2010. These include the National Policy on Health Promotion, the National Policy on Primary Health Care, and the National Policy on Food and Nutrition. Also in Brazil, the Program ‘Health at School’ mentions health literacy. This is a national inter-sectorial policy to promote positive health behaviors at public schools

Perú and Argentina are reported to mention “alfabetizatión en salud” in health policies but the authors could not find examples online

Across the continent of Africa, health literacy has perhaps made the least headway to date, but there are signs a shift. For example, a national health literacy organization in Zambia (Health Literacy Zambia) was founded by medical students.

For a more complete earlier reporting of health literacy around the world, see Health Literacy Around the World Parts 1 and 2 at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK202445/ and https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258201195_Health_Literacy_Around_the_World_Part_2_Health_Literacy_Efforts_Within_the_United_States_and_a_Global_Overview.

A recent qualitative analysis of national health literacy policies and strategies focused on six examples from Australia, Austria, China, New Zealand, Scotland, and the United States. The analysis concludes:

All of the six examples provide some response to perceived deficiencies in patient communication and engagement. The authors of this analysis do not mention other potential drivers, such as public health or disease prevention

Most of the analyzed health literacy policies present health literacy as a universal challenge; some identify high priority groups

All policies recognize the importance of health and medical professional education

Most policies recognize health systems as a needed area for improvement

There is ‘significant variability’ in linking resources to specific strategies and actions and to systems for quality and outcome monitoring

The differences in political systems and contexts is reflected in differences in health systems and approaches to health literacy within those systems

A lack of specificity within such policy documents poses a threat to the priority given to health literacy and the sustainability of actions to improve health literacy.

To advance international health literacy, the chapter highlights the role of the World Health Organization (WHO) and a series of international conferences that began in 1980s. More specifically, the chapter outlines the World Health Organization’s overarching health literacy efforts, notes the importance of health literacy within WHO’s new organization structure, briefly describes how the concept of health literacy emerged throughout a generation of the WHO’s international conferences, suggests an ethical foundation for the WHO’s health literacy work, and explains how the groundwork set by the WHO provides some challenges and foundations for future health literacy research and practice.

2.Health literacy highlights from the World Health Organization

In addition to aforementioned national efforts, the level of health literacy activity within the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations (UN) clearly is an overarching topic [9].

The WHO identified health literacy as an area of interest and needed activity much earlier than most national governments. For example, the WHO glossary definition produced in 1998 is often described as the first formal definition of health literacy [10].

The WHO Seventh Global Conference on Health Promotion in Nairobi in 2009 recognized the importance of health literacy and included explicit calls for action. Still, the topic did not seem to be a central driver of WHO efforts until the lead-up to the 9th Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Shanghai in 2016. That conference produced the Shanghai Declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/9gchp/shanghai-declaration.pdf?ua=1) While this document’s effects are still largely undetermined, it remains was one of the highest profile efforts to advance health literacy on a global stage.

Moreover, the WHO’s efforts to advance health literacy are ongoing, with a strong focus coming from the European (EURO) and South East Asia (SEARO) regional offices. For example:

Recent reporting out of the third session of the Twenty-sixth Standing Committee of the Regional Committee for Europe (SCRC), included discussion that, “since its establishment in February 2018, the WHO Action Network on Measuring Population and Organizational Health Literacy (M-POHL Network) had been very active and had garnered the involvement of 22 highly committed Member States. The Regional Office had produced a Health Evidence Network (HEN) synthesis report on existing policies and linked activities and their effectiveness for improving health literacy at national, regional and organizational levels in the Region” [11].

SEARO also has actively produced and promoted health literacy focused efforts such as the health literacy toolkit for low and middle-income countries.

All of these recent developments are to varying extents based on the foundation created by the nine WHO sponsored global health promotion conferences that have occurred during the last four decades.

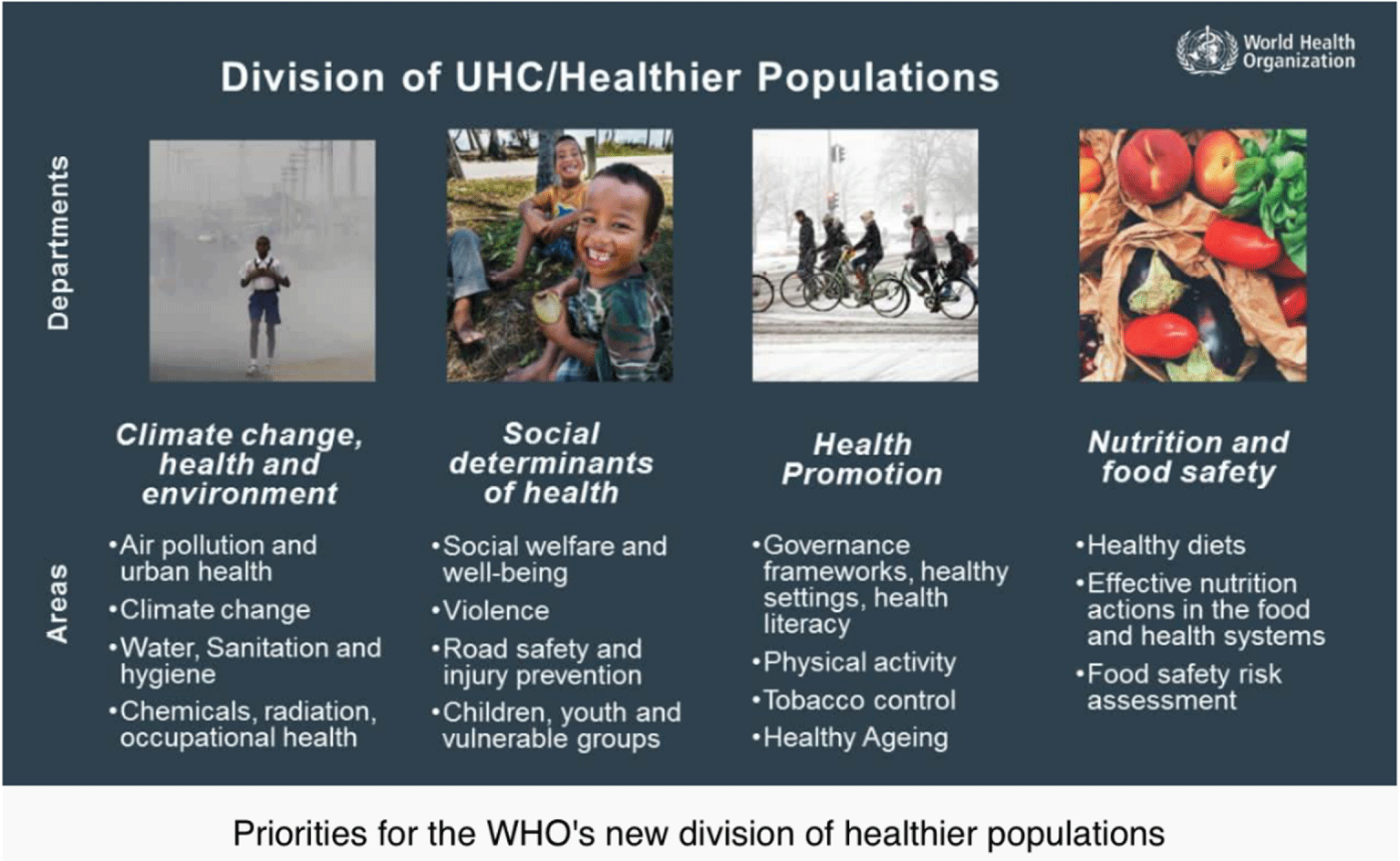

3.New World Health Organization structure

Early in 2019, Tedros Adhanom, WHO’s Director-General, announced a new organizational structure for WHO headquarters’ staff [12–14].

In relation to its health literacy efforts, the WHO’s new organizational structure creates a new division of Healthier Populations. This new division is proposed to function as cross-cutting all WHO activities, divisions, departments, and regional offices.

The departments within this new division of Healthier Populations are:

Climate change, health and environment

Social determinants of health

Health promotion

Nutrition and food safety

The department of health promotion is described as focusing upon:

Governance frameworks, healthy settings, health literacy

Physical activity

Tobacco control

Healthy aging

This relatively unprecedented new pillar of WHO operations was the focus of a technical briefing at the 72nd session of the World Health Assembly in Geneva [15]. The Assistant Director-General for this new division will be Dr. Naoko Yamamoto, who was most recently WHO’s Assistant Director-General for Universal Health Coverage and Health Systems.

As one participant in the technical briefing at the 72nd World Health Assembly announcing the new Healthier Populations effort said, “Health is created where people live, love, work and play, and that means that we need to structure environments in a way that they are healthy and that relates to people’s wellbeing, not a narrow understanding of health”.

The development of an office focused on health promotion within the new division on Healthier Populations can only be a promising sign for further developments and applications within the field of health literacy. Clearly, the WHO staff who will advance the new effort (and can trace its roots back to the earliest of the global conferences on health promotion), provide a reservoir of experienced leadership. While the WHO staff will face challenges to fund initiatives from within WHO and from external funders (and they need to demonstrate outcomes in a rigorous evidence-based manner), the overall effort promises to develop and test new approaches to advance health literacy around the world.

4.Global health promotion conferences: A brief health literacy review

At this point, any causality of change in the world’s health simply cannot be attributed to the series of global health promotion conferences or the policy statements the latter conferences have produced. While it could be designed and put in place, there is currently no existing, efficient, or cost-effective evaluation of the effects of the large and ongoing global efforts to promote health and well-being. Certainly, the fields of health promotion and health literacy have grown in parallel with steady improvements in many, but not all, health and health-related indicators of global health and wellbeing. For example, while key global indicators such as the literacy rate, life expectancy at birth, and poverty have improved since 1980, the percent of deaths caused by non-communicable (chronic) disease has steadily increased. One would hope that efforts at health promotion would largely focus on prevention of disease.

What is certain is the series of conferences, held on average about every four years, furthered a very public and large stage for issues and ideas regarding global health and wellbeing as well as for the proponents of ensuing issues and ideas. In chronological order, these conferences, the key documents they produced, and any mention of health literacy in those documents are provided:

1st Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Ottawa, Canada in 1986 (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/)

Produced the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion which does not use the phrase health literacy.

2nd Global Conference on Health Promotion in Adelaide, Australia in 1988 (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/adelaide/en/)

Produced the Adelaide Recommendations on Healthy Public Policy which does not use the phrase health literacy.

3rd Global Conference on Health Promotion in Sundsvall, Sweden in 1991 (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/sundsvall/en/) Sundsvall 1991

Produced the Sundsvall Statement on Supportive Environments for Health which does not use the phrase health literacy.

4th Global Conference on Health Promotion in Jakarta, Indonesia in 1977 (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/jakarta/declaration/en/)

Produced the Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century which does not use the phrase health literacy.

• 5th Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Mexico City, Mexico in 2000 (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/mexico/en/hpr_mexico_plans_action.pdf)

Produced the Framework for Countrywide Plans of Action in Health Promotion which has one mention of health literacy is included within the section on evaluation of health promotion efforts. This document states: “Health promotion outcome measures can include: health literacy measures, including health-related knowledge, attitudes, motivation, behavioural intentions, personal skills, and self-efficacy”

• 6th Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Bangkok, Thailand in 2005 (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/6gchp/hpr_050829_%20BCHP.pdf?ua=1)

The Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World provides one mention of health literacy, which states all sectors and settings should: “build capacity for policy development, leadership, health promotion practice, knowledge transfer and research, and health literacy”.

• 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Nariobi, Kenya in 2009 (http://www.ngos4healthpromotion.net/wordpressa4hp/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Nairobi_Call_to_Action_Nov09.pdf)

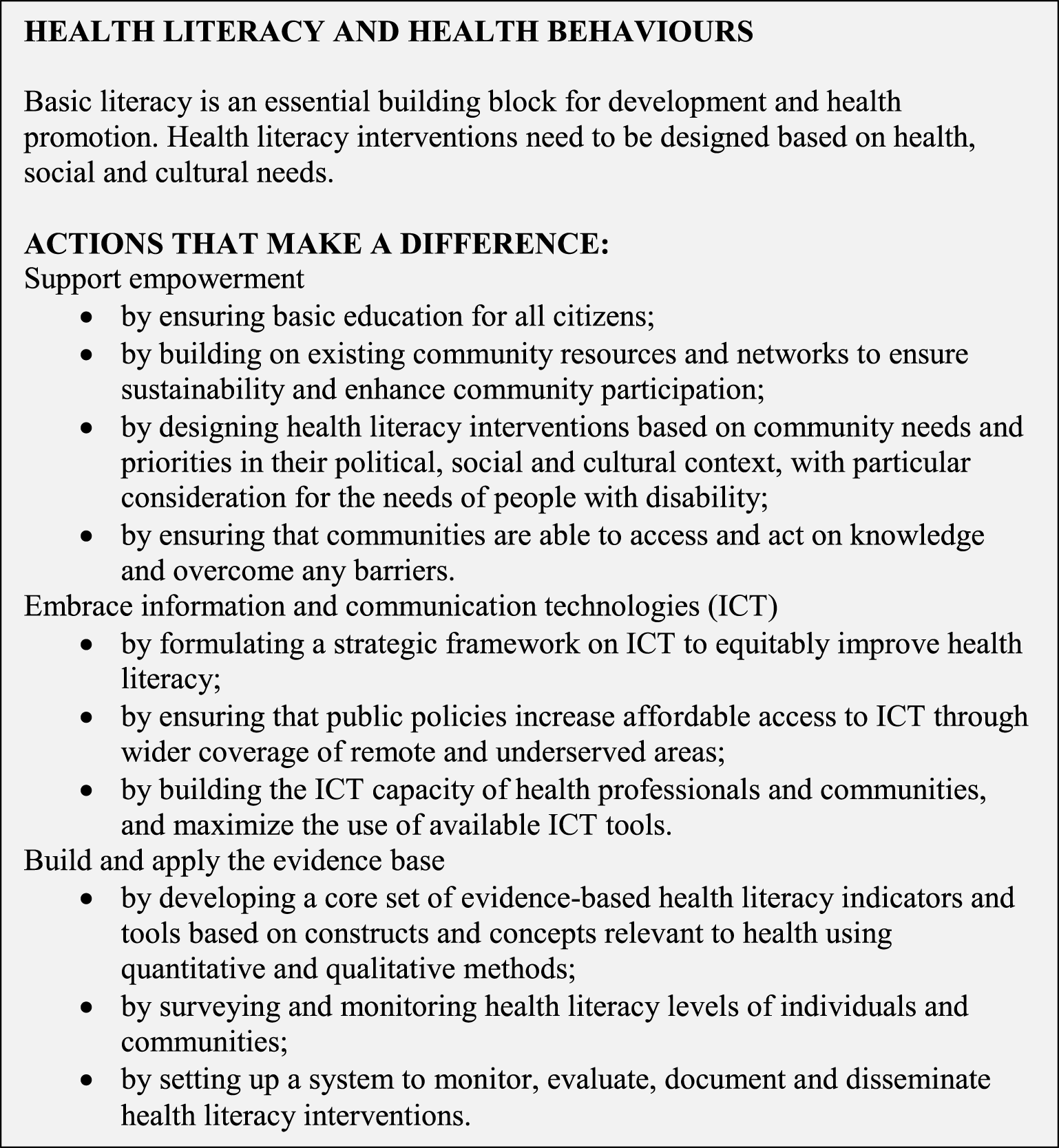

In the Nairobi Call to Action for Closing the Implementation Gap in Health Promotion 2009, one of the five key strategies and actions to reduce health inequities and poverty and enhance health and quality of life focused on initiatives to improve health literacy and health behaviors. The key areas highlighted for health literacy were to: support empowerment; enhance information and communication technologies; and build and apply health literacy’s evidence base.

• 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Helsinki, Finland in 2013 (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112636/9789241506908_eng.pdf;jsessionid=B1B1A39C07F93312AAF7CAA105BAC70B?sequence=1)

The Helsinki Statement on Health in all Policies mentions health literacy one time, in a call for nations to: “Include communities, social movements and civil society in the development, implementation and monitoring of Health in All Policies, building health literacy in the population”.

9th Global Conference on Health Promotion held in Shanghai, China in 2016 (https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/9gchp/shanghai-declaration.pdf?ua=1)

The Shanghai Declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at one page in length is by far the shortest within the history of documents produced by global conferences on health promotion. Given that, this document mentions health literacy seven times. See below for further discussion of this document.

As the information in Table 1 indicates, the exact phrase ‘health literacy’ has not been consistently featured in the documents produced by the series of global health promotion conferences that began in Ottawa in 1984. ‘Health literacy’ first appeared within the Framework for Countrywide Plans of Action in Health Promotion generated in Mexico City in 2000. While the earlier documents produced by these global health promotion conferences may not have used the exact phrase ‘health literacy’, there are instances throughout where the spirit of health literacy (the idea of an equitable approach to health, a focus on prevention, and a larger integrative approach to health and wellbeing) are evident.

Table 1

Quick analysis of the core documents produced by each Global Health Promotion Conference (bold faced font indicates best from a health literacy perspective)

| Document name | City | Nation | Year | Number of letter-sized pages | Number of words | Number of times the phrase ‘health literacy’ appears | Use of ‘health literacy’ per word count | Reading level using SMOG online tool | Readability consensus - Grade level |

| Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion | Ottawa | Canada | 1986 | 5 | 1,489 | 0 | – | 13.8 | 16 |

| Adelaide Recommendations on Healthy Public Policy | Adelaide | Australia | 1988 | 6 | 2,378 | 0 | – | 13.5 | 15 |

| Sundsvall Statement on Supportive Environments for Health | Sundsvall | Sweden | 1991 | 5 | 2,112 | 0 | – | 13.6 | 15 |

| Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century | Jakarta | Indonesia | 1997 | NA as is available only in online format1 | 1,754 | 0 | – | 14.1 | 16 |

| Framework for Countrywide Plans of Action in Health Promotion | Mexico City | Mexico | 2000 | 8 | 3,163 | 1 | 1:3,163 | 13.2 | 15 |

| Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World | Bangkok | Thailand | 2005 | 6 | 1,535 | 1 | 1:1,535 | 14.5 | 17 |

| Nairobi Call to Action for Closing the Implementation Gap in Health Promotion | Nairobi | Kenya | 2009 | 7 (not provided online by WHO) | 2,725 | 8 | 1:341 | 19.5 | 23 |

| Helsinki Statement on Health in all Policies | Helsinki | Finland | 2013 | 2 | 1,071 | 1 | 1:1,071 | 14.8 | 16 |

| Shanghai Declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Shanghai | China | 2016 | 1 | 1,041 | 7 | 1:149 | 15.5 | 17 |

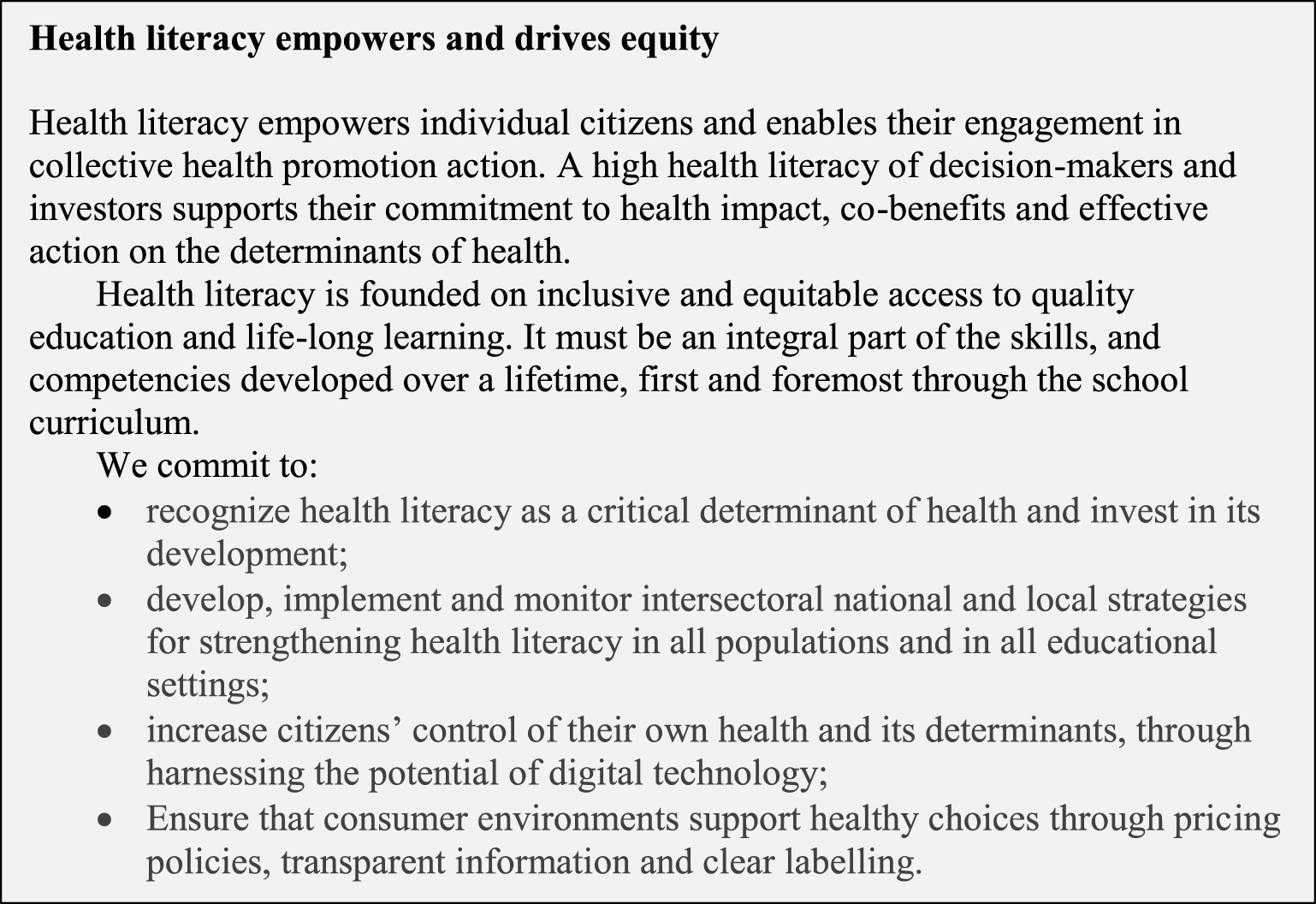

Meanwhile, the term ‘health literacy’ has appeared the most in documents produced by two of the three most recent conferences - eight times from Nairobi in 2009 and seven from Shanghai in 2016. The use of health literacy is clustered within specific sections of both documents. In the Nairobi Call to Action, the section is titled “Health literacy and health behaviours” and in the Shanghai Declaration the section is titled “Health literacy empowers and drives equity”.

Uniquely by comparison, “The programme of the Shanghai Conference revolved around three thematic ‘pillars’: good governance; healthy cities; and health literacy” [16].

The text of those sections in each document that focuses on health literacy follows in Figs 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Health literacy focused section of the Shanghai Declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Comparing the content of both sections of each document focused on health literacy (using two coders who agreed on the final coding displayed below), the authors suggest both documents provide a justification for addressing health literacy, a series of action steps that are proposed within each document, and brief lists of possible outcomes from health literacy actions. See Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Both documents, in different wording, generally agree that the links between health literacy, basic literacy, education, and lifelong learning provide a justification to address health literacy at a high level within an international health policy document. The documents envision these linkages as underpinning advances in both individual and collective global health promotion.

This direct description in both documents of what some have referred to as the ‘two-sided’ nature of health literacy by addressing collective - and thus systematic - action suggests a revision of previous definitions, such as that initially proposed by Ratzan & Parker almost 20 years ago now, that is often used as the definition of health literacy by U.S. governmental agencies [17].

Although both documents recommend numerous action steps, each clearly has different foci in this regard. While endorsing health literacy, the Shanghai Declaration does not contain the same level of detail as the Nairobi Call to Action. While the Shanghai Declaration calls for both local and national strategies to be developed - they are left undefined. In contrast, the Nairobi Call to Action lists several fairly specific action steps that are not mentioned in the later Shanghai document.

The Nairobi Call to Action also includes a section that explicitly recommends its proposed efforts are evaluated and evidence-based. While this could be read as implied in the Shanghai Declaration, it is not explicitly stated.

Fig. 2.

Health literacy focused section of the Nairobi Call to Action for Closing the Implementation Gap in Health Promotion.

Table 2

Comparing justifications for addressing health literacy in the Shanghai Declaration and the Nairobi Call to Action

| Justification for addressing health literacy | Shanghai Declaration | Nairobi Call to Action |

| Links to basic literacy, education, and lifelong learning empowers individual citizens and enables their engagement in collective health promotion action | x | x |

Table 3

Comparing actions steps suggested for health literacy in the Shanghai Declaration and the Nairobi Call to Action

| Action steps suggested | Shanghai Declaration | Nairobi Call to Action |

| Recognize and invest in development and individual control of health and health literacy as a determinant of health | x | x |

| Local strategies – undefined | x | |

| National strategies – undefined | x | |

| Use of ICT/ digital technology for consumers | x | x |

| Improve ICT/digital technology use from health professionals | x | |

| Improve ICT/digital technology in remote/ underserved areas | x | |

| Improve ‘consumer environments’ by using markets to supply healthier choices (e.g. pricing, labeling, etc.) | x | |

| Design health literacy interventions based on community needs, priorities, and contexts to enhance participation | x | |

| Consider needs of people with disability | x | |

| Ensure access to knowledge and basic education | x | |

| Ensure use (act on) of knowledge | x | |

| Develop core set of evidence-based health literacy indicators | x | |

| Develop core set of evidence-based health literacy tools | x | |

| Survey and monitor health literacy levels of individuals and communities | x | |

| Set up system(s) to monitor, evaluate, document and disseminate health literacy interventions. | x | x |

Table 4

Comparing outcomes suggested for health literacy in the Shanghai Declaration and the Nairobi Call to Action

| Outcomes | Shanghai Declaration | Nairobi Call to Action |

| Strengthens commitment to health | x | |

| Increases equity | x | |

| Empowers individuals | x | x |

| Increases engagement in collective health promotion action | x | |

| Improves development (international) | x | |

| Improves outcomes of health promotion efforts | x | x |

| Improves sustainability of health promotion outcomes | x | |

| Creates consumer environments that support healthy choices | x |

Overall, the documents produced by both the Nairobi and Shanghai conferences collectively advance health literacy. As aforementioned, each contains strengths and weaknesses. Hopefully, policymakers and practitioners will utilize them collectively rather than individually as the foundations of future efforts. To reinforce a conclusion from the aforementioned policy document analysis, the lack of specific detail creates shorter, easier-to-read and share documents but their generalities may not persuade readers and policymakers to give priority to health literacy - or generate the vigor and actions needed to foster sustainable efforts to improve health literacy. Further negative outcomes also could stem from a lack of rigorous, valid, and reliable evaluation of recommended efforts over the long-term.

5.Looking forward

In retrospect, it seems too easy to find evidence that health literacy’s initial development was dominated by siloed efforts internationally - as practitioners and institutions struggled to define and claim territory and importance. The latter occurred most frequently in the guise of definitions, measurement, and interventions.

Yet looking forward, there is hope on the horizon. The emergence of health literacy as an evidence-based approach to preventing poor health and improving public health on the international stage is replacing the U.S.-based approach that primarily focused on introducing health literacy within medical care after people become ill.

As we move forward - hopefully as a collectively collaborating and cooperating field of research, practice, and policy - the authors suggest the field especially embrace a strong ethical foundation and approach. In other contexts, the authors have suggested ‘the 5E approach’ to health literacy. In brief, this approach suggests that ethics in health literacy is a function of addressing effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and evaluation. In short:

The authors propose that health literacy research, programs, and policy should focus on ethics. Further, the authors suggest an ethical approach necessitates health literacy should be conducted and assessed as a continuous measurement. The latter approach would challenge past binary classification systems (e.g. low to high health literacy) or sets of poorly-labeled hierarchical health literacy levels that frequently dominated past measurement approaches.

In making this suggestion, the authors’ logic is simple. To be ethical in health literacy, you must be effective, efficient, and equitable. To demonstrate health literacy efforts are effective, efficient, and equitable, researchers and practitioners need to evaluate. Therefore, to evaluate is to be ethical.

The authors operationally define the health literacy components as:

Effectiveness - The health literacy effort has proven effects on key indicators; the authors highly encourage going beyond self-report measures and including objective health metrics

Efficient - The health literacy effort produces change at an equivalent or better scale per amount spent compared to other intervention types

Equity - The health literacy effort focuses on reducing or eliminating inequities in health and well-being - access to health as a resource for living is key in this regard

Evaluation - The health literacy effort is rigorously evaluated to build health literacy’s evidence base in order to advance the field and assure the other components within the proposed equation have been addressed.

The authors propose such an approach is the best and most effective way to continue to raise the bar on health literacy. We strongly suggest organizations, such as the World Health Organization, make this or a similar approach central to all health literacy efforts. The authors’ experience indicates the latter is an effective way to develop, test, and implement evidence-based and effective new solutions to the challenges of health literacy in public health and in public systems that can impact health and wellbeing.

Further, the authors strongly suggest it is important to highlight the continued need to expand the conceptualization of health literacy beyond medical care. We live in a world marked by threats to individual and public health that arise from complex global, regional, and local sources ranging from food production systems to climate change, from educational systems to the design of cities and transportation, from individual preferences and behaviors to cultural beliefs and practices.

In this context, the authors urge practitioners and researchers to continue to blur the traditional distinctions between health and environment as they continue their work to advance health literacy. A person cannot be healthy in an unhealthy environment just as unhealthy behaviors produce an unhealthy environment. As a holistic approach to such issues emerges within health literacy, the authors applaud and urge its continuation.

Finally, the authors maintain if there is a golden rule to health literacy, it is to engage with people and communities early and often. This naturally leads to an approach grounded in integrative health. Embracing an integrative approach to health requires that health literacy address the entire lives of people, not just their medical condition or disease. By doing so, the focus of activities increasingly become health prevention rather than medical care. The ensuing logical progression is how health literacy helps create a world with a healthy and sustainable environment populated by empowered and engaged people living a life of health and wellbeing. To reach that admittedly normative goal - albeit required in so many ways – the authors recommend that efforts continue to build on the most recently produced Shanghai Charter through:

Informed advocacy for health literacy at all levels

Development of more and better practical actions and tools that address health literacy. Such developments in health literacy must be disseminated freely

A sustained and active focus on helping the world become healthier and happier with health literacy

In closing, the authors would be derelict in our responsibility if we did not highlight the unfortunate truth that the level of health literacy activity is often the lowest in areas of the world where the need is the greatest. Health literacy efforts should not only be available to those who have socio-economics means, the best practices of health literacy should be available to all. While the authors encourage efforts to counter the historical reality of unequal access to health and wellbeing, we caution that great care must be taken so health literacy does not become yet another tool of cultural hegemony or colonization through ideas or economic servitude.

In such efforts, health literacy is needed in all contexts of human interactions and life - not just medical systems. Doing so, in our opinion, will in the long run create:

Better health

Greater social cohesion

Effective communication across diverse populations and ideas

Lower costs of producing health and medical care

More resources to allocate toward living and enjoying life versus staying healthy

Shift in goals from being healthy to using health to advance global wellbeing

Ultimately, the authors hope our work and the work of everyone engaged in health literacy always keeps in mind the core idea of the first global health promotion conference that produced the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion - health is a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living.

References

[1] | C. Zarcadoolas, A. Pleasant and D. Greer, Advancing Health Literacy: A Framework for Understanding and Action. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA, (2006) . |

[2] | A. Pleasant and J. Mckinney, Coming to consensus on health literacy measurement: Report on an online discussion and consensus gauging process, Nurs Outlook 59: (2) ((2011) ), 95–106. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.006. |

[3] | A. Pleasant, J. McKinney and R.V. Rikard, Health literacy measurement: A proposed research agenda, J Health Commun 16: (Supplement 3) ((2011) ), 11–21. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011. |

[4] | J.T. Huber, R.M. Shapiro and M.L. Gillaspy, Top down versus bottom up: The social construction of the health literacy movement, Libr Q. 82: (4) ((2012) ), 429–51. doi:10.1086/667438. |

[5] | A. Pleasant, Health Literacy Around the World: Part 2 Health Literacy Within the United States and a Global Overview. Institute of Medicine, Washington, D.C., (2013) . |

[6] | A. Pleasant, Health Literacy Around the World: Part 1 Health Literacy Efforts Outside of the United States. Institute of Medicine, Washington, D.C., (2013) . |

[7] | National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Washington, DC, (2010) . |

[8] | A. Pleasant, R.E. Rudd, C. O’Leary, M.K. Paasche-Orlow, M.P. Allen, W. Alvarado-Little Considerations for a New Definition of Health Literacy. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC, (2016) , doi:10.31478/201604a. |

[9] | D. McDaid, Investing in Health Literacy, What do We Know About the Co-Benefits to the Education Sector of Actions Targeted at Children and Young People?. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark, (2016) . |

[10] | D. Nutbeam, Heath Promotion Glossary. World Health Organization, (1998) . |

[11] | Report of the Third Session. World Health Organization Twenty-sixth Standing Committee of the Regional Committee for Europe, Europe WHOROf, Copenhagen, Denmark, (2019) , Report No.: EUR/SC26(3)/REP Contract No.: EUR/SC26(3)/REP. |

[12] | D.T.A. Ghebreyesus, Transforming for Impact: Speech of the WHO Director-General [Web Site]. World Health Organization, (2019) , https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/transforming-for-impact. Retrieved Aug. 18, 2019. |

[13] | J.L. Ravelo, New WHO structure revealed: devex.com, 2019. https://www.devex.com/news/new-who-structure-revealed-94420. Retrieved Aug. 18, 2019. |

[14] | A. Coopes, Climate change, social determinants focus for WHO’s new healthier populations pillar: Croakey.org, 2019. https://croakey.org/climate-change-social-determinants-focus-for-whos-new-healthier-populations-pillar/. Retrieved Aug. 18, 2019. |

[15] | World Health Organization. Towards healthier population: a new vision - technical briefing at the 72nd World Health Asssemblly World Health Organization, 2019. p. 43:03. |

[16] | Promoting Health in the SDGs. Report on the 9th Global Conference for Health Promotion, Shanghai, China, 21–24 November 2016: All for Health, Health for All. World Health Organization, Geneva, (2017) , Contract No.: WHO/NMH/PND/17.5. |

[17] | S. Ratzan and R. Parker, Introduction. in: National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD, (2000) . |