The quality of life assessment of breast cancer patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Research investigating the quality of life (QOL) of breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy has yielded useful knowledge regarding the effects of cancer treatment on the quality of life of patients. This study reviews the assessment of the quality of life for those diagnosed with breast cancer.

DESIGN:

A systematic review was conducted.

DATA SOURCES:

This systematic review utilized online databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. A search ranging from 2018 to 2024 was carried out.

REVIEW METHOD:

Medical Subject Headings (MESH) were used for keyword selection along with other target keywords, such as “Quality of life”, “Breast cancer”, “Chemotherapy”, “Treatment side effects”, “Patient experience”, “Psychosocial well-being”, “Physical functioning”, “Emotional distress”, and “Supportive care”. We reviewed and included all English-language publications. A narrative synthesis was conducted to present the results of the studies.

RESULTS:

A total of 300 studies were obtained from the search using the specified keywords. Each result underwent another filtering round after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process led to a final selection of 20 papers that met the requirements and were included in the systematic review.

CONCLUSION:

The use of instruments to measure the quality of life (QoL) of breast cancer patients is crucial in understanding the impact of breast cancer on patients’ lives, from physical and mental health to social aspects.

1.Introduction

Patients with breast cancer undergo a variety of treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and hormonal therapy. Patients may receive various treatments based on the specific characteristics of their cancer, such as its type, stage, and size, as well as their demographic and clinical background [1]. The illness’s characteristics and scope determine the treatment approach’s selection. Chemotherapy is a treatment that can eliminate cancer cells, but it may adversely affect healthy cells [2,3].

Cancer patients, especially breast cancer patients, experience considerable QoL changes from chemotherapy. This is because the disease and therapy affect physical, emotional, social, and general health. Fatigue, nausea, vomiting, sleeplessness, appetite loss, and diarrhea might lower QoL. Understanding the disease’s effects and customizing chemotherapy therapies requires assessing a patient’s quality of life. Interdisciplinary, holistic oncological care that addresses cancer’s physical, psychological, and social aspects improves patient and family well-being [4–7].

Chemotherapy significantly impacts the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of breast cancer patients, leading to a decline in HRQoL scores during treatment. This decline is seen in various aspects of HRQoL, including global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, body image, sexual functioning, and sexual pleasure. Chemotherapy-induced side effects such as fatigue, nausea, vomiting, insomnia, loss of appetite, and diarrhea contributed to this decline despite a decrease in symptoms [8–10].

Chemotherapy worsens physical symptoms such as insomnia, nausea, fatigue, and loss of appetite in breast cancer patients. It also affects daily activities, interpersonal relationships, and self-analysis, increasing emotional and psychological imbalance. Side effects such as fatigue and nausea can affect the patient’s quality of life. Managing these symptoms through medication, lifestyle adjustments, and supportive care can improve treatment and rehabilitation [11,12].

The purpose of this literature study is to review instruments used to assess the quality of life of breast cancer patients. The information obtained will be important for developing methods to improve treatment facilities and facilitate rehabilitation and palliative care to help cancer patients cope with better recovery and improve their quality of life.

The implications of these instruments for the future quality of life of breast cancer patients are multifaceted, encompassing the development of more specific tools, the need for continuous updates to reflect changes in therapies and side effects, and the importance of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials and research [13–16].

2.Material and methods

2.1.Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We searched four electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The time interval of our search in this study was from the beginning of 2018–2024. Medical Subject Headings (MESH) were used for keyword selection along with other target keywords, such as “Quality of life”, “Breast cancer”, “Chemotherapy”, “Treatment side effects”, “Patient experience”, “Psychosocial well-being”, “Physical functioning”, “Emotional disturbance”, and “Supportive care”. We reviewed and included all English-language publications.

2.2.Study design

All interventional studies, such as randomized clinical trials, clinical trials, and quasi-experimental studies, were included in this review.

2.3.Study selection

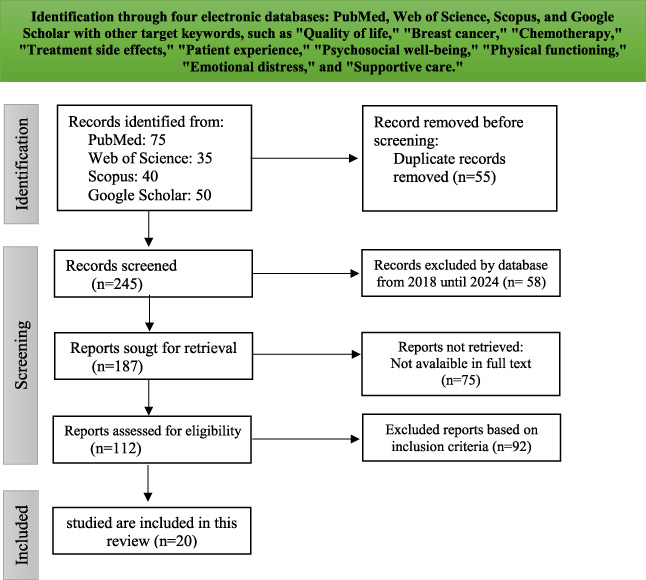

Search results were imported into Endnote software, thus eliminating duplicate records. The full texts of potentially relevant papers were read to ascertain whether they met the abovementioned inclusion criteria. Two independent reviewers were involved in the execution of this procedure. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. The study selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

3.Results

See Table 1.

4.Discussion

Chemotherapy (CT) side effects and symptoms vary by drug and patient. Studies have examined the effects of CT on quality of life, with some showing that patients who receive CT as a last resort may have better quality of life and more prolonged survival [8].

Silveira FM et al. (2021) found that 79 patients who started chemotherapy at a charity hospital referral institution in Três Lagoas, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, from June 2018 to June 2019 had an average age of 60 years. Study participants with communication issues were excluded. Quality of Life Measures test. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core 30 Quality of Life Questionnaire (version 3). The EORTC QLQ-C30 performed well in two tests. After three months of treatment, physical and cognitive function improved, but emotional function worsened. Three months into treatment, exhaustion, nausea, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, and diarrhea intensified [17].

Fig. 1.

Prisma diagram.

Chemotherapy changed patients’ HRQoL views, lowering global health status and functional measures, according to Binotto et al. (2020). Since chemotherapy side effects are commonly underestimated, this study emphasizes the importance of assessing HRQoL indicators in breast cancer patients. The authors say HRQoL measurement can improve patient care, but its use in clinical practice is complex [18].

Dano et al. (2019) studied 120 patients at the University Hospital Centre Aristide Le Dantec in Dakar, West Africa, from July 2017 to February 2018. Their average age was 45. Half of the patients had metastatic disease, and most had locally progressed disease (stage T3 to T4) and lymph node involvement. Over time, the FACT-B score increased considerably. Nausea and vomiting significantly reduced the FACT-B overall score. This study proved that Senegalese breast cancer patients could use a standardized quality-of-life measure [19].

Studies by Javan Biparva et al. (2023) yielded findings. EORTC QLQ-C30 scored 64.72, FACT-B 84.39, QLQ-BR23 66.33, and SF-36 57.23 in meta-regression of 9012 breast cancer patients. Age directly affects breast cancer patients’ quality of life, with those who completed treatment getting higher scores, according to a meta-analysis. This global systematic study identifies factors affecting breast cancer patients’ quality of life (QoL) and suggests policy changes. Quality-of-life instruments can improve clinical diagnosis, prognosis, monitoring, decision-making, treatment, and follow-up [20].

Table 1

Characteristics of inclusion studies

| No | Studi | Year | Participants | Chemotherapy regimen | Quality of life measure | Key findings (impact on Qol) | Reference |

| 1 | Silveira FM, et al. Brazil | 2021 | The convenience sample consisted of 79 participants who had a prescription for chemotherapy treatment and were over 18 years old. | Do not use continuous medication. | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire - Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30, version 3) | The EORTC QLQ-C30 indicated outstanding reliability in two evaluations. Regarding the functional scale, there has been an improvement in both physical and cognitive function, whereas emotional function declined after three months of treatment. Three months after initiating chemotherapy, the patient experienced a deterioration in the symptom scale for fatigue, nausea, dyspnea, anorexia, and diarrhea. | [17] |

| 2 | Binotto et al. Brazil | 2020 | A prospective cohort study involving 33 post-OP women diagnosed with clinical stage I-III breast cancer. | Adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment with anthracycline and/or taxane-based chemotherapy. | HRQoL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23 instruments one week before the start of chemotherapy and during the third month of chemotherapy. | Chemotherapy has a detrimental effect on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL). While HRQoL assessment is a valuable tool for enhancing patient care, implementing it in clinical practice remains challenging. Given the tendency to underestimate side effects, it is imperative to evaluate HRQoL measures in Breast Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. | [18] |

| 3 | Dano et al. West African | 2019 | Women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy as initial treatment at the Centre Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital in Dakar. (N = 120 patients) | Not use continuous medication | Health-related QoL dinilai menggunakan kuesioner Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapies-Breast (FACT-B) | The overall FACT-B score showed a notable and statistically significant improvement over time, while the presence of nausea and vomiting was found to be correlated with a reduction in the score. This validates the viability of implementing a standardized evaluation of the quality of life in breast cancer patients in Senegal. | [19] |

| 4 | Javan Biparva A, et al. Iran | 2023 | A comprehensive review of original articles published from January 2000 to October 2021 was obtained from the database. Based on meta-regression, a total of 9012 women with breast cancer were obtained. | Chemotherapy treatment | This study used the EORTC QLQ-C30, QLQ-BR23, SF-36, and FACT-B questionnaires to calculate quality of life scores. | Quality-of-life assessment methods used in clinical settings facilitate the diagnosis, prognosis, patient monitoring, decision-making, therapy, and follow-up processes by accurately evaluating the patient’s physical, mental, functional, and social well-being. | [20] |

Table 1 (Continued).

| No | Studi | Year | Participants | Chemotherapy regimen | Quality of life measure | Key findings (impact on Qol) | Reference |

| 5 | Hassen AM, et al. Ethiopia | 2019 | 404 breast cancer patients at Tikur Anbessa Specialised Hospital (TASH) daycare center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from February to April 2018. | Chemotherapy treatment | The EORTC QLQ C-30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires were designed to assess cancer patients’ quality of life (QOL). The C-30 questionnaire consists of 30 questions, including functional subscales, symptom scales, and financial impact. The QLQ-BR23 assesses the quality of life of breast cancer patients. | The quality of life of breast cancer patients is higher than average but lower below international standards. Emotional, social, and economic challenges impact their quality of life. Variables such as educational attainment, income level, financial challenges, weariness, and insomnia impacted their overall quality of life. | [21] |

| 6 | Roine, et al. Finland | 2021 | Survivors (aged 35–68 years) were randomized to the exercise trial for 12 months after additional treatment and followed up for ten years. HRQoL was assessed with the generic 15D instrument during follow-up, and the HRQoL of younger (early age 50 years) and older (age >50 years) survivors were compared to their age-matched general female population (n = 892). This analysis included 342 survivors. | Completed adjuvant chemotherapy treatment or started endocrine and radiotherapy | The scoring system uses multi-attribute utility theory. A single 15D score summarises HRQoL on a 0e1 scale (1 = perfectly healthy, 0 = dead) and dimension-level values ( | Younger survivors had a greater fall in HRQoL and shorter recovery than the general group (p < 0.001). Younger survivors had a higher reduction in HRQoL | [22 ] |

| 7 | LB Koppert, et al. The Netherlands | 2024 | A longitudinal cohort study of women with breast cancer who received different axillary treatments for staging and/or lymph node metastasis at the Erasmus MC Cancer Institute in the Netherlands between 1 November 2015 and 1 January 2022. | Received different axillary treatments, i.e., Axillary Preserving Surgery (APS) with or without Axillary Radiotherapy Or Axillary Lymph Node Dissection (ALND) with or without axillary radiotherapy | HRQoL was assessed at baseline, 6 and 12 months postoperatively using the BREAST-Q and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Module QoL Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-BR23). | Compared to APS alone, ALND with axillary irradiation significantly decreased physical and psychosocial well-being at 6 and 12 months postoperatively (p < 0.001, p = 0.035, p = 0.028). Postoperative arm symptoms improved significantly for APS with radiotherapy (12.71, 13.73) and ALND with radiotherapy (13.93, 16.14), but ALND without radiotherapy showed the least improvement (6.85, 7.66) compared to APS alone (p < 0.05). | [23 ] |

Table 1 (Continued).

| No | Studi | Year | Participants | Chemotherapy regimen | Quality of life measure | Key findings (impact on Qol) | Reference |

| 8 | Takada et al. Japan | 2019 | 300 women with breast cancer between February 2007 and December 2016 at Osaka City University Hospital | Undergoing preoperative chemotherapy (POC). | In this study, the Anti-Cancer Drugs - Breast (ACD-B) QOL score was used to assess disease-specific survival in women with breast cancer undergoing preoperative chemotherapy (POC). | In 300 breast cancer patients treated with POC, QOL significantly decreased (P < 0.001). A high QOL-ACD-B score before POC was an independent predictor in the multivariable analysis of overall survival (hazard ratio 0.26, 95% CI 0.04–0.96). | [24 ] |

| 9 | Park et al. North Carolina, US | 2021 | The project involved the Sister Study and the Two Sister Study, which enrolled around 50,884 US women aged 35–74 with breast cancer sisters. The Two Sister Study, from 2008–2010, included 1,422 young women with breast cancer, resulting in 2453 women in the final sample. | Not use continuous medication | The 10-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global health scale (PROMIS Global 10) was used to assess HRQOL domains. | In multivariate models, decreased PROMIS physical T and mental T scores were related to higher mortality (HR for physical T scores, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05–1.11; HR for mental T scores, 1.03; 95%, 1.01–1.06). The study indicated that poor HRQOL was linked to higher cancer stage, comorbidities, surgical difficulties, breast surgery dissatisfaction, and recent recurrence, metastasis, or secondary malignancy. Death rates increased with lower physical and mental T scores. | [25 ] |

| 10 | Rautalin et al. Finland | 2018 | The study surveyed 840 breast cancer patients in Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District from 2009 to 2011 | Patients were divided into five mutually exclusive groups: primary treatment | The data that were collected from the patients included three different questionnaires: EQ-5D, 15D and The EORTC QLQ-30 | The EQ-5D had a distinct upper limit impact, with 40.8% of participants achieving a score of 1 (indicating excellent health), in contrast to 6% for the 15D and 5.6% for the VAS. The regression analysis revealed that pain, exhaustion, and financial issues were the primary predictors of lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The 15D had superior discriminatory ability and demonstrated strong content validity. The EORTC QLQ-C30 showed a decline in functioning as the disease progressed, particularly in physical, social, and role functioning. The symptoms of insomnia, weariness, and pain were commonly observed across all groups. | [26 ] |

Table 1 (Continued).

| No | Studi | Year | Participants | Chemotherapy regimen | Quality of life measure | Key findings (impact on Qol) | Reference |

| 11 | Gao et al. Germany | 2023 | This analysis analyzes female breast cancer patients from a German cohort study focusing on individual radiation sensitivity, including 478 patients aged 26–87 years between 1998 and 2001. | Breast cancer (BC) patients receiving radiotherapy (RT) | HRQoL was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 at pre-RT (baseline), during radiotherapy (RT), 6 weeks after RT, and at a 10-year follow-up. | Post-treatment QoL declined but was restored to baseline after 10 years. However, younger survivors experienced functional domain deficits and symptoms. These findings emphasize the need for long-term follow-up care beyond regular post-treatment care to identify survivors at risk of sleep issues, exhaustion, and other health requirements and provide tailored psychosocial therapies to improve HRQoL and symptom burden. | [27] |

| 12 | Lewandowska et al. Poland | 2020 | The study included 800 patients, with 60% women and 40% men diagnosed with cancer undergoing chemotherapy treatment; 58% of rural residents and 42% of city residents participated in the study | Chemotherapy treatment | Quality of life was measured using the EQ-5D-5L Quality of Life Questionnaire, the Karnofsky Performance Status, our symptom checklist, Edmonton Symptom Assessment, and Visual Analogue Scale | The Karnofsky fitness index showed that 28% of cancer patients could exercise. Patients reported significant self-care and anxiety/depression issues by 81%. Cancer’s process, treatment, and longevity lower patients’ quality of life. | [28] |

| 13 | Xuan Ng Z, et al. Singapore | 2017 | Breast cancer patients face obstacles during diagnosis, treatment, post-treatment, and rehabilitation. | Treatment, post-treatment, and rehabilitation. | Literature reviews validated practices in various countries and outlines the holistic needs of patients at different stages of recovery. | The Singapore Breast Cancer Foundation and Akebono-kai in Japan help breast cancer patients reintegrate into society and employment. UK Breast Cancer Care provides extensive education. | [29] |

| 14 | Di Meglio et al., Europe | 2022 | 4,131 patients diagnosed with breast cancer from 2012 to 2015 | Chemotherapy treatment | Trajectories of QOL (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–C30 Summary Score) | The study found four cancer patient trajectory groups: excellent (51.7%), very good (31.7%), worsening (10.0%), and bad (6.6%). After diagnosis, the deteriorating group’s quality of life never recovered to pretreatment levels. Obesity, smoking, and tobacco smoking are linked to this group. Other characteristics include younger age, comorbidities, poorer income, and endocrine therapy. | [30] |

Table 1 (Continued).

| No | Studi | Year | Participants | Chemotherapy regimen | Quality of life measure | Key findings (impact on Qol) | Reference |

| 15 | Aishwarya Sunil Kshirsagar, Surendra Kiran Wani India | 2020 | Fifty patients aged over 20 years. | Chemotherapy following breast cancer surgery. | Quality of life was documented using the European Organization of Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Cancer 30 (EORTC QOL-C30) and the European Organization of Research and Treatment for Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Breast 23 (EORTC QOL-BR23). | Participants reported high discomfort, exhaustion, and insomnia in areas such as self-image, sexual dysfunction, hair loss, and systemic therapeutic side effects on the EORTC QOL-C30 questionnaire. This emphasizes the need for a complete breast cancer management strategy that includes psychiatric, emotional support, and physiotherapy. | [31] |

| 16 | Paula Poikonen-Saksela, et al. Europe | 2022 | This study involved 487 women aged 35–68 years | The patient received adjuvant chemotherapy or endocrine therapy for early-stage breast cancer. | 1. EORTC QLQ-C30: Core questionnaire 2. EORTC QLQ-BR23: Breast cancer module | The study examined mental health, tiredness, and gQoL in depressed people. After one year, median gQoL rose from 69.9 ± 19.0 to 74.9 ± 19.0. The most significant associations with gQoL were social functioning, depression, and exhaustion at baseline, and emotional functioning and fatigue at month 12. This study says therapies should include psychological support and exercise. | [32 ] |

| 17 | Muhammad Imran et al. Saudi Arabia | 2019 | This study involved 310 women | Several types of therapy given to patients include surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and radiotherapy. | The study utilized the EORTC QLQ-C30 and Breast-23, a widely used tool for assessing the quality of life in cancer patients. | Premenopausal and perimenopausal patients have a better quality of life than postmenopausal women, suggesting supportive therapy for fatigue and hair loss. | [33] |

| 18 | Tsui TCO, et al. Italy | 2022 | 408 women | Treatment, post-treatment, and rehabilitation. | EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR45 instruments | Based on EORTC’s QLQ-C30 and BR45 instruments, researchers surveyed outpatient breast cancer patients to establish a new Breast Utility Instrument (BUI) with ten dimensions of physical, emotional, social, and sexual functioning. | [34] |

Table 1 (Continued).

| No | Studi | Year | Participants | Chemotherapy regimen | Quality of life measure | Key findings (impact on Qol) | Reference |

| 19 | Mikiyas Amare Getu, et al. Ethiopia | 2022 | This study included 248 breast cancer patients. | Histologically confirmed female breast cancer patients aged 18 years and over who are or have received curative or palliative treatment and who do not previously have primary or recurrent tumors. | The assessment procedure uses the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR45 instruments. | Ethiopian breast cancer patients employed the EORTC QLQ-BR45 questionnaire, which had excellent internal, test-retest, and content validity and positive correlations on seven of the twelve scales, indicating potential for quality of life assessment. | [35] |

| 20 | V Bjelic-Radisic, et al. Germany | 2020 | During Phases I and II, a systematic literature review was conducted on 83 potentially relevant quality-of-life issues. | Chemotherapy treatment | The EORTC QLQ-BR45 module | The EORTC QLQ-BR45 module, created from phase I and II results, comprises 45 items: 23 from QLQ-BR23 and 22 new. With a target symptom scale and satisfaction scale, the upgraded module can better analyze how new drugs affect patients’ quality of life. | [36] |

The Tikur Anbessa Specialised Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, studied the quality of life of 404 breast cancer patients who received at least one chemotherapy cycle. The EORTC QLQ-C30 and breast-specific quality of life questionnaires were employed in the investigation. With most patients rating poorly in emotional, sexual, and financial concerns, the mean quality of life score was 52.98. Education, married status, higher household income, physical and social functioning, decreased fatigue, insomnia, financial troubles, and systemic therapeutic side effects improved quality of life. This study recommends including quality of life assessment in treatment procedures and providing financial aid to breast cancer patients [21].

Youthful breast cancer survivors had a steeper decrease and slower recovery than the general population, according to a Finnish study by E. Roine et al. (2021). Younger survivors declined more throughout therapy and improved slowly but remained below population levels after ten years. At ten years, older survivors were below the population level but approached it in the first five. Both age groups remained below the population level ten years after therapy [22].

A study on axillary care and post-treatment HRQoL in breast cancer patients. APS, or complete axillary lymph node dissection, was performed on 552 individuals. Physical and psychosocial well-being deteriorated considerably for ALND with axillary irradiation compared to APS alone. Both treatments raised arm symptoms, although ALND without radiation increased the least. This study demonstrates that addressing arm symptoms per axilla therapy with patients may improve pretreatment decision-making and management expectations [23].

Quality of life (QOL) is widely examined to understand its impact on cancer therapy. This study used K. Takada et al. (2018)’s Japanese QOL-ACD-B questionnaire for breast cancer. Low QOL-ACD-B ratings before breast cancer surgery (POC) were associated with poor DFS and OS. The study indicated that poor QOL patients before POC had more extensive tumors, cutaneous infiltration, and lymph node metastasis. POC decreased QOL considerably, presumably due to adverse effects. The study observed no significant difference in QOL scores before and after POC, suggesting symptom alleviation enhanced QOL. According to this study, more mental or social QOL elements may affect prognosis [24].

Park et al. (2021) found that higher cancer stage, comorbidities, surgical complications, dissatisfaction with breast surgery, and recurrence, metastasis, or recent secondary malignancy negatively affected health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in US breast cancer survivors. The study also indicated that lower mental T and PROMIS physical scores increased death. These data demonstrate that prognostic and cancer treatment-related factors affect HRQOL in breast cancer survivors and may inform tailored survivorship care [25].

M. Rautalin et al. (2019) compared HRQoL ratings from multiple tools and examined the relationship between cancer-related symptoms and HRQoL in different breast cancer states. Health status was assessed using standard HRQoL instruments such as the 15D, EQ-5D-3L, and cancer-specific EORTC QLQ C30 questionnaires. The 15D assesses mobility, vision, hearing, respiration, sleep, and more; the EQ-5D yields utility and VAS values. The EORTC QLQ-C30 assesses symptoms, function, and quality of life. The study found that varied HRQoL instruments generate varied scores. Apparent ceiling effect on EQ-5D. Poor HRQoL was most often associated with pain and exhaustion in all illness conditions [26].

In a German study of 292 breast cancer (BC) patients, global health status/quality of life (GHS/QoL) decreased after RT and improved 6 weeks afterward before reverting to baseline after 10 years. Role function improved 10 years after diagnosis, but most functional domains decreased or stayed unchanged. HRQoL issues include emotional stress, sleep issues, and exhaustion-plagued breast cancer patients, especially those under 65. Overweight people had poorer Global Health Status/QoL and physical functioning, although living with others enhanced physical functioning and reduced dyspnea and pain. Long-term care may involve specialized screening for cancer patients at risk of psychosocial/other impairments to fulfill unmet health needs [27].

The 2020 Lewandowska et al. study revealed that quality-of-life exams are necessary to assess cancer patients’ psychological, social, and spiritual well-being, including disease symptoms and treatment effects. The study included 800 cancer patients, 60% of whom were women and 40% men undergoing chemotherapy. Although 28% of cancer patients could do typical physical activities, 81% reported severe self-care issues and anxiety/depression [28].

According to Xuan Ng et al. [29], breast cancer patients have trouble reintegrating into society and employment after treatment. The Singapore Breast Cancer Foundation and Akebono-kai in Japan offer comfort and mental health support. Breast Cancer Care in the UK provides extensive cancer treatment information. Breast cancer may be treatable thanks to advances in surgery, radiation, and drugs. Hospital care is holistic, ensuring a supportive journey for patients [29].

A Di Meglio (2022) study of 4,131 breast cancer patients from 2012 to 2015 indicated that the high-risk group had a severe and continuous deterioration in post-chemotherapy quality of life. This is mainly attributable to obesity, inactivity, and tobacco use. Endocrine therapy, younger age, comorbidities, and poverty were risk factors. The results identify patients at risk of quality of life decline and inform personalized interventions, such as early behavioral difficulties and healthy lifestyle support programs [30].

In addition, Aishwarya Sunil Kshirsagar and Surendra Kiran Wani (2020) studied 50 breast cancer patients over 20 who received chemotherapy after surgery. Participants reported excessive pain, exhaustion, insomnia, self-image, sexual dysfunction, hair loss, and systemic therapeutic side effects. This study implies that Indian breast cancer patients’ quality of life should be addressed by healthcare practitioners [31].

Research on depression, symptoms, and functioning in early-stage breast cancer patients. The study included 487 European women aged 35–68 who had completed chemotherapy or begun endocrine therapy. Depression, symptoms, and functioning were associated with a median gQoL at baseline, which improved to 74.9 ± 19.0 after one year. Social functioning, despair, and exhaustion at baseline and emotional functioning and weariness at 12 months are most affected gQoL. This study suggests that low-quality-of-life patients need psychological help and physical function improvement [32].

In 2019, Muhammad Imran et al. at King Abdulaziz University Hospital in Saudi Arabia discovered that patients with an average duration from diagnosis had superior global health status and functional scores [33].

In 2022, Tsui TCO et al. developed global quality-of-life instruments, unlike others. Using the EORTC common cancer instrument (QLQ-C30) and breast module (BR45) dimensions, the study created a new Breast Utility Instrument. QLQ-C30 and BR45 researchers questioned 408 BrC outpatients. Finally, the model contained ten dimensions: physical, role, emotional, social, body image, pain, fatigue, systemic therapy side effects, sexual, arm, breast, and endocrine therapy symptoms [34].

The EORTC QLQ-BR45 questionnaire was examined for validity and reliability among Ethiopian breast cancer patients. The study included 248 participants who completed questionnaires. The findings indicated strong internal reliability, test-retest reliability, and content validity. The questionnaire has an average CVR value of 0.76, Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.80, and basic reliability norms, except for the arm symptom scale. Seven of the twelve hypothesized scales exhibited positive correlations, showing their utility in assessing the quality of life of breast cancer patients [35].

Despite its qualities, the EORTC QLQ-BR45 needs more studies to determine its responsiveness over time and test-retest reliability at various times [37]. Changes after a phase IV international field study may require additional investigations because the instrument is novel [36].

Over the past decade, generic and particular tools have been used to measure breast cancer patients’ quality of life (QoL). These devices have helped researchers understand how breast cancer affects patients’ physical, emotional, and social well-being. These instruments’ effects on breast cancer patient’s quality of life include the need for more specific tools, ongoing updates to reflect therapy and side effect changes, and the importance of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials and research [38–40].

5.Conclusion

The adoption of instruments to assess the quality of life of breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy has significant implications for future treatment and research. Continuous evaluation, the creation of particular instruments, and the significance of patient-reported outcomes are all critical topics that require attention. Understanding the long-term effects of chemotherapy on QoL will be critical in improving the lives of breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank the publication management unit team of the graduate school for assisting in preparing this systematic review.

Ethics committee

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Funding

This article received no external funding.

Authors contribution

UH, MA, and PP study design; UH, MA, and PP databases search and articles selection; All authors participate in the debate and consensus on the articles to be included. UH, ANU, and DIA manuscript writing. AA, ANU, and DIA proofreading of the manuscript.

References

[1] | Solikhah S, , Perwitasari DA, , Sarwani D, , Rejeki S, Geographic characteristics of various cancers in Yogyakarta province, Indonesia: A spatial analysis at the community level, 23, 2022. |

[2] | Taberna M, , Moncayo FG, , Jané-salas E, , Antonio M, , Arribas L, , Vilajosana E The multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach and quality of care, 10(March): 1–16, 2020. |

[3] | Samami E, Psychological interventions in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in women with breast cancer: A systematic review, 47(2): 95–106, 2022. |

[4] | Amin S, , Joo S, , Nolte S, , Yoo HK, , Patel N, , Byrnes HF , Health-related quality of life scores of metastatic pancreatic cancer patients responsive to first line chemotherapy compared to newly derived EORTC QLQ-C30 reference values, BMC Cancer, 22: (1)(2022) . doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09661-7. |

[5] | Hajj A, , Chamoun R, , Salameh P, , Khoury R, , Hachem R, , Sacre H , Fatigue in breast cancer patients on chemotherapy: A cross-sectional study exploring clinical, biological, and genetic factors, BMC Cancer [Internet] 1–11, (2022) . doi:10.1186/s12885-021-09072-0. |

[6] | Fabi A, An integrated care approach to improve well-being in breast cancer patients, Curr Oncol Rep, 26: (4): 346–358, (2024) . doi:10.1007/s11912-024-01500-1. |

[7] | Heading G, Choosing between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G for measuring health-related quality of life in cancer clinical, Ann Oncol [Internet], 22: (10): 2179–2190, (2011) . doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq721. |

[8] | Akhlaghi E, , Lehto RH, , Torabikhah M, , Nia HS, , Taheri A, Chemotherapy use and quality of life in cancer patients at the end of life: An integrative review, 1–9, 2020. |

[9] | Kawahara T, , Taira N, , Shiroiwa T, , Hagiwara Y, , Fukuda T, , Uemura Y, Minimal important differences of EORTC QLQ-C30 for metastatic breast cancer patients: Results from a randomized clinical trial, Qual Life Res [Internet], 31: (6): 1829–1836, (2022) . doi:10.1007/s11136-021-03074-y. |

[10] | Davda J, , Kibet H, , Achieng E, , Atundo L, , Komen T, Assessing the acceptability, reliability, and validity of the EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) in Kenyan cancer patients: A cross-sectional study, 2021. |

[11] | Carmona-Bayonas A, Prediction of quality of life in early breast cancer upon completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, NPJ Breast Cancer, 7: (1)(2021) . doi:10.1038/s41523-021-00296-8. |

[12] | Bottomley A, , Reijneveld JC, , Koller M, ScienceDirect Current state of quality of life and patient-reported outcomes research, 121: 55–63, 2019. |

[13] | Paravathaneni M, , Safa H, , Joshi V, , Tamil MK, , Adashek JJ, , Ionescu F , Articles 15 years of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials leading to GU cancer drug approvals: A systematic review on the quality of data reporting and analysis, eClinicalMedicine [Internet], 68: (January): 102413, (2024) . doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102413. |

[14] | Bechmann T, , Coulter A, Are patient-reported outcomes useful in post- treatment follow-up care for women with early breast cancer? A scoping review, 117–127, 2019. |

[15] | Cardoso F, , Rihani J, , Harmer V, , Harbeck N, , Casas A, , Rugo HS Quality of life and treatment-related side effects in patients With HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer: Findings from a multicountry survey, (February): 856–865, 2023. |

[16] | Zhou K, , Bellanger M, , Lann SL, , Campone M, The predictive value of patient-reported outcomes on the impact of breast cancer treatment-related quality of life, (October): 1–10, 2022. |

[17] | Wysocki AD, , Della R, , Mendez R, , Pena SB, Original article impact of chemotherapy treatment on the quality, 1–9, 2021. |

[18] | Binotto M, Health-related quality of life before and during chemotherapy in patients with early-stage breast cancer, 1–11, 2020. |

[19] | Dano D, , Sarr O, , Ka K, , Ba M, , Badiane A, , Thiam I Quality of life during chemotherapy for breast cancer in a West African population in Dakar, Senegal: A prospective study, 1–9, 2019. |

[20] | Biparva AJ, , Raoofi S, , Rafiei S, , Kan FP, , Kazerooni M, , Bagheribayati F Global quality of life in breast cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis, 2023. |

[21] | Ababa A, , Mohammed A, , Id H, , Taye G, , Gizaw M, , Hussien M, Quality of life and associated factors among patients with breast cancer under chemotherapy at Tikur Anbessa specialized, 98: 1–13, 2019. Available from: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222629. |

[22] | Roine E, , Sintonen H, , Kellokumpu-lehtinen PL, , Penttinen H, , Utriainen M, , Vehmanen L , Long-term health-related quality of life of breast cancer survivors remains impaired compared to the age-matched general population especially in young women. Results from the prospective controlled BREX exercise study, The Breast [Internet], 59: : 110–116, (2021) . doi:10.1016/j.breast.2021.06.012. |

[23] | Peeters NJMCV, , Kaplan ZLR, , Clarijs ME, , Mureau MAM, , Verhoef C, , Van Dalen T , Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after different axillary treatments in women with breast cancer: A 1-year longitudinal cohort study, Qual Life Res [Internet], 33: (2): 467–479, (2024) . doi:10.1007/s11136-023-03538-3. |

[24] | Takada K, , Kashiwagi S, , Fukui Y, , Goto W, , Asano Y, , Morisaki T Prognostic value of quality-of-life scores in patients with breast cancer undergoing preoperative chemotherapy, 38–47, 2019. |

[25] | Park J, , Rodriguez JL, , O’Brien KM, , Nichols HB, , Elizabeth Hodgson M, , Weinberg CR Health-related quality of life outcomes among breast cancer survivors, 2021. |

[26] | Rautalin M, , Färkkilä N, , Sintonen H, , Saarto T, , Taari K, , Jahkola T , Health-related quality of life in different states of breast cancer – comparing different instruments, Acta Oncol (Madr) [Internet], 0: (0): 622–628, (2018) . doi:10.1080/0284186X.2017.1400683. |

[27] | Gao Y, , Rosas JC, , Fink H, , Behrens S, , Chang J, , Seibold P, Longitudinal changes of health-related quality of life over 10 years in breast cancer patients treated with radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery, Qual Life Res [Internet], 32: (9): 2639–2652, (2023) . doi:10.1007/s11136-023-03408-y. |

[28] | Lewandowska A, , Rudzki G, , Lewandowski T, , Próchnicki M, Quality of life of cancer patients treated with chemotherapy, 1–16, 2020. |

[29] | Ng ZX, , Ong MS, , Jegadeesan T, , Deng S, , Yap CT, Breast cancer: Exploring the facts and holistic needs during and beyond treatment, 1–11, 2017. |

[30] | Meglio AD, , Havas J, , Gbenou AS, , Martin E, , El-mouhebb M, Dynamics of long-term patient-reported quality of life and health behaviors after adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy, 40(27): 3190–3205, 2022. |

[31] | Aishwarya Sunil Kshirsagar SKW, Health-related quality of life in patients with breast cancer surgery and undergoing chemotherapy in Ahmednagar district, 2021. |

[32] | Poikonen-Saksela P, , Kolokotroni E, , Vehmanen L, , Mattson J, , Stamatakos G, , Huovinen R , A graphical LASSO analysis of global quality of life, sub scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 instrument and depression in early breast cancer, Sci Rep, 12: (1)(2022) . doi:10.1038/s41598-022-06138-2. |

[33] | Id MI, , Al-wassia R, , Alkhayyat SS, , Baig M, , Al-saati BA, Assessment of quality of life (QoL) in breast cancer patients by using EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR-23 questionnaires: A tertiary care center survey in the western region of Saudi Arabia, 1–13, 2019. |

[34] | Id TCOT, , Trudeau M, , Mitsakakis N, , Torres S, , Bremner E, , Kim D, PLOS ONE Developing the Breast Utility Instrument, a preference-based instrument to measure health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer: Confirmatory factor analysis of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and BR45 to establish dimensions, 2022. Available from: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262635. |

[35] | Getu MA, , Wang P, , Kantelhardt EJ, , Seife E, , Chen C, , Addissie A, Translation and validation of the EORTC QLQ-BR45 among Ethiopian breast cancer patients, Sci Rep, 12: (1)(2022) . doi:10.1038/s41598-021-02511-9. |

[36] | Cardoso F, , Cameron D, , Brain E, , Kuljanic K, , Costa RA, , Conroy T An international update of the EORTC questionnaire for assessing quality of life in breast cancer patients: EORTC QLQ-BR45, 31(2): 2020. |

[37] | Much V, EORTC QLQ-BR45 during the past week: During the past four weeks, 46–48. |

[38] | Ondas D, , Yes H, Complementary therapies in clinical practice the effect of breathing exercise on nausea, vomiting and functional status in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy Didem Ondas, 40(May): 2020. |

[39] | Heidary Z, , Ghaemi M, , Rashidi BH, , Gargari OK, , Montazeri A, Quality of life in breast cancer patients: A systematic review of the qualitative studies, 30: 1–10, 2023. |

[40] | Jahn F, , Wörmann B, , Brandt J, , Freidank A, , Feyer P, , Jordan K, The prevention and treatment of nausea and vomiting during tumor therapy, 382–393, 2022. |