Introduction to the special issue ‘Towards a Multi-Level Understanding of Agile in Government: Macro, Meso and Micro Perspectives’

Abstract

As public organizations increasingly adopt agile practices, understanding their opportunities, challenges, and transformative potentials is important. This article introduces the special issue on ‘The Future of Agile in Public Service Organizations: Macro, Meso and Micro Perspectives’ and explores the evolving landscape of agile in public service, drawing from diverse scholarly perspectives. To that end, we discuss various definitions of agile in the context of government and outline the potential benefits and drawbacks of the concept. We then delve into the macro-level characteristics and impacts of agile on institutions and society, its meso-level implications regarding organizational structures, processes, and outcomes, and micro-level determinants and effects on managers, employees, and teams. Referring to theoretical streams building the basis for agile on these different analytical levels, we build a conceptual framework of multi-level agile government. We introduce the six research studies and a book review included in this special issue and position them within this framework to highlight their contributions to understanding agile at each of the three levels.

1.Introduction

Over the past twenty years, agile management methods have become standard practice in software development and IT. The ‘agile manifesto’ (Beck et al., 2001) was an important starting point for this development, as it addressed the shortcomings of the previously dominant ‘waterfall’ approach in project management and software development. This agile wave also arrived in public sector practice, mainly aiming for a more responsive, flexible, learning-oriented and collaborative approach to government (Greve et al., 2020; Mergel et al., 2018).

Traditional approaches to planning and project management focus on standardized processes and rely on the assumption that requirements will not change during planning and development of a product or service, allowing for a sequential approach in which development is only started after planning is completed (Simonofski et al., 2018). However, in reality, the political, societal and economic environment tends to evolve, meaning that requirements also change over time, leading to results that are already outdated by the time they are released and used. Thus, the waterfall approach can lead to catastrophic project failures, dysfunctional processes and economic waste (Mergel et al., 2021). Agile, in contrast, adopts a more flexible approach and uses less detailed planning, reflective learning, shorter development cycles, intensive collaboration, and continuous testing with clients that allows for fixes to be implemented before a product or service is released (Beck et al., 2001; Mergel, 2016).

The notion of ‘agile government’ goes beyond software design and IT, meaning that agile practices can also be used in other types of projects and their management, process redesign, and to solve other complex challenges (Mergel et al., 2018). This development is illustrated by the increasing number of government organizations that have begun to adopt principles, practices, and tools subsumed under the term ‘agile’.

However, although we observe an increasing use of agile methods in governmental practice, the literature analysing determinants and impacts of agile government and related theoretical reflections is still developing. Perhaps most pressingly, the term agile is often only poorly defined and conceptualized or used only as a buzzword in what could be described as faux-agile approaches (Mergel, 2023). McBride et al. (2022) even argue that “while agility can represent a useful paradigm in some contexts, it is often applied inappropriately in the governmental context due to a lack of understanding about what ‘agile’ is, and what it is not” (p. 21). Moreover, certain practitioners and scholars suspect that agile may be just another management fad, and only more empirical research can unveil whether it is substantially different and more sustainable and successful than previous approaches.

Therefore, the aims of this special issue are twofold. First, it sets out to strengthen the conceptual and theoretical foundations for future research on agile government. This is done both in the articles in this special issue as well as in this introductory article in which we present an extensive discussion of different definitions of agile and develop a multi-level framework to integrate these differing understandings by conceptualizing agile government on different analytical levels (macro, meso and micro). With that, we heed the calls for further theorisation about differences between engaging in agile practices on an individual level and within an organization and the organization being an agile entity in itself (Baxter et al., 2023; McBride et al., 2022). Second, this special issue strives to add empirical evidence and practical implications to help with the implementation of agile in the public sector. This is mostly done in the six research articles within this special issue.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the next section, we discuss the conceptual boundaries and various definitions of agile. In section three, we highlight the specificities of agile government on the macro, meso, and micro levels. Lastly, we introduce the research articles of this special issue and draw some conclusions on future research.

2.Towards conceptual clarity

Clearly defining the boundaries of a concept is of key importance for a field of research to make progress (Goertz, 2020). Thereby, good concept formation should consider eight factors: familiarity, resonance, parsimony, coherence, differentiation, depth, theoretical utility, and field utility (Gerring, 1999). Thus, answering the question of ‘what is agile’ is crucial also for the evolving body of literature on agile government as well as for this special issue, which is why we start this introductory article with a discussion of the ontology of agile in the public sector context. Developing clear definitions also helps to overcome the status of a buzzword, that some authors share about the concept of agile government (Madsen, 2020). While the term “agile government” may sometimes be used as a buzzword or to signal development and innovation, e.g. by consultants but also public agencies themselves, the principles and practices it encompasses have real-world applications and may lead to tangible improvements in government effectiveness and citizen satisfaction. While agile is clearly a management fashion (as also reflected by Kühler et al. in this special issue), this does not mean that agile government is a concept without substance. This chapter therefore discusses the substance and quality of definitions of agile government.

Broadly speaking, agile in government can be understood as a dynamic and adaptive approach to governance that draws inspiration from the principles of agile methodologies commonly employed in software development. It is characterized by flexibility, responsiveness, and a collaborative mindset that allows for swift adjustments to changing circumstances (Li et al., 2023; Mergel et al., 2018). Agile is sometimes viewed as a central element of digital government (Fishenden & Thompson, 2013) and of the broader concept of adaptive governance (Janssen & van der Voort, 2016; Soe & Drechsler, 2018). In the public sector literature, there is often a very close alignment between digital transformation and agile: “ICT adds public value via agile methods” (Soe & Drechsler, 2018).

If we go back to the agile manifesto for software development, there are four core values that guide the agile approach: individuals and interactions are prioritized over processes and tools, functioning software over comprehensive documentation, customer collaboration over contract negotiation, and, perhaps most importantly, responding to change over following a plan (Beck et al., 2001). Based on this, there are twelve principles derived from the abovementioned values in the agile manifesto, touching upon aspects such as customer centricity, continuous delivery of software, openness to changing requirements, collaboration between business and IT, assigning motivated employees to the project, and trusting them, extensive communication, and simplicity, self-organization, and self-reflective learning (Beck et al., 2001). Both the values and principles in the agile manifesto are universal enough to be applied to contexts other than software development, such as developing new public services or solutions to public problems. However, while the agile manifesto does help to better understand what agile is about (and not about), it does not constitute an academic definition of agile.

In the field of information systems, multiple definitions of agile have subsequently been developed, including “the software team’s capability to efficiently and effectively respond to and incorporate user requirement changes during the project life cycle” (Lee & Xia, 2010, p. 90), “to rapidly or inherently create change, proactively or reactively embrace change, and learn from change while contributing to perceived customer value (economy, quality, and simplicity), through its collective components and relationships with its environment” (Conboy, 2009, p. 340), and “both the ability to adapt to different changes and to refine and fine-tune development processes as needed” (Dingsøyr et al., 2012, p. 1214; based on Henderson-Sellers & Serour, 2005).

Focusing on the public sector, Mergel et al. (2021, p. 1) picked up on the central notion of the manifesto that agile is about responding and adapting to change, providing a government-specific definition of agile: “responding to changing public needs in an efficient way” (2021, p. 1). With this elegant and short definition, these authors highlight that agile could be a promising approach for many public organizations in times of rising citizen expectations and problem complexity. It constitutes a definition at the macro level, focusing on addressing public or societal needs. However, while this definition satisfies the criteria of familiarity, resonance, and parsimony, it is less clear about coherence, differentiation to similar concepts such as adaptive governance, depth, as well as theoretical and field utility (Gerring, 1999).

Even more recently, two more refined definitions of agile that specifically consider the public sector context were put forward. Mergel (2023, p. 1) argues that “agile refers to a work management ideology with a set of productivity frameworks that support continuous and iterative progress on work tasks by reviewing one’s hypotheses, working in a human-centric way, and encouraging evidence-based learning”. This definition is focused on the meso-level, describing key changes that agile introduces to the inner workings of an organization, and centred on processes. While this definition is less parsimonious than the previous definition, it does well on the other criteria proposed by Gerring (1999), particularly on depth, differentiation, coherence, and field utility.

In contrast, Neumann et al. (2024, p. 17) define agile as “a form of governance innovation consisting of organization-specific mixes of cultural, structural, and procedural adaptations geared towards making public organizations more flexible in changing environments, ultimately pursuing the goal of increasing efficiency, effectiveness, and user satisfaction”. As such, this definition focuses more on the macro level, mentioning implications of agile that go beyond the organizational boundaries and that are relevant to external stakeholder groups. More specifically, it centres on the intended outcomes of agile in government and highlights that agile challenges existing governance modes in public organizations. Similarly to the last definition, it is not particularly parsimonious, but it has its strengths in the areas of familiarity, depth, coherence, and theoretical utility.

In conclusion, we believe that both of the most recent definitions have their merit and contribute to delimiting the conceptual space of agile in government, which should enhance conceptual coherence both in future research and in practice. However, they only cover the macro and meso levels of agile, whereas a micro-level definition is so far missing. This may be explained by the focus of agile on organizational productivity and adaptability vis-à-vis external changes, whereas agile is not something that can exist purely at the micro-level (e.g., done just by an individual) – although it certainly may have effects on it and be also determined by micro-level factors. However, this diversity in definitions already shows the need to relate definitions of agile on different levels with each other and to be more explicit about their connections.

3.Macro, meso, micro – agile government on different levels of analysis

So far agile government has mainly been studied and conceptualized from a macro (e.g. Greve et al., 2020) and meso (e.g. Atobishi et al., 2024; Walsh et al., 2002) level perspective, which follows the idea of agile government as a procedural and project management approach (meso) relying on environmental influences and more transformative changes in the public sector (macro). However, agile government is also affected by micro-level determinants and comes with micro-level implications pointing to individual agile practices as well as individual attitudes and motivation regarding agile processes and structures as well as the role of leaders (e.g. Lediju, 2016). Dwi Harfianto et al. (2022) show that well in a recent systematic literature review, where they cluster challenges of agile transformations in bureaucratic organizations into the environmental context (macro, e.g. governmental regulations), the organizational context (meso, e.g., internal policies and organizational structure), the individual context (micro, e.g., individual competence or interpersonal conflict) and the technology context (covering multiple levels of analysis, depending on whether the focus is on organizational infrastructure, general policies for documentation or development activities). Similarly, McBride et al. (2022) point out that the discussion about agile governance (macro) often overlooks the relationship of general agile government with organizational structure and stability (meso) and inherently contradicting public values (innovation and flexibility vs. long-term stable provision of public goods, predictability, equity) and related agile practices (micro).

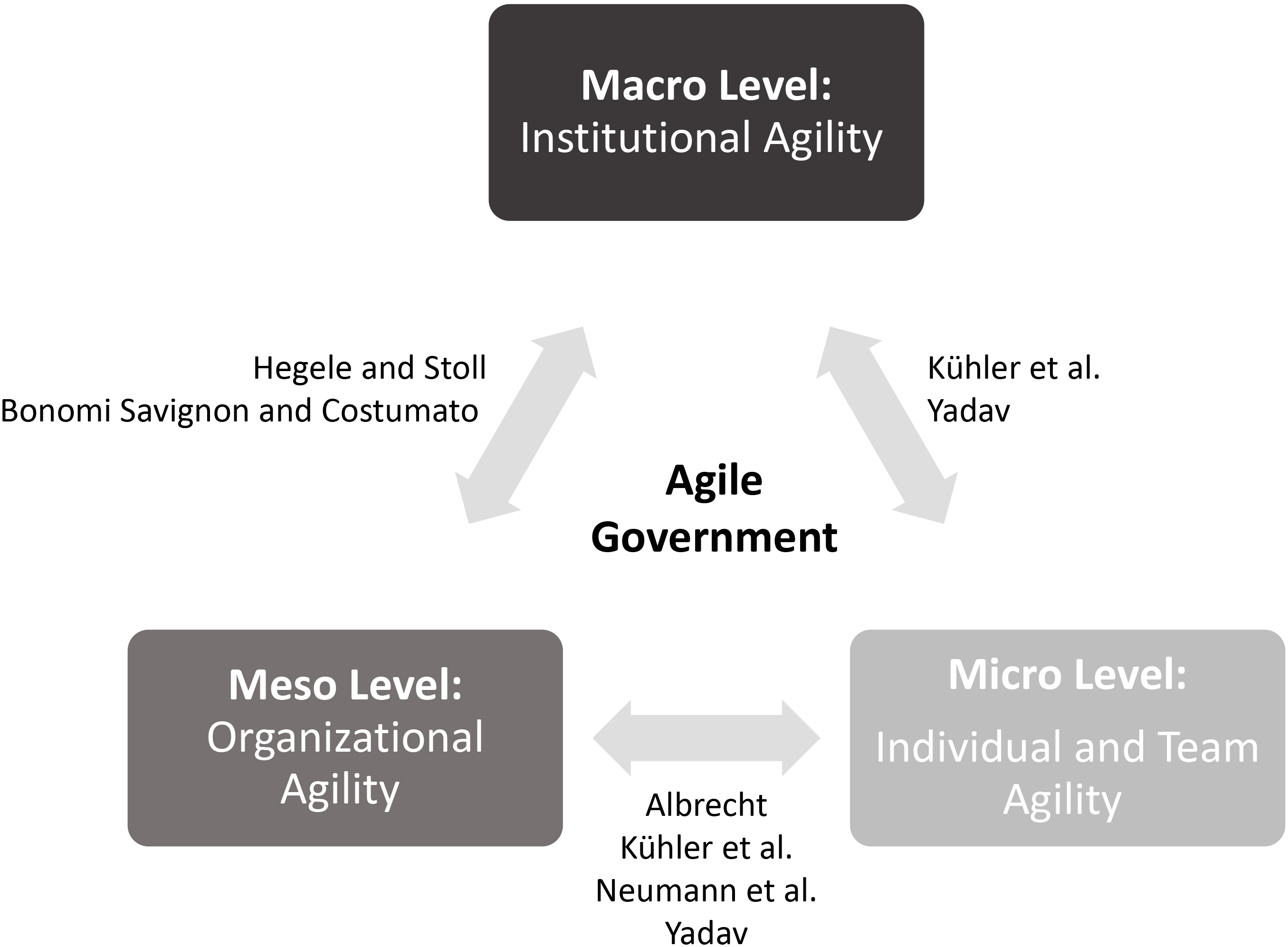

The following section first describes the notion of agile on these different analytical levels and develops a conceptual framework of agile government that shows the interdependence between these levels. Agile is sometimes coined as “old wine in new bottles” (Kühl, 2023; McBride et al., 2022) and indeed the core ideas all trace back to classic organization and management theories. To underline these traces, we also point to the theoretical and conceptual heritage that agile government builds upon for each analytical level, we also point to the theoretical and conceptual heritage that agile government builds upon. The articles belonging to this special issue are then positioned within this framework, showing that none of them clearly just analyses one of these levels, but that they are all positioned at the crossroads between different analytical levels or even touching all of them.

When agile government is defined as a multi-level concept, it is not only important to separate these analytical levels and to analyse what agile government means from these different perspectives, but to also focus on the interdependence and reciprocal influences between macro, meso, and micro levels in agile government. With that, we bring Mergel et al.’s (2018) idea of a holistic approach to agile government across different organizational levels to the next level, by not only having an organizational holistic perspective but also in terms of analytical levels and respective focus points in research. In that we also follow advice by Jilke et al. (2019) and Roberts (2018) to reflect more explicit on levels of analysis used in empirical public administration studies and to reflect on multi-level implications.

As agile management evolved from a focus on software development and technology, also the practical implementation in government is often connected to technology and digital change (see e.g., Dittrich et al. (2005) on Denmark, Mantovani Fontana and Marczak (2020) on Brazil, Li et al. (2023) on China, Mergel (2019) on several digital service teams worldwide). The articles that are part of this special issue underline that. For example, (Kühler et al.) find that narratives related to agile government are inherently linked to digital organizations and new work. Yadav analyses a public sector organization dealing with overall digital change. Hegele and Stoll find that what they define as “doing agile” is often related to a position in the IT department of a public organization and what they define as “being agile” goes together with the introduction of digital change in general. Hence, we also model technology to serve as a linchpin in the multi-level agile government framework, driving transformative changes in governance structures, decision-making processes, and citizen engagement strategies.

3.1Macro level: Institutional agility

Drawing from institutional theory (e.g., population ecology Aldrich, 2008; Baum & Amburgey, 2017; or neo-institutionalism DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer et al., 1985), agile on the macro level focuses on the overarching structures, regulations and environmental influences that shape governmental behaviour. Institutional agility involves the adaptation of formal rules and regulations to foster a responsive government. This level considers factors such as legal frameworks, political structures, and global governance trends that influence the agility of the entire public sector. Baxter at al. (2023) for example, analyse the implementation of agile practices within an IT program in the UK defence sector applying institutional logics (Friedland, 2017) to better understand complex relationships between stakeholders in this field and make general tensions in terms of regulation, culture and governance visible. Chatfield and Reddick (2018) take the perspective of the costumer and analyse with the theoretical lens of dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997; Vogel & Güttel, 2013) how sensing citizens needs and responding to them takes place by studying the case of a US city administration, their non-emergency police services (so-called 311 services) and the use of big data analytics. They find that big data analytics is used effectively, but in a localized and siloed way. A systemic implementation and assimilation of the idea of agile is missing so far and they identify several mechanisms to arrive at this macro-level agility: more empowerment of public agents to self-organize (pointing to micro-level implications), business-process change (pointing to the meso-level) and stronger use of networks of citizens (pointing to environmental macro-level factors). Hence, although not making that very explicit in their study, Chatfield and Reddick (2018) capture a holistic understanding of agile.

Hence, while an agile public sector on the macro level is mainly analysed from the perspective of environmental influence, also bottom-up determinants stemming from the meso- and micro-level affect institutional agility. On the meso-level especially a stable bureaucratic structure, on the micro-level resistance to change, might impede institutional agility. Vice versa, the degree of macro-level agility also gives wiggle room or might limit options for agile organizational structures or procedures (meso) and practices (micro). At the macro level, the general digital transformation underpins institutional agility, automating routine processes and enabling governments to adapt to evolving societal needs, as shown by the example on data analytics in policy services (Simonofski et al., 2018).

All in all, at the macro level, agile government represents a transformative paradigm shift in the way public institutions conceptualize and execute governance (Fangmann et al., 2020; Mergel et al., 2021). Unlike traditional top-down approaches, agile government at the macro level embodies a dynamic and responsive framework that seeks to adapt swiftly to the evolving needs of society (Janssen & van der Voort, 2016; Simonofski et al., 2018). This approach involves not only the reconfiguration of bureaucratic structures but also a cultural transformation, emphasizing collaboration, iterative decision-making, and a focus on delivering value to citizens. At the macro level, agile government requires the establishment of flexible regulatory frameworks, innovative policy-making processes, and the integration of advanced technologies to enhance responsiveness (Kumorotomo, 2020). By fostering cross-sector collaboration, embracing data-driven insights, and enabling continuous feedback loops, agile government at the macro level aims to create a governance ecosystem capable of navigating the complexities of the modern world, addressing global challenges, and improving overall public service delivery (Chatfield & Reddick, 2018).

Among the articles that are part of this special issue, none focuses only on macro-level aspects of agile government (see Fig. 1). However, Hegele and Stoll touch macro-level questions by comparing agile government in different European countries (Austria, Germany, Switzerland), pointing to general characteristics of the different public sectors and administrative traditions and their impact on agile, as well as macro-level contingencies such as constant environmental change und the related uncertainty. Bonomi Savignon and Costumato use the macro-level lens from another angle by pointing to macro-level influences on agile structures in government, such as European regulation requiring project-like actions of governments. Also, Yadav touches macro-level agility by focusing on accountability towards citizens as a central challenge raised by the parallelism of agile and non-agile units. Kühler et al. approach macro-level agility from a more theoretical angle, by discussing general meta-narratives of agile government and their relationship with traditional bureaucracy.

3.2Meso level: Organizational agility

Rooted in organizational theory (e.g. related to optimal structures and procedures, departing from early works of Taylor (1997) or Gulick (1937), but also contingency theory, Burns and Stalker (1969), Thompson (2017)), the meso level emphasizes the internal dynamics of government entities, exploring how they structure themselves to embrace agile principles. What Burns and Stalker (1969) describe as an organic (in contrast to mechanistic) organization, describes an early prototype of an agile organization. Organizational flexibility incorporates concepts from organizational behaviour, management, and leadership studies to understand how hierarchical structures can be flattened, cross-functional teams can be formed, and agile methodologies can be applied to improve responsiveness within specific government agencies or departments. Car-Pušić et al. (2020), for example, describe the implementation of agile structures and procedures (what they call a hybrid agile management model) in a city administration in Croatia. Following the meso-level approach they focus on restructuring the hierarchy, implementing new units and departments, and introducing new work processes. In a similar notion, Kurnia et al. (2022) suggest the redesign of Indonesian local governments into more ‘agile bureaucracies’ among others drawing on flexible expert units in areas prone to natural disasters. They suggest that such an adapted organizational structure improves disaster-resilience and crisis management.

In their systematic literature review Mergel et al. (2018) find four areas of agile approaches in government pointing to different clusters on the meso-level: agile software development, project management, acquisition, and evaluation. Whereas the first three patterns are widely used and studied in the literature, the latter is found to be underrepresented. Software development, project management and acquisition are all centred around procedural questions and touch structural implications, e.g. when it is about the implementation of new departments or teams for these organizational functions. While this shows a clear focus on the meso-level, also determinants on the macro level, such as general resources, social legitimacy and regulations for tendering are discussed, as well as on the micro level, e.g. agile leadership, incentives to raise motivation to shift to agile tools and techniques, are discussed (Mergel et al., 2018).

Hence, agile public organizations on the meso level are mainly discussed from a procedural and structural perspective, pointing for example to agile as a project management approach. However, contextual factors on both, the macro, as well as the micro level influence the success of these innovations. Meso-level organizational flexibility is enhanced through collaborative technology, cloud-based platforms, and agile methodologies, promoting efficient communication, coordination, and project delivery within government agencies.

Some of the few empirical results we have so far on the impact of agile government, are also situated on the meso-level and point to faster processes, also in complex situations. Pauletto (2024), for example, found in the case of the introduction of a loan guarantee scheme for companies during Covid-19 in Switzerland that an agile approach led to a very fast process in terms of designing (10 days) and implementing (5 months) a policy and related tools. They argue that informal organization, flat hierarchy, flexibles roles and iterative subprocesses determine this success. In a similar vein, Moon (2020) suggests that the South Korean government was able to deal with Covid-19 in a more efficient way, because an agile mindset and respective procedures enables quick reactions in terms of testing, disinfection and other ways to prevent infection.

All in all, at the meso level, agile government describes structural and procedural change within specific government agencies, departments, or regional entities. This approach involves the decentralization of decision-making processes, promoting cross-functional collaboration, and instilling a culture of adaptability (Mergel et al., 2021; Soe & Drechsler, 2018). Meso-level agile government encourages the formation of agile teams within organizations, fostering close coordination among diverse units to enhance efficiency and responsiveness (Car-Pušić et al., 2020). Agile government on this level emphasizes iterative development, allowing for incremental progress and the adjustment of strategies based on real-time feedback as well as reacting to changing environmental circumstances (Wernham, 2012). Meso-level agility requires a shift in organizational structures, often adopting flatter hierarchies and flexible project management methodologies (Pauletto, 2024). By streamlining internal processes, agile government at the meso level seeks to optimize the performance of specific government units, ultimately contributing to the broader agility of the entire public sector (Mergel et al., 2021)

Articles in this special issue are covering meso-level aspects of agile government in terms of project management procedures and instruments (Bonomi Savignon and Costumato) and other agile processes (see also Fig. 1). Kühler et al. approach how public managers and employees weave their ideas about agile methods and tools, cultural and structural questions into their broader meta-narratives on agile government. Hegele and Stoll show that a diverse set of stakeholders is positively related to the use of agile methods and processes with the aim of improving relationships and user-centricity. Although Albrecht takes a micro-level focus, she also describes how collaboration can help to develop individual competences, hence pointing to meso-level requirements for micro-level agility.

Neumann et al., in contrast, analyse changes in value creation that are introduced by using agile in public administrations, focusing particularly on the individual and organizational levels. Their findings suggest that agile practices lead to higher efficiency, transparency, user-centricity, better products and services, and improved cross-functional collaborations. Hence, they point to meso and even macro-level effects of micro-level behaviours and factors.

Yadav takes a rather structural meso-level perspective by analysing dual organizational structure arising from combining traditional hierarchy with flatter agile units and related accountability outcomes.

3.3Micro level: Individual and team agility

At the micro level, the concept of agile goes back to psychological theories analysing individual and group behaviour and human resource management and focusing on individual flexibility, collaboration or learning behaviours (e.g., going back to Simon (1997), but also covering motivation and leadership theories, such as self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2008), or change leadership (Gill, 2002). Individual and team agility centres on the behaviours, attitudes, and skills of frontline workers. It considers factors such as leadership styles, employee empowerment, and the cultivation of a culture of innovation at the individual and team levels. This level explores how micro-level agility contributes to the overall adaptive capacity of government organizations. On the micro level, technology facilitates data-driven decision-making, empowers individual and team agility through innovative software solutions, and engages citizens through online platforms, social media, and open data initiatives (Junjan et al., forthcoming).

Fangmann et al. (2020) study agile government from the perspective of agile teams, meaning that these are strong communicators, open to change, develop in iterations, work in a product-driven and improvement-oriented way, and the organization and processes are team-centred. Hence, the focal point here is an optimal team behaviour to achieve agile on a higher level. From a different angle, Patanakul and Rufo-McCarron (2018) analyse agile software development in a governmental program and find primarily micro-level challenges to a successful implementation, such as resistance to change, missing knowledge and skills but also missing training and accessibility to experts, as well as a lack of commitment and ownership for the analysed projects. All these challenges point to classic change management and human resource management implications, such as the need for participation and communication in the implementation of agile, change agents or champions, mentoring and training programs. Similarly, Simonofski et al. (2018) find in focus group interviews with Belgian IT professionals in the local and regional government, that competences of the personnel, their motivation and ability to communicate are key to implement an agile e-government.

Mergel’s (2023) focus on agile as social practice adds another nuance here, namely that while showing public employees the value of agile practices they will adapt accordingly, managers feel threatened in their self-efficacy and status by work practices contesting hierarchy and top-down leadership. This shows that micro-level factors determine the adoption of agile practices on the individual and team-level and in that influence whether agile procedures and structures on the meso-level are enacted or remain paper tigers. Vice versa, if no or insufficient opportunities are given to work in an agile way, be it hindering regulations or culture (macro) or organizational processes or structures (meso), individuals will get demotivated to act in such a way and potentially resist related change projects.

All in all, at the micro level, agile government focuses on day-to-day operations and decision-making processes of individual public servants (Drury et al., 2011; Mergel, 2023). It involves a departure from traditional bureaucratic rigidity towards a more flexible, adaptive, and trustful collaborative work environment (Berger, 2007; Ylinen, 2021). Micro-level agile government requires discretion of frontline workers, encouraging them to make decisions autonomously, respond quickly to emerging challenges, and engage in continuous learning (Thomann et al., 2018). This approach is characterized by iterative problem-solving, allowing individuals to experiment with innovative solutions, receive immediate feedback, and adjust their approaches accordingly. At the micro level, agile government requires a cultural shift towards openness to change, a willingness to embrace uncertainty, and the cultivation of a learning mindset among individual employees (Mergel, 2023). The emphasis on the agency of frontline workers, their openness for uncertainty, failure and learning, shows the inherent interdependence between agile practices on the micro-level and meso-level factors of organizational culture.

Articles that are part of this special issue all analyse individual agile practices but take different angles to do so. While Kühler et al. focus on narratives that public managers and employees create about agile government in order to make sense of the concept, Yadav focuses on their evolving roles in the line hierarchy and agile teams and their related behaviour. In contrast, Albrecht focuses on employees and the competences they need to work in agile government (see also Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Multi-level model of agile in government and the articles in this special issue.

4.Introducing the articles in this special issue

This introductory article maps definitions of agile government and discusses agile government on multiple analytical levels. We started with a discussion on defining ‘agile’ in the context of the public sector. These definitions highlight different aspects and levels of agile, from its organizational processes to its broader implications for governance modes and outcomes.

We translated these different angles of agile government into a multi-level model incorporating: (1) institutional agility on the macro level, emphasizing a dynamic, responsive framework that seeks to adapt swiftly to societal needs through collaboration, technology integration, and innovative policy-making processes and highlighting the importance of environmental influences. (2) Organizational agility on the meso level, focusing on the internal dynamics of government entities and how they adapt structures and procedures to embrace agile principles. (3) Individual and team agility on the micro level, focusing on individual and team behaviours, attitudes, and skills within government organizations.

The articles included in this special issue are all positioned within this multi-level framework (see Fig. 1) and it gets clear that they are all situated at the boundary of multiple levels, making it hardly possible to define and research agile government just on one analytical level. The incorporated articles emphasize the need for agility in government, the challenges of integration with existing hierarchical structures, the importance of leadership, the role of competences and learning, and the interpretation of agile practices within bureaucratic contexts. The articles provide insights into the outcomes, drivers, and barriers of agile adoption within the public sector. Through diverse methodologies (e.g., case studies, standardized surveys, interviews) and perspectives, these articles contribute to a nuanced understanding of the complexities surrounding agile government initiatives.

Hegele and Stoll investigate the growing adoption of agile methodologies within the public sector, aiming to clarify the driving forces behind this transition. The research underscores the significance of political and managerial leadership as well as continuous stakeholder consideration in fostering agility within government entities.

Bonomi Savignon and Costumato advocate for the integration of project management principles within the established field of public strategic management to enhance agility within traditional strategic frameworks. The study identifies five organizational drivers conducive to fostering an agile approach in public strategy implementation.

Yadav explores the challenge of implementing agile principles and practices in public service organizations, particularly in the context of maintaining accountability in the face of simultaneous and parallel maintenance of agile and hierarchical structures/units. They highlight the tension between the desire for agile practices and the persistence of defaulting back to hierarchical models.

Kühler et al. address the need for a deeper understanding of how agile practices are perceived and integrated within government structures. Importantly, the research reveals that agile, perceived as a management fashion, serves as a canvas for projecting desires for modern and digitalized organizations.

Albrecht delves into the integration of agile practices within public sector organizations, especially by using collaborative approaches and informal learning with external stakeholders. She emphasizes the necessity for public servants to acquire a new set of competences to effectively transition these organizations into agile entities.

Neumann et al. address the gap of understanding the outcomes of introducing agile practices within the public sector, which has been extensively explored in the context of private sector organizations. They find individual-level benefits, such as employee well-being, as well as organizational-level improvements, such as cross-functional collaboration.

The special issue is complemented by Gonin’s review of the book “Agile Government: Emerging Perspectives in Public Management”, edited by Melodena Stephens, Raed Awamleh and Fadi Salem from 2022.

5.Conclusion and agenda for future research

Agile in government is conceptualized as a dynamic and adaptive approach, resonating with principles from software development and digital governance initiatives. Various definitions of agile in the public sector range from a focus on responding to changing public needs to its emphasis on work management ideologies and governance innovations. Our multi-level concept of agile government underlines the need for more multi-level research in this emerging field to better understand how these levels interact with one another and what configurations of factors determine success of agile government. The articles in this special serve as a starting point in filling this gap by analysing agile government from diverse perspectives. However, we still see the urgent need that future research further develops in this approach, by systematically combining all three analytical levels.

Furthermore, many studies – also in this special issue – focus on the understanding and definition of agile government, its determinants as well as implementation in governmental practice. While studies from the private sector find empirical evidence that agile practices can lead to a variety of positive outcomes for both individual employees and organizations, such as increased job satisfaction (Tripp et al., 2016), project success (Serrador & Pinto, 2015), and higher performance (Tripp & Armstrong, 2018) research on the (more long-term) impact of agile government still remains scarce. Apart from identifying best practices and success factors for implementing agile government initiatives, examining challenges and barriers to adoption, exploring the role of leadership and organizational culture in supporting agile transformations, the assessment of scalability beyond pilot projects on long-term sustainable and impactful implementation of agile government are key. Here, longitudinal case studies are suited to offer needed insights. Such advancements in research on agile in government could also contribute further to answering the question if agile is more than just a fad. While this will take more efforts and time, we believe it is important to also take a comparative perspective and analyse if a pattern of coherent agile initiatives emerges internationally, and how beneficial and robust their outcomes are across cases.

Moreover, there may be unintended negative side effects when introducing agile in public services – possible dark sides at the individual and/or organizational level – that are so far unknown. For instance, employees may feel overwhelmed, incompetent or insecure as a consequence of this new approach to working, and transparency or accountability issues may arise at an organizational level. When agile government implementation is to be scaled up in the coming years, investigating the potential risks and unintended consequences associated with agile government are key. Here, experimental studies simulating the implementation of agile methods and processes as well as the close and critical analysis of pilot cases might bring the field further. We hope that this special issue serves as a basis and inspires further research on agile government.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carina Schott for her contributions to initiating this special issue and all reviewers for providing valuable feedback on the articles in this special issue. We also want to thank Albert Meijer and William Webster for their continuous support in developing this special issue.

References

[1] | Aldrich, H.E. ((2008) ). Organizations and environments. Stanford Business Books. |

[2] | Atobishi, T., Moh’d Abu Bakir, S., & Nosratabadi, S. ((2024) ). How do digital capabilities affect organizational performance in the public sector? The mediating role of the organizational agility. Administrative Sciences, 14: (2), 37. doi: 10.3390/admsci14020037. |

[3] | Baum, J.A.C., & Amburgey, T.L. ((2017) ). Organizational Ecology. In J.A.C. Baum (Ed.), The Blackwell Companion to Organizations, 1st ed., Wiley, pp. 304-326. doi: 10.1002/9781405164061.ch13. |

[4] | Baxter, D., Dacre, N., Dong, H., & Ceylan, S. ((2023) ). Institutional challenges in agile adoption: Evidence from a public sector IT project. Government Information Quarterly, 40: (4), 101858. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2023.101858. |

[5] | Beck, K. ((2001) ). Manifesto for Agile Software Development, 10. |

[6] | Berger, H. ((2007) ). Agile development in a bureaucratic arena– A case study experience. International Journal of Information Management, 27: (6), 386-396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2007.08.009. |

[7] | Burns, T., & Stalker, G.M. ((1969) ). The management of innovation. The Economic Journal, 79: (314), 403. doi: 10.2307/2230196. |

[8] | Car-Pušić, D., Marović, I., & Bulatović. ((2020) ). Development of a hybrid agile management model in local self-government units. Tehnicki Vjesnik – Technical Gazette, 27: (5). doi: 10.17559/TV-20190205140719. |

[9] | Chatfield, A.T., & Reddick, C.G. ((2018) ). Customer agility and responsiveness through big data analytics for public value creation: A case study of Houston 311 on-demand services. Government Information Quarterly, 35: (2), 336-347. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2017.11.002. |

[10] | Conboy, K. ((2009) ). Agility from first principles: Reconstructing the concept of agility in information systems development. Information Systems Research, 20: (3), 329-354. doi: 10.1287/isre.1090.0236. |

[11] | Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. ((2008) ). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49: (3), 182-185. doi: 10.1037/a0012801. |

[12] | DiMaggio, P.J., & Powell, W.W. ((1983) ). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48: (2), 147-160. doi: 10.2307/2095101. |

[13] | Dingsøyr, T., Nerur, S., Balijepally, V., & Moe, N.B. ((2012) ). A decade of agile methodologies: Towards explaining agile software development. Journal of Systems and Software, 85: (6), 1213-1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.02.033. |

[14] | Dittrich, Y., Pries-Heje, J., & Hjort-Madsen, K. ((2005) ). How to Make Government Agile to Cope with Organizational Change. In R.L. Baskerville, L. Mathiassen, J. Pries-Heje, & J.I. DeGross (Eds.), Business Agility and Information Technology Diffusion, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Vol. 180, pp. 333-351. doi: 10.1007/0-387-25590-7_21. |

[15] | Drury, M., Conboy, K., & Power, K. ((2011) ). Decision Making in Agile Development: A Focus Group Study of Decisions and Obstacles. 2011 AGILE Conference, pp. 39-47. doi: 10.1109/AGILE.2011.27. |

[16] | Dwi Harfianto, H., Raharjo, T., Hardian, B., & Wahbi, A. ((2022) ). Agile Transformation Challenges and Solutions in Bureaucratic Government: A Systematic Literature Review. 2022 5th International Conference on Computers in Management and Business (ICCMB), 12-19. doi: 10.1145/3512676.3512679. |

[17] | Fangmann, J., Looks, H., Thomaschewski, J., & Schon, E.-M. ((2020) ). Agile transformation in e-government projects. 2020 15th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), 1-4. doi: 10.23919/CISTI49556.2020.9141094. |

[18] | Fishenden, J., & Thompson, M. ((2013) ). Digital Government, Open Architecture, and Innovation: Why Public Sector IT Will Never Be the Same Again. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23: (4), 977-1004. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus022. |

[19] | Friedland, R. ((2017) ). The value of institutional logics. In G. Krücken, C. Mazza, R.E. Meyer, & P. Walgenbach (Eds.), New Themes in Institutional Analysis, Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: 10.4337/9781784716875.00006. |

[20] | Gerring, J. ((1999) ). What makes a concept good? A criterial framework for understanding concept formation in the social sciences. Polity, 31: (3), 357-393. doi: 10.2307/3235246. |

[21] | Gill, R. ((2002) ). Change management – Or change leadership? Journal of Change Management, 3: (4), 307-318. doi: 10.1080/714023845. |

[22] | Goertz, G. ((2020) ). Social science concepts and measurement (New and completely revised edition). Princeton University Press. |

[23] | Greve, C., Ejersbo, N., Lægreid, P., & Rykkja, L.H. ((2020) ). Unpacking nordic administrative reforms: Agile and adaptive governments. International Journal of Public Administration, 43: (8), 697-710. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2019.1645688. |

[24] | Gulick, L. ((1937) ). Notes on the Theory of Organization. In Papers on the science of administration. Columbia University. Institute of Public Administration. |

[25] | Henderson-Sellers, B., & Serour, M.K. ((2005) ). Creating a dual-agility method: The value of method engineering. Journal of Database Management, 16: (4), 1-24. doi: 10.4018/jdm.2005100101. |

[26] | Janssen, M., & van der Voort, H. ((2016) ). Adaptive governance: Towards a stable, accountable and responsive government. Government Information Quarterly, 33: (1), 1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2016.02.003. |

[27] | Jilke, S., Olsen, A.L., Resh, W., & Siddiki, S. ((2019) ). Microbrook, mesobrook, macrobrook. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 2: (4), 245-253. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvz015. |

[28] | Junjan, V., Bouzguenda, I., & Fischer, C. (forthcoming). Technology and crisis: Butterfly or domino effect in governing a turbulent world? In The Routledge Handbook on Crisis, Polycrisis, and Public Administration. |

[29] | Kühl, S. ((2023) ). Schattenorganisation: Agiles Management und ungewollte Bürokratisierung. Campus Verlag. |

[30] | Kühler, J., Drathschmidt, N., & Großmann, D. ((2024) ). ‘Modern talking’: Narratives of agile by German public sector employees. Information Polity, 1-18. doi: 10.3233/IP-230059. |

[31] | Kumorotomo, W. ((2020) ). Envisioning Agile Government: Learning from the Japanese Concept of Society 5.0 and the Challenge of Public Administration in Developing Countries. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of Indonesian Association for Public Administration (IAPA 2019). Annual Conference of Indonesian Association for Public Administration (IAPA 2019), Kelod Legian Bali, Indonesia. doi: 10.2991/aebmr.k.200301.008. |

[32] | Kurnia, T., Nurhaeni, I.D.A., & Putera, R.E. ((2022) ). Leveraging Agile Transformation: Redesigning Local Government Governance. KnE Social Sciences. doi: 10.18502/kss.v7i5.10589. |

[33] | Lediju, T. ((2016) ). Leadership agility in the public sector: Understanding the impact of public sector managers on the organizational commitment and performance of Millennial employees [Saybrook University]. https://www.proquest.com/openview/068132931e23fda5144d8c0e3ad0cfef/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750. |

[34] | Lee, G., & Xia, W. ((2010) ). Toward agile: An integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitative field data on software development agility. MIS Quarterly, 34: (1), 87-114. doi: 10.2307/20721416. |

[35] | Li, Y., Fan, Y., & Nie, L. ((2023) ). Making governance agile: Exploring the role of artificial intelligence in China’s local governance. Public Policy and Administration, 09520767231188229. doi: 10.1177/09520767231188229. |

[36] | Madsen, D.Ø. ((2020) ). The evolutionary trajectory of the agile concept viewed from a management fashion perspective. Social Sciences, 9: (5), 69. doi: 10.3390/socsci9050069. |

[37] | Mantovani Fontana, R., & Marczak, S. ((2020) ). Characteristics and challenges of agile software development adoption in brazilian government. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 15: (2), 3-10. doi: 10.4067/S0718-27242020000200003. |

[38] | McBride, K., Kupi, M., & Bryson, J.J. ((2022) ). Untangling Agile Government: On the Dual Necessities of Structure and Agility. In M. Stephens, R. Awamleh, & F. Salem, Agile Government, WORLD SCIENTIFIC, pp. 21-34. doi: 10.1142/9789811239700_0002. |

[39] | Mergel, I. ((2016) ). Agile innovation management in government: A research agenda. Government Information Quarterly, 33: (3), 516-523. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2016.07.004. |

[40] | Mergel, I. ((2019) ). Digital service teams in government. Government Information Quarterly, 36: (4), 101389. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2019.07.001. |

[41] | Mergel, I. ((2023) ). Social affordances of agile governance. Public Administration Review n/a (n/a). doi: 10.1111/puar.13787. |

[42] | Mergel, I., Ganapati, S., & Whitford, A.B. ((2021) ). Agile: A new way of governing. Public Administration Review, 81: (1), 161-165. doi: 10.1111/puar.13202. |

[43] | Mergel, I., Gong, Y., & Bertot, J. ((2018) ). Agile government: Systematic literature review and future research. Government Information Quarterly, 35: (2), 291-298. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.04.003. |

[44] | Meyer, J.W., Scott, W.R., & Rowan, B. ((1985) ). Organizational environments: Ritual and rationality (3. print). Sage Publ. |

[45] | Moon, M.J. ((2020) ). Fighting Covid-19 with Agility, Transparency, and Participation: Wicked Policy Problems and New Governance Challenges. Public Administration Review, 80: (4), 651-656. doi: 10.1111/puar.13214. |

[46] | Neumann, O., Kirklies, P.C., & Schott, C. ((2024) ). Adopting agile in government: a comparative case study. Public Management Review, 1-23. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2024.2354776. |

[47] | Patanakul, P., & Rufo-McCarron, R. ((2018) ). Transitioning to agile software development: Lessons learned from a government-contracted program. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 29: (2), 181-192. doi: 10.1016/j.hitech.2018.10.002. |

[48] | Pauletto, C. ((2024) ). Public management, agility and innovation: The Swiss experience with the COVID-19 loan scheme. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 90: (1), 116-131. doi: 10.1177/00208523221143280. |

[49] | Roberts, A.S. ((2018) ). Bridging Levels of Public Administration: How Macro Shapes Meso and Micro. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3291763. |

[50] | Serrador, P., & Pinto, J.K. ((2015) ). Does Agile work? – A quantitative analysis of agile project success. International Journal of Project Management, 33: (5), 1040-1051. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.01.006. |

[51] | Simon, H.A. ((1997) ). Administrative behavior: A study of decision-making processes in administrative organizations (4th ed). Free Press. |

[52] | Simonofski, A., Ayed, H., Vanderose, B., & Snoeck, M. ((2018) ). From Traditional to Agile E-Government Service Development: Starting from Practitioners’ Challenges. Agile E-Government Service Development, 10. |

[53] | Soe, R.-M., & Drechsler, W. ((2018) ). Agile local governments: Experimentation before implementation. Government Information Quarterly, 35: (2), 323-335. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2017.11.010. |

[54] | Taylor, F.W. ((1997) ). The principles of scientific management. Dover Publications. |

[55] | Teece, D.J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. ((1997) ). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18: (7), 509-533. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z. |

[56] | Thomann, E., Van Engen, N., & Tummers, L. ((2018) ). The necessity of discretion: A behavioral evaluation of bottom-up implementation theory. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28: (4), 583-601. doi: 10.1093/jopart/muy024. |

[57] | Thompson, J.D., Zald, M.N., & Scott, W.R. ((2017) ). Organizations in Action: Social Science Bases of Administrative Theory (1st ed.). Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315125930. |

[58] | Tripp, J., & Armstrong, D.J. ((2018) ). Agile methodologies: Organizational adoption motives, tailoring, and performance. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 58: (2), 170-179. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2016.1220240. |

[59] | Tripp, J., Riemenschneider, C., & Thatcher, J. ((2016) ). Job satisfaction in agile development teams: Agile development as work redesign. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17: (4). doi: 10.17705/1jais.00426. |

[60] | Vogel, R., & Güttel, W.H. ((2013) ). The dynamic capability view in strategic management: A bibliometric review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15: (4), 426-446. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12000. |

[61] | Walsh, P., Bryson, J., & Lonti, Z. ((2002) ). ‘Jack be Nimble, Jill be Quick’: HR Capability and Organizational Agility in the New Zealand Public and Private Sectors. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 40: (2), 177-192. doi: 10.1177/1038411102040002337. |

[62] | Wernham, B. ((2012) ). Agile project management for Government: Leadership skills for implementation of large-scale public sector projects in months, not years. Maitland & Strong. |

[63] | Ylinen, M. ((2021) ). Incorporating agile practices in public sector IT management: A nudge toward adaptive governance. Information Polity, 26: (3), 251-271. doi: 10.3233/IP-200269. |