UNFCCC: A Feminist Perspective

Abstract

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was the only multilateral environmental agreement to emerge from the Earth Summit in 1992 which did not include any references to gender. Recognition of gender within the UNFCCC has been exceedingly slow and largely tokenistic with a focus on ensuring ‘gender balance’ within UNFCCC meetings and processes. This article explores the emergence of gender language within the UNFCCC by reflecting upon: where we have come from; where we are now; and where we are going with respect with gender. While there was very little progress in the early days of the UNFCCC, this article shows that from 2001 onwards there have been a series of small gains, which will be explained and critique. Much work remains to be done with this paper suggesting some concrete steps such as hosting a Gender COP, ensuring financing for National Climate Change Gender Focal Points and embedding gender meaningfully within existing climate finance processes. In recommending future actions, the paper draws on insights from the Pacific and Australian experience.

1Introduction

Climate governance within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) started thirty years ago with a focus upon mitigation and the associated international legal issues of determining responsibility and liability for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.1 The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 reflects the knowledges and perspectives valued by the regime at that time, namely biophysical knowledge and economic rationalism. As such, the early development of the UNFCCC was largely influenced by a narrow set of voices and perspectives which prioritised measuring and reporting the volume of emissions in the atmosphere and calculating the costs associated with reducing those emissions. This problematisation of climate change meant that many knowledges, voices and perspectives were side-lined within early UNFCCC instruments and decisions.2 As Sherilyn McGregor rhetorically remarked:

‘Does it matter that the definition of climate change as an existential threat, the research being done, and solutions being devised, rest principally in the hands of an elite group of mainly male, mainly white European and Anglo-American scientists from the affluent West?’3

In year 2010, the Cancun Conference of Parties (COP) Agreement brought some change to the UNFCCC by elevating discussions around adaptation, which began to broaden the types of knowledges and perspectives valued by the UNFCCC, eventually leading to inclusion of climate justice and human rights language within the Paris Agreement.4 The reframing of climate change as a justice and human rights issue allows for different voices and knowledges to inform the development of UNFCCC policies. This expansion of voices on climate policy included an acknowledgement that environmental change, including climate change, is gendered. Recognition of gender is largely limited to adaptation policy, meaning that the gendered impacts of mitigation policies and the troubled loss and damage agenda still require more feminist scrutiny.

2Insights from Feminist Theory for Climate Regulation

Intersectional theory demonstrates that a range of social factors influence how an individual lives their life and their ability to respond to and recover from changing environmental, social and economic conditions.5 As Katharine K. Wilkinson states as ‘The climate crisis is not gender neutral. It grows out of a patriarchal system that is also entangled with racism and white supremacy and extractive capitalism. The unequal impacts of climate change are making it harder to achieve a gender-equal world’.6

Gender is one significant factor determining an individual’s experience, but race, class, geographical location, marital status, sexuality, age and ability also significantly influence how an individual will experience a changing climate, making an intersectional lens crucial when developing climate policy.7 Gender remains a critical variable to consider within climate policy as social and cultural norms determine gender power relationships, sexual identity, and roles and responsibilities at the household and community levels. In many societies, these social and cultural norms mean that the ability of women and girls to respond and adapt to climate change is limited.8 In patriarchal societies, women are often excluded and marginalised in decision-making processes, preventing them from meaningfully contributing to climate-sensitive responsive planning, policy-making, and action at international and national levels.9

While gender equity may be accepted as a global goal, the lived reality for many women and girls is that cultural and traditional understandings of gender at the local level differ from these global conceptions.10 Climate change is accelerating gender inequality with research showing that rates of gender-based violence increase during disasters, pandemics and conflicts, with climate extremes amplifying inequalities, vulnerabilities and negative gender norms.11 The UNFCCC does not adequately recognise the role of climate change in exacerbating gender-based violence against women,12 provide any guidance on ensuring reproductive rights during climate change,13 or recognise gendered health impacts arising as a result of climate change.14

This article explores how the UNFCCC frames the gender issues, finding that the regime is silent on any real guidance for addressing gendered experiences of climate change. It finds that that the language of ‘gender balance’ has largely dominated as the key gender strategy within the regime. ‘Gender balance’ within the UNFCCC is largely seen as a numbers problem, with the solution centred on increasing the number of (usually elite) women present at COP negotiations and working on regime bodies, which Hilary Charlesworth has termed the ‘add women and stir’ approach to gender mainstreaming.15 While increasing gendered representation at the COP is a worthy goal, this approach is very limited and largely benefits women already in positions of power and deflects attention away from feminist inspired reforms seeking to address structural injustice arising from colonialism, capitalism and patriarchy. Feminist critique of climate policy extends far beyond thinking through how a woman experiences and responds to a changing climate and instead seeks to ensure that values, knowledges and preferences of the “other” shape international climate law.16

This article explores the development of gender considerations within the UNFCCC by reflecting upon where we have come from, where we are now and where we are going with respect with gender. This article shows that from 2001 to the present there have been a series of small gains for gender within the UNFCCC which this article will explain and critique. It is easy to get lost in the detail of the decisions, but we need to remember to ask –is the work of the UNFCCC on gender driving change? Do the COP decisions on gender reinforce messages on gender from other international forums, national debates and local level discourses? Or are these decisions on gender largely unknown, ignored or misunderstood? Is there some common consensus on what “doing gender” means in respect of climate change? And why does work on gender and climate change matter? This article explores these questions by reflecting back upon the operation of the UNFCCC since its inception and considers the action needed for meaningful progress in the future. In recommending future actions, the paper draws on insights from the Pacific and Australian experience.

3The Meaning of Gender within the UNFCCC: Where have we come from?

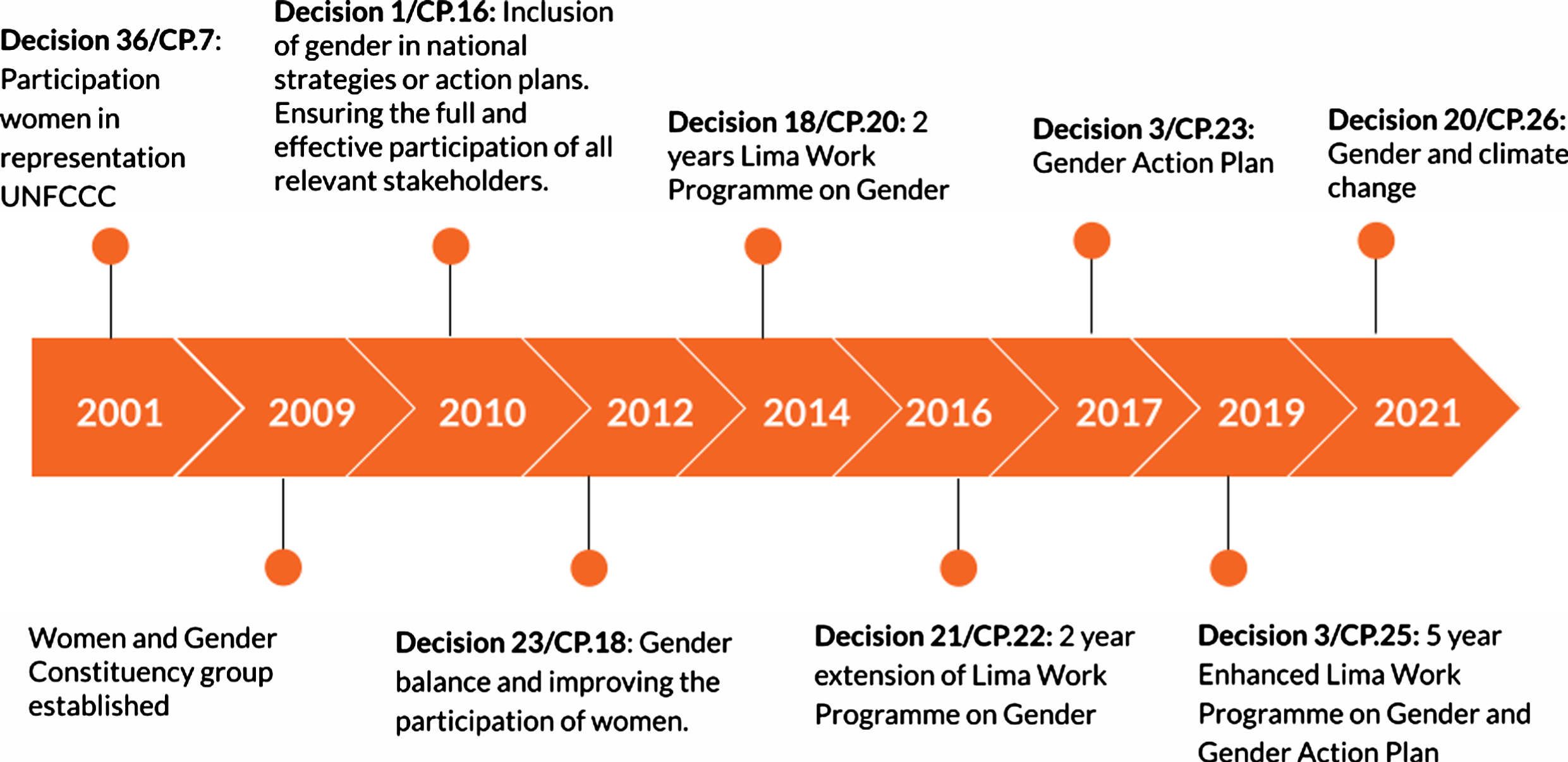

An examination of the history of negotiations and resolutions within UNFCCC reveals the limited progress that has been made on gender equity and addressing gendered experiences of climate change. The UNFCCC was the only instrument to emerge from the 1992 Earth Summit negotiations which failed to mention women or gender.17 Since then, the integration of gender into the UNFCCC has been exceedingly slow, with sporadic developments spanning over two decades (Fig. 1). A key reason for this lack of meaningful progress has been the focus on numbers –specifically the representation of women within State Party delegations to the UNFCCC and their participation in formal negotiations.

Fig. 1

The History of Gender in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The focus on numbers is reflective of the language employed in UNFCCC decisions and reports. Miriam Gay-Antaki’s work explores the language of gender within the UNFCCC by tracking the gender negotiations leading up to the drafting of the Paris Agreement. Her research unpacks the significance and emergence of certain gender terms, including ‘gender balance’ and ‘gender equality’, in the context of the UNFCCC negotiations.18 This research shows that while feminist groups have sought for the language of ‘gender equality’ to be inserted into UNFCCC instruments and COP decisions, the language of ‘gender balance’ has become dominant within the regime. ‘Gender equality’ refers to equality between women and men and is seen both as a human rights issue and as a precondition for and indicator of sustainable people-centred development.19 On the other hand, ‘gender balance’ is more limited in scope and instead focuses on the ratio of women to men in any given situation.

The choice to talk about gender in terms of ‘balance’ rather than ‘equality’ within the UNFCCC regime has translated into a focus on representation rather than substantive action. Furthermore, structural issues and process barriers have hindered the meaningful participation of women, so that even as numbers have gradually improved over time, more nuanced consideration of and action on gender issues has remained elusive, despite the relevant expertise and guidance being present in other parts of the UN system. Problems have included delays in the accreditation of women’s groups as official stakeholders within the UNFCCC;20 equity issues being viewed as North/South tensions rather than being defined by an intersectional analysis;21 the dominance of scientific and economic knowledge and thinking;22 and a characterisation of climate change as an urgent global problem justifying the exclusion of certain voices in order to solve more pressing issues.23

The first recognition of gender within a UNFCCC was in 2001, with COP Decision 36/CP.7 highlighting the need to improve the participation of women in Party delegations and in the formal negotiations.24 In 2010, the Cancun negotiations resulted in Decision 1/CP.16 stating that gender equality was necessary for effective action on climate change and encouraging parties to ‘consider’ gender, particularly in the development of national strategies and actions around deforestation and forest degradation to reduce emissions.25 No specific detail was provided as to what such ‘consideration’ should look like, and no specific actions were outlined.

In 2012, Decision 23/CP.18 once again focused on the issues of gender balance and representation first raised in Decision 36/CP.7, and adopted a goal of gender balance.26 The language used to describe this goal was weak, merely ‘inviting’ parties to make a commitment and to ‘encourage more women to nominate for climate bodies’.The Lima Work Programme on Gender (LWPG) was adopted in 2014 in Decision 18/CP.20.27 The LWPG creates a framework for reviewing all proposed implementations of gender-related mandates, awareness-raising for delegates on gender-responsive climate policy, capacity-building for women delegates, and appointments of gender focal points at the UNFCCC Secretariat. While the LWPG recognised global commitments to ‘gender equality’ under the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women and the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, the LWPG itself does not consistently adopt the language of ‘gender equality’, with this term appearing only once within the instrument. As with previous instruments, the LWPG favours the language of ‘gender balance’.28

The LWPG was extended in 2016,29 with a Gender Action Plan (GAP) finally being adopted in 2017.30 The GAP aims to mainstream gender through five priority actions: (a) capacity-building, knowledge management and communication; (b) gender balance, participation and women’s leadership; (c) coherence (i.e. strengthening the integration of gender considerations within the work of UNFCCC-constituted bodies, the Secretariat and other United Nations entities and stakeholders); (d) gender-responsive implementation and means of implementation; and (e) monitoring and reporting (i.e. of LWPG and the GAP).

The LWPG was reviewed in 2019 and extended for a further five years in order to implement the objectives of the GAP.31 The extension of the LWPG is referred to as the Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender (the Enhanced LWPG), which runs to November 2024. Under the enhanced program, the Secretariat is required to prepare biennial synthesis reports on progress in integrating ‘gender balance’ into constituted body processes and an annual report on the gender composition of constituted bodies established under the Convention, the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement, and on the gender and age composition of Party delegations to sessions held under these instruments, including a comparison with data for previous years. While the LWPG has stepped up efforts relating to gender across UNFCCC institutions and operations, its focus on gender ‘balance’ rather than ‘equality’ has continued to limit the focus to women’s representation, without meaningful consideration of whether and how such increased representation translates into different outcomes for women in terms of their experiences of climate change.

The Paris Agreement represented an opportunity to move beyond this focus on gender balance and to adopt a more meaningful commitment to gender equality in climate action. However, rather than take firm action to advance gender equality, the framing of the Agreement reflects the ongoing division over gender language. The Preamble (the soft part of the agreement)32 calls for all climate actions from States to:

‘respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity.’

There is no mention of gender equality or gender balance within the substantive provisions of the Paris Agreements, however. Instead, the section on adaptation refers to ‘gender responsive’ implementation. UNFCCC has not provided a definition of this term, but UNDP defines gender responsiveness as:

‘..outcomes that reflect an understanding of gender roles and inequalities and encourage equal participation, including equal and fair distribution of benefits. Gender responsiveness is accomplished through gender analysis that informs inclusion. Often, we must try to support efforts that transform unequal gender relations to promote shared power, control of resources, decision-making and support for women’s empowerment.’33

Article 7 establishes a goal of enhancing adaptive capacity, and under this provision ‘Parties acknowledge that adaptation action should follow a country-driven, gender-responsive, participatory and fully transparent approach’ (art 7.5). In relation to capacity building, Parties recognise that this should be (among other things) ‘gender-responsive’ (art 11.2). While the inclusion of gender responsiveness in the Paris Agreement could be considered a step forward, confusion as to the definition and an understanding of what this term requires in practice will present implementation challenges.

There remains, therefore, a large degree of uncertainty as to what ‘doing gender’34 requires in the context of the UNFCCC.35 The instruments and decisions of the regime tend to focus on gender balance and gender-responsiveness, but the UNFCCC does not clearly define these terms. Furthermore, ‘gender’ seems to be shorthand for ‘women’ in UNFCCC, with instruments of the regime failing to recognise and address the patriarchal structures and systems that perpetuate inequalities and make women, girls and other gender identities vulnerable or marginalised, thus silencing the diversity of voices.

As a result of this uncertainty in combination with resistance from some actors to embedding gender more meaningfully across the regime, the Secretariat has largely focused on reporting the number of women participating in COP negotiations and performing roles within regime bodies. Analysis of the Glasgow gender-related decisions below shows that this remains true of the UNFCCC’s most recent work. Further, it shows that the regime’s COP-related decisions tend to focus on the language of gender balance, with gender-responsiveness being dealt with at side events and capacity-building sessions outside of the official negotiation spaces.

In the interim, other UN entities focused on gender equality have attempted to outline what ‘doing gender’ in the UNFCCC might look like. Bharat Desai and Moumita Mandal’s work on gender and climate change explores developments beyond the UNFCCC in other fora of international environmental law. They have examined the UN Convention to Combat Desertification and the Convention on Biological Diversity along with the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and Agenda 21, finding that recognition of the gendered impacts of climate change are emerging, but that international law does not provide a coordinated approach to recognition and dealing with this issue.36

Developments on gender and climate have also occurred within international human rights and refugee law.37 The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) stated in 2009 that the Committee:

‘expresses its concern about the absence of a gender perspective in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and other global and national policies and initiatives on climate change’.38

Nearly a decade later, the Committee released General Recommendation No. 37 (2018) on gender-related dimensions of disaster risk reduction in a changing climate,39 marking the first time a UN body addressed in detail the links between human rights and the gendered impact of climate change. The same year saw the release of the Resolution 38/4 (July 2018) by the Human Rights Council, which recognised that the integration of a gender-responsive approach into climate policies would increase the effectiveness of climate change mitigation and adaptation, requesting an analytical study and a panel discussion on the topic.40 This was a decade later than the landmark Resolution 7/23 (March 2008) where the Human Rights Council first expressed concern that climate change ‘poses an immediate and far-reaching threat to people and communities around the world’.41 It is fair to say that if the UNFCCC came late to gender, the gender entities at the UN came late to climate change.

This was underscored when the UN’s only permanent forum dealing exclusively with gender equality, the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), held its 66th session in year 2022 on the importance of achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls in the context of climate change, environmental and disaster risk reduction policies and programs (CSW66).42. The Agreed Conclusions show the breadth of gender concerns with climate impacts but also the difficult State politics involved, coming only a few months after the Glasgow COP. COP26 featured strongly during the negotiations with many Member States not wishing to go back over the same ground covered by the Glasgow Climate Pact 2021. Delegates struggled with new terms related to climate change in the highly-charged gender context, with disputes arising over the terms ‘fossil fuels’, ‘climate justice’, ‘loss and damage’, ‘Net Zero’, and ‘environmental human rights defenders’.

But even so, the CSW66 Agreed Conclusions represent a much more three-dimensional view of the intersection of climate and gender equality. The CSW recognised with concern the disproportionate impacts of climate change, environmental degradation and disasters on all women and girls that can include loss of homes and livelihoods, water scarcity, destruction and damage to schools and health facilities and stressed the urgency of eliminating persistent historical and structural inequalities, discriminatory laws and policies, negative social norms and gender stereotypes that perpetuate multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination. As a result of displacement, including forced and prolonged displacement, CSW recognised that women and girls face specific challenges, including separation from support networks, increased risk of all forms of violence, and reduced access to employment, education, and essential health-care services, including sexual and reproductive health-care services, and psychosocial support. The CSW also expressed concern that the economic and social fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic has compounded the impacts of climate change, environmental degradation and disasters and has pushed people further behind and into extreme poverty in a cascading effect.43

In contrast, the process-driven reforms in the UNFCCC mirror the slow progress on including gender equality issues through the ‘Women Peace and Security’ thematic agenda in the UN Security Council, which has remained resistant to deeper transformative change for over 22 years (including recognising climate change as a security risk).44 Overall, we have seen little progress from the UNFCCC to advance gender-responsiveness in the first decades of its operation, settling instead for the search for ‘gender balance.’ The outcomes achieved at the Glasgow COP and their potential for deeper reform are analysed below:

4Where have we gotten to?

4.1Glasgow Gender Outcomes

4.1.1Gender in the Glasgow Climate Pact

This section reviews the Glasgow outcomes as a vehicle for assessing current progress on gender within the UNFCCC.45 The Glasgow Climate Pact is soft law, but not all soft law is created equal. While COP decisions are technically soft law, the Marrakesh Accords and Cancun Agreement provide examples of COP decisions driving ambition and generating far-reaching political –almost legal –consequences. COP decisions also play an important role in operationalising the Paris Agreement and a key role in clarifying global climate governance arrangements for the many institutions operating within the regime.46 While the Glasgow Climate Pact is technically soft law, the Pact has political significance and provides insights as to how the regime plans to address gender and climate change. The following analysis unpacks the difference between gender in the formal negotiations (leading to the Glasgow Climate Pact) versus gender in the side events to the COP, and evaluates the legal significance of the decisions addressing gender emerging from the Glasgow negotiations.

The Glasgow Climate Pact, in essence, requests Parties to ‘please do more’ with respect to gender but creates no mandatory obligations to do so. Gender is referenced four times within the Pact, including in the Preamble and within the substantive provisions of articles 62, 68 and 69, with the language of ‘gender equality’ starting to gain traction within the decision. The Preamble reads: ‘Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider . . . gender equality and empowerment of women.’ Article 62 repeats the language of gender equality and empowerment of women and ‘urges’ Parties to swiftly begin implementation of the Glasgow work programme on Action for Climate Empowerment.’ Article 68, meanwhile, focuses on gender balance and encourages ‘Parties to increase the full, meaningful and equal participation of women in climate action and to ensure gender-responsive implementation and means of implementation, which are vital for raising ambition and achieving climate goals.’ Article 69 ‘calls upon Parties to strengthen their implementation of the Enhanced LWPG and its gender action plan.’

In terms of evaluating progress made on gender in the Glasgow Climate Pact, a positive development is the inclusion of gender equality language not only in the Preamble but also within the substantive parts of the Pact. A limitation regarding gender in the Pact is the recommendatory nature of the wording on gender, which frames action on gender as voluntary rather than mandatory.

4.1.2Gender Composition Report

In pursuit of the gender balance focus, the Secretariat of the UNFCCC has released from 2013 annual gender composition reports which track the gender composition of constituted bodies established under the Convention, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, and the gender and age composition of Party delegations. This is the mechanism used by the regime to evaluate progress made towards gender balance. In preparation for Gender Day, the Secretariat of the UNFCCC prepared a report tracking gender composition for 2021.47 Some key statistics from this report include:

i. Gender composition varies among the constituted bodies and fluctuates from year to year. In 2021, the representation of women varied between 10 per cent on the Clean Development Mechanism Executive Board and 63 per cent on the Adaptation Committee.

ii. Representation of women in Party delegations increased by 9 per cent, with 49 per cent of party delegates being women.

iii. Representation of women as Party heads rose by 12 per cent, with 39 per cent of heads and deputy heads of Party delegations being women.

vi. A study put together by the Women’s Environmental and Development Organization (WEDO) suggests that at current levels of change, gender parity in national COP delegations will not be achieved until 2040 and gender parity in COP Heads of Delegations will not be achieved within the forecastable future.48

The COP25 decision requested the Secretariat to include information on speaking times by gender in the composition report. An analysis of speaking times was requested to provide a deeper understanding of the agency and power that women have in shaping UNFCCC COP outcomes. The speaking time analysis of COP26 was limited to plenaries (eight sessions) and meetings on the topics of finance (four) and technology (three). In total, 1,367.08 minutes were analysed, with Party delegates differentiated by gender, age and role in the meeting (Chair, co-facilitator or speaker). Some of the key findings from this analysis include:

i. While 51 per cent of Party delegations were men, they accounted for 60 per cent of the Party delegates who spoke in plenaries, 63 per cent of the total speaking time in plenaries and 74 per cent of speaking times in finance meetings.

ii. Chairs and co-facilitators accounted for 31–38 per cent of the speaking time in their respective meetings, highlighting the importance of this role in ensuring women’s visibility.

Addressing gender as an issue of data and percentages is an approach that the UNFCCC is competent and capable to perform. This approach is also reflective of problematising gender as a data and reporting issue.49 The Gender Composition Report from COP26 seems to suggest that the Secretariat is planning to expand this analysis across other sessions at future COP events. This exercise puts Parties on notice that gender balance is being actively pursued by the regime. The reports are, however, careful not to reveal the gender composition of individual countries’ delegations, instead providing an overview of gender participation by comparing gender representation across the five United Nations regional groups: African States, Asia-Pacific States, Eastern European States, Latin American and Caribbean States, and Western European and other States. This means that this reporting process is not a naming and shaming activity, and Parties not taking action to increase gender representation are not identified or singled out. Future reports could break down gender composition by country, and this would signal a commitment to taking gender balance more seriously.50

Reporting of gender composition within UNFCCC constituted bodies is more nuanced and includes detail not only on the existing gender composition of these regime bodies but also information on strategies used by these bodies to enhance gender balance.51 While it is encouraging to see gender balance being more actively pursued by the regime, these activities conform with the UNFCCC’s existing approach of dealing with gender as a problem of numbers as compared with viewing gender as a more critical variable which can help to address climate justice-related issues within the regime.52 Parties need more pressure placed on them to include gender within their future Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) pledges and to commit to gender-responsive implementation and financing of climate mitigation and adaptation policies and projects both within and beyond their jurisdictions.53

4.1.3The Glasgow Gender and Climate Change Decision

The Glasgow negotiations resulted in a specific decision on gender and climate change by the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI).54 This decision does not create any significant obligations for Parties but does provide insight into the types of gender activities and strategies that are being prioritised to drive implementation of the Enhanced LWPG with respect to gender-responsive implementation. The preamble of the decision acknowledges, with appreciation, the constructive, ongoing engagement in virtual meetings and workshops in support of GAP activities A.2 and D.6 1.

Activity A.2 of the Enhanced LWPG seeks to clarify the role and work of the national gender and climate change focal points. By the time of the Glasgow negotiations, 94 countries had nominated a National Gender and Climate Change Focal Point (NGCCFP), with these individuals largely coming from government ministries or environmental departments. An issue that is yet to be adequately resolved is how NGCCCFP positions are to be resourced and funded. While existing funding mechanisms of the UNFCCC such as the Green Climate Fund and Adaptation Fund have mainstreamed gender into their operational guidelines, this mainstreaming approach reflects a gender balance goal of including women within projects as opposed to supporting implementation of Enhanced LWPG.55 No specific funding mechanism currently exists within the UNFCCC to support NGCCCFP work.

In preparation for Glasgow, a virtual meeting was held in October 2021 to discuss and clarify the NGCCFP role.56 Key issues for discussion included: identifying the short-/medium- and long-term goals of the NGCCFP; gaining some consensus on the workload percentage for the role; and identifying the types of networks and relationships that need to be built to ensure integration of gender across all sectors, programs and institutions involved in climate policy at the national level. The short-, medium- and long-term goals created at this meeting are summarised in Table 1. These goals provide a very rough roadmap for understanding the objectives and activities of NGCCFPs.

Table 1

Outcomes of the meeting to discuss and clarify the NGCCFP role prior to the Glasgow COP

| Goals | Outcomes |

| Short-term | •Role of NGCCFP is known |

| •Relevant stakeholders are identified/recognised | |

| •Connections are made, tools are set up | |

| •Information and data about gender and climate change are disseminated | |

| •Capacities on climate change and gender are built | |

| •Gender is considered in the national sectorial policies | |

| •Gender is integrated into the NAP | |

| •Gender and climate change gaps are identified | |

| Medium-term | •Tools for articulation are identified |

| •Ministries are articulated | |

| •Action plan is implemented | |

| •All climate change-related institutional arrangements include a gender-focal person | |

| •Participation in negotiation spaces | |

| •Gender perspectives are integrated into all climate policy documents | |

| Long-term | •Gender is integrated into different sectors |

| •Gender is monitored in projects and programs | |

| •Focal points from different countries exchange knowledge and work in an articulated manner | |

| •Gender is integrated into all policy tools | |

| •Monitoring and evaluation of the plan are followed | |

| •UNFCCC GAP is channelled on a national level for sustainable positive impacts |

Gender focal point positions have been used as a mechanism for mainstreaming gender across a range of sectors. Lessons should be drawn from existing initiatives using the gender focal point model. Sangeeta Mangubhai and Sarah Lawless have explored some of the issues arising from the gender focal point model in the fisheries sector within Melanesia.57 This research found that those appointed to such positions had little-to-no experience working on gender, were required to fulfil the role in addition to the other tasks in their job description, and were largely ineffective because they were junior staff without institutional-level decision-making power. NGCCFPs will have a considerable mandate, with their effectiveness for enacting change being dependent upon governments’ willingness to integrate gender into national climate policies and providing financial and political support for the position to enact change.

Activity D.6.1 of the Enhanced LWPG focuses on sharinginformation on lessons learned among Parties that have integrated gender into national climate policies, plans, strategies and action (e.g., information on results, impacts and main challenges) and on the actions that Parties are taking to mainstream gender. A gender tracker tool has been developed by WEDO, which provides an analysis of how each country has or has not included gender within their NDC pledges and national climate policies. A summary of key observations from the 2016 pledges and updated 2020 pledges is summarised in Table 2.58

Table 2

Based on WEDO’s Analysis of Year 2016 and Updated 2020 NDC Pledges

| WEDO Analysis of 2016 NDC Pledges | WEDO Analysis of 2020 Updated NDC |

| In total, 64 of the 190 NDCs included a reference to women or gender. | Seven of the 14 updated NDCs analysed include a reference to women or gender. |

| All of these 64 countries are non-Annex I countries. WEDO notes this is significant as gender is rarely perceived as being relevant in mitigation contexts, which is the overwhelming focus on Annex I parties. | Norway is the only Annex I country to include a reference to gender. |

| Gender is most commonly referenced in relation to adaptation (27 countries), followed by mitigation (12 countries), implementation (9 countries), and capacity-building (5 countries). Of the documents, 22 reference gender as being mainstreamed across a number of sectors. | All 4 new NDCs include a reference to gender or women. |

| In total, 34 of 64 countries position the role of women as a vulnerable group. | |

| Fifteen NDCs refer to women as important decision-makers or stakeholders in the context of climate change policy-making, and 6 NDCs refer to women as agents or drivers of change. | |

| Complete absence of gender-responsive budgeting in NDC, which shows weak commitment to implementing gender provisions. | |

| Only Liberia and Peru identified legislation that has been specifically developed to address the intersection of climate change and gender. |

Gender work occurring under the SBI is more focused on gender-responsiveness to climate change. The creation of the NGCCFP provides an opening at the national government level to integrate gender into national climate activities and approaches. Networking among NGCCFPs to share lessons on how to gain traction will be essential. In addition, sharing templates and examples of gender-responsive wording and drafted policies will also be useful. This work is occurring as a result of the enhanced LWPG, which is acknowledged in COP decisions. As the UNFCCC is still largely structured on a State-based system, the mainstreaming of gender is largely assumed to be a job for government. In terms of expertise, civil society actors have valuable experience in working on gender and climate initiatives, and this expertise should be drawn on when seeking to ‘do gender’ in national climate policies and foreign aid-related activities.59

In preparation for COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt (6-18 November 2022), SBI released a synthesis report on the ‘Implementation of the activities contained in the gender action plan, areas for improvement and further work to be undertaken.’60 A total of 18 submissions were made to SBI from: the African Group, Antigua and Barbuda, Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), Argentina, Australia, Chile, the EU on behalf of its member States, Indonesia, Japan, Kenya, Madagascar, New Zealand, Nigeria, Panama, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the United States of America, Uruguay and five observing organisations. Assessing progress was challenging for the SBI due to the low submission rate and the lack of a common reporting structure meant that information provided by the Parties and observers were not easily comparable.61 The SBI report notes that Parties made efforts to report under each of the five GAP priorities but that effort was not evenly distributed across the various activities with most countries making the most effort on reporting on activity A.1 (capacity building efforts in mainstreaming gender) and activity B.1 (gender representation in UNFCCC processes).62

Moving forward there are really two key issues that need to be improved in gender reporting under the GAP. Firstly, there needs to be some form of common reporting framework or indicators for future GAP submissions to avoid cherry-picking of data that makes it appear that work is being done on gender and climate when in fact it has been done under other programs and then rebranded to count for GAP purposes. Secondly, it is important that countries making these submissions acknowledge and recognise that gender and climate is not an “us and them” problem. What this is means is the Global North countries must not carry out capacity building gender-responsive climate programs through their aid budgets while completely ignoring gender within their own NDCs and national climate laws and policies. In order to be credible voice on gender and climate, countries in the Global North must lead by implementing gender-responsive climate policy within at home in addition to funding aid projects which mainstream gender in other countries.63

5Where to from here? Getting Strategic on Gender

Within the UNFCCC system, a concrete pathway to enhance action on gender and climate could be furthered through the hosting of a Gender COP. This Gender COP would seek to move beyond the Enhanced LWPG and change the focus of the regime from gender balance to one focused on ensuring gender equality in a changing climate. Despite the lengthy negotiation process of the UNFCCC, momentum has slowly been building to support gender, human rights and environmental justice as future COP key agenda items. For much of the 30 years of the UNFCCC negotiations, the focus has been on mitigation and mechanisms to address the cause of greenhouse gas emissions. More recently, at the insistence of the Global South, adaptation has become a more prominent agenda topic alongside issues of climate finance and loss and damage, spaces where an intersectional feminist lens is much needed.

Lessons from the regime foretell that for any issue or mechanism to be prioritised, it takes years of consistent advocacy, as well as a group of countries, including a Chair or President of the COP, to elevate the issue. At COP23, Fiji was the chair of the annual conference, and it chose to elevate two issues: a focus on Small Island Developing States and oceans. Since 2017, oceans have become a permanent issue pursued by groups like the Ocean Alliance, who have called for more attention to dialogue and addressing the impact of climate change on oceans. This has opened up opportunities for research, collaborative inter-governmental initiatives and climate financing to address national government needs like the blue economy. During the United Kingdom’s presidency, its priority was to have a goal of net zero emission and financing for adaptation. The former meant the arduous task of securing a commitment from all States to a future goal to ensure that economies like China, the United States and Australia set equally ambitious pathways for net zero compared to States like Tuvalu and the Marshall Islands. Furthermore, elevating adaptation and finance as key priorities meant assurance for the Global South to discuss steps in addressing issues of loss and damage and oceans. These past experiences on other issues illustrate the strategies for elevating gender in the UNFCCC regime.

Within the UNFCCC system, elevating gender requires a commitment from an incoming COP President to set gender as its key goal. Like Fiji and its Islands COP, or the United Kingdom and its Net Zero and Adaptation Finance COP, there is an opportunity for a Gender COP –a COP that seeks a commitment from all countries to invest in gender in all parts of climate action. A Gender COP will require the UNFCCC to further invest in systems and call for mechanisms to address not just women’s participation but gender equality and equity in all facets of climate change work. Similar commitments are seen in the space of sustainable development. Meanwhile, other UN entities such as the CSW, HRC and CEDAW are not waiting for gender to be integrated into the UNFCCC and are mainstreaming climate change into their work programs on gender equality, which may result in a two-speed UN on this topic instead of a coherent approach. At the same time, developments from outside the COP can influence the regime, so the achievements of other UN bodies could provide considerable guidance to a COP President.

The COP presidency is rotated through the five UN regions. When Dubai hosts in 2023 it will represent Asia and the Pacific. There are certain countries, as seen in COP26 Gender Day, that are champions of gender equality, such as Sweden, New Zealand, Bolivia, Samoa, Venezuela and Tanzania, who may be future Gender COP supporters.64 The timing of such a Gender COP will need to be planned around the UNFCCC busy years, such as the 2025 Global Stocktake or the 2030 Paris Agreement commitment period year. Leadership for a Gender COP may come from countries with women leaders or may come from countries with more advanced National Gender Action Plans. The hosting of a Gender COP would pave the way for more global climate action on gender.

Beyond this long-term vision of a Gender COP, there is more that can be done now. Capacity continues to be a challenge. While some training exists, for example negotiator training for women,65 gender training for journalists or meteorology officers,66 or mainstreaming gender across climate finance,67 more needs to be done. At best, capacity is channelled at the national government level but has not reached the community and sub-national government levels. At the same time, there has been limited acknowledgement or research to explore indigenous/traditional and local knowledges, institutions and practices relating to climate change impacts on gender relations in society. In the Pacific, a community of practice on climate change has developed over the three decades. At best, this knowledge and work in understanding climate action in the Pacific is situated at the national government level. To enhance the work on gender and climate change, acknowledgement of and investment in understating how climate impacts gender relations is needed at the local level as well, not only in the form of equity and equality but also in understanding how climate is linked to tension and violence.68

Furthermore, to be able to influence decision-making, information power is needed. While academic research is wanting in terms of understanding gender and climate change, so too is information in the grey literature. Only a handful of technical reports or projects have focused on the nexus of gender and climate change, as well as the contributions to global action. Programs run through UN Women on gender, climate and security,69 the Food and Agriculture Organization on rural women and agriculture,70 Oxfam on climate finance and women71 and the current work of the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR)72 are attempting to fill this information void. An investment in research and technical work will build a body of knowledge to support the claims and positions of countries and coalitions of Small Island States in climate negotiations. One major area for research is to support the work of National Gender Action Plans in investigating how such reporting systems can be an extension of current reporting systems and not a burden. It is essential to build the gender climate change body of knowledge through academic, private and civil society research to inform policy and governments.

There is also a need to enhance participation and meaningful engagement with the existing gender processes of the UNFCCC. With the second phase of the Enhanced LWPG, Parties are ultimately saying the program can do more but that this requires political will. While the gender framework is starting to emerge, as discussed above, only 18 countries made submissions on GAP implementation. States in the Global South and their coalitions need to be active in setting the agenda and in their participation in these gender spaces. This means negotiating funding and support to do the work and ensuring that gender work is carried out in culturally appropriate and locally specific ways. In addition, lessons on gender from other international forums show that, in order for gender to be meaningfully incorporated, it must be properly financed and supported.73 As such, there is a need to ensure that a funding modality exists to fund national gender climate focal point positions and their initiatives. This will require amending existing UNFCCC financing mechanisms to either include a direct gender funding modality or to ensure that the Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund and other funding bodies embed and prioritise gender projects beyond a gender balance approach.

Gender is a priority issue in the Pacific and the Australian government has expressed interest to co-hosting a future COP with a Pacific country.74 Gender should be one of the priority goals at this COP. In order to build an effective campaign on gender in the Pacific and Australia, work should be carried out through the One CROP Plus initiative to identify a political champion to spearhead the Pacific gender campaign. AT COP27, the Niue Minister for Natural Resources (Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Meteorological services) was the Political Champion on Gender to elevate the issue through the negotiations and in the international media; it would prove beneficial for Australia to have a similar champion or ambassador for the cause. Woven into such campaigns are the diverse stories of women from across the Pacific, the resilience of the community and local, traditional and indigenous institutions and practices, leadership of government and civil society, and the innovation of regional organisations. A Pacific-led COP campaign on gender equality and climate justice supported by the Australian government would be an incredibly powerful forum for improving political attention to support gender equality in a changing climate.

6Conclusion

This article has explored the past, present and potential future of gender within the UNFCCC, showing that most progress has been largely tokenistic in terms of addressing gendered risk and vulnerability in a changing climate. As this article has shown, developments on gender within the UNFCCC started very slowly with gender first being recognised in 2001. From 2001 onwards the language of gender balance has dominated within the UNFCCC leaving confusion as to what gender means and what it requires beyond increasing the number of women participating in COP negotiations. While progress on gender balance is important, it is only a first step in taking action on gender and climate change and more critical feminist approaches and action on embedding gender more meaningfully in climate policy implementation are urgently needed. Progress on gender and climate from forums outside the COP frameworks such as international human rights law bodies, multilateral international environmental agreements and international refugee and displacement law should be used to inform UNFCCC gender equality future endeavours.75

Turning to the present, the article has demonstrated that current gender work is focused upon the Enhanced Lima Gender Action Plan and specifically on creating national climate change gender focal point positions and embedding gender into Nationally Determined Contribution commitments. Work in this space has the potential to move gender beyond a counting game to one of ensuring gender equality in the implementation of climate policy. There are two key barriers blocking progress on gender equality climate policy, however. Firstly, there is a lack of a specific funding modality to support gender beyond ensuring that women are included within UNFCCC projects. Secondly, there is a lack of political engagement by most Parties on gender within the UNFCCC.

In terms of a concrete pathway forward on gender, this paper suggests that the hosting of a Gender COP would be a strategic way of overcoming these two barriers blocking progress on gender equality and climate policy. Significant traction on gender could be achieved by a group of countries working together to host a ‘Gender COP’. Such an event would result in collaborative inter-governmental initiatives and financing to support gender implementation of climate policy and signal to all Parties that gender is a legitimate and key priority of the regime. The question that remains to be answered is: which country or countries will take charge on gender and climate within the UNFCCC?

Notes

1 United Nations (1992), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 9 May 1992, 1771 UNTS 107 (entered into force 21 March 1994).

2 Carol Bacchi (2009), Analysing Policy: What is the problem represented to be? (Melbourne, Australia: Pearson Education Pub.)

3 Sherilyn Macgregor (2014), ‘Only Resist: Feminist Ecological Citizenship and the Post-politics of Climate Change’ 29 : 3 Hypatia 617, 625.

4 Cancun Agreement (2016), UNFCCC 16th Session of the Conference of the Parties available at: http://unfccc.int/meetings/cop_16/items/5571.php. See in particular, UNFCCC (2010), ‘Outcome of the Work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-Term Cooperative Action under the Convention’, Decision 1/CP.16 (29 November 2010), paras.7, 8 and 12. See further, Centre for International Environmental Law (2011), ‘Analysis of Human Rights Language in the Cancun Agreements (UNFCCC 16th Session of the Conference of the Parties)’ available at: https://www.ciel.org/reports/analysis-of-human-rights-language-in-the-cancun-agreements-unfccc-16th-session-of-the-conference-of-the-parties-march-2011-3/.

5 H.O. Pörtner et al (2022), Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press) See in particular Chapter 2.

6 Quoted in Nicole Greenfield, ‘What is Climate Feminism?’ (18 March 2021) available at https://www.nrdc.org/stories/what-climate-feminism. See further, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson (2020), All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis (London, UK: One World Publication).

7 Farhana Sultana (2022), ‘Critical Climate Justice’ 188 The Geographical Journal, 118-124.

8 Nitya Rao et al (2017), ‘Gendered Vulnerabilities to Climate Change: Insights from the Semi-Arid Regions of Africa and Asia,’ 11 : 1 Climate and Development, 14.

9 Sophia Huyer et al (2020), ‘Can We Turn the Tide? Confronting Gender Inequality in Climate Policy’, 28 : 3 Gender & Development, 571.

10 Mariola Acosta et al (2021), ‘Examining the Promise of “The Local” for Improving Gender Equality in Agriculture and Climate Change Adaptation’ 42 : 6 Third World Quarterly, 1135.

11 Bharat H. Desai and Moumita Mandal (2021), ‘Role of Climate Change in Exacerbating Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Women: A New Challenge for International Law, 51 : 2 Environmental Policy and Law, 139.

12 Ibid, see also Rowena Maguire (2023), ‘A Feminist Critique on Gender-Based Violence in A Changing Climate: Seeing, Listening and Responding’ in Cathi Albertyn et al, Feminist Frontiers in Climate Justice: Gender Equality, Climate Change and Rights, 68 (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar).

13 Women Deliver (2021), ‘The Link between Climate Change and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: An Evidence Review’ available at https://womendeliver.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Climate-Change-Report.pdf

14 Esther Onyango and Rowena Maguire (2022), ‘Gendered Exposure, Vulnerability and Response: Malaria Risk in a Changing Climate in Western Kenya in the Frontiers in Climate (pre-press).

15 Hilary Charlesworth (2005), ‘Not Waving but Drowning: Gender Mainstreaming and Human Rights in the United Nations’ 18 Harvard Human Rights Journal 14.

16 Farhana Sultana (2022), ‘Critical Climate Justice’, 188 The Geographical Journal, 118.

17 Rowena Maguire (2021), ‘Feminist Approaches’ in Lavanya Rajamani and Jacqueline Peel (eds), The Oxford Handbook on International Environmental Law, 2ed., 200 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press)

18 Miriam Gay-Antaki (2020), ‘Feminist Geographies of Climate Change: Negotiating Gender at Climate Talks’, 115 Geoforum 1.

19 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” . . . “everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, . . . birth or other status.” United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN General Assembly, 10 December 1948.

20 Karen Morrow (2013), ‘Ecofeminism and the Environment: International Law and Climate Change’ in Margaret Davies and Vanessa Munro (eds), The Ashgate Research Companion to Feminist Legal Theory, 377 (London, UK: Routledge)

21 Rowena Maguire (2019), ‘Gender, Climate Change and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’ in Sue Harris Rimmer and Kate Ogg (eds), Research Handbook on Feminist Engagement with International Law, 63 (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar).

22 Susan Buckingham (2017), ‘Gender and Climate Change Politics’ in Sherilyn MacGregor (ed), Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment 390 (London, UK: Routledge)

23 Macgregor, note 3, See also Hilary Charlesworth (2002) ‘International Law: A Discipline of Crisis’ 65 The Modern Law Review, 377.

24 UNFCCC (2001), ‘Improving the Participation of Women in the Representation of Parties in Bodies Established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and Kyoto Protocol’ COP Decision 36/CP.7 (9 November 2001).

25 Decision 1/CP.16, note 4.

26 UNFCCC, ‘Promoting gender balance and improving the participation of women in UNFCCC negotiations and in the representation of Parties in bodies established pursuant to the Convention or the Kyoto Protocol,’ COP Decision 23/CP.18 (7 December 2012); UNFCCC, ‘Improving the participation of women in the representation of Parties in bodies established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or the Kyoto Protocol’ COP Decision 36/CP.7 (9 November 2001).

27 UNFCCC, ‘Lima Work Programme on Gender’ COP Decision 18/CP.20 (12 December 2014).

28 Rowena Maguire and Bridget Lewis (2018), ‘Women, Human Rights and the Global Climate Regime’ 9 : 1 Journal of Human Rights and the Environment, 51.

29 UNFCCC, ‘Gender and climate change’ COP Decision 21/CP.22 (17 November 2016).

30 UNFCCC, ‘Establishment of a gender action plan’ COP Decision 3/CP.23 (17 November 2017).

31 UNFCCC, ‘Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender and its Gender Action Plan’ COP Decision 3/CP.25 (15 December 2019). See also Huyer et al note 9.

32 Lavanya Rajamani (2016), ‘The 2015 Paris Agreement: Interplay between Hard, Soft and On-Obligations’ 28 : 2 Journal of Environmental Law, 337.

33 UNDP (2019), Gender Responsive Indicators: Gender and NDC Planning for Implementation, available at: https://wrd.unwomen.org/default/files/2021-11/undp-ndcsp-gender-indicators-2020.pdf

34 Nancy Johnson et al (2018), ‘How Do Agricultural Developments Projects Empower Women? Linking Strategies With Expected Outcomes,’3 : 2 Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 1.

35 Margaret Alston (2013), ‘Gender Mainstreaming and Climate Change’ 47 Women’s Studies International Forum, 287.

36 Ibid, Desai and Mandal, note 11, 143.

37 Desai and Mandal, note 11, 143.

38 Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (2009), ‘Statement of the CEDAW Committee on Gender and Climate Change’, 44th session, New York (20 July –7 August 2009) available at https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cedaw/docs/Genderand_climate_change.pdf

39 Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (2018), General recommendation No. 37 (2018) on the gender-related dimensions of disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change, CEDAW/C/GC/37 (13 March 2018), available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-recommendation-no37-2018-gender-related.html

40 Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 38/4 (5 July 2018)

41 Human Rights Council, Human Rights and Climate Change, Resolution 7/23 (28 March 2008).

42 UN Women (2022), ‘UN Commission on The Status of Women Reaffirms Women’s and Girls’ leadership as key to address climate change, environmental and disaster risk reduction for all’ (Press Release, 26 March 2022) available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/press-release/2022/03/press-release-un-commission-on-the-status-of-women-reaffirms-womens-and-girls-leadership-as-key-to-address-climate-change-environmental-and-disaster-risk-reduction-for-all

43 Commission on the Status of Women (2022), ‘Achieving Gender Equality and The Empowerment Of All Women and Girls in The Context of Climate Change, Environmental and Disaster Risk Reduction Policies and Programmes’ E/CN.6/2022/L.7 (29 March 2022), available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3970226?ln=en.pdf

44 United Nations (2022) ‘Slow Progress For Women Helping Forge Peace, Security Council warned,’ UN News, 20 October 2022, available at: https://press.un.org/en/2021/sc14732.doc.html

45 UNFCCC (2021), ‘Glasgow Climate Pact, Decision- CP.26’, (13 December 2021), advance unedited version available at https://unfccc.int/documents/310475.pdf.

46 Antto Vihma (2011), ‘Climate of Consensus: Managing Decision-Making in the United Nations Climate Negotiations’ 24 : 1 Review of European Community and International Environmental Law, 58-60; Lavanya Rajamani (2011), ‘The Cancun Climate Agreements: Reading the Text, the Subtext and the Tea Leaves’ 60 : 2 International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 499.

47 Secretariat of UNFCCC (2021), ‘Gender Composition’, FCCC/CP/2021/4 (20 August 2021), available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cp2021_04E.pdf

48 Women’s Environment and Development Organization (2022), Women’s Participation in the UNFCCC: 2022 Report, available at: https://wedo.org/womens-participation-in-the-unfccc-2022-report.pdf

49 Bacchi, note 2.

50 Rowena Maguire and Bridget Lewis (2018), ‘Women, Human Rights and the Global Climate Regime’ 9 : 1 Journal of Human Rights and the Environment, 51.

51 UNFCCC, ‘Gender Composition’, note 47, Annex II.

52 Carmen G. Gonzalez (2021), ‘Racial Capitalism, Climate Justice, and Climate Displacement’ 11 : 1Oñati Socio-Legal Series, 108.

53 For further detail on NDC and gender inclusion see: International Union for the Conservation of Nature (2021), Gender and National Climate Planning: Gender Integration in the revised Nationally Determined Contributions (2021), available at: https://genderandenvironment.org/gender-and-ndcs-2021.pdf

54 UNFCCC (2021), Subsidiary Body for Implementation, Gender and Climate Change, FCCC/SBI/2021/L.13 (6 November 2021), available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sbi2021_13_adv.pdf

55 See for example, The Green Climate Fund Mainstreaming Gender in Climate Fund Projects Guidelines whose purpose is to mainstream gender into GCF projects, (2017) available at: https://www.greenclimate.fund/document/mainstreaming-gender-green-climate-fund-projects.pdf

56 UNFCCC (2021), Virtual Workshops –Role of the National Gender and Climate Change Focal Points, (1-2 November, 2021) available at: https://unfccc.int/topics/gender/events-meetings/workshops-dialogues/virtual-workshops-role-of-the-national-gender-and-climate-change-focal-points.pdf.

57 Sangeeta Mangubhai and Sarah Lawless (2021), ‘Exploring Gender Inclusion in Small-Scale Fisheries Management and Development in Melanesia’ 123, Marine Policy 104.

58 WEDO (2021), Gender Climate Tracker, available at: https://www.genderclimatetracker.org/gender-ndc/quick-analysis.pdf

59 See further on different actors in climate governance, Katherine Elizabeth Browne (2022), ‘Rethinking Governance in International Climate Finance: Structural Change and Alternative Approaches’ 13 : 5, WIREs Climate Change, 795.

60 UNFCCC (2022), Subsidiary Body for Implementation, ‘Implementation of the activities contained in the gender action plan, areas for improvement and further work to be undertaken’ (3 June 2022), available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sbi2022_8.pdf

61 Ibid, [10].

62 Ibid, [9].

63 Susan Harris Rimmer, Bridget Lewis, Rowena Maguire, Esther Onyango and Maria Tanyag (2022), ‘Feminist Perspectives on Climate Diplomacy’ in Australian Feminist Foreign Policy Coalition Issues Paper, Issue 2 (May 2022), Available at: https://iwda.org.au/assets/files/AFFPC-issues-paper-Climate-Diplomacy-Harris-Rimmer-et-al.pdf.

64 Scottish Government (2021), ‘Celebrating Gender Day at COP 26’ (Press Release, 9 November 2021), available at: https://www.gov.scot/news/celebrating-gender-day-at-cop26.pdf

65 Women’s Environment and Development Organization (2019), ‘Learning and Leading: Pacific Women Climate Negotiators Train for the Future’ (31 May 2019) available at: https://wedo.org/learning-leading-pacific-women-climate-negotiators-train-for-the-future.pdf

66 Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (2021), ‘Supporting gender equality and social inclusion across Pacific Met Services’ (21 April 2021), available at: https://www.sprep.org/news/supporting-gender-equality-and-social-inclusion-across-pacific-met-services.html

67 UN Women (2015), Pacific Gender and Climate Change Toolkit, 2015 available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/9/pacific-gender-and-climate-change-toolkit.html

68 UN Women (2014), Climate Change Disasters and Gender Based Violence In The Pacific, 2014, available at: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/1/climate-change-disasters-and-gender-based-violence-in-the-pacific.html

69 UN Women (2020), Gender, Climate and Security: Sustaining Inclusive Peace on The Frontlines of Climate Change, 2020, available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/06/gender-climate-and-security.pdf

70 UN Food and Agriculture Organization (2019), Country Gender Assessment of Agriculture and the Rural Sector in Samoa, 2019; available at: https://www.fao.org/3/ca6156en/ca6156en.pdf.

71 Jale Samuwai and Eliala Fihaki (2019), Making Climate Finance Work for Women: Voices from Polynesian and Micronesian Communities, (Oxfam in the Pacific, 2019) available at: https://www.pasifikarising.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/03/Making_climate_finance_work_for_women.pdf

72 Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (2023), ‘Institutional barriers to climate finance through a gendered lens in Fiji, Samoa and the Solomon Islands’, Research Project code: CLIM/2021/110, (2021-2023), available at: https://www.aciar.gov.au/project/clim-2021-110.html

73 Aisling Swaine (2009), ‘Assessing the Potential of National Action Plans to Advance Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325’, 12 Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law, 403.

74 Richie Merzian, Rhiannon Verschuer and Sienna Parrott (2022), ‘COP29 in Australia: How Hosting An International Climate Conference Could Revive Australia’s Regional and Global Reputation’ (The Australia Institute, May 2022), available at: https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/P1208-COP29-in-Australia-WEB.pdf.

75 For such future endeavors see, generally, Bharat H. Desai (2023), “Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call for the Decision-Makers”, Green Diplomacy, 15 February 2023; Global Climate Change as a Planetary Concern: A Wake-Up Call for the Decision-makers — Green Diplomacy; Bharat H. Desai (2022), “Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern” in Bharat H. Desai, Ed. (2023), Regulating Global Climate Change: From Common Concern to Planetary Concern, Chapter 1 (Amsterdam: IOS Press).