Digitally deconstructing ‘straw man’ and ‘wicker man’ arguments: A software-aided pedagogy

Abstract

This article models a software-based pedagogy, targetted at undergraduates, for assisting with detection and deconstruction of straw man arguments. The pedagogy is useful particularly where the student is unfamiliar with the standpoint attacked in the argument, where the text describing the standpoint is large and where the argument is lengthy too. I use a digital text analysis tool – Sketch Engine – to help reveal and deconstruct a straw man argument which misrepresents one specific aspect of a book. I then go on to use this tool in combination with another digital text analysis tool – WMatrix – to demonstrate too how the book’s wider standpoints conflict with the argument’s framing. I thus also show the argument to be a much bigger straw man, what I refer to as a wicker man. Advantages of using the digital tools are that (i) they efficiently set the student up to judge whether or not central topics in a large text being attacked are relevant absences from the argument attacking that text; (ii) the potential for arbitrariness in judging whether or not the argument is a straw man or a wicker man is significantly reduced, making in principle for scrupulous evaluation.

1.Introduction

1.1.Orientation

This article highlights and illustrates a software-based pedagogy, aimed at undergraduates, for aiding the detection and deconstruction of straw man arguments. The pedagogy is useful especially where the student does not know (in any great depth) the standpoint attacked in the argument, where this standpoint text is large and where the argument is lengthy also. In this article, I use a digital text analysis tool – Sketch Engine – to assist in illuminating and deconstructing a straw man argument which distorts one particular aspect of a book. I then go on to use Sketch Engine in conjunction with another digital text analysis tool – WMatrix – to demonstrate also how the book’s wider standpoints jar with the argument’s framing. I thus also reveal the argument to be a much larger straw man – a wicker man.11

A pedagogical advantage of using the digital tools is that they efficiently set the student up to establish whether central topics in a large text being attacked are relevant absences from the argument attacking that text. There is also a methodological advantage to this software-assisted approach. Examination of the large text being attacked by an argument is non-arbitrary since it is steered by objectively-generated quantitative results. This, in turn, means that the potential for arbitrariness in evaluating whether or not the argument is a straw man or a wicker man is significantly reduced, making in principle for rigorous assessment.

1.2.Organisation

In the next section, I define and discuss straw man arguments and their sub-types. In Section 3, I highlight how the cohesion of an argument, how it hangs together through its vocabulary and grammar, is important to how it frames the standpoint it attacks, and important also to the critical pedagogy of this article. I also spotlight a key point of this article: an argument may only appear cohesive because of what it excludes. Revealing relevant absences from an argument can impact on its cohesive structure. In turn, this can illuminate the credibility of how it has framed the standpoint it attacks and thus whether or not the argument is a straw man.

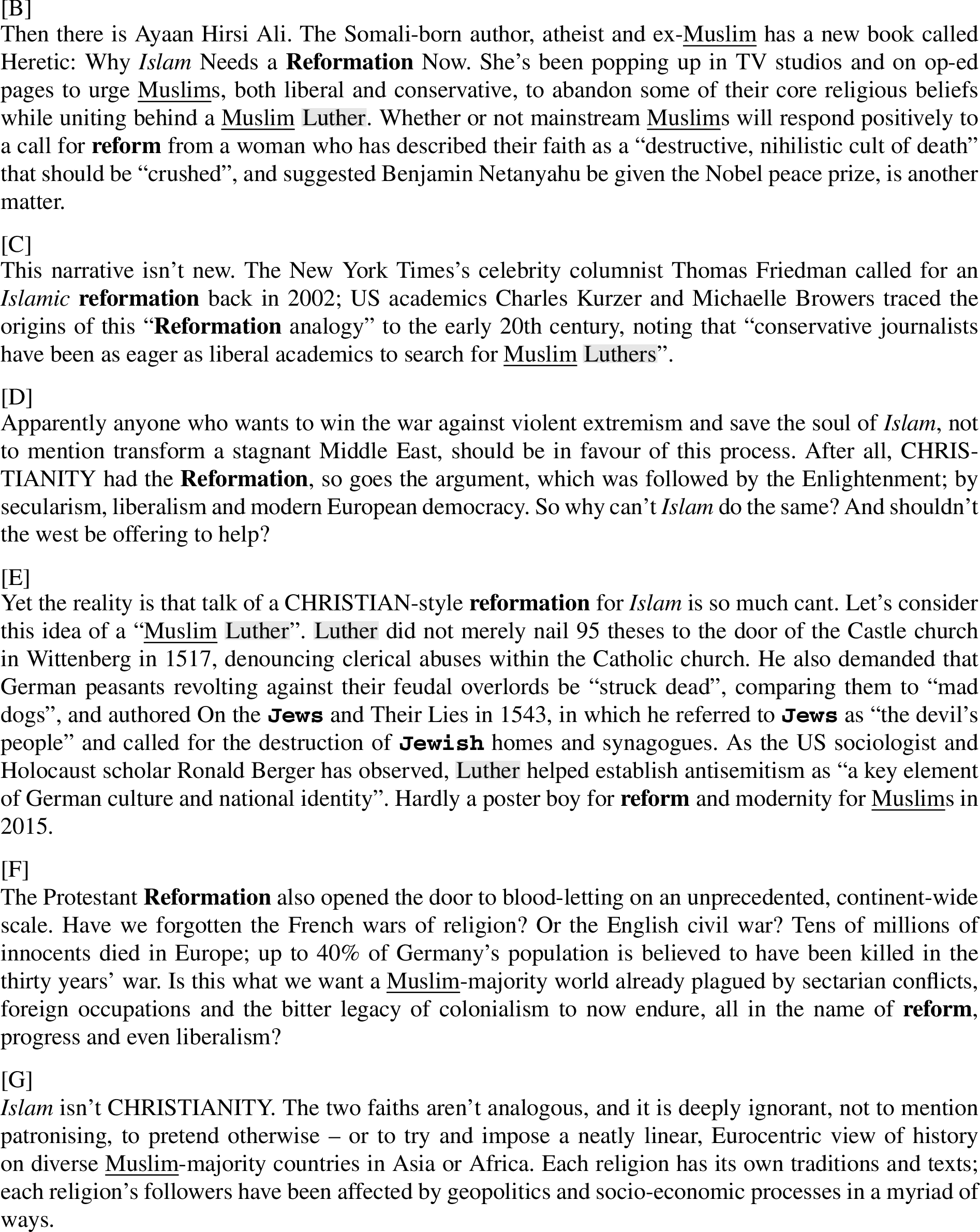

Section 4 includes the data I examine to illustrate this pedagogy. It is an argument called ‘Why Islam Doesn’t Need a Reformation’ which was written by the journalist and Muslim, Mehdi Hasan, and published on 17th May 2015. Hasan criticises a number of texts for allegedly calling for an Islamic reformation directly analogous to Luther’s Christian reformation. As part of this critique, Hasan takes issue with Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s book Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation, published a little before his argument. Heretic consists of around 70,000 words.

In the rest of the article (Sections 5–8), I model how a combination of the digital tools Sketch Engine and WMatrix can be used conveniently by undergraduates to reveal Hasan’s argument to be a straw man. Moreover, I show the deconstructive ramifications for Hasan’s arguments from major themes of Hirsi Ali’s book which he does not refer to. In so doing, I reveal Hasan’s argument to be a much bigger straw man – a wicker man – relative to Heretic.

2.Straw man arguments

2.1.Definition

I have mentioned ‘straw man’ arguments, but not yet given a definition:

‘…the technique used when an arguer ignores their opponent’s real position on an issue and sets up a weaker version of that position by misrepresentation, exaggeration, distortion or simplification.’ (Bowell and Kemp [3]: 252)22

2.2.Types of straw man

The above definition of a straw man by Bowell and Kemp can be discriminated. Talisse and Aikin [16] argue for two forms of straw man: (i) misrepresentation and (ii) weak. The first form involves a speaker or writer advancing an argument which misrepresents, in part, the standpoint they are attacking. The second is not a misrepresentation. Instead, it involves the antagonist selecting the weakest version of a protagonist’s argument, or non-central aspects of the standpoint, because they are more readily criticisable.

Aikin and Casey [1] build on the stance of Talisse and Aikin [16] by arguing for a further sub-type of straw man argument – the hollow man argument. While the misrepresentation and weak man bear some resemblance to the standpoint which is attacked in the argument, the hollow man is a complete fabrication. The proponent of the standpoint which is being attacked simply did not advance anything remotely similar to that standpoint.

2.3.Dialectical obligations, space constraints and written arguments

The dialectical obligation that straw man arguments contravene is summed up in Tindale [17, p. 22]:

As arguers we are obligated to treat our opponents fairly, and that fairness includes listening carefully to what they say, knowing their position, and treating it with some respect. In good dialectical exchanges, arguers are also encouraged to consider the strongest point of their opponents and to try and assess that. Deliberately distorting a position by conjuring up a weak caricature of it is not fulfilling that obligation; nor does it do the arguer’s own position a lot of good if the strategy is detected.

What about written arguments? The dialectical obligations of an argument to represent accurately the standpoint it attacks will depend on the written genre and the space available. For example, in a critical review of a philosophy book, such as in the New York Review of Books, which affords a few thousand words to the reviewer, one would expect the author to fulfil their dialectical obligations by giving an accurate account of the main element(s) of the book’s standpoint. For a newspaper op-ed, of around 1,000 words, where a book might be mentioned in relation to a particular line that the op-ed author is taking, then clearly (i) there are space constraints on setting out the main elements of that book; (ii) in any case, it may well be irrelevant to the argumentative goals of the op-ed author to do this if they are only concentrating on one aspect of that book. I mention this distinction between critical review and op-ed since it bears on the straw man evaluation later.

2.4.Using software to help evaluate whether or not an argument is a straw man

As Scott Aikin and Robert Talisse hold, the effectiveness of a straw man argument depends on the ‘audience’s inexperience or ignorance’ (Talisse and Aikin [16, p. 348]). It is impossible for even the most erudite to be richly knowledgeable of every single topic imaginable. Many, if not most, of us coming across an argument in the media, particularly op-ed arguments, will be ignorant, to different degrees, about the standpoint source attacked in the argument. That straw man arguments are ubiquitous compounds this problem:

‘One encounters the straw man virtually anywhere there is an argument. This is especially so in the heated exchanges about politics and religion on Cable TV talk shows, talk radio, Internet discussion forums, and newspaper op-ed pages.’ (Aikin and Casey [1, p. 87])

Students can of course go to the trouble to find out (more) about the standpoint attacked in the argument. Even if the data is voluminous because it is book length, say, their exploration is made much easier with books now in digital format. But, how do students guard against possible charges that what they focus on is merely arbitrary? The software-aided pedagogy of this article aims to go some way to addressing this state of affairs. Many of the most recurrent words and expressions in the standpoint data being attacked in an argument are likely to be indices of the main elements of that standpoint. The software that I utilise in this article can access easily these frequencies. Students can thus use this quantitative information about the standpoint to direct, non-arbitrarily, their qualitative engagement with that data. In turn, as I show, this conveniently facilitates an efficient and rigorous evaluation of whether or not the argument attacking that standpoint is a straw man.

3.Framing the standpoint attacked in the argument

3.1.An argument’s cohesion and coherence

To facilitate evaluation of whether or not an argument is a straw man, in the first place the analyst needs to know accurately how the argument has framed the standpoint it attacks. In my use of ‘framing’, I echo Robert Entman’s well-known definition:

Framing essentially involves selection and salience. To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described. Typically frames diagnose, evaluate, and prescribe…(Entman [7, p. 52])

An argument’s framing can be seen in the recurrent vocabulary that the arguer uses to describe the topic and standpoint they attack. Identifying how an argument has framed the standpoint it attacks through recurrent lexis and semantically related lexis, in effect, reveals dominant cohesion in the text of the argument. By cohesion, I mean how a text is tied together by its vocabulary. For example, in:

Mary had a little lamb. Its fleece was white as snow.

Cohesion in a text is hardly trivial. Indeed, as the linguists Ronald Carter and Walter Nash say, ‘The first requirement of any composition is that it should ‘hang together’

‘Cohesion distinguishes well-formed texts, focusing on an integrated topic, with well-signalled internal transitions [

3.2.An argument may appear cohesive/coherent because of what it excludes

In discourse analysis, cohesion is often discussed in relation to another concept – coherence. This is the experience in reading or listening that the meaning of a text is unified. Coherence is a mental property. In contrast, cohesion is a property of the text.44 Cohesion is usually necessary to ensure our experience of reading a text is coherent, certainly where the text is not short. But, other factors are required for coherence such as relevant background knowledge.

Like any text, an argument needs to be cohesive to be effective. But, what if we find out that the argument has excluded key aspects of the standpoint it attacks? Highlighting relevant absences in the argument may disrupt its cohesive structure – both at a micro- and macro-level. If an argument’s cohesion suffers, if its framing of the standpoint it attacks cracks, then there may well be repercussions for the sense we can make of it. And, if the argument loses coherence, in turn its credibility must suffer. As I will show, the critical reading strategy of this article rests on the following idea: an argument may appear cohesive on the page and coherent in our reading because of what it excludes.

3.3.Tracing the cohesive structure of the argument

An entailment of the above is that the analyst should seek to understand an argument’s cohesive structure in some detail. That is to say, an analyst cannot deconstruct convincingly how an argument has framed the standpoint it attacks unless they have first traced this framing accurately. Systematically tracing recurrent lexical cohesive patterns of an argument makes for a precise, rigorous and targeted evaluation of potential straw man status.

I move on now to the data I use to model this software-aided pedagogy for helping undergraduates to assess rigorously whether or not an argument is a straw man.

4.Data

4.1.Orientation

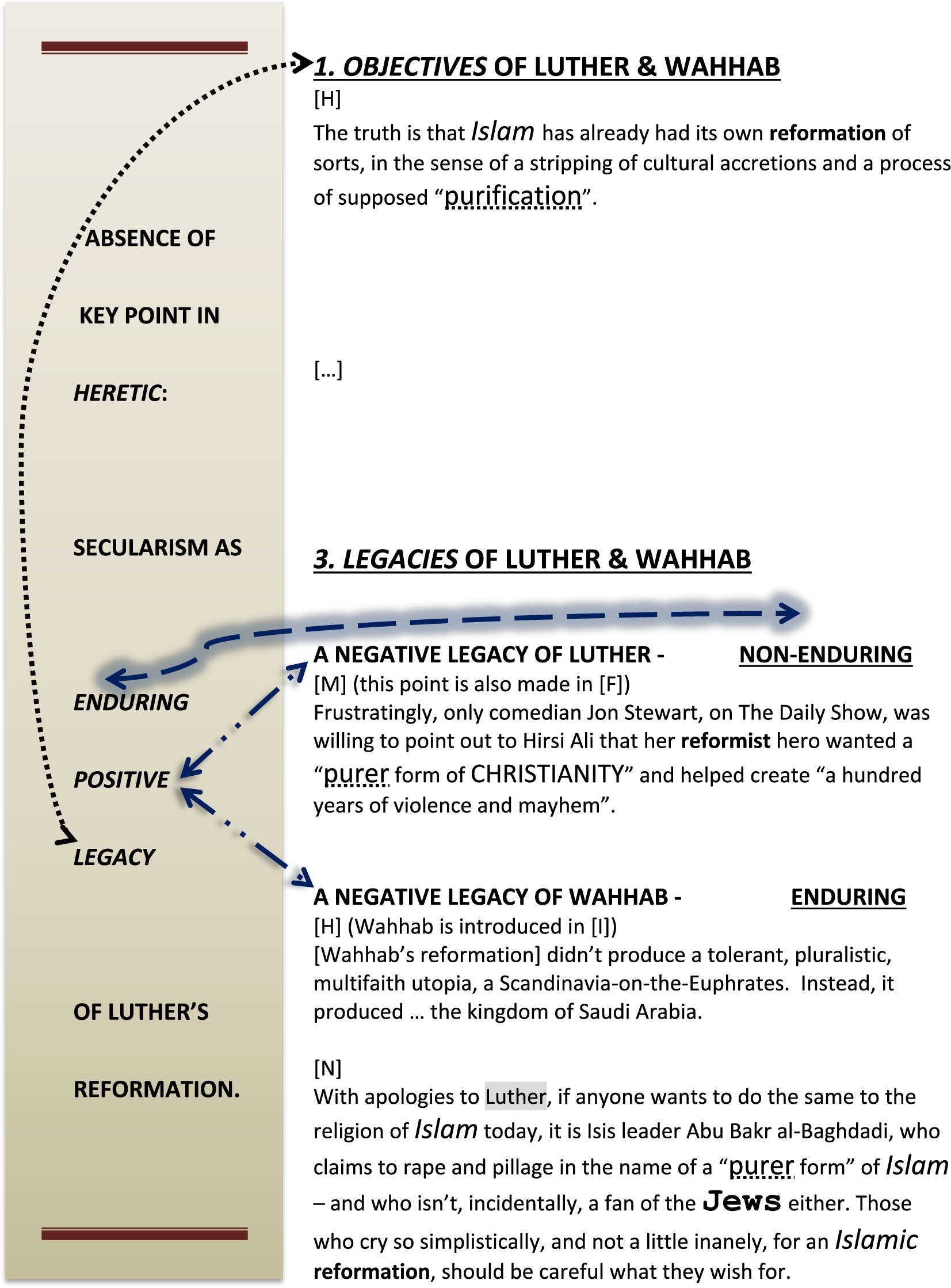

To model the pedagogy, I use an argument called ‘Why Islam Doesn’t Need a Reformation’. The argument was written by the journalist and Muslim, Mehdi Hasan. It is an op-ed of 1,169 words which was published on 17th May 2015 in The Guardian newspaper. Figure 2 contains Hasan’s argument with my annotations. But, if the reader would prefer to look at an unannotated version first, I have footnoted the Guardian link.55 In his op-ed, Hasan takes issue with a number of texts which have allegedly called for a ‘Muslim Martin Luther(s)’ to spark a reformation of Islam directly analogous to Christianity’s reformation. Hasan’s article hyperlinks to these texts, as can be seen in Fig. 1. His opening paragraphs, together with the macro-framing of heading, subheading, content of photograph under the heading, and highlighted quotation from the op-ed, can also be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Initial paragraphs of Hasan’s op-ed showing macro framing. Copyright Guardian News & Media Ltd 2018.

In his second paragraph, Hasan flags a book by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation, which was published a little before Hasan’s argument. In contrast to Hasan, Hirsi Ali is an atheist and ex-Muslim. Heretic consists of 69,546 words, which includes an appendix of 3,284 words discussing dissident and reformist Muslims.66

4.2.Using a digital tool to help ascertain an argument’s framing

4.2.1.Systematically identifying an argument’s framing

In later sections, I will reveal problems for Hasan’s framing of the hyperlinked texts and Heretic. Before I do so, I need to identify this framing or, in linguistic terms, its cohesive structure which, in turn, contributes to its coherence. Echoing earlier, careful and comprehensive tracing of dominant cohesion enables the student to appreciate systematically, rather than impressionistically, how an argument repeatedly frames the standpoint it attacks. However, this identification procedure becomes laborious, and potentially error-prone, once the text consists of hundreds of words. These issues can be attenuated considerably by using a digital text analysis tool. Tracing dominant cohesion across the text with the help of such a tool reduces the prospect that students miss where an argument has framed the standpoint it attacks. In turn, accurate description of an argument’s framing helps ensure the credibility of any subsequent deconstruction of it.

4.2.2.Using the lemma list function in Sketch Engine

To assist me with accurate identification of Hasan’s framing, I loaded up his argument to the corpus linguistic package, Sketch Engine.77 Corpus linguistics is the software-based, quantitative investigation of a collection of electronic texts; such a collection is referred to as a ‘corpus’.88 Sketch Engine was designed for working with corpora (the plural of ‘corpus’), but there is no reason why it cannot be used on single texts, which is how I use this software in this article.

Plain text files are the default format for Sketch Engine. I copied and pasted Hasan’s argument from the online Guardian into Notepad – a plain text editor for Windows – and saved the file. I loaded up Hasan’s argument to Sketch Engine and generated a ‘lemma list’. Many words have different word forms, e.g., ‘go’, ‘goes’, ‘going’, ‘gone’, ‘went’ are all part of the same word family. The general word which encompasses different word forms – morphologically equivalent to the simplest word form – is referred to by linguists as the lemma. So go is the lemma for the above word forms.99 Generating lemmas from a large body of data is useful. Aggregating different morphologically related word forms under one label provides a convenient birds-eye view on lexical content. For my specific purposes here, this helps establish a keener sense of lexical repetition, and thus lexical cohesion, across an argument. To help achieve the most effective birds-eye view on the lexical content of Hasan’s argument, I treated all data as lower-case. And since, in trying to access lexical content, it is helpful to have ready access to lexical words without the ‘noise’ of grammatical words (e.g. ‘and’, ‘in’, ‘she’, ‘the’), I filtered out the latter by using a stoplist.1010 Table 1 shows all lexical lemmas in Hasan’s argument whose combined word forms occur at least five times.

Table 1

Lexical lemma list for Mehdi Hasan’s argument ⩾ 5

| RANK | FREQ. | LEMMA | WORD FORM | FREQ. | WORD FORM | FREQ. |

| 1 | 20 | muslim | muslim | 14 | muslims | 6 |

| 2 | 19 | islam | islam | 15 | islamic | 4 |

| 3 | 14 | reformation | reformation | 14 | ||

| 4 | 10 | luther | Luther | 9 | Luthers | 1 |

| 5 | 6 | reform | reform | 5 | reforms | 1 |

| 6= | 5 | christianity | christianity | 4 | christian | 1 |

| 6= | 5 | jew | jews | 4 | jewish | 1 |

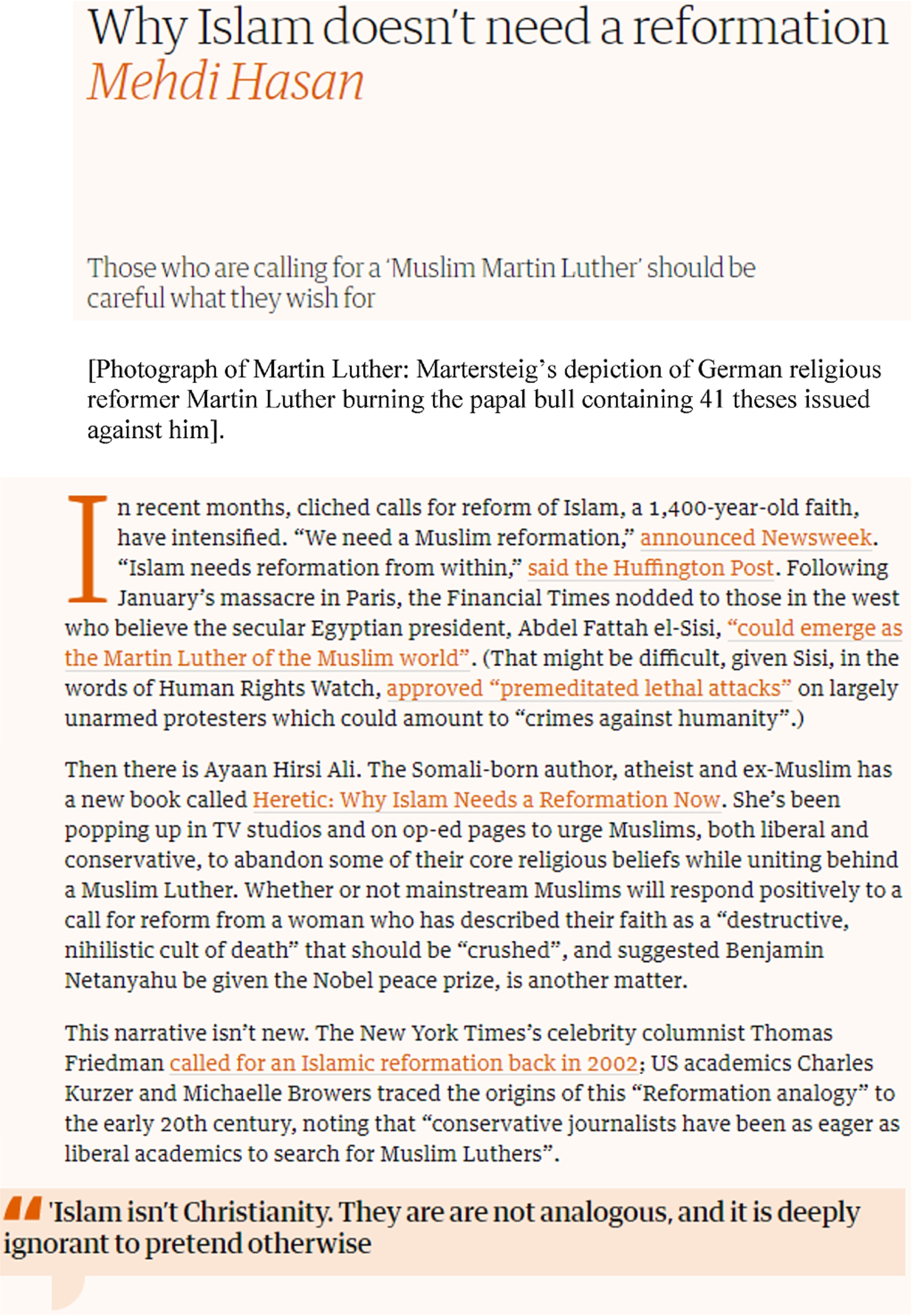

Fig. 2.

Hasan’s argument annotated for major cohesive links. Copyright Guardian News & Media Ltd 2018.

Fig. 2.

(Continued.)

Fig. 2.

(Continued.)

Fig. 2.

(Continued.)

4.2.3.Tracing dominant patterns of lexical cohesion in Hasan’s argument

Figure 2 shows annotation of major lexical cohesive links across the argument based on recurrent lemmas in Table 1. Any text of reasonable length is saturated with cohesive devices. I choose a threshold of five lexical word forms (see Table 1) for a set of lexical cohesive links to be detailed in Fig. 2 since this number enables me to appreciate precisely dominant ways in which Hasan frames Hirsi Ali’s argument while leaving Fig. 2 still readable.1111 In Fig. 2, I throw into relief dominant cohesive structure in Hasan’s argument with the following formatting:

CHRISTIANITY: capitals

Islam: italics

Jew: courier new font bold

Muslim: underlining

: highlighter

: highlighterreformation/reform: bold

5.Deconstruction of Hasan’s straw man argument

5.1.Hasan’s strawmanning of the texts hyperlinked in the first paragraph

Figure 2 throws systematically into relief Hasan’s framing, in paragraphs [A], [B] and [C], of a set of texts which he hyperlinks to. As before, for Hasan, these texts are calling for reform of Islam along the lines of the Protestant Reformation and to be led by ‘Muslim Luther(s)’. The photograph of Martin Luther emphasises this framing. However, it does not take us long to be suspicious of such framing. The first text of the three which are hyperlinked in paragraph [A] is ‘We Need a Muslim Reformation’, written by Naser Khader, a senior fellow of the Hudson Institute (Newsweek, 26 March 2015). Being a short text of 614 words, it is relatively easy to see that Khader does not even mention Luther. In the second link, ‘Islam Needs Reformation from Within’ by Raza Rumi (Huffington Post), there is no mention of Luther either. This is another reasonably short text – 1025 words – and so again the absence of Luther is fairly easy to notice, especially with a web browser word search facility.

The third hyperlink is to another short text (715 words) written by Roula Khalaf (Financial Times January 14th 2015). Hasan frames this text as follows:

[A]

[…]

Following January’s massacre in Paris, the Financial Times nodded to those in the west who believe the secular Egyptian president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, “could emerge as the Martin Luther of the Muslim world”. (That might be difficult, given Sisi, in the words of Human Rights Watch, approved “premeditated lethal attacks” on largely unarmed protesters which could amount to “crimes against humanity”.)

The former general [Sisi] who led the 2013 coup against an elected government of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood has since waged a relentless and bloody campaign of repression against the group and cracked down on the media. He is an unlikely leader of a reformation.

In paragraph [C], Hasan claims that The New York Times’s celebrity columnist Thomas Friedman called for an Islamic reformation back in 2002. Clicking on the hyperlink to his column in the New York Times, the reader comes to another short text – 786 words – where they find out that, certainly, Friedman endorses Islamic reform. But the reader also discovers that Friedman has centred his article on the then political unrest in Iran as a:

promising trend in the Muslim world. It is a combination of Martin Luther and Tiananmen Square – a drive for an Islamic reformation combined with a spontaneous student-led democracy movement.

Mr. Aghajari’s speech […] began by noting that just as “the Protestant movement wanted to rescue Christianity from the clergy and the church hierarchy,” so Muslims must do something similar today. The Muslim clergymen who have come to dominate their faith, he said, were never meant to have a monopoly on religious thinking or be allowed to ban any new interpretations in light of modernity.

5.2.Hasan’s strawmanning of Hirsi Ali’s ‘Heretic’

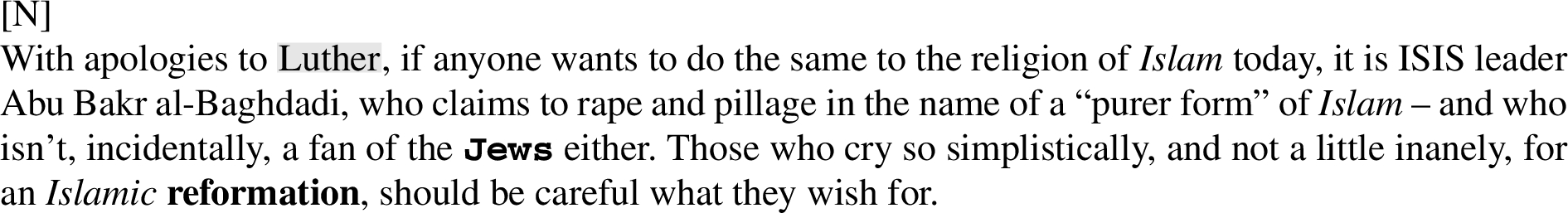

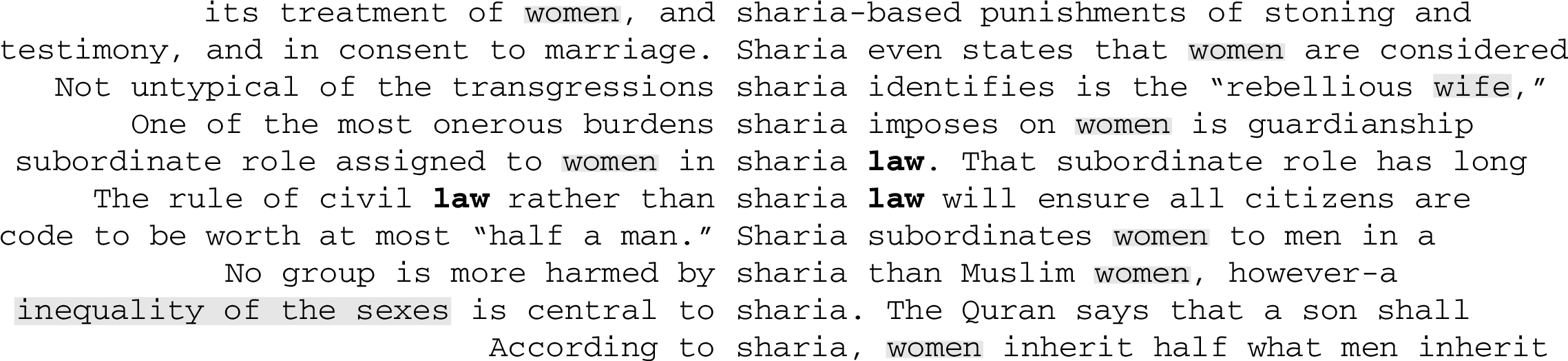

Fig. 3.

Concordance for all 12 instances of ‘Luther’ in Heretic.

In paragraph [B], Hasan criticises Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s book Heretic. As a book of 70K words, this is far larger than the aforementioned hyperlinked texts. Using the search function in the Kindle app, I discovered that Heretic contains 12 instances of ‘Luther’. Checking the linguistic contexts for these 12 instances, I found that at no point does Hirsi Ali call for a reformation directly analogous to Luther’s. In fact, she says the following (first line of Fig. 3):

The Lesson of Luther. Will a Muslim Reformation look exactly like the Christian one? No, of course not. (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 57])

When I first conceived of writing a book about a Reformation of Islam, I imagined it as a novel. Entitled The Reformer, it was going to tell the story of a charismatic young imam in London who would emerge as a modern-day Muslim Luther. I abandoned the idea because such a book was bound to be dismissed as fanciful. (Hirsi Ali [10, pp. 224–225])

Another advantage of Sketch Engine over Kindle is that it automatically calculates the word frequency of Heretic at 69, 546 words. This knowledge enables me to make some useful contrastive percentage calculations of how frequent ‘Luther’ is in Hasan’s argument and Heretic. ‘Luther’ is the 4th most common lexical word in Hasan’s argument, occurring 10 times (0.9% of the text). This contrasts sharply with its frequency in Heretic; ‘Luther’ at 12 instances is the 527th most common lexical word in Heretic (0.02% of the text).1414 ‘Luther’ can hardly then be said to be quantitatively significant in Hirsi Ali’s book. Indeed, the concentration of ‘Luther’ in Hasan’s argument is 45 times higher than the concentration of ‘Luther’ in Heretic.

To conclude, since Hirsi Ali does not call for an Islamic reformation, directly analogous to the Christian reformation which is to be led by a Muslim Martin Luther(s), and with ‘Luther’ being anyway a peripheral figure in Heretic, Hasan produces a straw man. He misrepresents, thus, Hirsi Ali’s position in paragraph [B] when he says:

[B]

Then there is Ayaan Hirsi Ali. The Somali-born author, atheist and ex-Muslim has a new book called Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now. She’s been popping up in TV studios and on op-ed pages to urge Muslims, both liberal and conservative, to abandon some of their core religious beliefs while uniting behind a Muslim Luther.

[G]

Islam isn’t CHRISTIANITY. The two faiths aren’t analogous…

[M]

[…]

Frustratingly, only comedian Jon Stewart, on The Daily Show, was willing to point out to Hirsi Ali that her reformist hero [Martin Luther] wanted a “purer form of CHRISTIANITY” and helped create “a hundred years of violence and mayhem”.

5.3.Summing up deconstruction of Hasan’s straw man argument

All the authors that Hasan hyperlinks to either report calls for reform of Islam or call for it themselves. But none of them call for reform to be led by a Muslim Martin Luther(s) as though an Islamic reformation would mirror the Christian reformation. Hasan has thus strawmanned these authors. Specifically, these are misrepresentation straw men (Section 2.2). In fact, the only reference to ‘Islamic Protestantism’ derives from the Muslim academic Hashem Aghajari, who is cited in Friedman’s article.

Lastly, let me comment on Hasan’s reference, in paragraph [C], to US academics ‘Charles Kurzer (sic) and Michaelle Browers’ noting that “conservative journalists have been as eager as liberal academics to search for Muslim Luthers”. This is an accurate quotation from their text (Browers and Kurzman [4, p. 6]). Hasan is using this reference as support for his claim that the call for a Muslim Luther is not new. Yet, as I have shown, none of the other authors that he has flagged explicitly call for a Muslim Luther. So the reference to Browers and Kurzman [4] is being used as backing for a position for which there is no evidence in the other texts Hasan cites.

6.What if Hasan’s text is also a wicker man argument?

6.1.Orientation

My deconstruction of Hasan’s strawmanning, in Section 5, related specifically to the framing of his argument – once again that the authors he cites had allegedly called for an Islamic reformation directly analogous to the Christian reformation and to be led by a Muslim Luther(s). In deciding whether or not this was a fair representation of Heretic’s stance, all I really needed to do was target ‘Luther’ in Heretic. In doing so, I discovered that ‘Luther’ is actually not of major concern to Hirsi Ali. It follows, thus, that I have barely explored her 70,000 word book. But then again there was no real need to do this in relation to Hasan’s dialectical obligations. That is to say, given the specificity of his argument, and the fact that Hasan’s text is an op-ed with limited space, he did not criticise other aspects of Heretic. In turn, this meant that he was not obligated to set out Heretic’s major standpoints.

With easy-to-use data-mining tools to hand, it is straightforward to discover non-arbitrarily the main topics, words and phrases of Heretic as indices of its main standpoints and thus conveniently not pass up an opportunity to engage more fully with Heretic. Having done so, I can then explore rigorously whether or not its main standpoints have further negative implications for the stability of Hasan’s framing. That is to say, I may discover that Hasan’s argument is potentially a much larger straw man – a wicker man.1515

Echoing above, one might object to this wider exploration by saying that, since it exceeds the specific goals of Hasan’s argument, it is not dialectically justified. Yet, there is some justification for exploring the possibility that Hasan’s argument is a larger straw man vis-à-vis Heretic. This is because, in paragraph [K], Hasan goes beyond his criticism of the alleged call for Muslim Martin Luthers by conceding that reforms are necessary:

[K]

Don’t get me wrong. Reforms are of course needed across the crisis-ridden Muslim-majority world: political, socio-economic and, yes, religious too. […]

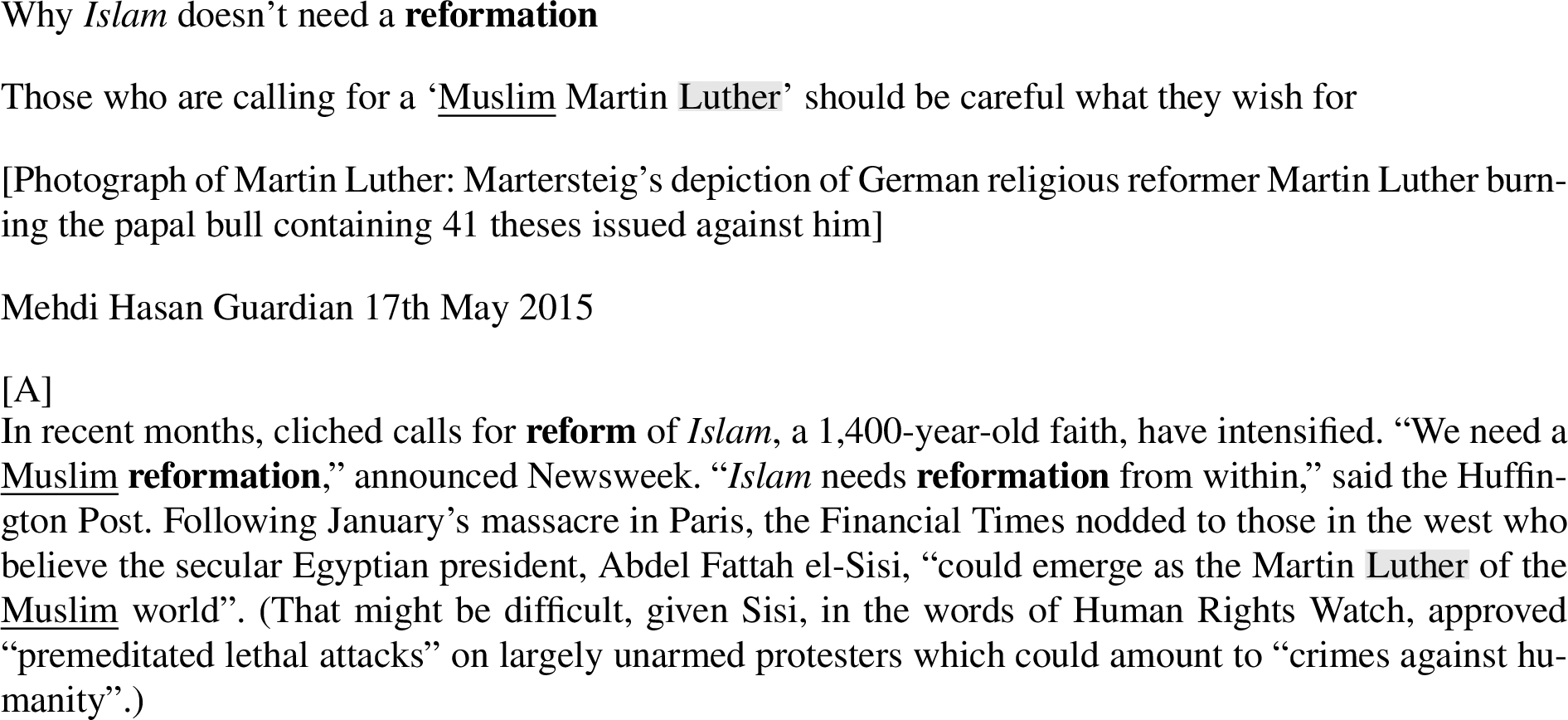

6.2.Macrostructure in Hasan’s framing

Guided by the micro-cohesive structure in Fig. 2, I summarise Hasan’s argument beyond [A] to [C] by indicating how he has macro-constructed three parallels across paragraphs [E], [F], [H], [I], [J], [M] and [N]. These parallels link Luther and Ibn Abdul Wahhab, who produced a puritanical, fundamentalist form of Sunni Islam in the 18th century (‘Wahhabism’), which is practised in Saudi Arabia to this day. These parallels are as follows:

1. Both Luther and Wahhab had similar reformist objectives in seeking purification of Christianity and Islam respectively;

2. Both Luther and Wahhab were anti-Semitic. ISIS1616 (with its roots in Wahhabism) is also anti-Semitic;

3. Both Luther’s and Wahhab’s reforms led to bloodshed and thus negative legacies.

Fig. 4.

Macro- and micro-cohesive structure in Hasan’s argument between [E] and [N] which is relevant to Heretic.

![Macro- and micro-cohesive structure in Hasan’s argument between [E] and [N] which is relevant to Heretic.](https://content.iospress.com:443/media/aac/2018/9-3/aac-9-3-aac040/aac-9-aac040-g007.jpg)

6.3.WMatrix

6.3.1.Semantic domains

Aside from using Sketch Engine again (see Section 6.6), the corpus linguistic software tool that I mainly employ to explore the possibility of Hasan’s argument being a wicker man is WMatrix [14].1717 A web-based tool, WMatrix has a number of functions. The one I use for this article utilises WMatrix’s capacity for analysing ‘semantic domains’. WMatrix automatically groups semantically related words in a text or corpus under a larger semantic category. So, for example, WMatrix groups the words, ‘tank’, ‘military’, ‘soldier’ under the larger category, or ‘semantic domain’, WARFARE. WMatrix can do this because it has been programmed to group lexical words under larger semantic categories in accordance with an in-built lexicon. This is a useful function since it helps the analyst to appreciate the most frequent topics in a large text.

6.3.2.Key semantic domain analysis and data contrast

While knowing the most frequent topics in a text is useful, we need to go one step beyond this to augment data mining rigour. This is because while a semantic domain might be frequent in a text (or corpus), it does not necessarily follow that it is being used any more frequently than normal. To find out if a semantic domain in a text is unusually frequent, we can compare its frequency with the same in a large corpus of texts which we treat as a norm of the language. The latter is known as a ‘reference corpus’ and needs to be large enough so that we can assume it is a reasonably representative snapshot of the language. It also needs to contain a balance of common genres (e.g., conversation, news) if it is to be a credible snapshot.

For the identification of topics in a large text, the human mind is far more subtle and discerning than a software tool, such as WMatrix, which generates semantic domains algorithmically. Humans minds, however, will differ in what they regard as key topics in a book. Moreover, human identification of topics in a large text of 70,000 words can be onerous and, to do this consistently, arduous. A better research practice would use other human identifiers so as to facilitate inter-coder consistency and reliability. This is very labour intensive for an undergraduate pedagogy though. The advantage of the preset lexicon that WMatrix uses is that it avoids variability, laboriousness and inconsistency. Yet WMatrix still carries the disadvantage that it may isolate topics that a team of human identifiers would disagree with. This is why it is important that use of WMatrix always involves comparison and contrast between two (or more) datasets. That is to say, one cannot use WMatrix to provide an absolute identification of topics in a text or corpus. The advantages of WMatrix come into play when it is used relatively.

6.3.3.How I use WMatrix

Below I employ WMatrix to find, rigorously, key semantic domains in both Heretic and Hasan’s argument. This enables me to see very clearly what statistically unusual topics of Hirsi Ali’s book are absent from Hasan’s argument. In turn, this procedure conveniently, efficiently and scrupulously sets me up to judge whether or not there are relevant topics absent from Hasan’s argument which may have wider ramifications for the credibility of its framing than what I highlighted in Section 5.

Since Heretic was published in the USA, for my analyses below I use the American English 2006 (AmE06) reference corpus of 1 million words (see Potts and Baker [13]).1818 This is the most recent American English reference corpus that WMatrix uses. AmE06 has been tagged for semantic domains. This makes it possible to ascertain which semantic fields in Heretic are statistically frequent with regard to AmE06. These are known as key semantic domains. The ‘keyness’ of a semantic domain in a text (or corpus) is calculated using the log likelihood metric. A log likelihood of 7 or over indicates statistical significance (

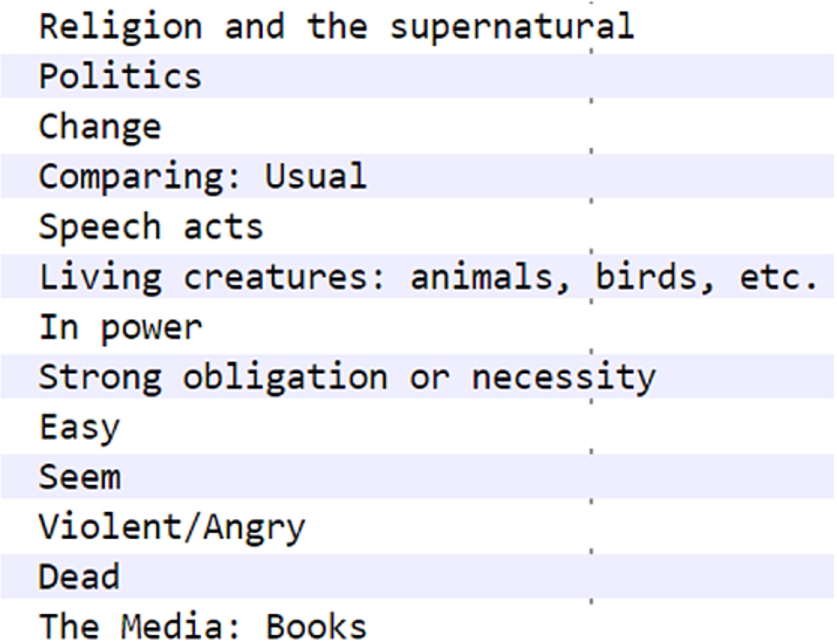

6.4.Top statistically significant semantic domains in Heretic absent from Hasan’s argument

Table 2 shows the top 10 key semantic domains for Heretic; Table 3 shows all the key semantic domains for Hasan’s argument. As the reader can see, ‘Law and Order’ and ‘People: Female’ feature amongst the top ten key semantic domains in Heretic. These semantic domains are absent from Hasan’s argument, not just from the key semantic domains in Table 3. While it is an analyst’s subjective choice which key semantic domains to zoom in on, this is not arbitrary zooming, all the same, since all the domains in these tables are statistically significant.

Table 2

Top 10 key semantic domains for Heretic

|

Table 3

All key semantic domains for Hasan’s argument

|

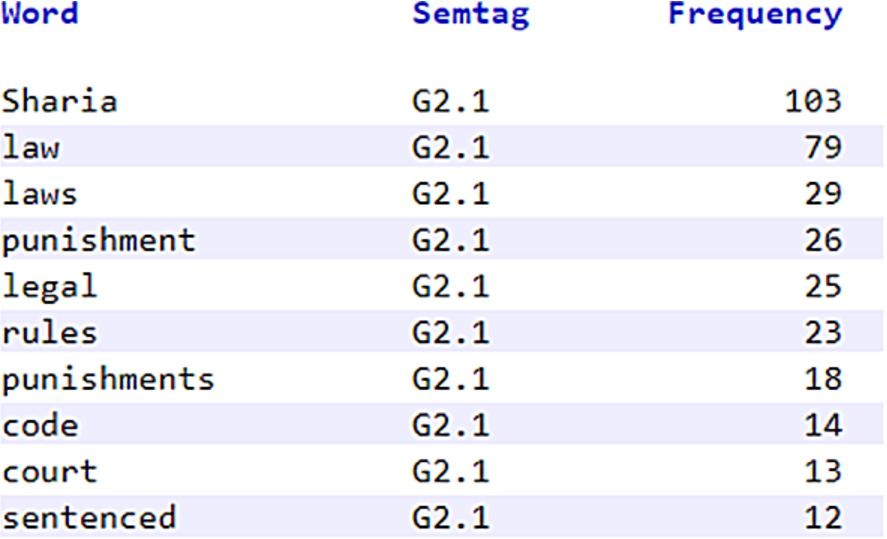

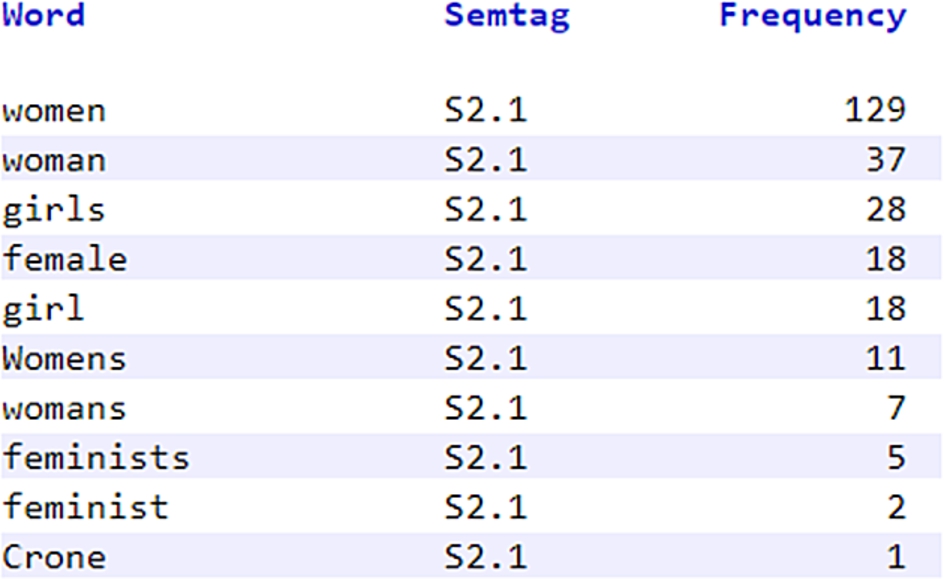

WMatrix can reveal all words under a particular semantic domain. Table 4 shows the most frequent words under ‘Law and Order’ in Heretic. Table 5 shows the most frequent words under ‘People: Female’ in the same.

Table 4

Top 10 words under the key semantic domain ‘Law and Order’ in Heretic

|

Table 5

Top 10 words under the key semantic domain ‘People: Female’ in Heretic

|

By analysing the co-texts of ‘sharia’ and ‘law’ – the most frequent words in Table 4 – we see repeatedly Hirsi Ali arguing that law and religion must be separated in Islam. For example, Hirsi Ali exhorts the following:

‘Shackle Sharia and end its supremacy over secular law’. (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 74])

In October 1517, a somewhat obscure but very obstinate monk in the Saxon town of Wittenberg wrote ninety-five theses decrying the Church’s practice of selling indulgences for salvation. His name was Martin Luther and his words helped trigger both a theological and a political revolution.

[

The upshot was a huge upheaval. [

[…]

In short, the liberation of the individual conscience from hierarchical and priestly authority opened up space for critical thinking in every field of human activity.

Centuries later, Islam has had no comparable awakening. (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 58])

To be clear, secularism was not one of Luther’s theses. It was an unforeseen legacy of the Protestant Reformation. So when Hirsi Ali draws analogy with the Protestant Reformation, it is with its ultimate enduring legacy – secularism and critical thinking. This is a positive legacy for Hirsi Ali.

6.5.Frequent collocations in Heretic absent from Hasan’s argument

There are 103 instances of ‘Sharia’ in Heretic (see Table 4). There are 129 instances of ‘women’ (Table 5). Figure 5 is a randomised sample, using Sketch Engine, of ten instances of ‘Sharia’ which show how this word collocates with ‘women’ in Heretic. The concordance in Fig. 5 reflects a more specific reformist standpoint for Hirsi Ali: Sharia law, based on the Quran, requires fundamental reform to furnish women greater rights.

Fig. 5.

10 randomly generated concordance lines for ‘sharia’ from Heretic highlighting the collocates, ‘law’ and ‘women’.

Further exploration, in Heretic, of all instances of ‘sharia’, ‘law’ and ‘women’, together with their collocates, bears this insight out. For Hirsi Ali, it is by separating law and religion, and thus instituting secularism, that women’s rights can be augmented in Muslim-majority countries.

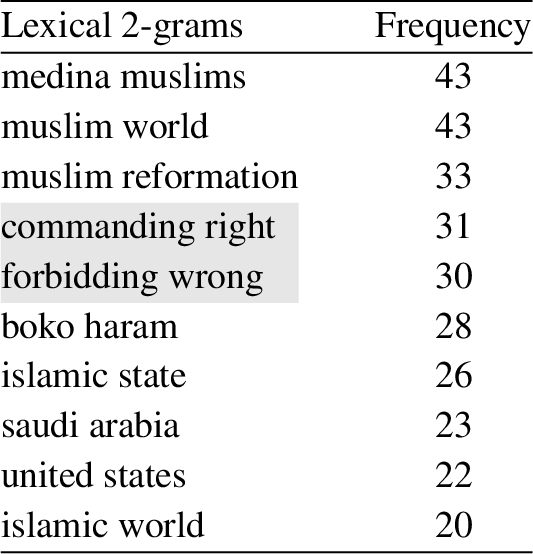

6.6.Most common 2-grams in Heretic absent from Hasan’s argument

One limitation of WMatrix is that it is restricted, in the main, in its key semantic domain function to the analysis of single words. Since meaning is commonly conveyed through collocation, it also makes sense to explore collocation differences between Heretic and Hasan’s argument. This can be done using the n-gram analysis function of Sketch Engine. An ‘n-gram’, in corpus linguistics, is a regularly repeated string of words. n refers to the number of words in the string and ‘gram’ is equivalent to word. For instance, the string ‘on the’ is a 2-gram. As this example illustrates, n-grams do not necessarily coincide with a grammatically complete unit. Table 6 shows the ten most frequent lexical 2-grams in Heretic generated via Sketch Engine.

The fourth and fifth most frequent 2-grams in Table 6 are ‘commanding right’ and ‘forbidding wrong’. Neither of these 2-grams is mentioned in Hasan’s argument. As before, the user can click on individual results in Sketch Engine to generate concordances which enable them to see how these n-grams are being used. In Heretic, Hirsi Ali argues that Sharia law is both taught rigorously to the child (‘commanding right’) and enforced by strictly intervening in behaviour which contravenes Sharia (‘forbidding wrong’). She alleges that ‘commanding right and forbidding wrong’ are practices of social control in Islam. Moreover, since these forms of control contribute to a sustaining of unequal relations between women and men in Islamic societies, she contends that they require comprehensive reform. For example, Hirsi Ali claims the following:

Women and men have very specified roles in Islamic society. It is spelled out exactly how each sex should act. And a man has an unequivocal right to command a woman, even if that woman is purportedly his teacher. (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 154])

6.7.Summary

From these data minings, it is clear that a central standpoint in Hirsi Ali’s Heretic is that Sharia – the law and its enforcement – requires root and branch reform, especially so that women’s rights may be radically augmented. A key way that this can be implemented is by ‘shackling Sharia’ and instituting secularism into Islamic societies where it does not yet exist. For Hirsi Ali, secularism is a positive ultimate legacy of the Christian reformation.

Table 6

Top 10 lexical 2-grams in Heretic

To emphasise again, Hasan is not dialectically obligated to engage with these central standpoints of Heretic since the focus of his argument is criticising the alleged calls for a Muslim Luther to lead an Islamic reformation directly analogous to the Christian reformation. Yet as I have also stated, Hasan accedes to the need for socio-economic, political and religious reforms in Islam. And as I previously contended, this licences the following experiment: importing into Hasan’s argument key reformist points of Heretic – which self-evidently fall under the broad categories of socio-economic, political and religious reform – to explore whether or not they lead to further deconstruction in Hasan’s text. This is indeed what happens. In Sections 7 and 8, I reveal that Hasan’s argument is a much bigger straw man – a wicker man – vis-à-vis Heretic. In Section 7, I reveal instability in Fig. 4.

7.Deconstruction of Hasan’s wicker man argument I

7.1.Deconstructing parallel 1: Objectives of Luther and Wahhab

Hirsi Ali’s stress is on a legacy of Luther’s reformation – secularism. So, when Hasan parallels Wahhab’s and Luther’s objectives in [H], his argument veers from Hirsi Ali’s focus. This tension is indicated in Fig. 6 with the following double-headed dotted arrow:

7.2.Deconstructing parallel 3: Legacy of Luther and Wahhab

7.2.1.Negative legacy of Luther and Wahhab (Hasan) vs positive legacy of Luther (Hirsi Ali)

When Hasan does parallel Luther’s and Wahhab’s legacies in [H], [M], [N], he would thus seem to be on relevant ground. That is to say, Hasan’s corresponding of the religious wars in Europe following the Reformation (a legacy of Luther) with the ultraviolence of ISIS (a legacy of Wahhab) would seem to be a legitimate move. However, the religious wars of the Reformation are not the only legacy of Luther. Hirsi Ali’s focus on secularism is what she perceives as a positive legacy of the Reformation when Hasan highlights a negative legacy of same. This tension is indicated in Fig. 6 with the following double-headed arrow:

7.2.2.Non-enduring legacy of Luther vs enduring legacy of Wahhab

The ensuing religious wars in Europe ended centuries ago. There is a tension, then, in Hasan paralleling a non-enduring legacy of Luther with an enduring legacy of Wahhab. A like-for-like paralleling would instead be between the enduring legacy of Wahhab and the enduring secularist unforeseen legacy of Luther’s reformation. Bringing the latter’s absence alongside Hasan’s argument, however, problematises one of Wahhab’s enduring legacies – (at the time that Hasan’s text was published) the lack of female equality in non-secular Saudi Arabia/ISIS. This tension is indicated in Fig. 6 with the following double-headed arrow:

To conclude: by importing, alongside Hasan’s argument from Fig. 4, a central standpoint in Heretic that secularism is a positive and enduring legacy of the Protestant Reformation, the framing of Hasan’s text in parallels 1 and 3 is deconstructed.

To conclude: by importing, alongside Hasan’s argument from Fig. 4, a central standpoint in Heretic that secularism is a positive and enduring legacy of the Protestant Reformation, the framing of Hasan’s text in parallels 1 and 3 is deconstructed.

7.3.Deconstructing parallel 2 in Fig. 4

I have deconstructed parallels 1 and 3 in Fig. 4. What about parallel 2? When Hasan draws attention to Luther’s anti-Semitism, is this relevant vis-à-vis Heretic? By this I mean, does Hirsi Ali make Luther’s moral character an important component of her stance? As before, all 12 instances can be seen in the concordance of Fig. 3. In none of these mentions does Hirsi Ali appeal to Luther’s moral character which could, in turn, legitimate a relevant response that she has omitted a key moral deficit – his anti-Semitism. To conclude, since Hirsi Ali does not make Luther’s moral character central to her argument, Hasan’s fixing on Luther’s anti-Semitism, at least vis-à-vis Heretic, lacks immediate relevance.

8.Deconstruction of Hasan’s wicker man argument II: Ascertaining recurrent collocates of ‘Muslim(s)’ in Heretic which are absent from Hasan’s argument

8.1.Collocates as absences

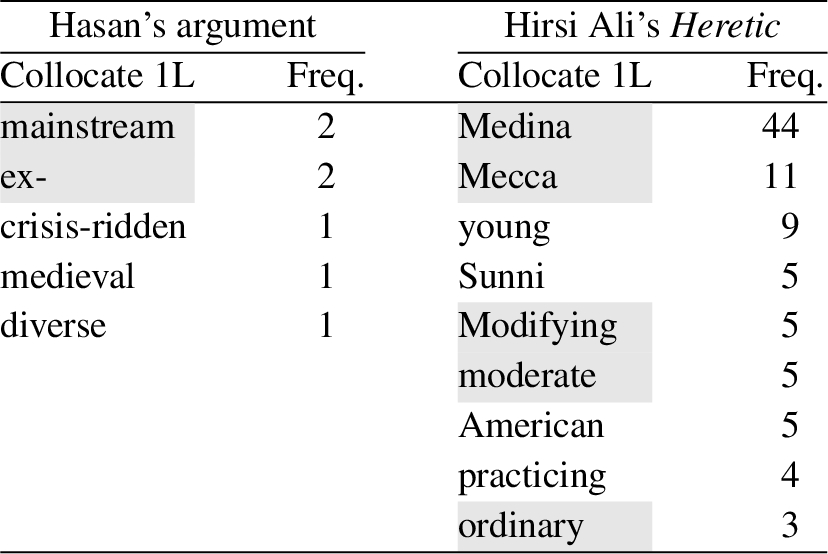

It is possible that an argument uses the same categories as the standpoint text that it attacks, yet does not use the same collocates to modify these categories. Below I perform a contrastive collocate analysis of Heretic and Hasan’s argument. I focus on the lexical lemma muslim since, at 20 instances, this is the most common in Hasan’s argument (see Table 1).

8.2.Categorisation of Muslims in Heretic I: ‘Mecca’ Muslims and ‘Medina Muslims’

I used Sketch Engine to calculate the most frequent collocates for muslim in both Heretic and Hasan’s argument. I looked for collocates one place to the left (1L) of muslim, since that is where noun modification commonly occurs. Because I am interested in distinct differences in collocate framing, I deleted collocates which were common to Heretic and Hasan’s argument. The results can be seen in Table 7. It is clear that there are differences in the collocates of muslim used by Hasan and Hirsi Ali. In Table 7, I have highlighted the collocate differences that I will discuss below. I choose these collocates since they classify contemporary Muslims broadly, not just in terms of their particular Islamic denomination.

Table 7

Lexical collocates of muslim (1L) in Heretic and Hasan’s argument; collocates of muslim common to both texts have been removed

Hirsi Ali employs ‘Mecca’/‘moderate’, ‘Medina’ and ‘Modifying’ to categorise different broad types of Muslim.2222 She uses ‘Mecca’ and ‘moderate’ interchangeably to describe conservative Muslims. They may be patriarchal, and may not embrace gay rights, but all the same do not support nor engage in violence – the vast majority of Muslims. The reason she uses ‘Mecca’ as a classifier here is to reflect Mohammed’s peaceful attitude to converting non-Muslims to Islam when he lived in Mecca. In contrast, she refers to ‘Medina Muslims’ as those who resort to violence such as ISIS, Al Qaeda and Boko Harram. The reason she chooses ‘Medina’ as a modifier is to reflect Mohammed’s martial turn when he moved to Medina.

8.3.Categorisation of Muslims in Heretic II: ‘Modifying’ Muslims

The final category of Muslim that Hirsi Ali uses is ‘Modifying’. These are Muslims who seek reform of Islam. They are not, however, part of the mainstream since they are ‘dissidents’. She alleges that being a dissident or ‘Modifying Muslim’ entails potential peril:

Yet those under the greatest threat are the  and reformers: the Modifying Muslims. They are the ones who face ostracism and rejection, who must brave all manner of insults, who must deal with the death threats – or face death itself. (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 21])

and reformers: the Modifying Muslims. They are the ones who face ostracism and rejection, who must brave all manner of insults, who must deal with the death threats – or face death itself. (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 21])

There is a growing number of  Muslim citizens in the West who are currently braving death threats and even official punishment in dissenting from Islamic orthodoxy and calling for the reform of Islam. These individuals are not clergymen but “

Muslim citizens in the West who are currently braving death threats and even official punishment in dissenting from Islamic orthodoxy and calling for the reform of Islam. These individuals are not clergymen but “ ” Muslims, generally educated, well read, and preoccupied with the crisis of Islam.

” Muslims, generally educated, well read, and preoccupied with the crisis of Islam.

Among them are Maajid Nawaz (UK), Samia Labidi (France), Afshin Ellian (Netherlands), Ehsan Jami (Netherlands), Naser Khader (Denmark), Seyran Ateş (Germany), Yunis Qandil (Germany), Bassam Tibi (Germany), Raheel Raza (Canada), Zuhdi Jasser (U.S.), Saleem Ahmed (U.S.), Nonie Darwish (U.S.), Wafa Sultan (U.S.), Saleem Ahmed (U.S.), Ibn Warraq (U.S.), Asra Nomani (U.S.), and Irshad Manji (U.S.). (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 239])

8.4.How these collocate differences lead to deconstruction in Hasan’s framing

Let me now compare Hirsi Ali’s classification of Muslims with Hasan’s classification of the same. When Hasan mentions ‘Mainstream Muslims’, this is more or less equivalent to Hirsi Ali’s ‘Mecca Muslims’:

[B]

[ Muslims will respond positively to a call for reform from a woman who has described their faith as a “destructive, nihilistic cult of death” that should be “crushed”…

Muslims will respond positively to a call for reform from a woman who has described their faith as a “destructive, nihilistic cult of death” that should be “crushed”…

What about how Hasan sees reformists? Consider the following:

[B]

Then there is Ayaan Hirsi Ali. The Somali-born author, atheist and  -Muslim has a new book called Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now.

-Muslim has a new book called Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now.

[

[L]

What they don’t need are lazy calls for an Islamic reformation from  -Muslims and

-Muslims and  -Muslims, the repetition of which merely illustrates how shallow and simplistic, how ahistorical and even anti-historical, some of the west’s leading commentators are on this issue. It is much easier for them, it seems, to reduce the complex debate over violent extremism to a series of cliches, slogans and soundbites, rather than examining root causes or historical trends; easier still to champion the most extreme and bigoted critics of Islam while ignoring the voices of

-Muslims, the repetition of which merely illustrates how shallow and simplistic, how ahistorical and even anti-historical, some of the west’s leading commentators are on this issue. It is much easier for them, it seems, to reduce the complex debate over violent extremism to a series of cliches, slogans and soundbites, rather than examining root causes or historical trends; easier still to champion the most extreme and bigoted critics of Islam while ignoring the voices of  Muslim

Muslim  .

.

To conclude: had Hasan been arguing that reform of the Islamic world was not needed, one might say that Hasan not mentioning: i) the non-mainstream Muslim reformists detailed in Heretic; ii) the non-mainstream Muslim reformer Hashem Aghajari discussed in the Thomas Friedman article he criticises (see Section 5.1) would be irrelevant to his main goal: to attack those who have allegedly called for a Muslim Martin Luther(s) to lead an Islamic reformation directly analogous to the Christian reformation. But, to reiterate, in [K] Hasan does concede that reforms to Islam are needed. This legitimates a critical perspective on his argument’s framing which takes broad appreciation of Muslim reformist types in Heretic (especially as this is a book which Hasan has already strawmanned).

8.5.Summing up deconstruction I and II of Hasan’s wicker man

I have shown how further exploration of Heretic using digital text analysis tools helps to reveal conveniently that its central standpoints conflict with the macro-structural and micro-structural framing of Hasan’s argument more fully. Similar to Section 5, this is a misrepresentation wicker man which relies on omission from Hirsi Ali’s book, whether or not this is intentional.

9.Reflection

9.1.Demonstrations

In this article, I have shown the value of using digital text analysis tools for helping to reveal and deconstruct dialectical shortfalls of an argument where the text being criticised in that argument is large. Firstly, I deconstructed the op-ed argument in line with its dialectical obligations to represent accurately the portion of the long text it criticises. I showed the argument to be a straw man. I also showed the value of digital text analysis tools to help conveniently and rigorously explore how the wider standpoints of the long text problematise the argument’s framing. The much larger straw man or wicker man that I exposed went mostly beyond the op-ed’s dialectical obligations vis-à-vis its specific thesis. Yet, as I highlighted, the exploration of whether or not the op-ed is a wicker man was justified by i) the op-ed admitting that socio-economic, political and religious reforms to Islam were necessary; ii) Hirsi Ali’s book arguing for such reforms.

I showed that, once an argument’s misrepresentations and omissions are accounted for, the cohesive structure of the argument destabilises which, in turn, creates problems for its coherence. Accurate tracing, beforehand, of the micro-cohesive structure of the argument enabled acute appreciation of macro-cohesive structure. In turn, this facilitated a systematic deconstruction of the dialectical deficiencies of the argument. Moreover, I highlighted how relevant absences from an argument may not only occur through stark omission, but through use of different collocates for the same categories. Lastly, I should be explicit that the case study of this article is meant as an illustration of the value of software in education. I do not claim this case study to be an empirical test.

9.2.Methodological advantages

This article has modelled a pedagogy where digital tools emanating from corpus linguistics are used to generate objectively and conveniently the most recurrent topics (at least how the software identifies them), words and phrases in long standpoint data which, in turn, enable the analyst to see if they are absent from an argument of reasonable length which opposes that standpoint. In turn, rigorous critical grip on the argument’s dialectical quality is enabled. The student still needs to perform interpretative work to ascertain whether or not recurrent words and expressions in the attacked standpoint which are absent from the argument are, in fact, relevant ones. After all, algorithms cannot perform critical qualitative interpretation.

The key point here is that use of these tools sets the student up to do this not only in a convenient way. Since the tools also rein in arbitrariness, they augment the rigour of the dialectical evaluation. All judgement is subjective in taking place in a single head. But since judgement of straw man status is based on objectively-generated data, this increases the chances that others will find the judgement convincing. In other words, the approach increases the prospect that judgement of straw man status has inter-subjective validity. Lastly, there is another key methodological advantage. Targeted reading of big standpoint data on the basis of statistically frequent semantic domains, relatively frequent words and expressions automatically extracted from that data facilitates the efficiency of the straw man evaluation.

9.3.Pedagogical advantages

Once an argument has been judged to be dialectically fallacious or sound, this does not mean, naturally, that the student now needs to adopt the standpoint criticised in the argument. On the contrary, now that they understand both standpoints, they are in a position to decide where they stand in the debate and thus assert critical independence. This may be matured through researching other viewpoints and scholarship relevant to either side of the argument. Rodenbeck [15], for instance, finds Hirsi Ali’s categorisation, ‘Mecca Muslims’, to be reductive:

But surely the 1.5 billion “Mecca” Muslims do not all fit into a single hapless category. Like the members of any great religion, one might imagine they instead have a diversity of views, as designations that Muslims use for one another, such as, for example, Salafist, Sufi, Ismaili, Zaidi, Wahhabist, Gulenist, Jaafari, and Ibadi, would suggest.

The approach of this article can thus be used as a pedagogy which not only engenders intellectual satisfaction and empowerment from highlighting straw and wicker man arguments, but also extends critical awareness of domains of debate. It is best if the student is unfamiliar with the attacked standpoint. There is little point in using the strategy presented if the student already knows the attacked standpoint in detail. Felicitously, the pedagogy engenders a secure quantitative foundation for the student to develop their knowledge, and progress to making an informed decision about where they stand. Another pedagogical advantage is as follows: rhetorical sensitivity is sharpened. Students are able to see where categories in an argument might be insufficiently specific and differentiated in how they are used to describe the standpoint the argument opposes.

Lastly, should a student ascertain that, in fact, the argument accurately represents the long standpoint it attacks, they have not wasted their time. This is because they have established that the argument has passed a dialectical test of quality. And, whether or not the argument is a straw man or wicker man, if they choose an argument where they are (largely) unfamiliar with the attacked standpoint, the student importantly learns about a new domain of debate, or extends their appreciation of it, in a sustainedly engaged and fact-based manner. Positive things.

Notes

1 Made famous by the 1973 cult movie, ‘The Wicker Man’, an actual wicker man is a huge straw effigy. In pagan times, humans were trapped in the wicker man and sacrificially burned.

2 Similar definitions can be found in the literature: ‘Straw man fallacy – A fallacy committed when a person misrepresents an argument, theory, or claim, and then, on the basis of that misrepresentation, claims to have refuted the position the person has misrepresented’ (Govier [9, p. 201]); ‘Straw man fallacy: A form of fallacy of emphasis in which someone’s written or spoken words are taken out of context, thereby purposely distorting the original inference in such a way that the new, weak inference (the straw man) is easy to defeat’ (Baronett [2, p. 287]); ‘In the case of the Straw Man fallacy, the clear irrelevance emerges in the argument that is constructed on the basis of, or in response to, the misrepresentation or caricature’ (Tindale [17, p. 25]).

3 I stress ‘written’ here since lack of cohesion is much more immediately apparent in processing a written text than with real time processing of speech. Because of the cognitive limitations of real time processing of spoken language, it is possible that an audience may be persuaded by an oral argument – particularly where the speaker is seductive – when in fact it may not contain as much cohesion, or indeed coherence, as they might suppose.

4 On the cohesion/coherence distinction, see de Beaugrande and Dressler [6]; Widdowson [19, p. 49–51].

5 http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/may/17/islam-reformation-extremism-muslim-martin-luther-europe [accessed June 2018].

6 The figure of 69,546 words does not include the endnotes, or non-main body information such as the author’s biography and the book’s dedication.

7 A free 30-day trial is available. See https://www.sketchengine.eu [accessed June 2018].

9 Lemmas are conventionally represented in small capitals.

10 A stoplist is a list of words automatically omitted from a computer-generated word frequency list. Many are available free online, e.g. http://www.textfixer.com/resources/common-english-words.txt. There is no definitive stoplist since its makeup will depend on the purposes of the user. I created my own stoplist of English grammatical words (auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, determiners, modal verbs, prepositions, pronouns).

11 In order to leave Fig. 2 readable, I also do not annotate for grammatical cohesion vis-à-vis the lemmas of Table 1, e.g., where ‘He’ refers to ‘Luther’. Moreover, while the lemma call has seven word forms, I do not annotate in Fig. 2 for this lemma since it predominantly collocates with ‘reform’.

12 https://www.memri.org/reports/call-islamic-protestantism-dr-hashem-aghajaris-speech-and-subsequent-death-sentence [accessed June 2018].

13 https://calibre-ebook.com/ [accessed June 2018]. Before loading up to Sketch Engine, I deleted from Heretic text which is not part of its main body and appendix, e.g., frontispiece, contents and endnotes.

14 I focus on lexical words rather than grammatical words since it is with the former where conceptual content lies. As usual, to remove the ‘noise’ of grammatical words, I employed a stoplist – the same one that I used in Section 4.2.2. Just as I did in that section, I treat all words as lower case in order to derive the most birds-eye view perspective on lexical frequency.

15 When I first encountered Hasan’s argument, I had not yet read Heretic. But I was aware of Hirsi Ali’s status as a long standing critic of Islam and especially for controversial broad-brush statements she made in the past. Consider, for example, the following in an interview from 2007 with Rogier van Bakel for Reason magazine:

Hirsi Ali: I think that we are at war with Islam. And there’s no middle ground in wars. Islam can be defeated in many ways. For starters, you stop the spread of the ideology itself; at present, there are native Westerners converting to Islam, and they’re the most fanatical sometimes. There is infiltration of Islam in the schools and universities of the West. You stop that. You stop the symbol burning and the effigy burning, and you look them in the eye and flex your muscles and you say, “This is a warning. We won’t accept this anymore.” There comes a moment when you crush your enemy.

[…]

Rogier van Bakel: So when even a hard-line critic of Islam such as Daniel Pipes says, “Radical Islam is the problem, but moderate Islam is the solution,” he’s wrong?

Hirsi Ali: He’s wrong. Sorry about that.

Hirsi Ali is given the opportunity to clarify that by ‘Islam’ she might instead mean ‘radical Islam’ and thus that it is jihadist terrorism, not Islam per se, that needs to be ‘defeated’ or ‘crushed’. But, she declines to align with this more reasonable position. Hirsi Ali’s standpoint here is somewhat baffling given that i) the vast majority of Muslims are peaceful; ii) those most affected by jihadist violence are Muslims.

So when I encountered Hasan’s argument, I was not positively predisposed to Hirsi Ali especially since Hasan reminds the reader, in paragraph [B], of her previous incautious remarks. But, in Hasan’s summary, no longer was Hirsi Ali calling for Islam to be ‘crushed’ in a war with the West. Instead, in Heretic she was advocating the much less radical position that Islam needed reform. Intrigued that she had softened her position, I was interested to see whether or not Hasan had accurately represented it. My examination in what follows shows that Hasan’s portrayal of other aspects of Hirsi Ali’s book is not a fair representation.

16 ‘ISIS’ stands for ‘Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’. It is a jihadist terrorist organisation whose religious outlook is Wahhabist. ISIS is also known as ‘ISIL’ (‘The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’), ‘IS’ (Islamic State) and by its Arabic acronym ‘Daesh’.

17 A free one month trial is available. See http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/wmatrix/ [accessed June 2018].

18 Each text in AmE06 is around ‘as close as possible to 2,000 words to the nearest complete sentence’. Moreover, ‘all texts [in AmE06] have hard copy publication years between 2004 and 2008, with year and frequency as follows: 2004 (1 text), 2005 (48 texts), 2006 (400 texts), 2007 (45 texts), 2008 (6 texts), or 80% from 2006, and 98.6% 2005–2007’ (Potts and Baker [13, p. 302]). Since the overwhelming majority of the texts were published in 2006, this explains the name of the corpus.

19

20 Her other theses are as follows:

1. Ensure that Muhammad and the Quran are open to interpretation and criticism;

2. Give priority to this life, not the afterlife;

3. End the practice of “commanding right, forbidding wrong”;

4. Abandon the call to jihad. (Hirsi Ali [10, p. 74]).

21 The reader may be wondering why I stop at 2-grams. Why not examine 3-grams, 4-grams etc? The larger the text or corpus, the more likely that there will be n-grams in excess of 2-grams. However, these are likely to be n-grams which contain grammatical words, which thus do not contain conceptual content. For example, the 3-gram, ‘the Muslim world’ occurs forty-one times in Heretic. But since the 2-gram ‘Muslim world’ occurs forty-three times, examining the 3-gram does not reveal much more. Besides, I am using Sketch Engine to contrast the content of Heretic with an argument of 1,169 words. Given the size of the latter, it would be unlikely to have highly recurrent 3-grams. Indeed, the most common 3-gram in Hasan’s argument, at only three instances, is ‘a Muslim Luther’.

22 There are 648 instances of muslim in Hirsi Ali’s book. 349 instances are ‘Muslims’ and 299 are ‘Muslim’.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Mehdi Hasan and Guardian News Media for permission to reproduce ‘Why Islam doesn’t need a reformation’, 17th May 2015 Copyright Guardian News & Media Ltd 2018.

References

[1] | S. Aikin and J. Casey, Straw men, weak men, and hollow men, Argumentation 25: ((2011) ), 87–105. doi:10.1007/s10503-010-9199-y. |

[2] | S. Baronett, Logic, 1st edn, Oxford University Press, Oxford, (2008) . |

[3] | T. Bowell and G. Kemp, Critical Thinking, 4th edn, Routledge, Abingdon, (2015) . |

[4] | M. Browers and C. Kurzman, in: An Islamic Reformation? Lexington Books, Lanham, MD, (2004) . |

[5] | R. Carter and W. Nash, Seeing Through Language, Blackwell, Oxford, (1990) . |

[6] | R. de Beaugrande and W. Dressler, Introduction to Text Linguistics, Longman, London, (1981) . |

[7] | R.M. Entman, Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm, Journal of Communication 43: (4) ((1993) ), 51–58. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x. |

[8] | R. Fowler, Linguistic Criticism, 2nd edn, Oxford University Press, Oxford, (1996) . |

[9] | T. Govier, A Practical Study of Argument, 4th edn, Wadsworth, Belmont, CA, (1997) . |

[10] | A. Hirsi Ali, Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now, Harper Collins, New York, (2015) . |

[11] | T. McEnery and A. Hardie, Corpus Linguistics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, (2011) . |

[12] | A. O’Keeffe and M. McCarthy (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics, Routledge, Abingdon, (2010) . |

[13] | A. Potts and P. Baker, Does semantic tagging identify cultural change in British and American English?, International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17: (3) ((2012) ), 295–324. doi:10.1075/ijcl.17.3.01pot. |

[14] | P. Rayson, Wmatrix: A web-based corpus processing environment, Computing Department, Lancaster University, 2009, http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/wmatrix/ [accessed June 2018]. |

[15] | M. Rodenbeck, How she wants to modify Muslims, Review of ‘Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now’ by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, The New York Review of Books, December 3, 2015 Issue. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2015/12/03/ayaan-hirsi-ali-wants-modify-muslims [accessed June 2018]. |

[16] | R. Talisse and S. Aikin, Two forms of the straw man, Argumentation 20: ((2006) ), 345–352. doi:10.1007/s10503-006-9017-8. |

[17] | C. Tindale, Fallacies and Argument Appraisal, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, (2007) . |

[18] | J. Wenzel, Three perspectives on argument, in: Perspectives on Argumentation: Essays in Honour of Wayne Brockriede, R. Trapp and J. Schutz, eds, Waveland Press, Prospect Heights, IL, (1990) , pp. 9–16. |

[19] | H.G. Widdowson, Discourse Analysis, Oxford University Press, Oxford, (2007) . |