Securing the future of statistics in Africa through National Strategies for the Development of Statistic

Abstract

Adoption of development agendas at different levels – national, regional, continental, and global level – has led to an unprecedented increase in demand for official statistics. This increase has not only brought to the fore a litany of challenges facing National Statistical Systems (NSSs) in Africa but also it has created opportunities for strengthening statistical production and development. This paper underscores the need for countries to take full advantage of these opportunities and increase investments in statistics, undertake data innovation, and expand and diversify data ecosystems, leveraging on the foundations of the data revolution for sustainable development and in line with current international statistical frameworks. The paper posits that these improvements will not happen coincidentally nor through ad hoc, piecemeal and uncoordinated approaches. Rather they will happen through more systematic, coordinated and multi-sectoral approaches to statistical development. The National Strategy for the Development of Statistics (NSDS) is presented as a comprehensive and robust framework for building statistical capacity and turning around NSSs in African countries. The paper unpacks the NSDS; elaborates the NSDS processes including; mainstreaming sectors into the NSDS, the stages of the NSDS lifecycle and the role of leadership in the NSDS proces; highlights NSDS extension; presents the design and implementation challenges, and the key lessons learned from the NSDS processes in Africa in the last 15 years or so.

1.Introduction

In developing countries, the dawn of the new millennium was marked by, inter alia, a paradigm shift in national planning focus away from the production of outputs to the achievement of results/impact of development processes. Since then, managing for results or results agenda has become a global concern for both national governments and development agencies to reduce poverty (headline Millennium Development Goal – MDG and now headline Sustainable Development Goal), support sustainable and equitable economic growth, better define and systematically measure development outcomes, and report on achievements of outcomes and impact of development policies and plans.

1.1Linkage of statistics and NSDSs to development agenda

Results based development agendas that are data-intensive include national development plans (NDPs), regional integration and development strategies, Africa Agenda 2063 on “The Africa We Want” and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Statistical information is recognized internationally as an integral part of the results agenda. Statistics illuminate issues that need policy intervention, inform the process of governance (e.g. supporting policy development, resource allocation, and accountability), support monitoring and reporting on development progress and facilitate better decision-making, and hence more effective use of valuable resources for development and poverty reduction [1, 2, 4, 9, 15]. This is particularly important in Africa where government resources are limited. It is, therefore, important to underscore the point that is usually not well understood or properly stated, that not only are statistics needed to monitor progress towards achievement of development goals but also in attaining development progress. In other words, statistics play a dual role of informing and influencing development. Indeed availability of quality statistics – relevant, accurate, timely, sufficiently disaggregated, accessible and easy to use has been recognized as one of the success factors of development agendas.

While the importance of statistics to national development is well recognized across Africa [4, 6, 8, 11], this recognition has not always translated into adequate national investment in statistical development. This has been attributed to failure to mainstream statistics into national and development partners’ development policies, plans, programmes and budgets. While by and large statistics is identified and used as a tool for monitoring and evaluation, it is not recognized as weak and in need of development in terms of systems, infrastructure and capacity. Mainstreaming statistics is about identifying statistics as a cross-cutting development issue/sector and targeting it for development as is done for other cross-cutting development issues/sectors such as gender, environment, water, justice, etc. Such mainstreaming was underscored by African Heads of State and Government at their Twenty-Third Ordinary Session of Assembly of the African Union held in June 2014. The Assembly, “ Requested African Union Commission, the UN Economic Commission for Africa, the African Development Bank and the United Nations Development Programme to facilitate regular expert dialogue between development planners and statisticians, with the purpose of embedding statistics in planning and management for results, so that Africa’s transformative Agenda is achieved” [3]. However, few African countries have mainstreamed statistics into their NDPs. The following table presents examples of countries that have done so.

Table 1

Examples of countries that have mainstreamed statistics into their NDPs

| Country | Narrative |

|---|---|

| 1. Kenya |

|

| 2. Namibia |

|

| 3. Uganda |

|

| 4. Zambia |

|

PARIS21 recommends that NDPs and NSDSs should be treated as complementary tools and they should accordingly cover the same period [9]. Cote d’Ivoire has successfully synchronized the NSDS with the NDP by integrating the NSDS in the country’s NDP. It is reported “The development of the national statistical system, which is regarded as a priority in the same way as that of other sectors, is dealt with systematically in each of the four volumes that make up the NDP (2012–2015): at the level of the diagnosis, the Vision and the detailed matrix of priority actions. In total, 71.5% of the global financing of the 2012–2015 NSDS was covered in the NDP” [9]. Another country where synchronization between NSDS and NDP has been achieved is Uganda. When Ugand’s PNSD II (2013/14–/2017/18) ended, the government extended it for two years so that the follow-up plan, PNSD III (2020/21–2024/25), could be synchronized with NDP III (2020/21–2024/25). Indeed, the two plans – PNSD III and NDP III – were designed as complementary processes [12, 13].

1.2Challenges of meeting data demand

The development agendas have led to an unprecedented increase in demand for data not just in terms of quantity but also in terms of scope, quality, and disaggregation. This has put immense pressure on National Statistical Systems (NSSs) that, by and large, were already fragile, under-resourced, and under-performing. Some countries operating under severe financial and human resource constraints have not been able to produce even basic data without donor funding. These countries have been trapped in a“vicious cycl” of low data demand that leads to inadequate resources for data production and development, which in turn leads to poor statistical outputs. This state is characterized by low statistical literacy across society; ineffective governance of the NSS; a disconnect between data producers and users which did not augur well for evidence-based policy design and decision-making; low status, power and capacity of the National Statistics Office (NSO); inadequate statistical coordination; low investment in infrastructure, processes, and people, leading to overall low statistical capacity and performanc; failure to fully harness the potential of new tools and Information Technology (IT) for statistical development; and ultimately, inadequate data uptake and impact.

To unleash the power of data to change peoples’ lives, these countries need to turn into “virtuous cycle” countries where: more and better quality statistics are produced and used to inform development processes; there is increased investment in statistics (budgets, skilled and motivated staff, financial and technical assistance); and there is improved performance of NSSs (improved user engagement, data quantity, quality, dissemination, and user satisfaction). Needless to say, the COVID-19 pandemic has shined a spotlight on data to measure the extent of spread and inform policy responses across all countries.

The aforementioned increase in data demand has also brought to the fore weaknesses and gaps in the NSSs. It has also improved the visibility of statistical work and, thankfully, new opportunities for statistical production.

This paper underscores the need for countries to take full advantage of these opportunities and increase investments in statistical production and development, undertake data innovation, expand and diversify data ecosystems and leverage the foundations of the data revolution for sustainable development. The data revolution is about the data deluge in terms of volume, speed, and variety; growing demand for data from different parts of society; integration of traditional and non-traditional (new) data sources; increased data use through data openness and transparency; and empowerment of people to access and use data [14]. Countries need to embrace the data revolution to ably meet the said increasing data demand [8]. The paper makes a business case for a paradigm shift away from ad hoc, piecemeal and uncoordinated approaches to more systematic, coordinated, and multi-sectoral approaches to statistical development in the African countries. The shift emphasizes building long-term statistical capacity to meet current and future data needs rather than meet immediate short-term data needs. This and more should be enabled by designing and implementing statistical plans. A second generation statistical plan, the National Strategy for the Development Plan (NSDS), its processes, and possible impact are elaborated. The overarching goal of NSDS is to spearhead and accelerate statistical capacity building to produce, manage, disseminate, and promote more uptake and use of better statistics across society.

2.National Strategy for the Development of Statistics

2.1Unpacking the NSDS

Up till 2004, statistical plans across Africa focused on the NSO and their design did not pay enough attention to the process. In strategic planning, the process is as important as the plan. These were first generation statistical plans which while they helped improve statistics produced by NSOs, by and large, they did not bring about overall improvements in the NSSs, viz. they did not turn the NSSs around. Realizing that most of the data required for monitoring national and international development do not come from the NSO but rather from other data producers in the NSS, a second generation statistical plan, the NSDS that covers the entire NSS was mooted in 2004. Countries in developing world have been urged to design and implement the NSDS as a framework for taking National Statistical Systems to a new level [4, 6, 8, 15]. The NSDS framework is now promoted across the world by PARIS21 and partners. PARIS21 is a global partnership of national and international statisticians, development practitioners, policymakers, analysts, and other users of statistics who are committed to making a difference in the contribution of statistics to development processes.

The NSDS is a robust, comprehensive, and coherent framework intended to strengthen statistical capacity across the entire NSS and respond to key user needs [1, 9]. In particular, the NSDS is a framework for:

• promoting statistical advocacy to create greater awareness about the role of statistics, and enhancing demand for and use of statistics especially for results agendas;

• forging and/or strengthening partnership for statistical development among producers and users of statistics as well as for donor harmonization;

• formulating a vision of where NSS should be in the medium to long term; a “road map” and “milestones” for getting there; and a base from which progress can be measured and establishes a mechanism for informed change when neede;

• continual assessment of ever-changing user needs for statistics and for building needed capacity to meet these needs in a more coordinated, synergic, and efficient manner. It also supports planning for current production and use of better statistics, and acceleration of sustainable statistical capacity building for the futur;

• good communication, feedback and learning all of which are essential for organizational growth and performance enhancement;

• mobilizing, harnessing and leveraging resources (both national and international);

• galvanizing individual energies into the total effort, creation of quality awareness and enhancement of national statistics, foresight and organizational learning;

• introduction of modern and proven strategic planning and management principles and good practices in the handling of official statistics; and

• strengthening of statistical coordination across the NSS;

• heralding the data revolution into the countries.

2.2NSDS process

2.2.1Importance of the process

In designing the NSDS, a lot of attention should be paid to the process and, indeed, the process has become a defining feature of the NSDS visà-vis previous statistical plans. The highlights of the process include:

• designing the NSDS not in isolation but rather as part of the nation’s overall development processes and priorities – the NSDS should be anchored into national development agenda and processes and indeed PARIS21 recommends that designing NSDS and a NDP should be complementary processes [9];

• statistical advocacy to create awareness at different levels about the NSDS and statistics in general;

• broadening and deepening statistical reforms including reviewing the national Statistics Act;

• wide stakeholder participation and inclusion, enriching dialogue and building consensus and creating ownership among stakeholders;

• taking a cue from the process of designing national Poverty Reduction Strategies. To underscore participation and ownership as essential for successful strategic management and the key to the success of any development strategy as “People support what they help to creat”;

• introspection – sitting back and asking ourselves the following questions, among others: How are we doing? Can we do better in terms of processes, business models, methodologies? How can statistics have greater impact; and

• designing country-specific, country-owned, stake- holder-driven, and sector-inclusive national statistical strategies.

The NSDS process is well documented in various guidelines including guidelines by PARIS21 [9] and African Development Bank et al. [1]. Developing countries are urged to follow these guidelines closely, taking into account country specificities and avoiding the “one size fits al” syndrome.

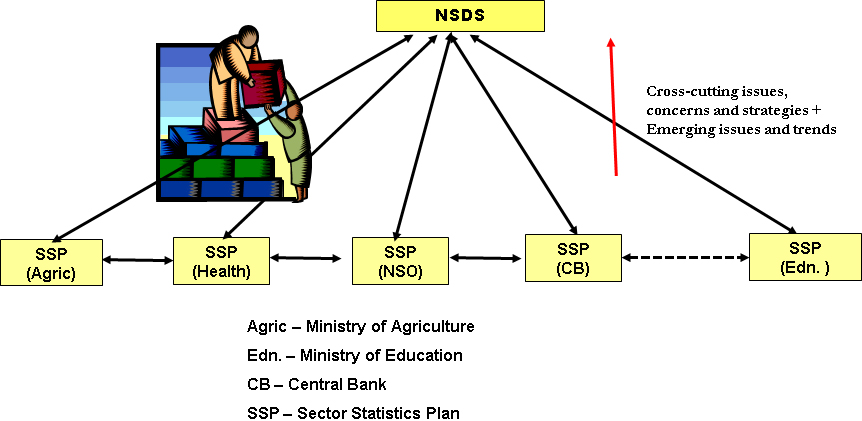

Figure 1.

Sectoral approach to design of NSDS.

2.2.2Mainstreaming sectors into the NSDS

It is well recognized that administrative data which are compiled by MDAs play a crucial role in monitoring and reporting on development progress at all levels. It has been estimated in some African countries that administrative data constitute upwards of 70% of the total amount of data required to monitor national development. Administrative data are compiled primarily for use for planning and decision-making in institutions that compile them. Administrative data are generally cheaper and easier to compile vis-a’-vis census and survey data. That notwithstanding, administrative data across African countries have tended to be incomplete, inconsistent, out-of-date, and insufficiently reliable to be used with confidence. The NSDS holds the prospect of providing an antidote for inadequate administrative data especially when the sectoral or bottom-up approach is used to design the NSDS. Using this approach, a manageable number of sectors – ‘sector’ are government entities (Ministries, Departments, and Agencies – MDAs) – are integrated into the NSDS process. Five to ten sectors are recommended for a country designing the NSDS for the first time. This number includes the NSO as a special sector. The process is scalable and more sectors are added in a phased manner experience with the process builds up and more resources become available. For instance, the first NSDSs included 7 sectors in Botswana, 7 in Malawi, 13 in Namibia, 10 in Sudan, 9 in Uganda, 9 in Ghana, 11 in Zambia, 10 in Zimbabwe, etc.

Three things are done in each selected sector:

1. Statistical advocacy is undertaken at the highest level to secure buy-in and political support for the NSDS and statistics in general from the leadership in the secto;

2. Assessment of the state of the sector statistical system. This is a self-assessment undertaken by the sectors themselves to ensure ownership of both the process and the product;

3. Based on the assessment in 2) above, a Sector-specific Statistical Plan (SSP) is designed that speaks to identified issues and challenges in 2) above.

The SSPs are then used as building blocks for the sector-inclusive NSDS, which takes onboard cross-cutting issues, concerns, and strategies from sectors. The NSDS also takes on board emerging issues and trends in statistical organization and management. In particular, the NSDS provides a framework and pathways towards transforming and modernizing NSSs so that they can produce better statistics to support development processes [1, 9]. The above figure depicts the above approach [6].

2.2.3Support to the NSDS process

Role of NSO

The NSO is the prime mover of the NSDS process right from the design, to implementation, and monitoring and evaluation stage. It prepares the process roadmap, establishes structures, mobilizes stakeholders, empowers the sectors through training, and provides them with requisite assessment formats for undertaking the assessment and designing the SSPs. As noted earlier, international NSDS design guidelines are available to guide the process. Besides, most African countries have sought technical assistance and funding to support for their NSDS processes [1, 9].

Technical assistance for the NSDS

The role of technical assistance should be very clear, namely that consultants are used to train and support national staff to design the NSDS – consultants themselves should not design the NSDS for the country. In addition, consultants should play the role of critiquing the status quo, maintaining a climate of openness and participation, keeping the process-oriented and discussions focused, and bringing new insights, perspectives, and best practices into the process. It helps a lot if the process is supported by two consultants – a national consultant and an international consultant. Use of a national consultant has the advantage of proximity and continuity as usually, the international consultant undertakes periodic missions to the country to initiate activities, review work done to ensure completeness, and ensure quality against agreed methodologies and frameworks.

2.2.4Stages in the NSDS lifecycle

PARIS21 has identified 8 steps in the NSDS lifecycle which countries should systematically follow in designing and implementing their NSDSs. These steps fall into three stages as can be seen below [9].

Stage 1: Preliminary

1. Stakeholder engagement: advocate for NSDS and produce policy documents for the NSDS process.

2. Preparation: design a roadmap for the NSDS process, establish NSDS design structures, designate NSDS coordinator, officially launch the NSDS process, and undertake training on NSDS.

3. Assessing the NSS: design assessment tools, train sector focal persons on the use of the tools, prepare assessment reports for sectors, consolidate the sector assessment reports, and validate the reports.

Stage 2: Design

1. Strategic framework: formulate strategic foundations (vision, mission, and core values), chart the strategic direction (goals, strategic objectives, initiatives) that speak to the data challenges identified through the aforementioned assessment, and validate the strategic framework. This should be done for each sector and the overall NSDS.

2. Action Plans: prepare action plans, cost the plans, identify risks, and mitigation measures. This should be done for each sector and the overall NSDS.

3. Putting it together: assemble SSPs and the NSDS, conduct stakeholder validation of the SSPs within the respective sectors and the NSDS at the national level and undertake a high profile official launch of the NSDS.

Stage 3: Implementation, and monitoring and evaluation

1. Implementation and monitoring: create stakeholder awareness about the SSPs and the NSDS within sectors to enhance institutional and organizational aspects of the NSS; mobilize drivers of strategic success, viz., people, processes and technology improvement; mobilize resources for the implementation of SSPs and the NSDS; implement action plan; monitor and report progress; and make adjustments as necessary.

2. Evaluation: conduct independent mid-term and final evaluation, have evaluation reports approved, and disseminate the finalized evaluation report.

The design of a sector-inclusive NSDS requires reasonable time to accomplish. PARIS21 estimates that the process should take up to 18 months for countries designing their NSDS for the first time. The time can be substantially less for countries designing a second or third NSDS. According to PARIS21 [9], all African countries except Somalia have designed their NSDS. This is both misleading and inaccurate. Most countries have designed first generation statistical plans focusing on the NSO and uptake on NSDS as defined above has been very low indeed because of the challenges presented below. For instance, the Workshop on NSDS for SADC countries which was organized by the African Development Bank in November 2015 showed that of the 15 SADC Member States attending the workshop, only four (4) have designed and are implementing sector-inclusive NSDS (African Development Bank, unpublished report). Countries that have designed and implemented sector-inclusive NSDSs in Africa are few and far in between and these include, among others, Botswana, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Ghana, Gambia and Senegal. Other countries where this approach is being used to design the NSDS include Egypt, Namibia, Zambia, Mauritius, Zanzibar, etc. Some countries are taking short cuts to this process by skipping the design of SSPs to deal with sector-specific data challenges and proceeding to design NSDSs that are not sector-inclusive. Unfortunately this will not contribute to the improvement of sectoral statistical systems and administrative data in the sectors.

2.2.5Role of leadership

Leadership is a great resource that has been identified as one of the success factors for the NSDS process. The process requires effective and strategic leadership at three levels: high political/policy level, organizational level, and operational level working in sync.

2.2.5.1. High political/policy level

This level of leadership includes officials who make policies and those who dispense resources for statistics at the national and sector level. They should endorse the NSDS process; provide strategic leadership and high-level stewardship of the NSDS process; and put in place appropriate policies and/or approve arrangements for the process. It is, therefore, important that leaders at this level are identified and strong political will to support statistics is cultivated among them.

2.2.5.2. Organisation level

At this level, the Head of NSO is expected to play a key role in the NSDS process including advocating for political commitment at the policy level and keeping leadership at this level informed; keeping the Statistics Board/Council briefed about the NSDS processes in case of semi-autonomous NSOs; seeking technical assistance for the NSDS process from development partners; constituting NSDS structures, including an Inter-agency Statistics Committee which he/she chairs and an NSDS design team headed by an NSDS coordinator; and causing Heads of sectors to constitute Sector Statistics Committees to take the NSDS process forward in the sectors; and generally driving the NSDS process at a high level.

2.2.5.3. Operational level

At operational level, leadership of the process is provided by NSDS design team and Sector Statistics Committees.

NSDS design team

At this level, an NSDS design team spearheads the design of the NSDS following international standards and guidelines as well as best practice; mobilizes and sensitizes sectors to participate in the NSDS processes; organizes and supports meetings of the Inter-agency Statistics Committe; organizes training for sectors on NSDS processe; organizes periodic meetings for sectors to share experiences and lessons from the process; supports sectors in undertaking statistical advocacy especially at a high level and in undertaking assessment of the state of statistics in sectors; supports sectors to design SSPs; works with the consultant(s) to design the NSDS using SSPs as building blocks, and organizes stakeholder meetings to validate the NSDS.

Sector statistics committees

These committees are expected to advocate for statistics in the sector including at high level; identify major data needs related to the sector; identifying and profiling key stakeholders that use sector statistics; identifying major offices in the sector currently collecting or compiling statistic; preparing a formal inventory of the different data and infrastructure for data collection, management, and dissemination in the sector; identifying data collected, methodologies and procedures used, coverage, availability, levels of aggregation, quality, frequency of updating and utility; identifying data gaps and priorities for addressing them in line with the sectoral policies, national and international development goals; designing Sector Statistics Plans and having them validated and endorsed.

2.2.6Extending the NSDS concept

As more and more countries design and implement the NSDS, there is now increasing demand for extending the NSDS concept to sub-national jurisdictions and regional economic communities. PARIS21 has guided the said extensions [13].

2.2.6.1. NSDS extension to sub-national jurisdictions

In several African countries, governments are implementing a decentralization policy whereby administration and planning functions have been devolved from the centre to sub-national jurisdictions (lower administrative levels) to improve governance and service delivery. The sub-national jurisdictions include States in Nigeria and Sudan, counties in Kenya and districts in Malawi, Rwanda, and Uganda, etc. These units are playing a critical role in interventions for poverty reduction, the achievement of SDGs, national development generally, monitoring and evaluation especially of service delivery. Unfortunately apart from population and housing censuses, current statistical systems generally do not provide highly disaggregated data needed for planning and decision-making at the sub-national level.

To meet the increasing demand for highly disaggregated data, the NSDS concept has been extended to sub-national jurisdictions – the design of sub-NSDS. In a few countries, this has been done. The design of sub-NSDS is quite advanced in Uganda. For instance, the NSDS I (2005/6–2011/12) in Uganda covered 13 MDAs, 1 Civil Society Organization and 12 districts while NSDS II (2013/14–2017/18) covered 27 MDAs, 1 Civil Society Organization and 152 districts and municipalities (although not all sub-NSDSs were implemented). The general NSDS design guidelines were used for this purpose. It is interesting to note that some of the districts in Uganda have been able to earmark funding for sub-NSDSs in their overall district budgets. Countries should consider including sub-national jurisdictions in their NSDS design processes and PARIS21 has produced guidelines for doing this.

2.2.6.2. Regional statistical development strategies

There are eight regional economic communities (RECs) that are recognized by the African Union which constitute building blocks for African integration. These RECs are economic blocks that aim to achieve regional integration and development. They have established regional statistical systems with the remit to produce quality and comparable statistics based on methodologies harmonized among member states of each REC. The concept of the NSDS has been extended to the production of the Regional Strategy for the Development of Statistics (RSDS) as a framework for strengthening regional statistical systems.

The RSDS for any REC aims to:

• build a strong and stakeholder-driven regional statistical system.

• mainstream statistics into the regional integration agenda (treaties, protocols and development strategies),

• raise the profile and strengthen the statistical function at the headquarters of the REC,

• build statistical capacity for production of harmonized and comparable regional statistics,

• make RSDS and NSDS complementary processes, and

• rationalize monitoring, reporting, and evaluation of statistical development in the RECs.

The process of designing the RSDS should also be participatory with key stakeholders in each partner state consulted. The RSDS should be anchored into the regional integration agenda and processes, and should, as much as possible, build on the NSDSs of partner states. Such RSDSs have been successfully designed and implemented in some RECs including the East African Community, Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, the Southern African Development Community, etc.

2.3NSDS challenges and some lessons learned

The following are some of the challenges countries have faced in designing and implementing the NSDS and some lessons learned.

2.3.1NSDS challenges

The main challenges to NSDS processes which have led to stumbling in many African countries leading to failure to make the NSDS a game-changer include the following, among others:

1. Understanding the importance of the NSDS: In some African countries, the NSDS has not been appreciated as a game-changer. It has been looked at as yet another statistical activity. This is reflected in laxity in the design of the NSDS – appointment of middle-level staff of NSO to coordinate the NSDS process, under-resourcing the NSDS process, lack of periodic briefs for political/policy leadership, failure for NSDS design structures to discharge their responsibilities e.g. hold meetings periodically, over-run of timelines in the NSDS roadmap, etc.

2. Leadership: There are countries where leadership has not been mobilized at all relevant levels and the NSDS process has been put in the hands of middle-level officials at the NSOs. As a result, the NSDS in these countries has not been prioritized, NSDS processes have been inadequately resourced, there have been serious time overruns in the roadmap, stakeholders have been inadequately engaged, and as a result, the NSDS has not been as effective as expected.

3. Preliminary activities: Preliminary activities are important as all follow-up activities depend on them. Unfortunately, a lot of the time not enough effort is dedicated to preliminary activities. This has led to an inadequate understanding of the NSDS and its processes among the NSO leadership and staff as well as other key stakeholders such as policy makers and even among some consultants hired to provide technical assistance to the process. This creates problems for the NSDS process including producing unrealistic roadmaps and budgets for the process as well as failing to turn the NSDS into an effective framework for turning around the NSS.

4. Misalignment to development processes: Some countries have designed their NSDS in isolation from the nation’s overall development processes and priorities. Such NSDSs were not mainstreamed into NDPs and budgets for necessary funding. In some cases, NSDSs were prepared by NSOs without widespread consultations. This made it difficult to secure political support, commitment to, and needed funding for the implementation of the NSDS.

5. NSDS process: As mentioned earlier, the NSDS process is as important as the NSDS itself. The process works well when key stakeholders are not just consulted but engaged and own both the NSDS process and product, and are committed to its implementation. Unfortunately, the process is often not well understood and executed. There is a tendency to try and design the NSDS in the shortest time possible (a couple of months or so) which is not consistent with the requirement to engage as many stakeholders as possible. Also, the NSDS activities in sectors tend to take a lot more time than usually planned for. This is because the NSDS design team has limited control over the staff in sectors that also do not prioritize the NSDS activities.

6. Statistical advocacy: Experience has shown that statistical advocacy is rarely well done at a high level in sectors. This is usually due to entrenched bureaucracy in government and lack of voice and status by statistical personnel in the sectors. Thus, the NSO leadership is urged to assist sectors with advocating for statistics through one-on-one discussions with the sector leadership or presentations to the top management of the sector. In one country, the NSO leadership used sector top management meetings meant for validating the SSP to advocate for the NSDS and statistics generally.

7. Capacity building: Capacity building is an implicit objective of the NSDS process. During the process, statistical personnel are introduced to statistical planning modalities, new knowledge, concepts, frameworks, experiences, and trends in statistical organization and management. This is formally done in workshops on NSDS and its processes. It is also done in one-on-one discussions and mentoring of national staff by consultants.

8. Peer learning and benchmarking: Countries in Africa are at different stages of institutionalizing the NSDS into the national statistical mainstream. There are front runners and also laggers. Countries are, therefore, urged to share experiences and learn from each other (peer learning and benchmarking) especially from front runners in the same region where conditions are similar. This has helped countries especially those designing the NSDS for the first time to learn from their peers about what has worked for them, what did not work well, and why so that they can avoid making the same mistakes.

9. Keeping stakeholders informed and interested: It is critical that stakeholders remain informed and interested in the NSDS process. NSDS guidelines recommend that as part of the NSDS process, an NSDS bulletin be produced and circulated widely among stakeholders including development partners. Unfortunately in many countries, the bulletin has not been produced at all or it has been produced less regularly during the NSDS process.

10. Extension of the NSDS: The NSDS has been extended to some RECs. The process of designing and implementing the RSDS has involved wide stakeholder consultations. However, very few countries have extended the NSDS to sub-national jurisdictions where development interventions take place and where service delivery should be monitored.

11. NSDS implementation: The weakest aspect of the NSDS framework in Africa has been resourcing its implementation. Many NSDSs have been inadequately implemented due to limited resources. In a majority of cases, this arose because of failure to engage and keep key stakeholders interested in the NSDS design processes especially policy and decision-makers who dispense resources and development partners. For instance, in some countries the Minister for Finance and/or Planning learned about the NSDS when he/she was invited to officially launch the NSDS document. In the same vein, some development partners got to know about the NSDS when the NSO was looking for resources for its implementation.

2.3.2Lessons learned

Through proof-of-concept and experience accumulated in designing and implementing the NSDS in African countries, the following lessons have been learned, among others:

1. A critical mass of understanding of the NSDS concept and process should be created among stakeholders to secure buy-in and political support to the NSDS process.

2. National leadership at various levels (from political/policy to technical/operational) plays an important role in directing the NSDS process and galvanizing support for the process. In particular, better results have been achieved where the Head of the NSO has internalized the NSDS and driven its processes at a high level.

3. It is important to synchronize the NSDS with the NDP; where possible the NSDS should be mainstreamed into the NDP and funded accordingly.

4. Keeping key stakeholders informed and interested in the NSDS process is essential. This requires that an NSDS bulletin is produced and shared widely with key stakeholders.

5. NSDS preliminary activities should be taken very seriously as all subsequent activities depend on them.

6. The process of designing the NSDS is as important as the NSDS itself. It is, therefore, important that the process is internalized first by the NSO leadership and staff and then by other stakeholders for it to be effectively executed.

7. Where sector statistics teams are constrained to advocate for statistics at the highest level in the sector, the NSO leadership should come in to provide needed support.

8. While technical assistance is important to the process, countries should be judicious in selecting consultants, using those with prior knowledge about the country in addition to having extensive and relevant experience in the design of sector-inclusive NSDS, especially in the region.

9. The consultants should come on board as early in the process as possible. When consultants have joined the process mid-stream, the process has been slowed down to allow them to catch up.

10. Training of staff involved in the NSDS should be a continuous process for some aspects of the process to be appreciated. So one or two or three workshops will not do.

11. Countries embarking on the NSDS process for the first time can benefit a lot if, in addition to following international guidelines, benchmark and learn from their peers especially the NSDS front runners in the same region.

12. Countries should have the NSDS document launched at a high profile event with a high government official e.g. President, Prime Minister, or Minister launching the document. The use of such a newsmaker automatically makes the event newsworthy thereby publicizing in the media the NSDS and statistics generally.

3.Concluding remarks

The signing up to the results agenda by African countries led to unprecedented demand for statistics and this created challenges for National Statistical Systems that were, by and large, already weak, under-resourced, and under-performing. Thankfully, it also created unprecedented opportunities for statistical development. One such opportunity is designing and implementing a second-generation national statistical plan, the National Strategy for the Development of Statistics (NSDS). Unlike previous statistical plans which focused on the NSO, the NSDS aims to cover the entire NSS. A defining characteristic of the NSDS is the attention paid to the process which includes a bottom-up approach whereby sectors are selected, assessed, and Sector-specific Statistics Plans designed. These plans are used as building blocks for country-specific, country-owned, stakeholder-driven, and sector-inclusive NSDS.

The NSDS process takes time to execute. It is best planned for in advance in terms of a process roadmap and structures, partnerships, and resources. Most of the NSDS design time is spent on undertaking statistical advocacy, empowering staff, assessing the state of statistics in sectors, and putting it all together to produce the NSDS. Proof-of-concept and experience in Africa show that while challenges to the NSDS processes remain, some progress is being made.

Increasingly institutional, organizational, and technical issues are being resolved and better infrastructure and statistical capacity are being built. As a result, the NSS has become a collective force behind the official statistics that oil public policy, planning, decision-making, and reporting on development progress. The NSDS is proving a good framework for modernizing and transforming national statistical systems consistent with the data revolution for sustainable development. In addition to strengthening traditional data sources, new data sources are being explored; new technologies are being harnessed; structures and capacity for improving administrative data are being built in sector; etc. However, the said progress has been uneven across countries and more needs to be done in all African countries to put statistics on a sustainable trajectory.

There are guidelines for extending the NSDS to sub-national jurisdictions and regional economic communities (RECs). However, while the NSDS has been successfully extended to RECs in Africa, the extension to sub-national jurisdictions has not gained traction yet. More work needs to be done in this area across Africa.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge with thanks Dr. Norah Madaya, former Director for Statistical Coordination Services at the Uganda Bureau of Statistics for initial comments on the paper.

References

[1] | African Development Bank, PARIS21 and Intersect, Mainstreaming sectoral statistical system: a guide to planning a coordinated national statistical system, Tunis, Tunisia and Paris, France, (2007) . |

[2] | African Development Bank, AUC and the UN Economic Commission for Africa, The African Data Consensus, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (2015) . |

[3] | African Union Commission, Decision on Post-2015 Development Agenda, Doc. EX.CL/836 (XXV), African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, June (2014) . |

[4] | African Union Commission, African Development Bank and UN Economic Commission for Africa, Strategy for the Harmonization of Statistics in Africa, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (2010) . |

[5] | Kenya, Republic of, Second Medium Term Plan (2003–2017), Ministry of Development Planning, Nairobi, Kenya, (2003) . |

[6] | KiregyeraBen., Emerging Data Revolution in Africa: Strengthening Statistics, Policy and Decision-making Chain, Sun Press, South Africa, 2015. |

[7] | Namibia, Republic of, Namibia’s Fifth National Development Plan: Working Together Towards Prosperity (2017/18 –2021/22), National Planning Commission, Windhoek, Namibia, (2017) . |

[8] | National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Third National Strategy for the Development of Statistics (2019/20–2023/24), Kigali, Rwanda, September (2019) . |

[9] | PARIS21, NSDS Guidelines 2.3, PARIS21, Paris, France, (2018) . |

[10] | PARIS21, 2019 NSDS Progress Report, PARIS21, Paris, France, May (2019) . |

[11] | Statistics South Africa, Strategic Plan (2015/2016–2019/2020), Pretoria, South Africa, (2015) . |

[12] | Uganda Bureau of Statistics, Second Plan for National Statistical Development (2013/14–2017/18), Kampala, Uganda, (2013) . |

[13] | Uganda, Republic Of, Third National Development Plan (2020/21–2024/25), National Planning Authority, Kampala, Uganda, July (2020) . |

[14] | United Nations A World that Counts: Mobilizing the Data Revolution for Sustainable Development, A Report to the UN Secretary General by The Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development, (2014) . |

[15] | United Nations, The Cape Town Global Action Plan for Sustainable Development Data, Resolution on the work of the Statistical Commission adopted by the UN General Assembly in July (2017) (RES/71/313). |

[16] | Zambia, Republic of, Seventh National Development Plan (2017–2021), Ministry of National Development Planning, Lusaka, Lusaka, (2017) . |