An open educational resource for doing netnography in the digital arts and humanities

Abstract

As a part of the DiMPAH-project, the authors have developed an open educational resource (OER) on netnography. In this paper, the OER is presented and critically discussed as the broader problem identified during course-development is made explicit and explored through two research questions: 1) How can an OER be designed that positions netnography as a viable methodology for the digital humanities? 2) How can an OER be designed that theoretically and methodologically combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches for doing netnography?

An up-to-date theoretical overview of netnography as a methodology for studying social experiences online is provided. Methodological considerations are presented, aimed for sensitizing students to nuances of active (participatory) and passive (non-participatory) netnography through two analytical concepts. The OER is presented through three case studies and a learning scenario offering flexible and authentic technology-integrated learning. Netnography is found to contribute to the digital humanities, overall characterized by method-driven and quantitative approaches, with reflexivity and a potential for critical research and pedagogy. The two analytical concepts community-based netnography and consociality-based netnography allow for a nuanced methodological understanding of how and when qualitative and quantitative approaches should be employed, and how they may complement each other.

1.Introduction22

Today, it is almost a truism to state that digitalization affects all aspects of human life. Digital technologies and digitally mediated communication are pervasive features when we socialize, seek, and share information about politics or hobbies, work, go to school or university etc. Netnography – ethnographic internet research – is a field of research and a methodology for the qualitative study of digitally mediated interactions using a specific set of methods (Kozinets, 2010, 2015, 2020). The name netnography is “a portmanteau combining network, Internet, and ethnography” (Kozinets, 2020, p. 6) and was coined by market researcher Robert V. Kozinets in the 1990s. Essentially, netnography is based on two premises: first, that nearly all aspects of our social interactions are to some extent digital nowadays, and second, that digitally mediated interactions should be studied with methods suitable for researching digital interactions. Netnography is a methodology for studying social experiences online, or in other words, “online networks of social interaction and experience” (Kozinets, 2015, p. 100).

Since the 1990s, netnographic approaches have been employed to create new knowledge about digital culture and digital society. Netnographic research spans a spectrum of disciplines and empirical settings, but a general aim is knowledge production that recognizes online social experiences. For example, netnographic approaches are used to investigate the potential for social media brand communities to develop a sense of both community and place amongst sports fans (Fenton et al., 2021), and to study information literacy, affordances, and norms of learning in a digital community at a pre-school teacher education (Hanell, 2020). Furthermore, netnography is used to study interactions in a digital community of lesbian mothers coping with postpartum depression (Alang & Fomotar, 2015). One defining feature of these example studies is a focus on digital communities, a concept, and a point of departure for netnographic research, we problematize and discuss in this paper.

For several years, we have taught Netnography and Social Network Analysis on a Digital Humanities Master’s program method course. While talking about netnography as a methodology during the most recent iteration of the course, several students were intrigued to hear about qualitative approaches in the context of digital humanities as the students during the first two courses of the master’s program had only encountered quantitative procedures. This anecdote illustrates issues that we have encountered and reflected on as teachers and researchers interested in advancing netnography as a methodology that combines qualitative and quantitative procedures and arguing for how the netnographic methodology can interact with, and contribute to, practices and research within the digital humanities.

As a part of the DiMPAH-project, the authors have developed an open educational resource (OER) on netnography. The OER introduces the ethnographic perspective that underpins netnography, key concepts such as digital communities and netnographic fieldwork, approaches for producing and analyzing netnographic material, and research ethics and legal aspects of importance for doing research in digital settings. Discussing methodology, methods, and digital tools highlights both potential and challenges for making netnography a viable methodology for the digital arts and humanities. Designing the OER, two main issues have been identified as crucial for the successful development of a pedagogical and useful educational resource as part of the DiMPAH-project. Both issues are interrelated in a broader problematic concerning the place of netnography (as a qualitative approach) within the context of the digital arts and humanities (often concerned with big data and quantitative procedures) but still fruitful to discuss separately (for a discussion on various method combinations for digital media focusing big data, see Leckner & Severson, 2019).

The first issue concerns how netnography as a methodology rooted in a social scientific and humanistic research tradition can be understood as a part of the digital arts and humanities. Carlsson and Hanell (2020) argue that netnography contributes to the broader digital humanities research field, often focused on research methods and inquiries connected to big data, quantitative procedures, and visualizations. In this context, netnography contributes with a qualitative perspective on the digital, allowing for inquiries into how culture is mediated and enacted through digital interactions. Given the theoretical and reflexive stance of netnography, something that we will discuss in detail below, the methodology can serve as a bridge between theoretically mature traditional humanistic research and contemporary digital methods. For example, netnography can provide valuable insights concerning reflexivity and the situated nature of human (research) practices that can enrich more method-driven approaches associated with the digital humanities (cf. Kozinets, 2020).

The second issue concerns how both quantitative and qualitative approaches for doing netnography can be combined theoretically and methodologically. Previous research (Costello, McDermott & Wallace, 2017) has brought attention to a tendency to employ “observational” or “non-participatory” approaches in netnographic research. This reflects a methodological strength of netnography in general but might also lead to netnographic accounts that lack nuanced understandings of certain phenomena (Kozinets, 2020).

In this paper, the OER on netnography is presented and critically discussed as the broader problem identified during the development of the course content is made explicit and explored through two research questions. The two research questions guiding this investigation are:

1. How can an OER be designed that positions netnography as a viable methodology for the digital arts and humanities?

2. How can an OER be designed that theoretically and methodologically combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches for doing netnography?

2.Theoretical overview

In essence, netnography can be understood as an extension of ethnography. The point of departure for netnographic research is consequently a cultural focus where significance is found in social patterns of digital interactions (Kozinets, 2020). Ethnographic research aims to understand and account for the perspectives of the participants. Rather than a method, ethnography is better understood as a perspective where the aim is to reach “a theoretical informed encounter with the other” (Shumar & Madison, 2013, p. 266). With an ethnographic perspective, the complexities, and the particularities of the social field of study are focused. Methodologically, netnography is based on the ethnographic notion of participant observation. Classic participant observation includes forming personal relations with the people being studied during an extended period. The aim is to achieve a sufficient degree of inclusion in the participants’ lives so that the researcher may understand a certain social field from the participants’ perspectives (Davies, 2008). The social field needs to be understood from the participants’ perspective, but the researcher must also reflect on her impact on the field studied (Geertz, 1973). Ethnographic research aims to provide detailed and rich accounts of the social field studied, including accounts of interactions of participants and how these interactions can be understood.

There are several similar strands of research with roots in ethnography and a focus on digital interactions, such as social media ethnography (e.g. Postill & Pink, 2012) and digital ethnography (see Caliandro, 2018). According to Kozinets, the defining features of netnography today are a systematic and updated toolbox of existing methods and a methodological umbrella concept for studying digitally mediated interactions (Kozinets, 2020). Now we turn to some defining features of digital culture and how digital culture may be studied in digital communities or consocialities.

Miller (2020) describes three typical and defining aspects and features of digitally mediated communication: lack of context, variability, and rhizomatic organization. Our sense of context is eroded in most digital settings. For example, databases add to the lack of context in digital culture: during database searches or other interactions with database content, individual users generate context (Miller, 2020). Another challenge to our sense of context is captured with personalization, referring to how individuals’ search results and news feeds are adapted to our perceived interests and identities. The notion of variability refers to how digital objects constantly change (Miller, 2020). Web pages and databases are updated with new or revised material, software is developed, profiles on social networking services are updated, and textual and visual content are endlessly copied and altered. The concept rhizomatic organization captures how principles of connectivity underpin the very existence of the internet (Miller, 2020). Through hyperlinks, everything can potentially be connected in a non-hierarchical manner. These defining features of digitally mediated interactions offer both unique opportunities for the study of digital social life but also certain challenges. For one thing, as netnographers, we might ask: what should be the focus of our netnographic inquiry?

As indicated above, digital communities have been a common way to understand online sociality and a frequently used point of departure for netnographic studies since the beginning of netnographic research. A digital community can be understood as a group of people engaged in social interactions, building of relations, and with a common (digital) place for these interactions (Kozinets, 2010). Digital communities can be used for information sharing and for emotional support. They can be found on social network sites and internet forums, or any other digital place allowing for people to come together around a shared interest to socialize. In recent years, ethnographically oriented internet researchers have critiqued the use of concepts like community, identity, and culture (Kozinets, 2015; see also Caliandro, 2018). Given the instability of digital contexts and the variability and increasingly situational character of digitally mediated and constructed identities, the connection between certain digital interactions and membership in a digital community can be questioned.

As an alternative to the community concept, scholars have suggested the concept of consociality to better reflect the fluid and dispersed social media landscape of our time. Consociality describes “the physical and/or virtual co-presence of social actors in a network, providing an opportunity for social interaction between them” (Perren & Kozinets, 2018, p. 23). Consequently, consociality focuses on contextual fellowship and what we share rather than the identity boundary of who we are that communities imply. This conceptualization of consociality echoes how social media ethnography researchers have argued for a shift from digital communities to digital socialities (Postill & Pink, 2012). This conceptual re-orientation has consequences for netnographic research in terms of how we frame what we study and how we go about studying it. At the same time, online communities still exist and can present valuable social settings for netnographic inquiry if we avoid unreflected and uncritical use of the community concept and consider how identity positions and ways of understanding digital communities may shift. For these reasons, rather than to argue for a paradigmatic re-orientation for all kinds of netnographic research, we advocate two possible points of departure for conducting netnographic investigations:

1. Community-based netnography, using the notion of community, focused on interactions characterized by (lasting) communal ties and practices.

2. Consociality-based netnography, using the notion of consociality, focusing on interactions characterized by (fleeting) connections in contextual fellowships.

These two points of departure imply differences in what we study: digital interactions characterized by communal ties and practices, or interactions shaped by fleeting and contextual connections. The two points of departure also suggest differences in how we conduct netnographic inquiries: should we focus on active or passive approaches to netnography, and how can qualitative and quantitative procedures be understood and used depending on our methodological point of departure? Costello, McDermott, and Wallace (2017) question a perceived preference for “observational” or “non-participatory” approaches in netnographic research. “Non-participatory” approaches are employed with the intention of lurking, passively and from a certain (analytical) distance, using unobtrusive observations or quantitative procedures such as social network analysis (SNA) to study interactions among members of a digital community or in a specific social setting. Conversely, active or “participatory” approaches include interactions between researcher and participants (such as interviews), and the writing of field notes. Additionally, observations can be a part of an active approach if the researcher engages actively with the social phenomenon studied, through sustained contact, emotional involvement, and the writing of reflective field notes (Kozinets, 2020).

Methodologically, a scepsis towards excessive and uncritical use of passive approaches in netnography can be connected to ethnographic ambitions providing rich accounts of digital interactions capturing the participants’ perspective (cf. Kozinets, 2010). In netnography, however, passive approaches are valuable considering the amounts and variability of digital data and sites of the social (Kozinets, 2020; cf. Miller, 2020). To connect to our two main points of departure for doing netnography, we suggest that for community-based netnography, it is suitable to engage mainly in active approaches to engage with participants of a community over time. For consociality-based netnography, passive approaches such as selecting and archiving online traces can be enough to conduct a netnographic study. Still, a measure of active procedures such as taking field notes should be employed.

In the next section, we present three case studies with practical assignments showcasing how netnography can be taught and practiced depending on how you choose to methodologically approach netnography.

3.Presenting the OER through three case studies

The OER includes four units: Introduction to Netnography, Reflexivity and ethics in Netnography, Collecting and producing material, and Analyzing material. Each unit includes theoretical content and practical assignments that enable the learner to gradually develop a nuanced understanding of netnography and a useful skillset for doing netnographies. In the first unit, the learner is introduced to netnography as a methodology and a research field. The second unit introduces research ethics for studies in digital settings, the role of the researcher, and legal perspectives netnographers should be aware of. Unit three focuses on specific netnographic methods for collecting and producing material. Qualitative and quantitative approaches are introduced together with the notions community-based netnography and consociality-based netnography. The fourth unit introduces analytical procedures for qualitative and quantitative analyses of netnographic material.

The course is self-paced and designed to be delivered asynchronously using text, videos, interactive elements (quizzes, dialogue cards, and scenarios) and several directions for further reading. In each unit, the different learning modalities are combined to gradually further the learning of both theoretical knowledge and practical skills. Interactive elements, for example quizzes, are offered in connection to critical concepts or approaches throughout the OER to enable continuous self-evaluation and self-satisfaction (cf. Alonso-Mencía et al., 2020). Case studies and a learning scenario in three parts connect theoretical concepts, practical skills and empirical examples from cultural heritage platforms and previous research. The learning scenario New Stories for Europe can be altered if the OER is to function as a methods course that needs to be adapted to a certain educational context, such as a master’s program, using suitable empirical material connected to the specifics of that educational context instead. Overall, the OER provides a clear structure and progression but also allows for non-linear learning since units and assignments can be taken separately. This design meets the needs of both learners with low self-regulating learning skills who tend to prefer structured and linear learning, and learners with high self-regulating learning skills who often choose a more flexible and non-linear learning path (Alonso-Mencía et al., 2020).

As discussed above, the analytical distinction between community-based netnography and consociality-based netnography is a way to draw the attention of OER-students to several interconnected methodological issues critical for doing netnography: the relation between quantitative and qualitative procedures, the value and limitations of active and passive approaches to netnography, and ultimately: what is the focus of netnographic inquiry? Since the analytical concepts community and consociality form the underpinnings of the methodological considerations and discussions throughout the OER, the three case studies focus on how these two concepts can be understood and researched netnographically. The first case study focuses on how digital communities can be studied with netnographic approaches. In the second case study, the OER-students are invited to learn more about community-based netnography. The third case study focuses on consociality-based netnography. In the following, the case studies are briefly presented and discussed.

3.1Case study 1: To study digital communities

The first case study is a part of Unit 1 and focuses on how digital communities can be studied with netnographic approaches. Previously in the unit, netnography as a field of research and as a methodology has been introduced and several examples of netnographic research has been provided, allowing for OER-students to develop an understanding of what netnography is and how netnography can be done. Also, the concept ‘digital community’ is explained and positioned as a key point of departure for several netnographic studies. In case study 1, two illustrative examples of netnographic research are presented together with study questions as a way to make OER-students familiar with research on digital communities and reflect on what such research can offer insights about. Furthermore, the notions of “active” and “passive” approaches are exemplified. For the first case study, empirical examples together with valuable methodological comments are borrowed from Kozinets (2017). The OER-students are advised to consider the following study questions when reading about the example studies:

• What can the study tell us about a certain digital community?

• What might the implications of this study be (e.g., for certain fields of research, for the community)?

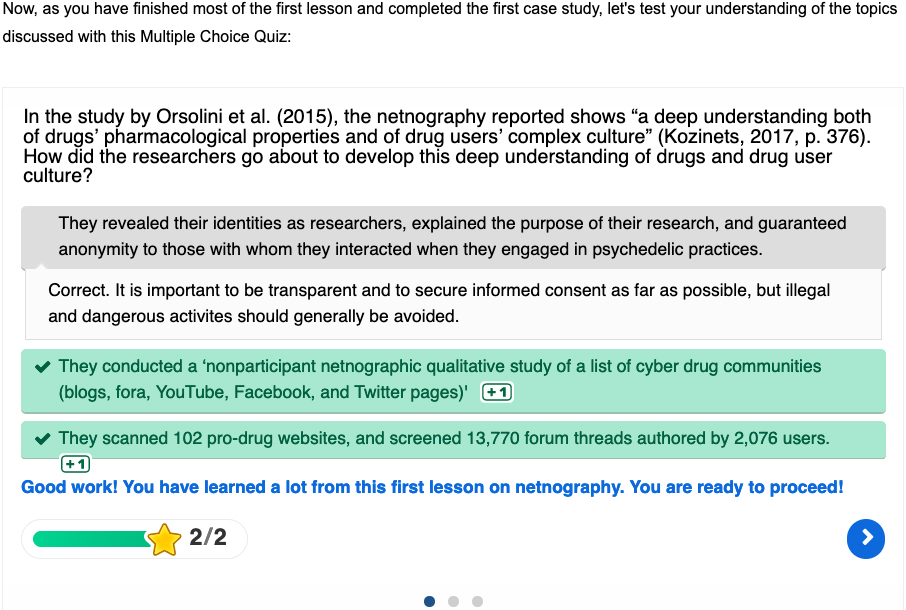

In the first example, we encounter a netnographic study focusing on people playing Restaurant City, a game hosted on Facebook (García-Álvarez et al., 2015). The study reports results from netnographic fieldwork conducted over three years. Fieldwork commenced soon after the launch of Facebook’s Restaurant City game in 2009 and the researchers started to participate in playing the game and becoming a part of the gaming community. The researchers participated in the gaming community and spent 18 months learning about the social and technical features of the Facebook game. They designed their own restaurant as part of the game and then proceeded to produce netnographic material by writing field notes, taking screenshots, and recording interactions. This brief example is contextualized by Kozinets (2017, p. 375), pointing to some important aspects the study highlights:

Demonstrating good ethical practice, they revealed their identities as researchers, explained the purpose of their research, and guaranteed anonymity to those with whom they interacted. Besides participant observation, their netnography involved the use of interview style questioning. They were thus able to delve into interesting individual perspectives and reactions which might not have revealed themselves without some interactive prompting and elicitation. Yet they were also careful to continue observing in situ, with minimal disruptions of the dynamics of interactive participation.

What this first example brings to the fore is how the researchers employ several active, or participatory, approaches and interact with participants during a lengthy time-period. Importantly, practices to secure informed consent are also discussed. Now, in the second example we will instead encounter a study that mainly employs passive, unobtrusive, approaches but that still provides a nuanced account of digital interactions among drug users (Orsolini et al., 2015). As Kozinets explains (2017, p. 376), the researchers:

[…] conducted a ‘nonparticipant netnographic qualitative study of a list of cyber drug communities (blogs, fora, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter pages)’. As they tell, us, inviting us to read critically between the lines, they were able to complete their netnography in two months, rather than the three years of García-Álvarez et al. (2015). They scanned 102 pro-drug websites, and screened 13,770 forum threads authored by 2,076 users. They further state: ‘In line with best practice protocols for online research and in compliance with unobtrusive and naturalistic features of netnographic research, no posts or other contributions to private or public forum discussions were made’ (p. 297). The terms unobtrusive and naturalistic are emphasized.

The example shows how stigmatic subjects can be researched with unobtrusive approaches, a valuable part of the netnographic methodology, with specific ethical implications. The qualitative and immersive aspects of the study allowed for the researchers to offer a rich netnographic account of a stigmatic subject, while also avoiding potential risks connected to participation or interaction in the context of drug use culture.

The first case study, that also marks the end of the main part of the first unit/lesson, is followed by a multiple-choice quiz to validate learning (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Multiple choice quiz from case study 1.

3.2Case study 2: Community-based netnography

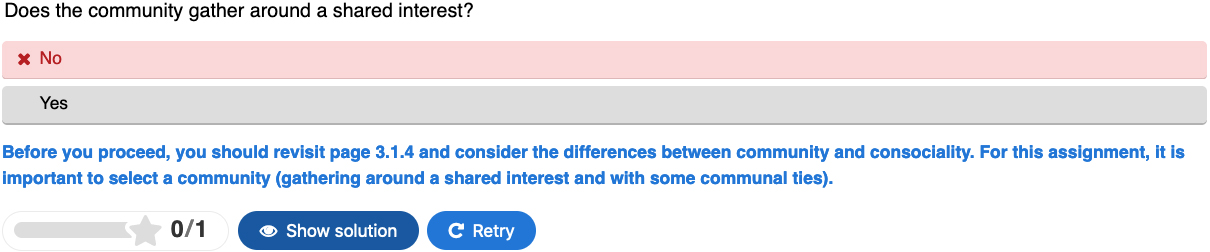

The second case study focuses on community-based netnography with active approaches. In most cases, active approaches to netnography require more time and commitment than passive approaches. This presents a pedagogical challenge since the OER-students will in most cases not be able to spend a considerable amount of time immersing in a new community. Such an endeavor would also require more knowledge and guidance than you can reasonably expect from an OER where studies are self-paced and delivered asynchronously without individual teacher supervision. The solution for allowing the OER-students to experience the dynamics of community-based netnography with active approaches is in this case study to let the students select a digital community they already consider themselves a member of. This might be a Facebook Group, an online forum, or any other digital setting where people come together around a shared interest. To provide the OER-students with a measure of guidance in this crucial first step of the case study, the students are instructed to answer a brief yes or no question before they proceed: “Does the community gather around a shared interest?”. The students are provided with a summary of how a digital community can be identified and understood if they click the “Show tip” button (in the summary central notions, such as a shared interest and lasting communal ties and practices are highlighted). If the students answer “Yes”, then they receive a confirmation that they are well underway. If they answer “No”, they are provided additional guidance (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Quiz for case study 2.

Having selected a digital community they consider themselves members of, the OER-students are instructed to reflect on the following questions:

1. What is the nature of the shared interest that has brought the participants together?

2. How is the community shaped by the nature of this shared interest (e.g., language, types of people, humor, and norms)?

3. What would seem strange or hard to understand for an outsider?

4. How is the community making use of the digital setting(s) (ways of communication, ways to foster communal ties)?

5. How is the digital platform shaping social interactions?

To practice one of the main approaches for collecting and producing netnographic material discussed in Unit III, the students are to write down the reflections as field notes. The OER-students are reminded that field notes are important tools for reflection and serve as analytical guidance when engaging in the inductive and explorative processes of netnographic research (Kozinets, 2020). Field notes capture experiences of what it is like to be a researcher, interactions with participants, and notes taken while observing and archiving online traces (such as posts to a Facebook Group) explaining the context of the situation observed. The OER-students are also advised to include reflections about themselves and their backgrounds, and how these personal aspects affect their understanding of, and interactions with, participants and phenomena in the community studied. While it might lie outside the scope of the case study as such, the students are also sensitized to how these reflections can form the basis of an auto-netnographic study (see Howard, 2020), focusing on autobiographical details, emotional connection and introspection, supplying netnographic accounts with significant reflexive depth increasing the validity of the study. However, netnographic field notes can be both extensive and detailed. To provide reasonable borders for this case study, the OER-students are instructed to write brief field notes around 200–400 words.

The next step of the case study offers the OER-students the option to design an interview guide, based on their own subjective understanding of the digital community they have selected. The OER-students are advised that the interview questions should be informed by the reflections they have written down as field notes and continue to investigate these central issues, but also leave room for the interview person to initially provide free accounts of their history in the community and their experiences (in this context, students are provided a link to a previous page outlining the interviewing method). The students are also advised that the interview, as part of this case study, might be conducted with a person they know well in the community. The main findings from the field notes and the optional interview, including procedures for informed consent, may then be presented to the interview person and then possibly to the community (in a form suitable for the community in question, and if the interview person agrees).

3.3Case study 3: Consociality-based netnography

The third case study focuses on consociality-based netnography through SNA using and comparing tools and data. Consociality-based netnography focuses on the co-presence of what social actors in a network share (Perren & Kozinets, 2018). SNA offers a quantitative understanding of connections between entities, the relations between actors and the structure of these relations (Fenton & Procter, 2019). Hence, SNA is a method for students to engage in quantitative studies of digital contextual fellowships focused on consociality to map networks. Deciding to use SNA through exploring tools is pedagogically informed by digital humanities pedagogy. Teaching is done from and through digital skills (Hirsch, 2012), as integrative learning (Nyhan et al., 2014), and based on the value of authentic technology-integrated learning (Datt et al., 2020). Of particular importance is scaffolding and play in a balanced way (Tracy & Elizabeth, 2017), enabling students to explore and assess their work according to what is important, valuable, and “good” in relation to their own interest of learning.

Teaching consociality-based netnography as social network analysis means focusing on an interest in exploring the social positioning of individuals in what they communicate through social media. Hence, it is an interest in networked individualism as patterns of relationships between social actors in a network (Kozinets, 2020). Adding SNA affords a particular interest in the graphical visualizations of social networks: maps of social networks. Meanings of interactions can be simple, like in automated online tools. They can also be deepened and analytically deduced. An example is Harland (2020) studying consocial relations and SNA in a first effort to categorize observable behavior and roles in a network of professional teachers. Furthermore, the SNA approach can be seen as an unobtrusive way to do netnography when using larger and anonymized datasets for a study.

Developing a case study for consociality-based netnography using tools for social network analysis, the use of three tools enables a scaffolding learning exercise. The tools offer the students multiple approaches to tools and their potential for consociality-based netnography. The first one is One million tweet map (http://onemilliontweetmap.com). Students are to visit the page and type in a word of particular interest by keyword, user @ or hashtag #. An automated visualized map information is provided of geolocalized data. To analyze this map as social network analysis, students are to consider the following:

• Key countries – where are they?

• What are the main clusters in the world, if any?

• How can you understand and describe any relationships between countries?

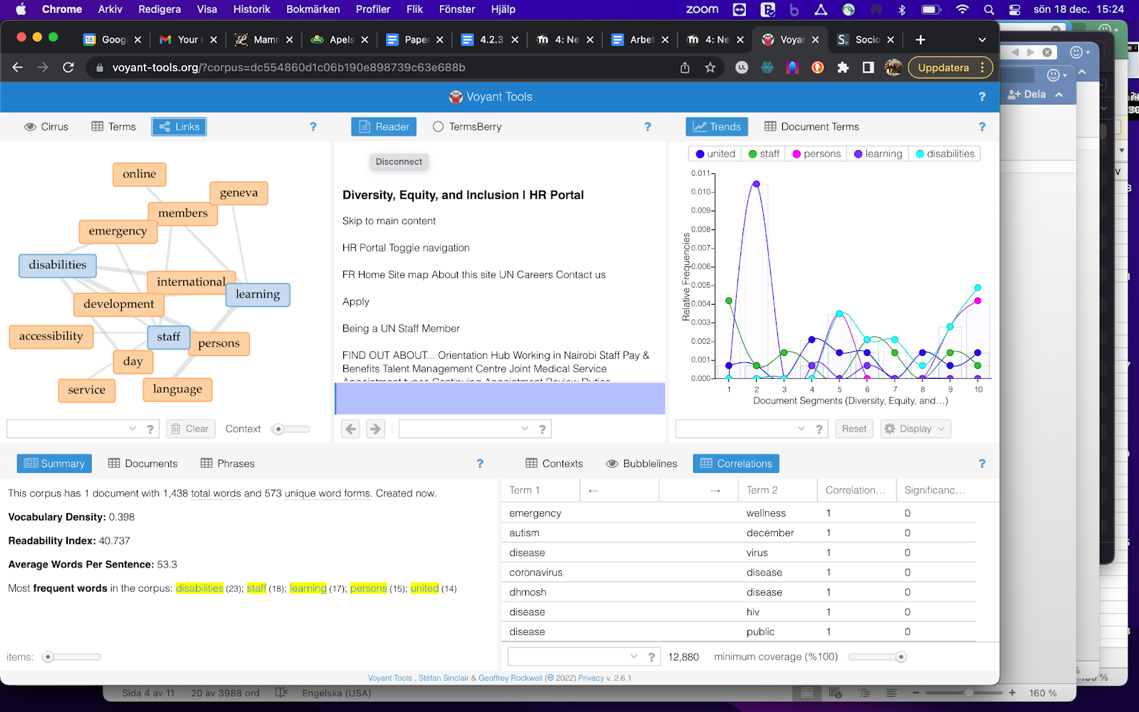

Hence, this exercise displays the limitations of connections by mainly visualizing “where”, not networks. The second tool, Voyant (http://voyant-tools.org), focuses on text-based analysis of correlations as a fundamental interest. Students must explore correlations by inserting a URL or cutting and pasting text. The automatically generated analysis of the text covers frequency and correlation with various visualizations, like word clouds (“cirrus”), Links and Bubble Lines as seen in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Automatically generated analysis of text from Voyant.

Students are to consider the following:

• Key terms – what are they, and why do you think it is so?

• What links and correlations between the words in the text do you find most interesting and why?

The third tool is SocioViz (http://socioviz.net/) where students are to do SNA of Twitter data by attaching values to the correlation as nodes and edges in a scaffolding learning way. This tool requires the students to download, register, and do tutorials. Since students are to explore SNA in several ways, different venues for doing SNA complement each other. SocioViz includes social media’s detailed analysis of user interactions, hashtags, and emoji co-presence. The tool also analyzes semantic networks, which connect well to the Voyant tool exercise. Students can in this exercise for example study social media phenomena like #blacklivesmatter (also #blm) and what user interactions exist as well as what kind of hashtag and emoji co-presence is there.

Starting from the tool offers different insights into consociality-based netnography as SNA than starting from, for example, a research question, a real-life issue, or even a dataset or database. In our experience, efforts to learn a tool do not always match the expectations from students on what the tool can do for you – however, tools matter. The various tools presented in the scaffolding structure of this case study, from simple and automated, provide a sense of what is possible. Hence, the OER offers insights on multiple web-based, open, and free tools, their risks and opportunities, and which social media data is available to use. Netnography means approaching and dealing with theoretical and methodological issues about what data is used and what tools are (and were) possible to use for SNA. With the DiMPAH OER:s, one main takeaway for students is to learn the thinking behind the tools. This assignment is mainly designed for students to understand what consociality-based netnography as social network analysis is and can be and strengthen the students to navigate and apply appropriate use of thinking and tools.

Together, the three case studies offer a nuanced understanding of netnography and useful skills for netnographic research. Next, a comprehensive and integrative assignment is outlined where students are invited to combine insights and skills from the OER to initiate and gradually develop their own netnographic projects as part of a learning scenario made up of three sections.

4.Learning scenario: New stories for Europe

The learning scenario is called New stories for Europe and includes three distinct sections where each part corresponds to a unit (Unit I, III and IV). Drawing on insights from problem-based learning (Jones, 2006), the learning scenario offers students a way to independently use knowledge and practical insights acquired from a unit and in a creative but pedagogically designed progression put this knowledge into play to formulate and then investigate netnographic research questions. Each part of the scenario allows for the students to practice and develop knowledge and skills connected to the insights gained from the corresponding unit. Although open for reiteration and non-linear learning, the scenario is meant to be worked with as a continuous assignment that students return to at the end of Unit I, III and IV. Unit II, focusing on research ethics and reflexivity, does not include a corresponding part of the learning scenario since the content of that unit should inform the entire learning scenario. In Unit II, a branching scenario is offered to allow for OER-students to test both their knowledge on research ethics in general, as well as specific netnographic project ideas. Informed by the introduction to netnography as a methodology and a field of research, and research ethical knowledge vital for aspiring netnographers, the third and fourth units teach students the basics of how to conduct an actual netnographic study of their own, from developing a good netnographic research question, collecting and producing material, to analyzing and presenting a netnographic project.

To allow students a starting point for their own netnographic projects and building both on the insights from the OER and the research interest and previous experiences of the students, in the first part of the learning scenario suggested themes for the netnographic projects are presented to the students. The themes are open-ended, which is recommended for scenario-based learning (Jones, 2006), allowing for individual creativity as the starting point and the topic is considered. At the same time, the suggested themes are meant to bring the different netnographic projects sparked by the OER together and to offer students an opportunity to contribute to the development of New stories for Europe. The four main themes, connected to important issues of contemporary Europe as described in the project goals of DiMPAH, are: social equity, transnational and cultural diversity, gender equality, and good health and well-being. Using the interactive feature dialog cards, the students can click through four dialog cards to learn more about how the different themes can be approached and explored. Figure 4 displays one of the themes, cultural diversity, as suggestions for venues for research are presented in the first part of the learning scenario as part of Unit 1 (left image), and then how OER-students can work with analyzing the netnographic material in the third and last part of the scenario (right image).

Figure 4.

Dialogue cards from part one and part three of the learning scenario.

The students are advised to choose one of these main themes, or any combination of them. With the practice of writing field notes, a central part of netnographic research that is introduced in Unit I and developed in Unit III, the students are instructed to reflect on their interests and what theme(s) would be most interesting for them to explore. The students are then to write down the selected theme(s) in their field notes (a physical notebook or a digital document), an artifact that students will use throughout the learning scenario for reflections and development of their netnographic research (cf. Kozinets, 2020). In the second part of the scenario, students are invited to develop their selected research topic, aided by instructions and exercises provided in Unit III on formulating research questions, how to understand the object of study and qualitative and quantitative netnographic approaches for collecting and producing material. Specifically, the students are to revise their netnographic research question and to create a brief research plan for collecting material. At this point, students are advised to revisit Unit II and go through the branching scenario to test the research ethics of their current project before proceeding to conduct fieldwork and collect netnographic material.

The third part of the scenario builds on insights and skills concerning key approaches for analyzing netnographic material developed in Unit IV through step-by-step exercises on coding, thematic analysis, SNA, and interpretation, and how to write netnographies and provide thick descriptions. To aid the students in the analytical process and in writing up, some possible approaches to analyze netnographic material are showcased through dialogue cards (see Fig. 4, right image) and different modalities for presenting netnographic accounts are suggested. Lastly, to highlight the connective nature of netnography, students are encouraged to share their netnographic projects with the authors of the OER and with the world using the hashtag #dimpah on Twitter, or any other digital platform.

5.Concluding remarks

Presenting and discussing central features of an OER on netnography, we have been guided by two research questions that we will now return to in this concluding section. First, we asked: How can an OER be designed that positions netnography as a viable methodology for the digital arts and humanities? As indicated in the introduction, we argue that netnography contributes to the digital arts and humanities, overall characterized by method-driven and quantitative approaches, with reflexivity and valuable perspectives for methodological considerations when doing various strands of digital research. In the OER, we present two possible points of departure for doing netnographic research: community-based netnography and consociality-based netnography. These dyadic analytical concepts together form one tangible example from the OER that promotes reflexivity and nuanced methodological consideration when doing research online, essentially by asking: what is the nature of the phenomenon we seek to study? The way we then go about studying this phenomenon needs to be informed by an answer to this basic question. As the learning scenario of the OER illustrates, netnography also opens up for research questions and projects bringing together insights, material and research from the digital arts and humanities in the human and genuine effort to understand other humans. This way, netnography offers potential for critical research and pedagogy within the digital arts and humanities, ultimately with reflexivity as a way to make visible and to challenge the “political evil” of our time, through countering injustice, oppression and the dehumanization framed by Hannah Arendt as thoughtlessness and superfluousness (Hayden, 2008). We believe this to be a valuable part of what digital scholarship can be.

The second research question, How can an OER be designed that theoretically and methodologically combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches for doing netnography?, is answered in part through the dyadic analytical concepts community-based netnography and consociality-based netnography. The concepts sensitize students to differences between online socialities, that may be based mainly on communal ties or otherwise more fleeting forms of connections in contextual fellowships. Furthermore, the concepts allow for a nuanced methodological understanding of how and when qualitative and quantitative approaches should be employed, and how they may complement each other. If we return to Miller’s (2020) view on the defining features of digitally mediated communication, we find that variability and rhizomatic organization call for quantitative approaches to navigate vast amounts of content and contexts, and to use affordances of the connectivity through digital methods such as SNA, as well as staying up to date with current tools and methods. What Miller (2020) describes as lack of context pinpoints the need for qualitative approaches to understand the subjective nature of digital interactions (cf. Kozinets, 2020). How the digital, networked online world creates both closeness and estrangement is a vivid issue for netnography, challenging how we understand both ethnographic insights and digital methods and how we go about doing ethical netnographic research.

Notes

2 This paper develops the notions of community-based and consociality-based netnography and the two corresponding examples previously outlined in the short paper “Netnography: Two Methodological Issues and the Consequences for Teaching and Practice” (Hanell & Severson, 2022) presented at the The 6th Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Conference (DHNB 2022).

Acknowledgments

The work reported here has been conducted within the Digital Methods Platform for Arts and Humanities (DiMPAH) project financed by Erasmus

References

[1] | Alang, S.M., & Fomotar, M. ((2015) ). Postpartum depression in an online community of lesbian mothers: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 19: (1), 21-39. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2014.910853. |

[2] | Alonso-Mencía, M.E., Alario-Hoyos, C., Maldonado-Mahauad, J., Estévez-Ayres, I., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Delgado Kloos, C. ((2020) ). Self-regulated learning in MOOCs: Lessons learned from a literature review. Educational Review, 72: (3), 319-345. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2019.1566208. |

[3] | Caliandro, A. ((2018) ). Digital methods for ethnography: Analytical concepts for ethnographers exploring social media environments. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 47: (5), 551-578. doi: 10.1177/0891241617702960. |

[4] | Carlsson, H., & Hanell, F. ((2020) ). Netnography in the Digital Humanities. In J. Hansson & J. Svensson (Eds.), Doing Digital Humanities: Concepts, Approaches, Cases. Växjö: Linnaeus University Press. pp. 45-64. |

[5] | Costello, L., McDermott, M.-L., & Wallace, R. ((2017) ). Netnography: Range of practices, misperceptions, and missed opportunities. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16: (1). doi: 10.1177/1609406917700647. |

[6] | Datt, A.K., Frost, J., Light, R., & Zizek, J. ((2020) ). Designing Engaging Assessments for Teaching the Digital Humanities. In E. Alqurashi (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Fostering Student Engagement With Instructional Technology in Higher Education. IGI Global. pp. 139-153. |

[7] | Davies, C.A. ((2008) ). Reflexive ethnography: A guide to researching selves and others. London: Routledge. |

[8] | Fenton, A., Keegan, B.J., & Parry, K.D. ((2021) ). Understanding Sporting Social Media Brand Communities, Place and Social Capital: A Netnography of Football Fans. Communication & Sport. doi: 10.1177/2167479520986149. |

[9] | Fenton, A., & Procter, C.T. ((2019) ). Studying social media communities: Blending methods with netnography. In: SAGE Research Methods Cases. doi: 10.4135/9781526468901. |

[10] | García-Álvarez, E., López-Sintas, J., & Samper-Martínez, A. ((2015) ). The social network gamer’s experience of play: A Netnography of Restaurant City on Facebook, Games and Culture, 12: (7-8), 650-670. doi: 10.1177/1555412015595924. |

[11] | Geertz, C. ((1973) ). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York, NY: Basic books. |

[12] | Hanell, F. ((2020) ). Co-learning in a digital community: Information literacy and views on learning in preschool teacher education. In: Proceedings of Sustainable Digital Communities: 15th International Conference, iConference 2020, Borås, Sweden, 2020, Springer Nature Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Cham, 2020. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-43687-2_26. |

[13] | Hanell, F., & Severson, P. ((2022) ). Netnography: Two Methodological Issues and the Consequences for Teaching and Practice. Paper presented at the DHNB 2022, The 6th Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Conference 2022, Uppsala, Sweden. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3232/paper19.pdf. |

[14] | Harland, D. ((2020) ). Digital colleague connectedness: A framework for studying teachers’ professional network interactions. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 10: , 393-403. doi: 10.5590/JERAP.2020.10.1.25. |

[15] | Howard, L. ((2020) ). Auto-Netnography in Education: Unfettered and Unshackled. In R.V. Kozinets & R. Gambetti (Eds.), Netnography Unlimited: Understanding Technoculture Using Qualitative Social Media Research. Routledge. pp. 217-240. |

[16] | Hayden, P. ((2008) ). Political evil in a global age: Hannah Arendt and international theory. Routledge. |

[17] | Hirsch, B.D. (Ed.). ((2012) ). Digital humanities pedagogy: Practices, principles and politics (Vol. 3). Open Book Publishers. |

[18] | Jones, R.W. ((2006) ). Problem-based learning: Description, advantages, disadvantages, scenarios and facilitation. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 34: (4), 485-488. |

[19] | Kozinets, R.V. ((2010) ). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. |

[20] | Kozinets, R.V. ((2015) ). Netnography: Redefined (2 ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. |

[21] | Kozinets, R. ((2017) ). Netnography: radical participative understanding for a networked communications society. In C. Willig, & W. Rogers, The SAGE Handbook of qualitative research in psychology. pp. 374-380. SAGE Publications, doi: 10.4135/9781526405555.n22. |

[22] | Kozinets, R.V., Scaraboto, D., & Parmentier, M.-A. ((2018) ). Evolving netnography: How brand auto-netnography, a netnographic sensibility, and more-than-human netnography can transform your research. Journal of Marketing Management, 34: , 3-4, 231-242. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2018.1446488. |

[23] | Kozinets, R.V. ((2020) ). Netnography: The essential guide to qualitative social media research (3 ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. |

[24] | Leckner, S., & Severson, P. ((2019) ). Exploring the meaning problem of big and small data through digital method triangulation. Nordicom Review, 40: (s1), 79-94. doi: 10.2478/nor-2019-0015. |

[25] | Miller, V. ((2020) ). Understanding digital culture. Sage. |

[26] | Nyhan, J., Terras, M., & Mahony, S. ((2014) ). Digital Humanities and Integrative Learning. In Daniel Blackshields, James Cronin, Bettie Higgs, Shane Kilcommins, Marian McCarthy, Anthony Ryan (Eds.), Integrative Learning International research and practice. Routledge. |

[27] | Orsolini, L., Papanti, G.D., Francesconi, G., & Schifano, F. ((2015) ). Mind navigators of chemicals’ experimenters? A web-based description of e-psychonauts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18: (5), 296-300. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0486. |

[28] | Perren, R., & Kozinets, R.V. ((2018) ). Lateral exchange markets: How social platforms operate in a networked economy. Journal of Marketing, 82: (1), 20-36. doi: 10.1509/jm.14.0250. |

[29] | Postill, J., & Pink, S. ((2012) ). Social media ethnography: The digital researcher in a messy web. Media International Australia, 145: (1), 123-134. doi: 10.1177/1329878X1214500114. |

[30] | Shumar, W., & Madison, N. ((2013) ). Ethnography in a virtual world. Ethnography and Education, 8: (2), 255-272. doi: 10.1080/17457823.2013.792513. |

[31] | Tracy, D.G., & Elizabeth, M.H. ((2017) ). Scaffolding and play approaches to digital humanities pedagogy: Assessment and iteration in topically-driven courses. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11: (4). |