Does agile improve value creation in government?

Abstract

While extensive literature exists on agile practices in private sectors, its application and outcomes in the public sector remain relatively unexplored. In light of recent theoretical debates on how using agile may improve the functioning and results of government organizations, we empirically investigate the outcomes of agile adoption on value creation in public administrations. Drawing on a theoretical framework on value creation in public service delivery, we conduct a comparative qualitative case study involving 19 agile initiatives across the three German government levels. Our findings reveal that agile leads to numerous positive outcomes at both individual (e.g., employee well-being, human-centric leadership, skill development) and organizational levels (e.g., cross-functional collaboration, increased efficiency and transparency). This study contributes to substantiating theoretical claims about agile benefits in government, offering in-depth qualitative insights and theory development.

1.Introduction

Agile practices are becoming increasingly important in the private sector and have fundamentally changed central aspects of software development and project management (Mergel et al., 2020). At its core, agile is about teams organizing and collaborating on their own, a greater focus on customer satisfaction, and continuous improvement. Agile practices are commonly rooted in the “Manifesto for Agile Software Development” (Beck et al., 2001), emphasizing individuals and interactions, customer collaboration, iterative delivery, and adaptability. Various productivity frameworks like Scrum, SAFe, and Kanban draw from these principles, each with its own tools (e.g., product backlogs, daily-standups, sprints) and roles (e.g., product owners and Scrum masters). Mergel (2023, p. 3) defines agile as “a work management ideology with a set of productivity frameworks that support continuous and iterative progress on work tasks by reviewing one’s hypothesis, working in a human-centric way, and encouraging evidence-based learning”. Most frequently, agile practices have been applied in software development projects to replace the traditional waterfall approach where each project phase must be completed before the team can progress to the next phase (Mergel, 2016). The waterfall approach assumes that the project’s requirements remain static throughout the development process (Simonofski et al., 2018). This assumption can lead to inefficiency because it is difficult to react to external and internal changes, changing requirements of users, and an evaluation of the project is only possible at the end of a whole process (Mergel et al., 2020; Simonofski et al., 2018).

However, changing requirements are not specific to software development. Public organizations are nowadays equally facing higher citizen demands and new forms of complex crises (e.g., climate crisis or Covid-19) that the bureaucratic and hierarchically organized public organizations are oftentimes unable to address adequately. Moreover, it has become increasingly common to use projects as a form of organization (Godenhjelm et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2018) and public administrations are more and more frequently turning to agile in project planning. This shift is not only to integrate user feedback and explore solutions to novel problems but also to effectively manage digital product development (Mergel et al., 2020) and the growing number of projects within the public sector. In countries such as the U.S., Germany, and South Korea, there even exist political initiatives to make the entire bureaucratic apparatus more agile, which means that we can expect seeing agile being applied in an increasing number of projects (Mergel, 2023). While agile may be less suited for routine standard operations or implementing predefined strategic plans, as it is mostly focused on creating user-centric innovations (Mergel, 2023), it could still be a promising framework to make public organizations more flexible and adaptive in situations that are still largely unknown, complex, or even chaotic, and where existing work routines are inadequate (Mergel, 2023; Mergel et al., 2020). Empirical evidence from the private sector shows that agile practices lead to many positive outcomes, such as increased project success (Ciric et al., 2019; Serrador & Pinto, 2015), psychological empowerment (Koch et al., 2023; Malik et al., 2021), or higher job satisfaction (Augner & Schermuly, 2023; Kropp et al., 2020; Tripp et al., 2016).

To date, however, research on agile practices in public organizations remains scarce (Mergel, 2016; Mergel et al., 2018; Nuottila et al., 2016; Simonofski et al., 2018). Mergel (2016) and Mergel et al. (2018, 2020) call for answering a whole set of research questions on various aspects of agile in government. The few articles on agile in the public sector indicate that most is known about adoption challenges and there is wide consensus that agile poses significant difficulties for hierarchically organized and bureaucratic public organizations (Baxter et al., 2023; Mergel, 2016, 2023; Mergel et al., 2020; Nuottila et al., 2016; Simonofski et al., 2018). Due to its diverse values, practices, and methods and the lack of universal guideline, agile adoption is often misconstrued (Baxter et al., 2023; Simonofski et al., 2018) or seen as additional workload (Mergel, 2023), requiring adequate training and change management (Simonofski et al., 2018). Moreover, agile’s emphasis on empowerment clashes with hierarchical structures, making it challenging for public managers to delegate decision-making authority (Mergel, 2016). Lastly, it is often difficult to recruit IT talents with specific profiles that have a deep understanding of agile methods (Baxter et al., 2023; Mergel, 2016). At the same time, possible outcomes and changes in value creation remain largely unexplored, leading to the call for more empirical research on outcomes of agile in public settings (Mergel et al., 2020).

Responding to this gap, this study investigates the following research question: how does the introduction of agile affect value creation in public administrations? This question is inspired by recent theoretical debates on what types of value, viewed as key outcomes in public settings, should be created through public service delivery (Osborne et al., 2021), which bodes well for our analysis of how agile values, principles, and methods affect value creation. More specifically, we draw on a theoretical framework on value creation in public service delivery proposed by Cui and Aulton (2023) and employ a comparative case study on 19 public administrations in Germany, where we conducted 23 semi-structured interviews with civil servants which we subsequently analyzed using qualitative methods. Our findings suggest that agile may lead to numerous positive changes in value creation, both at the individual and the organizational level. However, changes in value at the organizational level are only achieved by organizations that have a quite high level of implementation of agile initiatives, whereas organizations with a low level of implementation only see positive value changes at the individual level. As such, our study contributes to a better understanding of agile and its effects on value creation in public settings.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: in the next section, we link agile to our theoretical framework and summarize relevant literature on the topic of agile in private and public settings and elaborate on its respective outcomes. Subsequently, we explain our case selection, data collection and analysis, before presenting our results. Finally, we discuss said results in light of our theory and previous literature and put forward multiple theoretical propositions and, lastly, draw some final conclusions.

2.Theoretical background

2.1Public value creation

The primary goal of public administration is to create public value (Moore, 1994). However, defining public value proves to be a complex task. Public value cannot be reduced to one single dimension or a unique moral philosophy (Van der Wal et al., 2015). Rather, public value is the extent to which public values are satisfied (Bozeman, 2002). Despite numerous attempts to articulate the meaning of public value or to render the concept more concrete through frameworks or measurement scales (Bannister & Connolly, 2014; Meynhardt & Jasinenko, 2020), no single definition of public value has reached hegemonic status (Osborne et al., 2021; Van der Wal et al., 2015). Meynhardt (2009, p. 213) defines public value as “a process leading to perceived changes in qualities of relationships”, while Scupola and Mergel (2022, p. 3) narrow their focus to citizens, defining it as “the citizens’ collective expectations in respect to government and public services”. However, we adopt the perspective of Nabatchi (2018, p. 2), who refers to public value as “appraisal of what is created and sustained by government on behalf of the public”. We follow this definition in our study, not only because it focuses on the outcomes of public service delivery, but also because it acknowledges the government’s role alongside citizens’ expectations.

The concept of public service logic serves as a guiding framework for the deliberate generation of public value, advocating for a multi-dimensional model of value creation (Osborne, 2018). This framework introduces a critical distinction between the production and consumption/use of public services (Osborne et al., 2021). Historically, public value has been construed as contributing solely to the well-being of service users, such as citizens, emphasizing the consumption/use side of public value (Osborne et al., 2021). Public service logic, however, extends public value creation to organizations and wider society which interact during the complex processes of value creation (Trischler & Charles, 2019).

In addition to serving citizens, public administrations must uphold intraorganizational values such as robustness, adaptability, and timeliness (Jørgensen & Bozeman, 2007). Consequently, value creation extends beyond service delivery to encompass the learning and development of both staff and public sector organizations. This involves offering opportunities for self-improvement and fostering a conducive working environment, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of systems and services (Cui & Aulton, 2023; Jørgensen & Bozeman, 2007; Tuurnas, 2015). Our study aims to address this research gap by examining the creation of value through agile practices from the perspective of practitioners in public administration. We seek to explore how agile contributes to public value creation not only in terms of service delivery but also in fostering organizational learning, staff development, and overall improvements within public sector entities.

To achieve this, we draw on a conceptual framework by Cui and Aulton (2023) who explain public value by drawing upon practitioners’ perceptions in local governments projects. Their framework builds upon the established public value categories outlined by Meynhardt (2009) and Meynhardt and Jasinenko (2020), namely moral-ethical, hedonistic-aesthetical, utilitarian-instrumental, and political-social. Cui and Aulton (2023) empirically develop these categories further, explicating the value concept across four dimensions: utilitarian/functional, hedonistic/aesthetical, relational/interactional, and epistemic/instrumental (Table 1). Cui and Aulton’s framework is well-suited for studying value creation through agile in public administration for several reasons. Firstly, the utilitarian/functional dimension allows to assess agile’s impact on the efficiency and functionality of public services. Functional values address core requirements of public service delivery, while utilitarian values go beyond the basic functionalities and extend to broader satisfaction that these services bring to individuals. Secondly, the hedonistic dimension provides insights into how agile contributes to improving well-being. Aesthetic values, like user-friendly interfaces or the design of public spaces, are generally created outside the administration. Thirdly, the relational/interactional dimension enables us to explore how agile facilitates collaboration and stakeholder engagement within public sector projects. Finally, the epistemic/instrumental dimension allows for an examination of how agile contributes to organizational learning and knowledge creation, essential for continuous improvement and adaptation within public administrations.

Table 1

Conceptual framework for the analysis of individual and organizational level outcomes of agile

| Value dimension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utilitarian/ functional | Hedonistic/ aesthetical | Relational/ interactional | Epistemic/ instrumental | |

| Individual level | Direct, and normally monetary benefits for individuals | Personal joy, pleasure, happiness | Improved interpersonal relationships and identity recognition | Personal capacity development |

| Organizational level | Revenue and profitability | Organization as a supportive and uplifting place | Growing organizational network and brand value | Development of techniques, experience, and know-how |

Note: Adapted from Cui and Aulton (2023).

Moreover, Cui and Aulton (2023) distinguish value creation between the individual, organizational and societal level. In this paper, we focus on the individual and organizational level. We do not include the societal level since according to established literature on public policy evaluation (e.g., Sager et al., 2021), public value created at the societal level are impacts rather than outcomes. Impacts take time to materialize, and their effects may not be immediately evident. Since we conducted interviews at a single time-point we may miss the delayed impact, leading to an incomplete understanding of the long-term effects of agile. Without multiple data collection points, it is thus challenging to distinguish between the effects of agile and those of other variables. In the following sections, we will outline in more detail the expectations about the outcomes of agile practices at the individual and organizational level.

2.2Agile and its outcomes

With the exception of Baxter et al. (2023), there is a lack of empirical studies examining the outcomes of agile in public organizations. This gap reflects broader issues in public sector innovation research, where outcomes are often unreported (de Vries et al., 2016). The few cases where outcomes of innovation have been researched, increased effectiveness and efficiency are the most mentioned outcomes (de Vries et al., 2016). Challenges in measuring outcomes in the public sector may stem from its focus on creating public rather than monetary value (Luna-Reyes et al., 2016; Neumann et al., 2019). In the following, we therefore mostly draw on insights from private sector literature, examining individual and then organizational level outcomes.

2.2.1Individual level outcomes

Agile practices yield significant individual-level outcomes, notably psychological empowerment, distinguished by increased team autonomy and agile communication (Grass et al., 2020; Koch et al., 2023; Malik et al., 2021; Tessem, 2014). This empowerment fosters innovative behavior, highlighting the substantial impact of agile on performance and well-being (Malik et al., 2021). Job satisfaction also increases with agile, particularly through collaborative processes that reduce emotional exhaustion and stress levels (Augner & Schermuly, 2023; Koch et al., 2023; Kropp et al., 2020; Tripp et al., 2016). Moreover, internal (e.g., employees consulting the internal IT-support) and external stakeholders benefit from agile, experiencing increased satisfaction across various projects (Gemino et al., 2021; Serrador & Pinto, 2015). Studies, such as Baxter et al. (2023), who investigated the adoption of the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) within the UK Ministry of Defense, reveal positive outcomes of agile adoption within public settings, emphasizing improved relationships and culture, suggesting that agile leads to “greater involvement, awareness, and empathy” (Baxter et al., 2023, p. 9). These individual-level outcomes align with value dimensions in the public sector, such as psychological empowerment and job satisfaction reflecting hedonistic values, and stakeholder satisfaction reflecting utilitarian values (Table 1).

2.2.2Organizational level outcomes

Agile in private companies yield various organizational benefits, including increased performance and project success, such as being efficient and effective regarding timing und budget while achieving the projects’ goals (Ciric et al., 2019; Gemino et al., 2021; Malik et al., 2021; Serrador & Pinto, 2015; Tripp & Armstrong, 2018). Pulakos et al. (2019) found that organizational agility leads to significantly higher financial performance. For instance, SAFe implementation in the UK Ministry of Defense facilitated the successful delivery of project deliverables within set timeframes and budgets due to enhanced collaboration (Baxter et al., 2023). These findings suggest potential benefits of agile in public organizations, such as cost efficiency and increased transparency through incremental deliveries and information exchange (Mergel et al., 2020). Increased project success or performance could lead to functional/utilitarian value, since the taxpayers’ money is spent cautiously, but depending on the definition of success, also lead to relational/interactional value through increased reputation.

3.Data and methods

We employ a positivist approach to investigate how introducing agile affects value creation in public administrations. As described by Cassell et al. (2017, pp. 18–19), ‘positivist qualitative research focuses on searching for, through non-statistical means, regularities, and causal relationships between different elements of the reality, and summarizing identified patterns into generalized findings’. Thus, our study suggests propositions that summarize the identified patterns, a methodological approach aligned with numerous prior qualitative investigations (e.g., Mergel, 2023; Neumann et al., 2022).

Due to the limited prior research on agile in the public sector, we employed a qualitative methodology to develop a nuanced understanding of its value (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). Using a multiple case study research approach following Eisenhardt and Graebner’s framework (2007), we conducted semi-structured interviews with 23 civil servants from 19 public administrations across all government levels in Germany. Each agile initiative was treated as an independent unit of analysis, recognizing the importance of its specific context (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007).

3.1Case selection

According to Mergel (2016, p. 522), “[i]t is important for e-government and digital innovation scholars to conduct country-level studies […] to increase our understanding of agile innovation management”. Heeding this call, we focus on agile initiatives in German public administrations. Comprehensive online research revealed a relatively high prevalence of agile initiatives in German administrations compared to other European countries. This observation can be traced back to the following development. Germany is one of the most rule-oriented bureaucracies in the world (Kuhlmann et al., 2021, p. 3) and there are long-standing debates about administrations being overly focused on producing and following rules and functioning in silos, both of which increasingly inhibited their capacity to solve problems and complicating the digitalization of public services (Kuhlmann et al., 2021, p. 332; Mergel et al., 2021). Therefore, the government’s coalition contract in the period from 2021–2025 states that Germany’s government should promote administrative agility and digitalization by focusing on interdisciplinary and creative solutions, user centricity, and innovation (Koalitionsvertrag 2021, p. 7). Germany therefore represents a highly interesting country to study agile initiatives since the results of this study hold promise not only for Germany but also for less rule-oriented bureaucracies, emphasizing the broader implications of agile implementation.

We employed purposeful theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) to select cases that offer valuable theoretical insights into agile adoption in public settings. Our selection process involved in-depth online research to identify German administrations with agile initiatives or projects. We reviewed event programs, blog posts, newspaper articles, and LinkedIn profiles to identify relevant individuals and administrations. We asked the interviewees whether they knew any other colleagues using agile in other public administrations and continued with this snowballing approach until none of the 23 interviewees were able to point us to any other than the 19 administrations that made up our final sample. These selected cases can be considered early adopters of agile practices within the German public sector. Our investigation led us to conclude that we had successfully identified all instances of agile initiatives among these early adopters. The initiatives are distributed across municipalities of varying sizes, four at the regional-level (Bundesländer), and five federal-level public administrations (Table 2). Notably, we deliberately excluded two cases where the use of agile seemed superficial or for marketing purposes.

We identify unique variables for each case, including 1) government level, 2) department of the agile initiative, 3) position of the interviewed civil servant, and 4) adoption mode (Table 2). Two types of agile initiatives are distinguished: mandatory and voluntary. Mandatory initiatives involve organization- or department-wide implementation (for instance the whole IT-department), ensuring active engagement and awareness among all employees, while voluntary initiatives provide training and coaching without enforcing adoption. For instance, some administrations offer voluntary participation in cross-functional projects utilizing agile practices, with employees contributing willingly alongside their regular responsibilities.

3.2Semi-structured interviews with civil servants

Our selection of civil servants for this study was intentional in its diversity, encompassing a range of perspectives relating to organizational size, department, hierarchical positions, and adoption mode (Table 2). These interviewees, holding key roles in agile initiatives, offered comprehensive insights into various facets of the initiatives. Our interview questionnaire had three sections. The first examined prerequisites needed for agile to create value at different levels of the theoretical model. The second delved into value creation through agile at the individual level, while the third part explored organizational-level value creation. Data collection took place between December 2021 and May 2022, with video call-based interviews lasting approximately one hour. Note that the present study is part of a larger research project on agile government, which includes a second study on agile adoption mechanisms using similar methodology and data from the same dataset.

Table 2

Description of sample

| Level of government | Department | Position | Adoption mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | City – Small | Management/strategy | Head of department | Mandatory |

| B | City – Medium 20 – 100 k | Human resources | Employee in department | Mandatory |

| C | City – Large | Human resources | Head of department | Voluntary |

| D | City – Large | Management/strategy | Head of project | Voluntary |

| E | City – Large | Human resources | Head of project | Voluntary |

| Employee in project | ||||

| F | City – Large | Management/strategy | Head of department | Mandatory |

| G | City – Large | Management/strategy | Head of department | Mandatory |

| H | City – Large | Human resources | Employee in department | Voluntary |

| Head of project | ||||

| I | City – Large | Management/strategy | Head of department | Mandatory |

| J | City – Large | IT-department/digital program | Head of project | Mandatory |

| K | Regional – Federal state public | Other (social department) | Employee in department | Voluntary |

| administration | Employee in department | |||

| L | Regional – Federal state ministry | Management/strategy | State secretary | Voluntary |

| M | Regional – Federal state ministry | IT-department/digital program | Head of project | Mandatory |

| N | Regional – Federal state ministry | IT-department/digital program | Head of project | Mandatory |

| O | National – Ministry | IT-department/digital program | Head of department | Voluntary |

| P | National – Ministry | Management/strategy | Policy officer | Voluntary |

| Senior government official | ||||

| Q | National – Federal office | Other (single project) | Employee in department | Voluntary |

| R | National – Federal office | IT-department/digital program | Head of department | Mandatory |

| S | National – Federal office | IT-department/digital program | Employee in department | Mandatory |

3.3Analytical method

The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using ATLAS.ti software. Employing deductive and inductive coding techniques (Mayring, 2014; Miles et al., 2020), we first coded data based on the four value dimensions from our conceptual framework (Cui & Aulton, 2023). Subsequently, we inductively identified additional and more refined categories within each value dimension. We sorted the categories within each value dimension into individual and organizational level values, continually refining and merging them while diligently screening and reordering to ensure thorough analysis. For more details on the coding, see Appendix A.

To enhance the robustness of our findings, we cross-referenced interview data with official documents from the administrations, such as guidelines or presentation materials, to validate the information obtained. For consistency, one team member conducted the coding, which was subsequently cross-checked by another team member. Finally, a comparative analysis of the cases was undertaken using the networks feature in ATLAS.ti. This feature enables the conceptualization of data by establishing connections between code categories and documents (transcripts for each case) in a visual diagram. By leveraging these networks, we identified patterns, differences, and commonalities based on the level of implementation of agile initiatives (Table 3). This comprehensive approach provided nuanced insights into the dynamics of value generation, facilitating a more informed understanding of the outcomes of agile across the studied cases.

4.Results

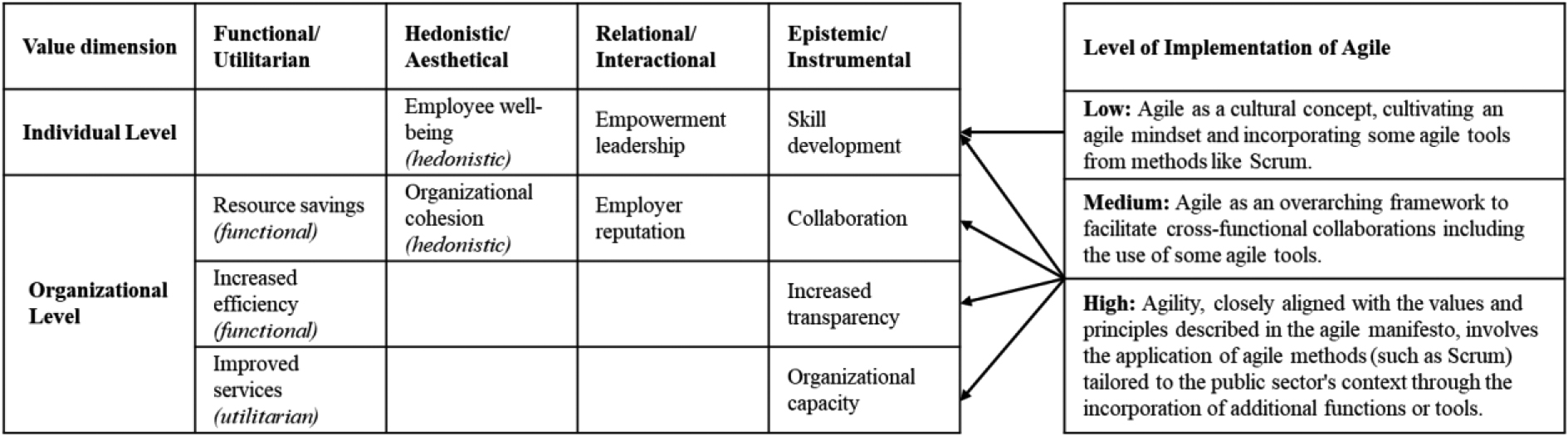

The outcomes of agile encompass a spectrum of changes and benefits, manifesting across the four value dimensions of our conceptual framework. These outcomes materialize at the individual and organizational level. We categorize agile initiatives into three levels of implementation – low, medium, and high (Table 3). Cases with a low level of implementation adopt agile as a cultural concept, characterized by trust, appreciation, feedback, and a positive error culture, emphasizing the agile value ‘individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ (Beck et al., 2001). Although they incorporate some agile tools from methods like Scrum (Table 3), their main focus lies in enhancing interpersonal relationships and making them more meaningful. Cases with a medium implementation level adopt agile as a cross-functional collaboration framework, emphasizing not only an agile mindset, but also values like ‘costumer collaboration’ and principles like ‘building projects around motivated individuals’ (Beck et al., 2001). Cases with a high level of implementation fully embrace agile, including all aspects from the low and medium categories, and utilize established methods like Scrum, closely aligning with the values and principles outlined in the agile manifesto. We suggest that embracing agile as cultural concept and as collaboration framework lays the foundation for organizations to eventually adopt agile methods (high level of implementation), with each stage building upon the other in a sequential approach. The values generated by the application of agile vary depending on the implementation level, which we will discuss in more detail at the end of the results section (Fig. 1).

Table 3

Level of implementation of agile initiatives

| Level of implementation | Description of practices | Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Agile as a cultural concept, cultivating an agile mindset and incorporating some agile tools* from methods like Scrum. | E, L, P, Q |

| Medium | Agile as an overarching framework to facilitate cross-functional collaborations including the use of some agile tools*. | A, C, D, F, G, H, K, O |

| High | Agility, closely aligned with the values and principles described in the agile manifesto, involves the application of agile methods (such as Scrum) tailored to the public sector’s context through the incorporation of additional functions or tools*. | B, I, J, M, N, R, S |

*Kanban board; retrospectives; daily’s; stakeholder analysis; personas; user-stories.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of results.

4.1Functional/utilitarian

Functional or utilitarian values resulting from agile manifest themselves primarily at the organizational level. The first functional value is resource savings, exemplified by the establishment of a topic-related cross-functional structure within the administration. This structural change offered a comprehensive overview of the multitude of projects underway in specific domains, such as mobility or developing the future city center. This newfound transparency allowed for more efficient allocation of resources and cost savings:

“That was really tough, because we realized that we had 106 projects all over the city dealing with the topic of the future city center, which actually can’t work without ending up with conflicting goals and duplicate work.” (G)

In another scenario, an interviewee disclosed that the administration was developing a new communication channel for senior citizens and had prepared a promotional flyer. However, upon consulting the intended users, the seniors, it became evident that the flyer was poorly received:

“We developed a flyer that was not well received at all. If we had printed this flyer 100.000 times, we would have wasted huge amounts of money on things that would have ended up in the trash compactor somewhere. And that triggered another rethink among the team about why it’s worth trying out certain things with our users.” (D)

The second functional value of agile is increased efficiency, leading to potential resource savings, although immediate monetary gains may not always be measurable. This efficiency improvement arises from reduced formality and streamlined communication pathways. Shorter, direct communication reduces reliance on official hierarchical channels. Moreover, agile methods, particularly within frameworks like Scrum, enhance discipline in project workflows, further contributing to efficiency gains:

“With Scrum there is a constraint and a pull behind it. The reliability that when we start a project, it is also followed through. For me, that is one of the biggest advantages compared to before. I’ve been in so many working groups and circles, and I’ve done so much work in vain. It’s a bit of a paradox that we’re introducing such a strong formalism here, i.e., a stronger one than we had before, where the employees know exactly that I won’t be able to get out of here. And that works, and everyone feels it, including the heads of the offices.” (B)

Lastly, a utilitarian value of agile lies in improved services and products. These enhancements go beyond basic needs, enriching experiences for individuals. Our interviewees provided examples such as restructuring of a new city hall, developing a school app, establishing a COVID-19 testing center, integrating a Chatbot into administrative processes, and reengineering procedures in children and youth emergency services. One administration reported digitizing parking permit processes, with 60 percent of applications now submitted online via the portal (end-to-end, including payment).

4.2Hedonistic/aesthetical

Hedonistic values emerge at both individual and organizational levels, although we did not find evidence suggesting that agile generates aesthetic value. At the individual level, agile promotes employee well-being. Interviewees noted that employees are “enthusiastic” and “excited” about the new way of working. Especially cross-functional collaborations facilitated colleague interaction and network-building within the administration. Employees were pleasantly surprised by the number of colleagues sharing their motivation for change, leading to heightened job satisfaction as they felt genuinely valued and heard.

The improved well-being at the individual level translates into heightened organizational cohesion at the organizational level. Agile fosters the formation of new communities within public administrations, increasing trust among colleagues and enhancing team-spirit. These communities mobilize individuals motivated to drive change, empowering them, and reinforcing the belief that their voices are valued and heard:

“Employees tell me that the project culture has changed, that working together is more trusting, that problems are recognized early on, people talk to each other earlier and are in discussion earlier, so I would say that this is a great success.” (J)

Moreover, this improved organizational cohesion has a direct impact on staff retention, as emphasized by one of our interviewees:

“We had employees who really said, ‘wow awesome, this is exactly what I was waiting for, if this hadn’t come, I would be gone now’.” (A)

Indeed, the hedonistic values of employee well-being and organizational cohesion closely align with the subsequent relational/interactional value dimension. Both prioritize pleasure and happiness while emphasizing relational and social dynamics within an organization. Categorizing well-being and cohesion as hedonistic value resonates with the framework’s definition, which also positions organizational cohesion within this category.

4.3Relational/interactional

Within the realm of relational and interactional values, empowerment leadership emerges as a significant value at the individual level. Agile drives a shift in leadership towards empowerment or servant leadership styles. To facilitate this transition, many administrations have implemented leadership training programs:

“For an agile framework, you need managers who support this vision, and that’s why […] we offer sessions on various leadership topics to transport agility to middle management and bring about a change in culture” (A).

The emphasis on cross-functional collaboration and flat hierarchies necessitates leaders to adapt by relinquishing traditional authority, empowering employees to work autonomously. This shift sees employees taking on new responsibilities and feeling empowered to voice ideas without prior manager approval. While this transition posed challenges for many leaders, our interviewees noted a noticeable shift in leadership style:

“You could really see the change in the work and in communication. There was a manager who at some point became much more peaceful and also came by more often, he just passed by at our office door and told us something and also asked things.” (K)

Since we interviewed both employees and leaders, we also explored the perspective of leaders themselves. One leader shared his experience of adapting his behavior:

“I deliberately decided not to go to that meeting where one head of unit usually sits next to the other head of unit. Instead, I encouraged a clerk from my team, responsible for the meeting’s topic, to attend and represent our team.” (O)

Moreover, we identify employer reputation as a value manifesting at the organizational level. Implementing agile allows administrations to shape an image of being an innovative and modern employer. Our interviewees emphasized these new practices during recruitment processes and could thereby attract new candidates. Consequently, these administrations take pride in standing out within the competitive talent acquisition landscape, particularly in the ongoing “war for talent”:

“He (the job applicant) said that he was not sure whether he would have accepted such a role in the administration if this cross-functional working structure would not have existed. He had the impression that it was a strategic framework with which he could work as head of communications.” (G)

4.4Epistemic/instrumental

Epistemic and instrumental values are created at both individual and organizational levels. At the individual level, agile enables skill development. Employees enrich their skill set by utilizing agile tools such as dailies, retrospectives, Kanban boards, personas, or stakeholder analysis. This enhances their portfolio of working methods and practices while strengthening their user-centric thinking. Despite acknowledging the complexity of adopting a genuinely user-centric approach, and that it remains an ongoing challenge for them to fully integrate citizens into the design of public services, some interviewees noted the potential for a change in perspective over time. However, transitioning to this mindset may pose challenges, as employees may require time to adapt to this way of thinking and working:

“The project was exciting because at first, they (the employees) thought, ‘Oh no, and then we have to approach the users […], how is that supposed to work?’ But in the end, they realized that it works and that the entrepreneurs who were interviewed were grateful that they were asked.” (L)

Additionally, another interviewee mentioned a workshop where participants initially struggled to adopt the user perspective. However, through persistence, they eventually developed a deeper understanding, resulting in an improved final product:

“In the end, the product that was created was completely different, and it was not only designed a bit differently, but it solved a completely different problem. Through the user research at the beginning, it was discovered that the problem that they had imagined at the desk was actually not the underlying problem of the affected user group. And for me, that’s the ideal situation, that people on the one hand understand why we’re doing this, and that the product comes out better than they originally thought.” (O)

At the organizational level, the epistemic and instrumental values fostered by agile revolve around capacity building to address present and future challenges.

First, agile fosters new cross-functional and interdepartmental collaborations, essential for successful public service delivery and problem-solving. These collaborations often lead to alternative governance structures, running parallel to the official organization chart. These alternative structures often come equipped with their financial and personnel resources, enabling the facilitation of cross-functional collaborations on matters transcending multiple departments and involve external stakeholders. Guidelines or directives provide a bureaucratic foundation for these structures. Furthermore, two administrations facilitate these collaborations through so-called proxy-product owners within Scrum teams, bridging the divide between agile and non-agile departments, ensuring effective communication and collaboration.

Second, closely linked to the previous outcome, is the increased transparency resulting from agile adoption. There is increased clarity regarding task assignments, minimizing duplication of work. Moreover, transparency encompasses the sharing of information and knowledge. Collaborative structures promote transparent communication within teams and across hierarchy levels:

“By working on these topics cross-functionally, we created a more open and transparent way of communicating – both within the group, who dedicated themselves to these topics, but also with the managers who ultimately have to push projects through, for example of a financial nature. And even when projects failed, it was always clear why they failed.” (K)

Finally, agile enhances overall organizational capacity in several ways. Initially, this is evidenced by skill development, as previously discussed. Additionally, organizations benefit from the accumulation of new knowledge. Given the novelty of agile in public administrations, more than half of the cases sought external support, ranging from one-day workshops conducted by agile coaches to comprehensive consulting mandates spanning several months. Efforts are then made to internalize and retain this knowledge, with employees systematically trained in-house. Six administrations trained agile coaches, pilots, or multiplicators who actively promote agility throughout the administration, serving as agile experts. Furthermore, collaborative cross-functional efforts significantly boost innovation capacity by collecting diverse ideas from various areas, previously untapped, thereby fostering innovation within the organization.

4.5Comparative results

Our data did not reveal any indications that the government level or department influences the types of value created through agile. Table 4 illustrates an equal distribution of adoption modes and levels of implementation across the three government levels, with no observable patterns. However, we did identify a relationship between adoption mode and level of implementation. Instances where agile is mandatory consistently exhibit medium to high implementation levels. Conversely, in cases of voluntary adoption, levels of implementation tend to be low or medium, but never high.

Regarding the influence of the level of implementation of agile initiatives on the type of value created through agile practices (Fig. 1), we firstly observed that cases with a low implementation levels do not create functional or utilitarian value. However, concerning the remaining three value dimensions – hedonistic/aesthetical, relational/interactional, and epistemic/instrumental – a low implementation level of agile only affects the individual level, specifically influencing employee well-being, empowerment leadership, and skill development. In contrast, cases with medium or high implementation levels exhibit effects on all identified values across the four dimensions, impacting both individual and organizational levels (Fig. 1).

Table 4

Level of government: Adoption mode and level of implementation of agile initiatives

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | ||

| Level of government | Municipal level | Regional level | National level | |||||||||||||||||

| Adoption mode | Voluntary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

| Mandatory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

| Level of | Low |

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| implementation | Medium |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||

| High |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

5.Discussion

This study strived to explore how introducing agile affects value creation in public administrations. Our findings indicate that agile positively influences value creation, both at the individual and the organizational level (Cui & Aulton, 2023). At the individual level, we see that regardless of the implementation level, no value is created on the functional/utilitarian dimension, which can be explained by the fact that agile does usually not lead to changes in remuneration in the public sector (Fig. 1) (Cui & Aulton, 2023). On the other hand, again regardless of the implementation level, we see positive changes in value creation on the hedonistic/aesthetical, relational/interactional, and epistemic/instrumental dimensions, namely in employee well-being, empowerment leadership, and skill development, aligning with agile’s emphasis on people-centric values and principles (Baxter et al., 2023; Beck et al., 2001; Mergel et al., 2020).

At the organizational level, cases with a low implementation level showed no value creation across the four dimensions (Fig. 1), likely due to voluntary adoption mode and cultural focus leading to insufficient traction of agile, meaning that it cannot supersede the existing bureaucratic procedures and structures. As a consequence, agile fails to produce tangible outcomes as these cases focus primarily on establishing the cultural prerequisites for using agile (Mergel, 2023). Conversely, cases with medium to high levels of implementation demonstrated significant enhancements in all dimensions, including resource savings, increased efficiency, improved services, better organizational cohesion, employer reputation, and collaboration, as well as increased transparency and organizational capacity. These changes align with crucial public administration performance indicators like cost savings, efficiency, and service quality improvements (Pollitt & Boukaert, 2017). Moreover, they resonate with values universally valued by citizens such as responsiveness and serviceability (Neo et al., 2023).

While our data does not directly assess societal value creation, or in other words the ‘final outcomes’ (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004), insights at individual and organizational levels may indirectly drive them. For instance, improved employee well-being may translate into enhanced service quality and responsiveness, all of which are highly valued by the public (Neo et al., 2023). Similarly, organizational improvements like efficiency and transparency can lead to benefits such as reduced public expenditure and better access to public information. These considerations lead us to the following proposition:

Proposition 1: While cases with a low implementation level of agile initiatives mostly achieve value creation at the individual level (in the hedonistic/aesthetical, relational/interactional, and epistemic/instrumental value dimensions), cases with a medium or high implementation level of agile initiatives are additionally able to create value at the organizational level (in all four value dimensions), mainly by making agile work practices supersede bureaucratic ones.

Our analysis revealed that many of the outcomes are indirect results of improved human-centric leadership and cross-functional collaboration. Collaboration, a core agile principle (emphasized in the cases with high medium/high implementation level), also emerges as a consequential value outcome of agile adoption. Many of these outcomes depend on a high number of changes to the structures, rules, and processes at the internal of an organization, many of which are “antithetical to many typical bureaucratic line organizations” (Mergel et al., 2020, p. 164), requiring comprehensive change management (Kuipers et al., 2014). Effective leadership is crucial in fostering agile value creation (Mergel et al., 2020), requiring leaders to fully back the agile initiatives and a shift towards more empowering (AlMazrouei, 2021) or servant leadership styles (Schwarz et al., 2016). Such shifts enable flat hierarchies and autonomous teams. Many of these aspects link back to the hedonistic and relational/interactional public value dimensions (Cui & Aulton, 2023). This leads us to the following proposition:

Proposition 2: Leaders play a critical role in successfully making agile impact value creation in public organizations for the better. By acting as role models and by empowering their employees, they pave the way for successful cross-functional collaboration.

Our results furthermore highlight agile’s potential for enhancing employee well-being and organizational cohesion, touching upon concepts such as trust, team spirit, and a “one team culture” (Baxter et al., 2023, p. 1; Cui & Aulton, 2023). If we mirror central agile principles such as self-organization, feedback and learning, and cross-functional collaboration with self-determination theory (Deci et al., 1999), it is conceivable that these principles affect concepts like relatedness, autonomy, and competence, all of which are contributing positively to higher-level extrinsic or intrinsic motivation (Cook & Artino, 2016). Forms of motivation that allow for more autonomous regulation, such as intrinsic motivation, in turn, have been shown to lead to positive outcomes in employees and students (Howard et al., 2021), such as commitment, personal success, well-being, lower turnover, less burnouts, and fewer work-family conflicts. This suggests that agile can lead to positive changes in motivation in employees and making organizations “a more supportive and uplifting place” (Cui & Aulton, 2023, p. 17), which is at the core of the hedonistic value dimension. We formulate the following proposition:

Proposition 3: Agile in government introduces changes to the workplace environment that contribute to greater relatedness, autonomy, and competence, which subsequently lead to increased intrinsic motivation and other beneficial employee outcomes.

Our empirical findings support the theoretical assumptions about the benefits of agile in public administration (Mergel, 2016; Mergel et al., 2020) and studies from the private sector that found favorable outcomes of agile in various work contexts (Pulakos et al., 2019; Serrador & Pinto, 2015). However, we need to acknowledge that there still is no universal understanding of agile and our interviews showed that the ways in which agile was adopted into the contexts of the various public administrations analyzed varied substantially, highlighting the need to be cautious about these positive results.

Our study makes at least three contributions to the literature. First, it enriches the theory of agile government by integrating it with the framework on value creation in public service delivery (Cui & Aulton, 2023). Second, through a qualitative comparative case study, we offer detailed insights into the mechanisms driving value changes across the theoretical framework’s two levels and four dimensions. Thirdly, by focusing on Germany, known for its rule-oriented bureaucracy (Kuhlmann et al., 2021, p. 3), we respond the need for country-level studies in understanding agile adoption (Mergel, 2016). The positive outcomes observed in this context suggest potential applicability to less rule-focused environments with even greater ease.

5.1Limitations and future research

This study has four limitations, each suggesting avenues for future research. First, we exclusively interviewed practitioners who have adopted agile practices within public administrations, excluding other relevant stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, and citizens. These stakeholders may offer distinct perspectives on the value generated by agile in the public sector. Additionally, due to constraints on interviewee availability and interviewer resources, many cases were limited to only one interview. Further research is warranted to explore the impact of agile practices on external stakeholders comprehensively. Second, this study provides a snapshot of the situation at a specific point in time, limiting the depth of understanding. Future research should center on longitudinal assessments of agile initiatives to determine the sustainability of outcomes over time. Additionally, employing quantitative methodologies would enable a more rigorous examination of relationships between variables. Thirdly, our study may have an implicit bias towards positive outcomes of agile, as it primarily involved advocates of agile deeply committed to the concept. Future studies should also explore potential pitfalls, “faux-agile” approaches (Mergel, 2023, p. 2), and negative consequences that may arise from agile adoption. Lastly, our study exclusively examines cases from German public administration. Therefore, future research should study other countries and government contexts to gain a comprehensive understanding of how agile varies across different political, cultural, and administrative settings. For example, in centralized Napoleonic countries like France or Belgium, creating value through agile might face challenges due to hierarchical structures, unlike in Nordic countries with strong local governments and accessible administration for citizens (Kuhlmann & Wollmann, 2019, p. 24).

6.Conclusion

In conclusion, our study fills a critical gap in the existing literature by empirically examining positive changes in value creation through the use of agile practices in the public sector. Our findings underscore that the use of agile in public settings can generate a multitude of favorable outcomes, both at the individual and organizational level. Thus, our study provides novel insights into research on agile government by empirically substantiating theoretical assertions regarding the merits of agile practices in public settings. By offering both in-depth qualitative empirical insights and contributing to theory development through linking the concept of agile to a theoretical framework on value creation in public service delivery, our research provides guidance for public organizations looking to adopt agile practices as a means of enhancing their value creation. All in all, we emphasize the potential for agile to drive meaningful and positive change within the public sector.

References

[1] | AlMazrouei, H. ((2021) ). Empowerment leadership as a predictor of expatriates job performance and creative work involvement. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 31: (3), 837-874. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-05-2021-2769. |

[2] | Augner, T., & Schermuly, C.C. ((2023) ). Agile project management and emotional exhaustion: A moderated mediation process. Project Management Journal, 54: (5), 491-507. doi: 10.1177/87569728231151930. |

[3] | Baxter, D., Dacre, N., Dong, H., & Ceylan, S. ((2023) ). Institutional challenges in agile adoption: Evidence from a public sector IT project. Government Information Quarterly, 40: (4), 101858. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2023.101858. |

[4] | Beck, K. ((2001) ). Manifesto for Agile Software Development. 10. |

[5] | Bozeman, B. ((2002) ). Public-value failure: When efficient markets may not do. Public Administration Review, 62: (2), 145-161. doi: 10.1111/0033-3352.00165. |

[6] | Cassell, C., Cunliffe, A.L., & Grandy, G. ((2017) ). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods. SAGE. |

[7] | Ciric, D., Lalic, B., Gracanin, D., Tasic, N., Delic, M., & Medic, N. ((2019) ). Agile vs. traditional approach in project management: Strategies, challenges and reasons to introduce agile. Procedia Manufacturing, 39: , 1407-1414. doi: 10.1016/j.promfg.2020.01.314. |

[8] | Cook, D.A., & Artino, A.R. ((2016) ). Motivation to learn: An overview of contemporary theories. Medical Education, 50: (10), 997-1014. doi: 10.1111/medu.13074. |

[9] | Creswell, J.W., & Creswell, J.D. ((2023) ). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (Sixth edition). SAGE. |

[10] | Cui, T., & Aulton, K. ((2023) ). Conceptualizing the elements of value in public services: Insights from practitioners. Public Management Review, 0: (0), 1-23. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2023.2226676. |

[11] | de Vries, H., Bekkers, V., & Tummers, L. ((2016) ). Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda. Public Administration, 94: (1), 146-166. doi: 10.1111/padm.12209. |

[12] | Deci, E.L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R.M. ((1999) ). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125: (6), 627-668. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627. |

[13] | Eisenhardt, K.M., & Graebner, M.E. ((2007) ). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50: (1), 25-32. doi: 10.5465/amj.2007.24160888. |

[14] | Gemino, A., Horner Reich, B., & Serrador, P.M. ((2021) ). Agile, traditional, and hybrid approaches to project success: Is hybrid a poor second choice? Project Management Journal, 52: (2), 161-175. doi: 10.1177/8756972820973082. |

[15] | Godenhjelm, S., Lundin, R.A., & Sjöblom, S. ((2015) ). Projectification in the public sector – the case of the European Union. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 8: (2), 324-348. doi: 10.1108/IJMPB-05-2014-0049. |

[16] | Grass, A., Backmann, J., & Hoegl, M. ((2020) ). From empowerment dynamics to team adaptability: Exploring and conceptualizing the continuous agile team innovation process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 37: (4), 324-351. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12525. |

[17] | Howard, J.L., Bureau, J.S., Guay, F., Chong, J.X.Y., & Ryan, R.M. ((2021) ). Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis from self-determination theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16: (6), 1300-1323. doi: 10.1177/1745691620966789. |

[18] | Jensen, C., Johansson, S., & Löfström, M. ((2018) ). Policy implementation in the era of accelerating projectification: Synthesizing Matland’s conflict-ambiguity model and research on temporary organizations. Public Policy and Administration, 33: (4), 447-465. doi: 10.1177/0952076717702957. |

[19] | Jørgensen, T.B., & Bozeman, B. ((2007) ). Public values: An inventory. Administration & Society, 39: (3), 354-381. doi: 10.1177/0095399707300703. |

[20] | Koch, J., Drazic, I., & Schermuly, C.C. ((2023) ). The affective, behavioural and cognitive outcomes of agile project management: A preliminary meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 96: (3), 678-706. doi: 10.1111/joop.12429. |

[21] | Kropp, M., Meier, A., Anslow, C., & Biddle, R. ((2020) ). Satisfaction and its correlates in agile software development. Journal of Systems and Software, 164: , 110544. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.110544. |

[22] | Kuhlmann, S., Proeller, I., Schimanke, D., & Ziekow, J. (Eds.). ((2021) ). Public Administration in Germany. Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-53697-8. |

[23] | Kuhlmann, S., & Wollmann, H. ((2019) ). Introduction to Comparative Public Administration: Administrative Systems and Reforms in Europe, Second Edition. Edward Elgar Publishing. |

[24] | Kuipers, B.S., Higgs, M., Kickert, W., Tummers, L., Grandia, J., & Van Der Voet, J. ((2014) ). The management of change in public organizations: A literature review. Public Administration, 92: (1), 1-20. doi: 10.1111/padm.12040. |

[25] | Luna-Reyes, L.F., Picazo-Vela, S., Luna, D.E., & Gil-Garcia, J.R. ((2016) ). Creating Public Value through Digital Government: Lessons on Inter-Organizational Collaboration and Information Technologies. 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), pp. 2840-2849. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2016.356. |

[26] | Malik, M., Sarwar, S., & Orr, S. ((2021) ). Agile practices and performance: Examining the role of psychological empowerment. International Journal of Project Management, 39: (1), 10-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.09.002. |

[27] | Mayring, P. ((2014) ). Qualitative Content Analysis. Klagenfurt. |

[28] | Mergel, I. ((2016) ). Agile innovation management in government: A research agenda. Government Information Quarterly, 33: (3), 516-523. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2016.07.004. |

[29] | Mergel, I. ((2023) ). Social affordances of agile governance. Public Administration Review, n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1111/puar.13787. |

[30] | Mergel, I., Brahimi, A., & Hecht, S. ((2021) ). Agile kompetenzen für die digitalisierung der verwaltung. Innovative Verwaltung, 43: (10), 28-32. doi: 10.1007/s35114-021-0705-x. |

[31] | Mergel, I., Ganapati, S., & Whitford, A.B. ((2020) ). Agile: A New Way of Governing. Public Administration Review, puar.13202. doi: 10.1111/puar.13202. |

[32] | Mergel, I., Gong, Y., & Bertot, J. ((2018) ). Agile government: Systematic literature review and future research. Government Information Quarterly, 35: (2), 291-298. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.04.003. |

[33] | Meynhardt, T. ((2009) ). Public value inside: What is public value creation? International Journal of Public Administration, 32: (3–4), 192-219. doi: 10.1080/01900690902732632. |

[34] | Meynhardt, T., & Jasinenko, A. ((2020) ). Measuring public value: Scale development and construct validation. International Public Management Journal, 24: (2), 222-249. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2020.1829763. |

[35] | Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M., & Saldaña, J. ((2020) ). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (Fourth edition). SAGE. |

[36] | Nabatchi, T. ((2018) ). Public values frames in administration and governance. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 1: (1), 59-72. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvx009. |

[37] | Neo, S., Grimmelikhuijsen, S., & Tummers, L. ((2023) ). Core values for ideal civil servants: Service-oriented, responsive and dedicated. Public Administration Review, 83: (4), 838-862. doi: 10.1111/puar.13583. |

[38] | Neumann, O., Guirguis, K., & Steiner, R. ((2022) ). Exploring artificial intelligence adoption in public organizations: A comparative case study. Public Management Review, 1-27. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2022.2048685. |

[39] | Neumann, O., Matt, C., Hitz-Gamper, B.S., Schmidthuber, L., & Stürmer, M. ((2019) ). Joining forces for public value creation? Exploring collaborative innovation in smart city initiatives. Government Information Quarterly, 36: (4), 101411. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2019.101411. |

[40] | Nuottila, J., Aaltonen, K., & Kujala, J. ((2016) ). Challenges of adopting agile methods in a public organization. IJISPM – International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management, 3: , 65-85. doi: 10.12821/ijispm040304. |

[41] | Osborne, S.P. ((2018) ). From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: Are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation? Public Management Review, 20: (2), 225-231. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2017.1350461. |

[42] | Osborne, S.P., Nasi, G., & Powell, M. ((2021) ). Beyond co-production: Value creation and public services. Public Administration, 99: (4), 641-657. doi: 10.1111/padm.12718. |

[43] | Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. ((2004) ). Results: Through a glass darkly. In C. Pollitt & G. Bouckaert, Public Management Reform, Oxford University PressOxford, pp. 103-142. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780199268481.003.0006. |

[44] | Pollitt, C., & Boukaert, G. ((2017) ). Public management reform: A comparative analysis – into the age of austerity (Fourth edition). Oxford University Press. |

[45] | Pulakos, E.D., Kantrowitz, T., & Schneider, B. ((2019) ). What leads to organizational agility: It’s not what you think. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 71: (4), 305. doi: 10.1037/cpb0000150. |

[46] | Sager, F., Hadorn, S., Balthasar, A., & Mavrot, C. ((2021) ). Politikevaluation. Eine Einführung. Springer. |

[47] | Schwarz, G., Newman, A., Cooper, B., & Eva, N. ((2016) ). Servant leadership and follower job performance: The mediating effect of public service motivation. Public Administration, 94: (4), 1025-1041. doi: 10.1111/padm.12266. |

[48] | Scupola, A., & Mergel, I. ((2022) ). Co-production in digital transformation of public administration and public value creation: The case of Denmark. Government Information Quarterly, 39: (1), 101650. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2021.101650. |

[49] | Serrador, P., & Pinto, J.K. ((2015) ). Does Agile work? – A quantitative analysis of agile project success. International Journal of Project Management, 33: (5), 1040-1051. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.01.006. |

[50] | Simonofski, A., Ayed, H., Vanderose, B., & Snoeck, M. ((2018) ). From Traditional to Agile E-Government Service Development: Starting from Practitioners’ Challenges. Agile E-Government Service Development, 10. |

[51] | Tessem, B. ((2014) ). Individual empowerment of agile and non-agile software developers in small teams. Information and Software Technology, 56: (8), 873-889. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2014.02.005. |

[52] | Tripp, J., & Armstrong, D.J. ((2018) ). Agile methodologies: Organizational adoption motives, tailoring, and performance. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 58: (2), 170-179. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2016.1220240. |

[53] | Tripp, J., Riemenschneider, C., & Thatcher, J. ((2016) ). Job satisfaction in agile development teams: Agile development as work redesign. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17: (4). doi: 10.17705/1jais.00426. |

[54] | Trischler, J., & Charles, M. ((2019) ). The application of a service ecosystems lens to public policy analysis and design: Exploring the frontiers. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 38: (1), 19-35. doi: 10.1177/0743915618818566. |

[55] | Tuurnas, S. ((2015) ). Learning to co-produce? The perspective of public service professionals. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 28: (7), 583-598. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-04-2015-0073. |

[56] | Van der Wal, Z., Nabatchi, T., & de Graaf, G. ((2015) ). From galaxies to universe: A cross-disciplinary review and analysis of public values publications from 1969 to 2012. The American Review of Public Administration, 45: (1), 13-28. doi: 10.1177/0275074013488822. |

Appendices

Appendix

Appendix A. Codebook

| Category | Code | Quotation example |

|---|---|---|

| Functional/ utilitarian | Resource savings (functional) | “That was really tough, because we realized that we had 106 projects all over the city dealing with the topic of the future city center, which actually can’t work without ending up with conflicting goals and duplicate work.” (G) |

| Increased efficiency (functional) | “With Scrum there is a constraint and a pull behind it. The reliability that when we start a project, it is also followed through. For me, that is one of the biggest advantages compared to before. I’ve been in so many working groups and circles, and I’ve done so much work in vain. It’s a bit of a paradox that we’re introducing such a strong formalism here, i.e., a stronger one than we had before, where the employees know exactly that I won’t be able to get out of here. And that works, and everyone feels it, including the heads of the offices.” (B) | |

| Improved services (utilitarian) | “During the coronavirus pandemic, we actually managed to launch a municipal test centre from 0 to 100 thanks to our agile way of working. It became really big, with digital registration and everything, with up to 600 tests a day.” (A) |

| Category | Code | Quotation example |

|---|---|---|

| Hedonistic/aesthetical | Employee well-being (hedonistic) | “The way we used to work together, I would never have got to know my colleague like that, and it would never have gone so well before. Everyone was really enthusiastic.” (B) |

| Organizational cohesion (hedonistic) | “Employees tell me that the project culture has changed, that working together is more trusting, that problems are recognized early on, people talk to each other earlier and are in discussion earlier, so I would say that this is a great success.” (J) | |

| Relational/ interactional | Empowerment leadership | “You could really see the change in the work and in communication. There was a manager who at some point became much more peaceful and also came by more often, he just passed by at our office door and told us something and also asked things.” (K) |

| Employer reputation | “He (the job applicant) said that he was not sure whether he would have accepted such a role in the administration if this cross-functional working structure would not have existed. He had the impression that it was a strategic framework with which he could work as head of communications.” (G) | |

| Epistemic/ instrumental | Skill development | “The project was exciting because at first, they (the employees) thought, ‘Oh no, and then we have to approach the users […], how is that supposed to work?’ But in the end, they realized that it works and that the entrepreneurs who were interviewed were grateful that they were asked.” (L) |

| Collaboration | “Our mayor observed that sometimes issues landed on his desk that could actually be clarified between the departments. Instead, a lot of time was wasted, umpteen statements, just because two department heads disagreed. And it could be resolved much more quickly if you simply sat everyone involved round the table.” (G) | |

| Increased transparency | “By working on these topics cross-functionally, we created a more open and transparent way of communicating – both within the group, who dedicated themselves to these topics, but also with the managers who ultimately have to push projects through, for example of a financial nature. And even when projects failed, it was always clear why they failed.” (K) | |

| Organizational capacity | “We train agile pilots who ultimately have the right know-how, mindset and tools to support project groups, teams and departments in a practical and administrative manner.” (H) |

Authors’ biography

Oliver Neumann is an assistant professor in the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (IDHEAP) at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. He received his PhD in Management at the University of Bern, where he also worked as a postdoctoral researcher in Information Systems. His current research interests include public sector innovation, artificial intelligence, agile government, behavioral public administration, and digital transformation.

Pascale-Catherine Kirklies is a doctoral researcher and graduate assistant in the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (IDHEAP) at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. Her research interests include public sector innovation, agile government, and citizen-state interactions.

Susanne Hadorn is a professor and co-head of the Institute for Nonprofit and Public Management at the FHNW University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland. She completed her PhD at the University of Bern, where she also worked as a policy evaluator. Her current research interests include policy implementation including street-level bureaucracy, policy evaluation, health policy and network governance.