Inferences and illocutions

Abstract

In several papers Budzynska and Reed have argued that inferences should be ‘anchored’ to relations between utterances rather than to utterances themselves; then, by appeal to what they call ‘dialogue glue', these relations are somehow reified as ‘implicit’ speech-acts. In this paper I will argue that this is a mistake caused by confusion over different ways an illocution can be relational and that there can be no such thing as implicit speech-acts as they describe them, and so the speech-act that they claim is performed implicitly between utterances is actually performed explicitly, if indirectly, at the time of the original utterance. It is here that the inference should be anchored. They also argue that when an arguer's credibility is attacked it is the illocution that is undermined rather than the inference, credibility being linked to the illocution as one of its conditions of satisfaction. When understood in a certain way that I will briefly explain in the paper, I will argue that this is true, that the illocution is undermined, and that this reveals something very interesting about the nature of many of the ad fallacies, but speech-act theory on its own does not support this since credibility is not required for the illocution to be successful. Lastly, Budzynska claims that a speaker cannot testify to his own credibility and that this, rather than being an argumentative circularity, is circularity in the assertion itself, since it mentions one of its own conditions of satisfaction. She calls this ‘circular assertion'. While I accept the claim that there is this kind of non-argumentative circularity, I do not find it to be as problematic as Budzynska seems to.

1.Introduction

In a number of papers (see Budzynska & Reed, 2011; Reed, 2011; Reed & Budzynska, 2010) Chris Reed and Katarzyna Budzynska have argued for what they call Inference Anchoring Theory (IAT). The idea behind IAT is to provide a model in which both the argumentative dialogue and the inferential structure it gives rise to can be shown together and their inter-relationships explicated.11 Starting from the idea that argumentation is a speech-act complex and that speech-acts of arguing are relational (Budzynska & Reed, 2011, p. 1), they claim that what links the dialogue to the inferential structure is not an explicit speech-act but an implicit speech-act that ‘glues’ explicit speech-acts to one another, and it is this implicit speech-act that ‘anchors’ the inference and (rightly, in their opinion) associates the inference – which is after all a kind of transition between propositions – to an analogous transition between dialogue moves. Thus, they will also say that the inference and implicit speech-act are associated with the application of a transition rule in the dialogue.22

Granted that this ‘dialogue glue’ exists, why is it here, in these transitions, that the inference is anchored? The following rather extended quotation seems to capture their motivation (Budzynska & Reed, 2011, p. 4):

If someone utters the locution p, there is no way in general to know what speech act is being performed. … In order to assess, or analyse, or make a judgment of felicitousness of a speech act in general, we need to know more about its context.

With arguments, the situation is exacerbated, because the speech act of arguing is in some way epiphenomenal on the brute speech acts which are assertive and directive. … . For during a discussion, it is quite possible to hear a speaker uttering I hereby assert that p … but for us still to be unsure whether an argument is being put forward or not. We would still need context in order to be able to analyse the speech act of argumentation. This follows directly from pragma-dialectical analysis which views the speech act of assertion (in this case) as occurring at the ‘sentence’ level, and the speech act of argumentation as occurring at a ‘higher textual level.’

From pragma-dialectics, then, we have that the speech act argue(p) is performed in virtue of the performance of the speech act assert(p). … [T]he performance of argument is not an intrinsic feature of the assertion of p, but rather an extrinsic feature, dependent upon the relationship that the utterance of p has on other utterances. … . An argument for q cannot be an intrinsic feature of the locution, p, or even of the locution I hereby assert that p. It would be an intrinsic feature of the locution I hereby assert that p so q, but here our sloppiness in characterisation hides a hopelessly redundant analysis: we would have to maintain that the speaker's utterance of p is actually best analysed as the compound locutions of I hereby assert that p, and that p so q, and that q, as a result (i.e. four separate assertions). It does not seem reasonable to pack all of this into the hearer's utterance p, not least because we would undoubtedly want to analyse the speaker's utterance of p differently on a different occasion … . Our goal, then, is to develop an account of the speech action … being performed in some way implicitly, but which also captures the essential relational nature of the speech act.

There is much to admire in IAT, and I find myself agreeing with much of it. My main objections are theoretical and concern the way in which they use speech-act theory; many of the model's most distinctive features do not follow from speech-act theory in as straightforward a way as Budzysnka and Reed seem to suppose. Most importantly, a speech-act is performed when there is an utterance. True, there is such a thing as an indirect speech-act which can include non-verbal forms of communication, but any meaningful communication can be analysed as a speech-act, which is to say, into an illocutionary force (assertions, arguings, and in general the type of speech-act) and a propositional content (what is asserted, argued, etc.). In short, there cannot be ‘implicit’ speech-acts, for there is no utterance.

I will in Section 3 discuss in some detail what kind of speech-act I think is involved. It should be noted that it is not entirely clear from what they say above what kind of speech-act Reed and Budzysnka think that argue(p) is; to say that

(a) we have to refer to dialogical context in order to analyse what speech-act is performed

does not, in itself, imply that

(b) argue(p) cannot be performed successfully without the surrounding dialogue.

(a) might be true of any illocutionary act whatever, whereas (b) specifically construes the speech-act as ‘relational'. Reed and Budzysnka say (a), but although they do not say so explicitly here, I think that when they refer to ‘the essential relational nature of the speech act’ they are committing themselves to (b) and to the claim that (a) does imply (b), since it is precisely because the speech-act is relational in this way that it is claimed to be implicit, and this in turn accounts for the most characteristic feature of IAT, namely the anchoring of the inference on this speech-act and on this relation. But in fact, to reach this conclusion we must also suppose that

(c) a relational speech-act is not instantiated by any utterance but by the relation between utterances.

Only if (c) is true are we left with the result that the speech-act in question is actually implicit, and if it is false we simply anchor the inference to the original locution which may, however, instantiate more than one relevant illocutionary act. Even if (b) is true and the speech-act is relational, it still does not follow that this speech-act is implicit. So, (a) does not imply (b) and (b) does not imply (c); yet it seems that Reed and Budzysnka thinks they do. So when, in Section 3, I argue that (b) is false and that the speech-act is not relational in the way Reed and Budzysnka seem to suppose, it should be borne in mind that I could be wrong about this and still Reed and Budzysnka would not have what they want, because, as I will also show in Section 3, (c) is false.

Let me elaborate on (a). Certainly, in order to determine the illocutionary force we often have to look at the surrounding context, and without that context we may not be in a position to analyse some locution as instantiating a certain illocutionary force, but that we as analysts are not in the position to ascribe such a force does not mean that the speech-act does not have that force, and the illocutionary force is intrinsic to the illocutionary act and makes it the kind of illocutionary act it is. Our ascribing that force to the speech-act may be extrinsic in the sense that we could not do it on the basis of the utterance alone but only when inserted into a dialogue, but that is quite another matter. In short, I want to show that (3) above does not follow from (1) and (2), and, since it is in virtue of the illocutionary force and not in virtue of the propositional content that this kind of dependence on context is intrinsic to the speech-act, (4) is simply irrelevant – to say that for an illocutionary act to have the illocutionary force it has requires there to be believed to be a certain relation between propositions does not make all this extra propositional information part of the act's propositional content. The outcome of all this is that the inference is anchored to the utterance as analysed as having a certain (argumentative) illocutionary force.

Note that there is nothing untoward in one and the same locution being simultaneously an instantiation of any number of illocutionary (or, for that matter, perlocutionary) acts. This is obvious from the fact that what characterises the illocutionary force is a set of rules or conditions of satisfaction, and different sets of conditions may be satisfied by the same thing. For instance, an utterance may be analysed as an assertion when we as the analysts feel justified in attributing to the speaker sincerity, for sincerity is the condition of satisfaction of the illocutionary act of asserting; if I try to assert p when not believing p then my act of asserting will not be successful. In most conversational contexts where there is some fact-stating discourse, we take sincerity for granted. But the very same utterance could equally be analysed as merely saying something, which does not demand sincerity, and also as something stronger than an assertion that requires not only sincerity but also that the speaker takes herself to have evidence for what she says and that justifies what she says. We do not have to choose between different ways of analysing the utterance: the same utterance, because the speaker satisfies all three sets of conditions, performs all three illocutionary acts.

I should say more at this point about conditions of satisfaction. There are two basic types of illocutionary act: constatives and performatives. Constatives have internal conditions of satisfaction. Performatives have both internal and external conditions of satisfaction. Let me explain what I mean by this.

Illocutionary acts of the constative type have only internal conditions of satisfaction, e.g. to ‘assert’ one must be in the right psychological state, and no (non-psychological) fact about the world can make one's assertions unsuccessful. The world can make what one asserts false, of course, but as long as one sincerely believes the propositional content of the act to be true then one's illocutionary act is no less an assertion for all that. Mostly the illocutionary acts we will be considering are of this constative type.

Illocutionary acts of the performative type have external conditions of satisfaction as well; one must not only be in the right psychological state in order to successfully perform this illocutionary act, but certain facts about the world must also obtain. A typical example is someone carrying out a baptism or a wedding: only those with a particular authority can carry out such illocutionary acts successfully, so that if one without the authority to baptise utters the words ‘I baptise you Peter’ then he has not performed a baptism, no matter how sincere he is or even if he mistakenly thought he had the authority.

Whatever type of illocutionary act is in question, in judging it to have been successfully and felicitously carried out we are committed to taking its conditions of satisfaction to be satisfied; e.g. asserters to be sincere, baptizers to be authorised. Budzysnka and Reed are quite right to say above that to ‘make a judgment of felicitousness of a speech act in general, we need to know more about its context’ – we need to know whether the context entitles us to attribute these commitments, to think these conditions of satisfaction are satisfied. But, as they also say here, this is true (and, in fact, trivially so) of speech-acts in general, yet surely they would not claim of all speech-acts that they have an ‘essential relational nature'. The implied distinction between speech-acts that are relational and those that are not seems unprincipled; it certainly does not follow from the fact that we need to refer to context in making interpretations. When only internal conditions of satisfaction are involved, the existence or epistemic availability of context is a problem for the process of analysis, but makes no difference at all to what constatives there are and whether they are felicitous. It is only for performatives that the existence of the surrounding context or lack thereof (this being a fact about the world and consequently an external condition) can make a difference to whether an utterance instantiates that performative. Thus, what I think they mean is that some speech-acts are relational to the surrounding dialogue and, as (b) says, cannot be performed successfully without that dialogue's existing, and conversely we are committed to that dialogue's existence when we judge such a relational speech-act to be felicitous. We will consider some speech-acts like this in Section 3, where I will deny that argue(p) is among them.

As we will see later, in this case the class of performatives in question are those that are involved in dialogue, for which it is constitutive that they be related to other real utterances. At the risk of repeating myself, when Reed and Budzysnka say ‘[T]he performance of argument is not an intrinsic feature of the assertion of p, but rather an extrinsic feature, dependent upon the relationship that the utterance of p has on other utterances’ it is not clear whether they are still talking merely about the relevance of those other utterances to the process of analysis, or whether they have inadvertently slid into saying that the speech-act argue(p) is of this dialogical kind. I will argue in Section 3 that even if it is of this dialogical kind, it is certainly not implicit but is performed when the utterance is made and not in the course of some transition. Then, I will argue that argue(p) does not actually depend on the existence of other real utterances to be instantiated; the fact that we may not know it has been instantiated because the context is epistemically unavailable to us is beside the point. In fact, I will argue that we may perform the argumentative speech-act without the context existing at all, provided only that we have all the right beliefs: argumentative speech-acts are constatives.

Generally, the propositional content will be the same in each case no matter how we analyse the utterance, but not necessarily. If I assert that p and that p→q in order to prove that q, then the propositional content of my illocutionary act of proving is q even though I never utter ‘q’ on its own; at the same time that I perform the illocutionary acts of asserting p and p→q I perform the illocutionary act of proving that q. That I believe p and p→q satisfies a condition of my act of proving, namely, that I have evidence for what I say that justifies it. Note that the conditions of satisfaction of ‘proving’ are still internal conditions, notwithstanding the fact that what I believe involves a relation. So, we can say that there is a relation between my assertions and my provings, but there is nothing very mysterious about this that would force us to say that there is anything extrinsic about proving, still less is there any reason to posit this curious class of implicit speech-acts. I will argue later that ‘arguing’ is like ‘proving’ in this respect; it is not relational in any way that introduces an external condition of satisfaction.

The other main bone of theoretical contention with IAT concerns the way in which certain speech-acts can be seen as attacking the illocutionary force of other speech-acts rather than as undermining the epistemological credentials of their propositional contents. I think there is something very right about this; in Botting (2013) I tried, with limited success, to do the same thing. The problem is that Budzysnka seems to think that this follows in a fairly straightforward way from things Austin said about speech-acts; my view is that she misunderstands what Austin says, specifically about presupposition. She claims that someone who makes an assertion is ‘presupposed’ to have evidence for what they assert; Austin does not say this, but that assertion ‘implies’ sincerity, where this is a much weaker condition than having evidence. It does not follow that because you think the speaker does not have good evidence for her claim that she is insincere; hence, it does not follow that her acts of asserting are any less felicitous.33

2.An example

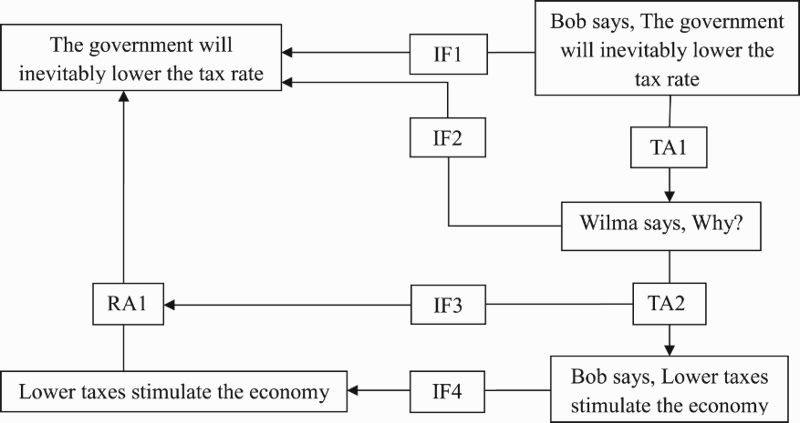

This example from Budzynska and Reed (2011, p. 7, Figure 1) illustrates how they propose to analyse an argument; on the left is the inferential structure and on the right are propositional reports of locutions (i.e. not speech-acts, or propositional reports of speech-acts, but propositional reports of what people say, namely, their utterances).

The relations between the different parts of the inferential structure (the premises and conclusion of the argument) are called Rule Applications (RA) and denote applications of some inferential rule or argumentation scheme: in Figure 1 this is RA1. The relations between the propositional reports of locutions are called Transition Applications (TA) and denote applications of transition rules: in Figure 1 these are TA1 and TA2. What relates the propositional reports of locutions on the right to the propositions on the left are instances of illocutionary schemes, denoted by IF1, IF2, and IF4 (Reed, 2011, pp. 7–8).

Figure 1.

Basic inference anchoring.

The thing to note here is that the inference from ‘Lower taxes stimulate the economy’ to ‘The government will inevitably lower the tax rate’ denoted by RA1 is not linked to any of the locutions being reported themselves but to the transition TA2, or rather, on a relation between two locutions made by applying a transition rule, and it is on this that the inference is anchored; this relation is reified as an implicit speech-act whose illocutionary connection to the inference is given by IF3. This anchored inference (RA1) is the most basic possible – from one proposition to one other. More complicated examples could be built from this basic type, and all examples will anchor inferences in this way.44 Figure 1, then, illustrates in its most basic form IAT's boldest and most interesting claim – that inferences are anchored to implicit speech-acts – and is a suitable example on which to base discussion of that claim, and hopefully to show that this claim is mistaken. If this claim is not true in this case, it will not be in other cases either.

3.In what way is the speech-act of arguing ‘relational’?

I will argue that although there are illocutionary acts that are relational in the dialogical way Budzynska and Reed seem to be attributing to argumentative speech-acts, it is not clear that argumentative speech-acts are relational in this way; above, I said they were constatives, which are relational only in the trivial way that an analyst may need to refer to context to determine what these illocutions are. If they are not relational in this dialogical way, then there might not even be a relation on which to anchor an inference.

But, more importantly: even if the illocutionary act of arguing were relational in this way, this speech-act is performed when the utterance is performed, and is not implicit in Budzysnka and Reed's sense of somehow being performed when a transition rule is applied. Either way, the inference is not anchored on an implicit speech-act occurring somehow between locutions when dialogue rules are applied. Speech-acts cannot be implicit. This only repeats what I said in Section 1.

That some speech-acts are relational in the kind of way that Budzynska and Reed might be suggesting is described by Searle (1979, p. 6) in the following passage:

Some performative expressions serve to relate the utterance to the rest of the discourse … . Consider, for example, ‘I reply’, ‘I deduce’, ‘I conclude’, and ‘I object’. These utterances serve to relate those utterances to other utterances and the surrounding context. The features they mark seem mostly to involve utterances in the class of statements. In addition to simply stating a proposition, one may state it by way of objecting to what somebody else has said, by way of replying to an earlier point, by way of deducing it from certain evidentiary premises, etc.

Let us concede for the moment that argumentative acts are performative in this way. There seems to be a disanalogy between what Searle is proposing here and what Budzynska and Reed are arguing. These speech-acts are indirect but not implicit; they are simply speech-acts performed when the utterance is performed in virtue of satisfying the conditions of satisfaction for that illocutionary force. When I utter p this may satisfy the conditions for asserting that p and also the conditions for stating that q if it satisfies the relational conditions for stating that q, e.g. because I believe p is evidence for q. Budzynska and Reed are quite right to say that being related to other utterances is not an intrinsic feature of asserting that p, but (according to what Searle says here) it is or can be an intrinsic feature of stating that q, and when I perform the speech-act of asserting that p I also may indirectly perform the speech-act of stating that q. This point is quite general and applies to argumentative speech-acts equally; Reed and Budzynska say that it cannot be intrinsic to a speech-act that it be relational in this way, and move from this supposed fact to the idea that the speech-act is somehow in the relation itself, that is to say, in the ‘glue'. But this argument fails at the first step, and thus the problem that they use dialogue glue to solve is entirely a pseudo-problem (which is not to say that there is anything wrong with the notion of dialogue glue as such). Furthermore, it fails irrespective of whether the argumentative acts in question are performative or constative, since it is the same utterance being analysed, and thus the inference is anchored here. In short, it seems to be a misunderstanding of speech-act theory that would make speech-acts implicit because they are relational in this way, and locate them in the transition between utterances (or between speech-acts). Instead, it is just the original utterance (e.g. the utterance of p) differently analysed. Nor is it any problem, as Budzynska and Reed seem to suppose, that in some contexts it is asserting that p that one is interested in and in other contexts it is stating (or arguing) that q. Undoubtedly, as they say, we do want to analyse the speaker's utterance of p differently on a different occasion, but there is nothing to stop us from doing so, despite the fact that in one case the propositional content is p and in the other it is q.

So, even if the speech-act of arguing is relational in the way that Searle is describing here it still does not follow that there are implicit speech-acts performed when we apply a transition rule, or that inferences are anchored to them. However, I am not convinced that the speech-act of arguing is relational in the way that Searle describes here. In fact, there seems to be disanalogies even within his own examples. Above, I followed Searle in counting ‘stating that q’ as related to other parts of the dialogue, but I am not convinced this is actually correct. My utterance of p counts as stating that q if there is (or, rather, I believe there to be) the right relation between p and q, and not because of any relations between utterances of p or q. In fact, q may not be explicitly uttered at all, but in some other way determined by the context. Such acts are relational, certainly, but to propositions rather than to utterances or other parts of the dialogue. This means that such acts do not require other utterances or a surrounding dialogue to be performed successfully – they are constatives, having only internal conditions of satisfaction. An example of this might be proof. If I make certain assertions, then these assertions amount to a proof that q if I think that q follows from the propositions I assert. If it is not q but something else that I believe follows, then my illocutionary act of proving fails. Because ‘to prove’ is a success-verb we would say also that it is a bad proof if q does not actually follow, but this does not mean that there is anything infelicitous with the illocution as such – it is not a ‘misfire’.

Suppose that you require a proof of q and request this by uttering the locution ‘Why q?’ I utter: ‘Because p'. In this context, when I do this I perform the illocutionary act of proving q. Despite the fact that ‘q’ does not actually appear in any part of my utterance, it is nonetheless the propositional content of my illocutionary act of proving that q and can be denoted as prove(q). It is not relational to the utterance of ‘Why q?’ in that, even if there were no such utterance (e.g. I only imagined it), the illocutionary act could still be successfully performed (even if nobody else knew that this was what I was doing). It is a constative, and only requires that I have the right beliefs in order to be performed successfully. In the same context, my utterance qualifies as an answer or reply to your utterance; without your utterance, it makes no sense to call my utterance a reply. In this case, my illocutionary act of replying is genuinely relational to your utterance of ‘Why q?’ It is a performative, and cannot be performed successfully without the preceding part of the dialogue.

It may be objected ‘But the only reason we know what it is meant to be a proof of in this case is because of the surrounding dialogue. So it is related to the dialogue after all.’ But this is a quite trivial way in which speech-acts are relational and is the same for all speech-acts that are not fully explicit. Indeed, this is Budzynska and Reed's starting-point in the excerpt above, before they go on to say that the problem is exacerbated when the utterance is embedded in higher textual levels, like that of argumentation. Although it is exacerbated, it is still basically the same problem, and does not for this reason alone introduce any problematic kind of relatedness. Suppose I utter the locutions: ‘David is 50 tomorrow. He is really looking forward to his birthday.’ To resolve the reference of the pronouns in ‘He is really looking forward to his birthday’ we have to refer to the preceding locution where ‘David’ is identified as the referent. The result of this is that we analyse ‘He is really looking forward to his birthday’ as an assertion whose propositional content is ‘David is really looking forward to David's birthday.’ This speech-act is not relational, however. Context is continually made use of in order to assign a fully propositional content to the illocutionary acts we are analysed as having performed. This is quite trivial and does not make the second locution relational, despite its being embedded, so to speak, at a higher textual level than that of the sentence. Similarly, with speech-acts that are relational to propositions, we may determine what propositions these might be by looking at other utterances, but these utterances serve only to help us to analyse the illocutionary act and are not themselves related to the act – the act would not fail to be successful or felicitous if those utterances were not there.

I find Searle's inclusion of ‘stating a proposition … by way of deducing it from certain evidentiary premises’ to be more like a proof than a reply. I would say that the same is true for argumentative speech-acts. There is a general confusion here between a speech-act complex and a complex speech-act. Argumentation is a speech-act complex – it is composed of numerous speech-acts performed by at least two participants. It is in this sense that argumentation occurs at a higher textual level than the speech-acts of which it is composed, and some of the illocutionary acts occurring at this textual level will be relational to other utterances. If there are no such utterances, there is no such argumentation, and we can say that the speech-act complex is void.

Do we, then, fail to argue if there is no such utterance as, for instance, the assertion of the conclusion or the asking of a question why some proposition is true? Are argumentative acts performatives because related to a dialogue that must actually exist, as we assumed earlier?

It does not follow from the fact that a speech-act complex involves real speech-acts that argue(q) requires their existence; only if argue(q) itself occurs at this higher textual level, or is dialogically related to the other locutions or illocutions that compose the argumentation, would this follow. What it is related to is to other propositional contents. What makes my utterance of p an instance of the illocutionary act argue(q) is that the conditions of satisfaction for this act demand that I have certain beliefs concerning the relation of p to q, and not that it be related to another illocutionary act such as may be instantiated by ‘Why q?’ It is perfectly valid to say that such an illocutionary act will help those in the dialogue to resolve the reference of what the arguer is arguing for, but this does not affect the illocutionary act of arguing itself. Nor does the act of arguing fail or ‘misfire’ in some way if there were no such utterance of ‘Why q?’ The conditions of satisfaction of an act of arguing are all internal: they depend only on the speaker being in the correct psychological state, and not on the actual existence of other utterances (as would be the case for replies).

Consider an auditory hallucination in which only my uttering p is real. Is there an argumentation here? I am inclined to say no, because argumentation is a speech-act complex and as such requires real relations between real illocutions. Does this mean that, when I utter p, I cannot be arguing that q? Again, I think the answer is no, because I believe that q follows from p, and I am uttering p because I believe this. I think this is a successful performance of argue(q).

Does this lead to a hopelessly redundant analysis, as suggested in (4) above? No.

Firstly, we have already said that the propositional content of a speech-act need not be the same as the propositions expressed in the locution. If I say ‘Upstairs, first door on the left’ then I might be performing the speech-act of giving you directions to my bathroom, but although this being the way to my bathroom is not contained explicitly in the content of my utterance, it will be part of the propositional content of my illocutionary act of giving you directions to my bathroom, that is to say, I give you directions to my bathroom in virtue of asserting ‘Upstairs, first door on the left.’ Similarly, I do not (unless I am arguing circularly) perform argue(p) in virtue of performing assert(p) as Budzysnka and Reed (and possibly pragma-dialectics also) seem to suppose that I must be when they criticise this as hopelessly redundant; rather I perform argue(q) (although q is not a part of my locution) in virtue of performing assert(p). There is no problem with one and the same utterance being an instance of a variety of illocutionary acts, or of our indirectly performing one by performing another (as I proposed was the case when I stated that q by stating that p, when p was given as evidence for q); it depends only on what acts’ conditions of satisfaction are satisfied. Wanting to analyse the locution in one way in one context and in another way in another context is not a problem.

Secondly, it can be an intrinsic feature of an illocutionary act that its propositional content be related to a proposition without embedding that proposition in the propositional content. Budzynska and Reed too quickly assume that if it is an intrinsic feature of my speech-act of arguing that it is an argument in favour of q, then this amounts to making what I say elliptical for uttering something like ‘q, because ____'. But this is not so. It is part of the conditions of satisfaction of arguing that I believe that what I assert are reasons for what I am arguing for, not part of the propositional content.

In short, the inference should be anchored to a speech-act that is relational in only this sense and does not, for its successful performance, require the dialogue surrounding it. The dialogue helps us in our analysis, but that is quite trivial. Also, I see no reason to call this speech-act ‘implicit', though it may be performed indirectly. I will illustrate this with a counter-example.

4.A counter-example

Suppose that Wilma is just a figment of Bob's imagination, or drops dead before she can take her turn in the dialogue. Thus, there is no locution of ‘Why?’ It would seem that this should not affect the inferential structure, yet there cannot be a relation between locutions when one of the locutions is not there; relations can only obtain between real existents.55

To a certain extent, Budzynska and Reed do not need to worry about this, since their aim is to model argumentative dialogues in which the genuine existence of dialogue can be taken for granted. Although I believe it is a conceptual mistake to anchor inferences on transitions, this need not affect its usefulness as a model too badly.

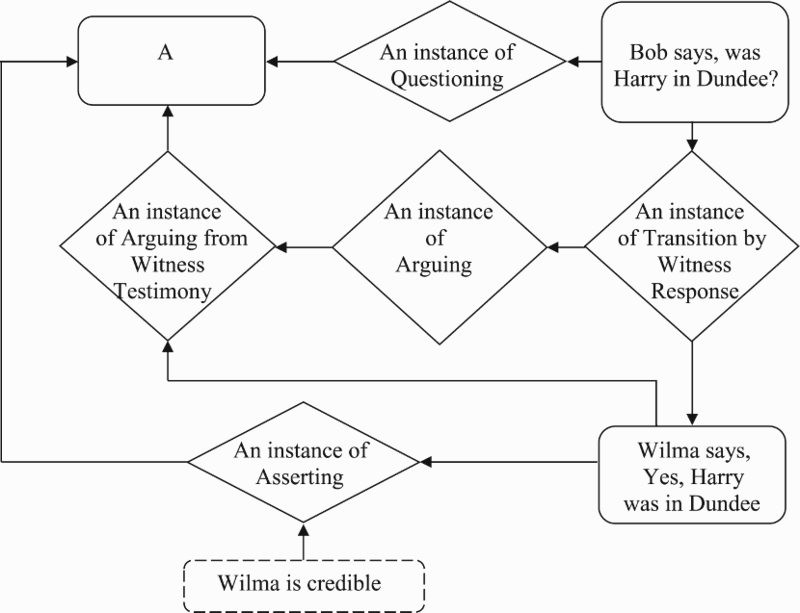

However, Reed (2011, p. 13, Figure 4) also gives the following example (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of an exchange between prosecutor and witness for the prosecution.

Ignore the dotted box for the moment (I have added it to Reed's diagram for use in later discussion). The propositional report Wilma says, Harry was in Dundee here seems to be a node in both the dialogical and the inferential structure, the latter because it is evidence that Harry was in fact in Dundee. The inferential relation then goes from this to A through the RA Arguing from Witness Testimony. This inference is anchored to the TA Transition by Witness Response though an implicit speech-act of Arguing.

But is there such an implicit speech-act? Reed and I agree that Wilma is not arguing.66 Is Bob arguing? Possibly, since we are to suppose here that Bob is questioning Wilma as a witness for the purposes of establishing the whereabouts of Harry, as Reed says. But here, I think, this is because in asking the question Bob is indirectly saying that Wilma is saying that Harry was in Dundee. It is not just what she says but the fact that she says it which, when it is assumed that she is sincere and obeying Gricean maxims, provides the evidence for the claim that Harry is in Dundee, that is to say, that makes the propositional report a node in the inferential structure. So Wilma says, Yes, Harry was in Dundee is an inferential node. On this we also agree. However, Reed has this as the locutionary node as well, whereas I think, on analogy with Figure 1 where the locutionary node was Bob says x and the inferential node x, that the propositional report must, then, be embedded in another (namely, Bob says, Wilma says, Yes, Harry was in Dundee) in order for there to be an illocutionary connection to the node in the inferential structure from the dialogue structure.77 As Reed's diagram has it, there simply is no such connection; in fact, Wilma says, Yes, Harry was in Dundee occurs on the right-hand side (namely, the dialogue side) of the diagram. Reed thinks that the proposition can do double duty, so to speak, but this seems wrong to me; although the propositional report Wilma says, Yes, Harry was in Dundee is undoubtedly true, it does not capture the argumentative relevance of this locution, which is, as I said, the fact that she said it more than what she said, and it is Bob making this argument, so the propositional report should report Bob's raising this fact as a reason for A in the diagram, i.e. as Bob says, …

5.Ad hominem attacks

As just mentioned, it is only when it can be assumed that the speaker is sincere and has evidence for their claim (thus satisfying the Maxim of Quality) that the fact that they have made the claim can be construed as strong evidence for the claim being true.

Sincerity is a felicity condition of assertive and argumentative speech-acts. Thus, any attack on the speaker's sincerity or ethos would seem to undercut the inference from the speaker's saying something to its’ being true. Such attacks can be carried out by asking critical questions connected to the inference, in this case to the RA Arguing from Witness Testimony. Ethos is diagrammed by a dotted box with an arrow pointing to the illocution to show that what it is supporting or attacking is a condition of satisfaction of the illocution. In Figure 2 I have diagrammed this as the dotted box Wilma is credible (Budzysnka, 2013; Budzysnka & Reed, 2012). If the attack succeeds in laying grounds for doubt that the speaker is sincere, this implies that the illocutionary act has misfired.

This is fine as far as it goes, but the details involve a confusion and lead Budzysnka to make stronger claims than her premises really permit. In Budzysnka and Reed (2012) and Budzysnka and Witek (2014) the two kinds of conditions – the felicity condition of sincerity and the Gricean Maxim of Quality – have been bundled together into what they call ‘credibility’ and made into a speech-act condition, as if one could not be sincere without having evidence. For example, according to Budzysnka and Witek (2014, p. 6)

the felicity of an assertion that p presupposes that the speaker knows something about the domain to which p belongs. … . We will assume that the felicity of an illocutionary act presupposes in Austin's sense that the speaker has an appropriate non-defective character or … an appropriate status function.

Unfortunately for what they say here, credibility is not a felicity condition, nor does it make much sense to say that it is presupposed by the felicity of the assertion.

Firstly, the condition of satisfaction for asserting that p is simply belief that p is true (Searle, 1979, p. 20). It is a sincerity condition, and I am sincere when I believe what I say. But this cannot be equated with credibility. History has shown that people can be extraordinarily sincere in their beliefs no matter how completely incredible they are. (Take any religious zealot or fundamentalist as an example). Unfortunately, sincerity is no guarantee that you have reasons or evidence for what you assert, so the valid criticism that the speaker has no evidence does not literally mean that the assertion misfires. Turning to the Maxim of Quality, although this does demand that you have reasons or evidence, it does not demand that those reasons come up to any objective standard, so the valid criticism that the speaker's evidence is bad does not literally mean that the conversation has gone wrong on some higher textual level either. Given that the conditions of satisfaction for both the individual speech-acts and the conversation are all internal – that is to say, they depend only in having the right psychological states and not on anything objective – the fact that it is incredible need not be evidence of a misfiring illocutionary act or defective conversation.

Secondly, it is difficult to work out wherefrom they get this idea of Austinian presupposition. What Austin is saying at (1975, p. 51) is that the performance of some speech-acts, for instance, marrying two people together, depends on the existence of a conventional procedure that a duly authorised person can carry out on appropriate objects. For example, until recently in some countries, the speech-act of marrying two people would be void if those two people were of the same sex. Similarly if the procedure is carried out by a bartender. In these cases the act of marrying is void if these conditions are not satisfied, so a successful marrying presupposes that these things obtained. Perhaps this is what Budzysnka and Witek mean by being presupposed by the felicity of the speech-act. By calling this ‘presupposition’ Austin (1975, pp. 50–51) intends to liken it to cases of assertion when the referring terms do not refer to anything, which on his account are neither true nor false. A successful case of assertion presupposes that there are such referents, for otherwise no truth-claim is made, but it does not presuppose sincerity but implies88 it: ‘an assertion implies a belief'.

Perhaps the distinction between implying and presupposing (as I think Budzysnka and Witek intend the latter term) is hair-splitting; the important point against them is that neither an assertion itself, nor the fact that it is felicitous, either presupposes or implies that the speaker is credible. Only speech-acts that depend for their success on certain facts about the world presuppose or imply that those facts obtain. Also, there are plausibly speech-acts, similar in some ways to assertions, that have credibility as this kind of external condition of satisfaction, which credibility can be presupposed or implied by the existence of the (felicitously performed) speech-act (that is to say, it has not been rendered void). Possibly some kinds of argument from authority are like this. For example, such arguments could be thought to have a form something like: ‘I am credible. David is 50 years old. Therefore, you should take it for granted that David is 50 years old.’ This is a kind of practical argument, for it concludes with doing something or a demand to do something.

Budzynska and Reed's idea seems to be that ad hominem attacks on the credibility of an arguer is not attacking the inferential connection so much as it is attacking the illocutionary connection. I am saying that this is only literally true for the specific criticism that we have reason to think that the speaker is insincere. Such may be the case in the circumstantial ad hominem where the criticism is something like ‘You have been paid to give testimony for the defence so you cannot be considered impartial’ and the like. But is this undercutting any inference? I think not; what it implies is that we have made an error in interpretation rather than in inference, that is to say, the utterance is not an instance of the illocutionary act we took it to be an instance of, or at least not a felicitous instance of that act, because we no longer attribute to the speaker the psychological states required for the act's felicity conditions to be satisfied, so we must adjust our interpretation to saying either that we have the right act but that it is an infelicitous instance of such, or we must, proceeding perhaps according to the Principle of Charity, say that the utterance is an instance of another illocutionary act that does not require sincerity. In the particular case of circumstantial ad hominem mentioned above we may perhaps accuse the speaker of an illocutionary misfire; this is the interpretation we choose to make of her utterance. So, I agree that attacks on ethos are attacks on illocutions rather than inferences, and that Budzynska's basic idea is insightful. But she tries to generalise the point by making credibility and not just sincerity into a condition of satisfaction – a condition, moreover, of asserting. This just does not follow. Most of the time we cannot attribute insincerity to a speaker just because they talk rubbish. There must in these cases be a different rationale for adjusting our interpretation, and although I will not argue the point here, I think the rationale is provided by the fact that there are different principles of interpretation, connected to the Principle of Charity, that we can legitimately follow.

Furthermore, I think that there actually are occasions when we adjust our interpretation not because of what we think that the speaker thinks but because of what we, the interpreters, think of the speaker's argument. In other words, although the conditions of satisfaction are all internal for the speech-acts in issue, and so in principle our interpretation of an arguer's utterance should depend only on psychological states we attribute to the speaker, we do in fact adjust our interpretation anyway. Here is an example. Consider the position of the interpreter when he knows that the speaker's reasons for making a particular assertion are bad. Suppose that the speaker gives the following argument: all bakers make lots of dough, everyone who makes lots of dough makes lots of money; therefore, all bakers makes lots of money. I think the interpreter is likely to interpret the speaker as having equivocated on the word ‘dough', yet it seems to me quite possible that the speaker uses the term ‘dough’ in the same sense in both premises and does not realise that it is in different senses that his premises are justified by the evidence he has. If we interpret the speaker literally then there is no misfire in the assertion of either premise – he is both sincere and, from his own point of view, justified in giving this as an argument for his conclusion – so there seems to be nothing wrong with the illocutions. Also, the argument the speaker gives is valid, so there seems to be nothing wrong with the inference. We may even suppose that, as luck would have it, it is true that everyone who makes lots of dough in the baker's sense of ‘dough’ makes lots of money, so the argument is sound. Despite all these things I think we would still be inclined to say that a fallacy of equivocation has been committed, but in doing this we must interpret the premises in the way that we – rather than the speaker – know to be justified. When we do this we are attributing an insincere assertion to the speaker although, literally, he is both sincere and credible. I do not say that we must interpret the premises this way, but I say that it is permissible, and that by adjusting the interpretation this way we act charitably towards the charge that a fallacy has been committed and that the arguer has equivocated. If we choose the literal interpretation then no fallacy has been committed, and it is the charge that one has been committed that is fallacious, which obviously amounts to being uncharitable towards the charge. Whether a fallacy is committed, and who by, depends then on towards whom we choose to be charitable.

Let us reconsider Wilma's case, and let us suppose that we know Wilma to be unreliable, not because she is insincere, but because she is a poor evaluator of evidence. This, I pointed out, does not attack the illocution if we interpret the locution literally, because she is sincere and does not even need evidence in order to successfully perform the illocutionary act of asserting. But the point is this: should we interpret the locution literally? If we know that her evidence is poor, and perhaps she herself would realise this were it pointed out to her, could we not interpret her assertion as a misfire, even though literally it was not? And if she has no evidence (which, remember, assertions do not require) could not the failure to observe the Maxim of Quality be re-interpreted as an as-if insincerity? Isn't it charitable to her not to interpret her as asserting claims that we know not to be justified, especially when we know also that she has no evidence for them or that the evidence that she thinks she has is bad? If we do this, then criticism of her credibility does amount to an attack on the illocution rather than the inference. If we do not and choose the other interpretation, then it is an attack on the inference rather than the illocution, but then this attack misses its mark because it is a fallacy of relevance. In a sense, then, there is no fact of the matter whether some ethotic criticism is a reasonable attack on an illocution or an unreasonable attack on the inference.

Let us change the context slightly and suppose that Wilma is an expert witness, or at least that it is permissible to construe her as such given the context. Again, suppose that we attack her credibility. In taking this attack to be relevant (by being charitable towards the attacker), we must make an accommodation. We might interpret Wilma as making an insincere assertion, or we might, I suggested above, interpret her as making the kind of practical argument for which credibility is a genuine condition of satisfaction; that is to say, her speech-act could be seen as expressing the argument ‘I am an expert witness. Harry was in Dundee. Therefore, you should take for granted that Harry was in Dundee.’ But if we take this attack simply as not relevant (by being charitable towards Wilma), the ad hominem attack is simply a fallacy of relevance. Our having alternative interpretations open to us explains why we often have different intuitions on the subject.

My slightly surprising conclusion, then, is that for a wide range of criticisms it is actually indeterminate whether it is the illocution or the inference that is being attacked. What determines it is the decisions we make as interpreters and either interpretation is reasonable; it is not that one interpretation is right and the other wrong, though one may be more suited for a particular purpose than another (Botting, 2013).

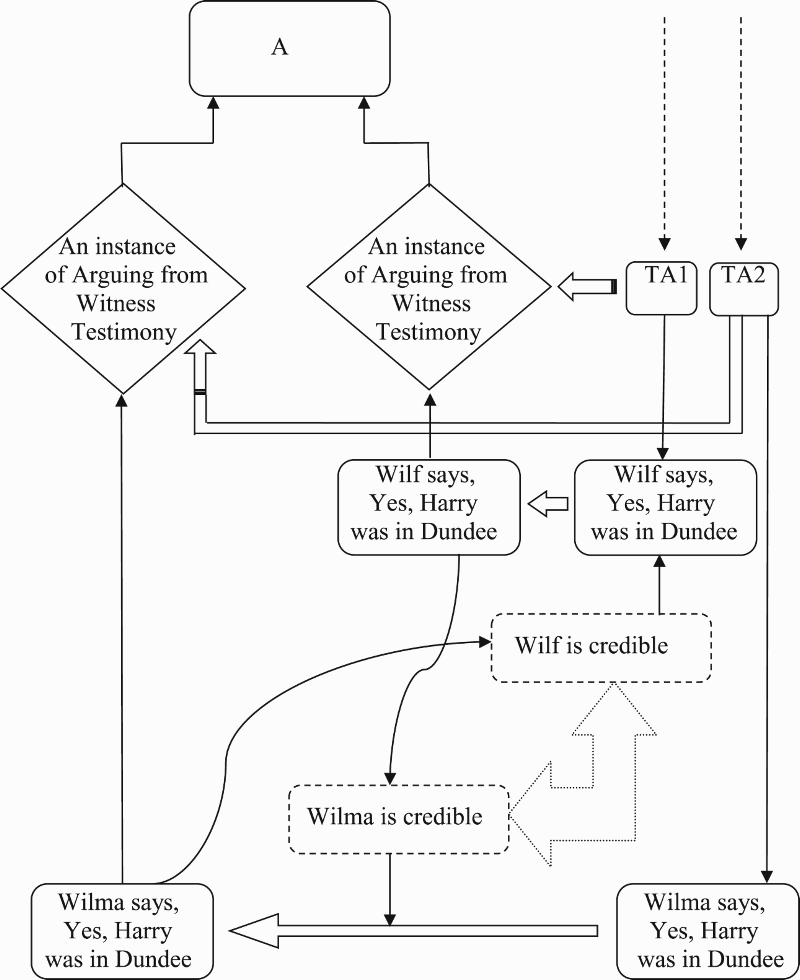

Consider now cases of corroboration with two witnesses given in Figure 3. The block arrow  has been used to indicate the illocutionary connection of assertion, the block arrow

has been used to indicate the illocutionary connection of assertion, the block arrow  to indicate the illocutionary connection of argument, and TA1 and TA2 are instances of Transition by Witness Response, with the precursors of the transition (namely, the illocutionary acts of questioning) not shown.

to indicate the illocutionary connection of argument, and TA1 and TA2 are instances of Transition by Witness Response, with the precursors of the transition (namely, the illocutionary acts of questioning) not shown.

Figure 3.

An example of corroboration.

We have two pieces of evidence in favour of A (namely, Harry was in Dundee). Thus we have two RAs (namely, the two instances of Arguing from Witness Testimony). However, if Wilma is credible then we have reason to analyse Wilma's locution as a successfully performed assertion that Harry was in Dundee, and this seems to support Wilf's credibility on the grounds that he has said the same thing. The more likely A is to be true, the more reason we have to think that the testimony was credible and that the witnesses were credible. The same thing goes for Wilf; if Wilf is credible then it is more likely that what Wilma said was true and justified, and thus that Wilma is more credible. These inferences are represented by the curved arrows, and one can imagine putting an RA in there called Arguing from Corroboration or such like. Note that we are not inferring A here. One can see, then, that in effect Wilma and Wilf, in corroborating each other's testimony, support each other's credibility. This is shown by the dotted double arrow. If this corroboration were the only reasons we had to take Wilma or Wilf as credible this would be extremely problematic, but provided that the credibility of Wilma or Wilf can be supported in some other way (and, in fact, in most contexts credibility is taken as a default assumption, as already said, so no more positive support is needed), there is no problem with this kind of mutual support. This support, though, is to the illocution rather than the inference – it does not make A better supported by the evidence as such.

Let me explain this a bit further. Suppose that in 9 out of 10 times that Wilma asserts something successfully, what she asserts is true. Suppose also that only 5 out of 10 times that Wilma says something, what she says is true. When she asserts something she also says it, but not everything she says is asserted by her: sayings are the wider reference class, assertings the narrower. We do not know from the propositional report of the locution whether Wilma is asserting or just saying, but we tend to assume that Wilma is credible and that her locution is a successful assertion. Therefore, relative to this evidence, the probability that what she asserts is true is 0.9, i.e. 9 out of 10. To adapt a popular model used in questions of probability, we assume, so to speak, that we are only picking from the urn containing assertions. We may be wrong about this and Wilma's locution may belong to the urn containing mere sayings, and in this case the probability is 0.5. These are different inferential strengths, depending on how credible we believe Wilma to be in this particular instance. The strengths are fixed by the frequency ratios and do not change. It is a mistake, for example, to reason in the following ways: ‘Wilma may be credible, but I'm not sure. Given my uncertainty, I should downgrade the inferential strength of the inference. Instead of saying that the probability of what she asserts being relative to the evidence that she has asserted it is 0.9, I will adjust it downwardly to, say, 0.8’ or, when Wilma has been corroborated, ‘I am more confident than I was before that Wilma is credible, so the inferential strength should be increased.’ What changes, instead, is how willing we are to bet on the outcome. What is increased when Wilma is corroborated, and decreased when she is rebutted, is our confidence about which urn Wilma's locution belongs to. So it is wrong to think of corroboration as giving as extra boost to the inference; what it does is reassure us that our interpretation of Wilma's locution as an assertion was positively justified and not just a default assumption.

What if the witnesses do not agree? What if Wilf says that he saw Harry in Aberdeen? Now we have doubts about the credibility of both witnesses, modelled here as an attack on the illocution of asserting. This is so, I would argue, despite the fact that we do not necessarily accuse one of the witnesses of being insincere. Literally, Wilma may well have successfully asserted that Harry was in Dundee (even if he was not), but in attacking the locution we seem to be saying that we can interpret her as not having done so. Although slightly curious, I think this is correct, and is what we do in many cases.

So, there is no problem in general with speakers supporting each other's ethos, and Budzyska does not suppose otherwise. Budzynska (2013) claims, however, that there is a problem with supporting our own ethos. She argues that this is a problematic form of circularity and should be viewed as problematic from the illocutionary rather from the inferential point of view. She is interested in cases like Bob said, I'm credible and Bob said, Ann said I'm credible. The problem, she claims, is that if Bob is not credible then his asserting ‘I'm credible’ cannot be relied upon and provides no evidence in favour of his credibility, since credibility must be presupposed for people's utterances to qualify as evidence that what they say is true. Equally, there is no reason to suppose on the basis of Bob's saying ‘Ann said I'm credible’ that Bob is credible unless we can suppose this to be true on the basis of Bob's credibility, which is precisely the point in question, or unless we can establish that Ann actually did say this and that Ann is credible, in which case we have a case of mutual corroboration that I have just said is not generally problematic. As before, ethos is here modelled as a condition on the illocution and is not argumentative. It is, Budzynska says, a circular assertion: the content of the assertion refers to the ethotic condition of the assertion. It is a non-argumentative, non-inferential kind of circularity, but is equally problematic, and for analogous reasons; we have no better reason for believing Bob after he says ‘I am credible’ than before.

It is not clear to me what exactly is wrong or problematic about this circularity. Of course, her thinking that credibility is a condition on asserting infects her discussion here too, but let us put that aside, for there are other problems more specific to what she is claiming here. For one thing, we do sometimes say things like ‘I'm credible', for instance when we say ‘I swear by Almighty God to tell the truth, … ’ etc. For another thing, suppose that it were some other condition of the speech-act being asserted; suppose Bob says ‘Normal input and output conditions obtain for this utterance', which condition applies to any speech-act whatsoever. If this condition does not obtain, then it would be a pure fluke if we managed to understand Bob; hence, it was a kind of pointless thing for Bob to say. There is a kind of circularity here too, but I do not find it obvious that there is anything problematic about this beyond a certain redundancy.

6.Conclusion

Argumentation is a complex of speech-acts regulated by dialogue rules. If some of these acts do not exist then there is no argumentation, and if they do exist but contravene the rules for argumentative dialogue, then the argumentation exists, but is faulty. In this case, the contravention of the rule may also mean that the act contravening it is faulty because one of its conditions of satisfaction is that the utterance it is related to is appropriate; plausibly, this is true for the act of reply, because for this to be a successful illocutionary act of replying it must be a reply to another illocutionary act, and be believed by the speaker to be relevant to that illocutionary act. Some illocutionary acts are relational in this way, as Searle says. Such an utterance will be simultaneously an assertion, say, and a reply.

Possibly, this is true for the illocutionary act of arguing too. I am not convinced of this, seeing it more as relational to a proposition rather than to an utterance, on the grounds that I do not think my act of arguing can fail on the grounds that there is no surrounding dialogue – if it were actually a condition of satisfaction that it be related to an utterance, and there is no such utterance, then my act of arguing would be a misfire or even be void, and I do not think this is true. The fact that we may not be able to tell what I am arguing in favour of without the contextual cues given by the surrounding dialogue is irrelevant here, for all speech-acts whatsoever need context in order to determine their force and content, and this does not make their force or content ‘extrinsic features'. However, for the sake of argument, let us suppose that this is true; let us suppose, that is, that arguing and replying are on a par and are relational in the same way.

Budzynska and Reed's real innovation, and where I think they go wrong, is in saying that the illocutionary act of arguing, or whatever they want to call the illocutionary act that anchors the inference, is not performed when the speech-act of asserting is; they seem to have some ambivalence towards the idea that a locution can simultaneously be an instance of more than one illocutionary act.99 It does not actually matter here in what way we take the speech-act of arguing to be relational, since in either case the act is instantiated by the locution, and it is on this act that the inference is anchored and at this moment that any invitations to inference are passed out. In some cases the act may be instantiated indirectly, but there is nothing ‘implicit’ in this act in the sense of an act that occurs not when a locution is performed but in the transition between locutions. Whatever illocutionary acts we analyse a locution as instantiating, they are instantiated when the locution occurs.

Budzysnka and Reed are aware of this innovative aspect of IAT. It goes not only beyond speech-act theory but also from Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT, Asher & Lascarides, 2003, 2011) from which they borrow the notion of dialogue glue. But this seems a misappropriation. SDRT is a theory about how we reason about what each other are saying and construct interpretations thereof during a dialogue; hence, it pertains only to the trivial sense in which speech-acts may be ‘relational’ to each other. This seems to show that there is general confusion in IAT in how speech-acts may be related to each other.

Budzysnka et al. (2014, pp. 918–919) appeal to rhetorical questions as a motivation for making this innovation. Suppose the locution is ‘Or was it typical?’ Of what kind of speech-act is this an instance? On the surface, it is an instance of questioning, but given that it is uttered as a rhetorical question, it might instead be interpreted as asserting ‘It [whatever this refers to] was typical.’ This is offered as a Searle-type analysis of the situation. Yet they are sceptical of this kind of response, asking why, if it is to be interpreted as an assertion, the speaker does not just make an assertion. Why argue in this indirect way by asking rhetorical questions? They answer this question by noting that the speaker may, by asking rhetorical questions, find it easier to withdraw if challenged – there are different rhetorical features connected with making assertions directly and indirectly by asking rhetorical questions. Thus, it would be wrong to analyse away its surface appearance of asking a question, because it is part of the speaker's intention to use this form. They say (Budzysnka et al., 2014, p. 19):

What we need is to be able to identify the assertive intentions behind such questions. Only then can we assemble the parts of the argument and attempt to model their composition into large structures. As far as we are aware, there is no model which would allow the representation of such double (asserting and questioning) function of utterances.

However, there is one part of their analysis that I find insightful, and that is the idea that attacks on credibility and ethotic status can be construed as challenges to the conditions of satisfaction of the illocutionary act; although I think that this is far more problematic for orthodox speech-act theory than they suppose, I contend that there is something right about this, and that a general analysis of ad fallacies along these lines might be essayed.

Notes

1 In Reed's (2011, pp. 2–3) words, the model shows how the various moves in dialogue navigate the inferential structure and how the inferential structure constrains the dialogue.

2 See Reed (2011, pp. 7–8). Budzysnka and Reed (2011, p. 5) say this: ‘We can associate different parts of the dialogue with those implicit speech-acts and thereby the rule applications.' Since they do not mention inferences here, this is probably less objectionable, but it still contains what I consider to be a mistaken notion of implicit speech-acts, and these are elsewhere linked to inferences.

3 My view (2013) was that, when you took a criticism as attacking ethotic elements of the conditions of satisfaction, this amounted to deciding to use the Principle of Charity in a certain way; we could accuse a speaker of insincerity even when she was not.

4 Note that not all illocutionary schemes (the IF's) are connected to transition applications. All rule applications – that is to say, inferences – do seem to be connected to a transition application, through a particular illocutionary scheme. It would not really matter, though, if it were only some and not all inferences.

5 It might be argued that there could still be a relation to the propositional report that Wilma said ‘Why?', but since in this case the propositional report is false I doubt that Budzynska and Reed would like to take this course. I think we are meant to assume that the propositional reports are all true and report real and not imagined locutions.

6 If someone asks me ‘Is p the case?' and I reply ‘Yes' or ‘p' I am not providing an argument that p, except possibly the trivial circular one.

7 It is worth noting that I can indirectly perform a speech-act without saying anything. If somebody asks me the time I can direct their attention to the clock on the wall, and if someone asks me the current whereabouts of Harry I can answer by pointing to Harry. In asking a question I can ‘point' or direct a third party's attention to the speech-act that is a response to it. This is essentially what happens here. The questioner elicits the evidence and points to it. When summing up a case for a jury, a barrister or judge will remind them of this evidence by giving a propositional report of the locution, e.g. ‘Witness X testified under oath that p.'

8 This is a sense of ‘implies' given by Moore sentences. It makes no sense to say ‘p, but I do not believe that p'; hence, my saying ‘p' ‘implies' that I believe that p.

9 I say ‘ambivalent' rather than ‘ignorant’. I think that Reed and Budzynska are aware that more than one illocutionary act can be instantiated at once, and they are certainly aware of indirect speech-acts, but for some reason are reluctant to formulate their diagrams this way.

10 The exception might be where the communicative intentions associated with the different illocutionary forces actually conflict.

Conflict of interest disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

1 | Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. ((2003) ). Logics of conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

2 | Asher, N., & Lascarides, A. ((2011) ). Reasoning dynamically about what one says. Synthese, 183: (1), 5–31. |

3 | Austin, J.L. ((1975) ). How to do things with words, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

4 | Botting, D. ((2013) ). Interpretative dilemmas. In D. Mohammed & M. Lewinski (Eds.), Virtues of argumentation. Proceedings of the 10th international conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (Windsor; ON: OSSA) (pp. 1–14). |

5 | Budzysnka, K. ((2013) ). Circularity in ethotic structures. Synthese, 190: , 3185–3207. |

6 | Budzysnka, K., Janier, M., Reed, C., Saint-Dizier, P., Stede, M., & Yakorksa, O. ((2014) ). A model for processing illocutionary structures and argumentation in debates. Retrieved from http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2014/pdf/77_Paper.pdf |

7 | Budzysnka, K., & Reed, C. ((2011) ). Speech acts of argumentation: Inference anchors and peripheral cues in dialogue. Computational models of natural argument: Papers from the 2011 AAAI workshop. Retrieved from www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/WS/AAAIW11/paper/download/3940/4244 |

8 | Budzysnka, K., & Reed, C. ((2012) ). The structure of ad hominem dialogues. COMMA. Retrieved from www.arg.dundee.ac.uk/people/chris/publications/2012/comma2012adhd.pdf |

9 | Budzysnka, K., & Witek, C. ((2014) ). Non-inferential aspects of ad hominem and ad baculum. Argumentation. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10503-014-9322-6 |

10 | Reed, C. ((2011) ). Implicit speech acts are ubiquitous. Why? They join the dots. In Zenker (Ed.), Argument cultures: Proceedings of the 8th international conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation. Retrieved from www.arg.dundee.ac.uk/people/chris/publications/2011/ossa2011.pdf |

11 | Reed, C., & Budzysnka, K. ((2010) ). How dialogues create arguments. In Frans van Eemeren, Bart Garrsen, David Godden, and Gordon Mitchell (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th international conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (Ronzenberg/Sic Sat). Retrieved from www.arg.dundee.ac.uk/people/chris/publications/2011/issa2010.pdf. |

12 | Searle, J. ((1979) ). Expression and meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |