Lifestyle Advice to Patients with Bladder Cancer: A National Survey of Dutch Urologists

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Not much is known about the extent to which urologists discuss lifestyle with patients with bladder cancer (BC), despite patients considering urologists as an important source of information and motivation.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine how often lifestyle is asked about, advised on, and referred for by Dutch urologists to patients with BC, as well as to evaluate urologists’ perceptions and barriers.

METHODS:

An anonymous online survey was sent to Dutch urologists. The survey included questions on demographics, awareness of guidelines, clinical practice (asking about, advising on, and referring for lifestyle), perceptions, and barriers with regard to smoking, body weight, physical activity, diet, alcohol consumption, and fluid intake.

RESULTS:

Most of the 49 respondents were male, affiliated with a non-academic hospital, and had over 10 years of experience. Smoking appeared to be the only lifestyle factor that patients are advised on, with 90% of urologists advising > 75% of their patients. Advice on other lifestyle factors was far less common, with 63–92% of urologists giving < 50% of their patients advice. Referral rates were low for all lifestyle factors. Lifestyle advice was generally perceived as (very) important. Almost all respondents reported one or more barriers in giving lifestyle advice. A lack of time and a perceived lack of patient interest and motivation were reported most.

CONCLUSIONS:

Apart from advice on smoking cessation, lifestyle advice is not frequently provided by urologists to patients with BC. Although urologists perceive lifestyle as important, they report several barriers to providing lifestyle advice and referring patients.

INTRODUCTION

A healthy lifestyle reduces the risk of several malignancies [1, 2] and emerging evidence also suggests beneficial effects on cancer-specific outcomes [3]. Evidence for lifestyle factors in relation to bladder cancer (BC) risk [4] as well as BC-specific outcomes [5] is largely inconsistent. Smoking is the most important risk factor for developing BC [4] and has also been associated with increased risk of BC recurrence and mortality [6]. Therefore, counselling on smoking cessation is the only lifestyle-related recommendation in the most recent European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines [7, 8].

There is considerable room for lifestyle improvement among patients with BC, as observational studies found low adherence to lifestyle recommendations [9–11]. In the Netherlands, only up to one-third of patients with NMIBC adhered to recommendations on body weight or diet [9]. Patients have reported that they hardly received lifestyle recommendations from their treating physicians, except for smoking, where 70% of the smokers were advised to quit [12]. Compared to smoking [13–15], far less is known about urologists’ practices and perceptions regarding providing other lifestyle recommendations to patients with BC. This knowledge is important since many patients mention urologists being an important source of information and motivation for smoking cessation [16, 17].

This study aimed to determine to what extent lifestyle, including smoking, body weight, physical activity, diet, and fluid intake, is asked about, advised on, and referred for by Dutch urologists to patients with BC. Our secondary aim was to evaluate urologists’ perceptions of lifestyle factors in the treatment of BC together with barriers in providing lifestyle recommendations.

METHODS

A weblink to the online anonymous survey was send to 70 urologists involved in the Dutch population-based observational studies BlaZIB [18] and Urolife [19], and was also included in the newsletter of the Dutch Association for Urology (NVU). The survey was distributed in February and March 2024. Surveys were included when ≥80% of questions were completed.

Six relevant lifestyle factors were identified from the literature and included in the survey, namely smoking, body weight, physical activity, diet, alcohol consumption, and fluid intake (non-muscle invasive bladder cancer [NMIBC] only). Survey questions and response options were based on previous surveys conducted among cancer care providers [20–26]. The survey included questions on respondents’ demographics, awareness of existing lifestyle guidelines for patients with cancer, frequency of asking about, advising on, and referring for lifestyle in clinical practice, perceptions of importance of lifestyle factors in the treatment of BC, and ten predefined barriers in providing lifestyle advice. The frequency of asking about, advising on, and referring for lifestyle was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale: ‘no one’/‘<25% ’/‘26–50% ’/‘51–75% ’/‘>75% ’. Questions on perceptions were also assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree’. Other questions were assessed using multiple choice options, and the survey was concluded with an open-ended question for general remarks.

RESULTS

Respondents

Most of the 49 respondents were male (65%) (Supplementary Table 1). The vast majority were between 40–50 (45%) or 50–60 (24%) years of age. A community hospital was the practice setting for most respondents (80%), followed by a university medical center (16%). Except for one resident in urology, all respondents were trained urologists. Two-thirds of the respondents (66%) had > 10 years of experience in clinical practice.

Awareness of lifestyle guidelines for patients with cancer

The majority (90%) of respondents reported familiarity with one or more lifestyle guidelines for patients with cancer. Almost one-thirds (31%) of the respondents reported to be aware of all guidelines. Awareness of guidelines on smoking was highest (90%), followed by body weight (71%), physical activity (70%), diet (67%), alcohol (65%), and fluid intake (30%).

Clinical practice

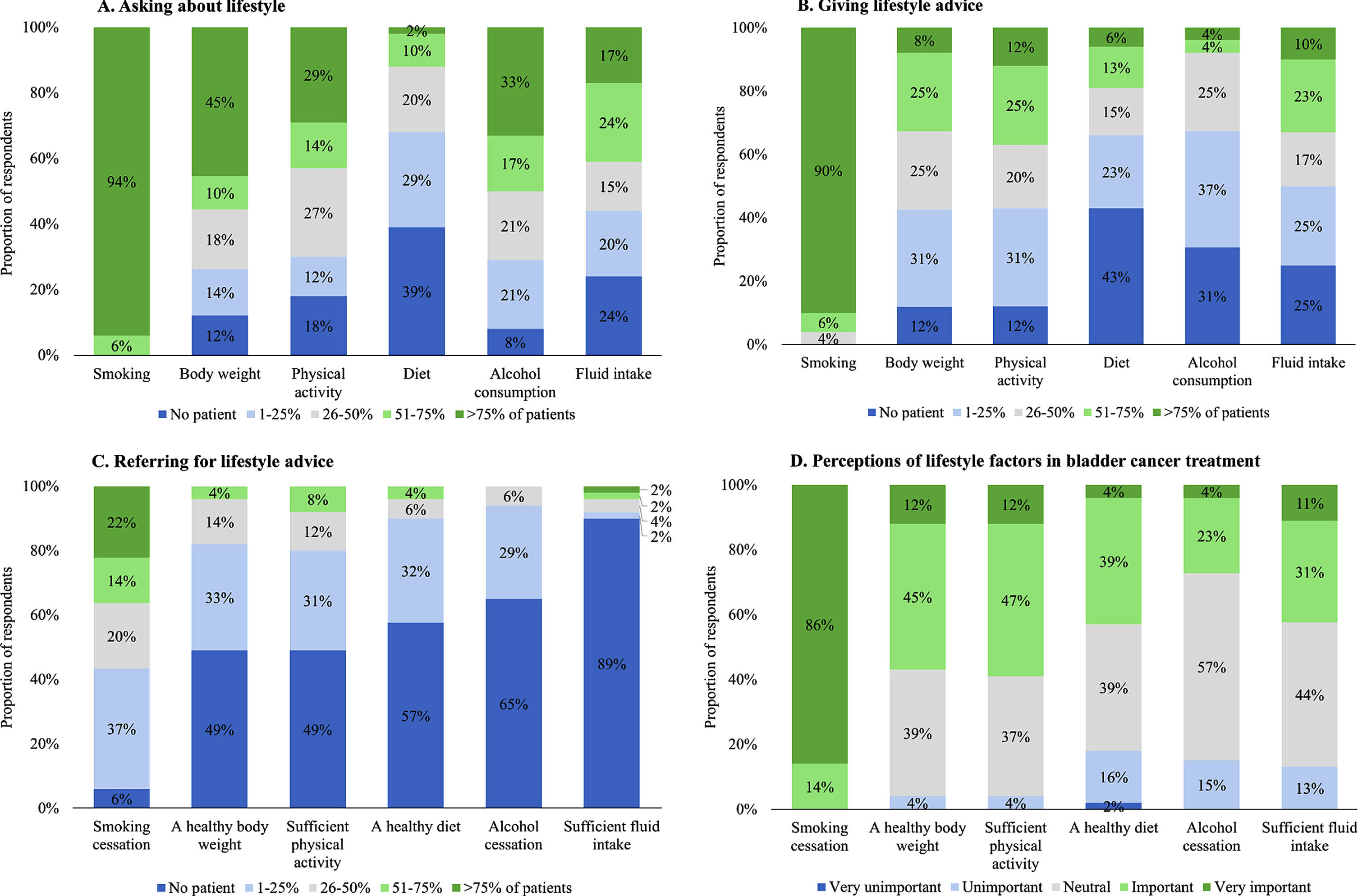

The proportion of respondents who ask about, advice on, and refer for lifestyle among patients with BC are shown in Fig. 1A, 1B, and 1C, respectively. Almost all urologists reported to structurally ask patients about smoking behavior and advise smokers to quit. Other lifestyle factors were less often addressed. Referral rates were generally low, with 0–22% referring > 75% of their patients to other healthcare providers for lifestyle advice.

Fig. 1

Proportion of responding urologists (n = 49) that (A) ask about lifestyle, (B) give lifestyle advice, or (C) refer patients to other healthcare providers for lifestyle advice, and (D) their perceptions of giving lifestyle advice to patients with bladder cancer.

Perceptions

All respondents considered giving advice on smoking cessation to be (very) important (Fig. 1D). Next in importance were sufficient physical activity and a healthy body weight, followed by a healthy diet, alcohol cessation, and sufficient fluid intake. Hardly any respondent indicated that giving advice on any of these lifestyle factors was (very) unimportant, as most remaining answers were neutral.

Barriers

The vast majority of participants (92%) reported to experience one or more barriers in giving lifestyle recommendations to patients with BC (Table 1). A lack of time and a perceived lack of patient interest and motivation were most commonly reported. Of the three respondents specifying other non-predefined barriers, two highlighted the role of the oncology nurse and one indicated that there are insufficient possibilities to refer or address this on their own.

Table 1

Barriers experienced by respondents (n = 49) in giving lifestyle recommendations to patients with bladder cancer

| Barriers | Number | Percentage |

| Insufficient evidence on the importance of lifestyle recommendations for bladder cancer outcomes | 14 | 29% |

| Insufficient knowledge on having an effective conversation about lifestyle | 13 | 27% |

| Insufficient knowledge on referral options | 15 | 31% |

| Lack of interest from patient in lifestyle recommendations | 24 | 49% |

| Insufficient motivation from patient to follow given lifestyle recommendations | 25 | 51% |

| Poor overall condition of the patient | 11 | 22% |

| Possibly creating the impression that the patient is to blame | 7 | 14% |

| Lack of time during an outpatient clinic visit | 25 | 51% |

| Lifestyle advice is not part of the responsibilities of a urologist | 1 | 2% |

| I do not experience any barriers in giving lifestyle recommendations | 4 | 8% |

| Other: | 3 | 6% |

DISCUSSION

This study shows that, apart from smoking, lifestyle is not often asked about and advised on by Dutch urologists to patients with BC. Despite urologists perceiving lifestyle advice as important, they infrequently refer patients for lifestyle advice, and almost all urologists experience barriers in giving lifestyle advice.

Smoking receives the most attention in clinical practice, as it is the best-established risk factor for bladder cancer and is explicitly mentioned in the EAU guidelines. Still, the proportion of urologists referring smokers to smoking cessation specialists or programs is low. These findings are consistent with previous studies among American urologists, who often advise patients who smoke to quit but do not offer additional counseling or referrals [14, 15]. Meanwhile, smoking cessation rates are generally low (9% to 31%) after a bladder cancer diagnosis [27–31].

The minimal focus on other lifestyle factors, including body weight, physical activity, diet, alcohol consumption, and fluid intake is in line with what has been reported by Dutch patients with NMIBC [12], and is likely attributable to urologists perceiving these as less important to advise on than smoking. It could also be explained by the involvement of oncology nurses who might discuss and advise on patients’ lifestyle. Other explanations include the reported barriers, including a lack of time and perceived lack of patient interest and motivation, which were also observed in prior studies [15, 20–26]. While most urologists were aware of cancer-specific lifestyle guidelines, insufficient available evidence for bladder cancer outcomes was reported as a barrier, highlighting the importance of research to formulate BC-specific lifestyle recommendations.

Although urologists doubt patient interest and motivation, urologists are an important source of information and reason for motivation for patients with BC in the case of smoking cessation [16, 17]. Moreover, we previously found that patients have positive attitudes regarding lifestyle advice [12]. Additional research is needed to better understand and bridge the gap between urologists’ and patients’ perspectives.

Our results might be influenced by non-response bias, as urologists more interested in lifestyle are probably more likely to respond, potentially overestimating the overall focus on lifestyle. In addition, the responding urologists might not be representative of all Dutch urologists in terms of experience, since only one resident completed our survey. Lastly, the generalizability of our results to other countries with different healthcare systems is unknown.

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the current practices, including underlying perceptions and barriers, regarding lifestyle recommendations among urologists treating patients with BC in the Netherlands. This serves as a valuable starting point for future research with the overarching aim to improve bladder cancer care. Qualitative studies are required to better understand and validate the reported barriers and to identify ways to mitigate them.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study show that Dutch urologists do not often ask about, advise on, and refer for lifestyle to patients with BC, despite urologists perceiving the provision of lifestyle advice as important. Smoking is the exception as it is often asked about and advised on which is in accordance with existing guidelines. Next to a lack of time, urologists often perceive a lack of patient interest and motivation as important barriers. Since patients with BC previously reported positive attitudes towards receiving lifestyle advice, this discrepancy warrants further research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all urologists who responded to the survey.

FUNDING

Ivy Beeren was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (2017-2/11179).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception: I.B., A.V., L.A.L.M.K., J.A.W.

Performance of work: I.B., C.K., A.V.

Interpretation of data: all authors.

Writing the article: all authors.

I.B., C.K., and A.V. had access to the data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

L.A.L.M.K. and J.A.W. are Editorial Board members of this journal, but were not involved in the peer-review process nor had access to any information regarding its peer-review.

I.B., C.K., A.G.H., K.K.H.A. and A.V. have no conflicts of interest to report.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/BLC-240048.

REFERENCES

[1] | World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report. 2018. Available from: http://dietandcancerreport.org |

[2] | Malcomson FC , et al. Adherence to the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF)/American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) Cancer Prevention Recommendations and risk of 14 lifestyle-related cancers in the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. BMC Med. (2023) ;21: (1):407. |

[3] | Solans M , et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the 2007 WCRF/AICR score in relation to cancer-related health outcomes. Ann Oncol. (2020) ;31: (3):352–68. |

[4] | van Hoogstraten LM , et al. Global trends in the epidemiology of bladder cancer: challenges for public health and clinical practice. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2023) ;20: (5):287–304. |

[5] | Westhoff E , et al. Body Mass Index, Diet-Related Factors, and Bladder Cancer Prognosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Bladder Cancer. (2018) ;4: (1):91–112. |

[6] | van Osch FH , et al. Significant Role of Lifetime Cigarette Smoking in Worsening Bladder Cancer and Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Prognosis: A Meta-Analysis. J Urol. (2016) ;195: (4 Pt 1):872–9. |

[7] | Babjuk M , et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (Ta, T1, and Carcinoma in Situ). Eur Urol. (2022) ;81: (1):75–94. |

[8] | Witjes JA , et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: summary of the 2023 guidelines. Eur Urol. (2024) ;85: (1):17–31. |

[9] | Beeren I , et al. Limited changes in lifestyle behaviours after non-muscle invasive bladder cancer diagnosis. Cancers. (2022) ;14: (4):960. |

[10] | Chung J , et al. Modifiable lifestyle behaviours impact the health-related quality of life of bladder cancer survivors. BJU Int. (2020) ;125: (6):836–42. |

[11] | Catto JW , et al. Lifestyle factors in patients with bladder cancer: a contemporary picture of tobacco smoking, electronic cigarette use, body mass index, and levels of physical activity. Eur Urol Focus. (2023) ;9: (6):974–82. |

[12] | Westhoff E , et al. Low awareness, adherence, and practice but positive attitudes regarding lifestyle recommendations among non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. Urol Oncol. (2019) ;37: (9):573. e1–573. e8. |

[13] | Bjurlin MA , Goble SM , Hollowell CM . Smoking cessation assistance for patients with bladder cancer: a national survey of American urologists. J Urol. (2010) ;184: (5):1901–6. |

[14] | Bernstein AP , et al. Tobacco Screening and Treatment during Outpatient Urology Office Visits in the United States. J Urol. (2021) ;205: (6):1755–61. |

[15] | Matulewicz RS , et al. Urologists’ Perceptions and Practices Related to Patient Smoking and Cessation: A National Assessment From the 2021 American Urological Association Census. Urology. (2023) ;180: :14–20. |

[16] | Bassett JC , et al. Knowledge of the harms of tobacco use among patients with bladder cancer. Cancer. (2014) ;120: (24):3914–22. |

[17] | Bassett JC , et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Successful Smoking Cessation in Bladder Cancer Survivors. Urology. (2021) ;153: :236–43. |

[18] | Ripping TM , et al. Insight into bladder cancer care: study protocol of a large nationwide prospective cohort study (BlaZIB). BMC Cancer. (2020) ;20: (1):455. |

[19] | de Goeij L , et al. The UroLife study: protocol for a Dutch prospective cohort on lifestyle habits in relation to non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer prognosis and health-related quality of life. BMJ Open. (2019) ;9: (10):e030396. |

[20] | Ligibel JA , et al. Oncologists’ Attitudes and Practice of Addressing Diet, Physical Activity, and Weight Management With Patients With Cancer: Findings of an ASCO Survey of the Oncology Workforce. J Oncol Pract. (2019) ;15: (6):e520–8. |

[21] | Pallin ND , et al. A Survey of Therapeutic Radiographers’ Knowledge, Practices, and Barriers in Delivering Health Behaviour Advice to Cancer Patients. J Cancer Educ. (2022) ;37: (4):890–7. |

[22] | Warren GW , et al. Addressing tobacco use in patients with cancer: a survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Oncol Pract. (2013) ;9: (5):258–62. |

[23] | Day FL , et al. Oncologist provision of smoking cessation support: A national survey of Australian medical and radiation oncologists. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. (2018) ;14: (6):431–8. |

[24] | Massoud M , et al. Provision of Lifestyle Recommendations to Cancer Patients: Results of a Nationally Representative Survey of Hematologists/Oncologists. J Cancer Educ. (2021) ;36: (4):702–9. |

[25] | Ramsey I , et al. Exercise counselling and referral in cancer care: an international scoping survey of health care practitioners’ knowledge, practices, barriers, and facilitators. Support Care Cancer. (2022) ;30: (11):9379–91. |

[26] | Williams K , et al. Health professionals’ provision of lifestyle advice in the oncology context in the United Kingdom. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2015) ;24: (4):522–30. |

[27] | Chandi J , et al. Patterns of Smoking Cessation Strategies and Perception of E-cigarette Harm Among Bladder Cancer Survivors 1. Bladder Cancer. (2024) ;10: :61–9. |

[28] | van Osch FHM , et al. The association between smoking cessation before and after diagnosis and non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer recurrence: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. (2018) ;29: (7):675–83. |

[29] | Westmaas JL , et al. Does a Recent Cancer Diagnosis Predict Smoking Cessation? An Analysis From a Large Prospective US Cohort. J Clin Oncol. (2015) ;33: (15):1647–52. |

[30] | Beeren I , et al. Limited Changes in Lifestyle Behaviours after Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Diagnosis. Cancers. (2022) ;14: (4):960. |

[31] | Winters BR , et al. Does the Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer Lead to Higher Rates of Smoking Cessation? Findings from the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey. J Urol. (2019) ;202: (2):241–6. |