Information-seeking behaviours of teacher students: A systematic review of quantitative methods literature

Abstract

Teachers are the key to an inclusive and quality education for all. Therefore, training teachers and teacher students and understanding how they learn, including information-seeking behaviours, is crucial. This systematic literature review explores the observed research gap regarding teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours. Of specific interest is information-seeking affective behaviours and the research practice context. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guided the review process. Searches were conducted in three key research databases and resulted in 1006 references. Abstracts and titles were screened and assessed using Rayyan. After screening, 56 publications were chosen for the qualitative synthesis, of which 39 used only or partly quantitative methods and thereby of interest for the review. The high number of studies resulted in a need to divide the review into two studies. The second part will focus on qualitative methods studies. The results were then analysed through thematic analysis. The results revealed a research gap regarding quantitative and mixed methods studies of non-normative and qualitative features of teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours, especially affective behaviours and in research practices. This is the first systematic review of teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours. Thus, a valuable contribution to information-seeking behaviour and information literacy research has been provided.

1.Introduction

1.1Background and rationale

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) (2015) and its member states recognise teachers as the key to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 of the 2030 Agenda: “Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong opportunities for all”. In this world’s most ambitious agenda for sustainable development, teachers are acknowledged as fundamental for guaranteeing quality education. To accomplish that, the training of teachers and teacher students is considered crucial. Studying how teacher students learn and the behaviours related to and affecting the learning process appear in this light as important. This also applies to learning about information seeking. Knowledge of information seeking and other information literacies and the behaviours that affect the process is essential for contributing to a high-quality teacher education.

Unlike other university students, teacher students not only study and learn different subjects, they also study some subjects they are going to teach as future teachers and the didactics of the subjects. This double perspective is also valid regarding information seeking and other information literacies, that is, a person’s ability to identify the need for, seek, critically evaluate, and use information for solving problems in different contexts (e.g. Limberg et al., 2012). The importance of teaching pupils information literacy is manifested in UNESCO’s Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Teachers (2014). Here, information literacy is considered as crucial knowledge in an increasingly complex information landscape characterised by alternative facts and truths, and information literacy learning outcomes are outlined. Teachers worldwide have the responsibility to implement the curriculum and educate future citizens in accordance with these learning outcomes. Given this double perspective, learning information literacy appears to be especially interesting and complex regarding teacher students, even though the didactic future teaching information-seeking content is different and on a different level than the characteristics of information seeking needed for successful academic studies and professional practice based on research and evidence.

In recent years, the teaching profession has been strongly influenced by the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) movement, which originated in the field of medicine. The notion that empirical evidence should guide teaching practice is not new; however, the strong impact of the EBP movement and other related trends, such as large-scale international comparative studies like the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is. Also new is the emergence of organisations such as the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) that collect, review, synthesise, and report on empirical educational intervention studies. Information seeking plays a vital role in EBP since finding the best available evidence is a cornerstone in all EBP models and processes (Emmons et al., 2009; Kvernbekk, 2017; van Ingen, 2013).

In view of the importance of future highly qualified teachers, prepared with the necessary literacies, including information seeking, this review will explore the empirical evidence on the behaviours of teacher students in relation to information seeking, their information-seeking behaviours. Thus, researchers and practitioners are provided with a useful research overview as well as ideas and direction for further exploration.

Before addressing the aim and research questions guiding the review, key concepts are presented. These helped defining and contextualising the behaviours and informed the search strategy of relevant search terms to use. In addition, the concepts guided the thematic analysis where codes and themes were deducted from the definitions and context and provided the lens through which the results of the thematic analysis were finally discussed and explained. The systematic review process is then described. The final step, the results of the qualitative synthesis, describes the process of identifying themes across the publications and presents the publications in each theme with the help of thematic analysis. Finally, the results are discussed, and conclusive potential contributions and implications for researchers and practitioners are suggested together with limitations.

1.2Key concepts

The research areas in LIS where people’s behaviours when engaging with information are studied, are vast and complex. This is not the place to provide any deeper explanation and description of them. Relevant for this review, however, is the aspect where task-based information seeking and the behaviours related to this activity are studied, the information-seeking behaviours. The information-seeking behaviours studied in these areas of research are underpinned by different theoretical perspectives and epistemological traditions and the behaviours of interest have different focus. The key concepts used in this context, and their relations, are presented in this section. Wilson’s (1999) frequently cited nested model divides information behaviour research into subfields. Information behaviour is the main field within which information-seeking behaviour constitutes the field that studies “the variety of methods people employ to discover and gain access to information sources” (p. 263). Information-searching behaviour is “a sub-set of information-seeking, particularly concerned with the interactions between information user [

In another conceptual model or framework of information behaviour research, Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton (2014) summarise the epistemological and methodological theoretical approaches. From a Cartesian perspective, research is characterised as either assuming the Cartesian split between mind and body, or not. Three approaches are identified: positivist (Cartesian, analytical perspective), post-positivist (Cartesian, interpretivist e.g. social constructivist perspective) and phenomenological (Cartesian and non-cartesian holistic perspective). The positivist/analytical approach is oriented towards obtaining knowledge of observable and pre-defined information behaviours and producing generalisable results through preferable quantitative data and statistical analysis. From the post-positivist/interpretivist approach, researchers are interested in knowing how people, often in a specific context and through theoretical lenses, construct (e.g. constructivism) their information experiences. Results are achieved by gathering both quantitative and qualitative data. In the phenomenological/holistic approach, people’s information experiences are not analysed through pre-defined theoretical frameworks. Researchers are more interested in people’s information experiences from their perspectives and variations in experiencing phenomena (e.g. phenomenography). Data are exclusively collected through qualitative methods.

From Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s (2014) summary of the different epistemological approaches, it is reasonable to assume that information-seeking behaviour studies should include affective factors or behaviours. In affective science, which is the study of emotion or affect, there are several competing theoretical approaches to the affective phenomena, and there is no general definition of the concepts. In an attempt to provide some useful working definitions of the various phenomena, Davidson et al. (2004, xiii) identify:

• “Emotion refers to a relatively brief episode of coordinated brain, autonomic, and behavioural changes that facilitate a response to an external or internal event of significance for the organism.

• Feelings are the subjective representation of emotions. […]

• Mood typically refers to a diffuse affective state that is often of lower intensity than emotion, but considerably longer in duration. […]

• Attitudes are relatively enduring, affectively coloured beliefs, preferences, and predispositions toward objects or persons.

• Affective style refers to relatively stable dispositions that bias an individual toward perceiving and responding to people and objects with a particular emotional quality, emotional dimension, or mood.

• Temperament refers to particular affective styles that are apparent early in life, and thus may be determined by genetic factors.”

Kuhlthau’s (1993; 2004) groundbreaking information search process (ISP) model, first published 1993 and conceptually developed in the second revised edition 2004, is one of the first to provide a holistic constructivist view of information seeking. It integrates cognitive and affective factors, or affective behaviours, in the learning process. The affective phenomena are considered to have a fundamental impact in the process of constructing meaning from information (that is learning). Kelly’s (1963) theory of personal construct underpins the affective factors in Kuhlthau’s model (2004, s. 82), which are described in relation to the six stages in the research process (initiation; selection; exploration; formulation; collection; presentation). In the ISP Feelings category these affective behaviours are: uncertainty, optimism, confusion/frustration/doubt, clarity, sense of direction/confidence, and satisfaction or disappointment. In addition, the associated interdependent process steps of Thoughts (from vague during initiation and selection to focus during formulation, increased interest from formulation to presentation) and Actions (from seeking relevant information, exploring, to seeking pertinent information, documenting) are presented in the model.

Information seeking is also an essential part of information literacy research, and a significant body of literature studying students’ information-seeking behaviours in relation to learning investigates information literacies (e.g. Lupton, 2008; Limberg et al., 2012). An established definition of information literacy is a person’s ability to identify the need for, seek, critically evaluate, and use information for solving problems in different contexts (Limberg et al., 2012). Information literacy research can thus be viewed as focused on the enactment of information-seeking abilities and learning outcomes.

Enactment is a foundational element in Lloyd’s (2017, p. 93) conceptual model of the information literacy landscape. Information literacy is enacted through “the modalities of information that reference the knowledge base” and “ways of knowing” in activities and use of “material objects and artefacts”. The activities manifest themselves in the visible elements of information literacy and the related information competencies, activities, practices, and skills.

The information literacy landscape model (Lloyd, 2017) can be approached from two different spaces: the conceptual and the practical. In the conceptual space, performed by the researcher, information literacy researchers study information literacy from a qualitative and social perspective through the lens of socially influenced learning theories such as sociocultural theory and phenomenography. The traditions structuring the information environment and landscape are problematised and described. In the practical space, the practitioner explores information literacy through a quantitative and instrumental point of view and focuses on the literacies of information and outcomes of learning, for example, the quality of teaching and curriculum and standards development (e.g. Bent & Stubbings, 2011; Association of College and Research Libraries [ACRL], 2000; ACRL, 2016). Research within this space is interested in competencies, practices, attributes and skills in particular contexts (e.g. schools, higher education) underpinned by learning theories reflecting the normative conditions of information literacy instruction.

The modalities (epistemic/instrumental, social, physical) of a specific information environment (e.g. educational information environment) in Lloyd’s (2017) model represent the ways of knowing, unique for the information environment it is part of. Lloyd and other LIS researchers (e.g. Hanell, 2019; Informationskompetenser: Om lärande i informationspraktiker och informationssökning i lärandepraktiker, 2009; Limberg et al., 2012) conceptualise and theorise such context-dependent information environments as information practices, underpinned by learning theories like Säljö’s (2010) sociocultural perspective, Vygotskij’s (2012) social constructivism and Wenger’s (1998) communities of practice. Information-seeking behaviours and literacies are viewed as enactments situated within context-specific social and information practices defined by the common collective knowledge of their members. This collective knowledge or ways of knowing affect and are affected by the behaviours and enactments of members, and, for example, a student can be part of several information practices. One such practice could be the information practice unique for the context of engaging in research activities and processes (e.g. Kuhlthau’s in relation to the ISP model), the research practice.

1.3Aim and research questions

The aim of this review is to give LIS researchers and practitioners a valuable thematic overview of contemporary empirical research on teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours. Although information-seeking behaviour and information literacy research studying higher-education students is vast (Case & Given, 2016), there are few empirical studies of how students experience and describe their information-seeking behaviours. That was one of the conclusions in the ambitious and longitudinal study, Project Information Literacy (Head, 2013). Savolainen (2015) has identified another critical gap. He argues that, although some research has been conducted by information-seeking behaviour researchers (e.g. Kuhlthau, 1993; Lopatovska & Arapakis, 2011; Savolainen, 2015; Nahl, 2007), minimal attention has been given to affective factors, such as feelings, emotions and mood since 1990s.

Table 1

Search strategy in LISTA (Library and Information Science and Technology Abstracts)

| Platform: Ebsco host Database: LISTA |

|---|

| Date:20200803 |

| (“teacher student*” OR “student teacher*” OR ”teacher educat*” OR “teacher training” OR “teacher trainee*” OR “trainee teacher*” OR “teacher candidate*” OR “preservice *” OR “pre-service *”) AND (“information literac*” OR “seek* behavio#r*” OR “information * behavio#r*” OR “search* behavio#r*” OR “information activit*” OR “information experience*” OR “information practice*” DE “LIBRARY orientation for students” OR DE “INFORMATION literacy” OR DE “ELECTRONIC information resource literacy” OR DE “INTERNET literacy” OR DE “INFORMATION literacy education” OR DE “INFORMATION literacy research” OR DE “INFORMATION literacy standards” OR DE “INFORMATION literacy digital resources” OR DE “INFORMATION-seeking behavior” OR DE “INFORMATION-seeking strategies” OR DE “BOOLEAN searching (Online information retrieval)” OR DE “ELECTRONIC information resource searching” OR DE “ASSISTED searching (Information retrieval)” OR DE “BOOLEAN searching (Online information retrieval)” OR DE “DATABASE searching” OR DE “INFORMATION-seeking strategies” OR DE “INTERNET searching” OR DE “KEYWORD searching” OR DE “ONLINE bibliographic searching” OR DE “SEARCH engines”) |

| Limitations: 2000–2020. English. |

| Number of hits: 156 |

The ambition of this systematic review is to further explore these findings and research gaps regarding teacher students. Additionally, the review will investigate whether the strong impact the EBP movement has had on the teaching profession in recent years is reflected in the literature through studies of teacher students’ research practices. Therefore, the research questions (RQ) guiding the review are:

• RQ 1 – What themes are evident in contemporary empirical research on teacher education students’ information-seeking behaviours?

• RQ 2 – To what degree is contemporary empirical research on teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours studying affective behaviours?

• RQ 3 – To what degree is empirical research on teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours studying behaviours in research practices?

2.Method – Systematic review

Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (2009) defines a systematic review as a “review of a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review” (p. 264).

In recent years, the requirement of what studies should be covered by systematic reviews has undergone a shift from only including randomised controlled trials to a more generous interpretation including qualitative and mixed method studies (Grant & Booth, 2009). With that liberal interpretation, this review was finally considered to be a systematic review and not another type of closely related one, such as a scoping or critical review, especially since the checklist and flow diagram of the PRISMA statement (2009) guided the review process, thus providing a high quality and transparency of the items described in the process.

2.1Search strategy and process

The search string consisted of two categories or blocks: teacher students and information seeking. References in each block were captured by applying synonyms and related concepts and were combined with the Boolean operator OR. The blocks were finally combined with the Boolean operator AND.

Three key databases were used to identify publications: one in library and information science, Library and Information Science and Technology Abstracts (LISTA); and two in the educational sciences, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and Education Research Complete (ERC). The searches were conducted using the interface offered by Ebsco.

Table 2

Search strategy in ERIC (Education Resources Information Center)

| Platform: Ebsco host Database: ERIC |

|---|

| Date:202083 |

| (“teacher student*” OR “student teacher*” OR ”teacher educat*” OR “teacher training” OR “teacher trainee*” OR “trainee teacher*” OR “teacher candidate*” OR “preservice *” OR “pre-service *” OR DE “Teacher Education” OR DE “Competency Based Teacher Education” OR DE “English Teacher Education” OR DE “Inservice Teacher Education” OR DE “Preservice Teacher Education” OR DE “Teacher Educator Education” DE “Preservice Teachers” OR DE “Student Teachers”) AND (“information literac*” OR “seek* behavio#r*” OR “information * behavio#r*” OR “search* behavio#r*” OR information activit* OR information experience* OR “information practice*” DE “Information Literacy” OR DE “Information Seeking” OR DE “Search Strategies”) |

| Limitations: 2000–2020. English. |

| Number of hits: 578 |

Table 3

Search strategy in ERC (Education Research Complete)

| Platform: Ebsco host Database: Education research complete |

|---|

| Date: 202083 |

| (“teacher student*” OR “student teacher*” OR ”teacher educat*” OR “teacher training” OR “teacher trainee*” OR “trainee teacher*” OR “teacher candidate*” OR “preservice *” OR “pre-service *” OR DE “TEACHER education” OR DE “ARTICLED teachers (Great Britain)” OR DE “COMPETENCY-based teacher education” OR DE “DANCE teacher education” OR DE “EDUCATION of adult educators” OR DE “EDUCATION of art teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of bilingual teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of business teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of cooperating teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of history teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of kindergarten teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of library media specialists” OR DE “EDUCATION of mathematics teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of music teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of preschool teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of social science teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of special education teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION of teachers of the deaf” OR DE “EDUCATION of teachers’ assistants” OR DE “EXTENDED teacher education programs” OR DE “METHODS courses (Teacher education)” OR DE “STUDENT teachers” OR DE “EDUCATION interns” OR DE “EDUCATION students” OR DE “PHYSICAL education students (Education students)” OR DE “TEACHERS college students” OR DE “TEACHER training” OR DE “CHRISTIAN education – Teacher training” OR DE “FOLLOW-up in teacher training” OR DE “MICROTEACHING” OR DE “OBSERVATION (Educational method)” OR DE “RELIGIOUS education – Teacher training” OR DE “STUDENT teaching” OR DE “TEACHER induction” OR DE “TEACHER orientation” OR DE “TEACHER training courses” OR DE “TEACHERS’ institutes” OR DE “TEACHERS’ workshops” OR DE “TELEVISION in teacher training” OR DE “TRAINING of adult educators” OR DE “TRAINING of art teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of business teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of early childhood teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of information science teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of language teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of library media specialists” OR DE “TRAINING of mathematics teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of music teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of physical education teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of social science teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of special education teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of student teachers” OR DE “TRAINING of teacher educators” OR DE “TRAINING of teachers of gifted children” OR DE “TRAINING of teachers’ assistants” OR DE “TRAINING of vocational teachers”) AND (“information literac*” OR “seek* behavio#r*” OR “information * behavio#r*” OR “search* behavio#r*” OR “information activit*” OR “information experience*” OR “information practice*” DE “INFORMATION literacy” OR DE “ELECTRONIC information resource literacy” OR DE “INTERNET literacy” OR DE “INFORMATION literacy education” OR DE “INFORMATION-seeking behavior” OR DE “ELECTRONIC information resource searching” OR DE “DATABASE searching” OR DE “INFORMATION-seeking strategies” OR DE “INTERNET searching”) |

| Limitations: 2000–2020. English |

| Number of hits: 272 |

In Tables 1–3, the complete search strings for each database are presented in detail with additional subject terms. Both free-text and equivalent subject terms were applied where available to minimise the risk of missing relevant references. The initial inclusion criteria are also available in the tables: publication dates covered and language. Additional information on search results and date of the searches are also provided.

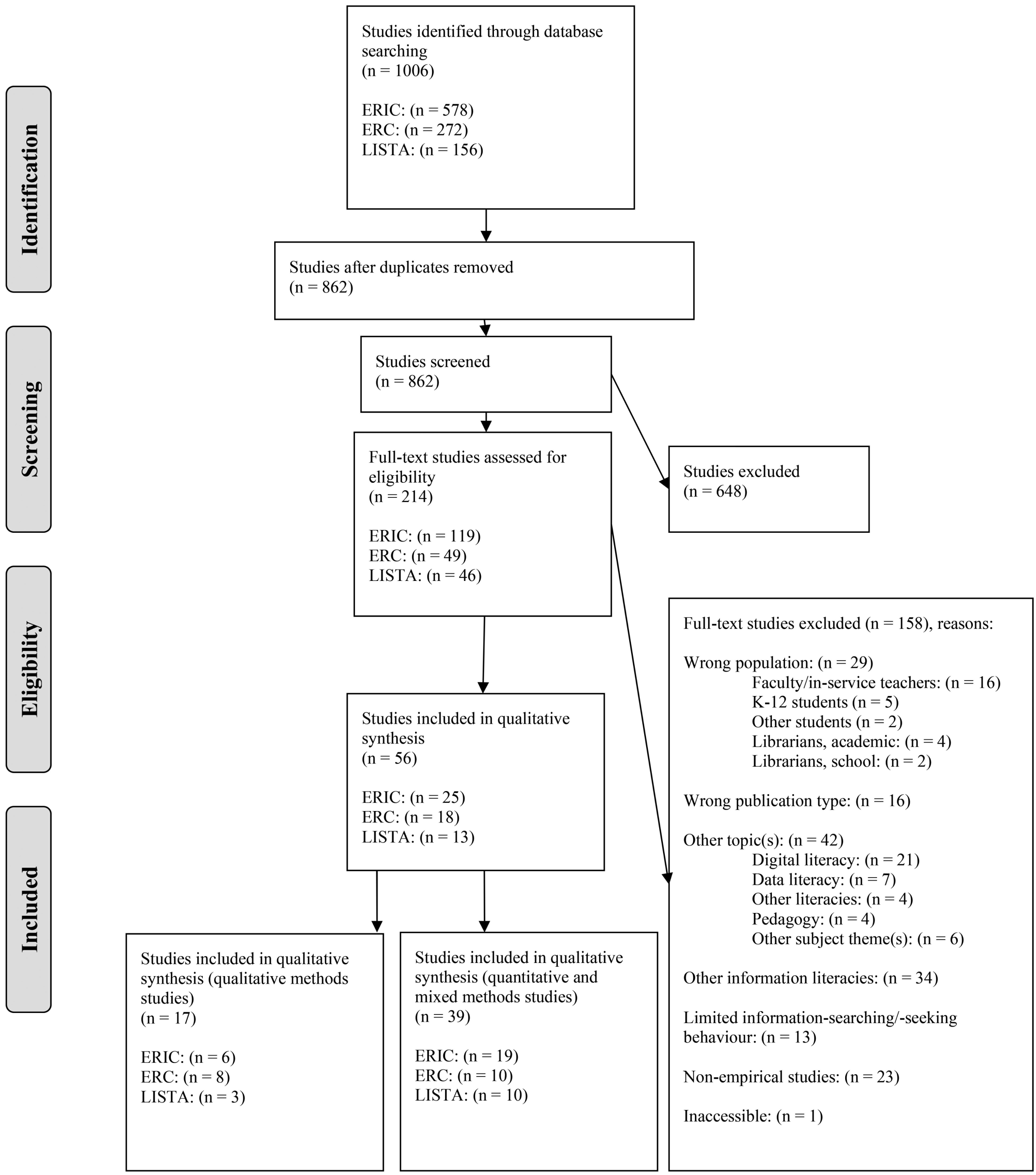

Figure 1.

Flow diagram adapted from the PRISMA statement describing the steps in the systematic review process.

In Fig. 1, a detailed account of the steps with additional figures from each database is presented in a flow diagram adapted from the PRISMA statement (2009). In the process, Rayyan software was used in the screening process. References, including abstracts, were imported from EndNote after duplicates were removed. Each reference was assessed, including or excluding it with reasons. After the screening process, 214 publications remained, which were printed and eligible for full-text assessment. In the close reading assessment stage, the inclusion criteria were narrowed, and additional exclusion criteria were applied.

2.2Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The publications included after screening and full-text assessment met the following selection criteria:

• Publications with any level of teacher students as the population of the study, from preschool to upper secondary school;

• Empirical publications;

• Publication types: journal articles, book chapters, conference papers, reports and dissertations.

Publications excluded after screening and full-text assessment were due to:

• Wrong population: faculty members, in-service teachers, K-12 students, other students, librarians (higher education, school, public), other population;

• Wrong publication type: short texts (abstracts, summaries, editorial notes, etc.), compilations (anthologies, literature reviews, compilation dissertations, proceedings, journals etc.), non-empirical studies, other (manuals, guidelines, reviews etc.);

• Wrong literacy: publications focusing on literacies interrelated to information literacy such as digital literacy, data literacy, internet literacy, critical literacy, other literacies;

• Information literacies other than information-seeking/searching (studies focusing on information use such as referencing, anti-plagiarism and source evaluation were excluded);

• Limited information-seeking/searching behaviour (publications mentioning information-seeking or searching, but not elaborating on how seeking/searching was conducted were excluded);

• Wrong topic: other seeking behaviours (e.g. help-seeking behaviour), higher-education pedagogy, pedagogy, other topics.

After assessment, 56 publications were selected for qualitative synthesis and thematic analysis, of which 39 publications used quantitative methods entirely or partly. The high number of publications that qualified for analysis resulted in a need to divide the review into two studies. This was done based on the methodological approaches of the publications. In a follow-up study, the focus will be on qualitative studies.

3.Results – Thematic analysis

In order to give a thorough and transparent description of themes, thematic analysis was used to synthesise the content of the texts. According to Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 82) a theme “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set”, and thematic analysis is “identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within the data” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 79).

The thematic analysis began with coding. In the initial stage, text extracts were identified and labelled, that is coded. Descriptive codes, which stay close to the data, were the most frequently applied type of code in the thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In the coding process, Nvivo software was used, to which the publications were imported as text-identified files, making it possible to code text extracts. All potentially relevant codes were applied during the reading process of the publications in the initial stage.

The next step was to sort the codes, find relationships between them and group them into potential themes and subthemes. This was done through the lens of the key concepts presented in Section 2. The candidate themes with codes and text extracts were deducted, reviewed and validated several times before the themes were finally named and defined. The final major themes and subthemes are presented, and the codes with additional text extract representative examples in each theme are described in the following analysis. The included publications were then analysed in accordance with the theme definitions.

The identified themes did not capture all the aspects of interest in the review. The information-seeking behaviours studied in relation to the research process (e.g. Kuhlthau’s research process in the ISP model) in research practices were specifically sought within each theme. For this purpose, a research practice code was necessary. Research practices are in the analysis viewed as informations practices, information environments that are unique with their own collective context-specific knowledge and ways of knowing. Information-seeking behaviours and literacies are situated within these information practices which affects and are affected by the members’ behaviours and enactments (Hanell, 2019; Lloyd, 2017; Limberg et al., 2012). The defintion that guided the analysis was:

• Research practices are information practices in which teacher students’ information seeking-behaviours are situated. The information practice in which teacher students’ conduct research is unique with its own collective knowledge that affects information seeking behaviours

The code representing this definition was labelled Research practice and the text extracts coded, reflected activities where the teacher students conducted research in different ways.

| Code | Text extract example |

|---|---|

| Research practice | Consistent with the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (ACRL, 2016), faculty and librarians collaboratively designed a discipline-specific project to increase student capabilities in three information literacy skills: “Searching as Strategic Exploration,” “Research as Inquiry,” and “Scholarship as Conversation.” The assignment required students to locate and evaluate three scholarly articles reporting the effectiveness of one teaching practice. Assignment structure required critiquing authority of a source, summarising, evaluating data, and connecting scholarly sources. (Burchard & Myers, 2019) |

The methodological approaches of information-seeking behaviours were also of interest and anlysed within the themes. These were deducted from the commonly accepted classification (e.g. Bryman, 2016) with definitions of social science research methodological approaches: quantitative, qualitative or a combination of them, mixed methods. Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s (2014) and Lloyd’s (2017) descriptions of methodological approaches to information-seeking research also contributed to the definitions that guided the analysis:

• Qantitative approach – researchers systematically gather emprical and pre-defined quantifiable data. The data can be ranked, measured and categorised through statistical summary and analysis. Tools for gathering the data are for example surveys or questionnaires (often with scales) and experiments.

• Qualitative approach – researchers systematically gather emprical data about peoples’ own experiences and their experienced mearning of these. The data help researchers to better understand complex human phenomena. Tools for data collection are for example interviews, focus groups and observatons.

• Mixed methods approach – researchers combines the two approaches and use a combination of tools to collect data.

Two codes were applied to capture the two approaches identified across the publications.

| Code | Text extract example |

|---|---|

| Quantitative approach | “In order to accomplish goals of this study, a questionnaire ‘Pre-service Teachers Information Literacy Questionnaire’ […] was applied”. (Akarsu, 2011) |

| Mixed methods approach | “We used a sequential mixed method research design […] that combines a large-scale quantitative survey, followed by a smaller qualitative data collection and analysis”. (Simard & Karsenti, 2016) |

Two major themes were identified, deducted from Wilson’s (1999) categorisation of the two types of information behaviour: information-seeking behaviour and information-searching behaviour.

3.1Information-seeking behaviours

Informed by Wilson’s (1999) definition, this major theme covered studies that explicitly describe information-seeking behaviours as the activities in which students use a variety of methods to discover and gain access to information. Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s (2014) information-behaviour framework and Kuhlthau’s (2004) ISP model, also helped defining the behaviours, offering a holistic view of information-seeking where affective and cognitive experiences are, in addition to activities, objects of study. The behaviours included in the theme are not limited to computer-based search tools and sources. The definition guiding the analysis was:

• Information-seeking behaviours are the variety of activities and methods, with associated affective and cognitive experiences, people engage in to discover and gain access to information.

The theme was divided into three subthemes, deducted from Lloyd’s (2017) and Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s (2014) conceptualisations of information-seeking research approaches. Lloyd’s practical/practitioner approach to information literacy research and Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s positivist/analytical approach to information behaviour research gave direction. Especially Lloyd’s conceptual model of the information literacy landscape provided the analysis with concepts to define and label the behaviours and clarify their relations. Information-seeking behaviours are enacted through its visible elements, literacies, and manifested in competencies, activities, practices, and skills. These literacies of information are often explored as outcomes of learning, underpinned by learning theories reflecting the normative conditions of information literacy learning and teaching and enacted through modalities of information that reference the knowledge base. The three subthemes were named and defined as:

• Information-seeking skills are literacies that are enacted observable information seeking behaviours, and meaurable normative outcomes of learning.

• Information-seeking activities are literacies that are enacted observable infor-mation-seeking behaviours, and not necessarly measurable normative outcomes of learning.

• Information-seeking skills pedagogy knowledge is the base from which learning activities are enacted, and measurable normative outcomes of learning. These learning activities are about information-seeking skills and the pedagogical aspects of teaching them, rather than information-seeking skills in themselves.

Twenty-five publications were included in this major theme.

3.1.1Information-seeking skills

Twenty publications were included in the theme. The text extracts coded should reflect the seeking skills aspect and one code was applied.

| Codes | Text extract example |

|---|---|

| Seeking skills | “2. How many times have you communicated one-on-one with a librarian to get assistance in an information search (face-to-face, email, or chat)? a. Never b. 1 time c. 2 times d. 3 times or more [ |

| Seeking skills | “3. What is the level of prospective teachers’ information literacy self-efficacy? [ |

Eight publications investigated students’ self-assessed information-seeking skills that were not embedded within or part of any practices, including research practices. Information literacy scales and descriptive statistics using exclusively quantitative methods were applied for different purposes in relation to variables such as gender and study background.

Three of the articles (Adigüzel, 2012; Solmaz, 2017; Sural & Dedebali, 2018) used a 29-item information literacy self-efficacy scale developed by Adigüzel (2012). On a five-point Likert scale, students rated their information-seeking skills (nine items) in the category “access to information”. Four other articles (Demıralay & Karadenız, 2010; Demirel & Akkoyunlu, 2017; Geçer, 2012; Usluel, 2007) measured students’ perceived skills with the help of a 28-item self-efficacy scale developed by Kurbanoğlu, Akkoyunlu and Umay (2006). In these articles, information-seeking skills were assessed together with other information literacies in ten items on a seven-point Likert scale.

In another study (Akarsu, 2011), students assessed their skill levels with the help of a 35-item scale, of which 14 measured information-seeking skills. On a five-point Likert-like scale, students rated their level of difficulty in seeking information.

As part of research practices, five publications measured the impact of the researchers’ learning activity interventions by surveying students’ self-assessed information-seeking skills. Four of them (Bhavnagri & Bielat, 2005; Essex & Watts, 2011; Hava & Gelibolu, 2018; Purcell & Barrell, 2014) used pre- and post-tests, and two (Essex & Watts, 2011; Ruppel et al., 2016) employed treatment and comparison groups to measure the impact. The studies used mixed methods and were integrated into courses in collaboration with faculty members. All of the studies emphasised the importance of collaboration for successful implementation of information-seeking learning activities.

In three other studies (Godbey & Dema, 2017; Kale, 2016; Rothera, 2015) researchers measured students’ information skills out of research or other contexts. Information-seeking skills levels were assessed in nine items in the theme “Accessing and Locating skills” in one exclusively quantitative study (Kale, 2016). Information-seeking strategy skills in relation to an instruction librarian intervention using videos were explored in another article (Rothera, 2015) using mixed methods. In another article with a mixed methods approach (Godbey & Dema, 2017), information-seeking skills as students as well as future teachers were explored.

In four publications, researchers measured students’ information-seeking skills in research practices. Information literacy and information-seeking learning activities were integrated into courses, stressing the importance of research-based practices for future teachers. Three of them (Burchard & Myers, 2019; Emmons et al., 2009; van Ingen, 2013) measured students’ information-seeking skills in relation to the EBP concept. Of these, two were pre- and post-test intervention studies. In the dissertation (van Ingen, 2013), mixed methods were used, and information-seeking skills and other skills were measured several times to develop a method for teaching the process of EBP. One article (Emmons et al., 2009), which was the initial part of a larger research project, also used control and comparison groups. In another mixed methods study (Burchard & Myers, 2019), students’ earlier information-seeking skills were explored as part of a research assignment explicitly training the future evidence-based teaching of students. In another article (Groß Ophoff et al., 2015), the concept of educational research literacy (ERL) was given context. ERL is similar to EBP, but is more contextualised within the educational sciences. Information literacy was one aspect of ERL that was measured in this large-scale study, which had the aim to develop a reliable test for monitoring progress in the ERL process.

3.1.2Information-seeking activities

Only one publication was included in this theme. The text extracts should capture the information-seeking activity as well as the non-normative aspect. One label was used to code.

| Code | Text extract example |

| Seeking activities | The difficulties encountered include: “information available not adequately addressing the syllabus […], inability to find relevant information easily […], information often outdated […], inadequate time […] there is a need to spur information professionals to provide means of developing better information services for teachers”. (Bitso & Fourie, 2014) |

Information-seeking difficulties and styles in relation to lesson planning were studied in this exclusively quantitative study (Bitso & Fourie, 2014), where information source preferences and communication channel choices were also studied.

3.1.3Information-seeking skills pedagogy knowledge

Four publications focused on information seeking as a skill teacher education students are going to teach as future teachers, and were included in this theme. The code applied captured extracts in the text where the future pupils’ information-seeking skills and the knowledge of teaching those skills were evident.

| Code | Text extract example |

| Seeking skills pedagogy knowledge | This statement preceded the fifth question: “Information Literacy Competencies for K-12 students (also called Information Power Standards, Handy 5, Big 6, etc.) include concepts such as: knowing how to access, evaluate and use information in order to become independent learners that allow them to become socially responsible” [ |

Two of the studies (Lee et al., 2012; Stockham & Collins, 2012) were exclusively quantitative and argued for the importance of collaboration with school librarians regarding information literacy and information-seeking instruction as future teachers.

In two articles, quantitative and qualitative methods were combined (Moreillon, 2008; Simard & Karsenti, 2016). One article (Simard & Karsenti, 2016) investigated students’ information literacies and understandings of the necessity of teaching information-seeking in relation to information communications technology (ICT). The other (Moreillon, 2008) was embedded within the curriculum describing an information-literacy pedagogy intervention with a focus on collaboration with school librarians. However, it was not part of research practice.

3.2Information-searching behaviours

The theme was defined in the same way as Information-seeking behaviours, but informed by Wilson’s (1999) definition of information-searching behaviour as the more specified type of behaviour that occurs in the interaction between user and computer-based systems. Publications studying such information-seeking behaviours, occurring in web environments with the help of digital tools, were included in this major theme. These behaviours were defined as:

• Information-searching behaviours are the variety of activities (in web environments with the help of digital tools), with associated affective and cognitive experiences, people engage in to discover and gain access to information.

The theme was divided into two subthemes. Information-searching skills was derived from Lloyd’s (2017) practical/practitioner and Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s (2014) positivist/analytical identified epistemological approaches in the same way as Information-seeking skills, resulting in the definition:

• Information-searching.skills are literacies that are enacted observable inform-ation-seeking behaviours, and measurable normative outcomes of learning.

The Information-searching emotions theme was derived from Lloyd’s (2017) conceptual/researcher space, in which the researcher describe and explain the information environment and landscape and is interested in qualitative ways of knowing (for example emotions). In addition Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s (2014) identified post-positivist/interpretivist and phenomenological/holistic approaches in which people’s construction of their information experiences is studied, provided guidance. Emotions seemed as the proper term to use, since Davidson’s et al. (2004, xiii) definitions of affective phenomena are describing emotions as objects, rather than feelings which are “the subjective representation of emotions”, resulting in the definition:

• Information-searching emotions are non-enacted and non-visible “relatively brief episodes of coordinated brain, autonomic, and behavioural changes that facilitate a response to an external or internal event of significance for the organism” (p. xiii). These information-searching emotions are not measurable normative outcomes of learning in themselves, but can be indicators of such outcomes.

In addition, Kuhlthau’s (2004) rich descriptions of emotions, although referring to them as feelings, offered examples of different kinds of emotions.

Fourteen publications were included in this second major theme.

3.2.1Information-searching skills

The subtheme covered eleven publications. The text extracts coded should reflect the searching skills aspect, and one code was applied.

| Code | Text extract example |

| Searching skills | “Aligned with the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education, this 60-minute test requires students to complete 14 scenario-based tasks that assess competency with information in seven skill areas: define, access, evaluate, manage, integrate, create, and communicate”. (Godbey, 2018) |

Three articles (Kozikoglu & Onur, 2019; Godbey, 2018; Wang, 2007) used a quantitative information literacy questionnaire, test and scale to measure information-searching skills. Students were tested in one study (Godbey, 2018) through self-assessment, and in another (Wang, 2007), the researcher validated the skills using a questionnaire. Adigüzel’s information literacy self-efficacy scale (2012) was used to measure students’ information-searching skill levels in order to predict their lifelong learning tendencies in the third article (Kozikoglu & Onur, 2019). None of the studies was part of a course or embedded within research practice.

In three other publications (Atar & Bagci, 2020; Laverty et al., 2008; Sheffield et al., 2015), mixed methods were applied. Students’ perceived and actual online searching strategy abilities were investigated in one of the articles (Laverty et al., 2008). Self and researcher-assessment of information-searching skills were measured in another article (Atar & Bagci, 2020). Web searching skills and strategies using the information commitment survey developed by Wu and Tsai (2005), were tested in six scales using a six-point Likert scale. Interviews were also conducted investigating skills and attitutes towards information searching. In another article (Kuzu & Firat, 2010), researchers tested the ability to use tools for navigation in web browsers, and in another article (Colaric et al., 2004) researchers measured students’ knowledge of search engines and Boolean operators. In a small-scale study (Acar Sesen & Ince, 2010), students’ use of keywords for a specific task was tested. Students’ self-assessed knowledge of the use of library databases was measured before and after a library instruction intervention in another small-scale study (Lamb et al., 2014).

Two studies were part of research practices. In one mixed methods study (Sheffield et al., 2015), self-assessed information literacy skills were measured quantitatively before and after the implementation of a learning activity and qualitatively though written reports. This, in a course where students should use a range of evidence-based sources. Another article, an experimental study (Poitras et al., 2019), researchers investigated students’ use of educational technology and research evidence in a lesson planning context. Based on students’ searching skills, the tutoring system was designed to optimise the system’s online resources recommendations.

3.2.2Information-searching emotions

This subtheme covered three publications studying information-searching emotions. The text extract should capture both the information-searching and emotion aspect, and one code was used.

| Code | Text extract example |

| Searching emotions | “The Deep Motives and Surface Motives items measure the participant’s online searching behaviours from a motivation perspective, such as the intention and emotions experienced in online searching. Sample items include ‘I feel that online searching can be highly interesting once I get into it’ (Deep Motives), and ‘If I do not find the information I need in the beginning, I will be frustrated and worried that I will never find it’ (Surface Motives)”. (Chen et al., 2019) |

All publications studied teacher students’ information-searching emotions in relation to online searching strategies using self-assessment scales. Two of them used the Online Searching Strategy Inventory (OISSI) 25-item scale developed by Tsai (2009) to predict searching strategies from variables such as lifelong learning (Canan Gungoren et al., 2019) and epistemological beliefs (Çevik, 2015). Teacher students assessed their searching strategy skills on a six-point Likert scale. In addition, their affective and cognitive behaviours such as feelings and thoughts, as well as strategic abilities were measured.

A similar scale, with 22 items developed by Kao (2016), was used in a study (Chen et al., 2019) to compare the online searching strategy behavior of pre-service and in-service teachers. Students assessed their strategy skills, including cognitive and affective behaviours such as intentions and emotions, on a five-point Likert scale in two dimensions: deep and surface approaches.

None of the studies was part of a course or embedded within research practice.

4.Discussion

Before discussing the results of the thematic analysis in more detail, it is appropriate to briefly answer the research questions questions (RQ) adressed:

• RQ 1 – What themes are evident in contemporary empirical research on teacher education students’ information-seeking behaviours?

Two main themes were identified applying quantitative and mixed methods approaches: Information-seeking behaviours and Information-searching behaviours. Three subthemes were found within the main theme Information-seeking behaviours: Information-seeking skills, Information-seeking activities and Information-seeking skills pedagogy knowledge. Two subthemes were within the main theme Information- searching behaviours: Information-searching skills and Information-searching emotions.

• RQ 2 – To which degree is contemporary empirical research on teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours studying affective behaviours?

Three publications studied teachers students’ affective information-seeking behaviours using quantitative and mixed methods.

• RQ 3 – To which degree is empirical research on teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours studying behaviours in research practices?

11 publications studied information-seeking behaviours in research practices using only or partly quantitative methods.

The perhaps most significant finding found in the review and that concerns all the publications is that all but one were oriented towards obtaining knowledge of normative skills, knowledge and emotions. Information-seeking behaviours were measured using surveys, questionnaires, tests, and scales. This instrumental and quantitative approach to investigate information seeking reflects Lloyd’s (2017) information literacy research practical space, where research is conducted from a practitioner’s perspective. In addition, it mirrors the positivist/analytical approach to information behaviour research conceptualised by Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton (2014).

This suggests that more quantitative and mixed methods research from a post-positivist/qualitative (Hepworth et al., 2014) and conceptual/researcher (Lloyd, 2017) perspective are needed. Qualitative factors of non-normative behaviours can be studied even with an exclusively quantitative approach and may, with complementing qualitative methods, provide even more depth and nuance. From a holistic, constructivist (e.g. Kuhlthau, 2004) point of view, learning, the construction of meaning, emanates from the learners’ prior and present experiences and behaviours. In this light, a deeper understanding of teacher students’ more qualitative features of information-seeking experiences and behaviours is crucial for developing information-seeking learning and teaching.

4.1Themes

4.1.1Information-seeking and searching skills

Information-seeking and searching skills were the predominant information-seeking behaviour in the review. Thirty-one publications investigated skills in different ways. In 17, students assessed their own skills, and researchers validated them in nine. In one study, both self- and researcher-assessment was applied. Fourteen studies used both quantitative and qualitative methods, and 11 studied the skills in research practices (nine in the subtheme Information-seeking skills and two in the subtheme Information-searching skills).

The predominance of information-seeking and searching skills was not surprising given the learning contexts in which they were studied, with a focus on enacted and observable learning outcomes in many cases influenced by skills-based guidelines and frameworks (e.g. Bent & Stubbings, 2011; ACRL, 2000; ACRL, 2016.). Perhaps more notable was that the most popular way of measuring skills was by letting students rate their skills, and researchers measured the actual skills in less than half of the studies (14, of which three were combined with students’ self-assessed skills). LIS literature has observed that students tend to overestimate their information literacy skills in relation to actual skills. Consequently, the validity of self-assessment as a predictor of actual information literacy skills has been questioned (Mahmood, 2016) and points to a need for further exploration of ways to assess teacher students’ information-seeking and searching skills.

Although as many as 14 studies applied mixed methods, potentially studying more qualitative phenomena, all the publications mirrored Lloyd’s (2017) practical/practitioner conceptualisation of information literacy research and Hepworth, Grunewald and Walton’s (2014) positivist/analytical characterisation of information behaviour research. Information-seeking and searching skills had a focus on pre-defined, enacted, observable, and normative learning outcomes and competencies, in which levels were measured through tests, scales, surveys, and questionnaires. In most cases, more than one test or scale was employed, analysing results through descriptive relational statistics.

4.1.2Information-seeking skills pedagogy knowledge

Four publications studied the didactic aspect of information-seeking skills rather than teacher students’ own information-seeking skills. Two were mixed methods studies, and none investigated research practices. Teacher students’ obervable and enacted knowledge of the necessary information-seeking skills (e.g. UNESCO, 2016; AASL, 2018) they will teach as future teachers was studied as well as their understanding of the school library/librarian as a pedagogical resource. The knowledge and understanding was measured quantitatively as learning outcomes in surveys, not providing any post-positivist/interpretivist (Hepworth et al., 2014) and conceptual/researcher (Lloyd, 2017) depth.

From a information practice perspective (e.g. Hanell, 2019; Limberg et al., 2012; Lloyd, 2017), this practice and theme is distinct from the other themes which investigates the information practice where teacher students seek information for succesful academic studies and a future teaching practice based on research and evidence. The contexts defining the practices are diffirent and the learning of information seeking skills are not transferable between the practices. However, three of the studies assumed that transferabilty and that the more research-oriented information seeking skills were necessary for teaching the type of information seekings skills they are going to teach. Clearly, there are similiraties between the practices which would be interesting to explore further from a quantitative and mixed methods approach. But from a information practice viewpoint, it is crucial to acknowledge the differences between the practices and the context-specific nature of them.

4.1.3Information-seeking activities

Teacher students’ information-seeking activities and styles were mapped in this theme, with only one publication (Bitso & Fourie, 2014). It was not part of a research practice. This is the only publication in the review that did not measure normative behaviours, indicating a post-positivist/interpretivist (Hepworth et al., 2014) and conceptual/researcher (Lloyd, 2017) information-seeking research approach. However, the information-seeking behaviours were exclusively and quantitatively pre-defined investigating enacted and obervable information-seeking behaviours and did not offer any deeper and qualitatively holistic-constructivist understanding of information-seeking activities.

4.1.4Information-seeking affective behaviours

Three publications studied affective behaviours in relation to information-seeking behaviour, and these constituted the Information-seeking emotions theme. None of them explored them in relation to research practices. All of them were exclusively quantitative and examined online information-searching affective behaviours. More than one scale was used in the studies, and descriptive statistical analysis was employed.

The emotions studied in the publications did not provide any deeper insights into students’ information-seeking emotions. In one of the studies, the emotions were assumed to be a predictor of the motives for searching the web, an assumption also explored by Savolainen regarding information-seeking behaviour (2014; 2015). If students thought online searching was highly interesting, then the motive was deep, and if students did not find information and were frustrated and worried, then it was considered as a surface motive. The only emotions found in the scale used in this study were feelings of interest and frustration and worry. In the two other publications, the same scale was used, and emotions were measured on a Likert scale in the category Disorientation. The students validated their level of emotions regarding only two statements: confusion and nervousness. The emotions were explored as predictors of normative levels of lifelong learning skills and epistemological beliefs.

The emotions of confusion and frustration in the studies are equivalent to the feelings described in the third stage of Kuhlthau’s ISP model (1993; 2004), confusion/frustration/doubt. Worry and nervousness, or the state of feeling anxious or the emotion anxiety, are the affective symptoms of uncertainty. Uncertainty is found in the first step of the feelings category in the ISP model and was also the concept around which her famous principle of uncertainty was developed. The feeling of interest measured in one of the studies is also found in the ISP model. In the cognitive category thoughts, interest is increasing from the formulation stage to the presentation stage. As Savolainen (2014) has pointed out, interest is an ambiguous concept, which Kuhlthau treated as both a cognitive and affective factor. In the information collection stage of one version of the ISP model, interest is defined as a feeling.

Even though the studies investigated emotions, indicating a holistic approach interested in non-normative behaviours, the studies had an obvious positivist/analytical (Hepworth et al., 2014) and practical/practitioner (Lloyd, 2017) approach where pre-defined normative searching behaviours were measured. The affective behaviours were indicators of normative notions of what are considered the proper ways of searching. The lack of quantitative and mixed methods research regarding teacher students’ information-seeking emotions confirms Savolainen’s (2014) finding that minimal LIS research attention has been given to affective information-seeking behaviours. This is especially true since none of the studies offered any deeper post-positivist/qualitative (Hepworth et al., 2014) and conceptual/researcher (Lloyd, 2017) explorations.

4.2Information-seeking behaviours in research practice

Across the themes, 11 publications studied information-seeking behaviours situated within practices where the students conducted research. Four of the publications did that intending to prepare students for a future evidence-based teaching practice. Eight of the studies employed both quantitative and qualitative studies. None of the publications studied affective information-seeking behaviours.

Considering the few publications that studied research practices and information practices overall (only one more publication studied information-seeking behaviour as an authentic assignment as part of a course) and the absence of studies on information-seeking affective behaviours in these, there is a need for further research. This de-contextualised approach to the study of information-seeking behaviours was rather surprising. Information-seeking and searching skills and emotions were measured out of context using generic information literacy scales and tests, and information-seeking activities and knowledge were studied using general questionnaires. This behaviouristic view of behaviours and learning is in contrast with contemporary information practice research. From an information practice perspective (e.g. Hanell, 2019; Informationskompetenser: Om lärande i informationspraktiker och informationssökning i lärandepraktiker; 2009; Limberg et al., 2012; Lloyd, 2017), the behaviours and literacies situated within the specific contexts are unique and need to be understood. This is not only to better understand the information-seeking behaviours themselves but also due to their importance and impact on learning and teaching information seeking in relation to the specific context. Particularly interesting, from a research practice perspective, would be to further explore information-seeking behaviours in relation to the concepts and processes of evidence-based practices and educational research literacy.

4.3Limitations

Since the intention was to provide an overview on a thematic level, this review does not provide any deeper analysis or discussion of the literature. Such exploration might be of interest for other LIS researchers and practitioners.

As with all systematic reviews with the ambition to cover almost all relevant research, there is always a risk of missing relevant literature. In this review, more databases could have been used, especially Library and Information Science Abstracts (LISA), which, unfortunately, was not accessible for the review. However, since LISTA, the largest LIS database, and two of the three largest within the educational sciences were systematically searched, the review has covered the vast majority of important publications. Moreover, manual searches of key journals and chain searches from the publications found may have been conducted. To avoid the risk of bias towards certain researchers and national research, these additional sources were left out.

Furthermore, only publications issued within the last 20 years written in English were included. More years could have been covered, and publications in other large languages such as Spanish and German could have been included. However, only contemporary research was of interest, and language barriers prevented the researcher from selecting publications in other languages.

5.Conclusion

This review has provided an overall thematic picture of quantitative and mixed methods research literature of information-seeking behaviours of teacher students and hopefully given information behaviour and information literacy researchers ideas and inspiration for further and deeper exploration, in particular, researchers studying higher-education students. Practising instruction academic librarians and others teaching information literacy can also benefit from the review, informing their teaching practices with quantitative methods research evidence.

Head’s (2013) claim that few empirical studies examine how students describe their information-seeking behaviours is not confirmed in this review. Clearly, there are empirical quantitative and mixed methods studies on teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours. However, as the review has revealed and as Savolainen (2014) has pointed out regarding affective behaviours, there are research gaps. Thus, in that sense, Head’s finding is valid and points to a need for more research.

Finally, previous studies reviewing the literature on teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours and information literacies, one meta-synthesis (Duke & Ward, 2009) and one annotated bibliography (Johnson & O’English, 2003) are more than ten years old. Hence, this review provides an up to date overview, hopefully filling an important gap. Additionally, the review has shown that this is the first systematic review on the topic, and it is also the first using thematic analysis for discovering themes. The careful and thorough review process described perhaps can inspire similar studies of teacher students’ information-seeking behaviours.

References

[1] | Acar Sesen, B., & Ince, E. ((2010) ). Internet as a source of misconception: “Radiation and radioactivity”. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology – TOJET, 9: (4), 94-100. |

[2] | Association of College & Research Libraries. ((2000) ). Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency. |

[3] | Association of College & Research Libraries. ((2016) ). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10150/105645. |

[4] | American Association of School Librarians. ((2018) ). AASL Standards Framework for learners. Retrieved from: https://standards.aasl.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/AASL-Standards-Framework-for-Learners-pamphlet.pdf. |

[5] | Adigüzel, A. ((2012) ). Investigating the levels of strain, from the point of various variables, at their efforts of obtain information of preservice teachers’ of secondary education. International Journal of Instruction, 5: (2), 91-108. |

[6] | Akarsu, B. ((2011) ). A study on pre-service teachers’ information literacy abilities. Latin-American Journal of Physics Education, 5: (1), 162-166. |

[7] | Atar, C., & Bagci, H. ((2020) ). The investigation of pre-service English teachers’ information searching and commitment strategies on the web. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 8: (1), 72-83. |

[8] | Bent, M., & Stubbings, R. ((2011) ). The SCONUL Seven Pillars of Information Literacy: Core Model. |

[9] | Bhavnagri, N. P., & Bielat, V. ((2005) ). Faculty-librarian collaboration to teach research skills: electronic symbiosis. Reference Librarian, 43: (89/90), 121-138. doi: 10.1300/J120v43n89_09. |

[10] | Bitso, C., & Fourie, I. ((2014) ). Information-seeking behaviour of prospective geography teachers at the National University of Lesotho. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, 19: (3). |

[11] | Braun, V., & Clarke, V. ((2006) ). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3: (2), 77-101. |

[12] | Burchard, M. S., & Myers, S. K. ((2019) ). Early information literacy experience matters to self-efficacy and performance outcomes in teacher education. Journal of College Reading & Learning, 49: (2), 115-128. doi: 10.1080/10790195.2019.1582372 |

[13] | Canan Gungoren, Ö., Gur Erdogan, D., & Kaya Uyanik, G. ((2019) ). Examination of preservice teachers’ lifelong learning trends by online information searching strategies. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology, 7: (4), 60-80. |

[14] | Case, D. O., & Given, L. M. ((2016) ). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. Bingley: Emerald. |

[15] | Çevik, Y. D. ((2015) ). Predicting college students’ online information searching strategies based on epistemological, motivational, decision-related, and demographic variables. Computers & Education, 90: , 54-63. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.09.002. |

[16] | Chen, Y.-J., Chien, H.-M., & Kao, C.-P. ((2019) ). Online searching behaviours of preschool teachers: A comparison of pre-service and in-service teachers’ evaluation standards and searching strategies. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47: (1), 66-80. |

[17] | Colaric, S. M., Fine, B., & Hofmann, W. ((2004) ). Pre-service teachers and search engines: prior knowledge and instructional implications. Paper presented at the 27th National Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, Chicago. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=ED485064&site=ehost-live. |

[18] | Cunningham, V., & Williams, D. ((2018) ). The seven voices of information literacy (IL). Journal of Information Literacy, 12: (2), 4-23. doi: 10.11645/12.2. |

[19] | Davidson, R. J., Scherer, K. R., & Goldsmith H. H. ((2003) ). Introduction. In: R.J. Davidson, K.R. Scherer & H.H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. xii-xvii). Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

[20] | Demıralay, R., & Karadenız, Ş. ((2010) ). The effect of use of information and communication technologies on elementary student teachers’ perceived information literacy self-efficacy. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 10: (2), 841-851. |

[21] | Demirel, M., & Akkoyunlu, B. ((2017) ). Prospective teachers’ lifelong learning tendencies and information literacy self-efficacy. Educational Research and Reviews, 12: (6), 329-337. |

[22] | Duke, T. S., & Ward, J. D. ((2009) ). Preparing information literate teachers: A metasynthesis. Library & Information Science Research, 31: (4), 247-256. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2009.04.003. |

[23] | Emmons, M., Keefe, E. B., Moore, V. M., Sánchez, R. M., Mals, M. M., & Neely, T. Y. ((2009) ). Teaching information literacy skills to prepare teachers who can bridge the research-to-practice gap. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 49: (2), 140-150. doi: 10.5860/rusq.49n2.140. |

[24] | Essex, J., & Watts, J.-A. ((2011) ). Trialling an indicator of the impact of two library induction models. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 17: (2), 222-233. doi: 10.1080/13614533.2011.593856. |

[25] | Geçer, A. K. ((2012) ). An examination of studying approaches and information literacy self-efficacy perceptions of prospective teachers. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, (49), 151-172. |

[26] | Godbey, S. ((2018) ). Testing future teachers: A quantitative exploration of factors impacting the information literacy of teacher education students. College & Research Libraries, 79: (5), 611-623. doi: 10.5860/crl.79.5.611. |

[27] | Godbey, S., & Dema, A. ((2017) ). Assessment and perception of information literacy skills among teacher education students. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 36: (1), 1-15. doi: 10.1080/01639269.2017.1387738. |

[28] | Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. ((2009) ). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: (2), 91-108. |

[29] | Groß Ophoff, J., Schladitz, S., Leuders, J., Leuders, T., & Wirtz, M. A. ((2015) ). Assessing the development of educational research literacy: The effect of courses on research methods in studies of educational science. Peabody Journal of Education, 90: (4), 560-573. |

[30] | Hava, K., & Gelibolu, M. F. ((2018) ). The impact of digital citizenship instruction through flipped classroom model on various variables. Contemporary Educational Technology, 9: (4), 390-404. doi: 10.30935/cet.471013. |

[31] | Head, A. J. ((2013) ). Project Information Literacy: What can be learned about the information-seeking behavior of today’s college students? Paper presented at the Association of College and Research Libraries National Conference, Indianapolis. https://www.projectinfolit.org/uploads/2/7/5/4/27541717/head_project.pdf. |

[32] | Hanell, F. ((2019) ). Lärarstudenters digitala studievardag: Informationslitteracitet vid en förskollärarutbildning [Teacher students’ digital everyday life: Information literacies at a preschool education]. Lund: Department of Arts and Cultural Sciences, Lund University. |

[33] | Hepworth, M., Grunewald, P., & Walton, G. ((2014) ). Research and practice: A critical reflection on approaches that underpin research into people’s information behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 70: (6), 1039-1053. doi: 10.1108/JD-02-2014-0040. |

[34] | Informationskompetenser: Om lärande i informationspraktiker och informationssökning i lärandepraktiker [Information literacies: On learning in information practices and information seeking in learning practices]. ((2009) ). (J. Lindberg & A. H. Lundh (Eds.). Stockholm: Carlsson. |

[35] | Johnson, C. M., & O’English, L. ((2003) ). Information literacy in pre-service teacher education: An annotated bibliography. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 22: (1), 129-139. doi: 10.1300/J103v22n01_09. |

[36] | Kale, A. S. ((2016) ). Disciplinary background, educational level and information literacy skills of pre-service teachers: A case study. SRELS Journal of Information Management, 53: , 281-291. doi: 10.17821/srels/2016/v53i4/84952. |

[37] | Kao, C. P. ((2016) ). The effect of SDLR and self-efficacy in preschool teachers by using WS learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32: (2), 128-138. |

[38] | Kelly, G. ((1963) ). A theory of personality: the psychology of personal constructs. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. |

[39] | Kozikoglu, I., & Onur, Z. ((2019) ). Predictors of lifelong learning: Information literacy and academic self-efficacy. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 14: (4), 492-506. |

[40] | Kuhlthau, C. C. ((1993) ). Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex. |

[41] | Kuhlthau, C. C. ((2004) ). Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. (2. ed.) Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited. |

[42] | Kurbanoglu, S. S., Akkoyunlu, B., & Umay, A. ((2006) ). Developing the information literacy self-efficacy scale. Journal of Documentation, 62: (6): 730-743. |

[43] | Kuzu, A., & Firat, M. ((2010) ). Determining the navigational aids use on the internet: the information technologies teacher candidates’ case. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 11: (3), 146-161. |

[44] | Kvernbekk, T. ((2017) ). Evidence-based educational practice. In G. W. Noblit (Ed.). The Oxford research encyclopedia of education. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.187. |

[45] | Lamb, J., Howard, S., & Easey, M. ((2014) ). Pre-service teachers’ use of library databases: some insights. Paper presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia, Sydney. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=ED572642&site=ehost-live. |

[46] | Laverty, C., Reed, B., & Lee, E. ((2008) ). The “I’m feeling lucky syndrome”: Teacher-candidates’ knowledge of web searching strategies. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library & Information Practice & Research, 3: (1), 1-19. doi: 10.21083/partnership.v3i1.329. |

[47] | Lee, E. A., Reed, B., & Laverty, C. ((2012) ). Preservice teachers’ knowledge of information literacy and their perceptions of the school library program. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 31: (1), 3-22. doi: 10.1080/01639269.2012.657513. |

[48] | Limberg, L., & Sundin, O. ((2006) ). Teaching information seeking: relating information literacy education to theories of information behaviour. Information Research, 12: (1). |

[49] | Limberg, L., Sundin, O., & Talja, S. ((2012) ). Three theoretical perspectives on information literacy. Human IT: Journal for Information Technology Studies as a Human Science, 11: (2). |

[50] | Lloyd, A. ((2017) ). Information literacy and literacies of information: A mid-range theory and model. Journal of Information Literacy, 11: (1). doi: 10.11645/11.1.2185. |

[51] | Lopatovska, I., & Arapakis, I. ((2011) ). Theories, methods and current research on emotions in library and information science, information retrieval and human–computer interaction. Information Processing & Management, 47: (4), 575-592. |

[52] | Lupton, M. ((2008) ). Information literacy and learning. Queensland University of Technology. |

[53] | Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. ((2009) ). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151: (4), 264-269. |

[54] | Mahmood, K. ((2016) ). Do people overestimate their information literacy skills? A systematic review of empirical evidence on the Dunning-Kruger effect. Communications in Information Literacy, 10: (2), 203-2013. doi: 10.15760/comminfolit.2016.10.2.24 |

[55] | Moreillon, J. ((2008) ). Two heads are better than one: influencing preservice classroom teachers’understanding and practice of classroom-library collaboration. School Library Media Research, 11: , 8-8. |

[56] | Nahl, D. ((2007) ). Social – biological information technology: An integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58: (13), 2021-2046. |

[57] | Pilerot, O. ((2016) ). Connections between research and practice in the information literacy narrative: A mapping of the literature and some propositions. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 48: (4), 313-321. doi: 10.1177/0961000614559140. |

[58] | Poitras, E., Mayne, Z., Huang, L., Udy, L., & Lajoie, S. ((2019) ). Scaffolding student teachers’ information-seeking behaviours with a network-based tutoring system. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35: (6), 731-746. |

[59] | Purcell, S., & Barrell, R. ((2014) ). The value of collaboration: Raising confidence and skills in information literacy with first year initial teacher education students. Journal of Information Literacy, 8: (2), 56-70. doi: 10.11645/8.2.1917. |

[60] | Rothera, H. ((2015) ). Picking up the cool tools: Working with strategic students to get bite-sized information literacy tutorials created, promoted, embedded, remembered and used. Journal of Information Literacy, 9: (2), 37-61. doi: 10.11645/9.2.2033. |

[61] | Ruppel, M., Fry, S. W., & Bentahar, A. ((2016) ). Enhancing information literacy for preservice elementary teachers: A case study from the United States. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 22: (4), 441-459. doi: 10.1080/13614533.2016.1211542. |

[62] | Savolainen, R. ((2014) ). Emotions as motivators for information seeking: A conceptual analysis. Library & Information Science Research, 36: (1), 59-65. doi: 10.1016/j.lisr.2013.10.004. |