Project management logics for agile public strategic management: Propositions from the literature and a research agenda

Abstract

In this paper, we call for an integration of project management logics within the now mature field of public strategic management, to analyze the potential contribution of projects in terms of increased strategic agility, in a context where traditional strategic planning and management tools and approaches are increasingly seen at risk of not being responsive enough to rapidly changing external conditions.

To pursue this objective, we carry out a problematizing literature review on the two streams, by incorporating journal and book contributions from the last 30 years on Web of Science Database. 509 contributions have been quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed to answer two interconnected research questions: What is the state of the art in the literature on the interactions between project management and public strategic management? And, how can project management logics be integrated within traditional strategic planning and management processes in the public sector in order to achieve strategic agility?

We find that, until today, public management literature has only sporadically dealt with the potential influence of project management logics on strategic management and, more in detail, strategy implementation. Furthermore, the review enables a discussion of five organizational drivers fostering an agile approach in public strategy implementation. Using a narrative approach, they then lead to the formulation of five researchable propositions.

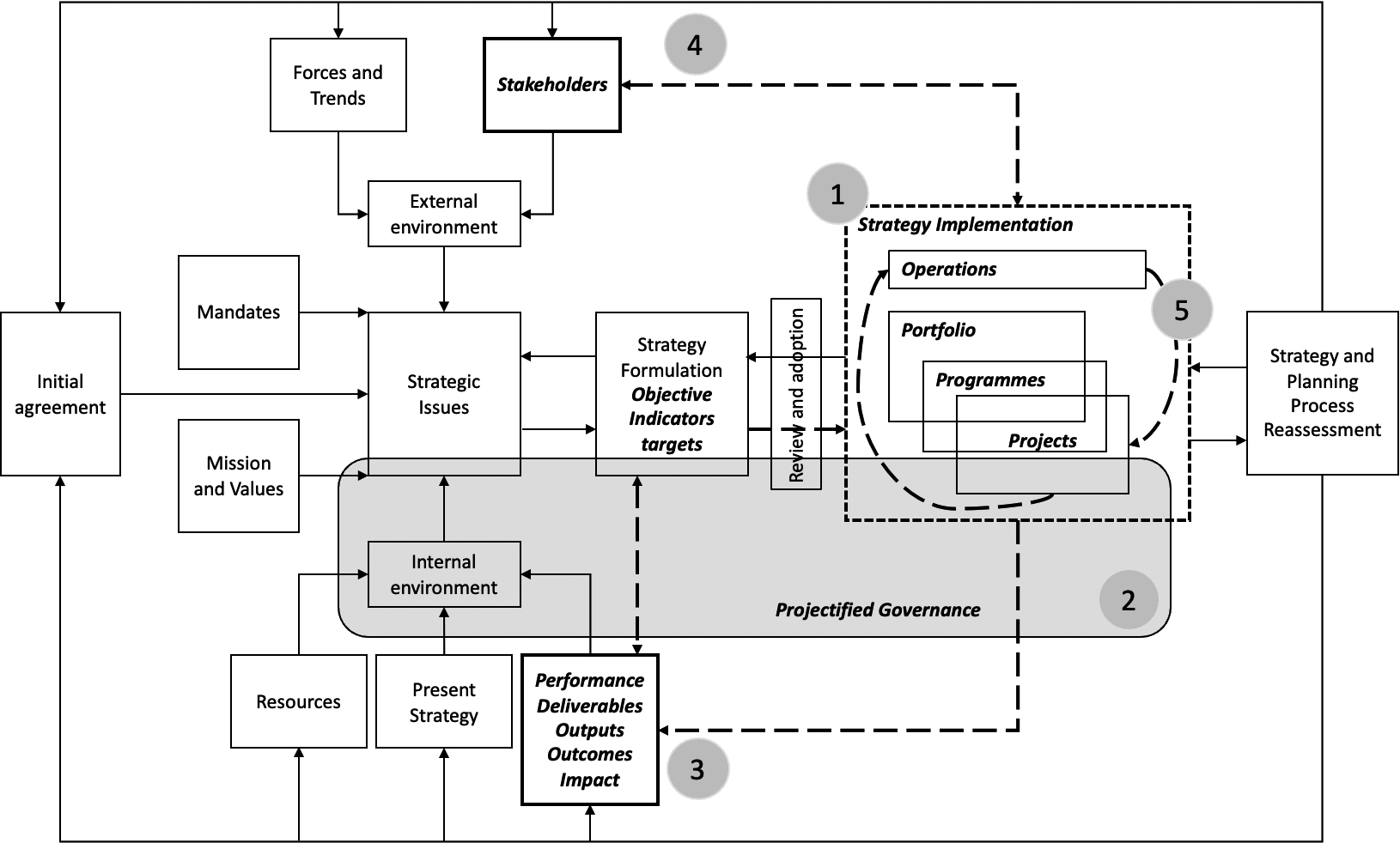

We conclude by proposing an updated model of the strategic planning and management cycle in the public sector, factoring in potential agile practices and feedback mechanisms induced by incorporating project logics in the implementation of strategy.

1.Introduction

Recent years have seen an increasing tendency towards the incorporation and use of portfolio, programme and project management (PPPM) logics as a new standard for public sector organizations (PSOs). Compared to the traditional bureaucratic orientation of the public sector, working through projects allows for more flexible and agile management of resources and, in addition, has potential benefits regarding internal and external stakeholders’ engagement (Gasik, 2016). Initially mostly attached to complex infrastructure and IT endeavors, projectification is steadily becoming a pervasive feature within PSOs in a wide range of policy fields, not only related to domains such as structural or technological investments, but also in regulatory or service-oriented areas (Hodgson et al., 2019).

Therefore, while the public sector has traditionally been associated with routine, hierarchy, and stability, projects denote, in principle, a different logic of discontinuity, flexibility, and innovation, which seems to be in line with an agile approach to strategy implementation (Serrador & Pinto, 2015). The concept of agility has been introduced to identify a set of values and techniques allowing organizations “to work on smaller increments, review their work often, and include feedback right away to avoid costly failures” (Mergel et al., 2021, p. 161). Starting from this broad conceptualization, adopting agile management in the public sector is increasingly seen as an alternative to hierarchical public sector management, as it can provide solutions for responding to changes and fast-evolving public needs in an efficient way (Ylinen, 2021). Even though agile management is presented as a solution to “reshape government, public management, and governance in general” (Mergel et al., 2021, p. 161) its introduction in public sector organizations is sometimes expected to hold a great deal of complexity due to tensions between agile values and the existing government culture which is often characterized by bureaucracy (Crawford & Helm, 2009). The concept of strategic agility refers to the organization’s capacity to proactively identify complex challenges to be answered, avoid unnecessary crises, and carry out strategic and structural changes in an orderly and timely manner (Doz et al., 2018). The dynamics of strategic agility have been studied mainly in the private sector, and they deal only sporadically with the peculiarities of PSOs (Ludviga & Kalvina, 2023; Liang et al., 2018). Responding proactively to emerging policy challenges requires the presence of both a long-term organizational strategy and specific organizational processes that facilitate learning-by-doing (Pot et al., 2022).

Despite its potential, extant public management research has devoted little attention to the role projects and PPPM logics play in shaping, influencing, and implementing a strategic agility discourse within PSOs (Baxter et al., 2023); even more so in a context where traditional strategic planning and management tools and approaches are increasingly seen at risk of not being responsive enough to rapidly changing external conditions, in the form of emerging social, political, cultural stances (Mitchell & Mitchell, 2023). On the contrary, the focus of public management scholars has been on understanding the differences between public and private projects (Gasik, 2016), the impact of the strategy on project success (Gomes et al., 2008), and the use of agile methodologies in the management of individual projects (Lappi & Altonen, 2017).

This paper aims at exploring the role of PPPM as a driver for increased responsiveness, reactivity and, ultimately, agility of public strategic planning and management. To pursue this objective the paper answers the following two related research questions: What is the state of the art in the literature on the interactions between PPPM and public strategic management? And, how can PPPM logics be integrated within traditional strategic planning and management processes in the public sector in order to achieve strategic agility? To answer our research questions, we perform a problematizing literature review (PLR) of journal and book publications produced over the last thirty years on the topics of portfolio, programme and project management in relation to agile public strategic management.

A PLR aims not only to provide a deep understanding of what has been said on a specific topic from different field perspectives, but also tends to develop specific propositions or new theoretical perspectives to enrich prior theories (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2020). Nevertheless, since PLRs often lack methodological robustness (George et al., 2023), we apply a systematic methodology to collect and present our results and, finally, to link them with the formulation of theoretical propositions.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: the next section presents our theoretical background; the review protocol is shown in the method Section 3; after presenting our results in Section 4, we discuss existing research trends in Section 5 and propose a revised and adapted strategic management framework considering the realities PPPM incorporation in strategy brings forth. We conclude with a set of propositions stemming from the literature to be tested and validated with empirical studies in order to frame and stimulate further research on the topic.

2.Background

Strategy in the public sector is about defining a concrete approach to align the aspirations and the capabilities of public organizations or other entities in order to achieve goals and create public value. Strategic management typically comprises (a) strategic planning; (b) budgeting, performance measurement and management, and evaluation (ways of implementing); and (c) feedback among these elements to enhance fulfillment of the mission, the meeting of mandates, and sustained creation of public value via strategic learning (Poister, 2010; Bryson, 2018; Bryson & George, 2020). Strategy’s typically longer-term nature can alter the order of, and blur the distinction between planning and implementation. Over time planning can lead implementation, follow it, or blend with it, since strategizing should be both deliberate and emergent. For example, many public organizations’ strategic plans have a three- to five-year time frame.

Approaches and frameworks for strategic planning have been widely used and diffused in the public sector. Among the most cited and influential process-based approaches, the Strategy Change Cycle by Bryson (2018) envisions ten steps: 1. Initiate and agree on a strategic planning process; 2. Identify organizational mandates; 3. Clarify organizational mission and values; 4. Assess the external and internal environments to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats; 5. Identify the strategic issues facing the organization; 6. Formulate strategies to manage the issues; 7. Review and adopt the strategies or strategic plan; 8. Establish an effective organizational vision; 9. Develop an effective implementation process; and, 10. Reassess the strategies and the strategic planning process.

At the same time, little research has been devoted to strategic plan implementation in the public sector (step 9 in the process), and especially to the conditions linking the features of strategic planning to the success of strategy implementation (George, 2021), leading some authors to call for further exploration of the contingencies of implementation (Mitchell, 2019). It has thus been argued that, without this focus on implementation, strategic planning could not be responsive enough to emergent circumstances, since strategy is not just about what is in strategic plans: on a regular basis, public entities need to ensure their strategies suit current conditions. Strategizing is not a one-off activity, and it is typically needed whether it results in a long-term strategic plan (Bryson & George, 2020).

A similar preoccupation is the focus of the emerging agile approach and set of work practices; situations where the solutions to complex and non-linear problems, or innovation needs, cannot be addressed by exploiting the existing known work practices and administrative routines (Mergel, 2023). Agility has been defined as a set of “values and techniques allowing the project team to work on smaller increments, review their work often, and include feedback right away to avoid costly failures” (Mergel et al., 2021, p. 161). Applying agile principles is, in other words, seen as a way for responding to changing and fast-evolving public needs in an efficient way (Ylinen, 2021; Mitchell & Mitchell, 2023). It echoes early calls by Lindblom (1959) for the need of iterative design and incremental muddling through, since the assumption of a complex and mostly uncertain future calls, in Lindblom’s view, for a stepwise planning approach instead of large-scale and long-term strategic planning attempts, which have to be adjusted over time. This fundamentally opposes the otherwise linear policy development and implementation assumptions public administrations have to follow based on existing policies and processes (Mergel, 2022). Agile is commonly contrasted with the traditional waterfall method, in which each project phase has to be carried out in sequence, and agility originally denotes a paradigm for better project management to avoid large-scale project failures at the end of the project and funding period (Mergel, 2016; Project Management Institute, 2017). Agile practices are increasingly required in the public management toolbox, as governmental capacity to address strategic issues and complex societal needs relies more and more on the ability to incorporate agile practices in strategy implementation (Mitchell & Mitchell, 2023).

In the context of an overarching strategic orientation, projects are commonly contrasted to operations or activities on the grounds of their temporality and their orientation to produce innovation, added value, or new capabilities, against clearly predefined objectives. The Manifesto for Project Management Research (Locatelli et al., 2023, p. 1) claims that “projects (which drive change and innovation) and operations (which make organizations run daily) compete and collaborate as leading economic agents”. Projects, defined as temporary endeavors undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result (Project Management Institute, 2021), are commonly applied to reform or transform services in the form of pilots, programmes, task forces, and similar organizational arrangements (Hodgson et al., 2019). Due to their nature, it has been argued that the shift towards the increasing use of projects is “one of the most important – although still very much neglected – administrative changes of the past decades” (Sjöblom & Godenhjelm, 2009, p. 165). Project management has emerged within the wider discourse on public sector managerialism (or NPM) (Hodgson et al., 2019). The main NPM incentive for the introduction of project management in PSOs can be recognized in the focus on expenditure reduction while, at the same time, improving government performance (Crawford & Helm, 2009). A strong, albeit not exclusive, push towards the orientation to projects in the public sector has been brought forward by European Union policies, with the majority of the entire European Union budget now managed through different project funding systems regarding research, social, and regional development (Godenhjelm et al., 2019; Mukhtar-Landgren & Fred, 2019). There is widespread reliance on projects as agents of change to drive the innovation and change required to tackle grand challenges (Locatelli et al., 2023).

Following Fred (2020), we employ the term project management logic as a type of institutional logic, to define practices delivering both controllability and unpredictability, promising a solution to clearly defined objectives, plans of how to reach them, and techniques for how to evaluate them, at the same time as they can be argued to deliver innovation and organizational change. Usually, projects are organized functionally in programmes (sets of logically connected projects) and/or in portfolios, which group together wide ranges of activities, programmes, and projects under a single category (Roberts & Hamilton Edwards, 2023). Projects can be considered organizational means to fulfill strategic objectives; the overall strategic positioning of the organization (in terms of mandates, mission, vision, stakeholders, and internal/external conditions) is seen as a contextual driver enabling the decision of whether and which projects should be initiated (Ives, 2005). Importantly, a project is essentially seen as successful if its results (tangible or intangible) exceed the resources invested to bring it to completion.

Agile approaches, toolkits, and work practices have been so far mostly studied in the context of individual projects (Baxter et al., 2023). There is, to date, no systematic conceptualization about the necessary prerequisites for public administrations to engage in agile efforts, or about what makes agile a superior approach to strategic planning and other established management approaches used in public administrations. With this paper we intend to analyze and conceptualize the idea of agility within the overarching strategic approach of public administrations, since one of the conceptual and empirical puzzles that remains unsolved in this field is how bureaucracies can adapt to or how agile approaches can be aligned with the needs of standard administrative processes (Mergel, 2023). In other words, we refer to strategic agility as the ability to respond proactively to unexpected developments, and as a requirement for organizations to deal with various possible scenarios (Pot et al., 2022; Howlett et al., 2018). Strategic agility fosters the connection between strategic planning and implementation, and should be seen as a set of initiatives an organization can readily implement. Although the public sector is called to develop strategic agility to address increasingly complex social issues under rigid budget constraints and continuously growing public expectations, there has been insufficient theoretical systematization on how PSOs can become more strategically agile (Liang et al., 2018), mostly ignoring, with few exceptions (Mitchell, 2019), the potential role of PPPM logics.

Scaling the idea of agility upwards, from the internal logics of projects up to the overall strategy of a PSO, we investigate if and how an intentional, systematic and ordered integration of PPPM logics within the extant strategic management frameworks of public organizations can represent an approach to pursue strategic agility. Project management and strategic management literatures in PSOs have so far largely progressed on apparently parallel trajectories. Conceptually, little has been contributed in terms of how projects are embedded within the overall strategic framework of a public organization, and about if and how projects can become drivers for change of how strategies are defined and implemented (Mergel, 2018).

3.Method

To answer our research questions, we review the literature to problematize the role of PPPM in fostering an agile approach for strategy implementation in PSOs. The ambition of a problematizing literature review (PLR) is to re-conceptualize existing thinking to provide new ideas and theories following the four core principles defined by Alvesson and Sandberg in their work (2020); namely the ideal of reflexivity, reading more broadly but selectively, not accumulating but problematizing, and the concept of less is more. However, as argued by George et al. (2023) in their article on how to innovate literature reviews in the public administration field, problematizing reviews often lack robustness about how data are collected and analyzed.

Trying to address this gap, we incorporate bibliometric techniques in our review to systematically navigate our sample and provide inputs for an adaptation of the original process framework on strategic management created by Bryson in 2004 (and last updated in 2018).

The blend of this different literature review approaches increases the capacity to serve two different purposes: on the one hand, to systematically describe the sample obtained with the application of a rigorous review protocol, offering the whole picture of what has been said by previous scholars coming from different research fields; on the other hand, to define a new research agenda and a re-conceptualization of prior theories.

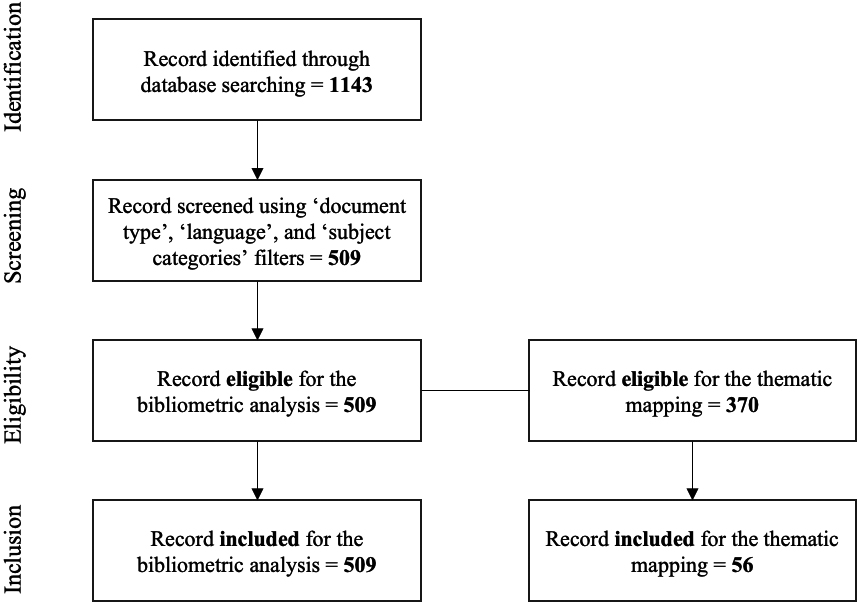

Figure 1.

The literature review PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1 shows the complete literature review PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009). The first step was to identify the most suitable set of keywords to gather all the relevant sources. Besides that, we selected the Web of Science core collection database, as it is considered the world’s leading scientific citation search and analytical information platform (Li et al., 2018). In addition, Web of Science (WOS) allowed us to search the preferred keywords in each document’s title, abstract and author keywords simultaneously (coded as TS

Since this paper aims to describe the role of PPPM as a driver for increased responsiveness, reactivity and agility of PSOs strategy implementation, we define three rows of keywords to run on the Web of Science advanced search: the first row allows us to identify all the main contributions about the concepts of portfolio, programme, project, and agile management (Mergel et al., 2021), and those dealing with the phenomenon of projectification (Godenhjelm et al., 2015); with the second row, we restricted the search scope to the public sector field; finally, the third row determined which domains are involved in the analysis, namely the strategic management and implementation within PSOs (George, 2021; Vandersmissen & George, 2023). The generic keyword agility has not been included to avoid a proliferation of irrelevant papers. The chosen keywords, indeed, allow us to specifically look for all contributions dealing with the intersection between strategic agility and PPPM logics in the public sphere. Following this approach, the performed query was the following:

((TS

The first round of search (identification) returned a vast number of results (

Table 1

Review protocol

| Step | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| Database | Web of Science – full collection | |

| Keywords | ((TS | 1143 |

| Timeframe | 1992–2023 | 1143 |

| Document type | Article or Review Article or Book Chapters | 838 |

| Language | English | 787 |

| Subject categories | “Management” or “Business or Economics” or “Public Administration” or “Information Science Library Science” or “Environmental Sciences” or “Environmental Studies” or “Computer Science Information Systems” or “Operations Research Management Science” or “Public Environmental Occupational Health” or “Regional Urban Planning” or “Development Studies” or “Education Educational Research” or “Urban Studies” or “Health Policy Services” or “Political Science” or “International Relations” or “Law” or “Area Studies” or “Sociology” or “Social Issues” | 509 |

Our third step (eligibility) needs a bit more of specification, as we defined two distinct datasets of articles with two distinct purposes. The first consists of the entire sample (

More precisely, as we incorporated different literature review methodologies, we considered eligible and included (step four) for the bibliometric analysis all the results from the previous step (

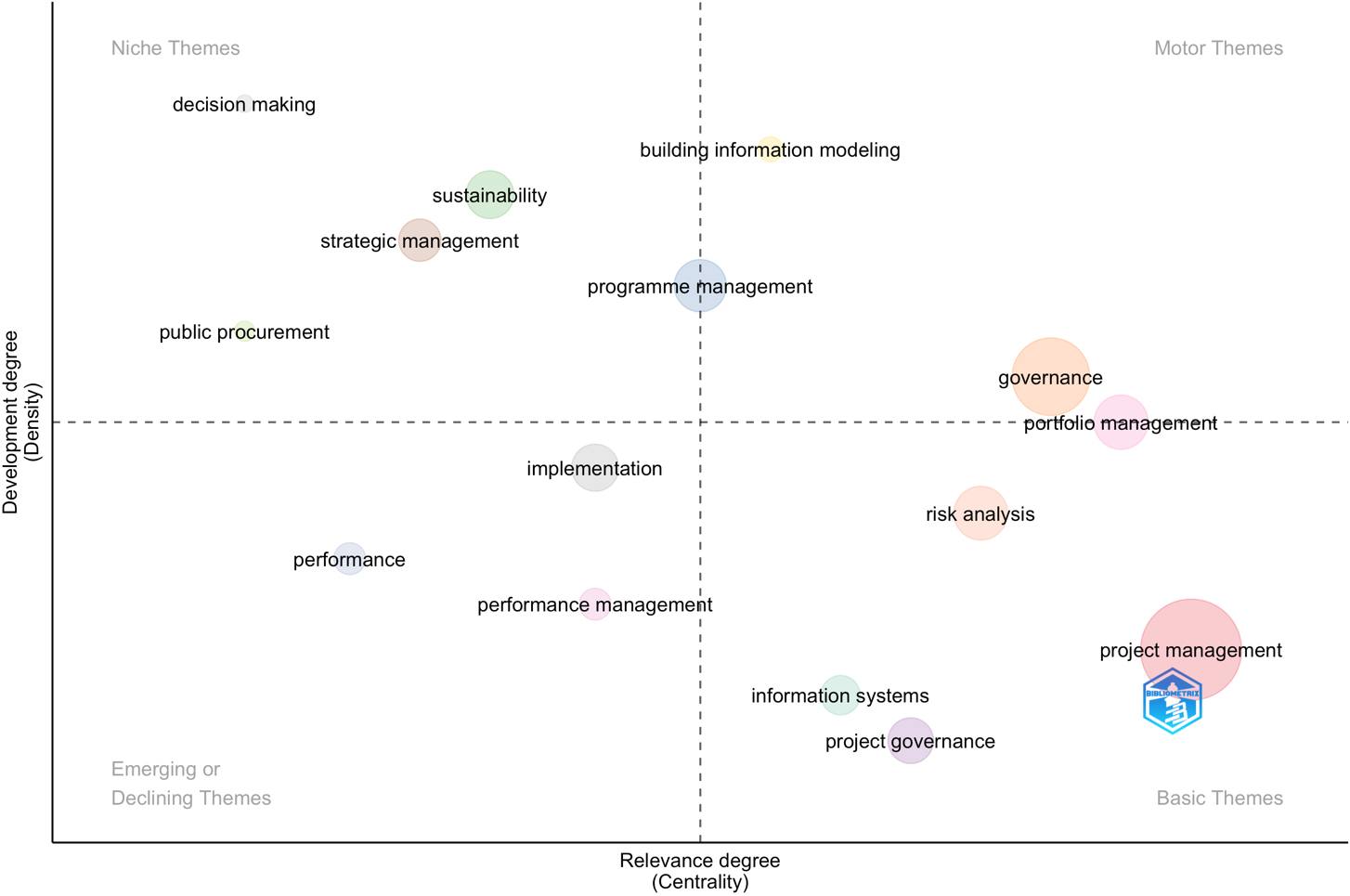

At the same time, we wanted to isolate the most significant papers allowing us to answer our second aim of problematizing and re-conceptualizing existing knowledge on strategic management in the public sector. To this end, using thematic mapping, based on the analysis of keywords attributed to the documents by their authors, we identified 370 results grouped in 15 macro-themes that result from the intersection of two dimensions: density and centrality, where density measures the internal strength of a theme’s development, and centrality measures the intensity of links among thematic groups, describing the importance of a theme in the whole collection (Callon et al., 1991).

These analyses were supported by a free bibliometric software: version 4.1.3 of bibliometrix R-package was used to implement the bibliometric analysis (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017).

In the fourth step (inclusion) we focus on thematic mapping results (

These inclusion criteria also guided the clusterization of the selected 56 articles into five clusters, representing organizational drivers of agility in public sector: project management, strategic management, performance management, governance, portfolio/programme management.

4.Results

4.1Bibliometric analysis

To answer our first research question about the state of the art in the literature dealing with the interactions between PPPM and public strategic management under the lens of strategic agility, we shortly introduce a bibliometric description of our sample (

Table 2 shows the main information of the sample. In a nutshell, from 1992 to July 2023, 509 documents were written by 1492 authors and published in 262 sources (journals and books).

Table 2

Main information of the collection

| Description | Unit | Results |

|---|---|---|

| MAIN INFORMATION ABOUT DATA | ||

| Timespan | Years | 1992:2023 |

| Sources (Journals, Books, etc) | Number | 262 |

| Documents | Number | 509 |

| Annual Growth Rate | Percentage | 11.6 |

| Document Average Age | Years | 6.88 |

| Average citations per doc | Number | 17.39 |

| Total references | Number | 25056 |

| DOCUMENT CONTENTS | ||

| Keywords Plus (attributed by Web of Science) | Number | 999 |

| Author’s Keywords (attributed by the Authors) | Number | 1673 |

| AUTHORS | ||

| Authors | Number | 1429 |

| Authors of single-authored docs | Number | 91 |

| Single-authored docs | Number | 94 |

| Co-Authors per Doc (Authors appearances/Documents) | Number | 3.01 |

| International co-authorships (Multiple Countries Publication/Total Publication) | Percentage | 27.5 |

| DOCUMENT TYPES | ||

| Article | Number | 459 |

| Book chapter | Number | 8 |

| Early access | Number | 21 |

| Proceedings paper | Number | 7 |

| Retracted publication | Number | 1 |

| Review | Number | 13 |

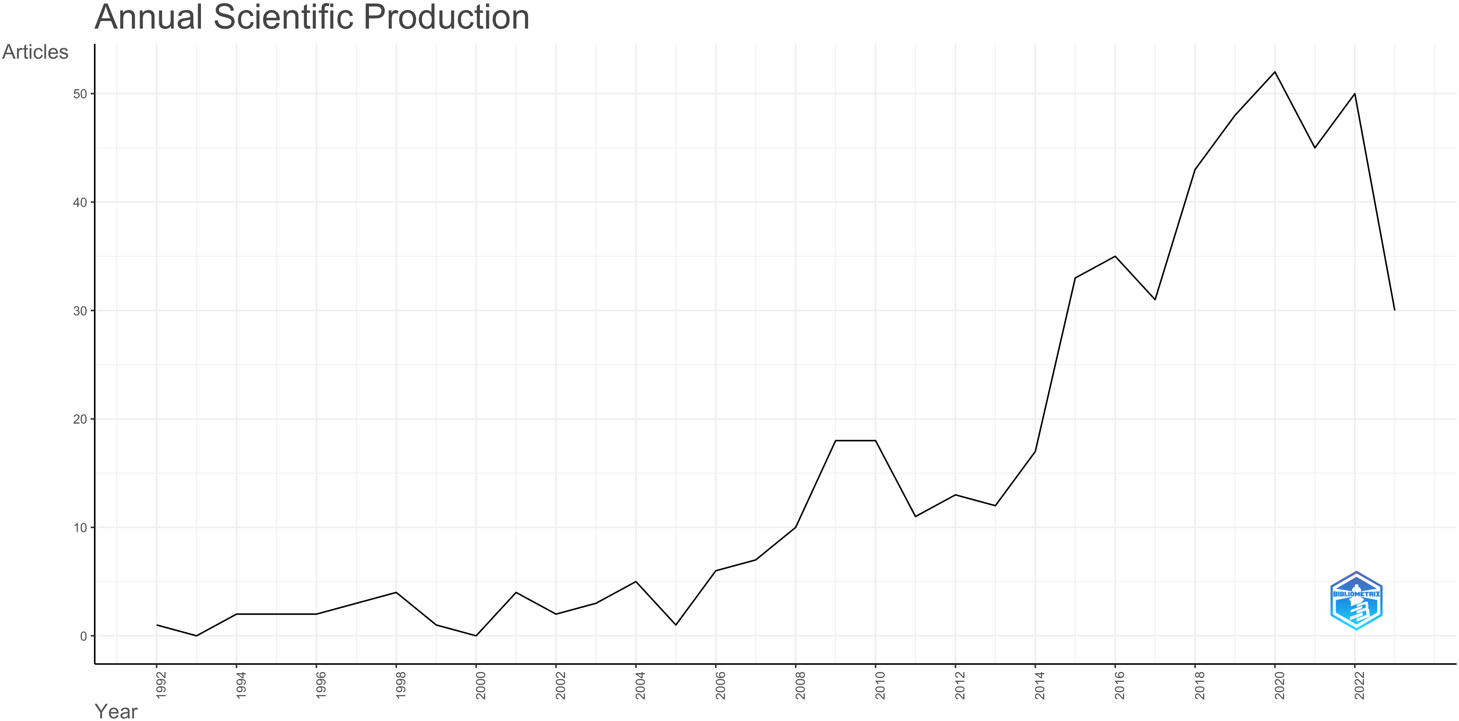

The annual scientific production (Fig. 2) shows that the interest in the topic discussed has been increasing in the last twenty years, with the highest number of publications in 2020 (

Regarding the most relevant sources (Table 3), we recognize three outstanding journals in the project management field: namely, the International Journal of Project Management, with the highest number of articles published in the sample (33), the International Journal of Managing Projects in Business (23 contributions), and the Project Management Journal (15 contributions).

Overall, this finding suggests that, until today, a concrete contribution to understanding the role of PPPM in PSOs lies within the project management branch of knowledge. Among the first ten sources, only one journal has public sector dynamics at the heart of its aim and scope: Government Information Quarterly, with eight articles in the collection.

Table 3

Most relevant sources

| Sources | Articles |

|---|---|

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT | 33 (6.48%) |

| ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION AND ARCHITECTURAL MANAGEMENT | 30 (5.89%) |

| SUSTAINABILITY2 | 23 (4.52%) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MANAGING PROJECTS IN BUSINESS | 22 (4.32%) |

| PROJECT MANAGEMENT JOURNAL | 15 (2.95%) |

| JOURNAL OF CLEANER PRODUCTION | 10 (1.96%) |

| GOVERNMENT INFORMATION QUARTERLY | 8 (1.57%) |

| BMC PUBLIC HEALTH | 5 (0.98) |

| IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON ENGINEERING MANAGEMENT | 5 (0.98) |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT | 5 (0.98) |

Figure 2.

Annual scientific production.

This trend is confirmed by two additional results. First, the Most Local Cited Sources – which calculates the primary sources cited by the articles in the collection starting from the articles’ references – where we can observe that the most cited papers are published by the International Journal of Project Management and Project Management Journal with, respectively, 1781 and 378 citations. Public Administration Review is the top-cited public management journal with 230 citations.

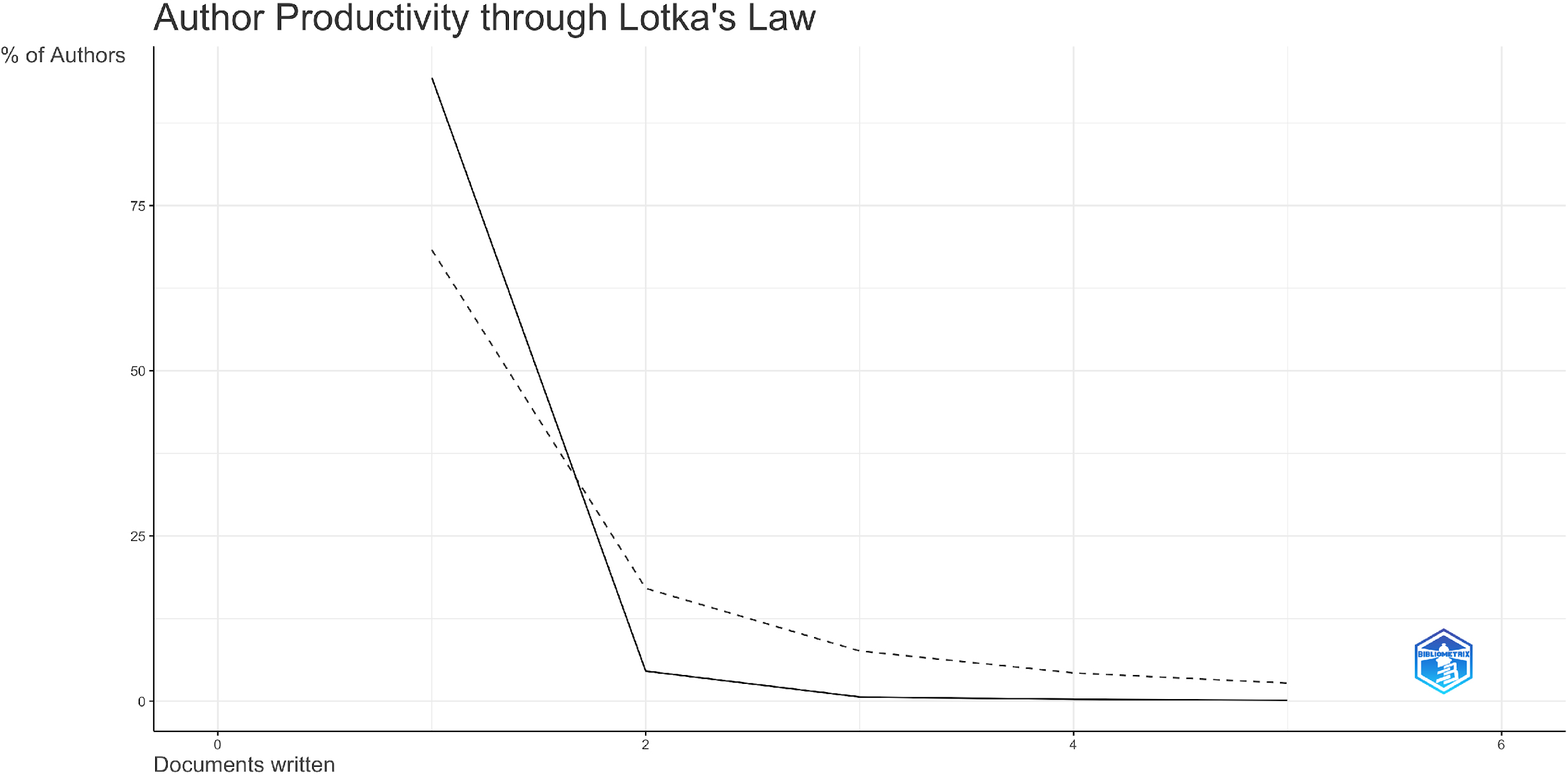

The authors’ examination suggests a crucial feature of the investigated field and allows us to answer our first research question. Indeed, analyzing authors’ productivity through the bibliometric Lotka’s law provides an explicit and robust indication about the field maturity, i.e. whether it is possible to recognize an homogeneous or heterogeneous subject distribution regarding a specific topic. More precisely, Lotka’s law describes the frequency of publication by authors in any given area and time-frame, allowing the identification of how many authors have only occasionally written about the topic and how many have published many documents in the field (Pao, 1985).

We find that this field of research is not mature as only nine authors have written at least three articles over the last thirty years, while 1349 occasional authors have written just one article. The plot in Fig. 3 displays that the collection frequency is behind the theoretical distribution (dotted line) of Lotka’s law. In other words, while agility in government can be considered a well-defined stream of literature since the publication of the Agile Manifesto (Beck, 2001), the specific impact of PPPM logics in fostering government agility is still an underestimated topic in the public management field.

Figure 3.

Lotka’s law applied to the sample.

After highlighting the fundamental characteristics of the obtained sample, with specific regard to journals and authors, it is worthwhile to present the bibliometric findings about the documents.

To this end, we analyzed documents keywords provided by their authors and those ascribed by Web of Science (keywords plus). In summary, project management outnumbers portfolio, programme, and agile management. This trend can be linked to the nature of most relevant sources that have published articles in this field. Nevertheless, other keywords frequently used – such as Project success, Risk management, and Megaprojects – confirm that, until today, the literature has dealt with the relationship between PPPM and PSOs by focusing primarily on the implementation and governance of individual projects, with limited analyses of how PPPM impacts on strategic management.

4.2Organizational drivers for agile strategic management

This section delves into our second research question on how PPPM logics can be integrated within traditional strategic planning and management processes in PSOs, in order to achieve strategic agility. While within the previous section we have provided quantitative insights to demonstrate the scarce development of an autonomous stream of literature, in this section we adopt a narrative approach to problematize the multiple scientific perspectives that offer insights about this topic.

Using thematic mapping based on Callon’s et al. (1991) bibliometric indicators, we identified 15 macro-themes, shown in Fig. 4. The bubble size is proportional to the groups’ word occurrences, and the bubble labels are words with higher occurrence values. The groups with high density and high centrality are named motor themes as they are crucial and well-developed topics that strongly link with other themes in other quadrants. Those with high density and low centrality are developed but, at the same time, isolated themes. Those with low density and low centrality are emerging or declining themes. Finally, those with low density and high centrality are basic and transversal themes focusing on general issues that cross-cut the different research areas of a domain (Yu et al., 2021).

Figure 4.

Thematic map and macro-themes.

Using the inclusion criteria described in the method 314 results were excluded, as they did not directly engage with the aims of our research questions. This step brings the overall sample down to 56 results consistent with our research purposes.

These 56 articles were considered as the literature source to advance insights about factors that can improve public sector strategic agility through the incorporation of PPPM logics. We analyze these factors by clustering them in 5 thematic groups; it is then possible to link each cluster to a type of organizational driver. To our purposes, organizational drivers are structures, processes or contextual factors (Lewis et al., 2017) that, within a public organization, support the achievement of strategic agility. The identified drivers are project management; strategic management; performance management; governance structures; and portfolio/programme management.

Significantly, we could not recognize an autonomous thematic cluster on agility or agile management, signifying how this topic is still fragmented and underdeveloped in this context. Still, it was possible to trace back conceptual elements and dimensions which are relevant for strategic agility within each of the clusters; as such, the discussion of each of our clusters engages as well with the extant literature on agility. This analytical approach is then synthesized in our propositions.

4.2.1Project management

The breakdown of the first and, quantitatively speaking, largest thematic cluster highlights its strong heterogeneity. Until today, project management scholars have addressed various issues from several perspectives; in this sense, project management has acted as a chance to deepen several public management topics from different angles (Wirick, 2011). Notwithstanding, this approach has hindered the growth of a unique and autonomous public project management research field, in which the concept of agility would be predominantly linked to the application of agile practices and methodologies in managing public projects, especially in the IT sector (Lappi & Altonen, 2017). Although the influence of agile practices in project management has often been identified as a potential driver to prepare PSOs for innovation (Dittrich et al., 2005), such a perspective does not fully represent the expected influence of PPPM logics on strategic management. Indeed, more traditional waterfall approaches to the management of projects could still be seen as drivers of strategic agility (Mitchell & Mitchell, 2023).

Overall, among the articles of this cluster we found independent and unrelated contributions mainly dealing with the internal circumstances of projects realized in the public sector (Crawford & Helm, 2009). A significant group of papers, for example, is about the management of public construction projects; their primary input to strategic management can be found in the explanation of why public-owned infrastructural projects fail due to bureaucracy, corruption, poor planning and the role of contractors (Aerts et al., 2017; Padhi & Mohapatra, 2010; Damoah & Kumi, 2018; Ghanbaripour et al., 2020). These articles pay more attention to internal project implementation drivers and barriers and do not provide relevant suggestions on how project management might influence the agility of a PSO strategy.

A second homogeneous group of articles encompasses all the papers about Public-Private-Partnerships (PPP) projects (Ruuska & Teigland, 2009; Osei-Kyei et al., 2017; Kavishe et al., 2018; Parker et al., 2018). Similarly to what was found for construction projects, the focus is on how to address managerial challenges to enhance PPP results (Krogh & Thygesen, 2022), reinforce the legitimacy of a PPP externally and internally (Matinheikki et al., 2021), and identify and assess project risks (Ghribi et al., 2019).

Further articles have tested the role of project management in e-government projects (Fernandes et al., 2017; Anthopoulos et al., 2016; Rose & Grant, 2010; Glyptis et al., 2020). Although e-government articles take on an internal point of view similar to those on construction and PPP, some preliminary insights about the relationship between projects and strategy emerge. In 2010, Sharif et al. found a set of factors to be considered to ensure that e-government projects achieve their results and contribute to the digital transformation strategy (decision-making, practitioner concerns, evaluation methods, and performance assessment), but, at the same time, they do not delve deeper on how to link the project success to the overall organizational performance. As well as previous examples, the last group of factors again deals only with project accomplishment. Similarly, Melin and Wihlborg (2018) show that strategic planning and project management can be balanced and thereby reach a more sustainable outcome at their crossroad. Specifically, the authors argue that the legitimacy of PSOs builds on citizens’ trust and transparency, as well as on an adequate legal framework. As such, legitimacy must be managed through combined and reliable traditional project management processes used to enhance the agility of strategy implementation. Overall, in the context of a highly fragmented cluster, the latter is the main finding within the project management theme for our aims.

4.2.2Strategic management

The strategic management cluster appears as an internally well-developed niche theme, with little ties to the other clusters (Fig. 4). Agile (or adaptive) approaches, together with collaboration-oriented strategies, can foster the capacity of PSOs to address crises (Nolte & Lindenmeier, 2023). If, on the one hand, the literature has highlighted the relevance of strategic planning in making governments more agile (Ansell et al., 2023), at the same, insights on how to be agile in implementing public strategies are still scarce, with few exceptions (Beste & Klakegg, 2022; Joyce, 2021).

Despite this, the analyzed articles broadly recognize projects as a potential enabling factor for achieving organizational strategic goals, although integrating strategic management and PPPM is not always easy for several motivations: little connection between project purposes and strategic goals; decision-making and reporting not concentrating their evaluation on projects; challenges in monitoring strategic plans due to rapid changes in government policy (Nilsen & Feiring, 2023; Söderberg & Liff, 2023). As argued by Young et al. (2012), paying little attention to how projects are selected and governed might generate paradoxical situations in which, even when projects achieve their results, they do not support strategic goals’ success.

Until today, the concept of implementation has received little consideration in the academic debate and, in parallel, in political and administrative agendas (Jensen et al., 2018). The reason behind poor attention to implementation aspects must be linked to how contemporary social problems are interpreted by academics and politicians: both groups, indeed, assume that tackling the so-called wicked problems (Alford & Head, 2017) is a matter of governance rather than strategy implementation. Thus, the main contribution by Jensen et al. (2018) is to identify preliminary intermediary variables between governmental priorities and effective performance: for instance, the systems of governance, social interactions and hierarchies can be classified in terms of congruence, or the extent to which a chosen mode of implementation – in this case, project management – fits with the logic of the organization’s mainstream operations.

Mitchell (2019) expands Jensen et al. (2018)’s focus, by claiming that many public management scholars focused on the alignment of organizational strategy, environmental conditions, and final results, ignoring the complexities associated with the moment of strategy implementation. The hypothesis is that strategic initiatives and projects have numerous similarities and, consequently, public management scholars can learn a lot from project management practices, especially regarding implementation effectiveness and efficiency. Therefore, the strategic context is identified as the missing variable for incorporating projects in strategy implementation, where the context is defined by the organizational priority of the strategy and the overall complexity of implementation (Mitchell, 2019). In a nutshell, organizational priority can be described as a factor that affects the strategic management approach, while elements such as past performance, environmental stability, technical uncertainty, and project size all feed into the overall complexity of implementation. In conclusion, further investigation on the relationship between strategy implementation and project management by incorporating project management practices into conceptual and methodological strategy design, and expanding the information collection about the topic are recommended.

Several articles have dealt with how organizational governance can boost the assimilation of projects into the overall strategy of a PSO (Turner, 2020). They stressed more than others the influence project-oriented governance has on achieving strategic goals. The distinction between governance of projects and governance through projects emerges in the analysis of the traditional hierarchical context (Volden & Andersen, 2018). While the first is closer to the analysis of project success factors, the second investigates the final effect of a project-based strategy on users and society (Williams et al., 2010; Samset, 2003). On this relationship, the literature points out that having a strong governance through projects, as well as investing in project management skills, can improve the achievement of broad strategic goals.

4.2.3Performance management

This section concerns the role of performance management approaches in fostering agility. Until today, little empirical evidence on the outcomes of PPPM has been highlighted in the literature on agile in public contexts (Aubry et al., 2011). Greater attention, however, has been devoted to the influence of agile methodologies in project performance, still neglecting the overall impact of incorporating PPPM logics in the organizational strategy. As a result, measuring the impact of projects on organizational performance is still a question not many scholars have attempted to answer (Nolte & Lindenmeier, 2023).

Overall, the cluster of articles on performance measurement and management has directed its magnifying lens towards the analysis of factors and barriers affecting the performance of individual projects, leaving out the link with organizational results (Muller & Martinsuo, 2015; Ruuska & Teigland, 2009; Nanthagopan et al., 2019).

For instance, Patanakul et al. (2016) analyze the key features of large-scale government projects/ programmes to suggest practical recommendations to foster the ability of governments in achieving strategic policy goals. When planning large-scale government projects/programmes, PSOs should overcome traditional project measurement dimensions related to costs, time and scope, paying more attention to intangible benefits and establishing new methodologies for measuring the outcomes achieved. Indeed, an outcome-oriented project performance (Borgonovi et al., 2018) might foster the alignment between project environment and the strategic goals of the PSO. Moreover, with regards to implementation, the consensus of the literature we analyze is that project management processes for managing government projects and project management governance might improve the management of large-scale public projects/programmes.

Other works within the performance management cluster draw attention to the role of the European Union in PSOs projectification (Godenhjelm et al., 2015; Jałocha, 2019). The projectification of Member States and their public sector is necessary to benefit from European funding; it is a key strategic measure for the European Union to get things done. Strategic agility acts as an internal push to more robust project procedures (Godenhjelm et al., 2015).

In summary, public organizations that are more effective in managing projects, aligned with the overall strategic goals, typically formalize project management procedures and invest in civil servants who are experts in project management (Jałocha, 2019). Implicitly, these articles introduce the relevance of supra-national and national performance frameworks towards which strategic purposes must be oriented to foster the integration between projects and strategy performance.

4.2.4Governance

The fourth cluster is well developed and represents a reference for the many authors in the field. Partially, we already had the idea of how much organizational governance is considered a relevant topic, as there is a wide consensus on its role as an enabling factor for implementing projects and strategy effectively in PSOs (Clegg et al., 2002; Volden & Andersen, 2018; Jensen et al., 2018). As was the case for the performance management cluster, the governance of individual projects absorbed greater attention from scholars (Muller et al., 2016, 2017; Lappi & Altonen, 2017).

Governance and agility are two interconnected, sometimes interchangeable, concepts (Mergel et al., 2020). Governance generally refers to “the means for achieving direction, control, and coordination of wholly or partially autonomous individuals or organizations on behalf of interests to which they jointly contribute” (Lynn et al., 2000). Being able to answer complex problems is possible when traditional bureaucratic and hierarchical governance frameworks are integrated by more adaptive and responsive approaches (Janssen & van der Voort, 2016). For this reason, agile solutions are often linked with emergencies and crisis management (Li et al., 2023; Joyce, 2021) while, from a general point of view, agile governance and government contrast with the traditional approaches that follow rigid plans and procedures (Mergel et al., 2021).

Governance is increasingly being studied in connection with strategy implementation (Ansell et al., 2023), organizational performance, and the ability to implement and adapt to change (Crawford & Helm, 2009). Project Management Offices (hereafter PMOs) offer a viable solution to effectively integrate projects and traditional operations (Aubry & Brunet, 2016). A PMO is a dynamic management concept that guides each project to meet the organization’s strategic goals (Sandhu et al., 2019). Following Turner and Miterev (2019), some antecedents can be identified to describe organizational project orientation. First, the intention to be project-oriented is itself a strategic decision that influences the overall strategy of the organization; consequently, project-based work will be one of the primary process adopted by the organization; therefore, it requires that the organization structure should nurture a fit between the processes adopted and the decision to be project-oriented, between processes in the line and on projects, between processes in different functions, and between the strategies adopted and the context (Miterev et al., 2017).

The core concept of projectified governance stems from these reflections (Munck af Rosenschöld, 2019), and can be defined as an arrangement constituted by organizations and individuals across sectors involved in temporary project-driven activities, for the purpose of pursuing selected goals as well as the formal and informal institutions that guide these activities. The theoretical foundation behind projectified governance is twofold: first, it emphasizes the growing function of projects in contemporary governance; second, it explicitly introduces the relationship between projects and permanent organizations. Three models of projectified governance – mechanistic, organic, and adaptive – can be positioned on a continuum in which the focus is on how projects are understood, the link between projects and permanent organizations, and how projects are supposed to change institutions. The adaptive model figures out the most opportunities to foster institutional change to address wicked problems (Munck af Rosenschöld, 2019).

4.2.5Portfolio/programme management

The final organizational driver refers to two different groups of articles: those on portfolio and programme management. In this case, we grouped together two originally autonomous clusters as, usually, projects are organized functionally in programmes (sets of logically connected projects) and/or in portfolios, which group together wide ranges of activities, programmes, and projects under a single category (Roberts & Hamilton Edwards, 2023).

In terms of the quantity of papers belonging to these clusters, as partially anticipated in the first part of the results, we found a significant distinction compared to the project management group, which is significantly wider and more heterogeneous.

A programme consists of related projects, subsidiary programs, and program activities that are managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually (Project Management Institute, 2021). On the other hand, a portfolio can be defined as projects, programs, subsidiary portfolios, and operations managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives. Both these concepts suggest the adoption of PPPM as a viable solution to link the overall strategy to different typologies of activities, including projects and operations (Picciotto, 2020) by simultaneously fostering a new direction for public strategic management towards agility (Roberts & Hamilton Edwards, 2023).

Nonetheless, literature seems to have only occasionally exploited this opportunity (Locatelli et al., 2023). Extant contributions show that portfolio/programme management might allow governments to operationalize and implement their strategies over time (Kim et al., 2016). Still, the literature falls short of applying this perspective to the organizational environment, rather concentrating its effort in looking for the support that PPPM can provide to national and international initiatives and policies (Golini et al., 2015; Heinrich & Choi, 2007; Lannon & Walsh, 2020; Pang & Lee, 2022).

The connection between agile strategies and portfolio/programme management is still an understudied topic in public management literature. In the next section, we seek to answer the call by Roberts & Hamilton Edwards (2023) to connect them with public strategies, to ensure that, compared to what happens in the private sector, portfolio/programme management may improve public value creation through better strategy definition and implementation.

5.Discussion

5.1An updated strategic management framework for PSOs and propositions for further research

In this section, we discuss the salient dimensions, concepts, and research findings emerging from the clusters identified in the literature, and summarize this material into further researchable and testable propositions.

The extant literature reveals that, albeit fragmented and coming from diverse disciplinary and conceptual perspectives, it is possible to derive from our thematic clusters drivers to a more systematic integration of PPPM logics within traditional strategic planning and management models in the public sector, with the potential to foster strategic agility.

The first driver, related to Project Management, incorporates literature from heterogeneous disciplinary perspectives. Agility in the context of individual projects is still the dominant perspective; yet, a few conditions in order to investigate strategic agility emerge, namely the need to balance different project management approaches (both waterfall and agile, among others) to foster strategy implementation; this balance is needed as well in order to serve transparency and citizen trust. The core thematic clusters for our aims appear to be the ones related to Strategic Management, Performance Management and Governance. In the Strategic Management one, the analysis brings to light a key conceptual issue related to strategy implementation, largely neglected in strategy studies: organizational priority of the strategy and the overall complexity of implementation as key dimensions to evaluate the contribution of projects to the success of strategy implementation. A few of the studies in the Strategy cluster also deal with the role of Governance structures as mediators of strategy success - the latter being defined not only as a sum of technical project success indicators, but as broader effects on users and citizens. The Governance driver is central to our analysis as it introduces the topic of projectified governance, or governance through projects as opposed to governance of individual, disconnected projects. This is also relevant for analyzing the relationship between standard operations and innovations brought forward through projects. A similar theme is recurrent as well in terms of the focus of the Performance cluster, where relevant ideas have been formulated in terms of how projects can ensure more direct feedback between performance indicator and strategy formulation, also fostering an outcome orientation, as opposed to standard, technical time-cost-quality measures – especially when an overarching supranational framework is driving project orientation. Finally, the Portfolio/Programme management cluster focuses on aggregations of individual projects, focusing on the role these have beyond the organizational context.

Table 4 summarizes cluster results, by associating papers analyzed to each cluster and systematizing core emergent topics on strategic agility within each cluster.

Table 4

Cluster results and associated references

| Cluster | Core concepts for public sector strategic agility | References |

|---|---|---|

| Project management | Agility in the context of individual projects is still the dominant perspective; yet, a few conditions in order to investigate strategic agility emerge, namely the need to balance different project management approaches (e.g. agile vs waterfall) to foster strategy implementation. | Aerts et al., 2017; Anthopoulos et al., 2016; Damoah & Kumi, 2018; Dittrich et al., 2005; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ghanbaripour et al., 2020; Ghribi et al., 2019; Glyptis et al., 2020; Kavishe et al., 2018; Krogh & Thygesen, 2022; Matinheikki et al., 2021; Melin & Wihlborg, 2018; Osei-Kyei et al., 2017; Padhi & Mohapatra, 2010; Parker et al., 2018; Rose & Grant, 2010; Ruuska & Teigland, 2009 |

| Strategic management | Organizational priority of the strategy, governance structure and the overall complexity of strategy implementation are key dimensions to assess the contribution of projects to the success of strategy implementation. | Beste & Klakegg, 2022; Jensen et al., 2018; Mitchell, 2019; Nilsen & Feiring, 2023; Turner, 2020; Samset, 2003; Söderberg & Liff, 2023; Volden & Andersen, 2018; Young et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2010 |

| Performance management | Projects can foster outcome orientation, as opposed to standard, technical time-cost-quality measures – especially when an overarching supranational framework is driving project orientation. | Aubry & Brunet, 2016; Aubry et al., 201; Godenhjelm et al., 2015; Jałocha, 201; Janka & Kosieradzka, 2019; Muller & Martinsuo, 201; Nanthagopan et al., 201; Patanakul et al., 201; Procca, 2008 |

| Governance | Introduces the topic of projectified governance, or governance through projects as opposed to governance of individual, disconnected projects. | Clegg et al., 2002; Crawford & Helm, 2009; Janssen & van der Voort, 2016; Laine et al., 2020; Lappi & Altonen, 2017; Miterev et al., 2017; Muller et al., 2016; 2017; Munck af Rosenschöld, 2019; Sjöblom & Godenhjelm, 2009; Simard et al., 2018; Turner & Miterev, 2019 |

| Portfolio/programmemanagement | Focuses on aggregations of individual projects, dealing with the role portfolio and programmes have beyond the organizational context, and as interfaces with stakeholder groups. | Golini et al., 2015; Heinrich & Choi, 2007; Kim et al., 2016; Lannon & Walsh, 2020; Locatelli et al., 2023; Pang & Lee, 2022; Picciotto, 2020; Roberts & Hamilton Edwards, 2023 |

In order to answer our second RQ (How can PPPM logics be integrated within traditional Strategic Planning and Management processes in the public sector in order to achieve strategic agility?), in this section we start from the results summarized earlier to develop specific propositions, as theoretical perspectives that challenge received understanding in the literature (George et al., 2023). Rather than condensing the results from organizational drivers described in the literature clusters with a strict 1:1 relationship (one cluster – one proposition), the propositions we offer partly stem from a cross-cluster analysis. This analysis is aimed at identifying converging and recurrent themes across drivers, and how concepts deriving from this (fragmented, but growing) literature can integrate a process-oriented approach to strategic management in the perspective of strategic agility. In this perspective, it is useful to connect and position our propositions in the context of an updated version of arguably the most cited and practically used framework for strategy – the strategic planning and management model by Bryson (2018), introduced earlier in the Background section. In this version of the model, we not only propose a visualization of strategic implementation phase as the domain of interaction between operations and PPPM logics; we also describe how this phase could enhance dialogue and more rapid feedback mechanisms with other, often understudied, sections of the existing model, with the potential to enhance the agility of the whole process.

Figure 5.

An agile strategic planning and management model for public organizations, based on PPPM logics integration. Adapted from Bryson (2018).

The updated model now assumes that the core elements for the start of the strategic planning process (Initial agreement; definition of mandates, mission and values), as well as large parts of the strategic analysis phases (internal and external environment analysis) are standing untouched. Instead, strategic implementation is now described as the result of the interaction between operations, individual projects, programmes, and portfolios. As displayed in the new model, programme and portfolios are a combination of the other two elements, even if there can be a degree of overlap between each of them. Portfolios, for instance, typically combine investment and management decisions encompassing both innovation projects and standard activities. Besides introducing this component, the five propositions we advance describe specific concepts and new feedback mechanisms between the integrated implementation phase and other steps in the strategy process. In Fig. 5, additions to the original Bryson model are indicated with dashed lines (for new feedback mechanisms) and italics (for added/revised concepts or elements in the model). These elements are derived from systematizing and problematizing existing literature, and are intended as the basis of a research agenda on PPPM integration within public strategic management as a driver for strategic agility. Below, the argument for each proposition is supported by a synthesis of the core concepts introduced in the previous section. The five propositions are positioned with their respective number within the updated strategy model.

1. Effective PPPM can drive agility in strategic implementation and management. This is conditional to project management approaches employed being fitting with the priority and complexity levels within the strategic context.

As it emerges from our strategy cluster described earlier, and specifically discussed by Mitchell (2019), a need is apparent for a contingent theory of strategic implementation based on contexts defined by differing levels of initiative priority and implementation complexity. If PPPM is to be seen as an enabler for agile strategic management and implementation, a deeper understanding of how these contextual elements work in practice is necessary. Following Jensen et al. (2018), we posit that the temporary nature of PPPM logics can in principle drive responsiveness within the strategy implementation phase – yet this is conditional with different project approaches being fitting with diverse strategic contexts and levels of complexity. This is visualized in the model by introducing a distinction between the role and specificities of operations vs those of projects, programmes, and portfolios within the implementation phase. Further empirical research is needed to validate this proposition across space and time, unveiling how these conditionalities work in different administrative and policy contexts (Mitchell & Mitchell, 2023).

2. Projectified governance, rather than governance of individual projects, is the preferable approach to project governance in order for PPPM to foster agile strategic implementation. When scaled to portfolio/programme management, this approach can open up avenues for more successful and measurable inter-institutional collaboration.

This proposition stems directly from the analysis of the governance cluster in the previous section. Governance structures (or a strategy-structure relation) are implied by the original Bryson model in the internal environment section; yet, recent years have brought forward significant discussions and new ideas on organizational design in this regard. Projectified governance (or governance through projects, as opposed to governance of projects, as in Williams et al., 2010) has been singled out as an effective approach to ensure the governance regime is aligned with the needs of project and programme management (Munck af Rosenschöld, 2019). The role of projectified governance is visualized in the model as an organizational (or structural) driver, connecting the features of the internal environment with specificities of the formulation and implementation (again, through operations and/or PPPM) phases of strategy. This way, adapted structures of governance should ensure: a. the alignment between PPPM and the strategic planning and management approach employed; b. a more direct feedback system between the strategic formulation phase (in terms of strategic objectives) and how project effectiveness is evaluated; and c. the external representation of projects, leading to increased inter-institutional collaboration (Volden & Andersen, 2018). The design, fit and impact of governance structures on strategy implementation through projects is largely understudied, and we call for a renewed interest in the strategy/structure relationship that could be specifically rebooted by incorporating both the organizational and process roles of PPPM in such analyses.

3. Standard (not mega-)projects can generate agile, shorter term feedback mechanisms between strategic and performance management. The positive effects of PPPM on agile strategic management are mediated by the use of appropriate project performance measures, which should be specific, attainable, comprehensive, and aligned with the overall strategic issues and context (at the national and supranational level) of the organization.

For projects with a shorter time span than the overall strategic management cycle (which is typically at least 3–5 years), there is apparent potential to serve as a driver for more responsive and flexible performance information measurement and use. This is visualized in the revised model through two direct feedback loops between performance indicators and the formulation-implementation phases, which were not explicit in the original version. As it emerges from the arguments discussed in our performance cluster, this can be applied with less ease in the context of megaprojects or large infrastructure projects which typically have a multi-year (even decades) lifespan. In general, the literature suggests moving away from traditional ‘hyper-rational’ approaches to PPPM and from narrow, standard time-cost-quality measures for the evaluation of project success (Young et al., 2012; Patanakul et al., 2016), to performance measures actually enabling the alignment with the overall strategy of PSOs. Such strategic coordination should also involve national (for instance, National Recovery and Resilience Plans) and supranational (for instance, EU strategies or the Sustainable Development Goals) overarching strategies. Still, more reflection on, and application of, the nature and technicalities of such specific and aligned performance measures is needed.

4. Projects can represent more agile and responsive interfaces with stakeholder groups. The overall strategic planning and implementation cycle can benefit from shorter and more direct feedback loops ensured by projects towards stakeholders.

This proposition on the role of PPPM towards stakeholder management stems from cross-cluster contributions, with specific reference to the strategy and project management ones. In public sector projects, there are normally many different stakeholders within and beyond the owner organization who have opinions on the project or can place claims on it (Melin & Wihlborg, 2018). Involvement of various stakeholders, for instance through the use of project boards, is of paramount importance. Project models often recommend or require the use of boards for projects that are large, complex, or have interfaces with other agencies or key stakeholders, in which case these stakeholders should be represented (Volden & Andersen, 2018).

However, several works in the literature we analyze found that many of these boards bear more resemblance to advisory groups and project reference groups than to real steering groups. PPPM logics could, similarly to what has been mentioned in the previous proposition in relation to internal project performance measures, provide a platform for more agile engagement and interaction approaches with stakeholders. We visually represent this feedback interface between PPPM and stakeholder groups in the upper part of the revised model. Empirical case studies are needed to validate these engagement approaches, encompassing different typologies of projects and strategies.

5. There is a tradeoff within the level of integration and permeability between operations/standard activities and PPPM. This tradeoff also influences the probability that project results will be fully internalized and will influence, in turn, standard operations at the end of the project period, thus enabling and reinforcing agile strategic learning.

The final proposition draws from ideas originating across all clusters, with the main ones coming from the strategy and governance drivers, and focuses on what happens within the internal operations-projects ecosystem. In the model, it is represented by assuming there can be a feedback loop between existing operations and the dynamics of new project/programme/portfolio initiatives. Some projects have a strong identity and are largely separated from ordinary activities, while others are more integrated within organizations. These more integrated projects are often not perceived as being very creative and innovative, but there is far less trouble incorporating the lessons learned in the organizations. The dilemma is consequently to balance the potential conflict between radical innovation and well-integrated and anchored implementation (Jensen et al., 2018). Furthermore, an open question relates to which conditions enable projects to become a vector for strategic learning; in other words, for project results to be completely exploited within the organization, leading to change the way in which standard operations are managed, or even to introduce new operations or induce the abandonment of old processes (Munck af Rosenschöld, 2019). In our view, this is probably the most under researched, frontier topic in SM/PPPM integration and one that will likely be of growing importance, in parallel with the need to evaluate the long term impacts and legacy of publicly-owned project based programs.

6.Conclusion

The purpose of this article has been to propose a more systematic integration of PPPM logics within public strategic management processes, in the perspective of fostering strategic agility.

As demonstrated above, research on portfolio, programme and project management in the public sector has so far been fragmented, and has only episodically dialogued with other public administration and management functions. With this paper, we strive to advance the conceptualization of agility within strategic implementation, focusing on the role of projects and their functional aggregations. Finally, we propose a process-driven introduction of PPPM tools and techniques within the strategy discourse of public organizations as a driver for strategic agility.

The five propositions we offer can be tested with different methodologies across contexts, depending on the level of maturity of the literature they are based on. For instance, the first proposition on the configurations through which PPPM can drive agility in strategic implementation and management is supported by a growing, albeit not yet holistic, theoretical background, and could be tested and further validated by case studies in specific administrative contexts. Mitchell and Mitchell (2023) is an excellent example of this, with a focus on the US local government. The same consideration holds for the study of the role and drivers behind projectified governance (proposition 2). Differently, the role of performance management systems (proposition 3) builds on a very mature theoretical basis, grounded in the long-standing tradition of performance measurement and use in the public sector, which has so far been less permeable to project-specific measurement and evaluation approaches. In this case, quantitative studies on the perception and usefulness of PPPM-adjusted tools and techniques, including whether and how projects promote the use of outcome-based performance measures, could be beneficial. Finally, propositions 4 and 5 are instead much less grounded on established empirical bases and could benefit from specific further conceptualization and problematization work, before they are tested in real-life contexts.

As governments face mounting pressures to think and act in a faster and more fluid way, an agile approach to strategy, as enabled by rethinking the role of projects, could bring forth several relevant implications for practitioners, public managers and civil servants (OECD, 2015). Projects, programmes and portfolios should be planned for and enacted strategically, rather than being seen as one-off endeavors based on their temporality and, often, on their being externally funded. Projectification could drive strategic agility by enabling higher reactivity to stakeholder groups’ needs; more systematic coordination and collaboration across governmental units; and inducing a wider use of outcome-based performance measures. This is often the exception, rather than the norm, in the enactment of public projects – yet, it is an increasingly common need, as more resources are managed through supranational coordination mechanisms (such as EU initiatives). NextGenEU initiatives offer an excellent platform for reflection and practical application of this. In many European countries, the enactment of National Recovery and Resilience Plans has induced an unprecedented level of interinstitutional and project-oriented work. At the same time, high priority projects in the digital transformation domain are deeply changing how organizations perceive themselves and operate. Strategic agility enabled by PPPM in this context would also entail tackling the operations/projects dualism in the present (how do they interact in practice?), and in the future (what enables current projects to transform existing operations, or to bring about new processes and procedures?).

This paper is not without limitations. It is based on a selection of papers published only in international academic journals. We found a number of potentially relevant studies published in non-academic journals or elaborated by practitioners, but these practical works fell outside the scope of our review. Consequently, it could be the object of future research to compare these different approaches and complement current findings. Our results and propositions are limited by the intrinsically interpretative nature of any review and by the perimeter of the literature analyzed. While the bibliometric method ensures the reliability of the results more than traditional literature reviews, the interpretation of the outcomes still rests on the authors’ understanding and elaboration. Notwithstanding, this work can be considered a first attempt to review and systematize existing knowledge bridging projects and strategy under the lens of agility, thus suggesting directions for a research agenda.

The practice of PPPM is being adopted more and more in all levels of government globally, even if with still unsatisfactory levels of project success in terms of overall efficiency and effectiveness (Young et al., 2012). We argue that a more structured and theoretically grounded dialogue between the two disciplines can foster a better implementation of strategic management from an agility perspective, and a deeper understanding of the features of portfolio, programme and project management as drivers of this implementation. The adapted model for an agile strategic planning and management cycle can represent a blueprint for empirical observations and studies in the field, aiming to contextualize how it can work in practice across different administrative scenarios.

Notes

1 Available here: https://jcr.clarivate.com/jcr/browse-categories.

References

[1] | (*) indicates papers included in the literature review analysis |

[2] | *Aerts, G., Dooms, M., & Haezendonck, E. ((2017) ). Knowledge transfers and project-based learning in large scale infrastructure development projects: An exploratory and comparative ex-post analysis. International Journal of Project Management, 35: (3), 224-240. |

[3] | Alford, J., & Head, B.W. ((2017) ). Wicked and less wicked problems: A typology and a contingency framework. Policy and Society, 36: (3), 397-413. |

[4] | Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. ((2020) ). The problematizing review: A counterpoint to Elsbach and Van Knippenberg’s argument for integrative reviews. Journal of Management Studies, 57: (6), 1290-1304. |

[5] | Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. ((2023) ). Public administration and politics meet turbulence: The search for robust governance responses. Public Administration, 101: (1), 3-22. |

[6] | *Anthopoulos, L., Reddick, C.G., Giannakidou, I., & Mavridis, N. ((2016) ). Why e-government projects fail? An analysis of the Healthcare. gov website. Government Information Quarterly, 33: (1), 161-173. |

[7] | Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. ((2017) ). bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11: (4), 959-975. |

[8] | *Aubry, M., & Brunet, M. ((2016) ). Organizational design in public administration: Categorization of project management offices. Project Management Journal, 47: (5), 107-129. |

[9] | *Aubry, M., Richer, M.C., Lavoie-Tremblay, M., & Cyr, G. ((2011) ). Pluralism in PMO performance: The case of a PMO dedicated to a major organizational transformation. Project Management Journal, 42: (6), 60-77. |

[10] | Baxter, D., Dacre, N., Dong, H., & Ceylan, S. ((2023) ). Institutional challenges in agile adoption: Evidence from a public sector IT project. Government Information Quarterly, 101858. |

[11] | Beck, K., Beedle, M., Van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., & Thomas, D. ((2001) ). Manifesto for agile software development. |

[12] | *Beste, T., & Klakegg, O.J. ((2022) ). Strategic change towards cost-efficient public construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 40: (4), 372-384. |

[13] | Borgonovi, E., Anessi-Pessina, E., & Bianchi, C. (Eds.). ((2018) ). Outcome-based performance management in the public sector. Cham: Springer International Publishing. |

[14] | Bryson, J.M. ((2018) ). Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement – 5th Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken. |

[15] | Bryson, J., & George, B. ((2020) ). Strategic management in public administration. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. |

[16] | Callon, M., Courtial, J.P., & Laville, F. ((1991) ). Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics, 22: , 155-205. |

[17] | *Clegg, S.R., Pitsis, T.S., Rura-Polley, T., & Marosszeky, M. ((2002) ). Governmentality matters: Designing an alliance culture of inter-organizational collaboration for managing projects. Organization Studies, 23: (3), 317-337. |

[18] | *Crawford, L.H., & Helm, J. ((2009) ). Government and governance: The value of project management in the public sector. Project Management Journal, 40: (1), 73-87. |

[19] | *Damoah, I.S., & Kumi, D.K. ((2018) ). Causes of government construction projects failure in an emerging economy: Evidence from Ghana. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 11: (3), 558-582. |

[20] | *Dittrich, Y., Pries-Heje, J., & Hjort-Madsen, K. ((2005) ). How to make government agile to cope with organizational change. In Business Agility and Information Technology Diffusion: IFIP TC8 WG 8.6 International Working Conference May 8–11, 2005, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, Springer US, pp. 333-351. |

[21] | Doz, Y., Kosonen, M., Virtanen, P., Finnish, T., & Fund, I. ((2018) ). Strategically agile government. Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance, 1-12. |

[22] | *Fernandes, T.M., Gomes, J., & Romão, M. ((2017) ). Investments in E-Government: A benefit management case study. International Journal of Electronic Government Research (IJEGR), 13: (3), 1-17. |

[23] | Fred, M. ((2020) ). Local government projectification in practice – a multiple institutional logic perspective. Local Government Studies, 46: (3), 351-370. |

[24] | Gasik, S. ((2016) ). Are public projects different than projects in other sectors? Preliminary results of empirical research. Procedia Computer Science, 100: , 399-406. |

[25] | George, B. ((2021) ). Successful strategic plan implementation in public organizations: Connecting people, process, and plan (3Ps). Public Administration Review, 81: (4), 793-798. |

[26] | George, B., Andersen, L.B., Hall, J.L., & Pandey, S.K. ((2023) ). Writing impactful reviews to rejuvenate public administration: A framework and recommendations. Public Administration Review, 83: (6), 1517-1527. |

[27] | *Ghanbaripour, A.N., Sher, W., & Yousefi, A. ((2020) ). Critical success factors for subway construction projects-main contractors’ perspectives. International Journal of Construction Management, 20: (3), 177-195. |

[28] | *Ghribi, S., Hudon, P.A., & Mazouz, B. ((2019) ). Risk factors in IT public-private partnership projects. Public Works Management & Policy, 24: (4), 321-343. |

[29] | *Glyptis, L., Christofi, M., Vrontis, D., Del Giudice, M., Dimitriou, S., & Michael, P. ((2020) ). E-Government implementation challenges in small countries: The project manager’s perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152: , 119880. |

[30] | *Godenhjelm, S., Lundin, R.A., & Sjöblom, S. ((2015) ). Projectification in the public sector – the case of the European Union. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 8: (2), 324-348. |

[31] | *Golini, R., Kalchschmidt, M., & Landoni, P. ((2015) ). Adoption of project management practices: The impact on international development projects of non-governmental organizations. International Journal of Project Management, 33: (3), 650-663. |

[32] | Gomes, C.F., Yasin, M.M., & Lisboa, J.V. ((2008) ). Project management in the context of organizational change: The case of the Portuguese public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 21: (6), 573-585. |

[33] | *Heinrich, C.J., & Choi, Y. ((2007) ). Performance-based contracting in social welfare programs. The American Review of Public Administration, 37: (4), 409-435. |

[34] | Howlett, M., Capano, G., & Ramesh, M. ((2018) ). Designing for robustness: Surprise, agility and improvisation in policy design. Policy and Society, 37: (4), 405-421. |