“You’ll find most people who got involved with the Café couldn’t do without it now” – Socialising in an online versus in-person Aphasia Café

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

People with Aphasia (PwA) experience detrimental consequences post-stroke which can result in limited opportunities for social engagement and poor psychosocial ramifications. Peer support can improve psychosocial outcomes. Unfortunately, Covid-19 related social restrictions resulted in the closure of social outlets for PwA, further exacerbating social isolation. Some social networks transitioned online during this period. One such network was the Aphasia Café, a social group for PwA, supported by Speech and Language Therapy students (SLTS).

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to investigate the experiences, knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about the Aphasia Café (in-person and online), within the context of pandemic-related social restrictions, from the perspectives of PwA and the SLTS who support them.

METHODS:

16 SLTS participated in one of five focus groups. Six PwA were individually interviewed. Semi-structured questionnaires facilitated inductive and deductive data collection which were analysed using Framework Analysis.

RESULTS:

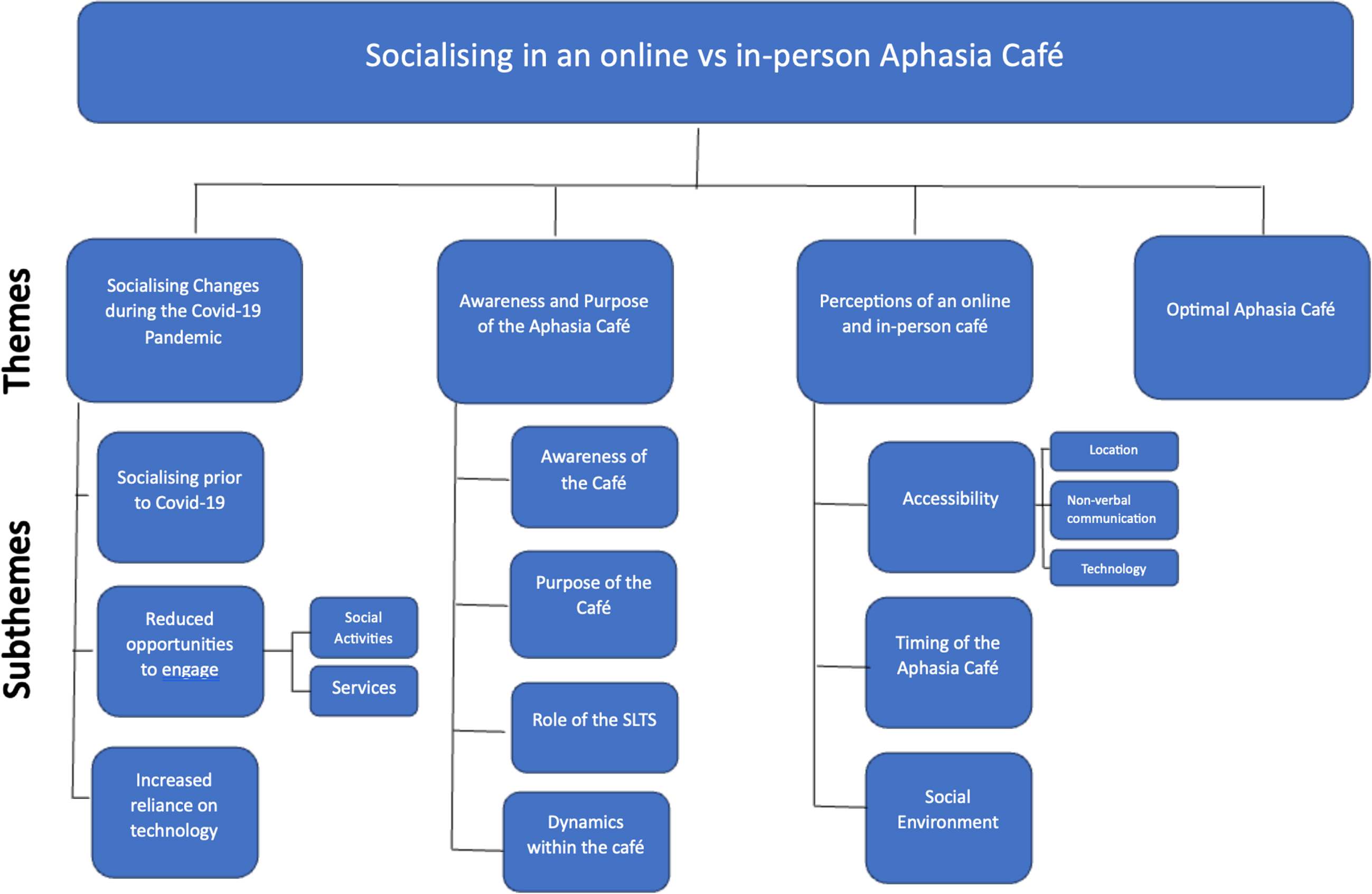

Observed themes related to the in-person and online Aphasia Café will be reported in this paper. Overarching themes observed from both SLTS and PwA include: ‘Socialising changes during Covid-19 pandemic’, ‘Awareness and Purpose of the Aphasia Café’, ‘Perceptions of an Online and In-Person Aphasia Café” (subthemes –accessibility, technology, time/timing, non-verbal communication, and social environment), and ‘Optimal Aphasia Café’ (PwA only).

CONCLUSIONS:

This study provides a unique perspective on the delivery of a supported informal conversation group from both PwA and the SLTS who facilitate it. Both online and in-person social spaces were considered to enhance the quality of life for PwA and give valuable experience for SLTS.

1Introduction

Aphasia, commonly acquired post-stroke, is predominantly discussed in relation to disrupted language function impacting literacy, and comprehension and expression of the spoken word (Fridriksson & Hillis, 2021). However, recent research argues that the consequential negative social participation impact arising from aphasia, such as social exclusion, isolation, and depression, have equally profound ramifications as aphasia itself (Moss et al., 2021). Compared to people without post-stroke aphasia, people with aphasia (PwA) are at higher risk of detrimental psychosocial outcomes such as poor self-perception, social isolation, and loneliness (Kristo & Mowl, 2022). Baker et al. (2019) report that post-stroke PwA self-reported negative mood changes and trauma related to their communication impairment, regardless of a formal diagnosis of depression. The incidence of depression for PwA is 62% -70% and markedly higher than people post-stroke without aphasia (Lincoln et al., 2012) provoking a retreat from social engagement (Northcott & Hilari, 2011). PwA are reported to have on average nine fewer social contacts and three fewer social activities than their non-aphasic peers (Cruice, Worrall & Hickson, 2006). This can be attributed in part to the central role communication plays in building and maintaining relationships (Croteau et al., 2020).

2Social engagement

The value of friendships (Brown et al., 2013) and meaningful relationships (Ford, Douglas & O’Halloran, 2018) can positively impact the wellbeing of PwA and the potential benefits of peer-befriending may foster a supportive communicative environment (Dalemans, de Witte, Wade & van den Heuvel, 2010). Studies have explored in-person peer-led (Tregea & Brown, 2013) and online peer-supported (Pitt et al., 2019) groups for PwA. Benefits in attending such groups include forging social connections (Ross, Winslow, Marchant & Brumfitt, 2006) and gaining opportunities to practice communicating with others with similar experiences (Northcott et al., 2022). Peer-befrienders with aphasia view their role as a way to improve the lives of others, while also reclaiming facets of their own pre-stroke identities (Northcott et al., 2022). Peer-befriending initiatives also highlight the reciprocal advantages of these relationships, where both the befriender and befriendee within the dyad report mutual benefits (Moss et al., 2021). Skea et al., (2011) attribute this in part to the “upwards” and “downwards” comparison these group settings afford, where PwA have the opportunity to interact with those whose abilities are greater or less than their own. Cruice et al (2020) highlight that engagement in online conversation groups has increased quality of life and confidence for PwA, using technology to reduce psychosocial impacts of aphasia. According to PwA, rehabilitation goals to improve communication and enhance social engagement should be prioritised by service providers (Cruice et al., 2020). Current research is exploring how these goals may be maximised through the use of in-person (Lo & Chau, 2023) and online groups (Cruice et al., 2020).

3Aphasia Café

The reported benefits of social engagement for PwA and the lack of available resources motivated the establishment of an informal conversation group called the Aphasia Café. This initiative was founded in 2017 by SLT Rachael Boland, UCC Clinical Therapies Society, and author, Dr Helen Kelly. It aimed to provide a supported environment at a local café, for PwA to socialise with each other while practicing conversation. Supports included aphasia-accessible menus, materials to assist total communication, and SLT students to facilitate conversation when needed. The café environment was adapted to support successful communication, for example, staff were trained in communication skills by PwA, accessible menus were visible on the counter and background music was lowered to reduce distractions.

4The Covid-19 Pandemic

Rapid outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2, also known as the novel coronavirus disease or Covid-19, led the World Health Organisation (WHO) to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in January 2020 which was subsequently declared a pandemic in March of that year (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020). The period between February and July 2020 was considered the “first wave” of the pandemic in Ireland. In line with recommendations from The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and The National Public Health Emergency Team the Government of Ireland implemented several societal interventions to limit the spread of the virus (Conway et al., 2021, Kennelly et al., 2020). These community mitigation strategies included the closures of schools, workplaces, and non-essential services (Conway et al., 2021), social distancing, and travel restrictions (Regmi & Lwin, 2021). Those infected with the virus were recommended to isolate, while exposed persons were recommended to quarantine (Regmi & Lwin, 2021).

Unfortunately, social restrictions during Covid-19 significantly limited social interactions prompting people to search online for opportunities to socialise. The use of technology may support PwA to gain independence in their daily lives, increase social networks, facilitate self-management (Kelly et al., 2016), and provide peer-support for PwA (Nichol et al., 2022). Video conferencing platforms facilitate non-verbal interactions such as gesture and facial expression to communicate more effectively (Cruice et al., 2020; Caute et al., 2022). Challenges to successful online interactions include technological difficulties, excluding those with limited access to technology (Menger, Morris & Salis, 2019), communicating in a less authentic setting, poor internet strength and familiarity with the chosen platform (Caute et al., 2022). Online interactions can be particularly difficult for PwA (Kearns & Cunningham, 2022) presenting an additional hurdle to communication interactions for many (Neate et al., 2022). When surveyed, Speech and Language Therapists identified challenges such as functionality of buttons and menus, and usability in relation to PwA’s cognitive and physical needs (Cuperus et al., 2022). Menger et. al. (2019) found 64% of PwA identified communication impairment as a barrier to learning or enhancing Information and Communications Technology (ICT) skills, whereas participants without aphasia did not identify their stroke as a barrier. Although technology offers increased opportunities for communication, personalised education with follow-on support is necessary to enhance PwA’s ability to engage successfully with technology (Kelly et al., 2022; Kelly et al., 2016). Despite evidence suggesting the benefits of targeted social inclusion for PwA, few studies have captured their experiences of attending online peer-support groups, what PwA identify as important elements of peer-support and social opportunities (van der Gaag et al., 2005; Caute et al., 2022), nor the views of the group facilitators to ensure continuity and quality (Pettigrove, et al, 2021). An exploration into the potential impact of the pandemic on the social habits of PwA is an important aspect of this study. However, given the magnitude of social restrictions experienced by the whole population in Ireland at the time, it was essential to ensure that assumptions weren’t being made about the impact on PwA that were also experienced by others in the population. Working within our time constraints and unique environmental experience of the Aphasia Café, we recruited SLTS who were experienced in working with PwA but who also experienced social restrictions at the time. While appreciating differences in this population it allowed us to examine if there were potential similarities or distinct differences related to the impact of Covid-19 on social patterns of PwA.

As the Aphasia Café moved to an online format in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the aim of this study was to investigate the experiences, knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about the Aphasia Café (in-person and online), within the context of pandemic-related social restrictions, from the perspectives of PwA and SLTS who support them. Our research questions are:

1. What was the impact of social behaviour changes experienced by PwA and SLTS as a result of pandemic-related social restrictions?

2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of attending an online compared to in-person Aphasia Café, from the perspectives of PwA?

3. What are the advantages and disadvantages of attending an online compared to in-person Aphasia Café, from the perspectives of SLTS?

4. What would encourage SLTS and PwA to attend an Aphasia Café?

5. What would an ideal Aphasia Café look like from the perspectives of PwA?

5Methods

This research was initially planned to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of PwA and SLTS in relation to the in-person Aphasia Café. However, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, this research pivoted to include the online café in the first months of its establishment. Multi-perspective designs in qualitative research are emerging as ways to combine two or more focal perspectives to consider a phenomenon’s interpersonal, intersubjective, and microsocial aspects (Larkin, Shaw & Flowers, 2019). This research captures the experience of directly related groups (namely, PwA and SLTS) that are immersed in the same environment or involved with the same phenomenon, but that are likely to have distinct perspectives on it.

6Recruitment

As the online café was in the early days of its establishment, and in-person meetings were not possible considering Covid-19 restrictions, participants who had experience of the in-person café and/or online café were recruited. We were also approached by PwA and SLTS who had not attended either café but wished to participate. In this situation, participants were required to (i) have a basic understanding of the purpose and aims of the Aphasia Café, for example, awareness that it was an informal conversation group rather than a formal therapeutic intervention and (ii) experience of online service engagement, for example, PwA with experience in accessing online supports, and SLTS with experience of providing online aphasia supports (e.g., teletherapy or online simulation exercises).

A convenience sample of PwA (n = 6) and SLTS (n = 16) were recruited via email, social media and at Aphasia Café meetings. Going online expanded the recruitment to participants outside the geographical limits of the in-person café. There were no limitations in respect of age, gender, aphasia type or severity. As this Aphasia Café was a unique service in Ireland and given the recency of the establishment of the online Café, we did not have a maximum limit of participants.

7Inclusion criteria

Both cohorts were eligible if they were aware of the in-person and/or online Aphasia Café.

7.1People with Aphasia

(i) PwA≥18 years of age, with self-reported diagnosis of aphasia (excluding Primary Progressive Aphasia), (ii) able to give informed consent through aphasia-accessible information sheet, consent process and materials and could communicate with the interviewer using a total communication approach, (iii) PwA who did not attend the online café but had previous experience of accessing online aphasia supports.

7.2SLT Students (SLTS)

(i) SLTS who did not attend the online café but had experience of engaging in online support for PwA, for example, teletherapy or online clinical practice simulated learning experiences.

8Data collection

Focus group interviews (2-4 participants) with SLTS and individual interviews with PwA were facilitated by SB or AH. Each SLTS focus group (mean ∼47mins; range ∼25 mins - ∼104 mins) and PwA interview (mean ∼38 mins; range ∼25 mins - ∼73 mins) required one meeting apart from one participant who needed two. As the research took place during pandemic lockdown, video and audio recorded data collection were conducted online. Protocols optimised online safety - each participant had a unique meeting code and meetings were locked following entry. Written consent was obtained and again verbally at the start of the meeting. The Framework Method (Gale et al., 2013) was considered an appropriate methodological approach for this study which has been used successfully by previous research with this population (Kelly et al., 2016; Law et al., 2010; Parr, 2007; Wade et al., 2003). Semi-structured interviews were conducted by SB and AH from a pre-established topic guide (Appendix I, Appendix II). Participants were asked questions regarding demographic information, how they socialised before Covid-19 and any impact of Covid-19. They were also asked about their opinions regarding the in-person and online Aphasia Café, and the social needs of people with aphasia in Ireland. Students were additionally asked to describe what they consider to be the role of the SLTS in supporting PwA within the Aphasia Café.

9Data analysis

Semi-structured questions facilitated data collection of pre-established themes (deductive) and generation of themes from the data (inductive) (Gale et al., 2013). The necessity for pre-established themes in alignment with the aims of the research lies in providing a structured framework for data analysis, ensuring focused exploration of predetermined concepts and objectives (Gale et al., 2013), namely the ‘perceptions of the online and in-person café,’ ‘socialising changes during the Covid-19 pandemic’, and ‘participant perspectives on an optimal aphasia café’.

However, the dynamic nature of Framework Analysis allows for unexpected themes to be observed in the data, which for our study, resulted in the additional theme of ‘awareness and purpose of the café’. A seven-step protocol was followed:

1. Transcription: data was initially transcribed using otter.ai. and reviewed independently by SB and AH to confirm accuracy. Non-verbal communication was excluded unless deemed contextually appropriate.

2. Familiarisation with the dataset: through reading and re-reading transcripts. SB and AH independently maintained research journals related to the dataset identifying areas for discussion with the research team.

3. Coding: transcripts were coded independently by SB and AH to identify emergent patterns and noteworthy concepts which reflected the views of participants in relation to the research questions.

4. Developing a working framework: SB, AH and HK compared emergent trends across the dataset ensuring all data was adequately represented.

5. Applying the analytical framework: final codes from the working framework were accepted as the analytical framework and applied to all transcripts independently by SB and AH. SB, AH and HK reviewed and confirmed codes were applied accurately across datasets.

6. Charting the data into framework matrix: agreed coding was charted into separate matrices by SB and AH, with one matrix dedicated to each dataset with associated quotations from each transcript representing core themes.

7. Interpreting the data: data in the matrix were interpreted by SB, AH and HK in the context of the research questions. Emergent themes were noted throughout the analytic process for further discussion within the research team. Similarities and differences in each corresponding theme for the PwA and student datasets were identified and considered.

To ensure credibility throughout the research, SB and AH employed reflexive processes such as the maintenance of reflexive research journals, peer debriefing sessions, and independent coding prior to framework development. These reflexive processes also ensured confirmability of the research, as they provided opportunities for the researchers to examine their own biases and predispositions.

10Ethical considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Social Research Ethics Sub-committee (CT-SREC) at University College Cork. The researchers are qualified speech and language therapists, with experience in carrying out research with vulnerable populations such as aphasia. All participants with aphasia were experienced in engaging with the Aphasia Café online and/or online teletherapy. Participants were able to engage in the informed consent process and were made aware that they could pause and/or withdraw from the study at any point, and/or remove their recordings up to 2 weeks following the interviews. Participants were also given the option of completing interviews over more than one session if they wished.

11Findings

11.1Participants

Six PwA, 1-6 years post-stroke (4 Male: 2 Female; aged 38-69; mean age 53.2), participated. One PwA had attended both the online and in-person Aphasia Cafés, three attended the online café only and two had not attended either café.

Sixteen SLTS (16 Female; aged 20-29; mean age 21.63) in the final two years of their studies participated. Five students attended both online and in-person Aphasia Cafés, five attended the online café only, two attended the café in-person and four had not attended either café.

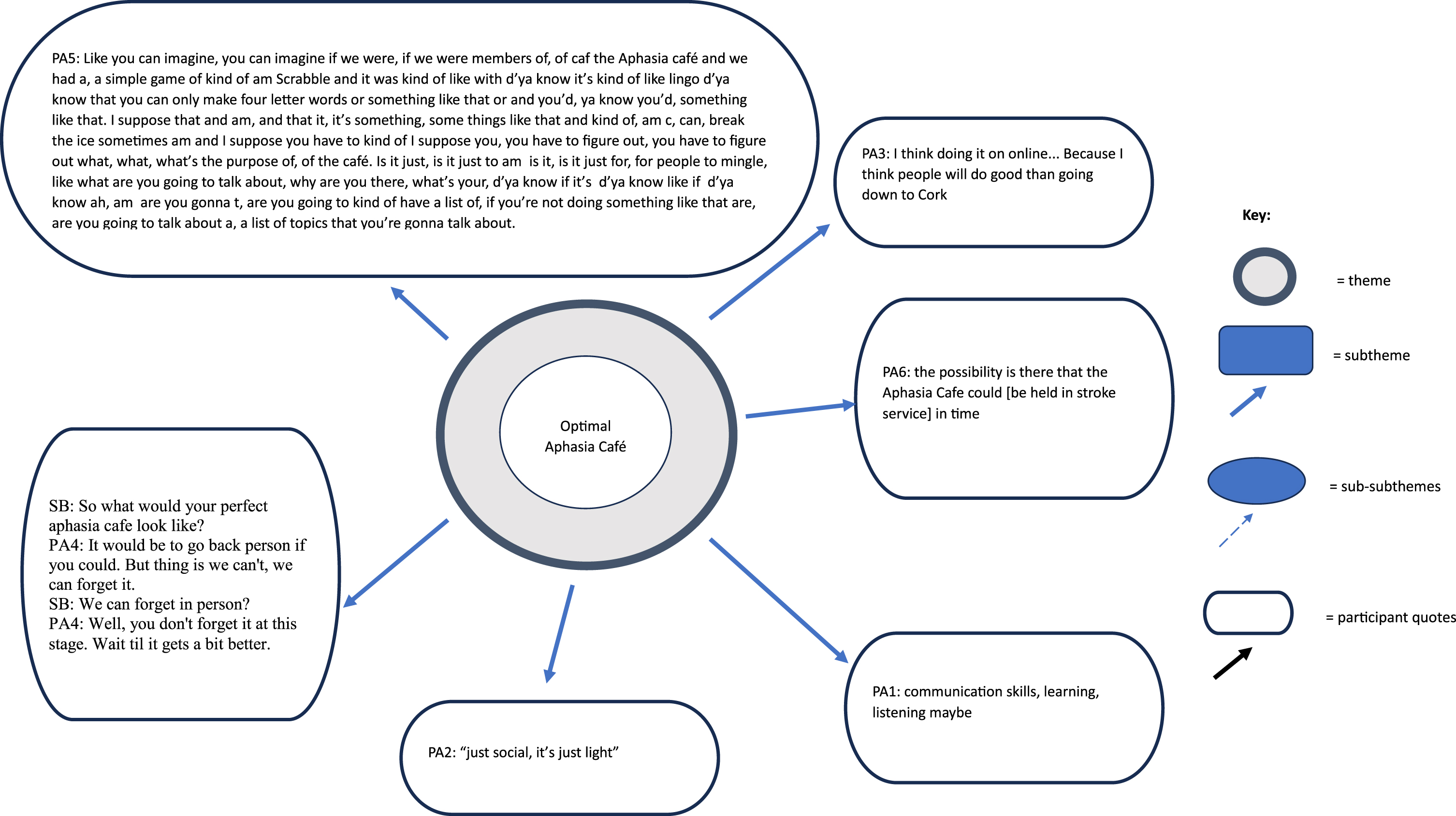

Themes related to the perspectives of online and in-person Aphasia Café are presented in Fig. 1 and will now be described. Themes observed (inductive) included ‘Awareness and Purpose of the Aphasia Café’, alongside the pre-established (deductive) themes of reflection on ‘Socialising changes during the Covid-19 pandemic’, ‘Perceptions of an online and in-person café’; and participant perspectives on an ‘Optimal Aphasia Café’ (Fig. 1, Appendix III-VI).

Fig. 1

Themes and Sub-Themes identified.

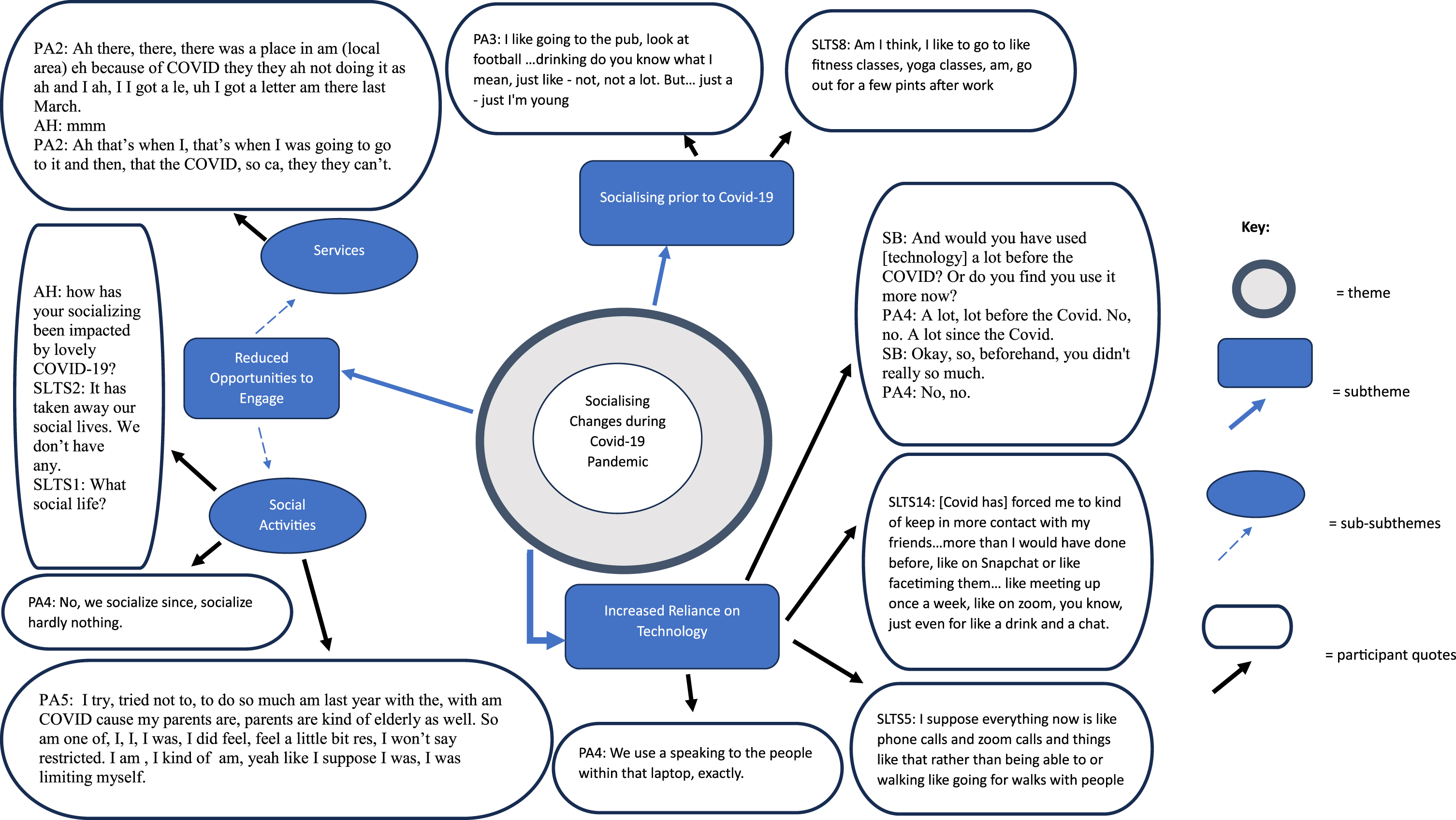

12Socialising changes during the Covid-19 pandemic

Participants deliberated about how opportunities and ways of socialising had changed for them during the pandemic. Specifically, subthemes of ‘Socialising prior to Covid-19’, ‘Reduced opportunities to engage’ (particularly, ‘social activities’ and ‘services’), and ‘Increased reliance on technology’ were discussed in relation to this theme.

PwA reported that prior to Covid-19 social interactions were primarily in person, engaging in social activities with friends and family such as walking (PA4), going to cafés (PA1), “going to the pub” and “betting” (PA3). Similarly, SLTS’ social interactions were mainly in-person, “like public parks, em restaurants ... gastropubs...even like going to your friends’ houses, calling up for a cup of tea” (SLTS9). This was echoed by other students, who discussed a spontaneous element to socialising “you go in and ... you’ll have lunch with whoever else is there. And now there’s none of that” (SLTS15).

Participants discussed reduced opportunities to engage with services and social activities as a direct result of Covid-19 restrictions. PA2 noted the reduced availability of services “because of Covid, they, they, ah, not doing it” and PA6 “even though I’m back driving, there’s nowhere to drive to”. In light of social restrictions, the online Aphasia Café was considered an alternative social opportunity for PwA reducing the need to consider frequent changes in public safety recommendations (PA4, PA6). This was echoed by some SLTS “while we can’t have our regular kind of socialisation ... it doesn’t mean the connection has to stop...you can adapt” (SLTS10).

Both PwA and SLTS reported significant changes to socialising behaviours due to pandemic restrictions placing technology forefront in attempts to maintain social connections. PwA reported using Microsoft Teams, Zoom, Facebook and WhatsApp whereas SLTS used Snapchat and Facetime. While five PwA reported using technology frequently for work or pleasure, all six noted an increased dependency on technology for socialisation since pandemic restrictions. PA3 commented, “It’s not the same cos of Covid... I talk to them on the phone”. PA6 discussed increased reliance on technology to maintain social contact stating “my only outlet now socially to be honest, is through what we’re on at the moment”. This was echoed by PA1 who contacted friends and family by “talking Zoom call or messaging or, WhatsApp”. SLTS reported a reduction in their social contacts “If it wasn’t for Covid, I wouldn’t be trying to, you know, reduce contacts” (SLTS15). Some reported “you have absolutely nothing to talk about because no one’s doing anything” (SLTS13) with others “gotten used to being able to spend time at home ... in our own company” (SLTS6).

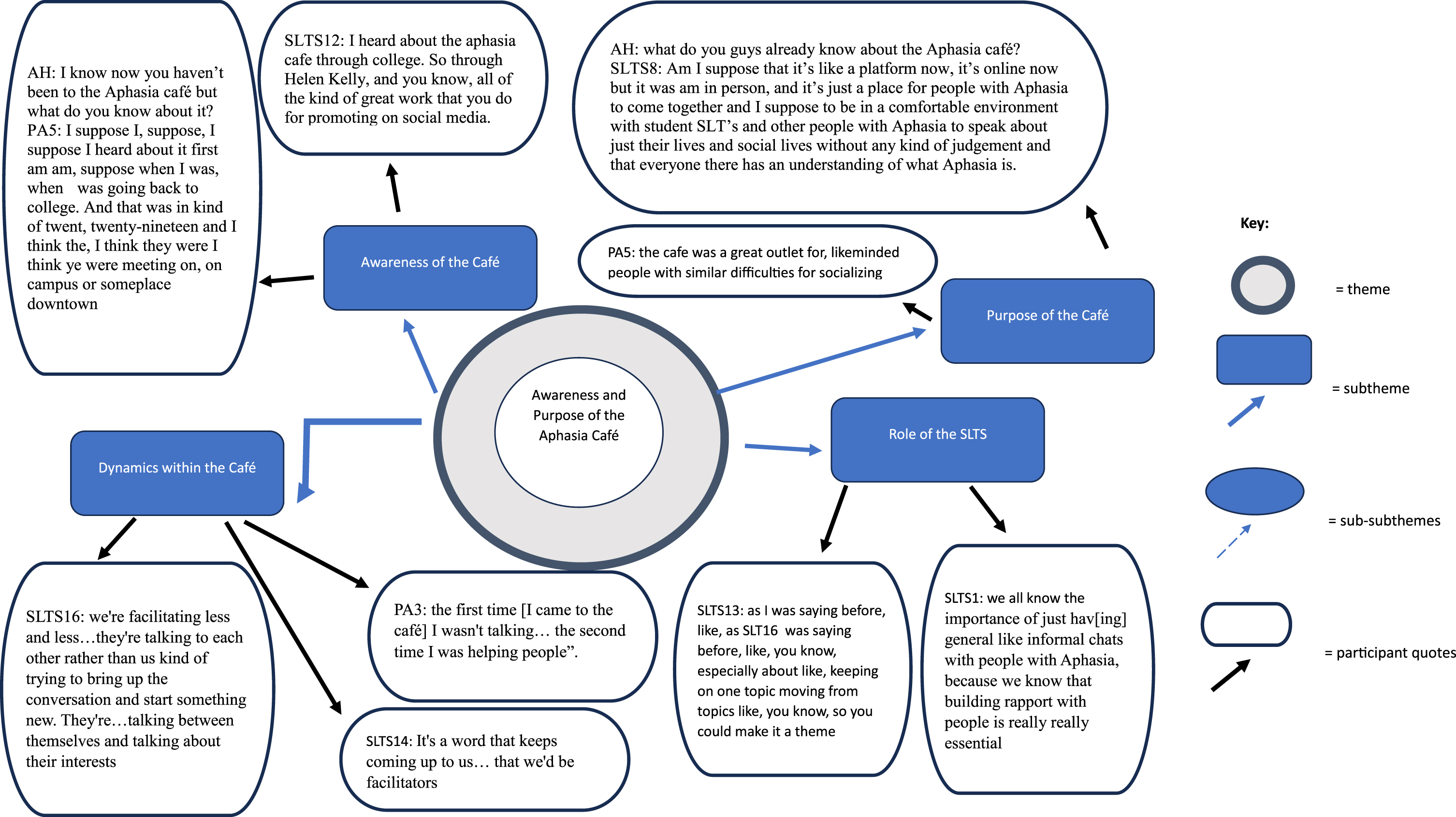

13Awareness and purpose of the Aphasia Café

Participants were asked about their awareness and understanding of the purpose of the Aphasia Café. The following subthemes will be discussed in relation to this theme - ‘Awareness of the Café’, ‘Purpose of the Café’, ‘Role of the SLTS’, and the ‘Dynamics within the café’.

All participants had heard about the Aphasia Café. SLTS reported hearing about it from PwA attending other services “one person came in and said they’d gone to the Aphasia café...someone else was like oh maybe I’ll go to that” (SLTS5). However, SLTS highlighted a lack of public awareness may prevent PwA from attending “when you have SLTs and even student SLTs recommending it I think they might be more ... inclined to go” (SLTS8). SLTS5 concurred “Yeah, I think just more awareness about it. I’d say there’s so many people with Aphasia who just don’t know about it”. SLTS10 highlighted “it’s so easy to just share a post [on social media] then all of a sudden ... people who follow me have seen it, and then...people who follow someone else has seen it...even ... one person, that’s one person the word has gotten out to that it wouldn’t have otherwise”. SLTS7 raised the importance of clarity around expectations of an online café “there might be a slight misconception that it’s more gonna be like group therapy em but in fact when you attend it then you realize that it’s just a general conversation”.

PA1 had been involved since the inception of the Aphasia Café and had attended in-person and online “four years... went to see the students... café”. PA4 had attended a local in-person aphasia café once before lockdown but had little opportunity beyond this to socialise with other PwA as “there wasn’t many people with aphasia, where I lived”. The four PwA who attend the Aphasia Café revealed this as their primary outlet for socialising with other PwA. Those who had not attended the Aphasia Café, reported that the primary avenue for meeting other PwA were general stroke support services such as “a group thing in [service]” (PA5), or local stroke support group where “people...in the stroke group would be suffering from aphasia” (PA6). PwA described the Aphasia Café as a place to socialise, with PA2 adding it was “to hear everybody’s problems”. PA1 noted the opportunity to practice “communication skills [and] learning” and PA6 found the café as “a great place to build a person’s self-confidence” rather than for speech and language therapy.

SLTS recognised the café as an informal social outlet for PwA to “have a chat, have a coffee ... for some people who might not have many others to talk to” (SLTS5). They noted the in-person café provided “a setting for to practice their conversational skills” (SLTS4). SLTS stated that meeting PwA at the Aphasia Café contributed to their professional development and provided a forum to “gain an informal way of interacting with people with aphasia to help them in their clinical practice” (SLTS4). They valued being able to “see past ... the goals that you’re setting for therapy with them” (SLTS3) and develop clinical skills “having attended ... I’ve ... been able to apply some of the strategies to communicate with someone with aphasia at work” (SLTS7).

SLTS considered their role in the Aphasia Café as “being like a communication partner. And having those you know like, conversation facilitators like a pen and paper” (SLTS14). SLTS15 recalled an instance from the in-person Aphasia Café where “one lady was ... after starting using an AAC device. It was great for her to get that opportunity to use it with people who could facilitate that and kind of knew how to facilitate it. It could be tough for people ... to try and get used to that as well. So at least, we [SLTS] will have kind of some more of an idea about that”. SLTS14 stated “It’s a word that keeps coming up to us ... that we’d be facilitators”, while SLTS1 noted the “importance of just hav[ing] general like informal chats with people with Aphasia, because we know that building rapport with people is really, really essential”. SLTS13 highlighted the important role the students play in “keeping on one topic, moving from topics ... make it a theme ... something that you actually give people to talk about”.

Both SLTS and PwA noted the evolving social dynamics within the café, particularly relating to PwA: “we’re facilitating less and less ... they’re talking to each other rather than us kind of trying to bring up the conversation and start something new. They’re ... talking between themselves and talking about their interests (SLTS16). PA3 explained how repeated attendance at the café affected their confidence: “the first time [I came to the café] I wasn’t talking ... the second time I was helping people”.

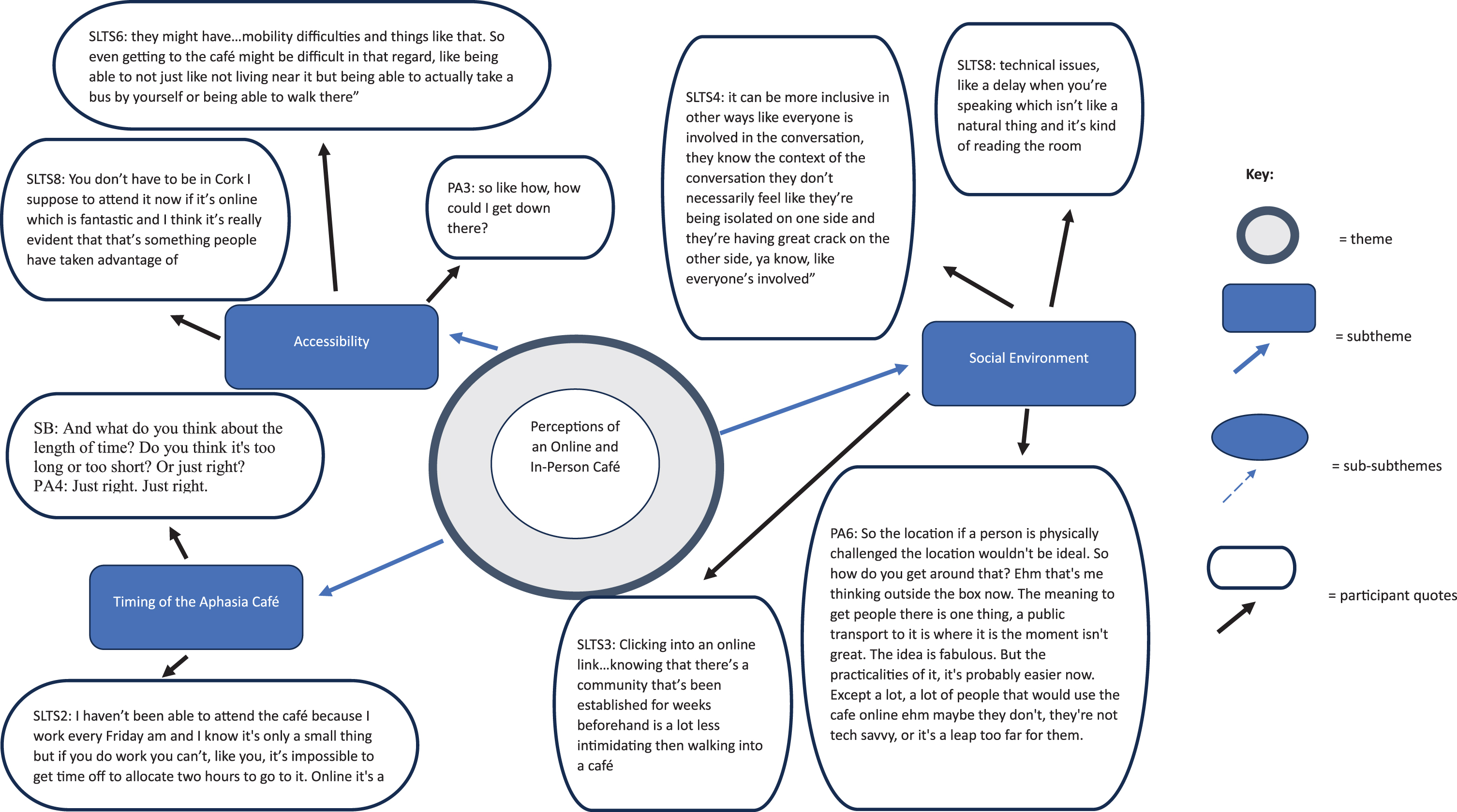

14Perceptions of an online and in-person Aphasia Café

Participants were asked about their experiences of the in-person Aphasia Café compared to online. Three areas (sub-themes) were noted to be of importance to the participants, namely, ‘Accessibility’ (in particular, ‘location’, ‘non-verbal communication’, and ‘technology’), ‘Timing of the Aphasia Café’ and ‘Social Environment’.

15Accessibility

Three main topics were discussed by participants in this theme –location, non-verbal communication, and technology.

15.1Location

The physical location of the in-person Aphasia Café was considered a potential barrier for attendance by PwA and SLTS. PA5 stated “where the café is, isn’t very conducive to public transport” and PA6 noted “the physical effort of getting out of the house, getting into a car, getting on a bus, getting into the café”. This was echoed by SLTS2 who noted “it’s a good stretch down to the train station or the bus station ... you don’t have direct drop off outside the door”. Attendees who “could, or would, or should use the café may have other difficulties that would prevent them” (PA6), such as mobility issues, which could result in PwA relying on others to attend: “while in-person ... . may have to bring them to the Aphasia Café if they can’t get there independently” (SLTS3). This poses additional challenges as expressed by SLTS2 “your husband or ... wife who might be in their sixties or seventies ... . the person with aphasia ... might be mobile enough to sit in a car ... but the barrier there might be who’s actually dropping them”. PA3 also raised hindering travelling costs to the Aphasia Café for those living further afield: “Like 100, 200 euro to travel down every two weeks ... I really wouldn’t have the money to do that”.

The move of the café from in-person to online was viewed as a positive step towards accessibility. SLTS1 noted “one thing that the online café has done is made the café more accessible to a lot of people. Especially people ... who might have mobility difficulties”. PwA stated that “online from the physical point of view is easier, totally” (PA6) and “I am talking, I am practicing... people with aphasia online” (PA1). SLTS10 commented on the “ease of ... just being able to log in for your hour... log off again, and you’re in your own home”. SLTS12 hypothesised that PwA may be more likely to join the café from the comfort of their own home, as “there isn’t a whole pile of unknowns ... the variables are reduced”. PA3 echoed this stating “online, I’d definitely go because I’m home”. Participants noticed increased accessibility resulted in increased café attendance “ye saw that in the huge increase in people that started joining online compared to in-person” (SLTS2). In particular, attendance of PwA across Ireland and internationally was discussed as a benefit to moving online “in the café there’s people from the UK as well can join in and different parts of Ireland, they don’t have to be just from Cork” (SLTS9).

15.2Non-verbal communication

The most commonly identified disadvantage of the online Aphasia Café for both PwA and SLTS was challenges interpreting nonverbal communication. PA5 found it easier to read non-verbal communication in person, stating, “if I just rocked up... I’d just see plenty of smiles looking back at me. That kind of thing, it’ll reflect back at you, you’d get the interaction”. Online interactions resulted in difficulty to “read the ... gestures, and you can’t really see the facial expressions” (SLTS9). SLTS10 recognised turn-taking as being particularly impacted stating “we’re kind of all looking at each other waiting, like ‘Okay, will I speak, will you speak?’ and then you know, someone ends up talking over someone”. While most PwA identified the minimised nonverbal cues as a disadvantage of communicating online, conversely, this helped PA5’s communication stating, “I know the importance of looking at people in the face when we’re talking ... but I... find it hard to catch someone’s face remember the words at the same time”. Four PwA noted they communicated more successfully in face-to-face compared to online interactions as, “you can look at them. You can see what they’re saying” (PA3).

15.3Technology

Interestingly, only one PwA identified lack of familiarity with technology as a barrier to attending the online café, asserting “not everyone with aphasia would be as familiar with this form of communication, they’d be afraid of it” (PA6). Whereas technical difficulties interfering with the online Aphasia Café was one of the most prevalent disadvantages discussed by SLTS, noting, “there’s so many things that can go wrong, if they have a problem once, man, they’re not going to be able to build up that confidence to go on again” (SLTS13). SLTS considered that technology may not be accessible for all PwA and SLTS1 acknowledged that bespoke aphasia-accessible materials might be required, “I know like since we’ve made aphasia accessible materials for getting online, but ... . that could have been a barrier when those resources weren’t in place”. SLTS14 acknowledged that online interactions may prevent PwA from successfully using communication strategies that they used in-person, “if someone relies on... AAC or... pen and paper ... especially if someone’s ... a successful communicator and is confident doing that in person ... that might...turn them off ... online”. Finally, PA6 stated that online conversations could exclude people with severe aphasia as “they listen to what’s going on rather than getting involved”.

16Timing of the Aphasia Café

Overall, the one-hour, fortnightly occurrence of the online Aphasia Café was considered more beneficial than the two-hour monthly in-person Aphasia Café meetings, as “it’s only one hour, every two weeks, it’s grand” (PA3), although PA2 indicated a preference for weekly meetings. PA6 emphasised the time cost associated with in-person attendance, stating “that’s half the day between getting there, being there and coming home, [whereas online] you can look forward to... being in the same house, you can come down in your pyjamas”. Five of the six PwA considered the length of online café to be “just right” (PA4). PwA indicated a preference for the café being held on a Friday, as “it’s the end of the week. Friday should be happy” (PA3). However, some SLTS found the timing to be an issue due to “timetable clashes” (SLT9), “trying to travel home” (SLTS2), and “work commitments” (SLTS8).

17Social environment

Both PwA and SLTS discussed the importance of the environment in social interactions. PA2 believed online group discussions are less natural than in-person, as “there’s just so many online. You have to wait for somebody else to finish”. Conversely, the in-person café was considered to provide a more natural conversational environment and allowed participants to break off into small groups. SLTS1 noted “in the in-person café there was ... small little conversations going on, you could kind of like break off and talk to one or two ... . and have your own little conversation about...what they were interested in”. Other disadvantages noted about large online group discussions were “less opportunities for each person to join in on the conversation” (SLTS1), and “everyone is watching you” (SLTS15). From personal experience, PA5 identified with the latter saying “I’d be kinda shy... it’s really against my, my nature to.. hold so much space and so much time”. However, some participants purported that the online café reduced pressure to participate as “you can just sit in your little box on your screen and not say anything but watch the conversation and then maybe next week you engage a bit more” (SLTS6). PA4 explained their preference for the online café “because there’s less people to talk to” and “left everybody else tell their story”.

SLTS2 proposed that “for people with aphasia, actually [the online café] might give them more like, permission over their identity and how they want to portray themselves”. This was also raised by PA4 who stated they didn’t feel pressure to disclose their difficulties online if they didn’t want to “Well it’s easier in a sense that you ... wouldn’t have to tell anybody”. It was noted that large group discussions could “be more inclusive in other ways like everyone is involved in the conversation, they know the context of the conversation they don’t necessarily feel like they’re being isolated on one side” (SLTS4). SLTS13 however noted that being online is “taking away from the actual point of getting them out of the house ... and not getting over that initial anxiety of actually going out and socialising with people which is kind of a massive part of the aphasia café”. Regardless of in-person or online, PA5 asserted that meeting other PwA had psychosocial benefits for attendees: “someone knows that someone at the other end, at the other side of the table or screen or whatever makes them feel valued”.

18Optimal Aphasia Café

PwA were asked what they envisioned to be the perfect Aphasia Café. PA1 described it as somewhere where PwA could practice “communication skills, learning, listening maybe”. PA1 envisioned that it would include “the teachers, the pupils or students and my friends”. PA2 suggested the café might include aphasia-accessible menus to support those with literacy difficulties. Both PA3 and PA4 indicated a preference for the café to be held in-person but equally noted an online format to be more accessible “I think doing it on online... because ehm I think people will do good than going down to Cork” (PA3). PA5 proposed an optimal café would be “just social, it’s just light” suggesting games such as Scrabble, lists of discussion topics, icebreakers, and conversational aids. PA6 suggested the Aphasia Café could be held at an existing stroke support venue, to offer commensality to attendees.

19Discussion

This study explored the opinions and experiences of PwA and SLTS of an in-person and online Aphasia Café. This study adds to the growing number of recent multi-perspectival aphasia research, which combines the perspectives of people with aphasia and student SLTs in order to form a holistic representation of similar phenomena, such as Kearns and Cunningham (2022), Kristek (2022), Hammarstrom and Samuelsson (2021) and Cameron et al. (2018). While both Aphasia Café configurations brought distinct challenges and benefits for PwA and SLTS, it was identified as a unique and important social outlet, with the online café being particularly important during pandemic-related social restrictions. While both cohorts commented that the in-person café better lent itself to smaller, one-to-one/small group interactions, they noted that the online café was more accessible. This was reflected in the rise in café member numbers and from the broad national and international geographical locations of attendees. It was noted by a number of PwA and SLTS that the online format can potentially hinder the authenticity of conversation, and some missed the physicality of having a cup of tea which reflected a more naturalistic setting. Others commented that being online reduced the pressure of participating allowing them ease into the conversational space at their own pace.

PwA expressed experiencing a sense of community in a space designed specifically for them, where they could exchange stories and learn from other PwA. This aligns with research that reports peer-befriending to be a rewarding experience for PwA (Northcott et al., 2022) with a positive impact on well-being (Hilari et al., 2021) and supports coping with difficulties (VandenBerg, Ali, and Brady, 2018). PwA have been found to spend the majority of time with family members (Lee et al., 2015), and reported difficulty retaining their friends post-stroke (Dalemans et al., 2010). The Aphasia Café presents an opportunity for PwA to expand their pool of conversation partners, thus positively impacting their quality of life. As immediate family and close friends are reported to be those with whom people with aphasia form the most frequent social relationships (Cruice, Worrall, & Hickson, 2006), forming new social connections with those with an understanding of the needs of a PwA may alleviate some communicative burden associated with being the primary conversation partner of the person with aphasia (Winkler et al., 2014).

Interestingly, SLTS highlighted that it gave them opportunities to practice clinical skills outside high-pressured clinical environments. This may be attributed to feeling the need to fulfil a professional role (café facilitator), despite the unstructured nature of the group. Cubirka, Barnes and Ferguson (2015) also reported trainee clinicians maintained a professional persona in aphasia therapy groups for fear of their competence being questioned.

Notably, SLTS perceived technology as a dominant barrier to accessing the online Aphasia Café whereas only one PwA proposed this as a potential hurdle for PwA. Menger, Morris and Salis (2019) report that aphasia considerably influencing digital engagement is only one potential factor, for example, a person who prefers in-person communication pre-stroke may not be motivated to communicate online post-stroke. Making assumptions about the ability of PwA to communicate online warrants caution prompting the recognition of PwA as experts in identifying their own needs (Kearns, Kelly & Pitt, 2020). In this study, the use of technology is observed to support social communication and self-management for PwA as also reported in the literature (Kelly et al., 2016). In fact, several PwA instigated advertising the café through social media encouraging other PwA to attend. Some have advocated for similar services in their locality.

Fig. 2

Socialising changes during the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Fig. 3

Awareness and purpose of the Aphasia Café.

Fig. 4

Perceptions of the online and in-person Aphasia Café.

Fig. 5

Optimal Aphasia Café.

Initially, conversations at the online Aphasia Café were student-led with SLTS undertaking the role of ‘befriender’ and PwA observed as ‘befriendee’. SLTS initially considered their role was to introduce topics, maintain conversation, build rapport and invite PwA to contribute to the discussion. Interestingly, as PwA became more experienced in communicating online, group dynamics changed. PwA became more confident conversing online and over time a noticeable shift was observed by PwA and SLTS where the more seasoned café members transitioned from ‘befriendee’ to ‘befriender’. PwA became more assertive in providing support and advice to their peers and SLTS assumed a more background facilitation role during meetings. This was also reflected in recent research where ‘befriendees’ were noted to provide mutual peer-support (Moss et al., 2021). Levy et al., (2022) encourages aphasia groups to empower people to live successfully with aphasia and combat feelings of seclusion. For some, this empowerment may come from high levels of participation, for others, taking the step to attend is enough.

Optimising mental health and wellbeing was identified as an aphasia research infrastructure priority by the Collaboration of Aphasia Trialists (Ali et al., 2022). Given the established link between social communication and mental wellbeing, a larger number and variety of informal communication groups such as the Aphasia Café should be established. When asked to imagine the optimal Aphasia Café, no two participants described the same vision. Broader configurations of the café would allow different conversation groups to cater to different social needs of the stakeholders.

19.1Limitations

The limitations of this study primarily stem from the contextual constraints imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent integration of the online Aphasia Café into the research design. The unforeseen circumstances surrounding the pandemic necessitated a deviation from the original design, which aimed to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of PWA and SLTS within the framework of an in-person Aphasia Café. For some it would seem unusual to bring two normally very different cohorts together - PwA and university students –with potentially very different life experiences and social behaviours. However, the unprecedented impact of the pandemic limited social engagement for everyone living in Ireland to the same degree, and this multi-perspectival study allowed us to gain insight into the worlds of both cohorts who were forced to move online for social interactions during this time. One of the challenges of carrying out an online study is potentially excluding those less tech-savvy who may hold alternative opinions or experiences. Since our study, the online Aphasia Café is now firmly established with a noteworthy expansion to its membership. While attendance at each meeting varies between 10-15 patrons, the online Aphasia Café currently has > 80 PwA, many of whom are independently tech-savvy with others gaining access to the café with family or healthcare professional assistance. The recruitment process for this study transpired during the early stages of the establishment of the online Aphasia Café when the café had less than 10 patrons. With the substantial growth in membership future research should examine the now-established café more fully, removed from the context of Covid-19.

The researchers are involved in the Aphasia Café therefore participants could potentially be reluctant to give negative responses. However, the data indicates both PwA and SLTS offered both positive and negative opinions about the café. Future research could endeavour to include a greater number of PwA and include family/caregivers to hear their voice regarding this unique social space. This study encourages replication of the café by documenting its history and design, adding to the currently limited literature about implementing informal conversation groups (Levy, et al., 2022).

20Conclusion

The Aphasia Café in this study moved from in-person to online in response to restrictions during the Covid-19 pandemic. This study provides a unique perspective on the delivery of a supported informal conversation group from PwA and the SLTS who facilitate it. Attendees noted merit in both online and in-person cafés with the online café particularly valued for inclusion regardless of geographic location, and in relation to in-person PA6 asserted “you can’t beat a squeezing of the paw”. With adequate resources both online and in-person social spaces would enhance the quality of life for PwA and give valuable experiences for SLTS. This research highlights the pivotal role of technology in fostering connectivity during the Covid-19 era, particularly for those at high risk of social isolation such as PWA.

Conflict of interest

Dr Helen Kelly and Shauna Bell are Guest Editors on this Special Issue. However, they were blinded to the reviewing process for this paper, which was undertaken by a third Guest Editor.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all participants who shared their time, experiences, and opinions in this research.

Supplementary material

[1] The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/ACS-230006.

References

1 | Ali, M. , Soroli, E. , Jesus, L. M. T. , Cruice, M. , Isaksen, J. , Visch-Brink, E. , Grohmann, K. K. , Jagoe, C. , Kukkonen, T. , Varlokosta, S. , Hernandez-Sacristan, C. , Rosell-Clari, V. , Palmer, R. , Martinez-Ferreiro, S. , Godecke, E. , Wallace, S. J. , McMenamin, R. , Copland, D. , Breitenstein, C. , Bowen, A. (2021). An aphasia research agenda –a consensus statement from the collaboration of aphasia trialists. Aphasiology, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2021.1957081 |

2 | Baker, C. , Worrall, L. , Rose, M. , & Ryan, B. ((2019) ). ‘it was really dark’: The experiences and preferences of people with aphasia to manage mood changes and depression. Aphasiology, 34: (4):19–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1673304 |

3 | Brown, K. , Davidson, B. , Worrall, L.E. , & Howe, T. ((2013) ). ‘Making a good time”: The role of friendship in living successfully with aphasia. . International Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 15: (2), 165–175. |

4 | Cameron, A. , Hudson, K. , Finch, E. , Fleming, J. , Lethlean, J. , & McPhail, S. ((2018) ).‘I’ve got to get something out of it. and so do they’: Experiences of people with aphasia and university students participating in a communication partner training programme for Healthcare professionals. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53: (5), 919–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12402 |

5 | Caute, A. , Cruice, M. , Devane, N. , Patel, A. , Roper, A. , Talbot, R. , Wilson, S. , & Marshall, J. ((2022) ).Disability and Rehabilitation, 44: (26),8264–8282. |

6 | Conway, R. , Kelly, D. M. , Mullane, P. , Ni Bhuachalla, C. , O’Connor, L. , Buckley, C. , Kearney, P. M. , Doyle, S. (2021). Epidemiology ofCOVID-19 and public health restrictions during the first wave of the pandemic in Ireland in 2020. Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab049 |

7 | Croteau, C. , McMahon-Morin, P. , Le Dorze, G. Baril, G. ((2020) ), .Impact of aphasia on communication in couples. Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55: (4), 547–557. |

8 | Cruice, M. , Woolf, C. , Caute, A. , Monnelly, K. , Wilson, S. , & Marshall, J. ((2020) ).Preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of personalised online supported conversation for participation intervention for people with Aphasia. . Aphasiology, 35: (10), 1293–1317. |

9 | Cruice, M. , Worrall, L. , & Hickson, L. ((2006) ).Quantifying aphasic people’s social lives in the context of non-aphasic peers. Aphasiology, 20: (12), 1210–1225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687030600790136 |

10 | Cubirka, L. , Barnes, S. , & Ferguson, A. ((2015) ).Student speech pathologists’ experiences of an aphasia therapy group . Aphasiology, 29: (12), 1497–1515. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2015.1041094 |

11 | Cucinotta, D. , & Vanelli, M. ((2020) ).WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis, 91: (1), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397 |

12 | Cuperus, P. , de Kok, D. , de Aguiar, V. , Nickels, L. (2022). Understanding user needs for digital aphasia therapy: Experiences and preferences of speech and Language Therapists. Aphasiology, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2022.2066622 |

13 | Dalemans, R.J.P. , de Witte, L. , Wade, D. , & van den Heuvel, W. ((2010) ). Social participation through the eyes of people with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45: (5), 537–550. |

14 | Ford, A. , Douglas, J. O’Halloran, R. ((2018) ).The experience of close personal relationships from the perspective of people with aphasia: thematic analysis of the literature. . Aphasiology, 32: (4), 367–393. |

15 | Fridriksson, J. , & Hillis, A. E. ((2021) ).Current approaches to the treatment of post-stroke aphasia. Journal of Stroke, 23: (2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2020.05015 |

16 | Gale, N.K. , Heath, G. , Cameron, E. , Rashid, S. , & Redwood, S. ((2013) ).Using the framework method for analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. . BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13: (117). |

17 | Hammarström, I.L. , & Samuelsson, C. ((2021) ).Speech and language interventions for stroke-induced aphasia. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders , 10: (1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1558/jircd.19317 |

18 | Hilari, K. , Behn, N. , James, K. , Northcott, S. , Marshall, J. , Thomas, S. , Simpson, A. , Moss, B. , Flood, C. , McVicker, S. , & Goldsmith, K. ((2021) ).Supporting wellbeing through peer-befriending (SUPERB) for people with aphasia: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. . Clinical Rehabilitation, 35: (8), 1151–1163. |

19 | Kearns, A. , Cunningham, R. (202). Converting to online conversations in COVID-19: People with aphasia and Student‘s experiences of an online Conversation Partner Scheme. Aphasiology. |

20 | Kearns, A. , Kelly, H. , Pitt, I. ((2020) ).Rating experience of ICT-delivered aphasia rehabilitation: co-design of a feedback questionnaire. . Aphasiology, 34: (3), 319–342. |

21 | Kelly, H. , Kennedy, F. , Britton, H. , McGuire, G. , & Law, J. ((2016) ).Narrowing the “digital divide”- facilitating access to computer technology to enhance the lives of those with aphasia: a feasibility study. . Aphasiology, 30: (2-3), 133–163. |

22 | Kelly, H. , Masterson, L. , O’Riordan, E. , Scott, P. (2022). In D Webster (Ed) Clinical Practice in Aphasia. (pp. 61-86). J & R Press Ltd. |

23 | Kennelly, B. , O’Callaghan, M. , Coughlan, D. , Cullinan, J. , Doherty, E. , Glynn, L. , Moloney, E. , & Queally, M. ((2020) ). The COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland: An overview of the health service and economic policy response. Health Policy and Technology, 9: (4), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.021 |

24 | Kristek, E. (2022). “Communication-related quality of life: Perspectives of people with aphasia and speech language pathology students”. All Theses, Dissertations, and Capstone Projects. 547. Accessed via https://griffinshare.fontbonne.edu/all-etds/547 Accessed via https://griffinshare.fontbonne.edu/all-etds/547 |

25 | Kristo, I. Mowl, J. ((2022) ).Voicing the perspectives of stroke survivors with aphasia: A rapid evidence review of post-stroke mental health, screening practices and lived experiences. Health and Social Care in the Community, 30: (4), e898–e908. |

26 | Larkin, M. , Shaw, R. Flowers, P. ((2019) ).Multiperspectival designs and processes in interpretative phenomenological analysis research. Qualitative Research In Psychology, 16: (2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2018.1540655 |

27 | Law, J. , Huby, G. , Irving, AM. , Pringle, AM. , Conochie, D. , Haworth, C. Burston, A. ((2010) ).Reconciling the perspective of practitioner and service user: findings from The Aphasia in Scotland study. The International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45: (5), 551–560. |

28 | Lee, H. , Lee, Y. , Choi, H. , & Pyun, S. B. ((2015) ).Community Integration and Quality of Life in Aphasia after Stroke. Yonsei Medical Journal, 56: (6), 1694–1702. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2015.56.6.1694 |

29 | Levy, D. F. , Kasdan, A. V. , Bryan, K. M. , Wilson, S. M. , de Riesthal, M. , & Herrington, D. P. ((2022) ).Designing and implementing a community aphasia group: An illustrative case study of the aphasia group of middle tennessee. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 7: (5), 1301–1311. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_persp-22-00006 |

30 | Lincoln, N. B. , Kneebone, I. I. , Macniven, J. A. B. , Morris, R. C. (2012). Psychological management of stroke. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119961307 |

31 | Lo, S. H. , Chau, J. P. (2023). Experiences of participating in group-based rehabilitation programmes: A qualitative study of community-dwelling adults with post-stroke aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12845 |

32 | Menger, F. , Morris, J. , & Salis, C. ((2019) ).The impact of aphasia on internet and technology use. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42: (21), 2986–2996. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1580320 |

33 | Moss, B. , Behn, N. , Northcott, S. , Monnelly, K. , Marshall, J. , Simpson, A. , Thomas, S. , McVicker, S. , Goldsmith, K. , Flood, C. , & Hilari, K. ((2021) ).“Loneliness can also kill”: a qualitative exploration of outcomes and experiences of SUPERB peer-befriending scheme for people with aphasia and their significant others. . Disability and Rehabilitation, 44: (18), 5015–5024. |

34 | Neate, T. , Kladouchou, V. , Wilson, S. Shams, S. (2022). “Just Not Together”: The Experience of Videoconferencing for People with Aphasia during the Covid-19 Pandemic. CHI ’22: Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. |

35 | Nichol, L. , Rodriguez, A.D. , Pitt, R. , Wallace, S.J. , Hill, A.J. (2022). “Self-management has to be the way of the future”: Exploring the perspectives of speech-language pathologists who work with people with aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology |

36 | Northcott, S. , & Hilari, K. ((2011) ).Why do people lose their friends after a stroke? International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 46: (5), 524–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00079.x |

37 | Northcott, S. , Behn, N. , Monnelly, K. , Moss, B. , Marshall, J. , Thomas, S. , Simpson, A. , McVicker, S. , Flood, C. , Goldsmith, K. , & Hilari, K. ((2022) ).“For them and for me”: a qualitative exploration of peer befrienders’ experiences supporting people with aphasia in the SUPERB feasibility trial. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44: (18), 5025–5037. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1922520 |

38 | Parr, S. ((2007) ).Living with severe aphasia: Tracking social exclusion. Aphasiology, 21: (1), 98–123. |

39 | Pettigrove, K. , Lanyon, L. E. , Attard, M. C. , Vuong, G. , & Rose, M. L. ((2021) ).Characteristics and impacts of Community Aphasia Group Facilitation: A systematic scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44: (22), 6884–6898. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1971307 |

40 | Pitt, R. , Theodoros, D. , Hill, A. J. , & Russell, T. ((2019) ).The impact of the telerehabilitation group aphasia intervention and networking programme on communication, participation, and quality of life in people with aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21: (5), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2018.1488990 |

41 | Regmi, K. , & Lwin, C. M. ((2021) ).Factors Associated with the Implementation of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for Reducing Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18: (8), 4274. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084274 |

42 | Ross, A. , Winslow, I. , Marchant, P. , & Brumfitt, S. ((2006) ).Evaluation of communication, life participation and psychological well-being in chronic aphasia: The influence of group intervention. Aphasiology, 20: (5), 427–448. |

43 | Skea, Z. C. , MacLennan, S. J. , Entwistle, V. A. , & N’Dow, J. ((2011) ).Enabling mutual helping? Examining variable needs for facilitated peer support. Patient Education and Counseling, 85: (2), e120–e125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.032 |

44 | Tregea, S. , & Brown, K. ((2013) ).What makes a successful peer-led Aphasia Support Group? Aphasiology, 75: (5), 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.796506 |

45 | vaan der Gaag, A. , Smith, L. , Davis, S. , Moss, B. , Cornelius, V. , Laing, S. , & Mowles, C. ((2005) ). Therapy and support services for people with long-term stroke and aphasia and their relatives: a six month follow up study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 19: (4), 372–380. |

46 | VandenBerg, K. , Ali, M. , Cruice, M. , & Brady, M.C. ((2018) ).Support groups for people with aphasia: a national survey of third group facilitators in the UK. Aphasiology, 32: (1), 233–236. sector. |

47 | Wade, J. , Mortley, J. , Enderby, P. ((2003) ).Talk about IT: Views of people with aphasia and their partners on receiving remotely monitored computer-based word finding therapy. Aphasiology, 17: (11), 1031–1056. |

48 | Winkler, M. , Bedford, V. , Northcott, S. , & Hilari, K. ((2014) ).Aphasia blog talk: How does stroke and aphasia affect the carer and their relationship with the person with aphasia? Aphasiology, 28: (11), 1301–1319. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2014.928665 |