The Cost of Climate Change Heightened Sexual and Gender-based Violence: A Challenge for International Law

Abstract

There is a reality of creeping adverse effects of climate change. The human imprint on it has been affirmed by various global processes including 21 May 2019 recognition by the Anthropocene Working Group. It has emerged as a planetary crisis. By 2050 climate change could see 4% of global annual economic output lost to the tune of $23 trillion and may hit many poorer parts of the world disproportionately. Though entire populations are affected by climate change, women and girls suffer the most. Due to their traditional roles, women are heavily dependent on natural resources. As a consequence of natural disasters and during Covid-19 pandemic in 2020-22, women have faced heightened risks to different forms of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). They suffer from a lack of protection, privacy, and mental trauma. Effects of climate change results in the feminization and intensification of vulnerability of women and girls. As there is double victimization of women both as human beings and because of their gender. Growing evidence suggests role of climate change heightened violence against women and girls. There is no specific international legal instrument dealing with SGBV against women during and after the climate change induced disasters. The texts of the three specific climate change treaties (1992 UNFCCC, 1997 Kyoto Protocol and 2015 Paris Agreement) do not address this crucial aspect. It has been given attention only through the recent decisions of the Conference of the Parties (COP). Due to serious psychological and bodily harm SGBV causes to women, it needs to be explicitly factored in respective international legal instruments on climate change and disasters. There are ignorance, denials and lack of adequate attention by scholars and decision-makers in the field to address adverse effects of climate change in causing heightened violence against women and girls. Hence, this study makes a modest effort to deduce and analyze –from scattered initiatives, scholarly literature in different areas, existing international legal instruments and intergovernmental processes – the growing causal relationship between climate change and SGBV especially against women and girls as well as the phenomenal cost so as to suggest a way out for our better common future. It is a new challenge for international law that needs to be duly addressed in a timely manner.

1Introduction

After 30 years of the adoption of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), climate change has emerged as one of the predominant challenges on a planetary scale. As warned by the UN Secretary General, in 02 June 2022 address to Stockholm+50 Conference, “a climate emergency is killing and displacing ever more people each year”.1 The Anthropocene Working Group2 also affirmed (on 21 May 2019), an unmistakable imprint of human activities as the new Anthropocene epoch. The rising global temperatures cause sea levels to rise, and increasing extreme weather events result in natural calamities such as floods, droughts, storms and the spread of diseases. The climatic changes have construed as responsible for spread of infectious diseases. These profoundly cause effects on human lives, especially on health, livelihood, and security.3 In view of this gender dimensions of climate change have assumed vital significance.4 SGBV itself results in huge economic loss. However, due to climatic changes the economic cost gets heightened. This study has sought to exactly explain as to how do climate change and SGBV individually cause economic loss for the States as well as how climate change causes heightened SGBV. Both result in phenomental economic losses.

2Gendered Effects of Climate Change

Climate change induced displacement and resource scarcity, especially in armed conflicts, results in the feminization and intensification of vulnerability of women and girls. Natural disasters affect different regions with different intensity. Climate change emerging as one of the important contributing factors.5 Death, injury, destruction of homes, hospitals, schools, and other infrastructure are the common consequences of a natural disaster.6 Apart from climate change becoming a global environmental problem, for many of women it is a direct cause that heightens the risk of different forms of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The gender-based violence has assumed grave proportions with one in every three women facing sexual violence at least once in their lifetime.7 This gets heightened during climate change driven contingencies. In a briefing to the UN Security Council on 2 November 2022, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (Filippo Grandi) explicitly underscored that the responses “to climate change must also consider its link to both conflict and the displacement it causes.”8

The UN Human Rights Council Special Rapporteur on violence against women (causes and consequences), Reem Alsalem, in presenting her report9 (on 05 October 2022) to the 77th UN General Assembly, considered climate change as: “the most consequential threat multiplier for women and girls, with far-reaching impacts on new and existing forms of gendered inequities”. She observed that the “cumulative and gendered consequences” of climate change and environmental degradation “breach all aspects” of women’s rights.10 She explained the basic premise of the phenomenon as follows:

“When slow or sudden-onset disasters strike and threaten livelihoods, communities may resort to negative coping mechanisms, such as trafficking, sexual exploitation and harmful practices like early and child marriage and drop out from schools –all of which force women and girls to choose between risk-imbued options for survival”.11

There is very sparse literature as regards role of climate change as a factor that heightens risk of violence against women and girls. The general legal framework relating to climate change and environmental protection does not specifically address the gender issues. Some related international legal instruments dealing with women’s human rights applicable during peace, conflict, and post-conflict situations implicitly deal with the issue.12

There is no specific international legal instrument that deals with SGBV including heightened by climate change. Therefore, this study has sought to put together and analyze the facts, incidents, circumstantial evidence, processes as well as statements and decisions of the intergovernmental bodies. The primary focus of this study is to analyze the inter-linkages and causal relationship between climate change heightened violence against women and girls. How does climate change exacerbate SGBV against women? What are the costs of climate change and SGBV? How does the cost of SGBV get hightened because of climate change? What are the relevant international legal instruments relating to climate change? How do we address the challenge of SGBV in the era of climate change? These questions need to be grappled by the scholars and the decision-makers alike. Hence, the study provides a modest scholarly gaze into the future.

3How Does Climate Change Heighten Violence against Women?

Even in the third decade of the 21st century, SGBV remains a taboo, spoken in whispers and suffered in silence.13 Though women, men, and LGBTIs are subjected to SGBV, majority of the victims remain women and girls.14 Women and girls are subjected to various forms of SGBV within and outside the family. In such circumstances, change of environment by an external phenomenon –such as climate change –pushes them into a more vulnerable position. The existing gender inequalities get heightened during emergencies such as disasters and pandemics, calamities and conflicts15 especially when climate change results in gender-differentiated impacts.16 The 2020 report by CARE buttressed the linkage that “all forms of gender-based violence against women and girls spike during disaster and conflict” and the “climate extremes exacerbate existing inequalities, vulnerabilities and negative gender norms.”17

The growing worldwide evidence shows that SGBV against women increases during and after disasters.18 For example, in 2022, thousands of women and girls became homeless in Philippines due to typhoon and torrential rain. The humanitarian aid agencies have witnessed that:

Women and children are especially vulnerable to gender-based violence and sexual exploitation in the aftermath of sudden-onset disasters, particularly in cramped evacuation centres and camps with little electricity and scarce water sources, as they must venture long distances in the dark to get water.19

Similarly, in 2020, women and girls in Bangladesh faced heightened violence during monsoon floods. They were already subjected to violence during confinements due to Covid-19 pandemic, but the floods aggravated it.20 The UN Secretary General’s remarks to the Security Council on 23 February 2021 graphically underscored that the climate-related exigencies expose women and girls to violence when they need to walk long distances for collection of fodder, fuelwood and drinking water.21 In Malawi, climate change induced drought and food shortages force minor girls into marriage to reduce family burdens. The trafficking of girls and women and other forms of SGBV have considerably grown due to disasters in South Asia, especially in Nepal.22During droughts and prolonged dry spells, Ugandan women faced domestic violence, child marriage, rape, female genital mutilation (FGM), and other harmful practices. These experiences have also been faced by women, including evacuees and volunteers, during earthquakes and cyclones even in advanced countries such as Japan and the United States.

The periods of disasters including climate change related migrations or displacement have shown women and girls face more domestic and sexual violence. This attains an acute form when families have been displaced and forced to live in camps or other places without privacy. Women and girls report a high level of sexual violence during sleep, washing, bathing, and dressing in emergency shelters, tents, or camps. Poor and marginalized women have less adaptive capacities due to fewer resources and lesser access to law, policy and decision-making processes in the wake of climate change induced disasters, displacements and conflicts. Thus, women and girls suffer more and easily get exposed to all forms of violence.23

Apart from this, women and girls suffer high levels of mortality and morbidity during the crisis. Due to their traditional roles, women are heavily dependent on natural resources. The scarcity of natural resources due to climate change and natural disasters forces women and girls to go far and take different risks to collect food, firewood and water. In turn, this places an economic burden on the women and girls that heighten their vulnerability and risks to various forms of violence within and outside the family.24 In 2016, UNESCO highlighted violence against women in the context of climate change thus:

“Nothing the myriad of ways in which climate change disproportionately affects women, whether via disasters or climate-induced displacement causing highlighted sexual trafficking or the search for water and firewood resulting in increased rapes”.25

Thus, existing gender inequalities get heightened and new forms of SGBV emerge during and after climate change induced disasters and emergencies. The resultant violence against women and girls is akin to the risks they face during armed conflicts.26 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “changes in infectious disease transmission patterns are likely major consequences of climate change.”27 It shows that climate change directly contributed in spread, pattern and migration of diseases to new areas. The food crisis arising from climate change induced extreme weather conditions push human beings to find alternative sources of food. It exposes them to come into contact with animals and infectious diseases such as SARS, H5N1 avian flu, H1N1, and Covid-19 (since 2020).28 As a result, there is a crisis of the clean environment, food, water, and other essential services to fight pandemic and epidemic.29 As seen during the 2020-2022 pandemic, there is absence of money, security and other necessary services30 that contributed in spiraling growth of domestic violence, intimate partner violence, and child sexual abuse. The older women, girls and disabled women face additional risks.

The other interlinkages have been established between climate change, scarcity of natural resources, conflicts and SGBV in the reports of the UN Secretary-General (23 February 2021); the ICRC (17 September 2020) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (2020). It has been recognized that women bear the greatest burden of climate emergencies and they do not have equal rights. In turn, it places them at greater risk of SGBV.31 The 2022 UNDRR report has clearly highlighted incidents of SGBV during and after the disasters.32 A UNEP report on conflict to peace building33 has also graphically shown the close connection between natural resources related conflicts and the environment.34

Unsustainable use of natural resources combined with environmental degradation like climate change contributes to the outbreak of armed conflicts.35 Similarly, climate change and natural disasters cause damage and scarcity of natural resources that lead to further conflicts. Cumulatively, as a consequence of climatic changes and conflicts, there is exacerbation of SGBV against women. Often, like in any traditional war, SGBV has been used as a weapon of war to control natural resources as well as to defeat the opponent groups during conflicts. The result ultimately remains the same: women’s bodies become the battleground.36

4Cost of Climate Change Heightened SGBV

The climate related hazards are having multifaceted impacts on lives and livelihoods since the “impacts experienced in one country and the response to those impacts can impose threat beyond its borders”. The people and Sates face economic, social and political stress. People have started facing both economic and non-economic losses e.g. psychological or mental health impacts of extreme and slow onset events, loss of land and culture, identity and security, health, family members, sense of safety, displacement, loss of home, income, production especially agriculture, capital loss, and so on. It is estimated that because of climate change more than 130 million may be pushed into poverty by 2030. There would be disproportionate effect based on race, gender, age, etc. The future generation will carry the burden. Though the economic losses can be measured but the intangible non-economic losses are very difficult to measure.37 Thus, according to the 2022 report of UNDRR:

On a global level, the dollar value economic loss associated with all disasters –geophysical, climate and weather-related –has averaged approximately $170 billion per year over the past decade, with peaks in 2011 and 2017 when losses soared to over $300 billion . . . Low-income and lower middle-income countries lose on average 0.8–1% of their national GDP to disasters per year, compared to 0.1% and 0.3% in high-income and upper middle-income countries, respectively . . . 38

Similarly, a report of 28 April 2022, published in REUTERS, states:

Climate change could see 4% of global annual economic output lost by 2050 and hit many poorer parts of the world disproportionately hard, a new study of 135 countries has estimated . . . Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka’s exposure to wildfires, floods, major storms and also water shortages mean South Asia has 10% -18% of GDP at risk, roughly treble that of North America and 10 times more than the least-affected region, Europe. Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa regions all face sizable losses too.39

In the same vein, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has estimated that climate change presents major threats to long-term economic growth of the countries. It has direct and indirect impact on the economy of the counties, mostly large number of lower income countries are at risk.40 A report in New York Times (2021) has predicted that the climatic change from rising temperatures is likely to substantially reduce global wealth in the coming years. As a corollary, the world economy may face huge economic losses due to climate change to the tune of $23 trillion in 2050 and the “effects of climate change can be expected to shave 11 percent to 14 percent of global economic output by 2050 compared with growth levels without climate change”.41

Thus, it is clear that SGBV due to climate change imposes double economic burden on States. In an ominous sign, in some countries, the cost of SGBV is staggering and it accounts for up to 3.7% of the GDP. It is more than double what most of the States spend on education.42 It shows gravity of this simmering global challenge of our times. SGBV against women underscores an extreme level of human rights violation. It causes a huge economic loss for the women, families, communities, and the States. At the 57th Session (2013) of the Commission on the Status of Women, it was accepted that “violence against women results in social and economic harm.” In a shocking revelation, it was shown that “the cost of violence could amount to approximately 2% of the global GDP, i.e., equivalent to 1.5 trillion”.43

It is the societies and States that pay the cost by spending money for the health system, counseling, welfare support, justice system, and other related services. Moreover, the States pay the indirect cost by loosing wages, employment, productivity etc. On the other hand, SGBV against women has a negative impact on women’s participation in education, employment, and social life. As they remain highly susceptible to the impacts of natural disasters and the adverse effects of climate change and, in turn, are “more vulnerable and suffer chronic hunger, malnutrition and sexual violence”.44 Thus, it calls for a sizeable amount of money and resources for the social service, justice mechanism system, health care services, peacebuilding,and resettlement processes. In fact, SGBV is one of the biggest barriers in achieving the agenda of the SDGs 2030 for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. In conditions driven by events such as pandemics, epidemics and climatic conditions, there is heightened risk of violence against women. The Deputy Executive Director of the UN Women has succinctly underscored this inevitable linkage and attributed huge economic costs in select countries as:

Annual costs of intimate partner violence were calculated at $5.8 billion in the United States of America and $1.16 billion in Canada. In Australia, violence against women and children costs an estimated $11.38 billion per year. Domestic violence alone costs approximately $32.9 billion in England and Wales. Research indicates that the cost of violence against women could amount to around 2 per cent of the global gross domestic product (GDP). This is equivalent to 1.5 trillion, approximately, the size of the economy of Canada.45

Such aggraveted costs call for robust support structure for the survivors of SGBV such as access to medical care, psychological support, economic reintegration, income generating activities, vocational and literacy training, legal assistance to fight against impunity for the perpetrators, awareness campaign, etc. This would require a huge amount of economic resources to ensure that the survivors can live with basic human dignity.

5International Law Mechanisms

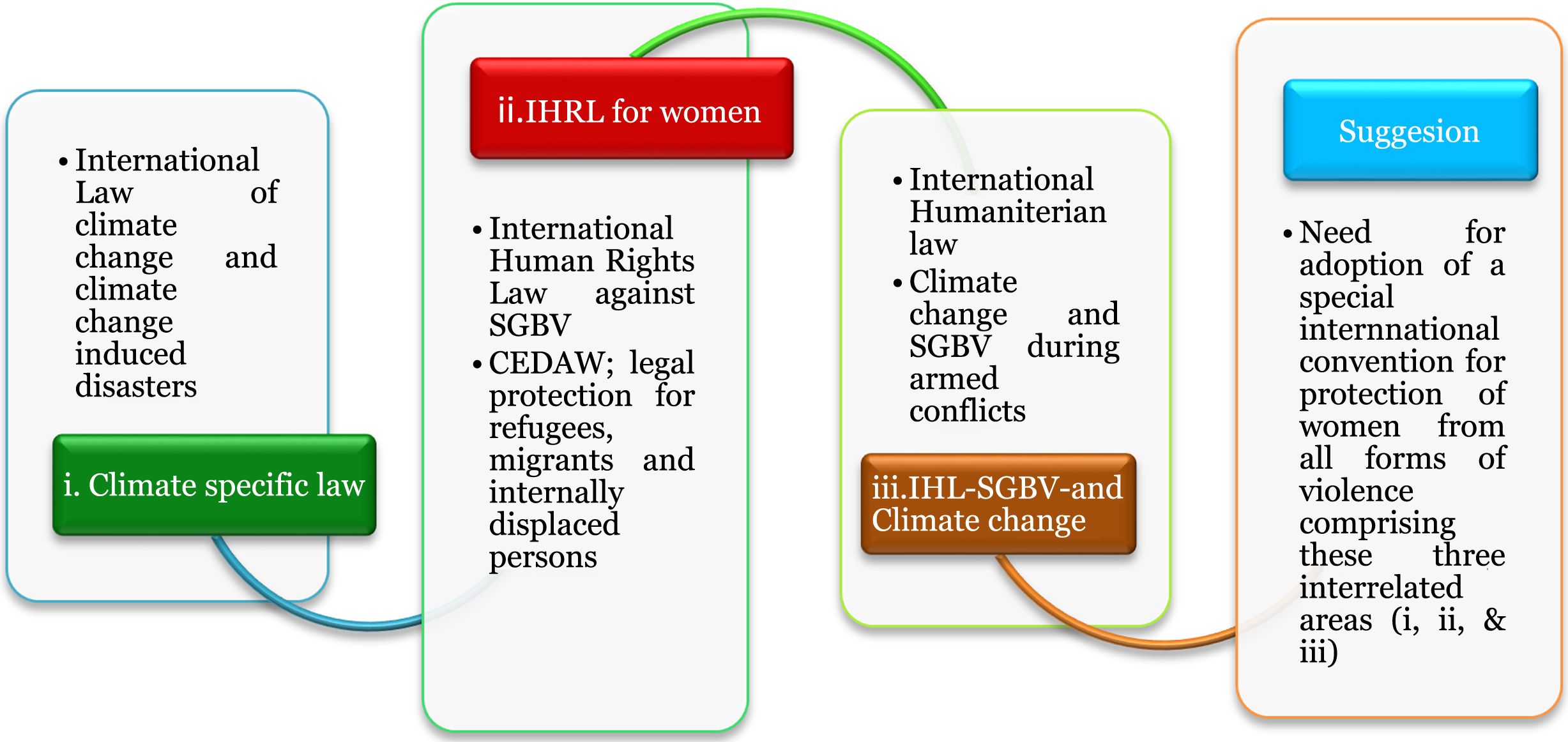

There is no international legal instrument that directly deals with violence against women during and after natural disasters and climate change. Moreover, there is no specific international legal instrument to address man-made or natural disasters. The 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) remains the primary global convention to deal with climate change as a common concern. Still, the UNFCCC does not address the issue of violence against women or gender issue per se. Some international instruments deal with the human rights and are applicable to the women affected by climate change during peace, conflicts and post conflict situations46 as “climate change affects women and men differently”.47 For example, the 1989 CEDAW (Article 3),48 the 1951 Refugee Convention49 the 1966 Covenant of Civil and Political Rights;50 the 1966 Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (Article 7)51 and the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.52 The inter-linkages cut across different areas of international law (climate change, human rights and humanitarian etc.) are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1

Showing the inter-linkage between the climate specific and other related laws to dealing with climate change heightened SGBV against women and girls.

The UN Security Council resolution 1325 (2000)53 called for equal and full participation of women in the promotion of sustainable peace and security as well as incorporation of a gender perspective in peacekeeping operations. With climate change emerging as a major factor in armed conflicts, women will be directly affected party. Hence, their role as a major stakeholder in conflict prevention and peace agreements will need to be inevitable. In fact, all the laws relating to climate change, SGBV and international humanitarian law are interconnected (see Desai et al. 2021).54 This part will discuss only the subject specific international law relating to climate change and will see how it has been including the issues relating to gender, and SGBV.

Though the history of international law on climate change started with the 1972 Stockholm Conference that laid down the mandate, full 20 years before the 1992 UNFCCC as follows:

“It is recommended that Governments be mindful of activities in which there is an appreciable risk of effects on climate, and to this end: (a) Carefully evaluate the likelihood and magnitude of climatic effects and disseminate their findings to the maximum extent feasible before embarking on such activities; (b) Consult fully other interested States when activities carrying a risk of such effects are being contemplated or implemented”.55

However, the issue of gender inclusion especially SGBV is very new and has come into vogue only recently. There has been participation of both men and women in the international law-making process and certain amount of gender sensitivity has been at work. Still, at the nascent stage of global environmentalism, the opening lines both in the preface (Paragraph 1) and the principles (Principle 1) of the Stockholm Declaration still used the word “Man”,56 unlike the stage already set way back in the 1948 UDHR by use of the words “human beings” (Principle 1).

5.1Multilateral Environmental Agreements

The following section examines as to how some of the multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs)57 have addressed the impact of climate change on women and girls. Within the limits of time and space, this study analyzes three of the MEAs that were designed in the wake of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit: the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),58 the 1992 Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) and the 1994 UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD).

5.5.1.1(i) UNFCCC

The UNFCCC and its 1997 Kyoto Protocol59 did not address gender issues or SGBV. The Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC later on started the agenda on gender issues. This can be traced to Decision 36 of the COP 7 (2001) that was specifically titled as: “Improving the participation of women in the representation of parties in bodies established under the UNFCCC or the Kyoto Protocol.”60 In order to do so, it had to draw the mandate from the 1995 Beijing Declaration that stressed women’s empowerment and their full participation in climate change decision-making. It was the initiatives of the women’s organizations, and civil society groups that brought gender issues to the portal of the UNFCCC. As a result, the Women and Gender Constituency (WGC)61 was established in 2009 as UNFCCC’s one of the nine stakeholder groups for women’s rights. Subsequently, this advocacy of WGC was supported by the UN entities and the Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC.62 It took the initiative for gender equality and women’s rights by linking with human rights. Subsequent COPs (for space constraints, only a few COPs have been referred here) have drawn relevant references from decisions of other institutions on role of women in combating climate change.

In 2010, COP 16 (decision 1)63 referred to resolution 10/4 of the UN Human Rights Council on human rights and climate change. It recognized the adverse effect of climate change as an obstacle to the effective enjoyment of human rights. It recognized the need for gender equality and the effective participation of women for taking action regarding all the aspects of climate change.64 It affirmed enhanced action on adaptation based on the ‘gender-sensitive’ approach.65 It also considered women as a vulnerable group to address the inter-linkage between climate change response and social and economic development by the developing countries.66

In 2012, COP 18 (decision 23)67 sought gender-balanced participation of women in UNFCCC negotiations and the representation of the parties in various climate change bodies. It acknowledged women’s empowerment in the context of global climate change regulatory processes to inform and respond to ‘gender-responsive climate policy’ and gender balance in the bodies and women empowerment through their representation or participation.68 It was followed up at COP 20 (2014), that led to the Lima work program on gender.69 It underscored the coherence between the participation of women, the adoption of gender-responsive climate policies, provisions of the CEDAW and the Beijing declaration. It used soft terms such as ‘need’, ‘request’ to the secretariat, and ‘encourages’ the parties. However, the Lima decision did not define the “gender-responsive climate change policy”.

The advent of the 2015 Paris Agreement (Decision 1/21),70 reaffirmed climate change as a common concern of humankind. It emphatically required the parties to consider gender equality and women’s empowerment while taking any climate related action.71 It was expected to take into account the goal of gender balance [Article 15 (2)] 72 and called for gender-responsive action under Article 7.5.73

Subsequent COP meetings have embarked upon more focused attention to gendered approach. As a result, 2016 COP 22 (Decision 21)74 underscored the importance of coherence between gender-responsive climate policies and the balanced participation of women. It requested for a special subsidiary body for implementation of the gender action plan, gender-related decisions and mandates under the UNFCCC (paragraph 27).75

As a corollary, the 2017 COP 23 (Decision 3)76 brought in the Gender Action Plan (GAP) to address the requirement of gender-responsive climate policy. GAP was added as an annexure to this decision. It reiterated the call for (as per Decision 21/COP 22) special subsidiary body to implement GAP for gender-responsive policy and mainstreaming gender at all levels.77 During COP 24 (2018), a workshop report was presented on “the differentiated impacts of climate change and gender-responsive climate policy and action, as well as policies, plans and progress in enhancing gender balance in national delegations.”78 The COP confirmed commitments to review and strengthen the GAP, and Lima work program on gender as a part of COP 25.79

As a result of series of decisions of the previous COPs, the 2019 COP 25 (decision 3) spelled out a detailed report on Enhanced Lima Work Programme on Gender and its Gender Action Plan.80 The decision acknowledged the need for mainstreaming gender through all relevant targets and goals in the UNFCCC work, importance of Lima work program on gender and GAP. It recognized that climate impacts women differently because of historical, multidimensional, and gender inequality factors. Moreover, the design and implementation of gender-responsive climate actions are based on capacity building, knowledge management, sharing of experience to relevant actors.81 At the Glasgow COP 26 (2021), one of the agendas (item 13) was on ‘gender and climate change’.82 It decided to review Lima work program at the fifty-sixth session of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation.83 It remains to be seen what COP 27 (2022),84 scheduled to be held during 6-18 November at Sharm el-Sheikh (Egypt), does on the gender and climate change issue.

5.5.1.2(ii) UNCCD

The 1994 UN Convention on Combating Desertification (UNCCD), has recognized women’s role and knowledge in addressing climate change:

“Stressing the important role played by women in regions affected by desertification and/or drought, particularly in rural areas of developing countries, and the importance of ensuring the full participation of both men and women at all levels in programmes to combat desertification and mitigate the effects of drought”.85

It has stressed the role of the women in the regions affected by drought or desertification as well as for equal participation in combating desertification. Article 5 (d) of the UNCCD provides for obligations of the States to “promote awareness and facilitate the participation of local populations, particularly women and youth . . . in efforts to combat desertification and mitigate the effects of drought.” Moreover, Article 10 and Article 19 describes women and girls (along with men) as “resource users”. However, the UNCCD also does not deal with the issue of SGBV as a direct outcome of desertification or drought.86

The 2015 COP 12 (Decision 29) came out with the Ankara initiative87 that called for specific actions regarding mainstreaming gender in implementing the UNCCD.88 It reiterated the growing global understanding that women are subjected to discrimination and violence, remain underrepresented in political and economic decision-making processes and as such lag behind in achieving the goals of SDGs 2030 and land degradation neutrality (LDN).89

As a follow up, the 2017 COP 13 (Decision 30),90 decided to “pledge to address gender inequalities which undermine progress in the implementation of the Convention.” It included ‘gender-responsive’ implementation at all levels. In fact, COP 13 became a benchmark with the adoption of UNCCD’s Strategic Framework 2018–2030 comprising gender equality, women’s empowerment and gender-responsive implementation.91 The usage of soft normativity through terms such as request, invites, acknowledge, emphasize, provide etc. persuasive tools within a global convention, in essence, reflects “softness of hard law.”92

5.5.1.3(iii) CBD

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)93 has recognized the “vital role that women play in the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity” and affirmed the “need for the full participation of women at all levels of policy-making and implementation for biodiversity conservation” (preamble to 1992 CBD and 2010 Nagoya Protocol). The gender consideration is important to stop the loss of biodiversity and loss of important traditional knowledge and experience that have a close link with food security (Articles 12, 21, 22, 25 of the Nagoya Protocol).94 The COP-10 (Decision X/19, 2010), specifically emphasized the importance of gender mainstreaming in all program of work under the Convention.95

5.2Resolutions, declarations and agendas

Resolution of the UN Human Rights Council 47/24, 2021 on human rights and climate change is one of the major official moves towards SGBV and climate change. It has referred CEDAW and Vienna Declaration and stressed participation of women and girls in climate action. It requested States to take gender-responsive approach for climate adaptation and mitigation.96 As a result of the resolution 47/24, UNHRC, on 1 May 2022, Mr. Ian Fry has been appointed by the Human Rights Council as the first Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change. His mandate started on 1 May 2022 (48th session in October 2021; RES/48/14).97 It has accepted the adverse effect of climate change on women and mandated to adopt gender responsive approach to climate change.

Principle 20 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development,98 accepted that “Women have a vital role in environmental management and development. Hence, the full participation women are essential to achieve the goals of sustainable development. The 2000 World Summit on Sustainable Development (Johannesburg)99 also reaffirmed100 the 1992 Agenda 21. Chapter 24 of the Agenda 21 that deals with global action for women towards sustainable and equitable development seeks to ensure equal access and full participation of women in decision making and analysis regarding the structural linkage between gender relations, environment, and development. It also provides for taking measures regarding the environment and gender impacts analysis (Chapter 24.8). Some objectives are suggested for the national Governments to consider adoption as well as strengthening and implementation of legislations to prohibit all forms of violence against women:

“The following objectives are proposed for national Governments: h. To consider adopting, strengthening and enforcing legislation prohibiting violence against women and to take all necessary administrative, social and educational measures to eliminate violence against women in all its forms.”101

The central thrust of Chapter 24 of Agenda 21 is to ensure that “gender considerations are fully integrated into all the policies, programmes and activities”.102 It enjoins upon the countries to take and urgent action for preventing impacts of environmental degradation and natural disasters such as climate change on the lives of women in rural areas of developing countries.103

Women are treated as victims and one of the most vulnerable groups. Still, the participation of women in decision-making processes is not considered so essential. They do disproportionately face impacts of the climatic changes that heightens violence against them. There is still not much awareness as regards adverse effects of climate changes and environmental degradation on women. Both the Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 are non-binding international instruments. As such the terms used remain soft such as: “women should be fully involved in decision making” (Rio Principle 20) etc.104 The Hyogo Framework for Action (2005-2015) was adopted in the World Conference on Disaster Reduction (Kobe in Hyogo, Japan). It explicitly incorporated gender aspects in disaster planning and response:

A gender perspective should be integrated into all disaster risk management policies, plans and decision-making processes, including those related to risk assessment, early warning, information management, and education and training”.105

As a sequel, the 2015 Sendai Framework (2015-2030) in its assessment of grim situation observed that “more than 1.5 billion people have been affected by disasters in various ways, with women, children and people in vulnerable situations disproportionately affected. The total economic loss was more than $1.3 trillion”.106

This has been reaffirmed in 2022 report of the UN Secretary-General that highlighted disproportionate effect of climate change on women and girls. It underscored that:

gender inequality and the unequal access of women to land and natural resources, finance, technology, knowledge, mobility and other assets constrain the ability of women to respond and cope in contexts of climate and environmental crises and disasters . . . The lack of data disaggregated by sex and gender statistics is one of many factors that render women and girls and their needs and priorities invisible to policymakers107

Thus, as a result, child marriage, labour discrimination, gender-based violence are faced by women and girls. The suggested solutions include an active participation of women in decision making and climate action, gender responsive social protection system, strengthening the gender-environment nexus and filling data gaps in the gender environment nexus.108

5.3Environmental events

In 2002 the High-Level Roundtable on gender and climate change109 focused on How a Changing Climate Impacts Women. It was one of the first notable events that directly focused on the linkage between gender equality and climate change. The event was in anticipation of the UN Secretary-General’s high-level climate change event. The linkage between gender and climate change is a matter of human rights, justice, and human security.110 The international and national legal frameworks need to address gender issues through human rights treaties such as the CEDAW to give a new dimension to the structure of international environmental governance. The roundtable recommended some suggestions for the Governments. One of the important suggestions was, including the issue in the agenda of Bali COP13. But it did not happen.111 At the 7th meeting of the COP and 8th meeting of the CMP, representative of nongovernmental organizations addressed the issue relating to “women for climate justice and gender.”112 The governments needed to strengthen the global agreements that indirectly address the effect of climate change on women. It calls for a proper analysis and identification of gender-specific impact and protection measures to deal with floods, droughts, diseases, heat waves, and other environmental contingencies. In fact, the UNFCCC secretariat need to design and follow an appropriate strategy to this effect.

6What needs to be done?

In view of the above discussion, it appears that many of the challenges are yet to be identified as regards the status of climate change induced effects including violence against women and girls. The internally displaced, refugees and stateless people are more vulnerable. In cases of climate induced cross-border displacement, the situation becomes complicated due to apparent legal gap in providing protection especially to the women victims. As already seen earlier, the existing legal protection regime (under existing frameworks of IEL, IHRL, IRL and IHL) are very weak and grossly inadequate to meet the challenge of climate change heightened SGBV against women. It calls for attention of the scholars and decision-makers to squarely address the growing global menace.113

It now appears that there is a lack of gender-specific expertise on climate change and sustainable development issues at the international, regional, and national levels. That presents a collective challenge for all, especially relevant international institutions engaged in addressing gender dimensions of climate change.

Therefore, the growing evidence and significance of exacerbation of SGBV from climate change induced events, require: (i) explicit determination of the status of the climate change-induced displaced people (ii) need for lex specialis in the form of a global convention to address climate change-induced and heightened violence against women (iii) need for a global institutional structure to forge close coordination among various institutions in the areas of environment (IEL), human rights (IHRL), refugees (IRL) and humanitarian (IHL) realms, within and outside the UN system to provide well-coordinated protection to women and girls (iv) the UN member states need to adopt a special law to address situations and effects of climate induced disasters that heighten and exacerbate SGBV against internally displaced women and girls. (v) There should be gender-sensitive disaster management plans and full participation of women in the decision-making processes to ensure rights-based protection and justice114

7Conclusion

Women face different forms of climate change induced violence during and after all the disasters, extreme events and conflicts. They are doubly victimized especially due to their gender. It calls for an urgent international (and national) legal and institutional mechanism to squarely address this emerging challenge. It has serious implications for the national societies, maintenance of international peace and security as well as for the international legal protection under environmental, human rights, refugee and humanitarian law systems. The role of climate change in heightened violence against women needs to attain high priority especially in the decision-making process of the UNGA, the UNSC, the ICRC, the UNHCHR, the OHCHR, the UNDP, the CEDAW Committee and UNEA to address the growing challenge in a timely and effective manner. As discussed earlier, an indication of such a pathway can be found in the adoption of Gender Action Plan and the Lima Work Program on Gender115 adopted COP 25 (Madrid, December 2019). It is hoped that other agencies will follow this approach and work in concert to bring to fruition a time-bound action plan to address climate change-induced and exacerbated violence against women and girls for our better common future. The sheer economic cost of climate change, estimated $23 trillion in 2050, will be too heavy for the people and the planet. Hence, it calls for invoking and taking the instrumentality of international law seriously at this critical juncture of the climate change challenge on a planetary scale.

Endnotes

1 UN (2022), Secretary general’s remarks to Stockholm+50 international meeting, 02 June 2022; available at: Secretary-General’s remarks to Stockholm+50 international meeting | United Nations Secretary-General (accessed on 3 November 2022).

2 UNESCO (2016), “Climate change is a threat multiplier for women and girls”; available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/unesco/themes/gender-equality/resources/single-view-gender/news/climate_change_is_a_threat_multiplier_for_women_and_girls/(accessed on 28 June 2022).

3 UNICEF (2003), “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Refugees, Returnees, and Internally Displaced Persons: Guidance for Prevention and Response”; available at: https://www.unicef.org/emerg/files/gl_sgbv03.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

4 Institute of Development Studies (2011), “Gender and Climate Change”, Bridge Bulletin: In Brief, Issue 22, November 2011; InBrief22-Climate Change-ForWeb (ids.ac.uk) (accessed on 28 October 2022).

5 UNFCCC (2019), “Climate Change Increases the Risk of Violence against Women”; available at: https://unfccc.int/news/climate-change-increases-the-risk-of-violence-against-women (last visited on 28 June 2022); Also see, IPCC (2018), Special report: Global Warming of 1.5°C; available at: Global Warming of 1.5°C —(ipcc.ch) (accessed on 28 October 2022).

6 CARE International (2018), “Suffering in Silence: The 10 most under-reported humanitarian crises of 2016”; available at: Report_Suffering_In_Silence.pdf (care-international.org) (accessed on 21 October 2022)

7 UNFPA (2021), “Gender-based violence”; available at: Gender-based violence (unfpa.org) (accessed on 28 October 2022).

8 UN (2022), “UN refugee chief calls for greater focus on climate and conflict factors”, UN News, 2 November 2022; available at: UN refugee chief calls for greater focus on climate and conflict factors | | 1UN News (accessed on 3 November 2022).

9 UN (2022), Report of the Special Rapporteur (Reem Alsalem): Violence against women and girls in the context of the climate crisis, including environmental degradation and related disaster risk mitigation and response; UN Doc. A/77/136 of 11 July 2022; N2241807.pdf (un.org) (accessed on 3 November 2022)

10 UN (2022), “Climate change heightens threats of violence against women and girls”, UN News, 5 October 2022; Climate change heightens threats of violence against women and girls | | 1UN News

11 Ibid.

12 UN (1979), The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW); UN Treaty Series, vol. 1249, 1980, p.13; available at: Chapter IV. Human Rights (un.org) (accessed on 21 October 2022).

13 Susana T. Fried (2003), “Violence against Women”, Health and Human Rights 6 : 88-111

14 UNHCR, “Sexual and Gender-Based Violence”; available at: UNHCR - Gender-based Violence (accessed on 28 October 2022)

15 Ibid

16 UNDP (2017), Gender, climate change and food security, 20 September 2017; available at: Gender and Climate Change | United Nations Development Programme (undp.org) (accessed on 4 November 2022)

17 CARE International (2018), n.6

18 UN Women, Climate Change, Disasters and Gender-Based Violence in the Pacific; available at: unwomen701.pdf (uncclearn.org) (accessed on 4 November 2022)

19 UNFPA (2022), “Crisis after the storm: needs soar for women and girls in typhoon-ravaged Philippines”, 3 February 2022; available at: Crisis after the storm: needs soar for women and girls in typhoon-ravaged Philippines (unfpa.org) (accessed on 4 November 2022).

20 UNDRR (2022), United Nations Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction –Our World at Risk: Transforming Governance for a Resilient Future; available at: https://www.undrr.org/gar2022-our-world-risk#container-downloads (accessed on 4 August 2022); BRAC, CARE, Oxfam, “Preliminary Rapid Gender Analysis of Monsoon Flood 2020 (Gender in Humanitarian Action Working Group - Bangladesh)”; available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/preliminary-rapid-gender-analysis-monsoon-flood-2020-gender-humanitarian-action (accessed on 4 August 2022).

21 Masson, Virginie Le, et al (2016), “Disasters and violence against women and girls: Can disasters shake social norms and power relations”; working papers, Overseas Development Institute; available at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/11113.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022)

22 Ibid.

23 UNICEF (2003), n. 3

24 IUCN (2020), Environmental degradation driving gender-based violence –IUCN study; available at: https://www.iucn.org/news/gender/202001/environmental-degradationdriving-gender-based-violence-iucn-study (accessed on 3 August 2022).

25 UNESCO (2016), “Climate change is a threat multiplier for women and girls”; available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/unesco/themes/gender-equality/resources/single-view-gender/news/climate_change_is_a_threat_multiplier_for_women_and_girls/ (accessed last 28 June 2022)

26 Institute of Development Studies (2008), Gender and Climate Change: Mapping the linkages, BRIDGE; BRIDGE | Gender and development research and information service supporting change for dignity, justice and equality (ids.ac.uk) (accessed on 23 October 2022)

27 McMichael, A.J, et. al (2003), Climate change and human health: Risks and Responses, WHO, Geneva; available at: Pg 001-017 (who.int) (accessed on 21 October 2022). WHO (2013), Infectious Diseases in a Changing Climate; Infectious diseases in a changing climate (who.int) (accessed on 23 October 2022)

28 Lia, Patsavoudi (2020), Can the pandemic sound the alarm on climate change? Green peace; Can the pandemic sound the alarm on climate change? - Greenpeace International (accessed on 23 October 2022).

29 McMichael, A.J, et. al (2003), n. 27.

30 WHO (2020), COVID-19 and violence against women What the health sector/system can do; available at: WHO-SRH-20.04-eng.pdf; Harshitha Kasarla, “India’s Lockdown is Blind to the Woes of Its Women”, The Wire, 2 May 2020; India’s Lockdown Is Blind to the Woes of Its Women (thewire.in); UN Women (2020), Infographic: The Shadow Pandemic - Violence Against Women and Girls and COVID-19, 6 April 2020; Infographic: The Shadow Pandemic - Violence Against Women and Girls and COVID-19 | UN Women –Headquarters (accessed on 23 October 2022).

31 ICRC (2021), “Human security focus needed in conflict and climate and conflict-affected communities”; climate-related risks | ICRC; ICRC (2020), “Communities facing conflict, climate change and environmental degradation walk a tightrope of survival”; Communities facing conflict, climate change | ICRC (accessed on 23 October 2022); Camey, Itza' Castaneda et al., (2020), Gender-based violence and environment linkages: The violence of inequality, IUCN; available at: Gender-based violence and environment linkages: the violence of inequality (iucn.org) (accessed on 23 October 2022).

32 UNDRR (2022), n. 20.

33 UNEP (2009), From Conflict to Peace Building: The Role of Natural Resources and the Environment; available at: untitled (unep.ch) (accessed on 23 October 2022)

34 UN (2012), Toolkit and Guidance for Preventing and Managing Land and Natural Resources Conflict: Land and Conflict; available at: GN_Land and Conflict.pdf (un.org) (accessed on 23 October 2022).

35 H Patricia Hynes (2017), “War and Warming: Can We Save the Planet without Taking on the Pentagon?” Portside; War and Warming: Can We Save the Planet Without Taking on the Pentagon? | Portside (accessed on 23 October 2022)

36 True, Jacqui (2016), Working Paper Ending violence against women in Asia: International norm diffusion and global opportunity structures for policy change, UNRISD Working Paper, Geneva; available at: Ending violence against women in Asia: International norm diffusion and global opportunity structures for policy change (econstor.eu) (accessed on 23 October 2022)

37 OECD (2010), “Managing Climate Risks, Facing up to Losses and Damages: Losses and damages from climate change: A critical moment for action”; available at: https://www.oecd.org/environment/managing-climate-risks-facing-up-to-losses-and-damages-55ea1cc9-en.htm (last visited on 31 July 2022). Also see, Seth Landau, Ecoltdgroup ed. (2011), “Assessing the Economic Impact of Climate Change: National Case studies”, UNDP; available at: file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/Economic-Impact-of-Climate-Change.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2022).

38 UNDRR (2022), n. 20, pp.32-41.

39 Marc Jones (2022), “Climate change putting 4% of global GDP at risk, new study estimates”, 28 April 2022, Reuters; available at: Climate change putting 4% of global GDP at risk, new study estimates | Reuters (accessed on 27 October 2022)

40 IMF (2019), The Economics of Climate; available at: The Economics of Climate Change –IMF F&D | December 2019 (accessed on 4 November 2022).

41 Christopher Flavelle (2021), “Climate Change Could Cut World Economy by $23 Trillion in 2050, Insurance Giant Warns”, New York Times, 22 April 2021; available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/22/climate/climate-change-economy.html (accessed on 27 October 2022).

42 Bharat H Desai and Moumita Mandal (2022), Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in International Law: Making International Institutions Work, Singapore: Springer Nature.

43 UN Women (2016), The Economic Costs of Violence against Women; available at: The economic costs of violence against women | UN Women –Headquarters (accessed on 4 November 2022).

44 Bharat H Desai (2022), “Poverty as a Violation of Human Rights: Taking International Law Seriously”, SIS Blog Special, 21 October 2022; Blog Special: Poverty as a Violation Human Rights: Taking International Law Seriously (sisblogjnu.wixsite.com)

45 UN Women (2016), n.43

46 International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (2017), “Effective law and policy on gender equality and protection from sexual and gender-based violence in disasters”; available at: Gender SGBV Report_ Zimbabwe HR.pdf (redcross.eu) (accessed on 27 October 2022)

47 UNFPA (2009), “Climate Change Connections: Policy that Supports Gender Equality”; available at: climateconnections_2_policy_0.pdf (unfpa.org) (accessed on 27 October 2022)

48 UN (1979), Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women; available at: Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women New York, 18 December 1979 | OHCHR

49 UNHCR (1951), Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees; available at: UNHCR - Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees

50 UN (1966), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; available at: International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights | OHCHR

51 UN (1966), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; available at: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights | OHCHR.

52 UN (1948), Universal Declaration of Human Rights; available at: Universal Declaration of Human Rights | United Nations

53 UNSC (2000), Security Council Resolution 1325, 31 October 2000; available at: N0072018.pdf (un.org)

54 Bharat H Desai and Moumita Mandal (2021), “Role of Climate Change in Exacerbating Sexual and Gender-Based Violence against Women: A New Challenge for International Law”, Environmental Policy and Law 51 (2021) 137–157; available at: epl_2021_51-3_epl-51-3-epl210055_epl-51-epl210055.pdf (un.org) (accessed on 27 October 2022).

55 UN (1972), Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, 5-16 June 1972, Recommendation 70 at p.20; available at: NL730005.pdf (un.org) (accessed on 28 October 2022)

56 UNEP (1972), Stockholm Declaration; available at: ELGP1StockD.pdf (unep.org) (accessed on 4 November 2022).

57 For a detailed study on MEAs, see generally, Bharat H Desai (2010), Multilateral Environmental Agreements: Legal Status of the Secretariats (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010; paperback edition 2013); crio.pdf (cambridge.org)

58 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992); available at: UNITED NATIONS FRAMEWORK CONVENTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE (unfccc.int) (accessed on 4 November 2022)

59 UNFCCC (1997), Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/1997/L.7/Add.1 10 December 1997; available at: A: cpl07a01.wpd (unfccc.int) (accessed on 4 November 2022)

60 UNFCCC (2001), Improving the participation of women in the representation of Parties in bodies established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or the Kyoto Protocol; Decision 36/CP.7, FCCC/CP/2001/13/Add.4; Report of the Conference of the Parties on its Seventh Session, Marrakesh, 29 October-10 November 2001 Addendum Part Two: Action Taken by the Conference of the Parties; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2001/13/Add.4, 21 January 2002; available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/cop7/13a04.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022)

61 Women and Gender Constituency, About us; available at: About us | Women & Gender Constituency (womengenderclimate.org) (accessed on 4 November 2022)

62 Tzili Mor (2018), Towards A Gender responsive Implementation of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, UN Women, New York, p. 30; available at: Towards-a-gender-responsive-implementation-of-UN-Convention-to-Combat-Desertification-en.pdf (unwomen.org) (accessed on 28 October 2022)

63 UNFCCC (2010), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its sixteenth session, Cancun, 29 November - 10 December 2010; Addendum Part Two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its sixteenth session; Decision 1/CP.16 The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2010/7/Add.1, 15 March 2011; available at: Microsoft Word - cp7a1.doc (unfccc.int) (accessed 4 November 2022)

64 Ibid, para 7, p.3

65 Ibid, para 12, p. 4

66 Ibid, Para 3, p. 47

67 UNFCCC (2012), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its eighteenth session, Doha, 26 November-8 December 2012; Decision 23/CP.18 Promoting gender balance and improving the participation of women in UNFCCC negotiations and in the representation of Parties in bodies established pursuant to the Convention or the Kyoto Protocol; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2012/8/Add.3, 28 February 2013; available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2012/cop18/eng/08a03.pdf#page=47 (accessed on 28 October 2022)

68 Ibid, para 8, 10, p 48.

69 UNFCCC (2014), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twentieth session, Lima, 1-14 December 2014; Decision 18/CP.20 Lima work programme on gender, pp.35-36; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2014/10/Add.3, 2 February 2015; available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2014/cop20/eng/10a03.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022)

70 UNFCCC (2015), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-first session, Paris, 30 November - 13 December 2015; Decision 1/CP.21 Adoption of the Paris Agreement, pp.2-36; Doc. UNFCCC/ CP/2015/10/Add.1, 29 Jan 2016; available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/10a01.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022)

71 Ibid, p. 2, Annex Paris Agreement, p.21

72 Ibid, para 102, p.15

73 Ibid, p. 26

74 UNFCCC (2016), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-second session, Marrakech, 7-18 November 2016; Decision 21/CP.22 Gender and climate change, pp.17-20; Doc. FCCC/CP/2016/10/Add.2, 31 January 2017; available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2016/cop22/eng/10a02.pdf#page=17 (accessed on 28 October 2022)

75 Ibid.

76 UNFCCC (2017), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-third session, Bonn, 6-18 November 2017; Decision 3/CP.23 Establishment of a gender action plan, pp. 13-18; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2017/11/Add.1, 8 February 2018; available at: available at: 1801342 (unfccc.int) (accessed on 28 October 2022)

77 Ibid, para 1,2,3

78 UNFCCC (2018), Differentiated impacts of climate change and gender-responsive climate policy and action, and policies, plans and progress in enhancing gender balance in national delegations; Subsidiary Body for Implementation Forty-ninth session, Katowice, 2–8 December 2018; UN Doc. FCCC/SBI/2018/INF.15, 6 November 2018; available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/inf15.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022)

79 IUCN (2018), Advancing gender equality, women’s empowerment and indigenous rights from COP24 to COP25 through the Paris Rulebook, December 2018; available at: https://www.iucn.org/news/gender/201812/advancing-gender-equality-womens-empowerment-and-indigenous-rights-cop24-cop25-through-paris-rulebook (accessed on 28 June 2022).

80 UNFCCC (2020), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-fifth session, Madrid, 2-15 December 2019; Decision 3/CP.25: The Enhanced Lima Work Program on Gender; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2019/13/Add.1, 16 March 2020, pp.6-15; available at: FCCC/CP/2019/13/Add.1 (unfccc.int) (accessed on 28 October 2022)

81 Ibid, para, 6

82 UNFCCC (2021), Adopted agenda; Conference of the Parties Twenty-sixth session Glasgow, 31 October–12 November 2021; available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/COP26_adopted_agenda_0.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

83 UNFCCC (2021), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty-sixth session, Glasgow, 31 October-13 November 2021; Decision 20/CP.26 Gender and climate change, Doc. FCCC/CP/2021/12/Add.2, 8 March 2021, pp.35-37; available at: Report of the Conference of the Parties on its twenty- sixth session, held in Glasgow from 31 October to 13 November 2021. Addendum. Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its twenty-sixth session | UNFCCC (accessed on 28 October 2022).

84 UNFCCC (2022), Twenty-seventh Conference of the Parties, Sharm el-Sheikh, 6-18 November 2022; Sharm el-Sheikh Climate Change Conference - November 2022 | UNFCCC (accessed on 28 October 2022).

85 UNCCD (1994), United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification in those Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, particularly in Africa, Paris, 14 October 1994; UN Doc. Ch XXVII 10, VOL-2, Chapter XXVII. Environment; available at: Ch_XXVII_10p.pdf (un.org) (accessed on 28 October 2022).

86 Ibid, Article 10 and 19.

87 UNCCD (2019), The Ankara Initiative: Leveraging Lessons Learned From Turkey’s Experience With Sustainable Land Management; available at: 1208_Ankara_web.pdf (unccd.int); UNCCD (2015), Ankara initiative; available at: https://www.unccd.int/convention/conference-parties-cop/ankara-initiative; Decision 29/COP.12, Ankara initiative, UN Doc. ICCD/COP(12)/20/Add.1; available at: https://www.unccd.int/sites/default/files/inline-files/Decision%2029_COP.12.pdf; (accessed on 29 October 2022)

88 Tzili Mor, n.62.

89 UNCCD (2019), n. 87, p.9.

90 UNCCD (2017), Gender equality and women’s empowerment for the enhanced and effective implementation of the Convention; Decision 30/COP.13; UN Doc. ICCD/COP(13)/21/Add.1; cop13decision.pdf (unccd.int) (accessed on 29 October 2022)

91 Tzili Mor, n. 62, pp. 12, 13.

92 Bharat H. Desai (2004), Institutionalizing International Environmental Law. Ardsley, New York: Transnational Publishers, chapter 4, p.117.

93 UN (1992), The Convention on Biological Diversity; available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2022)

94 UNEP (2017), Why gender is important for biodiversity conservation; available at: Why gender is important for biodiversity conservation (unep.org) (accessed on 4 November 2022)

95 CBD (2010), Gender mainstreaming (X/19); Decisions Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity at its Tenth Meeting, Nagoya, Japan, 18-29 October 2010; UN Doc. UNEP/CBD/COP/10/27, p. 179; available at: cop-10-dec-en.pdf (cbd.int) (accessed on 29 October 2022)

96 Human Rights Council (2021), Human rights and climate change, Resolution 47/24; UN Doc. A/HRC/RES/47/24, 26 July 2021; available at: G2119969.pdf (un.org) (accessed on 29 October 2022).

97 OHCHR (2022), Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights; available at: OHCHR | Special Rapporteur on climate change (accessed on 29 October 2022).

98 UN (1992), Rio Declaration on Environment and Development; Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 3-14 June 1992; UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26 (Vol. I), 12 August 1992; available at: A/CONF.151/26/Vol.I: Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (un.org) (accessed on 29 October 2022)

99 UN (2002), Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, 26 August-4 September 2000; UN Doc. 199/20; available at: World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg 2002 | United Nations (accessed on 29 October 2022).

100 UN (1992), Agenda 21, the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3-14 June 1992; available at: Agenda21.doc (un.org) (accessed on 3 November 2022)

101 UN (1992), Ibid, chapter (objective) 24.2 h.

102 UN (1992), Ibid, chapter 24.11

103 UN (1992), Ibid, chapter 24.6.

104 UN (2012), Review of implementation of Agenda 21 and the Rio Principles, Study prepared by the Stakeholder Forum for a Sustainable Future, January 2012, p. 48; available at: 641Synthesis_report_Web.pdf (un.org) (accessed on 3 October 2022)

105 UN (2005), Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters, paragraph 13 (d), p.10; available at: g0561029.doc (un.org) (accessed on 3 November 2022).

106 UN (2015), The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030; available at: Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 - 2030 (preventionweb.net) (accessed on 3 November 2022).

107 UN (2022), Report of the Secretary-General; UN Doc. E/CN.6/2022/3, 4 January 2022; available at: Achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls in the context of climate change, environmental and disaster risk reduction policies and programmes: (un.org) (accessed on 3 November 2022).

108 Ibid.

109 WEDO (2007), Report of High-level Roundtable How a Changing Climate Impacts Women, Permanent Mission of Germany to the United Nations, 21 September 2007; available at: Microsoft Word - Roundtable Final Report 6 Nov.doc (wedo.org) (accessed on 28 October 2022).

110 Ibid. pp.1-2

111 UNFCCC (2007), Provisional agenda and annotations Note by the Executive Secretary, Conference of the Parties Thirteenth session Bali, 3–14 December 2007; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2007/1, 7 September 2007; available at: Microsoft Word - cp1.doc (unfccc.int) (accessed on 3 November 2022)

112 UNFCCC (2007), Report of the Conference of the Parties on its thirteenth session, Bali, 3-15 December 2007; UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2007/6, 14 March 2008, paragraph 128; available at: Microsoft Word - cp6.doc (unfccc.int) (accessed on 28 October 2022)

113 Desai and Mandal, n.42 and Desai and Mandal, n.54.

114 Ibid.

115 UNFCCC (2020), Strengthened 5-year Action Plan on Gender Adopted at COP25, Madrid, 28 January 2020; available at: Strengthened 5-year Action Plan on Gender Adopted at COP25 | UNFCCC (accessed on 28 October 2022).