Becoming a research participant: Decision-making needs of individuals with neuromuscular diseases

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Research has shown that some people with neuromuscular diseases may have a lower level of education due to lower socioeconomic status and possibly compromised health literacy. In view of these data, it appears important to document their decision-making needs to ensure better support when faced with the decision to participate or not in research projects.

OBJECTIVES:

1) To document the decision-making needs of individuals with neuromuscular diseases to participate in research; 2) To explore their preferences regarding the format of knowledge translation tools related to research participation.

METHODS:

This qualitative study is based on the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. A two-step descriptive study was conducted to capture the decision-making needs of people with neuromuscular diseases related to research participation: 1) Individual semi-directed interviews (with people with neuromuscular diseases) and focus groups (with healthcare professionals); 2) Synthesis of the literature.

RESULTS:

The semi-directed interviews (n = 11), the two focus groups (n = 11) and the literature synthesis (n = 50 articles) identified information needs such as learning about ongoing research projects, scientific advances and research results, the potential benefits and risks associated with different types of research projects, and identified values surrounding research participation: helping other generations, trust, obtaining better clinical follow-up, and socialization.

CONCLUSION:

This paper provides useful recommendations to support researchers and clinicians in developing material to inform individuals with neuromuscular diseases about research participation.

1Background

Since the early 2000’s, research interest into populations with neuromuscular diseases has increased [1]. Among all the existing rare diseases, neuromuscular diseases are among the most frequent. In Canada, people with neuromuscular diseases are often referred to a neuromuscular or movement disorders university-affiliated clinic. The Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean university-affiliated neuromuscular clinic is one of the largest clinics in Canada who follows this population. This region has the highest prevalence of myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) and autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSAC) worldwide and one of the largest cohorts of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy (OPMD) affected individuals. In relation to the latter, a university-affiliated research team has grown over the years and set up their research facilities within the Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les maladies neuromusculaires. As a result, an interdisciplinary research program has been ongoing since 2006 with multifaceted research activities (e.g., natural history studies, international registries, biomarkers identification, clinical trials, development and implementation of clinical practice guidelines and interventions, documentation of outcome measures metrological properties) [2]. Research has shown that some people with neuromuscular diseases may have a lower level of education due to lower socioeconomic status [3] and possibly compromised health literacy [4]. In view of these data, it appears important to document the decision-making needs of people with neuromuscular diseases to ensure better support for their decision to participate in research projects.

The objectives of this research are: 1) to document the decision-making needs of adult individuals with neuromuscular diseases in regard to participation in research activities; 2) explore preferences in format of knowledge translation tools related to their participation in research activities.

2Methods

This study was based on the Ottawa Decision Support Framework [5]. The descriptive qualitative design with individual semi-directed interviews (with individuals with neuromuscular diseases) and focus groups (with healthcare professionnals) was chosen for its flexibility in the topics discussed by participants [6, 8]. For the individual interviews, the three nurse case managers at the Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les maladies neuromusculaires identified potential participants from their caseload. Participants with neuromuscular diseases were selected according to pre-established criteria to obtain a representative sample of affected individuals related to personal characteristics [9] (e.g., diagnosis of neuromuscular disease, age, sex, education) and representativeness of level of exposure to research activities (e.g., questionnaire or biopsy). Individuals who had severe impairments related to cognition or verbal communication, or an inability to consent were excluded. An initial contact was made by their nurse case manager to obtain participant consent to be contacted by the research team.

The formal recruitment was done by a trained research professional. Participants completed a sociodemographic questionnaire. For the focus groups, participants had to have more than two years work experience with neuromuscular disease. In addition, at least three types of healthcare professions had to be represented (e.g., nurse, physiotherapist, neurologist). Interviews and focus groups were approximately one-hour long. Both interview guides had the same content but language was adapted to each group’s level of literacy.

A descriptive study was conducted to define decision-making needs (information needs and values) [6]. This design helps to guide the actions that need to be taken when little information exists in a specific context [7]. The study was conducted with patient partners as co-investigators on the research team. Patient partners were trained by our research team and with the Quebec SPOR-Unit, prior to the project to become familiar with the research process, data collection and interview method. They participated in the creation of the project, in the co-animation of the interviews and in the analysis of the results. The study was carried out in two steps: 1) semi-directed individual interviews (people with neuromuscular disease) and focus groups (healthcare professionals and 2) synthesis of the literature regarding the information needs and values of people with neuromuscular disease related to their participation in research activities.

For step 1, the research team, including patient partners, determined the themes of the interview guide to cover the three main categories of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework: 1) Decisional Needs; 2) Decisional Outcomes; 3) Decision Support [5]. In this study, decisional needs included: decision type/timing, decisional conflict, clinical needs, values, lack of knowledge, support and resources. Decisional outcomes included: quality of the decision based on knowledge of the different options and the values linked to these options. Decision support included knowledge translation tools and significant persons (family, caregivers, healthcare professionals team). All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim in order to perform a qualitative inductive interpretive analysis [9]. The themes included: 1) Knowledge about the clinical, teaching, and research missions of the Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les maladies neuromusculaires; 2) Knowledge about the types of research projects and clinical services offered by the clinic; 3) Context of their attendance (e.g., research and care experiences); 4) Knowledge of the issues related to research participation. To help the discussion around knowledge translation tools, we provided the context for the creation of information and decision-making tools before asking questions on the content, format, and use of these tools including: 5) Information decision-making needs; 6) Research value decision-making needs; 7) Tool format. To lessen the interviewer’s influence on the participants’ point of view, the interviewer used the reformulation technique throughout the interviews. The same process was used for the two focus groups.

After data collection, the themes were entered into the NVivo 11 Software [10]. An extraction grid was constructed based on the themes to proceed to the synthesis of the literature. An in-depth reading of the content of the individual interviews and focus groups was done by three members of the research team. Then, emerging themes were classified according to the three predetermined categories of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (Decisional Needs, Decisional Outcomes, Decision Support). Subthemes for each category were determined inductively afterwards. The themes were then reviewed by the entire research team and proposals were made regarding the emergence of new themes in relation to the Ottawa Decision Support Framework.

For step 2, the general question that guided the literature synthesis was: What are the decision-making needs of individuals with neuromuscular disease regarding information needs and values related to their participating in research activities? Results from step 1 supported the selection of the main concepts for the literature synthesis. An extraction grid was constructed by a research professional validated by the research team before data extraction. The search strategy was divided into three main concepts: 1) Person with a rare genetic disease or neuromuscular disease; 2) Participation in research; 3A) Values associated with participation in research; 3B) Information needs related to participation in research. The principal keywords were rare disease, neuromuscular diseases, patient participation, patient involvement, patient empowerment, patient preference, patient experience, patient values, information, registry, clinical trial, and biobank. This literature synthesis was conducted by one reviewer using the Cochrane method for rapid review and included: a) A comprehensive literature search in databases; b) Pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (i.e., study eligibility criteria); c) Discussion about the limitations of included studies [11]. A comprehensive literature search in four databases was performed (Pubmed, CINAHL, PSYCHInfo, and EMBASE) and bibliographic references were also consulted from selected articles. To be included articles had to be written in French or English within the last 10 years. One member of the research team (the research professional that conducted the qualitative analysis) carried out a first reading of the abstracts followed by a full reading of the articles if they were included. A second person confirmed article selection (principal investigator).

The project was approved by the Comité d’éthique de la recherche du Centre intégré universitaire de santé et des services sociaux du Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean. The experiments were undertaken with the understanding and written consent of each subject, and the study conforms with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki), printed in the British Medical Journal (18 July 1964).

3Results

This study was conducted among eleven individuals with neuromuscular diseases, four healthcare and social services professionals, and seven research-related professionals. For participants with neuromuscular disease, four individuals had DM1, three had OPMD and four had ARSACS. Six were men and five were women. Six had completed high school. Six had already participated in research activities. Health and social service professionals had significant work experience (more than three years) with people with neuromuscular disease and represented at least three different types of professions (doctor, nurse case manager, social worker). As for research-related professionals, they had at least two years of work experience at the Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les maladies neuromusculaires, significant work experience with individuals with neuromuscular disease, and included researchers, research professionals, master or doctoral students involved in research (see Table 1).

Table 1

Participant’s characteristics

| Code | Sexe | Age (years) | Disease | High school education | Prior research participation |

| 01 | W | 50–60 | ARSAC | No | Yes |

| 02 | W | 30–40 | ARSAC | Yes | Yes |

| 03 | W | 30–40 | ARSAC | Yes | Yes |

| 04 | M | 60–70 | OMPD | No | No |

| 05 | M | 70–80 | OMPD | Yes | No |

| 06 | W | 50–60 | OMPD | Yes | No |

| 07 | W | 50–60 | ARSAC | Yes | No |

| 08 | M | 50–60 | DM1 | No | Yes |

| 09 | M | 30–40 | DM1 | No | Yes |

| 10 | M | 30–40 | DM1 | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | M | 30–40 | DM1 | No | Yes |

3.1Step 1: Descriptive qualitative design

The results are presented according to the three main concepts of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework: 1) Decisional Needs; 2) Decisional Outcomes; 3) Decision Support [5].

3.2Decisional needs

Decisional needs, refer to different levels of information that affected individuals with the same diagnosis have about their own disease. Experience with research activities at the Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les maladies neuromusculaires is different according to the neuromuscular disease (DM1, OPMD, ARSACS). Since the early 2000 s, individuals with DM1 have been asked to participate in research activities. Many shared that the more they participated, the more comfortable they felt participating again because they have more information about ongoing research on their disease. However, a structured research program on OPMD and ARSACS has only recently been put in place. One individual said:“There are diseases where there is no research culture (...). ARSACS or OPMD, there is no research. This is new. They don’t know what to expect. It is a culture that is not rooted, compared to other diseases, such as myotonic dystrophy (...). They have been doing intensive research with them since 2002.” (Group2Research)

3.3Decisional outcomes

Decisional outcomes refer to the values associated with research participation for all affected individuals. All participants strongly emphasized the desire to help others with the disease. For example, many of them talked about helping future generations and being part of the solution (feeling of pride), and not part of the problem because of the genes they passed on to their children (feeling of guilt). Many wanted to give everything to research (e.g., compensation, donation, access to their medical files, test results). Some expressed an interest in participating in projects that address all neuromuscular disease, while others wished to participate only in projects that address their own disease.

“To advance research. Yes, they found the gene, but it has to continue. Maybe it’s too late for us, but, for the new ones, it will be convenient to know that they can find a pill or medication.” (P-ARSACS)

In terms of decision-making needs related to information needs, some themes need further exploration, including knowledge of scientific advances related to their disease and the need to receive detailed information about their participation in a research project when the level of risk is higher (for example, muscle biopsy).

Information needs differed, namely the need to know their own individual results from their participation in research activities (progression, or in comparison to normative data), the amount of information and level of detail.

“In my case, I don’t know where the research is at, either. These are research programs. Researchers have results; they sometimes try to tell us how their results work, but it’s not clear.” (P-DM1)

3.4Decision support

Regarding values associated with the decision to participate in research or not, similarities were found, including the importance of having a trust-based relationship with the Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire sur les maladies neuromusculaires healthcare professionals. This trusting relationship helps them feel free to ask questions. They also feel more comfortable knocking on the professional’s door when they are welcoming and interested in their wellbeing. The trust between individuals with neuromuscular disease and research professionals, combined with strong collaboration between neuromuscular clinical healthcare professionals, encourages recruitment for research.

“The feeling of relation and belonging is very strong (...). They feel that we need them. They feel appreciated. We have always taken care of our patients (...). We call them. They call us (...). We have developed a relationship of trust. That’s why you don’t have any difficulty recruiting. There is continuity.” (Group 1 Clinicians)

For information comprehension and retention, participants with DM1 expressed the need to have the same information repeated across many knowledge translation tools and more graphical representation of the concepts associated with the different research activities. Indeed, specific projects are often not clear to them, and they appreciate practical examples to which they can relate to, to get the essence of their participation and goals of the research activities proposed to them. Often, research projects on physical exercise or nutrition are more tangible for them. Individuals with OPMD expressed the need for more specific details in the information provided to them. Various media were discussed for the creation of knowledge translation tools to help the decision-making process. No consensus was reached on any, and media preferences included iPads, videos, websites including social networks like Facebook, posters or leaflets.

“There would be an advertisement that would be interesting to do (or) a DVD that would (play in) the waiting room. ‘You have myotonic dystrophy. Do you know that there is such a thing? (We are having) a study.’ The papers, I don’t look at it. But I keep them all in an envelope. If I have a problem, I’ll be able to look at them. But I don’t read them; I trust you.” (P-DM1)

3.5Step 2: Synthesis of the literature

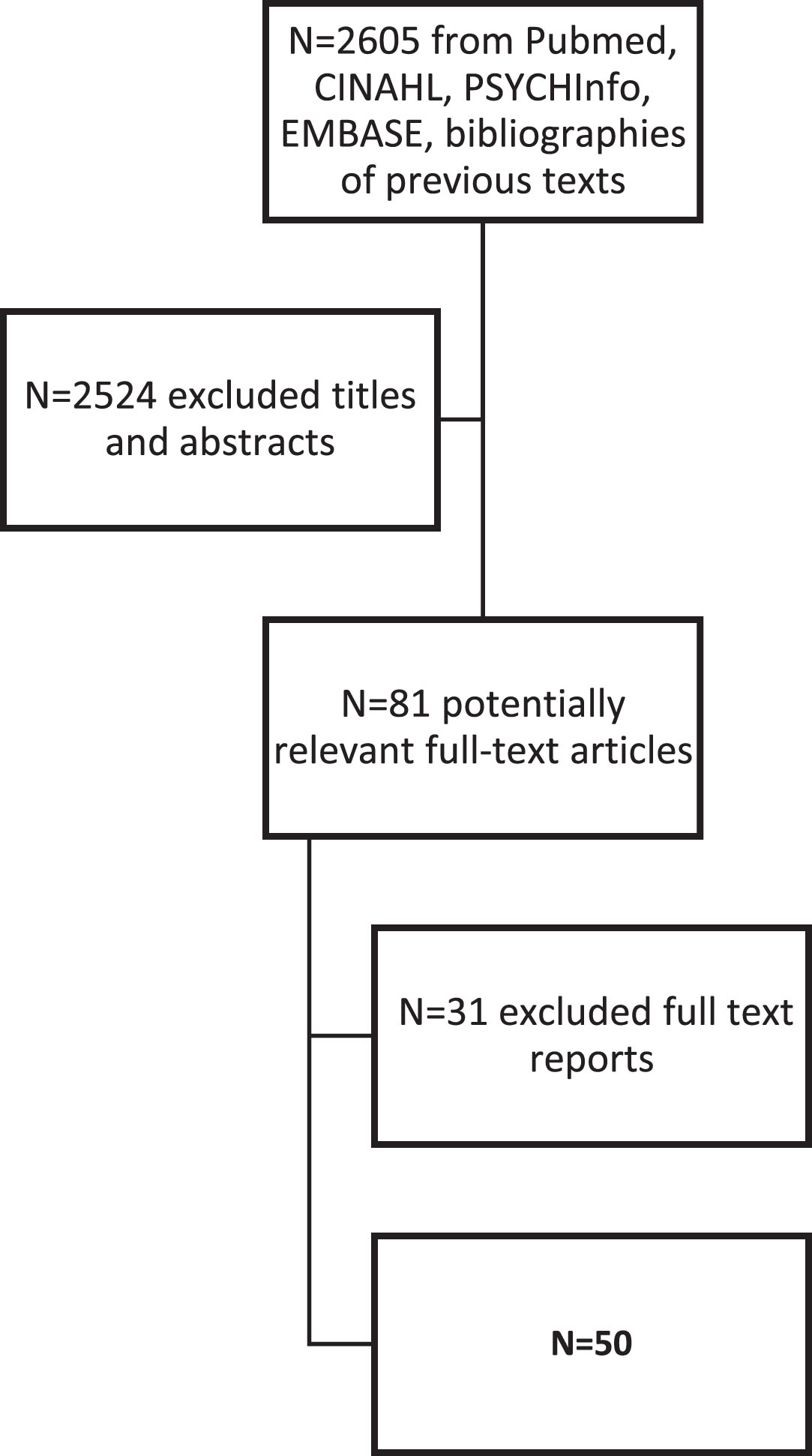

As the studies reviewed addressed different research activities, presentation of the results was divided into the four most common research activities in the area of neuromuscular disease: 1) registries (n = 8); 2) clinical trials (n = 17); 3) biobanks (n = 13) and 4) academic research projects (n = 12) (see Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Fig. 1

Results of literature review.

Table 2

Results details of synthesis of the literature (n = 50)

| Study | Population | ||||||

| # | Sources | First author, years, Country | Title | Design study | Age | Sex | Diagnostic |

| 1 | PUBMED | Woodward, 2016, (Belgium, France, Italy, Russia, Spain and UK) | An innovative and collaborative partnership between patients with rare diseases and industry-supported registries: the Global aHUS Registry | Quantitative descriptive | Unknown | All | Rare diseases |

| 2 | PUBMED | Coathup, 2016, Japan | Using digital technologies to engage with medical research: views of myotonic dystrophy patients in Japan | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Myotonic dystrophy |

| 3 | PUBMED | Gupta, 2011, World Organization | Strategies for Improving Identification and Recruitment of Research Participants | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Rare Lung disease |

| 4 | PUBMED | Kirkpatrick, 2015, USA | GenomeConnect: Match-making Between Patients, Clinical Laboratories, and Researchers to Improve Genomic Knowledge | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Genetic disease |

| 5 | Previous texts | Workman, 2013, USA | Engaging Patients in Information Sharing and Data Collection: The Role of Patient-Powered Registries and Research Networks | Qualitative | Unknown | All | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 6 | Previous texts | EUCERDEMA, 2011, European | Towards a public-private partnership for registries in the field of rare diseases | Qualitative | Unknown | All | Rare diseases |

| 7 | Previous texts | Whiddette, 2005, Australia | Patients’ attitudes towards sharing their health information | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Adult primary-care patients |

| 8 | Previous texts | Schwartz, 2005, USA | A Patient Registry for Cognitive Rehabilitation Research: A Strategy for Balancing Patients’ Privacy Rights With Researchers’ Need for AccessSEP | Quantitative descriptive | 16 and + | All | Stroke or traumatic brain injury |

| 9 | PUBMED | Bardach, 2018, USA | Motivators for Alzheimer’s Diseases Clinical Trial Participation | Quantitative descriptive | 54.6–89.8 | All | Alzheimer’s diseases |

| 10 | PUBMED | Biedrzycki 2011, USA | Research Information Knowledge, Perceived Adequacy, and Understanding in Cancer Clinical Trial Participants | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Gastrointestinal cancer |

| 11 | PUBMED | van der Biessen, 2018, Netherlands, | Understanding how coping strategies and quality of life maintain hope in patients deliberating phase I trial participation | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Incurable cancer |

| 12 | PUBMED | Carroll, 2012, USA | Motivations of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension to participate in randomized clinical trials | Qualitative | All | All | Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| 13 | PUBMED | Godskesen, 2016, Sweden | Differences in trial knowledge and motives for participation among cancer patients in phase 3 clinical trials | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Cancer patients |

| 14 | PUBMED | Godskesen, 2014, Sweden | Hope for a cure and altruism are the main motives behind participation in phase 3 clinical cancer trials | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Cancer patients |

| 15 | PUBMED | Grill, 2013, USA | Risk disclosure and preclinical Alzheimer’s diseases clinical trial enrollment | Quantitative randomized | + 46 | All | Cognitive normal |

| 16 | PUBMED | Henrard, 2015, Belgium | Participation of people with haemophilia in clinical trials of new treatments: an investigation of patients’ motivations and existing barriers | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Adults with haemophilia |

| 17 | PUBMED | Lawrence, 2014, England | Patient and carer views on participating in clinical trials for prodromal Alzheimer’s diseases and mild cognitive impairment | Qualitative | 18+ | All | Alzheimer’s |

| 18 | PUBMED | Mancini, 2010, France | Participants’ uptake of clinical trial results: a randomised experiment | Quantitative randomized | 18+ | Women | HER2-positive non-metastatic breast cancer |

| 19 | PUBMED | Ssali, 2015, Africa | Volunteer experiences and perceptions of the informed consent process: Lessons from two HIV clinical trials in Uganda | Qualitative | 18–40 | All | HIV sero status |

| 20 | CINAHL | Dellson, 2016, Sweden | Patient representatives’ views on patient information in clinical cancer trials | Qualitative | 51–77 | All | Colorectal cancer |

| 21 | CINAHL | DeWard, 2014 (USA, Canada) | Practical Aspects of Recruitment and Retention in Clinical Trials of Rare Genetic Diseases: The Phenylketonuria (PKU) Experience | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Rare diseases |

| 22 | CINAHL | Gaasterland, 2019, European | The patient’s view on rare diseases trial design –a qualitative study | Qualitative | Unknown | Unknown | Rare diseases |

| 23 | CINAHL | Holman, 2010, USA | Patient-derived Determinants for ParticipationSEPin Placebo-controlled Clinical Trials for Fibromyalgia | Quantative descriptive | 18 + | All | Fibromyalgia |

| 24 | PUBMED | Dorcy, 2011, USA | I Had Already Made Up My Mind”: Patients and Caregivers’ Perspectives on Making the Decision to Participate in Research at a U.S. Cancer Referral Center | Qualitative | 18 + | All | Cancer Hematopoietic cell transplants |

| 25 | Previous texts | Kinder, 2010, USA | Predictors for clinical trial participation in the rare lung diseases lymphangioleiomyomatosis | Quantitative descriptive | Age mean 53 | Unknown | Rare lung diseases lymphangioleio-myomatosis |

| 26 | CINAHL | Cervo, 2013, Italy | An effective multisource informed consent procedure for research and clinical practice: an observational study of patient understanding and awareness of their roles as research stakeholders in a cancer biobank | Quantitative descriptive | 18 + | All | Cancer |

| 27 | CINAHL | Fleming, 2015, Australia | Attitudes of the general public towards the disclosure of individual research results and incidental findings from biobank genomic research in Australia | Quantitative randomized | 18+ | All | Patients with potential genetic risk |

| 28 | Previous texts | Eisenhauer, 2017, World | Participants’ Understanding of Informed Consent for Biobanking: A Systematic Review | Systematic Review | Unknown | Unknown | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 29 | PUBMED | Toccaceli, 2014, Italy | Attitudes and Willingness to Donate Biological Samples for Research Among Potential Donors in the Italian Twin Register | Quantative descriptive | 18 + | All | Twins with many types of diseases |

| 30 | Previous texts | Teare, 2015, England | Towards ‘Engagement 2.0’: Insights from a study of dynamic consent with biobank participants | Qualitative | Unknown | Unknown | Musculo-skeletal diseases Diabetes Cancer |

| 31 | Previous texts | Lemke, 2010, USA | Public and Biobank Participant Attitudes toward Genetic Research Participation and Data Sharing | Qualitative | 18+ | All | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 32 | Previous texts | Allen, 2011, Australia | Reconsidering the value of consent in biobank research | Qualitative | 54–80 | All | Cancer |

| 33 | Previous texts | Johnsson, 2010, Sweden, Iceland, UK, Ireland, USA | Hypothetical and factual willingness to participate in biobank research | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 34 | Previous texts | Michie, 2011, USA | If I Could in a Small Way Help”: Motivations for and Beliefs about Sample Donation for Genetic Research | Mixed methods | 18+ | All | Colorectal cancer |

| 35 | Previous texts | Mahnke, 2014, USA | A Rural Community’s Involvement in the Design and Usability Testing of a Computer-Based Informed Consent Process for the Personalized Medicine Research Project | Mixed method | Unknown | Unknown | Rural community |

| 36 | Previous texts | Mancini, 2011, France | Consent for Biobanking: Assessing the Understanding and Views of Cancer Patients | Quantative descriptive | 18 + | All | Colorectal cancer, breast cancer, hematological malignancy |

| 37 | Previous texts | Rahm, 2013, USA | Biobanking for research: a survey of patient population attitudes and understanding | Quantitative descriptive | 18+ | All | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 38 | Previous texts | Toccaceli, 2009, Italy | Research understanding, attitude and awareness towards biobanking: a survey among Italian twin participants to a genetic epidemiological study | Quantitative descriptive | 18+ | All | Twins with many types of diseases |

| 39 | PUBMED | De Freitas, 2017, World | Public and patient involvement in needs assessment and social innovation: a people-centred approach to care and research for congenital disorders of glycosylation | Qualitative | Unknown | All | Congenital disorders of glycosylation |

| 40 | PUBMED | McGrath-Lone, 2015, England | Exploring research participation among cancer patients: analysis of a national survey and an in-depth interview study | Qualitative | 18+ | Women | Breast cancer patients |

| 41 | PUBMED | Mascalzoni, 2017, Europe | The Role of Solidarity(-ies) in Rare Diseases Research | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Rare diseases |

| 42 | PUBMED | Sacristán, 2016, Europe | Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 43 | Embase | Coley, 2018, Finland, France, and the Netherlands. | Older Adults’ Reasons for Participating in an eHealth Prevention Trial: A Cross-Country, Mixed-Methods Comparison | Mixed methods | +65 years old | All | Older adults |

| 44 | CINAHL | Chung, 2018, USA | Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners Patient-Powered Research NetworkSEPPatient Perspectives on Facilitators and Barriers to Building an Impactful Patient-Powered Research Network | Qualitative | 18 + | All | Chronic inflammatory diseases |

| 45 | CINAHL | Gysels, 2012, USA,SEPUKSEP, AustraliaSEP | Patient, caregiver, health professional and researcher views and experiences of participating in research at the end of life: a critical interpretive synthesis of the literatureSEP | Synthesis of the literatureSEP | Unknown | Unknown | Patients end of life |

| 46 | CINAHL | Pollock, 2017, UK | Patient and researcher perspectives on facilitating patient and public involvement in rheumatology research | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Rheumatology diseases |

| 47 | Previous texts | Forsythe, 2014, USA | A Systematic Review of Approaches for Engaging Patients for Research on Rare Diseases | Systematic Review | Unknown | Unknown | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 48 | PUBMED | Damman, 2016, Netherlands | Making comparative performance information more comprehensible: an experimental evaluation of the impact of formats on consumer understanding | Quantitative randomized | 18+ | All | PatientsSEPwith many types of diseases |

| 49 | Embase | Ottman, 2018, USA, Argentina, Canada, Australia | Return of individual results in epilepsy genomic research: A view from the field. | Qualitative | 18+ | All | Epilepsy |

| 50 | Previous texts | Bendixen, 2016, USA | Engaging participants in rare diseases research: a qualitative study of duchenne muscular dystrophy | Qualitative | 18+ | All | Duchenne muscular dystrophy |

3.6Registries

The selected articles focused mainly on the importance of the active involvement of individuals with rare diseases in research (e.g., being more than a patient, becoming a partner by making their voices heard in decision-making) [12–14]. The main reasons for agreeing to participate in a registry study are to help family members, to help other individuals with rare diseases to improve their own health condition, or to improve care and services [12, 15]. Trust in the registries and healthcare professionals involved must be developed with individuals with rare diseases and their families, by actively engaging them in research and information sharing (e.g., ongoing studies and opportunities to participate, showing gratitude for their input) [14, 16, 17]. Their data in the registries should be kept confidential [16, 18]. These data should only be available to certain entities such as their healthcare team and researchers but not private insurance companies [16] (see Table 2).

3.7Clinical trials

The topics covered in the selected articles on clinical trials focused mainly on individual benefits for trial participants [19–32]. For these people, their participation in research on their disease is the only option to improve their condition, sometimes even their last possible choice [19–21, 23, 26–29, 31]. Participating in a clinical trial allowed them to obtain additional healthcare services (especially for those without access to insurance) [19–28, 30, 32]. It also seemed very important to them that their participation in studies would benefit their loved ones (e.g., future generations in their families) [19–21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 32]. Alternatively, the higher the risk of clinical trials (e.g., side effects), the more reluctant they were to participate [19, 21, 24, 25, 32]. They did not wish to be part of a control group [21, 25, 32]. According to them, therapeutic trials sometimes involved invasive procedures (e.g., biopsy) [19] which can cause pain [23] or can deteriorate their health for multiple reasons (e.g., discontinuation of current medication, drug interactions, decreased quality of care, increased testing) [21, 23, 30, 32–34]. This is the reason why their relationship with professionals and their trust in them, are very important [21, 24, 26, 28, 29, 32, 35]. To facilitate comprehension, they suggest structuring the information provided to them (e.g., graphics and images, underscoring, highlighting, bolding, and underlining text, using various colours, sections, and text sizes, as well as Braille, headers, first-impression appeal, meeting agendas, checklists) [27]. Finally, the preferred methods for providing information were through face-to-face meetings (allowing time for discussion and questions) [23, 25, 27, 28, 31, 34], websites and social media [28, 29, 33, 34], pamphlets and letters [25, 28, 33, 34], groups [34], conferences [29], videos [28], and phone calls [34] (see Table 2).

3.8Biobanks

Reasons for participating in research centered mainly on helping others, including future generations [36–43], advancing research knowledge to improve services [36, 38, 39, 41–44] and helping oneself [36, 38, 40–42]. Individuals with rare diseases interviewed in these studies also emphasized the importance of establishing a trusting relationship with those involved in the creation and application of biobanks with knowledge of their credibility and sources [38–40, 44, 45]. According to them, biobanks can contribute to the common good by reducing health costs [37–40, 45]. However, they pointed out that their data must remain confidential [42, 44, 46]. Others highlighted the desire to obtain information on the risks associated with their participation in a biobank when collecting biological materials (e.g., injuries, pain) [38, 42, 46, 47], the benefits [36, 39, 46], and the results of their participation [42, 46, 47]. Some wanted to know if there are rules for sharing and accessing biological materials and other data [38, 46, 48], including what are the penalties if researchers do not respect confidentiality [38, 44, 46]. They would prefer being able to decide who can and cannot access their data [38, 44, 46]. In terms of how to provide information, the studies emphasized that their participants preferred that the content be made accessible to the general public according to their literacy and educational level [37, 38, 40, 46]. Repeating information and maintaining constant communication with research professionals are some of the proposed strategies [40, 44, 46]. Many emphasized the importance of having access to a person who is comfortable with providing information [44] and who is also able to answer their questions [37, 38, 40, 45, 46, 48] (see Table 2).

3.9Academic research projects

The themes covered in the collected texts on academic research (e.g., qualitative with interviews, longitudinal) regarding research values important to individuals with rare diseases focused mainly on the trustworthiness of the information sources [49–54]. The willingness of researchers to give back to individuals with rare diseases [50], to express their gratitude to them [54, 55], to not being cold and distant [55], to promote solidarity (e.g., sharing information) in order to avoid competitiveness (e.g., retention of research results) [50], in developing a research culture accessible for all [55], in participants not feeling used for career advancement purposes by researchers [55] and confidentiality [50, 53, 56], are winning strategies, in their opinion, to help build trust among individuals with rare diseases. Participating in research is a way for individuals with rare diseases to obtain better treatment (e.g., more treatments, detection before deterioration, prevention, improvement of quality of life) and to develop new knowledge [51–53]. Regarding the information that individuals with rare diseases want to receive, the main topic discussed was benefits (e.g., reducing feelings of guilt, helping, socializing) [49–51, 57–58]. They want to receive the results of the study [50, 51, 58, 59]. They also want to receive information on risks before accepting to participate (e.g., anxiety about the results that may affect them regarding their disabilities) [49, 51], eligibility criteria [49, 54], goals and steps [51] and no impact quitting options [51]. Regarding how information is provided, studies emphasized that individuals with rare diseases preferred to receive information face-to-face [50, 51, 54, 55, 58, 59]. When discussing other means of disseminating information, several mentioned technology-based media (e.g., email, Skype, websites) [52–54, 56, 57, 59], while some mentioned more traditional media (e.g., flyers, poster) [51, 57, 59] (see Table 2).

4Discussion

This study explored the decision-making needs (information and values) of individuals with neuromuscular disease when deciding to participate in research activities. Data revealed the following observations: first, they need to know more about research opportunities. Also, helping other generations with neuromuscular disease is an important part of the decision to participate in research. Finally, the creation of knowledge transfer tools to support the decision-making process on patient’s engagement in a research project is also an important part of the decision to participate in research.

Regarding decision-making needs, several individuals with neuromuscular diseases highlighted the need to know more about opportunities to participate in ongoing projects and about scientific advances in the area of their disease. Individuals expressed a desire to know more about the importance of research participation to advance knowledge (e.g., scientific, clinical), and the potential benefits for themselves and other individuals with the same disease. As presented in the results, the development of research on DM1 is more advanced than on OPMD and ARSACS. Some patients have already participated in research projects. This is why it seems important to develop knowledge transfer tools, specific for each disease in relation to scientific advances. As Farha et al. (2020) emphasize, knowledge can influence the willingness of patients to participate in research. Lavoie et al. (2020) add that DM1 patients can choose the knowledge transfer tool that matches their literacy level. It therefore seems important to focus on the vulgarization of all research documents in order to promote recruitment.

Regarding decisional outcomes, all patients highlighted the importance of helping other generations. Contributing to scientific progress and improved practices were themes promoted. Being part of the solution, not the problem, is an important element for individuals because many of them live with the guilt of being a carrier of an inherited disease. Helping others was a theme observed in recent literature [61, 62]. This aspect is important to highlight, because it can strongly influence a person’s decision to participate in a research project. Given that there is no cure for DM1, OPMD or ARSACS and very few ongoing clinical trials, a person’s participation in research may have more of an impact for the next generations than for themselves.

When creating knowledge transfer tools, it is important to take into account the specific needs of individuals with neuromuscular disease to support information retention using several methods, including repetition. They also suggested using several reminders (e.g., diary, calendar, phone call by a professional they know and trust). Recent studies highlighted the importance of involving healthcare professionals who are close to patients in knowledge transfer to build trust [61–63]. A trusting relationshipis very important and the strength of the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean university-affiliated neuromuscular clinic is that the team (e.g., nurses, doctors, physiotherapists, social workers) ensures patient monitoring from birth to death. This contributes to the maturity of the relationship which promotes recruitment and participation in research projects (64). For example, some authors recommend highlighting items on documents that seem important to patients (65). To encourage dissemination, they proposed to involve individuals with neuromuscular disease in the creation of knowledge translation tools. Moreover, as Lavoie et al. (2020) underline, they observed that diversity of format makes it possible to respond to patient preference style of experiential learning. For the transmission of information in digital form, the study by Coathup et al. (2016) underlines that DM1 patients complain about not receiving enough medical information and they would be ready to receive more through digital tools. Especially videos on IPAD for patients with compromised health literacy to avoid abstraction [5].

5Conclusions

One of this study’s major strengths is the involvement of patient partners in documenting reviews, co-leading interviews and in data analysis to better target priority areas to be addressed. In addition, focus groups with professionals from the research community and the healthcare services allowed to expand the interdisciplinary expertise involved in the project. A limitation of the study is related to the sampling procedure that could lead to an ascertainment bias: 1) limited number of affected people recruited; 2) few rare disorders covered; 3) all followed at a specialty center. The literature review resulted in a significant amount of information collected regarding the needs of individuals with neuromuscular diseases related to various research activities (e.g., registries, clinical trials, biobanks). The literature review found that few articles take into account the concept of shared decision-making in research for individuals with neuromuscular diseases. Future studies could examine the impact of shared decision-making on research participation for individuals with neuromuscular diseases and their families. This paper provides useful recommendations to support researchers and clinicians in the development of material to inform individuals with neuromuscular diseases about research participation. Future studies could document the effectiveness of these recommendations to improve patients’ understanding of research activities and support their decision-making process.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our collaborators: three patient partners (Marc Tremblay, Michel Boivin, André Girard), two nurse clinicians (Aline Larouche and Nancy Bouchard), two students (Samar Muslemani and Émilie Godin), the coordinator of the Physical Disability Program (Véronique Tremblay), the university assistant (Isabelle Boulianne) and the research coordinator (Julie Létourneau). Your investment and your reflections brought the analysis of this study to a higher level. We also thank all the participants who shared their time and experiential knowledge. Finally, we thank the Fondation de Ma Vie for the financial support that allowed us to accomplish this study.

Authors’ contributions

Véronique Gauthier: Conception, Methodology, Analysis of data, Preparation of the manuscript, Writing, Reviewing and Editing

Marie-Eve Poitras: Conception, Methodology, Analysis of data, Writing-Reviewing

Mélissa Lavoie: Conception, Writing-Reviewing

Benjamin Gallais: Conception, Writing-Reviewing

Samar Muslemani: Conception, Writing-Reviewing

Michel Boivin: Conception, Analysis of data, Writing-Reviewing

Marc Tremblay: Conception, Analysis of data, Writing-Reviewing

Cynthia Gagnon: Conception, Methodology, Analysis of data, Supervision, Writing, Reviewing and Editing

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

[1] | Institute of Medicine, Rare Diseases and Orphan Products: Accelerating Research and Development.<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56191/>, 2010). |

[2] | Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de servicessociaux du Saguenay—Lac-Saint-Jean, Clinique des maladiesneuromusculaires.<https://santesaglac.gouv.qc.ca/soins-et-services/deficience-physique/clinique-des-maladies-neuromusculaires/>, 2020). |

[3] | Laberge L. , Veillette S. , Mathieu J. , Auclair J. and Perron M. , The correlation of CTG repeat length with material and social deprivation in myotonic dystrophy, Clinical Genetics 71: (1) ((2007) ), 59–66. |

[4] | Lavoie M. , Développement d’une intervention d’éducationthérapeutique fondée sur la philosophie du pouvoir d’agirpour les personnes avec la dystrophie myotonique de type 1,Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, 2020. |

[5] | Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa Decision Support Framework (ODSF). <https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/odsf.html>, 2020). |

[6] | Patton M. , Qualitative research & evaluation methods, SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, 2015. |

[7] | Elliott R. and Timulak L. , Descriptive and interpretive approaches to qualitative research, A Handbook of Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology 1: ((2005) ), 147–159. |

[8] | Krueger R.A. and Casey M.A. , Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research, SAGE Publishing, Thousand Oaks, (2014) . |

[9] | Fortin M.F. and Gagnon J. , Fondements et étapes du Processus de Recherche: Méthodes Quantitatives et Qualitatives, Les Editions de la Cheneliere, Incorporated, 2010. |

[10] | AlYahmady H.H. and Alabri S.S. , Using NVivo for data analysis in qualitative research, International Interdisciplinary Journal of Education 2: (2) ((2013) ), 181–186. |

[11] | Tricco A. , Antony J. and Straus S. , Systematic reviews vs. rapid reviews: What’s the difference? Canada: University of Toronto ((2014) ). |

[12] | Souto R.Q. , Khanassov V. , Hong Q.N. , Bush P.L. , Vedel I. and Pluye P. , Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, International Journal of Nursing Studies 52: (1) ((2015) ), 500–501. |

[13] | Woodward L. , Johnson S. , Walle J.V. , Beck J. , Gasteyger C. , Licht C. , et al., An innovative and collaborative partnership between patients with rare disease and industry-supported registries: the Global aHUS Registry, Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 11: (1) ((2016) ), 154. |

[14] | Workman T.A. , Engaging Patients in Information Sharing and Data Collection: The Role of Patient-Powered Registries and Research Networks, AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care, Rockville (MD), 2013. |

[15] | EUCERDEMA Workshop Report, Towards a public-private partnership for registries in the field of rare diseases.<http://www.eucerd.eu/?post_type=document&p=1234>>, 2016). |

[16] | Gupta S. , Bayoumi A.M. and Faughnan M.E. , Strategies for Improving Identification and Recruitment of Research Participants, CHEST 140: (5) ((2011) ), 1123–1129. |

[17] | Whiddett R. , Hunter I. , Engelbrecht J. and Handy J. , Patients’ attitudes towards sharing their health information, International Journal of Medical Informatics 75: (7) ((2006) ), 530–541. |

[18] | Schwartz M.F. , Brecher A.R. , Whyte J. and Klein M.G. , A patient registry for cognitive rehabilitation research: a strategy for balancing patients’ privacy rights with researchers’ need for access, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 86: (9) ((2005) ), 1807–1814. |

[19] | Coathup V. , Teare H.J. , Minari J. , Yoshizawa G. , Kaye J. , Takahashi M.P. , et al., Using digital technologies to engage with medical research: views of myotonic dystrophy patients in Japan, BMC Medical Ethics 17: (1) ((2016) ), 51. |

[20] | Bardach S.H. , Holmes S.D. and Jicha G.A. , Motivators for Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial participation, Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 30: (2) ((2018) ), 209–212. |

[21] | van der Biessen D.A. , van der Helm P.G. , Klein D. , van der Burg S. , Mathijssen R.H. , Lolkema M.P. , et al., Understanding how coping strategies and quality of life maintain hope in patients deliberating phase I trial participation, Psycho-oncology 27: (1) ((2018) ), 163–170. |

[22] | Carroll R. , Antigua J. , Taichman D. , Palevsky H. , Forfia P. , Kawut S. , et al., Motivations of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension to participate in randomized clinical trials, Clinical Trials 9: (3) ((2012) ), 348–357. |

[23] | Godskesen T. , Kihlbom U. , Nordin K. , Silén M. and Nygren P. , Differences in trial knowledge and motives for participation amongcancer patients in phase 3 clinical trials, European Journal ofCancer Care 25: (3) ((2016) ), 516–523. |

[24] | Godskesen T. , Hansson M.G. , Nygren P. , Nordin K. and Kihlbom U. , Hope for a cure and altruism are the main motives behind participation in phase 3 clinical cancer trials, European Journal of Cancer Care 24: (1) ((2015) ), 133–141. |

[25] | Grill J.D. , Karlawish J. , Elashoff D. and Vickrey B.G. , Risk disclosure and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease clinical trial enrollment, Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9: (3) ((2013) ), 356–359. |

[26] | Lawrence V. , Pickett J. , Ballard C. and Murray J. , Patient and carer views on participating in clinical trials for prodromal Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment, International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 29: (1) ((2014) ), 22–31. |

[27] | Ssali A. , Poland F. and Seeley J. , Volunteer experiences and perceptions of the informed consent process: Lessons from two HIV clinical trials in Uganda, BMC Medical Ethics 16: (1) ((2015) ), 86. |

[28] | Dellson P. , Nilbert M. and Carlsson C. , Patient representatives’ views on patient information in clinical cancer trials, BMC Health Services Research 16: (1) ((2015) ), 36. |

[29] | DeWard S.J. , Wilson A. , Bausell H. , Volz A.S. and Mooney K. , Practical aspects of recruitment and retention in clinical trials of rare genetic diseases: the phenylketonuria (PKU) experience, Journal of Genetic Counseling 23: (1) ((2014) ), 20–28. |

[30] | Gaasterland C. , Jansen–van der Weide M. , du Prie–Olthof M. , Donk M. , Kaatee M. , Kaczmarek R.C. , et al., The patient’s view on rare disease trial design–a qualitative study, Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 14: (1) ((2019) ), 31. |

[31] | Holman A.J. , Neradilek M.B. , Dryland D.D. , Neiman R.A. , Brown P.B. and Ettlinger R.E. , Patient-derived determinants for participation in placebo-controlled clinical trials for fibromyalgia, Current Pain and Headache Reports 14: (6) ((2010) ), 470–476. |

[32] | Dorcy K.S. and Drevdahl D.J. , I had already made up my mind”: patients and caregivers’ perspectives on making the decision to participate in research at a US cancer referral center, Cancer Nursing 34: (6) ((2011) ), 428. |

[33] | Kinder B.W. , Sherman A.C. , Young L.R. , Hagaman J.T. , Oprescu N. , Byrnes S. , et al., Predictors for clinical trial participation in the rare lung disease lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Respiratory Medicine 104: (4) ((2010) ), 578–583. |

[34] | Henrard S. , Speybroeck N. and Hermans C. , Participation of people with haemophilia in clinical trials of new treatments: an investigation of patients’ motivations and existing barriers, Blood Transfusion 13: (2) ((2015) ), 302. |

[35] | Mancini J. , Genre D. , Dalenc F. , Ferrero J.-M. , Kerbrat P. , Martin A.-L. , et al., Participants’ uptake of clinical trial results: a randomised experiment, British Journal of Cancer 102: (7) ((2010) ), 1081. |

[36] | Biedrzycki B.A. , Research information knowledge, perceived adequacy, and understanding in cancer clinical trial participants, Oncology Nursing Forum, 2011. |

[37] | Toccaceli V. , Fagnani C. , Gigantesco A. , Brescianini S. , D’Ippolito C. and Stazi M.A. , Attitudes and willingness to donate biological samples for research among potential donors in the Italian Twin Register, Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 9: (3) ((2014) ), 39–47. |

[38] | Teare H.J.A. , Morrison M. , Whitley E.A. and Kaye J. , Towards “Engagement 2.0”: Insights from a study of dynamic consent with biobank participants, Digit Heal (2015), 1–13. |

[39] | Lemke A.A. , Wolf W.A. , Hebert-Beirne J. and Smith M.E. , Public and biobank participant attitudes toward genetic research participation and data sharing, Public Health Genomics 13: (6) ((2010) ), 368–377. |

[40] | Allen J. and McNamara B. , Reconsidering the value of consent in biobank research, Bioethics 25: (3) ((2011) ), 155–166. |

[41] | Michie M. , Henderson G. , Garrett J. and Corbie-Smith G. , If I could in a small way help: motivations for and beliefs about sample donation for genetic research, Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 6: (2) ((2011) ), 57–70. |

[42] | Mancini J. , Pellegrini I. , Viret F. , Vey N. , Daufresne L.-M. , Chabannon C. , et al., Consent for biobanking: assessing the understanding and views of cancer patients, Journal of the National Cancer Institute 103: (2) ((2011) ), 154–157. |

[43] | Rahm A.K. , Wrenn M. , Carroll N.M. and Feigelson H.S. , Biobanking for research: a survey of patient population attitudes and understanding, Journal of Community Genetics 4: (4) ((2013) ), 445–450. |

[44] | Toccaceli V. , Fagnani C. , Nisticò L. , D’Ippolito C. , Giannantonio L. , Brescianini S. , et al., Research understanding, attitude and awareness towards biobanking: a survey among Italian twin participants to a genetic epidemiological study, BMC Medical Ethics 10: (1) ((2009) ), 4. |

[45] | Cervo S. , Rovina J. , Talamini R. , Perin T. , Canzonieri V. , De Paoli P. , et al., An effective multisource informed consent procedure for research and clinical practice: an observational study of patient understanding and awareness of their roles as research stakeholders in a cancer biobank, BMC Medical Ethics 14: (1) ((2013) ), 30. |

[46] | Johnsson L. , Helgesson G. , Rafnar T. , Halldorsdottir I. , Chia K.-S. , Eriksson S. , et al., Hypothetical and factual willingness to participate in biobank research, European Journal of Human Genetics 18: (11) ((2010) ), 1261. |

[47] | Eisenhauer E.R. , Tait A.R. , Rieh S.Y. and Arslanian-Engoren C.M. , Participants’ Understanding of Informed Consent for Biobanking: A Systematic Review, Clinical nursing research (2017). |

[48] | Fleming J. , Critchley C. , Otlowski M. , Stewart C. and Kerridge I. , Attitudes of the general public towards the disclosure of individual research results and incidental findings from biobank genomic research in Australia, Internal Medicine Journal 45: (12) ((2015) ), 1274–1279. |

[49] | Mahnke A.N. , Plasek J.M. , Hoffman D.G. , Partridge N.S. , Foth W.S. , Waudby C.J. , et al., A rural community’s involvement in the design and usability testing of a computer-based informed consent process for the personalized medicine research project, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 164: (1) ((2014) ), 129–140. |

[50] | McGrath-Lone L. , Day S. , Schoenborn C. and Ward H. , Exploring research participation among cancer patients: analysis of a national survey and an in-depth interview study, BMC Cancer 15: (1) ((2015) ), 618. |

[51] | Mascalzoni D. , Petrini C. , Taruscio D. and Gainotti S. , The Role of Solidarity (-ies) in Rare Diseases Research, Rare Diseases Epidemiology: Update and Overview, Springer 2017, pp. 589–604. |

[52] | Sacristán J.A. , Aguarón A. , Avendaño-Solá C. , Garrido P. , Carrión J. , Gutiérrez A. , et al. Patient involvement in clinical research: why, when, and how, Patient Preference and Adherence 10: ((2016) ), 631. |

[53] | Coley N. , Rosenberg A. , van Middelaar T. , Soulier A. , Barbera M. , Guillemont J. , et al., Older Adults’ Reasons for Participating in an eHealth Prevention Trial: A Cross-Country, Mixed-Methods Comparison, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association (2018). |

[54] | Chung A.E. , Vu M.B. , Myers K. , Burris J. and Kappelman M.D. , Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners Patient-Powered Research Network: Patient Perspectives on Facilitators and Barriers to Building an Impactful Patient-Powered Research Network, Medical Care 56: (10 Suppl 1) ((2018) ), S33. |

[55] | Bendixen R.M. , Morgenroth L.P. and Clinard K.L. , Engaging participants in rare disease research: a qualitative study of Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Clinical Therapeutics 38: (6) ((2016) ), 1474–1484. |

[56] | Gysels M.H. , Evans C. and Higginson I.J. , Patient, caregiver, health professional and researcher views and experiences of participating in research at the end of life: a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature, BMC Medical Research Methodology 12: (1) ((2012) ), 123. |

[57] | De Freitas C. , Dos Reis V. , Silva S. , Videira P.A. , Morava E. and Jaeken J. , Public and patient involvement in needs assessment and social innovation: a people-centred approach to care and research for congenital disorders of glycosylation, BMC Health Services Research 17: (1) ((2017) ), 682. |

[58] | Pollock J. , Raza K. , Pratt A.G. , Hanson H. , Siebert S. , Filer A. , et al. Patient and researcher perspectives on facilitating patient and public involvement in rheumatology research, Musculoskeletal Care 15: (4) ((2017) ), 395. |

[59] | Ottman R. , Freyer C. , Mefford H.C. , Poduri A. , Appelbaum D.H. , Burke W. , et al. Return of individual results in epilepsy genomic research: A view from the field, Epilepsia 59: (9) ((2018) ), 1635–1642. |

[60] | Abu Farha R. , Alzoubi K.H. , Khabour O.F. and Mukattash T.L. , Factors Influencing Public Knowledge and Willingness to Participate in Biomedical Research in Jordan: A National Survey, Patient Preference and Adherence 14: ((2020) ), 1373–1379. |

[61] | Gayet-Ageron A. , Rudaz S. and Perneger T. , Study design factorsinfluencing patients’ willingness to participate in clinicalresearch: a randomised vignette-based study, BMC Med ResMethodol 20: ((2020) ), 93. |

[62] | Beskow L.M. , Hammack-Aviran C.M. and Brelsford K.M. , Developingmodel biobanking consent language: what matters to prospectiveparticipants? BMC Med Res Methodol 20: (1) ((2020) ), 119. |

[63] | Algabbani A. , Alqahtani A. and BinDhim N. , Willingness anddeterminants of participation in public health research: across-sectional study in Saudi Arabia, Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 27: (1) ((2021) ). |

[64] | Lavoie M. , Gallagher F. and Chouinard M.C. , Description du processuséducationnel mis en place par les infirmières auprès depersonnes avec la dystrophie myotonique de type 1, Educ Ther Patient /Ther Patient Educ 12: (2) ((2020) ). |

[65] | Parnell T.A. , Content development. Dans T. A. Parnell, Health literacy in nursing: Providing person-centered care, Springer Publishing (2015), pp. 159–179. |

[66] | Coathup V. , Teare H.J. , Minari J. , Yoshizawa G. , Kaye J. , Takahashi M.P. , et al., Using digital technologies to engage with medical research: views of myotonic dystrophy patients in Japan, BMC Medical Ethics 17: (1) ((2016) ), 1–8. |