Just Pathways to Sustainability: From Environmental Human Rights Defenders to Biosphere Defenders

Abstract

People form part of the biosphere - the biosphere being the whole intertwined network of life on Earth. While there is convergence on the need for societal change for just sustainability and a healthy biosphere, the pathways to achieve these transformations remain relatively unclear. Through legal interpretation, conceptual and thematic analysis of academic and grey literature, we seek to answer the following two questions: (a) how does the concept of Biosphere Defender enable a deeper and distinct understanding of who environmental defenders are and their role in just sustainability transformations? and (b) how does international human rights law contribute to specify the content of biosphere defenders’ rights? To address these questions, we first critically review the scope and limitations of the notion of Environmental Human Rights Defenders (EHRD) in human rights narratives in international law and policy. We examine how understandings of EHRD portray those defending their land and environment and what limitations this concept has in terms of possibilities for reflecting on transformations towards just sustainability. Second, we propose an alternative and/or complementary understanding of EHRD by using the concept of Biosphere Defenders. We also develop the Defend-Biosphere Framework to analyse the role of these actors as agents of change in pathways towards just sustainability. Third, to empirically illustrate the role of Biosphere Defenders, and the use of the Defend-Biosphere Framework we present two case studies from Latin America analyzing initiatives catalyzed by rural people who are defending their lands and territories while generating new ways to relate to socio-ecological systems and engage with the State and the economy. In both case studies, we find that relational values of solidarity, responsibility, and care (between human and other living beings) are central in understanding Biosphere Defenders’ initiatives creating pathways towards just sustainability. The findings of this article are of particular relevance to the implementation of the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in the context of the Escazu Agreement on access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, the Aarhus Convention on access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters and the Montreal-Kunming Global Biodiversity Framework in particular Target 22 (access to information, participation, access to justice and environmental defenders) and Target 23 (gender equality).

1Introduction

Humanity is at a crossroads for building a shared future for all life in the biosphere- the intertwined network of life on Earth. IPBES (2019) Global Biodiversity Assessment shows that the biosphere is at risk due to biodiversity loss, climate change and other human-induced changes such as land use changes, urbanization, industrial agriculture and aquaculture expansion. Approximately, one million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction.1 Significant economic, social and cultural implications are emerging from biodiversity loss and ecosystems degradation at an unprecedented scale and magnitude.2 IPBES (2019) warns that trends in climate change, increasing land/and sea-use change, and exploitation of living beings are negatively affecting ecosystem functions and nature’s contributions to people and these trends are projected to continue to 2050 except in scenarios of transformative change. IPBES assessments converge with significant academic literature focusing on sustainability transformations to address structural and systemic social-ecological and equity challenges.3

Awareness is emerging by UN human rights review mechanisms specifically by certain UN Special Rapporteurs of the relevance of IPBES Assessments for conducting evidence-based analysis on human rights. For example, David Boyd, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment as well as other UN Special Rapporteurs including Hilal Elver, Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food; Léo Heller, Special Rapporteur on the human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation, have warned that failing to protect biodiversity can be a human rights violation. 4 The IPBES’s global report should be setting off alarm bells about the urgency of transforming economies and societies in cleaner, and greener directions.5 Yet, it is not well understood how the IPBES assessments can contribute to understand the role of human rights defenders in the construction of just pathways to sustainability.

In this article, we put into conversation two seemingly different bodies of literature relevant to governing the biosphere: IPBES assessments and associated scholarly work and human rights legal analysis. Human rights defenders have catalysed transformative change in turbulent times from the end of slavery and Apartheid to women’s right to vote6 and recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights after colonial dispossession. Therefore, we see value in understanding human rights defenders through the lenses of the IPBES insights for just sustainability transformations. While most of the attention on environmental human rights defenders (EHRD) has been placed in protecting them due to the risks that they face of being threatened or even assassinated, we argue that equally important is to understand their role as agents of change and as central actors in the construction of just sustainability pathways. Attention on the rights of EHRD is not only important because they are ‘vulnerable’ or ‘at risk’ but also because many defenders represent alternative understandings and ways of valuing and making use of nature, crucial for socio-ecologically sensitive and just sustainability transformations. In this sense, EHRD are agents of change and not only victims. Furthermore, EHRD are central socio-economic, political and ecological agents to learn from for advancing policy and law towards just sustainability.

In this article, we address the following two questions: (a) how does the concept of Biosphere Defender enable a deeper and distinct understanding of who environmental defenders are and their role in just sustainability transformations? and (b) how does international human rights law contribute to specify the content of biosphere defenders’ rights?

We use a legal interpretation method, a systemic interpretation approach7 and conceptual and thematic analysis of academic and grey literature to address our research questions. We use human rights law treaties, UN Human Rights Council and UN General Assembly resolutions, as well as UN human rights Special Rapporteurs’ reports to clarify who defenders are and the rights of these defenders who defenders are and their rights. A novel approach of this article is to use the IBPES Global Assessment for conceptualizing biosphere defenders and their role in just sustainability transformations.

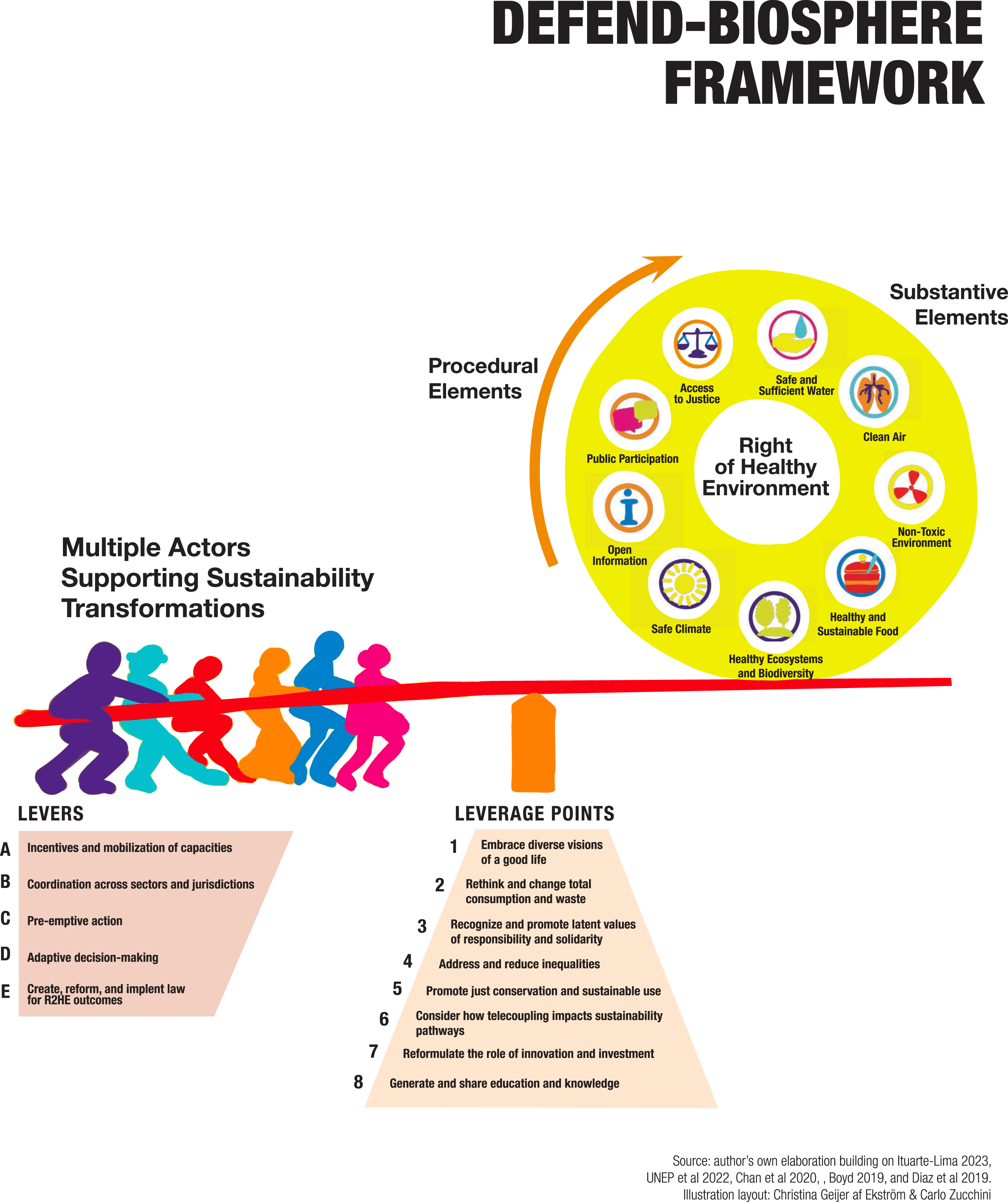

Based on an extensive literature review, IPBES (2019) Chapter 5 authors identify the most important elements needed for pathways to sustainability.8 This Chapter 5 on pathways towards a sustainable future is then further elaborated in Chan et al. (2020).9 Having in mind policy and legal interventions towards just societal transformations, the authors identified eight ‘leverage points’ or priority issues, namely: “(1) visions of a good life, (2) total consumption and waste, (3) latent values of responsibility, (4) inequalities, (5) justice and inclusion in conservation, (6) externalities from trade and other telecouplings, (7) responsible technology, innovation and investment, and (8) education and knowledge generation and sharing”.10 The authors further identified five multi-actor governance approaches or ‘levers’ which can be applied across the key priority issues for intervention, namely: (i) incentives and capacity building, (ii) coordination across sectors and jurisdictions, (iii) pre-emptive action, (iv) adaptive decision-making and (v) environmental law and implementation. In our case studies, we investigate what levers, and leverage points are at play and what we can learn from them to think about alternative ways of sustainable ‘development’ and of building a good life on Earth where both human and non-humans are included.

In Section 2, we critically review the scope and limitations of the notion of EHRD in human rights narratives (policy and law). We also propose an alternative understanding of EHRD by using the concept of Biosphere Defender to focus on these actors as agents of change in pathways towards just sustainability. In Section 3, we present the Defend-Biosphere Framework and in Section 4 we empirically illustrate the use of this framework to show the role of biosphere defenders in different socio-ecological, political, and economic, context and the way they generate new ways to relate to nature, the economy, and the state.

2Rationale Behind the Biosphere Defenders Concept

2.1Emergence of Environmental Human Rights Defenders (EHRD)

In UN human rights fora, progressive developments on human rights defenders have emerged since the late 1970 s. In 1979, the UN Human Rights Commission urged States to support those promoting the effective observance of human rights. In 1998, the UN General Assembly -the highest level at the UN- adopted by consensus the United Nations Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms11 commonly known as the Declaration on HRDs. The United Nations12 highlights that the term “human rights defender” has been seen as a more relevant and useful term than other terms previously used before the Declaration on HRDs such as human rights “activist”, “professional”, or “worker” which before this Declaration had been more common.

Different terms have been used to enunciate those subjects that mobilize against environmental pollution, degradation, or extractive (and conservation) activities that bring displacement, and violence: ‘environmental defenders’, ‘environmental activists’, ‘defenders of the earth’, environmental and land defenders’, all of which have more recently been conceptualized as EHRD. According to Knox (2015:522) the UN Human Rights Council has emphasized state obligations in relation to defenders “to take all necessary measures to protect the legitimate exercise of everyone’s human rights when promoting environmental protection and sustainable development” as far back as 2003.13 Knox (2017: preface) uses this term to refer to “individuals and groups who ‘strive to protect and promote human rights relating to the environment’.14 Forst (2016) acknowledges that defenders come from many different backgrounds and work in different ways. Some are lawyers or journalists, but many are ‘ordinary people living in remote villages, forests or mountains, who may not even be aware that they are acting as environmental human rights defenders.’15 In many cases, they are representatives of indigenous peoples and traditional communities whose lands and ways of life are threatened by large projects such as dams, logging, mining or oil extraction. What they all have in common is that they work to protect the environment on which a vast range of human rights depend. Forst (2016) further acknowledges that he makes use of the term environmental human rights defender to include a broad range of defenders and considers that the reason why defenders advocating for the environment are often characterized as ‘land and environmental rights defenders,’ ‘environmental rights defenders,’ or just ‘environmental activists’ is because land and environmental rights are interlinked and often inseparable. In year 2019, the Human Rights Council recognized the central role of EHRD in environmental protection and sustainable development.16

2.2From EHRD to Biosphere Defenders

While important progress has been made with the emergence of international law and policy regarding EHRD, we argue that these narratives around EHRD are not enough to appeal for their protection and a narrow understanding limits its potential to consider them agents of change in pathways towards just sustainability. We consider that this ‘mainstream’ EHRD narrative, produced and reproduced by international NGOs such as Global Witness, and the UN policies and law such as those that emanate from the UN General Assembly and UN Human Rights Council are important and needed to call people’s (and states in particular) attention.

Yet, we observe three problematic issues in this ‘mainstream’ EHRD narrative all of them interrelated and which aim to appeal to the need to protect environmental defenders: (a) stressing their vulnerability and portraying them as victims of violence, (b) in antagonism with a particular economic activity and (c) essentializing them as individual right-holders. We analyze each of these issues and while we acknowledge that they are important, we propose specific ways to complement them and visibilize EHRD positive contributions. Building on Ituarte-Lima (2023)17, we continue coining the concept of “Biosphere Defenders” to mark a difference in the mainstream concept of EHRD.

2.2.1From ‘Victims of Violence and in Need of Protection’ to ‘Agents of change in Need of Political Recognition’

Violence –including threats- accompanies ‘mainstream’ narratives on environmental defenders. As such, these actors are depicted as vulnerable and at risk of attacks and death.18 The association between environmental defenders and vulnerability is almost direct, as if embedded in the concept. This is obviously the case in many regions specially in the Global South, and we acknowledge the urgency in making a global call to pay attention to this.

Despite this, we also consider that it is important to acknowledge that vulnerability can be politically constructed and paying attention to only this might invisibilise the agency of environmental defenders - for instance –to mobilize resources for their cause or to make a sustainable use of their lands, waters or territories. We argue that if vulnerability and risk are represented as the only way to appeal to action (e.g., obligation of the states to protect), this might ultimately reinforce colonial attitudes: environmental defenders are in need of protection and only non-rural, non-indigenous people can protect them. This risks to reproduce a ‘white saviour’ attitude.19

Our proposed biosphere defenders concept decouples vulnerability from weakness and couples it with agency and solidarity.20 Because defenders are strong and successful in challenging the status quo is that they become vulnerable -not because they are inherently weak. The reason, for instance, why many women are especially vulnerable is not because they are feeble but because of their bold proposals for more equal gender relations as well as a more respectful relation with nature.21 See below cases studies in Section 4.

2.2.2From ‘Contrarian to Development’ to ‘Inspirations for just Sustainability Policy and Law’

Often defenders are portrayed as in opposition to one economic activity in particular (e.g., mining, biofuel, infrastructure) because such activity is destroying their natural environment or denying their access to natural resources. Sometimes, the problem is depicted as environmental defenders not having a say in the implementation of those activities, or communities not participating or giving free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) to economic projects that will modify their natural. Since these activities are promoted by nation-states in the name of ‘development’, in some countries environmental defenders are portrayed as ‘anti-development’, ‘anti-progress’, ‘anti-modernity’, or ‘enemies of the state’.22

It is not only the impact of a particular extractive activity or the distribution of benefits and burdens, but the system or development model that supports that activity, what some biosphere defenders oppose. A narrow view of defenders in environmental matters obscures what defenders support which includes distinct relational human and nature dynamics. Defenders challenge the status-quo and power relations. A positive defender’s narrative also opens possibilities of bringing a diversity of people together. For instance, scholars working with sustainability issues in the context of agriculture or water engineering may not see their role in tackling violence but would indeed see their role in co-creating multiple-evidence based solutions for positive social-ecological outcomes.

2.2.3From ‘Individual Right-Holder’ to Individual and Collective Right-holders Catalysing Just Pathways to Sustainability

Despite acknowledging the central role EHRDs play in sustainable development, we observe a tendency to frame EHRD only in relation to State’s human rights obligations to protect individual’s personal integrity and life, but little is discussed about the socio-ecological system they represent, advocate for and the collective they defend. We argue that by paying attention to the individual person under attack or killed, the mainstream narrative of environmental defender leaves aside who they represent, not only in terms of a community, but also in terms of collective’s worldviews and values. This becomes clear e.g. Front Line Defenders (2022)23 and Global Witness 202024 opening their reports by listing the names of those murdered during the year under study. By abstracting the individual from her or his environment, there is a risk of dispossessing EHRD from people’s particularities e.g. if they are female, young, or member of an indigenous people, and an opportunity is missed to see what the individual person is representing.

We consider that an intersectional approach embedded in the concept of biosphere defenders contributes to overcoming the individual/collective divide. Individuals do not operate in isolation hence the need to couple agency with solidarity between humans and with biosphere -humanity understood as part of the biosphere as above-mentioned. Michel Forst, UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention on access to information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters recognizes that environmental defenders have diverse backgrounds, cultures and belief systems and may not self-identify, or be identified by others, as EHRD.25 Forst calls for viewing the interconnectedness between individual defenders and their groups, organizations, communities. An analytical framework and empirical case studies on the rights and roles of biosphere defenders are needed to see the individual as part of the collective(s) which they form part and their role in societal change.

3Framework for Understanding Biosphere Defenders’ Rights and Roles in Just Sustainability Pathways (Defend-Biosphere)

The Biosphere Defenders Framework aims to be a tool to understand defender’s role in generating positive social-ecological outcomes. This framework is needed to systematically analyse defender’s contributions to the realization of the right to a healthy environment through activating open information, public participation and access to justice. The Defend-Biosphere framework consists of two main parts: first, we present the legal framework that backs-up the work of biosphere defenders. Then, we use the IPBES’ levers and leverage points to deepen the understanding of biosphere defenders’ role in just societal transformations. Finally, in our two case studies, we use the utility of this framework in understanding who biosphere defenders are and their role in just sustainability pathways.

For the purpose of this paper, we define biosphere defenders as those individuals and collectives who catalyze pathways for just sustainability. The definition of biosphere defenders includes right holders who advocate for “greening” human rights such as the rights to life and health, through their application to environmental issues26 and those who advocate using open information, public participation and access to justice for realizing the substantive elements of the right to a healthy environment such as healthy and sustainable produced food, healthy biodiversity and ecosystems, and non-toxic environment.27 Under this definition, biosphere defenders are also individuals and collectives who promote the stewardship of biodiversity and ecosystems irrespectively of nature’s contribution to people (e.g. through nature rights). Rather than seeing climate, biodiversity and water defenders in silos, we use the term “biosphere defenders” to encompass people using the law and other strategies to enact change, bringing together distinct bodies of literature on climate litigation28 and biodiversity litigation.29

3.1Biosphere Defenders’ Legal Basis

In this article, building on Ituarte-Lima (2023), we continue coining the concept of biosphere defenders. Even though this concept is not present in international law, we argue that the legal basis for biosphere defenders’ rights can be grounded in existing sources of international human rights law. The living instrument method of legal interpretation involves interpreting human rights treaties in the light of present-day conditions.30 The principles and instrument upon which rights of human rights defenders are recognised are rapidly developing through various legal instruments and jurisprudence by national, regional, and international courts. Therefore, rather than proposing a new subject of international human rights law, we propose to use existing instruments clarifying the rights to defend human rights in the understanding that is not a sum outcome of human rights plus environment. Instead, a progressive interpretation demands seeing humans as part of biosphere and hence it goes beyond summing two distinct entities.

3.1.1Universality and Interdependence of Biosphere Defender’s Rights

Even before the term ‘human rights defender’ was coined and incorporated in the Declaration on HRD, many people acted as biosphere defenders, reshaping gender roles, confronting colonialism, restoring ecological cycles, and advancing solidarity within a collective but also with other collectives they represent (e.g., Afro, youth, indigenous).The spirit of the Declaration on HRDs, interpreted based on its travaux preparatoire, is on human rights defenders and their rights informed by the principle of universality of human rights rather than a limited interpretation of individuals framed in the context of the principle of sovereign equality of States and non-interference in their internal affairs.31

The Declaration on HRDs has had a trickling effect: the Organization of American States, the Council of Europe, the European Union, and the African Commission on Human’s and People’s Rights have used this Declaration as a basis for further work in their respective regions.32 However, the first and only plurilateral treaty explicitly recognizing the rights of human rights defenders in environmental matters is the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean commonly known as Escazu Agreement (EA).33 While the State’s human rights obligations specifically mentioned in Article 9 (paragraph 2) concern rights sometimes framed as civil and political rights namely right to life, personal integrity, freedom of opinion and expression, peaceful assembly and association, and free movement, this first paragraph also mentions that “Each Party shall take adequate and effective measures to recognize, protect and promote all the rights of human rights defenders in environmental matters”. Based on the principle of pro persona (EA, Article 3 k), State’s obligations towards defenders should be constructed based on an interpretation covering the broadest spectrum of defender’s human rights. OHCHR notes that “when closely scrutinized, categories of rights such as “civil and political rights” or “economic, social and cultural rights” make little sense. For this reason, it is increasingly common to refer to civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights.” 34 For instance, education on environment and climate enables individuals and groups to participate in political activities and exercise their freedom of expression and opinion and advance the stewardship of biodiversity and ecosystems in an informed way.

Furthermore, States shall take the most favourable interpretation to advancing biosphere defender’s rights specified in EA, Article 9. Article 4 (parr 7) of the EA establishes that “no provision in the present Agreement shall limit a more favourable interpretation of rights and guarantees set forth, at present or in the future, in the legislation of a State Party or in any other international agreement to which a State is party”. Therefore, the broad spectrum of rights of defenders shall be used in interpreting biosphere defender’s right to a healthy environment and to sustainable development recognized in EA, Article 1. This interpretation should be done in convergence not only with civil and political rights and freedoms recognized in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)35 but also the rights recognized in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)36 , to which most Latin American and Caribbean countries are parties.

3.1.2Individual and Collective Dimensions of Full Spectrum of Biosphere Defender’s Rights

International human rights law recognizes that every person, irrespective of gender, age, ethnic, economic conditions has the right to what the IPBES conceptualises as a good quality of life.37 In its report presented to the UN Human Rights Council, Knox (2017) clarifies obligations concerning social-ecological systems: in order to protect human rights, States have a general obligation to protect ecosystems and biodiversity because biodiversity is necessary for ecosystem services that support the full enjoyment of a wide range of human rights, including the rights to life, health, food, water and culture.38, para 65. Rights of biosphere defenders encompass economic, social and cultural rights recognized in the ICESCR39 and a way to do so is being steward of biodiversity and ecosystems. For example, agrobiodiversity contributes to people’s good quality of life by providing varied and nutritious foods which are key for enjoyment of the right to adequate food (Article 11, ICESCR).

Like economic, social and cultural rights, defender’s civil and political rights recognized in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)40 also have individual and collective dimensions. For example, defender’s right of freedom of expression and opinion (Article 19, ICCPR) encompasses access to information held by State institutions and businesses but also the ‘right of voice’ including exchanging information that in turn enables informed and free participation in legal and policy processes. The 2023 thematic report by Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression and opinion, Irene Khan, calls for a paradigm shift by looking at sustainable development through the lens of freedom of expression.41 She argues that the promise of leaving no one behind will only be fulfilled when both access to information and the voices of human rights defenders, women, youth and others in disadvantage positions are heard and these groups of people can participate effectively.

Human rights treaties provide content to individual and collective dimensions of biosphere defender’s rights. Civil and political rights have value in themselves. Yet, interpreting civil and political rights in connection with economic, social, and cultural rights in line with the interdependency of human rights enables to visibilize the concrete ways in which biosphere defenders are not only protesting against something but also proposing economic, social and cultural alternatives, more attuned to healthy social-ecological systems.

3.1.3Defender’s Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment and Actions Towards a Healthy Biosphere

The civil, cultural, economic, political, and social rights are also interdependent on the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment (R2HE). The R2HE unites procedural and substantive elements and provides a useful umbrella category to delineating the content of biosphere defender’s rights.42 The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, David Boyd reaffirms that there is global agreement that human rights norms apply to a broad range of environmental issues, including biodiversity.43 Hence, biosphere defender’s right to a healthy environment shall be constructed not only limiting to procedural State’s obligations but also to substantive obligations of this right and the interactions of these two types of State’s obligations. This interpretation allows to put a spotlight not only in process but also in social-ecological substantive outcomes.

The recognition of the R2HE by the UN General Assembly in 202244 is an outcome of collective action from a diversity of groups of peoples since 1970 s. While there is not a global binding treaty recognizing the right to a healthy environment in general or of biosphere defender’s right to a healthy environment in particular, State obligations regarding this right can be derived from various sources of international public law including multilateral environmental agreements, international human rights law45 and regional treaties such as the EA above-mentioned. Like other human rights, State’s obligations towards biosphere defenders entail obligations to respect, protect and fulfil human rights. State’s obligations to fulfil biosphere defender’s rights, entail obligations that are relevant to addressing the structural obstacles that prevent the realization of human rights and this type of State obligation is particularly important to catalyze the virtuous spiral of sustainability.

3.1.4State’s Heightened Obligations Towards Certain Biosphere Defender’s Groups

International frameworks specifying the rights of particular groups are a source to make more precise the meaning of State’s general obligations towards individuals and collectives. Heightened State’s human rights obligations emerge towards people in vulnerable situations such as children, and people with disabilities. Below we refer to the human rights of specific groups which are relevant for our case studies in Section 5. As for rights of women biosphere defenders, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CEDAW (1979) recognizes civil and political rights as well as economic, social, and cultural rights in a single instrument. Based on Article 14, CEDAW, States parties to this treaty shall consider the particular problems faced by women defenders in rural context and their significant role in the non-monetized and monetized economy. Different forms of participation are specified in Article 14 which range from participating in all community activities (parr f), to participating in the elaboration and implementation of development planning at all levels (parr a) and organizing self-help groups and cooperatives for equal access to economic opportunities through employment or self-employment (parr e).46 The UN General Assembly resolution focusing on women human rights defenders47 serves to specify CEDAW’s general State’s obligation in the context of women biosphere defenders. Like CEDAW, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women (Maputo Protocol)48, recognizes a wide range of environmental related women’s rights such as the right to live in an acceptable living conditions in a healthy environment (Article 16).49 The Maputo Protocol also reaffirms the principle of gender equality enshrined in the Constitutive Act of the African Union as well as other principles including the principles of solidarity, democracy, freedom and peace. The EA specifically refers to State obligations to establish conditions that are adapted to gender characteristics of the public and that are favourable to public participation in environmental decision-making processes (EA, Article 7, paragraph 10).

As for rural biosphere defenders, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (2018), Article 18 serve to specify the rights of collectives who engage in actions for safeguarding the health of rural ecosystems as well as the conservation and sustainable sustainable use of biodiversity. For example, exchanging seeds between communities serves to guard agrobiodiversity including seeds’ genetic diversity. The UN Human Rights Council (2023) has called upon all States to conserve and sustainable manage biodiversity and ecosystems applying a human rights-based approach that emphasizes participation and accountability; and that promotes a safe and enabling environment in which environmental human right defenders working on biodiversity can operate free from threats, hindrance and insecurity.50 Among these biosphere defenders are rural communities and indigenous peoples including women, men, non-binary people, children living in these communities and their allies.

In the case of indigenous peoples as biosphere defenders, the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples International Labour Organization Convention51 (ILO Convention No 169) and the Universal Declaration of the Rights of indigenous people specify the individual and collective dimensions of the indigenous peoples’ defender's rights as well as also indigenous peoples as collective subjects of rights. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), Article 29 serves to specify indigenous peoples’ rights and corresponding obligations of State concerning a healthy environment. At the EA’s Defenders Forum, Darío Mejia, President of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues noted that indigenous peoples as collective subjects of rights is often confused with specifying the collective dimension of indigenous peoples’ rights.52

3.2Visibilising Biosphere Defenders through Leverage Points and Levers Towards just Sustainability

Complementary to the biosphere defenders’ legal basis, this second part of the Defend-Biosphere framework consists on unpacking the role of biosphere defenders in advancing key priority issues (leverage points) as well as multiactor governance approaches (levers) for advancing these sustainability pathways building on Chan et al. 2020 above-mentioned.

3.2.1Leverage Points

1. Embrace diverse visions of a good life. Current natural resource overexploitation equals development with economic growth and a modern society with that of higher levels of consumption. However, other understandings of a good life exist (e.g., buen vivir) ontologically position humans in a more equal relation to nature, understanding living well in a more holistic way. Biosphere defenders show how alternative understandings of human-nature relations exist where non-material aspects of wellbeing are central such as solidarity, recognition, trust, and care.

2. Rethink and change total consumption and waste considering the inequalities between rich economies and poor ones and between middle-upper income groups and people in poverty situations. While those whose levels of consumption need to be risen, there is a need to transform how we consume and how waste is managed. Biosphere defenders showcase different socio-ecological models to relate with nature and the economy that are not based on consumism and/or to minimize waste.

3. Recognize and promote latent values of responsibility and solidarity is about changing how we interact with nature (and among us) based on values and attitudes of stewardship and care. Biosphere defenders promote relations among people and with nature (caring, safeguarding, restoring, etc.) that value nature because it mediates those social relations and not only because of its economic value.

4. Address and reduce inequalities to start up sustainable pathways at different scales. Biosphere defenders shows how unequal distribution of benefits and burdens, unfair recognition and/or exclusion of certain knowledges and socio-ecological relations are detriment to sustainable pathways while at the same time they show ways towards their transformation.

5. Promote just and inclusive conservation. Nature conservation and restoration should be just and inclusive, not to the detriment of some groups in society. Biosphere defenders, many of them members of local communities impacted by conservation policies that displace them, demand to be part of the decision-making process in such policies. At the same time, they contextualize their claims from a multi-scale approach advocating for connecting conservation in one place in a larger regional context and promote conservation with sustainability practices.

6. Consider how externalities and telecouplings impact sustainability pathways. Distant connections between two seemingly unconnected events need to be better acknowledged (e.g., increases in conservation areas in one place may trigger overexploitation in another). Biosphere defenders show how economic and political decisions sometimes made in distant places and based on particular understandings of development (e.g., extractivism based on economic growth) may impact local communities whose livelihoods depend directly on nature.

7. Reformulate the role of innovation and investment in sustainability to address how unsustainable practices are reproduced. There is a need to rethink how innovation in society and technology takes place and the externalities of innovation and investment to reverse ecosystem’s degradation. Biosphere defenders promote socio-ecological innovation uniting their traditional knowledge with new technologies. At the same time, biosphere defenders show how key international financial organizations continue to support unsustainable economic projects.

8. Generate and share education and knowledge for transformative change towards sustainability. Biosphere defenders showcase how local and traditional knowledge based on solidarity and care towards nature and human relations are central for sustainability pathways (e.g., repairing community relations through nature restoration).

3.2.2Levers

A. Incentives and mobilization of capacities. Subsidies, incentive programmes, and other types of financial commitments should be aligned to just sustainability pathways. The role of biosphere defenders has been central in this regard as they have critically pointed financial mechanisms that are detrimental to sustainability (e.g. as in the case of unsustainable extractives practices supported by international banks) as well as mobilised political, economic, cultural, socio-ecological capacities at local level.

B. Coordination across sectors and jurisdictions. There is a need to recognize the importance of integration across administrative boundaries and regions. Biosphere defenders in conjunction with other stakeholders have been putting forward projects that address policy coherence and further allow integration of environmental goals into institutions at different levels of governance (local, provincial, federal, regional and international). Cooperation among diverse governance bodies is central to sustainability pathways.

C. Pre-emptive action. Addressing emerging risks proactively, even before establishing specific proof of impact, is necessary to initiate sustainable pathways. Biosphere defenders have been at the forefront of such practice when denouncing large-scale projects bringing environmental degradation. Proactive and precautionary approaches are essential due to the slow responses of nature, but also because there is often a significant time lag between scientific attention and consensus on causality. In many cases, traditional and local knowledge understands ecological dynamics better than those whose livelihoods do not depend directly on nature and therefore biosphere defenders’ voices are central.

D. Adaptive decision-making. Policies, programs, and initiatives assuming linear ecosystem dynamics may lead to surprises, while those designed to be robust, adaptive, and resilient can be more effective in the long term. Biosphere defenders are showing how relevant it is to invest in the restoration and enhancement of ecosystems and create projects and programme adapted to ecological cycles instead of the other way around.

E. Create, reform, and implement laws for R2HE outcomes. Consistent creation, reformation and implementation of laws, particularly those governing rights and responsibilities, is crucial for protecting nature and human well-being. Strengthening international and domestic environmental laws and policies, along with better implementation and enforcement, is vital. Biosphere defenders have been central to mobilize policy and law to realize their rights, but also to advocate for the reform or development of new laws and regulations when it is insufficient to apply the existing ones.

4Piloting the Biosphere Defenders’ Concept and Defend-Biosphere Framework in Case Studies in Colombia and Argentina

In this section, we present two cases from South America where biosphere defenders play a central role in the construction of just sustainability using the Biosphere-Defenders Framework for the analysis.

4.1Women as Biosphere Defenders Leading the Resistance Towards Harmful Socio-Ecological Impacts of Coal Mining in La Guajira, Colombia –The Case of Fuerza de Mujeres Wayuu

In this case study, we zoom into biosphere defenders’ collective action, specifically how they use open information, public participation and access justice (procedural elements of the R2HE) to advance the realization of the non-toxic environment and healthy ecosystems and biodiversity elements of the R2HE (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Defend-Biosphere framework.

4.1.1Biosphere Defender’s Civil, Political, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Affected by Social-Ecological Dynamics

The department of La Guajira was declared in a state of humanitarian crisis in July 2023 after years of paramilitary actions, corruption and food and water shortages that have led to human rights violations53, particularly of the rights of the Wayúu –an indigenous people living in this semi-desertic region of Colombia. La Guajira also hosts one of the world’s largest open pit coal mines. Glencore owns Cerrejón and this area is also seen as the epicentre for the energy transition that Colombia is facing as it seeks to gradually shift from fossil fuels to renewables. Both the mining operations but also e.g., plans for wind parks have faced local resistance due to negative socio-ecological impacts especially on the indigenous peoples, afro and peasant communities living close to the initiatives.54 At the forefront of these struggles have often been the women led organisation Sutsüin Jieyuu Wayúu - Fuerza de Mujeres Wayúu (FMW), which translates to The Wayuu Women Force.55

4.1.2Individual and Collective Dimensions of Biosphere Defender’s Rights

FMW has operated since 2006. A big part of its work has been to shed light on the environmental, social and cultural impacts of Cerrejón and related human right violations not only on individuals but also to the Wayúu as a collective. Colombia has the highest record of assassinations of environmental defenders, with over a third of killings globally happening in Colombia in 2022.56 The leaders, both women and men, of FMW are also constantly exposed to danger and face intimidations and death threats due to their activism.57 The organisation actively trains women to advocate for their rights and aims to pass on to future generations and broader Wayúu community its experiences and knowledge of activism and resistance (Leverage 8).58

4.1.3Biosphere Defender’s R2HE: Zooming in on how Clean Water, Food and Non-toxic Environment Depend on Access to Justice

One of the most scrutinised cases of environmental conflict in La Guajira is related to the Bruno stream. In 2014, the national environmental licencing authority (ANLA) approved the plan of Cerrejón to divert a section of the Bruno stream to expand the coal extraction from the pit El Puente. This was in a time when the Colombian government vigorously promoted mining and foreign investment as part of their national development plan, often at the expense of proper environmental impact assessments and community consultations.59 The diversion plan was instantly met with resistance (Lever C). Marches, press releases, social media posts and other statements mobilised by FMW and community members vocalised the importance of the river for not only the instrumental values of the river, but the cultural and spiritual values that the river and water, the Pulowi (female water spirit), hold for the Wayúu and that are affected when water becomes scarce60 (Leverage 3). In 2017, the Constitutional Court of Colombia ruled in favour of the local communities, among them FMW leaders, stating that the diversion would violate their fundamental rights to water, health and food sovereignty.61

The court determined that several uncertainties regarding the social and environmental impacts of the project remain and therefore the diversion should be suspended. An Interinstitutional Working Group (IWG) with governmental and non-governmental actors was created to assess how Cerrejón should realise the further studies and then recommended actions to ensure the environmental viability of the project. The Bruno case was also brought to the attention of the High Commissioner of the UN by FMW and other organisations. The Wayuu and FMW have received support and made alliances with both local and international organisations supporting the fight for their rights, including help to demonstrate that some of the environmental impact claims of Cerrejón are faulty.62 The case thus reveals how these rural communities can harness solidarity from the local to the global to strengthen their resistance (Lever B).

The case of Bruno illustrates how FMW have highlighted several levers and priority issues in their advocacy for the realization of human rights and just transformations. Most notably, the SU-698 can be seen as a win for local communities as it ordered Cerrejón to return Bruno back to its natural cause. However, the stream remains diverted to date as different entities continue to argue about the real impacts of the diversion and Glencore has sued the Colombian state as it argues that it will suffer financial losses due to the demands presented.63 Using legal strategies to seek just sustainability may thus be tricky if implementation of law is lacking and policy priorities are incoherent. Nonetheless, the legal struggles have given visibility to the case, leading to further support in forms of an Amicus Curiae by ABColombia.64 The legal strategies can be seen as a coordinated action across sectors and jurisdictions as they managed to bring together the IWG and also to illustrate, although not corrected to date, some of the major flaws in the environmental governance of Colombia (Lever B, E). However, the IWG did not prove to be unproblematic and the Wayúu walked out of the working group after disappointment towards lack of implementation of actions required in SU-698.

The participation by FMW in the defence of Bruno unleashes relational values, noting that water is what maintains the relations between humans and Mother Earth. Through their ontological stance ‘Wayúu women safeguard their communities against colonial power structures such as green colonialism’.65 Recently, the first woman Wayuu senator Marta Peralta’s bill to declare Rio Rancheria and its affluents, including Bruno, as subjects of rights for their protection, conservation, preservation and restoration was approved in the first debate in the senate66. The bill states the formation of a Commission of Guardians of the River composed of government and local community actors who are responsible for protecting the rights of the river (Leverage 5). The objective is to decontaminate the river and its surroundings and promote the peaceful and balanced enjoyment of the river (Lever D). The bill notes as its precedent similar cases of jurisprudence in Colombia, where rivers, moors and other ecosystems have been declared holders of rights. This Rights of Nature approach may be the next legislative strategy that combines relational values in seeking justice and socio-ecological sustainability for Bruno (Leverage 1, 3).

Lastly, it should be noted that the fight is not primarily against something, but for the future of the communities that will live in La Guajira after all else (Leverage 6). Despite threats and violence, Wayuu women continue to fiercely translate their anger into action and power and strive to overcome silencing practices for the sake of future generations 43. Therefore, highlighting the agency and solidarity instead of the victimization of FMW highlights the fierce power they possess to push for just sustainability transformations.

4.2Constructing Agroecology in Northern Argentina: The Role of the Ferias Francas (Tax exempt Local Farmers’ Markets) in Creating Pathways Towards just Sustainability

In this case study, we delve into how biosphere defenders catalyse open information including the production and recreation of local knowledge, and public participation (procedural elements of the R2HE) in a way that contributes to the construction of localised agrifood systems that are inclusive and works towards a key element of R2HE: sustainable produced and consumed food. We show instance in which the State -at different levels- has been seeking to commit to its obligations to fulfil biosphere defender's right to a healthy environment.

4.2.1Fulfilling the Right to a Healthy Environment: Sustainable Localised Food Systems

In his report to the Human Rights Council in 2010 the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier De Schutter, identified “agroecology as a mode of agricultural development which not only shows strong conceptual connections with the right to food, but has proven results for fast progress in the concretization of this human right for many vulnerable groups in various countries and environments”.67

The negative socio-ecological impacts of industrial agriculture and husbandry has been widely shown.68 Recently, connections have been made between human rights violations, industrial food systems, and the role of agroecology in a Just Transition: “[t]here are multiple problems with the way food is produced, processed, distributed, prepared, consumed, and disposed of in industrial food systems. Their environmental consequences amplify pre-existing inequalities and contribute to human rights violations. For the needed transformation of food systems, which is equitable, just, and sustainable, agroecology plays a crucial role”.69

Agroecology is a type of agricultural system that is embedded in local ecologies. It is based on local knowledges produced by people whose livelihoods depend directly on their natural environment (e.g., indigenous communities, peasants, fishers, pastoralists). It is also characterized by short value chains, localized production-consumption, organic production minimizing waste and energy and being relatively independent from supply and inputs markets (usually, non-local). This translates into organic, fresh, culturally appropriate food, which does not pollute the environment.

4.2.2Seeking to Fulfil the Right to Food and the Environment Amidst Structural Challenges

While Argentina is known to be one of the major industrial agriculture producers and consumers of agrochemicals, it is also the case that the country’s organic production is expanding, particularly after the Covid-19 pandemic.70 The ferias francas (tax-exempt farmer markets) are a paradigmatic example of family farming based on agroecological principles. These ferias are direct spaces of food commercialisation (‘farm to table’) that can be found all over the country.71 They are well-known institutions that have garnered the attention of public law and policy makers and scholars in the field of family farming for more than twenty years.72

The first market was created in 1995 in the province of Misiones in the context of a profound crisis resulted from the implementation of structural adjustment programmes and ecological degradation. The deregulation of the provincial markets was pushing farmers out of business and with the need to reconvert their production.73 The national and provincial governments introduced different support mechanisms, namely rural development programmes: micro-credits, technological transfer, capacity building and organisational support among other strategies (Lever A; Leverage 7, 8) with different target populations. The aim was to prevent rural-urban migration and increase the deteriorating quality of life of family farmers by assisting them to continue living and producing in their farms (e.g., introducing value-added by home-processing food, increasing independence of farmers from inputs markets, restoring ecological productivity, and/or creating new local channels of direct commercialisation). Environmental considerations were mainstreamed in this new development agenda as the native forest (local ecosystem) was incorporated as a key element in family farming planning (Leverage 1 and 3).

The first feria franca was inaugurated in the locality of Oberá as the result of the cooperation among farmers, local civil society, and the municipal government (Lever B). Since then, around 70 local markets have been created in Misiones currently involving around 3000 families.74 The markets have consolidated new rural-urban linkages and at the same time facilitated women and young farmers’ participation in public life, among other relevant socio-economic, political, and ecological issues in different scales (from the farms to the provincial parliament).

4.2.3Women’s Biosphere Defenders: Realising Women’s Rights

The ferias francas gather farmers to directly sell their food surplus production (vegetables, dairy produce, eggs, chicken, pork, bakery, jams, and other home industrialization products) between two and three times a week in many localities around the province. The participation of women in these markets has proven to be decisive. Certainly, women’s role in the agrarian economy in Misiones has always been linked to food production for domestic consumption75. Their work in horticulture, small animal husbandry and food preparation have long been vital to provision of food for the family.

Since food produce is produced in rural areas, women and men move to nearest towns or cities to sell their products. Historically, male farmers have enjoyed the ‘right to urban space’ as men were normally in charge of the commercialisation of industrial crops from their farms (e.g., tobacco, mate, tea, and timber). With the creation of ferias francas, women increased their opportunities to access urban spaces. This has been highly appreciated by those women participating in these spaces of commercialisation despite in many cases increasing the burden for female members since they had to work even more at the farm to increase farm production (vegetable volumes, homemade bakery, sausages, jams, and dairy products), travel to the town to sell, all while taking care of children and husbands.76

Farmers directly selling their produce highly value their new identity as feriantes (people that commercialise in this kind of markets) because the market is a social space for meeting and socializing with other people. They also find that this kind of project reintroduces the role of women in the urban society as well as in the family, since now they are providers not only of food but also of a regular income (Leverage 4).

4.2.4Fulfilling the R2HE: From Accessing Information to Creating New Legislation

Farmers’ organizations, cooperatives, rural development programmes, civil society organisations, schools, among others support the organisation of the production and commercialisation in these collective spaces. Not only have the national and provincial governments granted financial support to informal grass-roots organizations to organize the commercial aspect of agriculture, but they have also assisted through information and capacity building in food production and agroecology (e.g., facilitating access to seeds have been central in the support of ferias francas) (Lever A, D).

The local governments supported ferias francas by creating the legislative and institutional regulations which allowed a feria (market) to be tax-exempt (Lever E). This means that the markets are exempt from certain local taxes and therefore are able to sell fresh and good quality food with lower prices, allowing urban population to access better quality food (Leverage 2). In addition, since they are installed in public spaces, they need to be granted permission by the local government, who also must do the bromatological77 control of the food (e.g., when home industrialised). In this way, the municipalities assume a role usually given to the market so as to leverage small-scale farmers to participate in the local economy (Leverage 4, 7).

The markets enhance food security in rural, peri-urban, and urban communities because farmers produce and consume their own food, selling the surplus in nearby towns. This has also increase local and regional food sovereignty since food is supplied to the provincial market decreasing this way the dependency of food produced from other provinces. During crisis times (e.g., 2008 agricultural blockage, 2020 covid) the local production and supply of food has proven to be central for accessing food.

Scaling up this, the provincial state has created a legislative framework central to sustain and promote a development model based on family farming, agroecology, and ferias francas (Lever E). More than ten laws were enacted to further support this model. In 2010, the provincial law III-10 for the Development and Promotion of Ferias Francas and Zonal Market Concentrator of the Province was passed. In 2015, the provincial law VIII-69 of promotion of family farming stablished that “the province of Misiones adopts a productive, economic, social and environmental development model based on family farming”78 and the provincial law VIII-68 that Promotes Agroecology was enacted. In the latter, the second article clearly specifies the centrality of environmental care for the production, consumption, and commercialization of agriculture in the province.

4.2.5The Future of Agroecological Localised Food Systems: Creating Spaces of Hope

Farmers’ local markets, ferias francas, are socio-economic, cultural, and political spaces that emerged as a political decision of finding ‘alternatives’ to highly polluting development based on monocultures and the internationalisation of the local industrial agriculture. Agroecology, as an alternative development model79 has promoted relational values -urban and rural- between peoples and their natural environment which are central for sustainability.

Currently, agroecological production coexist in Misiones with industrial agriculture based on tobacco and pine plantation and an area-based nature conservation. While dismantling industrial agriculture - highly contaminant of soil and water- may seem a utopia, this case study reveals how women and men from the countryside have proven that it is possible to create new social relations based on solidarity and local production in tune with local ecologies and less dependent on agrochemicals (Leverage 3).

5Conclusion

We find that uniting international human rights law with the IPBES’ Global Assessment’s levers and leverage points for sustainability pathways was useful for addressing our research questions in this paper. First, the discussion on the rationale behind the biosphere defender’s concept (Section 2) and Defend-Biosphere framework (Section 3) and the case studies (Section 4) contributes to clarify who biosphere defenders are, their human rights and the associated State’s obligations based in various sources of international human rights law. In contrast to the mainstream narrative on Environmental Human Rights Defenders (EHRD), we find that it is not sufficient to place a spotlight only on civil and political rights, it is equally important to prioritize the respect, protect and fulfilment of biosphere defender’s economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) as well as the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment (R2HE). Through legal analysis of various sources of international human rights law, we reveal that a significant problem is a restricted interpretation of defender’s rights by the mainstream narrative on EHRD rather than the absence of sources of law for a more progressive interpretation to the meaning of defender’s rights in the context of the biosphere.

If the root causes of unsustainable development are to be addressed, then State obligations concerning ESCR and the right to a healthy environment need to be equally at the center place. While a sense of urgency to reacting to the killings, threats and intimidations to biosphere defender’s violations is often placed as an argument to focus on civil and political rights of defenders, unless an equal focus is placed in preventing violations, there is a risk to be stuck in a vicious spiral of violence rather than catalyzing a virtuous spiral of sustainability. Interpreting rights of biosphere defenders covering the broad spectrum of rights is a way to implement State’s obligations to prevent attacks, threats or intimidations in line with the preventive principle and the principle of non-regression, principle of progressive realization. If there is an enabling environment for biosphere defenders to exercise their right to a healthy environment as well as their economic, social and cultural rights then they can focus their time and energy in constructing sustainability pathways rather than being forced to defend themselves from attacks to their physical integrity, and from the abuse of the law in the form of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs). Prevention of violations of the rights of biosphere defenders is also an efficient way of using public resources. If effective measures are in place to prevent attacks, threats and criminalization towards biosphere defenders, resources needed in investigating and punishing decrease and more public resources can be invested in supporting biosphere defender’s positive contributions.

Second, the Defend-Biosphere framework (Section 3) and the case studies (Section 4) show the multifaceted role that biosphere defenders have in levers and leverage points for just sustainability transformations. Given the diversity of activities that biosphere defenders engage from the local to the global scales, and the diversity of contexts where they operate (e.g. in the rural and urban interface in the case study in Argentina and a semi-desertic area historically inhabited by the Wayú indigenous people in the case study in Colombia), the precise constellation of people acting as biosphere defenders in the case studies should not be viewed as “typical”. Rather, what the Defend-Biosphere framework developed in this paper has allowed is a more in-depth understanding of the wide range of people who act as biosphere defenders and the multidimensional role that they play in pathways for sustainability. It is therefore a useful framework for unpacking who defenders are and how they individually and collectively contribute to systemic change- rather than only framing defenders as victims of threats and attacks. Using the Defend-Biosphere Framework allows us to show how different groups face obstacles to the realization of their rights but also how they are using their capabilities to steward the biosphere. It helps understand the fundamental role of environmental defenders towards sustainability pathways: mobilising a diverse range of existing capabilities, building new capacities, coordinating among different groups at different levels of governance, creating new legal frameworks, fostering new interpretations of existing law, catalysing the creation of new laws, demanding the State to implement already existing laws and regulations, or demanding new ones when the existing ones are not fit for purpose.

As for the case study in Colombia, we find that the approach of the Wayúu women in defending the Bruno stream embodies what it is to be a biosphere defender by interweaving people and nature rather than claiming the right to exploit nature. The leverage and levers harnessed for the protection of Bruno stream illustrate a course of action deeply dependent on collective agency, rather than only highlighting individual vulnerability. This agency has a bottom-up nature: local people use diverse strategies such as building networks and collaboration to attract wider attention of the impacts and telecouplings of extractive activities that mainly serve people and business outside Colombia. The declaration of La Guajira in humanitarian crisis and the passing of the bill to secure rights of River Rancheria can be seen as an indication of a political momentum for fundamental transformations towards just sustainability in which organisations such as FMW have a leading role. The capacities of Wayúu women to advocate for their rights against the generally prevailing political backdrop that favours and protects international investments speaks of the strength of Wayúu values and a more long-sighted perspective on achieving socio-ecological objectives. Walking out of the IWG, expressing disappointment towards implementation of environmental legislations and turning to alternative and novel ways to advocate for the local communities’ R2HE shows that the Wayúu are resolute to seek strategies that are true to their values. Seeking sustainability on their terms, based on their knowledge, illustrates that the Wayúu women are active agents of change.

In terms of the case study in Argentina, we categorize as biosphere defenders those rural individuals and collectives catalysing the ferias francas and the laws and policies that enable their continued existence. Since mid-1900 s, local actors in province Misiones have been clearly working towards sustainability and human rights when creating economic, political, cultural, and ecological relationships that restore nature and feed people without depleting the resource base. This has been slowly crystalised in legislation and institutions to support the continuity in time of this model that emerge in a critical period of time. While this is highly relevant to transit to sustainability, equally important has been the institutionalization of different mechanisms for agroecological certification that recognize in the market the role played by farmers in caring for the environment and health. Evidence derived from the case study reveals that biosphere defender’s access to information from national and provincial governments about food production and environmental pollution is important. Yet, in line with the “right of voice” mentioned in section 3, family farmers generating and sharing information with other groups is also vital for the realisation of biosphere defender’s R2HE.

The insights of the case studies reveal how both State’s positive and negative human rights obligations derived from a broad range of rights are key for generating just sustainable pathways. State’s negative obligations such as abstaining from interfering in grassroot organizations or not repressing public peaceful demonstration are important. At the same time, State positive obligations from exempting local markets from certain taxes, to granting permissions to utilize public spaces, and conducting food safety controls are also relevant. As for the R2HE, instead of using the common term of access to information as a procedural element of the R2HE, we use the term open information. The open information and public participation elements of the R2HE are exercised individually and collectively by grassroot organizations. Biosphere defenders’ freedom of association, normally framed as a civil right, is interdependent to the enjoyment of R2HE of other people. For example, farmers’ participation in local market enables rural and urban population to consume healthy produced food. The cases also show how the interdependency of civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights is vital for biosphere defender advancing the realization of the right to a clean, healthy environment and sustainable environment for all. Furthermore, the lived reality of people is not fragmented into climate change law, biodiversity law and water law. The term “biosphere” covering the foundations and interactions of life on Earth is well suited to capture the relational complexities in which biosphere defenders operate and contributes to bridging the fragmentation between different branches of law that are relevant for Earth systems law and governance.

The findings of this article and the Defend-Biosphere Framework developed in this paper are of particular relevance to the implementation of the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, the Escazu Agreement on access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, the Aarhus Convention on access to information, public participation and access to justice in environmental matters. It is also relevant for Montreal-Kunming Global Biodiversity Framework in particular Target 22 (access to information, participation, access to justice and environmental defenders) and Target 23 (gender equality).

Acknowledgments

This research was partly funded through the 2020-2021 Biodiversa and Water JPI joint call for research projects, under the BiodivRestore ERA-NET Cofund (GA N◦101003777), with the EU and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, and Research Council of Finland as part of the “Protecting Biodiversity through Regulating Trade and Business Relation” project (BIOTRADE). It was also funded by the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (FORMAS), as part of the project Environmental Human Rights Defenders – Change Agents at the Crossroads of Climate change, Biodiversity and Cultural Conservation (project number 2022-697 01684). C. Ituarte-Lima is part of both of these projects; A. Nardi of the Formas funded project and L. Varumo of the BIOTRADE project. The authors are also grateful to the members of Fuerza Mujeres Wayuu in Colombia and members of the feria francas in Argentina for sharing their experiences. The authors would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Carlos Pardo in fieldwork in La Guajira, Colombia. The article also benefited from insights from workshops of the Prevention Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice at New York University Law School; a special thanks to Pooven Moodley who coordinates the human rights and environment work stream of this Prevention Project and to Pablo de Greiff who directs it.

Notes

1 Diaz et al. (eds) (2019), IPBES Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science, Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn: Germany.

2 Ibid.

3 Leach M. et al. (2018), ‘Equity and Sustainability in the Anthropocene: A Social–Ecological Systems Perspective on Their Intertwined Futures’ 1:3 Global Sustainability, 1–13, Patterson, J. et al. (2017) ‘Exploring the Governance and Politics of Transformations Towards Sustainability’ 24 Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, pp. 1-16.

4 OHCHR (2019), Full List of UN Experts at news ‘Failing to Protect Biodiversity Can Be A Human Rights Violation –UN experts’ (25 June 2019) available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID.html. (accessed on 10 October, 2023)

5 Ibid.

6 UNGA (2020), ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment’ (15 July 2020) UN Doc A/75/161. In this thematic report, Boyd refers to human rights in general, rather than human rights defenders specifically.

7 Mclachlan, C. (2005) ‘The Principle of Systemic Integration and Article 31(3) (c) of the Vienna Convention’ 54 International and Comparative Law Quarterly, pp. 279–320.

8 Diaz et al. (eds) (2019), IPBES Summary For Policymakers of The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity And Ecosystem Services of The Intergovernmental Science. Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany.

9 Chan, K.M.A. et al. (2020), ‘Levers and Leverage Points for Pathways to Sustainability’ 2:3 People and Nature pp. 693–717.

10 Ibid, p. 694

11 UNO (1999), United Nations Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (8 March 1999) A/RES/53/144; available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/265855?ln=en.html (accessed on 10 October, 2023)

12 UNO (n/d), Human Rights Defenders: Protecting the Right to Defend Rights, Fact Sheet #29; available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/FactSheet29en.pdf (accessed on 10 October, 2023)

13 Knox, J.H. (2015), ‘Human Rights, Environmental Protection, and the Sustainable Development Goals’ 24 Washingt. Int. Law J., pp. 517–536

14 Knox, J. (2017), Environmental Human Rights Defenders: A Global Crisis. Policy Brief (February, 2017) available at: https://www.universal-rights.org/urg-policy-reports/environmental-human-rights-defenders-ehrds-risking-today-tomorrow-2.html (accessed on 12 October, 2023)

15 Forst, M (2016), Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, para. 7 and 8 (3 August 2016) A/71/281; available at https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/840291?ln=en.html (accessed on 12 October, 2023)

16 UNHRC (2019), Recognizing the Contribution of Environmental Human Rights Defenders to the Enjoyment of Human Rights, Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development. (2 April 2019) A/HRC/RES/40/11; available at: https://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/RES/40/11.pdf (accessed on 12 October, 2023)

17 Ituarte-Lima, C. (2023), Biosphere Defenders Leveraging the Human Right to Healthy Environment for Transformative Change, 53:2-3 Environmental Policy and Law, pp.139-151

18 Le Billon, P., and Lujala, P. (2020), Environmental and Land Defenders: Global Patterns and Determinants of Repression, Global Environmental Change, p.65 (February 2020); Global Witness (2020), Defending tomorrow (July 29, 2020); available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/defending-tomorrow.pdf (accessed on 12 October, 2023)

19 Murphy. C. (2023), What Is White Savior Complex and Why Is It Harmful? Health (17 August, 2023); available at: https://www.health.com/mind-body/health-diversity-inclusion/white-savior-complex.html (accessed on 12 October, 2023)

20 See more on coupling vulnerability with agency and solidarity in Ituarte-Lima (forthcoming) ‘International Lawmaking: Women Shaping Principles and Solidarity’ in Ebbesson, J. and Langlet, D. “International Environmental Law in Perspective –Stockholm+50” Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

21 Ibid,

22 For instance, Global Witness questions this narrative in Global Witness (2019) Enemies of the State? Available at https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/enemies-state.html (accessed on 12 October, 2023)

23 Front Line Defenders (2022), Global Analysis 2022; (4 April, 2023) available at: https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/sites/default/files/1535_fld_ga23_web.pdf (accessed on 15 October, 2023)

24 Global Witness (2020), Defending Tomorrow (July 29, 2020); available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/defending-tomorrow.html (accessed on 15 October, 2023)

25 Forst, M. (2022), UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders Presents His Vision for Mandate to Ensure Protection under The Aarhus Convention; available at: https://unece.org/climate-change/press/un-special-rapporteur-environmental-defenders-presents-his-vision-mandate.html (accessed on 15 October, 2023)

26 Knox, J. (2020), Constructing the Human Right to a Healthy Environment, 16:1 Annual Review of Law and Social Science, pp. 79-95

27 Boyd, D. (2020), ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, UN Doc A/75/161 (15 July 2020).

28 Savaresi, A. et al (2019) Climate Change Litigation and Human Rights: Pushing the Boundaries, 9:3, Climate Law, pp. 244-262.

29 Futhazar, G., Maljean-Dubois, S., Razzaque, J. (2022) Biodiversity Litigation: Review of Trends and Challenges in Futhazar, G., Maljean-Dubois, S., Razzaque, J. (eds), Biodiversity Litigation, London, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 359-400

30 Letsas, G. (2012), The ECHR as a Living Instrument: Its Meaning and its Legitimacy, SSRN: available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2021836.pdf (accessed on 15 October, 2023)

31 Koula, A.C. (2019) ‘The UN Definition Of Human Rights Defenders: Alternative Interpretative Approaches’ 5:1 Queen Mary Human Rights Law Review, pp. 1-20.

32 Ibid,

33 Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, adopted in Escazú, Costa Rica (4 March 2018) LC/PUB.2018/8; available at: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/43583/1/S1800428_en.pdf (accessed on 16 October, 2023)

34 OHCHR (n/d), ‘Key concepts on ESCRs - Are Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Fundamentally Different From Civil and Political Rights?’; available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/human-rights/economic-social-cultural-rights/escr-vs-civil-political-rights.html (accessed on 16 October, 2023)

35 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, into force 23 March 1976, 999 UNTS 171

36 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 16 December 1966, into force 3 January 1976, 993 UNTS 3