The Rights of the Indigenous People and the Amazon: A Road Ahead+

Abstract

The Amazon is one of the most complex and important biomes in the world. Its role in global climate stability is recognized worldwide. The political changes that took place in Brazil in 2022 brought a new hope for the protection of the forest and the different peoples that inhabit it. The dissemination of correct information about the current stage of the Amazon is essential for the forest to be preserved. One cannot imagine the future without analyzing past successes and mistakes so as to avoid the repetition of failed policies. It is essential both for the protection of the rights of the indigenous peoples as well as preservation of thier habitat of Amazonia.

1Introduction

This article, divided into six topics, aims to provide the reader with a panoramic view of the current stage of Amazonian cooperation and the need for its expansion. As demonstrated throughout the text, the Brazilian Amazon faces important challenges that demand financial, human, and technological resources that are beyond the country’s current budgetary capacities. During the four years of President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, the disregard for the Amazon, its indigenous peoples, and even the urban areas reached unimaginable levels which were reflected in the constant reduction of the budgets of government environmental control agencies, such as the Brazilian Institute for the Environmental and Natural Resources (in Portuguese, IBAMA)1 and the Chico Mendes Institute for Conservation of Biodiversity (in Portuguese, ICMbio)2 and even of the Environment Ministry. The Amazon has become an important emitter of greenhouse gases [GHG], with its municipalities occupying 7 of the 10 positions for the highest GHG of the country‘s emissions.

During President Jair Bolsonaro’s Administration, the Amazon was left to fend for itself and its general conditions of conservation and preservation. It is deteriorating significantly, with an increase in fires, deforestation, and the murder of indigenous leaders and traditional peoples. Increased invasion of protected lands and indigenous territories by illegal loggers and miners contamination of soil and water by mercury, abuse and violence against indigenous peoples, especially in the Yanomami territory, where an estimated 30,000 illegal miners are present, have aggravated the situation due to ineffective measure taken by the Bolsonaro‘s administration to tackle the issue and to prevent the invasion of the indigenous land. With the recognition that the Bolsonaro’s Government was a huge setback in terms of protecting human rights and the environment, the article seeks to indicate some future steps so that the path of protection can be resumed.

2The International Cooperation in the Amazon

The knowledge of the Amazonian reality is essential for the international community to play its proper role in cooperating to protect this important biome. The Amazon, in addition to its indigenous peoples, has a large urban population that, like the indigenous ones, needs help from the international community in order to overcome the current difficulties, especially regarding the improvement of urban conditions, such as sanitation, access to clean water, garbage collection and other essential public services.

The Amazon is part of a huge hydrographic basin embracing several ecosystems, the Amazon Forest being the main one. The region is shared by nine countries, but most of its area is located within Brazilian territory. Indeed, the Amazon basin is the largest river drainage on Earth, almost two-fold the river Congo basin3. The basin is drained by the Amazon River, the world’s largest river in terms of discharge, and the second longest river in the world after the Nile. The river is made up of over 1,100 tributaries, seventeen of which are longer than 1000 miles, and two of which (the Negro and the Madeira) are larger, in terms of volume, than the Congo river.4

In year 1978, the Amazon Cooperation Treaty (ACT) was signed5 and gave rise to the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ATCO) an intergovernmental organization formed by the eight Amazonian countries to protect the Amazon rainforest (Fig. 1): Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela which is the only socio-environmental organization in Latin America.6

Fig. 1

(Source: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/).

The Amazon River Basin has 25, 000 t km of navigable rivers, covering Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela. The Brazilian States located around the Legal Amazon River Basin7 are (1) Amazonas, (2) Acre, (3) Pará, (4) Amapá, (5) Roraima, (6) Rondônia, (7) Mato Grosso, (8) Maranhão, (9) Goiás and (10) Tocantins, occupying about 5 million km2, corresponding to 59% of the Brazilian territory and circa 67% of the world’s tropical forests. It is estimated that the Brazilian Legal Amazon has one third of all the existing trees in the world and 20% of the fresh water. Approximately 30 million people live in the Amazon region, out of which around 70% are urban dwellers. The urban issue in the Amazon is a forgotten agenda that needs to be addressed by both Brazil and the international community, as soon as possible.

3Land Tenure and Property Rights in the Amazon

Land tenure and property rights in the Amazon are extremely problematic. There are many illegal titles which collectively make up greater area than the extension of the municipalities in which they are located. According to studies carried out by IMAZON,8 more than half (53%, or about 2.6 million square kilometers) of the Legal Amazon have an uncertain land tenure status.

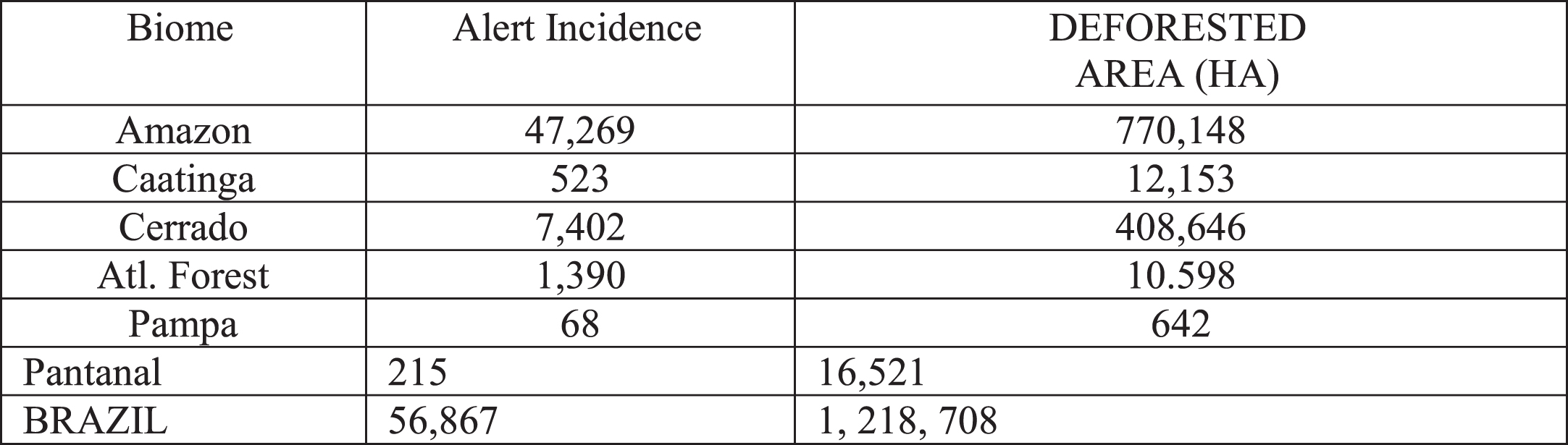

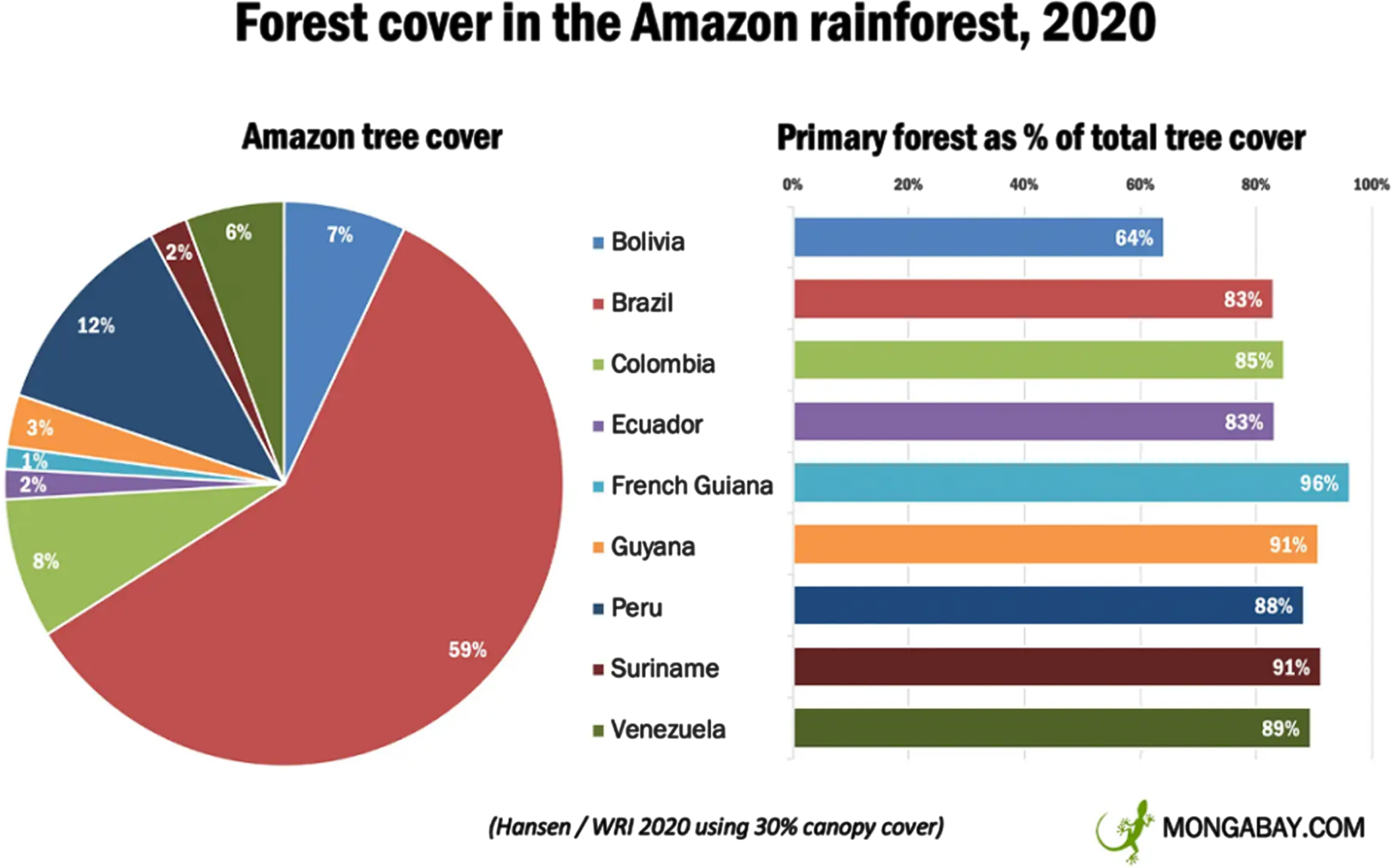

Due to the immense dimensions of the Amazon, it is difficult to identify the main threats faced by the region, because in each of its corners the problems are different. However, it is possible to have a quite balanced overview. First of all, it seems that traditional communities and indigenous peoples face enormous threats because of various illicit activities in the Amazon, such as (1) uncertainty about land rights; (2) trafficking of animals, drugs and weapons; (3) illegal mining with heavy use of mercury causing environmental and health damages; (4) trespassing of indigenous lands and protected areas; (5) fires; (6) loggers etc. The Brazilian law enforcement agencies understand that all these activities are linked in webs of organized crime.9 Nevertheless, Brazil holds an uncomfortable first place in deforestation (Fig. 2) among all the Amazonia countries.

Fig. 2

(Source: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/).

The land tenure in the Amazon is fundamentally regulated by the States that usually do not have the necessary institutional strength or political willingness to block illegal tenure. There has been much debate about such laws even in the Courts. Preventing the illegal occupation of public, indigenous and traditional communities lands require more than the legal framework that, in general, Brazil has. Public funding, capacity building and institutional strengthening of the Union, States and Municipalities are necessary to ensure constant monitoring of the state of Amazonian lands and, above all, to prevent illegal occupations.

The Elisabeth Haub Award for Environmental Law and Diplomacy expressed a strong commitment in 2020 for defending those who fight for the environment. It was reflected in recognition of the role of the environmental defenders (globally who lost their lives defending their land and the environment from destructive industries and deforestation).

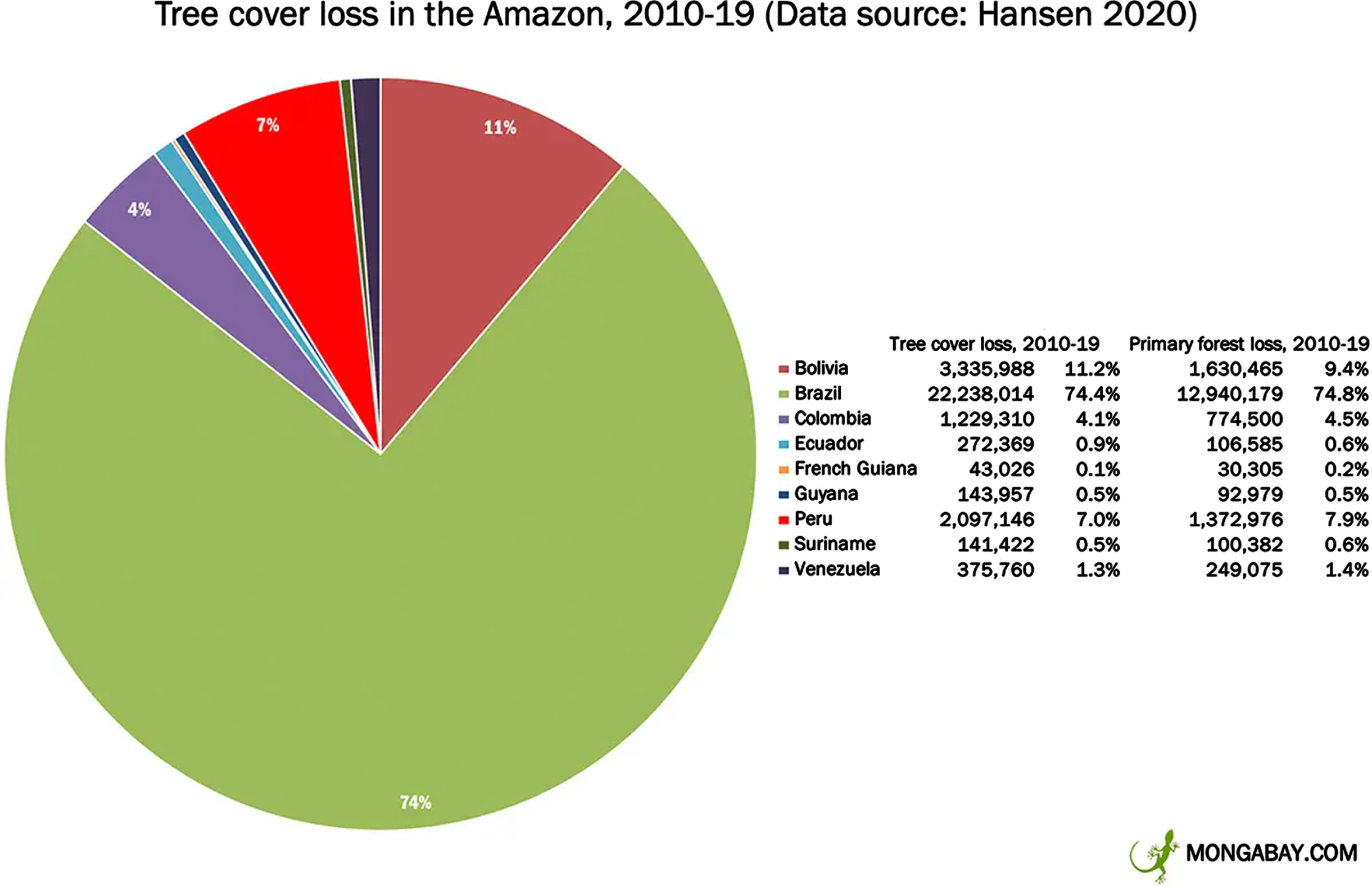

3.1Land Conflicts in the Amazon

Threats and violence against environmental defenders are, globally, a very serious problem. The Global Witness, a non-governmental organization has been collecting data on killings of land and environmental defenders since year 2012.10 In year 2020, non-governmental organizations (NGO) recorded 227 lethal attacks – an average of more than four people a week – making it once again the most dangerous year on record for people defending their homes, land and livelihoods, and ecosystems vital for the biodiversity and the climate. There have been many land related conflicts (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Land Conflicts in Brazil.

Unfortunately, Brazil was the leader in murders of environmentalists in the world in the last decade. Of the 1,733 deaths of environmental defenders recorded across the globe, in the period from 2012 to 2021, 342 occurred in this country – almost 20% of the total. More than 80% of the murders took place in the Amazon.11 The situation, as it turned out, is not new. The Pastoral Land Commission [CPT], an agency linked to the Catholic Church, reports that, since 1985 of the 1,536 murders in the countryside recorded by the entity, only 47 have gone to trial. Of these, 39 principals and 139 executors were convicted.12 Insecurity in the Amazon region increased in the last 4 years due to a non-priority and underfunding of the law enforcement agencies especially under the Bolsonaro administration.

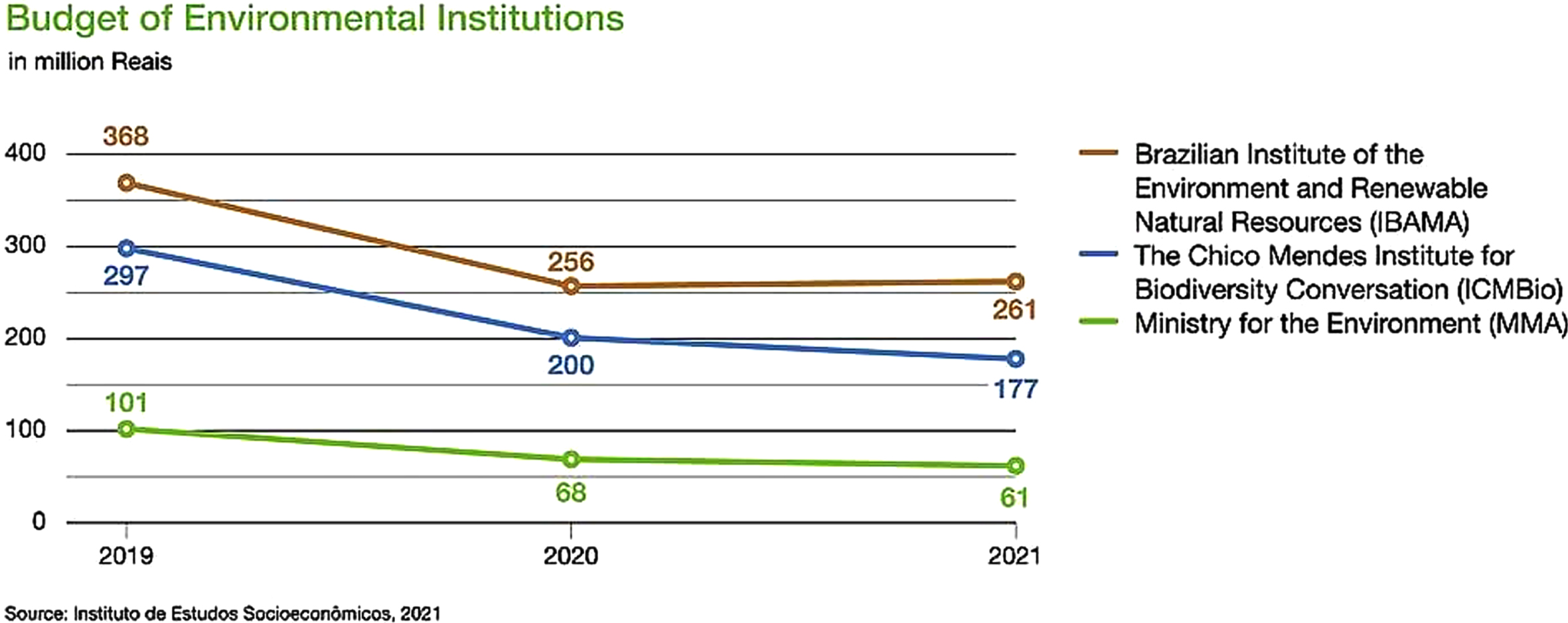

3.2Underfunding of the environmental agencies

It is estimated that the future administration that will take over in year 2023 will change the situation with the increase of the presence of police forces in the region. However, it should be noted that Brazil will need strong support and international funding, as the country’s fiscal situation is very complicated. During the Bolsonaro Administration, environmental protection policies received only 0.03% of the BRL 6.8 trillion to be disbursed (Fig. 4) under the 2020-23 Pluriannual Plan (PPA).13 Although it is true that the Environment Ministry and other government agencies have historically been underfunded and faced great challenges in fulfilling their roles, the cuts made since year 2020 have worsened the situation and made it extremely hard to meet major targets14.

Fig. 4

Budget of Environmental Institutions.

3.3The Funding of The Environmental Agencies and The International Cooperation

In Brazil, the administrative history of environmental monitoring began with the Special Secretariat for the Environment (Sema), created in 1973 (Decree No. 73,030/1973), which became the Ministry of the Environment (MMA) in year 1992. The former ministry changed its name to Ministry of Environment and Legal Amazon; in year 1995. It was further transformed into the Ministry of the Environment, Water Resources, and the Legal Amazon, later adopting the name of Ministry of Urban Development and the Environment. In year 1999, it assumed the old name of Ministry of the Environment, maintaining it until today.15

Now it is time to examine the possibilities of an U.S. - Brazil cooperation to combat climate change. Certainly, each of the two countries has something to learn from the other. Brazil and the United States hold constitutional systems that have some similarities and dissimilarities. The issue of climate change allows us to understand the existing differences. Both countries are federations, however, the federative models are quite different. The United States adopts a centrifugal model of federation, that is, the power is more rooted in the States and not in the Union; Brazil, on the other hand, is a federation with a very large centripetal shape, with the Union being the core of the system. The differences are very clear in recent SCOTUS decisions,16 when compared with the Brazilian Supremo Tribunal Federal [STF] rulings.

In noteworthy developments, the United States Supreme Court decided, among others, the case of West Virginia et al. v. Environmental Protection Agency et al. Similarly, the Federal Supreme Court (STF) ruled on the freezing of the Climate Fund by the federal government. In Brazil, the courts stress that the Federation has the legal power to establish a national minimum standard of environmental protection, in order to ensure that throughout the country, its citizens have the right to a certain degree of equality regarding environmental quality. This is not the case in U.S, where SCOTUS decided the States have the power to fix standards, which, in my opinion, creates serious barriers to a nation wide equal protection of the environment and is an incentive to a race to the bottom.

The lessons to be learned are that we cannot face global problems such as climate change without broad policies that coordinate the different levels of governance. The Court plays a pretty much pivotal role in this matter. A lack of understanding on how environmental issues work can be detrimental and the courts should be aware of it. As a result, the courts may play a good or a bad role, depending on its ability to understand the role of the rule of law in such a new and challenging situation created by global warning. It is unrealistic to face twenty-first century problem with the thoughts in eighteen centuries. Environmental Law is about looking ahead, not in the rear view.

Global issues such as global climate change need international cooperation and Brazilian Environmental Law is open to it and the cooperation shall grow in the next few years. International cooperation is fundamental for the development of protection and sustainable use of the different Brazilian biomes and, specially, of the Amazon. The various multilateral environmental agreements recognize that countries have common but differentiated responsibilities regarding the protection of biological diversity, e.g., Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).17 Articles 5 and 18 of the CBD establish that the Member States must cooperate to conserve biological diversity, including in the technological and scientific field.18 It is not unknown that the implementation of the cooperation mentioned in the conventional text requires the existence of financing mechanisms, as Articles 2019 and 2120 created financial mechanisms for the implementation of the CBD. However, such financial mechanisms are far from meeting the real needs for resource transfers so that developing countries can comply with the Convention.

However, it is important to note that the Decade of Biodiversity (2011-2020), which was summarized by the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, ended without any of its objectives being achieved.21 The financial mechanism for the maintenance of biological diversity is infinitely lower than the amounts allocated to the execution of projects that are potentially harmful to the environment and biological diversity. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) agreed upon at the CBD COP 15 (Montreal; December 7-19, 2022) sought (Target 18) to “identify by 2025 eliminate, phase out or reform incentives, including subsidies, harmful for biodiversity” and “progressively reducing them by at least $500 billion per year by 2030”. Moreover, the GBF (Target 19) called for implementation of the “national biodiversity strategies and action plans, mobilizing at least $200 billion per year by 2030”.22 A Special Trust Fund will support the implementation of the GBF.

Brazilian Environmental Law has space for international cooperation, especially within the Amazon Fund. It is important to note that a international cooperation, in this case, does not imply the loss of national sovereignty. In terms of financing activities, questions raised about the Bolsonaro administration by the fund’s main donors for example Norway and Germany, lead to a paralysis of its activities. The main issue was the modification made to the Fund’s Management Committee. The issue was taken to the STF, which has decided sixty days deadline to the government to make the Fund work again. The National Bank of Social and Economic Development (in Portuguese, BNDES) is the manager of the Amazon Fund, created in 2008 to raise donations earmarked for non-refundable investments in preventing, monitoring and combating deforestation, in addition to the conservation and sustainable use of the Amazon biome forests.23 The Amazon Fund’s main purpose is to promote the protection of this heritage and the sustainable development of the area. In addition to managing the Fund, the BNDES raises funds and selects projects, as well as monitoring progress after they have been contracted. Projects are supported in areas such as: public forest management and protected areas; control and monitoring, as well as environmental inspection; sustainable forestry management; and economic activities developed from the sustainable use of the forest. A full report of the Amazon Fund work in 2021 is available at Fund‘s website.24

Brazil is part of the main existing multilateral environmental agreements that have been incorporated into Brazilian Law through domestic rules on the issues. International cooperation, in the Brazilian constitutional regime, is one of the principles that guides its international relations. Thus, in summary, it is possible to affirm that international cooperation is an important factor in the construction of Brazilian environmental law and, certainly, there is an enormous potential for growth. Finally, it is important to emphasize that Brazilian environmental law has been able to appropriate the contributions arising from international cooperation and give them a national version to comply with the Brazilian reality.

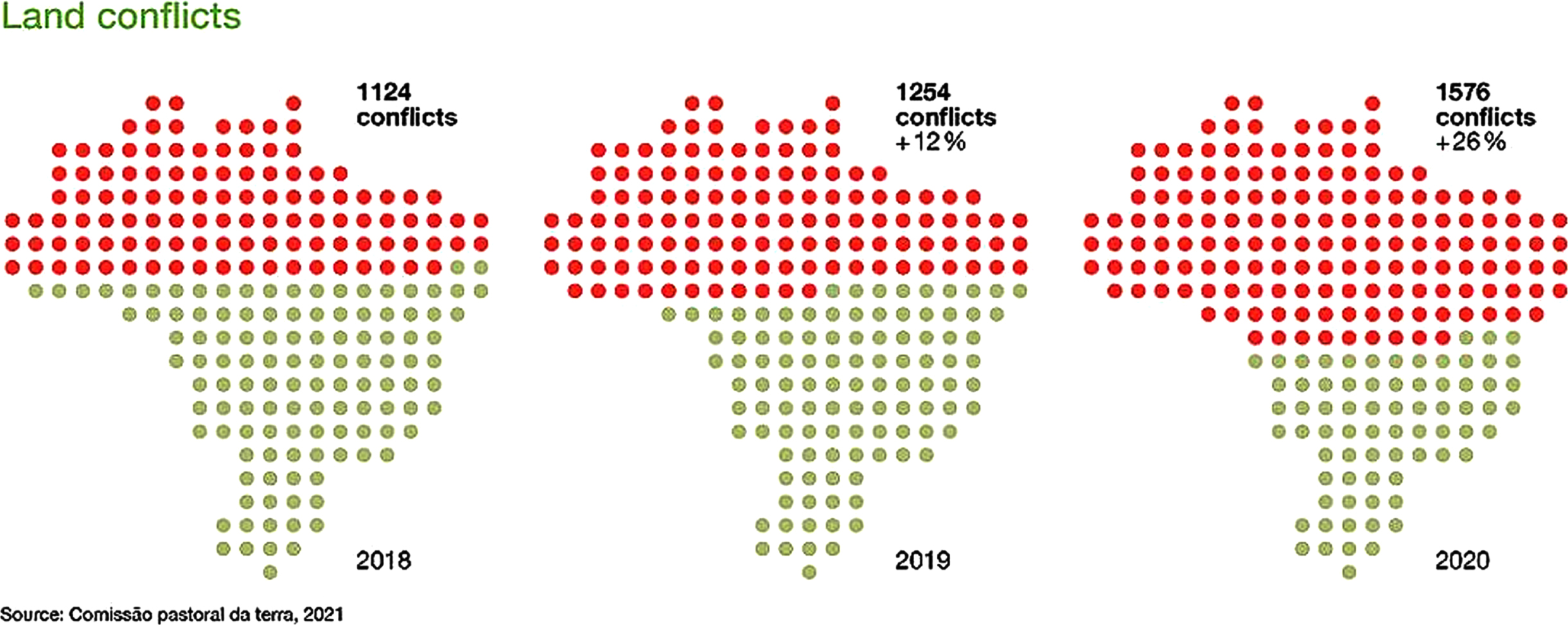

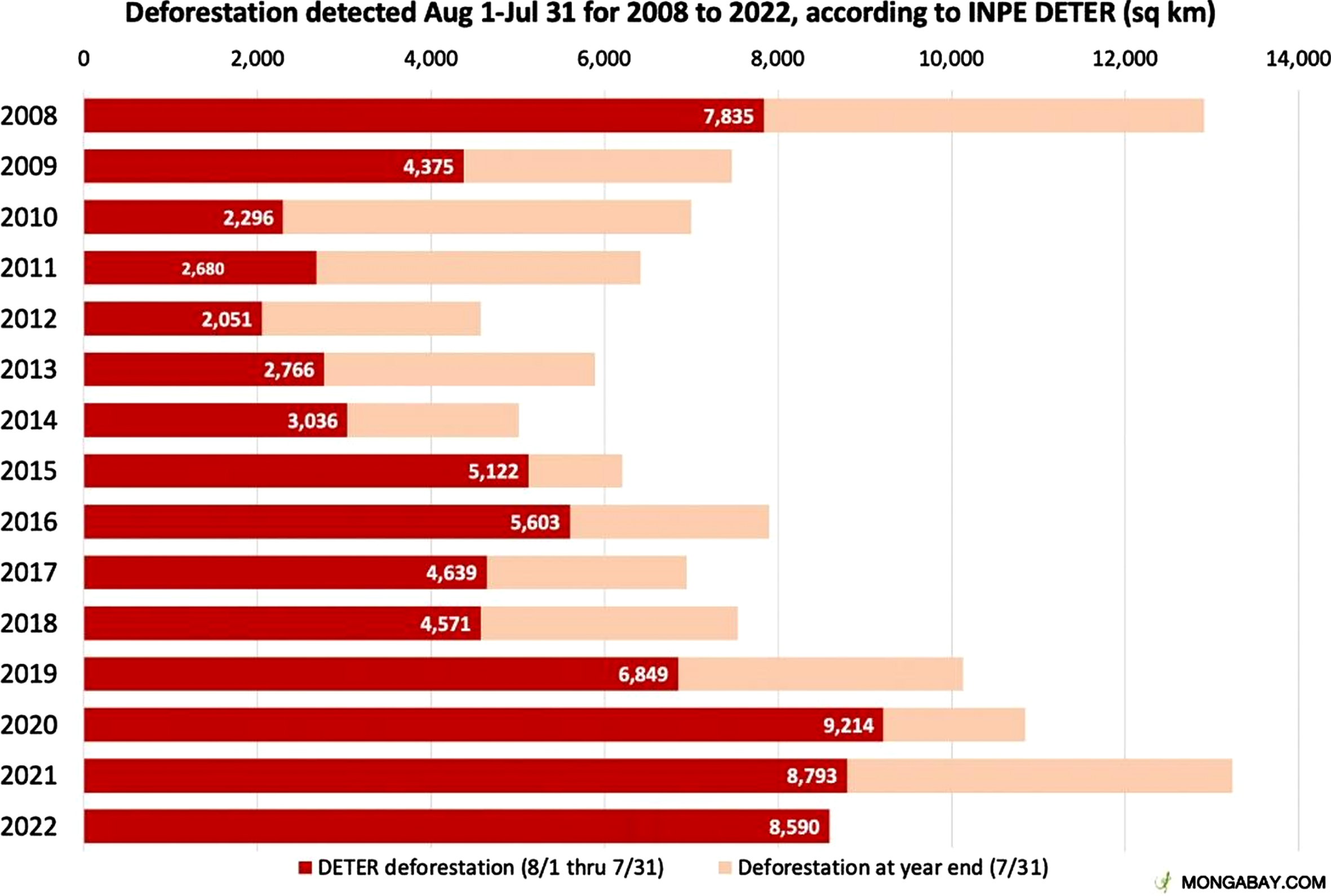

4Tackling Deforestation

The challenges ahead if we want to enact strong policies to combat climate change. But, imminent challenges are part of the daily life of Brazilians. Deforestation is number one (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Deforestation (Source: https://news.mongabay.com/2022/08/amazon-deforestation-on-pace-for-near-record-year).

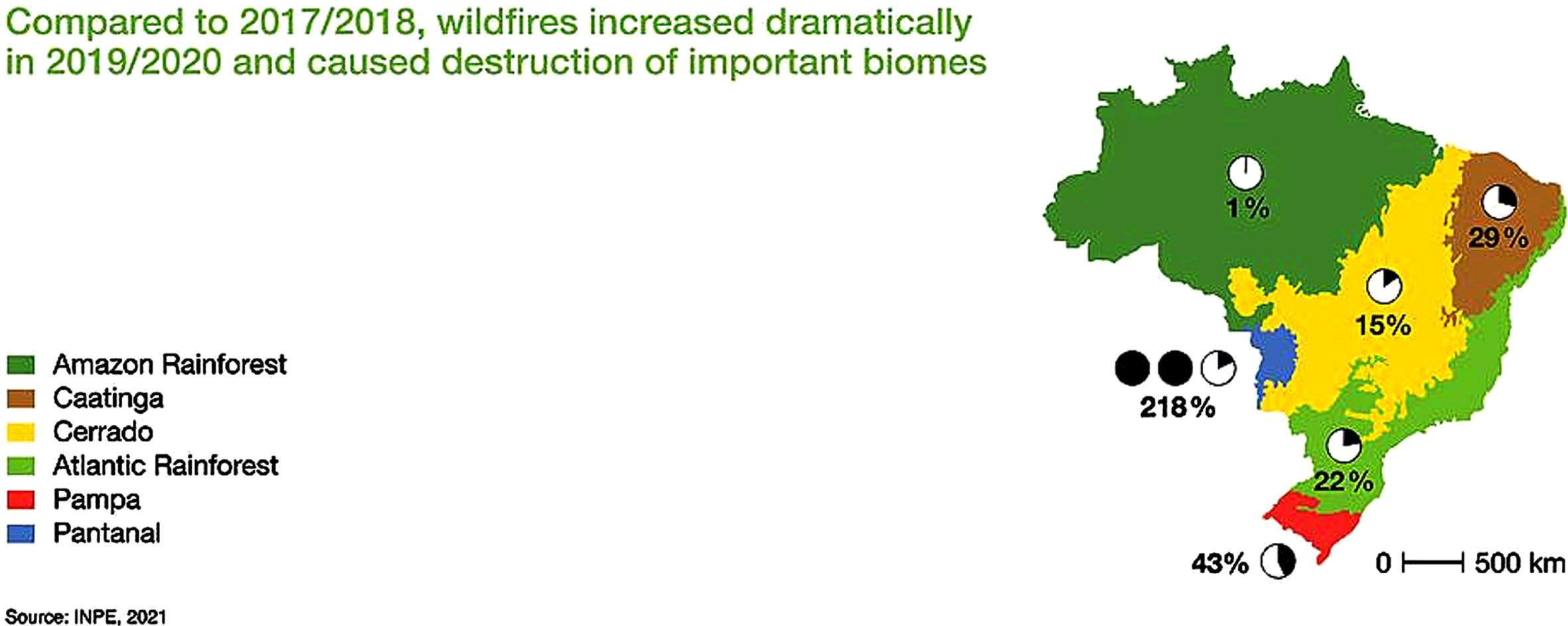

Containing deforestation is the main Brazilian challenge regarding climate change. The emission of GHGs in Brazil due to deforestation is enormous. It increased during the pandemic as well as due to rise in wildfires (Fig. 6). It is paradoxical, because during the pandemic the global emission of greenhouse gases have decreased.25 The top ten cities that emit the most GHGs in Brazil are responsible for higher emissions than Peru. It is surprising that seven of these cities are in the Amazon, according to a survey carried out by the Climate Observatory.26 According to the survey, the municipality with the highest emission in Brazil is São Félix do Xingu, in the State of Pará, with 29.7 million gross tons of CO2e in 2018. Of this total, land use changes mostly from deforestation, accounts for 25.44 million tons, followed by agriculture and cattle ranching, accounting for 4.22 million tons of CO2e, emitted mainly from cattle digestion. The municipality located in the State of Pará, has the largest number of cattle in the country. And if it were a country, São Félix do Xingu would rank 111th in the world in emissions, ahead of Uruguay, Norway, Chile, Croatia, Costa Rica, and Panama according to data from (CAIT), the World Resources Institute’s global emissions ranking.

Fig. 6

Wildfires.

Deforestation also causes the per capita emissions of the Amazon municipalities to skyrocket. Each resident of São Félix do Xingu, for example, emits 225 tons of CO2e per year, almost twenty two times more than the average gross emissions per capita in Brazil, twelve times more than in the United States, and six times more than in Qatar, the country with the highest per capita emissions in the world. Colniza, in northwest of the State of Mato Grosso, is even worse off as the sixth largest emitter in the country, with 14.3 million tons of CO2e emitted in year 2018. Colniza has the highest gross per capita emissions in Brazil, at 358 tons. This level of emission is equivalent to each inhabitant of the municipality owning more than 300 cars and driving 20 kilometers per day.

The same survey also brings good news, for instance: the finding that extensive Amazonian municipalities with many protected areas also have large GHG removals. This reduces so-called net emissions. The champion of emissions removal is Altamira, the largest municipality in Brazil by area, which has removals of more than 22 million tons of CO2 . The report clearly demonstrates the role that deforestation plays in the emission of GHGs in Brazil, which takes us back to the issue of international cooperation, as many economic, technical, and institutional resources are needed to tackle the problem. Finally, it is fair to demonstrate that deforestation is not restricted to the Amazon.

5The Brazilian Legal Framework and Institutions

From a legal point of view, Brazil has a set of regulations that is quite adequate to address the issues mentioned above, e.g., National Policy on Climate Change, various State and Municipal Policies on Climate Change, National Solid Waste Policy, New Forestry Code and many others. However, in a country with so many social needs, the allocation of resources to face climate change is increasingly complex. It should be added that Brazil has started a process of regulation of the carbon market, which, however, depends on the advances made in international negotiations, without which it is not feasible.

Brazil is one of the pioneer countries when it comes to imagining and creating the conditions to ensure a sustainable future for our planet and the people who inhabit it. Brazilian society is committed to sustainability for the planet. Fortunately, we were able to take fundamental steps to overcome a recent past in which the basic values of environmental protection were largely neglected by public authorities whose role was to protect it and the traditional communities and indigenous peoples who are the spearheads of the defense of the environment. Fortunately, Brazilian environmental law, judicial activism and the firm action of society prevented unimaginable setbacks from being established.

The Brazilian constitutional model and the ordinary legislation, articulated with civil society, allowed that fundamental values of our society regarding environmental protection were preserved. Brazilian society proved to be resilient in the stress test to which it was subjected.

IBAMA’s role needs to be rethought, as its structures are insufficient and it is completely unrealistic to think that simply expanding its staff will be able to solve structural problems. Its transformation into an agency, with the Board of Directors appointed by the President Republic and approved by the Senate, in principle, can guarantee the independence of the body, and measures must be foreseen to prevent the famous “revolving doors". The number of commission positions accessible to non-staff must be drastically reduced, preferably eliminated. Strengthening structures in the Amazon, including the possible installation of the agency in the region, as is the case with the National Petroleum Agency (ANP), in Rio de Janeiro.

6The Global Perspectives

The prospects for the future are good. There is growing international awareness of the Amazon’s role in the global climate agenda. However, such awareness must materialize in financial resources and technology transfer. The Convention on Biological Diversity is quite clear on the issue. The administration taking office in year 2023 enjoys international goodwill, which is an important start. However, goodwill alone is not enough to face the enormous Amazonian problems.

The respect of the territorial rights of indigenous peoples and traditional populations is essential for protecting the forest and, consequently, the global climate system. Reducing deforestation and burning is a need that can be achieved with the necessary effort. Information about the main deforestation and fires is available, as well as the necessary technology to map the situation in detail. It is also necessary to improve urban conditions in the Amazon, ensuring decent living conditions for city populations.

Reducing fires in the Amazon is possible, as it has been done in the past. In this new stage, it will be necessary to use new instruments, including those of a financial nature. Preventing the circulation of money generated by deforestation and fires is the main task to be carried out by the tax, police and judicial authorities. However, there is a need to look to the future. The simple reproduction of what was done in the past will not be able to solve the present problems.

About the land regularization of Conservation Units (UC), it is necessary to look at the fruitful example of the Private Natural Heritage Reserves (RPPN), in which protection is carried out by private individuals, under public rules. The use of mechanisms such as usufruct, concession of use and others, could facilitate the regularization of many UCs, including National Parks. Still in relation to the UCs, one of the first points that must be examined is the urgent need to expand the workforce of the National System of Conservation Units (in Portuguese, SNUC). In this matter, the initiatives are not very creative and are limited to public tenders for the recruitment of professionals, which has proven to be insufficient, or to environmental volunteers, whose legality is problematic. The involvement of society, nationally and internationally, in Amazonian issues is essential, as without such support, no government will be able to carry out the great tasks that lie ahead.

7Conclusion

The period between 2019 and 2022 will be remembered as one of the worst periods in the history of Brazilian environmental institutions. The dismantling of environmental protection structures was a deliberate policy whose negative results are evident. The reversal of such a policy is urgent and necessary. There are immense possibilities that could be availed on an urgent basis. The choices to be made by the new administration of President Lula da Silva that took over on January 01, 202328 will be decisive for the future of the Brazilian indegenous peoples and the Amazon. The right choices would herald a new era for the Amazon and the rights of the people therein.0

Notes

1 Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Natural Resources (IBAMA) – Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis,; more dtails avilable at: http://www.abc.gov.br/training/informacoes/InstituicaoIBAMA_en.aspx

2 Chico Mendes Institute for the Conservation of the Biodiversity (ICMBio), Instituto Chico Mendes para a Conservação da Biodiversidade, more details avilable at https://www.gov.br/icmbio/pt-br.html

3 Rhett A. Butler (2020), The Amizon Rainforest: The World’s Largest Rainfroest (4 June, 2020); avilable at: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon.html. Also see, Largest River Drainage Basins Worldwide as of 2021 (March 2021); available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1221316/ten-largest-river-basin-worldwide/.html

4 Ibid.

5 The Amazon Cooperation Treaty (1978), It is legal instrument which recognizes the trans-boundary nature of Amazon River Basin signed by eight countries on 3 July, 1978. France (French Guyanna) is not a part of this treaty now; avilable at: http://otca.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Amazon-Cooperation-Treaty.pdf

6 Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (2003), Understanding the Importance of the ACTO (March, 2003); available at: http://www.otca.org/en/about-us.html

7 Legal Amazon means the area referred in Decree-Law No. 5,173 of October 27, 1966 and Article 45 of Complemental Law No. 31 of October 11, 1977 for governmental planning purposes. More description available at https://www.ibge.gov.br/en/geosciences/environmental-information/geology/17927-legal-amazon.html

8 IMAZON, The State of Amazon (March 2023); available at https://imazon.org.br/en/categorias/the-state-of-amazon.html

9 Sarah Brown (2022), Organized Crime drives Violence and Deforestation in the Amazon: A Study Shows (1 August, 2022); available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2022/08/organized-crime-drives-violence-and-deforestation-in-the-amazon-study-shows.html

10 Ali Hynes (2022), Decade of Defiance: Ten Years of Report in Land and Environmental Worldwide, Global Witness (29 September, 2022), available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/last-line-defence.html

11 Connect as Human Right, Brazil is the Country that most kills land activists, according to report by Global Witness, News (10 November, 2022) available at https://www.conectas.org/en/noticias.html

12 Edureda Campos Lima (2021), Indigionous Death in Brazialian Land Disputes Skyroket in 2021, (2 March, 2022), avilable at https://cruxnow.com/church-in-the-americas/2022/05/indigenous-deaths-in-brazilian-land-disputes-skyrocket-in-2021.html. Also see, Hoddy, Eric T., “Transformative Justice in Practice: Reflections on the Pastoral Land Commission during Brazil’s Political Transition”, Journal of Human Rights Practice, p. 343, 339-356 2022); available at: Transformative Justice in Practice: Reflections on the Pastoral Land Commission during Brazil’s Political Transition — York Research Database

13 Regional Observatory of Planning for Development in the Lain America and the Caribbean, Brazil (2019): National Development Plan 2020-23; Projection of Expenditures of the Federal Government; available at: Plano Plurianual - PPA 2020-2023 do Brasil | Regional Observatory on Planning for Development (cepal.org)

14 Suely Mara Vaz Guimarães de Araujo (2020), Environmental Policy in the Bolsonaro Government: The Response of Environmentalists in the Legislative Arena, 14 (2) Bras. Pol.Sci. Rev. 2 (2020); available at: https://www.scielo.br/j/bpsr/a/BvykxZmxfgSHpTKj67jSmfQ/?lang=en.html

15 O-ECO (2015), What does the Ministry of Enviornment do in Brazil?; available at: https://oeco.org.br/dicionario-ambiental/28419-o-que-faz-o-ministerio-do-meio-ambiente.html

16 Paulo de Bessa Antunes (2022), The US Supreme Court and Cliamt Change, A Suprema Corte dos Estados Unidos e as mudanças climáticas, (9 July, 2022), available at https://www.conjur.com.br/2022-jul-09/paulo-bessa-suprema-corte-eua-mudancas-climaticas.html

17 Convention on Biological Diversity, 1760 UNTS 79; 31 ILM 818 (1992), Article 3. Principle States have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law, the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.

18 Ibid. Article 18 - 1. The Contracting Parties shall promote international technical and scientific cooperation in the field of conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, where necessary, through the appropriate international and national institutions. 2. Each Contracting Party shall promote technical and scientific cooperation with other Contracting Parties, in particular developing countries, in implementing this Convention, inter alia, through the development and implementation of national policies. In promoting such cooperation, special attention should be given to the development and strengthening of national capabilities, by means of human resources development and institution building. 3. The Conference of the Parties, at its first meeting, shall determine how to establish a clearing-house mechanism to promote and facilitate technical and scientific cooperation. 4. The Contracting Parties shall, in accordance with national legislation and policies, encourage and develop methods of cooperation for the development and use of technologies, including indigenous and traditional technologies, in pursuance of the objectives of this Convention. For this purpose, the Contracting Parties shall also promote cooperation in the training of personnel and exchange of experts. 5. The Contracting Parties shall, subject to mutual agreement, promote the establishment of joint research programmes and joint ventures for the development of technologies relevant to the objectives of this Convention.

19 Ibid, Article 20. Financial Resources 1. Each Contracting Party undertakes to provide, in accordance with its capabilities, financial support and incentives in respect of those national activities which are intended to achieve the objectives of this Convention, in accordance with its national plans, priorities and programmes. 2. The developed country Parties shall provide new and additional financial resources to enable developing country Parties to meet the agreed full incremental costs to them of implementing measures which fulfil the obligations of this Convention and to benefit from its provisions and which costs are agreed between a developing country Party and the institutional structure referred to in Article 21, in accordance with policy, strategy, programme priorities and eligibility criteria and an indicative list of incremental costs established by the Conference of the Parties. Other Parties, including countries undergoing the process of transition to a market economy, may voluntarily assume the obligations of the developed country Parties. For the purpose of this Article, the Conference of the Parties, shall at its first meeting establish a list of developed country Parties and other Parties which voluntarily assume the obligations of the developed country Parties. The Conference of the Parties shall periodically review and if necessary amend the list. Contributions from other countries and sources on a voluntary basis would also be encouraged. The implementation of these commitments shall take into account the need for adequacy, predictability and timely flow of funds and the importance of burden-sharing among the contributing Parties included in the list.

20 Ibid, Article 21. Financial Mechanism 1. There shall be a mechanism for the provision of financial resources to developing country Parties for purposes of this Convention on a grant or concessional basis the essential elements of which are described in this Article. The mechanism shall function under the authority and guidance of, and be accountable to, the Conference of the Parties for purposes of this Convention. The operations of the mechanism shall be carried out by such institutional structure as may be decided upon by the Conference of the Parties at its first meeting. For purposes of this Convention, the Conference of the Parties shall determine the policy, strategy, programme priorities and eligibility criteria relating to the access to and utilization of such resources. The contributions shall be such as to take into account the need for predictability, adequacy and timely flow of funds referred to in Article 20 in accordance with the amount of resources needed to be decided periodically by the Conference of the Parties and the importance of burden-sharing among the contributing Parties included in the list referred to in Article 20, paragraph 2. Voluntary contributions may also be made by the developed country Parties and by other countries and sources. The mechanism shall operate within a democratic and transparent system of governance. 2. Pursuant to the objectives of this Convention, the Conference of the Parties shall at its first meeting determine the policy, strategy and programme priorities, as well as detailed criteria and guidelines for eligibility for access to and utilization of the financial resources including monitoring and evaluation on a regular basis of such utilization. The Conference of the Parties shall decide on the arrangements to give effect to paragraph 1 above after consultation with the institutional structure entrusted with the operation of the financial mechanism. 3. The Conference of the Parties shall review the effectiveness of the mechanism established under this Article, including the criteria and guidelines referred to in paragraph 2 above, not less than two years after the entry into force of this Convention and thereafter on a regular basis. Based on such review, it shall take appropriate action to improve the effectiveness of the mechanism if necessary. 4. The Contracting Parties shall consider strengthening existing financial institutions to provide financial resources for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity.

21 Herton Escobar (2020), Decades of Biodiversity End with No Goal Met (17 August, 2020), USP Journal News; available at: https://jornal.usp.br/atualidades/decada-da-biodiversidade-termina-sem-nenhuma-meta-cumprida.html

22 CBD (2022), Decision 15/4. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework; Conference Of The Parties To The Convention On Biological Diversity, Fifteenth meeting – Part II Montreal, Canada, 7-19 December 2022; CBD/COP/DEC/15/4 19 December 2022; available at: 15/4. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (cbd.int)

23 Brazil Deree No. 6.527 (2008), Creation of Amozan Fund established by the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES), avilable at https://www.ecolex.org/details/legislation/decree-no-6527-creating-the-amazon-fund-established-by-the-national-bank-for-economic-and-social-development-bndes-lex-faoc136583.html

24 National Bank for Economic and Social Development (2021), Amazon Fund Activity Report 2021, (31 December, 2021); avilable at: Home (amazonfund.gov.br)

25 NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2021), “Emission Reductions from Pandemic had Unexpected Effects on the Atmosphere”, Earth News (9 November, 2021); available at: Emission Reductions From Pandemic Had Unexpected Effects on Atmosphere (nasa.gov)

26 IPAM (2021), Amazonian Municipalities dominate Carbon Emissions in Brazil, News, (19 March, 2021); available at: https://ipam.org.br/amazonian-municipalities-dominate-carbon-emissions-in-brazil.html

28 Reuters (2023), “Lula takes over in Brazil, slams Bolsonaro’s anti-democratic threats”, January 02, 2023; available at: Lula takes over in Brazil, slams Bolsonaro’s anti-democratic threats | Reuters

27 Map Biomes Alerts (2021), Overview of Biomes and Brazil Deforestation in 2021 (March, 2021); available at: MapBiomas Alerta. (Source: MapBiomas Alert).