Planetary Boundaries Nurturing the Grand Narrative of the Right to a Healthy Environment?

Abstract

The profound changes in Earth systems dynamics are affecting the health of the entire planet and the realization of a broad range of human rights. In this paper, we propose that the grand narrative of human rights including the legal right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment recognized by the United Nations in 2022 requires the acknowledgment of the interconnected challenges posed by planetary crises. We discuss how planetary boundaries (PB) research can provide evidence-based arguments and clarify State duties concerning their international human rights law commitments. The economic, social and cultural rights are deeply connected with the right to a healthy environment. Human rights to water, food, or health, for example, can all be understood in the context of Earth systems change. Civil and political rights go beyond individuals to include also collective action and participation to tackle planetary social-ecological challenges. Gaps remain in human rights law concerning some of the PBs, which risks overlooking the interconnected drivers of ecosystem degradation. Clearer legal standing and justification for legal demands, for example concerning the impacts of water use, land use and deforestation, are needed to tackle PB overshoot. States must act at various spaces including the global economic systems and the global supply chains of goods and services for humanity to reach planetary safe and just spaces. Weaving international human rights law and advances at various geographical scales on the right to a healthy environment with PB provides a powerful tool for defending the prerequisites of good life for everyone, everywhere.

1Introduction

The realization of human rights presents a vision and a goal for societal transitions, the “highest aspiration”1. While texts of UN human rights treaties (International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ICCPR or International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, ICESCR) do not include a right to a healthy environment, UN human rights treaty bodies and the UN General Assembly have increasingly clarified human rights obligations in the context of the environment. In 2022, the UN General Assembly recognized the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment2 building on UN Human Rights Council Resolutions in 2021 also recognizing this right3 and the need to address the interconnections between biodiversity loss, climate change and disaster risk reduction4. The broad recognition of the right to a healthy environment cannot be timelier considering contemporary Earth Systems dynamics.

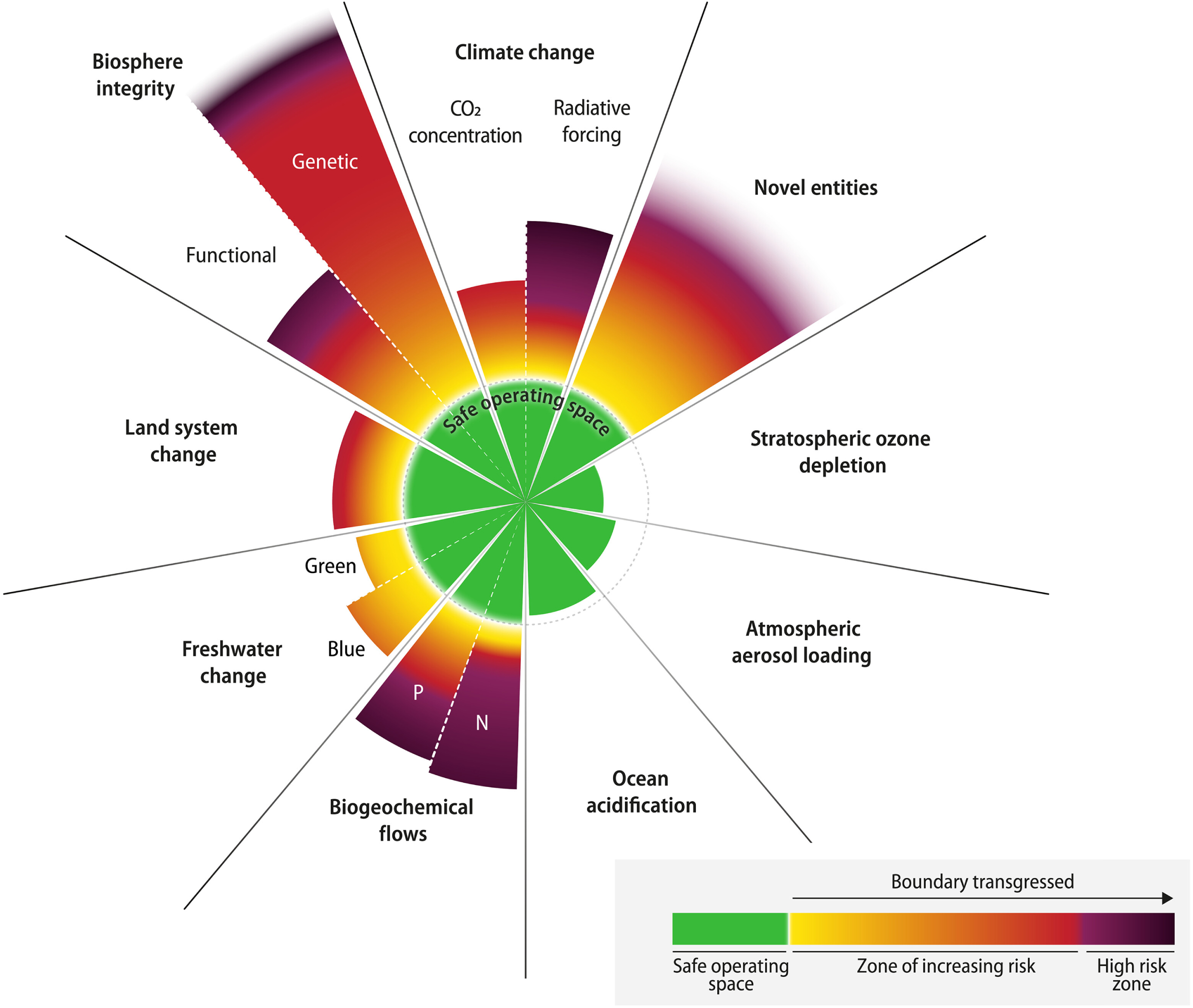

The planetary boundaries, also called Earth system boundaries, are planetary subsystems or processes with associated bio-physical boundaries and together form a so-called ‘safe operating space’ in which humanity can thrive and develop.5 Transgressing the boundaries leads to abrupt and undesirable environmental change. The nine planetary boundaries are novel entities, climate change, biosphere integrity (genetic and functional), land system change, freshwater change, biogeochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus loadings), ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol loading, and stratospheric ozone depletion. The six boundaries mentioned first have already been transgressed with increased transgression levels since 2015, and the ocean acidification boundary is close to being transgressed.6

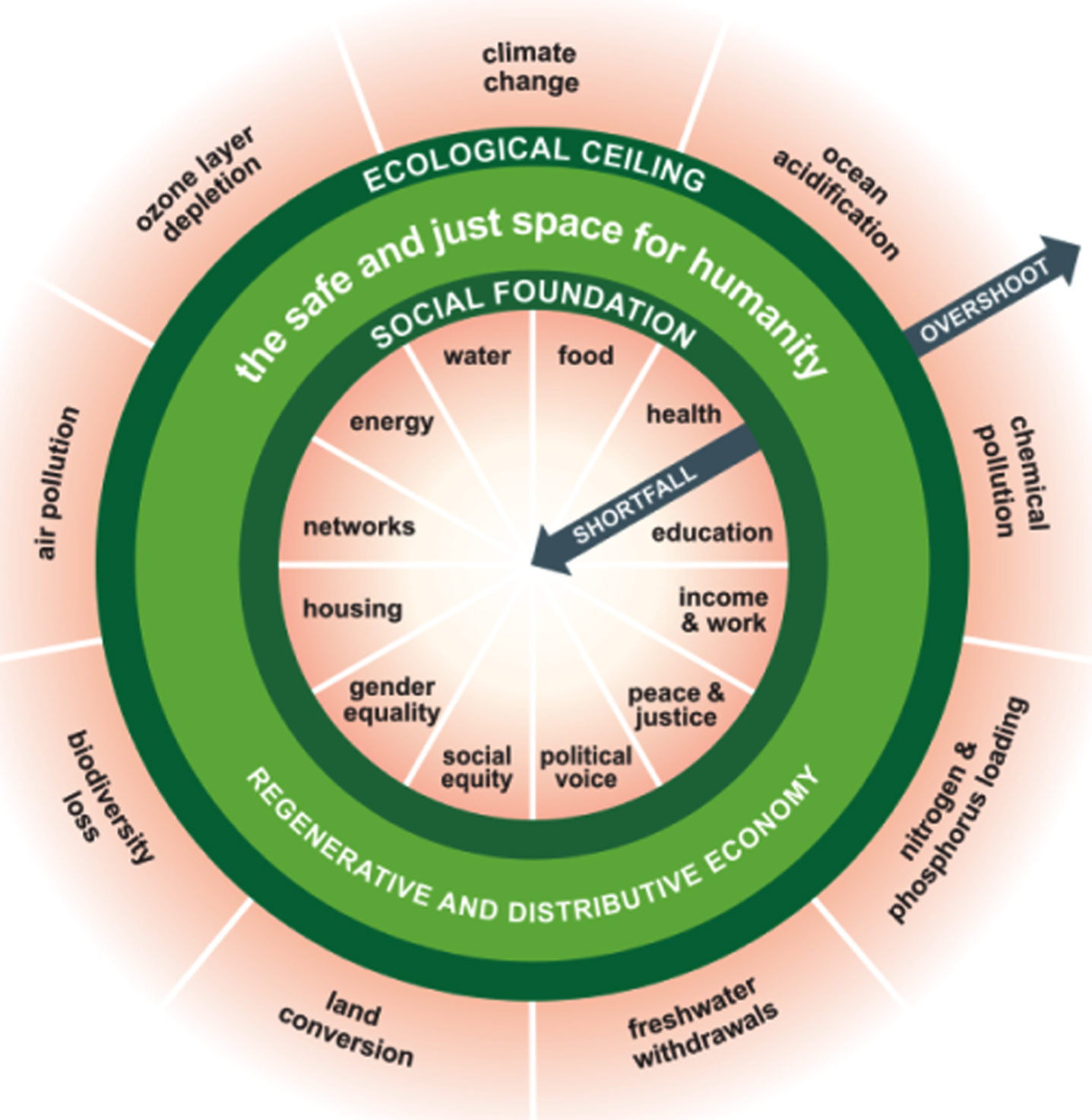

Based on planetary boundaries research, literature has evolved to include also social justice concerns. For example, the Doughnut economy model is a vision for sustainability transitions.8 The model sets environmental and social justice as equally important building blocks for the possibility for humanity to thrive. The Doughnut model’s inner boundary refers to everyone having energy, water, food, housing, health, education, income & work, peace & justice, political voice, gender equality, social equity, and networks.9 Together, the ecological and social boundaries define a ‘safe and just operating space’, where ‘safe’ means that the economic system should respect the planetary boundaries, and ‘just’ means it should promote human wellbeing and social justice. Turner and Wills10 recognize the need to downscale the global Doughnut model at national and subnational scales. We believe PB including the Doughnut model brings an opportunity to revitalize the human rights law narrative including the international and global dimensions of State obligations.

There is emerging research on ‘planetary justice’12 and ‘earth systems law’13 as well as the call of Ensor and Hoddy14 to take a rights-based approach to planetary boundaries. Ebbesson15 showed how conflicts and distributive effects within the boundaries need to be considered in connection with international treaties regimes.

We aim to fill some gaps in understanding PB and human rights relations by examining whether and how PB can provide clarity for human rights obligations and whether and how PB can in turn enrich the human rights vision in depicting the simultaneous and systemic dynamics involved. Rockström et al.16 argue that rather than linear processes, a leap is required in our understanding of how justice, economics, technology, and global cooperation interact for safe and just spaces. A systemic approach means tackling complex dynamics between economic, technological, political, and other drivers of Earth System change that affect access to and use of resources by people living in poverty situations.

Through highlighting the biophysical boundaries of the planet, PB research including the Doughnut model can shift the attention towards tackling the root causes that hinder the enjoyment of human rights of present and future generations. Human rights law, in turn, can specify the content but specifically strengthen the normative nature of the boundaries and the Doughnut through its instruments and mechanisms that allow individuals and groups to present demands to States and courts and tribunals to force action bringing evidence including scientific evidence when accessing justice at various jurisdictional scales.

Thus, we suggest that combining PB with the right to a healthy environment gives a possibility to produce a comprehensive, science-based, and normative narrative that makes transition to a safe and just space a duty for States. The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 asks whether PB can contribute to clarify States rights-based duties concerning the inner boundary of the Doughnut model. Section 3 examines the outer boundary. Section 4 presents conclusions on PB contributing to strengthening human rights law for humanity’s transitions towards a safe and just space.

2The Legal Duty to Move to the Just Space

In this section, we discuss the extent to which PB can help nurture a grand narrative where the right to a healthy environment forms the basis also for the enjoyment of just space rights.

Most of the ‘just space’ items are recognized as international human rights, which generate legally binding obligations on States who have ratified them, i.e., most UN member States. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, 1966) recognizes that everyone has the right to life (Article 6). Article 12(1) establishes “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”. ICESCR (1966) also defines the rights to “food, clothing, and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions” (Article 11). In 2010, the UN General Assembly recognized the right to water and sanitation as a stand-alone right and as essential to the realization of all human rights.17 Universal access to modern energy services can also be interpreted as a prerequisite to the realization of human rights,18 and digitalization may invite recognition of internet access as a right if it is in practice required for accessing public and private services as well as administrative processes and hence access to justice.19 Rights concerning education (ICESCR Article 13.1) and participation in cultural life (Article 15(1)(a)) are likewise important in the just space. The realization of ‘just space’ has advanced for example concerning children’s nutrition and education.20 Yet, major setbacks in the enjoyment of human rights are linked to global dynamics such as limited access to basic goods caused by the pandemic21 and risks of a global food and energy crisis exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.22

Continuously increasing resource-intensive consumption is not a human right.23 The PB perspective shows us that overconsumption is in fact in stark contrast with human rights. No country has yet found a space that is both just and safe. The poorest countries cannot fulfill the economic, social and cultural rights of their citizens and inhabitants (not yet reaching the social foundation, the inner boundary), and high and middle-income countries have ecological footprints too large for the planet.24 USA is responsible for 27% of global excess material use, EU-28 for 25%, and China for 15%.25 Ecological limits can be seen as a fundamental requirement for all sustainable human activities, because of the life supporting ecosystem services. Countries exceeding the ecological ceiling threatening the possibilities of everyone to reach just space in the future.26 By setting the ecological limits as the outer boundary of the economy, the Doughnut model acknowledges the dependence of living beings including humanity on nature.27 This PB-based narrative has the potential of contributing to a deep-rooted shift in worldviews which is needed for sustainability transformations. Global North countries cutting their water, climate, and biodiversity footprints would be giant leaps towards a safe and just space and towards the realization of all human rights.28

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 1966) is the major legal instrument concerning democratic participation and political voice which converges with the inner boundary of the PB. Freedom of expression (Article 19.2) and freedom of association (Article 20) are vital for empowering people to safeguard healthy ecosystems. Irene Khan (2023), the Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression and opinion, calls for a paradigm shift by looking at sustainable development through the lens of freedom of expression. She argues “leaving no one behind” involves both access to information held by State institutions and businesses as well as the ‘right of voice’ and public participation in legal and policy processes.29 Procedural environmental rights (access to environmental information, participation, and access to justice) defined in the Aarhus Convention (1998) and in the Escazu Agreement (2018) enable right-holders including biosphere defenders30 to demand the realization of their environmental rights.31

Fair equality of opportunity32 demands strict non-discrimination.33 According to Article 26 of ICCPR, all persons are equal before the law. The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1965), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (1979) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006) are other major agreements concerning equality and non-discrimination. Concerning the specific rights of indigenous peoples, the major legal text is the ILO Convention 169 (1989) which includes economic, socio-cultural, and political rights, including the right to a land base. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989) applies to all human beings under the age of 18 years. “In all actions concerning children ... the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration” (CRC Article 3.1.). Right to work and workers’ rights are central in economic systems, and they are governed by Articles 6, 7 and 8 of the ICESCR. In addition, ILO governs eight central Conventions on worker’s rights (between 1948 to 1999). The conventions cover freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of forced labor, the abolition of child labor, and the elimination of working life discrimination. In practice, the realization of workers’ rights is still a major challenge with forced labor and dangerous working conditions persisting.34

Weaving the just space of the Doughnut model with international human rights law raises questions on defining who has property rights, what is their content, and how they are balanced against other rights. Private property rights are a major building block of the currently dominant economic system in which property rights are seen to enable individuals to pursue activities to their own subjective ends.35 Strong property rights particularly of large multinational companies concerning land, water distribution, electricity grids, and plant varieties may raise human rights concerns associated with the right to water and sanitation, right to housing, and right to food. From another perspective, the land and water rights of indigenous groups36 and women37 are vital for securing income and livelihoods in a just and equal manner. Beyond a narrative centered on the argument that others cannot interfere in one’s property, and one cannot interfere in the property of others, the PB can help strengthen the case for a social-ecological and human rights-based understanding of right to property. While the UN agreements (ICCPR and ICESCR) do not recognize the right to property, several regional human rights conventions and national constitutions do.38 For example, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has elaborated the content of property rights under the American Convention of Human Rights to include both tangible dimensions associated to land and the direct dependence of livelihoods on ecosystems as well as intangible dimensions such as cultural legacy and the right to transmit this legacy to future generations.39

To avoid letting one societal goal overshadow all others, emphasizing individual rights and State responsibilities as critical components of the safe and just space is important. Yet, beyond a narrow Global North human rights paradigm centered only in individual freedoms, inequality issues linked to planetary social-ecological crises need also to be at the core of a human rights paradigm in the 21st century.40 Wealthy influential states should listen and be responsive to the breadth of issues that Global South countries are seeking to raise via the UN multilateral system not least economic, social, cultural and environmental rights linked to Earth Systems dynamics. PB can nurture a narrative in which all international human rights as well as democracy and the rule of law are interdependent and mutually reinforcing.41

PB as a science-based health check of the processes that keep Earth in a resilient state can contribute to the narrative of a universal right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and to recognizing how many other human rights of current and future humans are interconnected with and dependent on that right.

After saying that ‘just space’ depends and relies on us reaching the ‘safe space’, the next section focuses on the specifics of the safe space.

3The Legal Duty to Move to the Safe Space

Unless cascading social-ecological risks with global dimensions are taken seriously, humanity may fall into an irreversible unstable state where the right to a healthy environment cannot be realized by present and future generations. PB can serve to strengthen evidence-based international human rights law about these types of risks. Profoundly changing the water cycle - the bloodstream of the biosphere - is affecting the health of the entire planet. The reassessed freshwater PB provides evidence concerning risks associated with “green water,” which is water in the form of rainfall, soil moisture and evaporation, and also show how this freshwater PB is tightly connected to other PB such as land use, biodiversity and climate.42 Research on such interconnections can provide stronger arguments for collective action at all levels to tackle challenges concerning water and sanitation, safe climate, and healthy biodiversity and ecosystems, i.e., the substantive elements of the right to a healthy environment.43

International human rights law has addressed certain issues covered by distinct PB. Although the PB has not been established as a human rights law framework, the following PB have been covered by the international human rights system to a certain extent: climate change,44 chemical pollution,45 freshwater withdrawals,46 land conversion,47 and biodiversity loss.48 Human rights law concerning these boundaries is thus relatively more elaborated than on the ozone layer PB, the ocean acidification PB, the nitrogen and phosphorus loading PB and the novel entities PB.

As mentioned, the climate change PB is relatively covered by human rights-based duties. For example, “failure to take measures to prevent ... human rights harm caused by climate change, or to regulate activities contributing to such harm, could constitute a violation of States’ human rights obligations ... states must adopt and implement policies aimed at reducing emissions”.49 Climate change and the rights of the child are the topic for the UN Human Rights Committee 2017 study50 and in 2023, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child launched its general comment No. 26 on children’s rights and the environment, with a special focus on climate change.51 There is also a separate Human Rights Council resolution (2018) on women and girls52 that urges states to strengthen and implement policies that take gender-sensitive climate change actions.

The upcoming Advisory Opinion by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) will further delineate States’ obligations connected to the climate PB. Since 2019, the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change urged the campaign for the UN to seek ICJ opinion.53 Initiated by Vanuatu, the UN General Assembly adopted a consensus resolution in 2023 to request ICJ Advisory Opinion.54 Explicitly mentioned in the UN General Assembly resolution are the UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity as well as human rights treaties and the UN General Assembly (2022) resolution on the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment.

While human rights bodies set the standards of human rights duties in the context of climate change, the Paris Agreement (2015) serves as the substantive, global yardstick against which national actions are measured. In Duarte Agostinho et al. vs. Portugal and 32 Other Countries to be resolved at the European Court of Justice, Portuguese children and young people demand states to respect their right to life and to keep climate change within the 1.5-degree limit that is defined as the goal of the Paris Agreement. If the claimants are successful, the defendant countries will be legally bound not only to reduce emissions in their own country but also to tackle overseas impacts to climate change. In Neubauer et al. vs. Germany,55 the German court admitted complaints from German individuals and importantly also from individuals outside Germany. The German Constitution was interpreted as requiring Germany to be climate neutral, and the efforts towards this goal to be evenly distributed between generations.56

As with climate-related human rights, or perhaps even more clearly and directly, right-holders have human rights concerning ecosystems and biodiversity.57 The UN Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 3658 refers to the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992) as setting human rights duties for governments. As the UN Special Rapporteur states, all human rights ultimately depend on a healthy biosphere: ”Nature is the source of countless irreplaceable contributions to human well-being, including clean air and water, carbon storage, pollination, medicines and buffers against disease ... Everyone, everywhere, has the right to live in a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, a right which includes healthy ecosystems and biodiversity.”59

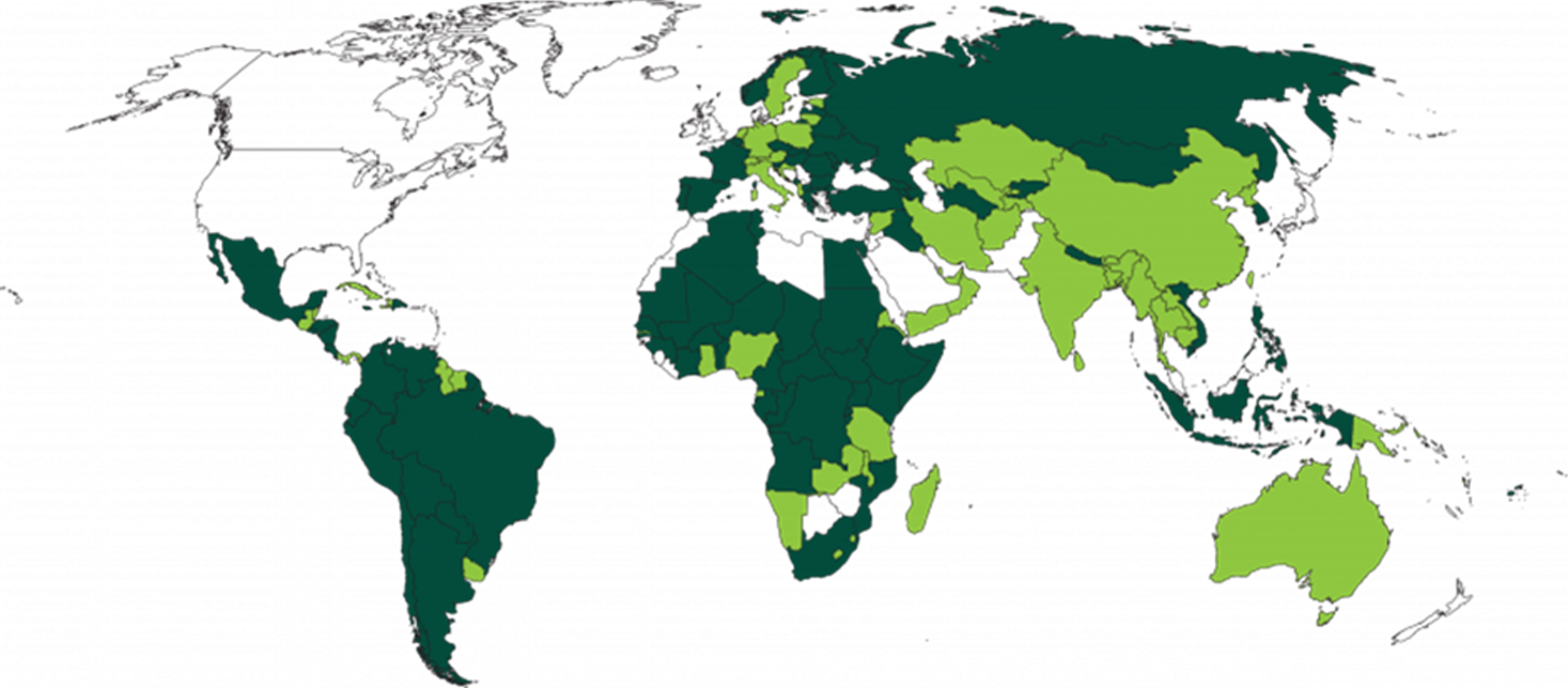

Legal human rights duties concerning the ‘safe space’ are interconnected to and informed by the content of Multilateral Environmental Agreements. Human rights concerning a healthy environment help in providing relatively stronger “teeth” compared to Multilateral Environmental Agreements alone.60 At the level of national constitutions, over 80% of UN Member States (156 out of 193) already recognize the right to a healthy environment or the rights of nature itself in their constitutions, environmental laws and/or regional treaties, see Fig. 3. While this article focuses on the global grand narrative of the right to a healthy environment and its connections with PB, this narrative will not be complete unless also advances at local, national and regional jurisdictional scales are taken into account. The idea of “buen vivir” as a model of development based on well-being rather than resource extraction in the constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia can be seen as originating from Andean communities recognizing “mother nature”.61 The Ecuadorian Constitution (Articles 71 to 74) states that “nature in all its life forms has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycle,” embracing the idea of economic development being subordinate to nature.62 In the context of the right to development and to a satisfactory environment prescribed under Articles 22 & 24 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights through its Working Group on Extractive Industries, Environment and Human Rights in Africa (WGEI), adopted a resolution authorising a Study on the Impact of Climate Change on Human Rights in Africa.63

Fig. 3

The right to a healthy environment. Dark green shows countries which have Constitutionally protected the right to a healthy environment. In light green are countries with constitutional provisions for a healthy environment.

Whether this right is realized in practice is dependent on what happens at other jurisdictional scales where PB can be turned into fair national targets to be included in national environmental laws.64

In balancing property rights with human rights concerning a healthy environment and rights of nature itself, governments must see renegotiation as a part of the idea of property.66 In Finland, for example, the Constitutional Committee accepted the government’s proposal to law banning coal power plants with a 10-year transition period and without compensation.67 The Committee argued that rights concerning climate change are weighty, and that energy producers cannot expect the regulatory framework for their operations to remain unchanged. Providing legal certainty and protecting the legitimate expectations of economic actors are still relevant for just transitions.68

Human rights treaties are live instruments, whose interpretation must adapt to current living conditions of humans and other living beings.69 Courts and state officials are now deducing environmental requirements from the existing fundamental and human right texts, referring, e.g., to the right to life and right to health. In this way, human rights law together with PB can catalyze societal shifts in values and actions to safeguard biodiversity and healthy ecosystems as preconditions for human flourishing while also recognizing intrinsic values of nature. It is increasingly realized that if surpassing the outer boundary in the Doughnut model cannot be reversed, the inner boundary cannot be reached either.

Economic development lacking intra- and inter-generational justice has caused the overshooting of already six planetary boundaries,70 which has led to human rights violations and exacerbation of inequalities and to compromising the ability of future generations to realize their human rights. To address the overshoots, some countries, regions, cities, and companies are already defining, calculating, and setting targets compatible with the Doughnut model.71 If all countries in particularly high and middle-income brought their economies inside the planetary boundaries, it would be a giant leap towards justice for current and future generations of humans in all countries. Effective regulation and strong economic incentives for reducing the water, climate, and biodiversity footprints of goods consumed are key in this process. Voluntary measures relying on companies’ information disclosure have not produced sustainable consumption and do not adequately tackle the structural roots of unsustainability and injustice.72 Hence, there is a need of binding obligations coupled with ground-up accountability and transparency.73

Different planetary boundaries should be turned into obligations for States derived from the right to a healthy environment. Further research is needed to clarify the elements of the right to a healthy environment on those planetary boundaries that are not yet addressed by the UN. Legal standing can only be assured if rights and duties are clear and tangible at each jurisdiction, clarified through legislation and/or case law. To ensure legal standing and easy access to justice, it would be beneficial that the right to a healthy environment, or the rights of nature itself, would be explicitly written in UN human rights agreements, regional human rights agreements, national constitutions, and environmental law.74

4Conclusion

Currently, dominant institutions and practices along with the underlying values and worldviews are largely unsustainable and unjust, and therefore societal transformations are required for the realization of the right to a healthy environment. To move towards the ‘safe and just space’ where this right can be enjoyed by everyone, all economic activities need to be subjected to planetary boundaries, and inequalities between and within countries must be tackled. Hence, all countries must target ‘safe’ and ‘just’ at the same time. Rather than a narrative which only focuses on human rights violations within nation States, we find that PB can inform a more systemic perspective and contribute to catalyzing a narrative of planetary safe and just space where the right to a healthy environment is a shared duty in an interconnected world. Below we discuss four key findings of this article.

First, combining the legal right to a healthy environment with PB has the potential to provide stronger evidence-based arguments for States to comply with the international human rights commitments that they have set for themselves. The inner boundary in the Doughnut model, the boundary for just space, is rather well covered by international human rights treaties to which most countries are part. Yet, the interconnected global dynamics that drive global inequalities are often overlooked. The PB can help revitalize the grand narrative of the right to a healthy environment placing a spotlight on international drivers that fuel inequality. Specifically, the PB framework can contribute to a narrative in which the right to a healthy environment as well as economic, social and cultural rights are understood in the context of Earth Systems change dynamics rather than in national or regional vacuums. Likewise, the right to a healthy environment enriched by PB research can help clarify how social-ecological dimensions of civil and political rights go beyond individual freedoms to also include an enabling environment for collective action to tackle planetary social-ecological challenges.75

Secondly, we find mixed results on the recent developments connecting the right to a healthy environment and the boundary for safe space: climate change, chemical pollution, freshwater withdrawals are relatively more elaborated than on ozone layer PB, ocean acidification PB, nitrogen and phosphorus loading PB and novel entities PB. Gaps in the latter PBs risks overlooking interconnected drivers of ecosystems degradation that affect the realization of the right to a healthy environment. Right to a healthy environment’s elements concerning the outer boundary of the PB/Doughnut model are increasingly being elaborated in recent years with the rise of litigation at the regional and national levels and the recognition of the right to a healthy environment by the UN Human Rights Council76 and the UN General Assembly.77 Clearer legal standing and justification for legal demands concerning PB not yet addressed by the human rights system are needed to tackle these drivers. The realization of the right to a healthy environment in a ‘just space’ relies on the enjoyment of ‘safe space’. States must act at various spaces including the national level and regulate global supply chains for humanity to reach a planetary safe and just space.

Third: a narrative that combines legal arguments with PB is vital to unlocking transformative change because legal arguments show that moving towards the PB/Doughnut model is not only a vision or an option but an obligation. Human rights law can make transition to a safe and just space a duty for national State institutions. Right-holders, which are individuals and certain collectives such as indigenous peoples, can demand governments to realize their fundamental and human rights in national law and policy, and they can hold duty-bearers accountable for violations and inaction through constitutional and human rights courts. State institutions, i.e., the executive, legislative and judiciary branches of the State, have a duty to take effective, system-changing actions. Existing rights need to be better enforced, and especially the ‘safe space’ rights need to be further developed.

As fourth conclusion, a relatively more systemic approach is emerging in human rights law where States are not only responsible for guaranteeing the rights of their own citizens or inhabitants. The UN General Assembly resolution (2022) on the right to a healthy environment is an example of this relatively more systemic approach which recognizes global drivers of climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution affecting this right. Yet, this systemic approach needs to be strengthened, and the PB’s and Earth Systems change narrative and associated evidence can help in this process. A UN treaty on business and human rights that is being negotiated (OEIGWG 2021)78 and the EU proposal for a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (European Commission 2022)79 are based on the idea that workers’ rights, indigenous rights and other ‘just space’ rights must be realized globally. Victims of violations should have legal remedies against transgressors, i.e., a possibility to sue responsible governments and companies.80 In certain climate cases, citizens from anywhere have been granted legal standing in national courts.81 The same should be possible concerning violations of rights connected to other planetary boundaries.

Understanding of what is safe and what is just is constantly evolving, and international human rights law likewise needs to keep developing. In the just space, information technology such as internet access is becoming a necessity in many countries for accessing information and having a voice in social-ecological matters. In the safe space, new problems may emerge related, e.g., to radiation, magnetism, microplastics, or hormone pollution. Technologies such as gene editing may create new solutions but also new problems. Combining international human rights law and advances at various geographical scales with PB provides a powerful tool for defending the prerequisites of good life for everyone, everywhere.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded through the 2020-2021 Biodiversa and Water JPI joint call for research projects, under the BiodivRestore ERA-NET Cofund (GA N°101003777), with the EU and the funding organisations Academy of Finland and Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. This work also received funding from the Strategic Research Council of the Academy Finland under the 2035Legitimacy project, funding period 2020-2023, decision number 352405.

Notes

1 United Nations Secretary General (2020), The Highest Aspiration: A Call to Action for Human Rights 2020.

2 United Nations General Assembly (2022), The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, A/RES/76/300 (28 July 2022), available at:https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3983329?ln=en.

3 United Nations Human Rights Council (2021), The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, A/HRC/RES/48/13, 8 October 2021, available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3945636.

4 United Nations Human Rights Council (2021), Human Rights and the Environment, A/HRC/RES/46/7, 23 March 2021, available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3927166.

5 J. Rockström et al. (2009), “Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity,” Ecology and Society, 14: 32; J. Rockström et al. (2009), “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity,” Nature, 461: 472-475; W. Steffen et al. (2015), “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet,” Science, 347(6223); J. Rockström et al. (2021), Identifying a Safe and Just Corridor for People and the Planet,” Earth’s Future, 9: e2020EF001866; J. Rockström et al. (2023), “Safe and Just Earth System Boundaries,” Nature, 619: 102-111, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8. K. Richardson et al. (2023), “Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries,” Science Advances, 9: eadh 2458.

6 K. Richardson et al. (2023), “Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries,” Science Advances, 9: eadh 2458.

7 Source: K. Richardson et al. (2023), ibidem.

8 K. Raworth (2012), A Safe and Just Space for Humanity; Can we Live within the Doughnut? Oxfam.

9 K. Raworth (2012), A Safe and Just Space for Humanity; Can we Live within the Doughnut? Oxfam, see Fig. 1.

10 R.A. Turner and J. Wills (2022), “Downscaling Doughnut Economics for Sustainability Governance,” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 56: 1-10.

11 K. Raworth (2012), A Safe and Just Space for Humanity; Can we Live within the Doughnut? Oxfam.

12 F. Biermann and A. Kalfagianni (2020), “Planetary Justice: A Research Framework,” Earth System Governance, 6: 100049.

13 L.J. Kotzé and R.E. Kim (2019), “Earth System Law: The Juridical Dimensions of Earth System Governance,” Earth System Governance 1: 100003.

14 J. Ensor and E. Hoddy (2021), “Securing the Social Foundation: A Rights-based Approach to Planetary Boundaries,” Earth System Governance, 7 : 100086.

15 J. Ebbesson (2014), “Planetary Boundaries and the Matching of International Treaty Regimes,” Scandinavian Studies in Law, 59 : 259-284. https://www.scandinavianlaw.se/pdf/59-8.pdf.

16 J. Rockström et al. (2023), “Safe and Just Earth system Boundaries,” Nature, 619 : 102-111, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06083-8.

17 UN General Assembly (2010), The Human Right to Water and Sanitation, A/RES/64/292, 28 July 2010, available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/687002.

18 M. Wewerinke-Singh (2022), “A Human Rights Approach to Energy: Realizing the Rights of Billions within Ecological Limits,” Review of European, Comparative and International Environmental Law, 31(1): 16-26; L. Löfquist (2020), “Is there a Universal Human Right to Electricity?,” The International Journal of Human Rights, 24(6): 711-723.

19 UN Human Rights Council (2021a), The Promotion, Protection and Enjoyment of Human Rights on the Internet, A/HRC/RES/47/16, 26 July 2021, available at:https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3937534; C.K. Sanders and E. Scanlon (2021), “The Digital Divide Is a Human Rights Issue: Advancing Social Inclusion Through Social Work Advocacy,” Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 6(2): 130-143.

20 UNICEF (2019), For Every Child, Every Right: The Convention on the Rights of the Child at a crossroads. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund.

21 Committee on World Food Security (2020), Impacts of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition: Developing Effective Policy Responses to Address the Hunger and Malnutrition Pandemic. High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition. Rome, September 2020.

22 United Nations Global Crisis Response Group (2022), Global Impact of the War in Ukraine: Billions of People Face the Greatest Cost-of-living Crisis in a Generation. UN Global Crisis Response Group on Food, Energy and Finance, 8 June 2022.

23 See The Right to the Continuous Improvement of Living Conditions. Responding to Complex Global Challenges, in Hoffman J. and Goldblatt, B. (ed), 2021, Hart Publishing.

24 D.W. O’Neill et al. (2018), “A Good Life for all within Planetary Boundaries,” Nature Sustainability, 1(2): 88-95; P.L. Lucas et al. (2020), “Allocating Planetary Boundaries to Large Economies: Distributional Consequences of Alternative Perspectives on Distributive Fairness,” Global Environmental Change, 60 : 102017: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.102017. A.L. Fanning et al. (2022), “The Social Shortfall and Ecological Overshoot of Nations,” Nature Sustainability, 5 : 26-36.

25 J. Hickel et al. (2022), “National Responsibility for Ecological Breakdown: A Fair-shares Assessment of Resource Use, 1970-2017,” The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(4): 342-349.

26 A.Y. Hoekstra and T.O. Wiedmann (2014), “Humanity’s Unsustainable Environmental Footprint,” Science 344 : 1114-1117; WHO (2017), Don’t pollute my future! The impact of the environment on children’s health: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-IHE-17.01.

27 UNEP (2019). United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2019, Nairobi.

28 J. Hickel et al. (2022), “Imperialist Appropriation in the World Economy: Drain from the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1990–2015”, Global Environmental Change, 73 : 102467.

29 I. Khan (2023), “Sustainable Development and Freedom of Expression: Why Voice Matters – Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression,” A/HRC/53/25, 19 April 2023, available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4011273.

30 C. Ituarte-Lima (2023), “Biosphere Defenders Leveraging the Human Right to Healthy Environment for Transformative Change,” Environmental Policy and Law, 53 : 139-151. C. Ituarte-Lima (in press), “Just Pathways to Sustainability: From Environmental Human Rights Defenders to Biosphere Defenders,” Environmental Policy and Law.

31 See recent discussion on the possibilities of the Aarhus Agreement Ryall, Á. (2023), “Brave New World: The Aarhus Convention in Tempestuous Times,” Journal of Environmental Law, 35(1): 161-166: https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqac023; on the Escazú Agreement Dávila, S. (2023), “The Escazú Agreement: The Last Piece of the Tripartite Normative Framework in the Right to a Healthy Environment,” Stanford Environmental Law Journal, 42(1): 63-119. https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/J_Davila-Escazu-Agreement_web_2-20.pdf.

32 J. Rawls (1971), A Theory of Justice, Oxford University Press.

33 A. Mason (2007), Rawlsian Fair Equality of Opportunity. Levelling the Playing Field: The Idea of Equal Opportunity and its Place in Egalitarian Thought, Oxford Scholarship Online.

34 ILO and Walk Free Foundation (2017), Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage.

35 R. Pilon (1982), “Property Rights and a Free Society. In ‘Resolving the Housing Crisis – Government Policy, Decontrol and Public Interest,” in M. Bruce Johnson (ed), San Francisco, pp. 393-401.

36 UN General Assembly (2007), Resolution 61/295, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; UN Human Rights Council (2022), A/HRC/51/24: Human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation of indigenous peoples: state of affairs and lessons from ancestral cultures.

37 A. Facio (2017), “Insecure Land Rights for Women Threaten Progress on Gender Equality and Sustainable Development,” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR), available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WG/Womenslandright.pdf.

38 J.G. Sprankling (2014), “The Global Right to Property,” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, 52 : 464-505.

39 Inter-American Court of Human Rights (2001), Mayagna (Sumo) Awas Tingni Community v. Nicaragua. Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of August 31, 2001. Series C No. 79.

40 D. Griffiths (2023), Human Rights Diplomacy, Navigating an Era of Polarization, Research Paper, Chatham House.

41 UN Human Rights Council (2021b), Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law, A/HRC/RES/46/4, 31 March 2021, available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3924689.

42 L. Wang-Erlandsson et al. (2022), “A Planetary Boundary for Green Water,” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 3(6): 380-392.

43 D.R. Boyd (2019), Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, UN General Assembly, A/74/161, 15 July 2019, available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/861173.

44 UN Human Rights Council (2014), Human Rights and Climate Change, A/HRC/RES/26/27, 15 July 2014, available at: http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/hrcouncil_res26-27.pdf; UN General Assembly (2020), A/74/161; UN (2020), Joint Statement of UN Entities on Climate Change and Human Rights, HRI/2019/1, 14 May 2020, available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/113/08/PDF/G2011308.pdf?OpenElement.

45 D.R. Boyd (2022), “The Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment: Non-toxic Environment,” Report of the Special Rapporteur on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment. UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/49/53, 12 January 2022, available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3957797?ln=en; D.R. Boyd and S. Keene (2021), “Human Rights-based Approaches to Conserving Biodiversity: Equitable, Effective and Imperative,” UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment. Policy Brief No. 1, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Environment/SREnvironment/policy-briefing-1.pdf; UN (2021), Joint Statement of UN Entities on the Right to a Healthy Environment. United Nations Environment Programme, available at: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/statements/joint-statement-united-nations-entities-right-healthy-environment.

46 D.R. Boyd, (2021a), Human Rights and the Global Water Crisis: Water Pollution, Water Scarcity and Water-related Disasters. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment. UN Human Rights Council, A/HRC/46/28, 19 January 2021, available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G21/012/23/PDF/G2101223.pdf?OpenElement.

47 D.R. Boyd (2021b), Healthy and Sustainable Food: Reducing the Environmental Impacts of Food Systems on Human Rights. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment. UN General Assembly, A/76/179, 19 July 2021, available at: https://srenvironment.org/sites/default/files/Reports/2021/Food% 2C% 20Environment% 20and% 20human% 20rights% 20A% 3A76% 3A179.pdf

48 D.R. Boyd and S. Keene (2021); D.R. Boyd (2020), Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Relating to the Enjoyment of a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment. Human Rights Depend on a Healthy Biosphere, UN General Assembly, A/75/161, 15 July 2020, available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N20/184/48/PDF/N2018448.pdf?OpenElement; UN General Assembly (2022), The Human Right to a Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment, A/76/L.75.

49 UN (2021), Joint Statement of UN Entities on the Right to a Healthy Environment. United Nations Environment Programme.

50 UN Human Rights Committee (2017), A/HRC/35/13, Analytical Study on the Relationship between Climate Change and the Full and Effective Enjoyment of the Rights of the Child.

51 UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (2023), General Comment No. 26 on Children’s Rights and the Environment with a Special Focus on Climate Change CRC/C/GC/26, available at: https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRC% 2FC% 2FGC% 2F26!Lang=en.

52 UN Human Rights Council (2018), Human Rights and Climate Change, A/HRC/RES/38/4, available at: https://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/RES/38/4.

53 For more on the initiative of Pacific Island Students, see https://www.pisfcc.org/.

54 United Nations General Assembly (2023), Request for an Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice on the Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change, /RES/77/276, 29 March 2023; International Court of Justice. Request for Advisory Opinion transmitted to the Court pursuant to General Assembly resolution 77/276 of 29 March 2023. Obligations of states in respect of climate change, available at: https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/187/187-20230412-app-01-00-en.pdf.

55 Neubauer et al vs. Germany. Federal Constitutional Court, Case No. BvR 2656/18/1, BvR 78/20/1, BvR 96/20/1, BvR 288/20.

56 P. Minnerop (2020), “The First German Climate Case,” Environmental Law Review, 22(3): 215-226; L. Kotzé (2021), “Neubauer et al. versus Germany: Planetary Climate Litigation for the Anthropocene?,” German Law Journal, 22(8): 1423-1444.

57 Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights (2019), “Living in a Clean Environment: A Neglected Human Rights Concern,” Human Rights Comment, 4 June 2019.

58 UN Human Rights Committee (2018), General Comment No. 36: Article 6, Right to Life, CCPR/C/GC/36.

59 UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment (2021), Policy Brief No. 1. Human rights-based approaches to conserving biodiversity: equitable, effective and imperative.

60 J. Ebbesson, (2014), “Planetary Boundaries and the Matching of International Treaty Regimes, Scandinavian Studies in Law, 59 : 259-284; N. Koh et al. (2021), Mind the compliance gap: how insights from international human rights mechanisms can help the Convention on Biological Diversity, Transnational Environmental Law Journal, 11(1): 39-67.

61 E. Gudynas (2011), “Buen Vivir: Today’s Tomorrow,” Development, 54(4): 441-447.

62 Ibidem.

63 See African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights: https://achpr.au.int/en/news/press-releases/2023-10-28/call-comments-study-impact-climate-change-human-and-peo.

64 T. Häyhä et al. (2016), “From Planetary Boundaries to National Fair Shares of the Global Safe Operating Space—How can the Scales be Bridged?,” Global Environmental Change, 40 : 60-72.

65 UNEP (2019), United Nations Environment Programme. Environmental Rule of Law: First Global Report. Nairobi. Figure 4.5. For a disaggregated list of countries and their legal recognition of the right to a healthy environment and whether it is implicit, explicit and the kind of instrument where the right is recognized (Constitutional law, national legislation, international treaty), see table 1 in page 11 in the good practices report by Boyd (2020), Right to a healthy environment, good practices, available at: https://www.unep.org/resources/toolkits-manuals-and-guides/right-healthy-environment-good-practices. See also UNEP (2023), United Nations Environment Programme. Environmental Rule of Law: Tracking Progress and Charting Future Directions, available at: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/new-era-environmental-rule-law-takes-shape-un-recommends-good.

66 M.J. Radin (1993), “Reinterpreting property,” University of Chicago Press; M.R. Poirier (2000), “The Virtue of Vagueness in Takings Doctrine,” Cardozo Law Review, 93 : 182-183; L.S. Underkuffler (2003), The Idea of Property: Its Meaning and Power, Oxford University Press.

67 PeVL 55/2018 vp - HE 200/2018 vp: Perustuslakivaliokunnan lausunto. [Statement of the Constitutional Committee] Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laeiksi hiilen energiakäytön kieltämisestä ja oikeudenkäynnistä markkinaoikeudessa annetun lain 1 luvun 2 §:n muuttamisesta.

68 A. Boute (2012), “The Quest for Regulatory Stability in the EU Energy Market: An Analysis Through the Prism of Legal Certainty,” European Law Review, 37 : 675-692.

69 See e.g., Inter-American Court of Human Rights (2001), Mayagna (Sumo) Awas Tingni Community v. Nicaragua, Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of August 31, 2001. Series C No. 79.

70 K. Richardson et al. (2023), “Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries,” Science Advances, 9: eadh 2458.

71 See e.g., Amsterdam City Doughnut (2020), at: https://www.kateraworth.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/20200406-AMS-portrait-EN-Single-page-web-420x210mm.pdf, visited 25 September 2023.

72 P. Stromberg and C. Ituarte-Lima (2021), “The Transformative within Transparency: untapping ground-up environmental information and new technologies for sustainability,” in Sustainable Production and Consumption, Swain, R. and Sweet, S. (eds), Palgrave Macmillan.

73 Ibidem.

74 See D. Boyd et al. (2021), “#TheTimeIsNow: The Case for Universal Recognition of the Right to a Safe, Clean, Healthy and Sustainable Environment,” report, Universal Rights Group, February 2021.

75 A. Chalabi (2023), “A New Theoretical Model of the Right to Environment and its Practical Advantages,” Human Rights Law Review, 23(4): https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngad023 on how individual and collective rights can complement each other.

76 United Nations Human Rights Council (2021), The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, A/HRC/RES/48/13.

77 UN General Assembly (2022), The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, A/76/L.75.

78 OEIGWG (2021), “Open-Ended Intergovernmental Working Group on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises With Respect to Human Rights (IGWG),” Third revised draft, 17.8.2021. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/WGTransCorp/Session6/LBI3rdDRAFT.pdf

79 COM (2022), 71 final. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937.

80 Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte (2023), Position Paper. Access to justice under the CSDD Directive Finalizing trilogue negotiations of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive; European Coalition for Corporate Justice (2023), Unpacking the CSDDD: access to justice and civil liability: https://corporatejustice.org/news/unpacking-the-csddd-access-to-justice-and-civil-liability/

81 Neubauer et al. vs. Germany, Federal Constitutional Court, Germany. Case numbers BvR 2656/18/1, BvR 78/20/1, BvR 96/20/1, BvR 288/20.