‘Modern talking’: Narratives of agile by German public sector employees

Abstract

Despite growing interest, we lack a clear understanding of how the arguably ambiguous phenomenon of agile is perceived in government practice. This study aims to alleviate this puzzle by investigating how managers and employees in German public sector organisations make sense of agile as a spreading management fashion in the form of narratives. This is important because narratives function as innovation carriers that ultimately influence the manifestations of the concept in organisations. Based on a multi-case study of 31 interviews and 24 responses to a qualitative online survey conducted in 2021 and 2022, we provide insights into what public sector managers, employees and consultants understand (and, more importantly, do not understand) as agile and how they weave it into their existing reality of bureaucratic organisations. We uncover three meta-narratives of agile government, which we label ‘renew’, ‘complement’ and ‘integrate’. In particular, the meta-narratives differ in their positioning of how agile interacts with the characteristics of bureaucratic organisations. Importantly, we also show that agile as a management fad serves as a projection surface for what actors want from a modern and digital organisation. Thus, the vocabulary of agile government within the narratives is inherently linked to other diffusing phenomena such as new work or digitalisation.

1.Introduction

The use of storytelling, and targeted communication has been widely recognised as a key management tool in the public sector (Fernandez & Rainey, 2006). Top management is expected to weave and share compelling narratives about diffusing fashions such as agile government, that persuade middle managers and employees alike to follow their initiatives and ideas (Dalpiaz & Di Stefano, 2018). In parallel, employees and managers who are not convinced by these new ideas will use informal communication channels to find allies to resist them in pursuit of their own goals (Balogun et al., 2015). As implementation progresses, organisations therefore need to respond rhetorically to emerging barriers (Wilson & Mergel, 2022) and adapt their communication and tone when necessary (Nielsen et al., 2023). Communication tools are used to orchestrate different voices on change issues within an organisation (Vaara & Rantakari, 2023). Language and narratives are thus at the heart of organising and making sense of new ideas of change (Whittle et al., 2023).

Consequently, interpretive management scholars have shown increasing interest in narrative analysis in the study of organisational change as a result of management fads (Nielsen et al., 2023; Vaara et al., 2016). A management ‘fad’ or ‘fashion’ can be understood as a label for the diffusion of technologies or ideas that are seen as innovations (Abrahamson, 1991, p. 508). In this regard, some authors have examined the overarching discursive structures of fads, such as New Public Management (Vogel, 2012), artificial intelligence (Guenduez & Mettler, 2023), or their layering (Polzer et al., 2016). At the organisational level, however, the existing literature has primarily examined narrative dynamics that have unfolded alongside classical top-down measures within organisations (Nielsen et al., 2023).

Nevertheless, not all change measures that follow new fads are necessarily well defined and solely implemented top-down (Balogun & Johnson, 2004). Ambiguous management fashions can also be simultaneously adopted by managers and employees at different levels of hierarchy, partially adapted to the organisational context and then discarded or implemented. Different interpretations of the same management fashion can therefore emerge and compete within an organisation. This often happens in the mundane: Managers present their ideas in meetings; employees have kitchen talks about what they want to innovate or maintain. In short, new management trends and ideas usually find their way into organisations rhetorically (Pettit et al., 2023).

Agile government can be seen as one such management ideology that is currently gaining ground (Mergel, 2023) and is likely to be no exception to this dynamic. The lack of conceptual clarity and its inflationary use by management gurus and consultants alike (think for instance about the increasingly diverse agile terminology: agile leadership, human-centricity, Scrum, agile methods, agile mindset, etc.) force practitioners to make sense of what agile means in practice (Roper et al., 2022). Thus, as there arguably is not just one version of agile government, narratives and stories need to be constructed by actors who engage with the notion of agile to then disseminate their vision of an adapted organisational reality (Bartel & Garud, 2009; Vaara et al., 2016). The ambiguous and adaptable language of agile enables employees to apply the idea to individual circumstances, situations, and problems increasing its local legitimacy (Sahlin-Andersson & Wedlin, 2008).

Hence, understanding the formation of agile as an embodying fad within the public sector is crucial. However, we know very little about how agile government is actually talked about within public sector organisations, how it is presented rhetorically by those who introduce it. The literature from both practitioners’ and academics’ perspectives on agile government can therefore run the risk of overemphasising certain elements over others. For example, the theoretical promise that agile leads to a better quality of services following its user-centric development, whereas in practice agile may be more about changing the way a hierarchically organised team communicates or collaborates through the use of agile methods. The different breadth of promises may therefore both understate and exaggerate expectations of the potential effects of the reform. Therefore, in order to ultimately better understand the (lack of) effects of agile, we argue that it is crucial to first understand what agile government actually means to those who make sense of and implement it. Hence, we pose the following research question: Which narratives of agile exist in the public sector and how do they differ?

To address this question, we conduct a thematic and narrative content analysis building upon previous literature (Dalpiaz & Di Stefano, 2018; Zilber, 2007). This paper is based on 31 semi-structured interviews with German public sector employees and consultants involved in the introduction of agile in their respective organisations. The data is complemented by a semi-standardised online survey in which 24 participants answered open-ended questions as well as by desk research on agile in the organisations of the interviewees and respondents.

We observed distinct (meta-)narratives of agile in the German public sector, where the interpretation of (the term) agile is subject to actors’ discretion and action. Analysing individual and composite organisational narratives about agile provides a starting point for uncovering the emergence and embodiment of the fashion in PSOs. First, it provides linguistic and rhetoric cues to what government practitioners might consider relevant components of agile (Loewenstein et al., 2012; Vaara & Fritsch, 2022). Second, revealing how actors construct the intertwining of government structure and stability with features of organisational agile in their narratives enables a better understanding of the complex relationships between these concepts in practice (Bartel & Garud, 2009; McBride et al., 2022). Therefore, narrative analysis can be considered central to the study of (agile) change initiatives, as it forms the basis for understanding this concept and its further implementation, diffusion or, conversely, the resistance to it (Waldorff & Madsen, 2022).

2.State of research – agile government

As in practice, agile as a management fashion is more and more thematised by scholars (Mergel, 2023; Mergel et al., 2021). It is, however, not an entirely new phenomenon. Even before the formulation of the so-called ‘Agile Manifesto’ (Roper et al., 2022), research has discussed agile in connection to organisational flexibility and responsiveness. Nevertheless, the particular embodiments and routines underlying this capability in the form of tools, methods, and structures are increasingly manifold, differing across sectors and areas of applications (Mergel et al., 2021; Proeller & Siegel, 2022). The term agile encompasses several management concepts and characteristics (Harraf et al., 2015) and may therefore already be a product of narratives and fashions: Organisational agility (OA) has been defined mainly as an organisation’s capability to be ‘agile,’ i.e., flexible, and proactively adapt to a changing environment and/or thrive in turbulent circumstances (Harraf et al., 2015; Walter, 2021). It resembles former management concepts such as lean management or total quality management and is linked to the resource- and capability-based view of organisations (Coffin & Tang, 2023; Harraf et al., 2015; Irfan et al., 2019). In general, a wide range of factors, perspectives, and elements seem to drive OA and describe the essence of an agile organisation (Franco et al., 2022): As a result, a consistent conceptualisation of the term is lacking (Walter, 2021; Ylinen, 2021).

Nonetheless, particularly authors interested in its public sector application set out to empirically grasp and theoretically define what agile government is at its core (Mergel, 2016; Mergel et al., 2018). Most recently, Mergel (2023, p. 3) provided the following definition of agile as “a work management ideology with a set of productivity frameworks that support continuous and iterative progress on work tasks by reviewing one’s hypothesis, working in a human-centric way, and encouraging evidence-based learning.” It is seen as best suited to more complex administrative tasks. Where standardised, highly routine processes are in place, agile is presented as unnecessary and without added value (Mergel et al., 2021). Consequently, agile is seen in the literature as a reform effort to render administrative project and crisis management more flexible and goal-oriented. It therefore encompasses both elements of practice and culture. However, empirical work on how public administrations view, adapt to or reject agile, and how it affects them, remains scarce (Mergel, 2023; Soe & Drechsler, 2018). Therefore, we argue that it is important to first examine how agile manifests itself in practice in different organisational realities, beyond its definition. We therefore examine from a narrative perspective how agile as a newly popular management method relates to or is juxtaposed with the administrative context in which it is to be embedded.

3.A narratological perspective

Organisational myths and fashions are rhetorically emphasised as essential by highlighting an inherent key factor that stands in contrast to earlier organisational principles that are seen as obsolete (Kieser, 1997). The structure of the arguments is often as follows: Due to environmental demands and dynamic developments, the fad is presented as a necessary change to stay up to date. At the same time, however, it is linked to existing and legitimate organisational goals and values, such as customer satisfaction, efficiency, transparency or job satisfaction (Heidlund & Sundberg, 2023). A complete rejection of existing cultures and principles therefore does not usually occur. As the predominant mode of change, innovations in the public sector are therefore often based on the existing and accepted status quo (Polzer et al., 2016). In the language underlying the change, this often results in a “clever mixture of simplicity and ambiguity” (Kieser, 1997, p. 58), which allows fashions to be easily adapted to existing circumstances.

In this vein, scholars postulate that the vocabulary of agile, or at least fragments of it, have found their way into the language of management. According to Walter (2021, p. 379), “there is a great interest and widespread use in the parlance [of agile]”. However, the mere appearance of linguistic cues to agile provides little insight into the position of the fashion within the organisational discourse. It is indeed the structural relationship with other elements of organisational language (such as hierarchy, structure, etc.) that gives meaning to the concept in existing organisational life (Loewenstein et al., 2012). How managers narratively weave this vocabulary into the already existing organisational language consequently serves as an indication of their underlying sensemaking processes of what agile means for their organisation (Balogun et al., 2015; Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Weick, 1995).

In accordance with Vaara, et al. (2016, p. 6), organisational narratives are defined here as “temporal, discursive constructions that provide a means for individual, social, and organisational sensemaking and sensegiving”. Importantly, the essence of a narrative lies in its ability to create a coherent plot that relates two autonomous events to an interrelated temporal chain (Bruner, 1991). Gabriel (2004, p. 5) provides an illustrative example: whereas “the king died, then the queen died” does not provide a temporal plot, “the king died, and then the queen died of grief” does. It can therefore be considered a narrative. In these narratives, intentions to act are attributed to the actors involved; they are stylised as driving or hindering forces, acting in a specific temporal and spatial setting (Gabriel, 2004). This allows managers to employ narratives to connect innovations, such as agile, which are not yet a prescribed part of an organisation, to existing ideas about the organisation and its actors (Bartel & Garud, 2009). Narratives can thereby provide coherence while ensuring sufficient ambivalence to account for distinct interests and perceptions of organisational members (Balogun et al., 2015; Bartel & Garud, 2009).

Through this function, narratives gain agency, i.e., they are capable of influencing change (Vaara et al., 2016). In this sense, Sonenshein (2010) has shown that managers’ narratives contain attitudes toward change. They can be progressive, regressive, or stability-oriented. Dalpiaz and di Stefano (2018, p. 689) further show how strategy-makers can construct “a steady influx of captivating narratives” that allow for transformative change in organisations through a balanced blend of novelty and familiarity. This study aims at unveiling existing narratives abuot agile in PSOs in terms of their function to adapt, maintain, diffuse or destruct organisational fashions and fads (Bartel & Garud, 2009) by keeping up the necessary amount of ambiguity and simplicity (Kieser, 1997).

Concurring with previous literature (Bartel & Garud, 2009; Currie & Brown, 2003; Vaara et al., 2016), this study acknowledges that organisational informants do not always present linear, fully-fledged stories; narratives may exist as fragments that only coalesce into full narratives for researchers through the collective input of multiple individuals. Narratives are neither solitary creations by individual actors, but rather products of interactive dialogues, as Czarniawska (2004, p. 5) aptly asserts. As organisations are no monolithic entities, there may be different narrative accounts of the same change initiative, change event, or organisational innovation (Vaara & Rantakari, 2023). This so-called polyphony can result from diverging processes of sensemaking and a lack of coordinated sensegiving (Maitlis, 2005; Vaara & Rantakari, 2023). Consequently, narratives can provoke counternarratives, or exist in parallel without contradictions within or between organisations and their members (Balogun et al., 2015; Zilber, 2007).

For public sector organisations, sensegiving is often manifested in the form of policy or legislation. In the German case, however, there is no overarching policy or executive reform package that includes top-down measures to introduce agile into the German administration. Nevertheless, it is mentioned as a core objective in the coalition agreement of the German government, which increases its legitimacy (SPD et al., 2021). Hence, when agile is implemented locally, in whatever form, PSOs are only bound by their own understanding and sensemaking of what to focus on and, more importantly, what not to focus on in the ambiguous concept of agile. This could potentially lead to a patchwork in the implementation of agile and prevent a coherent vision in the future. In the absence of a master narrative in the form of a policy, constructed narratives at the organisational level become important units of analysis to better understand the manifestation of management fads such as agile on the ground.

4.Methods

4.1Methodological approach

Given our research interest in exploring different narratives of agile in German public sector organisations, we followed a qualitative and interpretative research design using narrative inquiry. In this vein, we used a non-probabilistic, purposive sampling approach (Campbell et al., 2020). The necessary condition for inclusion was that the organisations were involved in some way in the implementation of new organisational practices and/or structures that were formulated under the umbrella of agile and its diverse terminology. As argued above, agile as a management ideology has not been widely implemented in PSOs in Germany (Mergel, 2023). In consequence, we first had to identify organisations that had publicly stated ongoing activities, including the implementation of practices, or structures, that were framed under agile (government). The identification of PSOs thus was based on a pragmatic search for statements that showed an engagement in the topic of agile, using search engines and social media (e.g., LinkedIn) in early 2021. Therefore, our sampling includes elements of convenience sampling (Etikan et al., 2016). The organisations’ communications were rich in form, for instance, press releases about (past) participation in fellowship programmes (e.g., ministries), public reports on actions taken (e.g., one ministry, local governments, innovation labs), or even applications for awards (e.g., at the subnational level). This criterion ensured that the processes of narrative construction about agile among organisational members were occurring at the time of data collection, as measures to implement agile had already been taken (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014). In the process of searching for organisations, we aimed for a variety of organisational forms and administrative levels.

Once identified, we contacted those named as responsible with an initial request for an interview. The positive responses led to a sample of organisations ranging from a large state-owned enterprise to several local innovation labs and core bureaucratic organisations, namely four ministries and four federal agencies, one state authority, and two local authorities in major German cities. Consequently, as stated above, we do not claim a probabilistic sample with claims of generalisability, as we may have missed communications and positive responses were unevenly distributed across the levels. Nevertheless, our research aims to provide a comprehensive picture of narratives of agile government. We argue that the organisations under study constitute an interesting set-up that allows to better understand how agile is perceived and made sense about differently in a federal country like Germany. An overview of the cases is provided in Table 1 and in-depth case reports can be found in Appendix C.

Table 1

Case information1

| Data sources | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | Sample size | Number of interviews | Respondents to semi-standardised online survey | Number of relevant documents | Time of data collection | |

| Federal level (F) | F1–F8 | Ministries (4); federal agencies (4) | 12 | – | – | 2021–2022 |

| State & local level (S) | S1–S3 | State authority (1); local authorities (2) | 5 | 24 | 5 | 2022 |

| Local innovation labs (L) | L1–L10 | Innovation labs (10) | 10 | – | – | 2021–2022 |

| State-owned-enterprise (E) | E1.1–E1.3 | Subsidiaries of a fully stated-owned enterprise (3) | 4 | – | 7 | 2021 |

Following our enquiry, we asked contacts to identify stakeholders who were involved in both the planning and adoption of the measures aimed at introducing what is framed as agile. Here, we followed a snowball sampling approach (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981). This allowed us to gather a diverse picture of agile, as both promoters and resistors were interviewed to minimise a potential pro-innovation bias. In addition to the public managers and employees, we also interviewed consultants (

Data collection methods included semi-structured interviews, a semi-standardised online survey and document analysis. In total, we conducted 31 interviews in all included cases except one of the local authorities, where semi-standardised online surveys (

4.2Data analysis

To understand composite narratives, it is first necessary to understand the dynamics of the organisations and their respective environments. Therefore, we wrote a case description for all cases (see Appendix C). Secondly, following the data analysis strategies of Dalpiaz and Di Stefano (2018), and Zilber (2007), we then combined thematic content analysis and narrative analysis. This involved first sorting the data and working out the individual stories within the cases before analysing the resulting narratives in the second step. The individual steps are described in more detail below.

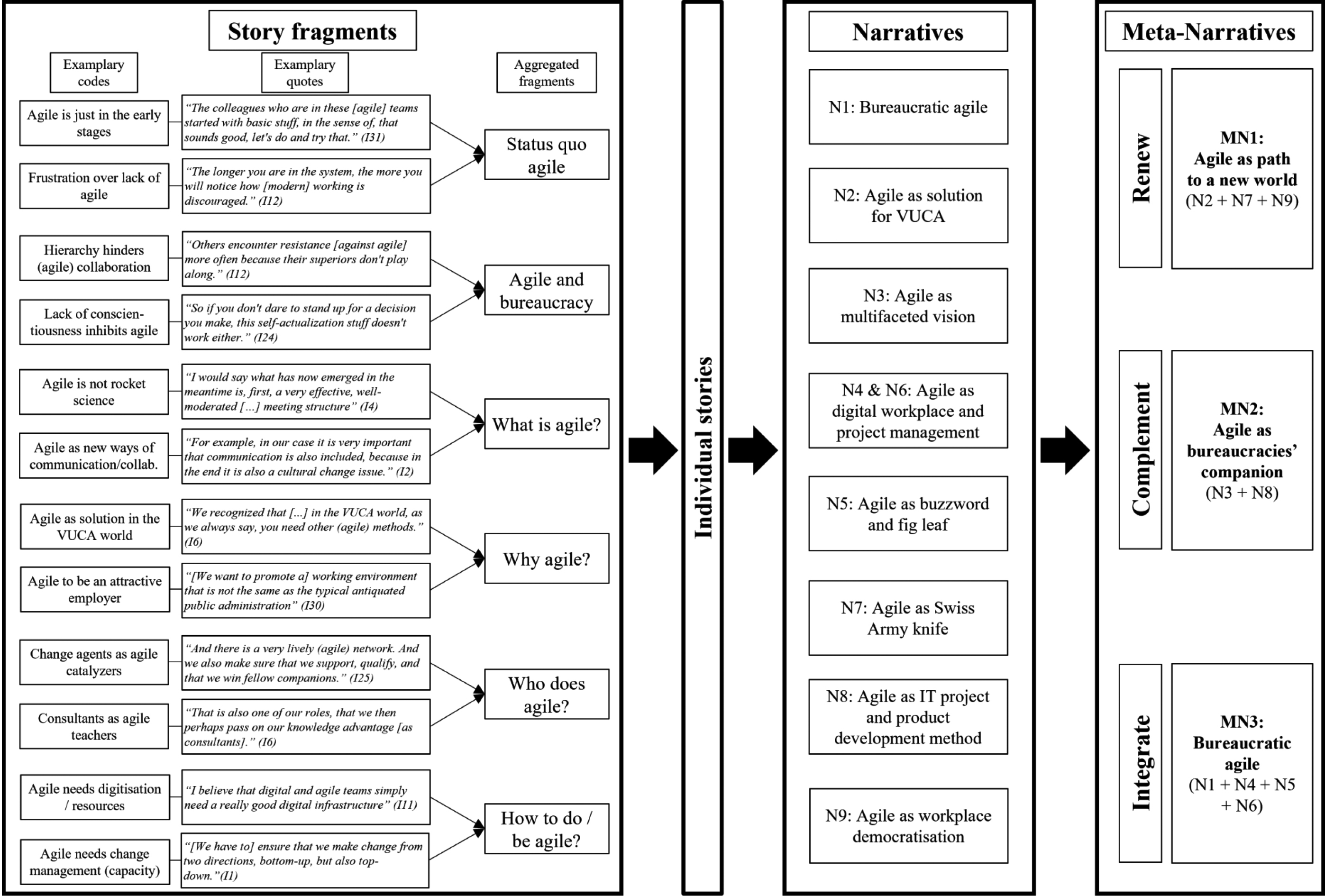

First, inductive thematic analysis was used to reduce the available interview and document data to those text fragments that contain statements about agile. This first step of coding was carried out separately by two of the authors. Upon completion, all authors met and discussed differences in coding. After resolving conflicting decisions, the second step of narrative analysis was carried out jointly by two of the authors. That step was divided into three stages of analysis. First, for each interviewee and each document, the story fragments that appear in the respective text segments were examined inductively. These narrative themes are, for example, “agile as external phenomenon”, “agile is not rocket science”, “agile needs change management (capacity)” (see Appendix D for a complete list of all codes). During this coding process, the authors constantly discussed which individual narratives could be identified for each case. The central narrative elements were then extracted from each narrative. In line with Dalpiaz and Di Stefano (2018), we draw upon Bruner’s (1991) approach of interpretative abstraction: Each story (individual level) and narrative (composites of stories) is structured in terms of the main actors, their quest (which overarching goal is to be achieved), the acts to achieve this goal, the instruments by which this is done and the context in which it is done (see Appendix E for an overview of the individual stories). Next, these individual narratives were combined into composite narratives as described in the coding scheme (see Fig. 1 and Appendix F for a short description). Finally, from these composite narratives, three meta-narratives were derived and discussed among all authors. The following section of findings is organised along the meta-narratives.

Figure 1.

Coding scheme.

5.Results

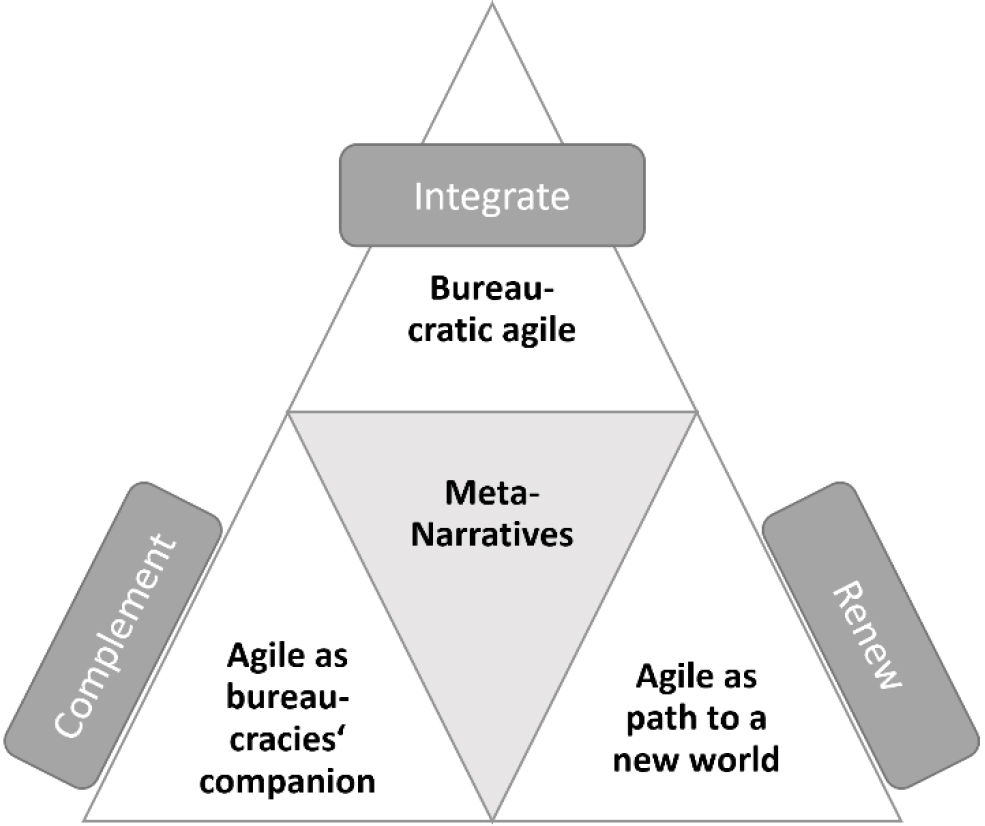

Figure 2.

Meta-narratives.

As a result of our analysis, the identified narratives can be grouped into three meta-narratives (see Fig. 2), which diverge according to the role that agile occupies within the respective organisational reality of the individual storyteller. In the first meta-narrative, ‘renew’, agile is presented as the path to a new world that is to overhaul the existing bureaucratic organisation, which is characterised by hierarchies, top-down decisions, and rigidity, through the democratisation of decision-making, a more agile mindset, and new structures. Agile is presented as the ‘holy grail’ that will allow public organisations to survive in an increasingly complex and uncertain world. In the second meta-narrative, agile is seen more as a ‘complementary’ framework that enhances existing bureaucratic routines by adding structures rather than overturning them. In the form of temporary structures or (project) teams, agile methodology can help administrations to develop solutions for specific tasks (e.g., new digital services, emergency plans, etc.) in a more human-centred or effective way. In the third meta-narrative, agile is ‘integrated’ into the daily routines of administrations. It is presented as reconfiguration of meetings and collaboration across and within departments to be more engaging and less rigid. In essence, agile reflects a more modern, digital, and interactive workplace. It is not a disruption for bureaucratic organisations. Rather, it should improve the way they operate and make them contemporary. In the following each meta-narrative is displayed in depth.

5.1Renew: Agile as the path to a new world (meta-narrative 1)

The individual stories of our first meta-narrative centre around what the interviewees describe as key disadvantageous features of the bureaucratic context, like hierarchies, lacking flexibility in planning, and change. They are described as obstructive for ministries to manage the “rapid changes” of the environment (I1).

Why? Because they have also noticed that their way of working has reached its limits. It’s changing more and more, it’s getting faster and faster, and it takes weeks until there’s a basis for a decision when you climb this staircase. (I3)

Across the interviewees this can be identified as the ultimate quest for agile in a governmental context: “We recognised that […] in the VUCA22 world, as we always say, you need other [agile] methods” (I6). In this case, agile is understood in a more universal, multifunctional way, similar to a Swiss Army knife: “You can actually apply agile […] in any administrative process. And if not within the process, at least it’s the attitude that you take and can take” (I8). Next to the all-encompassing agile toolbox, including methods for projects, meetings and collaboration as well as agile project management frameworks, agile is framed as a mindset. Within the context of an internal dispute, one external put it as follows: “Then I said: You don’t have to do that, that’s the good thing about agile working. You have to be ready and open” (I3).

Agile is therefore understood not only as an improvement of bureaucracy and public administration, but also as a complete renewal of the public sector and its work environment: “Agile in the context of how we did it, it’s about big changes that do a lot to everyone affected” (I26). In this setting consultants, researchers, and other external actors serve as teachers for public servants that identify willing partners and teams within the organisation to collaboratively disseminate and apply agile tools. These teams then legitimate agile methods to convince the resistant and critical bureaucrats of the methods’ necessity. Ultimately, upscaling within the organisations must be driven by top-management via change management as it is beyond the reach of the individual driving actors.

Interestingly, narratives within this context explicitly build on the contrast between (agile) units and the non-agile subsidiaries, especially within the state-owned enterprise. The storytellers presented themselves as ‘agile gurus’ living on an “agile island” (I25) of the ‘blessed’ trying to proclaim their message of agile as workplace democratisation and self-actualisation to those non-agile areas of the organisation. To achieve this quest, they act as a grassroot movement trying to find company and community through networking. In their role as strong advocates of agile, they want to give others the chance to share in their revelation of it. However, as conviction-users, their confidence sometimes turns to incomprehension when they have to cooperate with the non-agile parts of the organisation:

So, we notice again and again that requests are sent to us from the traditional world and that people then think in a very hierarchical way, where we think, for God’s sake, why are they off their rocker? (I25)

The new world of agile government consequently can be characterised as a democratic and digital workplace with less hierarchy, which is becoming more user-centric, flexible, and efficient through the use of agile frameworks and methods.

5.2Complement: Agile as bureaucracies’ companion (meta-narrative 2)

Narratives that can be summarised under this meta-narrative are mainly framed in the classical sense of the ‘Agile Manifesto’. The respondents understand agile as a well-suited method for developing digital products and services for their administrations in an “experimental and iterative manner” (I15). Agile methods should be employed by competent actors in an innovative environment to drive the administration’s digitalisation. This forms the main quest, especially for the interviewees of the innovation labs.

Furthermore, top management stresses a picture of agile as a multifaceted, intertwined change project to position the organisation in a complex environment, anticipating budget restrictions and resource scarcity:

In the VUCA world, there is a correlation of the great challenges of our time […] that we will have to master in the future as an authority. […] Therefore, it is appropriate to see this agency as a laboratory and model to accompany public administration from the world of Max Weber (hierarchical organisations) in a direction that meets the requirements of an integral organisation. (Case S1, Doc1)

Agile here refers to combined measures of project management methods or tools and structural and cultural changes to achieve their postulated quest. Thus, top management addresses a need for change that is driven by public managers, teams, and top management itself. However, the environment in which this change takes place is seen as complementary to the traditional Weberian public administration. As agile takes shape through pilot projects such as “a project management unit” (I10) or additional structures such as separately managed innovation labs where “digital projects can be launched on our own initiative” (I15), the core public administration would only need to be partially transformed to compensate for the public sector’s deficits in service development or project management.

Consequently, the interviewees in the innovation labs draw a sharp contrast between themselves and the non-digitalised and sometimes dysfunctional municipalities that suffer from a lack of resources. From an outsider’s perspective, bureaucracies are portrayed as systems that differ sharply in terms of culture and competences, leading to frustrations in achieving the quest of enabling innovative products and solutions. In contrast, they identify themselves as startup like entities with diverse agile mindsets and a working environment that allows for the implementation of diverse project management methods:

I think it’s great that we’re not part of the administration in the strict sense. I couldn’t work there. That wouldn’t be anything for me, or for our team either. Our projects bounce off the walls of the administration. (I15)

However, the interviewees describe that the main acts and instruments must be applied in collaboration with the administration in order to achieve the goal of digitising the administration through agile methods. Here, the innovation labs fulfil the function of a hybrid product provider. Whereas the product and projects are run outside the organisation to enable agile method adoption, the planning and implementation is an internal administrative task supported by the innovation labs. Nevertheless, the interviewees were rather negative about the ability of administrations to work in an agile way in terms of creative methods of product development, as bureaucracies tend to “detain (actors) in long projects” (I18). While agile thus helps to introduce better digital applications and processes, the method itself does not function within overly rigid bureaucratic structures as it needs “freedom to move” (I13) and can therefore only be seen as complementary to existing structures.

5.3Integrate: Bureaucratic agile (meta-narrative 3)

The third and final meta-narrative presents agile as a novel and desirable way of working in bureaucratic organisations. In contrast to the other narratives, agile thus does not represent a turmoil for bureaucracy, nor is it seen as non-compatible and hence complementary, but as an integral part of modern bureaucratic organisations. Agile is predominantly understood as a management ideology that can improve existing daily routines and practices. The public employees’ understanding of agile predominantly relates to elements of daily communication and (digital) collaboration within and across ministerial teams. Specifically, creative and structuring methods are mentioned here that can change the meeting culture of teams in the direction of improved informative and interactive exchange with more regular feedback rounds. Moreover, vertical and especially horizontal ministerial collaboration should be enabled by a digital workplace, including SharePoint and Kanban boards to avoid lengthy voting rounds and improve “boring [and] dull” (I12) communication across teams.

The quest of the narrative is to integrate this form of agile adapted to the bureaucratic context that is described as lacking digitalisation, with slow and complex processes, and still coined by “superiors who act in the old style, the lord of the manor way” (I12). Agile thus aims at keeping up with modern times, breaking down silos and consequently implementing a modern, digital working style suitable for public authorities: “What I really associate with agile and agile working is project-based collaboration across departments” (I29). One interviewee postulates her motivation for introducing agile is based on the current working mode in her organisation that she describes as “absolute madness“ (I4). Agile is subsequently narrated as an umbrella concept from which useful measures can be drawn as long as they fit the bureaucratic context, as one interviewee points out: “To apply agile methods to projects without having to go straight to Scrum and such. It doesn’t have to go that far” (I12). Hence, agile is seen in essence as an opportunity to promote digitisation and digital tools in a modern (and partly virtual) working environment.

The driving actors in the narrative are mostly individuals, i.e., motivated employees who fight for a modern workplace with their either resistant or supportive colleagues and managers, with the final aim to create a “critical mass” of organisational employees that follow their vision of a modern workplace. These convicted individuals themselves have formed bubbles and networks in which they “stick together in a matter that is not easy” (I13), providing shelter from negative experiences within their teams. This narrative element is similar to what we identified in the first narrative, ‘renew’, namely the focus on the individual as the driving actor. In contrast, interestingly, the role of colleagues as accepting or rejecting actors is more present in the narratives here, as it is about integrating agile into daily routines. The acts and underlying instruments to achieve the quest described are bound to the communication areas and existing collaborations of these individual employees. Particularly, they describe the translation of the agile terminology and methodology within this bureaucratic context:

“Agile” is the allergy word, yes. Yes, so this whole agile language, […] people get upset when it has to be called so hip? […], a Kanban board, why is it called, can’t it be called a decision sheet or something? Then I said, “Okay, you just do things, but don’t say agile anymore.” (I13)

In addition to adapting language and methods by continuous experimentation, respondents cite building digital capacity and skills as a keyway to achieve their quest of bureaucratic agile. Employing digital tools is framed as a central foundation. In the light of creating a modern workplace, agile and digitalisation are inherently connected within this narrative. All in all, the employees suggest that they are currently in a phase of “trial and error” (I30), as they try to make sense of what works and what does not.

Within this overarching narrative, a more critical perspective also emerges, mainly complaining about agile as a fad, while longing for similar goals as the other storytellers. The narrators here see a dysfunctional, bureaucratic organisation that lacks basic digital tools and an appropriate feedback and error culture, as stated in one interview: “I think a better management culture would be necessary. Then there would be no need for new desks or a [fancy] phone booth in an open-plan office” (I28). Hence, they want more pragmatic solutions and a functional work place without any need for fuss. For them agile is not more as remote working in a new workplace that offers sufficient collaboration tools and better methods of communications. Consequently, their actions consist of “nipping change in the bud” (I28) to expose agile as a buzzword used by top management as a fig leaf to cover up the shortcomings of what they see as the current way of working in bureaucratic organisations.

6.Discussion

6.1Modern talking and narratives of agile

In our study, we show that the idea of agile as a management ideology (Mergel, 2023) is understood differently by employees, managers, and externals (such as consultants and researchers) working in, with and for German public sector organisations. With this interpretive work based on a narratological perspective, we thus contribute to the literature on agile government, in particular by adding a critical perspective on how this ambiguous management concept is perceived in practice. Assuming the performativity of language (Loewenstein et al., 2012; MacKenzie et al., 2007), how a concept is talked about locally, affects its subsequent implementation through the dynamic interplay of actors’ acceptance, adoption, and rejection of an idea within its specific context (Waldorff & Madsen, 2022). In the following, we discuss our analytical findings alongside three perspectives on the examined narratives of agile government: the narratives’ attitudes towards agile’s degree of fit with bureaucracy, agile’s connection to digital transformation as well as the implied actors’ constellations.

First, all three narratives convey, to varying degrees, how agile government fits with the narrators’ perceived organisational realities of bureaucratic organisations. For some (‘renew’), agile represents the requisite disruption that challenges and changes bureaucratic functioning and thinking wherever possible and necessary to survive in the VUCA world. For others (‘complement’), it is seen as incompatible with core bureaucracy in the Weberian sense. Hence, in this narrative contrasting the first, bureaucracy is not subject to change. Rather agile, is presented as a very useful and necessary management framework for achieving what bureaucratic routines and practices are designed to constrain: experimental thinking and flexible action. Thus, agile takes on functions in complementary settings, e.g., in laboratories or projects. In the third narrative (‘integrate’), and in stark contrast, agile is presented as a means of achieving a better working culture, including more ‘modern’ collaboration and communication practices. Here, agile government is about changing burdensome internal practices and routines to facilitate and improve working structures, such as meetings or interdepartmental collaboration.

Consequently, we find that agile government, as an arguably ambiguous management fad, provides a rich projection surface for what the narrators hope to improve within their individual realities of bureaucracy. They span all levels of narrative abstraction, from the VUCA world to the way meetings are facilitated. Our analysis highlights that the narratives of agile government function particularly in structural relation to the perceived (mal-)functions of bureaucracy. The solutions (quests) provided by agile as proposed in the narratives are consequently directed at different levels and locations, depending on the extent of the perceived challenges. They range from an abstract focus on changing entire organisations to adapt to the ‘new realities of crisis’ (Janssen & van der Voort, 2020), to adding new temporal structures to be able to work in a more experimental way (Tõnurist et al., 2017), to changing practices and routines to modernise the way of working (Mergel, 2023; Mergel et al., 2021).

This finding that, although to varying degrees, agile in the narratives is always thought of in relation to the core ideas of bureaucratic organisation and also builds on these, is consistent with research on earlier management trends such as NPM (Polzer et al., 2016). In this respect, Heidlund and Sundberg (2023) show that digitalisation strategies also predominantly refer to increasing efficiency as a central objective. To be recognised as an idea and reform, new trends must incorporate and build on certain taken-for-granted ideas to take hold in administrations (Polzer et al., 2016). Moreover, our analysis shows how the practitioners’ narratives resemble the scattered picture of what agile is in government in particular, and how it manifests as depicted in the literature (McBride et al., 2022; Mergel et al., 2018; Soe & Drechsler, 2018). In doing so, we contribute to the literature on agile government with a more structured picture of the diversity of how agile is narrated in practice within the context of bureaucracy.

Surprisingly, citizen-centricity was very rarely mentioned in the narratives, despite being central to agile as an ideology (Mergel, 2023). Improving citizen-centricity appears to be less of a priority for our interviewees. Instead, they present agile methods primarily as a way to change bureaucratic structures and practices, especially in meta-narratives 1 and 3. Consequently, without a focus on agile methods for software production, the user perspective (with citizens as service consumers) plays only a minor role in these narratives. We can only assume that this might be the result of our case selection, as few organisations provide services to citizens at street level. If so, the employees are seen as users for improved agile practices. In meta-narrative 2, user-centricity is indeed presented as a standard element of agile product development that can be pursued outside of traditional administrative structures. Interestingly, however, citizens as users are hardly mentioned.

Building on the literature on sensemaking and sensegiving (Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Vaara et al., 2016), this equivocality (i.e., many voices on the same issue) may pose a key challenge for implementing agile in practice. In the absence of a compelling narrative, agile remains an individually constructed and understood concept, aimed at different problems with different solutions. Or one that is rejected altogether. This is in line with Mergel (2023, p. 13) who explains the consequences of the absence of such change-supporting top-down narratives in the implementation of agile practices as such:

“The absence of artifacts that support the psychological perception of social affordances [of agile] is a major roadblock […]. Colleagues do not have the opportunity […] to socialise with them, by asking questions and trying to draw comparisons to their own organisational or societal problems they aim to solve.”

Second, agile as management fashion is narratively connected to further diffusing fads in the public sector. Particularly one megatrend emerges that we find to be interwoven and at points almost synonymously employed with agile: digitalisation including different forms of remote work. In more detail, we identify three distinct connections of agile and digital change. The first mechanism characterises a digital organisation (understood as remote working, the existence of digital tools and applications, and sufficient IT infrastructure) as the necessary foundation to collaborate and communicate in an agile way. Vice versa, the introduction of agile can secondly function as an enabler of digitalisation if agile working teams increase the demand for the improvement of digital processes, or the implementation of digital collaboration tools. Lastly and thirdly, as mentioned above, the organisational discussions on agile as a broader change-endeavour can serve as a bandwagon for digitalisation efforts. If measures to structurally introduce agile are discussed, acts for digitalisation are automatically included or even seen as less disruptive for some actors, improving agile’s chances to be implemented.

This finding that agile and digital are inherently linked does not seem surprising given that agile, in its most famous approach, is a software development method (McBride et al., 2022). Also, in the early literature on its application in the public sector, it is framed as addressing “the need to innovate digital service delivery in government” (Mergel, 2016, p. 1). However, on closer examination, the analysis shows that agile is not only talked about in this way, reflecting its recent call for implementation in other projects and government routines (Mergel, 2023). Here, therefore, agile can both serve and benefit from digitalisation in government, particularly in relation to a digital organisation, including digitalised back office and project work. Agile working teams utilise and demand digital tools and processes that others in the organisation can then benefit from. However, this requires both technological resources and competencies that need to be harnessed and built (Franco et al., 2022; Tallon & Pinsonneault, 2011). Agile as a management framework, though not a technological reform per se, is thus a central discursive element of the digital transformation discussion, and vice versa.

Third, our analysis shows that the narratives predominantly thrive on a distinction between those who act for the implementation of agile (us) and those who are resistant or neutral to it (them). This distinction seems central to the storytellers. The belief to act for or against an ideology determines which actors are presented as allies and which are still to be convinced. This applies regardless of the background of the interviewees. However, it seems that the more distant the storytellers are from those who are not acting as agile as desired, the more abstract the opposite party (‘the rigid bureaucrats’) becomes. Although the storytellers do not confront public sector employees personally and also positively highlight motivated internal allies, the narratives reflect what we know from the stereotype literature to be prominent features of the portrayal of bureaucrats as inflexible and overly rule-oriented (Dinhof et al., 2023; Willems, 2020). As with what we discussed earlier, particularly in the ‘renew’ and ‘complement’ narratives, at times the bureaucratic mindset is characterised as a hindrance to the agile quest. This resonates with the tones of either the need to renew the bureaucracy or to complement it, as within the bureaucratic organisation staffed with bureaucratic minds, agile cannot unfold its value.

Solely within the ‘integrating’ narrative, which is predominantly shared by the core administrative staff, we examine a rather differentiated picture. The dominant actors consist of a trio: the driving employees or managers, who believe in the value of agile, the either resistant or neutral colleagues, and the respective (team) leadership. The latter is presented as the ‘tip of the scales’ in achieving the goal of being able to sustainably integrate agile into the daily work routine. However, this (rhetorical) guidance seems to be lacking according to the interviewees. Without leadership support, the storytellers argue that they are unable to act due to the lack of a sensegiving process initiated by more powerful actors (Balogun et al., 2015). From the perspective of the literature on narratives, three main tasks emerge for public managers as sensegivers (Maitlis & Lawrence, 2007) if they or their organisational leadership pursues the adoption of agile. First, they function as a sieve for narratives external to the organisation, following the managers’ own interpretation of the phenomenon (Waldorff & Madsen, 2022). As the second function, they are expected to weave a compelling narrative that integrates the local organisational traditions and bureaucratic routines with what is viewed as legitimate from the outside (Day et al., 2023; Logemann et al., 2019; Maitlis & Lawrence, 2007). Lastly, this narrative must be adapted over time to fit the internal discussions (Nielsen et al., 2023). Respectively, the management must be capable of orchestrating the narrative development process, which includes pushing and probably resisting voices over time while ensuring the compliance with the overall strategic goals of the change initiative (Vaara & Rantakari, 2023).

Our study contributes to the discussion of agile government by introducing a narrative perspective. We show three prevalent meta-narratives of agile, which are positioned differently to bureaucracy, and which present different visions of agile public sector organisations. In summary, we show that processes of sensemaking about what agile might be for different actors, are in full swing. However, if not responded to or orchestrated by management, these narrative dynamics could catalyse a fragmented picture of how agile manifests in organisations (Mergel, 2023), or encourage processes of symbolic decoupling (Waldorff & Madsen, 2022).

6.2Limitations and future research

Next, we discuss the limitations of our study as well as directions for future research. Firstly, interpretive narrative analysis puts the researcher in the position of analysing the social realities of the actors under study. Although this is not a limitation per se, the extraction of narratives and their analysis is subject to individual analytical biases, and one may interpret the data differently. In addition, as interviewers, we implicitly convey our personal beliefs about the topic in our questions and responses, which can potentially result in response bias. Nevertheless, our description of the processes of data collection and analysis, and the provision of the questionnaires, as well as the coding scheme aim to increase the reliability of the findings. Future research could therefore critically assess our findings and derive comparative accounts of narratives of agile across different countries (e.g., where agile is part of public policy), areas of administrative action, and over time (Nielsen et al., 2023). Furthermore, as narratives are complex entities that often contain implicit contextual cues that may be overlooked, the narratives derived here may be oversimplified. Using novel methods such as structural topic modelling (Guenduez & Mettler, 2023), future research could extend the findings of this paper by exploring narratives about agile based on larger n-studies.

We do not claim generalisability with the selection of interviewees and their organisations. The main interest of this paper was to provide an in-depth analysis of existing narratives about agile in organisations that have begun to engage differently with this management ideology. In doing so, we face the risk of selection bias, and management scholars should be cautious about extrapolating our findings to other contexts. In organisations where agile is not being applied in any form, the narratives may unfold very differently. Nevertheless, our respondents come from a wide range of public sector organisations, and we provide a first empirical picture of the narrative manifestations of agile. Finally, it is beyond the scope of this paper to draw conclusions about the potential advantages or disadvantages of agile for public sector organisations. Following previous research in this area (Mergel et al., 2021), scholars could explore how organisational performance or public value delivery changes following the introduction of agile measures (McBride et al., 2022), also incorporating the perspective of citizens. However, researchers should be cautious about the individual nature of what agile is or is presented as in the examined case.

7.Conclusion

The purpose of our study was to identify different narratives of agile within the German public sector. In doing so, we aimed to further investigate McBride et al.’s (2022, p. 22) critique that agile is “often applied inappropriately in the government context due to a lack of understanding of what ‘agile’ is and what it is not”. Using a narratological perspective, we show that the governmental context in comparison to private firms is indeed important in how agile is understood and talked about within organisations. Importantly, the narratives identified show that employees often do not distinguish between what agile might be or achieve prescriptively, but make sense of it in their everyday environment (Balogun et al., 2015; Maitlis & Christianson, 2014; Nielsen et al., 2023). We identify three meta-narratives (Renew: agile as path to a new world; Complement: agile as bureaucracies’ companion; Integrate: bureaucratic agile) that are particularly distinct in their structural relationship to the perceived realities of bureaucracy and agile’s function within it. Importantly, agile as an ideology seems to serve as a projection surface for a variety of actors with different normative goals and proposed actions for improving bureaucratic organisations. However, this ambiguity could undermine a coherent implementation of agile within and across organisations if not orchestrated (Vaara & Rantakari, 2023). At its core, however, all narratives employ a kind of ‘modern talking’, using agile vocabulary to legitimise the shift towards modern and digital public sector organisations. Overall, therefore, this article contributes to the discussion of the characteristics of agile as a management fashion (McBride et al., 2022; Roper et al., 2022).

Notes

2 Acronym for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity describing a perceived contemporary development towards a more challenging world (Bennett & Lemoine, 2014).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Caroline Fischer, Oliver Neumann, the anonymous reviewers as well as Isabella Proeller, and the participants of the PSG 1: e-Government of the 2023 European Group for Public Administration conference for their very helpful comments and advice.

Supplementary data

The supplementary files are available to download from http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/IP-230059.

References

[1] | Abrahamson, E. ((1991) ). Managerial fads and fashions: The diffusion and rejection of innovations. The Academy of Management Review, 16: , 586-612. |

[2] | Balogun, J., Bartunek, J.M., & Do, B. ((2015) ). Senior managers’ sensemaking and responses to strategic change. Organization Science, 26: , 960-979. |

[3] | Balogun, J., & Johnson, G. ((2004) ). Organizational restructuring and middle manager sensemaking. The Academy of Management Journal, 47: , 523-549. |

[4] | Bartel, C.A., & Garud, R. ((2009) ). The role of narratives in sustaining organizational innovation. Organization Science, 20: , 107-117. |

[5] | Bennett, N., & Lemoine, G.J. ((2014) , May 1). What a difference a word makes: Understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Business Horizons, 57: , 311-317. Elsevier Ltd. |

[6] | Biernacki, P., & Waldorf, D. ((1981) ). Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociological Methods & Research, 10: , 141-163. |

[7] | Bruner, J. ((1991) ). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18: , 1-21. |

[8] | Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., Walker, K., et al. ((2020) ). Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing, 25: , 652-661. |

[9] | Coffin, N., & Tang, H. ((2023) ). Investigating the strategic interaction between QMS, organisational agility and innovative performance. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 34: , 1096-1107. |

[10] | Currie, G., & Brown, A.D. ((2003) ). A narratological approach to understanding processes of organizing in a UK hospital. Human Relations, 56: , 563-586. |

[11] | Czarniawska, B. ((2004) ). Narratives in Social Science Research. In Narratives in Social Science Research. London: SAGE Publications, Ltd. |

[12] | Dalpiaz, E., & Di Stefano, G. ((2018) ). A universe of stories: Mobilizing narrative practices during transformative change. Strategic Management Journal, 39: , 664-696. |

[13] | Day, L., Balogun, J., & Mayer, M. ((2023) ). Strategic change in a pluralistic context: Change leader sensegiving. Organization Studies, 44: , 1207-1230. |

[14] | Dinhof, K., Neo, S., Bertram, I., Bouwman, R., de Boer, N., Szydlowski, G., Tummers, L., et al. ((2023) ). The threat of appearing lazy, inefficient, and slow? Stereotype threat in the public sector. Public Management Review, 0: , 1-22. |

[15] | Etikan, I., Musa, S.A., & Alkassim, R.S. ((2016) ). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5: , 1-4. |

[16] | Fernandez, S., & Rainey, H.G. ((2006) ). Managing successful organizational change in the public sector. Public Administration Review, 66: , 168-176. |

[17] | Franco, M., Guimarães, J., & Rodrigues, M. ((2022) a). Organisational agility: systematic literature review and future research agenda. Knowledge Management Research and Practice. doi: 10.1080/14778238.2022.2103048. |

[18] | Franco, M., Guimarães, J., & Rodrigues, M. ((2022) b). Organisational agility: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 21: , 1021-1038. |

[19] | Gabriel, Y. ((2004) ). Narratives, stories, texts. In D. Grant, C. Hardy, C. Oswick, & L.L. Putnam (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Organizational Discourse, pp. 61-79. London: Sage. |

[20] | Guenduez, A.A., & Mettler, T. ((2023) ). Strategically constructed narratives on artificial intelligence: What stories are told in governmental artificial intelligence policies? Government Information Quarterly, 40: . |

[21] | Harraf, A., Wanasika, I., Tate, K., & Talbott, K. ((2015) ). Organizational agility. Journal of Applied Business Research, 31: , 675-686. |

[22] | Heidlund, M., & Sundberg, L. ((2023) ). What is the value of digitalization? Strategic narratives in local government. Information Polity, 1-17. |

[23] | Irfan, M., Wang, M., & Akhtar, N. ((2019) ). Impact of IT capabilities on supply chain capabilities and organizational agility: A dynamic capability view. Operations Management Research, 12: , 113-128. |

[24] | Janssen, M., & van der Voort, H. ((2020) ). Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Information Management, 55: , 102180-102180. |

[25] | Kieser, A. ((1996) ). Moden & mythen des organisierens. Die Betriebswirtschaft, 56: , 21-39. |

[26] | Kieser, A. ((1997) ). Rhetoric and myth in management fashion. Organization, 4: , 49-74. |

[27] | Loewenstein, J., Ocasio, W., & Jones, C. ((2012) ). Vocabularies and vocabulary structure: A new approach linking categories, practices, and institutions. Academy of Management Annals, 6: , 41-86. |

[28] | Logemann, M., Piekkari, R., & Cornelissen, J. ((2019) ). The sense of it all: Framing and narratives in sensegiving about a strategic change. Long Range Planning, 52: , 101852-101852. |

[29] | MacKenzie, D., Muniesa, F., & Siu, L. ((2007) ). Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics. In Do Economists Make Markets? Princeton University Press. |

[30] | Maitlis, S. ((2005) ). The social processes of organizational sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 48: , 21-49. |

[31] | Maitlis, S., & Christianson, M. ((2014) ). Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. Academy of Management Annals, 8: , 57-125. |

[32] | Maitlis, S., & Lawrence, T.B. ((2007) ). Triggers and enablers of sensegiving in organizations. The Academy of Management Journal, 50: , 57-84. |

[33] | McBride, K., Kupi, M., & Bryson, J.J. ((2022) ). Untangling Agile Government: On the dual necessities of structure and agility. In Agile Government: Emerging Perspectives In Public Management, pp. 21-34. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. |

[34] | Mergel, I. ((2016) ). Agile innovation management in government: A research agenda. Government Information Quarterly, 33: , 516-523. |

[35] | Mergel, I. ((2023) ). Social affordances of agile governance. Public Administration Review, 0: , 1-16. |

[36] | Mergel, I., Ganapati, S., & Whitford, A.B. ((2021) ). Agile: A new way of governing. Public Administration Review, 81: , 161-165. |

[37] | Mergel, I., Gong, Y., & Bertot, J. ((2018) ). Agile government: Systematic literature review and future research. Government Information Quarterly, 35: , 291-298. |

[38] | Nielsen, J.A., Elmholdt, K.T., & Noesgaard, M.S. ((2023) ). Leading digital transformation: A narrative perspective. Public Administration Review, 0: , 1-15. |

[39] | Pettit, K.L., Balogun, J., & Bennett, M. ((2023) ). Transforming visions into actions: Strategic change as a future-making process. Organization Studies, 017084062311718. |

[40] | Polzer, T., Meyer, R.E., Hollerer, M.A., & Seiwald, J. ((2016) ). Institutional hybridity in public sector reform: Replacement, blending, or layering of administrative paradigms. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 48B: , 69-99. |

[41] | Proeller, I., & Siegel, J. ((2022) ). ‘Tools’ in Public Management: How Efficiency and Effectiveness are Thought to be Controlled. In K. Schedler (Ed.), Elgar Encyclopedia of Public Management, pp. 186-190. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. |

[42] | Roper, I., Prouska, R., & Chatrakul Na Ayudhya, U. ((2022) ). The rhetorics of ‘agile’ and the practices of ‘agile working’: Consequences for the worker experience and uncertain implications for HR practice. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33: , 4440-4467. |

[43] | Sahlin-Andersson, K., & Wedlin, L. ((2008) ). Circulating ideas: imitation, translation and editing. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T.B. Lawrence, & R.E. Meyer (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism, pp. 218-242. London: Sage. |

[44] | Soe, R.-M., & Drechsler, W. ((2018) ). Agile local governments: Experimentation before implementation. Government Information Quarterly, 35: , 323-335. |

[45] | Sonenshein, S. ((2010) ). We’re changing – or are we? untangling the role of progressive, regressive, and stability narratives during strategic change implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 53: , 477-512. |

[46] | SPD, Die Grünen, & FDP. ((2021) ). Mehr Fortschritt wagen – Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit, Koalitionsvertrag 2021–2025. Berlin. Retrieved from https://www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertrag_2021-2025.pdf. |

[47] | Tallon, P.P., & Pinsonneault, A. ((2011) ). Competing perspectives on the link between strategic information technology alignment and organizational agility: Insights from a mediation model. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 35: , 463-486. |

[48] | Tõnurist, P., Kattel, R., & Lember, V. ((2017) ). Innovation labs in the public sector: What they are and what they do? Public Management Review, 19: , 1455-1479. |

[49] | Vaara, E., & Fritsch, L. ((2022) ). Strategy as language and communication: Theoretical and methodological advances and avenues for the future in strategy process and practice research. Strategic Management Journal, 43: , 1170-1181. |

[50] | Vaara, E., & Rantakari, A. ((2023) ). How orchestration both generates and reduces polyphony in narrative strategy-making. Organization Studies, 0: , 1-27. |

[51] | Vaara, E., Sonenshein, S., & Boje, D. ((2016) ). Narratives as sources of stability and change in organizations: Approaches and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 10: , 495-560. |

[52] | Vogel, R. ((2012) ). Framing and counter-framing new public management: The case of germany. Public Administration, 90: , 370-392. |

[53] | Waldorff, S.B., & Madsen, M.H. ((2022) ). Translating to Maintain Existing Practices: Micro-tactics in the implementation of a new management concept. Organization Studies, 017084062211124. |

[54] | Walter, A.T. ((2021) ). Organizational agility: Ill-defined and somewhat confusing? A systematic literature review and conceptualization. Management Review Quarterly, 71: , 343-391. |

[55] | Weick, K.E. ((1995) ). Sensemaking in organizations (Vol. 3). Sage. |

[56] | Whittle, A., Vaara, E., & Maitlis, S. ((2023) ). The role of language in organizational sensemaking: An integrative theoretical framework and an agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 49: , 1807-1840. |

[57] | Willems, J. ((2020) ). Public servant stereotypes: It is not (at) all about being lazy, greedy and corrupt. Public Administration, 98: , 807-823. |

[58] | Wilson, C., & Mergel, I. ((2022) ). Overcoming barriers to digital government: Mapping the strategies of digital champions. Government Information Quarterly, 39: , 101681-101681. |

[59] | Ylinen, M. ((2021) ). Incorporating agile practices in public sector IT management: A nudge toward adaptive governance. Information Polity, 26: , 251-271. |

[60] | Zilber, T.B. ((2007) ). Stories and the discursive dynamics of institutional entrepreneurship: The case of Israeli high-tech after the bubble. Organization Studies, 28: , 1035-1054. |

Appendices

Authors’ biography

Jakob Kühler is a research associate and doctoral student in the DFG project DIGILOG at the Chair of Public and Nonprofit Management. He is interested in research on digitalisation, sensemaking, narratives, and institutional theory. He studied “Public Governance across Borders” at the University of Twente and the University of Münster and completed his master’s degree in “National and International Administration” at the University of Potsdam.

Nicolas Drathschmidt is a research and teaching associate at the Chair of Public and Nonprofit Management at the University of Potsdam. He is interested in research on red tape and digitisation, bureaucracy, as well as behavioural public administration. He studied “Political Science, Administration and Organization” at the University of Potsdam. He also completed his master’s degree in “Administrative Sciences” at the University of Potsdam.

Daniela Großmann is a research and teaching associate at the Chair of Public and Nonprofit Management at the University of Potsdam. Her research interests include public sector innovation, resource dependency, and digital transformation. She studied “Political Science, Administration and Organization” and completed her master’s degree in “Administrative Sciences” at the University of Potsdam.