The Environmental Fund Management Model in Indonesia: Some Lessons in Legal Regulation and Practice

Abstract

Environmental Fund Management (EFM) is a government effort to optimize EEI (Environmental Economic Instruments), to preserve the functions of the ecosystem. Based on regulation, EFM is entrusted to the Indonesian Environmental Fund (BPDLH) through channeling, fund fertilization, and distribution. BPDLH is appointed a trustee to manage the environmental fund, especially the trust/conservation assistance finance. The existence of trustee agreements often requires follow-up from a legal aspect. This is because Indonesia’s legal system does not recognize the trust law essentially acknowledging the dual ownership of an asset/property. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the use of the trust model in environmental fund management from a legal perspective. It also aims to evaluate the reasons Indonesian law needs to propose a trust policy as the basis for any activity adapting to conservation assistance, including EFM. This study was carried out by using a normative and qualitative juridical analysis. The results showed that the model used in EFM was a legal adaptation of the trust law and was adjusted to the Indonesian constitutional system not recognizing dual ownership. This trust model emphasized an agreement as a legal basis and limited the trustee’s authority in managing funds, leading to suboptimal environmental finance management, especially in nurturing money. Meanwhile, the environmental fund managed by BPDLH was relatively small compared to the needs. This proved that the trust model was represented by individuals/institutions as beneficiaries, based on an agreement with the trustee. From this context, the presence of Indonesian Trust law was capable of ending the legal vacuum in the constitutional system of the country. By specifically regulating the principles of trust and incorporating the dual ownership concept into the proposed law, the goal of fund management was achieved, including environmental finance. The management goal also maximized the benefits for the beneficiaries, namely the environment

1Introduction

The commitment of Indonesia to supporting sustainable development goals (SDGs), especially in addressing the challenge of climate change, is part of the policy in the National Medium-Term (RPJMN) 2020-20241 and Long-Term (RPJP) 2005-2025 Development Plans. In the RPJP, the 6th mission emphasizes the realization of a pristine and sustainable Indonesia by controlling pollution, damage, and natural disaster mitigation.2 From this context, sustainable regulatory and policy changes are affected on a supportive legal basis.3 The sustainable aspect of this development is carried out through new mindsets and behaviors toward low-carbon and hazardous waste, preserving biodiversity, and maintaining the physical support capacity of nature. These changes in behavior and mindset are accompanied by aligned and supportive regulations and policies, including the National Action Plan - Greenhouse Gas Reduction (NAP GHGR)+NDC.4 Furthermore, the Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (IBSAP) of Indonesia is the main guideline for policy formulation, conservation, and implementation planning.5 The National/Regional Spatial Plan (RTRWN/D) is also used as a reference in these strategic conditions.6 To address climate change, the government’s initiative to set a carbon price has recently been answered by the Financial Services Authority (FSA). This initiative is expected to prepare the operational carbon exchange and has become the main focus of FSA’s Sustainable Finance Roadmap Phase II (2021-2025).7 From this context, the country is able to absorb 25 billion tons of carbon due to having a tropical forest covering an area of 125 million hectares, not including mangrove and peat plantations. This carbon absorbance subsequently leads to an estimated income of 565.9 billion USD from trading.8

2Compliance with Indonesia’s International Obligations

In line with Article 4, paragraph 12 of the 2015 Paris Agreement, Indonesia was obligated to prepare and communicate its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). The country has also recently submitted an updated first NDC on July 22, 2021,9 to unconditionally and conditionally reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 29% and 41%, respectively. This is expected to be carried out through international assistance from a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario by 2030.10 To reduce GHG emissions, the commitment of Indonesia is based on voluntary motivation and national capabilities, not by external pressure or coercion. This emphasizes a responsibility sense and the principle of “common-differentiated accountabilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR-RC).11 Since 2020, the country had also developed the Long-term Strategy for Low Carbon and Climate Resilience (LTS-LCCR 2050) document towards net-zero emissions, while considering economic growth, climatic resilience, and justice. This LTS-LCCR 2050 document is a long-term direction guiding the implementation of climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the NDC commitments of Indonesia for the next five years.12

To achieve this goal, the government is expected to ensure environmental protection and management sustainability, including the enhancement and acquisition of financial opportunities from the public and private sectors.13 Meanwhile, environmental financing is a problem for countries14, including Indonesia15, which urgently needs to address ecological damage, including the transnational disasters caused by forest fires. In this country, the impact of forest fire smoke is often encountered by neighbouring countries, such as Singapore and Malaysia. Forest fires are recognized as one of the worst environmental disasters of all time, due to their massive plantation impacts and large carbon emissions, which greatly affect the lives of neighbouring countries. Aside from environmental damage, forest fires also cause economic and sociocultural losses.16 In 2015, the losses suffered by Indonesia due to forest fires were estimated at IDR 221 trillion (USD 16.1 billion). The drying and conversion of peatlands, primarily driven by palm oil production, also contribute to the increased intensity of smoke haze from fires. This was because 33% of burned areas are peatlands, causing the hazardous smoke haze to engulf the country and its surrounding areas, as well as the disruption of transportation, trade, and tourism.17 In 2019, the largest forest and land fires engulfed 1,649,258.00 hectares across 34 provinces, with Kalimantan Island suffering the highest losses. Meanwhile, the area of the disaster decreased drastically by 81% in 2020, covering only 296,942.00 hectares.18 At the beginning of 2021, the fires still occurred frequently, with West Kalimantan province (14,052 hectares) exhibiting the highest occurrence, accompanied by Riau province (6,492 hectares).19 Until this present period, forest and land fires in Indonesia have become a technical problem, and their resolution is limited to digital solutions. This condition has led to the yearly emergence of fires, especially during the dry season. Based on the fire triangle theory, the hot weather and dry ecosystem conditions do not cause fires, although a non-causal correlation is observed between the triggering factors.20

In actual practice, the main causes of fires in Indonesia comprise social and cultural factors or human intentional and unintentional activities in managing forests and land. Some of these activities include fire use in land preparation, forest management system dissatisfaction, illegal logging, the need for animal feed, plantation encroachment, and other causes.21 Besides the political ecology approach emphasizing the role of actors at the local, regional, and global levels in environmental management, the law also plays an important duty in changing the behaviour and mindset of all stakeholders. In the framework of the ecological constitution in Indonesia, Article 42 of Law Number 32 of 2009 concerning Environmental Protection and Management (EPM Law) required the central and regional governments to develop and implement EEIs (environmental economic instruments), toward preserving the functions of the environment. In this case, funding and managing environmental finance is one of the objectives of the economic instruments.

3Environmental Fund Management

Based on Presidential Regulation No. 77 of 2018 on Environmental Fund Management (Presidential Regulation EFM), EEI focused on managing ecological finance as a system and mechanism used to monetize sustainable protection and administrative efforts through fundraising, as well as capital fertilization and distribution. As the ecological capital manager, the government has reportedly established a joint enterprise, namely the Public Service-Indonesian Environmental Fund Management Agency (BLU-BPDLH) 22 under the Ministry of Finance. According to Presidential Regulation EFM, the environmental funding managed by BPDLH included pollution/damage control and ecological restoration fund, with trust/conservation assistance capital maintained by the government. From this context, the management of fund often aims to realize the government’s promise to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In this case, the mandate of BPDLH is not limited to emission reduction efforts. The environmental fund is also designed to manage various financing schemes toward capital programs and recipients from several monetary sources. However, the main reason the fund was established is to have possession of an effective fund disbursement is historically the main reason the ecological capital is established. This emphasizes the achievement of emission reduction targets from land and forest use changes.23 Based on this description, the funding and management of the environmental capital are the government’s focus to meet its commitment.

The appointment of a trustee by BPDLH is an interesting aspect of the Presidential Regulation EFM related to trust/conservation assistance fund management. As a party involved in fund management, the emergence of the trustee has a strong legal impact on the Indonesian legal system, which does not recognize trust law.24 Moreover, Presidential Regulation EFM does not regulate the mechanism for fund management when a trustee is used. Another legal issue explains that environmental fund management should be used for the maximum benefit or interest of the environment. From this context, the beneficiary of EFM needs to be the environment in the trust concept. This leads to the necessity to assert and have the courage to position the environment as a legal subject. Although Indonesian law does not explicitly state that the environment is a legal subject, the environment should still be treated as a lawful phenomenon with rights and obligations, regarding regulatory interpretations, doctrines, and objectives. Based on the regulations and policies on environmental fund management, two legal issues require in-depth analysis, namely 1) the patterns by which the trust model is implemented, and 2) the urgency of legally establishing a trust law for the use of benefactions in Indonesia.

4Study Methods

This study used a normative juridical approach, which often prioritizes the secondary data related to the analyzed object, such as primary, secondary, or tertiary legal materials. These materials were then qualitatively analyzed and presented in a descriptive-analytical pattern.

5Results

5.1Funding and Environmental Fund Management Regulations

As a country influenced by the civil law system, the main legal source of Indonesia is legislation. To regulate the funding and management of environmental capital, a minimum of 3 regulations need to be emphasized. Firstly, Law No. 32 of 2009 concerning Environmental Protection and Management (EPM Law). In this regulation, Article 42 obliged the central and local governments to develop and implement Environmental Economic Instruments (EEI), to preserve the function of the environment. EEI is an economic policy set to encourage the central and local governments or any person toward environmental preservation. Secondly, Government Regulation No. 46 of 2017 concerning Environmental Economic Instruments (EEI Government Regulation).25 From this policy, 3 important elements were regulated, namely the scope and objectives of EEI, as well as the EFM mandate with the financial management of Public Service Agencies. Article 2 of this Government Regulation also indicates that Environmental Economic Instruments aim to perform the following,

i. Ensure accountability and compliance with the law.

ii. Change the mindset and behaviour of stakeholders.

iii. Seek systematic, regular, structured, and measurable environmental funding.

iv. Build and encourage public and international trust in environmental funding management.

Moreover, Article 3 regulated the EEI structure, including development planning and economic activities, environmental funding, as well as incentives and disincentives.

Based on the EEI objectives, the funding and management of environmental capital were important measures to prevent, mitigate, and restore ecological functions. Article 20 of EEI Government Regulation subsequently mentioned three environmental funding types, namely a) environmental restoration guarantee fund, b) pollution control/environmental damage and restoration fund, and c) trust/conservation assistance fund. Thirdly, Presidential Regulation No. 77 of 2018 concerning Environmental Fund Management (EFM Presidential Regulation). This regulation systematically regulated the EFM fund as a system and mechanism used to finance environmental protection and management, as well as the EFM objectives, methods, principles of EFM, and implementers. Based on these descriptions, Environmental Fund Management (EFM) aims to preserve the function of the environment through transparent, efficient, effective, proportional, and accountable efforts, as well as building and encouraging public and international confidence.

5.2Types of Environmental Funding

However, some changes were observed in the funding regulations within the EFM Presidential Regulation. The environmental restoration guarantee fund, previously regulated in Articles 21-25 of the EEI Government Regulation, is no longer governed by the EFM Presidential Regulation. This is due to the revocation and re-regulation of Articles 21-25 by Article 55 of Government Regulation No. 22 of 2021 on the Implementation of Environmental Protection and Management (P3LH Presidential Regulation). The P3LH Presidential Regulation also specifically regulates the Guarantee Fund for the Restoration of Environmental Functions. Furthermore, the guarantee fund is essentially observed as a sum of money deposited by the environmental approval holder (business actor), which should be held in a government bank. From this context, the deposited money is a “guarantee” for implementing environmental restoration/pollution mitigation or other ecological management objectives.26 In this case, each sector practically applies the mechanism of guarantee funds differently. For example, the reclamation guarantee fund that should be provided by mining activities toward the payment of a specific capital is capable of being returned during the completion of all business restoration programs.

The environmental guarantee fund is also the responsibility and legal capital belonging to the business actor. From a legal perspective, this fund emphasizes a “guarantee”, which provides a lawful certainty regarding the responsibility of the business actor for environmental protection and management. Therefore, this environmental restoration guarantee fund is unable to be included as a financial asset managed by the BPDLH (Indonesian Environmental Fund Management Agency) and/or trustee. The provisions regarding environmental guarantee funds are also an implementation of the polluter pay principle, as stipulated in Articles 2 and 87 of the PPLH law. It states that every responsible party whose business and/or activities cause environmental pollution and/or damage is obliged to bear the cost of restoration. Besides being required to pay compensation, business actors are also ordered by a judge to conduct specific legal actions, such as installing or repairing waste treatment units. In this case, the waste is capable of meeting the environmental quality standards set, restoring societal functions, and eliminating the cause of pollution/destruction. Another concept adopted in the PPLH law is proportionality, asides from the polluter-pay principle. As a country with a geographical condition similar to Indonesia, Malaysia is responsible for including the polluter-pay principle in the Environmental Quality Act 1974-127 amended in 2001. This law regulates several matters related to environmental funds, such as its establishment, committee, contributions, and use. Based on previous studies, pollution control in the palm oil industry is implemented through a combination of a command-control approach and a market-based instrument. The EQA 1974 also indicates the level of charges and penalties for those polluting the environment.27 Moreover, the practices in Malaysia show that the implementation of the polluter-pay principle is able to reduce environmental pollution. Another financial scheme managed by BPDLH asides from the environmental guarantee budget includes the following, (1) pollution mitigation/damage and environmental restoration fund, and (2) trust/conservation assistance fund. This scheme is developed through a trust model for environmental restoration.

5.3Activities of Environmental Fund Management

Environmental fund management is carried out transparently, efficiently, effectively, proportionally, and accountably, with the activities consisting of fundraising, as well as capital fertilization and distribution. Table 1 shows the activities, mechanisms, and funding sources of EFM.

Table 1

Environmental fund management activities

| Activity | Mechanism | Source |

| Fundraising | •Pollution/Damage Control and Environmental Restoration Fund •Trust/Conservation Assistance Fund | •State Budget (APBN) •Regional Budget (APBD) •Other legitimate and non-binding sources, such as the following, 1. Cash surplus, 2. Donations/charity, 3. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), 4. Carbon trading profit-sharing, 5. Government environmental program fund. |

| Fund Fertilization | •Banking instruments •Capital market instruments •Other financial instruments by the regulations. | |

| Fund distribution | •Carbon trading •Loans •Subsidies •Grants •Other mechanisms by the provisions of the law |

Sources: EFM Presidential Regulation.

The Indonesian government established the BPDLH (Indonesian Environment Fund Agency) to provide continuous funding facilities for environmental protection and management.28 From this context, several reasons supporting the establishment of the agency were emphasized. Firstly, the commitment of the government to environmental protection and management is manifested through cost allocation, regarding the climate budget tagging conducted by the Ministry of Finance. Climate budget tagging is an important tool for the government to monitor and track their expenses on climate-related activities, with adequate communication of these expenditures to investors.29 In 2020, the Indonesian government officially prioritized climate change in the Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2020-2024, which is the National Priority for Environmental Enhancement. Increased disaster resilience and climate change were also directed through various policies to improve environmental quality, elevate hazardous and climatic adaptability, as well as develop low-carbon initiatives.30 However, the climate budget tagging allocation in the state budget is relatively small, compared to the need to achieve the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target. This indicates that Indonesia needs an average annual funding of IDR 266.3 trillion until 2030, while the average cost allocation in the state budget for 2020-2022 is around IDR 37.9 trillion.31

To support climate change policies and efforts, funding is needed for various public and non-public programs/activities. Secondly, until this present period, the environmental fund has not been managed optimally, as the budget is spread across several ministries with various programs in different institutions. This shows that the environmental fund being managed by BPDLH is presently IDR 14.52 trillion. Besides being sourced from the state budget, it also originates from areas, such as (a) reforestation fund, (b) Green Climate-Fund grants for the REDD+RBP project, (c) Ford Foundation grants from the Community-Based TERRA program, (d) World Bank loans for the Disaster Pooling Fund program, (e) Mangrove for Coastal Resilience, and (f) World Bank grants.32 From this context, the potential funding should be around IDR 24 trillion. Thirdly, the funding from developed countries, regarding environmental protection and management, is strengthening in line with the need for ecological financing in developing nations, which supports the Paris Agreement. Based on these data, a gap is still observed between the fund managed by BPDLH and the total environmental budget needed. This shows that fund accumulation is highly necessary through an appropriate management model. It is also one of the reasons the Indonesian Government establishes BPDLH, which increases and manages environmental fund.

By implementing transparent and accountable EFM, BPDLH is observed as a solution for developed countries to provide funding.33 Based on the EFM Presidential Regulation, the Pollution Control/Environmental Damage and Recovery Fund and the trust/conservation assistance capital were managed by BPDLH. In addition, 3 objectives were found for the establishment of BPDLH, namely 1) Consolidating various environmental funding sources, 2) Managing environmental funds, and 3) Distributing capital through various instruments for specific supportive projects and activities. This distribution is to improve environmental management and protection, support environmentally friendly economic activities, and reduce GHG emissions. The mechanism for managing environmental funds is carried out through the following schemes,

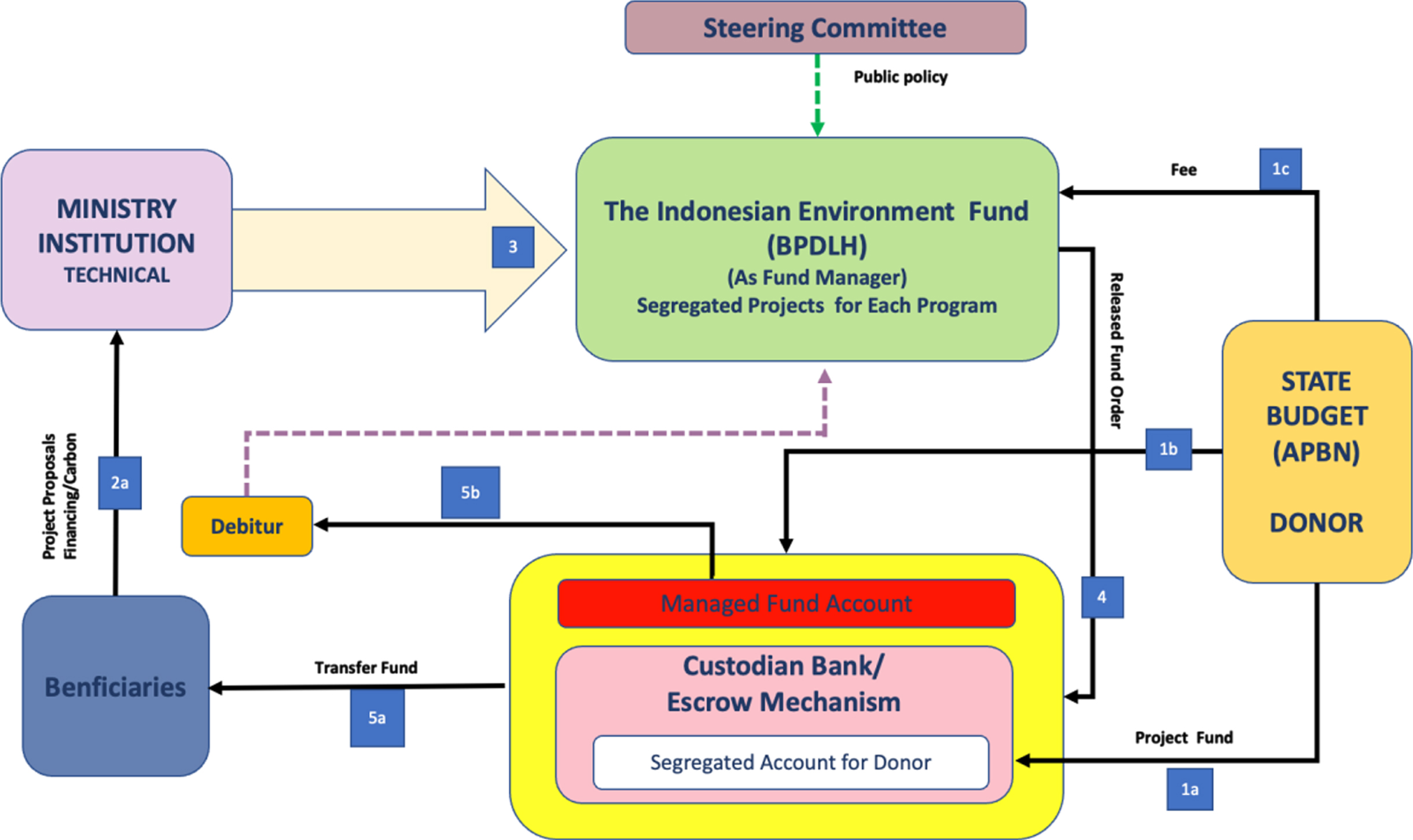

Fig. 1

Existing environment Fund manager mechanism. Source: processed from various sources.

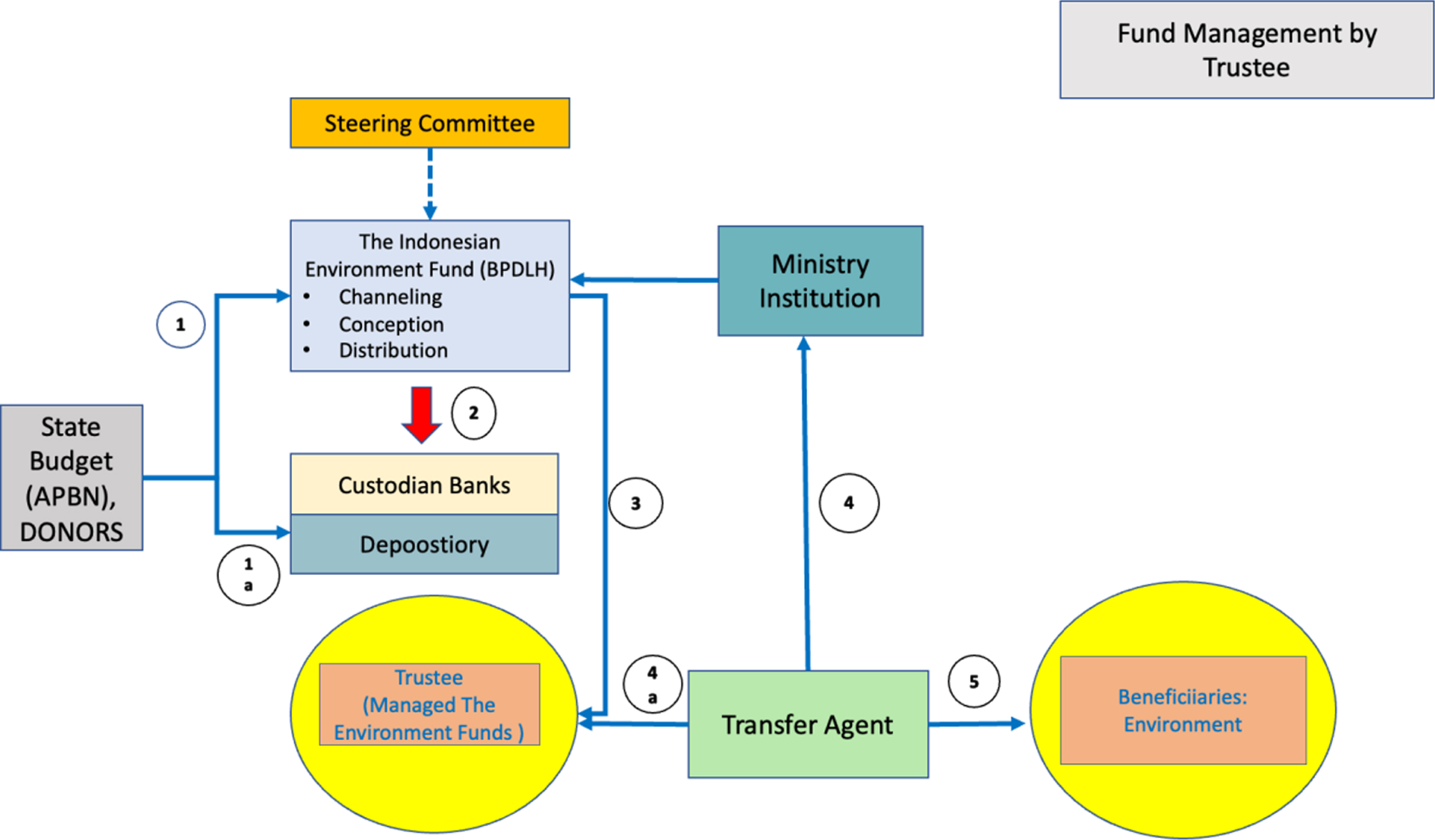

Fig. 2

Suggestion for environment Fund manager mechanism. Source: processed from various sources.

5.4The concept of trust in the Indonesian legal system

Based on Article 9 of the Presidential Regulation on Environmental Fund Management (Presidential Regulation EFM), BPDLH was likely to appoint and designate a Custodian Bank as a trustee in managing ecological capital. Meanwhile, the regulation should be interpreted by the legislation capable of distinguishing the functions of Custodians and Trust Banks regardless of their banking services development. According to FSA Regulation No. 27/POJK.04/2019 Regarding Approval of Commercial Banks as Custodians, a Custodian Bank was a commercial facility with the permission to provide safekeeping services for securities and other related assets. This included the acquisition of dividends and interest, as well as the representation of account holders/customers. Meanwhile, trust was regulated in FSA Regulation No. 25/2016 regarding Amendment to FSA Regulation No. 27/2015 concerning Trust Management (Trust FSA Regulation). Based on the fundamental differences, a Trust Bank manages assets through the consent of the owner (the settlor), while a Custodian monetary facility is only limited to obtaining and administering the deposit.

Article 9 of the EFM Presidential Regulation was also corrected by the Minister of Finance Regulation No. 124/PMK.05/2020 on the Procedure for Managing Environmental Fund (PMK 124/2020), regarding the differences between Custodian and Trust Banks. In the Indonesian EFM, the use of the trust concept is different from the property law principle in the common legal system. This law involves a fiduciary relationship, as well as the independence and dual ownership of trust property.34 However, the implementation of this law is confronted by various legal challenges. Firstly, Indonesian trust law does not recognize dual property ownership, regarding an inherent concept feature. In common law jurisdictions, the trust concept is based on recognizing dual ownership, namely the legal trustee and equitable beneficiary properties. This type of ownership is an important feature of trust regarding common law.35 Compared to trust law in the common law system, the positive policy influenced by the civil law system in Indonesia does not recognize dual ownership, as both legal and beneficial properties are attached to the same constitutional subject. Therefore, the trust law in this country only regulates the joint ownership of property.

Secondly, the trust concept adaptation in Indonesia is carried out through contract law, which provides opportunities and flexibility to develop new agreements with different names. Meanwhile, the Trust concept in the common law system is built on the equity inseparable by policy to develop justice.36 This shows that the legal relationship in the country’s trust model originates from the agreement developed by the parties. It is also subject to the terms and conditions of the agreement, as regulated in the Indonesian Civil Code.37 This proves that the parties’ trust agreements emphasize the legal principles of the contract. In civil law countries, the concept of trust is widely and similarly used in the business relationships context.38 The Trust FSA Regulation issuance in Indonesia also aims to adopt and adapt the principle from the common law system, to support the development of the financial services sector. Based on this regulation, several specific aspects were observed in the use of the trust concept, namely, (1) the trustee is a Bank with specific conditions, (2) only financial assets are managed by the trustee, (3) the legal relationship between the financial asset owner (the settlor) and the trust needs to be developed in a written agreement, (4) financial assets should be separated from the Bank’s possessions as a trustee and be bankruptcy remote. This indicates that the trust asset does not enter the bankruptcy estate, and (5) all the trustee’s legal acts need to be carried out with a written order from the settlor. This shows that the trust concept in Indonesia originates from an agreement between the settlor and trustee, for the benefit of a third party (beneficial owner).

6Discussion

6.1The Use of the Trust Model in Environmental Fund Management

Environmental fund management in Indonesia involves the following parties,

i. BPDLH is the implementer of fund management through fundraising, as well as capital fertilization and distribution activities.

ii. Custodian Bank, a facility appointed by BPDLH to store and administer the fund.

iii. Trustee Bank, a facility conducting deposit activities with management, based on Trust FSA Regulation.

iv. Beneficiaries consist of individuals, customary law communities, registered community groups, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, businesses, and/or educational/research institutions.

The trust model is used when BPDLH, in its fund allocation activities, appoints an intermediary institution (trustee) to transfer capital to the beneficiaries. This model is used when the beneficiaries are unable to access the fund directly. From this context, BPDLH is responsible for the direct distribution of funds to the appropriate beneficiaries. In the EFM, the trust model adaptation needs to consider the following legal aspects,

i. The basic legal relationship between the parties is an agreement. This includes (a) the agreement between the grantor/donor and BPDLH, (b) the agreement between BPDLH and the Trust Bank, and (c) the contract between the intermediary institution and the beneficiary.

ii. BPDLH and the trustee are responsible for optimizing environmental funds through financial instrument investments, including banking, capital market, and/or other policy-based monetary tools.

iii. The trustee or intermediary institution is the authorized receiver from the beneficiary.

This trust model has a weakness when the purpose of EFM prioritizes the cultivation of environmental fund, which is used to maintain and preserve the environment. This trust agreement model limits the authority of the trustee to manage funds, due to the emphasis of all investment decisions and instrument selection on the written instructions from the settlor (BPDLH). Furthermore, the trustee or intermediary institution is the authorized receiver from the beneficiary based on a contract. This provision deviates from the concept of trust, where the trustee only manages assets for the benefit of the beneficiary, without needing a contract, indicating that the trust model in EFM is yet to provide fund management, especially capital fertilization. Based on EFM regulations, another weakness of the trust model emphasizes the development of an alternative and the provision of authority to BPDLH, to distribute and cultivate funds. In this case, the total implementation of the trust model for fund cultivation is expected to be better than just an option. By entrusting environmental fund management to the trustee, BPDLH needs to focus on obtaining and distributing ecological capital. In addition, the position of the environmental fund, as a trust asset, ends the uncertainty about its status. From these interpretations, the beneficiaries’ regulation regarding Minister of Finance Regulation Number 124/2020 should be understood as the “representative or agent of the environment”. This proves that all cultivation outputs and BPDLH’s environmental fund distribution aim to preserve and protect the environment. The recommended mechanism for using the trust concept in environmental fund management is described as follows,

Based on the proposed mechanism, BPDLH serves as a settlor transferring the management of environmental funds to the trustee, regarding the principles regulated in the Trust Law. As the legal owner, the trustee has a strong legal basis and the flexibility to manage the trust asset according to applicable laws and regulations. In this case, the fund management outputs are greatly implemented for environmental benefits, as the predetermined beneficiary. Since the environmental fund is obtained from the State Budget and donors, its management supervision is carried out by the government or designated institutions based on applicable laws and regulations. Therefore, Indonesian policies show that the institutions socially and commercially managing public funds are under the supervision of the Financial Services Authority.

6.2Environment as beneficiary (beneficial owner)

The regulation on EFM states that this fund is used to finance environmental protection and management. This shows that the environment is the primary beneficiary of environmental fund management. In this case, the use of the trust model in managing environmental funds should position the environment as the beneficiary. As the beneficial owner, the position of the environment has the consequence of being portrayed as a legal subject. According to Christopher D. Stone (1974), the doctrine of “the environment as a legal subject” was popularized through the discussion that revolutionized the philosophical thinking of law.39 The landmark case in the new face of environmental legal protection was Sierra Club v Morton (1972). This case was a lawsuit that asserted the first environmental legal standing, where Sierra Club sued the US Forest Service over the ecological damage caused by the Mineral King development near Sequoia National Park in the United States. In this case, one of the judges, William O Douglas, presented a monumental dissenting opinion that triggered a widespread discourse in various countries. This emphasized the assertion of the environment and/or natural resources rights to have legal standing in defending their protection.40 Furthermore, the development of the environmental personhood concept has become a focus for countries around the world. This is because the granting of legal personality to environmental elements is always carried out to protect nature and its components. As a legal entity or subject, the recognition of the environment has reportedly been a slow process, mostly in the form of judicial statements. Until this present period, many countries such as New Zealand, Bolivia, India, and Ecuador had emerged with various environmental concepts as a judicial personality.41

Although the Environmental Law in Indonesia did not explicitly state that ecology is a legal entity, the implicit and systematic recognition portraying constitutional existence was still observed. According to Indonesian environmental law expert, Prof Munadjat Danusaputro, “the entire environment was a legal subject unable to be owned by individuals or groups. To provide certainty regarding environmental rights, the law was needed as a foundation to produce legal rights to the environment. By recognizing the environment as a legal entity, everyone was then obliged not to engage in pollution or ecological damage activities”.42 In the environmental fund management providing financial facilities as a legal protection and management effort, the environment was also a beneficiary.43 This explains that the regulated “beneficiary” should be interpreted as the representation of the environment. By placing the environment as the beneficiary, the parties representing its existence need to use the environmental fund to benefit the ecosystem, leading to optimal EFM.

6.3The urgency of the Trust Law as the basis for Trust based activities

Based on the use of trust models in environmental fund management, various regulations and practices were constrained by Indonesia’s legal system, which is influenced by the civil law system. This showed that the implemented trust model was more heavily influenced by the agreement development than the acceptance of the benefaction as a new legal institution. In this case, the legal relationship between the BPDLH, trustee, and beneficiaries should be documented in an agreement. Therefore, the trustee managed the fund based on the regulations governing the management of the environmental fund. This did not align with using a trustee and optimizing management, especially in the fertilizing environmental fund. The individual or institution representing the environment as a beneficiary should also consider an agreement with the trustee. From this context, the trust model entirely limited by the agreement often deviates from the concept of benefaction, where the beneficiary does not require legal efforts to obtain benefits. In this study, the implemented model used the concept of an agreement regulated in Article 1317 of the Civil Code, namely, “a promise for the benefit of a third party, which required the approval of the third party.

Another reason Indonesia needs a trust law is the scattered adoption of benefactions in several regulations for specific purposes. Indonesia had adopted trusts in Presidential Regulation No. 80 of 2011 on the Endowment Fund, before the Trust FSA Regulation in the financial services sector to expand banking services. This regulation was specifically issued to accommodate the grant fund managed by an institution acting as a trustee. Even before the issuance of Presidential Regulation No. 80 of 2011, the grant fund management, through the EFM model, had been recorded since 2005 via the Indonesia Biodiversity Project program sponsored by USAID. The Endowment Fund model was also used in the Aceh disaster response and recovery from 2005-2009, through the establishment of the MDTF (Multi-Donor Trust Fund Aceh). After the enactment of Presidential Regulation No. 80 of 2011, two trustee institutions were subsequently established, namely (1) the Millennium Challenge Corporation, whose establishment in 2013 was to reduce poverty through sustainable economic development44, and (2) the Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund (ICCTF) established in 2014. In this country, the endowment fund was formed by the government obtaining funds from grantors, not directly by the settlor or owner of the property. This led to a transfer of legal responsibility that should be imposed on the settlor to the government.

Indonesia has slowly implemented the trust model for fund management based on its National law.45 According to the perspective of Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, a neutral legal field unrelated to the cultural and spiritual life of the community should be emphasized in national law development. This is because a law-neutral field is considered more appropriate for renewal, and the implemented foreign models in conceptions, processes, or institutions are always justified. However, the challenges hindering the use of foreign models need to be necessarily considered. Based on these descriptions, the use of the trust concept in Indonesia has undergone an adoption process.46 The function of the trust institution should subsequently be optimized by applying several equity maxims to banking trust practices in the country. These maxims include the following:47

i. He t hat comes to equity should arrive with clean hands: This is one of the most popular maxims of equity, where individuals with bad histories are not allowed to benefit from the wrong they have conducted.

ii. Equity follows the law: This indicates that in providing a view on a question of equity, an appropriate court is expected to emphasize the law. When necessary, the court is also allowed to obtain its cue from the established elements in the common law. According to this maxim, equity follows the law emphasizing the non-allowance of illegal compensation. Therefore, the role of equity is to work as a supplement to common law.

iii. Equity does not permit the use of a statute as an instrument of fraud: This maxim prevents someone from relying on a statutory provision that often leads to third-party injustice when enforced.

iv. Equity Imputes an intention to m eet an obligation: This maxim states that individuals are likely to satisfy obligations even when the tasks are executed in a slightly different pattern, provided they adhere to the principles of equity.

The use of the trust concept is becoming increasingly relevant in Indonesia’s legal system development due to the following reasons:

i. The trust model adaptation is found in many regulations in the financial services sector, especially in banking and capital markets. The use of this model is implicitly found in several activities in the capital market, such as (a) the investment fund management based on collective contracts, where the investment manager manages all funds for the benefit of unit holders as beneficiaries, and (b) collateral fund management by the Clearing and Guarantee Institution for exchange transactions. For the banking sector, the Trust FSA Regulation also expands the services of financial institutions for them to become trustees. Therefore, all regulations governing trusts are tailored to the Indonesian legal system.

ii. The use of the trust model in Indonesia is becoming stronger with the enactment of the economic system. This indicates that the implementation of the Islamic economic system strengthens the model adoption within the country. Trust or “wali amanat” is also used in Islamic social finance, namely “waqf”. Based on Law No. 41 of 2004 concerning waqf, “Nazhir” played the role of the trustee managing the waqf fund entrusted by the “Wakif”. This trustee served as the settlor for the benefit of the “mauquf alaih” or the recipients entitled to obtain the waqf property. In this concept, the recipients are limited to social, humanitarian, and religious interests. In Indonesia, the development of waqf has progressed rapidly, especially in asset expansion and purpose. This is specifically emphasized in productive waqf, which has strategic economic dimensions contributing to poverty alleviation and national economic development, especially in building micro-enterprises. By using the waqf instrument, the challenges encountered by micro-enterprises are often addressed, such as lack of skills, low education levels, and inadequate training.48 Based on fund management, surplus productive waqf is expected to become a perpetual capital source for financing people’s needs, such as quality education and healthcare services.49 For example, waqf has emerged as government support for higher education advancement in Malaysia.50

iii. Indonesian civil law is a legacy of the Dutch policy 51, which does not recognize the dual ownership of an asset. This indicates that no legal basis is observed for a trustee as a legal owner, to manage and develop the asset/property. The Indonesian trust model is also a simple benefaction, where the trustee is only obligated to control the assets as the legal owner.52 Meanwhile, the country requires a special trust, where the trustee is able to manage the beneficial assets. This causes the suboptimal implementation of the trust model when the assets are maximally used for the benefit of the beneficiaries, for example, in the EFM requiring significant funding.

iv. Many countries with no common legal system have enacted trust laws to end the policy vacuum, especially to facilitate dual ownership in the property constitutional system. As a law source, the principles of benefaction and equity recognition are also elaborated through trust law. This law has become part of Indonesia’s positive law, which is the basis for developing the necessary trust institutions. As a country with a civil law system primarily prioritizing legislation53, the existence of trust law is used to address various issues, especially in investment and financing.

7Conclusion

Based on the abovementioned results, the fairly large gap between the availability and need for environmental funds required BPDLH to determine a management model capable of accelerating accumulation. However, the present fund management regulation and mechanism were unable to realize the goal. The trust model in managing environmental funds was also adjusted to the Indonesian legal system that did not recognize the property law acknowledging the dual ownership of assets. The legal relationships involving multiple parties and agreements mainly led to the non-optimal performance of fund management by the trustee, especially in capital fertilization. This condition hindered the need for large funding because the trustee was not entrusted to professionally and prudently manage the environmental fund. In managing the environmental fund, the trust model did not explicitly mention the environment as the beneficiary, although appointed specific individuals/institutions as the beneficial owner possessing ecological interests.

From these results, Indonesia legally needs a regular Trust Law for conceptual benefaction activities. This law could be expected to be a general regulation for all trust institutions within the country, including the trustees managing the environmental fund. It should also contain the maxim of trust, trustee requirements, and other substances generally associated with benefaction activities. Moreover, the existence of the said Trust Law would end the legal vacuum on trusts while adding an unregulated aspect to the Indonesian property policy system, namely dual ownership of assets/objects. In the proposed Indonesian Trust Law, the model to be regulated need to explicitly position the trustee as a legal owner who can be provided with the freedom to manage an asset and identify the existence of a beneficiary. As a corollary, the fund and the environment can be identified as trust assets and beneficiaries, respectively.

Notes

1 See Ministry of National Development Planning, Technical Guidelines for Preparing Action Plans - Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Edition II, 2020, p.8.

2 Law Number. 17 of 2007 concerning the 2005-2025 National Long-Term Development Plan.

3 Yenni Yoriska, Pembangunan Hukum yang Berkelanjutan: Langkah Penjaminan Hukum Dalam mencapai Pembangunan Nasional yang Berkelanjutan, Jurnal legislasi Indonesia, Vol.17, No.1,2020, https://e-jurnal.peraturan.go.id/index.php/jli/article/view/507/pdf

4 See Presidential Regulation Number 98 of 2021 concerning the Implementation of Carbon Economic Value for Achieving Nationally Determined Contribution Targets and Controlling Greenhouse Gas Emissions in National Development

5 Ministry of National Development Planning/BAPPENAS, Indonesian Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (IBSAP) 2015-2020, 2016.

6 See Government Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia Number 21 of 2021 concerning Spatial Planning.

7 Otoritas Jasa Keuangan – Sustainable Finance Indonesia, Indonesia green Taxonomy, Edition 1.0-2022, p.9

8 Otoritas Jasa Keuangan, Siaran pers -OJK Siap Dukung Penyelenggaraan Bursa karbon, SP 63/DHMS/OJK/IX/2022, https://www.ojk.go.id/id/berita-dan-kegiatan/siaran-pers/Documents/Pages/OJK-Siap-Dukung-Penyelenggaraan-Bursa-Karbon/SP%20-%20OJK%20SIAP%20DUKUNG%20PENYELENGGARAAN%20BURSA%20KARBON.pdf

9 United Nations Climate Change, National Determined Contributions Registry, https://unfccc.int/NDCREG

10 LY Sulistiawati, Indonesia”s climate change national determined contribution, a far tech dream or possible reality, The 4th International Conference on Climate Change 2019, IOP Cof. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 423 (2020), https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/423/1/012022/pdf

11 Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim-kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan, Perubahan Iklim, Perjanjian Paris, Dan Nationally Determined Contribution, Jakarta, Juni,2016, p.14.

12 Indonesia Long-term Strategy for Low Carbon and Climate Resilience 2025, 2021.

13 Nauli A. Desdiani et.al, Climate And Environmental Financing at Regional Level: Amplifying And Seizing The Opportunities, LPEM-FEBUI Working paper-067, December 2021, p. 1-17, https://www.lpem.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WP-LPEM-067_Climate_and_Environmental_Financing_at_Regional_Level.pdf

14 Natalya Yarochevich.et.al, Analysis of state of public financing of environmental protection, Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, Vol.6, No.13 (114) (2021), http://journals.uran.ua/eejet/article/view/249159/247013

15 Savitry Nur Setyorini & Emir Falah Azhari, Rsik Sharing Agreement: Sebuah Ide Awal mengenai bentuk Alternatif Pendanaan Pemulihan kerusakan Lahan Gambut Akibat kebakaran Hutan dan/atau Lahan di Indonesia, Jurnal Hukum Lingkungan Indonesia, Vol.6, No. 2, 2020, p.210-234.

16 Ahmad Muzaki. et.al, Pengendalian Kebakaran Hutan melalui penguatan Peran Polisi Kehutanan Untuk Mewujudkan Sustainable Development Goals, Litra: Jurnal Hukum Lingkungan, Tata Ruang, dan Agraria, Vol.1, No. 1, Oktober 2021, https://jurnal.fh.unpad.ac.id/index.php/litra/article/view/579

17 World Bank Group, Laporan Pengetahuan Lanskap berkelanjutan Indonesia: 1- Kerugian kebakaran Hutan-Analisa Dampak Ekonomi dari krisis Kebakaran tahun 2015, februari 2016, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/23840/Forest%20Fire%20Notes%20-%20Bahasa%20final%20april%2018.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y

18 Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan, Rekapitulasi Luas kebakaran hutan dan lahan (Ha) Per Provinsi di Indonesia Tahun 2016- 2021, http://sipongi.menlhk.go.id/hotspot/luas_kebakaran

19 Ahmad Muzaki et.al, pengendalian kebakaran Hutan melalui Penguatan Peran Polisi Kehutanan Untuk Mewujudkan Sustainable Development Goals, LITRA n: Jurnal Hukum Lingkungan, Tata Ruang, dan Agraria, Vol.1, No.1, Oktober 2021, p.23-44.

20 Adi Subiyanto, Analisis kebakaran hutan dan Lahan dari Sisi Faktor Pemicu dan Ekologi Politik, Jurnal Manajemen Bencana, http://jurnalprodi.idu.ac.id/index.php/MB/article/view/620/610

21 Fachmi Rasyid, Permasalahan dan Dampak kebakaran Hutan, Jurnal Lingkar Widyaiswara, Edisi 1, No.4, Oktober – Desember 2014, p.47-59. https://juliwi.com/published/E0104/Paper0104_47-59.pdf

22 Based on Minister of Finance Regulation No. 124/PMK.05/2020 Concerning Procedures for Managing Environmental Funds, BLU-PDLH is a non-echelon organizational unit in the management of environmental funds which is under and is responsible to the Minister of Finance through the Director General.

23 Tiza Mafira, Brurce Mecca, Saeful Muluk, Indonesia Environment Fund: Bridging the Financing Gap in Environmental Programs, Climate Policy Initiative, April 2020, p. 9.

24 I Dewa Gede Agung Ariwangsa, Ida Ayu Sukihana, Legalitas Pembuatan Trust Agreement di Indonesia, Jurnal Kertha Wicara Vol.11, No.1, 2021, pp.1-10, https://ojs.unud.ac.id/index.php/kerthawicara/article/download/81269/42612

25 This IEE Government Regulation was amended by Government Regulation No. 22 of 2021 concerning the Implementation of Environmental Protection and Management (P3LH Government Regulation). Furthermore, this P3LH re-arranges the Environmental Recovery Guarantee Fund.

26 Article 471 -472 Government Regulation No. 22 of 2021 concerning The Implementation of Environmental Protection and Management.

27 Addinul Yakin, Application of Polluter Principle for Improving Environmental Quality in the Palm Oil Industry of Malaysia: A Success Story, https://www.academia.edu/8778056/Application_of_Polluter_Pays_Principle_for_Improving_Environmental_Quality_in_the_Palm_Oil_Industry_of_Malaysia_A_Success_Story

28 Minister of Finance Regulation No.24/PMK.01/2021 Regarding Amendments to Minister of Finance Regulation No.137/PMK.01/2019 Concerning the Organization and Work Procedure of the Environmental Fund Management Agency.

29 The World Bank, Roundtable Discussion: Climate Budget Tagging and Engaging with Investors, September 13, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/events/2022/09/11/roundtable-discussion-climate-budget-tagging-and-engaging-with-investors

30 Kementerian PPN/ Bappenas, Rancangan Teknokraktik -Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Nasional 2020-2024, 14 Agustus 2019, https://www.bappenas.go.id/files/rpjmn/Narasi%20RPJMN%20IV%202020-2024_Revisi%2014%20Agustus%202019.pdf

31 Kementerian Keuangan- Direktorat Jenderal Anggaran, Optimalisasi Pendanaan Penanggulangan Perubahan Iklim, April 24, 2022, https://anggaran.kemenkeu.go.id/in/post/optimalisasi-pendanaan-penanggulangan-perubahan-iklim

32 Kementerian Keuangan, Rapat Kerja Nasional Badan Pengelolaan Dana Lingkungan Hidup Tahun 2022- Penguatan Aksi Bersama untuk Pendanaan Lingkungan Hidup berkelanjutan, 21 Desember 2022, https://www.kemenkeu.go.id/informasi-publik/publikasi/berita-utama/Menjadi-BLU-Kemenkeu-BPDLH-Sediakan-Fleksibilitas

33 Indonesia.go.id, Dibentuk Lembaga Pengelola Dana Lingkungan, 15 October 2019, https://indonesia.go.id/kategori/indonesia-dalam-angka/1214/dibentuk-lembaga-pengelola-dana-lingkungan, Accessed on 9 October 2021.

34 Ruiqiao Zhang, A Better Understanding of Dualownership of Trust Property and Its Introduction in China through Comparative Studies, Faculty of Law, McGill University, Montreal, August 2014, p.7

35 Andrew Godwin, Book Review: A Better Understanding of Common Law Ownership of Trust Property and its Introduction in China Through Comparative Studies, Australian Journal of Asian Law, Vol.22, Article No.1 : 115-117, 2022.

36 Richard Edwards & Nigel Stockwell, trust and Equity, Ninth Edition, 2009, Pearson Longman, p. 4.

37 Tri Handayani & Lastuti Abubakar, Implikasi Kegiatan Penitipan dengan Pengelolaan (Trust) Dalam Aktivitas Perbankan terhadap pembaruan Hukum Perdata Indonesia, Jurnal Litigasi, 2013, pp.2445-2487.

38 Madeleine Cantin Cumyn, reflection regarding the diversity of ways in which the trust has been received or adapted in civil law countries, Re-imagining the Trust- Trust in Civil Law, edited by Lionel Smith, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p.14.

39 Christopher D Stone, Should Trees Have Standing? Toward legal rights for Natural Objects, Southern California Law Review 45 (1972), 450-501, https://iseethics.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/stone-christopher-d-should-trees-have-standing.pdf

40 Abdurahman Supardi Usman, Lingkungan Hidup Sebagai Subjek Hukum: redifinisi rel,asa Hak Asasi Manusia dan Hak Asasi Lingkungan Hidup Dalam perspektif Negara Hukum, legality, Vol. 26, No.1, Maret – Agustus 2018, pp.1-16, https://ejournal.umm.ac.id/index.php/legality/article/download/6610/5755/17343

41 Sanket Kandelwall, Environmental Personhood: recent developments and the Road Ahead, Jurist – Legal News & Commentary, April 24, 2020, https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2020/04/sanket-khandelwal-environment-person/

42 Joko Tri Haryanto & Luhur Fajar Martha, Kerangka Hukum Instrumen Ekonomi Lingkungan dalam Upaya Penurunan Emisi Gas Rumah Kaca, Jurnal Konstitusi, Vol.14, No.2, Juni, 2017, p.262-294.

43 Tri Handayani & Lastuti Abubakar, Bank Participation in Managing Environmental Recovery Guarantee Funds to Realize the Sustainable Development Goals, Atlantis Press, Advances in Social Science, Education, and Humanities Research, Vol.358, https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/icglow-19/125920751

44 Millenium Challenge Corporation, Indonesia, https://www.mcc.gov/priorities

45 Hendra Wahanu, Dana Pewalian, Trust dan Wakaf, p. 2

46 Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, konsep-konsep Hukum dalam Pembangunan, Alumni, 2002, pp. 33-34

47 Emma Warner-Reed, Equity and Trusts, Pearson Education Limited, 2011, pp. 6-7

48 Mohamed Asmy Mohd Thas Thaher, et.al, Cash waqf model for micro enterprises’ human capital development, ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance, Vol,13, No.1,2021, pp.66-83, Emerald Publishing Limited.

49 Badan Wakaf Indonesia, Apaitu Wakaf Produktif ?, November 4, 2019, https://www.bwi.go.id/3936/2019/11/04/apa-itu-wakaf-produktif/

50 Wan Kamal Mujani et.al, Waqf Higher Education in Malaysia, International Conference on Education, E-Learning and Management Technology (EEMT 2016), p.519-522.

51 The Civil Code is enforced by Staatblad Number, 23 of 1847 and until now it is still Indonesian positive law that regulates civil affairs.

52 Jargalsaikhan Oyuntungalag, Trust Law Concept Challenging Civil Law System: Mongolian Example, Scientific research Publishing, Beijing Law Review, 2022,13, https://www.scirp.org/journal/blr

53 Dhaniswara K Harjono, Pengaruh Sistem Hukum Common Law terhadap Hukum Investasi dan Pembiayaan di Indonesia, lex Jurnalika, Vol.6,No.3,2009