What is the point of benchmarking e-government? An integrative and critical literature review on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government

Abstract

This literature review looks at research conducted on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government during the years 2003 to 2016 and entails 27 articles. The review shows how this field has changed over time, its main findings and what the potential benefits are for the public sector in using the results from benchmarks. The findings reveal how initial research created taxonomies of benchmarks and criticised them for being too focused on measuring online services. This research was followed by even more criticism on how benchmarks can have a negative impact on e-government policy and development. During the same time-period there is research giving methodological support on how to improve ways of benchmarking. Later research offer theoretically and conceptually informed critique of benchmark-studies. The review finds that there are mainly implicit assumptions about the potential benefits in using benchmarks for improving e-government. The article concludes by discussing the implications of the findings in terms of the lack of context and relevance in benchmarks for e-government in relationship to the nature of public administration and makes suggestions for ways forward.

1.Introduction

Since the end of the 1990s the business of e-government has been influenced by a relatively large number of international organizations and multinational companies that claim to be “benchmarking e-government”. As of 2003, researchers have begun studying this phenomenon by comparing the differences of various benchmarks for e-government, as well as scrutinizing the usefulness of assessing the progress of e-government in this way and looking at their effects on public administrations and government (see Bannister, 2007; Jansen, 2005; Janssen, 2003; Janssen et al., 2004; Kunstelj & Vintar, 2004; Snijkers et al., 2007). By means of a literature review, this article analyses how research on benchmarking e-government has evolved over time, with a particular focus on its main findings and the possible benefits these benchmarks have had for the public sector.

The field of e-government deals with descriptive, explanatory and normative questions around the use, implications and progress of information technology within the public sector and its relationship with citizens, businesses and other societal actors. A popular criticism in research on benchmarks is to lament how the concept of e-government has become synonymous with the interaction between citizens and governments via information and communication technology (ICT), and to instead argue for how benchmarks should focus on the use of information systems in internal, or back-office, processes. During the wide-spread introduction of the internet in the 1990s and the potential for new ways of interacting with citizens and businesses with the use of ICT, is also when the term e-government is coined (Bannister & Connolly, 2012; Grönlund & Horan, 2005). Before the 1990s e-government could be defined as the use of computers in government (Grönlund & Horan, 2005); and indeed the field of information systems (IS) has studied its use in public administration since the 1970s (Hirschheim & Klein, 2012). At the outset, e-government is here broadly defined as the use of ICT in public administration and government (see Bannister & Connolly, 2012). While the purpose here is not to settle the issue on how to define e-government, the results from the current literature review show a need for a continued and careful attention to how we should understand and study the phenomenon of e-government. More in particular, the argument here relates to the points made by Yıldız (2012) on the poor connection between e-government and the nature of public administration – although his discussion does not mention that there has actually been several important suggestions on how public administration and new information technology can be studied (see Lenk, 2007, 2012; Lenk et al., 2002). There is thus some potentially central work and arguments to be made on how research, and not least benchmarks for e-government, need to be sensitive to the context and purpose of public administration. This entails closer attention to the peculiar setting of public administration and on what public administration does: its purpose and administrative operation (see Lenk, 2007, 2012; Lenk et al., 2002).

The next chapter discusses the relationship between the concept of benchmark and e-government. Chapter 3 explains how the articles were identified and the purpose of the chosen method. Chapter 4 provides a description and summary of the articles in accordance with the three research questions and ends with answering the three questions respectively. Chapter 5 discusses the implications of the findings for practitioners and researchers on benchmarks for e-government. The conclusion ends the article by revisiting the answers to the questions and the implications of the findings.

2.E-government and the concept of benchmark

In its origin, benchmark is usually attributed to the photocopier industry in the late 1970s where it was used to gain a competitive advantage in industrial processes by searching for best practice and making production and design more efficient (see Freytag & Hollensen, 2001; Yasin, 2002). Anand and Kodali (2008) provide an overview of the literature on benchmarks and show how the definition of the concept varies tremendously and cites one source finding 49 definitions of the term. Some common themes, however, are “measurement, comparison, identification of best practices, implementation and improvement” (Anand & Kodali, 2008, p. 258). As another study puts it, benchmarks in the private sector can be used by firms to measure their “[…] strategies and performance against [the] ‘best in class firms’ […]” with the intention of identifying “[…] best practices that can be adopted and implemented by the organization” in order to improve performance (Freytag & Hollensen, 2001, p. 25).

Benchmarking and performance measurement started to take root in the public sector as a way to document results and provide tools for increased performance and transparency (see de Bruijn, 2002). The earliest research on the phenomenon of benchmarking within the public sector more generally has its origins in the early days of the 1990s (Braadbaart & Yusnandarshah, 2008), while the introduction of this type of measurement in the public sector is associated with the implementation of New Public Management (NPM) and a belief in the benign effects of a result-driven public sector already in the 1980s (Bjørnholt & Larsen, 2014; Bouckaert & Pollitt, 2000). It is also argued that performance measurements are the result of a particular combination of NPM and, among other, digital technologies in the form of e-government aiming at a transformation of the public sector (see Lapsley, 2009).

Benchmarks of e-government emerged at the end of the 1990s. They have since then proliferated at such an extent, that scholars studying them have been heavily criticised for a lack of definition of the term benchmark (Bogdanoska Jovanovska, 2016). This stretch of the term is perhaps understandable, given the variability of available benchmarks and its wide-reaching core themes of measurement and comparison. Benchmarks of e-government tend to consist of a combination of broad macro-factors such as internet infrastructure, levels of education in the population, and the quality of web-pages and e-services, and besides being called benchmarks they can also be referred to as surveys, e-readiness index and/or maturity index (cf. Janssen et al., 2004; Obi & Iwasaki, 2010; Ojo et al., 2007; Potnis & Pardo, 2011; Salem, 2007; Vintar & Nograšek, 2010). A few examples of these are Daniel West/Brown University’s e-government ranking (see e.g. West, 2005), the European Union’s (EU) eEurope eGovernment benchmark, the United Nation’s (UN) e-government survey, and Waseda International’s e-government Ranking.

Besides the quest for benchmark’s to find “the best” practice, efforts have also been directed toward learning from the “best in the class” in order to copy and use these practices in one’s organisation – via the term benchlearning (Freytag & Hollensen, 2001, p. 26). This is a more qualitative approach and has been picked up in research on e-government, were the results from benchmarks are put into practice: via learning and sharing of experiences, as seen in the case of providing assistance to developing countries (Kromidha, 2012). Another study developed a benchlearning methodology to help improve e-services in local government, and found benchlearning and its emphasis on learning and sharing experiences benign for improving e-services (Batlle-Montserrat et al., 2016). This crucial point of being able to learn from benchmarks, is succinctly expressed by Ammons (1999, pp. 108–109):

The idea behind benchmarking is not simply how an organization stacks up. Instead, the fundamental idea is captured by two questions: (1) What did we learn? and (2) How will we use what we have learned to make us better?

Viewed from a broader perspective, benchmarking and benchlearning can thus be incorporated into the wider field of “evaluation research” and design research, with methods such as action research, as well as other types of assessment frameworks. It is argued here that the key is to combine, among other things, the idea of evaluation, stringency and sensitivity to contexts with the importance of learning and problem-solving. This idea can complement and help the current discussion on benchmarking e-government in important ways, and which will be elaborated more on in the discussion – see Section 5.2.

With the existence of a plethora of benchmarks historically, and currently, in use there will be differentiating expectations of what is considered to be the “best” way of conducting e-government. Not to mention different commercial and political agendas influencing the purpose and construction of benchmarks – something which in turn will effect decision makers, practitioners and bureaucrats and consequently have political and financial effects for governments. Benchmark is used in this paper as an umbrella-term for the practice of international organisations, universities and multinational organizations to e.g. assess, rank, evaluate and index how well countries are faring in the realm of e-government. In this study the concept of benchmark is understood as a type of method for assessing performance, which means it is conducted under different assumptions and normative ideas of what is considered to be the “best” means and/or techniques for achieving the full potential of e-government. These assumptions form the basis for assessment and comparisons by ways of quantification and ranking, with the purpose of “helping” governments by assessing their standing and pointing towards how they can become better.

In summary, the phenomenon of wanting to assess and quantify the performance of a particular area – in this case e-government – in all its various forms and purposes, seems to be part of a relatively large and ongoing historical and social process which can be seen in many different parts of society as well as in many parts of the globe. Not least in areas such as health-care, higher education, business and industry. With the prevalence of the “measurement-industry”, and the frequency of different methods for assessing digitalization in various areas both public and private, this field is potentially enormous. Given the extensive use of benchmarks by major and important international organisations and companies, it becomes highly interesting to see what research has had to say about this phenomenon in the case of e-government. Relevant questions are therefore: what are the main findings found by research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government? According to research, what – if any – are the benefits for the public sector in using benchmarks of e-government? And in what way has research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government changed over time?

3.Material and method

This study is an integrative critical review of the research on benchmarking e-government during the years 2003 to 2016. This review can be characterised as following in a tradition of research reviewing and scrutinising different available ways of measuring e-government and digitalisation (see e.g. De Brí & Bannister, 2015; Magnusson, 2017; Wendler, 2012).

Over thirty years ago, with his taxonomy of literature reviews, Cooper (1988) illustrated that there are many different ways of doing them. The current method takes its cue from the Webster and Watson (2002) method of systematic search when conducting a literature review. In Webster and Watson’s perspective the purpose of conducting a literature study is to achieve two things – either reviewing the literature to produce theory and conceptual models, or looking at a new phenomenon and “exposing it” to theory (Webster & Watson, 2002, p. xiv). A literature review, however, can perform more tasks than this.

In the journal Human Resource Development Review, there has been a discussion on what separates literature reviews written for the purpose of generating theory and concepts, and those written for the purpose of integrating the literature into a topic (Callahan, 2010; Rocco & Plakhotnik, 2009; Torraco, 2005). This study is an integrative literature review that focuses on combining, critiquing and studying “[r]epresentative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated” (Torraco, 2005, p. 356). As the title for this study suggests, there is also a critical dimension to this review. This aspect has to do with scrutinizing current assumptions (Alvesson & Sandberg, 2013) about measuring e-government in order to promote new perspectives.

3.1The literature review process

The journal articles and conference papers where delimited in a process consisting of five steps. The first step determined the relevance of which central concepts to use. This study concerns e-government and based on previous research the definition of this term varies. At least nine variances of the central concept are found,11 based both on previous discussions on the term e-government (see e.g. Grönlund, 2005a, 2005b; Grönlund & Horan, 2005; Heeks & Bailur, 2007) and the authors’ professional experiences from the field of e-government. A simple search for each term was carried out in the two major databases for IS: Scopus and Web of Science to see the frequency of each term. Using the results and the understanding from previous literature, the three most frequent terms were chosen to be included in the search.22 The latter delimitation was a simple matter of keeping the number of searches to a manageable amount. However, in order to make sure that any possible further studies were not missed, step five of the search processes included studying the references of each article for further studies that might be relevant. This gave no further results and this study therefore draws the conclusion that including more search-terms would not yield further relevant findings. Furthermore, these three core terms are also found to corroborate with the most common terms used in major benchmarks of e-government such as those conducted by the UN, EU, Brown University and Waseda University.

The next step was to find key terms for describing the type of phenomenon of interest. Six terms were given from the start: benchmark, ranking, index, indicator, performance and assessment. Looking at the research on the term benchmark, these concepts can be seen as apt alternatives. All terms, except perhaps assessment, were also derived when looking at some of the most common large international benchmarks of e-government. As in the case of the previous three concepts, it is argued here that by studying the reference-list of the articles finally included in the review should have shown further relevant studies. The third step was to combine the three key-terms with each of the central concepts while executing searches in the two databases respectively. For example e-government AND ranking, electronic government AND index et cetera. This meant 36 searches which yielded 3,590 hits.

In the fourth step the study proceeded by reading the abstracts with the purpose of getting an immediate overview. The main inclusion criterion was to look at journal articles and conference papers written in English that deal with the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government. This focus on the meta-discussion on international rankings and indexes for e-government excludes studies creating their own methods for measuring e-government, or that, for example, assess the economic impact of e-government or look at other effects of e-government and why various e-government projects fail or succeed. It also excludes studies that in passing mention the phenomenon of measuring e-government without this being the main focus. This process left a total of 83 articles and conference papers of possible relevance.

The fifth step meant getting a deeper knowledge of the remaining articles. In practice this entailed another reading of all the abstracts, together with a scan of the main tenets of the content and the conclusion. Articles excluded include those where only the abstract was written in English, and studies that anchored their work in a broad background of measuring e-government but then proceeded to develop a new model and applying it to a certain country or region. This process resulted in the final 27 articles.

These remaining articles were then read in full. The content was sorted in a table that includes three columns (one for each question) and a row for each article (the items). The items were read in chronological order while noting the major findings, and the possible benefits for public sector in the respective columns. The analysis proceeded by comparing how the main findings have changed over time and adding these observations in the final column (for a more detailed view of the findings see appendix “Main findings of research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government 2003 to 2016”).

A literature review comes with some important limitations. This has to do with the fact that the answers to the questions in this research are based on what researchers have written on this topic. This means that conclusions drawn e.g. in the “grey literature” or other work done in the public sector are not included.

4.Evaluating the evaluators – Research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government

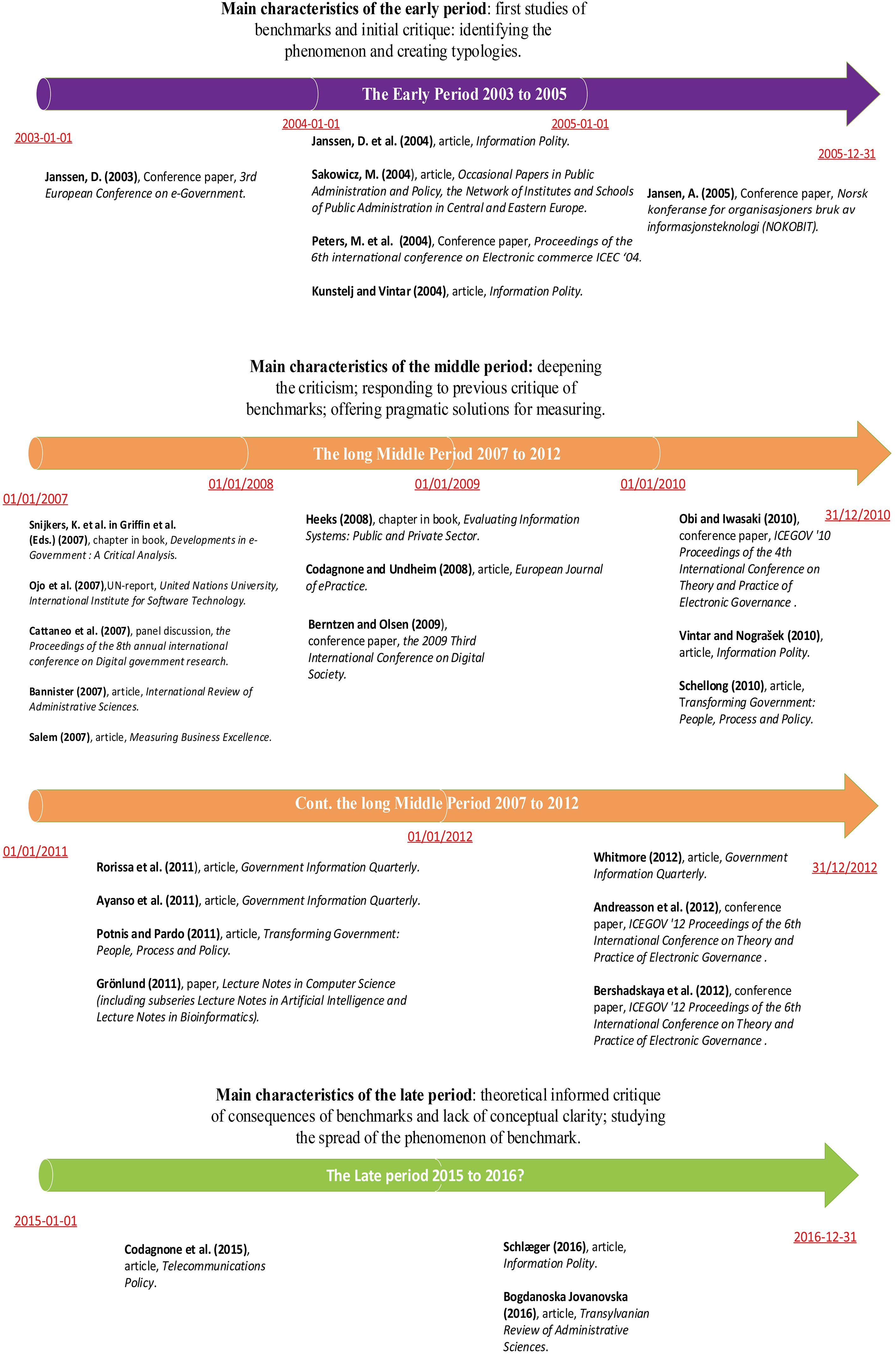

Chronologically the research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government is arranged into three periods. Each period is demarcated by how the research changes over time and that there is a natural gap between each era. The first period stretches from 2003 until 2005, the second begins in 2007 and ends in 2012. The third period starts with an article published in 2015 and continues to 2016. The periods should not be viewed as completely separated from each other, or mutually exclusive, but as a continuation of arguments and research done across time. The differences between each period are relevant, however, and are shown in the following figure, as well as in the review of the literature and in the appendix.

Figure 1.

An overview of research on benchmarking e-government.

4.1Waking up to benchmarking e-government – The early period 2003 to 2005

The timing of Janssen’s (2003) research on benchmarking e-government is no coincidence. By the time of his research there had been at least three major measurements carried out since 2001: the EU’s benchmarking of its member states’ public services by Capgemini, the UN’s e-government survey and the Daniel West/Brown University Global e-government survey.

Janssen studies how benchmarks can “influence” or “frustrate” the development of e-government (Janssen, 2003, p. 1). The main issues and findings discussed by Janssen in 2003 are developed further in later studies together with colleagues (Janssen et al., 2004; Snijkers et al., 2007), and will “set the tone” in terms of the core and reoccurring issues and outcomes for subsequent scholars. It is therefore worth summarising his seven points of criticism on the two benchmarks he studied:

• Too much focus on the offering of electronic services (supply-side), and too little or none at all on the use of services (demand side) (Janssen, 2003, p. 5);

• Lack of purpose and definition of e-government in relationship to what is measured (p. 6);

• Focusing only on supply-side of e-government neglects the more qualitatively important back-office processes (pp. 6–7);

• Problem of longitudinal comparability due to changing methodology (ibid.);

• The logic behind the scoring of the degree of possible interactions with e-services lacks the transformative dimensions of e-government and runs the risk of being out-dated with technological advancement (p. 8);

• Studies focus only on services offered at the national level while ignoring the regional levels (p. 9) and;

• No consideration given to the level of social inclusiveness of the e-services (ibid.).

A year later Information Polity (IP) publishes two articles on the topic of benchmarking e-government and in the editorial Taylor (2004, p. 119) refers to the articles as critical engagements with “[…] measurement regimes in e-government, regimes which purport systematically to delineate e-government.” One of these articles is by Janssen et al. (2004) who review 18 “international comparative eGovernment studies”.

Their review includes a conceptual framework for how to categorize the various benchmarks, and they raise a number of concerns. One of these is how the overt focus on output indicators risks impacting e-government policy to only focus on “[…] front-office realisations” (Janssen et al., 2004, p. 128). They make a point of how this risks neglecting other, perhaps more important, potentials of e-government such as information-sharing between different public sector entities and the aspect of more efficient or better back-office integration. The authors recommend careful evaluation of the results from the benchmark and hint at the sensibility of avoiding their dictates.

The second article in IP identifies 41 different approaches to “[…] monitoring e-government development […]” (Kunstelj & Vintar, 2004, p. 135). These include international country rankings, intra-country and regional comparisons and even scholarly work, which is a significant difference in definition of the field from Janssen et al. (2004).

One main finding identified by Kunstelj and Vintar is about how a majority of studies apply a too narrow definition of e-government. They also find a lack of theory behind the measurements that can provide a holistic and overall assessment of e-government. More crucially, they find no assessment of back-office integration or transformative potentials such as services tailored around citizens’ needs and challenges (Kunstelj & Vintar, 2004).

Two other articles also published in 2004 are by Peters et al. (2004) and Sakowicz (2004). Peters et al. are the first to provide an overview of the literature of measurements into three broad areas: stage-models studies, service literature and performance indicators (Peters et al., 2004, p. 482). Among other, they conclude that measurements are too simple and lack theoretical underpinning that allows for a richer picture of e-government, as well as noting that the measurements are too focused on assessing e-services (Peters et al., 2004, p. 487). Sakowicz’ (2004) mentions 10 different examples of methods for evaluation/benchmarking e-government and discusses their usefulness for countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). He concludes, among other, that the indicators are too focused on technology and supply-side and missing crucial aspects such as user needs and how technology makes people more engaged. This seems to leave him sceptical of the expediency of these benchmarks for e-government development in general, and CEE-countries in particular.

The last article in this early period is Jansen (2005) who looks mainly at the benchmarks from the UN and the EU with local examples from Norway. What sets Jansen apart from the other early commentators in this field is his insistence on the importance of taking the national context into account which he argues is lacking in current benchmarks. Existing indicators are not able to capture the importance of coping with different conflicts of interests when it comes to “national ICT programs” (Jansen, 2005, p. 10).

While commenting on their findings, none of the articles from this period seems to explicitly mention benefits for the public sector in using benchmarks for e-government. This aspect is of course hard to pin-point since the authors are not always assessing how beneficial the benchmarks actually are via e.g. empirical studies, but are rather doing so indirectly by scrutinizing the benchmarks. The exception here being Kunstelj and Vintar (2004, p. 131) who conclude that the overt focus on measuring electronic services has led to “ […] a significant slowdown of development in most countries” (Kunstelj & Vintar, 2004, p. 131). Others discuss how these rankings and surveys promote a context where “short terms [sic] results” are pursued instead of long term effects, which in turn can create risks of poor infrastructure and security (Jansen, 2005, p. 10).

4.2Deepening the criticism and offering pragmatic solutions – The middle period 2007 to 2012

This period is characterised by two broad developments. The first is how scholars continue to expand and develop the criticism offered in the early period and widening this critique – but also highlighting minor benefits. The second is that there is a focus on the history of the phenomenon of benchmarking, and quantitative research that scrutinizes the methodology of the most common benchmarks and offering solutions on how to improve measurements and indicators.

4.2.1The years 2007 to 2008

In 2007 Janssen and colleagues (in Snijkers et al., 2007) return to the topic of critically reviewing benchmarks. As in their previous article from 2004 (Janssen et al., 2004) they examine the same 18 benchmarks using the same conceptual model. One of the interesting novelties here is their discussion of benchmarking as a phenomenon itself, and giving a historical background of benchmarks in the private sector dating back to the 1950’s Japan (Snijkers et al., 2007, p. 73 ff.). Another novelty worth mentioning is the fact that their second study of the same benchmarks three years later leads them to different conclusions. In brief, they see a change in the benchmarks over time: the period 2000 to 2003 mainly looks at front-office services and websites, and from 2004 they find the emergence of some benchmarks starting to look at aspects such as strategy and back-office processes (Snijkers et al., 2007, pp. 83–84).

Continuing on their conference paper from 2005, Ojo et al. (2007) provide a quantitative and systematic assessment of benchmarks. They conduct a comparative study of the indicators in a series surveys produced from 2001 to 2004 on e-government from the UN, Accenture and Brown University. Ojo et al. conclude, like Jansen (2005), that there is a lack of indicators catering to the importance of context, and they find that these benchmarks – except for the UN benchmark which is more comprehensive – mostly assess websites and e-services (Ojo et al., 2007). Another example, this time from a panel-discussion with academics and consultants regarding the experiences from benchmarking and measuring e-government in the EU, found some main issues to be compliance from member-states in providing data, defining common indicators, too much focus on ranking rather than learning from experiences and the well-known problem of benchmarks only focusing on supply-side (Cattaneo et al., 2007).

A significant contribution to the field comes via a synthesis of the core issues and a sharpening of the debate with Bannister (2007), who argues, among other, that the studied benchmark-methods are not reliable for gauging progress. Like previous researchers in this field, echoing perhaps most clearly the criticism from Kunstelj and Vintar (2004), he is sceptical of the focus on output-indicators and affirms that they “[…] risk distorting government policies as countries may chase the benchmark rather than looking at real local and national needs” (Bannister, 2007, p. 185).

Studying 44 different reports from 10 actors conducting benchmarks Salem (2007, p. 9) concludes, that these types of rankings have an “imperative role in driving e-government development […]”, on condition that that they are coupled with the ability of reform and long-term commitment. One main concern for Salem seems to be the lack of a theory of e-government underlying the benchmarks in order to help measure and govern e-government progress. Due to the existence of different methodologies and ways of benchmarking e-government, he also hints at the possible relativity of the results, and questions the usefulness of the results as an indication of good e-government (Salem, 2007).

In 2008, Heeks (2008) offers a guide on how to construct benchmarks and measurements of e-government, but at the same time he takes the opportunity to comment on the use of international rankings of e-government. Regarding the issues with the current practice of benchmarking e-government, Heeks (2008) relates to past research on how there is a too narrow focus on e-services for citizens and he also highlights the lack of measurements regarding e-services for businesses. In addition, Heeks (2008, pp. 261, 274) provides an example based on an anonymous source on how politicians put high emphasis on solely wanting to improve a country’s standing in a ranking, and given the potential problems with benchmarks, this risks leading to the wrong political decisions.

In the same year of 2008 Codagnone and Undheim (2008) discuss the merits and flaws of the EU eGovernment benchmark, with some examples from Accenture and UN. The authors notice the mounting criticism of benchmarking e-government coming from the scholarly field and are the first to respond to this criticism by engaging with the possible merits of benchmarking (Codagnone & Undheim, 2008). Their arguments, based on the case of the EU e-government benchmark, revolve around emphasising how it is widely used and accepted, simple, fairly transparent and replicable (Codagnone & Undheim, 2008).

The researchers in this period tilt slightly in the direction of that there are some benefits for the public sector. Ojo et al. (2007, p. 1) see the assessment of e-government readiness in itself as a “necessary condition” for advancing e-government, and indeed “crucial for advancing e-government” (Ojo et al., 2007, p. 9). Even Bannister, based on his assertion that scholars agree that e-government is a good thing, is among the first to explicitly argue for the positive sides of benchmarking in the public sector and as a way to focus political attention on the need for “e-government services” (Bannister, 2007, p. 185). Salem finds that benchmarks can be benign under the right circumstances, but at the same time he remains cynical in his observation that countries with a good score can use this as “[…] an indication of their success, no matter how flawed the benchmarking methodology is” (Salem, 2007, p. 19).

Neither Snijkers et al. (2007) nor Cattaneo et al. (2007) discuss possible benefits, and in the latter case they instead put forward amble examples of issues that have arisen during the years of benchmarking e-government within the EU. More direct and fundamental critique is given by Heeks (2008) who notes that there is scarce evidence that there is a demand for benchmarking studies at all. More importantly, and the first one to explicitly do so, he argues that there seems to be lacking key questions regarding how data from e-government benchmarking studies are used, which limits the ability to evaluate the value of these studies (Heeks, 2008).

4.2.2The years 2009 to 2010

Berntzen and Olsen (2009) compare three international benchmarks of e-government – namely Accenture e-government leadership, Brown University global e-government ranking and the UN’s e-government ranking. Although the authors begin by defining electronic government as the offering of electronic services to citizens and business (Berntzen & Olsen, 2009, p. 77), they at the same time find it problematic that benchmarks of electronic government are mainly supply oriented and lacking indicators for how services are perceived or how well integrated they are with back-office systems (see Berntzen & Olsen, 2009, p. 81). And as in previous research, they also note the absence of measuring local and regional levels of e-services.

Another e-government benchmark in use is the Waseda University e-Gov ranking (Obi & Iwasaki, 2010). Obi and Iwasaki discuss the merits of this method for ranking-government, and they are the first to acknowledge the role of management in being able to deal with implementing the fundamental change that comes with bringing about e-government, as well as being able to foster innovation in the social, economic, political and organizational spheres (Obi & Iwasaki, 2010).

Vintar and Nograšek (2010) look at the case of Slovenia and asked the question “How can we trust different e-government surveys?” In contrast to the results presented in this literature-review, the authors in their conclusion claim that the academic literature is lacking of critical analysis of benchmarks. This discrepancy is perhaps due to the fact that they are not using the term benchmark to understand the phenomenon. Instead they use the term “survey”. While studying the eEurope/Capgemini benchmark; the UN e-government ranking; Brown University global e-government ranking and the Economist e-readiness ranking, Vintar and Nograšek find that the scope of each survey is too narrow to provide “[…] solid and reliable information for an evaluation of the state of the art of e-government in a selected county [sic]” (Vintar & Nograšek, 2010, p. 212). As an alternative they argue that the most relevant picture of e-government in a country is best approached by sensibly combining the various surveys (ibid).

Schellong (2010) discusses the EU eEurope benchmark and reviews it together with the UN e-government ranking and the West/Brown University benchmark. One of his conclusions has to do with how benchmarks tend to focus on national levels to the detriment of countries with a federal state structure, in which many services are created at regional/local levels (Schellong, 2010). Another finding is how the measurements primarily focus on supply-side and how developed e-government services are, and that there is an over-reliance on measuring these indicators leading to an inability in capturing “[…] the expected transformative effects of ICT on government” (Schellong, 2010, p. 379).

Returning to the aspect of possible benefits for the public sector, Obi and Iwasaki (2010) have the most positive view. Their argument is based on the premise that since e-government is complex, benchmarking can highlight the key indicators necessary to understand in order to manage e-government. Berntzen and Olsen (2009) also see potential benefits from benchmarks as a way for public sector to keep track of the increasing number of e-government services and find best practices.

Schellong (2010) makes several suggestions on how to improve the EU e-government benchmark, and thus seems to hold an implicit positive view that if the benchmark is improved, or constructed differently, it can be of more use for public administration. Vintar and Nograşek (2010, p. 209) stress the importance of using the results of benchmarks as “policy-informing” rather than “policy-determining”. Relying on work by Bannister (2007) and Jansen (2005), they put forth that results from benchmarking foster governments to focus only on services as a way of getting a high rank and being perceived as modern (Vintar & Nograşek, 2010). They even argue that the CapGemini benchmark caused “some negative side effects” in the case of Slovenia, due to the administration focusing on improving their benchmark standing rather than areas that are potentially more important (Vintar & Nograşek, 2010, pp. 211–212).

4.2.3The years 2011 to 2012

The journal Government Information Quarterly (GIQ) picks up on the research on benchmarks by publishing two articles on the topic in 2011. The first article is by Rorissa et al. (2011) consider six different ways of computing indexes for e-government and apply Daniel West’s (2005) framework for how to measure supply, or output, of a government’s web presence. This study is an example of the category of scholars who have a pragmatic approach to the study of benchmarks and employ quantitative techniques to help improve benchmarks with the purpose of aiding the development of e-government. One of the major issues they mention regarding e-government ranking and index, is that they do not differentiate between static websites and integrated portals (Rorissa et al., 2011). In the second article about benchmarking e-government published by GIQ, Ayanso et al. (2011) looks closer at the UN e-government index and reveal a need for validating the indicators of the index empirically to determine “[…] whether or not they truly represent the observed phenomenon […]” (Ayanso et al., 2011, p. 531).

In addition, four other articles are published that deal with various aspects of benchmarking e-government by the UN (Andreasson et al., 2012; Grönlund, 2011; Potnis & Pardo, 2011; Whitmore, 2012). Grönlund (2011) concentrates on the UN eParticipation index and finds, among other things, that the index does not at all measure real levels of democracy, because as it turns out “[…] very undemocratic countries can score high on UN eParticipation” (Grönlund, 2011, p. 35). Whitmore (2012) argues that factor analysis gives many benefits over the existing ways employed by the UN e-government ranking. In a case-study mapping the development of the UN e-government ranking, Potnis and Pardo (2011) conclude, among other, that an overemphasis on technology without considering human abilities to utilize technology, can strengthen the digital divide between developed and developing countries. The main concerns offered by Andreasson et al. (2012) push for introducing new technologies to improve measurements, e.g. providing policy-makers with real-time data, and adding gauges for government performance, security, and transparency.

In a brief article Bershadskaya et al. (2012) look at the e-government rankings of Waseda and the UN and contend that not all indicators are relevant depending on the context of certain countries.

Regarding the question of possible benefits of using benchmarks for e-government, Rorissa et al. (2011) put forward three explicit examples: help in tracking progress, making priorities, and provide accountability. In their discussion they even add that “[…] grounded and broadly applicable ranking frameworks are crucial” for providing thorough decision making and policy (Rorissa et al., 2011, p. 360). Bannister (2007), as well as Kunstelj and Vintar (2004), are quoted and cited by Rorissa et al. (2011, p. 356) as neutral commentators on benchmarks, and more specifically state that they are arguing for potentially significant practical impact on economy and politics (Bannister) and in general that they can impact e-government services (Kunstelj & Vintar). For the sake of clarity it should be stressed here that Bannister’s point is to warn about the risks of poor handling of current benchmarks, and in the case of Kunstelj and Vintar they are maintaining a general criticism of practices of benchmarking e-government.

Potnis and Pardo (2011) mention how benchmarks can work as potential feedback loops for learning and measuring e-government. Both Ayanso et al. (2011) and Andreasson et al. (2012) argue for different ways of improving benchmarks, such as using new technology as methodology for measuring e-government. Another positive perspective on benchmarks is the unorthodox stance by Bershadskaya et al. (2012) who do not view the supply-side oriented measurement of the EU benchmark as a problem and they suggest it can be – with some modifications – appropriate to use in the case of Russia.

Grönlund (2011) is clearly very sceptical of the benchmark he studies and seems to see little or no benefits of using it, while Whitmore (2012) argues extensively for technical changes to methodology, but does not, however, show how this can benefit the public sector or the targeted users of the results.

4.3Theoretically and conceptually informed critique – The late period 2015 to 2016

The final period is characterised by theoretically informed criticism coupled with empirical examples, and a move towards criticising past research for lack of conceptual clarity. An example of the former type of research is Codagnone et al. (2015) who studies the case of the EU and the consequences of using the eEurope benchmark. The authors find that the benchmark creates a large-scale process of government institutions copying each other in what is perceived as success, in pursuit of climbing the ranking-system, and actors imitating each other in this way risk hindering the introduction of new practice (Codagnone et al., 2015). Another critical concern they assert is that “the policy prominence retained by supply-side benchmarking of e-government has probably indirectly limited efforts made to measure and evaluate more tangible impacts” (Codagnone et al., 2015, p. 305).

A different approach to the topic is Schlæger (2016) who looks at e-government benchmarking in China. Observing the criticism of supply-side benchmarks, and how research views benchmarks as problematic, the case of China shows attempts both at measuring back-office processes and a positive view on the use of benchmarks to improve e-government. Benchmarking is even a key area in research on e-government (Zhang et al. referenced in Schlæger, 2016, p. 386).

The last article in this review is Bogdanoska Jovanovska (2016). The author finds a lack of clear demarcation of what she refers to as the study of e-government assessment. This is the only article discussing the problem of defining the area and who recognises the use of many different terms, and the author contends that these terms are used “wrongly as synonyms” by researchers (Bogdanoska Jovanovska, 2016, p. 31). Having made this important remark there is no clarification, and therefore a high degree of uncertainty, as to what the preferred term or terms may be.

Based on their suggestion for improvements, Codagnone et al. (2015) are interpreted as holding an implicit assumption that benchmarks for e-government can be useful, but in relation to the current practice and empirical examples and perspective of the EU-benchmark, they are very sceptical. Schlaeger, on the other hand, listens attentively to scholars arguing for the positive sides of benchmarking in China, but the reader is not given any proof or signs of questioning these assertions. Leaving the question of possible benefits out of the picture altogether is Bogdanoska Jovanovska (2016) and who instead discusses the issue in current practices of benchmarking e-government regarding the lack of indicators and frameworks for measuring back-office processes.

4.4Answering the questions

Having reviewed the literature from the perspective of the three questions posed in chapter two, the following three sections will provide answers to each of the questions.

4.4.1Main findings

The literature review reveals that criticism of benchmarks varies from pointing out how they can mislead policy (Bannister, 2007), to fundamental critique of how major benchmarking instruments fail in being able to capture the factors that potentially have transformative effects (Janssen, 2003; Schellong, 2010). There are several methodological, practical and theoretical problems in the current practices of benchmarking e-government – and researchers grapple with how to devise different types of indicators for benchmarks. These suggestions revolve around how to improved methodology and the operationalisation of key-terms to keep pace with technological advancements, as well as how to compete with a superfluity of available benchmark and measurement practices. Empirical studies of the consequences of benchmarks show how they can have detrimental effects on the development of e-government. Research also reveals negative effects of benchmarks for the development of e-government due to a narrow frame of definition, and how this leads to the risk of hindering innovation and the risk of having countries copying each other without regard to context; drawing attention to the wrong e-government policies.

4.4.2Benefits for the public sector

Based on the findings in this study, there are relatively few examples of benefits of benchmarks for the public sector, and the ones that exist are based on assumptions that benchmarks in themselves are a good thing (see e.g. Rorissa et al., 2011). Many times there is no overt criticism of the practice of benchmarking itself, but on the ways in which it is currently being conducted (see e.g. Andreasson et al., 2012; Janssen et al., 2004). The research included in this literature review does not provide any empirical findings showing that the public sector has benefited from benchmarking e-government. The studies looking at the empirical results of using benchmarks warn against using current practices of benchmarks and provide empirical examples of their negative effects (see e.g. Vintar & Nograšek, 2010). Others are sceptical if there even are any “real” changes “[…] in quality and utility of e-government services” contributed by e.g. the EU benchmarking (Codagnone et al., 2015, p. 305 cursive in original).

Even though the studied research has not found any clear positive effects of using benchmarks for enhancing e-government this does not mean that these effects do not exist. This needs to be considered in future developments and use of benchmarks for e-government in order to help public sector improve and make the best of e-government. More emphasis is thus needed from actors behind the construction of and advocates for benchmarks to explain and show how these benchmarks can be useful. There is also a need for clear recognition of the balancing act between the cost of implementing a benchmark and its potential benefits (see Heeks, 2008). There seems to be a short supply of examples of good practices stemming from the use of benchmarks. These points for improvements display how the current use of benchmarks for e-government in certain regards mainly are political tools for showing off “progress” rather than measuring significant and important changes.

4.4.3Change over time

Research on benchmarks for e-government has matured and changed over the years. Initially researchers developed taxonomies and systematic reviews of a large number of benchmarks and scrutinised the methodology; while in the middle period they focused on the historical background of benchmarks. This latter period also shows attempts to answer the main criticisms of benchmarking e-government and there is a deepening of the criticism of benchmarks. From the middle period there are further attempts to clarify, improve and criticise the current quantitative methods for benchmarking e-government. The latest development is a critique on the lack of conceptual clarity, a study on the use of benchmarks in China and theoretically informed criticism of the negative consequences for the development of e-government.

Although change has taken place, many things have a remarkable way of remaining the same. The same criticism, for example, keeps recurring again and again: too many supply-oriented benchmarks, the importance of context and measuring regional levels, and the lack of not measuring back-office processes. This could be interpreted as the result of a lack of engagement with other researchers in the research community. The absence of interest in engaging with arguments and results of previous scholars, and a disregard for the purpose of accumulating knowledge, offers no ways that can move the research forward.

5.Implications for practitioners and researchers on benchmarks for e-government

Conducting a literature-review – as opposed to constructing a new theory or doing an empirical investigation – does not directly entail producing something completely novel: the results and identified gaps are after all very much based on past research. The main purpose and contribution of a study such as the current one is to combine and present past knowledge in a coherent and aggregated way, while using critical judgement to put different perspectives on a matter by discussing how benchmark practitioners and research can progress and identify potential research gaps that need to be filled.

This discussion will therefore continue in two steps. Firstly, by giving a general characterisation on the research included in this literature review. Secondly, it is argued that the implications of this study for practitioners, as well as researchers on benchmarking e-government, merits three considerations for further discussion. The initial two of these considerations has to do, on the one hand, with the relation between e-government and the nature of public administration, and on the other hand, between benchmarks as a method for promoting “best practice” in relation to such a complex phenomenon as e-government. Taking these two considerations together, the third aspect to consider is how benchmarks can be improved, and/or how researchers on e-government can conduct other methods that promotes both research on e-government and help the public sector improve e-government.

5.1A general characterisation of research on benchmarks for e-government

The research found in this literature review resembles the conclusion of Heeks and Bailur (2007) concerning research on e-government more generally as that of a “fragmented adhocracy”. This means a condition where there is “[…] limited functional dependence of using the findings of earlier work; limited strategic dependence of researchers needing to convince peers of the importance of their work; and high strategic task uncertainty in terms of prioritized problems to research” (Heeks & Bailur, 2007, pp. 260–261). On a more general level, this lack of common engagement with promoting knowledge and communication between researchers to advance and solve problems – instead of monologues – has also been put forward as a problem for social science as a whole (see Alvesson et al., 2017).

Three brief examples can be given in order to strengthen this point. One is how research on benchmarks takes place in silos with no significant engagement between researchers on the phenomenon being studied in terms of following up on previous findings or trying to solve critical conclusions. There are, of course, instances of referencing to past studies, but not as a way of accumulating knowledge in order to constructively build on previous findings or relate to empirical results. Another clear example is the constant repetition of the same criticism and the lack of a common conceptual theme or research agenda. Thirdly, and with the possible exception of the general remarks by Bannister (2007) and Heeks (2008), there is a lack of calls for devising benchmarks that are tailored for the needs, and positive advancement of knowledge, that is situated in the context and purpose of the public sector.

5.2Benchmarks and beyond? Three thoughts for further discussion

Based on the results of the literature review, there are several questions and concerns still left to be discussed. While it is beyond the scope of this research to address all of them, the article will proceed by providing three additional thoughts for practitioners of benchmarks and researchers on e-government.

The first reflection is related to the understanding and definition of e-government discussed briefly in the introduction, and which is a reoccurring theme in the articles studied in this literature review. If the purpose of benchmarks is to promote “the best” way of conducting e-government, it is argued here that these benchmarks need to be more attuned to the context and purpose of the public sector. For example, rather than focusing on measuring what technological advancement can offer – there can be a firmer connection between what public sector is in general as opposed to the private sector and what it does in terms of public administration, and how new technology fits into this. As can be seen in the summary of the reviewed literature, scholars are generally aware of this issue and the typical answer to this problem is to point towards the importance of also measuring “back-office” processes. This might seem as a relevant response, but the problem could be more complex than this – what if the nature of public administration itself is left out? This is a point made by Yıldız (2012) in his survey of “big questions” within e-government research. One way of doing this more concretely is to see e-government in relation to the functions of a public administration – i.e. the processing of information and case handling, what Lenk (2012, p. 221) calls “the nuts and bolts of administrative action”. This means making an effort towards researching how the information is processed and used as part of the core-purpose of an organisation working under sometimes strict judicial demands, and studying the level of policy, as well as management and operatives (see e.g. Lenk, 2012, pp. 221, 223 and 226). In a nutshell, this requires a more realistic definition of e-government that acknowledges the challenges of ICT in public sector – not just what is deemed as the “best performance” – as well as how it can be applied to the benefit and improvement of a context signified by administrative action and high judicial demands.

The second reflection here has to do with the relation between the nature of the benchmark as a method of promoting “best practice” in the context of the often nebulous, and complex, phenomenon of e-government. Is it possible, or even relevant, to only measure what is “the best way” of conducting e-government? There are plenty of examples from the literature review of criticism of benchmarks and the lack of usefulness for the public sector. It could therefore be argued that there seems to be a need for benchmarks to be more attuned to empirical findings and cases of the use of ICT in the public sector – i.e. research that shows a complex, and far from overtly positive, picture (see e.g. Andersen et al., 2010; Bannister, 2012; Danziger & Andersen, 2002; Gauld et al., 2006).

Taking these arguments together into a third point, there seems to be some indication of a poor connection between the understanding of the context and function of public administration and benchmarks for e-government. A constructive solution to this situation can be to argue for the need for entirely new methods for developing e-government together with the public sector, or continuing the work on improving the benchmarks and complementing them with qualitative research. Both paths, improving the benchmarks or going for alternative methods, can benefit from building collaborations and cross-national studies aimed at directly helping to solve problems. These common efforts should be used to provide an open knowledge base for experts, civil servants and managers in public sector and help them tackle – or at least critically discuss – the challenges and possibilities of how digital technology can benefit public sector.

Besides the work already being carried out on improving the quantitative measures of benchmarks, another brief example of how to continue to improve benchmarks is to emphasise, and to a greater extent apply, the concept of benchlearning. The suggestion here is to create a framework within the practice of benchmarking allowing for collaboration between public administration and research, which can produce environments in which knowledge by researchers helps produce sound policy and promote sensible decision making.

An entirely different alternative to benchmarking – which does not necessarily have to exclude the previous suggestion – can be to pursue research done in the overall theme of pragmatism developed under the heading of action research (AR) (Baskerville, 1999; Baskerville & Myers, 2004; Baskerville & Wood-Harper, 1996). In this sense, for example, the five core principles of canonical action research (CAR) as detailed by Davison et al. (2004) is one way to go. CAR is an interesting alternative because of its synthesises of prior knowledge and experiences from preceding debates on the pros and cons of AR and it offers clear guideline in terms of what principles to follow (see Davison et al., 2004). In addition to this, CAR is a type of research design geared towards an iterative and collaborative process towards helping to produce new knowledge and sharper research questions than the ones currently provided. This would allow for the crucial importance of working in a problem-oriented way that is necessary for dealing with the complex matter of e-government. More in detail, the two core components of CAR are useful because:

First, by iterating through carefully planned and executed cycles of activities, so researchers can both develop an increasingly detailed picture of the problem situation and at the same time move closer to a solution to this problem. Second, by engaging in a continuous process of problem diagnosis, so the activities planned should always be relevant to the problem as it is currently understood and experienced. (Davison et al., 2004, p. 68)

AR and CAR are not the only alternative methods to the practice of benchmarking – there are many other potential candidates, and this is not the place to mention them all. The key concern here is to promote the need for more qualitative research that is problem-oriented and attuned to the complexities of new technology in the context of conducting public administration.

6.Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to look at what research has had to say about the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government. The questions set out to be answered were: what are the main findings found by research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government? According to research, what – if any – are the benefits for the public sector in using benchmarks of e-government? And in what way has research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government changed over time?

There are many examples of research on the phenomenon of benchmarking e-government that deems it theoretically, methodologically, and in practice, problematic. The results also show that some scholars hold an implicit assumption that some usefulness can be found, and there are some hypothetical examples of possible benefits from benchmarks. There is thus a need for more empirical studies, investigating positive effects of using benchmarks of e-government. Overall, the findings in this literature-review reveal how initial research created taxonomies of benchmarks and criticised them for being too focused on measuring online services. This research was followed by more criticism on how benchmarks can have a negative impact on e-government policy and development. During the same time-period there is research giving methodological support on how to improve ways of benchmarking. Later research offer more theoretically and conceptually informed critique of benchmark-studies.

Based on the findings, the third conclusion has to do with the implications for practitioners and researchers on benchmarks. The argument here is that benchmarks for e-government needs to be more sensitivity to both the context of public administration, and the inherit challenges of e-government. Some suggestions for addressing these issues is to apply more qualitative research in general, and benchlearning and action research in particular.

Notes

1 e-government, electronic government, e-governance, eGovernment, digital government, eGov, digital governance, innovative government, electronic governance.

2 The search was carried out 2018-02-22 and yielded the following results: e-government (13 679), electronic government (1 959), e-governance (1 882).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Swedish Transport Agency (Transportstyrelsen) for providing the funding to conduct this research as a PhD student at the department of Informatics, Örebro University.

References

[1] | Alvesson, M., Gabriel, Y., & Paulsen, R. ((2017) ). Return to Meaning: A Social Science with Something to Say: Oxford university press. |

[2] | Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. ((2013) ). Problematization as a Methodology for Generating Research Questions. In Constructing Research Questions: Doing Interesting Research. Retrieved from http://methods.sagepub.com/book/constructing-research-questions. doi: 10.4135/9781446270035. |

[3] | Ammons, D.N. ((1999) ). A proper mentality for benchmarking. Public Administration Review, 59: (2), 105-109. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/977630. doi: 10.2307/977630. |

[4] | Anand, G., & Kodali, R. ((2008) ). Benchmarking the benchmarking models. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 15: (3), 257-291. doi: 10.1108/14635770810876593. |

[5] | Andersen, K.N., Henriksen, H.Z., Medaglia, R., Danziger, J.N., Sannarnes, M.K., & Enemærke, M. ((2010) ). Fads and facts of e-government: A review of impacts of e-government (2003–2009). International Journal of Public Administration, 33: (11), 564-579. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-77956703894&doi=10.1080%2f01900692.2010.517724&partnerID=40&md5=fb4fa1c1332c6b17e6e8376678933097. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2010.517724. |

[6] | Andreasson, K., Millard, J., & Snaprud, M. ((2012) ). Evolving e-government benchmarking to better cover technology development and emerging societal needs. Paper presented at the ICEGOV ’12 Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Albany, New York, USA. |

[7] | Ayanso, A., Chatterjee, D., & Cho, D.I. ((2011) ). e-government readiness index: A methodology and analysis. Government Information Quarterly, 28: (4), 522-532. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-80053609150&doi=10.1016%2fj.giq.2011.02.004&partnerID=40&md5=06a3d6ff27f1c3099c7b32e719313c8b. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2011.02.004. |

[8] | Bannister, F. ((2007) ). The curse of the benchmark: An assessment of the validity and value of e-government comparisons. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 73: (2), 171-188. |

[9] | Bannister. F., & Connolly, R. ((2012) ). Forward to the past: Lessons for the future of e-government from the story so far. Information Polity, 17: (3-4), 211-226. |

[10] | Bannister, F. ((2012) ). Plus Ça Change? ICT and Structural Change in Government. In Donk, W.B.H.J.v.d., Thaens, M., & Snellen, I.T.M. (Eds.), Public Administration in the Information Age: Revisited (Innovation and the Public Sector) [Elektronisk resurs]: IOS Press. |

[11] | Baskerville, R.L. ((1999) ). Investigating information systems with action research. Commun. AIS, 2: (3es), 1-32. |

[12] | Baskerville, R.L., & Myers, M.D. ((2004) ). Special issue on action research in information systems: Making is research relevant to practice – foreword. MIS Quarterly, 28: (3), 329-335. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000223944700002. |

[13] | Baskerville, R.L., & Wood-Harper, A.T. ((1996) ). A critical perspective on action research as a method for information systems research. Journal of Information Technology, 11: (3), 235-246. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:A1996VL31600006. doi: 10.1080/026839696345289. |

[14] | Batlle-Montserrat, J., Blat, J., & Abadal, E. ((2016) ). Local e-government benchlearning: Impact analysis and applicability to smart cities benchmarking. Information Polity, 21: (1), 43. doi: 10.3233/IP-150366. |

[15] | Berntzen, L., & Olsen, M.G. ((2009) ). Benchmarking e-government - A Comparative Review of Three International Benchmarking Studies. Paper presented at the 2009 Third International Conference on Digital Society (1–7 Feb.). |

[16] | Bershadskaya, L., Chugunov, A., & Trutnev, D. ((2012) ). Monitoring methods of e-governance development assessment: Comparative analysis of international and russian experience. Paper presented at the ICEGOV ’12 Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Albany, New York, USA. |

[17] | Bjørnholt, B., & Larsen, F. ((2014) ). The politics of performance measurement: ‘Evaluation use as mediator for politics’. Evaluation, 20: (4), 400-411. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84908703039&doi=10.1177%2f1356389014551485&partnerID=40&md5=7fa247a451eac5118405a8f13d80c063. doi: 10.1177/1356389014551485. |

[18] | Bogdanoska Jovanovska, M. ((2016) ). Demarcation of the field of e-government assessment. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences (48E), 19-36. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000378111200002. |

[19] | Bouckaert, G., & Pollitt, C. ((2000) ). Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis. New York: Oxcord university press. |

[20] | Braadbaart, O., & Yusnandarshah, B. ((2008) ). Public sector benchmarking: A survey of scientific articles, 1990–2005. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74: (3), 421-433. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-53149101709&doi=10.1177%2f0020852308095311&partnerID=40&md5=ba9595ac855eb24b42e26b08b0675ca1. doi: 10.1177/0020852308095311. |

[21] | Callahan, J.L. ((2010) ). Constructing a manuscript: Distinguishing integrative literature reviews and conceptual and theory articles. Human Resource Development Review, 9: (3), 300-304. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-77955585778&doi=10.1177%2f1534484310371492&partnerID=40&md5=f1706966e44dc437e68a60da6bc07ddd. doi: 10.1177/1534484310371492. |

[22] | Cattaneo, G., Codagnone, C., Gáspár, P., Wauters, P., & Gareis, K. ((2007) ). Benchmarking and measuring digital government: lessons from the EU experience. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 8th annual international conference on Digital government research: bridging disciplines & domains, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. |

[23] | Codagnone, C., Misuraca, G., Savoldelli, A., & Lupiañez-Villanueva, F. ((2015) ). Institutional isomorphism, policy networks, and the analytical depreciation of measurement indicators: The case of the EU e-government benchmarking. Telecommunications Policy, 39: (3-4), 305-319. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84939970580&doi=10.1016%2fj.telpol.2015.01.005&partnerID=40&md5=8f60123b7362f8571b4ad567aac441e4. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2015.01.005. |

[24] | Codagnone, C., & Undheim, T.A. ((2008) ). Benchmarking eGovernment: Tools, theory, and practice. European Journal of ePractice, 1: (4), 1-15. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/epracticejournal/codagnone-undheim-presentation (accessed 2018-05-22). |

[25] | Cooper, H.M. ((1988) ). Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge in Society, 1: (1), 104-126. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0003140320&doi=10.1007%2fBF03177550&partnerID=40&md5=f02c16f363e1c7759ddbdab502007c91. doi: 10.1007/BF03177550. |

[26] | Danziger, J.N., & Andersen, K.V. ((2002) ). The impacts of information technology on public administration: An analysis of empirical research from the “Golden Age” of transformation. International Journal of Public Administration, 25: (5), 591-627. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-120003292. doi: 10.1081/PAD-120003292. |

[27] | Davison, R., Martinsons, M.G., & Kock, N. ((2004) ). Principles of canonical action research. Information Systems Journal, 14: (1), 65-86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2575.2004.00162.x. |

[28] | De Brí, F., & Bannister, F. ((2015) ). e-government stage models: A contextual critique. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. |

[29] | de Bruijn, H. ((2002) ). Performance measurement in the public sector: Strategies to cope with the risks of performance measurement. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 15: (6-7), 578-594. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0036029575&doi=10.1108%2f09513550210448607&partnerID=40&md5=09cbd198eab60f7906e9ceca7f151908. doi: 10.1108/09513550210448607. |

[30] | Freytag, P., & Hollensen, S. ((2001) ). The process of benchmarking, benchlearning and benchaction. The TQM Magazine, 13: (1), 25-34. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780110360624. doi: 10.1108/09544780110360624. |

[31] | Gauld, R., Dale, T., & Goldfinch, S. ((2006) ). Dangerous Enthusiasms: e-government, Computer Failure and Information System Development. Dunedin, NZ: Otago University Press. |

[32] | Grönlund, Å. ((2005) a). Electronic Government – what’s in a word? Aspects on definitions and status of the field. In Encyclopedia of Elctronic Government. |

[33] | Grönlund, Å. ((2005) b). What’s in a field – Exploring the eGoverment domain. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. |

[34] | Grönlund, Å. ((2011) ). Connecting eGovernment to real government – The failure of the UN eParticipation index. In: Vol. 6846 LNCS. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), pp. 26-37. |

[35] | Grönlund, Å., & Horan, T.A. ((2005) ). Introducing e-Gov: History, definitions, and Issues. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 15: (39), 713-729. |

[36] | Heeks, R. ((2008) ). Benchmarking e-government: Improving the national and international measurement, evaluation and comparison of e-government. In I. Z. & L. P. (Eds.), Evaluating Information Systems: Public and Private Sector, New York: Routledge, pp. 257-301. |

[37] | Heeks, R., & Bailur, S. ((2007) ). Analyzing e-government research: Perspective, philosophies, theories, methods, and practice. Government Information Quarterly, 24: (2), 243-265. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000246225800001. doi: 10.1016/. |

[38] | Hirschheim, R., & Klein, H.K. ((2012) ). A glorious and not-so-short history of the information systems field. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13: (4), 188-235. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000307845900002. |

[39] | Jansen, A. ((2005) ). Assessing e-government progress – why and what. Paper presented at the Norsk konferanse for organisasjoners bruk av informasjonsteknologi (NOKOBIT), University of Bergen. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.107.9423&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 2019-12-05). |

[40] | Janssen, D. ((2003) ). Mine’s Bigger than yours: Assessing International eGovernment Benchmarking. Paper presented at the 3rd European Conference on e-government, MCIL Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. http://steunpuntbov.be/rapport/s050601_bigger.pdf (last accessed 2019-12-05). |

[41] | Janssen, D., Rotthier, S., & Snijkers, K. ((2004) ). If you measure it they will score: An assessment of international eGovernment benchmarking. Information Polity, 9: (3-4), 121-130. |

[42] | Kromidha, E. ((2012) ). Strategic e-government development and the role of benchmarking. Government Information Quarterly, 29: (4), 573-581. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2012.04.006. |

[43] | Kunstelj, M., & Vintar, M. ((2004) ). Evaluating the progress of e-government development: A critical analysis. Information Polity, 9: (3-4), 131-148. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-34249740729&partnerID=40&md5=dc782bf1b3ccd68c316beb7b23884c1e. |

[44] | Lapsley, I. ((2009) ). New public management: The cruellest invention of the human spirit? Abacus, 45: (1), 1-21. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-61449193267&doi=10.1111%2fj.1467-6281.2009.00275.x&partnerID=40&md5=e1e19222e7efb5ef6ed68a6d40bdb4d6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6281.2009.00275.x. |

[45] | Lenk, K. ((2007) ). Reconstructing public administration theory from below. Information Polity: The International Journal of Government & Democracy in the Information Age, 12: (4), 207-212. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=afh&AN=31395317&site=ehost-live. doi: 10.3233/IP-2007-0126. |

[46] | Lenk, K. ((2012) ). The Nuts and Bolts of Administrative Action in an Information Age. In Snellen, I.T.M., Thaens, M., & van de Donk, W.B.H.J. (Eds.), Public Administration in the Information Age: Revisited, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, IOS Press, pp. 221-234. |

[47] | Lenk, K., Traunmüller, R., & Wimmer, M.A. ((2002) ). The Significance of Law and Knowledge for Electronic Government. In Grönlund, Å. (Ed.), Electronic government design, applications and management, Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing. |

[48] | Magnusson, J. ((2017) ). Accelererad digitalisering av offentlig sektor: förmågor, uppgifter och befogenheter (slutrapport 1 till regeringskansliet, juni). Retrieved from Göteborgs universitet, publication can be downloaded at http://www.digitalforvaltning.se/rapporter/ (last accessed 2018-08-20). |

[49] | Obi, T., & Iwasaki, N. ((2010) ). Electronic governance benchmarking – Waseda University e-Gov ranking. Paper presented at the ICEGOV ’10 Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance Beijing, China. |

[50] | Ojo, A., Janowski, T., & Estevez, E. ((2007) ). Determining progress towards e-government: What are the core indicators? United Nations University, International Institute for Software Technology, 1-10. |

[51] | Peters, R.M., Janssen, M., & Van Engers, T.M. ((2004) ). Measuring e-government impact: Existing practices and shortcomings. Paper presented at the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. |

[52] | Potnis, D.D., & Pardo, T.A. ((2011) ). Mapping the evolution of e-Readiness assessments. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 5: (4), 345-363. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-80053631968&doi=10.1108%2f17506161111173595&partnerID=40&md5=662c52246ad3163e01f585eefc176564. doi: 10.1108/17506161111173595. |

[53] | Rocco, S.T., & Plakhotnik, S.M. ((2009) ). Literature reviews, conceptual frameworks, and theoretical frameworks: Terms, functions, and distinctions. Human Resource Development Review, 8: (1), 120-130. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-65249142159&doi=10.1177%2f1534484309332617&partnerID=40&md5=9e04e668345a919812918310a436931d. doi: 10.1177/1534484309332617. |

[54] | Rorissa, A., Demissie, D., & Pardo, T. ((2011) ). Benchmarking e-government: A comparison of frameworks for computing e-government index and ranking. Government Information Quarterly, 28: (3), 354-362. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS: 000292180400007. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.09.006. |

[55] | Sakowicz, M. ((2004) ). How should e-government be evaluated? Different methodologies and methods. Occasional Papers in Public Administration and Policy, Published by the Network of Institutes and Schools of Public Administration in Central and Eastern Europe (NISPAcee), 5: (2), 18-26. |

[56] | Salem, F. ((2007) ). Benchmarking the e-government bulldozer: Beyond measuring the tread marks. Measuring Business Excellence, 11: (4), 9-22. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-36348985575&doi=10.1108%2f13683040710837892&partnerID=40&md5=984a10d26dd2ffeaf3c0019ddcafd650. doi: 10.1108/13683040710837892. |

[57] | Schellong, A.R.M. ((2010) ). Benchmarking EU e-government at the crossroads: A framework for e-government benchmark design and improvement. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 4: (4), 365-385. Retrieved from https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/17506161011081336. doi: 10.1108/17506161011081336. |

[58] | Schlæger, J. ((2016) ). An empirical study of the role of e-government benchmarking in China. Information Polity, 21: (4), 383-397. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85008693375&doi=10.3233%2fIP-160399&partnerID=40&md5=099ac32bec887c9607cb36165589fdb9. doi: 10.3233/IP-160399. |

[59] | Snijkers, K., Rotthier, S., & Janssen, D. ((2007) ). Critical review of e-government benchmarking studies. In Griffin, E.A.D. (Ed.), Developments in e-government: A Critical Analysis, IOS Press, pp. 73-85. |

[60] | Taylor, J.A. ((2004) ). Editorial. Information Polity: The International Journal of Government & Democracy in the Information Age, 9: (3/4), 119-120. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=afh&AN=17109069&site=ehost-live. |

[61] | Torraco, R.J. ((2005) ). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4: (3), 356-367. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84992782655&doi=10.1177%2f1534484305278283&partnerID=40&md5=ad3c13a212a1db9b46a4e351cad198d5. doi: 10.1177/1534484305278283. |

[62] | Webster, J., & Watson, R.T. ((2002) ). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26: (2), XIII-XXIII. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000176079000002. |

[63] | Wendler, R. ((2012) ). The maturity of maturity model research: A systematic mapping study. Information and Software Technology, 54: (12), 1317-1339. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84865720227&doi=10.1016%2fj.infsof.2012.07.007&partnerID=40&md5=d01f0ef0339272100c6eaeacd452dc5b. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2012.07.007. |

[64] | West, D.M. ((2005) ). Digital Government Technology and Public Seector Performance. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. |

[65] | Whitmore, A. ((2012) ). A statistical analysis of the construction of the united nations e-government development index. Government Information Quarterly, 29: (1), 68-75. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000298213000008. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2011.06.003. |