Business Process Management Systems: Evolution and Development Trends

Abstract

One of the results of the evolution of business process management (BPM) is the development of information technology (IT), methodologies and software tools to manage all types of processes – from traditional, structured processes to unstructured processes, for which it is not possible to define a detailed flow as a sequence of tasks to be performed before implementation. The purpose of the article is to present the evolution of intelligent BPM systems (iBPMS) and dynamic case management/adaptive case management systems (DCMS/ACMS) and show that they converge into one class of systems, additionally absorbing new emerging technologies such as process mining, robotic process automation (RPA), or machine learning/artificial intelligence (ML/AI). The content of research reports on iBPMS and DCMS systems by Gartner and Forrester consulting companies from the last 10 years was analysed. The nature of this study is descriptive and based solely on information from secondary data sources. It is an argumentative paper, and the study serves as the arguments that relate to the main research questions. The research results reveal that under business pressure, the evolution of both classes of systems (iBPMS and DCMS/ACMS) tends to cover the functionality of the same area of requirements by enabling the support of processes of different nature. This de facto means the creation of one class of systems, although for marketing reasons, some vendors will still offer separate products for some time to come. The article shows that the main driver of unified software system development is not the new possibilities offered by IT, but the requirements imposed on BPM by the increasingly stronger impact of knowledge management (KM) with regard to the way business processes are executed. Hence the anticipation of the further evolution of methodologies and BPM supporting systems towards integration with KM and elements of knowledge management systems (KMS). This article presents an original view on the features and development trends of software systems supporting BPM as a consequence of knowledge economy (KE) requirements in accordance with the concept of dynamic BPM.

1Introduction

Business Process Management (BPM) is at present one of the most often implemented methods of management within organizations (Hammer, 2015; Dumas et al., 2016), though it is not a new concept in and of itself. Its foundations have been set as far back as 100 years ago by Taylor (Deming, 1986). Traditional BPM assumes that employees designing business processes (BPs) have complete knowledge of their course, including all factors affecting the process and all decisions that need to be taken. As a result, they are able to prepare an optimal process flow model consisting of a sequence of actions to be executed. However, not all processes are so fully predictable. In accordance with the works of van der Aalst et al. (2005), Sandy Kemsley (2011), or DiCiccio et al. (2015), depending on the dynamism of their execution, business processes can be divided into:

• structured (static) processes – traditionally understood BPs,

• structured processes with ad hoc exceptions11 – BPs for which there may be exceptions to flow in places specified prior to execution,

• unstructured processes with pre-defined fragments – BPs for which flow can be strictly determined only for fragments prior to execution,

• unstructured processes – processes for which it is not possible to define the flow, prior to execution.

Changes in the economy meant that traditional BPM can be used only for about 30% of processes in organizations operating in the knowledge economy (KE) (Ukelson, 2010; Olding and Rozwell, 2015). In the remaining approximately 70% of processes, processes cannot be reduced to the routine repetition of a previously defined standard process (vom Brocke et al., 2015). However, there is still no generally accepted theoretical reflection of the fact that most of the organization’s processes in the KE fall outside the scope of traditional business process management (Klun and Trkman, 2018; Zelt et al., 2018). Under the pressure of business, many concepts have been created in the last 15 years and, above all, practical methodologies and software tools to manage organizations whose operation, results, and competitive position depend more on the flexibility and intensity of knowledge use than on the perfect repetition of top-designed processes. They arose and evolved in two ways: as an extension of earlier solutions derived from traditional BPM or as new concepts based on the case-handling paradigm (van der Aalst et al., 2005; Gartner, 2012). The aim of the article is to present this evolution and the current state of the methodologies and software tools resulting from it, as well as to answer the following two main research questions:

• RQ1: Does the development of iBPM and ACM/DCM systems, regardless of the starting point, aim to support all types of organization processes in the KE?

• RQ2: Does the evolution of iBPM and ACM/DCM systems de facto lead to their unification?

In the Discussion section, the article responds affirmatively to RQ2 and puts forward the thesis about the rationality of the unification of both classes of systems. At the same time, it emphasizes the need to pay more attention to BPM (including supporting software) implementation methodologies, which should be tailored to the nature of the processes and the process maturity of the organization, rather than to the capabilities of existing or implemented systems. It confirms the thesis presented in the Discussion on the use of iBPM and DCM/ACM systems through the lens of describing both structured and non-structured processes. It also indicates the need to extend BPM supporting systems with elements of knowledge management (KM), which resulted from theoretical reflection within the concept of dynamic BPM, but also from the growing importance of practical machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques.

Structurally, this article is organized as follows: Section 2 shows the background of the situation based on the available literature, Section 3 presents research of the evolution of iBPM and DCM systems based on Gartner and Forrester reports from the last 10 years, Section 4 discusses the concept of unification of the systems supporting BPM. Finally in Section 5, the authors conclude with a summary of the findings, limitations of the study, and some directions of the future research.

2Background

BPM as a discipline was and is developing in response to constantly emerging business expectations and the possibilities offered by available technologies. As part of the first wave of process management initiated by Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management (1911), it covered only production processes. At present, it is used in all areas of organization management and within the interaction between the organization and its environment. The objective of BPM have also changed. Initially, it was to ensure the development and implementation of an optimal, standard fully repeatable way of carrying out work. Then, this goal was supplemented by ensuring the continuous improvement of processes. Another added extension was the continuous adaptation of processes to changing customer requirements and rules of competition (Armistead et al., 1999, 96–106; Smith and Fingar, 2002). Defining the basic dimensions of the business process in the knowledge economy as:

• Unpredictability: “the degree to which a process can be implemented based on the codified knowledge existing before process execution” and

• Knowledge-intensity: “the degree in which process results depend on the use in execution of the process of tacit knowledge, the creation of new knowledge, and the rejection of old, outdated knowledge”,

In the KE, business processes should be managed in a dynamic manner and increasingly based on an individual, a team, and organizational knowledge to become increasingly more flexible, and well as adjusted to the changing context of execution based on the knowledge and commitment of their executors (van der Aalst et al., 2005; Richter-von Hagen et al., 2005; Ariouat et al., 2016). This requires enabling executors to shape the course of processes in a manner adapted to the context of execution.

In the context of enterprise system development, business processes, information systems, and software systems should be tightly integrated (Caplinskas et al., 2002). Requirements are mapped from business level to lower level systems, and lower level systems are constrained by rules governing processes in higher level systems. Alignment of these systems cannot be achieved without linking IT systems requirements with business vision, goals and strategies (Caplinskas, 2009; Kirchmayr et al., 2006). Therefore, practitioners have anticipated the challenge through methodologies and development of IT systems supporting business processes:

• extending traditional BPM software systems in a way that enables their dynamic management, defined i.a. as: agile, dynamic, contingent, human, intelligent, etc. (Zelt et al., 2018; Szelągowski, 2019; Mendling et al., 2020);

• based on the paradigm of (adaptive, advanced, dynamic, etc.) case management, focusing not on the design and implementation of the process flow, but on supporting the implementation of its goals taking into account known possibilities and limitations (Pucher, 2012).

Until 2010, the Gartner company prepared a recognized market benchmark, reports on the class of systems supporting BPM, referred to as Business Process Management Suites (BPMS). Recognizing the breakthrough nature of the changes, Gartner published the first Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites Report (Gartner, 2012) on March 12, 2012, which clearly highlighted the emergence of a new class of systems other than traditional BPM Suites and recommended not comparing them with previous reports. Three years later, on March 12, 2015, Gartner published the Magic Quadrant for BPM-Platform-Based Case Management Frameworks report (Gartner, 2015a), and 6 days later, another report titled Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites (Gartner, 2015b), which was largely based on the products of the same vendors – as if Gartner could not decide how to assess the changes taking place in the market and just in case described them from two different points of view: traditional BPM extensions and case management. Similarly, in 2016, The Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites was published on August 18 (Gartner, 2016a). The report The Magic Quadrant for BPM-Platform-Based Case Management Frameworks was published 2 months later (Gartner, 2016b). In 2017 and 2019, Gartner published two more reports (Gartner, 2017, 2019a) devoted only to iBPMS, abandoning the practice of publishing separate reports devoted to BPM-Platform-Based Case Management Frameworks, while adding the possibility of case management as one of the necessary requirements for iBPMS systems.

Simultaneously, Forrester published reports on BPMS in 2010, and 2013 (Forrester, 2010, 2013). In 2011, and then in 2014, 2016, and 2018, Forrester published reports on Dynamic Case Management Systems (Forrester, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2018).

In addition, other researchers recognize and analyse rapid changes undergoing in similar fields of operation (e.g. document management systems (DMS) and workflow systems) (Antunes and Mourao, 2010; Bider and Prejons, 2014). This multitude of analyses, as well as clear fluctuations in the way in which changes are assessed, even by recognized research and consulting companies, shows how intensively the practical applications of BPM are evolving. Therefore, both theoretical reflection, as well as the independent practical assessment of numerous business experiences are needed, along with a summary of the current development of BPM/iBPM and DCM/ACM systems (Trkman, 2009; Pucher, 2012, 60).

3Research of the Evolution of iBPM and DCM Systems

3.1Intelligent Business Process Management Systems – Gartner Reports

In 2012, Gartner published the first report on a new class of iBPM systems. Without changing the evaluation criteria adopted in previous reports, the definition and the requirements for systems supporting process management have changed significantly. The initial definition – “BPMSs are the leading integrated composition environment (ICE) to support BPM and enable continuous improvement. … A BPMS is an integrated collection of software technologies that enables process transparency, and, thus, better management of the business process, as well as work in the process.” (Gartner, 2010, p. 5) – has subsequently changed with each report, and with it the main features of intelligent Business Process Management Systems (iBPMS) solutions changed (Table 1).

Table 1

Evolution of iBPMS definitions (authors’ own elaboration, based on Gartner reports).

| Source | BPMS/iBPMS definition |

| Gartner (2010) | (Traditional) BPMSs are the leading integrated composition environment (ICE) to support BPM and enable continuous improvement. |

| Gartner (2012) | An iBPMS expands the traditional BPMS by adding the new functionality needed to support intelligent business operations (IBO) such as:

|

| Gartner (2015a; 2015b) | iBPMSs have added enhanced support for human collaboration, integration with social media, mobile access to processes, more analytics and real-time decision management. … This coordinates the interactions of all types of actors (people, devices and computer systems) for structured and unstructured flows, and also supports case management and dynamic processes. |

| Gartner (2017) | Gartner defines an iBPMS as an integrated set of technologies that coordinate people, machines and things. It emphasizes: |

| |

| Gartner (2019a; 2019b) | An iBPMS is a type of high-productivity (low-code/no-code) application development platform. An iBPMS enables dynamic changes in operating models and procedures, documented as models (process flows, business rules, decision models, data models, and others), directly driving the execution of business operations. In turn, business users make frequent (or ad hoc) process changes to their operations independently of IT-managed technical assets. |

| Gartner Glossary (2020) | A BPMS supports the entire process improvement life cycle – from process discovery, definition and design to implementation, monitoring and analysis, and through ongoing optimization. Its model-driven approach enables business and IT professionals to work together more collaboratively throughout the life cycle. |

Of note is the departure from the CPI, derived from the organizational Deming Cycle, extending the learning loop of the organization beyond the duration of BPs. On the other hand, support for real-time human collaboration and the ability to directly drive the execution of business operations are becoming increasingly important. This change is also clearly visible in the core components or capabilities (essential elements) that change in subsequent iBPMS reports (Table 2).

Table 2

Core capabilities of iBPMS (authors’ own elaboration, based on Gartner reports).

| No. | iBPMS core capabilities | 2010 (BPMS) | 2012 | 2015 | 2019 |

| 1 | Real-time business analytics | x | x | x | x |

| 2 | Content interaction management | x | x | x | x |

| 3 | Human interaction management | x | x | x | x |

| 4 | Business rule management | x | x | x | x |

| 5 | Social media to support social behaviour and collaboration | x | x | x | |

| 6 | Support for structured and unstructured flows | x | x | x | |

| 7 | Supports case management and dynamic processes | x | x | x | |

| 8 | Expanded technologies to support growing requirements for mobility, cloud, interoperationability, etc. | x | x | x | |

| 9 | Real-time decision management | x | x | ||

| 10 | Directly driving the execution of business operations | x | |||

| 11 | High-productivity (low-code/no-code) application development | x | |||

| 12 | New technologies (e.g. process mining, mobility) | x |

Indeed, a radical change occurs along with the first report dedicated to iBPMS. Based on organizational teamwork, but located outside of process execution, the criteria CPI and Implementation of an industry-specific or company-specific process solution (Gartner, 2010, p. 2) are replaced in 2012 by capabilities that directly support process executors, such as Content interaction management, Human interaction management, or Real-time/On-demand analytics. Completely new options appear, such as social media supporting social behaviour and collaboration or case management and dynamic processes. Subsequent years witness the appearance or the foregrounding of core capabilities strengthening the possibility of using iBPMS for dynamic real-time management (real-time decision management or directly driving the execution of business operations). At the same time, of increasing importance to Gartner’s assessment of the products of individual vendors is integration with iBPMS of technologies that can support:

• acquiring knowledge about performed or completed processes (process mining, real-time analytics, predictive analytics, ML/AI),

• process automation (RPA, ML/AI, IoT, Blockchain).

In the face of constant change, iBPMS systems must enable organizations to focus on gaining or maintaining competitive advantage, which is derived from not only efficiency and flexibility, but also from having the intelligence to perceive and interpret signals coming during the execution of processes and the ability to make decisions, as well as the capability to proactively move in the direction expected by the market or even an individual customer (Palmer, 2013). This is perfectly illustrated by the changes to the Use Case Evaluation section of subsequent reports from 2015 (Table 3).

Table 3

Use cases illustrating the typical uses of iBPMS (authors’ own elaboration, based on Gartner reports).

| 2015 | 2017 | 2019 |

| Composition of intelligent, process-centric applications | Composition of intelligent, process-centric applications | Digital Business Optimization (Digital business technologies and approaches can be used to improve the enterprise without changing its business.) |

| Continuous process improvement | Continuous process improvement | |

| Business transformation | Business transformation | Digital Business Transformation (In contrast to digital business optimization, there are digital business initiatives that result in net new revenue streams, products/services and even new business units with a new business model.) |

| Digitalized process | Digitalized process | |

| Citizen developer application composition | Self-Service Intelligent Business Process Automation (By offering a high-productivity development experience, an iBPMS enables self-service development of process-centric applications for line-of-business and professional citizen developers.) | |

| Case management | Adaptive Case Management (iBPMSs support case management in their ability to execute unstructured or semistructured processes.) |

Requirements which were dispersed in 2015 and 2017 in various specific categories were generalized in 2019 to enable supporting both streamlining the organization without changing the business model (Optimization), as well as broadly understood business transformation (Transformation). At the same time, requirements have been added to allow for the management of unstructured processes, including empowering business users (citizen developers understood as non-IT users) to make business changes. Since 2017, iBPMS have to support case management – the ability to execute unstructured or semi-structured processes, which in 2019 was further specified as support for Adaptive Case Management.

3.2Dynamic Case Management Systems – Forrester Reports

In the report published by Forrester at the end of 2009, “DCM – an old idea catches new fire” (Forrester, 2009), the authors point out two main reasons for the growing interest in case management:

• Resulting from increased competition and changes in the nature of BPs, an increased need for cost and risk management while ensuring compliance with applicable regulations, including unstructured processes;

• Resulting from the pressure from government agencies and individual users to increase the use of remote collaboration and social media to support the execution of unstructured business processes, which itself is the result of increasing digitization.

Although the title of the mentioned report suggests that the idea is not new, this does not mean only minor changes. On the contrary, the new way of thinking about supporting complex activities should be perceived (Le Clair et al., 2011). The first Forrester report dedicated to Dynamic Case Management Systems (DCMS) review (Forrester, 2011) indicates 3 key capabilities of this class of systems for businesses operating in the KE:

• provides information in context;

• enables more runtime and design time changes;

• allows case workers to select predefined case steps.

This defines the main area of DCMS usage as: “Dynamic case management platforms align well with untamed processes because they support unstructured and structured content combining human- and system-controlled processes and facilitating knowledge and expert guidance” (Forrester, 2011). As part of subsequent reports, the requirements for expected DCMS capabilities were specified by Forrester in the direction of improving the maturity of case management capabilities, covering (re)use objects and process fragments in the form of templates and generic case patterns, flexibility of use, paying attention to the user interface (UI) and diversity of communication channels, as well as organizational learning through capturing knowledge from executed cases/tasks (Table 4).22

Table 4

Core capabilities of DCMS in Forrester’s reports (authors’ own elaboration, based on Forrester reports).

| No. | DCMS core capabilities | 2011 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 |

| 1 | Variation handling and reuse of predefined entities (process fragments, case patterns, templates for artefacts, etc.) | x | x | x | x |

| 2 | Changes during design time and runtime by case workers and managers, choise of predefined case steps by workers | x | x | x | x |

| 3 | Predictive analytics | x | x | x | x |

| 4 | Defining ad hoc cases/tasks during runtime | x | x | ||

| 5 | Integration and delivering of structured and unstructured content in context in accordance with the course of the case | x | x | x | |

| 6 | Visibility, control and traceability of case steps (tasks) | x | x | ||

| 7 | Visibility and control also as part of off-process activities such as e.g. email, and phone calls | x | x | ||

| 8 | Support of an increasing volume of knowledge work | x | |||

| 9 | A strong goal orientation (goal management) | x | |||

| 10 | Social technologies | x | x | x | |

| 11 | Combination process-based design with information modelling, multiple types of supporting documents | x | x | ||

| 12 | Rules-based processing, including rules complexity management | x | x | ||

| 13 | Flexible UI development environments, UI diversity | x | x | ||

| 14 | New technologies – cloud deployments, cloud platforms | x | x | ||

| 15 | Digital process automation, including low-code software support | x |

The characteristics of DCM and their trends over the period considered are as follows:

• Vendors started with basic DCM features like pre-defined means to handle variations (e.g. process fragments, context specific business rules), collaboration in real time, goal management, covering work within case process boundaries, and developed their solutions to allow for extremely good reusability and solution accelerators, matured analytics, and to support increasingly complex use cases.

• The use and variety of data has been broadened. The early versions of the systems were integrated with the underlying data, while the later versions combined information modelling with traditional process-based design mapping (Forrester, 2016). Data from multiple various repositories, including DCM and non-DCM repositories, can be accessed and visualized in today’s systems.

• The use of context-specific business rules has been developed in the form of business rules management, which includes English expression editors for rules (Forrester, 2016).

• The shift has been made from context understanding towards taking into account the changing context of each state and context-based decision making.

• The use case categories remain the same: investigative, incident management, and service requests. However, specific case management technologies have been added, for example, real-time interaction, social technologies, and ML/AI.

• Digital process automation (DPA) has formally established its position. DPA have traditional BPM, DCM, and low code software as their parts (Forrester, 2019). Supported automation has been broadened by including decision automation and robotic process automation (RPA).

• Vendors have improved user interface development environments. Interaction with the systems has become possible through the broad diversity of communication channels, in real time and with mobile users.

• There has been a shift of case solutions to the cloud, including domain-specific cloud platforms, which are more affordable and flexible than traditional systems.

It should be noted that some DCMS vendors have integrated into their systems traditional, repetitive process management because, as a rule, it is very rare in today’s business to have purely one type of processes. The use of knowledge (in the form of business rules, context-aware decisions, etc.) is an inherent feature of DCM systems because of their nature. As early as in 2011, Forester wrote that DCM systems facilitate knowledge and expert guidance (Forrester, 2011). However, as the analysis shows, KM should be developed to a more mature level to enable complete KM support in those systems.

4Discussion

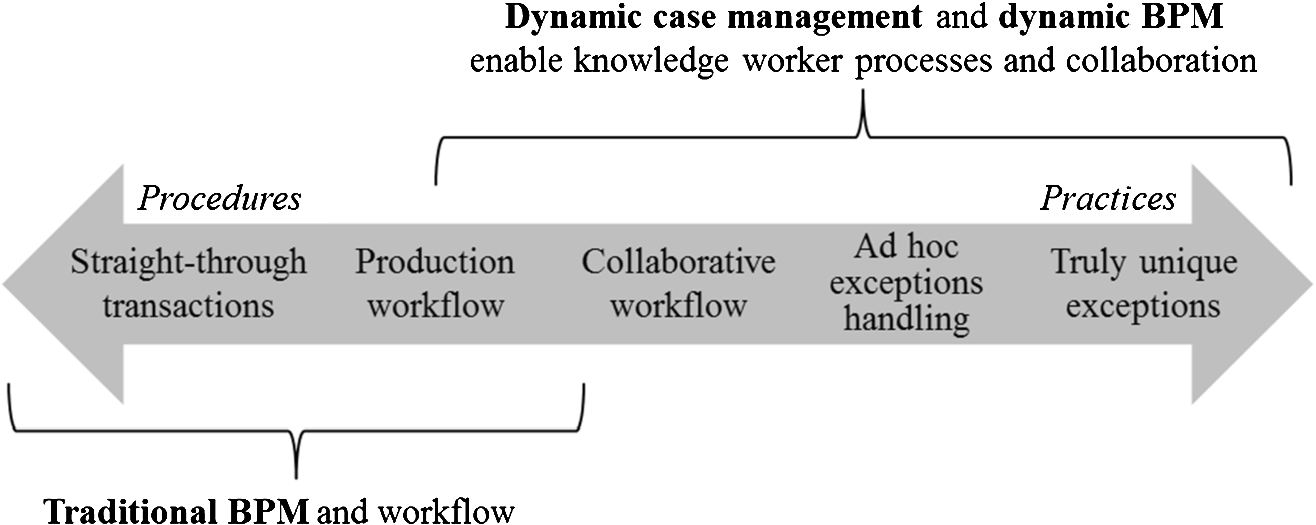

As early as in Forrester’s reports from 2009 and 2010 (Forrester, 2009, 11–13; Forrester, 2010, 18), the authors indicated that DCM is a process tool, albeit one which uses elements of the human-centric or integration-centric approach to a much broader extent than traditional BPMS. The Forrester Wave: BPM Suites report from 2013 (Forrester, 2013, p. 3) also includes DCM as process tools/technologies, indicating unstructured processes and collaborative workflow as its area of application (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

The scope of IT systems support for processes of various nature (authors’ own elaboration, based on Forrester reports (2013, p. 3)).

It also presents the general direction of the evolution of BPM support software systems, which aims to support all types of processes by one class of systems, defining as one of the criteria for assessing BPMS systems: “Support for DCM, human workflow, and straight-through processing” (Forrester, 2013, p. 10). Furthermore, the authors of the report dedicated to DCMS prepared five years later (Forrester, 2018, p. 7) define the tested solutions as “a BPM platform,” although a paragraph later the condition for including the vendor in the report is stated as “a case management solution framework that is distinguishable from the underlying BPM platform.”

It seems that Gartner analysts are more consistent, as with each report they expand and refine the scope of expected capabilities of iBPMS systems to support non-traditional (non-structured) BPM. General terms about “more machine and human intelligence” (Gartner, 2012) have been clarified as an opportunity of “frequent (or ad hoc) process changes to their operations independently of IT-managed technical assets.” (Gartner, 2019a). At the same time, the reports from 2017 and 2019 directly stated the requirement for iBPMS systems to support case management, and in the report from 2019 they were clarified as supporting Adaptive Case Management (Gartner, 2019a, p. 42). According to Max Pucher, one of the main influencers of the ACM concept: “Forrester defines dynamic case management to be semi-structured and collaborative, dynamic, human-centered, information-intensive processes undertaken around a given context, while being driven by events, requiring incremental and progressive responses. So what is different about ADAPTIVE Case Management? The key point is not just runtime dynamic changes, but Just-In-Time creation of the process and resources WITH embedded learning, which means that knowledge of a previous case can be automatically used by people in a later case or process! … I see ACM mostly for knowledge workers who apply their specific skill for case resolution or process execution.” (Pucher, 2010a; 2010b). In the operation of iBPMS, the Gartner report of 2019 clearly distinguishes:

• the macrolevel: organizational design and process monitoring, organizational CPI, and business transformation, and

• the microlevel: support for knowledge workers by using real-time analytics, decision automation, and decision support, the goal of which is to an iBPMS drive improvements in the execution of a particular process or case (Gartner, 2019a).

Therefore, in its assessment of iBPMS systems, Gartner includes support for predictable processes optimized on the basis of explicit knowledge held by the organization in the design phase, as well as unpredictable, unstructured BPs, for which the achievement of assumed goals requires knowledge workers to use tacit knowledge in a manner fully adapted to the context of execution. Max Pucher makes this even clearer: “Complex knowledge work is unpredictable as are the majority of processes, … I am not against process management. I oppose the concept that human business interactions are improved by flowcharting them or that human knowledge can be encoded. So I am all for a new kind of BPM that is adaptive and empowers business people” (Pucher, 2010b). Therefore, the direction of development is not determined by information technologies (although e.g. ISIS Papyrus has already had elements of artificial intelligence in the ACMS system), but the requirements imposed on BPM by the increasingly stronger influence of KM on the method of implementation and the results of business processes. This is a clear signal of the further evolution of methodologies and BPM supporting systems towards their integration with Knowledge Management and in the area of systems supporting management with elements of knowledge management systems (KMS).

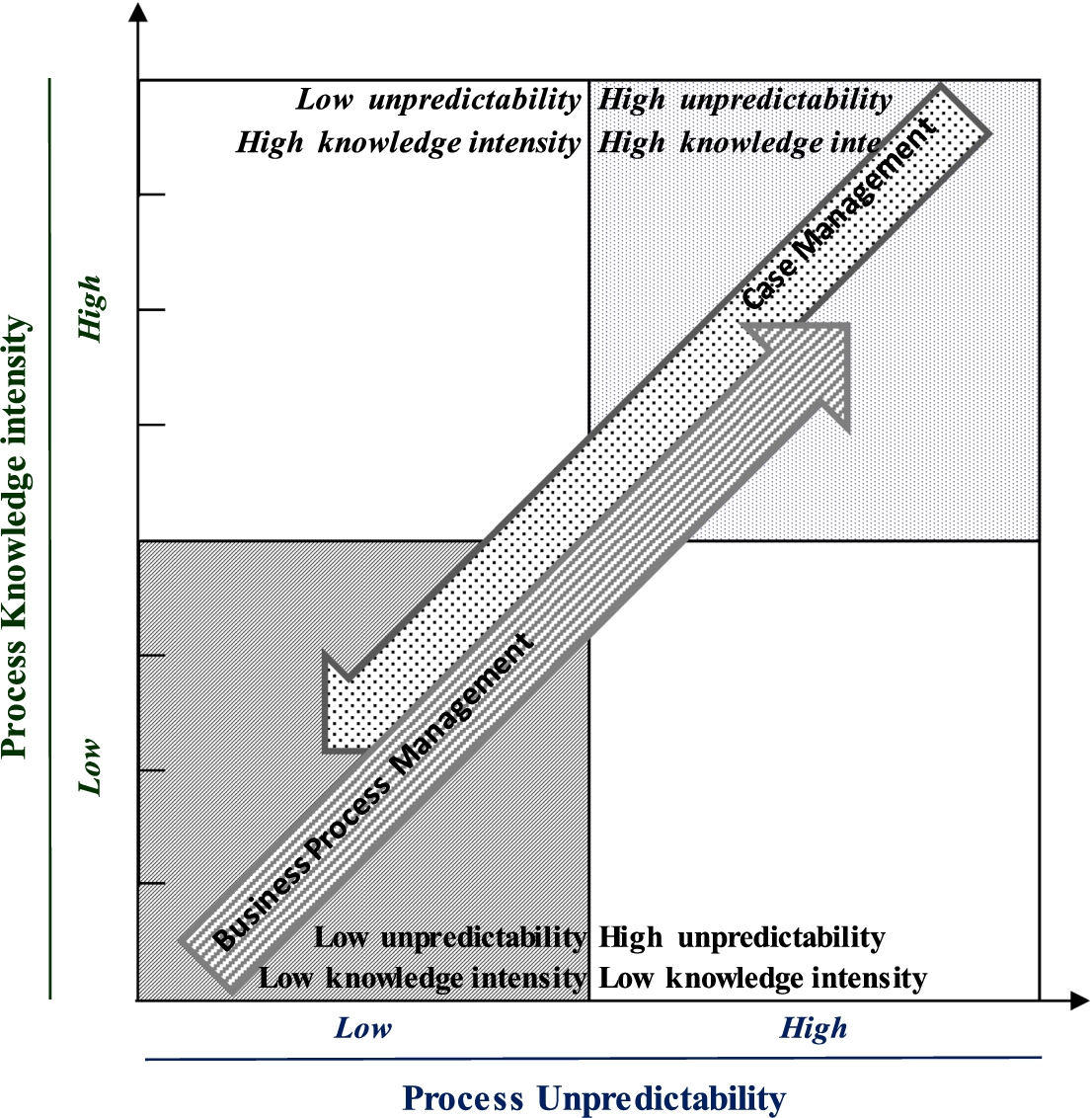

The evolution of BPM support software systems began with two opposing assumptions:

• case management systems – support for processes with an unpredictable flow and a not entirely known, but potentially high intensity of knowledge;

• traditional BPMS – support for processes of known and strictly repeated nature thanks to having all the knowledge necessary to perform the processes before executing.

It strives to support all process groups, irrespective of their nature: unpredictability and knowledge intensity. This can be clearly understood by the presentation of the directions of the evolution of both classes of systems in a space consisting of two dimensions: Unpredictability (X-axis) and Knowledge Intensity (Y-axis) (Fig. 2) (Szelągowski and Berniak-Woźny, 2020).

Fig. 2

The evolution of BPM support systems – penetration of the functionality of iBPM and DCM/ACM systems (authors’ own elaboration, based on Szelągowski and Berniak-Woźny, 2020).

Under the pressure of business, DCMS vendors have expanded their systems with the ability to describe and execute traditional, repetitive processes that do not require the use of tacit knowledge of employees executing the process (e.g. Appian, ISIS Papyrus). At the same time, vendors of iBPMS systems expanding support for traditional processes with new technologies to automate their execution or analytical capabilities, simultaneously have expanded their systems with support for semi-structured and unpredictable processes in accordance with ACM (e.g. Appian, Creatio). This results in a positive answer to the first research question RQ1: the development of iBPM and ACM/DCM systems, regardless of the starting point, aims to support all types of processes in organizations in the KE.

All iBPMS systems included in the Gartner report for 2019 meet the requirements, which, according to the Forrester report of 2011, determined the emergence of a class of DCMS systems (Forrester, 2011, p. 2). This de facto means the close functional unification of iBPMS and DCMS/CMS systems. Software vendors are already using the same solutions, technologies, etc. in both classes of systems (Moore, 2017). An example would be Pegasystems, whose offer already includes one BPM & Case Management systems (Pegasystems, 2020) and IBM in IBM Automation Platform for Digital Business merged IBM iBPMS and IBM Case Manager (IBM, 2020). This unification is also expected at business level, because the costs of purchasing, implementing, and maintaining two systems are always greater than in the case of one, not to mention the problems with their integration, ontological differences, data consistency, etc. So, the analysis performed enables conclusion that the answer to the second research question RQ2 is also positive: the evolution of iBPM and ACM/DCM systems de facto leads to their unification. Its effect will be (in the case of Pegasystems and IBM it is already) a significant simplification of the architecture of systems supporting the implementation of business processes. Of course, this does not mean the unification of implementation and process improvement methodologies, which very strongly depend on the nature of the processes and the process maturity of the organization. It is necessary to supplement them with the possibility of assessing the nature of each process group to implement solutions compatible with the nature of supported processes as part of the BPM supporting system implementation.

5Conclusions

The analysis of the main capabilities of iBPMS and DCMS showed a trend towards a constantly increasing number of overlapping features. At the end of the considered period, both classes of systems enable dynamic execution of processes, adaptation to the operational context; integration rules processing; access to different sources of data to derive informed decisions in real time; and support of process redesign that emphasizes automation and digitization. As shown in product reviews of rating leaders for both system classes, full unification now depends more on the strength of business pressure or marketing decisions than on the scope of functionalities or technological capabilities. The analysis of Gartner and Forrester reports show that in practice, software vendors and the systems that would not allow the use of process and case approaches for processes of different nature, lose the market and are no longer relevant. This is definitely an alarm bell for vendors who have delayed the development of their systems and motivation for those who have already included in their development plans the extension of the scope of supported processes. The vendor systems included in the reports of both companies cover the functionality of supporting all types of BPs, combining BPM-specific features such as process modelling with typical case management features such as the ability to freely choose or create tasks (Appian, 2018; Pegasystems, 2020).

The analysis also shows that the direction of system development, which is parallel to the expanding the scope of processes covered by support, is the increasing use of new, emerging technologies (Gartner, 2019b). Some of them, such as mobility, cloud computing, or predictive analytics, have already been included in the “compulsory” category by the authors of the reports. In the case of the next ones, such as process mining, social collaboration, RPA, Blockchain, IoT, or ML/AI, business pressure, changes in social culture, and the growing maturity of technologies themselves will allow for their rapid dissemination in the coming years or maybe months. The subject of future work will be an in-depth analysis of the pace and scope of changes taking place, taking into account the readiness of business to implement them in everyday operations.

The limitation of the research presented in the article is the use of materials only from two consulting companies. The study does not include data from other sources, e.g. other consulting companies, industry organizations, or vendor experience and development plans. Independent research into the practical use of emerging new technologies or BPM implementation methodologies is also not included. Analysing the evolution of process IT systems only, this article does not show the parallel development of ERP/postmodern ERP systems or the importance of issues related to the integration of process systems and ERP systems (Guay, 2016; Gartner, 2019c).

When analysing the directions of future development, attention should be paid to Gartner’s specification of the compliance of systems with ACM. This is the first step in the development of iBPMS towards full KM support. This would allow iBPMS to support all types of processes regardless of the requirements as to unpredictability, but also knowledge intensity. This is the direction expected by researchers (Marjanovic and Freeze, 2012; Szelągowski, 2014) and at the same time imposed by the development of ML/AI technology and methodologies (Pucher et al., 2014). This will enable organizations to effectively implement KM in their daily operations aimed at acquiring knowledge from their executed BPs, which will significantly affect the competitiveness and speed of their development in the KE. This shows that the main driver of systems evolution is not information technology, but the requirements imposed on business process management by the increasingly stronger impact of knowledge management (KM) in relation to how business processes are performed. Traditional BPM will go down in history, replaced by the more natural dynamic BPM, not by the power of theoreticians’ decisions, but because the latter is much more efficient at supporting the dynamism of people and teams executing processes and learning from everyday successes and failures.

Notes

1 Processes structured with ad hoc exceptions and unstructured with pre-defined fragments, are often referred to as semi-structured processes.

2 None of the Forrester reports includes a detailed list of DCMS systems evaluation criteria. The fact that the criteria have changed significantly is evidenced only by the number of declared evaluation criteria (from 57 in 2011, through 38/2014, 21/2016, to 32/2018) and a change in each of the report’s edition of the list of “aggregate” criteria according to which he ratings of individual vendors were presented. Even if the “aggregate” criterion appeared in several reports, its weight changed significantly (e.g. architecture criterion is missing in the report from 2011, and in subsequent reports it is 15%/2014, 30%/2016, and 20%/2018, respectively).

References

1 | Antunes, P., Mourao, H. (2010). Resilient business process management: framework and services. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2010.05.017. |

2 | Ariouat, H., Andonoff, E., Hanachi, C. ((2016) ) In: Do Process-based Systems Support Emergent, Collaborative and Flexible Processes? Comparative Analysis of Current Systems, Procedia Computer Science: Vol. 96: . pp. 511–520. |

3 | Armistead, C., Pritchard, J., Machin, S. ((1999) ). Strategic business process management for organisational effectiveness. Long Range Planning, 1: (32), 96–106. |

4 | Appian (2018). Dynamic Case Management. Retrieved from https://www.appian.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ap_dynamic_case_mgmt_whitepaper_web.pdf [15.04.2020]. |

5 | Bider, I., Prejons, E. ((2014) ). Design science in action: developing a modeling technique for eliciting requirements on business process management (BPM) tools. Software and Systems Modeling, 14: , 1159–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10270-014-0412-6. |

6 | Caplinskas, A., Lupeikiene, A., Vasilecas, O. ((2002) ). Shared conceptualisation of business systems, information systems and supporting software. In: Haav, H.-M., Kalja, A. (Eds.), Databases and Information Systems II. Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 109–121. |

7 | Caplinskas, A. ((2009) ). Requirements elicitation in the context of enterprise engineering: a vision driven approach. Informatica, 20: (3), 343–368. |

8 | Deming, W.E. ((1986) ). Out of the Crisis. Cambridge. MIT, Center for Advanced Engineering Study. |

9 | DiCiccio, C., Marrella, A., Russo, A. ((2015) ). Knowledge-intensive processes characteristics, requirements and analysis of contemporary approaches. Journal on Data Semantics, 4: (1), 29–57. |

10 | Dumas, M., Rosa, M.L., Mendling, J., Reijers, H.A. ((2016) ). Fundamentals of Business Process Management. Springer, Heidelberg. |

11 | Forrester ((2009) ). Dynamic Case Management – An Old Idea Catches New Fire. Published: 28 December 2009. |

12 | Forrester ((2010) ). The Forrester Wave™: Business Process Management Suites, Q3 2010. Published. Published: 26 August 2010. |

13 | Forrester ((2011) ). The Forrester Wave: Dynamic Case Management, Q1 2011. Published: 31 January 2011. |

14 | Forrester ((2013) ). The Forrester Wave: Business Process Management Suites, Q1 2013. Published: 11 March 2013. |

15 | Forrester ((2014) ). The Forrester Wave: Dynamic Case Management, Q1 2014. Published: 28 March 2014. |

16 | Forrester ((2016) ). The Forrester Wave: Dynamic Case Management, Q1 2016. Published: 2 Feb 2016. |

17 | Forrester ((2018) ). The Forrester Wave: Cloud-Based Dynamic Case Management, Q1 2018. Published: 8 March 2018. |

18 | Forrester ((2019) ). The Forrester Wave: Digital Process Automation For Wide Deployments, Q1 2019. Published: 12 March 2019; updated 25 March 2019. |

19 | Gartner (2010). Magic Quadrant for Business Process Management Suites. ID: G00205212. Published: 18 October 2010. |

20 | Gartner (2012). Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites. ID: G00224913. Published: 27 September 2012. |

21 | Gartner (2015a). Magic Quadrant for BPM-Platform-Based Case Management Frameworks. ID: G00262751. Published: 12 March 2015. |

22 | Gartner (2015b). Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites. ID: G00258612. Published: 18 March 2015. |

23 | Gartner (2016a). Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites. ID: G00276892. Published: 18 August 2016. |

24 | Gartner (2016b). Magic Quadrant for BPM-Platform-Based Case Management Frameworks. ID: G00276724. Published: 24 Oct 2016. |

25 | Gartner (2017). Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites. ID: G00315642. Published: 24 Oct 2017. |

26 | Gartner (2019a). Magic Quadrant for Intelligent Business Process Management Suites. ID: G00345694. Published: 30 January 2019. |

27 | Gartner ((2019) b). Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends for 2020 ID: G00432920. Published: 21 October 2019. |

28 | Gartner ((2019) c). Strategic Roadmap for Postmodern ERP. Published. ID: G00384628. Published: 31 May 2019. |

29 | Gartner Glossary (2020). Business Process Management Suites (BPMSs). Retrieved from https://www.gartner.com/en/information-technology/glossary/bpms-business-process-management-suite [24.02.2020]. |

30 | Guay, M. (2016). Postmodern ERP Strategies and Considerations for Midmarket IT Leaders. Retrieved from http://proyectos.andi.com.co/camarabpo/Webinar%202016/Postmodern%20ERP%20strategies%20and%20considerations%20for%20midmarket%20IT%20leaders-%20Gartner.pdf [23.08.2020]. |

31 | Hammer, M. ((2015) ). What is business process management? In: vom Brocke, J., Rosemann, M. (Eds.), Handbook on Business Process Management (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 3–16. |

32 | IBM (2020). What is IBM Business Automation Workflow? Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/products/business-automation-workflow [15.04.2020]. |

33 | Isik, O., van der Bergh, J., Martens, W. ((2012) ). Knowledge intensive business processes: an exploratory study. In: 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pp. 3817–3826. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2012.401. |

34 | Jochem, R., Geers, D., Heinze, P. ((2011) ). Maturity measurement of knowledge-intensive business processes. The TQM Journal, 23: (4), 377–387. |

35 | Kemsley, S. ((2011) ) The changing nature of work: from structured to unstructured, from controlled to social. In: Lecture Notes in Computer Science Business Process Management, pp. 2–2. |

36 | Kirchmayr, M., Müller, M., Penzenstadler, B., Sikora, E., Weyer, T. (2006). Essenzieller REMsES-Leitfaden. Requirements Engineering und Management Softwareintensiver Eingebetteter Systeme, REMsES-Konsortium, 36 pp. |

37 | Klun, M., Trkman, P. ((2018) ). Business process management – at the crossroads. Business Process Management Journal, 24: (3), 786–813. |

38 | Le Clair, C., Miers, D., Moore, C., Fowler-Cornfeld, E. (2011). Dynamic Case Management: Definitely Not Your Dad’s Old-School Workflow/Imaging System. Forester Report, 28 September 2011. |

39 | Marjanovic, O., Freeze, R. ((2012) ). Knowledge-intensive business process: deriving a sustainable competitive advantage through business process management and knowledge management integration. Knowledge and Process Management, 19: (4), 180–188. |

40 | Mendling, J., Pentland, B., Recker, J. (2020). Building a complementary agenda for business process management and digital innovation. European Journal of Information Systems, 29. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1755207. |

41 | Moore, C. (2017). Seven trends in adaptive case management (BPM) software. Retrieved from https://www.digitalclaritygroup.com/2017-seven-trends-adaptive-case-management-software/ [19.03.2020]. |

42 | Olding, E., Rozwell, C. (2015). Expand Your BPM Horizons by Exploring Unstructured Processes. Gartner Technical Report G00172387. |

43 | Palmer, N. ((2013) ). Thriving on adaptability: how smart companies win in data-driven world. In: Fisher, L. (Ed.), Intelligent BPM Systems: Impact and Opportunity. Future Strategies Inc., Ligthouse Point (USA), pp. 17–32. |

44 | Pegasystems (2020). Pega Platform. Retrieved from https://www.pega.com/products/pega-platform [31.03.2020]. |

45 | Pucher, M. (2010a). The Difference between DYNAMIC and ADAPTIVE. http://acmisis.wordpress.com/2010/11/18/the-difference-between-dynamic-and-adaptive/ [19.02.2020]. |

46 | Pucher, M. (2010b). The Difference between ACM and BPM. Retrieved from https://acmisis.wordpress.com/2010/10/01/the-difference-between-acm-and-bpm/ [21.02.2020]. |

47 | Pucher, M. ((2012) ). How to link BPM governance and social collaboration through an adaptive paradigm. In: Fisher, W.L. (Ed.), Social BPM: Work, Planning and Collaboration Under the Impact of Social Technology. Future Strategies Inc., Ligthouse Point, pp. 57–76. |

48 | Pucher, M., Ruhsam, C., Kim, T. ((2014) ). Towards a pattern recognition approach for transferring knowledge in ACM. In: 2014 IEEE 18th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference Workshops and Demonstrations. |

49 | Richter-von Hagen, C., Ratz, D., Povalej, R. ((2005) ). Towards self-organizing knowledge intensive processes. Journal of Universal Knowledge Management, 2: , 148–169. 2005. |

50 | Rodrigues, D., Baiao, F., Santoro, F., Netto, J. ((2015) ). Towards a context-based representation of the dynamicity perspective in knowledge-intensive processes. In: 2015 IEEE 19th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD). https://doi.org/10.1109/CSCWD.2015.7230952. |

51 | Smith, H., Fingar, P. ((2002) ). Business Process Management – The Third Wave. Meghan-Kiffer Press. |

52 | Szelągowski, M. ((2014) ). Becoming a learning organization through dynamic business process management. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation (JEMI), 10: (1), 147–166. |

53 | Szelągowski, M. ((2019) ). Dynamic BPM in the Knowledge Economy: Creating Value from Intellectual Capital. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems (LNNS), Vol. 71: . Springer International Publishing, Berlin, |

54 | Szelągowski, M. (2020). Knowledge and process dimensions. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-09-2019-0150. |

55 | Szelągowski, M., Berniak-Woźny, J. (2020). Business processes nature assessment matrix – a novel approach to the assessment of business process dynamism and knowledge intensity. Advances in Production Engineering & Management (APEM). |

56 | Taylor, F.W. ((1911) ). The Principles of Scientific Management. Harper & Brothers, New York. |

57 | Trkman, P. ((2009) ). The critical success factors of business process management. International Journal of Information Management, 30: (2), 125–134. |

58 | Ukelson, J. (2010). Adaptive Case Management over Business Process Management. Retrieved from http://it.toolbox.com/blogs/lessons-process-management/adaptive-case-management-over-business-process-management-40002 [7.04.2016]. |

59 | van der Aalst, W., Weske, M., Grunbauer, D. ((2005) ). Case handling: a new paradigm for business process support. Data & Knowledge Engineering, 53: , 129–162. |

60 | vom Brocke, J., Zelt, T., Schmiedel, T. ((2015) ). On the role of context in business process management. International Journal of Information Management, 36: (3), 486–495. |

61 | Zelt, S., Recker, J., Schmiedel, T., Brocke J, v. ((2018) ). A theory of contingent business process management. Business Process Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-05-2018-0129. DOI. |