Climate Change Exacerbated Sexual and Gender-Based Violence: Role of the Feminist Foreign Policy

Abstract

Feminist foreign policy (FFP) ensures the representation and participation of women both nationally and internationally. Initially, it aimed to focus on some special areas relating to women, peace and security especially sexual violence in conflict and women representation in peace process. Now, the ambit has been broadened and issues relating to climate change are also included. The research has already proved that women suffer double victimization as a consequence of climate change. Climate change exacerbates sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), so, they face all types of consequences of climate change (CC) and natural disasters as human beings but they face SGBV in particular because of their gender. The FFP states respect for international law and efforts to address gender inequalities and violence. Unfortunately, the existing international law e.g. the CEDAW or human rights treaties etc. generally or law on climate change e.g. the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement etc. specifically do not address the issue. Also, the interlinkage between climate change and SGBV has not been discussed earnestly. The FFP has been consistently pursued at the UNFCCC COP negotiations in the context of climate peace initiative etc and involved women especially local and indigenous in the decision-making process. Thus, the FFP can be one of the strongest global voices to end SGBV by ensuring women’s participation; addressing the legal gap; and advocating for the adoption of the gender-responsive law and policy both nationally and internationally. They can be a leader at the international level and a change-maker at the national level. This study has sought to explain how climate change exacerbated SGBV has emerged as a subject of FFP and how it can address the challenge of SGBV exacerbated by CC, the relevant legal issues therein and the road ahead.

1Introduction

Since the year 2014, with the initiative of Sweden, several countries have started giving a specific focus on what can be described as the ‘feminist foreign policy’ (FFP). Though, there is no concrete definition of FFP, still more countries are resorting to the FFP. It has been considered that FFP can provide a political framework for gender-related issues especially women, peace, security and gender equality. It can also assist the governments in implementing gender-related policies, strategies and legislations. It can coordinate and negotiate with the involvement of the highest levels of leadership. It can also help in transforming the foreign policy for gender equality and gender-responsive diplomacy, defence, security cooperation, trade, aid, climate security and even migration policies.1 On 1 January 2015, Annika Molin Hellgren was appointed as Sweden’s first Ambassador-at-Large for “Global Women’s Issues and the Coordinator of Sweden’s Feminist Foreign Policy.” The aim of the FFP is to:

‘respond to one of the foremost unresolved problems of our time, namely the fact that the human rights of women and girls are still violated in so many respects in so many parts of the world, including the developed countries.’2

According to Karin Aggestam and Annika Bergman-Rosamond:

‘Sweden seeks to promote women’s representation and participation in politics in general and in peace processes in particular; to advocate women’s rights as human rights, including women’s protection from sexual and gender-based violence; and to work toward a more gender-sensitive and equitable distribution of global income and natural resources.’3

An ethical foreign policy may lack the focus on gender injustice or SGBV etc. The FFP has been able to place gender equality, non-discrimination; and elimination of SGBV at the centre through analysis of foreign policy and its discourse.

2Advent of the Feminist Foreign Policy

The FFP includes women especially local and indigenous in the climate for peace initiative decision-making processes such as the negotiations at the Conference of the Parties (COP) and other subsidiary bodies of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).4 The FFP can be one of the instruments to address injustices and struggles for gender justice at the international level and national levels. It includes an analysis of women’s empowerment; protection of human rights of women and girls; reduction in gender inequality and violence. There is a growing scholarly scrutiny of the inter-governmental efforts in addressing issues of gender inequality, SGBV, protection of women across borders.5

It has been accepted especially by the United Nations6 that SGBV against women is a growing threat to international peace and security. There is a gap in security related foreign policy making, as gender is included rarely. It is clear that if foreign policy lacks gender aspects especially SGBV, it is not possible to achieve the overall goal of foreign policy especially sustainable development, peace and security.7 Climate change has emerged as one of the most prominent global problems. Though entire populations are affected by climate change, women and girls suffer the most. As a consequence of natural disasters and during Covid-19 pandemic, women faced heightened real-life challenges, especially being vulnerable to different forms of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV).

Women are exposed to SGBV due to weak or absence of social, economic, political security and the culture of widespread impunity to the perpetrators. In conditions driven by events such as pandemics, epidemics and climatic conditions, there is heightened risk of violence against women. It is clear that SGBV due to climate change imposes double economic burden on States. Climate change and SGBV cause economic loss for States, societies and families both individually and jointly. International law does not yield any international legal instrument that deals with SGBV against women during and after climate change-induced disasters. It is a new challenge for international law that needs to be duly addressed in a timely manner.8

The reports of the UN Secretary General (2023) and the resolution (2625 of 2022) of the UN Security Council (UNSC) have sought to ensure that the nexus between climate change and SGBV remains on the international peace and security agenda. The issue is sought to be addressed under the rubric of agenda items such as ‘climate, peace and security’ and ‘women, peace and security’. In fact, the UNSC has:

‘acknowledged this climate and peace and security nexus in the mandate of UNMISS for the first time, explicitly urging the incorporation of “gender-sensitive risk assessments on the adverse impacts of climate change” (resolution 2625 (2022)). That recognition underscores the need to bolster efforts to address the intricate relationship between climate change, gender and peace and security across peace operations and special political missions.’9

The Peace Building Support Office’s thematic review on ‘Climate-Security and Peace building’ highlighted the importance of gender responsive approach in future investment for climate security and peace building. It also accepted that there is a need for women’s participation and leadership in climate adaptation, mitigation and natural resource management. It requires targeted support to all gender related organizations and initiatives.10 As a result, the FFP aims to ensure women’s rights and representation. It would be possible only by continuous political efforts and resources. It should also be ensured that the resources are channelled to achieve gender equality, and fulfil the needs of women and girls. For instance, Canada’s feminist development policy appears to be grounded in the assumption that “women and girls have the ability to achieve real change in terms of sustainable development and peace, even though they are often the most vulnerable to poverty, violence and climate change.”11

3Climate Change Exacerbated SGBV

Climate change is rarely discussed in relation to violence against women. It has become one of the global common concerns due to its role as a contributing factor in exacerbating sexual and gender based violence (SGBV). Though entire populations are affected by climate change, women and girls face double victimization as human beings as well as because of their gender. During emergencies, especially conflicts and disasters, women are at high risk of SGBV because of crisis in the family and society. It also happens due to sudden breakdown of family and community structures arising from forced displacement. As a result, women and girls become more vulnerable and face physical, sexual, psychological harm as well as denial of resources or necessary services.12

Natural calamities due to climate change bring miseries by making women and girls vulnerable to SGBV. The linkage between climate change and SGBV has been amply examined in a cutting-edge scholarly work that show “women and girls are up to fourteen times more likely to be harmed during disaster”.13 It also heightens already existing gender inequality in the family, society, and State. Drought in East Africa has been affecting thirty-seven million people and by the year 2030, up to eighty-six thousand Kenyans will be impacted by sea level rising, coastal flooding and storm.

Natural calamities like drought imposes burden on women as primary food provider to the family to walk long distance for drinking water, food, fuel, etc and exposes to SGBV. When families are unable to meet their basic needs due to natural calamities, it results domestic violence, intimate partner violence, child marriage, trafficking etc.14 People who are working in agriculture sector losses job due to climate change. As a result, there is a frustration within the family and mostly women. They are subjected to intimate partner violence at home. For example, in Kenya, 75% people are dependent on agriculture for their primary income. Crop destruction, loss of livestock, loss of property and food crisis are the common result of climate change. Women pay the cost by becoming victim of SGBV either within family e.g., domestic violence, intimate partner violence, child marriage or outside family by becoming victim of rape of other forms of sexual violence while collecting food, fuel, water etc.15

SGBV is often used to reinforce existing gender inequality and control over natural resources that are in crisis due to climate change. For example, women of Zambia’s Western Province are forced to trade their bodies for fish from the local fishermen. It is also known as ‘sex-for-fish’ or ‘Jaboya’ in Kenya.16 As a result, the existing gender inequality in the society is increasing; safety of women and girls are in danger. It is all because of controlling the management of fisheries resources that are already in danger because of climate change.17 In Zambia’s Western Province, Kenya, Cambodia, Mexico also; women are often forced to trade their bodies to get fish from local fishermen for providing food to their family as well as to run their small business. Also, women are lagging behind through this exploitation from decision making process relating to sustainable management of fisheries.18

There are a few continents such as Europe, a related cost of living crisis and the ‘encroaching impact of climate change’ are linked with risk of increased violence against women. “In Spain, heat waves have been followed by an increase in domestic violence and femicides.”19 Thus, it exacerbates stress and irritation in relationship as a result there is increased risk of domestic violence and femicide. Though, immigrant women from lower socio-economic background are at high risk.20 In Kenya, women rangers experience intimate partner violence. Other women face physical and psychological violence when they engage themselves in economic activities in wildlife conservation. Even men who encourage women’s participation in these spheres are verbally abused by the perpetrators.21 Indigenous women who are working as defenders of protection of environment and climate change and human rights are exposed to SGBV globally to stop them from taking part in environmental policy making and environmental activism. Between year 2016 and 2019, there were 1,698 SGBV against women environment and human rights defenders recorded in Mexico and Central America.22 They are facing attack on their lands, livelihoods and their right to environment. As a consequence, they are losing their traditional knowledge besides exclusion from decision making.23

Climate change results natural calamities, people lose their land, house, property and push to displace and migrate to other places either within the country or cross international border. So, they become either internally displaced people or refugee or illegal immigrants. It is estimated by the UN Environment Programme that 80 percent of the people displace by climate change are women.24 When women are displaced, they are at greater risk of SGBV, according to Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights:

‘While they sleep, wash, bathe or dress in emergency shelters, tents or camps, the risk of sexual violence is a tragic reality of their lives as migrants or refugees,’ Bachelet said. ‘Compounding this is the increased danger of human trafficking, and child, early and forced marriage which women and girls on the move endure.’25

According to Astrid Puentes Riaño, Independent Consultant on human rights and climate change, “migration and forced displacement are among the most serious impacts of the climate crisis that are already impacting millions of people around the world.” She stated that there are migrant women who suffered SGBV under the protection of the authorities too and when they went to report it, they were imprisoned rather prosecuting the perpetrators.26 For example, “there are reports of migrant women who have suffered sexual violence while under the protection of the authorities and who, upon reporting it, instead of being protected, have been imprisoned”.27

4Role of the FFP in Addressing Climate Change-SGBV Linkge

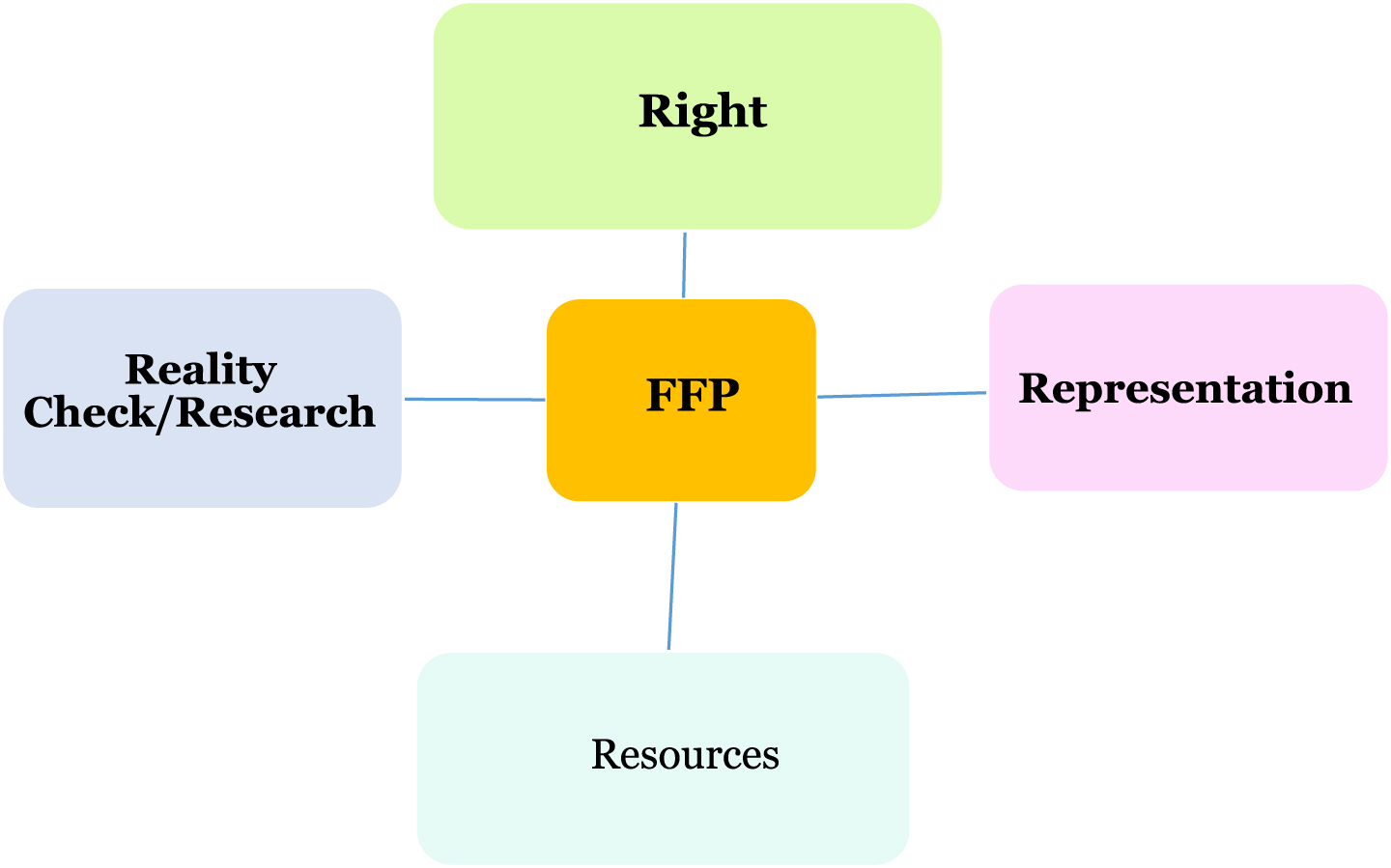

Initially, FFP pursued by Sweden (2014) was mainly based on three ‘r’ that representation, rights and resources. The fourth ‘r’ has been added by scholars that known as “reality check”, to ensure respect for local contexts and actors (see Fig. 1.).28 The initial aim was to support the female peace negotiators and women representation in peace process for a better and sustainable outcome.29 It has well established that women are not only victims-survivors rather actors in the FFP. Unfortunately, the participation of women is marginal in peace negotiation and reconstruction processes despite commitments at the global level by adopting both hard international and soft international laws.30

Fig. 1

Elements of the FFP. Source: By the author.

Some governments are planning to apply the FFP to other areas too like, peace and security, human rights, climate action etc. The approach is still in the process that criticises prioritizing national interest over women’s rights etc. It includes advancing women’s rights. The feminist approach to develop cooperation can help to place human rights of women and girls especially free from SGBV at the centre of any policy. Through FFP the women’s representation and participation can be ensured to address and eliminate SGBV due to climate change. Countries through their FFP can advocate for a umbrella institution within the United Nations system dedicated to address all forms of SGBV including SGBV due to climate change and boost women peace and security agenda of the United Nations.

The FFP can give special focus on respect to international law to end SGBV against women. The main task would be identifying the gaps within the existing law; mooting to fill the legal gaps; advocating adoption of gender approach to any policy and law such as in Europe, “promoting the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention) through foreign policy is gaining traction.” FFP offer a lens to address and end SGBV.31 Right means equal human rights which are stated under the international human rights law that should be respected and implemented. Women all over the world must be able to claim their universal rights; and to know that they are safeguarded from violence (rights). Countries should adopt a special international law or optional protocol to eliminate SGBV. The human rights of the women especially not to be subjected to SGBV shall not be compromised or legitimized by giving reasons of customs, religion or natural calamities, economic and social weakness of a State. The next step is that the women and girls must be represented and take part in political decisions (representation) it may be law making, law negotiating, executive or judicial. It may be at the local or international level. Women leadership at all the level should be promoted. There must be sufficient resources to achieve these goals (resources).32 Women should be included in the national budget and climate change budget. Their rights relating to property ownership, succession etc should be ensured.33 For example, Netherlands announced a budget of 510 euro million (2021-2025) for Sustainable Development Goal 5 fund for promoting women’s rights, gender equality, sexual and reproductive health and so on. The resources of the fund are using for promoting participation of women in political decision making, supporting entrepreneurship, and women rights organizations and human rights defenders.34

5Feminist Foreign Policy as a Change Maker

FFP advocates rights of the women through law. It highlights the gaps in the legal framework and actual practice, though around 189 countries ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), but many countries are unable to provide legal protection to women and girls in different areas like employment, violence etc. Unfortunately, there is no exclusive law relating to elimination of all forms of SGBV including SGBV due to climate change.35

From the beginning, environment and climate change instruments have not been gender sensitive. In the past ‘gender’ was given a low-key treatment. As a consequence, there is a gap in the legal protection for women and SGBV. There is a need to change the legislative framework. So far there is no international instrument on SGBV specifically.36 There is no specific or lex specialis binding legal instrument that deals with SGBV specifically during or after climate crisis or disaster. There are a few instruments mostly soft law or non-binding international law instruments that addressed the issue. This paragraph has identified the instruments and how they addressed the problem, solutions provided and the drawbacks of those instruments for further legal reform. There are a few international treaties both lex specialis and lex generalis that are mostly dealing with the issue of climate change or discrimination against women separately.

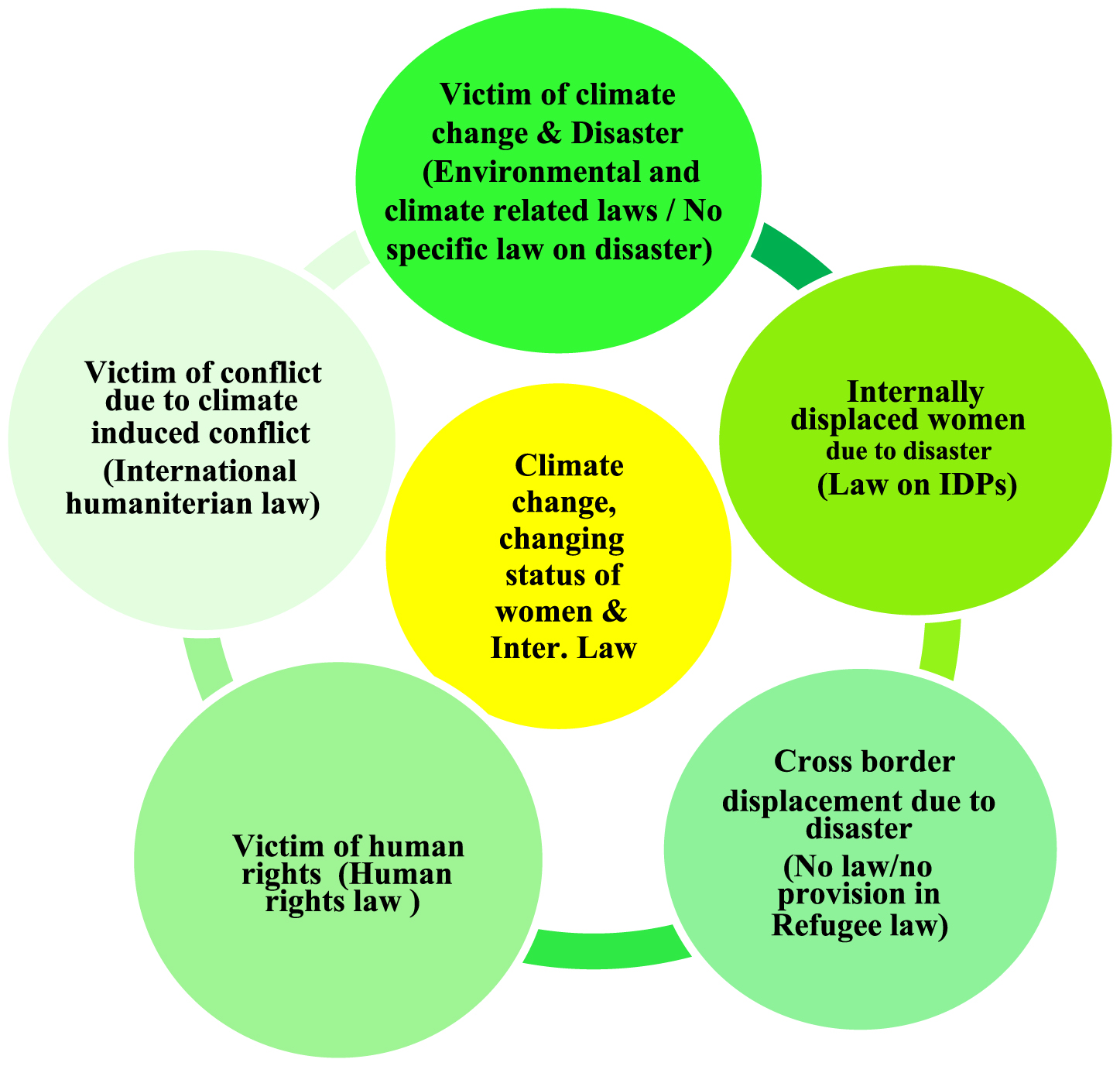

If we follow the above Fig. 2 and analyse instrumentalities in some areas of International Law that address the effect of climate change on women and girls, it shows a very few that specifically address the challenge. Climate change causes natural disasters and environmental degradation. As a result, women and girls suffer SGBV due to climate change. From the beginning, environment and climate change instruments have not been gender sensitive. In the past ‘gender’ was given a low-key treatment. As a consequence, there is a gap in the legal protection for women and SGBV.37

Fig. 2

Function of International Law in Climate Change Driven Challenges Affecting Women. Source: By the author.

The existing international environmental law and climate change is silent about this specific issue. Though recently, the Conference of the Parties (COPs) meetings of the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the 1997 Kyoto Protocol (KP); the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the 1994 UN Convention on Combating Desertification (UNCCD) have started considering and accommodating participation of women in climate change decision making processes by consideration of a gender sensitive approach.38

There is no specific binding international legal instrument on disaster management. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030) provides guidelines for the States as a nonbinding international instrument for disaster management. It mandated the participation of women and consideration of gender in disaster policy making, but the issue of SGBV not addressed specifically.39 Recently, the ‘Subsidiary Body on Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Draft Post-2020 Gender Plan of Action’40 has addressed the issue of SGBV against women environmental human rights defenders. It has been stated to “identify, eliminate and respond to all forms of gender-based discrimination and violence relating to control, ownership and to sustainable and conservation of biodiversity.” It has recommended some indicative actions such as develop and deploy data, tools, and strategies to understand and address gender-based violence and its linkages with biodiversity with a special focus on the protection of women environmental human rights defenders to support policy and programme development and implementation relating to biodiversity law.41 It has recommended the time frame up to the year 2026. It has also stated that data, knowledge products etc. on the links between gender-based violence and biodiversity should be produced and made available to parties and stakeholders.42

Another side the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, 1951 does not include climate-induced refugees and protection of women survivors due to climate change and natural calamities who crossed international borders. They are treated either illegal immigrants or internally displaced people or homeless people without any protection at the international level.43 Also, the law relating to the protection of internally displaced people especially women from SGBV is based on national law and States’ policies.44

It has already been discussed that climate change is one of the reasons for the crisis of natural resources, land degradation, and food and water crisis that results in conflict. Another side war or conflict is one of the reasons for climate crisis because of huge emissions of CO2. In both cases women face SGBV. The Geneva Conventions and the Optional Protocols deal with the protection of women and girls against SGBV in conflict zones, but without connecting with the issue of climate change. Also, all forms of SGBV are not mentioned. Article 27 of the Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of 12 August 1949 states that the ‘Parties to the conflict may take such measures of control and security regarding protected persons: Women shall be especially protected against any attack on their honour, in particular against rape, enforced prostitution, or any form of indecent assault.’45

The Additional Protocol I, 1977, Article 76 states that ‘women shall be the object of special respect and shall be protected in particular against rape, forced prostitution and any other form of indecent assault’. It is applicable only to international armed conflicts.’ 46 The Additional Protocol 1977 II, Article 4 states that the Parties to the conflict ‘shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever- outrages upon personal dignity, in particular, humiliating and degrading treatment, rape, enforced prostitution and any form of indecent assault’. It is applicable only for non-international armed conflicts. Ironically, the limited protection against SGBV under the IHL is based on an outdated notion of ‘honour’. Hence, it requires specific provisions that deal with rape and other forms of sexual violence against women. The concept of ‘honour’ is a gender-biased term.47

The 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), deals with discrimination against women, though SGBV has not been included within the text. There are a few General Recommendations (GRs. 12, 19 etc) of the Committee of CEDAW that addressed the issue of SGBV under the rubric of discrimination.48 The CEDAW is a human rights treaty, but does not specifically address SGBV or climate-induced SGBV. But recently, there are a few GRs of the Committee of CEDAW addressed the issue. GR 37 states the gender-related dimensions of disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change.49 It is stated that:

Because of increased forms of SGBV due to climate crisis, women are unable or less able to adapt to changes in climatic conditions. Though climate change mitigation and adaptation programmes create opportunities especially employment opportunities in different sectors including agriculture, energy etc. Unfortunately, these programmes failed to address the indifferent increased forms of SGBV due to climate change that create structural barrier for the women to access the opportunities.50

The problems have already been discussed in the above paragraphs, this paragraph had analyzed the solutions or recommendations provided by the GR 37. The text of GR37 addressed the issue of gender-related dimensions of disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change. There is only one paragraph VI has specifically focused on the ‘right to live free from gender-based violence against women and girls.’ By referring GR 35, it has mentioned that disaster and degradation and destruction of natural resources are the factors that “affected and exacerbated gender-based violence (GBV) against women and girls.” It also stated that ‘sexual violence’ is common in humanitarian crisis and may become acute during disaster as it heightens stress, lawlessness, and homelessness.51 It has been recommended for the States which are not binding. First, develop policies and programmes to address the existing and new forms of GBV that are the direct and indirect result of climate change and disaster and promote participation and leadership of women in the development of disaster risk reduction and climate change.52 It should be recognized and accepted at all levels that women and girls are facing increased forms of GBV in addition to all other consequences of the climate crisis. Neither any other group of gender is facing this differentiated effect of climate crisis. Second, it is suggested that the States should ensure the minimum legal age of 18 Years for girls and boys for marriage to stop child and forced marriage which is one of the forms of GBV that heightens during the climate crisis. Proper training should be given to all personnel involved in disaster response activities regarding the prevalence of forced and early marriage. For these, partnerships should be created with women’s associations and other stakeholders, and mechanisms should be established within local and regional disaster management plans to prevent, monitor and address the problem.53

Third, the survivors should be provided accessible, confidential, supportive and effective mechanisms that they can report their sufferings. Fourth, the programmes relating to disaster risk reduction and climate change should include a system for “regular monitoring, evaluation of interventions designed to prevent and respond gender-based violence”.54 Fourth training, sensitization and awareness for the authorities, emergency service workers and other groups on various forms of gender-based violence that occur during the situation of disaster and the process of preventing and addressing them. The training should include the rights and needs of women, especially indigenous, minority groups, disabled, and LGBTQIA+.55 Fifth, there is a need to adopt long-term policies and strategies to address the root causes of GBV in situations of disaster that should include and engage men and boys, the media, traditional and religious leaders and educational institutions to eliminate GBV and social and cultural stereotypes relating to the status of women.56

These are recommendations which are not specific to SGBV but rather in general that are also useful. There should be recognized and accepted at all levels that women and girls are facing increased forms of SGBV in addition to all other consequences of the climate crisis. Neither any group of gender is facing this differentiated effect of climate crisis. The categorisation of women and girls who are subjected to these specific forms of SGBV due to climate crisis comprise:

. . . women living in poverty, indigenous women, women belonging to ethnic, racial, religious and sexual minority groups, women with disabilities, refugee and asylum-seeking women, internally displaced, stateless and migrant women, rural women, unmarried women, adolescents and older women, who are often disproportionately affected compared with men or other women.57

Women’s participation should be ensured at all levels of decision-making relating to climate change as well as all other policies and laws that are the result of climate change such as refugee and IDPs laws, human rights, war or conflict-related laws. As it has already been identified that disaster, displacement, war or conflicts, and human rights violations are the consequences of climate crisis and laws are also different.58 Thus, including gender perspective and SGBV only in one area of law e.g. environment and climate will not solve the problem. There is a need to take multidisciplinary initiative. First identification of areas then action should be taken to reform the laws.

Though it has been mentioned in the GR37 how much women are vulnerable it is not about vulnerability rather it is the question of the right not to be subjected to SGBV due to the climate crisis. When women are not contributing to climate change at a huge level why they will bear the cost of climate change.59 The GR37 has referred the COP 20, decision 18 and COP 23, decision 3 of the UNFCCC also known as the “Lima Work Programme on Gender” and “Establishment of a gender action plan” respectively and suggested “full, equal and meaningful participation of women and promote gender-responsive climate policy and the mainstreaming of a gender perspective into all elements of climate action”. Now the question is what full, equal and meaningful participation is. How does it should be ensured at the bottom or grassroots level?60

The consideration relating to gender equality should be based on intergenerational equity. The effect of SGBV is perpetual and can be stopped only by considering the intergeneration equity approach.61 The GR has suggested three principles “equality and non-discrimination, participation and empowerment, accountability and access to justice — are fundamental to ensuring that all interventions relating to disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change are implemented in accordance with the Convention.” Though SGBV is analysed under the shed for non-discrimination but it reduces the effectiveness and importance of ending SGBV. Though women face different types of discrimination, but SGBV has perpetual effect and difficult to identify or measure the cost. The physical harm can be measured but to what extent we can calculate the sufferings of a woman who is broken inside.62

Strengthen national institutions, national law concerned with gender-related issues and women’s rights, civil society and women’s organizations and provide them with adequate resources, skills and authority to lead, advise, monitor and carry out strategies to prevent and respond to disasters and mitigate the adverse effects of climate change.63

General Recommendation 38 (2020) on Trafficking in women and girls in the context of global migration addressed the issue that trafficking and other forms of SGBV are often exacerbated during disaster. States Parties can not excuse the obligation in the context of a State emergency. There is a need to address the issue of how women and girls especially displaced women and girls are subjected to GBV and specifically sexual violence as displaced girls are trafficked for sexual purposes. The solutions provided in general for trafficking are also applied during emergencies like disasters. There is need of identifying the victims; providing training to the staff; arrangement of single sex accommodation for the displaced women and girls, more female officers; adequate living facility; adoption of ‘zero tolerance of trafficking’, sexual exploitation and forced labour, slavery; access to complaint procedure and redress mechanism; use of digital technology artificial intelligence (AI) especially to call social media data analysis etc; raising awareness; upholding victims’ rights; right to information about rights and legal assistance; right to remedy; gender-sensitive court proceedings; data collection and legislative, policy and institutional frameworks; States parties are encouraged to ratify or accede to “(a) Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; (b) Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children and the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime”.64 OHCHR General Recommendation 39, (2022) on the rights of Indigenous women and girls. Environmental human rights defenders especially indigenous women face harassment, SGBV. The States parties have obligations to ensure take measures without delay to prevent the SGBV against these women.65

6Role of the United Nations Resolutions

The UN General Assembly (GA) has adopted many resolutions for the protection of women and girls against SGBV. Though these resolutions are mainly deal with the SGBV during peacetime or armed conflicts for example, the UNSC resolutions under the agenda of ‘women peace and security’ e.g., resolutions 2467 (2019),2331 (2016), 2242 (2015), 2106 (2013), 1960 (2010), 1888 (2009), 1820 (2008), 1325 (2000). Though these resolutions did not address the specific issue of SGBV due to climate change it has explained the issue of SGBV and conflict. Thus, it can be used as a guideline for the protection of SGBV during conflicts that happen due to climate change.66

There are a series of resolutions adopted by the Human Rights Council (HRC) on human rights and climate change. A few of the resolutions have addressed the issues of SGBV and climate change. The HRC has tried to show the link between human rights and climate change by adopting these resolutions. It has clarified how climate change affects the human rights of all including women.67 Though these resolutions, 50/9 (July 2022); 47/24 (July 2021); 44/7 (July 2020); 42/21 (July 2019); 38/4 (July 2018); 35/20 (July 2017);32/33 (July 2016); 29/15 (July 2015); 26/27 (July 2014); 18/22 (September 2011); 10/4 (March 2009); 7/23 (March 2008).68 (50/9 to 32/33) did not address the issue of SGBV in the context of climate change, but these stated that women and girls may be disproportionately affected by the effects of climate change.

Thus, there is a need for the participation of women especially older women and girls in climate action69 and study on gender-responsive climate action for the full and effective participation of the human rights of women.70 Intergenerational equity: (29/15 to 10/4) only stated the issue of gender in the context of individual vulnerability based on gender factors. The HRC has also addressed the issue of the climate change and its impact on human rights in the framework of its work on ‘human rights and the environment’ by adopting resolutions, 16/11 (2011), 19/10 (2012), 25/21 (2014), 28/11 (2015), 31/8 (2016), 34/20 (2017), 37/8 (2018), 46/7 (2021) and 48/13 (2021).71 The HRC has established the mandate of a Special Rapporteur regarding the protection of human rights in the context of climate change by adopting resolution 48/14 in 2011.72

It enlisted the specific resolutions that are dealing with climate-induced SGBV and provided solutions to this global problem for example, UN GA Res. 77/202 (2022) on ‘child, early and forced marriage’73 explained that climate change is one of the root causes of child, early and forced marriage, and female genital mutilation. These are the specific forms of SGBV against girls.74 It urges States to recognize and promote awareness of the disproportionate and distinct effects of climate change, environmental degradation and disasters on women and girls. It urges to take targeted action to strengthen the resilience and adaptive capacities of all women and girls.75 There is a need to take a comprehensive, rights-based, age-and gender-responsive, survivor-centred and multisectoral approach that considers linkages. Also, need to pay attention to the specific needs of all women76 capacities of all women and girls.77

The UNGA resolution 77/194 (2022) on ‘trafficking in women and girls’78 addressed that climate change heightened the risk of trafficking of women and girls.79 There is a need to fully and effectively implement the relevant provisions of the United Nations Global Plan of Action to Combat Trafficking in Persons. It urges Governments to devise, enforce and strengthen effective gender-responsive and age-sensitive measures, and take preventive actions, including legislative measures. All forms of trafficking should be criminalized and encourage Governments to fulfil their obligations under international law to prevent, combat and eradicate trafficking in persons. There is a need to provide training for law enforcement and border control officials, as well as medical personnel in identifying potential cases of trafficking. Systematic collection of gender disaggregated data is one of the important needs for the time. Though this resolution provided measures that should be applicable during all the times in general but it did not highlight any specific measures for climate change or disaster-induced trafficking.

Similarly, the UNGA resolution 77/193 (2022) on ‘intensification of efforts to prevent and eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls: gender stereotypes and negative social norms is deeply concerned, especially for developing countries and small island’s girls and women. They are “disproportionately affected by the adverse effect of climate change, environment degradation, biodiversity loss, extreme weather and natural disaster and other environment issues as these may exacerbate existing structural inequalities as well as violence against women and girls and harmful practices” e.g. forced marriage and FGM.

It was emphasized that there is a lack of sufficient data and understanding about the impact of climate change and environmental degradation on violence against women and girls. The negative impact of climate change needs to be comprehensively assessed and addressed.80 Though the solutions as recommendations are provided in general specific solutions have not been provided relating to the role of climate change in exacerbating SGBV. It urges States to take comprehensive, multisectoral, coordinated, effective and gender-responsive measures to prevent and eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls and to address structural and underlying causes and risk factors,81 engaging, educating, encouraging and supporting men and boys to be positive role models for gender equality and to promote respectful relationships. States to take immediate and effective action and ensuring legislation to prevent, investigate, prosecute and hold to account the perpetrators. Removing all barriers to women’s access to justice and accountability mechanisms. Provide victim-centred legal protection. States to systematically collect, analyse and disseminate data disaggregated.

Also, the approach of FFP towards climate actions including legal actions provides a unique opportunity to transform legal, institutional, and policy relating to climate change and include gender as one of the important components that need to be included. It can ensure the most important process the participation of women in climate decision-making at all levels.82 It can highlight the gaps within the law and provide suggestions that would be applicable across sectors.

7Conclusion

Though there are reports about the FFP is no longer being practised by Sweden,83 many countries are still focusing on the importance of the FFP, wherein climate change and gender violence are interlinked. Hence, a strong gender perspective seems to be the need of the hour in articulating climate change policies.84 For instance, on the platform of the Dubai COP 28 of the UNFCCC (November 30 - December 13, 2023), the demand for feminist climate justice was raised to interlink the suffering of women and girls to climate change.85 It has already been realized that FFP can be one of the important tools in the over goal for the elimination of SGBV against women especially exacerbated by climate change. It is still in evolution and widening the scope. It can work as a conduit for both the international and national systems so as to coordinate greater participation and representation of women for gender equality and elimination of SGBV both during peace and conflicts. It calls for a specialized international treaty or an optional protocol to the 1949 Geneva Conventions for the elimination of all forms of SGBV including climate-induced SGBV. Moreover, it seems, the time has come to constitute a specialized Gender Rights Council (GRC) on the lines of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) as an umbrella institution to coordinate all the gender related programs of the entire United Nations system. The UNGA needs to take the lead in this respect by adopting an appropriate resolution comprising institutional structure of such GRC for coordination of all gender related works, programs and institutions, globally.

Notes

1 In October 2022, this list included Sweden (2014), Canada (2017), France (2019), Mexico (2020), Spain (2021), Luxembourg (2021), Germany (2022), Chile (2022), Colombia (2022) and Liberia (2022), see, UN Women (2023), “Feminist Foreign Policies: An Introduction”; available at: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Brief-Feminist-foreign-policies-en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023)

2 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Sweden (2015), “She is the first Ambassador of her kind”; 19 February 2015, available at:https://www.government.se/articles/2015/02/she-is-the-first-ambassador-of-her-kind/en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

3 Karin Aggestam and Annika Bergman-Rosamond (2016), “Swedish Feminist Foreign Policy in the Making: Ethics, Politics, and Gender”, Ethics & International Affairs, 30 (3), 323-334; Kristen P. Williams (2017), “Feminism in Foreign Policy”, Oxford Research Encyclopaedias, Politics, (OUP, UK, 2017); available at: Feminism in Foreign Policy | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics (accessed on 09- January 2024).

4 Federal Foreign Office (2023), “Shaping Feminist Foreign Policy: Federal Foreign Office Guidelines”; Berlin; available at: http://www.diplo.de/en/shaping_faminist_foregin_policy/guidelines.pdf (accessed on 03 December 2023)

5 Karin Aggestam, Annika Bergman Rosamond and Annica Kronsell (2019), “Theorising feminist foreign policy”, International Relations, Vol. 33(1) 23–39.

6 UN Women, “Facts and figures: Women, peace, and security”; November, 2023; available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/peace-and-security/facts-and-figures#edn51.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2023).

7 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Sweden, n.2

8 Bharat H. Desai and Moumita Mandal (2021), “Role of Climate Change in Exacerbating Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Women: A New Challenge for International Law”, Environmental Policy and Law, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 137-157; available at: epl210055 (iospress.com) (accessed on 15 January 2024).

9 UNSC (2023), “Women, Peace and Security: Report of the Secretary-General”, UN Doc. S/2023/725, 28 September 2023; available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N23/279/08/PDF/N2327908.pdf?OpenElement.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2023). Also see, UN Women, n.6.

10 Ibid.

11 Karin Aggestam et. al. (2019), n. 4.

12 Bharat H. Desai and Moumita Mandal (2021), n. 8.

13 Ayat Soliman, et al (2022), “Climate change and gender-based violence - interlinked crises in East Africa”, the World Bank Blog; available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/climatechange/climate-change-and-gender-based-violence-interlinked-crises-east-africa.html (accessed on 07 June 2023).

14 Anik Gevers, etc al. (2020), “Why climate change fuels violence against women,” UNDP; available at: https://www.undp.org/blog/why-climate-change-fuels-violence-against-women.html (accessed on 27 June 2023).

15 Elizabeth M. Allen, et al (2021), “Kenyan Women Bearing the Cost of Climate Change,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 18(23), 12697; available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/23/12697.html (accessed on 26 June 2023).

16 Mark Lowen (2014), “Kenya’s battle to end ‘sex for fish’ trade”, BBC, 17 February 2014; available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-26186194.html (accessed on 16 June 2023).

17 IUCN (2023), “IUCN supports five new projects to address gender-based violence related to climate change and environmental degradation”; June, 2023; available at: https://www.iucn.org/press-release/202304/iucn-supports-five-new-projects-address-gender-based-violence-related-climate.html (accessed on 07 June 2023).

18 Ibid.

19 European Parliament (2022), “Violence against women in the EU State of play”; October, 2022 available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/739208/EPRS_BRI(2022)739208_EN.pdf (accessed on 05 October 2023).

20 “Over this period, 23 women were killed by their current or former partners; 38,000 police complaints were filed for gender violence, and 61,000 calls were made to the 016 helpline for victims of domestic abuse . . . that 40% of women murdered in Spain by their partners or former partners were immigrants, predominantly from Ecuador, Morocco and Bolivia,” see, Manuel Ansede (2018), “Do heat waves fuel domestic violence?”, EL Pais, Spain, 25 July 2018; available at: https://english.elpais.com/elpais/2018/07/24/inenglish/1532429737_500658.html (accessed on 05 October 2023).

21 IUCN (2023), n. 9.

22 CSW66 (2022), “Tackling Violence Against Women and Girls in The Context of Climate Change”; July, 2022; available at: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Tackling-violence-against-women-and-girls-in-the-context-of-climate-change-en.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2023).

23 Ibid.

24 OHCHR (2022), “Climate change exacerbates violence against women and girls”; June, 2022 available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2022/07/climate-change-exacerbates-violence-against-women-and-girls.html (accessed on 16 June 2023)

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Geoffrey Ondieki, et al (2023), “Climate change puts more women at risk for domestic violence,” The Washington Post, 3 January 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/01/03/domestic-violence-climate-change-umoja/en.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2023).

28 Johanna Nelles (2023),“A trend that’s catching on? Feminist foreign policy and international efforts to end violence against women”, McGill Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism; 8 March 2023; available at: https://www.mcgill.ca/humanrights/article/trend-thats-catching-feminist-foreign-policy-and-international-efforts-end-violence-against-women.html (accessed on 07 November 2023).

29 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Sweden (2016), “Interest in Brussels for the Feminist Foreign Policy,” 02 November 2016; available at: https://www.government.se/articles/2016/11/interest-in-brussels-for-the-feminist-foreign-policy/en.html (accessed on 31 October 2023).

30 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Sweden, n.2

31 Johanna Nelles (2023), “A trend that’s catching on? Feminist foreign policy and international efforts to end violence against women”; 8 March, 2023; available at: https://www.mcgill.ca/humanrights/article/trend-thats-catching-feminist-foreign-policy-and-international-efforts-end-violence-against-women.html (accessed on 30 November 2023).

32 Government of Netherlands (2022), “Feminist foreign policy explained”, 18 November 2022; available at: https://www.government.nl/latest/news/2022/11/18/feminist-foreign-policy-netherlands.html (accessed on 07 November 2023).

33 Johan Frisell (2019), “The Swedish Feminist Foreign Policy” Heinrich Boll Stiftung: Green Political Foundation; August, 2019; available at: https://eu.boell.org/en/2019/08/28/swedish-feminist-foreign-policy.html (accessed on 04 December 2023).

34 Government of Netherlands (2022), n. 32.

35 Federal Foreign Office (2023), n. 4.

36 Moumita Mandal (2023), “Climate Change & Gender-Based Violence”, Workshop Report, GCR21; 25 July, 2023; available at: https://www.gcr21.org/the-centre/news/year/current/workshop-report-climate-change-gender-based-violence.html (accessed on 14 November 2023).

37 Ibid.

38 “UNFCCC: decision36 of the COP7 (2001); Decision 1 of COP16(2010); 2012, COP18 (decision23); 2014 COP20 (decision18); 2015Paris Agreement (COP 21, decision1); 2016 COP22 (decision21); 2017 COP23 (decision3); 2018 COP24; 2019 COP25 (decision3). The UN Convention on CombatingDesertification,1994(UNCCD): 2015COP12 (decision29); 2017 COP13 (decision30). The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD): TheCOP-10 (decision/19, 2010)”; see, Bharat H Desai and Moumita Mandal (2021), n.8.

39 UNDRR (2015), “What is the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction?”; March, 2015; available at: https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/what-sendai-framework.html (accessed on 16 September 2023).

40 CBD Secretariat (2022), The Convention on Biological Diversity, Subsidiary Body on Implementation, “Draft Post-2020 Gender Plan of Action, Third meeting (resumed) Geneva, Switzerland, 12 –28 January 2022 Agenda item 5, UN Doc. CBD/SBI/3/4/Add.2/Rev.2 21 November 2021”; available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/0919/6830/6fe8d737b8192a39f3378e23/sbi-03-04-add2-rev2-en.pdf (accessed on 07 August 2023).

41 Ibid, p. 8.

42 Ibid.

43 The Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, 1951; available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-relating-status-refugees; https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/refugees.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2023).

44 UNHCR (2020), “Global report on law and policy on internal displacement: Implementing National Responsibility”; 9 January, 2020; available at: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/6401d5624.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2023).

45 The Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, 12 August 1949; available at: https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.33_GC-IV-EN.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

46 Protocols Additional to Geneva Conventions 1977; available at: https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/icrc_002_0321.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

47 Bharat H Desai and Moumita Mandal (2021), n.8.

48 The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, New York, 18 December 1979; available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women.html (accessed on 14 September 2023); General recommendation No. 12 –eighth session, 1989 violence against women; General recommendation No. 19–eleventh session, 1992 violence against women; see, General recommendations of adopted by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW); available at: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/recommendations/index.html (accessed on 14 September 2023).

49 UN Digital Library (2018), “General recommendation No. 37 (2018) on the gender-related dimensions of disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change”; 29 November, 2018; available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1626306.en.pdf (accessed on 01 August 2023).

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid, para. 55-56

52 Ibid, para.57

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid, para 19.

60 Ibid, para 20.

61 Bharat H Desai and Moumita Mandal (2023, 2022), Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in International Law: Making International Institutions Work, Springer Nature: Singapore. S (English and German editions; accessed on 7 January 2024).

62 Ibid.

63 Ibid.

64 The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women(2020), “General recommendation No. 38 (2020) on trafficking in women and girls in the context of global migration”, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/GC/38, 20 November 2020; available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N20/324/45/PDF/N2032445.pdf?OpenElement.html (accessed on 11 August 2023).

65 The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (2022), “General recommendation No. 39 (2022) on the rights of Indigenous women and girls”, UN Doc. CEDAW/C/GC/39, 31 October 2022; available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-recommendation-no39-2022-rights-indigeneous.html (accessed on 11 August 2023).

66 UNSC (2019), “United Nations Security Council Resolutions”; 25 April, 2019; available at: https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/digital-library/resolutions/en.html (accessed on 14 August 2023).

67 OHCHR (2022), “Human Rights Council resolutions on human rights and climate change OHCHR and climate change”; July, 2022; available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/climate-change/human-rights-council-resolutions-human-rights-and-climate-change.html (accessed on 12 August 2023).

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid. Human Rights Committee (2022), HRC Res. 50/90, UN Doc. A/HRC/RES/50/9, 14 July 2022; available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G22/406/80/PDF/G2240680.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2023).

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 UNGA (2023), Resolution 77/202, “Child, Early and Forced Marriage”; UN Doc. A/RES/77/202, 3 January 2023; available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/760/69/PDF/N2276069.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2023).

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 Ibid.

77 Ibid.

78 UNGA (2022), Resolution 77/194 on “Trafficking in women and girls”; UN Doc. A/RES/77/194, 30 December 2022; available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/759/64/PDF/N2275964.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2023).

79 Ibid.

80 UNGA (2023), Res. 77/193, “Intensification of efforts to prevent and eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls: gender stereotypes and negative social norms”, UN Doc. A/RES/77/193, 30 December 2022; available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/759/58/PDF/N2275958.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2023).

81 Ibid.

82 IDLO (2022), “Feminist Climate Action and The Rule of Law”, Webinar, 16 March 2022, New York; available at: https://www.idlo.int/news/events/feminist-climate-action-and-rule-law.html (accessed on 14 November 2023).

83 Hanna Walfridsson (2022), “Sweden’s New Government Abandons Feminist Foreign Policy: Policy Reversal is a Step in the Wrong Direction”; Human Rights Watch; available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/31/swedens-new-government-abandons-feminist-foreign-policy.html (accessed on 06 December 2023).

84 Henrich Boll Stiftuing (2023), “German Feminist Foreign Policy - Speech by Luise Amtsberg”; available at: https://eu.boell.org/en/2023/08/03/speech-luise-amtsberg.html (accessed on 06 December 2023).

85 UNFCCC (2023), “Information Session on Gender at COP 28 10 November 2023 –14 : 00”; available at:https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Information%20Session%20on%20Gender%20at%20COP%2028.pdf (accessed on 06 December 2023).