E-spect@tor for performing arts

Abstract

In the framework of DiMPAH (Digital Methods Platform for Arts and Humanities), an online course “e-spect@tor for performing arts” has been designed to make available digital methods created by the Digital Humanities project “The spectator’s school” to the scientific community and the students. The main aim of this course is to train learners to analyse performative works from video recordings. Those analysis are notably achieved with the use of the digital tool e-spect@tor developed by “The spectator’s school” to annotate live art videos with different features that allows to study performative aspects. While “Unit I” is focused on introducing the “Performing arts”, “Unit II” is dedicated to the analysis of case studies proposed to serve as models. The course can be used on e-learning and in a hybrid teaching format through a possible course structure and aims as described and tested with students. Furthermore, by using digital technology, this course can be at the forefront of new stories for Europe in terms of pedagogy as it trains to enable new media literacy and to analyse any activity that is staged such as political discourses, public meetings, or interviews.

e-spect@tor for Performing Arts is an online course dedicated to learning how to analyse Performing Arts with video resources by using digital technology. This pedagogical product is the result of research carried out within the project “L’École du Spectateur (The spectator’s school)”. It is a digital humanities programme which is developing the digital tool used in this course to annotate videos of live performances: “e-spect@tor”.

In this paper, we describe the research project upon which this course is based, research that is exploring digitalisation of the performing arts. We then look at the way in which case studies are considered in the course, both to illustrate the course subject and to train the students. Finally, we underline how this course can be at the forefront of new stories for Europe in terms of pedagogy, i.e. it can be used to study performative works but also any activity that is staged such as political discourses, public meetings or interviews for example.

1.Performative studies, performative turn

1.1“L’École du Spectateur”: The research project

The e-spect@tor for Performing Arts course stems from the research project “L’Ecole du Spectateur” which is founded on the observation that the current digital transformation is leading to record audiovisual performances, and in recent years, this number has been growing constantly. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, some of these records have been made available to the public by the institutions or entities that produced the performance. While a performance is first and foremost a unique, collective and ephemeral experience, the video allows the spectator to relive the performance, also out of the supposed dedicated space. The question that arises then is how the use of the video in research, and training, is introducing a new paradigm in theatre studies?

Our perspective does not aim to discuss the differences between a performance on stage, in front of an audience, and a distanced performance through a video, our question concerns the way the video, now more accessible than before the pandemic, is contributing to the renewal of research and training in theatre studies? We investigate how the video facilitates the detection of certain performative aspects in works that have been performed, how it enables the study of performative elements that are difficult to attest and analyse from the memory of the spectators’ experience which is sometimes misleading, or from documents such as photos, writings, or sound recordings.

All these traces or “impressions” do not account for the visual experience, at least not in such a convincing way as the video with its temporal unfolding. It must be recalled that the theatre,

With the emergence of many platforms for viewing videos of theatrical or performative works, especially since the pandemic, intended for the general public11 or the teaching community,22 we now have the relevant video resources needed to analyse theatrical live performance, however, we are currently still lacking the relevant digital tools to work with such resources. We are also noting that the performing arts are gradually undergoing what Davis (2008) calls a “performative turn”, i.e. an epistemological shift from theatre studies to performance studies.

The theoretical turn began in the 1960s in the UK and US, more precisely, in the English-speaking world, with Richard Schechner33 and Victor Turner44 works. With the emergence of the performance as a practice of artistic expression in the 1950s and the acceleration of the digitalisation of the field from the 2000s onwards, they have seen performance studies develop and theatre studies embrace some of the concepts of this field. The performance studies consider that the theatre, as well as dance and music, is a performative artistic activity. Consequently, they favour a phenomenological approach to performances that integrates the analysis of the audience response or appreciation.

In the last twenty years, this performative turn has accelerated, coupled with the digital turn. The digital has appeared as a means to have access to information that was previously inaccessible, and to use it together with the public, to give rise to new and innovative studies of the works. In this context, a new concept has emerged, “theatrology”, a field that combines several methodological approaches to the study of theatre (Pavis, 2002, p. 381), including from now on, using digital tools.

The research project “L’Ecole du Spectateur” fits in the “theatrology” field and has two main objectives, the first one is to encourage the young public to go to the theatre by providing the keys to understanding a sometimes complex art. The other objective is to recreate, in the virtual environment, the Post-Show Discussion about the performance. It has been inspired by the format and approach of the Argentinian “Escuela de Espectadores” created in 2001 by the theorist and critic in Performing Arts, Prof. Jorge Dubatti (Universidad de Buenos Aires). J. Dubatti has developed a framework for analysing the performance with the public focusing on three components that define what makes the work performative: the “convivio” (the coming together of spectators and performers), the “poiesis” (the artistic event), and the “expectación” (the spectators’ appreciation) (Dubatti, 2012). However, using his framework is not easy because there is no roadmap that can be exploited by others; Dubatti’s method does not incorporate the use of mobile devices that would allow the spectators to describe their experience during the live show. There are models and analytical grids in theatrical theory that have already been developed and proposed by theorists such as Ubersfeld, Helbo, and Pavis (Pavis, 2012, pp. 39–44), but none of them have considered the analysis of the performative dimension of the spectacle in line with the theoretical shift previously mentioned, nor, obviously, the performative turn currently underway.

The “Spectator’s school” project aims at filling these gaps through a virtual school that studies videos of performative works as well as developing the needed digital tool for it. The e-spect@tor course presents these scientific outputs in a pedagogical context: the performative turn history is part of the theoretical course, while the digital tool developed is dedicated to analysing videos of performing arts. The tool enables the annotation of the videos with words, sentences, emoticons but also with a controlled vocabulary that is part of pioneering ontology for analysing performing arts.

1.2e-spect@tor annotation tool

The e-spect@tor video annotation tool for performances, is the result of enhancing an existing application: Celluloid55 which was launched in 2015 by Laurent Tessier, a researcher in sociology, and Michaël Bourgatte, a researcher in information and communication sciences, both from the Institut Catholique de Paris. Celluloid was initially designed to read and annotate videos extracted from YouTube; the annotation work can be done individually or collectively (as part of a teaching activity) and the videos and associated comments shared.

These initial functionalities have been adapted to analyse performance art videos: indeed, the fact of being able to annotate a video while it is viewed, according to a timeline, makes it possible to reproduce the duration of a live performance through technology, and therefore its event dimension. This allows spectators to record their impressions and reflections, exactly when these come to mind, as is the case when they attend a performative work. The tool also had multi-hand annotation functionality included which is completely relevant for this project because, as a “convivio” (Dubatti, 2012), live performance is experienced and appreciated collectively.

In addition, the celluloid tool was stored in the servers of the infrastructure Huma-Num to ensure its robustness. The idea was therefore to improve an existing code by adding functionality that was missing to address the specific needs of the live performance: four features were then added.

a) A first feature developed was the possibility of using videos from platforms other than YouTube and to upload them from their own computer as some videos are unavailable online for reasons of image rights or because the author of the work refuses to broadcast the recording of his work but might be willing to share it with research teams or teachers.

b) A second feature was an addition to the classic viewing mode (called “analysis mode”): we called it the “performance” viewing mode. When activated, this implies the user cannot have access to the “pause”, “stop”, “forward” or “backward” functions. This constraint recreates, by means of technology, one of the conditions for the run of live performances: the fact it generally takes place without interruption. Through the “performance” mode, the user artificially puts himself in the shoes of a spectator attending a live show and can feel, with a certain spontaneity, some of the emotions of the performance, such as joy, laughter, sorrow, or other sensations.

c) A third feature was the ability to export the annotations in an XML file format and/or in a CSV spreadsheet: this allows the users to use the data outside of the tool. The export makes it easier to manipulate the data, especially if the annotation has been done by several people.

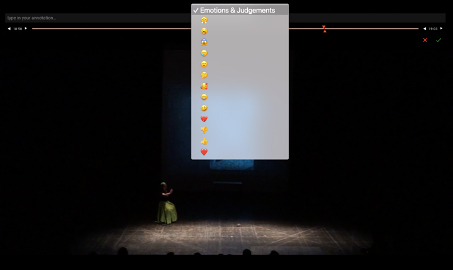

d) A fourth functionality was the integration of an ontology. Specialised in performing arts, this ontology organises and structures the application information. A suggested set of emoticons connected to the ontology enables the users to state their basic emotions and judgements about the show. The emoticons can only be used when the “performance mode” is activated. A set of selected keywords, also linked to the ontology, is also suggested to the users. These are available when the user chooses the analysis mode.

Having presented the research framework, we will now present two case studies below to illustrate the course.

2.User case studies

2.1Karen Veloso’s “Ramona au Grill” and Scheherazade Zambrano Orozco’s “Chutes”

Figure 1.

View of the application used in performance mode: the emoticon set for declaring emotions and simple judgements and the free annotation.

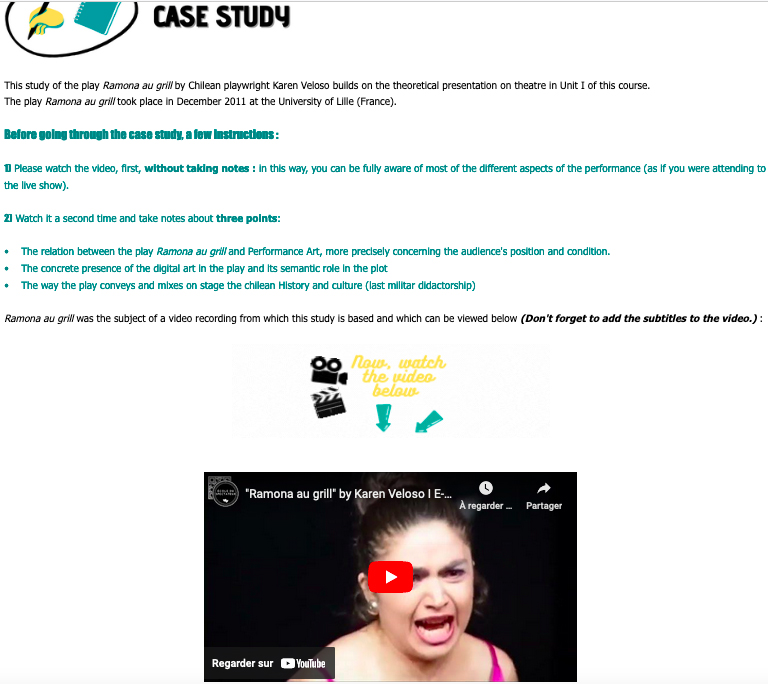

Figure 2.

General presentation of the study case based on the theatrical performance “Ramona au grill” with instructions for analysis.

Figure 3.

Hybrid work during the course test: both from the online course and in direct exchange with students.

While “Unit I” is focused on introducing the “Performing arts” and the different artistic performative disciplines or activities considered such as, as theatre, dance, performance art and fashion shows, “Unit II” is dedicated to the analysis of examples, they are case studies proposed to serve as models for the students. “Ramona au Grill” (“Unit II 2.1 The theatrical show: a performed poetics”), the play of the Chilean playwright, director and actress Karen Veloso was created in 2011 while the dance performance, “Chutes” (“Unit II 2.4 Performance Art: liminal, strange and body experience”), by the choreographer and dancer, Scheherazade Zambrano Orozco was created in 2014. Both are very recent performative creations and were chosen as they are representative of the Performative Turn previously described. These plays have not been recorded for a public viewing but to create archives of the works. It must be recalled here that in most cases, the plays’ recordings do not have the goal of enhancing the artist’s works or professional in question, or even to serve as creative, scientific or educational material, but to create a personal archive. This is the case for the two plays presented as case studies in the course which were used to orient learners to analyse performative elements.

The theatrical performance Ramona at the Grill is the story of a housewife, Ramona, who is recording a recipe for television, that of the Chilean “cazuela”, a typical dish of the country. At each step of the recipe preparation, memories of the past resurface, those of the Pinochet dictatorship and the military repression against civilians. The spectator understands that the memories of that time are still haunting her, that the sounds and images of daily life emerge her in a difficult past. Past and present are superimposed in the play, they collide to illustrate how long the road towards the repair of the past and the healing of the wounds is.

The dance performance “Chutes” aims to tell the history of today’s Mexico, illustrating its falls, the chaos due to the confluence with the different problems its geographical situation provokes “so close to the USA and so far from God” as Porfirio Díaz would have said while he was Mexican President (in 1876–1880 and in 1884–1911). The performance illustrates the collapsing bodies suffering the earthquake and metaphorically the economic crisis, migrations, corruptions, and, of course, the consequences of drug trafficking.

For the learners, these case studies illustrate how some unsolved 20th historical problems are currently disrupting some Latin-American societies, with regards the theory (Unit I), they illustrate theatre’s commitment to shine a light on society’s issues and make greater demands on learners’ engagement.

2.2Case studies’ organisation

Each case study starts with instructions that engage the learners to read in an active way. The link with the theoretical part of Unit I is always provided at the beginning of the page, so that the learner can make the connection immediately and if necessary, re-read, the theoretical part on theatre, dance, fashion shows or performance art. Then, the learners are asked to watch the video: the video is embedded directly in the instructions page to avoid having to copy a link and to leave the course.

The learners have to first watch the video in the “Performance mode”, in one go, without stopping it. As stated previously, this instruction is linked to the theoretical postulate that, even if the video cannot obviously recreate the conditions of a live performance, both the ephemeral nature of the performance and the co-presence of the actors and the public in the same room, the fact the learners are watching the video in one go, without stopping it, without taking notes, tries to recreate, virtually, some of the conditions of the performative works in real conditions. As a matter of fact, in a theatre hall, the audience cannot stop the performance in progress and rarely take notes so as not to disturb other spectators. Moreover, the spectator’s appreciation is not made from a final version but during the temporal process of its run: the awareness and the comprehension of a performative work is thus characterised by its historicity. This historicity is inherent and essential to analyse the work when it takes into account the audience response. This is a common method when teaching the analysis of live works in Human Sciences: the teachers usually ask the students to take time to first watch or to attend the performance, before beginning the analysis.

Once this step is done, the second instruction given to the learners is to watch the video a second time (or more) with a “pencil in hand”. Of course, they can take notes, but we have chosen to ask them to focus their attention on three phenomena that highlight the performative works chosen for learning. For example, for the case study based on the theatrical performance, Ramona au Grill, they were asked to focus their attention and take notes according to three points: 1) The relation between the play Ramona au grill and Performance Art, more precisely concerning the audience’s position and condition, 2) The concrete presence of digital art in the play and its semantic role in the plot 3) The way the play conveys and mixes the Chilean History and culture (last military dictatorship) on stage.

For the case study based on the Chutes performance, they were asked to focus on 1) The location of the performance (where did it take place? what is the performance space?) and its main impact on you 2) The commitment of the performer’s body during the live work and what it conveys for her and for the audience 3) The unusual vision of the world the performance presents to the spectators.

Each page of each case study is devoted to an aspect of the live show’s analysis, and each one repeats the initial instructions. The learners are asked to reread the notes taken and to compare them with the analysis that follows. By using the course in hybrid mode, the learners will be able to share the elements noted with what other students have noted (and that may not be included in the analysis suggested by the course) and the teacher will then be able to discuss with them whether the elements identified by them are relevant or not. In self-study, the learners will not be able to go beyond and compare with others what they have indicated on their paper or computer if applicable.

It should be pointed out that on each page, the video is embedded so that the learners do not have to open an additional tab or return to the case study introduction page: they can therefore access the analysis of each issue raised and watch the video at the same time.

Since the videos were taken from the YouTube platform, we took advantage of one of its features – the possibility of integrating bookmarks – to illustrate our point regarding a precise moment of the video. In addition, each page includes one or two screenshots of the videos to illustrate the most characteristic elements of the performative dimension of the analysed work: for example, the choice of an unconventional place for the dance performance or the use of the body in the performance in both cases.

2.3Use case of the course “e-spectator for performing Arts”

In December 2022, at La Rochelle Université, “e-spect@tor for performing arts” course was used in a real course, in hybrid format. Within a course on “Hispano-American cultural environment”, we have combined our in person teaching with the DiMPAH course and asked the students to write an essay on Karen Veloso’s theatrical performance entitled Superposition (2019) as a final task.

During the first class (each class lasts one hour and a half), we presented first the course structure and aims, then we asked the students to read the theoretical part of the online course concerning the general overview (“1.1 General Overview”) on Performative Arts. They were asked to focus on answering the following points: 1) what are Performing arts? 2) what is the relationship between the Performing Arts and, in France, “le spectacle vivant”? 3) what is the Argentinean theoretical approach for the analysis of Performing Arts? 4) why do we talk about obsolescence? 5) what is the “Performative Turn”? They were given about 20 minutes to do this preliminary work and then their feedback was pooled to check what they had understood. The last part of the session was devoted to viewing the play within the e-spect@tor platform by using the performance mode. Thus, the students were only allowed to use the set of emoticons for declaring their emotions, experienced and basic opinions and also the free annotation. After this first viewing, we spent ten minutes listening to their first impressions and opinions on this play in order to roughly define what had been understood and felt.

We started the second session by asking the students to log back onto the on-line platform and to readthe part on the theatrical performances for 20 minutes (“1.2 Theatre”) considering the following aspects: 1) what is theatre? 2) why is theatre also mimetic in addition to being performative? 3) in theatrical work, who communicates with whom? 4) In a theatrical performance, what is the space like? As we did during the first class, we first took stock of what they had understood: then we together defined the essential concepts characterising theatrical performances. At this point, they were asked to log back into the e-spect@tor platform and to watch the video for a second time in “Analysis mode”: they were able to use the free annotation and also the ontology (the set of emoticons and the set of performing arts concepts) and to stop, forward and rewind the video as they wished.

The third session was organised with a different scenario: to help the students in their future analysis of Superposition, they were invited to watch Karen Veloso’s theatrical performance, Ramona au grill (2011) again and then to read the course section “2.1, for 20 minutes: The theatrical show: a performed poetics” dedicated to its analysis. They were asked to answer the following questions: 1) to what extent is Ramona au grill a “canonical” performative play and to what extent is it not a classical play? 2) what kind of spectator is the audience also embodied in the play? For what purpose? 3) What relationship is established between food and Chilean history? After that, they have been invited to share, pool, check and organise their answers orally for them to develop a clear and structured analysis of the main characteristics of this theatrical performance.

We started the fourth session asking the students to watch Superposition for a third time through e-spect@tor, in “Performance mode”, and to annotate the video again in relation to three aspects directly connected with the specifications we defined for Ramona au grill: 1) The hybrid form of the live show Superposition 2) The role of the spectator 3) The leitmotiv of the Chilean disappeared.

Then, as with previous sessions, we put together their ideas and comments and defined the main lines of the analysis of the theatrical performance, Superposition, as well as giving them the opportunity to develop their own ideas and interpretations. At the end of this session, which was the last one, we showed them how to extract their annotations in CSV or XML files, so that they could retrieve and easily reuse the notes taken during the class. They were asked to write a commentary on the theatrical performance, Superposition, to deliver two weeks later.

3.A course for future stories for Europe

The e-spect@tor for performing arts course is a model for digitally assisted video analysis for independent online study or in hybrid class. In terms of pedagogy, it enables the analysis of multiple phenomena of the living works and of their performative nature and contributes to the emergence of new pedagogical methodologies for the study of works and performative activities.

When it comes to working on performative works, as a first step the teachers usually consider taking their students to the theatre, particularly when they can take advantage of a work performed in the city, close to them. As seen previously, it is indeed a key step for an initial appreciation of a performative work in its real conditions. But actually, most of the time, the teachers do not have the opportunity to take the students to the theatre: as a consequence, thay have been used to basing their teaching on the theatrical text and/or a VHS video, if it luckily exists. The manipulation of a video by VHS training was generally only carried out by the teachers themselves, because there was only one device available in the classroom. Now, with the abundance of video resources of live performances and their direct accessibility for users, the learners are able to use, handle and discover the relevant elements of analysis. The e-spect@tor for performing arts course is a part of the actual pedagogical context, it considers the teachers to use more and more easily in their course (Archat Tatah, Bourgatte, 2014).

Furthermore, by making the student operate the video, either in a relatively simple way (by simply viewing and adjusting the timeline) and/or using the e-spect@tor digital tool with its advanced features previously described, the course also engages the learners in an awareness and understanding of the interactive dimension of the performative work. A dimension that they do not necessarily notice in its totality when they actually watch a live performance as spectators, sitting in the stands and the darkness of a performance hall. Indeed, the learners generally feel passive about what is happening on stage and this feeling is strengthened by the activation of the principle of “denial” defined by Anne Ubersfeld: the spectator has the impression that he is witnessing a dream when he sees a performative work (Ubersfeld, 1996, pp. 37–38). Nevertheless, his whole body reacts to what he sees and perceives, and his mind constructs its own reception of the work: contrary to what he thinks, the spectator is really active during a live performance. By allowing him to dwell on live performance videos and to define the effects it has on him, the e-spectator for performing arts course thus contributes to the construction of the participatory figure of the spectator, the “spect-actor”. Moreover, if the e-spect@tor for Performing Arts course can be used by learners to better understand the interactions between the Performing Arts and the spectators, and especially to identify their role in the construction of the meaning of a work of this type, it can also allow a better understanding of the way in which the work or the performative activity plays with him, or even manipulates him. An analysis and interpretation of how these artistic or cultural productions can use our emotions (in terms of quantity or categories) to make us feel a situation, to move us to a state or even to make us adhere to a specific cause, to a political idea, is quite interesting in terms of the construction of critical thinking in the learner. The development of these skills and values to enable new media literacy is supported by the European Union in the education and training of young European citizens.66

The methodology to analyse a performative work offered by this course thus plays an essential role in the learner’s training to keep a critical eye on any performative production aiming at producing an immediate and impacting effect on the public: a political speech, activism or simply a journalistic reportage. In today’s world, where the video image has replaced the written word as the preferred medium not only for the dissemination of information but also for communication between individuals, the promotion of products and political propaganda, it is an undeniable asset to have digital methods and tools at one’s disposal that allow one, and mostly young people, to identify elements of performative intents.

4.Concluding remarks

E-spect@tor for Performing Arts is an innovative course based on a pioneering scientific project in Digital Humanities for the digitalisation of performing arts research. Based on the hypothesis that the digital video archive is today the best trace of what was the performance essentially ephemeral and not reproducible, this course therefore aims to approach performative Arts analysis by making a privileged use of this abundant quantity of media available today with the digital turn.

This course thus shows how to analyse video archives of a live performance from several performance case studies, in the second part of the course, as examples or models of analysis. However, the learners are asked to participate in the discovery of these case studies so that they can develop the knowledge acquired on different disciplines or performative activities and position themselves as true spectators. In the classroom, the course can also be used in hybrid mode by teachers: as we have seen in the test example we carried out, it is possible to build on the existing online course, in its entirety or part of it, using the e-spect@tor tool as well, and to encourage direct ideas exchanges with the students.

Finally, the e-spect@tor for performing arts course based on the digital analysis of video resources of live performances is giving birth to a series of new narratives in Europe: first in the way in which it transforms the didactics of the analysis of the performative arts for the learners by making it the participatory role that they play in the construction of the meaning more convincing and more palpable and secondly, the way in which it allows the learners to exercise a critical look at the video content that invades their daily life and that is not insignificant in terms of impact on the viewers.

Notes

1 Drama online: https://www.dramaonlinelibrary.com/, last visit 2023-03-05; CyranoTV: https://www. cyranotv.com/, last 2023-03-05; Teatrix: https://www.teatrix.com/, last visit 2023-03-05.

2 CyranoTV has a version dedicated to teachers, cyrano.education: https://www.cyrano.education/home, last visit 2023-03-05).

3 Richard Schechner is a director and theatre theorist. He is also a university professor at the Tisch School of the Arts (New York University) and editor of the largest American theatre magazine, The Drama Review. Considered one of the founders of performance studies, he is the author of several texts and books on the discipline: Performed Imaginaries (2015); Performance Studies (2002); The Future of Ritual (1993); Performance Theory (1988); Between Theater and Anthropology 1985; Environmental Theater (1973); Dionysus in 69 (1970), among others.

4 Victor Turner (1920–1983) is a British anthropologist whose work focuses on the study of rituals, rites of passage and dramaturgy. His best-known works include The Anthropology of Performance (1986); Liminality, Kabbalah, and the Media (1985); and From Ritual to Theatre. The Human Seriousness of Play (1982); Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors. Symbolic Action (1974).

5 https://celluloid.hypotheses.org/, last visit 2023-02-01.

6 https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/media-literacy, last visit 2023-02-01.

References

[1] | Bourgatte, M. ((2014) ). Vers des formes instrumentées d’enseignement et d’apprentissage: le cas de l’analyse de contenus audiovisuels. Eduquer |

[2] | Bardiot, C. ((2021) a). Arts de la scène et humanités numériques. Des traces aux données. Londres: ISTE Éditions. |

[3] | Bardiot, C. ((2021) b). “Étudier le théâtre aujourd’hui: les enjeux des traces numériques des arts de la scène”. Communication présentée aux Lundis numériques de l’INHA, Paris, 22 mars. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8J5ESw18P-I. |

[4] | Bourgatte, L., & Tessier, L. ((2020) ). “Annoter des vidéos avec PeerTube: une nouvelle étape pour Celluloid”. Celluloid.hypotheses.org (blog). https://celluloid.hypotheses.org/date/2020/05. |

[5] | Chantraine-Braillon, C. ((2022) ). “L’École du spectateur: informatiser la recherche en arts de la scène”, Humanités numériques, 5. http://journals.openedition.org/revuehn/2849; doi: 10.4000/revuehn.2849. |

[6] | Chantraine-Braillon, C., & Idmhand, I. ((2017) ). “Arts performatifs et processus de créations à l’ère numérique. Enjeux techniques et théoriques”. Revue d’historiographie du théâtre 4. http://sht.asso.fr/arts-performatifs-et-processus-de-creations-a-lere-numerique-enjeux-techniques-et-theoriques/. |

[7] | Chazalon, E. ((2019) a). Women and Feminism(s) in Performance / Femmes et feminisms en representation(s), Revue Française d’Etudes Américaines, n |

[8] | Chazalon, E. ((2019) b). They Have it Good, or Do They? Women’s Agency in Contemporary Visual and Material Cultures, Paris, Michel Houdiard, 2019. |

[9] | Davis, T. ((2008) ). “Introduction: the Pirouette, Detour, Revolution, Deflection, Deviation, Tack, and Yaw of the Performative Turn”. Dans The Cambridge Companion of Performance Studies, édité par Tracy Davis, 1-8. Cambridge et New York: Cambridge University Press. |

[10] | Dubatti, J. ((2012) ). Introducción a los estudios teatrales. Propedéutica. Buenos Aires: Atuel. |

[11] | Pavis, P. ((2002) ). Dictionnaire du théâtre. Paris: Armand Colin. |

[12] | Pavis, P. ((2012) ). L’ Analyse des spectacles. Théâtre, mime, danse, danse-théâtre, cinéma. Paris: Armand Colin. doi: 10.3917/arco.pavis.2016.01. |

[13] | Roche, C. ((2005) ). Terminologie et ontologie. Langages, 157: , 48-62. doi: 10.3406/lgge.2005.974. |

[14] | Schechner, R. ((1988) ). Performance Theory. Londres et New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203361887 doi: 10.4324/9780203359150. |

[15] | Schechner, R. ((2002) ). Performance Studies. Londres et New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315269399. |

[16] | Turner, V. ((1982) ). From Ritual to Theatre. The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications. |

[17] | Ubersfeld, A. ((1996) ). Lire le théâtre. L’École du spectateur. Paris: Belin. |