Development of e-government in the field of social services and benefits: Evidence from Romania

Abstract

This paper investigates from a comparative perspective the development of e-government in the field of social services and benefits for the case of Romania.

The analysis takes into account the global context of the COVID-19 pandemic, where there has been an increased usage of ICT technology and new circumstances for delivering social services. Therefore, the analysis will examine whether there has been an impetus for developing e-government social services in Romania. Research questions address whether there is a difference in the availability of electronic delivery of social services and benefits during the pandemic period and examine potential differences between types of services and benefits, counties/regions and types of institutions (central, regional/county, local – mayoralties/urban and rural municipalities). Additionally, informative procedures available in 2021 are examined. The analysis revealed that there is no standardized set of available electronic procedures from similar institutions. The most eloquent case is the one of deconcentrated institutions, County Agencies for Payments and Social Inspection, which are subordinated to the same central level institution – Ministry of Labor. However, the study outlines a development on the total number of available procedures for social services and benefits. Significant improvements are needed to standardize the same procedures from different institutions, irrespective of their type of affiliated territory.

1.Introduction

This paper investigates from a comparative perspective the development of e-government in the field of social services and benefits for the case of Romania. The analysis takes into account the global context of the COVID-19 pandemic, where there has been an increased usage of ICT technology and new circumstances for delivering social services. Therefore, the analysis will examine which factors influence the development of e-government services in social protection area in Romania during the pandemic crisis. Additional research questions examine whether there has been a development in availability of electronic procedures in 2021 compared to 2020, for the field of social services and benefits. Subsequent research topics related to differentiation by location, type of institution, and procedure emerge. Moreover, informative procedures available in 2021 are examined.

The contribution of this paper is both conceptual and empirical. It primarily deals with the transaction role of e-government as a way to improve the delivery of public services and engage with citizens. By focusing on social services, the paper highlights key achievements provided on the supply side for increased availability of various services and benefits for vulnerable groups. Consequently, the focus of the study highlights the purpose of e-government as a form of smart government, which is inclusive, integrated and citizen-centered. The longitudinal approach can serve as a basis for comparison within the same national context, extending for the future the timeframe, as well as with other national contexts, by using the same overall methodological framework. Social services and benefits included in the analysis cover several (vulnerable) groups: children11 (and children with disabilities), people at-risk-of-poverty and social exclusion, persons with disabilities (irrespective of disability),22 and other specific groups in relation to employment services.33

This paper is structured as follows. The second section introduces the theoretical background relevant to the work, and the third section describes the context of the research. In the fourth section, there is a presentation of results/findings grouped by type of procedure. Finally, the last sections integrate conclusions derived from this work into a discussion within the context of existing research and future work.

2.Theoretical background

2.1Stages of e-government development

In this article, we refer to e-government as the electronic delivery of information and services to citizens, business, and public administration (Lee et al., 2008). Digitalisation of social services has already been studied regarding its overall importance as well as on the consequences derived from an increased interplay between civil servants and technology (Ranerup & Henriksen, 2020), more generally on the divisions of functions between man and machine (Braun, 2021), or, accessibility of web pages, in the sense of enabling people with disability to access IT (Gambino et al., 2016). The subject of digitalisation of public services has also been put in relation to its impact on the quality of life of rural residents (Fahmi & Sari, 2020). Moreover, a systematic desk review of antecedents of e-government success across three stages identifies three key categories of factors: (i) e-information – population size (large), Internet and ICT infrastructure, socioeconomic characteristics (education), and citizen demand; (ii) institutional factors – political competition, political support, democratic institutions and norms, level of development, elected municipal manager, appointed municipal manager; and (iii) internal capacity factors – technical capacity, administrative professionalism, wealth of public organizations, and years of experience (Ingrams et al., 2020). We also refer to the stages of e-government development, mostly in line with Layne and Lee (2001). This is also because the degree of differentiation is rather poor, subject to availability of information in the single-sign-on platform.

The research examines the development of e-government services in the field of social protection, which is directly related to developing electronic procedures for social services and benefits for vulnerable groups. Therefore, it is related not only to the topic of e-government at large, digitalization of social services in particular, but also to the topic of social inclusion. It also touches upon the issue of digital exclusion in examining discrepancies across territories, levels of public administration or different categories of social services and benefits.

In regard to the stages of e-government development, the key reference used rests with the four stages of e-government development, as identified by Layne and Lee (2001). We also refer to the UN stages of e-government development. In the first stage, cataloguing, there is an online presence, a presentation of services alongside downloadable forms, or, to put it shortly, in UN terms, there is an online presence established. The second stage (“transaction”) comes with developing interaction between public administration and citizen/business, and supplementary information is available online – services and forms are online, and there is a working database backing online transactions. Within the UN model, the second and third phases correspond partially to this description, as they consider an increase in dynamically provided information (second level) and the availability of downloadable forms, e-mail officials and interaction through the web (third level). The next phases under the Layne and Lee model consider vertical and horizontal integration, with the ultimate phase functioning as a one stop shop for citizens or, in the UN model, a seamless level where there is a full integration of e-services across administrative levels. Extension of Layne and Lee’s model has been proposed by Andersen, Henriksen (2006), together with revisiting the model with Lee, 2010, Heeks, 2015. Key added insights/critics refer to dependency on context and time, focus on higher levels of achievement than most governments actually succeeded in doing, no differentiation between the “front-office” nature of the interface/interaction, and the “back-office” nature, a focus on a single dimension (Heeks et al., 2015), or not imagining extensions beyond the one-stop shop (Linders et al. apud Scholta et al., 2019), which further means a rather reactive form of providing services. However, meta-synthesis approaches on various developed e-government maturity models conclude upon some common characteristics, at least in regard to the first phases of development – they all start with an online presence (creating websites for the government and/or agencies), corresponding to information dissemination – with one or two stages. The next phase includes an interaction (two-way communication between government and citizens). The third phase is represented by being able to perform online transactions with the government (similar to e-commerce) and the fourth stage is represented by a full integration of backend systems and information (called e-Participation, e-Democracy, or e-Governance) (Chaushi et al., 2015). With the aim of filling the gap in terms of offering proactive services and extending the stage model of e-government development, another study suggests the view of no-stop-shop, as a service that requires no forms, has an integrated back end and is proactive (a future can be predicted, but not its exact timing) or predictive (for instance for age-related services) (Scholta et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the current theoretical and practical buildup based on e-government stage models has been extensively used by both governments to establish strategic vision and necessary steps to be undertaken in implementation as well as by researchers (ibid.).

The EU model for benchmarking e-government development uses a tool with phases similar to those outlined above. They are applied taking into consideration specific life events, operationalized by specific services, with a distinction made between (i) informational services – differentiated between (ia) checking (information on service criteria, steps and/or requirements, checking eligibility); (ib) calculate (compute eligible financial benefits); (ic) get guidance (information to help users to carry out activity – tips, templates); (id) monitor (stay informed based on a registry); (ii) transactional services – online interaction, again separated between (iia) register; (iib) apply; (iic) obtain; (iid) submit; (iie) declare; (iif) appeal and (iii) portal websites – (eGovernment website that gathers and provides information and services from multiple public administrations) (European Commission, 2021b, pp. 14–15).

Factors affecting adoption of different stages of e-government development at local institutions level have been related to organizational factors, among others (Nam et al., 2016; Nasi et al., 2011; Müller & Skau, 2015; Ziemba et al., 2013). Other factors are related to economic (financial capacity, competition on ICT market, ICT education, economic risks, etc.), socio-cultural (for instance, ICTs awareness of managerial workers, ICT consultancy provided by external experts, social exclusion of workers, citizens, entrepreneurs) and technological (innovative hardware and networks, open source software licenses, ICT leaderships and competences, etc.) (Ziemba et al., 2013). Organizational factors include coordination of public ICT investments, approved e-government strategy, top management support, adaptation of new management models (ibid.). A longitudinal study of global cities highlighted differences in population size, GDP, and regional competition with a positive association, while democracy level rendered a rather vague influence, as determinants of e-government development (Ingrams et al., 2020).

This article considers procedures on social services available on a single e-government portal, but within it, distinguishes between informational and transactional services (namely, registering). Among the analysed life events there are only some that relate to the social field in general – part included under the larger category of family (including part of the benefits, requirements necessary for a funeral) or career (unemployment benefits and allowances, job search and participation in training programs, supporting people to find a job).

2.2Forms of digital divide/exclusion

In the increasing demand and development of e-government services, some groups/individuals can be placed at a disadvantage. The term digital divide has been used to encompass digital inequalities related mainly to access (firstorder divide), usage (secondorder divide) and use efficacy of digital resources (Vassilakopoulou et al., 2021). For the purpose of this study, availability of electronic procedures is therefore related to access, type of electronic procedures (informative versus operational) is linked to usage and the whole theme of the analysis – concentrated on vulnerable groups receiving social benefits and services – reflects on whether social vulnerability is also linked with forms of digital divide, as outlined by prior studies.

The study of the digital divide is closely linked to patterns of social inequality in the information society (Vartanova et al., 2019). A systematic literature review on this concept identifies different types of inequalities, as well as factors contributing to the digital divide, with a clear demarcation of several marginalized groups. In addition to access, factors comprise digital skills, autonomy, social support, motivation, personality traits, etc. A conceptual taxonomy of factors influencing e-inclusion distinguishes between (i) demographical dimension – age, gender, family structure, ethnicity and race; (ii) economic dimension – employment, income, cost; (iii) social dimension – education, health, lifestyle, motivation; (iv) cultural – language, knowledge, traditions, skills, IT literacy; (v) political – legislation and regulation, accessible information; (vi) infrastructural dimension – resources, access, urbanization (Weerakkody et al., 2012, pp. 309–310). Marginalized groups include older people (yet considered in several studies as a heterogeneous group), refugees and immigrants or several groups/individuals in the general population – in relation to income, education level, occupational status, digital skills, or living in specific territories, such as rural areas (Vassilakopoulou et al., 2021). The same study links the digital divide as a part of the larger topic of social inclusion – e-inclusion, the problems that arise from being left without offline choices, or the need to support sustainability in rural areas (ibid.). Consequently, several lines of relationship have been previously identified in the relationship between social exclusion and digital divide/exclusion. In this respect, the latest EU policy document, namely the Digital Compass for the EU’s digital decade includes a vision stating, for the year 2030, that basic digital skills will be available at a minimum of 80 percent of the population In terms of connectivity (gigabit for everyone, 5G everywhere), all key public services will be available one hundred percent online and all citizens will have access to their e-medical records (e-health). This strategic objective refers to reducing first-order divide, that of access. The digital principles that underpin this vision include universal digital education and skills and accessible and human-centred digital public services and administration (European Commission, 2021c). They will therefore address usage (secondorder divide) and use efficacy of digital resources.

Further studies identified other vulnerable groups like older people or persons with a low level of education. Information and communication poverty and service poverty have been brought up in a study on old-age digital exclusion (Cahill in Leppiman et al., 2021), with an increasing concern that the faster phase of digitalization in certain countries might ignore the needs of older users. Key elements in the design of digital solutions for older people, or the general population at large, are proposed: (i) starting points on everyday practicalities, human as a social factor; (ii) knowledge, cocreation – human centred, research knowledge and (iii) values and ethics – value oriented, ethical and moral principles. (ibid.).

The Matthew effect has also been brought out to light in relation to the first and second levels of the digital divide and/or inequalities. An analysis conducted in the Italian context shows that the gaps between the poorer categories (persons with a low level of education and those over the age of 64) and the richer categories (students, young people aged between 14 and 19) increased from 2001 to 2013. Therefore, the authors conclude that the Internet is an active reproducer of social inequality and a potential accelerator and that there is a close interrelation between digital and social exclusion, as well as between online and offline exclusion (Mingo et al., 2018).

The increased development of e-government services does not necessarily include an increase in the electronic services available for vulnerable groups. The pandemic context has substantially accelerated the increased usage of ICT, including the development of digital government. At the global level, there was also a positive trend in enhancing the provision of online services designed for vulnerable populations. The latest UN E-government survey registers, for 2020, compared to 2018, an increase in the number of countries offering online information and services for vulnerable groups by 11 percent. The same report highlights that services for people living in poverty and persons with disabilities are offered by fewer countries, which can be an indication that the needs of these groups are overlooked (UN, 2020, p. 26).

Persons with disabilities, one of the groups for which developed electronic procedures are examined by this article, have been identified among digitally disadvantaged people. Further on practices and policy recommendations for digitally disadvantaged groups of people, research has been conducted on specialized information systems for digitally disadvantaged (SISD) individuals. Drawing on technology perceptions and marked status awareness, empirical testing of SSID adoption on individuals with physical and/or sensory disabilities shows signs of a double disadvantage at least for the group with profound functional limitations (conducted in Germany). Members of this subgroup experienced disadvantages not only for technical reasons, but are also more sensitive to the fear of being considered vulnerable. Subsequently, this might have an impact on the likelihood of technology adoption – in reference precisely to a web portal especially designed for enabling communication for accessing a disability card, which can provide further access to services and benefits (Pethig et al., 2019, p. 1431).

Digitalised welfare agencies, such as the ones examined by this paper, can potentially act as agents of increased digital exclusion. Another conceptual research model used for studying the factors of e-inclusion in the UK covers normative beliefs (interpersonal, external), control beliefs (availability, accessibility, capacity), gratifications (content, process, social), attitudinal beliefs (perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, trust in e-government, trust in internet, perceived risk), with various intercorrelations between them. The use of e-government has been identified as the deepest gap that exists among individuals using the Internet (Al-Muwil et al., 2019). Additionally, in the UK context, another study identifies several factors associated with the underutilization of e-government services, such as poor design, effective access and level of digital literacy (Harvey et al., 2021). The article argues that digitalised welfare agencies simultaneously sustain existing lines of social stratification and enhance these by producing new forms of digital exclusion. This is in line with a similar conclusion stating that “given the huge variety of application-based services to master the challenges of daily life, those who are not well connected are likely to be distanced and excluded” (Trappel, 2019, p. 22). A similar line of argument, highlighting a usage preference of prepaid postcard and postcard requiring postage over using a hotline or email to seek information is highlighted in a study on usage of communication technologies in disadvantaged groups (Linos et al., 2021). Same study mentions welfare stigma among psychological costs of directly interacting with bureaucrats (ibid). Usage of email or direct communication through an online platform could provide a low cost on this respect.

3.Research context

3.1E-government development in Romania

In the EU larger context, Romania does not display a picture conducive to the development of e-government. Romania ranks 26th out of 28 EU Member States in the 2020 Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) (European Commission, 2020). Its particular positive dimension pertains to a higher performance regarding connectivity. The picture turns grey concerning performance on digital public services. On this topic, Romania ranks last among EU Member States during the last 3 years. Although one of the components of the index is far better (e-government users, meaning share of internet users needing to submit forms), Romania has the lowest scores in the EU concerning prefilled forms and online service completion. The quality and usability of the services offered are used to explain low scores for prefilled forms and online service completion (European Commission, 2020). Additionally, the latest e-government benchmarking places Romania among the EU lowest scores concerning Penetration (16%) level, with 51 percentage points below the EU average, and, again, the lowest Digitalisation level (40%), which is 31 percentage points below EU average. Consequently, Romania is considered part of the nonconsolidated eGov scenario, meaning it is not able to fully exploit ICT opportunities (European Commission, 2021a, p. 87).

At the global level, Romania stands slightly better. The latest UN report on e-government development places Romania among the group of 18 countries ranked in the very high E-Government Development Index group for the first time, alongside six other countries from Europe – Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Latvia, Croatia and Hungary. At the same time, progress is indicated to be needed for improving OSI – Online Service Index values. Romania is in the group of thirteen countries with very high levels of human capital development and well-developed infrastructure, yet low OSI values (UN, 2020, p. 21). The Online Service Index (OSI) is based on several indicators assessing each country’s national website in the native language, including the national portal, e-services and e-participation portal, as well as the websites of the related ministries of education, labour, social services, health, finance and environment as applicable (UN, 2016, p. 138). However, it is important to contextualize scores obtained from benchmarking e-government development based on the general background and advancements in public administration (Skargren, 2020) or a better understanding of the factors influencing the use of e-government in Europe and the different adoption levels (Yera et al., 2020).

The latest information at the national level outlines that 16 percent of individuals using the internet in the past twelve months have interacted with public authorities or services (data for 2021). Those who declared to use this type of interaction with public authorities were individuals aged 35–54 years (20 percent) and 16–34 years (17 percent), with a high level of education and employment (from the point of view of occupational status). Reasons for not interacting with public authorities outline that women are less worried than men about the protection or security of personal data, and the same holds true for residents from urban areas. The share of persons who identified a lack of digital skills or knowledge decreased significantly in 2021 compared to 2020 among the group of reasons for not sending forms to public authorities. Another reason showing a decrease is registered for the reason stating “there is no such electronic service on the website or online application available at the public authority” – a decrease from 16.4 percent in 2020 to approximately 8 percent in 2021 (National Institute of Statistics, 2021). This result could indicate a better online presence of public authorities and/or improved digital skills of the user in identifying the necessary relevant information on the corresponding websites.

3.2Public administration structure in Romania

This section presents the main public institutions in the field of social services and benefits in Romania. The key divisions are as follows: local level – municipalities with a high differentiation between urban and rural municipalities, county level – county councils and their subordinated relevant institutions – General Directorates of Social Work and Child Protection (DGASPC) and national level – ministries and national authorities and agencies. Furthermore, particularly important for the current analyses are the deconcentrated institutions that are located at the county level. The deconcentrated institutions are actually county units subordinated to a particular national-level authority – ministry or national agency/authority.

Table 1

Institutions in the field of social work at the central, county and local levels in Romania

| Institution | Coordinating role | Regulator role | Implementation role | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central level | Ministry of Labour and Social Protection | |||

| National Authority for the Rights of People with Disabilities, Children and Adoption | ||||

| Labour Inspection | ||||

| National Authority of Payments and Social Inspection | ||||

| National Agency of Equality of Chances | ||||

| County level | County Council (CJ)/President of CJ | |||

| General Directorates of Social Work and Child Protection (DGASPC) | ||||

| Prefecture | ||||

| County Agencies for Payments and Social Inspection | ||||

| County Offices of Labour Inspection (deconcentration) | ||||

| Local level | Local Council (CL)/Mayor | |||

| Local Public Services of Social Work |

Adapted by the author from Magheru (2010: 7). Note: The author has adapted the names of the institutions according to the current status (July August 2021); therefore, they appear different from the cited source.

In addition to the institutions outlined in Table 1, there are two other institutions that are relevant for the aim of the current study. They are under the authority of the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection and provide relevant social services – National Public Employment Service (ANOFM) and National House of Public Pensions (CNPP). Both of them have county deconcentrated institutions, on a similar model with other national authorities included in Table 1 – National Authority of Payments and Social Inspection.

The conclusions of previous studies on the structure of the social assistance system in Romania are still valid: there is an imbalance between the national, county, and local levels regarding the number of institutions and the roles given by the legislative framework, as seen in Table 1, as a synthetic picture of the social assistance institutions for all levels of public administration in Romania. “The local level should, in accordance with the legal provisions, ensure in a uniform manner, what all actors at the county and central level ensure in a segregated manner, while maintaining the quality of services, but having a limited number of resources, human, material or financial” (Magheru, 2010, p. 8). Therefore, the social welfare system in Romania is well developed at the central and county levels, nonetheless with a fragile and poorly developed foundation at the community level, especially in rural areas. Put it in other words, the structure of the social assistance system in Romania looks like, even today, a pyramid with a downwards tip, with many institutions at the central and county level and very few at the local level (Lazăr, 2015, pp. 7–8).

Nonetheless, previous reports state that there has been a development of e-government social services (Romanian Court of Accounts, 2020; Stănculescu & Morrica, 2020). The report conducted by the Romanian Court of Accounts cites in particular the case of deconcentrated institutions, which are also under scrutiny in the present report. In particular, during the state of emergency (but also during the period of alert for certain benefits) the National Agency for Payments and Social Inspection (ANPIS) had to ensure the continuity of the granting social assistance benefits, as well as the payment of new types of social benefits, such as the payment of a monthly allowance for certain categories of taxpayers, as well as subsidies for social assistance centers that have closed their work. To this end, e-mail services have been developed, and ANPIS has introduced thirteen procedures for the electronic transmission of documents to facilitate applying for social work benefits.

4.Methods

The key source of information for conducting this research is the database of the single-sign-on platform created for electronic procedures for both citizens and businesses. Research questions address whether there is a difference in the availability of electronic delivery of social services and benefits during the pandemic period and examine potential differences between types of services and benefits, counties/regions and types of institutions (central, regional/county, local – mayoralties/urban and rural municipalities).

Each database of the available electronic procedures from the unique electronic point (PCUe) in Romania was accessed on January 7, 2020, and January 19, 2021. Therefore, the analyzed procedures from 2021 database mostly reflect the development during the pandemic period from 2020. The accessed data source is represented by the catalogue of all procedures available for citizens and business. The unique electronic contact point in Romania has been developed to avoid going to the front office, reduce the length of getting certificates/authorizations and ensure transparency in ensuring each claim/file.

The databases from 2020 and 2021 analysed from a comparative perspective contain only operational procedures, meaning that the files can be submitted electronically via the single-sign-on platform. From a total of 2,096 procedures available in 2020, only 134 procedures have been identified as relevant for the social field. In 2021, from a total of 3,169 procedures, a set of 876 operational procedures from the social benefits and services theme are included in the analysis. Services related to education and health, although included in the larger field of social services, are not part of this scrutiny. Therefore, the focus of the study is on the social protection field.

In addition, in July 2021, a separate search was conducted to identify the procedures from the social fields that were only informative, meaning that only the necessary information was posted about them. In case of these procedures, the single-sign-on platform states that the file can only be physically submitted at the institution’s headquarters. From a total of 1,584 informative procedures available on July 22, 2021, the analysis identified a set of 95 procedures relevant for the social field. A similar database is not available for 2020. The categorization of informative or operational procedures was performed according to the information provided on the website. The exact URL used is edirect.e-guvernare.ro/Admin/Catalog/CatalogServiciiComplete.aspx.

All collected procedures were exported into SPSS databases and analysed using a similar set of codes regarding the type of institution, procedure and level of authority. Detailed results are presented in the section below. The analysis does not include the municipality of Bucharest and its six districts, as they represent a “special case” in terms of local public administration structures. According to the current legal framework of public administration, the mayoralty of Bucharest (capital city) has a split of responsibilities shared with the six districts of Bucharest regarding administering social services and benefits, and therefore the range of institutional responsibilities is not directly comparable to the set of institutions examined in this paper. The institutions at district level in Bucharest, although municipalities, function in an institutional structure similar to the county level (DGASPC), and not to the municipality level. However, as noted earlier, some services and benefits are administered by the municipality of Bucharest, and not by them. Consequently, their range of responsibilities also differs from the rest of administrative units (county/ urban or rural municipalities).

5.Results

This section presents the results of the analysis grouped around two subsections: (i) operational procedures in the field of social benefits and services (ii) informative procedures in the field of social benefits and services available in 2021. They differentiate between stages of e-government development in Romania. Operational procedures allow registering an application and sending all the necessary documentation through the single-sign-on platform. Informative procedures only offer information about the related services and benefits, without the option of directly sending the necessary documentation. Within each of them, several factors are examined – such as type of institution, territory (county/ mayoralty), residence area (urban/rural municipalities) and type of social benefit/service.

5.1Operational procedures in the field of social benefits and services

Type of institution and territory differentiate against availability of operational procedures. The analysis shows an overall general increase of the electronic procedures available from the County Agencies for Payments and Social Inspection (AJPIS), deconcentrated institutions, and mayoralties (social assistance compartments or departments within the organizational structure of the municipalities). On the contrary, there have been no new electronic procedures available for General Directorates for Social Work and Child Protection (DGASPC). However, representatives of these institutions actually increased acceptance of the electronic format of required documents or certificates in 2021 compared to 2020 (Stănculescu & Morrica, 2020). Hence, it is possible that there has also been an increase in the development of services conducted using electronic means for the case of the DGASPC, which is not captured by this study, as they have not been registered as electronic procedures in the corresponding single-sign-on platform.

There are significant disparities between counties or types of electronic procedures from the same type of institution. If taking a closer look at only the procedures available from the institution with the largest increase in the examined electronic procedures, namely, AJPIS, there are several discrepancies/types of divides in the electronic procedures available from this institution.

Across territories and benefits processed by the same institution (AJPIS), there is only one procedure that is available in each county. This is the procedure related to the social benefits left uncollected by deceased people with disabilities. Notably, from the whole spectrum of procedures available at the AJPIS level, county deconcentrated institutions subordinated to the Ministry of Labor, the only procedure available at the national level, is from the field of protection of people with disabilities. However, it refers to the moment when direct beneficiaries are deceased. In addition, there are two counties (Alba and Botoşani), where this is the only available procedure, although the range of responsibilities between AJPIS from different counties is similar. Another county – Bistriţa-Năsăud – has only three available electronic procedures, while most of the other AJPIS from different counties range from 13–14 procedures to maximum levels of 22–25 procedures (Brăila, Dolj, Covasna and Harghita). Therefore, although county AJPIS are all subordinated to the same central level institution, each one has its own different number of available procedures.

By number and type of registered procedures, the largest size of electronic procedures available from AJPIS is registered for the heating subsidies. Yet, this type of procedure (as well as the rest of the procedures) is not available in each county, as mentioned above. Moreover, while the rest of the counties have four or five different procedures for heating subsidies, two other counties (Bistriţa Năsăud and Buzău) have only one procedure corresponding to this social benefit. These counties merged in only one procedure the benefits related to social aid (minimum income guarantee), family state allowance and heating subsidies. The rest of the counties with four or five procedures have differentiated them by means of heating (natural gas, electricity, heat, solid or oil fuel). Therefore, each county AJPIS has its own way of merging or differentiating a set of similar procedures under their responsibility. This means that one user applying for the same social benefit in different counties needs to interact with public institutions in a different way.

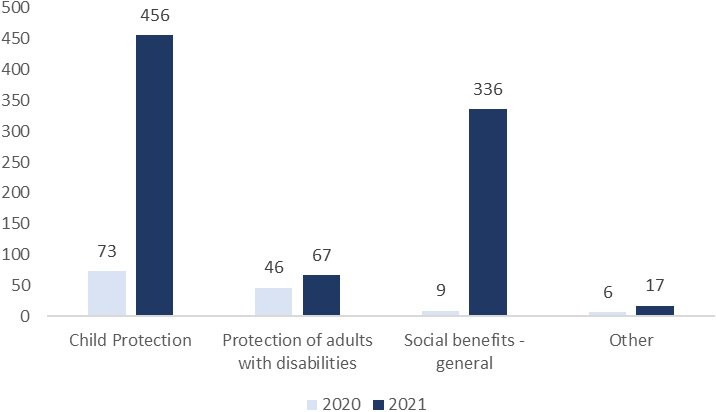

Further on by types of institution and procedure, most of the available procedures at the municipality level are represented by the state child allowance, minimum income guarantee, heating subsidy and child rearing benefit. Few procedures refer to the vulnerable group represented by persons with disabilities. Their distribution is somewhat similar to that registered at the national level. As the figure below illustrates, the largest increases registered in 2021 compared to 2020 refer to various benefits and services related to child protection or to general social benefits (Fig. 1). Grouping of procedures into these broader categories is presented in the Annex.

Figure 1.

Electronic procedures from the field of social services available in the single-sign-on platform by type of broad category, 2021 vs. 2020. Source: Author’s calculations based on the databases of procedures available in the unique electronic point, 2021 and 2020.

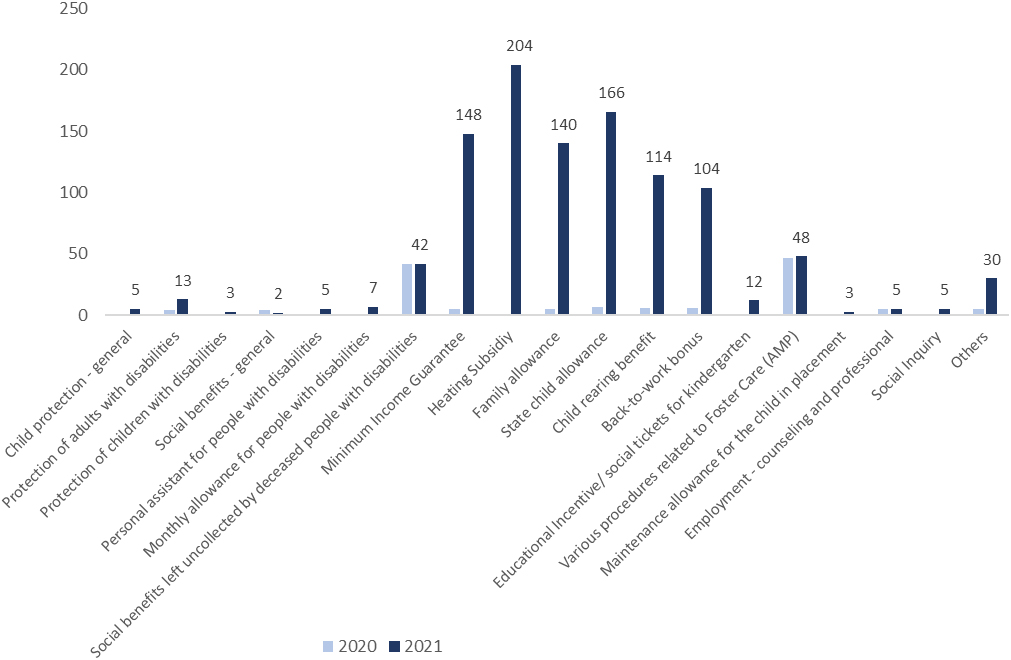

Figure 2.

Electronic procedures from the field of social services available in the single-sign-on platform by type of social benefits and services, 2021 vs. 2020. Source: Author’s calculations based on the databases of procedures available in the unique electronic point, 2021 and 2020. Multiple responses.

Moreover on types of electronic procedures, if we consider a more disaggregated analysis level, there are specific types of social benefits that increased from almost zero available procedures in 2020 to more than one hundred available procedures in 2021 (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, this does not mean that there are more than one hundred different procedures available at the national level. The unique identification pair is formed by the county/locality and type of registered procedure. As there is no standardization between them, it is difficult to measure an accurate increase in uniquely identified electronic procedures of the single-sign-on platform from Romania. To add even more complexity, one registered procedure can merge in the same entry three or more procedures related to different social benefits. However, this limitation is valid not only for the field of social services and benefits but also for all the other fields of responsibilities of the institutions registered on the platform.

At the local level,44 there are only 48 municipalities (out of 3180) that registered electronic procedures in the field of social services in January 2021. Again, as in the case of the DGASPC, most likely more of them have made more intensive use of electronic means of communication either with citizens or with other public institutions (such as AJPIS – for the case of submitted files for various social benefits). Out of these 48 municipalities, only 19 are from urban areas. Moreover, not all of the urban municipalities are county seat residences. The latter presumably have at least some of the highest financial and administrative capacities within their corresponding counties. These municipalities come from 25 counties (out of a total of 40). The highest number of municipalities is four, and it corresponds to the counties of Caraş-Severin, Ialomiţa and Tulcea. Notably, there are nine rural municipalities and one urban municipality that have only one electronic procedure available in the single-sign-on platform, and this procedure refers to social services. As another maximum value, there is only one county seat residence (Ploieşti, Prahova) where all twenty-two registered procedures refer to social services and benefits.

At the county level, the County Social Assistance and Child Protection Directorates (DGASPC) have mostly available only one type of procedure related to child protection – foster care, most likely as a result of implementation of a European project, with the main implementing agency placed at the central level.

5.2Informative procedures in the field of social benefits and services in 2021

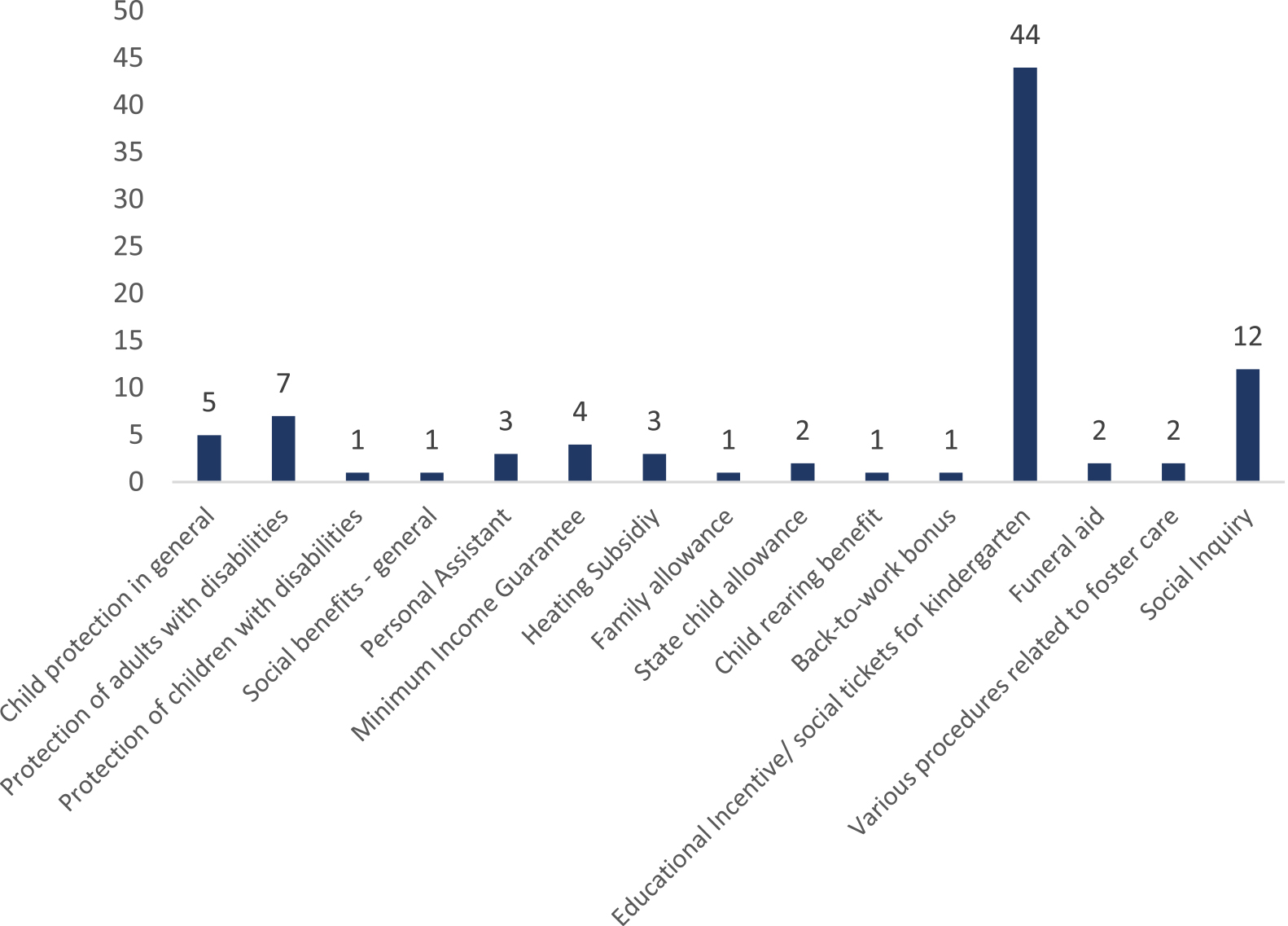

The analysis from this section corresponds to the early stages of e-government development, as it deals with procedures that only provide citizens with access to online information. For the procedures presented in this section, the file can only be physically submitted at the institution’s headquarters. Factors related to types of institution and procedure are analysed. Figure 3 presents their distribution by type of procedure.

Figure 3.

Distribution by type of informative procedure in 2021. Source: Author’s calculations based on the databases of informative procedures available at the unique electronic point, 2021. Multiple responses.

Distribution by type of informative procedures shows a similar picture as in the case of operational procedures for the group of deconcentrated institutions. In other words, the County School Inspectorates, deconcentrated institutions subordinated to the Ministry of Education, act in the same way as do deconcentrated institutions mentioned above, subordinated to the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection. These represent the largest group of informative procedures. For this type of institution, in our analysis, we selected only a type of procedure connected to the social field – social tickets for attending kindergarten. Nonetheless, each County School Inspectorate multiplies each procedure in every county. This means that there are 41 informative procedures for each educational topic – enrollment in primary education, second chance programmes, various national programmes, certifying the training of high school graduates, etc. However, this finding holds true for various deconcentrated institutions – such as the Border Police Offices or Public Health Directorates.

Following the procedures from these deconcentrated institutions, the second type of institution represented in the group of informative procedures is the one of mayoralties. Nonetheless, contrary to expectations, these informative procedures are not submitted by rural mayoralties, which have low financial and administrative capacity. In the total number of 34 informative procedures submitted by municipalities, only two are from one rural municipality. The rest of them have all been submitted by urban municipalities. In contrast, in the group of 48 municipalities with operational procedures, most of them (namely, 29) are rural municipalities.

In total, informative procedures were submitted by a total of 15 municipalities, four of which also have operational procedures. Consequently, a total of 59 municipalities (from a total of 3,180) have either informative or operational procedures in the single-sign-on platform in 2021.

Even if they are registered as informative procedures, a content analysis reveals that some public institutions do not even mention the necessary documents. For instance, one urban mayoralty (Siret, Suceava) mentions only the name of the procedure, without stating which, if any, are the requested documents. In addition, another mayoralty of a large urban municipality introducing various informative procedures requires the central element of the traditional face-to-face interaction with the Romanian public institutions: a file with rail (dosar cu sina). This type of paper-based file is still key to various submissions required by public institutions even today. It already represents a hallmark for the nondevelopment of e-government services.

6.Discussion

This study reconfirms the finding according to which “e-government development is certainly neither inevitable nor unilinear” (Ingrams et al., 2020). The conducted analysis shows that, for the same operational procedure, there are several public authorities with different procedures present in the same electronic platform. This analysis indicates a low level of vertical and horizontal integration. The procedures seem to be county- and institution-focused rather than citizen-focused. Additionally, better integration would require improved collaboration between different government levels.

Another point of improvement is that the procedures that have been introduced as informative have actually been included by public authorities from large urban areas with high financial capacity. At the same time, rural areas from Romania, with a significantly lower administrative and financial capacity, succeeded in introducing electronic procedures that are operational in the single sign-on-platform in 2021. This finding is in line with the observed regional inequalities that transform specific territories into “administratively disadvantaged” territories (Budai & Tozsa, 2020), but in contrast with the assumption that territorial administrative units with higher financial capacity are more likely to submit operational electronic procedures.

Concerning the potential factors of e-government development, the analysis takes into consideration the type of institution – with a differentiation between deconcentration and decentralization. The deconcentrated institutions have higher chances of developing e-government services, as they are all subordinated to one central authority. Furthermore, on the factors influencing e-inclusion, territory – here represented by county – distinguishes between the offer of electronic procedures on social services.

Limitations of the study are inherent to the limitations of the data source used. The analysis takes into account only the electronic procedures registered in this platform. As previously stated, as there is no standardization between them, it is difficult to measure an accurate increase in uniquely identified electronic procedures of the single-sign-on platform from Romania. Nonetheless, the impetus for the development of e-government social services in Romania could have been reflected in the direct communication of the responsible institutions, as posted on their websites. To address this limitation, future studies should focus on a key institution at the county level, namely County Directorates for Social Assistance and Child Protection. Additionally, the diversity and variety of over three hundred thousand websites of the mayoralties requires a dedicated and strong effort.

7.Conclusions

The comparative analysis conducted in this study reveals a development of e-government in the field of social services and benefits in Romania, during the pandemic background of 2020. The compared databases include electronic procedures in early 2021, respectively early 2020, available on the single-sign-on platform. The study also points out factors influence the development of e-government services in social protection area in Romania during the pandemic crisis. These pertain to the type of institution (including subordination), type of procedure or territory (county and residence area).

Significant improvements are needed to standardize the same procedures from different institutions, irrespective of their type of affiliated territory. Even among similar institutions, like deconcentrated institutions subordinated to the Ministry of Labor, there is no standardized set of available electronic procedures. The most eloquent case highlighted by the study is that of the key institution administering social benefits in Romania – County Agencies for Payments and Social Inspection, which are all subordinated to the same central level institution – Ministry of Labor. There is only one procedure that is available in each county, across these county institutions. The procedure relates to the moment when direct beneficiaries are deceased - social benefits left uncollected by deceased people with disabilities.

The examined electronic procedures are county- and institution-focused rather than citizen-focused. Still, on the positive side, rural areas from Romania, with a significantly lower administrative and financial capacity than the urban ones, succeeded in introducing electronic procedures that are operational in the single sign-on-platform in 2021. Consequently, more efforts are required in particular from large urban municipalities.

There is a low level of coordination among responsible centrallevel agencies, especially at the level of deconcentrated units. Analysing the development of e-government data in the field of social services and general benefits should be of interest to policy makers in particular as the global context of the COVID-19 pandemic has brought both new challenges alongside opportunities for developing this policy sector. Governmental officials should be interested in looking at these data and encourage enabling a functional centrallevel platform where citizens can follow all the stages of an interactive procedure, with information about the decision on their application. Insights provided by the paper are useful for decision makers to better design online social services in a standardized format across the territory.

Although applied to the Romanian case, the methodological approach proposed by this paper can be reiterated in other settings, especially in countries where there is a single-sign-on platform collecting electronic procedures available in the field of social services and benefits. Thus, it is possible to monitor developments in the field of e-government services over time in a similar way and carry out comparative analyses, analogous to this work.

Notes

1 Universal child allowance covers all children.

2 One of the social services is applying for issuing a disability certificate, certifying the type and degree of disabilities.

3 A complete list of items and their grouping under broader categories of child protection, protection of adults with disabilities and social benefits is presented in Table 2.

4 The analysis at municipality level did not take into account the municipality of Bucharest and its six districts.

Funding

The work conducted for this study is part of the annual research plan, funded by the Romanian Academy of Sciences, Research Institute for Quality of Life.

References

[1] | Al-Muwil, A., Weerakkody, V., El-haddadeh, R., & Dwivedi, Y. ((2019) ). Balancing digital-by-default with inclusion: A study of the factors influencing e-inclusion in the UK. Information Systems Frontiers, 21: (3), 635-659. doi: 10.1007/s10796-019-09914-0. |

[2] | Andersen, K.V., & Henriksen, H.K. ((2006) ). E-government maturity models: Extension of the Layne and Lee model. Government Information Quarterly, 23: (2), 236-248, doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2005.11.008. |

[3] | Braun, M. ((2021) ). Impulses of a preventive work design in the digitalization of public administration. Zentralblatt Fur Arbeitsmedizin, Arbeitsschutz Und Ergonomie. Springer Medizin. doi: 10.1007/s40664-020-00408-4. |

[4] | Budai, B., & Tózsa, I. ((2020) ). Regional inequalities in front-office services. Focus shift in e-government front offices and their regional projections in Hungary, Regional Statistics, 10: (2), 206-227. doi: 10.15196/RS100212. |

[5] | Chaushi, A., Chaushi, B.A., & Ismaili, F. ((2015) ). Measuring e-government maturity: A meta-synthesis approach. SEEU Review, 11: (2). https://sciendo.com/pdf/10.1515/seeur-2015-0028. |

[6] | Chirara, S. ((2018) ). Social inclusion: An e-government approach to access social welfare benefits. Thesis. Nottingham Trent University. http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/35355/1/Simbarashe%20Chirara%202018.pdf. |

[7] | European Commission ((2020) ). Digital Economy and Society Index 2020 Romania. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi-romania. |

[8] | European Commission, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology ((2021) a). eGovernment benchmark 2021: entering a new digital government era: country factsheets. Publications Office, doi: 10.2759/485079. |

[9] | European Commission, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology ((2021) b). eGovernment benchmark: method paper 2020–2023. Publications Office, doi: 10.2759/640293. |

[10] | European Commission ((2021) c). Europe’s Digital Decade: digital targets for 2030. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/europes-digital-decade-digital-targets-2030_en. |

[11] | Fahmi, F.Z., & Sari, I.D. ((2020) ). Rural transformation, digitalisation, and subjective wellbeing: A case study from Indonesia. Habitat International, 98: , 102150. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102150. |

[12] | Gambino, O., Pirrone, R., & Di Giorgio, F. ((2016) ). Accessibility of the Italian institutional web pages: A survey on the compliance of the Italian public administration web pages to the Stanca Act and its 22 technical requirements for web accessibility. Universal Access in the Information Society, 15: , 305-312. doi: 10.1007/s10209-014-0381-0. |

[13] | Harvey, M., Hastings, D.P., & Chowdhury, G. ((2021) ). Understanding the costs and challenges of the digital divide through UK council services. Journal of Information Science, 016555152110406. doi: 10.1177/01655515211040664. |

[14] | Heeks, R. ((2015) ). A Better e-Government Maturity Model. iGovernment Briefing No. 9. Centre for Development Informatics: University of Manchester. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/gdi/publications/workingpapers/igov/short_papers/igov_sp09.pdf. |

[15] | Ingrams, A., Manoharan, A., Schmidthuber, L., & Holzer, M. ((2020) ). Stages and determinants of e-government development: A twelve-year longitudinal study of global cities. International Public Management Journal, 23: (6), 731-769. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2018.1467987. |

[16] | Layne, K., & Lee, J. ((2001) ). Developing fully functional e-government: A four stage model. Government Information Quarterly, 18: (2), 122-136. |

[17] | Lazăr, F. ((2015) ). Asistenţă socială fără asistenţi sociali? (Social assistance without social workers?). Bucureşti: Editura Tritonic. http://api.components.ro/uploads/12c6a09675620f589055800ba6ceceee/2016/07/Studiu_Asistenta_sociala_fara_asistenti_sociali.pdf. |

[18] | Lee, H., Irani, Z., Osman, I.H., Balci, A., Ozkan, S., & Medeni, T.D. ((2008) ). Research note: Toward a reference process model for citizen-oriented evaluation of e-Government services. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 2: (4), 297-310. doi: 10.1108/17506160810917972. |

[19] | Lee, J. ((2010) ). 10 year retrospect on stage models of e-government: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Government Information Quarterly, 27: (3), 220-230. |

[20] | Leppiman, A., Riivits-Arkonsuo, I., & Pohjola, A. ((2021) ). Old-Age Digital Exclusion as a Policy Challenge in Estonia and Finland. In: Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (eds). Social Exclusion in Later Life. International Perspectives on Aging, Vol 28. Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_32. |

[21] | Linos, K., Carlson, M., Jakli, L., Dalma, N., Cohen, I., Veloudaki, A., & Spyrellis, S.N. ((2021) ). How Do Disadvantaged Groups Seek Information About Public Services? A Randomized Controlled Trial of Communication Technologies. Public Administration Review, 1-13. doi: 10.1111/puar.13437. |

[22] | Magheru, M. ((2010) ). Descentralizarea sistemului de protecţie socială din România (Decentralization of social protection system in Romania). UNICEF. http://www.unicef.ro/wp-content/uploads/descentralizarea-protectiei-sociale-in-romania-ro-.pdf. |

[23] | Mingo, I., & Bracciale, R. ((2018) ). The matthew effect in the italian digital context: The progressive marginalisation of the “poor”. Social Indicators Research, 135: , 629-659. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1511-2. |

[24] | Müller, S.D., & Skau, S.A. ((2015) ). Success factors influencing implementation of e-government at different stages of maturity: A literature review. International Journal of Electronic Governance, 7: (2), 136. doi: 10.1504/IJEG.2015.069495. |

[25] | Nam, K., Oh, S.W., Kim, S.K., Goo, J., & Khan, M.S. ((2016) ). Dynamics of enterprise architecture in the korean public sector: Transformational change vs. transactional change. Sustainability, 8: , 1074. doi: 10.3390/su8111074. |

[26] | Nasi, G., Frosini, F., & Cristofoli, D. ((2011) ). Online service provision: Are municipalities really innovative? The case of larger municipalities in Italy. Public Administration, 89: (3), 821-839. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01865. |

[27] | National Institute of Statistics ((2021) ). Population Access to Information and Communication technology – Romania 2021 [Accesul Populaţiei la Tehnologia Informaţiilor şi Comunicaţiilor, în anul 2021] https://insse.ro/cms/en/content/population-access-information-and-communication-technology-%E2%80%94-romania-2021. |

[28] | Pethig, F., & Kroenung, J. ((2019) ). Specialized information systems for the digitally disadvantaged. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 20: (10), 1412-1446. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00573. |

[29] | Ranerup, A., & Henriksen, H.Z. ((2020) ). Digital Discretion: Unpacking Human and Technological Agency in Automated Decision Making in Sweden’s Social Services. Social Science Computer Review, 1-17. doi: 10.1177/0894439320980434. |

[30] | Romanian Court of Accounts ((2020) ). Gestionarea resurselor publice în perioada stării de urgenţă. Raport special realizat la solicitarea Parlamentului României (Management of public resources during emergency state. Special report conducted upon request of the Romanian Parliament). http://www.curteadeconturi.ro/Publicatii/Raport_stare_urgenta_11082020.pdf. |

[31] | Skargren, F. ((2020) ). What is the point of benchmarking e-government? An integrative and critical literature review on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government. Information Polity, 25: , 67-89. doi: 10.3233/IP-190131. |

[32] | Stănculescu, M.S., & Morrica, V. (eds.) ((2020) ). Romania: collecting just in time feedback on COVID-19 pandemic in vulnerable communities (four monitoring reports). World Bank. Unpublished research reports. |

[33] | Sirendi, R., & Taveter, K. ((2016) ). Bringing Service Design Thinking into the Public Sector to Create Proactive and User-Friendly Public Services. In Nah, F.H., Tan, C.H. (eds.). HCI in Business, Government, and Organizations: Information Systems. HCIBGO 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol 9752. Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39399-5. |

[34] | Scholta, H., Mertens, W., Kowalkiewicz, M., & Becker, J. ((2019) ). From one-stop shop to no-stop shop: An e-government stage model. Government Information Quarterly, 36: (1), 11-26. ISSN 0740-624X, doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.11.010. |

[35] | Trappel, J. ((2019) ). Inequality, (new) media and communications. In Josef Trappel (ed.) Digital Media Inequalities: Policies Against Divides, Distrust and Discrimination, pp. 9-30. Göteborg: Nordicom. |

[36] | Yera, A., Arbelaitz, O., Jauregui, O., & Muguerza, J. ((2020) ). Characterization of e-Government adoption in Europe. PLoS ONE, 15: (4), e0231585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231585. |

[37] | UN ((2020) ). United Nations E-Government Survey 2020. Digital Government in the Decade of Action for Sustainable Development. https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2020. |

[38] | UN ((2016) ). UN E-Government Survey methodology. Annexes. https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/Portals/egovkb/Documents/un/2016-Survey/Annexes.pdf. |

[39] | Vartanova, E., & Gladkova, A. ((2019) ). New forms of the digital divide in Josef Trappel (ed.) Digital Media Inequalities: Policies Against Divides, Distrust and Discrimination, pp. 193-213. Göteborg: Nordicom. |

[40] | Vassilakopoulou, P., & Hustad, E. ((2021) ). Bridging Digital Divides: a Literature Review and Research Agenda for Information Systems Research. Information Systems Frontiers. doi: 10.1007/s10796-020-10096-3. |

[41] | Scholta, H., Mertens, W., Kowalkiewicz, M., & Becker, J. ((2019) ). From one-stop shop to no-stop shop: An e-government stage model. Government Information Quarterly, 36: (1), 11-26. ISSN 0740-624X, doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.11.010. |

[42] | Weerakkody, V., Dwivedi, Y., El-Haddadeh, R., Almuwil, A., & Ghoneim, A. ((2012) ). Conceptualizing e-inclusion in europe: An explanatory study. Information Systems Management, 29: (4), 305-320. doi: 10.1080/10580530.2012.716992. |

[43] | Ziemba, E., Papaj, T., & Żelazny, R. ((2013) ). A model of success factors for e-government adoption – the case of poland. Issues in Information Systems, 14: (2), 87-100. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264707272_A_model_of_success_factors_for_e-government_adoption_-_the_case_of_Poland. |

Appendices

Annex

Table 2

List of items grouped into key categories of available electronic procedures

| Name of the category | Type of procedure |

|---|---|

| Child Protection | State child allowance |

| Back-to-work bonus | |

| Child rearing benefit | |

| Benefits for children with disabilities | |

| Educational incentive/social tickets for kindergarten | |

| Different procedures related to foster care | |

| Risk assessment for children | |

| Protection of adults with disabilities | Personal Assistant |

| Monthly allowance for people with disabilities | |

| Social benefits left uncollected by deceased people with disabilities | |

| Social inquiry conducted for disability assessment | |

| Social benefits – general | Heating subsidy |

| Minimum Income Guarantee | |

| Social tariff for electricity | |

| Social inquiry | |

| Other | Employment, counseling, training services |

| Various other procedures not included above |

Author biography

Anca Monica Marin is currently a Senior Researcher at the Research Institute for Quality of Life. She has been a doctor in sociology since 2015. She worked as a consultant in over 50 research projects on various topics and published over 50 papers (individual or collective articles, books, chapters in books, research reports). Her main research interests are public management, European funds, poverty and social inclusion, and local development. Monica’s PhD thesis was dedicated to the role of local administrative capacity in European absorption funds for Romanian communes and was published in 2015. Her most recent publication is a single author book published by Springer on the quest for state-budget funds in Romania.